Abstract

This paper reports a study of the function and composition of social support networks among diverse lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) men and women (n = 396) in comparison to their heterosexual peers (n = 128). Data were collected using a structured social support network matrix in a community sample recruited in New York City. Our findings show that gay and bisexual men may rely on “chosen families” within LGBT communities more so than lesbian and bisexual women. Both heterosexuals and LGBs relied less on family and more on other people (e.g., friends, co-workers) for everyday social support (e.g., recreational and social activities, talking about problems). Providers of everyday social support were most often of the same sexual orientation and race/ethnicity as participants. In seeking major support (e.g., borrowing large sums of money), heterosexual men and women along with lesbian and bisexual women relied primarily on their families, but gay and bisexual men relied primarily on other LGB individuals. Racial/ethnic minority LGBs relied on LGB similar others at the same rate at White LGBs but, notably, racial/ethnic minority LGBs reported receiving fewer dimensions of support.

The prevalence of negative mental and physical health outcomes is significantly higher among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (LGBs) than their heterosexual peers (King, Semlyen, Tai, Killaspy, Osborn, Popelyuk, & Nazareth, 2008; Lick, Durso, & Johnson, 2013). These health disparities have been attributed to the fact that LGBs are exposed to unique stressors related to their stigmatized status in society (Meyer, 2003; Meyer & Frost, 2013; Thoits, 2010). As evidence continues to mount demonstrating the negative effects of stigma and stress on LGB health (Frost, Meyer, & Lehavot, 2015; Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Mays & Cochran, 2001), more research is needed to identify the resources that LGB individuals utilize to resist the negative effects of stigma (Harper & Schneider, 2003; Institute of Medicine, 2011). The present study focuses on one such factor: social support. Specifically, we examine similarities and differences in the composition and function of social support networks across sexual orientation, gender, and race/ethnicity focusing in particular on dimensions of support provided by family and similar others.

The Importance of Social Support

Social support is an important resource, influential in the successful negotiation of the many forms of stress that people encounter throughout their lives (Thoits, 1995). Social support manifests in the form of day-to-day emotional support (e.g., discussing worries), companionship (e.g., shared recreational and social activities), and informational support (e.g., decision-making advice) that people often need to cope with chronic strains in life. But instrumental support is often also sought out when people are faced with major life events, such as needing large sums of money when fired from a job, or having someone available to provide help and care when seriously ill (see Langford, Bowsher, Maloney, & Lillis, 1997 for a review). Indeed, people who have supportive social networks—family members and friends who provide emotional and material help—tend to be healthier than people who lack supportive social networks (Berkman, Glass, Brissette, & Seeman, 2000; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Tsai & Papachristos, 2015; Uchnio, 2009).

The concept of social support has been operationalized in various ways over the past several decades of research. Most common is the perception of social support, or the degree to which a person anticipates support of various kinds will be available to him or her should it be needed. An expansion of the general construct of anticipated social support has manifested in the social scientific exploration of people's social support networks (House, Umberson, & Landis, 1988; Tsai & Papachristos, 2015). Social support networks, however, also reflect structural support in their documentation of a person's connection with anticipated providers of support, their roles in the network, and the types of support they provide (Thoits, 1995).

Recent adult developmental research focusing on typologies of composition of social support networks has shown important differences between family-focused social support networks and friend-focused social support networks. Declines in depression over time were most pronounced in family-focused networks potentially because family members are better at providing emotional support, while cognitive functioning was higher in friend-focused networks, which may be attributable to support exchange activities that “stimulate cognitive functioning” (Fiori & Jager, 2012, p. 126).

Researchers have called for examination of social support in populations that are at risk for negative health outcomes due to social marginalization (e.g., Laverak & Labonte, 2000) and for understanding social support network composition in studies of population health (e.g., Berkman et al., 2000; Fiori & Jager, 2012). We address this in the present study, comparing the social support networks among diverse LGB populations and between LGB and heterosexual populations.

The Importance of Social Support in LGB Communities: Perspectives from Social Stress Theory and Minority Stress Theory

Social support has unique functions in the lives of LGB individuals as compared with heterosexuals, in that it may help them contend with the burden of social stress stemming from stigma and prejudice (Meyer, Schwartz, & Frost, 2008). Specifically, social stress theory indicates that individuals who are members of marginalized social groups are exposed to more stress and have access to fewer resources to cope with stress than those who are not socially disadvantaged, resulting in increased risk for negative health outcomes (Aneshensel, 1992). As an extension of social stress theory, minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) contends that LGB individuals experience unique forms of stress as a result of direct occurrences of discrimination, hypervigilance and expectations of rejection, the cognitive burden related to the need to manage the visibility of one's LGB identity, and the application of negative social attitudes towards the self. These minority stress processes have a negative effect on LGB mental and physical health (see Lick et al. 2013 and Meyer & Frost, 2013 for reviews) and account for disparities in mental and physical health outcomes between LGB and heterosexual populations (e.g., Mays & Cochran, 2001). Although attitudes towards LGB people have improved drastically over the past two decades (e.g., Brewer, 2014; Lax & Phillips, 2009), LGB people continue to experience a multitude of minority stressors from family, co-workers, and other interpersonal and structural sources in their lives (Badgett, Lo, Sears, & Ho, 2007; Hatzenbuehler, 2014; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009).

Minority stress theory further posits that in order to cope with these unique forms of minority stress, LGB individuals engage in community-level coping processes (Meyer, 2003), for example, accessing an LGB community center for counseling or support groups in coping with antigay violence. Participation within one's local LGB community, and even a sense of psychological connectedness to the community, can ameliorate the negative impact of minority stress (Frost & Meyer, 2012; Kertzner et al., 2009; Ramirez-Valles, 2002).

