Abstract

We examined concern for others in 22-month-old toddlers with an older sibling with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and low risk typically-developing toddlers with older siblings. Responses to a crying infant and an adult social partner who pretended to hurt her finger were coded. Children with a later diagnosis of ASD showed limited empathic concern in either context compared to low risk toddlers. High risk toddlers without a later diagnosis fell between the ASD and low risk groups. During the crying baby probe the low risk and high risk toddlers without a diagnosis engaged their parent more often than the toddlers with ASD. Low levels of empathic concern and engagement with parents may signal emerging ASD in toddlerhood.

Keywords: High-risk siblings, empathic concern, responses to distress, engagement with parents, Autism spectrum disorder

Empathy is defined as a feeling of concern when witnessing another person’s distress and the desire to intervene to alleviate that distress (Hoffman 1981; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1992). In typically-developing infants, empathy is thought to derive from a fundamental, biologically-based social motivation to affiliate with others (Davidov et al. 2013; Hobson 2007). Over the first two years of life empathy develops in tandem with other important aspects of social engagement and understanding, including social referencing, joint attention, awareness of the perspectives and intentions of social partners, and prosocial behavior (e.g., Brownell and Kopp 2007; Hobson 2007; Moore 2007). Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), however, show only limited social engagement and awareness of other people’s feelings, and they are also less likely to respond to another person’s distress than typically-developing children (Hobson 2007; Sigman et al. 1992). Delays or deficits in emerging empathy, therefore, may be one early sign of ASD. In the current study we assess social and emotional reactions to the distress of a crying infant and the distress of a social partner in 22-month-old toddlers at high and low genetic risk for ASD.

Empathy Development

Empathy has its roots in both neurobiological processes and early experiences with caregivers (Hoffman 2007; Zahn-Waxler et al.1992). In the second year of life emerging empathy is closely tied to the development of self-awareness and self-other differentiation, as toddlers express both self-distress and other-directed concern when witnessing another person’s pain and negative affect (Zahn-Waxler et al.1992). While self-distress appears to be a more basic response to another’s negative affect, the ability to express concern directed to another person seems to require some degree of perspective-taking ability and awareness of inner states, including the ability to read facial and vocal cues of emotion and understand something about what the other person is feeling (Brownell and Kopp 2007; Hoffman 2007; Moore 2007; Nichols et al. 2009). Developmental studies of typically-developing infants and toddlers indicate that empathic concern is evident in rudimentary form prior to 12 months and consolidates over the second and third years of life (Knafo et al. 2008; Nichols et al. 2009; Roth-Hania et al 2011; Zahn-Waxler et al.1992) with attention to another’s distress and expressions of self-distress increasing between 12 and 36 months (Hutman et al.2010; Knafo et al. 2008; Nichols et al. 2009, 2015).

Most experimental studies of emerging empathy in toddlers have relied on simulated distress situations during which the parent or an examiner feigns pain or distress (Kiang et al. 2004; Knafo et al. 2008; Zahn-Waxler et al.1992). Although it seems logical to predict that parental distress will elicit a stronger response than the distress of a less familiar adult, the limited literature is inconsistent on this point (Young et al., 1999; Spinrad and Stifter, 2006).

A few studies have assessed empathic concern for a crying infant or toddler, on the assumption that young children may express stronger reactions when witnessing the distress of someone more like themselves. In two studies using either tape-recordings or videos of a crying child (Gill and Calkins 2003; Roth-Hania et al. 2011), toddlers evidenced only limited reactions. Spinrad and Stifter (2006), however, used a more naturalistic situation; the examiner carried a realistic-looking doll swaddled in a blanket. The 18-month-old typically-developing toddlers showed more concern for the crying “baby” than for the examiner or their mother, suggesting that another child’s distress may be especially salient to young children. Nichols et al. (2009; 2015) also compared the responses of toddlers to simulated maternal distress and to a crying “baby,” a realistic doll left alone in the room with the child. Children showed more self-distress and empathic concern to the crying baby than to their mothers, with concern for the baby increasing between 18 and 24 months. Moreover, children with a higher level of social understanding showed more concern for the crying baby, even with age controlled, underscoring the importance of social cognitive development for emerging empathy.

Empathy and ASD

In contrast to typically-developing children, children with ASD are less socially connected to others and social impairments are hallmarks of the disorder (American Psychiatric Association 2000; Dawson 2008). Not surprisingly then, young children with ASD evidence limited responsiveness to the affective displays of social partners. Sigman et al. (1992) compared the responses of preschool children with ASD, developmental delays, or typical development to displays of pain and fear by their mothers and a female experimenter. Children with ASD showed less concern for and awareness of either adult’s negative affective state than comparison children. Likewise, Charman et al. (1997) found that 20-month old children with autism symptoms were less concerned when the experimenter “hurt” her hand with a toy hammer. This lack of responsiveness to the distress of others illustrates the lower level of social awareness and social motivation that characterizes children with autism (Dawson 2008).

To understand the early emergence of ASD, including early signs of low social engagement and social interest, recent research has focused on infants who are at genetic risk for ASD because they have an older sibling with the disorder. One large-scale study found that nearly 20% of high risk (HR) infant siblings received a diagnosis of ASD by 36 months (Ozonoff et al. 2011). The prospective study of HR siblings can track development prior to a diagnosis and identify early precursors of symptoms. Studies that examine aspects of social development that are well characterized in typically-developing toddlers and map onto known social deficits in children with ASD may provide new information about the early developmental course of social difficulties in children who later receive a diagnosis of ASD. HR toddlers who do not receive a diagnosis of ASD are also of interest, as some of these children may show subtle subclinical difficulties including atypical social behavior, reflecting the broader autism phenotype (e.g., Brian et al. 2008; Ozonoff et al. 2014; Yirmiya and Charman 2010).

