Abstract

Objectives

Hepatic arterial (HA) and portal venous (PV) complications of recipients after living donor liver transplantation(LDLT) result in patient loss. The aim of this study was to analyze these complications.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed HA and/or PV complications in 213 of 222 recipients underwent LDLT in our centre. The overall male/female and adult/pediatric ratios were 183/30 and 186/27 respectively.

Results

The overall incidence of HA and/or PV complications was 19.7% (n = 42), while adult and pediatric complications were 18.3% (n = 39) and 1.4% (n = 3) respectively. However early (<1month) and late (>1month) complications were 9.4% (n = 20) and 10.3% (n = 22) respectively. Individually HA problems (HA stenosis, HA thrombosis, injury and arterial steal syndrome) 15% (n = 32), PV problems (PV thrombosis and PV stenosis) 2.8% (n = 6) and simultaneous HA and PV problems 1.9% (n = 4). 40/42 of complications were managed by angiography (n = 18), surgery (n = 10) or medically (Anticoagulant and/or thrombolytic) (n = 12) where successful treatment occurred in 18 patients. 13/42 (31%) of patients died as a direct result of these complications. Preoperative PVT was significant predictor of these complications in univariate analysis. The 6-month, 1-, 3-, 5- 7- and 10-year survival rates in patients were 65.3%, 61.5%, 55.9%, 55.4%, 54.5% and 54.5% respectively.

Conclusion

HA and/or PV complications specially early ones lead to significant poor outcome after LDLT, so proper dealing with the risk factors like pre LT PVT (I.e. More intensive anticoagulation therapy) and the effective management of these complications are mandatory for improving outcome.

Keywords: Living donor liver transplantation, Hepatic artery complications, Portal vein complications, Survival

Highlights

-

•

Preoperative PVT was significant predictor of HA and/or PV complications.

-

•

HA and/or PV complications especially early ones lead to significant poor outcome.

-

•

Proper dealing with the risk factors like pre LT PVT improves outcome.

-

•

The effective management of these complications is mandatory for improving outcome.

List of abbreviations

- ABO

Blood group

- ALT

Alanine transaminase

- ASS

Arterial steel syndrome

- AST

Aspartate transaminase

- BA

Biliary atresia

- BCS

Budd chiari syndrome

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CNIs

CalciNeurin Inhibitors

- CSA

CycloSporine

- CTA

Computed tomography angiography

- CUSA

Cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- ESLD

End stage liver disease

- FK or FK-506

Tacrolimus

- GDA

Gastroduodenal artery

- GRWR

Graft Recipient Weight Ratio

- HA

Hepatic artery

- HAI

Hepatic artery injury

- HAS

Hepatic artery stenosis

- HAT

Hepatic artery thrombosis

- HBV

Hepatitis B virus

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HPB

Hepatopancreatobiliary

- HTK

Hydroxy tryptophan ketoglutarate

- HTN

Hypertension

- HVT

Hepatic vein thrombosis

- IRB

Institutional review board

- LDLT

Living donor liver transplantation

- LFT

Liver function test

- LRDT

Living related donor transplantation

- LT

Liver Transplantation

- MELD

Model for End stage Liver Disease

- MHV

Middle hepatic vein

- MMF

Mycophenolate MoFetil

- MRA

Magnetic resonance angiography

- MRCP

Magnetic resonance cholangio pancreatography

- NLI

National Liver Institute

- OLT

Orthotopic liver transplantation

- PELD

Pediatric end stage liver disease

- PBC

Primary biliary cirrhosis

- POD

Post operative day

- PSC

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- PV

Portal vein

- PVS

Portal vein stenosis

- PVT

Portal vein thrombosis

- SFSS

Small for size syndrome

- SRL

SiroLomus

- VC

Vascular complications

1. Introduction

Liver transplantation (LT) has become the treatment of choice for pediatric and adult patients with end-stage liver disease (ESLD) [1], [2]. However vascular problems such as thrombosis and stenosis of the HA and PV are serious complications after LT and are more frequently seen among recipients of LDLT especially in pediatrics [3], [4], [5], [6]. They can lead to increased morbidity, graft loss, and patient death [2], [3], [7].

The incidence of vascular complications (VC) reported in the literature varies widely among centers [8]. It is as high as 25%, 16%, and 11% for HAT, PVT, and HAS, respectively with higher pediatric rates [9]. Various factors contributing to development of vascular thrombosis have been proposed: ABO incompatibility [4], [10], [11], [12], [13], multiple anastomoses [11], prolonged cold ischemic time [14], acute rejection. [4], [10], [11], [12] and previous vascular thrombosis [11].

Early diagnosis and appropriate management of these complications result in longer survival. Close surveillance of all vascular anastomoses using Duplex ultrasonography facilitates early detection and treatment of these complications before irreversible graft failure. Treatment options usually include surgical revascularization, percutaneous thrombolysis, percutaneous angioplasty, retransplantation, or less commonly, a conservative approach [6].

2. Patients and methods

Two hundred twenty two LDLT operations were done between January 2004 and January 2015 in the department of hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgery, national liver institute (NLI), university of Menoufiya, Menoufiya, Egypt, our study included 213 patients after exclusion of cases with data loss. After approval of institutional review board (IRB), we did this retrospective cohort study that analyzed the incidence, risk factors, management and outcome of HA and/or PV complications in adults and pediatrics recipients in the period from the end of 2014 to the end of 2015, where patients were observed from POD 1 until the end of July 2015 or until death of patients with mean follow up period of 30.7 ± 31.2 m, range (0–134 m). The data were collected from our records in the LT unit and written informed consents were obtained from both donors and recipients regarding operations and researches. All donors were >19 years old and the donor work-up included liver function tests (LFT), liver biopsy, ultrasound examination, psychological assessment and CT angiography, along with hepatic volumetric study and vascular reconstructions. The following data were studied:

2.1. Preoperative parameters

Donor's age, gender, body mass index (BMI), donor to recipient relation, recipient age, gender, blood group matching, primary disease, Child Pugh and MELD score (<12 years), PELD score(>12 years), co-morbidity (DM, HTN, …), portal hypertension and previous vascular thromboses (HA, PV and HV).

