Abstract

The current study evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of a manualized Impact of Crime (IOC) group intervention implemented with male inmates (N = 108) at a county jail. Facilitator adherence to the intervention and participant attendance, homework completion, and feedback were assessed. On average facilitators covered 93.7% of each manual topic. Victim speaker recruitment was a challenge—43.5% of relevant sessions lacked victim speakers. Findings suggested significant participant engagement—67.3% attended at least 75% of sessions and 93.3% of homework assignments were submitted on time. Overall, participants indicated satisfaction with the intervention. Successful strategies, challenges, and potential enhancements are discussed.

Keywords: intervention, offenders, rehabilitation, restorative justice, reintegration

Victim impact group interventions represent a creative application of restorative justice principles. Such groups aim to reduce recidivism among inmates by enhancing a sense of belongingness to the community and awareness of the impact of crime on victims and communities via direct interaction with victims of crime (Monahan, Monahan, Gaboury, & Niesyn, 2004). In recent years, various victim impact interventions have been developed for use in jails and prisons (e.g., Impact of Crime; Listen and Learn, National Institute of Corrections, 2009); Victim Offender Institutional Correctional Education System (VOICES), Connecticut Department of Corrections, 1997). A 2004 National Institute of Corrections survey found that 73% of state correctional departments in the United States (n = 35) were using “victim impact education/empathy” programming (National Institute of Corrections, 2004; p. 10). Though victim impact interventions appear to be offered in many correctional institutions across the United States, we were unable to find empirical reports regarding the feasibility and acceptability of such interventions implemented in the United States.1

Issues of both feasibility and acceptability are especially relevant to victim impact interventions. For example, regarding feasibility, in addition to the challenges associated with conventional correctional programs, victim impact interventions typically require recruitment and involvement of victim volunteer speakers (McMahon, 2003; Muth, 1999). Regarding acceptability, victim impact interventions by design aim to evoke empathy for victims and associated feelings of guilt for the harm caused by one’s crime. There remains the possibility, however, that inmate participants may become inadvertently shamed when faced with repeated vivid reminders of the harm they have caused, leading to voluntary termination of treatment (Jackson & Bonacker, 2006).

In this paper, we present data on the feasibility and acceptability of a victim impact manualized group intervention delivered in an urban county jail setting. Sentenced male inmates (N = 108) were randomly assigned to participate in the intervention as part of a randomized clinical trial.

Restorative Justice

Restorative justice theory adopts a different perspective than retributive justice, the punishment-focused approach that has dominated the criminal justice system in the United States and many other places around the world for a long time (Tyler, 2006). Rather than focusing on crime as a violation of the law, legal processes, and punishment of the offender, restorative justice theory emphasizes the ways in which crime harms individuals and the community, while also promoting accountability and repair (Ellsworth & Gross, 1994; Garland, 2001). Crime is viewed as a violation of the victim and the community rather than the state and offenders are encouraged to take responsibility for their actions and repair harm through restitution, competency development, and community service (Braithwaite, 1989, 2002; Cohen, 1985).

Shame, Guilt, and Restorative Justice

Braithwaite’s (1989, 2000) influential work on restorative justice and “reintegrative shaming” provides a strong theoretical argument for considering the emotions of guilt and shame in work with offender populations, especially for victim impact interventions. (Braithwaite distinguishes between “reintegrative” shame and “disintegrative” shame, which in many ways parallels psychologists’ distinction between guilt and shame). When participating in restorative justice-based interventions, offenders are encouraged to take responsibility for their behavior and feel guilt for having done wrong. Consequently, they are prompted to acknowledge the negative effects of crime on others, empathize with the distress of their victims, and act on the resulting inclination to repair the harm done (for a review see Tangney, Stuewig, & Hafez, 2011).

Restorative justice interventions aim to counter messages that humiliate and condemn offenders as “bad people,” discouraging participants from feeling “disintegrative” shame about themselves (Braithwaite, 2002). This aim of discouraging shame may be particularly important given shamed people often resort to defensive tactics, seeking to hide or escape these feelings by denying responsibility (for a review see Tangney et al., 2011). They often shift blame onto others and may become irrationally angry, sometimes engaging in overtly aggressive and destructive actions. Consequently, shamed individuals are no less likely to repeat their transgressions and they are no more likely to attempt reparation. Individuals who experience guilt, however, are more likely to recognize harm, feel empathy, and take reparative action (Barnett & Mann 2013; Marshall, Serran, & O’Brien, 2009).

In practice, it is a delicate balance – providing structured experiences to induce empathy for victims and guilt about behaviors without prompting shame about the self. Participants in victim impact interventions are exposed to a series of speakers who have been directly negatively impacted by crimes and whose aim is partially to encourage offenders to recognize this negative impact and to dissuade them from further criminal behavior. Under the best of circumstances, participants in victim impact interventions are apt to experience substantial negative affect in the form of guilt; under less than optimal circumstances, participants may experience a mix of guilt, shame, or even self-disgust. The degree to which participants are willing to tolerate feelings of moral distress associated with victim impact interventions remains an open question. This is an instance where acceptability from the perspective of participants is especially important to assess.