Two recent studies have reported on empathic responding in toddlers at risk for ASD. Hutman et al. (2010) studied the responses of high and low risk children at 12, 18, 24, and 36 months to the distress of the examiner who pretended to hit her finger with a toy mallet. Responses were rated on scales assessing attention to the examiner’s distress and affective state changes indicative of worry or concern. Significant differences were obtained between the 14 children who received a diagnosis of ASD at 36 months and the low risk (n=52) and high risk children without a diagnosis (n=72) on ratings of both attention and affect; group differences became more pronounced across age. The HR children without a diagnosis did not differ from the low risk (LR) children. McDonald and Messinger (2012) also reported that HR toddlers with an ASD diagnosis (n= 13) were less responsive to their parent’s distress at 24 and 36 months than HR toddlers without a diagnosis (n=25). Thus, these two studies suggest that by late in the second year of life, HR toddlers who receive a diagnosis of ASD are less responsive to distress expressed by parents or an unfamiliar examiner than toddlers who do not evidence symptoms of ASD later in development.

The Current Study

In the current study we examine responses of HR and LR toddlers to another’s distress using two different empathy probes, a crying infant and an adult social partner. Toddlers were studied at 22 months and then assessed for ASD in the third year of life. LR toddlers were compared to HR toddlers with and without a later ASD diagnosis. The first probe is the standard simulation of pain by the examiner with whom the child has been playing (Hutman et al. 2010; Spinrad and Stifter 2006; Zahn-Waxler et al. 1992), thereby allowing for more control of the empathy probe than relying on a parent’s simulation. The second more novel measure assesses children’s responses to a crying “baby” based on recent findings with typically-developing toddlers (Nichols et al. 2009; 2015; Spinrad and Stifter 2006). This is the first study of which we are aware to examine responses of HR toddlers to an infant’s distress, a highly salient event to typically-developing toddlers. Thus, the current study adds to the literature on emerging empathy in HR toddlers and on early other-oriented emotional indicators of autism risk by comparing HR toddlers with and without a later ASD diagnosis to LR toddlers across two empathy probes, both of which have been demonstrated to reliably elicit empathic responses in typically-developing toddlers.

Following Zahn-Waxler et al. (1992), we rated self-distress and other-directed empathic concern separately. In addition, we coded behavioral indices of simple interest in the crying baby, as well as efforts to engage the parent while the baby was crying. We predicted that children with a diagnosis of ASD would be less engaged in and concerned about either the crying infant or the examiner’s hurt finger than LR toddlers, as reflected in lower levels of both empathic concern and self-distress. We also predicted that children with ASD would exhibit fewer behaviors indicative of interest in the crying baby and would show lower rates of engagement with their parent during the crying infant episode. Although we also expected the HR toddlers without a diagnosis to fall between the toddlers with ASD and the LR toddlers, given the limited data on this question, it was unclear whether they would differ from either or both of these groups.

Parental reports of children’s self-understanding were also obtained. We expected that HR toddlers would differ from LR toddlers on self-understanding and that individual differences in self-understanding would be related to toddlers’ concern for the distressed other, as some degree of self-awareness and self-other differentiation would appear to be a correlate of empathic concern. Finally, we expected that both empathic concern across these two empathy probes and ratings of self-understanding would predict the severity of autism symptoms within the high risk group.

Method

Participants

Toddlers and their parents are participants in a larger prospective study of children at risk for ASD. The sample includes infants with an older sibling with ASD and comparison infants with a typically-developing older sibling. The 69 children included in this report were seen at 22 months (M = 22.72, SD = .76) for a play-based assessment of social behavior that included the empathy probes described below. Most were seen again at 36 months for a follow-up diagnostic assessment (details below). Groups did not differ in age at the 22-month assessment (See Table 1). Parents signed informed consents prior to participation; the research protocol was approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Table1.

Sample characteristics

| ASD (n=12) |

HR-noASD (n=27) |

LR (n=30) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, % male | 83.3% | 63% | 50% |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian | 91.7% | 85.2% | 100% |

| Education | |||

| High school/some college | 33.3% | 48.1% | 10% |

| College degree | 33.3% | 14.8% | 36.7% |

| Graduate degree | 33.3% | 37% | 53.3% |

| Age at Age at 22 month assessment, M (SD) | 22.75 (0.69) | 22.61 (0.70) | 22.80 (0.84) |

| Mullen Language composite , M (SD) | 28.40 (6.00)a | 52.19 (9.63)b | 56.50 (8.80)b |

| Mullen Nonverbal composite, M (SD) | 42.17 (6.94)a | 48.40 (7.81)a | 56.13 (9.04)b |

| ADO ADOS severity score, M (SD) | 5.27 (1.27)a | 1.70 (1.07)b | 1.53 (0.97)b |

Note: 6 children are missing Mullen scores (3 ASD, 1 HR-noASD, 2 LR); 1 ASD child is missing an ADOS severity score. See text for explanations.

Means with different superscripts differ at p <.05 or better; see text.

ASD = toddlers with a later ASD diagnosis

HR-noASD = high risk toddlers without a later ASD diagnosis

LR = low risk toddlers

HR toddlers (n= 38, 26 males) were recruited between 6 and 16 months for a study of cognitive and social development, through the Autism Center at (removed for blind review), with the exception of one HR child who joined the study at 22 months. To be eligible for inclusion in the HR group, children had to be born full-term after an uncomplicated pregnancy and delivery, and have an older sibling diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder according to research criteria. The older sibling’s diagnosis was confirmed by research reliable staff at the Autism Center who administered the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000) under the supervision of a licensed psychologist, prior to the younger sibling’s enrollment in the study. Infants whose older siblings had known genetic or other anomalies, such as Fragile X, were excluded. Two HR toddlers were half-siblings of the child with ASD.

LR control participants (n=31, 16 males) were recruited from the local obstetrics hospital, community groups, pediatric offices, and word of mouth. Full-term healthy toddlers with a typically-developing older sibling and negative family history of ASD in first and second degree relatives comprised the LR group. Parents of LR children completed the Social Communication Questionnaire (Rutter et al., 2003) on the older sibling prior to study enrollment; all scored well below the ASD cut-off of 15.

Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1, including comparisons between the LR toddlers, the HR toddlers without a diagnosis (HR-noASD), and the toddlers with a later ASD diagnosis (see below). Participating children are predominantly Caucasian and non-Hispanic (93%) and all but two are from two-parent families. Parent education was scored according to the Hollingshead Scale. Although the majority of parents in both groups had at least a college degree (71%), the LR parents were more highly educated than the parents of the HR toddlers.

Procedure

Toddlers’ Responses to Another’s Distress

As part of a longer assessment of social engagement in toddlerhood, two empathy probes were administered. The first focused on the child’s responses to the distress of a crying infant (“crying baby”) and the second involved the feigned distress of the examiner with whom the child had been playing (“hurt finger”). Parents remained with their children for the entire visit. During the empathy probes parents were seated in a corner of the room within view of the child. Prior to the start of the session, parents were told about the probes and asked not to prompt their child or make suggestions during the episodes, but to respond neutrally to their child’s questions.

Crying Baby

About half-way through the play session, while the child was engaged with an interesting toy, the examiner entered the room with a realistic looking baby doll swaddled in a blanket and secured in an infant seat on a rolling cart, above the toddler’s reach and eye level (Nichols et al., 2009; 2015). A tape-recorder was hidden beneath the blanket and a baby bottle, second blanket, and small stuffed animal were on the cart’s bottom shelf. The examiner explained that she needed to leave her baby there to take a nap. Twenty seconds after the examiner left the room, the recording of an actual baby crying played for 20 seconds. The crying subsided for 20 seconds and then resumed for another 20 seconds. After the second cry, the examiner returned, removed the cart and doll, and left the child and parent together for the next activity. The entire episode lasted 80 seconds, with the first 20 seconds prior to the first cry not coded. Six toddlers (4 HR-noASD, 2 LR) are missing data on the crying baby probe because of equipment problems or protocol errors.

Hurt Finger

The second empathy probe occurred toward the end of the roughly 45-minute play visit. The examiner, with whom the child had previously been playing, returned with questionnaires for the parent to complete and a toy pounding bench with colored blocks and a mallet. As the examiner demonstrated the toy by pounding the blocks, she hit her finger with the mallet, and said “ouch, I hurt my finger with the hammer.” She then rubbed her finger with a pained expression on her face, repeating “ouch, it hurts” while continuing to rub her finger for about 20 seconds. Before leaving the room, the examiner said: “my finger feels better now.”

Coding and Reliability

Toddlers’ responses to the two distress situations were coded from videotapes by trained coders who were blind to group designation (HR or LR) and diagnostic outcome. Both probes were rated on 4-point (0-3) scales of empathic concern and self-distress, derived from the work of Zahn-Waxler et al. (1992). Ratings of 0 were given when the child showed no concern; ratings of 1 indicated slight concern, if the child showed a brief sobering of expression that lasted at least 3 seconds; a rating of 2 indicated moderate concern including sobering or a concerned/worried facial expression lasting about 8 seconds; ratings of 3 reflected substantial concern that included sustained sadness, a sympathetic facial expression, and looks to the baby (or to the examiner). Self-distress was also rated on a 0-3 scale, with negative arousal and fussing, seeking comfort from the parent, and self-comforting behavior (e.g., looking away, fiddling with hair or clothing, sucking thumb) contributing to higher ratings.

During the crying baby episode, specific behaviors were also coded as present or absent during each of three 20-second intervals: baby’s first cry; the interval between cries; and the baby’s second cry. Behaviors that reflected interest in the baby while also engaging the parent were summed over the three intervals into an “engage parent” variable. This composite included three social communicative behaviors: referencing the parent (looking between parent and baby), pointing to the baby, and talking to the parent about the baby (e.g., “she’s crying”) (possible range 0-9). A second “interest” composite that did not involve the parent included two behaviors: looking at and/or approaching the crying baby (possible range 0-6).

Inter-observer reliability on the composited behavioral codes making up the “engage parent” and “interest” measures in response to the crying baby was calculated on 30% of the video records. The average intraclass correlations for the specific behaviors making up the engage parent composite ranged from .81 to .97 (M = .92). The average intraclass correlations for the two behaviors making up the interest composite also ranged from .81 to .97 (M = .93). All video records were rated for empathic concern and self-distress by two independent coders. The average intraclass correlations were .80 and .85 for empathic concern and .70 and .84 for self-distress during the crying baby and hurt finger probes, respectively. In addition, kappas assessing exact agreement on ratings of 0 vs 1 vs >1 were calculated: empathic concern during crying baby (.702) and hurt finger (.737); self-distress during crying baby (.428) and hurt finger (.666). According to Landis and Koch (1977), kappas between .41 and .60 are considered moderate and those between .61 and .80 are considered substantial. Disagreements were reviewed and a consensus reached on the ratings prior to data analysis.

Toddlers’ Self-Understanding

During the session, parents completed the UCLA Self-Understanding Questionnaire (Stipek et al., 1990), a 24-item scale tapping children’s self-recognition and self-awareness. For example, items assess mirror self-recognition, use of the word “mine”, and awareness of being a girl or boy. Parents rated each item on a 3-point scale from 0=definitely not, 1= sometimes, and 2 = definitely yes. In the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was .89.

Developmental and Autism Assessments

Mullen Scales of Early Learning

The Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; Mullen, 1995), a standardized measure of cognitive development, was administered at 24 months. T-scores on the Receptive Language and Expressive Language were averaged to provide a language development score at 24 months. Scores on Visual Reception and Fine Motor were averaged to provide a measure of non-verbal skills. Six children are missing Mullen scores at 24 months (2 LR, 1 HR-noASD, 3 ASD) because of missed appointments, scheduling difficulties, or the child’s refusal.