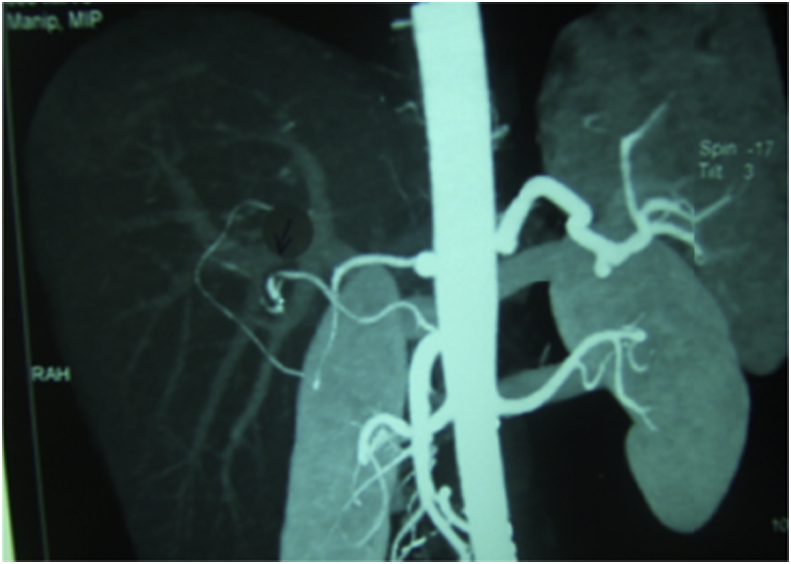

2.2. Intraoperative parameters

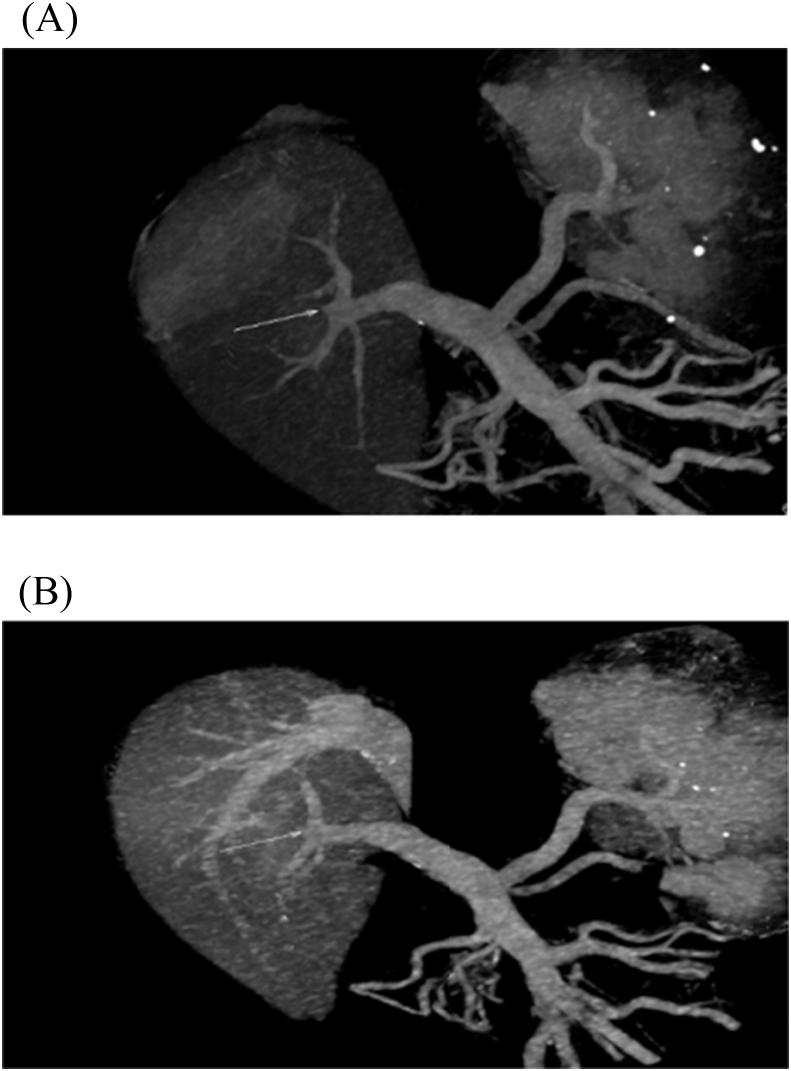

Duration of the operation per hours, actual graft weight, actual graft recipient weight ratio (GRWR), number of arterial, portal and hepatic venous reconstructions Fig. 1, cold and worm ischemia times per minute, blood and plasma transfusion per unit.

Fig. 1.

Trifurcated PV graft where double PV reconstruction with recipient PV was done (complicated by post LT PVT).

Donor operation: The donor operation was performed through a right subcostal incision extended to the upper midline under general anesthesia. Intraoperative cholangiography was used to define the biliary anatomy of donors, the right or left lobes of the liver were mobilized and the vena cava was dissected. The type of liver graft used was dependent on the body build of the recipient and on the calculated segmental volume of the donor liver [15]. The CUSA device was used to divide the liver parenchyma without inflow occlusion. The falciform ligament was reconstructed, the stumps of the divided hepatic and portal veins were closed by continuous non-absorbable sutures, after graft harvesting, it was perfused in the back table with Hydroxy tryptophan ketoglutarate (HTK) solution and weighted to determine the actual GRWR [16].

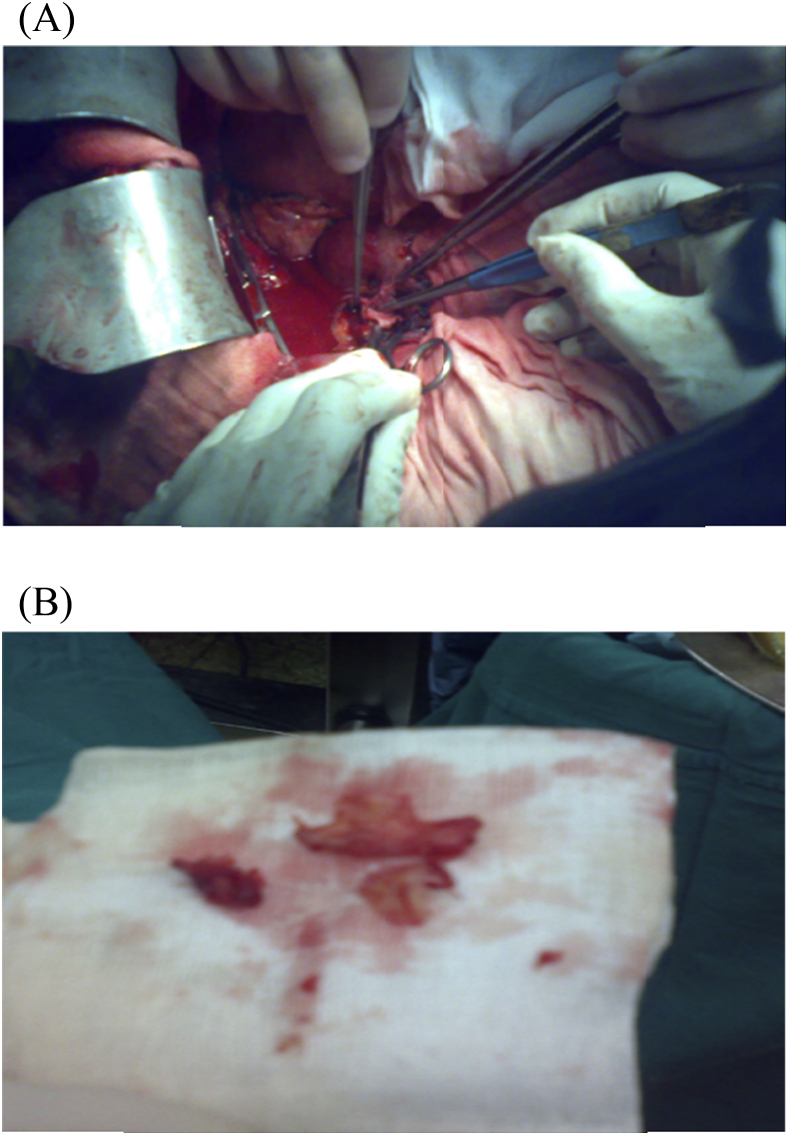

In the recipient surgery: The PV anastomosis was performed after completing hepatic vein (HV) anastomosis with the routine use of about 1 cm growth factor while tying. The anastomosis was done end-to-end using continuous 6/0 prolene suture using 3 loupe magnification. If there was a size discrepancy between the graft PV and the recipient PV, the smaller-sized PV was spatulated from both the anterior and the posterior walls to create a wide anastomosis site. Moreover, in cases with preoperative PVT, thrombectomy was done with or without using vein graft for anastomosis [1], [6], [17], [18], [19], Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4.

Fig. 2.

(A) A patient with preoperative PVT underwent Thrombectomy, (B) The thrombus.

Fig. 3.

Another patient with preoperative PVT underwent eversion Thrombectomy.

Fig. 4.

A patient with preoperative PVT underwent anastomosis of IJV graft to recipient SMV, then the graft was anastomosed to the graft PV.

The HA anastomosis was performed using 6.5 loupe magnification with interrupted 8/0 monofilament Prolene with double needles, which facilitates secure sutures with good intima adaptation. Before performing arterial reconstruction, it was necessary to confirm adequate blood flow by releasing the clamp on the recipient hepatic artery. Both the arteries (graft side and recipient side) were fixed in a microsurgical double-clamp type A-II (Ikuta Microsurgery Instruments, Mizuho, Tokyo, Japan), which had 2 bulldog clamps fitted to a sliding bar. First, the angle sutures were placed at both the edges and tied with 8-0 monofilament (Prolene) sutures. The 8-0 Prolene suture with double needles and a short thread (5 cm) was specially devised for this technique (Bearen WT07F08N15-5; Bear Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Subsequently, the other sutures on the anterior side between the angle sutures were placed and tied. After completion of the anterior wall sutures, posterior wall sutures were performed in the same manner by turning the double clamps. Finally, the double clamps were removed and arterial reperfusion was performed [9], [13], [19], [20], [21].

2.3. Postoperative management

2.3.1. Based on our institutional policy

-

1

Immunosuppression protocols: the standard is combined 3 drugs: calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), steroids and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). Cyclosporine (CsA) was used when neurotoxicity or nephrotoxicity developed with Tacrolimus. When CNIs are contraindicated or their side effects halt their use, sirolimus (SRL) was given at an initial dose of 3 mg/m2 and adjusted over time to achieve blood trough levels of approximately 5–8 ng/mL [22], [23].

-

2

Routine anticoagulant and anti-platelet therapy using Heparin infusion up to 180–200units/kg/day adjusted with reference to the activated clotting time [target levels, 180–200 s] and/or the activated partial thromboplastin time [target levels, 50–70 s]). But when thrombocytopenia occurred, heparin was shifted to clexane 20 mg/12 h, then at POD8 dipyridamole was given at a dose of (4 mg/kg/d) for three months as protocol [24], [25], [26].

