Abstract

Purpose

To assess the benefits and tolerability of a dietary supplement based on omega-3 fatty acids to relieve dry eye symptoms.

Methods

A total of 1,419 patients (74.3% women, mean age 58.9 years) with dry eye syndrome using artificial tears participated in a 12-week prospective study. Patients were instructed to take 3 capsules/day of the nutraceutical formulation (Brudysec® 1.5 g). Study variables were dry eye symptoms (scratchy and stinging sensation, eye redness, grittiness, painful and tired eyes, grating sensation, and blurry vision), conjunctival hyperemia, tear breakup time (TBUT), Schrimer I test, and Oxford grading scheme.

Results

At 12 weeks, each dry eye symptom improved significantly (P<0.001), and the use of artificial tears decreased significantly from 3.77 (standard deviation [SD] =2.08) at baseline to 3.45 (SD =1.72) (P<0.01). In addition, the Schirmer test scores and the TBUT increased significantly, and there was an increase in patients grading 0–I in the Oxford scale and a decrease of those grading IV–V. Significant differences in improvements of dry eye symptoms were also found in compliant versus noncompliant patients as well as in those with moderate/severe versus none/mild conjunctival hyperemia.

Conclusion

Oral ω-3 fatty acids supplementation was an effective treatment for dry eye symptoms.

Keywords: dry eye symptoms, artificial tears, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, nutraceutical supplement, ocular inflammation, eye discomfort

Introduction

Dry eye disease is a common condition, particularly affecting women and the elderly.1 A wide variation in the prevalence of dry eye disease, ranging from <0.1% to as high as 33%, has been reported.2 This wide variation is related to differences in definitions, diagnostic criteria, and study populations (eg, population surveys or physician assessments). It has been estimated that only 20% subjects with mild symptoms seek medical care as compared to 50% of those with moderate disease and virtually all patients with severe disease.3 In addition, the burden of dry eye disease to the patient is considerable in relation to impact on visual function, daily activities, social and physical functioning, workplace productivity, and health-related quality of life.4,5

Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the tears and the ocular surface in which dysfunction of the lacrimal functional unit with increased osmolarity of the tear film and inflammation of the ocular surface play a prominent role.6 Studies in tissue culture, animal models, and humans strongly support the role of inflammation as part of the core pathogenesis of dry eye disease.7 The chronicity of the disease suggests that dysregulation of immune mechanisms leads to a cycle of continuous inflammation. Accordingly, because of better understanding of the inflammatory-mediated pathogenesis of dry eye disease, anti-inflammatory therapy is considered a causative therapeutic approach, since its objective is to interrupt the inflammatory cascade, rather than other treatment modalities aimed at providing symptomatic relief.8

Essential polyunsaturated fatty acids omega-3 (ω-3) and omega-6 (ω-6) are the precursors of eicosanoids, which are locally acting hormones that mediate the inflammatory processes.9 In a literature review of the treatment of dry eye syndrome with ω-3 and ω-6 essential fatty acids, ω-3 supplementation demonstrated an anti-inflammatory effect, inhibiting creation of ω-6 prostaglandin precursors, preventing apoptosis of the secretory epithelial cells in the lacrimal gland, and clearing meibomitis allowing a thinner, more elastic lipid layer to protect the tear film and cornea.10 In addition, other studies have provided evidence of the beneficial effect of supplementation with ω-3 essential fatty acids in the treatment of dry eye disease.11–16 Two recent meta-analyses of randomized controlled studies support the use of ω-3 fatty acid supplementation as effective therapy for dry eye syndrome.17,18 However, further real-world studies are needed to substantiate existing evidence for the use of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)-based supplements in the improvement of dry eye disease.

Therefore, a prospective, open-label intervention study was conducted to assess the effect of an oral nutraceutical formulation based on ω-3 PUFAs on relieving dry eye symptoms in a large series of patients attending in the routine ophthalmological practice.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This was an open-label, prospective, noncomparative, intervention, and multicenter study carried out in ophthalmological clinics throughout Spain under conditions of daily practice. Patients were recruited by the participating ophthalmologists during a routine ophthalmological appointment. The primary objective of the study was to assess the effectiveness of an oral nutraceutical formulation based on ω-3 PUFAs, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants in the relief of dry eye-related symptoms. Secondary objectives included whether this oral formulation could improve conjunctival hyperemia, tear film stability, ocular surface damage, and tear production, and reduce the use of artificial tears. The tolerability of the product was also evaluated.