Evaluations for Autism

Both HR and LR toddlers were evaluated for an ASD diagnosis at follow-up, using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS, Lord et al., 2000). The ADOS, a semi-structured observational assessment, includes play-based activities that are meant to elicit reciprocal social interaction, communication, and stereotyped behaviors and provides scoring rules for a diagnosis of ASD. All children received either Module 1 or 2. Evaluations were conducted by a research-reliable tester from the Autism Center under the supervision of a licensed clinical psychologist with extensive experience assessing children with ASD; no one involved in the diagnostic assessments conducted the laboratory visits. Diagnostic decisions were based on the 36 month assessment for most of the HR children (n=30); two HR children who missed their 36 month visits were seen at 48 months. Five HR toddlers were assessed at 24 months. Although 36 month outcome data are preferred, data suggest that when diagnoses are clear at 24 months, they are likely to be stable (Chawarska et al., 2009). One HR child with a diagnosis was seen at a local developmental clinic specializing in autism, but the ADOS score was not available. All LR children were assessed at 36 months.

Children were classified as ASD if they met cut-off scores on the ADOS (Lord et al., 2000) and also met DSM-IV criteria for an autism spectrum disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), as determined by interview and observation. Parents of children with elevated ADOS scores and/or serious clinical concerns were interviewed using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R, Lord et al., 1994) to provide further information. Final diagnoses, therefore, were based on a combination of structured diagnostic measures, DSM-IV criteria, and clinical judgment and made by a licensed clinical psychologist; 11 HR toddlers (9 boys) received a diagnosis of ASD. One LR boy with an earlier language delay and some social concerns received a diagnosis of ASD at 48 months and is included in the ASD group in the analyses.

In addition to a diagnosis, ADOS scores were converted to severity scores using the algorithm provided by Gotham et al. (2009) to allow for comparability across age; severity scores are summarized in Table 1. As expected, there was a main effect of group status, F(2, 67) = 49.31, p <.001, η2 =.31. The children with a diagnosis (ASD) had substantially higher severity scores than the LR children (p <.001, d = −3.53) and the HR-noASD children (p <.001, d = −3.18). LR and HR-noASD children did not differ from one another.

Data Analysis Plan

Group differences were analyzed with ANOVA’s and confirmed with non-parametric tests, given the unequal sample sizes across the three groups (LR, HR-noASD, ASD). Because the results were essentially the same, only the results from the ANOVAs are reported (results of the non-parametric tests are available from the first author upon request). Effect sizes are reported using eta squared for main effects and Cohen’s d for paired comparisons. Analyses were also conducted controlling for language scores on the Mullen. Next, correlations between the empathy measures and self-understanding are reported. Finally, correlations were calculated between ADOS severity scores and the measures of empathy and self-understanding within the HR group as a whole, including the one LR child with an ASD diagnosis.

Results

Preliminary analyses were conducted to test for gender differences in responses to the empathy probes, including only the children with no diagnosis, as gender and ASD were confounded (10 of 12 children with ASD were boys). No gender differences were found, so gender is not considered further. Correlations between parent education and empathy measures were also not significant, so parent education is not controlled in the analyses.

There were significant group differences on the 24-month Mullen Language composite, F (2, 62) = 35.05, p <.001, η2 =.54 (see Table 1). Children with ASD had significantly lower scores than both the LR (p <.001, d = 3.42) and HR-noASD (p <.001, d = 2.68) children who did not differ from one another. There were also significant group differences on the Mullen Non-Verbal composite, F (2, 62) = 11.76, p <.001, η2 =.28. The LR children received higher scores than the HR-noASD children (p =.004, d =.92) and the children with ASD (p <.001, d = 1.67). The difference between the HR-noASD and the ASD groups on non-verbal ability fell short of statistical significance (p =.094, d = .84).

Group Differences

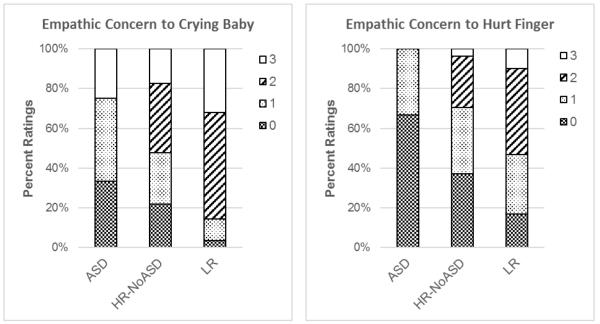

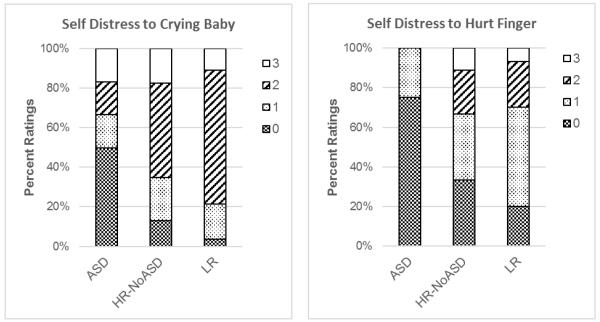

One-way ANOVAs were conducted to test for differences between the LR, HR-noASD, and ASD groups. Main effects were followed up with post hoc tests using the Games-Howell correction given the unequal group sizes. Both p values and effect sizes are reported. Data are presented separately for the two empathy probes, and for self-understanding. Analyses of the empathy measures are also reported controlling for the Mullen Language composite. Means and standard deviations for the empathy measures are summarized in Table 2. The distribution of empathic concern and self-distress ratings by group and empathy probe (crying baby, hurt finger) are depicted in Figures 1 and 2 for descriptive purposes.