-

3

Doppler ultrasonography (For measuring HA resistive index and PV velocity in the liver graft) was routinely performed just after anastomoses and after abdominal closure to ensure vascular patency and twice a day until POD7, and once per day until the patients were discharged from the hospital. Then follow up was done monthly during the 1st 6 months, then every 3 months untill the end of 1st year, then every 6 months untill the end of follow up. While LFTs (mainly AST, ALT, bilirubin) were done once daily untill discharge and then monthly during the 1st 6 months, then every 3 months untill the end of the 1st year, then every 6 months untill the end of follow up. If abnormal serum LFT results were obtained, we performed doppler ultrasonography as soon as possible.

-

4

Diagnosis of HA and/or PV complications: was suspected when the LFT results became abnormal or when doppler ultrasound revealed poor or no blood flow within the hepatic vessels. The complications were confirmed on either computerized tomography angiography (CTA), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or formal conventional angiography as necessary. HA and/or PV complications were defined as early complications when occurring within the first 30 days of LT and as late complications if diagnosed after 30 days of LT.

-

5

Treatment of HA and/or PV complications: Prompt surgical thrombectomy and reconstruction were always our first choice in early cases while angiographic percutaneous thrombectomy and thrombolysis were used in late cases. However, medical treatment was the choice in some cases [11], [27], [27], [28].

2.4. Statistical analysis

All data were tabulated and processed with SPSS software (Statistical Product and Service Solutions, version 21, SSPS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and Windows XP (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA). Qualitative data were expressed in frequency and percentage and analyzed with the chi-square or Fisher exact tests. Quantitative data were expressed as the mean and standard deviation and were compared with the t or Mann-whitney U tests. Comparison between patients with and without HA and/or PV complications was done using Univariate analysis. The Kaplan–Meier method was applied for survival analysis and compared using log-rank tests. In all tests, a P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of patients and their donors

They were classified as 183 (85.9%) males, and 30 (14.1%) females. Their mean age was 40.9 ± 16.3. Patients were classified as 186 adults and 27 children. Their donors were classified as 139 (65.3%) males and 74 (34.7%) females, their mean age and BMI were 27.3 ± 6.4and 25.3 ± 3.4 respectively. The patients were classified according to Child-Pugh score into 19 (8.9%) class A, 67 (31.5%) class B, and 127 (59.6%) class C, their mean MELD and PELD scores were 16 ± 4.2 and 15.2 ± 6.4 respectively. Sixty six (31%) of them had co morbidity, Portal HTN affected 195 (91.6%) of them, while pre operative PVT was found in 27 (12.7%) of patients. The donor to recipient blood group matching was classified into identical in 146 (68.5%) and Compatible in 67 (37.5%) of them. The right lobe, left lobe, left lateral and mono-segment grafts were given to 178 (83.6%), 9 (4.2%), 25 (11.7%) and 1 (0.5%) of them respectively. Concerning vascular anastomoses, single HV, PV, and HA anastomoses were found in 153 (71.8%), 197 (92.5%) and 204 (95.8%) of patients respectively while multiple anastomoses of the HV, PV and HA were 60 (28.2%), 16 (7.5%) and 9 (4.2%) respectively. The mean actual graft weight and GRWR were 759.8 ± 239.04 g and 1.2 ± 0.57 respectively. The mean cold and warm ischemia times were 69.9 ± 46.4 min and 49.9 ± 15.6 min respectively. The mean intra-operative blood and plasma transfusions were 6.03 ± 7and 7 ± 8.3 units respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and their donors.

| Donor age (years) (Mean ± SD) | 27.3 ± 6.4 |

| Recipient age (years) (Mean ± SD) | 40.9 ± 16.3 |

| Recipient age> 18 years | 27 (12.7%) |

| Donor gender | |

| Males | 139 (65.3%) |

| Females | 74 (34.7%) |

| Recipient gender | |

| Males | 183 (85.9%) |

| Females | 30 (14.1%) |

| BMI of donor (Mean ± SD) | 25.3 ± 3.4 |

| Child class | |

| A | 19 (8.9%) |

| B | 67 (31.5%) |

| C | 127 (59.6%) |

| MELD score (<12years) (Mean ± SD) | 16 ± 4.2 |

| PELD score (>12years) (Mean ± SD) | 15.2 ± 6.4 |

| Co morbidity | 66 (31%) |

| Portal HTN | 195 (91.6%) |

| Bl. Group | |

| Compatible | 67 (31.5%) |

| Identical | 146 (68.5%) |

| Preoperative PVT | 27 (12.7%) |

| Graft type | |

| Right lobe | 178 (83.6%) |

| Left lobe | 9 (4.2%) |

| Left lateral | 25 (11.7%) |

| Monosegment | 1 (0.5%) |

| HV anastomosis | |

| Single | 153 (71.8%) |

| Multiple | 60 (28.2%) |

| PV anastomosis | |

| Single | 197 (92.5%) |

| Multiple | 16 (7.5%) |

| HA anastomosis | |

| Single | 204 (95.8%) |

| Multiple | 9 (4.2%) |

| Multiple vascular anastomoses | 76 (35.7%) |

| Actual graft weight (Mean ± SD) | 759.8 ± 239.04 |

| Actual GRWR (Mean ± SD) | 1.2 ± 0.57 |

| Actual GRWR > 0.8 | 20 (9.4%) |

| SFSS | 20 (9.4%) |

| Cold ischemia time (min) (Mean ± SD) | 69.9 ± 46.4 |

| Warm ischemia time (min) (Mean ± SD) | 49.9 ± 15.6 |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion (units) | 6.03 ± 7 |

| Intraoperative plasma transfusion (units) | 7 ± 8.3 |

| Duration of operation (hours) (Mean ± SD) | 12.5 ± 3.1 |

| Hospital stay (postoperative) (days) (Mean ± SD) | 23.8 ± 16.6 |

| Immunosuppression regimen | |

| Regimen including FK | 176 (82.6%) |

| Regimen including cyclosporine | 63 (29.6%) |

| Regimen including sirolomus | 45 (21.1%) |

| Post operative acute rejection | 44 (20.7%) |

BMI: Body mass index, MELD: Model for end stage liver disease, PELD: Pediatric end stage liver disease, Portal HTN: Portal hypertension, PVT: Portal vein thrombosis, GRWR: Graft recipient weight ratio,SFSS: Small for size syndrome.

3.2. Primary disease

The most frequent indications in adults were HCV 100/186 (53.8%) followed by HCC 64/186 (34.5%). However (biliary atresia) BA followed by Byler's disease were the most frequent primary diseases in children. Table 2, Table 3.

Table 2.

Indications of LT in adults.

| HCV | 100/186 (53.8%) |

| HCV cirrhosis + HCC | 60 (32.3%) |

| HBV cirrhosis + HCC | 4 (2.2%) |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 7 (3.8%) |

| HBV | 6 (3.2%) |

| BCS | 2 (1.1%) |

| PSC | 3 (1.6%) |

| PBC | 1 (0.5%) |

| Wilson's disease | 1 (0.5%) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1 (0.5%) |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis | 1 (0.5%) |

HCV:Hepatitis C virus, HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma, HBV: Hepatitis B virus, BCS: Budd chiari syndrome, PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis, PBC: Primary biliary cirrhosis.

Table 3.

Indications of LT in pediatrics.

| Biliary atresia | 10 (37%) |

| Byler's disease | 6 (22.2%) |

| cavernous haemangiomas | 1/27 (3.7%) |

| Bile ducts paucity | 1 (3.7%) |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 2 (7.4%) |

| Wilson's disease | 1 (3.7%) |

| Secondary biliary cirrhosis from choledocal cyst | 1 (3.7%) |

| Crigler Najjar type I | 3 (11.1%) |

| Tyrosenemia | 2 (7.4%) |

3.3. Predictors of HA and/or PV complications

Upon univariate analysis, preoperative PVT was significant predictor complications. However there was a trend towards statistical significant higher complications with male recipients, compatible blood groups, and multiple PV anastomoses. On the other hand, in the adult subgroup, there was a trend towards statistical significant higher complications with Low protein S and positive factor 5 leiden mutation (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6).

Table 4.

