Abstract

In eukaryotes, the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) regulates the ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of specific cell cycle proteins to coordinate chromosome segregation in mitosis and entry into G1 (refs 1,2). The APC/C’s catalytic activity and ability to specify the destruction of particular proteins at different phases of the cell cycle are controlled by its interaction with two structurally related coactivator subunits (Cdc20 and Cdh1). Coactivators recognize substrate degrons3, and enhance the APC/C’s affinity for its cognate E2 (refs 4–6). During mitosis, cyclin-dependent kinase and polo kinase control Cdc20 and Cdh1-mediated activation of the APC/C. Hyper-phosphorylation of APC/C subunits, notably Apc1 and Apc3, is required for Cdc20 to activate the APC/C7–12, whereas phosphorylation of Cdh1 prevents its association with the APC/C9,13,14. Since both coactivators associate with the APC/C through their common C box15 and IR (Ile-Arg) tail motifs16,17, the mechanism underlying this differential regulation is unclear, as is the role of specific APC/C phosphorylation sites. Here, using cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and biochemical analysis, we define the molecular basis of how APC/C phosphorylation allows for its control by Cdc20. An auto-inhibitory (AI) segment of Apc1 acts as a molecular switch that in apo unphosphorylated APC/C interacts with the C-box binding site and obstructs engagement of Cdc20. Phosphorylation of the AI segment displaces it from the C-box binding site. Efficient phosphorylation of the AI segment, and thus relief of auto-inhibition, requires the recruitment of Cdk-cyclin-Cks to a hyper-phosphorylated loop of Apc3. We also find that the small molecule inhibitor, tosyl-L-arginine methyl ester (TAME), preferentially suppresses APC/CCdc20 rather than APC/CCdh1, and interacts with both the C-box and IR-tail binding sites. Our results reveal the mechanism for the regulation of mitotic APC/C by phosphorylation and provide a rationale for the development of selective inhibitors of this state.

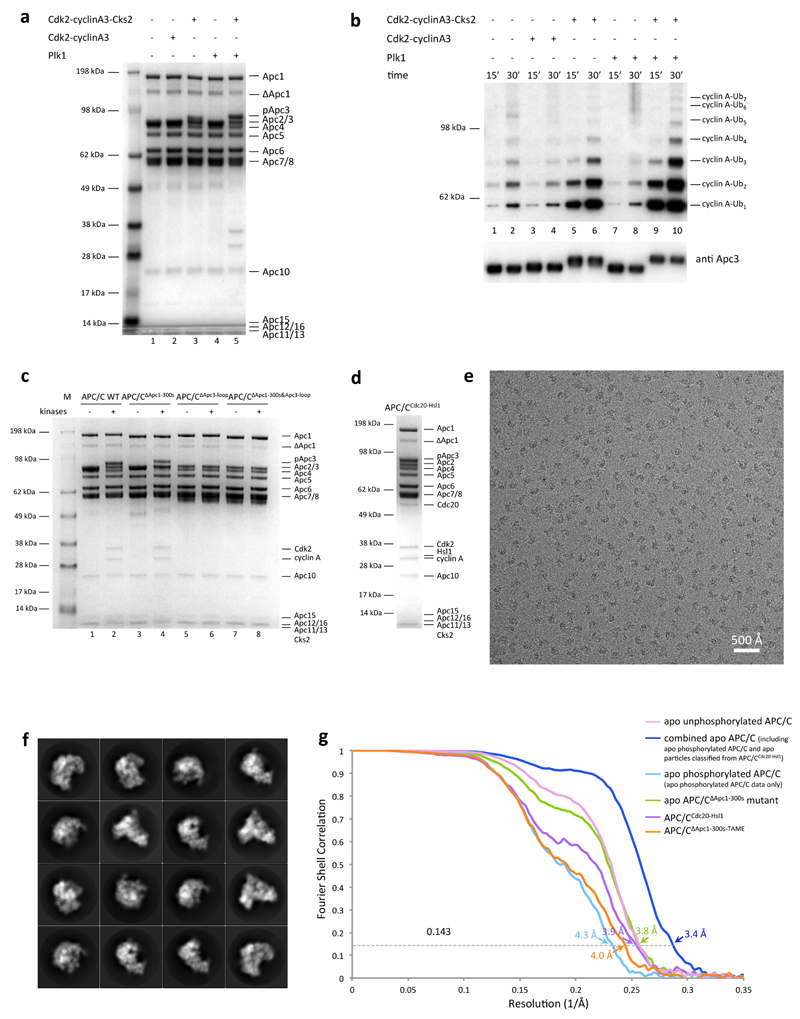

To understand how multi-site phosphorylation of numerous APC/C subunits stimulates the capacity of Cdc20 to control the APC/C we determined a series of APC/C structures in different functional states to near-atomic resolution (Extended Data Table 1a). We used the kinases Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 and Polo (Plk1) to in vitro phosphorylate recombinant human APC/C11,12,18,19 (Extended Data Fig. 1a), obtaining APC/C in the mitotic state that can be activated by Cdc20 (Extended Data Fig. 1b lanes 9, 10). This reconstituted APC/C recapitulates Cdk and Plk1-dependent activation of endogenous APC/CCdc20 (refs 8–12). Kinase treatment resulted in a complete upshift of the Apc3 subunit as visualized on SDS-PAGE, indicative of stoichiometric phosphorylation (Extended Data Fig. 1a, b). Almost 150 phosphorylation sites were identified in phospho-APC/C by mass spectrometry (Extended Data Tables 2 and 3), matching published data12,20–22. These sites lie within disordered regions of the APC/C 23. Incubating the APC/C with both Cdk2 and Plk1 simultaneously was necessary to obtain full activation (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Consistent with12, treatment with Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 alone resulted in lower APC/C activation, whereas phosphorylation with Plk1 alone did not activate the APC/C.

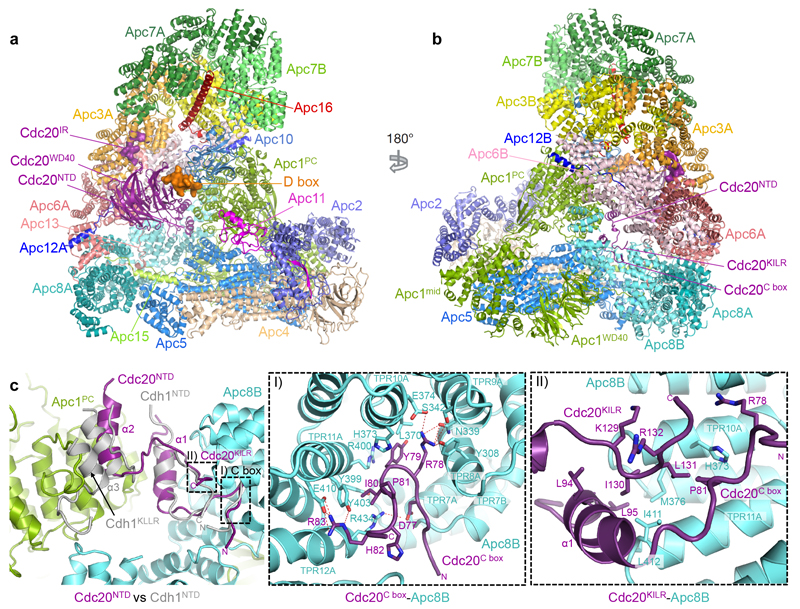

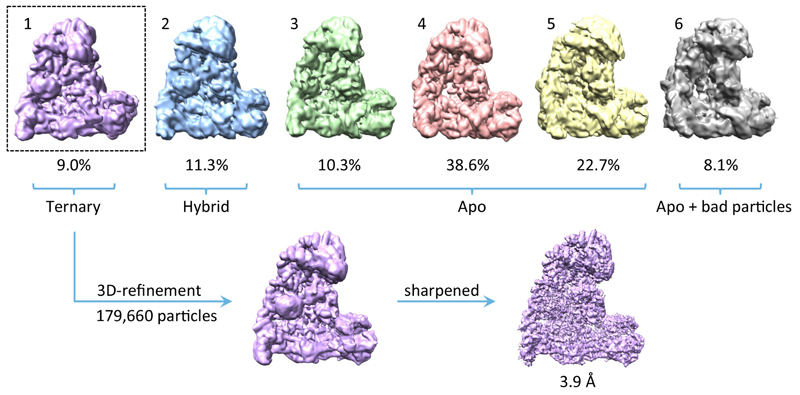

To gain insights into the molecular interactions between Cdc20 and mitotic APC/C, a ternary complex was assembled using phosphorylated APC/C, Cdc20 and a high affinity substrate Hsl1 (APC/CCdc20-Hsl1) (Extended Data Fig. 1d) for cryo-EM analysis (Fig. 1a, b, Extended Data Fig. 1e-g, Extended Data Table 1). Due to the low occupancy of Cdc20 bound to the APC/C, combined with conformational heterogeneity, only 9% of the particles were used for the final reconstruction of APC/CCdc20-Hsl1, with the remainder being in either the apo state (72%) or in a hybrid state (Extended Data Fig. 2). Most static regions of the complex extend beyond 3.9 Å resolution, whereas the catalytic module (Apc2 and Apc11), as well as the WD40 domain of Cdc20, are more flexible (Extended Data Fig. 3a).