Patients of both sexes, aged 16 years or older, contact lens users and nonusers on current treatment with artificial tears due to dry eye disease, who were not completely satisfied with ocular topical treatments, were eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients with fish allergy, history of bariatric surgery for morbid obesity, ocular disorders requiring the use of eye drops other than artificial tears, pregnant and breast-feeding women, and those deemed unable to participate according to the ophthalmologist’s criteria were excluded. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for the protection of human subjects, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study procedures

Ophthalmologists all over the country were invited by the sales division of the pharmaceutical company which manufactures the supplement (Brudysec® 1.5 g, Brudy Laboratories, Barcelona, Spain) to participate voluntarily in the study. Between February 1, 2014 and May 1, 2014, patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and signed the informed consent were recruited, with a total of 20 patients per ophthalmologist.

Patients were visited at baseline and at the end of the study (12 weeks). At the baseline visit (visit 0), the patient’s eligibility was assessed, the informed consent form was signed, baseline parameters were assessed, and the nutraceutical formulation was prescribed. The following data were recorded: demographics (age, sex), mean daily eye drops of artificial tears, use of contact lenses (categorized as yes/no) and mean daily wear (hours), dry eye symptoms (categorized as 0, none; 1, mild; 2, moderate; and 3, severe) including scratchy and stinging sensation in the eyes, eye redness, grittiness, painful eyes, tired eyes (eye fatigue), grating sensation, and blurry vision. Conjunctival hyperemia was rated as none, mild, moderate, and severe. Tear breakup time (TBUT) was measured by instillation of one drop of 2% fluorescein. The time until disappearance of the dye was recorded, and the average of three trials was calculated. Tear instability was defined as TBUT <10 seconds. Tear quantification was assessed with the Schirmer I test, which was applied during a 5 minutes interval, without anesthesia. The Oxford grading scheme19 was used to estimate surface damage according to the intensity of fluorescein staining, ranging from I to V for each panel (0–I, normal; II–III, mild to moderate; and IV–V, severe.

At the baseline visit, patients were given the nutraceutical formulation (Brudysec® 1.5 g) and were instructed to take three capsules once daily with a main meal (excluding breakfast). The composition of the supplement formulation is detailed in Table 1.20 This is a concentrated DHA triglyceride having a high antioxidant activity, patented to prevent cellular oxidative damage.21,22 Ophthalmologists paid special care to insist on the importance of compliance with the dietary supplement and the benefit that the patient may receive from the supplement.

Table 1.

Composition of Brudysec® 1.5 g

| Composition | Per capsule | % reference intake | Per three capsules | % reference intake |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrated oil in ω-3 fatty acids | 500 mg | 1,500 mg | ||

| TG-DHA 70% | 350 mg | – | 1,050 mg | – |

| EPA 8.5% | 42.5 mg | – | 127.5 mg | – |

| DPA 6% | 30 mg | – | 90 mg | – |

| Vitamins | ||||

| Vitamin A (retinol) | 133.3 µg RE | 16.66 | 400 µg RE | 50 |

| Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) | 26.7 mg | 33 | 80 mg | 100 |

| Vitamin E (D-α-tocopherol) | 4 mg α-TE | 33 | 12 mg α-TE | 100 |

| Essential trace elements | ||||

| Zinc | 1.6 mg | 16.6 | 5 mg | 50 |

| Copper | 0.16 mg | 16.6 | 0.5 mg | 50 |

| Magnesium | 0.33 mg | 16.6 | 1 mg | 50 |

| Selenium | 9.17 µg | 16.6 | 27.5 µg | 50 |

| Other components | ||||

| Tyrosine | 10.8 mg | – | 32.5 mg | – |

| Cysteine | 5.83 mg | – | 17.5 mg | – |

| Glutathione | 2 mg | – | 6 mg | – |

Notes: The recommended daily intake is 250 mg of DHA.20

Abbreviations: TG-DHA, triglyceride-bound docosahexaenoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DPA, docosapentaenoic acid; RE, retinol equivalents; TE, tocopherol equivalents; –, not established.