Predictors of HA and/or PV.

| Category | HA and/or PV complications number (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 42/213 (19.7%) | |

| Recipient age > 18 years | ||

| Yes | 3/27 (11.1%) | >0.05 |

| No | 39/186 (21%) | |

| Recipient gender | ||

| Males | 39/183 (21.3%) | 0.1 |

| Females | 3/30 (10%) | |

| Donor gender | ||

| Males | 29/139 (20.9%) | >0.05 |

| Females | 13/74 (17.6%) | |

| Co-morbidity | ||

| Yes | 12/66 (18.2%) | >0.05 |

| No | 30/147 (20.4%) | |

| Portal HTN | ||

| Yes | 39/195 (20%) | >0.05 |

| No | 3/18 (16.7%) | |

| Bl. Group | ||

| Compatible | 18/67 (26.9%) | 0.08 |

| Identical | 24/146 (16.4%) | |

| Preoperative PVT | ||

| Yes | 9/27 (33.3%) | 0.049 |

| No | 33/186 (17.7%) | |

| Graft type | ||

| Right lobe | 38/178 (21.3%) | >0.05 |

| Left lobe | 1/9 (11.1%) | |

| Left lateral | 3/25 (12%) | |

| Monosegment | 0/1 (0) | |

| HV anastomosis | ||

| Single | 31/153 (20.3%) | >0.05 |

| Multiple | 11/60 (18.3%) | |

| PV anastomosis | ||

| Single | 36/197 (18.3%) | 0.06 |

| Multiple | 6/16 (37.5%) | |

| HA anastomosis | ||

| Single | 41/204 (20.1%) | >0.05 |

| Multiple | 1/9 (11.1) | |

| Multiple vascular anastomosis | ||

| Yes | 15/76 (19.7%) | >0.05 |

| No | 27/137 (19.7%) | |

| Immunosuppression regimen including sirolomus | ||

| Yes | 11/45 (24.4%) | >0.05 |

| No | 31/168 (18.4%) | |

| Acute rejection | ||

| Yes | 11/44 (25%) | >0.05 |

| No | 31/169 (18.3%) | |

Table 5.

Predictors of HA and/or PV.

| Category | VC (Mean± Std. deviation) | No VC (Mean± Std. deviation) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donor age | 27.2 ± 6.5 | 27.4 ± 6.5 | >0.05 |

| BMI of donor | 25.5 ± 3.1 | 25.3 ± 3.4 | >0.05 |

| MELD | 15.5 ± 4.3 | 16.1 ± 4.2 | >0.05 |

| PELD | 14 ± 7.2 | 15.3 ± 6.4 | >0.05 |

| Actual graft wt | 815.2 ± 218.9 | 746.2 ± 242.4 | 0.08 |

| Actual GRWR | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | >0.05 |

| Cold ischemia time/minutes | 68.9 ± 39.1 | 70.1 ± 48.1 | >0.05 |

| Warm ischemia time/minutes | 49.8 ± 15.2 | 50 ± 15.7 | >0.05 |

| Blood transfusion (units) | 6.7 ± 6.7 | 5.9 ± 7 | >0.05 |

| Plasma transfusion (units) | 8.1 ± 10.5 | 6.7 ± 7.8 | >0.05 |

| Operative time/h | 12.9 ± 2.3 | 12.4 ± 3.4 | >0.05 |

Table 6.

Some predictors in adults.

| Category | VC number (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 39/186 (21%) | |

| Protein S | ||

| Low | 15/53 (28.3%) | 0.1 |

| Normal | 24/133 (18%) | |

| Protein C | ||

| Low | 14/53 (26.4%) | >0.05 |

| Normal | 25/133 (18.8%) | |

| Antithrombin III | ||

| Low | 26/112 (23.2%) | >0.05 |

| Normal | 13/74 (17.6%) | |

| Homocysteine | ||

| High | 19/86 (22.1%) | >0.05 |

| Normal | 20/100 (20%) | |

| Factor 5 leiden mutation | ||

| Positive | 14/47 (29.8%) | 0.09 |

| Negative | 25/139 (18%) | |

3.4. HA and/or PV complications and their management

The overall incidence of complications was 42/213 (19.7%). The adult and pediatric complications were 18.3% and 1.4% respectively. However, early complications (before 1 month) and late ones (After 1 month) were 9.4% and 10.3% respectively. These complications were classified into HA, PV and simultaneous HA and PV problems.

The incidence of HA problems was 32 (15%), in the form of HAS 18 (8.4%) HAT 9 (4.2%) (N.B one of them had aneurysm), HA injury 4 (1.9%) and arterial steel syndrome (ASS) to gastroduodenal artery (GDA) 1 (0.5%).