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of empathy and self-understanding measures

| ASD (n=12) |

HR-noASD (n=27) |

LR (n=30) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Crying Baby | |||

| Empathic Concern1 | 1.17 (1.19)a | 1.48 (1.04)a | 2.14 (0.76)b |

| Self-Distress1 | 1.00 (1.21) | 1.70 (0.93) | 1.86 (0.65) |

| Engage parent2 | 0.92 (1.73)a | 2.60 (2.12)b | 4.68 (2.40)c |

| Interest3 | 3.08 (2.11) | 2.83 (1.72) | 3.50 (1.00) |

| Hurt Finger | |||

| Empathic Concern1 | 0.33 (0.49)a | 0.96 (0.90)b | 1.50 (0.90)b |

| Self-Distress1 | 0.25 (0.45)a | 1.11 (1.01)b | 1.17 (0.83)b |

| UCLA Self-Understanding Questionnaire | 13.25 (7.62)a | 23.74 (9.30)b | 29.73 (7.43)c |

Note: Data on four HR-noASD and two LR toddlers are missing for crying baby

HR-ASD = high risk toddlers with a later ASD diagnosis

HR-noASD = high risk toddlers with a later ASD diagnosis

LR = low risk toddlers

Means with different superscripts differ at p <.05 or better; see text.

Rating of behavior (0-3)

Engage parent = sum of pointing, referencing, and talking about the crying baby across the three 20-second intervals (possible range 0-9)

Interest = sum of approach and look at the crying baby across the three 20-second intervals (possible range 0-6)

Figure 1.

Distribution of empathic concern ratings by group and context. ASD = toddlers with a later ASD diagnosis. HR-noASD = high risk toddlers with no ASD diagnosis. LR = low risk toddlers.

Figure 2.

Distribution of self-distress ratings by group and context. ASD = toddlers with a later ASD diagnosis. HR-noASD = high risk toddlers with no ASD diagnosis. LR = low risk toddlers.

Crying Baby

There was a main effect of group for three of the four measures derived from the observations of the crying baby (see Table 2): empathic concern, F (2, 62) = 5.483, p < .006, η2 =.15; self-distress, F (2, 62) = 4.086, p < .022, η2 =.12; and engage parent, F (2, 62) = 13.777, p < .001, η2 =.31. Groups did not differ in interest, F (2, 62) = 1.245, ns, η2 =.04. LR toddlers showed more empathic concern than either the HR-noASD toddlers (p =.037, d = .92) or the toddlers with ASD (p= .048, d = 1.69), but the HR-noASD toddlers and toddlers with ASD did not differ from one another. The difference between the LR toddlers and the toddlers with ASD on the rating of self-distress fell short of significance in follow-up tests (p =.086, d = 1.01). Each group differed from the other two on the engage parent composite: LR vs. HR-noASD, p =.005, d = .92; LR vs. ASD, p <.001, d = 1.69; HR-noASD vs. ASD, p =.048, d = .83. In summary, the toddlers with an ASD diagnosis were not less interested in the crying baby, but they differed from the LR toddlers on measures of both empathic concern and engage parent. The HR-noASD toddlers engaged the parent during the crying baby probe more often than the children with ASD, but less often than the LR control group and they showed lower levels of empathic concern than the LR toddlers. Effect sizes for the paired comparisons were generally large.

When these data were analyzed controlling for the Mullen Early Language Composite, the group difference in empathic concern fell short of significance, F (2, 53) = 2.832, p = .068, partial η2 =.097. The group difference in engage parent remained significant F (2, 53) = 5.028, p =.01, partial η2 =.159. Follow-up pairwise comparisons indicated that the differences between the LR toddlers and both the HR-noASD (p=.004) and ASD (p=.04) groups remained significant; thus, group differences in language development did not fully account for the lower level of engagement with parent during the crying baby probe by the HR toddlers.

Hurt Finger

The pattern of responses to the examiner’s distress in the hurt finger episode was somewhat different from the pattern described above. The group main effect for ratings of both empathic concern, F (2, 68) = 8.087, p = .001, η2 =.20, and self-distress, F (2, 68) = 5.313, p < .007, η2 =.14, was significant (see Table 2). Both the LR and HR-noASD toddlers showed more empathic concern for the examiner and more self-distress than the toddlers with ASD (empathic concern: LR vs. ASD, p<.001, d = 1.40; HR-noASD vs. ASD, p = .021, d = .79; self-distress: LR vs. ASD, p<.001, d = 1.22; HR-noASD vs. ASD, p=.002, d = .97). Thus, both LR and HR toddlers without an ASD diagnosis were more concerned and more distressed when the examiner hurt her finger than were toddlers with a later ASD diagnosis, with relatively large effect sizes for the paired comparisons. When these analyses were rerun controlling for Mullen language scores, group differences in empathic concern and self-distress were no longer significant.

Self-Understanding

Group differences were also apparent on the UCLA Self-Understanding Questionnaire, F (2, 68) = 17.34, p <.001, η2 =.23. The LR toddlers received higher scores than both the HR-noASD toddlers (p =.027, d = .72) and the toddlers with ASD (p <.001, d = 2.20). The HR-noASD toddlers also received higher scores than the toddlers with ASD (p =.003, d = 1.19). Self-understanding scores were significantly correlated with the 24-month Mullen Language composite (r (63) =.65, p <.001). Not surprisingly, when the Mullen Language composite was controlled, group differences in self-understanding were no longer significant (F (2,59)= 2.54, p = .088, partial eta squared = .079).

Associations between Empathy and Self-Understanding

Self-understanding was significantly correlated with ratings of empathic concern during both the crying baby (r (63) =.41, p =.001) and hurt finger probes (r (69) =.43, p <.001), and with self-distress (r (63) =.30, p =.018) and “engage parent” (r (63) =.40, p =.001) during crying baby. Thus, in the sample as a whole children with higher levels of self-understanding showed more concern across both empathy probes and more overall engagement with the parent during the crying baby episode. However, partial correlations controlling for language scores on the Mullen revealed that language skills may have accounted for most of these associations. With Mullen scores controlled, only the correlation between self-understanding and empathic concern during the crying baby probe remained significant (partial r (54) = .28, p = .036).