At the final visit (week 12), data recorded included compliance with treatment with the questions “Did you take the three capsules every day?” (categorized as always, some forgetfulness, much forgetfulness); “Have you noticed any change in symptoms?” (categorized as yes or no); assessment of dry eye symptoms and conjunctival hyperemia as at baseline visit; mean daily eye drops of artificial tears; results of TBUT test, Schirmer test, and Oxford grading test; if contact lens wearer, mean daily wear (hours); better tolerance to contact lenses (categorized as yes or no); mean daily eye drops of artificial tears; tolerability to nutraceutical formulation (categorized as fish-tasting regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or none of the above); level of the patient’s satisfaction (categorized as not at all satisfied, satisfied, or very satisfied); and clinical assessment of the ophthalmologist (categorized as no improvement, mild improvement, or large improvement). Patients could withdraw from the study of their own free will or according to the ophthalmologist’s criteria due to adverse events, concomitant diseases, or any other medical reasons.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (±SD) or as median and interquartile range (25th–75th percentile), while categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Differences of continuous variables between the visit 0 (baseline) and the visit at the end of treatment (week 12) were analyzed with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples. Changes in each individual dry eye symptom between the groups of none/mild versus moderate/severe conjunctival hyperemia, and between compliant (those who always took the three capsules a day) and noncompliant patients (those who reported some or much forgetfulness) were compared with the Mann–Whitney U-test. The degree of satisfaction with treatment for patients and clinicians between visits 0 and at 12 weeks were compared with the chi-square (χ2) test. Statistical analyses were performed with the R Project for Statistical computing (R 3.0) program (http://www.r-project.org). Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

A total of 1,509 patients with dry eye disease were recruited for the study. However, data from 90 patients (6%) were not included in the analysis due to missing data in one and/or two study visits regarding dry eye symptoms (primary variable of the study) or compliance with the nutraceutical supplement. Therefore, the study population included 1,419 patients. Seventy-four percent were women, with a mean (SD) age of 58.9 (15.0) years (range: 16–100 years). All patients used artificial tears to relieve dry eye symptoms, with a daily mean (SD) of 3.8 (1.6) instillations of eye drops. Contact lens users accounted for 15.9% of the study population (n=205). As listed in Table 2, the mean intensity of dry eye symptoms varied from 1.74 (0.88) for painful eyes to 0.98 (0.92) for blurry vision, with a mean value of 9.67 (6.38) for all symptoms together. Conjunctival hyperemia was mild in 49.9% of patients and moderate in 31.5%. Results of the Oxford grading scale, TBUT, and Schirmer test are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of variables at baseline (visit 0) and at 12 weeks in 1,419 patients with dry eye disease

| Variables | Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Men, % | 25.7 | ||

| Women, % | 74.3 | ||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 58.9 (15.0) | ||

| Daily eye drops of artificial tears, mean (SD) [range] | 3.77 (2.08) [1–25] | ||

|

| |||

| Variables | Baseline (visit 0) | Visit at 12 weeks | P-value |

|

| |||

| Dry eye symptoms, mean (SD) | |||

| Scratchy | 1.31 (0.94) | 0.62 (0.69) | <0.001 |

| Stinging sensation | 1.56 (0.90) | 0.72 (0.70) | <0.001 |

| Eye redness | 1.42 (0.84) | 0.70 (0.72) | <0.001 |

| Grittiness | 1.43 (0.86) | 0.68 (0.71) | <0.001 |

| Painful eyes | 1.74 (0.88) | 0.79 (0.71) | <0.001 |

| Tired eyes | 1.20 (0.99) | 0.50 (0.66) | <0.001 |

| Grating sensation | 1.45 (0.92) | 0.58 (0.66) | <0.001 |

| Blurry vision | 0.98 (0.92) | 0.33 (0.58) | <0.001 |

| Conjunctival hyperemia, n (%) | |||

| None | 125 (11.9) | 398 (40.2) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 523 (49.9) | 521 (52.7) | |

| Moderate | 330 (31.5) | 68 (6.9) | |

| Severe | 71 (6.8) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Oxford grade, n (%) | |||