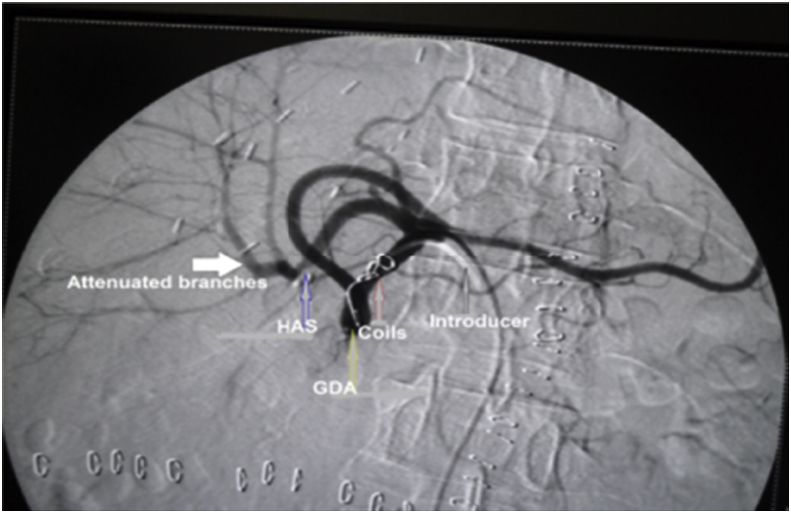

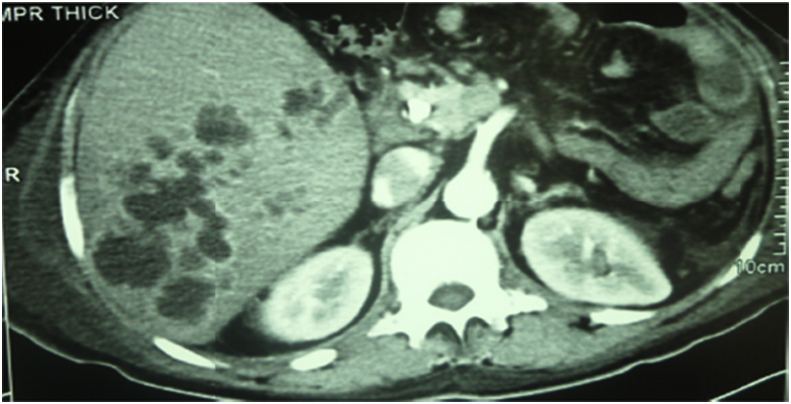

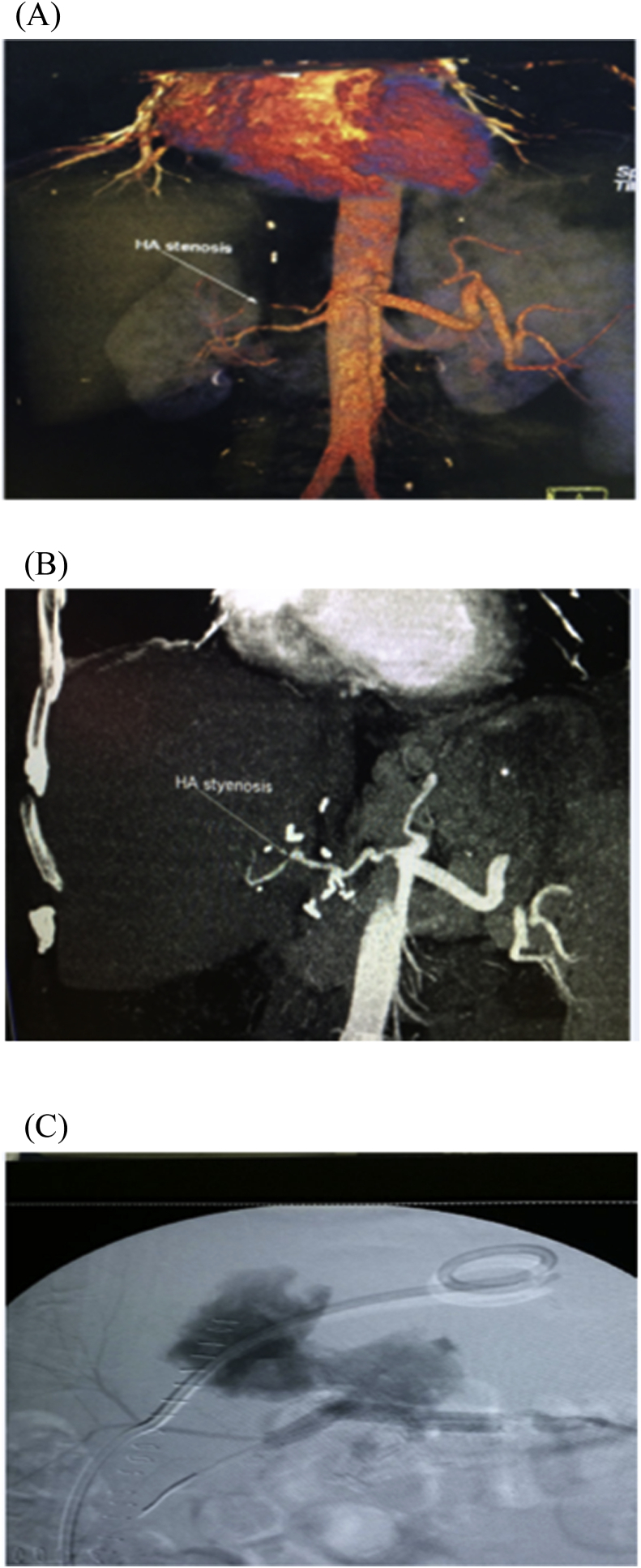

HAS was divided into early 4 (1.9%) and late stenosis 14 (6.5%), the early four cases were managed unsuccessfully, where 2 of them underwent anticoagulant therapy, one of them underwent angiographic dilatation and the last one underwent surgical reconstruction. On the other hand, 12 of patients with late HAS were successfully managed where 9 of them underwent angiographic dilatation and stenting (Fig. 5), one of them underwent angiographic dilatation and coiling of GDA (Fig. 6), one of them underwent angiographic dilation (Fig. 7), and the last patient underwent anticoagulant therapy, however, 2/14 of patients with late HA stenosis were managed unsuccessfully, where one of them underwent anticoagulant therapy and the other one underwent angiographic dilatation and stenting.

Fig. 5.

Patient with HAS at anastomotic site underwent successful angiographic dilatation and stenting.

Fig. 6.

Patient with HAS underwent successful angiographic dilatation and coiling of GDA.

Fig. 7.

Patient with HAS underwent successful angiographic dilatation.

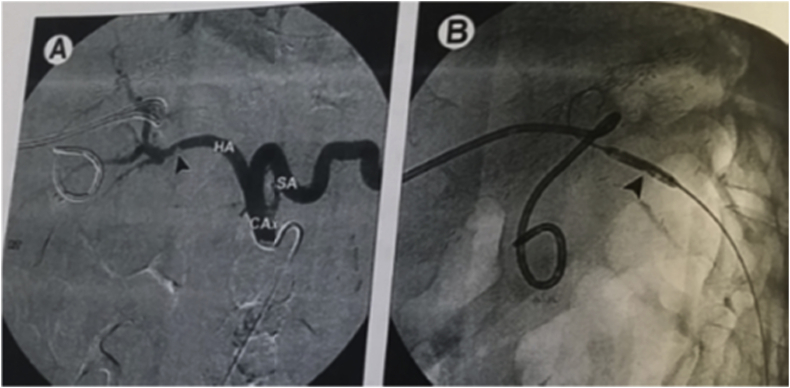

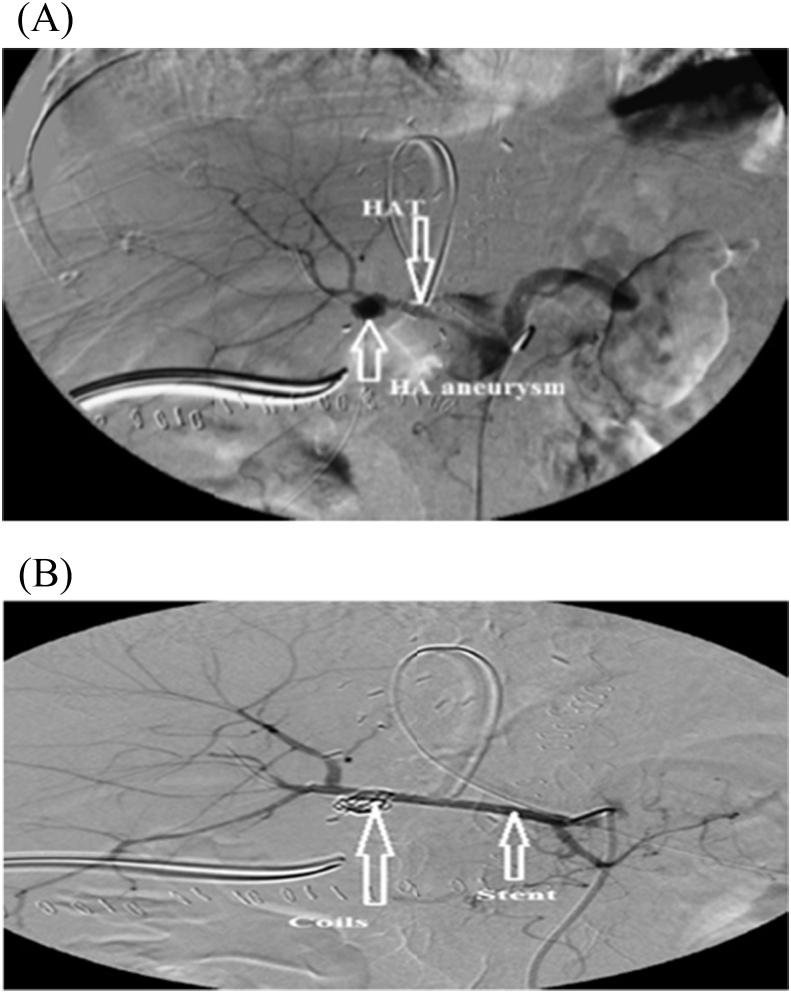

HAT was divided into 4 early and 5 late cases, one of the early four cases underwent successful surgical thrombectomy and reconstruction, however, the other three cases were managed unsuccessfully, where, two patients underwent surgical thrombectomy and reconstruction, and the other patient was given anticoagulant therapy. On the other hand, the five recepients with late HAT were managed as follow: Successful anticoagulant therapy for one patient, unsuccessful anticoagulant therapy for another patient, and the last three recepients underwent unsuccessful angiographic thrombolytic therapy (N.B one of them had aneurysm and underwent stenting of HAT and coiling of the aneurysm Fig. 8, one of them underwent stenting and multiple pigtail drainage of multiple hepatic abscesses Fig. 9, and the last one underwent surgical reconstruction after failure of angiography).

Fig. 8.

(A) A patient with HAT and aneurysm. (B)- The patient underwent coiling of aneurysm and stenting of HAT.

Fig. 9.

A patient with HAT and multiple hepatic abscesses managed with stenting of HAT and pigtail for abscesses.

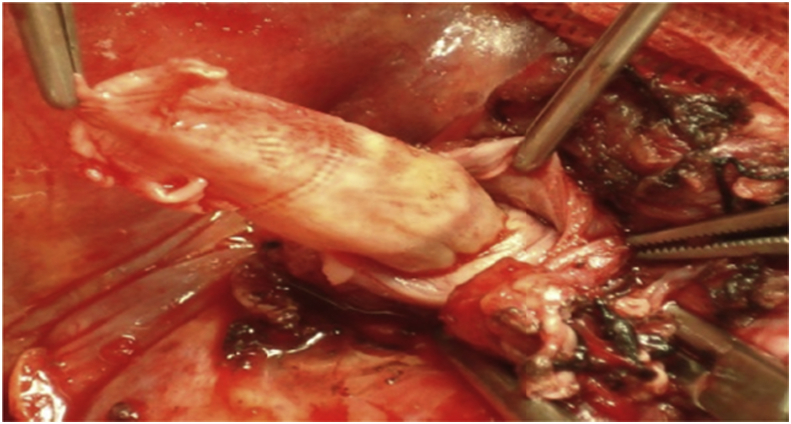

HA injury was classified into early three and late one case, two of the early three cases underwent conservative follow up, however the other case underwent unsuccessful surgical exploration, conversely, the only patient with late HA injury underwent successful surgical exploration Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

(A),(B), (C): patient with HA injury due to angiographic stenting for stenosis, patient was surgically explored and controlled.