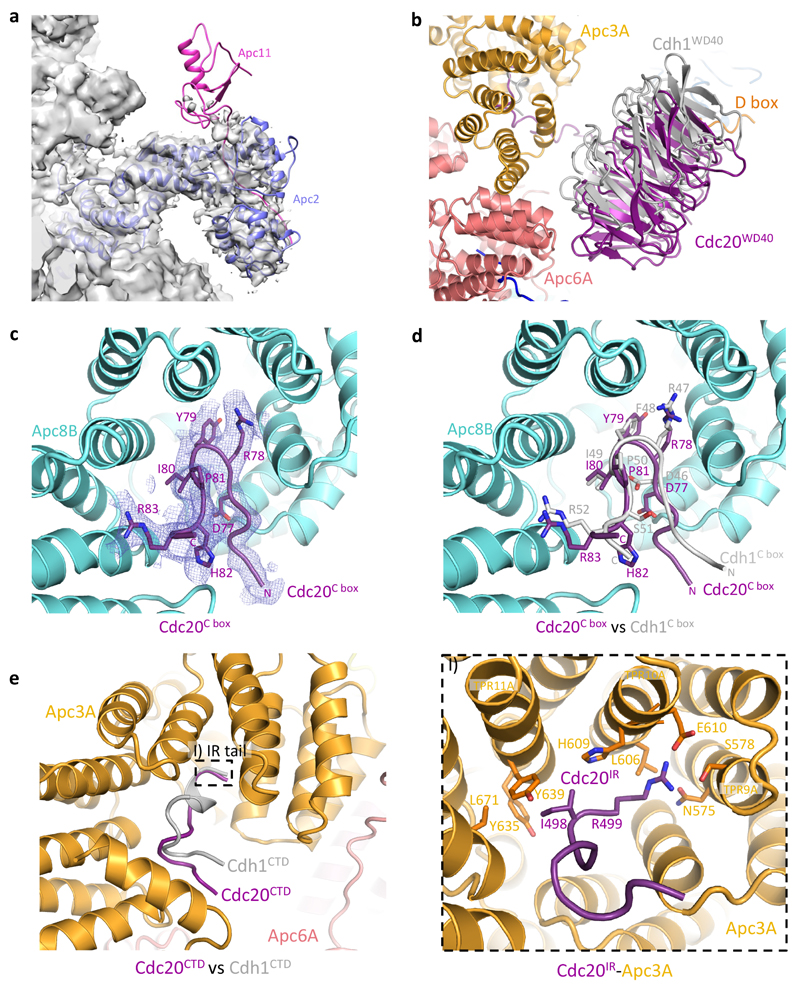

Figure 1. EM reconstructions of the APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 complex and comparison of Cdc20NTD and Cdh1NTD.

a, b, Two views of APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 shown in cartoon with the D box and Cdc20IR highlighted in surface representation. Cdc20 binds to the APC/C in juxtaposition to Apc10 to form the substrate recognition module. Apc11 is modelled based on the APC/CCdh1-Emi1 structure (PDB 4UI9)22. c, Both Cdc20NTD (purple) and Cdh1NTD (grey, aligned to APC/CCdc20-Hsl1)23 interact with Apc1 and Apc8B , whereas Cdh1NTD contains an additional α3-helix associating with Apc1. I) The crucial C box motif is well conserved between the two coactivators and forms extensive interactions with Apc8B. II) The KLLR motif of Cdh1 is present in the α3-helix to engage Apc1, whereas the related Cdc20KILR motif contacts Apc8B to augment C-box binding.

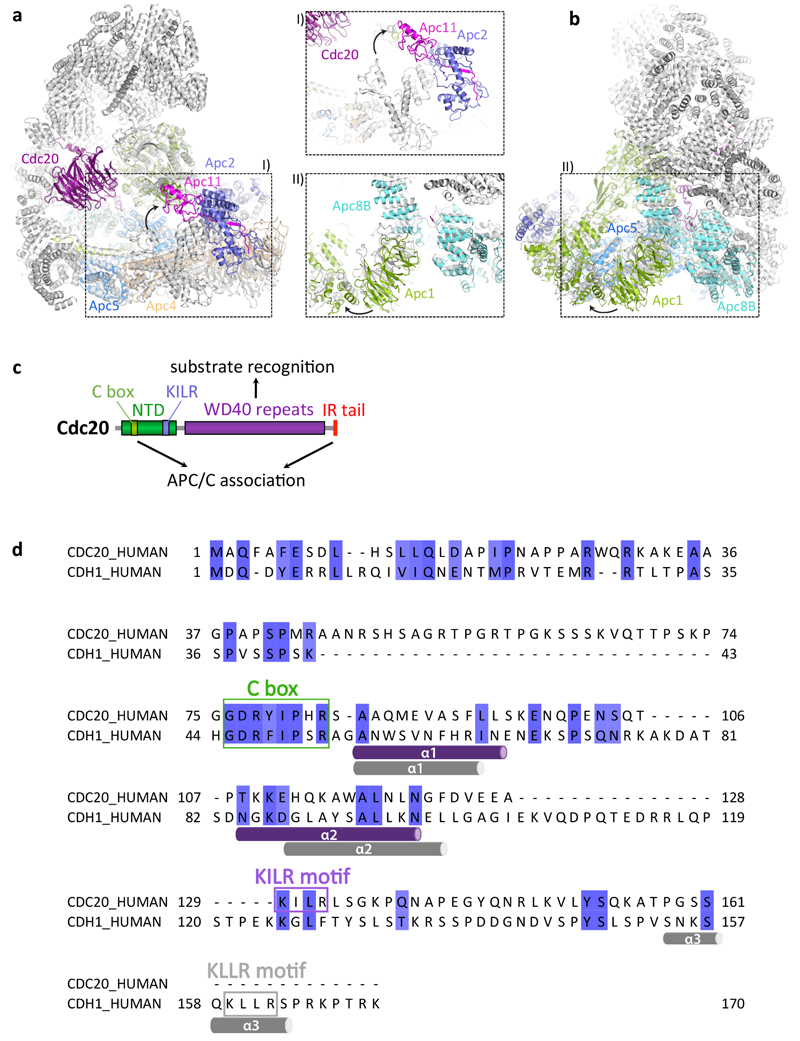

APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 adopts an active conformation with the catalytic module in the upward position reminiscent of APC/CCdh1-Hsl1 (ref. 6) (Fig. 1a, b, Extended Data Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Video 1) and in agreement with a low-resolution negative-stain EM reconstruction of APC/CCdc20 (ref. 24). Relative to Cdh1WD40, the Cdc20WD40 domain is shifted away from the APC/C by as much as 10 Å (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Its interaction with the APC/C involves only its N-terminal domain (Cdc20NTD) and the C-terminal IR tail (Cdc20IR) (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 3c-e, 4c, d). Compared with Cdh1NTD, Cdc20NTD forms fewer contacts with both Apc1 and Apc8B (Fig. 1c). However, the crucial C box motif (DRYIPxR) represents a structurally conserved region common to both coactivators (Fig. 1c I, Extended Data Fig. 3c, d, 4d). The Cdc20C box forms a network of electrostatic interactions with Apc8B, centred on a crucial Arg78 (ref. 23), and augmented by non-polar interactions involving its Tyr79 and Ile80 residues (Fig. 1c I). A KILR motif also present within Cdc20NTD is essential for Cdc20 association with the APC/C25 and the APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 structure reveals that Ile130 and Leu131 of Cdc20KILR are inserted into a hydrophobic pocket of the TPR (tetratricopeptide repeat) superhelix of Apc8B, further stabilizing the conformation of the C box (Fig. 1c II). Similar C-box stabilization is present in Cdh1NTD, but is instead provided by a loop structurally unrelated to Cdc20KILR (Fig. 1c)23. By contrast, the KLLR-motif of Cdh1NTD is located in a leucine zipper-like α-helix (α3) that forms a hydrophobic interface with Apc1 (ref. 23) (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 4d). The absence of an equivalent to the Cdh1 α3-helix in Cdc20 suggests a weaker mode of binding of Cdc20NTD relative to Cdh1NTD.

EM density for Cdc20IR is weaker than for Cdh1IR and it lacks the associated α-helix of Cdh1IR (Extended Data Fig. 3e). This could account for the lower affinity of the APC/C for Cdc20IR compared with Cdh1IR (ref. 17). Nonetheless, the crucial Ile-Arg interaction of Cdc20IR with the TPR superhelix of Apc3A is conserved between the two coactivators (Extended Data Fig. 3e I). Importantly, because in the APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 EM structure, densities corresponding to phosphorylated residues are not visible, we find no evidence that phosphorylated regions of the APC/C either directly or indirectly contact Cdc20. This suggested that APC/C phosphorylation invokes a conformational change of apo APC/C that promotes its association with Cdc20.