These special characteristics of minority coping suggest a unique role for non-familial support from others who are also LGB. For example, when individuals with concealable stigmas are in the presence of similar others (i.e., someone who is known to share their stigmatized identity/characteristic) their psychological well-being is improved (Frable et al, 1998). Minority stress theory suggests that social support from similar others can be helpful in ameliorating minority stress. However, we know little about the degree to which LGBs actually seek social support from members of their sexual minority communities. Now-classic ethnographic research has demonstrated that LGBs—often as a result of rejection from their biological families of origin—form “chosen families” or fictive kinship networks with other members of LGB communities (Weston, 1991). These chosen families are constituted through strong familial-like bonds with similar others who share the same sexual orientation, and therefore understand what it is like to be LGB and contend with an environment characterized by minority stress and limited by heterosexist opportunity structures. The support of similar others may be sought though participation in urban centers with a high concentration and visible presence of other LGBs. Although, living in a “gay neighborhood” does indicate a greater feeling of connectedness to a community of similar others (Mills et al., 2001), the ability to become integrated into these usually affluent neighborhoods is limited by financial resources (Barrett & Pollack, 2005). Additionally, a recent analysis of demographic shifts in the US population indicates that neighborhoods are becoming less segregated by sexual orientation, as same-sex couples with children (which tend to be more often female then male) may be moving out of traditionally urban gay neighborhoods (Spring, 2013). These findings suggest that important subgroup differences may exist within the LGB population in ability to access support from other members of the LGB community.

The support of other LGB individuals is likely important throughout stages of adolescence and adult development in which LGB individuals face unique challenges. Having similar others available for support, advice, and as role models can be helpful to young people negotiating the process of coming out, which is essential to reducing internalized homophobia and creating a positive trajectory of LGB identity development (Elizur & Mintzer, 2001; Jordon & Deluty, 1998). In light of increasing opportunities for legal recognition of same-sex couples, the support and advice of other same-sex couples is necessary to negotiate the challenges of being a member of a same-sex couple (Frost, 2011; Frost & Meyer, 2009; LeBlanc, Frost, & Wight, 2015), as well as the unique challenges of same-sex parenting and adoption (Goldberg, 2010). In later life, LGB elders may depend on other members of the LGB community given they are less likely than their heterosexual peers to have children and their partnerships and social networks have been decimated by the AIDS crisis (Barker, Herdt, & de Vries, 2006; de Vries, 2009).

Empirical Research on Social Support Among LGB Individuals

Existing studies that focus on adult LGB populations demonstrate a positive association between perceived support and indicators of well-being (Domingues-Fuentes et al., 2012; Kurdek, 1988) and sexual health (Lauby et al., 2012). LGB adolescents report lower quality social relationships than their heterosexual peers (Bos, Sandfort, de Bruyn, & Hakvoort, 2008; Corliss, Austin, Roberts, & Molnar, 2009), and that this difference accounts for mental health disparities observed between the two groups (Bos et al., 2008; Ueno, 2005). Furthermore, for sexual minority youth, social support from peers (in the form of Gay-Straight Alliances), parents, and other adults is essential for enhancing health, well-being, and educational outcomes— outcomes that are negatively impacted by minority stress experienced by sexual minority youth (Detrie & Lease, 2007; Hatzenbuehler, Birkett, Van Wagenen, & Meyer, 2014; Ryan et al., 2009; Toomy, Ryan, Diaz, & Russell, 2011). LGB peers have been shown to provide more support for dealing with minority stress than parents and heterosexual peers. In turn, sexuality-related support has buffered the negative effects of minority stress on emotional distress (Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl, & Malik, 2010).

Few studies have explicitly focused on the composition of LGB social support networks. Developmental research has indicated that the size of LGB youths' social support networks increases with age and degree of outness (Diamond & Lucas, 2004). Older and more “out” LGB youth also had more close friends in their social support networks but reported more worries about losing those friendships (i.e., drifting apart, or terminating due to conflict) than their heterosexual peers. In a study of HIV-positive individuals, younger LGBs reported more social support from friends than their heterosexual peers, while no differences in friend support were observed based on sexual orientation in older cohorts (Emlet, 2006). A study of the social support networks of aging LGB individuals (60 years old and older) found that close friends, rather than family members, was the category of persons most commonly represented in social support networks (Grossman et al., 2000). This finding is important because support from friends has been associated with better mental health among older LGBs, while support from family has not (Masini & Barrett, 2008). Friends, rather than partners, family, and co-workers, were also found to be the most frequent provider of support to individuals in same-sex couples (Kurdek, 1988).

These studies highlight how the composition of social support networks may function differently for LGBs and heterosexuals. For example, findings among LGBs that social support from friends, rather than family, is beneficial to mental health (Masini & Barrett, 2008) contrast with findings in the general population that familial social support is more beneficial for mental health than support from friends (e.g., Fiori & Jager, 2012). Comparing the composition of the social support networks of LGBs with their heterosexual peers can demonstrate whether or not they are indeed different in the important ways that minority stress theory suggests.

Gender and Racial/Ethnic Variability in Social Support among LGBs: An Intersectionality Perspective

As social stress theory and minority stress theory both suggest, individuals who are members of multiple minority groups may have less access to social support due to compounded social disadvantaged and multiple sources of stigma (e.g., Meyer et al., 2008). Studies of social support within Black and Latino communities note its positive association with health outcomes (e.g., Alegria, Sribney, & Mulvaney-Day, 2006). After adjusting for the confounded nature of socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity, little to no differences remain in the social support networks of White and racial/ethnic minority individuals in the general population (Griffin et al., 2006), as well as specifically among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men (e.g., Tate, Van Den Berg, Hansen, Kochman, Sikkema, 2006).

Important variability may exist at the intersections of race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation (Balsam et al., 2011; Battle & Crum, 2007). Studies of racial/ethnic minority LGBs indicate they have smaller social support networks than White LGBs (Meyer et al., 2008). Black and Latino LGBs may experience more rejection from their families and same-race peers as well as their church than White LGBs, due to heightened religiosity within Black and Latino communities (e.g., Barnes & Meyer, 2012; Harai et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 1996; Meyer & Ouellette, 2009). Further, the emphasis on adherence to male gender roles (e.g., Lemelle & Battle, 2004) may make it harder for gay and bisexual Latino and Black men to be out about their sexual orientation and to garner support from family and same-race peers than it is for White LGBs and racial/ethnic minority lesbian and bisexual women (e.g., Mays, Chatters, Cochran, & Mackness, 1998; Ostrow & Whitaker, 1991).