| Right eye | |||

| 0 | 180 (13.0) | 581 (43.2) | <0.001 |

| I | 460 (33.4) | 537 (39.6) | |

| II | 437 (31.6) | 173 (12.7) | |

| III | 233 (16.9) | 53 (3.9) | |

| IV | 55 (4.0) | 8 (0.6) | |

| V | 15 (1.1) | 0 | |

| Left eye | |||

| 0 | 169 (12.2) | 568 (42.0) | <0.001 |

| I | 471 (34.1) | 539 (39.8) | |

| II | 421 (30.4) | 182 (13.4) | |

| III | 243 (17.6) | 57 (4.2) | |

| IV | 66 (4.8) | 6 (0.5) | |

| V | 12 (0.9) | 1 (0.1) | |

| TBUT, seconds, median (IQR) | |||

| Right eye | 7 (5–10) | 10 (7–11) | <0.001 |

| Left eye | 7 (5–10) | 10 (7–11) | <0.001 |

| Schirmer test, mm, mean (SD) | |||

| Right eye | 9.06 (4.40) | 11.0 (4.43) | <0.001 |

| Left eye | 9.24 (4.62) | 11.2 (4.64) | <0.001 |

| Daily eye drops artificial tears, mean (SD) | 3.77 (2.08) | 3.40 (1.56) | <0.01 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; TBUT, tear breakup time; SD, standard deviation.

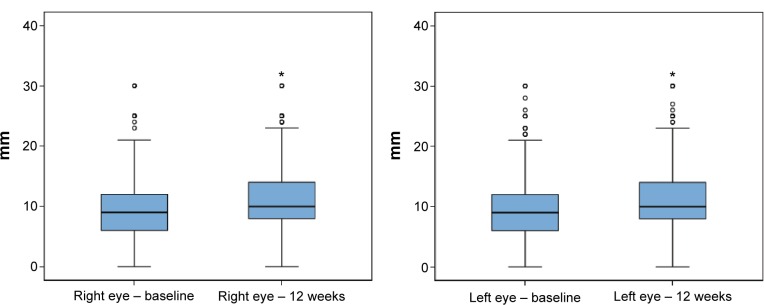

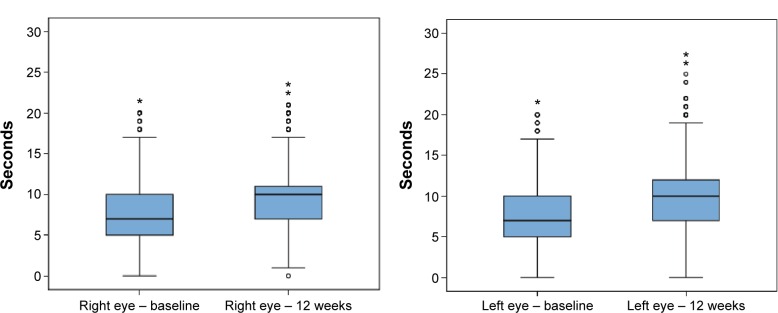

Data recorded at the final visit (week 12) showed statistically significant improvements in all study variables (P<0.001). The mean (SD) total symptom score decreased from 9.67 (6.38) to 4.22 (4.71; P<0.001). The mean number of daily instillation of artificial tears also decreased significantly from 3.77 (2.08) to 3.45 (1.72; P<0.01). As shown in Figures 1 and 2, the Schirmer test scores and the TBUT increased significantly, reflecting improvement in tear secretion and tear film stability, respectively. Moreover, there was an increase in the percentage of patients grading 0–I in the Oxford scale and a decrease of those grading IV–V (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Box plots for the comparison of Schirmer test scores (mm) before and after 12 weeks treatment with oral ω-3 fatty acids supplementation.

Notes: Data presented as median, IQR (25th–75th percentile), maximum, and minimum (○, above the value of 1.5 IQR; *, above the value of 3 IQR).

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Figure 2.

Box plots for the comparison of the TBUT scores (seconds) before and after 12 weeks treatment with oral ω-3 fatty acids supplementation.

Notes: Data presented as median, IQR (25th–75th percentile), maximum, and minimum (○, above the value of 1.5 IQR; *, above the value of 3 IQR).

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; TBUT, tear breakup time.

In relation to compliance with the nutraceutical supplement, 66% of patients (n=937) reported having always taken the three capsules daily and 34% reported some or much forgetfulness. Changes in dry eye symptoms according to compliance with ω-3 fatty acids supplementation is listed in Table 3. At the end of treatment (visit at 12 weeks), there were statistically significant mean differences as compared to baseline in all dry eye symptoms except for blurry vision. In addition, when the subgroup of compliant patients (n=937) was stratified according to the intensity of conjunctival hyperemia in the groups of moderate/severe versus none/mild, the degree of improvement in all dry eye symptoms was significantly higher (P<0.001) among those with moderate/severe conjunctival hyperemia than among those with none/mild conjunctival hyperemia (Table 4).