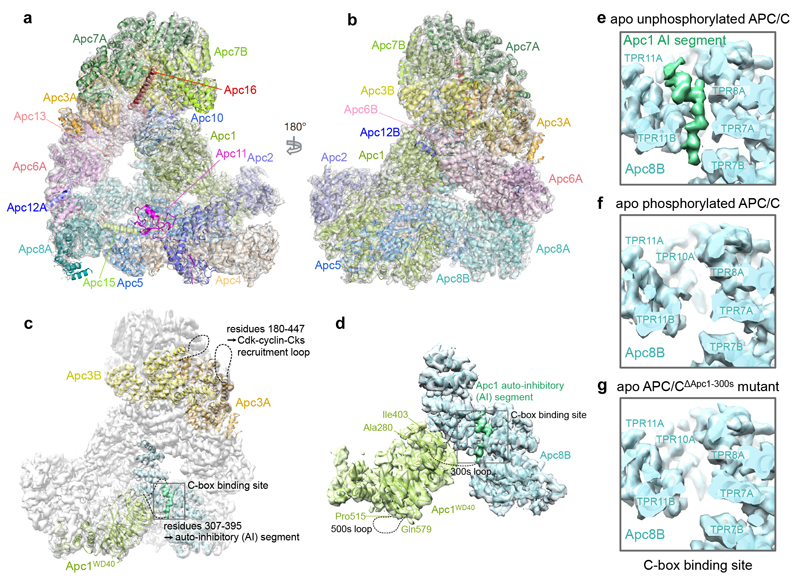

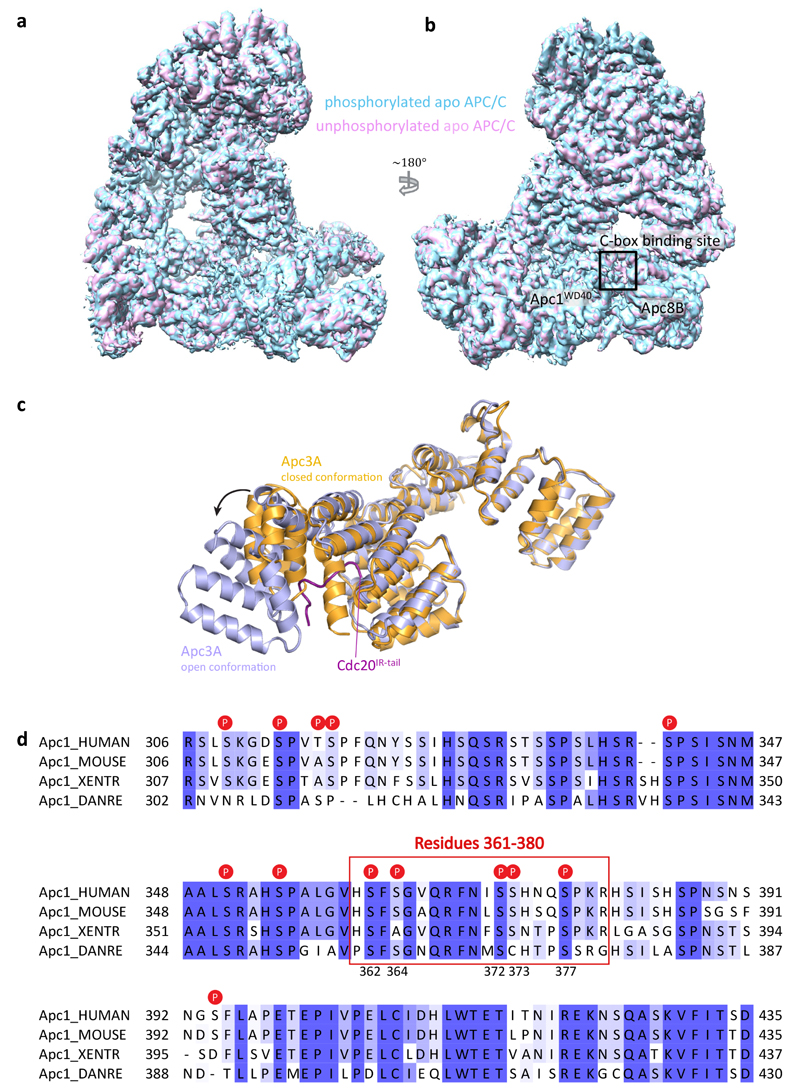

To explore this possibility, we determined cryo-EM structures of apo APC/C in both the unphosphorylated and phosphorylated states at near-atomic resolution (Fig. 2a, b and Extended Data Fig. 5a, b, Extended Data Table 1 and Supplementary Video 1). In both states, the catalytic module adopts an inactive conformation (Extended Data Fig. 4a, b) as seen in the previous 8 Å resolution reconstruction6. However, three-dimensional classification of the atomic resolution EM maps of both apo states showed that the majority of Apc3A adopts a closed conformation resembling the Apc3 crystal structure in which an α-helix (TPR12A) occupies and blocks the IR-tail binding pocket (Extended Data Fig. 5c)26. In ~30% of particles Apc3A adopts an open conformation identical to the IR tail-bound state. Thus interconversion of Apc3A between closed and open-IR tail accessible states is not controlled by phosphorylation.

Figure 2. Apo unphosphorylated APC/C is repressed by an Apc1 auto-inhibitory (AI) segment.

a, b, Two views of the phosphorylated apo APC/C structure in cartoon within the 3.4 Å EM map (grey). The catalytic module (Apc2 and Apc11) is in the inactive conformation. c, d, an EM map of unphosphorylated APC/C. Apc1 has two highly phosphorylated loops within its WD40 domain (green). Whereas the 300s loop (residues 307-395) is pointing towards the Apc1 AI segment density (dark green) at the C-box binding site (dark grey box), the 500s loop is facing in the opposite direction. The hyper-phosphorylated Apc3 loop (residues 180-447) is located at the back of APC/C and functions as a Cdk recruitment site. The views in b and c are similar to Fig. 1b. e-g, Close-up views of the C-box binding site in the EM maps of apo unphosphorylated and phosphorylated APC/C and an APC/CΔApc1-300s mutant with the Apc1 300s loop deleted. An elongated loop density (dark green) for the Apc1 AI segment was observed in the apo unphosphorylated state (e), but the density is absent in apo phosphorylated APC/C (f). Deletion of the Apc1 300s loop shows a similar loss of C-box site associated density (g).

Phosphorylated and unphosphorylated apo APC/C EM maps are very similar in structure (Extended Data Fig. 5a, b), except for a significant difference in the region of the C-box binding site (Fig. 2c-f). In unphosphorylated APC/C, an unassigned segment of EM density of ~15 residues indicative of an elongated loop connected to a short α-helix is located at the C-box binding pocket of Apc8B (Fig. 2c-e). The equivalent EM density is not present in phosphorylated APC/C (Fig. 2f). The Apc1WD40 domain, positioned in close proximity to this density, incorporates two highly phosphorylated regions (residues 307-395 [300s loop] and residues 515-579 [500s loop]) (Fig. 2c, d, Extended Data Table 2), which have not previously been assigned in either APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 or APC/CCdh1-Emi1 structures23. The 300s loop would be predicted to project towards the C-box binding site of Apc8B (Fig. 2c, d, Extended Data Fig. 5d), implicating it as a candidate for the unassigned density segment.

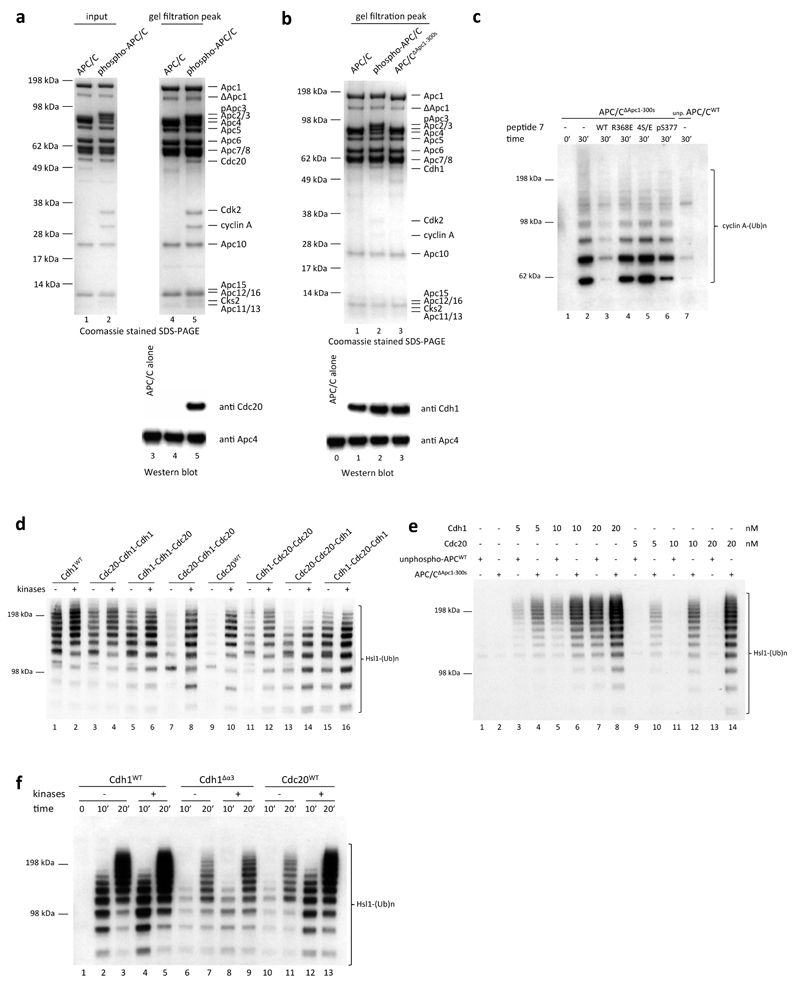

We determined the structure of an APC/C mutant with the 300s loop of Apc1 deleted (APC/CΔApc1-300s) (Fig. 2g and Extended Data Table 1a). In this structure, the C-box binding pocket of APC/CΔApc1-300s is devoid of EM density even without in vitro phosphorylation (Fig. 2g), consistent with its assignment to the 300s loop. Furthermore, ubiquitination assays showed that APC/CΔApc1-300s was constitutively activated by Cdc20 and that phosphorylation did not enhance its activity (Fig. 3a compare lanes 6, 7 to 8, 9). This indicates that unphosphorylated APC/C is maintained in an auto-inhibited conformation by an Apc1 auto-inhibitory (AI) segment, present within the 300s loop that sterically impedes the C-box site from binding Cdc20. In support of this idea, analytical size exclusion chromatography showed that Cdc20 forms a binary complex with phosphorylated APC/C, but not with unphosphorylated APC/C (Extended Data Fig. 6a), in agreement with10,12.

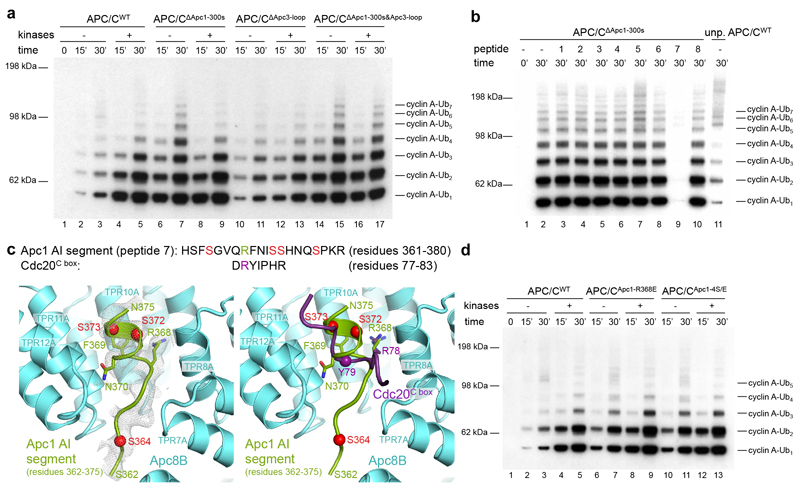

Figure 3. The Apc1 AI segment binds to the C-box binding site and mimics the Cdc20C box.

a, Cdk2-cyclin A2-Cks2 was used for ubiquitination assays. In vitro phosphorylated APC/C (both Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 and Plk1) can be activated by Cdc20 (lanes 1-5). Deletion of the Apc1 300s loop activated the APC/C without phosphorylation (lanes 6-7), and kinase treatment of APC/CΔApc1-300s does not enhance APC/C activity. The APC/CΔApc3-loop mutant showed similar activity as unphosphorylated APC/C (lanes 10-11 vs 2-3 and 4-5), but had reduced activation by phosphorylation. Nevertheless, deletion of both Apc1 300s and Apc3 loops (APC/CΔApc1-300s&Apc3-loop) restored activity to that of WT phosphorylated APC/C and unphosphorylated APC/CΔApc1-300s (lanes 14-17). b, Identification of the Apc1 AI segment occupying the C-box binding site by assessing the inhibitory effect of eight peptides spanning the Apc1 300s loop. A single peptide (peptide 7, residues 361-380) suppressed the activity of APC/CΔApc1-300s (lane 9), indicating that this peptide blocks the C-box binding site. A control with WT unphosphorylated APC/C (unp.APC/CWT) is in lane 11. c, The Apc1 AI segment (peptide 7, residues 361-380) shares sequence similarity with Cdc20C box. A model for the AI segment (green) was fitted into the EM density of the apo unphosphorylated APC/C map (grey). Arg368 overlaps with the crucial Arg78 of Cdc20C box (purple, right panel). The flanking serines shown to be phosphorylated are highlighted as red spheres. Ser377 is outside the observed EM density. d, Mutation of a single Arg368 residue (APC/CApc1-R368E) or mutating its four neighbouring serine residues (Ser364, Ser372, Ser373, Ser377) to glutamates (APC/CApc1-4S/E) activated the APC/C without phosphorylation. 30 nM Cdc20 was used for assay in a and 20 nM Cdc20 for assays in b and d. Experiments in a and d were replicated three times and in b five times. See Supplementary Fig.1 for gel source data.