Current Study

In this report, we present data on the implementation of a manualized Impact of Crime (IOC) intervention (Cosby, Ferssizidis, McGill, Schaefer, & Durbin, 2009a; Cosby, McGill, Ferssizidis, Schaefer, & Durbin, 2009b) in a county jail. The intervention was developed and implemented as part of a collaboration between George Mason University and a local affiliate of Opportunities, Alternatives, & Resources (OAR). The primary measures of interest for the purpose of the current study span two domains (a) feasibility and (b) acceptability. Feasibility, or “practicability” (Proctor et al., 2011, p. 68), of carrying out an IOC intervention in the jail setting, was assessed by facilitator adherence to the developed program manual, the ability to recruit victim speakers for the victim component, and participant program retention. Acceptability, or “satisfaction with various aspects of the innovation” (Proctor et al., 2011), was assessed by in-group participation ratings, completion of homework assignments developed to complement group sessions, and participant feedback (Chaple et al., 2014; Proctor, Landsverk, Aarons, Chambers, Glisson, & Mittman, 2009). To our knowledge this is the first study to examine the feasibility and acceptability of a victim impact intervention at a county jail. A particular emphasis is placed on providing recommendations for facilities intending to implement an IOC intervention.

Method

Impact of Crime (IOC) Intervention Description

Founded in 1971, the non-profit organization Opportunities, Alternatives, and Resources (OAR) provides human services to offenders and their families. As a result of collaboration, a 16 session standardized Impact of Crime (IOC) manual was developed to be delivered over 8 weeks at county jails. Two sessions were delivered each week and each session was designed to last for 90 minutes. Part psycho-educational, part group process, the intervention encourages voluntary participants to examine the ways in which crime impacts victims, families (of both victim and offender), and the community. Participants read news stories and personal vignettes recounting actual crimes and the associated impacts, learn pertinent crime statistics, complete and process workbook exercises, and interact with guest speakers—victims of crime who discuss how crime has affected their lives and those around them. Throughout, the manual emphasizes restorative justice principles (e.g., principles of community, individual accountability, restoration).2

The intervention begins with a three session introduction to the IOC program and restorative justice and victimology principles. Participants are encouraged to contemplate their role as they envision a triangle connecting the offender, the victim(s), and the community. As sessions focus on building understanding of the impact of crime, emphasis is placed on taking personal responsibility and working to repair the harm to the victim and the community. The following ten sessions explore the impact of various types of crime, focusing on accountability and reparation. The crime topics discussed include assault, child maltreatment, domestic violence, drug use and distribution, drunk driving, property crime, robbery, sexual assault, and violent crime. Community members who have been victims of these crimes are guest speakers during the relevant sessions. The intervention culminates with a group community service project, completed during three sessions, and a graduation ceremony. For example, one group designed and marketed a t-shirt with a message about the effects of domestic violence on families. The group donated the sales proceeds to the local domestic violence shelter where one of the victim speakers stayed after leaving her abusive husband. Other examples of community services projects conducted by groups of participants during the current study included creating a poster depicting the consequences of a life of crime vs. education that was displayed in an alternative high school to encourage students to think before they act, and writing a letter to the local member of congress providing research on the impact of drunk driving and asking for a bill that would make interlock ignition devices standard in all United States cars within the next five years to prevent drunk driving casualties.

Recruitment

Male inmates were invited to participate in a longitudinal randomized control trial. Participants were randomly assigned to receive (1) a one-session motivational interview followed by the 8-week, 16 session Impact of Crime (IOC) intervention, or (2) a one-session motivational interview followed by 8 weeks of treatment as usual (TAU). At the time of recruitment, prospective participants were told, “We will be evaluating some existing and new jail programs designed to help people develop new ways to reach their goals.” Using the following exclusionary criteria, 115 inmates were not randomized into the study: illiteracy, limited English proficiency, moderate to severe mental retardation, severely debilitating psychopathology (e.g., psychosis), inmates with orders to be kept separate from three or more inmates (making group participation impracticable), inmates who were not sentenced, and those who previously participated in the IOC intervention. Recruitment and treatment of nine study cohorts took place between 2009 and 2012. Study cohorts 1–3 had two workshops running simultaneously, whereas study cohorts 4–9 had one. As such, the study included a total of 12 workshops. Workshops ranged in size from 4 to 12 (M = 8.9, SD = 2.8) participants.

Participants

Impact of Crime participants

Of the 213 inmates enrolled in the randomized control trial, 108 male general population inmates were randomized to the Impact of Crime (IOC) intervention. IOC participants were on average 34 years old (SD = 11.5), had completed 12 years of education (SD = 1.8), and were diverse in terms of race and ethnicity (43.0% of participants identified as Black, 38.3% White, 6.5% Latino, 2.8% Asian, and 9.1% identified as “mixed” or “other”).