Table 3.

Improvement of dry eye symptoms according to compliance with treatment

| Dry eye symptoms | Baseline (visit 0)

|

Visit at 12 weeks

|

Difference 12 weeks versus baseline

|

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complianta | Noncompliantb | Compliant | Noncompliant | Compliant | Noncompliant | ||

| Scratchy | 1.31 (0.95) | 1.31 (0.93) | 0.56 (0.66) | 0.72 (0.72) | −0.74 (0.77) | −0.58 (0.66) | <0.001 |

| Stinging sensation | 1.58 (0.90) | 1.54 (0.88) | 0.67 (0.67) | 0.83 (0.74) | −0.91 (0.78) | −0.71 (0.70) | <0.001 |

| Eye redness | 1.45 (0.88) | 1.40 (0.81) | 0.64 (0.64) | 0.76 (0.81) | −0.80 (0.77) | −0.63 (0.82) | <0.001 |

| Grittiness | 1.77 (0.89) | 1.69 (0.84) | 0.75 (0.68) | 0.85 (0.75) | −1.0 (1.07) | −0.84 (0.76) | <0.001 |

| Painful eyes | 0.89 (0.96) | 0.84 (0.91) | 0.28 (0.57) | 0.34 (0.60) | −0.65 (1.30) | −0.48 (0.86) | 0.049 |

| Tired eyes | 1.21 (0.98) | 1.18 (0.91) | 0.47 (0.63) | 0.56 (0.70) | −0.74 (0.86) | −0.62 (0.74) | 0.029 |

| Grating sensation | 1.46 (0.95) | 1.42 (0.86) | 0.54 (0.64) | 0.66 (0.69) | −0.91 (0.85) | −0.76 (0.77) | 0.003 |

| Blurry vision | 0.92 (0.93) | 0.92 (0.90) | 0.33 (0.59) | 0.32 (0.56) | −0.70 (1.04) | −0.60 (0.74) | 0.116 |

Notes:

Compliant: always took the three capsules every day.

Noncompliant: some/much forgetfulness. Data presented as mean (standard deviation).

Table 4.

Improvement of dry eye symptoms according to the degree of conjunctival hyperemia in the subgroup of 937 compliant patientsa

| Dry eye symptoms | Baseline (visit 0)

|

Visit at 12 weeks

|

Difference 12 weeks versus baseline

|

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None/mild | Moderate/severe | None/mild | Moderate/severe | None/mild | Moderate/severe | ||

| Scratchy | 1.09 (0.90) | 1.69 (0.93) | 0.45 (0.63) | 0.877 (0.68) | −0.63 (0.73) | −0.93 (0.82) | <0.001 |

| Stinging sensation | 1.41 (0.88) | 1.92 (0.84) | 0.58 (0.65) | 0.89 (0.66) | −0.83 (0.77) | −1.04 (0.80) | <0.001 |

| Eye redness | 0.99 (0.70) | 2.07 (0.69) | 0.45 (0.57) | 0.92 (0.63) | −0.55 (0.67) | −1.15 (0.74) | <0.001 |

| Grittiness | 1.62 (0.87) | 2.08 (0.83) | 0.71 (0.69) | 0.88 (0.69) | −0.91 (0.83) | −1.15 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Painful eyes | 0.56 (0.78) | 1.35 (0.99) | 0.19 (0.46) | 0.36 (0.61) | −0.38 (0.63) | −1.11 (0.81) | <0.001 |

| Tired eyes | 0.99 (0.93) | 1.63 (0.98) | 0.40 (0.62) | 0.64 (0.67) | −0.59 (0.79) | −0.99 (2.04) | <0.001 |

| Grating sensation | 1.23 (0.87) | 1.85 (0.95) | 0.50 (0.64) | 0.69 (0.68) | −0.56 (0.68) | −1.02 (0.91) | <0.001 |

| Blurry vision | 0.77 (0.84) | 1.42 (0.96) | 0.23 (0.51) | 0.51 (0.69) | −0.74 (0.75) | −1.15 (0.89) | <0.001 |

Notes:

Compliant: always took the three capsules every day. Data presented as mean (standard deviation).