To identify the AI segment within the Apc1 300s loop, we synthesized a set of eight overlapping peptides of 20 residues, spanning the 300s loop, and tested their potential to inhibit APC/CΔApc1-300s (Fig. 3b). Strikingly, peptide 7 (residues 361-380, Fig. 3b lane 9) potently suppressed Cdc20-dependent APC/CΔApc1-300s activity. Interestingly, an Arg368-Phe369 pair of this peptide, that resembles the Arg78-Tyr79 of the C box, is flanked by four serine residues phosphorylated in mitotic APC/C (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Table 2)12,21,22.

EM density for the AI segment is weak, probably due to partial occupancy at the C-box site (Fig. 3c). Nevertheless, side chain density similar to Arg78-Tyr79 of the C box suggests a fit for the Arg-Phe of peptide 7 (Arg368-Phe369) (Fig. 3c). To test the possibility that the Apc1 AI segment corresponds to peptide 7, we synthesized mutants of peptide 7 and also introduced the equivalent mutations into Apc1 of the recombinant APC/C. Significantly, replacing Arg368 with Glu in Apc1 resulted in a Cdc20-dependent activation of unphosphorylated APC/C (Fig. 3d), and reduced the inhibitory potency of peptide 7 towards APC/CΔApc1-300s (Extended Data Fig. 6c). A similar result was obtained on substituting glutamates for the four neighbouring serine residues (Ser364, Ser372, Ser373 and Ser377 [APC/CApc1-4S/E]) to mimic phosphorylation (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 6c). Phosphorylation of Ser377 of peptide 7 relieved the inhibition only partially. These findings suggest that Arg368 anchors the Apc1 AI segment to the C-box binding site, mimicking the Cdc20C box, and maintaining the apo APC/C in an auto-inhibited state. Phosphorylation of the four neighbouring serine residues would destabilize its association with the C-box site (Fig. 3c, 4a). This mechanism could be further tested in the in vivo context by cellular assays.

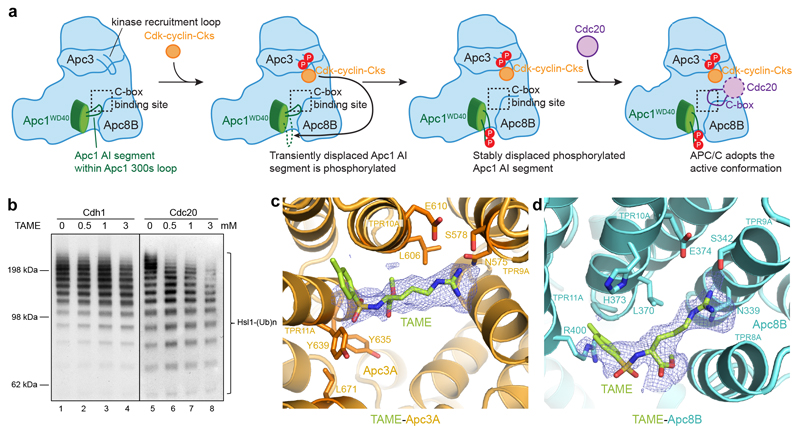

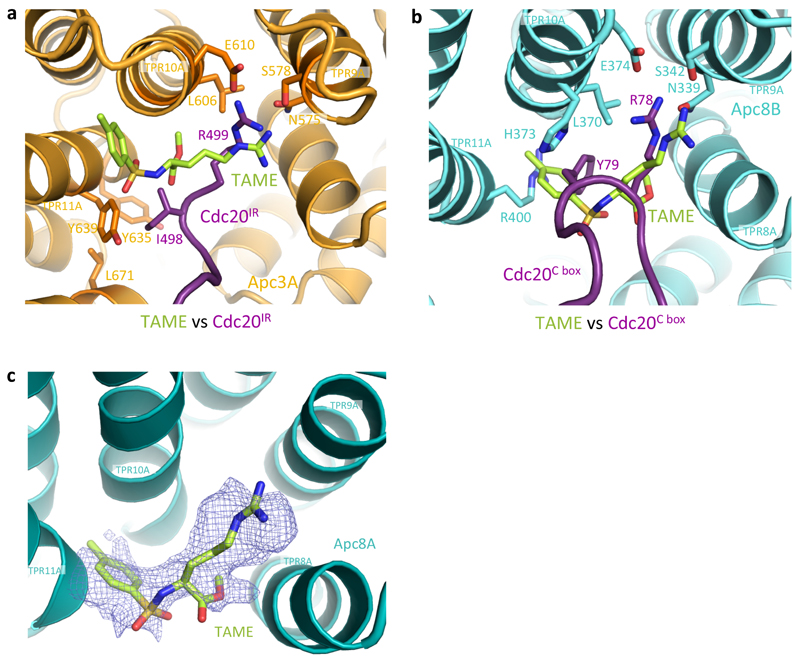

Figure 4. Mechanism for APC/C activation by mitotic phosphorylation and the molecular basis for TAME inhibition.

a, Cartoon showing the mechanism of APC/C activation by Apc1 and Apc3 phosphorylation induced relief of auto-inhibition. Artificial relief of AI segment auto-inhibition, either by its deletion or by phospho-mimicking mutants, obviates the need to phosphorylate Apc3. b, TAME has only a small inhibitory effect on APC/CCdh1 (lanes 1-4), whereas it significantly reduced APC/CCdc20 activity (lanes 5-8). The activity assay was performed with phosphorylated WT APC/C and substrate Hsl1 at a coactivator concentration of 10 nM. This experiment was replicated three times. See Supplementary Fig.1 for gel source data. c, d, EM reconstruction of APC/CΔApc1-300s in complex with TAME showed densities (dark blue) for TAME (C-atoms in limon) at both the IR-tail binding site (c), and the C-box binding site (d). Their positions overlap well with the crucial Arg78 and Tyr79 of Cdc20C box and Ile498 and Arg499 of Cdc20IR thereby inhibiting Cdc20 association (Extended Data Fig.7).

Our results so far reveal that the critical determinant of APC/CCdc20 activation by phosphorylation is displacement of the Apc1 AI segment from the C-box site. However, since Apc3 is hyper-phosphorylated in mitosis, and Cks stimulates both Cdk-dependent activation of APC/CCdc20 (refs 18,19) and Apc1 and Apc3 phosphorylation18, and interacts with Apc3 (refs 18,27,28), we tested whether Apc3 phosphorylation also had a role in APC/C activation. In Apc3 about 50 phospho-sites are clustered in a large disordered loop comprising residues 180-450 (Extended Data Table 2) located on the same face of the APC/C as the Apc1 300s loop (Fig. 2c). In contrast to APC/CΔApc1-300s, instead of stimulating unphosphorylated APC/C, deletion of the Apc3 loop (APC/CΔApc3-loop) reduced the phosphorylation-mediated activation of APC/C (Fig. 3a lanes 10-13). Similarly, Cdk2-cyclin A3 failed to stimulate the APC/C activity in the absence of Cks2 (Extended Data Fig. 1b). However, combining deletions of both the Apc3 and Apc1 300s loops (APC/CΔApc1-300s&Apc3-loop) restored activity to that of wild type (WT) phosphorylated APC/C (Fig. 3a lanes 14-15). Since deletion of the Apc3 loop disrupts APC/C association with Cdk-cyclin-Cks (Extended Data Fig. 1c, lanes 6, 8), a likely explanation for our results and for the lag phase that accompanies APC/C activation by Cdk1-cyclin B-Cks19, is that Apc3 phosphorylation recruits Cdk-cyclin-Cks through Cks18,27,28 to stimulate Apc1 AI segment phosphorylation. Cdk-cyclin-Cks association with the Apc3 loop would allow for a kinetically more efficient intra-molecular phosphorylation of the Apc1 AI segment that only becomes accessible to Cdk when transiently displaced from the C-box site (Fig. 3c, 4a).

To determine whether Apc3 loop-mediated interactions with the Cks2 subunit facilitated Apc1 300s loop phosphorylation, we analysed phosphorylation of the Apc1 300s loop in conditions where such interactions are disrupted. Either deletion of the Apc3 loop or omission of the Cks2 subunit from the phosphorylation reaction, conditions that reduce APC/C activation (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 1b), resulted in the same reduction of Apc1 300s loop phosphorylation (Extended Data Table 2). Specifically, mitotic phospho-sites associated with relief of AI segment auto-inhibition (Ser364, Ser372 and Ser373) (Extended Data Table 2, columns 3 and 8) are not modified when Cdk targeting to Apc3 is disrupted (Extended Data Table 2, columns 4 and 5). In agreement with 12,22 Ser362 and Ser364 are phosphorylated by Plk1 and Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2, respectively, indicating that Ser364 phosphorylation confers partial activation, whereas phosphorylation of Ser372 and Ser373 requires the presence of both kinases, possibly due to inter-dependent priming reactions. Since the stimulatory phosphoSer364 of the AI segment (Fig. 3c) is a non Cdk-consensus site, the relaxed specificity of Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 phosphorylation of this site may be conferred through targeting of the kinase to the APC/C through the Apc3 loop.

Cdc20 and Cdh1 bind to common sites on the APC/C yet only Cdc20 association is regulated by APC/C phosphorylation. In agreement with9, we find that Cdh1 activates unphosphorylated and phosphorylated APC/C to a similar extent (Extended Data Fig. 6d, e). Comparing unphosphorylated APC/C and APC/CΔApc1-300s we detect some stimulation with APC/CΔApc1-300s at low Cdh1 concentrations (Extended Data Fig. 6e) . This is consistent with the enhancement of Cdh1 binding to phosphorylated APC/C and APC/CΔApc1-300s (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Testing the phosphorylation-dependent activity of a set of Cdc20-Cdh1 chimeras indicated that the more extensive interactions involving Cdh1 and the APC/C, mediated by both Cdh1NTD and Cdh1IR (Extended Data Fig. 6d), with a contribution from the Cdh1NTD-α3 helix (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 6f), account for the capacity of Cdh1 to activate unphosphorylated APC/C. Although Cdh1 association would also require displacement of the Apc1 AI segment, a potential mechanism to explain the dependency of Cdc20 on APC/C phosphorylation is that the higher affinity of Cdh1 for the APC/C (Extended Data Fig. 6e) is sufficient to compete for the AI segment at the C-box binding site.