Impact of Crime facilitators

Over the course of the study, seven facilitators with either a relevant graduate degree (e.g., Master of Arts in Psychology) or a college degree coupled with extensive corrections experience delivered the Impact of Crime (IOC) workshop. Facilitators were 71.4% female, had completed an average of 16.3 years of education (SD = 0.8), and were primarily White (71.4%), with the remaining identifying as Black (28.6%). At the midpoint of their facilitation, facilitators were on average 26.6 years old (SD = 4.8).

All facilitators received training from a senior IOC facilitator that included didactic training, observing at least one IOC workshop, and being observed and receiving feedback on facilitation. In addition, facilitators were all trained to code variables of interest (e.g., fidelity, attendance, participation) using uniform research coding sheets. Each facilitator coded an entire workshop as part of their training to ensure maintenance of adequate interrater reliability.

Treatment Fidelity

To investigate the degree to which the Impact of Crime (IOC) intervention was implemented as intended (i.e., treatment integrity), an adherence measure was developed for each of the 13 topic sessions. Clinicians were not asked to complete adherence ratings for the three community service project sessions. The measure was composed of a detailed list of items specific to each session (e.g., Drunk Driving Session: “As participants gather, pass out a piece of paper to each person and have them write the name of a loved one on the paper. Post the papers around the room and randomly cross out the names during the class period to demonstrate the drunken driving death statistic. Make a reference to the number of decedents at the end of the class.”; Assault Session: “Complete the true/false section on page 13. Review select questions with the participants and explain the answer.”).

To assess treatment fidelity, the primary facilitator and a second clinician independently completed this measure of adherence to the treatment manual for each session. When the second clinicians were not present in the session they reviewed video recordings of the session to complete their ratings. Discrepancies were resolved through discussions between the two raters. Interrater reliability was strong (kappa = 0.86) (Cohen, 1960; McHugh, 2012). Using the final ratings, a measure of treatment adherence was created by dividing the number of items complied with during the group session by the total number of items. These percentages were aggregated across sessions for each workshop. The attendance of victim speakers was also considered an integral part of the IOC intervention. Facilitators recorded the presence or absence of victim speakers for each topic session.

Participants’ Retention and Engagement

Retention

To assess participant retention in treatment, facilitators recorded attendance as present or absent for each session. Total number of sessions attended ranged from 0 to 16.

In-session participation

At the completion of each session, for each participant the facilitator rated level of in group participation on a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 = none, 1 = occasional participation, 2 = moderate participation, 3 = somewhat frequent participation, and 4 = very frequent participation.

Homework completion

Participants were asked to complete homework for each session and the primary facilitators recorded their level of compliance on a 4-point scale, where higher scores indicate greater compliance with expectations (1 = never turned in assignment, 2 = turned in assignment 2 or more classes late, 3 = turned in assignment 1 class late, and 4= turned in assignment on time). Average ratings of homework compliance were taken for each participant.

Participant Acceptance of Treatment

Participants were asked to provide feedback following completion of the 16-session intervention at their post-intervention research interview, which was completed within a week of the final intervention session. Due to a clerical error, the feedback form was only administered to participants in treatment cohorts 3, 4, 5, 6, and 9 (n = 43 participants). Participants recorded their perceptions of the quality of the Impact of Crime (IOC) intervention (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, and 4 = excellent) and their level of satisfaction with the IOC intervention (1 = not at all satisfied, 2 = a little satisfied, 3 = mostly satisfied, and 4 = very satisfied). They also rated how useful they found the IOC intervention, homework assignments, and community service projects (1 = not at all useful, 2 = a little useful, 3 = somewhat useful, and 4 = very useful), how important the victim speakers were (1 = not at all important, 2 = a little important, 3 = somewhat important, 4 = very important), and how meaningful they found the community service project (1 = not at all meaningful, 2 = a little meaningful, 3 = somewhat meaningful, and 4 = very meaningful).

Open-ended questions were also used to illicit information about the IOC experience from the viewpoints of participants. Participants were asked “What was most useful about the IOC experience?” and “What was least useful about the IOC experience?”

Results

Treatment Fidelity

Facilitators and independent clinicians rated adherence to the workshop manual for each session using a checklist designed specifically for each topic session (e.g., domestic violence, drugs). On average, across cohorts facilitators covered 93.7% of the manual material (SD = 9.1%). Specific adherence to each of the 13 topic sessions is shown in Table 1. Of the sessions on specific crime topics, drunk driving (96.7%) and domestic violence (97.3%) showed the highest adherence ratings overall; robbery (87.5%) and drugs (88.9%) were lower in adherence, but still adequate. With regard to adherence to the victim speaker portion of the intervention, across sessions speakers were present at an average of 56.2% (SD = 16.1%, range = 22.0–89.0) of the sessions scheduled for this element. Table 1 shows adherence by topic area to the victim speaker portion of the intervention. Victim speakers were present at most drunk driving sessions (72.7%) and sessions on violent crime (83.3%). In contrast, the drug crimes (25.0%) and robbery (25.0%) sessions had the fewest speakers across workshops.

Table 1.