A total of 1,067 patients (79.2%) did not report any adverse event. In the remaining patients in whom adverse events occurred, the most frequent was fish-tasting regurgitation in 14.6%, followed by nausea in 4.6%, diarrhea in 2.7%, and vomiting in 0.4%. None of the patients were withdrawn from the study because of adverse events.

In relation to the level of patient satisfaction regarding clinical improvement of dry eye symptoms, 28.2% were very satisfied, 57.5% satisfied, and 14.3% not at all satisfied. In addition, 41.2% of ophthalmologists rated clinical improvement as large, 50.4% as mild, and 8.4% as no improvement.

Discussion

This prospective study carried out in a large clinical series of patients with dry eye symptoms and using artificial tears to relieve ocular surface dysfunction, attending routine daily practice, shows that dietary supplementation with ω-3 essential fatty acids, antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals was useful to improve dry eye symptoms. Other positive effects included a decrease in the use of artificial tears, reduced conjunctival hyperemia, and improvement in tear secretion and tear film stability. All individual dry eye symptoms (scratchy and stinging sensation in the eyes, eye redness, grittiness, painful eyes, tired eyes, grating sensation, and blurry vision) showed a marked improvement with statistically significant differences between end of treatment and baseline.

Omega-3 and ω-6 fatty acids are essential for ocular surface homeostasis, and they have to be absorbed from the food. It has been shown that ω-3 fatty acids exhibit anti-inflammatory activity by blocking proinflammatory eicosanoids and reducing cytokines.21 Antioxidant and ω-3 supplementation improve tear film parameters and decrease ocular surface inflammation.12,16,23 Dietary supplementation with PUFAs yields positive results in the improvement of dry eye signs and symptoms, and it seems that DHA and EPA may constitute the most effective treatment.23–25 In a study carried out using data of the Women’s Health Study, in which 4.7% of the sample of 32,470 women aged 45–84 years reported dry eye syndrome, a higher dietary intake of ω-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA, was associated with a lower prevalence of dry eye disease, including a 68% reduction in women who consumed ≥5–6 servings per week compared to ≤1 servings per week of tuna fish, which is one of the largest contributors of ω-3 fatty acids in the typical American diet.26 The use of ω-3 fatty acid supplementation as effective therapy for dry eye syndrome is also supported by data of two meta-analyses.17,18 In addition, a survey of Australian optometrists’ dry eye practices revealed that most practitioners recommend ω-3 fatty acid supplementation and increased dietary intake of ω-3 fatty acids for moderate and severe dry eye disease, respectively.27

In the recent clinical guidelines for the management of dry eye disease associated with Sjögren syndrome, dietary supplement with ω-3 fatty acids is recommended as anti-inflammatory therapy.28 Moreover, new research is under way using a large, double-masked, randomized, multicenter clinical trial (DREAM trial) to test the hypothesis that ω-3 supplementation is an effective treatment for dry eye disease.29 The primary outcome measure is the mean change from baseline in ocular surface disease index score at 6 and 12 months, and patients assigned to the experimental arm will receive 2,000 mg EPA and 1,000 mg DHA per day (taken in 5 gelcaps), which is a similar amount of DHA to that contained in our nutraceutical formulation.

The tolerability of the nutraceutical formulation was very good, and almost 80% of patients did not report any adverse event. None of the participants discontinued the nutraceutical supplement because of adverse events. Digestive discomfort, particularly fish-tasting regurgitation, was the most frequently side effect. On the other hand, in relation to the patient’s satisfaction with treatment, only 14.3% were not at all satisfied. Ophthalmologists only rated no improvement of dry eye symptoms in 8.4% of the cases.

Despite the limitation of the open-label design, the lack of a control group, and the treatment period limited to 12 weeks, the large number of participants and the fact that data were obtained in daily clinical practice add strength to the findings.