Our findings suggest the interesting possibility of exploiting differences in the affinities of the two coactivators for the design of inhibitors that specifically target mitotic APC/CCdc20 and thus suppress cell proliferation. A small molecule, tosyl-L-arginine methyl ester (TAME), was reported to inhibit APC/C activation by both Cdc20 and Cdh1 through a proposed mechanism involving competition for the IR-tail binding site of coactivator29. However, we found that TAME is a more potent inhibitor of APC/CCdc20 than APC/CCdh1 (Fig. 4b). To understand the molecular basis underlying this inhibition, we determined the structure of APC/CΔApc1-300s in complex with TAME (Extended Data Table 1). We observed TAME density not only at the IR-tail binding site, but also at the C-box binding site (Fig. 4c, d). This is consistent with the structural similarities of the IR-tail and C-box bindings sites of Apc3A and Apc8B, respectively23, although there are critical differences. In Apc3A, TAME is reminiscent of the Ile-Arg motif of the coactivator IR tail, whereas in Apc8B, TAME resembles the Arg-Tyr/Phe of the coactivator C box (Extended Data Fig. 7). The mechanism of TAME inhibition of APC/CCdc20 through a tosyl-Arg motif to block the Cdc20 C-box binding site is reminiscent of the Apc1 AI segment that is displaced by APC/C phosphorylation. Both utilize a common structural motif (Arg-aromatic) that mimics Arg78 and Tyr79 of the Cdc20C box to exploit the lower (relative to Cdh1) affinity of Cdc20 for the APC/C.

How phosphorylation regulates mitotic APC/C activation by Cdc20 has been a long-standing puzzle. Our in vitro studies show that of almost 150 phospho-sites in mitotic APC/C, only a few in Apc1 directly regulate Cdc20 binding through displacement of the AI segment. This study has relevance to understanding the control of other large multimeric complexes by multi-site phosphorylation.

Methods

Expression and purification of recombinant human APC/C

The genes for recombinant human APC/C were cloned into a modified MultiBac system, expressed and purified as described30. The C-terminus of Apc4 was fused to a TEV (tobacco etch virus)-cleavable StrepIIx2 tag.

Protein kinase purification

All four proteins (Cdk2, cyclin A3 [residues 174-432], Cks2 and Plk1) for the kinases were expressed individually in BL21 (DE3) Star cells at 18°C overnight. Pellets containing GST-tagged Cdk2, His-tagged cyclin A3 and His-SUMO-tagged Cks2 were combined and resuspended in the CDK lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.4, 180 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 2 mM DTT) supplemented with 0.1 mM PMSF, lysozyme, 5 units/ml benzonase and CompleteTM EDTA-free protease inhibitors. After sonication, the cells were centrifuged at 20,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C and the supernatant was incubated with the Glutathione Sepharose™ 4B (GE Healthcare) for 3 h at 4°C. The resins were washed with the CDK lysis buffer and the GST-tag of Cdk2 was cleaved off with 3C PreScission protease overnight at 4°C. The flow-through from the resins was collected and TEV cleaved overnight at 4°C. Finally, the protein complex was purified by a Superdex200 16/60 column (GE Healthcare).

The Polo kinase Plk1 with an N-terminal His-MBP tag was purified with a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) in the PLK lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol). The column was washed intensively with high salt buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Proteins were eluted with a gradient of the elution buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol and 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol) followed by TEV-cleavage overnight at 4°C. The sample was re-applied onto the HisTrap HP column to remove the His-tag, uncleaved proteins and nickel contaminations. The collected flow-through was concentrated and loaded onto a Superdex75 16/60 column (GE Healthcare) for final purification.

In vitro phosphorylation of recombinant human APC/C

Concentrated APC/C after Resource Q (QIAGENE) was treated with Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 and Plk1 in a molar ratio of 1 : 1.5 (APC/C : kinases) in a reaction buffer of 40 mM Hepes pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.6 mM DTT with 5 mM ATP and 50 mM NaF. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min before the final purification step by a Superose 6 3.2/300 column (GE Healthcare).

Expression and purification of the substrate Cdk2-cyclin A2-Cks2 and Cdc20

Full length human cyclin A2 was cloned into the pETM41 vector with an N-terminal His-MBP tag. The protein was expressed in BL21 (DE3) Star cells at 18°C overnight. Pellets containing Cdk2, cyclin A2 and Cks2 were co-lysed for purification following a similar protocol as for the kinase purification.

Full length human Cdc20 was cloned into a modified pFastBac HTa vector with an N-terminal His-MBP tag. The generated virus was amplified and expressed in Sf9 cells. Harvested cell pellets were resuspended in Cdc20 lysis buffer (50 mM Hepes pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol and 0.5 mM TCEP) supplemented with 0.1 mM PMSF, 5 units/ml benzonase and CompleteTM EDTA-free protease inhibitors and loaded onto a HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare). Proteins were eluted with a gradient to 300 mM imidazole. Collected peak fractions were TEV-cleaved overnight in the dialysis bag (cutoff 6-8 kDa) against the dialysis buffer (50 mM Hepes, pH 7.8, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol and 0.5 mM TCEP) at 4°C. The protein was re-applied onto the HisTrap HP column and the flow-through was collected.

Complex formation of APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 and APC/CΔApc1-300s-TAME

In vitro phosphorylated APC/C was treated with 40 µM CDK1/2 inhibitor iii (ENZO Life Sciences) before incubating with purified Cdc20 and Hsl1 (with a molar ratio of 1:1.5:2) on ice. The complex was purified by a Superose 6 3.2/300 column using the Microakta system.

TAME (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 50% DMSO and 50% APC/C gel filtration buffer at a concentration of 1 M. 4 mM TAME was added to purified APC/CΔApc1-300s and incubated on ice for 1 hour before freezing cryo-grids.

Ubiquitination assays

The ubiquitination assay was performed with 60 nM recombinant human APC/C, 90 nM UBA1, 300 nM UbcH10, 300 nM Ube2S, 70 µM ubiquitin, 2 µM substrate Cdk2-cyclin A2-Cks2 or Hsl1, 5 mM ATP, 0.25 mg/ml BSA, 15 µM CDK1/2 inhibitor iii and different concentrations of purified human Cdc20 (5-30 nM) or Cdh1 (5-30 nM) in a 10 µl reaction volume with 40 mM Hepes pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.6 mM DTT (figure legends indicate the exact coactivator concentration used in each assay). Reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for various time points and terminated by adding SDS/PAGE loading dye. Reactions were analyzed by 4-12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels followed by Western blotting with an antibody against the His-tag of ubiquitin (Clonetech cat code 631212).

For the chimeric Cdh1-Cdc20 assay, the following domain boundaries were used to generate chimeric Cdh1-Cdc20 proteins: Cdh1NTD (residues 1-168), Cdh1WD40 (residues 169-475), Cdh1IR (residues 476-496), Cdc20NTD (residues 1-165), Cdc20WD40 (residues 166-475), Cdc20IR (residues 476-499). 10 nM of the chimeric proteins were used in the assay.

Peptide and TAME assays

Eight peptides (Designer BioScience) spanning the Apc1 300s loop were synthesized for identification of the Apc1 AI segment. Each peptide contains 20 amino acids, with a ten-residue overlap with the neighbouring peptides: peptide 1 (LTAHLRSLSKGDSPVTSPFQ); peptide 2 (GDSPVTSPFQNYSSIHSQSR); peptide 3 (NYSSIHSQSRSTSSPSLHSR); peptide 4 (STSSPSLHSRSPSISNMAAL); peptide 5 (SPSISNMAALSRAHSPALGV); peptide 6 (SRAHSPALGVHSFSGVQRFN); peptide 7 (HSFSGVQRFNISSHNQSPKR) and peptide 8 (ISSHNQSPKRHSISHSPNSN). The following mutant peptides of peptide 7 were used to assess the relief of inhibition: peptide R368E (HSFSGVQEFNISSHNQSPKR), peptide 4S/E (HSFEGVQRFNIEEHNQEPKR) and peptide pS377 (HSFSGVQRFNISSHNQphosphoSPKR). The peptides were dissolved at a concentration of 10 mM in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and diluted using the APC/C gel filtration buffer. The ubiquitination assay was performed using a final concentration of 200 μM peptide. The TAME assay was performed at a similar condition using 0.5-3 mM TAME and the substrate Hsl1.

Size exclusion chromatography to assess coactivator binding

Purified APC/C samples (1 mg/ml) were incubated with either Cdh1 or Cdc20 at a molar ratio of 1:1.5 on ice for 30 min. The sample was spun down at 13,000 rpm for 5 min to remove any precipitates or aggregates before injecting onto a Superose 6 3.2/300 column using the Microakta system. The eluted peak fractions were analysed by SDS-PAGE and Western-blotting.

Mass Spectroscopy

Purified proteins were prepared for mass spectrometric analysis by in solution enzymatic digestion, without prior reduction and alkylation. Protein samples were digested with trypsin or elastase (Promega), both at an enzyme to protein ratio of 1:20. The resulting peptides were analysed by nano-scale capillary LC-MS/MS using an Ultimate U3000 HPLC (ThermoScientific Dionex) to deliver a flow of approximately 300 nl/min. A C18 Acclaim PepMap100 5 µm, 100 µm × 20 mm nanoViper (ThermoScientific Dionex), trapped the peptides prior to separation on a C18 Acclaim PepMap100 3 µm, 75 µm × 250 mm nanoViper (ThermoScientific Dionex, San Jose, USA). Peptides were eluted with a 90 min gradient of acetonitrile (2% to 50%). The analytical column outlet was directly interfaced via a nano-flow electrospray ionization source, with a hybrid quadrupole orbitrap mass spectrometer (Q-Exactive Plus Orbitrap, ThermoScientific). LC-MS/MS data were then searched against an in house LMB database using the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science) 31, and the peptide identifications validated using the Scaffold program (Proteome Software Inc.)32. All data were additionally interrogated manually.