Intersections of race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation may also reveal importance differences in support from other LGB individuals. Not all members of the LGB community may have access to the same sources, level, and quality of social support (Barrett & Pollack, 2005). For example, research has portrayed LGB communities, organizations, and neighborhoods in most urban centers as predominantly White and catering to the needs of gay men (Binnie & Skeggs, 2004; Han, 2007; Ward, 2008). Furthermore, women report less community participation than men, and racial/ethnic minority individuals report less participation than Whites (Meyer et al., 2008). Thus, understanding intersectional differences in the presence of both family and other LGBs in individuals' social support networks is necessary given the importance of social support from LGB similar others, as well as the tendency of Black and Latino individuals to place greater importance on familial connections than Whites (e.g., Raymond, Rhoads, & Raymond, 1980; Vaux, 1985).

The Current Study

We examined whether the composition and function of social support networks differed among a diverse community sample of LGB adult men and women and a comparison sample of White heterosexual adult men and women. Specifically, we address the following research questions relevant to social stress and minority stress theories: (a) To what degree do composition and function of social support networks differ between LGB and heterosexual adults? (b) To what extent do LGBs' social support networks include “chosen families” (Weston, 1991), and do LGB and heterosexual individuals' networks differ in their greater reliance on non-familial support providers relative to family members? (c) To what extent do the social support networks of White LGBs and LGB persons of color consist of other providers of support with the same race/ethnicity and sexual orientation?

Method

The data analyzed in the current study were obtained as part of [blinded] a large NIMH-funded epidemiological study that investigated the relationships among stress, identity, and mental health in diverse LGB and heterosexual populations in New York City (NYC). Participants in [blinded] were 396 LGB and 128 heterosexual individuals. (Detailed information is available online at [blinded]).

Participants and Procedure

Participants (N = 524) were sampled from venues in New York City chosen to represent a wide diversity of cultural, political, ethnic, and sexual communities. Sampling venues included business establishments (e.g., bookstores, cafes), social groups, and outdoor areas (e.g., parks), as well as snowball referrals. Recruitment of participants occurred in two phases. In the first phase, 25 outreach workers visited a total of 274 venues in 32 different NYC zip codes. For each potential participant, recruiters administered a brief screening form that would determine eligibility for participation in the study. In the second phase, eligible participants were contacted by research interviewers and invited to participate in a face-to-face interview. Participants were eligible if they were 18-59 years-old, NYC residents for two years or more who could communicate in English and self-identified as: a) lesbian, gay, or bisexual or straight/heterosexual; b) male or female and were assigned the same sex at birth; and c) White, Black or Latino (participants may have used other identity terms, such as queer or Hispanic, in referring to these social groups). We used quota sampling to ensure approximately equivalent numbers of participants across sexual orientation, gender, race/ethnicity, and age group (18-30 and 31-59). The straight comparison group consisted only of White men and women [blinded]. The response and cooperation rates were 60% and 79% (AAPOR, 2005) and did not vary appreciably by sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, or gender (χ2 s ≤ 0.78, ps ≥ .38).

Recruitment efforts were successful at reaching individuals who resided in diverse NYC neighborhoods and avoiding concentration in particular “gay neighborhoods” that is often characteristic of sampling of LGB populations. Participants resided in 128 different NYC zip codes; no more than 4% of the sample resided in any one zip code area. Detailed sample demographic characteristics have been reported elsewhere [blinded]. Participants completed in-person interviews lasting a mean of 3.82 hours (SD = 55.00 minutes) aided by the use of a Computer-Assisted Personal Interview. They were paid $80 upon completing the interview.

Measures

The study included an instrument from Fisher (1977) adapted by Martin and Dean (1987) for use in gay/bisexual men to assess the composition of social support networks [blinded]. Question prompts included items such as “who could you rely on in making important decisions?”, “who could you go to if you needed to borrow a large amount of money?”, and “who have you talked to about personal worries?”. Respondents provided the first name or initials of the individuals who provided them with each type of support in the year prior to the interview. For each person named in respondents' social support networks, respondents were asked basic demographic information regarding the person's gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, age, educational level, and whether or not the individuals currently live with them. They were also asked their relationship to the support provider. Provider type categories included intimate partner, parent, sibling, other family, friend, volunteer in agency (e.g., buddy system, AA sponsor), or paid worker. For purposes of analysis, provider type was categorized into three categories: family, relationship partner, and others.

Domains of support were classified into two categories for analysis: everyday support and major support. Dimensions of everyday and major forms of support correspond to dimensions of everyday support and support in problem situations assessed by other measures of social support interactions (e.g., Kempen & Van Eijk, 1995). The domain of everyday support was constructed to be inclusive of companionship, emotional, and informational support and was measured by asking participants whether members of their networks could be counted on for small favors, social activities, to discuss worries, share happiness, help with household chores, confide in, and help with decision-making. The major support category corresponded to instrumental and tangible support, and was measured by asking whether members of participants' networks could be counted on to lend large sums of money and help them when they are sick.

Analysis Plan

First, the number of people listed in participants' social support networks was computed (0 – 15). Next, summary variables were computed that reflected the total number of categories of everyday support (0 to 5) and major support (0 to 2) in which participants reported any provision of support. An algorithm was created that computed the total number of individuals within participants' social support networks providing each type of support, separately by type of provider (i.e., family, partner, other), as well as providers' gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation. Given individual social support networks varied in size, these totals were then divided by the total number of people listed in participants' social support networks, resulting in percentage scores reflecting the proportion of each type of support provided by different types of providers.

Descriptive analyses examined the distribution of the social support variables across the eight subgroups in the study defined at the intersections of sexual orientation, gender, and race ethnicity. Multiple linear regression models compared groups based on binary group difference variables for sexual orientation (LGB = 1 vs. heterosexual = 0), gender (female = 1 vs. male = 0), and race/ethnicity (racial/ethnic minority = 1 vs. White = 0) with regard to the number of dimensions of major and everyday support received. Because we had no racial/ethnic minority heterosexual participants, the group difference test of race/ethnicity examined differences between White LGBs and racial/ethnic minority LGBs only. Therefore, the group difference test for sexual orientation compared White heterosexuals with White LGBs, because models simultaneously included parameters for both racial/ethnic minority status and sexual orientation. All analyses were controlled for unemployment, education, and net worth.

Results

Sexual Orientation, Gender, and Race/Ethnicity Differences in Social Support

We examined underlying patterns of group differences in all dimensions of social support based on sexual orientation, gender, and race/ethnicity. Table 1 presents tests of group differences in the dimensions of support provided by members of participants' social support networks. There were no differences based on sexual orientation or gender in the number of dimensions of everyday support received. But, racial/ethnic minority LGBs had less everyday support than White LGBs. There were no differences based on sexual orientation, gender, or race/ethnicity in the number of dimensions of major support received.