Adherence to Course Content

| Adherence | Speakers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Topic | M | SD | Min-Max | % of Sessions |

| Orientation | 100.0% | 0.0% | 100.0%–100.0% | - |

| Restorative Justice | 94.5% | 7.2% | 86.0%–100.0% | - |

| Victimology | 95.0% | 8.1% | 83.0%–100.0% | - |

| Assault | 88.9% | 14.7% | 56.0%–100.0% | 66.7% |

| Child Maltreatment | 94.0% | 8.4% | 80.0%–100.0% | 41.7% |

| Drugs | 88.9% | 3.1% | 80.0%–90.0% | 25.0% |

| Drunk Driving | 96.7% | 5.0% | 90.0%–100.0% | 72.7% |

| Domestic Violence | 97.3% | 4.4% | 91.0%–100.0% | 66.7% |

| Property Crime | 93.6% | 5.6% | 89.0%–100.0% | 66.7% |

| Robbery | 87.5% | 8.3% | 75.0%–100.0% | 25.0% |

| Sexual Assault | 92.5% | 8.3% | 75.0%–100.0% | 63.6% |

| Violent Crime | 92.9% | 18.1% | 43.0%–100.0% | 83.3% |

| Graduation | 97.8% | 6.7% | 80.0%–100.0% | - |

Note. n of sessions = 13; the community service project sessions (n = 3) did not include adherence checklists or victim speakers.

Participants’ Retention and Engagement

Retention

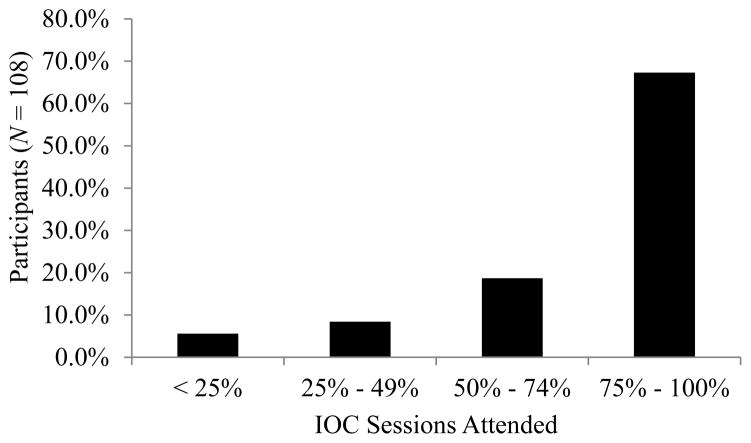

Figure 1 shows the attendance records of the 108 participants. Overall, 28% of the participants attended 100% of the 16 sessions comprising the intervention; 67.3% attended at least 75% of the sessions. Of the total number of participants, reasons for not attending at least 75% of the sessions were: transfer (0.9%), early release (6.5%), schedule conflicts (6.5%), withdrawal from the workshop (3.7%), and unknown/no documentation available (14.8%).

Figure 1.

Participant Attendance

In-session participation

On average across all sessions, facilitators rated participants as participating in session a moderate amount (M = 2.31, SD = 1.02).

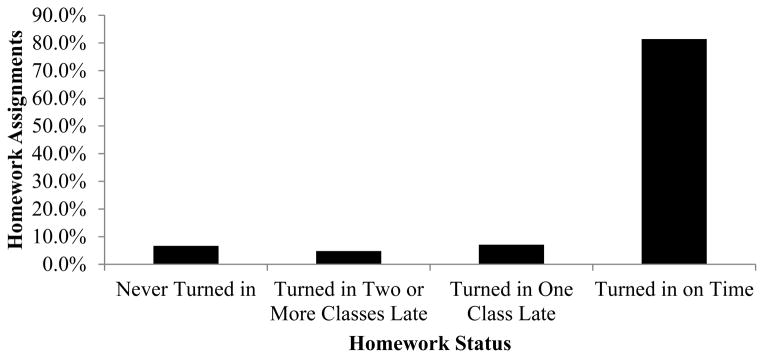

Homework completion

Participants turned in 81.4% of homework assignments on time. Of the remaining assignments, 7.1% were turned in one session late, 4.8% were turned in 2 or more sessions late, and 6.7% were never turned in (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Homework Completion

Participant Acceptance of Treatment

Of the 43 participants who received feedback forms (100% completed them), 58.1% rated the quality of the Impact of Crime (IOC) intervention as excellent, 39.5% rated the quality as good, 2.3% fair, and 0.0% poor. When asked how useful they found the intervention, 58.1% of the participants rated the intervention as very useful, 30.2% rated it as somewhat useful, 11.6% rated the intervention as a little useful, and 0.0% rated it as not at all useful. Participants reported high levels of satisfaction with the IOC intervention—76.2% were very satisfied with the intervention, 19.0% mostly satisfied, 4.8% a little satisfied, and 0.0% not at all satisfied.