Electron microscopy

Freshly purified APC/C samples were first visualized by negative-staining EM to check the sample quality and homogeneity and to get initial low-resolution reconstructions. Micrographs were recorded on an FEI Spirit electron microscope at an accelerating voltage of 120 kV and at a defocus of approximately -1.5 µm. For cryo-EM, 2 µl aliquots of the sample at ~0.15 mg/ml were applied onto the Quantifoil R2/2 grids coated with a layer of continuous carbon film (approximately 50 Å thick). Grids were treated with a 9:1 argon:oxygen plasma cleaner for 20 to 40 s before use. The grids were incubated for 30 s at 4°C and 100% humidity before blotting for 5 s and plunging into liquid ethane using an FEI Vitrobot III. The grids were loaded into an FEI Tecnai Polara electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 300 kV. Micrographs were taken using EPU software (FEI) at a nominal magnification of 78,000 which yields a pixel size of 1.36 Å/pixel. They were recorded by an FEI Falcon III direct electron detector with a defocus range of -2.0 to -4.0 µm. The exposure time for each micrograph was 2s at a dose rate of 27 electrons/Å2/s. 34 movie frames were recorded for each micrograph as described33.

Image processing

All movie frames were aligned by motioncorr program34 before subsequent processing. First, the contrast transfer function parameters were calculated with CTFFIND3 or Gctf 35,36. Particles in 264 pixels x 264 pixels were selected by automatic particle picking in RELION 1.4 (ref. 37). The following steps were performed to exclude bad particles from the dataset: 1) automatically picked particles in each micrograph were screened manually to remove ice contaminations38; 2) after particle sorting in RELION, particles with poor similarity to reference images were deleted; 3) 2-dimensional classification was performed and particles in bad classes with poorly recognizable features were excluded. The remaining particles were divided into six classes using three-dimensional classification in RELION. During this process particles with conformational heterogeneity and leftover bad particles were removed from the final reconstruction. After 3D-refinement, beam-induced particle motion was corrected using particle polishing in RELION33,39. All resolution estimations were based on the gold-standard Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) calculations using the FSC = 0.143 criterion. The model for the apo state (Fig. 2a, b, combined apo APC/C structure) was built based on a 3.4 Å resolution map, reconstructed by combined data collected from pure apo phosphorylated APC/C and the apo state particles classified from the APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 complex (Extended Data Fig. 2, Extended Data Table 1). This map allowed for model building of regions which were less well resolved and presented as poly-alanines in the previous APC/CCdh1-Emi1 structure23, including Apc2NTD, Apc1 loops in both the WD40 domain and the middle domain and regions in Apc5NTD. A summary of all EM reconstructions obtained in this work is listed in Extended Data Table 1a.

Model building

Model building of both apo APC/C and APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 structures were performed in COOT40. Initially, available atomic structure of human APC/CCdh1-Emi1 (PDB 4UI9)23 and the crystal structure of Cdc20WD40 (PDB 4GGC)41 were rigid-body fitted in individual subunits into the cryo-EM maps in Chimera42. All fitted structures were rebuilt according to the cryo-EM map. Cdc20NTD, Cdc20CTD and several loop regions not seen in previous structures were built ab initio. The models were refined by REFMAC 5.8 (ref. 43). A REFMAC weight of 0.04 was defined by cross-validation using half reconstructions44. A resolution limit of 3.6 Å or 3.5 Å was used for the APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 and the apo APC/C structure, respectively. All available crystal structures or NMR structures were used for secondary structure restraints. The refinement statistics are summarized in Extended Data Table 1b.

Map Visualization

Figures were generated using Pymol and Chimera42.

Sequence alignment

Sequence alignment was performed using Jalview45.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Preparations and EM images of different APC/C samples used for structural studies.

a, Recombinant human APC/C was in vitro phosphorylated using Cdk2-cyclin A3, Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 or Plk1 alone or with both Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 and Plk1. The phosphorylated APC/C samples are shown on SDS-PAGE. b, In vitro phosphorylated recombinant human APC/C can be fully activated by Cdc20 to ubiquitylate a native substrate Cdk2-cyclin A2-Cks2 when both kinases were added (lanes 9, 10). Without Cks2 (lanes 3, 4) or with Plk1 alone (lanes 7, 8) no activation of the APC/C could be observed, whereas treating with Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 alone (lanes 5, 6) resulted in its partial activation. A time course was recorded at 15 and 30 min and 20 nM of Cdc20 was used. This experiment was replicated three times. Anti-Apc3 antibodies (BD Bioscience, cat. code: 610454) were used as a loading control. c, Purified APC/C WT and mutant samples with and without kinase treatment (both Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 and Plk1). Upon deletion of the Apc3 loop, no association of the Cdk2-cyclin A3-Cks2 kinase to the APC/C could be observed (lanes 6 and 8). d, Purified APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 ternary complex on SDS-PAGE. e, A typical cryo-EM micrograph of APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 representative of 15,582 micrographs. f, Gallery of two-dimensional averages of APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 showing different views; representative of 100 two-dimensional averages. g, Gold-standard FSC curves of all APC/C reconstructions in this work. See Supplementary Fig.1 for gel source data.

Extended Data Figure 2. Three-dimensional classification of APC/CCdc20-Hsl.

The initial particles after 2-dimensional classification were divided into six classes by 3-dimensional classification module using RELION. The resultant classes were grouped into four categories: (i) 9.0% in the active ternary state with coactivator and substrate bound; (ii) 11.3% in a hybrid state with coactivator bound, but the APC/C in the inactive conformation; (iii) 71.6% in the inactive apo state; (iv) 8.1% has poorer reconstruction due to some bad particles. The first class in the active ternary state containing 179,660 particles was used for 3-dimensional refinement and movie correction to obtain the final reconstruction at 3.9 Å.

Extended Data Figure 3. Comparison of Cdc20 and Cdh1 association to the APC/C.

a, The catalytic module (Apc2-Apc11) of the APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 complex is flexible and almost no density accounting for Apc11 (pink, modelled based on the structure of APC/CCdh1-Emi1, PDB 4UI9)23 could be observed. b, The WD40 domain of Cdc20 (purple) occupies a similar position as Cdh1WD40 (grey), but it is displaced from the APC/C by as much as 10 Å. c, d, EM density for Cdc20C box allowed for ab initio model building and the C-box interaction with Apc8B (cyan) is well conserved between the two coactivators. e, Both Cdc20IR and Cdh1IR associates with Apc3A (orange), although the EM density for Cdc20IR is much weaker (not shown) and the C-terminal α-helix in Cdh1IR is absent.

Extended Data Figure 4. Conformational changes of the APC/C between the inactive apo and the active ternary states and domain and sequence analysis of Cdc20.

a, b, Subunits that undergo conformational changes upon coactivator and substrate binding are highlighted in their ternary state and coloured as in Fig. 1, while the corresponding proteins in the inactive apo state are in lighter shades. In the active conformation, the platform subdomain containing subunits Apc1, Apc4 and Apc5 is shifted upward, inducing a large movement of the catalytic module to enable E2 access. c, Domain organization of Cdc20. d, Sequence alignment of Cdc20NTD and Cdh1NTD with α-helices represented as cylinders (purple and grey for Cdc20NTD and Cdh1NTD, respectively) underneath the sequences and the C box and KILR/KLLR motif highlighted.

Extended Data Figure 5. Comparison of apo APC/C in unphosphorylated and phosphorylated states.

a, b, Superposition of the apo unphosphorylated (magenta) and phosphorylated (cyan) APC/C EM maps revealed little conformational differences except in the vicinity of the C-box binding site. c, Apc3A is in an equilibrium between open (light blue) and closed (orange) conformations. While in the inactive apo state, the majority of Apc3A is in the closed state, association of Cdc20IR stabilizes the open state. d, Sequence alignment of the Apc1 300s loop across different species human, mouse, Xenopus tropicalis (Western clawed frog) and Danio rerio (zebrafish). Phosphorylation sites are indicated and residues 361-380 accounting for the Apc1 AI segment are boxed.

Extended Data Figure 6. Analytical gel filtration and activity assays.

a, With equal amount of input Cdc20, phosphorylated APC/C could form a stable binary complex with Cdc20 after a gel filtration purification step (lane 5), whereas unphosphorylated APC/C could not (lane 4). b, Both unphosphorylated and phosphorylated APC/C associate with Cdh1 stably on gel filtration, as well as APC/CΔApc1-300s. Anti Cdc20 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat. code: sc-8358) and anti Cdh1 antibody (Sigma, cat. Code: C7855) were used for detection; antibodies to Apc4 (ref. 6) served as a loading control and unphosphorylated APC/C alone is used as a negative control for Western-blotting. c, Point mutations of peptide 7 (residues 361-380), either when Arg368 was mutated to glutamate or when the four neighbouring serines were mutated to phospho-mimics (Glu), caused the peptide to abolish its inhibition effect and restored the APC/C activity (lanes 4, 5). Phosphorylation of a single Ser377 only resulted in partial activation of the APC/C (lane 6). d, Chimeric proteins composed of the NTD, the WD40 domain and the IR tail of either Cdc20 or Cdh1 were purified to study their differences in APC/C activation. Both the NTD and the CTD of the coactivators are essential for their association with the APC/C. Swapping both NTD and CTD of Cdh1 with Cdc20 makes it phosphorylation sensitive (lanes 7, 8), similar to Cdc20 (lanes 9, 10) and vice versa. e, Upper panel: Cdh1 can activate both unphosphorylated and phosphorylated APC/C similarly, whereas Cdc20 requires APC/C phosphorylation for its activity. Lower panel: A titration of Cdh1 against unphosphorylated APC/C and APC/CΔApc1-300s showed enhanced activity in the absence of the Apc1 AI segment at low Cdh1 concentration (≤ 10 nM), whereas Cdc20 requires displacement of the AI segment for its activity. f, Deletion of the Cdh1 α3-helix resulted in reduced activation of the APC/C and makes Cdh1 more phosphorylation sensitive. The substrate Cdk2-cyclin A2-Cks2 was used for assay in c and Hsl1 for the assays in d-f. 20 nM Cdc20 was used in c, 10 nM chimeric coactivators in d and 30 nM coactivators in f. Experiments in a and b were replicated two times, in c, e and f three times and in d four times. See Supplementary Fig.1 for gel source data.

Extended Data Figure 7. TAME competes with Cdc20 to bind at the IR-tail and the C-box binding sites.

a, TAME (C-atoms in limon) is superimposed with Cdc20IR (purple) and the arginine motif in both structures engages the same binding site on Apc3A (orange). b, The tosyl-Arg motif of TAME overlaps with Arg78-Tyr79 of Cdc20C box at the C-box binding site to out-compete Cdc20. c, A density for TAME was also observed within a pocket of the Apc8A TPR superhelix, similar to that of Apc8B.