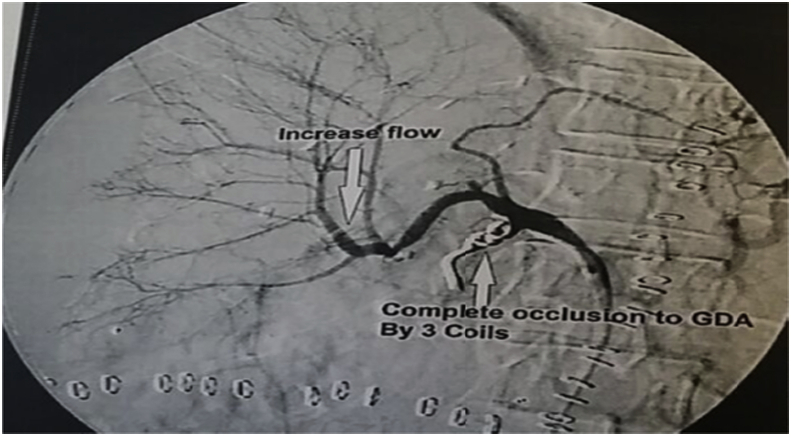

Lastly, the only patient with late ASS to GDA underwent coiling of the GDA but with failure (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11.

Patient with GDASS, underwent coiling of GDA, the flow improved at 1st in HA and then decreased again.

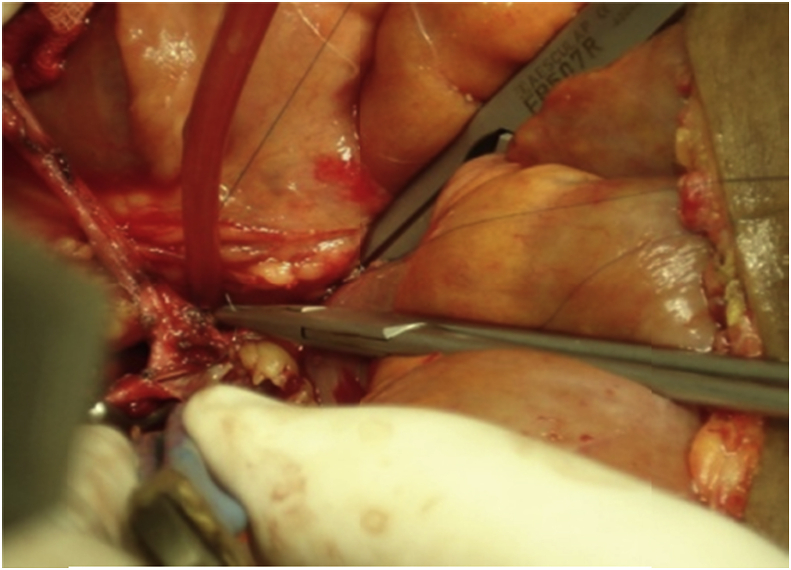

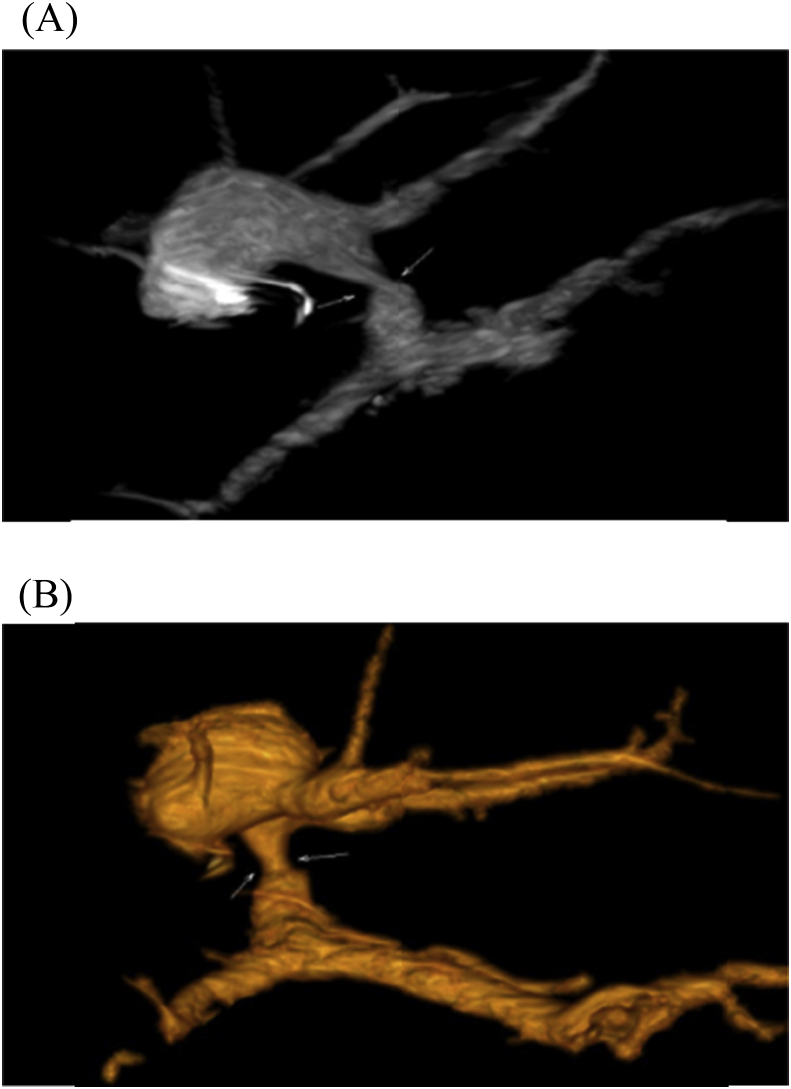

The incidence of PV problems was 6 (2.8%) that was divided into one late PVS and five early PVT. The only case with late PVS underwent unsuccessfull angiographic dilatation and stenting (Fig. 12), however, two of the five patients with early PVT underwent unsuccessful anticoagulant therapy, two of them underwent unsuccessful surgical thrombectomy and the last one (with segmental PVT) underwent successful anticoagulant therapy (Fig. 13).

Fig. 12.

(A), (B) patient with late PVS underwent unsuccessfull angiographic dilatation and stenting.

Fig. 13.

(A), (B) patient with segmental PVT underwent successful anticoagulant therapy.

The incidence of simultaneous HA and PV problems was 4 (1.9%), in the form of three early simultaneous HAT and PVT and one early simultaneous HAS and PVT. One of the three patients with early simultaneous HAT and PVT underwent successful anticoagulant therapy; conversely, the other two patients underwent unsuccessful surgical thrombectomy and reconstruction. Lastly, the only case with early simultaneous HAS and PVT underwent successful anticoagulant therapy Table 7.

Table 7.

HA and/or PV complications and their management.

| The complications | No % | Management | No (%) | Treatment result |

No (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success | Failure | |||||

| The overall incidence of HA and/or PV complications | 42/213 (19.7%) | None | 2 (0.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medical | 12 (5.6%) | 5 | 7 | 12 (5.6%) | ||

| Angiography | 18 (8.5%) | 11 | 7 | 18 (8.5%) | ||

| Surgery | 10 (4.7%) | 2 | 8 | 10 (4.7%) | ||

| Adult complications | 39/213 (18.3%) | None | 2 (0.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medical | 10 (4.7%) | 5 | 5 | 10 (4.7%) | ||

| Angiography | 18 (8.5%) | 11 | 7 | 18 (8.5%) | ||

| Surgery | 9 (4.2%) | 2 | 7 | 9 (4.2%) | ||

| Pediatric complications | 3/213 (1.4%) | Medical | 2 (0.9%) | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.9%) |

| Surgery | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Early VC (before 1 month) | 20/213 (9.4%) | None | 2 (0.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medical | 8 (3.8%) | 3 | 5 | 8 (3.8%) | ||

| Angiography | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Surgery | 9 (4.2%) | 1 | 8 | 9 (4.2%) | ||

| Late VC (After 1 month) | 22/213 (10.3%) | None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Medical | 4 (1.9%) | 2 | 2 | 4 (1.9%) | ||

| Angiography | 17 (8%) | 11 | 6 | 17 (8%) | ||

| Surgery | 1 (0.5%) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| HA problems | 32/213 (15%) | |||||

| HAS | ||||||

| Early | 4 (1.9%) | Medical | 2 (0.9%) | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.9%) |

| Angiography | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Surgery | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Late | 14 (6.5%) | Medical | 2 (0.9%) | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.9%) |