Participants were also asked to comment on specific components of the IOC intervention. When asked how useful homework assignments were, 52.4% of participants rated the homework portion of the intervention as very useful, 33.3% said it was somewhat useful, 9.5% said it was a little useful, and 4.8% said it was not at all useful. The feedback form also contained a question asking participants about the community service project. Participants in earlier cohorts were asked how useful the community service project was and participants in later cohorts were asked how meaningful it was. Of the 14 participants who rated the usefulness of the community service project, 57.1% said it was very useful, 28.6% said it was somewhat useful, 7.1% said it was a little useful, and 7.1% said it was not at all useful. Of the 21 participants who rated the meaningfulness of the community service project, 61.9% said it was very meaningful, 19.0% said it was somewhat meaningful, 14.3% said it was a little meaningful, and 4.8% said it was not at all meaningful. Moreover, a question was added to the feedback form for later cohorts to assess how important the victim speakers were to the overall intervention effectiveness. Of the 26 participants who responded to this question, 96.2% believed that the victim speakers were very important, 3.8% said it was somewhat important, and 0.0% of the participants said it was a little or not at all important.

Thematic analyses (Braun & Clarke, 2006) were conducted on responses to open-ended questions from the feedback form to identify overall themes about the IOC experience from the viewpoints of participants (n = 39) (see Table 2). Two sets of thematic analyses were conducted on participants’ responses to (a) what was most useful about the IOC experience? and (b) what was least useful about the IOC experience? Thematic analyses followed the procedure outlined in Braun and Clark (2006). Consistent with the exploratory nature of these questions, each analysis was inductive (i.e., data-driven as opposed to deductive or theory driven).

Table 2.

Feedback about the Impact of Crime Experience

| Theme | Prevalence |

|---|---|

| Most useful about the IOC experience (N = 39) | |

| Victim involvement | 51.3% (n = 20) |

| Knowledge | 35.9% (n = 14) |

| Restorative justice principles | 12.8% (n = 5) |

| Least useful about the IOC experience (N = 39) | |

| Homework | 10.3% (n = 4) |

| Negative group members | 5.1% (n = 2) |

| “None” or “Nothing” | 74.4% (n = 29) |

Note. Summing individual themes will not equal the total number of respondents because some themes had one respondent and therefore were not included as an overarching theme for the thematic analysis.

Most Useful About the IOC Experience

Three themes were identified from participants’ responses. A description of each theme follows. Themes are described in order of prevalence, with the more prevalent themes described first.

Victim involvement. The majority of participants (51.3% of the 39 respondents) wrote that the victim speakers were the most important part of the IOC experience. Some participants simply wrote “victim speakers.” Other respondents provided more detail, for example one respondent wrote, “Guest speakers. Being able to hear and connect with their emotions.”

Knowledge. Participants noted that the knowledge provided through the material making up the intervention was the most useful aspect of the intervention. For example, one participant wrote that the “instructor’s notes” were most useful. Another participant wrote “understanding what IOC meant.”

Impact of crime. Participants noted that the experience provided an understanding about how crime impacts themselves, the community, their family, and victims. To illustrate, one participant wrote, “Helped me see my role in crimes and the impacts on me, my family, and the community.”

Least Useful About the IOC Experience

From the 39 respondents, an overwhelming amount (n = 29) wrote “none” or “nothing.” From the responses of participants who provided specific responses, 2 themes were identified. A description of each theme follows. Again, themes are described in order of prevalence, with the more prevalent themes described first.

Homework. The homework did not significantly contribute to some participants’ overall IOC experience as compared to other aspects of the program. It appeared that participants merely did not enjoy having assignments. For example, one participant wrote “having to do homework.”

Negative group members. Several participants perceived that one or more of their group members were attending the intervention for “the wrong reasons” or were disruptive. To illustrate, one group member wrote “inappropriate comments of other group members.”

Discussion

This study represents the first feasibility and acceptability assessment of an Impact of Crime group intervention implemented at a county jail. An Impact of Crime (IOC) manual was developed and the feasibility and acceptance of the program was evaluated. The feasibility assessment demonstrated that the intervention could be delivered with fidelity to male adults sentenced to a period of incarceration at a county jail. The manualized intervention was perceived as acceptable to participants. We also identified a number of modifications that might enhance the implementation of the intervention in a jail setting.

Feasibility: Fidelity, Recruitment of Victim Speakers, and Retention in a Jail Setting

Based on fidelity ratings, facilitators largely adhered to the Impact of Crime manual across topic sessions. One exception was the ranges of adherence ratings for the assault and violent crime sessions that were larger than any other sessions. One possible reason for the variation in adherence to the manual for these two modules could be that workshops in this study were most likely to have speakers for these sessions. As a result, facilitators likely left a large portion of the assault and violent crime sessions for the victim speaker, leaving less time in session to cover material from the manual. Allowing time for debriefing and interaction between participants and the speakers is an integral part of the Impact of Crime (IOC) intervention. A review of audiovisual recordings indicated that managing sessions to allow ample time to debrief and process the material covered by the speaker in addition to covering the manual material may have been challenging for some facilitators. As such, facilitators would likely benefit from supervision specifically targeting group facilitation and time management. In addition, due to the large variability in the number of victim speakers across topic areas, facilitators would likely benefit from engaging in more targeted recruitment strategies as discussed in the logistical considerations section below.