Extended Data Table 1. EM data collection, processing statistics and structure refinement statistics.

| a. Statistics of all cryo-EM reconstructions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Samples | Particles used for final reconstruction | Resolution (Å) |

| APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 | 179,660 (9.0%) | 3.9 |

| apo unphosphorylated APC/C | 347,317 (49.5%) | 3.8 |

| apo phosphorylated APC/C (apo phosphorylated APC/C data only) |

83,642 (63.1%) | 4.3 |

| combined apo APC/C (both apo phosphorylated APC/C data a nd apo phosphorylated particles classified from APC/Ccdc2D-Hsl1) |

921,993 (70.8%) | 3.4 |

| apo APC/CΔApc1-300s mutant | 262,090 (80.2%) | 3.8 |

| APC/CΔApc1-300s-TAME | 246,065 (78.2%) | 4.0 |

| b. Statistics of APC/Ccdczo-Hsl1 and combined apo APC/C structure determination | ||

| Data collection | APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 | combined apo APC/C |

| EM | FEI Polara, 300k eV | FEI Polara, 300k eV |

| Detector | FEI Falcon Ill | FEI Falcon Ill |

| Pixel size (Å) | 1.36 | 1.36 |

| Defocus range (µm) | 2.0-4.0 | 2.0-4.0 |

| Reconstruction | ||

| Software | RELION 1.4 | RELION 1.4 |

| Accuracy of rotations (degrees) | 1.268 | 0.884 |

| Accuracy of translations (pixels) | 0.81 | 0.62 |

| Final resolution (Å) | 3.9 | 3.4 |

| Refinement | ||

| Software | RefMac 5.8 | RefMac 5.8 |

| Refmac weight | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Resolution limit (Å) | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| Residue number | 8101 | 7904 |

| Average Fourier shell correlation | 0.6439 | 0.7778 |

| R factor | 0.3815 | 0.3451 |

| Rms bond length (Å) | 0.0125 | 0.0141 |

| Rms bond angle (°) | 1.6973 | 1.7435 |

| Validation | ||

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Preferred | 7544 (93.12%) | 7447 (94.22%) |

| Allowed | 327 (4.04%) | 264 (3.34%) |

| Outliers | 230 (2.84%) | 193 (2.44%) |

Extended Data Table 2. Phosphorylation sites of Apc1 and Apc3 subunits of in vitro phosphorylated APC/C identified by mass spectrometry.

| Protein | Phospho-sites | APC/CWT | APC/CWT | APC/CΔApc3-loop | APC/CWT | APC/CWT | APC/CWT | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinases used | No treatment | Cdk2-cyclinA3 | Cdk2-cyclinA3-Cks2 + Plkl | Cdk2-cyclinA3-Cks2 | Plkl | Cdk2-cyclinA3-Cks2 + Plkl | ||

| Apc1 | LVG S60LQE | 3 | ||||||

| QEVT65IHE | 3(interphase) | |||||||

| PPGS202PRE | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| LFGS233SRV | N.D. | N.D. | 2 | |||||

| LKFS286EQG | 1,3 | |||||||

| QGGT291PQN | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| NVAT297SSS | ||||||||

| VATS298SSL | ||||||||

| ATSS299SLT | ||||||||

| RSLS309KGD | N.D. | 3(interphase) | ||||||

| KGDS313PVT | 3 | |||||||

| SPVT316SPF | 3 | |||||||

| PVTS317PFQ | 3 | |||||||

| HSRS341PSI | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| RSPS3431SN | 1,3 | |||||||

| AALS351RAH | 3 | |||||||

| RAHS355PAL | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| GVHS362FSG | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| HSFS364GVQ | 1,3 | |||||||

| FNIS372SHN | 3 | |||||||

| NISS373HNQ | 1,3 | |||||||

| HNQS377PKR | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| ISHS386PNS | N.D. | 3(interphase) | ||||||

| SPNS389NSN | N.D. | 3 | ||||||

| SNGS394FLA | ||||||||

| WTET4161TN | ||||||||

| VLYT501GVV | ||||||||

| PAPS518LTM | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 3 | ||||

| PSLT520MSN | N.D. | N.D. | 1(interphase),3 | |||||

| LTMS522NTM | N.D. | N.D. | 3(interphase) | |||||

| MSNT524MPR | N.D. | N.D. | 3(interphase) | |||||

| RPST530PLD | 1(interphase),2,3 | |||||||

| DGVS536TPK | ||||||||

| GVST537PKP | 1,3 | |||||||

| KPLS542KLL | N.D. | 2 | ||||||

| LLGS547LDE | 1,3 | |||||||

| VLLS555PVP | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| LRDS563SKL | 3 | |||||||

| RDSS564KLH | N.D. | 2,3 | ||||||

| LHDS569LYN | 1(interphase),3 | |||||||

| EDCT576FQQ | ||||||||

| QLGT582YIH | ||||||||

| LELS600NGS | N.D. | 2 | ||||||

| FEGS686LSP | 3 | |||||||

| GSLS688PVI | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| ARPS699ETG | 3 | |||||||

| PSET701GSD | 3 | |||||||

| ETGS703DDD | 3(interphase) | |||||||

| LCLS731PSE | l,3(interphase),2 | |||||||

| NRFS916FRH | 3 | |||||||

| FRHS920TSV | ||||||||

| RHST921SVS | ||||||||

| HSTS922VSS | ||||||||

| VLSS1001DVP | ||||||||

| KHKS1347PSY | ||||||||

| KSPS1349YQI | ||||||||

| Apc3 | LPNS183CTT | 3 | ||||||

| NSCT185TQV | ||||||||

| SCTT186QVP | ||||||||

| PNHS192LSH | ||||||||

| HSLS194HRQ | ||||||||

| QPET200VLT | ||||||||

| TVLT203ETP | 2 | |||||||

| LTET205PQD | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| PQDT2091El | 1 | |||||||

| NLES219SNS | N.D. | 3(interphase) | ||||||

| LESS220NSK | N.D. | 2,3 | ||||||

| SSNS222KYS | 3 | |||||||

| SKYS225LNT | ||||||||

| SLNT228DSS | ||||||||

| NTDS230SVS | ||||||||

| TSDS231VSY | ||||||||

| SSVS233YID | ||||||||

| YIDS237AVI | ||||||||

| AVIS241PDT | 3 | |||||||

| SPDT244VPL | 1,3 | |||||||

| GTGT251SII | ||||||||

| TGTS252SIL | 3 | |||||||

| SILS255KQV | ||||||||

| KPKT264GRS | N.D. | N.D. | 2 | |||||

| TGRS267LLG | N.D. | |||||||

| AALS276PLT | 3 | |||||||

| SPLT279PSF | 3 | |||||||

| LTPS281FGI | ||||||||

| PLET289PSP | ||||||||

| ETPS291PGD | N.D. | 1 | ||||||

| QNYT302NTP | 1,3 | |||||||

| YTNT304PPV | 1,3 | |||||||

| DVPS312TGA | 1,3 | |||||||

| VPST313GAP | 1,3 | |||||||

| IGQT327GTK | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 3 | ||||

| QTGT329KSV | ||||||||

| GTKS331VFS | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | |||||

| SVFS334QSG | N.D. | N.D. | 2 | |||||

| FSQS336GNS | N.D. | N.D. | 2 | |||||

| REVT343PIL | 1 | |||||||

| LAQT349QSS | ||||||||

| QTQS351SGP | ||||||||

| TQSS352GPQ | ||||||||

| GPQT356STT | ||||||||

| PQTS357TTP | ||||||||

| QTST358TPQ | ||||||||

| TSTT359PQV | ||||||||

| QVLS364PTI | 1 | |||||||

| LSPT3661TS | 1,2 | |||||||

| PTIT368SPP | ||||||||

| TITS369PPN | 1,2,3 | |||||||

| RLFT383SDS | 2 | |||||||

| LFTS384DSS | 2 | |||||||

| TSDS386STT | 2 | |||||||

| SDSS387TTK | 2 | |||||||

| DSST388TKE | ||||||||

| SSTT389KEN | 2 | |||||||

| GGIT419QPN | ||||||||

| INDS426LEI | 1,2 | |||||||

| LEIT430KLD | 1 | |||||||

| KLDS434S11 | 1 | |||||||

| LDSS435llS | 1,2 | |||||||

| SIIS438EGK | 2 | |||||||

| GKIS443TIT | ||||||||

| KIST4441TP | 2,3 | |||||||

| STIT446PQI | 1,2 | |||||||

| MNFS761WAM | ||||||||

| IMGT800DES | ||||||||

| TDES803QES | ||||||||

| SQES806SMT | ||||||||

| QESS807MTD | ||||||||

| SSMT809DAD | ||||||||

| ADDT814QLH | ||||||||

| AAES821DEF |

The pink shading shows the presence of phosphorylation sites and the white indicates its absence.

Following references were used for comparison:

The phosphorylation sites within the Apel Al segment are highlighted in light purple shadows. Phosphorylation sites of the remaining APC/C subunits are summarized in Extended Data Table 3.