| Angiography | 12 (5.6%) | 11 | 1 | 12 (5.6%) | ||

| HAT | ||||||

| Early | 4 (1.9%) | Medical | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.5%) |

| Surgery | 3 (1.4%) | 1 | 2 | 3 (1.4%) | ||

| Late | 5 (2.3%) | Medical | 2 (0.9%) | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.9%) |

| Angiography | 3 (1.4%) | 0 | 3 | 3 (1.4%) | ||

| HA injury | ||||||

| Early | 3 (1.4%) | None | 2 (0.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Surgery | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Late | 1 (0.5%) | Surgery | 1 (0.5%) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.5%) |

| Steal phenomenon to GDA | ||||||

| Late | 1 (0.5%) | Angiography | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.5%) |

| PV problems: | 6/213 (2.8%) | |||||

| PVS | ||||||

| Late | 1 (0.5%) | Angiography | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 | 1 (0.5%) |

| PVT | ||||||

| Early | 5 (2.3%) | Medical | 3 (1.4%) | 1 | 2 | 3 (1.4%) |

| Surgery | 2 (0.9%) | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.9%) | ||

| Simultaneous HA and PV problem | 4/213 (1.9%) | |||||

| HAT and PVT | ||||||

| Early | 3 (1.4%) | Medical | 1 (0.5%) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.5%) |

| Surgery | 2 (0.9%) | 0 | 2 | 2 (0.9%) | ||

| HAS and PVT | ||||||

| Early | 1 (0.5%) | Medical | 1 (0.5%) | 1 | 0 | 1 (0.5%) |

HAT: Hepatic artery thrombosis, GDA: Gastroduodenal artery, HAS: Hepatic artery stenosis.

3.5. Outcome of patients

The 6-month, 1-, 3-, 5- 7- and 10-year survival rates in patients with and without HA and/or PV complications were 54.8%, 42.9%, 38.1%, 38.1%, 38.1% and 38.1% and 67.8%, 66.1%, 60.2%,59.6%, 58.5% and 58.5% respectively. On the other hand, the overall mortality, mortality in patients with HA and/or PV complication and mortality directly related to complications were 97/213 (45.5%), 26/42 (61.9%) and 13/42 (31%) respectively Table 8.

Table 8.

Outcome of patients.

| Total | No (%) |

|---|---|

| 213 (100%) | |

| Survival per months (Mean ± SD) (Range) | 30.7 ± 31.2 (0–134) |

| All recepients | |

| 6-month survival | 139/213 (65.3%) |

| 1-year survival | 131/213 (61.5%) |

| 3-year survival | 119/213 (55.9%) |

| 5-year survival | 118/213 (55.4%) |

| 7-year survival | 116/213 (54.5%) |

| 10-year survival | 116/213 (54.5%) |

| HA and/or PV complication | |

| 6-month survival | 23/42 (54.8%) |

| 1-year survival | 18/42 (42.9%) |

| 3-year survival | 16/42 (38.1%) |

| 5-year survival | 16/42 (38.1%) |

| 7-year survival | 16/42 (38.1%) |

| 10-year survival | 16/42 (38.15) |

| No complications | |

| 6-month survival | 116/171 (67.8%) |

| 1-year survival | 113/171 (66.1%) |

| 3-year survival | 103/171 (60.2%) |

| 5-year survival | 102/171 (59.6%) |

| 7-year survival | 100/171 (58.5%) |

| 10-year survival | 100/171 (58.5%) |

| Adults | |

| 6-month survival | 123/186 (66.1%) |

| Overall survival | 103/186 (55.4%) |

| Pediatrics | |

| 6-month survival | 16/27 (59.3%) |

| Overall survival | 13/27 (48.1%) |

| Graft survival | 114/213 (53.5%) |

| Mortality in all patients | 97/213 (45.5%) |

| Mortality in patients with HA and/or PV complication | 26/42 (61.9%) |

| Mortality directly related to HA and/or PV complication | 13/42 (31%) |

| Causes | |

| PVT | 6/42 (14.3%) |

| Iatrogenic bleeding | 4/42 (9.5%) |

| HAT | 3/42 (7.1%) |

3.6. VC and survival

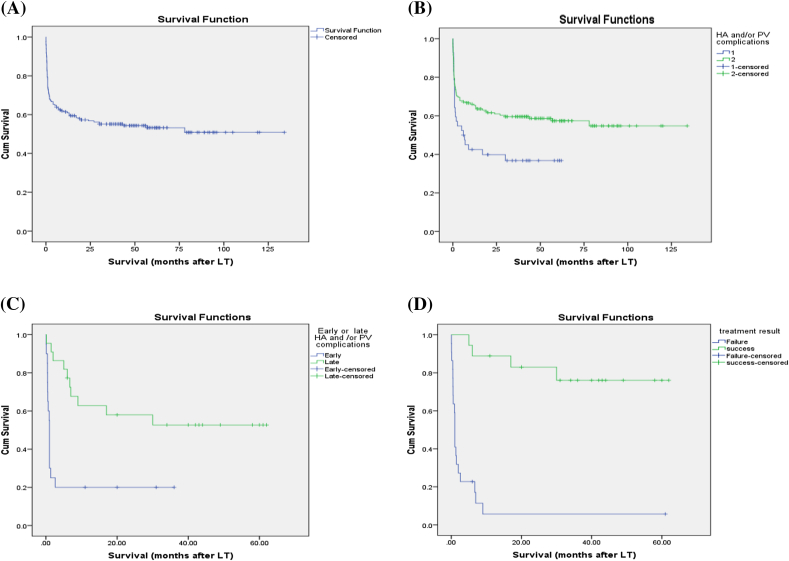

Upon univariate analysis, VC was significant predictor of poor survival especially early complications, while the effective management of them improved survival (Table 9, Fig. 14).

Table 9.

Univariate analysis of VC and survival.

| Category | Survival no (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Total no of patients | 116/213 (54.5%) | |

| Vascular complications | 0.02 | |

| Yes | 16/42 (38.1%) | 0.02 |

| No | 100/171 (58.5%) | |

| Early complications | 4/20 (20%) | |

| Late complications | 12/22 (54.5%) | |

| Management of VC | ||

| Yes | 16/40 (40%) | 0.2 |

| No | 0/2 (0) | |

| Effective treatment | 0.000 | |

| Yes | 14/18 (77.8%) | |

| No | 2/22 (9.1%) | |

Fig. 14.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves (A, B and C,D). A: KM survival curve. B: VC and survival (Log rank = 0.02). C- Early or late VC and survival (Log rank = 0.001). D: Effective treatment and survival (Log rank = 0.00).

4. Discussion

Liver transplantation has become the treatment of choice for ESLD in adults and children. Despite technical advances and improvements in postoperative care, VC after LT continues to be a major cause of mortality or graft loss [29].

The rate of VC after LT ranges from 7% to 25% [3], [6], [9], [22], [30], [31], [32], [33]. Similarly, The overall incidence of HA and/or PV complications was 19.7% in our study. The risk of these complications is relatively higher in children when compared with adults (This may be due to unique technical challenges posed by smaller vessels and size mismatch between graft and recipient vessels) [5], [6], [19], [34]. It was 18.8%, 19% and 19.8%, in, Zameer et al., 2011 [34] Orlandinia et al., 2014 [2] and Chen et al., 2008 [35] pediatric studies respectively. In contrast, it was lower in our pediatrics (1.4%) when compared with our adults (18.3%). This low incidence was due to small number of our children [27] when compared with our adults (186) and increased early mortality in them, so, there was no chance for late VC to be observed.

Various factors contributing to development of vascular thrombosis have been proposed: ABO incompatibility [4], [10], [11], [12], [13], multiple anastomoses [11], prolonged cold ischemic time [2], [4], [10], [12], [14], [36], [37], acute rejection. [4], [10], [11], [12], [14], [38], GRWR < 4% and blood transfusion volume <270 mL [18]. On the other hand, in our series, there was a trend towards statistical significant higher HA and/or PV complications with male recipients, compatible blood groups, and multiple PV anastomoses, and in our adult subgroup, there was a trend towards statistical significant higher HA and/or PV complications with Low protein S and positive factor 5 leiden mutation. Conversely, there was no significant correlation between cold ischemia time, acute rejection, GRWR or amount of blood transfusion and complications in our work.