Findings from this study showed that over two-thirds of participants attended at least 75% of sessions. This is higher than expected in a transient jail setting (Tangney, Mashek, & Stuewig, 2007) and is likely a function of several factors. First, and perhaps most important, the recruitment method focused on post-sentencing inmates. Since movement in and out of jails is highly variable and often unpredictable, particularly among pre-trial and pre-sentence inmates, recruitment was limited to post-sentencing inmates in an effort to ensure participants would be incarcerated at the jail long enough to complete the intervention. Of note, these retention results stand in contrast to those experienced prior to the initiation of the study, when program staff followed standard practice, focusing recruitment efforts on newly arriving, often pretrial, inmates. Of the 722 inmates enrolled in 38 IOC groups during the 5 years prior to the initiation of the study, 38% attended at least 75% of the sessions. Although this may be due to other factors in addition to recruitment strategy (e.g., institutional policy change, differing participant demographics), the differences in retention before and after these recruitment modifications are striking.

A second factor that may have enhanced retention is the motivational interview provided to participants in both the IOC and TAU groups. Participants received a one-session motivational interview focused on personalized behavior change prior to initiation of the IOC group intervention which, although not specific to IOC content, may have enhanced motivation for treatment in general. Finally, a third key factor relevant to treatment retention is participants’ perceived acceptability of the program.

Acceptability: Participation, Homework Completion, and Participant Feedback

To assess acceptability a range of measures were used in order to not only capture participant satisfaction (e.g., feedback), but also participant willingness to engage in the components of the intervention (e.g., complete homework assignments). Facilitator ratings indicated that participants were engaged in the program both during and between workshop sessions. In general, facilitators reported that inmates participated at a moderate level during workshop sessions. A more objective measure of participant engagement is the extent that participants completed voluntary homework assignments (Safran & Segal, 1990). The majority of assignments were turned in on time, possibly indicating that participants bought into, and agreed with, the goals and tasks of the program (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989). Although most discussion about the role of homework in treatment with offender populations is theoretically based, the general psychotherapy literature shows that homework completion in treatment is related to positive outcomes. For example, homework completion is associated with sustained reduction in symptoms for a variety of mental health concerns (Abramowitz, Franklin, Zoellner, & DiBernardo, 2002; Edelman & Chambless, 1993) and reductions in substance abuse post-treatment (Gonzalez, Schmitz, & DeLaune, 2006). Future research may consider the association between homework assignments and the acceptability and effectiveness of IOC interventions specifically.

Feedback provided by participants also afforded some insight into which components of the intervention were most useful from their perspective. Results from the thematic analysis of participant feedback forms showed that they perceived speakers as the most useful component of the IOC intervention. These findings were consistent with a prior study that surveyed county jail inmates about their perceptions of a different IOC intervention (McMahon, 2003). It may be that the opportunity to hear victims speak about their own experiences and the ability to engage in dialogue with victims is perceived as having more impact than the less personal, and potentially less engaging, approaches of listening to lectures or watching videos about crime. For example, one participant wrote that the victim speakers were most useful “because you see what they feel and think more.” This positive response is encouraging given the possibility for participants to experience aversive feelings such as shame and guilt after listening to multiple victim speakers emphasizing the costs of crime and predominately negative impact on their lives.

Given the participants’ enthusiastic response to victim speakers, it is especially notable that IOC facilitators struggled in their efforts to recruit victim speakers. Despite considerable sustained efforts, only about half of sessions for which speakers were prescribed as part of the curriculum actually used speakers. Issues regarding recruitment of speakers are discussed in the logistical considerations section below.

In contrast to the positive response to victim speakers, ratings of homework and the importance of the community service project were not as favorable. Although completion of homework may be beneficial to the treatment, not all participants particularly enjoyed it. For some, homework assignments may call to mind negative school experiences, as many incarcerated individuals have a history of learning disabilities and school failure. These findings suggest that when programs include homework assignments, facilitators should be sensitive to potential responsivity issues (Andrews & Bonta, 2010).

With regard to the community service projects, the types of projects participants were able to engage in were limited by the security constraints of the correctional environment. For example, inmates were not able to directly see the impact of their community service project on recipients. The fact that they perceived this portion of the intervention to be less meaningful may be related to the limitations encountered when attempting to implement a restorative justice-based intervention in an environment where security is a priority. Perhaps a member of the community could visit the group to discuss the project’s impact, so participants can see how their giving back to the community had a positive effect.

Logistical Considerations

A primary logistical challenge in the current study was the recruitment of victim speakers. Despite the location of the jail, in a highly populated county just outside of the District of Columbia, it proved challenging for facilitators to recruit speakers for all topic areas as prescribed in the IOC manual. In this study, drug crimes and robbery crimes were the topics with the fewest number of speakers. It might be that it is difficult to isolate drug and robbery crime victimization from associated types of crime (e.g., domestic violence, assault, driving under the influence). Despite difficulty with victim recruitment in this study, given participants’ high ratings of the importance of speakers to this IOC workshop and those studied at other county jails (McMahon, 2003), recruitment of speakers for IOC interventions should be of high priority.