Extended Data Table 3. Summary of phosphorylation sites of in vitro phosphorylated APC/C subunits (excluding Apc1 and Apc3) identified by mass spectrometry.

| Protein | Phospho-sites | APC/CWT | APC/CWT | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinases used | No treatment | Cdk2-cyclinA3-Cks2 + Plkl | ||

| Apc2 | ELDS205RYA | |||

| LLQS218PLC | 2 | |||

| RPAS314PEA | 1,2,3 | |||

| SLETS466GQD | ||||

| GQDS470EDD | 3 | |||

| EDDS374GEP | ||||

| HQFS532FSP | 2 | |||

| FSFS534PER | 1,2,3 | |||

| LIDS732DDE | 3(interphase) | |||

| DDES736DSG | 3(interphase) | |||

| ESDS738GMA | 3(interphase) | |||

| GMAS742QAD | ||||

| Apc4 | ARVT199GIA | |||

| KGKY469FNV | 1 | |||

| DLVS488PPN | ||||

| LDES757SDE | ||||

| DESS758DEE | ||||

| EVLS777ESE | 2,3 | |||

| LSES779EAE | 1 | |||

| Apc5 | PMMTl5NGV | 2 | ||

| HKTS130VVG | ||||

| MELT178SRD | 3 | |||

| ELTS179RDE | 3 | |||

| LDVS195VRE | 1,2 | |||

| QQAS221LLK | 2,3 | |||

| NDET228KAL | ||||

| KALT232PAS | 2 | |||

| VASS674AAS | 2 | |||

| Apc6 | KDES112GFK | 1,3 | ||

| NllS559PPW | 1,2,3 | |||

| EKQT573AEE | ||||

| AEET577GLT | ||||

| TGLT580PLE | 1,2,3 | |||

| PLET584SRK | ||||

| LETS585RKT | 2,3 | |||

| TPDS592RPS | N.D. | |||

| SRPS595LEE | N.D. | 1 | ||

| LEET599FEI | 1 | |||

| MNES607DMM | ||||

| LETS614MSD | ||||

| Apc7 | VRPS119TGN | 1 | ||

| RPST120GNS | 1 | |||

| TGNS123AST | 1,3 | |||

| NSAS125TPQ | 1,3 | |||

| SAST126PQS | 2,3 | |||

| MEGS573GEE | ||||

| LEGS582DSE | ||||

| GSDS584EAA | ||||

| Apc8 | QGET562PTT | 1,2 | ||

| TPTT565EVP | 1,2 | |||

| ANNT582PTR | 1,2,3 | |||

| NTPT584RRV | 1 | |||

| RRVS588PLN | 2,3 | |||

| LNLS593SVT | 3 | |||

| SSVT596P | 2,3 | |||

| Apc12 | VGGS42DGE | |||

| IGLS5lSDP | ||||

| GLSS52DPK | ||||

| DPKS56REQ | N.D. | |||

| NRSS78QFG | ||||

| Apc15 | DEDS76EED | |||

| EEDS80EDD | ||||

| YNES98PDD | ||||

| Apc16 | SSSS8SAG | N.D. | ||

| VSGS16SVT | N.D. | |||

| FSVS26DLA | N.D. |

The pink shading shows the presence of phosphorylation sites and the white indicates its absence.

Following references were used for comparison:

Phosphorylation sites of the Apel and Apc3 subunits are summarized in Extended Data Table 2.

Supplementary Material

Video 1. Structure of phosphorylated APC/CCdc20.Hsl1 and unphosphorylated apo APC/C. The chronology follows Figures 1 to 3. Overall structure of the APC/CCdc20-Hsl1 complex. Detailed views showing interactions between Cdc20 and the APC/C (C box, KILR motif and IR tail) and comparison with Cdh1. The apo unphosphorylated APC/C is shown revealing the Apc1 auto-inhibitory (AI) segment that overlaps with the C box motif of Cdc20. Red spheres on the Apc1 AI segment indicate mitotic phosphorylation sites.

Supplementary Figure 1. This file contains source data gels.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology and a Cancer Research UK grant to D.B. PhD funding for S.Z. was from the Gates Cambridge Scholarship and Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds. C.A. is an EMBO Fellow. We are grateful to members of the Barford group for discussion; S. Chen, C. Savva and G. McMullan for EM facilities; J. Grimmet and T. Darling for computing; K. Zhang for advice on data processing and G. Murshudov for help with REFMAC.

Footnotes

Author contributions. S.Z. cloned the substrates and Cdh1 mutant, purified proteins and performed biochemical analysis. S.Z. and L.C. prepared grids, collected and analysed EM data and determined the three dimensional reconstructions. S.Z. fitted coordinates, built models and made figures with help of L.C. C.A. cloned kinases and Cdc20 and established in vitro phosphorylation of the APC/C. Z.Z. and J.Y. cloned the APC/C mutants and the chimeric proteins and prepared viruses. S.M. and M.S. performed mass spectrometry. D.B. directed the project and designed experiments with S.Z. S.Z. and D.B. wrote the manuscript with input from authors.

Author information. EM maps are deposited with EM-DB with accession codes: 3385 (APC/CCdc20-Hsl1), 3386 (apo unphosphorylated APC/C), 3387 (apo phosphorylated APC/C), 3388 (combined apo phosphorylated APC/C), 3389 (APC/CΔApc1-300s) and 3390 (APC/CΔApc1-300s-TAME). Protein coordinates are deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes: 5G04 (APC/CCdc20-Hsl1) and 5G05 (apo phosphorylated APC/C).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Pines J. Cubism and the cell cycle: the many faces of the APC/C. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2011;12:427–438. doi: 10.1038/nrm3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Primorac I, Musacchio A. Panta rhei: the APC/C at steady state. The Journal of cell biology. 2013;201:177–189. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang L, Barford D. Insights into the anaphase-promoting complex: a molecular machine that regulates mitosis. Current opinion in structural biology. 2014;29:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kimata Y, Baxter JE, Fry AM, Yamano H. A role for the Fizzy/Cdc20 family of proteins in activation of the APC/C distinct from substrate recruitment. Molecular cell. 2008;32:576–583. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Voorhis VA, Morgan DO. Activation of the APC/C ubiquitin ligase by enhanced E2 efficiency. Current biology : CB. 2014;24:1556–1562. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang L, Zhang Z, Yang J, McLaughlin SH, Barford D. Molecular architecture and mechanism of the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature. 2014;513:388–393. doi: 10.1038/nature13543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lahav-Baratz S, Sudakin V, Ruderman JV, Hershko A. Reversible phosphorylation controls the activity of cyclosome-associated cyclin-ubiquitin ligase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:9303–9307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shteinberg M, Protopopov Y, Listovsky T, Brandeis M, Hershko A. Phosphorylation of the cyclosome is required for its stimulation by Fizzy/cdc20. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:193–198. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer ER, Scheuringer N, Podtelejnikov AV, Mann M, Peters JM. Mitotic regulation of the APC activator proteins CDC20 and CDH1. Molecular biology of the cell. 2000;11:1555–1569. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudner AD, Murray AW. Phosphorylation by Cdc28 activates the Cdc20-dependent activity of the anaphase-promoting complex. The Journal of cell biology. 2000;149:1377–1390. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golan A, Yudkovsky Y, Hershko A. The cyclin-ubiquitin ligase activity of cyclosome/APC is jointly activated by protein kinases Cdk1-cyclin B and Plk. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:15552–15557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraft C, et al. Mitotic regulation of the human anaphase-promoting complex by phosphorylation. The EMBO journal. 2003;22:6598–6609. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zachariae W, Schwab M, Nasmyth K, Seufert W. Control of cyclin ubiquitination by CDK-regulated binding of Hct1 to the anaphase promoting complex. Science. 1998;282:1721–1724. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaspersen SL, Charles JF, Morgan DO. Inhibitory phosphorylation of the APC regulator Hct1 is controlled by the kinase Cdc28 and the phosphatase Cdc14. Current biology : CB. 1999;9:227–236. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwab M, Neutzner M, Mocker D, Seufert W. Yeast Hct1 recognizes the mitotic cyclin Clb2 and other substrates of the ubiquitin ligase APC. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:5165–5175. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Passmore LA, et al. Doc1 mediates the activity of the anaphase-promoting complex by contributing to substrate recognition. The EMBO journal. 2003;22:786–796. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vodermaier HC, Gieffers C, Maurer-Stroh S, Eisenhaber F, Peters JM. TPR subunits of the anaphase-promoting complex mediate binding to the activator protein CDH1. Current biology : CB. 2003;13:1459–1468. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patra D, Dunphy WG. Xe-p9, a Xenopus Suc1/Cks protein, is essential for the Cdc2-dependent phosphorylation of the anaphase- promoting complex at mitosis. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2549–2559. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shteinberg M, Hershko A. Role of Suc1 in the activation of the cyclosome by protein kinase Cdk1/cyclin B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:12–18. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herzog F, Mechtler K, Peters JM. Identification of cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation sites on the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome by mass spectrometry. Methods Enzymol. 2005;398:231–245. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)98019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steen JA, et al. Different phosphorylation states of the anaphase promoting complex in response to antimitotic drugs: a quantitative proteomic analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:6069–6074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709807104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegemann B, et al. Systematic phosphorylation analysis of human mitotic protein complexes. Science signaling. 2011;4:rs12. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang L, Zhang Z, Yang J, McLaughlin SH, Barford D. Atomic structure of the APC/C and its mechanism of protein ubiquitination. Nature. 2015;522:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature14471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzog F, et al. Structure of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome interacting with a mitotic checkpoint complex. Science. 2009;323:1477–1481. doi: 10.1126/science.1163300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izawa D, Pines J. Mad2 and the APC/C compete for the same site on Cdc20 to ensure proper chromosome segregation. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;199:27–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201205170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi M, et al. Structure of an APC3-APC16 Complex: Insights into Assembly of the Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome. Journal of molecular biology. 2015;427:1748–1764. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Zon W, et al. The APC/C recruits cyclin B1-Cdk1-Cks in prometaphase before D box recognition to control mitotic exit. The Journal of cell biology. 2010;190:587–602. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200912084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sudakin V, Shteinberg M, Ganoth D, Hershko J, Hershko A. Binding of activated cyclosome to p13(suc1). Use for affinity purification. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:18051–18059. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.18051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng X, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex induces a spindle checkpoint-dependent mitotic arrest in the absence of spindle damage. Cancer cell. 2010;18:382–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Z, et al. Recombinant expression, reconstitution and structure of human anaphase-promoting complex (APC/C) The Biochemical journal. 2013;449:365–371. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Analytical chemistry. 2002;74:5383–5392. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bai XC, Fernandez IS, McMullan G, Scheres SH. Ribosome structures to near-atomic resolution from thirty thousand cryo-EM particles. eLife. 2013;2:e00461. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li X, et al. Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nature methods. 2013;10:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mindell JA, Grigorieff N. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. Journal of structural biology. 2003;142:334–347. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang K. Gctf: real-time CTF determination and correction. J Struct Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scheres SH. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. Journal of structural biology. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scheres SH. Semi-automated selection of cryo-EM particles in RELION-1.3. J Struct Biol. 2015;189:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheres SH. Beam-induced motion correction for sub-megadalton cryo-EM particles. eLife. 2014;3:e03665. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian W, et al. Structural analysis of human Cdc20 supports multisite degron recognition by APC/C. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:18419–18424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213438109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Z, et al. UCSF Chimera, MODELLER, and IMP: an integrated modeling system. Journal of structural biology. 2012;179:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murshudov GN, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fernandez IS, Bai XC, Murshudov G, Scheres SH, Ramakrishnan V. Initiation of translation by cricket paralysis virus IRES requires its translocation in the ribosome. Cell. 2014;157:823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DM, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview Version 2--a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.