Table 1. Sexual Orientation, Gender, and Racial/Ethnic Differences in Dimensions of Support.

| Dimensions of Everyday Support (0-5) | Dimensions of Major Support (0-2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| B | SE | p | B | SE | p | |

| Intercept | 4.84 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 1.80 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| <= High School | ||||||

| Diploma | -0.33 | 0.08 | 0.00 | -0.22 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| Negative Net Worth | -0.06 | 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.86 |

| Unemployed | -0.17 | 0.08 | 0.04 | -0.10 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Female | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.38 |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | -0.16 | 0.07 | 0.03 | -0.07 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| LGB | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.49 | -0.03 | 0.06 | 0.54 |

|

| ||||||

| F | 7.70 | 5.97 | ||||

| R2 | 0.09 | 0.07 | ||||

NOTE: Table presents results of simultaneous multivariable linear regression analyses. All racial/ethnic minority individuals are also LGB.

Composition of LGB and Heterosexual Social Support Networks

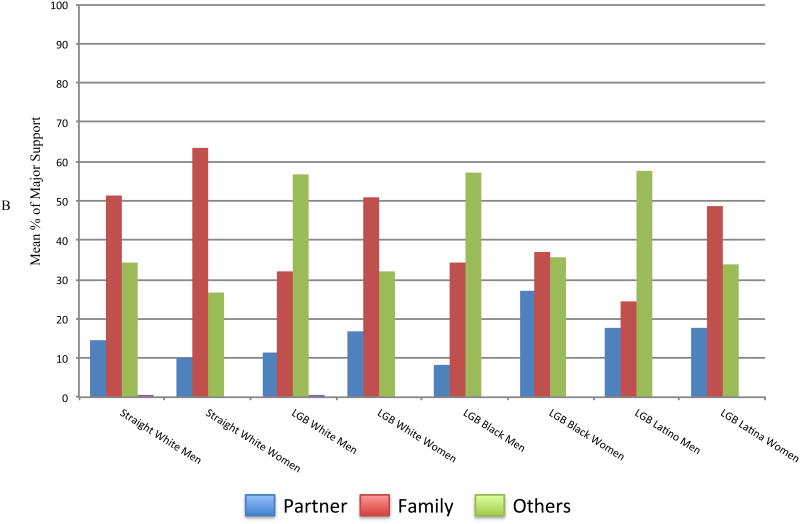

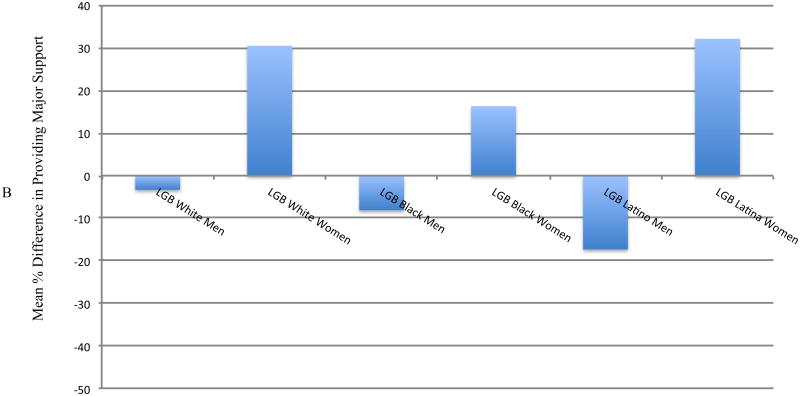

Figure 1 presents the percentage of everyday (section A) and major (section B) support received from intimate partners, family, and others (heterosexual and LGB) separately for eight subgroups: straight White men, straight White women, LGB White men, LGB White women, LGB Black men, LGB Black women, LGB Latino men, LGB Latina women. The figures show that patterns of support for everyday needs were similar across all groups: individuals relied primarily on other providers for such support, as opposed to family or relationship partners. Patterns of support differed with regard to major support needs. When in need of major support, White straight men and women and all lesbians and bisexual women relied mainly on family members, but gay and bisexual men relied primarily on other people, such as friends and co-workers, when they needed major support. It is notable that these patterns did not differ by race/ethnicity; similar patterns of reliance on others for major support were observed for White, Black, and Latino gay and bisexual men.

Figure 1. Percentage of Social Support Networks Providing Everyday (A) and Major (B) Support by Aggregate Provider Type.