In the current study, recruitment efforts included contacting Sexual Assault Services, posting advertisements on Craigslist, university listserves, local free newspapers, and volunteer websites, hanging flyers at victim service agencies and around university campuses, and networking through personal contacts. Although not utilized in this study, one participant noted on his feedback form that many of the IOC participants had their own histories of victimization. He suggested graduates of the IOC program could be recruited as victim speakers. Unfortunately, correctional institutions place strict limits on who can enter a correctional facility and having a prior criminal record, particularly a recent one, is often a disqualifying factor. One alternative option is the use of the National Institute of Justice’s video clips of victim speakers from their web-based impact of crime program. Future research is needed to explicitly examine (a) participants’ assessments of the importance of pre-recorded interviews, and (b) the relative efficacy of live as opposed to pre-recorded victim speakers.

Results from this study suggest that for restorative justice-based interventions, targeted victim recruitment strategies are necessary to assure proper implementation of the interventions. As restorative justice interventions become more widely used with justice involved individuals, future research is needed to inform best practices for recruitment of victims and victim involvement in restorative justice interventions. For example, one county jail reimbursed victims for their travel (McMahon, 2003); future research could evaluate whether reimbursement for travel improves victim participation in IOC interventions.

Although encouragingly high, an additional barrier to feasibility is participant retention. In the jail environment, movement of inmates is often unpredictable to practitioners. Many inmates are transferred to other facilities, released early, or experience variable work schedules, all of which can impact their attendance in a workshop such as IOC. During the current IOC implementation, we anticipated transfers of inmates between the county jail’s two branches: the Adult Detention Center (ADC) and the Alternative Incarceration Branch (AIB). The latter facility houses inmates who participate in the work release or residential substance abuse treatment programs. As such, for study cohorts 1–3, IOC was implemented simultaneously in the two facilities to provide continuity in treatment for inmates who were transferred between the two facilities. This system, however, turned out to be impracticable. Transfers between the two facilities were not as common as we had anticipated, and the schedules of inmates in the AIB changed frequently, making it difficult to maintain scheduled sessions that all participants could attend. Concurrently running workshops was ceased after the third cohort in the current study as a result. Although this system was not entirely beneficial in the current study, it may be useful in facilities where transfers between branches of the jail are more common and work schedules are more predictable. In addition, given most jail inmates have relatively brief incarcerations, a post-release follow-up or aftercare program that continues to reinforce the principles from the IOC workshop could be a helpful addition to community-based reentry programs seeking to support the reentry process.

Lastly, it was challenging to maintain a set of qualified facilitators with sufficient group-based intervention skills through the randomized clinical trial. At the beginning of the trial, doctoral students in clinical psychology acted as facilitators. Midway through the trial, however, due to a bureaucratic barrier, it was no longer possible for the subcontractor providing treatment to hire clinical doctoral students. Turnover was at times high, and there was more variability in facilitators’ clinical skills. This may influence the program’s effectiveness and will be important to consider in subsequent analyses.

Limitations

It is important to note that while this feasibility study showed it is possible to facilitate an Impact of Crime workshop at a county jail, the study was conducted within one county. Other counties may encounter different feasibility concerns when implementing this intervention.

A limitation of the current study is the underutilization of participant feedback forms. This was, however, due to a non-systematic clerical error on the part of the research team, and was not influenced by facilitator bias. As such, they are likely representative of the larger sample of participants. In addition, the acceptability of the intervention was also based upon workshop attendance, in-session participation, and the amount of homework completed by participants. Although the proportion of sessions attended, moderate levels of in-session participation, and amount of homework completed on time would suggest that participants perceived the intervention as acceptable, having additional feedback forms might have provided further details about the acceptability of the intervention.

Lastly, reasons for participant non-completion of the intervention were not systematically recorded in some cohorts. Although reasons for treatment non-completion for many participants were available from jail records and from notes of facilitators, it would have been useful to systematically record reasons for non-completion to further inform issues of feasibility and acceptability.

Conclusions

The focus of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of an Impact of Crime workshop at a county jail. In the current study, facilitators largely adhered to the IOC manual and participants were engaged in and accepting of the intervention. Participants’ levels engagement and acceptability were particularly encouraging given the potential for them to experience aversive emotions such as shame and guilt while developing an enhanced awareness of the negative impact of crime on victims and communities. Although challenges such as recruitment of victim speakers did influence delivery of the intervention, participant engagement was still encouragingly high. On one hand, the setting is particularly challenging; county jails can be chaotic with inmates cycling in and out. On the other hand, some inmates are sentenced to short periods of incarceration, which presents an opportunity to engage them in a short intervention in a setting where programming is often not provided. Nonetheless, in line with restorative justice principles, administering interventions with high fidelity, integrity, and acceptability in county jail settings is an important step in helping individuals repair the harm they have done to themselves, their victims, and the community.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant # RO1 DA14694 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Many thanks to the members of the Human Emotions Research Lab for their assistance with this research.