Associations between ADOS Severity Scores and Measures of Empathy and Self-Understanding

Pearson correlations were calculated between the empathy measures and the ADOS severity score, within the HR group as a whole and including the one LR toddler with a diagnosis. As expected, measures of empathic concern and self-distress were negatively correlated with later ASD symptom severity, although correlations were generally stronger for the hurt finger probe than the crying baby probe (empathic concern: crying baby, r (34) = −.28, n.s.; hurt finger, r (38) = −.41, p = .011; self-distress: crying baby, r (34) = −.36, p = .039; hurt finger, r (38) = −.50, p = .001). The behavioral measure of “engage parent” during crying baby was also negatively correlated with ADOS severity, r (34) = −.49, p =.003. Thus, HR toddlers who were less concerned about the examiner, less distressed themselves, or less engaged with their parent during the crying baby episode received higher ADOS severity scores at follow-up. Finally, the UCLA self-understanding score was negatively correlated with the ADOS severity score, r (38) = −.51, p = .001. However, these associations were confounded with language ability. When partial correlations were calculated controlling for Mullen scores only the association between ADOS severity and engage parent remained significant (partial r (28) = −.366, p = .047).

Discussion

These results demonstrate that toddler-aged siblings of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) who later receive a diagnosis of ASD themselves show less empathic responsiveness than low-risk (LR) toddlers across two very different scenarios, one assessing empathic responsiveness to a helpless and distressed infant, and the other assessing responsiveness to the expressed physical pain of an adult social partner. High-risk (HR) toddlers without a later diagnosis of ASD fell between the LR and ASD groups. Overall group differences were evident on global ratings of concern and distress and in specific behaviors directed to the parent during the crying baby probe.

Using a novel “ crying baby” empathy probe, which is salient and emotionally arousing for typically-developing toddlers, we found that toddlers with ASD not only exhibited less concern than the LR toddlers, they were also less likely to engage their parent than either the LR or HR-noASD toddlers by pointing, referencing, or talking about the crying baby. The HR-noASD toddlers were rated as showing lower levels of empathic concern relative to LR controls, but most initiated some communication with their parents when the baby cried. Indeed, whereas only one in three toddlers with a diagnosis of ASD solicited their parents, 100% of the LR and 78% of the HR-noASD toddlers engaged their parents during the episode. Despite the low level of emotional responsiveness among the children with ASD, there were no group differences in interest or curiosity about the crying baby. Almost every toddler in the study looked at and/or physically approached the distressed infant. Thus, the low level of other-oriented, empathic responsiveness shown by the toddlers with ASD cannot be accounted for by a lack of awareness of the baby’s cries. Rather it appears to reflect a more fundamental lack of social engagement with both the distressed infant and the parent. Overall, then, in this highly salient situation of a crying baby, toddlers with an older sibling with an ASD diagnosis showed dampened responses suggesting lack of concern, with the HR-noASD toddlers looking to the parent to alleviate or help them understand the situation. The LR typically-developing toddlers enlisted their parents during the episode, while also expressing more concern for the crying baby, indicating both emotional responsiveness to the situation and engagement with their parents as a source of comfort and help. Although group differences were attenuated when language level was controlled, they were not totally eliminated.

The results for the hurt finger probe showed a somewhat different pattern with both LR and HR-noASD toddlers demonstrating significantly more self-distress and empathic concern for the adult with whom they had been playing than did the toddlers with ASD. As can be seen in the figures, fully 75% of the diagnosed toddlers did not respond with any self-distress and 67% did not respond with any empathic concern when witnessing the examiner rub her finger in pain and describe how it hurt. The few toddlers with ASD who did respond received ratings of “1,” the lowest possible score indicative of some response. This is in sharp contrast to both the LR and HR-noASD toddlers, as most children in these two groups responded to the distress of their adult social partner, and the full scale (0-3) was needed to capture their behavior, as depicted in the figures. In summary, the children with ASD appeared either unaware of or indifferent to the examiner’s distress, with many focused primarily on the toy, whereas most of the HR-noASD and LR toddlers were both aware and concerned. Thus, consistent with other studies of HR infant siblings followed longitudinally (Hutman et al. 2010; McDonald and Messinger 2012), lower levels of empathic concern and self-distress appear to characterize HR toddlers with a later ASD diagnosis.

The two empathy scenarios are quite different and this may be relevant to the different patterns of responsiveness demonstrated by the HR-noASD toddlers relative to the LR toddlers and to the toddlers with ASD. It is important to note that the crying baby was hard to ignore as the cry was quite loud and persisted for two 20-second bouts. In fact, almost all children showed some reaction, but only the LR toddlers evidenced both concern and distal attempts to engage the parent. The HR-noASD children were aware that the baby was crying, but primarily engaged the parent, showing only limited reactions at an affective level. The children with ASD in general showed passive awareness and at most curiosity about the crying baby. In contrast to the crying baby scenario, the distressed adult was sitting with the child at a small table when she hurt her finger; in order to respond the child had to stop attending to the toy and instead attend to the examiner’s pained facial expression and vocal tone as well as her gestures (rubbing her hurt finger). Although this situation included a range of visual and auditory cues, they were more subtle than the baby’s cries, and required the child to read and integrate social cues across modalities. It was not possible to directly compare responses to the two probes because they differed in length, but examination of Table 2 indicates that empathic concern and self-distress were less pronounced during the hurt finger than the crying baby episode. Thus, contextual aspects of the two empathy probes resulted in different patterns of results, with HR-noASD toddlers responding similarly to LR toddlers when they witnessed an adult social partner express pain, but differing from the LR toddlers when confronted with a helpless crying baby. Toddlers with ASD, however, responded similarly in both contexts, demonstrating very low levels of empathic concern toward the crying baby or the distressed adult.