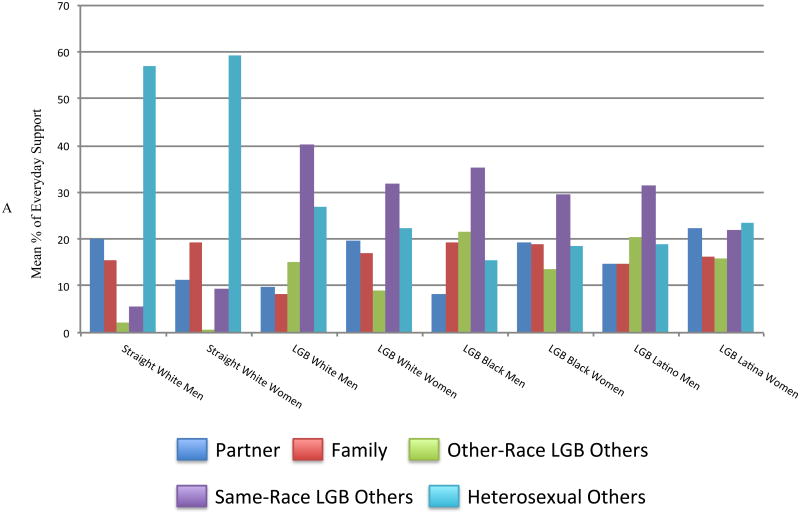

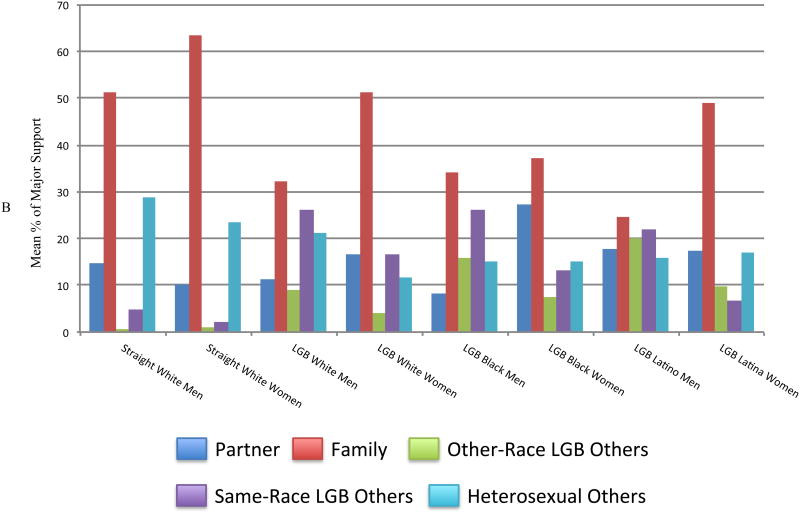

In Figure 2 we provide further examination of the “other” category of support provider. We assessed whether these other supporters were LGB or straight and whether they were of the same or of a different race/ethnicity as the participant. As can be seen in Figure 2a, when it came to everyday support, White straight men and women relied primarily on others who were also straight; LGB men and women relied primarily on others who were also LGB—mostly other LGBs who were of the same race/ethnicity as themselves (this was marginal for Latina lesbian and bisexual women). Regarding major support (Figure 2b), of the nonfamily individuals providing support to gay and bisexual men, most were LGB persons of the same race/ethnicity. Support from other LGB persons of a different race/ethnicity than the participant was lower, but it was higher among Black and Latino gay and bisexual men compared with White gay and bisexual men. Even though lesbian and bisexual women received most support from family members, when it came to support from others, the pattern was similar to the pattern we found for gay and bisexual men (but it was least pronounced among LGB Latina women).

Figure 2. Similar Other Distribution in Percentage of Social Support Networks Providing Everyday (A) and Major (B) Support.

To assess differences among the LGB subgroups in the presence of family members vs. LGB others in their support networks, we computed difference scores reflecting the gap between the proportion of family and LGB others (regardless of race/ethnicity) in individuals' social support networks. A gap of support (GOS) score of 0 indicated no difference in family vs. LGB others as sources of support, a positive GOS score indicated more family than LGB others, and negative GOS score indicated more LGB others than family support. To illustrate, a GOS score of -20 would indicate that a participant's support network included 20% fewer family members than LGB others. Mean GOS scores for all LGB subgroups are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ratio of support (ROS) scores comparing support provided by family and LGB others in the domains of everyday and major social support among LGB participants.

| Everyday Support | Major Support | |

|---|---|---|

| Gay and Bisexual Men | ||

| White | -47.21a | -3.29a |

| Black | -37.74 | -8.10a |

| Latino | -37.33 | -17.29ac |

| Lesbian and Bisexual Women | ||

| White | -23.96b | 30.45b |

| Black | -24.45b | 16.29d |

| Latino | -21.45b | 32.09b |

|

| ||

| F | 3.31, p < .01 | 6.55, p < .001 |

Note: Positive numbers indicated more family support than LGB others support. Negative numbers indicated more LGB other support than family support. Means within each column with differing superscripts indicate statistically significant differences (p < .05) based on one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD post-hoc tests corrected for multiple comparisons.

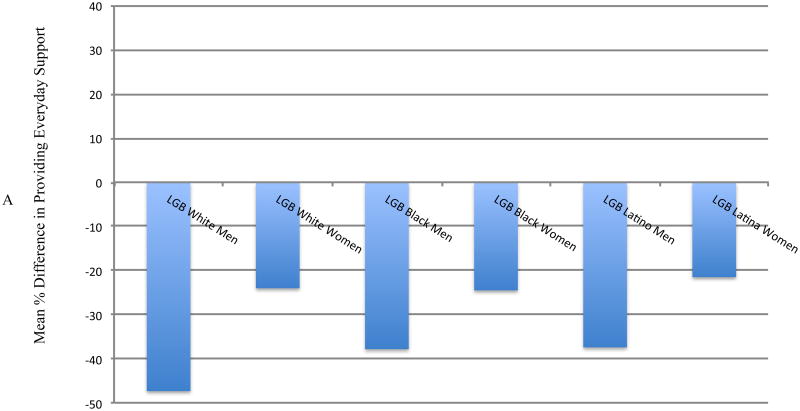

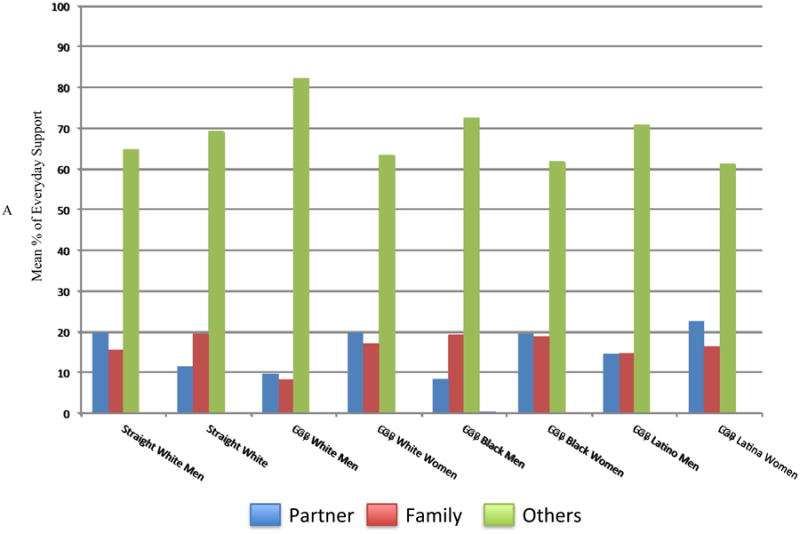

We then compared GOS scores across subgroups based on gender and race/ethnicity using one-way ANOVA tests with post-hoc test of difference in GOS scores corrected for multiple comparisons using Tukey's HSD. For everyday support (Figure 3a), LGBs in each of subgroups had a greater representation of LGB other support providers than family member support providers (i.e., all GOS scores were negative). This difference was more pronounced among gay and bisexual White men than among lesbian and bisexual White women (GOS mean difference = -23.26, p = .04), lesbian and bisexual Black women (GOS mean difference = -22.77, p = .05), and lesbian and bisexual Latina women (GOS mean difference = -25.76, p = .02).