Footnotes

In one non-U.S. study, conducted in London, qualitative interviews with staff and offender participants were used to assess the acceptability of a victim impact intervention called The Forgiveness Project (Adler & Mir, 2012). Both prison staff and offender participants were largely positive in their discussions of the program.

The three principles considered fundamental restorative justice are: 1) crime arises out of conflict and harms victims, communities, and offenders; 2) criminal justice processes should seek to repair harm through reconciliation; and 3) victims, offenders, their families, and communities should all be actively involved in repairing the harm and resolving conflict brought about through crime (Hudson & Galaway, 1996). The Impact of Crime workshop in the current study primarily focuses on the first two principles. The curriculum is designed to encourage offenders to recognize the impact of their crimes and a community service project is conducted at the end of the workshop as a way to begin repairing harm done to the community. Although the participants are not directly repairing the harm their crime caused, they are taking steps toward reconciliation with the community. In regard to the third principle, although victims are involved in the intervention by speaking to the offenders during the workshop, the victims are not the ones directly affected by the crimes of the group members and they do not share in the reconciliatory process.

References

- Abramowitz JS, Franklin ME, Zoellner LA, DiBernardo CL. Treatment compliance and outcome in obsessive– compulsive disorder. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:447–463. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026004001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler JR, Mir M. Project Report. Forensic Psychological Services at Middlesex University; London, UK: 2012. Evaluation of The Forgiveness Project within prisons. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews DA, Bonta J. The psychology of criminal conduct. New Providence, NJ: Matthew Bender & Company; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett GD, Mann RE. Cognition, empathy, and sexual offending. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2013;14:22–33. doi: 10.1177/1524838012467857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite J. Crime, shame and reintegration. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite J. Shame and criminal justice. Canadian Journal of Criminology. 2000;42:281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite J. Setting standards for restorative justice. British Journal of Criminology. 2002;42:563–577. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chaple M, Sacks S, McKendrick K, Marsch LA, Belenko S, Leukefeld C, French M. Feasibility of computerized intervention for offenders with substance use disorders: A research note. Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2014;10:105–127. doi: 10.1007/s11292-013-9187-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Visions of social control: Crime, punishment and classification. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut Department of Corrections. Program Manual developed by the Connecticut Department of Correction. 1997. Victim Offender Institutional Correctional Education System; VOICES. [Google Scholar]

- Cosby B, Ferssizidis P, McGill LA, Schaefer KE, Durbin K. Instructor manual for the Impact of Crime program. Fairfax, VA: Opportunities, Alternatives, and Resources (OAR) of Fairfax County; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cosby B, McGill LA, Ferssizidis P, Schaefer KE, Durbin K. Client workbook for the Impact of Crime program. Fairfax, VA: Opportunities, Alternatives, and Resources (OAR) of Fairfax County; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Edelman RE, Chambless DL. Compliance during sessions and homework in exposure-based treatment of agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1993;31:767–773. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90007-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth PC, Gross SR. Hardening of the attitudes: Americans’ views on the death penalty. Journal of Social Issues. 1994;50:19–52. [Google Scholar]

- Garland D. The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez VM, Schmitz JM, DeLaune KA. The Role of homework in cognitive behavioral therapy for cocaine dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:633–637. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath AO, Greenberg LS. Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36:223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson J, Galaway B. In: Elements of a restorative justice approach. Galaway B, Hudson J, editors. Amsterdam: Kugler Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AL, Bonacker N. The effect of victim impact training programs on the development of guilt, shame and empathy among offenders. International Review of Victimology. 2006;13:301–324. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WL, Marshall LE, Serran GA, O’Brien MD. Self-esteem, shame, cognitive distortions and empathy in sexual offenders: Their integration and treatment implications. Psychology, Crime & Law. 2009;15:217–234. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia medica. 2012;22:276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon ME. The Impact of Crime Program in a jail setting. Corrections Today. 2003;65:86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan LH, Monahan JJ, Gaboury MT, Niesyn PA. Victims’ voices in the correctional setting: Cognitive gains in an offender education program. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2004;39:21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Muth WR. Victim impact programs in the federal prison system. Journal of Correctional Education. 1999;50:62–66. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Corrections. Corrections-based services for victims of crime. US Department of Justice, Office for Victims of Crime; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Corrections. Listen and Learn facilitator manual and participant workbook. US Department of Justice, Office for Victims of Crime; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36:24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Research. 2011;38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran JD, Segal ZV. Interpersonal process in cognitive therapy. New York: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Mashek D, Stuewig J. Working at the social-clinical-community-criminology interface: The GMU Inmate Study. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26:1–21. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2007.26.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Hafez L. Shame, guilt, and remorse: Implications for offender populations. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2011;22:706–723. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2011.617541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TR. Why people obey the law. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]