Conclusion

This study provides evidence of the role of oral supplementation with a nutraceutical formulation composed of ω-3 fatty acids, antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals to relieve dry eye symptoms. The study was conducted in daily ophthalmological practice, and the effects of ω-3 supplementation were assessed in a large sample of patients with dry eye disease using artificial tears. A decrease in the use of artificial tears, a reduction in conjunctival hyperemia, and an improvement in tear secretion and tear film stability were also observed. These results add evidence to the anti-inflammatory effects of ω-3 fatty acids and their clinically beneficial role in the therapeutic strategies of dry eye disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jaime Borras MD for coordinating and monitoring the trial, Sergi Mojal for statistical analysis, and Marta Pulido, MD, for editing the manuscript and editorial assistance. This study was supported by Brudylab, SL, Barcelona, Spain. List of members of the DECSG: Jordi Gatell Tortajada, Rafael Vila Silván, Guillermo Duarte Márquez, Francisco Pastor Pascual, Javier Benítez Herreros, Cármen del Pozo, Alberto Ollero Lorenzo, Pere Joaquim Motos Brossa, Anouska Rombouts Matamala, Natalia Spagnoli Santa Cruz, Patricia Ibáñez Ayuso, José Miguel Nieto Martín, Abdulrhaman Kabbani i Bota, Eloisa Mejias Gonzalez, Mariano Royo Sans, Ramón Domínguez Fernández, José María Cordero Vallverdú, Montserrat Gaya Catasús, Mª Dolores Tezanos Fernández, Silvia Gamboa Saavedra, José Luís Almeda Jurado, Francesca Mayoral Masana, Laura Martínez Pérez, Antonio Rojano Pastor, Fernando Urbano, Sara Ortíz Ortigosa, Eduardo Conesa, Yolanda Poza, Antonio Pérez Esteban, Cesar Hita Antón, Cristina Miguez García, Carlos Izquierdo Rodríguez, Alejandro Portero Benito, Luciano Doncis, Mahmoud Zabad Wehbi, Sara Núñez Márquez, Almudena Acero Peña, José Zamora Barrios, María Miranda Rollón, Mª Remedios Ortega García, Daniel Cornejo Martín, Rocío Sanjuán Ruíz, Francisco Ortíz Ramirez, Mª Dolores Romero Caballero, Mª Dolores López Bernal, Fernando Aguirre Balsalobre, Begoña Garrido Desdentado, Mónica Perez de Arcelus, M Soledad Leonato Dominguez, Javier Sornichero Martínez, Mª Paz Orts Vila, Concepción Molero Izquierdo, Gema Olea Zorita, Albino Rial Cortizo, Ramón Calvo Andrés, Emilia Tarragó Simó, María Francesca Perena, Manuel Timoteo Barranco, Ester López Navarrete, Eduardo Esteban González, Belén Fernández Pérez, Cristián Jesús Cortés Laborda, Dolores Sosa Domínguez, José Manuel Sandoval, Miguel Quevedo Rondón, Noemí Rosselló Silvestre, Abel Salas Carrascón, Jonatan Amián Cordero, Cinta Murcia Bello, Esther Escrivá Pastor, Salvador García Delpech, Francisco García-Franco Zuñiga, Mar Salvador Herrero, Pilar Dapena Urcola, Mª Victoria Montoya Alfaro, Santiago Montolio Doñate, Alba García López, Juan Sancristobal Epalza, Verónica Rodríguez Méndez, Josu Zarrabeitia Carrandi, David Pérez Silguero, José Ramón Pérez Fernández, Sixto Carrillo Pacheco, Antonio José Gómez Escobar, José Antonio Quevedo Alonso, José Francisco Moreno Galdo, and José Azogue Camacho.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This study was supported by Brudy Laboratories, Barcelona, Spain. Neither the author nor the participants cited in the Large Dry Eye Clinical Study Group (LDECSG) list have any conflict of interest to disclose. Brudy Laboratories was not involved in the analysis of data and interpretation of the result. The author reports no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Buring JE, Dana MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(2):318–326. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pflugfelder SC. Prevalence, burden, and pharmacoeconomics of dry eye disease. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(3 Suppl):S102–S106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yazdani C, McLaughlin T, Smeeding JE, Walt J. Prevalence of treated dry eye disease in a managed care population. Clin Ther. 2001;23(10):1672–1682. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(01)80136-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu J, Asche CV, Fairchild CJ. The economic burden of dry eye disease in the United States: a decision tree analysis. Cornea. 2011;30(4):379–387. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181f7f363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abetz L, Rajagopalan K, Mertzanis P, Begley C, Barnes R, Chalmers R, Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL) Study Group Development and validation of the impact of dry eye on everyday life (IDEEL) questionnaire, a patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure for the assessment of the burden of dry eye on patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:111. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaštelan S, Tomić M, Salopek-Rabatić J, Novak B. Diagnostic procedures and management of dry eye. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013:309723. doi: 10.1155/2013/309723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei Y, Asbell PA. The core mechanism of dry eye disease in inflammation. Eye Cont Lens. 2014;40(4):248–256. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahvsar AS, Bahvsar SG, Jain SM. A review on recent advances in dry eye: Pathogenesis and management. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2011;4(2):50–56. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.83653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg ES, Asbell PA. Essential fatty acids in the treatment of dry eye. Ocul Surf. 2010;8(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(12)70214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roncone M, Bartlett H, Eperjesi F. Essential fatty acids for dry eye: a review. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33(2):49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oleñik A, Jiménez-Alfaro I, Alejandre-Alba N, Mahillo-Fernández I. A randomised, double-masked study to evaluate the effect of omega-3 fatty acids supplementation in meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1133–1138. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S48955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinazo-Durán MD, Galbis-Estrada C, Pons-Vázquez S, Cantú-Dibildox J, Marco-Ramírez C, Benítez-del-Castillo J. Effects of a nutraceutical formulation based on the combination of antioxidants and ω-3 essential fatty acids in the expression of inflammation and immune response mediators in tears from patients with dry eye disorders. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:139–148. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S40640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kokke KH, Morris JA, Lawrenson JG. Oral omega-6 essential fatty acid treatment in contact lens associated dry eye. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2008;31(13):141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oleñik A. Effectiveness and tolerability of dietary supplementation with a combination of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and antioxidants in the treatment of dry eye symptoms: results of a prospective study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:169–176. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S54658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhargava R, Kumar P, Phogat H, Kaur A, Kumar M. Oral omega-3 fatty acids treatment in computer vision syndrome related dry eye. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2015;38(3):206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brignole-Baudouin F, Baudouin C, Aragona P, et al. A multicentre, double-masked, randomized, controlled trial assessing the effect of oral supplementation of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids on a conjunctival inflammatory marker in dry eye patients. Acta Ophthalmol. 2011;89(7):e591–e597. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu A, Ji J. Omega-3 essential fatty acids therapy for dry eye syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1583–1589. doi: 10.12659/MSM.891364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu W, Wu Y, Li G, Wang J, Li X. Efficacy of polyunsaturated fatty acids for dry eye syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Rev. 2014;72(10):662–671. doi: 10.1111/nure.12145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bron A, Evans VE, Smith JA. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 2003;22(7):640–650. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200310000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Official Journal of the European Union Commission Regulation (EU) No. 432/2012 of 16 May 2012. [Accessed December 10, 2013]. Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32012R0432&qid=1452674156190&from=EN.