Not surprisingly, the three groups of toddlers differed on parental reports of self-understanding, with the toddlers with ASD obtaining especially low scores, but the HR-noASD toddlers still scoring below the level of the LR toddlers. As would be expected, based on existing theory (Hoffman, 2007; Moore, 2007) most measures derived from the empathy probes were significantly correlated with self-understanding. When toddlers have limited self-understanding, they also have more difficulty thinking about and empathizing with the inner states of other people, even when presented with quite clear and direct expressions of distress. Controls for language level, however, illustrate how strongly self-understanding and language development are intertwined at 22 months when both are showing rapid change.

Finally, ratings of empathic concern during the hurt finger probe, ratings of self - distress in both probes, and distal attempts to engage the parent during the crying baby probe were all moderately negatively associated with the severity of ASD symptoms within the HR group. The negative correlation between ADOS severity scores and engage parent may be especially important because all behaviors making up the parent engagement score involve social communication initiated by the child. Thus, spontaneous engagement with the parent during the crying baby probe may ultimately predict better social skills in HR toddlers. In addition, correlations of symptom severity with empathic concern and self-distress were somewhat stronger during the hurt finger episode. This appears to reflect the clearer differences between the ASD and HR-noASD groups during the hurt finger episode when the HR toddlers without a diagnosis were more likely to respond with both distress and concern and the toddlers with ASD seemed more disengaged, with many either ignoring or unaware of the examiner’s distress. These results are also consistent with McDonald and Messinger (2012) who reported that a global measure of empathy including arousal and concern obtained at 24 months was inversely associated with autism symptom severity at 30 months.

The findings from the current study both confirm previous research on early empathy as an indicator of autism risk (Hutman et al., 2010; McDonald & Messinger, 2012) and extend it in important ways. Reluctance to engage in social interaction cannot explain the response of the ASD group to the crying infant. The baby was not interacting with the children and no eye contact was possible. Moreover, an infant is helpless, unlike an adult, and its distress therefore signals an immediate, categorical need for intervention. Thus, the lack of empathic concern shown by the ASD group in the crying baby condition adds considerable validity to the inference that awareness of and responsiveness to others’ emotions is an early-appearing deficit in children with autism. Finally, by including a measure of self-understanding, we have identified not only an affective deficit in empathic responsiveness in children with ASD, but also a social-cognitive correlate of early-appearing group differences. That is, young children at risk for autism may be doubly affected in their responses to others’ emotions, with deficits in both social understanding and emotional responsiveness.

The pattern of responses of the HR-noASD group across the two empathy probes is intriguing. That they did not differ from the ASD group in their empathic concern toward the crying baby, but did engage their parent during the episode may suggest that they were overwhelmed by the baby’s cries, and therefore sought comfort from their parent. This possibility is strengthened by the finding that the HR-noASD group responded similarly to the LR toddlers when confronted with the hurt examiner, presumably a less emotionally-charged situation. The differences across these contexts may have implications for understanding emerging empathy in the HR-noASD toddlers some of whom may be showing subtle delays in emotion understanding and responses to distress, especially when confronted with a more salient and arousing situation like a crying infant.

The strengths of this study include the use of two separate empathy probes, careful follow-up by independent testers, and inclusion of both observational measures and parent reports of self-understanding. We also included a LR comparison group in contrast to the study by McDonald and Messinger which only examined empathic concern within a high risk sample. We are continuing to enlarge our sample and will obtain measures of empathic concern longitudinally through 34 months, along with other measures of social engagement, pretend play and imitation, and parent-child communication. Differences between the LR and HR-noASD children at 22 months may be subtle indicators of the broader autism phenotype in a subgroup of these children. Longer term follow-up and a larger sample will permit us to examine the HR-noASD children in more depth. For example, we will be able to examine subgroups within the HR-noASD group, comparing those with no obvious symptoms to those showing subclinical signs of ASD or other developmental delays.

The limitations of this study include the small sample size and the relatively high recurrence rate. In addition, HR infants were recruited into a related study of cognitive functioning and social engagement at 6, 11, or 16 months, raising the possibility that infants who entered the study later were beginning to show symptoms of ASD. To rule out this possibility, we correlated age at first visit by the HR infants with the dependent measures and none approached significance.

A further limitation of high risk sibling studies is the confound between language delay and measures of social functioning. In the current study, language delays especially in the toddlers with ASD attenuated group differences in empathic responding. Overall, when language scores on the Mullen were controlled in the analyses, many of the group differences were no longer significant and correlations between ADOS severity scores and dependent measures were also attenuated. This underscores the difficulties disentangling language development, general cognitive delay, and emerging empathy from one another in the early development of toddlers at high risk for ASD. With language controlled, however, group differences in engagement with parent remained significant and continued to differentiate the LR toddlers from the two HR groups and the correlation between ADOS severity and engage parent also survived control for language. This suggests the possibility that delays in language, self-understanding, and empathic concern partly reflect a more fundamental delay or deficit in social engagement as well as general cognitive delay. Only longitudinal data examining trajectories of these domains of functioning will shed light on this question. It remains to be seen whether deficits in empathy and social engagement will continue to differentiate not only toddlers with ASD from LR toddlers, but also from the HR-noASD group at the 28 and 34 month follow-up assessments.

These results also have clinical implications. Difficulties or delays in understanding and responding to the feelings of social partners, when evident prior to age two, may be both early signs of autism and appropriate targets for early intervention. The recognition of emotions in self and others and the ability to respond appropriately to emotional expressions of social partners are key to the development of reciprocal play interactions in toddlerhood and friendship development in the preschool years. Delays or deficits in empathic concern and self-understanding in toddlerhood may thus be part of a cascade of difficulties that young children with ASD experience and may contribute to their later difficulties in social relationships. Early interventions that encourage spontaneous social engagement with parents and other familiar adults appear especially important (Dawson, 2008). Parents are a major source of support for young children’s social learning and social cognition, as they help children attend to and understand others’ emotional states, and scaffold and model appropriate reactions to the emotions and behavior of others (Brownell et al., 2013). Toddlers who show only limited interest in others, be they parents or peers, will provide parents with fewer opportunities to facilitate socioemotional understanding and positive social interaction.