Figure 3.

Difference between Percentage of Family and Percentage of LGB Others Providing Everyday (A) and Major (B) Support.

Positive numbers indicated more family support than LGB others support. Negative numbers indicated more LGB other support than family support.

For major support (Figure 3b), all female subgroups had positive GOS scores, indicating higher representations of family members as providers of major support than LGB others. In contrast, all male subgroups had negative GOS scores, indicating higher representations of LGB others as providers of major support than family members. Significant differences existed between lesbian and bisexual White women and gay and bisexual White men (GOS mean difference = 33.74, p = .03), gay and bisexual Black men (GOS mean difference = 38.54, p = .01), and gay and bisexual Latino men (GOS mean difference = 47.74, p < .01). Lesbian and bisexual Latina women were also significantly different from gay and bisexual White (GOS mean difference = 35.39, p = .02), Black (GOS mean difference = 40.19, p = .01), and Latino men (GOS mean difference = 49.38, p < .01). Lesbian and bisexual Black women differed significantly only from gay and bisexual Latino men (GOS mean difference = 33.58, p =.05).

Discussion

Our findings show differences in patterns of social support between LGBs and heterosexuals. Specifically, when it came to more minor, everyday support both heterosexuals and LGBs relied on people similar to themselves—heterosexuals received most of their support from other heterosexuals and LGBs received most of their support from other LGBs, most often from LGBs who were of the same race/ethnicity as themselves. When it came to major support, such as asking for a large sum of money in an emergency, a clear difference emerged between LGB men and women. Family members made up the highest percentage of lesbian and bisexual women's sources of major support, which was also the case for heterosexual men and women. In contrast, gay and bisexual men's highest percentage of major support came from other individuals, who were mostly, but not only, LGB and of the same race/ethnicity as themselves. Black and Latino gay and bisexual men relied on other LGBs of a different race/ethnicity than themselves more so than White gay and bisexual men. This pattern was also observed among lesbians and bisexual women.

The finding that racial/ethnic minority LGBs had fewer dimensions of everyday support covered by members in their social support networks is troubling given racial/ethnic minority LGBs are also exposed to more minority stress and have fewer overall providers of support than White LGBs (Meyer et al., 2008). Having smaller social support networks is not necessarily indicative of lower quality or less effective social support. However, it does indicate that there are fewer providers covering fewer dimensions of support in the lives of racial/ethnic minority LGBs. Thus, they may have a harder time than White LGBs finding support when they need it if opportunities of support provision are limited. It is important to note that the analyses adjusted for potential confounding by education, net worth, and employment status.

That LGB people rely on friends for support is not surprising. Weston (1991) referred to LGBs' networks as families of choice, as distinct from families of origin. As Weston and others (Nardi, 1999) have noted, families of origin sometimes reject a LGB child, leaving him or her to seek support within the LGB community. But the patterns of differences in major social support among LGB individuals is intriguing, suggesting an important gender difference that we did not expect based on prior theory and ethnographic research. It is plausible, or at least consistent with this finding, that lesbians and bisexual women's networks were more similar to heterosexuals' because lesbians and bisexual women are rejected by their family of origin less frequently than gay and bisexual men or because lesbians and bisexual women are better at maintaining relationships with family than are gay and bisexual men. We do not know what explains these findings, but extrapolating from research on heterosexuals' attitudes towards LGBs (e.g., Herek, 2000), these findings may result from family members harboring more intense prejudice and feeling less comfortable around gay and bisexual men than lesbian and bisexual women, making it easier for the latter to maintain familial connections in times of need for major support. These and other potential explanations related to possible differences in gender norms and socialization ought to be explored in future research.

In general, patterns of both everyday and major support within LGB individuals' social support networks were similar for White, Black, and Latino participants. This is a notable finding because it contradicts the perception that sexual orientation is treated differently in racial/ethnic minority communities than it is among Whites. Our findings suggest that Black and Latino gay and bisexual men are embedded in an LGB community to a similar degree as White gay and bisexual men and that their networks of LGB people consist mostly other people of color. This is consistent with other findings we have reported [blinded] and may be a reflection of general patterns of racial/ethnic network segregation in the US (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). However, it highlights an important point: LGB communities are diverse and to say that LGBs of color are embedded in a LGB community is not to say that they are embedded in a White LGB community. As our findings show, the support networks of LGBs of color are comprised primarily of other LGB persons of color.

Research indicates that racial/ethnic minority individuals may employ complex, but sometimes separate, networking strategies that allow for connections to both LGB and racial/ethnic minority communities (Wilson & Harper, 2012). This may be necessary to get support to contend with racism from others within predominantly White LGB communities (e.g., Balsam et al. 2011) and heterosexism in racial/ethnic minority communities (Kraft, Beeker, Stokes, & Peterson, 2000; Martinez & Sullivan, 1998). One way that LGB people of color can successfully establish and maintain supportive ties to both LGB and racial/ethnic minority communities is by constructing social support networks that contain similar others who are LGBs and members of their same racial/ethnic minority communities. In this regard, homophily—or the tendency to associate with other people who are most like oneself (McPherson et al., 2001)—may serve a protective function for LGBs, and especially LGBs of color. Having a sizable proportion of same-race similar others in one's support network, as we have described here, may represent attempts on the part of racial/ethnic minority LGBs to simultaneously connect to both the LGB community and their racial/ethnic communities of origin. Receiving support from same-race similar others in this regard is likely instrumental in negotiating minority stress at the intersection of heterosexism and racism, given same-race similar others will have similar experiences and may be more effective in providing support, sympathy, and understanding than White LGBs.

Study Limitations

Although we study the function of support (support for everyday vs. major issues) we cannot make any claims regarding the quality or effectiveness of social support. Moreover, the instrument we used to assess social support does not indicate actual provision of such support, only the respondents' sense of what support is available to them. Additionally, the “other” provider type in the present analysis does not allow for the distinction between friends (the overwhelming common provider type in this category) and support providers who may have been co-workers, or service providers. Future research should examine the extent to which support is actually sought and provided and employ more nuanced distinctions among types of support providers.