- 21.Bogdanov P, Domingo JC. Docosahexaenoic acid improves endogen antioxidant defense in ARPE-19 cells; Poster presented at: ARVO Congress; May 1, 2008; Poster 5932/A306. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domingo P, Joan C, Villegas G, Jose A, inventor. Brudy Technology, S.L., assignee Use of DHA for treating pathology associated with cellular oxidative damage. EP1962825. patent. 2015 Jul 31;

- 23.Messmer EM. The pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of dry eye disease. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int. 2015;112(5):71–81. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2015.0071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drouault-Holowacz S, Bieuvelet S, Rigal D, et al. Antioxidants intake and dry eye syndrome: a crossover, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19(3):337–342. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortina MS, Bazan HE. Docosahexaenoic acid, protectins and dry eye. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2011;14(2):132–137. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328342bb1a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miljanović B, Trivedi KA, Dana MR, Gilbard JP, Buring JE, Schaumberg DA. Relation between dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids and clinically diagnosed dry eye syndrome in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(4):887–893. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.4.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Downie LE, Keller PR, Vingrys AJ. An evidence-based analysis of Australian optometrists’ dry eye practices. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90(12):1385–1395. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0000000000000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foulks GN, Forstot SL, Donshik PC, et al. Clinical guidelines for management of dry eye associated with Sjögren disease. Ocul Surf. 2015;13(2):118–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.University of Pennsylvania Dry Assessment and Management Study (DREAM) [Accessed November 17, 2015]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02128763?term=dream%26rank=5. NLM identifier: NCT02128763.