In summary, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the responsiveness of HR toddlers to both a distressed infant and an adult social partner, and also to code the degree to which toddlers attempt to enlist their parents in response to another’s distress. These measures not only differentiate between HR toddlers with and without a diagnosis, but appear to have implications for both early identification and intervention.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health R01 MH091036 to Dr. Campbell. We thank Dr. Nancy Minshew, Dr. Mark Strauss, Dr. Carla Mazefsky, Dr. Holly Gastgeb, Ms. Stacey Becker, and the staff at Autism Center of Excellence, University of Pittsburgh for overseeing recruitment and assessment of participating families. The Autism Center of Excellence was supported by award number HD055748 (PI Minshew) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Recruitment was also facilitated by the Clinical and Translational Science Institute, supported by the National Institutes of Health through Grant Numbers UL1 RR024153 and UL1TR000005. Thanks are due to Kristen Decker, Stephanie Fox, Phebe Lockyer, and Amanda Mahoney for overseeing data collection, and to Ari Fish, Kendra Guinness, Michelle Meyer, Elizabeth Moore, and Jenna Obitko for assistance with data collection and coding. Special thanks go to the parents and children who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Preliminary versions of these data were presented at the Society for Research in Child Development, Seattle, WA, April, 2013.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR (text revision) Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Brian J, Bryson SE, Garon N, Roberts W, Smith IM, et al. Clinical assessment of autism in high-risk 18-month-olds. Autism. 2008;12:433–456. doi: 10.1177/1362361308094500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA, Kopp CB. Transitions in toddler socioemotional development: Behavior, understanding, and relationships. In: Brownell CA, Kopp CB, editors. Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell C, Svetlova M, Anderson R, Nichols S, Drummond J. Socialization of early prosocial behavior: Parent talk about emotions is associated with sharing and helping in toddlers. Infancy. 2013;18:91–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2012.00125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charman T, Swettenham J, Baron-Cohen S, Cox A, Baird G, Drew A. Infants with autism: An investigation of empathy, pretend play, joint attention, and imitation. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:781–789. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawarksa K, Klin A, Paul R, Macari S, Volkmar F. A prospective study of toddlers with ASD: Short-term diagnostic and cognitive outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1235–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidov M, Zahn-Waxler C, Roth-Hanania R, Knafo A. Concern for others in the first year of life: Theory, evidence, and avenues for research. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G. Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 2008;20:775–803. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill KL, Calkins SD. Do aggressive/destructive toddlers lack concern for others?. Behavioral and physiological indicators of empathic responding in 2-year-old children. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:55–71. doi: 10.1017/s095457940300004x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Pickles A, Lord C. Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2009;39:693–705. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0674-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobson RP. Social relations, self-awareness, and symbolizing: A perspective from autism. In: Brownell CA, Kopp CB, editors. Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. pp. 423–450. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman M. l. Is altruism part of human nature? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1981;40:121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. The origins of empathic morality in toddlerhood. In: Brownell CA, Kopp CB, editors. Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. pp. 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Hutman T, Rozga A, DeLaurentis AD, Barnwell JM, Sugar CA, Sigman M. Response to distress in infants at risk for autism: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:1010–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Moreno AJ, Robinson JL. Maternal preconceptions about parenting predict child temperament, maternal sensitivity, and children’s empathy. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:1081–1092. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafo A, Zahn-Waxler C, Van Hulle C, Robinson JL, Rhee SH. The developmental origins of a disposition toward empathy: Genetic and environmental contributions. Emotion. 2008;8:737–752. doi: 10.1037/a0014179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, Cook E, Leventhal B, et al. Autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: A standard measure of social and communicative deficits associated with the pectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–695. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald N, Messinger D. Empathic responding in toddlers at risk for an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42:1566–1573. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1390-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. Understanding self and others in the second year. In: Brownell CA, Kopp CB, editors. Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations. Guilford Press; New York: 2007. pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen E. The Mullen Scales of Early Learning. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols S, Svetlova M, Brownell C. The role of social understanding and empathic disposition in young children’s responsiveness to distress in parents and peers. Cognition, Brain, Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2009;4:448–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols S, Svetlova M, Brownell C. Toddlers’ responses to infants’ negative emotions. Infancy. 2015;20(1):70–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S, Young GS, Belding A, Hill M, Hill A, et al. The broader autism phenotype in infancy: When does it emerge? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2014;53:398–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S, Young GS, Carter A, Messinger D, Yirmiya N, et al. Recurrence risk for autism spectrum disorders: A baby siblings research consortium study. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e488–e495. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth-Hania R, Davidov M, Zahn-Waxler C. Empathy development from 8 to 16 months: Early signs of concern for others. Infant Behavior and Development. 2011;34:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C. Social Communication Questionnaire. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sigman MD, Kasari C, Kwon J, Yirmiya N. Responses to the negative emotions of others by autistic, mentally retarded, and normal children. Child Development. 1992;63:796–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinrad TL, Stifter CA. Toddlers' empathy-related responding to distress: Predictions from negative emotionality and maternal behavior in infancy. Infancy. 2006;10:97–121. [Google Scholar]

- Stipek DJ, Gralinski JH, Kopp CB. Self-concept development in the toddler years. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:972–977. [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya N, Charman T. The prodrome of autism: early behavioral and biological signs, regression, peri- and post-natal development and genetics. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:432–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SK, Fox NA, Zahn-Waxler C. The relations between temperament and empathy in 2-year-olds. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1189–1197. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.5.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Radke-Yarrow M, Wagner E, Chapman M. Development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:126–136. [Google Scholar]