The design of our sample allowed for important subgroup comparisons based on gender and race/ethnicity within the sample of LGB individuals. This facilitated our aims to explore variability in social support networks at the intersections (Cole, 2009) of race/ethnicity and gender within the LGB population. The study design (see blinded) did not include comparison groups of Black and Latino heterosexual men and women. Thus our conclusions regarding differences between White and racial/ethnic minority individuals are limited to LGB individuals only. Our use of quota-based sampling and our focus in NYC was designed to obtain analyzable diversity across gender and race/ethnicity within the sexual minority population, but limits our ability to generalize the estimates obtained in the present analyses to the larger LGB population.

Also, our study was conducted in NYC, which has a large, visible, and diverse LGB community. However, participants were required to be English speakers and live in NYC for at least two years in order to be eligible for the study. Therefore we lacked diversity in the sample with regard to recent immigrants and individuals who may have faced difficulty in connecting with LGB others as a result of language barriers. Additionally, the diversity of NYC's LGB community may have permitted the racial/ethnic patterns we observed because of presence of same-race similar others in Black and Latino LGBs' social networks, that may not have been possible for people of color in other locales with less diverse LGB communities. Future research should examine geographic differences in the composition and function of LGB individuals' social support networks to test whether or not our findings can be replicated in other locations. This is especially important given exposure to minority stress has been shown to differ by geographic location (Paceley, Oswald, & Hardesty, 2014; Swank, Frost, & Fahs, 2012).

Future Directions

The differences in social support networks we observed have important implications for research on minority stress and LGB health more broadly. From a community coping perspective (e.g., Meyer 2003; Meyer & Frost, 2013; Ramirez-Valles, 2002), LGB others may be best able to help LGB individuals cope with the social stress that arises from stigmatization and discrimination. Given other LGB individuals share similar identities and lived experiences, they may be better able to understand the nature of minority stress and provide specific support that heterosexuals may not be capable of providing given their lack of personal connection to the minority stress experience. Support for this argument can be found in the ameliorative role that the presence of similar others can have for the health and well-being of LGB individuals (Frable et al., 1998; Johns et al., 2013). Future research is needed to examine whether in fact support from LGB others is equally or more effective than support from heterosexuals in coping with minority stress and its relationship to health and well-being. It is likely that the impact of support will differ by the type of stressor the individual copes with and other contextual characteristics. Research that considers the context of stress, coping, and support may provide important insight into the workings of stress, social support, coping, and health. Additional research is also needed to understand why lesbian and bisexual women were more reliant on family for major support than gay and bisexual men and what impact, if any, the differing forms of support may have. Future research should address the roles that the composition of adult LGBs' social support networks plays in the minority stress experience, and whether the kinds of variability in composition and function of social support networks identified in the current study play a role in within-group differences in the health and well-being of diverse LGB populations.

Contributor Information

David M. Frost, Columbia University

Ilan H. Meyer, University of California, Los Angeles

Sharon Schwartz, Columbia University.

References

- The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 2005 Accessed Online at: http://www.aapor.org/pdfs/standarddefs_3.1.pdf.

- Aneshensel CS. Social stress: Theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology. 1992:15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Badgett MV, Lau H, Sears B, Ho D. Bias in the workplace: Consistent evidence of sexual orientation and gender identity discrimination. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Balsam KF, Molina Y, Beadnell B, Simoni J, Walters K. Measuring multiple minority stress: the LGBT People of Color Microaggressions Scale. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17(2):163. doi: 10.1037/a0023244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker J, Herdt G, de Vries B. Social support in the lives of lesbians and gay men at midlife and beyond. Sexuality Research & Social Policy: Journal of NSRC. 2006;3(2):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes DM, Meyer IH. Religious affiliation, internalized homophobia, and mental health in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(4):505–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett D, Pollack L. Whose gay community? Social class, sexual identity, and gay community involvement. The Sociological Quarterly. 2005;46(3):437–456. [Google Scholar]

- Battle J, Crum M. Black LGB health and well-being. In: Meyer IH, Northridge ME, editors. The health of sexual minorities. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. pp. 320–352. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51(6):843–857. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnie J, Skeggs B. Cosmopolitan knowledge and the production and consumption of sexualized space: Manchester's gay village. The Sociological Review. 2004;52(1):39–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bos HMW, Sandfort ThGM, de Bruyn EH, Hakvoort E. Same–sex attraction, social relationships, psychological functioning, and school performance in young adolescents. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:59–68. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer PR. Public Opinion About Gay Rights and Gay Marriage. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. 2014;26(3):279–282. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64(3):170. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Austin SB, Roberts AL, Molnar BE. Sexual risk in “mostly heterosexual” young women: Influence of social support and caregiver mental health. Journal of Women's Health. 2009;18(12):2005–2010. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detrie PM, Lease SH. The relation of social support, connectedness, and collective self-esteem to the psychological well-being of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Homosexuality. 2007;53(4):173–199. doi: 10.1080/00918360802103449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, Lucas S. Sexual-minority and heterosexual youths' peer relationships: Experiences, expectations, and implications for well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14:313–340. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Fuentes JM. Social support and life satisfaction among gay men in Spain. Journal of Homosexuality. 2012;59(2):241–255. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2012.648879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty N, Willoughby BB, Lindahl KM, Malik NM. Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39(10):1134–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elizur Y, Mintzer AA. framework for the formation of gay male identity: Processes associated with adult attachment style and support from family and friends. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2001;30(2):143–67. doi: 10.1023/a:1002725217345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlet CA. A comparison of HIV stigma and disclosure patterns between older and younger adults living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2006;20(5):350–358. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiori KL, Jager J. Social support networks and health across the lifespan: A longitudinal, pattern-centered approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2012;36:117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer CS. Network analysis and urban studies. In: Fischer CS, et al., editors. Networks and Places: Social Relations in the Urban Setting. New York, NY: Free Press; 1977. pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Frable DES, Platt L, Hoey S. Concealable stigmas and positive self-perceptions: Feeling better around similar others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:909–922. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.4.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH. Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:97–109. doi: 10.1037/a0012844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost DM, Meyer IH. Measuring community connectedness among diverse sexual minority populations. Journal of Sex Research. 2012;49(1):36–49. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.565427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE. Studying complex families in context [invited commentary] Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin ML, Amodeo M, Clay C, Fassler I, Ellis MA. Racial differences in social support: kin versus friends. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(3):374. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grollman EA. Multiple forms of perceived discrimination and health among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2012;53(2):199–214. doi: 10.1177/0022146512444289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman AH, D'Augelli AR, Hershberger SL. Social support networks of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults 60 years of age and older. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2000;55:171–179. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.3.p171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C. They don't want to cruise your type: Gay men of color and the racial politics of exclusion. Social Identities. 2007;13(1):51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Schneider M. Oppression and discrimination among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered people and communities: A challenge for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(3-4):243–252. doi: 10.1023/a:1023906620085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does LGB stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(5):707. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma and the health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2014;23(2):127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai M, Winkel MH, Popan JR. The role of machismo in prejudice toward lesbians and gay men: Personality traits as moderators. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;70:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241(4865):540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IOM (Institute of Medicine) The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Pingel ES, Youatt EJ, Soler JH, McClelland SI, Bauermeister JA. LGBT Community, Social Network Characteristics, and Smoking Behaviors in Young LGB Women. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;52(1-2):141–154. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9584-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan K, Deluty RH. Coming out for lesbian women: its relation to anxiety, positive affectivity, self-esteem, and social support. Journal of Homosexuality. 1998;35:41–63. doi: 10.1300/J082v35n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC psychiatry. 2008;8(1):70. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempen GIJM, Van Eijk LM. The psychometric properties of the SSL12-I, a short scale for measuring social support in the elderly. Social Indicators Research. 1995;35(3):303–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, Stirratt MJ. Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: The effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:500–510. doi: 10.1037/a0016848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft JM, Beeker C, Stokes JP, Peterson JL. Finding the “community” in community-level HIV/AIDS interventions: Formative research with young African American men who have sex with men. Health Education and Behavior. 2000;27(4):430–441. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Correlates of negative attitudes toward homosexuals in heterosexual college students. Sex Roles. 1988;18:727–738. [Google Scholar]

- Langford CPH, Bowsher J, Maloney JP, Lillis PP. Social support: a conceptual analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;25(1):95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997025095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauby, et al. Having supportive social relationships is associated with reduced risk of unrecognized HIV infection among black and Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behavior. 2012;16:508–515. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lax JR, Phillips JH. Gay rights in the states: Public opinion and policy responsiveness. American Political Science Review. 2009;103(03):367–386. [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc AJ, Frost DM, Wight R. Minority stress and stress proliferation among same-sex and other marginalized couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jomf.12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemelle AJ, Jr, Battle J. Black masculinity matters in attitudes toward gay males. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;47(1):39–51. doi: 10.1300/J082v47n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lick DJ, Durso LE, Johnson KL. Minority stress and physical health among LGBs. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2013;8(5):521–548. doi: 10.1177/1745691613497965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL, Dean LL. Unpublished manuscript. Columbia University; New York: 1987. Ego-dystonic homosexuality scale. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez DG, Sullivan SG. African American gay men and lesbians: Examining the complexity of gay identity development. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 1998;I:243–264. [Google Scholar]

- Masini BE, Barrett HA. Social support as a predictor of psychological and physical well-being and lifestyle in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults aged 50 and over. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services. 2008;20:91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Chatters LM, Cochran SD, Mackness J. African American families in diversity: Gay men and lesbians as participants in family networks. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. 1998;29:73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1869–1876. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:415–444. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Frost DM. Minority stress and health of LGBs. In: Patterson CJ, D'Augelli AR, editors. Handbook of Psychology Sexual Orientation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Ouellette SC. Unity and purpose at the intersections of racial/ethnic and sexual identities. In: Hammack PL, Cohler BJ, editors. The Story of Sexual Identity: Narrative, Social Change, and the Development of Sexual Orientation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, Frost DM. Social patterning of stress and coping: Does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Social Science & Medicine. 2008;67:368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills TC, Stall R, Pollack L, Paul JP, Binson D, Canchola J, Catania JA. Health-related characteristics of men who have sex with men: a comparison of those living in “gay ghettos” with those living elsewhere. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(6):980–983. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardi PM. Gay men's friendships: Invincible communities. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J. The protective effects of community involvement for HIV risk behavior: A conceptual framework. Health Education Research. 2002;17:389–403. doi: 10.1093/her/17.4.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond JS, Rhoads DL, Raymond RI. The relative impact of family and social involvement on Chicano mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1980;8(5):557–569. doi: 10.1007/BF00912592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C. Engaging Families to Support Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: The Family Acceptance Project. Prevention Researcher. 2010;17(4):11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Spring AL. Declining segregation of same-sex partners: Evidence from Census 2000 and 2010. Population Research and Policy Review. 2013;32(5):687–716. doi: 10.1007/s11113-013-9280-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirratt MJ, Meyer IH, Ouellette SC, Gara MA. Measuring identity multiplicity and intersectionality: Hierarchical classes analysis (HICLAS) of sexual, racial, and gender identities. Self and Identity. 2007;7(1):89–111. [Google Scholar]

- Tate DC, Van Den Berg JJ, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Race, social support, and coping strategies among HIV- positive gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2006;8(3):235–249. doi: 10.1080/13691050600761268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jayakody R, Levin JS. Black and white differences in religious participation: A multisample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1996;35:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress, coping and social support processes: Where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;(Extra Issue):53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Stress and health major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(1 suppl):S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Papachristos AV. From social networks to health: Durkheim after the turn of the millennium. Social Science & Medicine. 2015;125:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Understanding the links between social support and physical health: A lifespan perspective with emphasis on the separability of perceived and received support. Perspectives in Psychological Science. 2009;4:236–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K. Sexual orientation and psychological distress in adolescence: Examining interpersonal stressors and social support processes. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2005;68:258–277. [Google Scholar]

- Weston K. Families We Choose. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Vaux A. Variations in social support associated with gender, ethnicity, and age. Journal of Social issues. 1985;41(1):89–110. [Google Scholar]

- de Vries B. Introduction to special issue sexuality and aging: A late-blooming relationship. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2009;6(4):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. White normativity: The cultural dimensions of whiteness in a racially diverse LGBT organization. Sociological Perspectives. 2008;51(3):563–586. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BDM, Harper G. Race and ethnicity in lesbian, gay and bisexual communities. In: Patterson CJ, D'Augelli AR, editors. Handbook of Psychology and Sexual Orientation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 281–308. [Google Scholar]