Although previously considered as a contraindication, successful LT has been performed in the presence of pre-existing PVT, both in deceased donor LT and LDLT. [19] and [39]. However reconstruction of the PV becomes difficult when PVT exist with a considerable peri-operative risk for LT candidates and post operative PV complications, with a recurrence rates ranging from 0% to 30%, depending on its extension and severity [40], [41]. Furthermore, In our study, preoperative PVT was the only significant predictor of post operative HA and/or PV complications, similarly, Previous vascular thrombosis was a risk factor for HAT in Scarinci et al., 2010 [11] study. In contrast, pre-existing PVT was not a predictor of VC In Mali et al., 2012 [19] study.

HA complications after LDLT, including HAT, stenosis, spasm, kinks, aneurysms, dissection, and ASS can directly affect both the graft and recipient outcomes. [42] and [43], they result in increased graft loss, and mortality of the LDLT recipients [28] and [44]. In our work, the arterial complication rate was 15% (n = 32). However it was 6.2%, 11% and 21.5% in Mali et al., 2012 [19], Orlandinia et al., 2014 [2] and Jeon et al., 2008 [44] studies respectively.

HAS ranges from 5% to 11% [9], [29], [45]. Similarly, it was 8.4% in our study. Regarding their management, endovascular intervention was successful treatment in Steinbrück et al., 2011 [9] and Wakiya et al., 2013 [42] studies. Similarly, angiography was the main treatment option of our patients with HAS where 11/18 (61%) of them were successfully managed with angiography as nine of them underwent angiographic dilatation and stenting, one of them underwent angiographic dilatation and coiling of GDA, and the last patient underwent angiographic dilation.

HAT is a serious problem; It is associated with increased morbidity, graft loss, and mortality, its incidence after LDLT varies from 4% to 26% [29], [46], [47]. Similarly, It was 4.2% in our study.

The treatment options for HAT include urgent revascularization, either with the native HA following thrombectomy or with HA alternatives [11], [19], [27], [28], [42]. Other options include the use of intraarterial thrombolytics as urokinase [12], [19], [44] and lastly conservative treatment (In the absence of hepatic failure) [19], [27], [42] Similarly, in our series, there were 9 patients with HAT (4 early and 5 late), where one of the early four cases underwent successful surgical thrombectomy and reconstruction, however, the other three cases were managed unsuccessfully, where, two patients underwent surgical thrombectomy and reconstruction, and the other patient was given anticoagulant therapy. On the other hand, three of the five recepients with late HAT underwent unsuccessful angiographic thrombolytic therapy and the other two patients were given medical treatment that succeeded in one of them.

Complications like rupture and perforation of HA can arise after endovascular treatment of HA complications, with the incidence ranging from 5.0% to 20.0%, [48], [49], [50], [51]. However, in our study, there were 4 cases with iatrogenic HA injury (HAI) (three early cases due to pigtail drainage for early biliary collection and one late from angiographic stenting for HA stenosis). The only patient with late HA injury underwent successful surgical exploration. In contrast, the other three early cases were managed unsuccessfully (surgically and conservatively).

ASS is defined by decreased perfusion of one arterial branch because of diversion of blood flow into a different arterial branch originating from the same trunk [43]. After orthotropic LT, a shift of hepatic blood flow into the splenic artery (lienalis steal syndrome) or GDA (gastroduodenal steal syndrome) has been observed [52], in our series, we had a patient with late ASS to GDA underwent coiling of the GDA, and the flow in HA improved at 1st but unfortunately, it decreased again (I.e. Treatment failure).

Thrombosis and/or stenosis of the PV are reported to occur in 1–16% of liver recipients [9], [29], [45], [53]. Similarly, the incidence of PV problems was 2.8% (n = 6) in the present patients. However, it was 8% and 11.5% in Ueda et al., 2005 [17] and Moon et al., 2010 [18] studies respectively.

Early PVT may be amenable to attempts at recanalization by (anticoagulation) or operative thrombectomy [54]. For chronic PV problems, interventional angiography (Thrombolytics for PVT or balloon angioplasty for PVS) can be done [1], [6], [55], [56], [57]. However, in our series, only one of the five patients with early PVT underwent successful anticoagulant therapy, however the other four patients were managed unsuccessfully (medically and surgically) and the only case with late PVS underwent unsuccessfull angiographic dilatation and stenting.

Simultaneous HA and PVT after LT is a life threatening event [37]. Two percent developed simultaneous thrombosis of HA and PV after the operation in Kaneko et al., 2004 [58] study where, Emergent thrombectomy was performed in three patients; and the remaining patient was considered for retransplantation; but, all of the patients died due to hepatic failure. On the other hand, in our work, the incidence of simultaneous HA and PV problems was 1.9% (n = 4) and all of them were early complications. One of the three patients with simultaneous HAT and PVT and the only case with simultaneous HAS and PVT underwent successful anticoagulant therapy. Conversely, the other two patients with simultaneous HAT and PVT underwent unsuccessful surgical thrombectomy and reconstruction.

VC affected outcome in Orlandinia et al., 2014 [2], Khalaf, 2010 [6] and Steinbrück et al., 2011 [9] studies. Similarly, it was statistically lower in our recipients with VC. In conclusion: HA and/or PV complications specially early ones lead to significant poor outcome after LDLT, so proper dealing with the risk factors like pre LT PVT (I.e. More intensive anticoagulation therapy) and the effective management of these complications are mandatory for improving outcome.

Ethical approval

The approval by our institutional review board (IRB).

Sources of funding

No source of funding for this research.

Author contribution

Emad Hamdy Gad: Study design, data collection and writing.

Mohammed Alsayed abdelsamee: Data collection and data analysis.

Yasmin Kamel: Data collection.

Conflicts of interest

No conflict of interest to declare.

Trial registry number

This is a retrospective study (not RCT).

Guarantor

All the authors of this paper accept full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Research Registration Unique Identifying Number (UIN)

Researchregistry691.

Footnotes

This study was approved by our institution ethical committee. Forms of support received by each author for this study included good selection of cases, instructive supervision, continuous guidance, valuable suggestions and good instructions. No grant or other financial support was received for this study.

References

- 1.Karakayali H., Sevmis S., Boyvat F. Diagnosis and treatment of late-onset portal vein stenosis after pediatric living-donor liver transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2011;43:601–604. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orlandini M., Feier F.H., Jaeger B. Frequency of and factors associated with vascular complications after pediatric liver transplantation. J. Pediatr. (Rio J) 2014;90:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duffy J.P., Hong J.C., Farmer D.G. Vascular complications of orthotropic liver transplantation: experience in more than 4,200 patients. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2009;208:896–905. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pawlak J., Grodzicki M., Leowska E. Vascular complications after liver transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2003;35:2313–2315. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00836-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yilmaz A., Arikan C., Tumgor G. Vascular complications in living related and deceased donation pediatric liver transplantation: single center's experience from Turkey. Pediatr. Transpl. 2007;11:160–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2006.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khalaf H. Vascular complications after deceased and living donor liver transplantation: a single-center experience. Transpl. Proc. 2010;42:865–870. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang T.L., Cheng Y.F., Chen T.Y. Doppler ultrasound evaluation of postoperative portal vein stenosis in adult living donor liver transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2010;42:879–881. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hardikar W., Poddar U., Chamberlain J. Evaluation of a post-operative thrombin inhibitor replacement protocol to reduce haemorrhagic and thrombotic complications after paediatric liver transplantation. Thromb. Res. 2010;126:191–214. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinbrück K., Enne M., Fernandes R. Vascular complications after living donor liver transplantation: a Brazilian, single-center experience. Transpl. Proc. 2011;43:196–198. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wozney P., Zajko A.B., Bron K.M. Vascular complications after liver transplantation: a 5-year experience. AJR. 1986;147:657–663. doi: 10.2214/ajr.147.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarinci A., Sainz-Barriga M., Berrevoet F. Early arterial revascularization after hepatic artery thrombosis may avoid graft loss and improve outcomes in adult liver transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2010;42:4403–4408. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sevmis S., Karakayali H., Tutar N.U. Management of early hepatic arterial thrombosis after pediatric living-donor liver transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2011;43:605–608. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marubashi S., Kobayashi S., Wada H. Hepatic artery reconstruction in living donor liver transplantation: risk factor analysis of complication and a role of MDCT scan for detecting anastomotic stricture. World J. Surg. 2013;37:2671–2677. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva M.A., Jambulingam P.S., Gunson B.K. Hepatic artery thrombosis following orthotopic liver transplantation: a 10-year experience from a single centre in the United Kingdom. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:146–151. doi: 10.1002/lt.20566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikegami T., Hashikura Y., Nakazawa Y. Risk factors contributing to hepatic artery thrombosis following living-donor liver transplantation. J. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Surg. 2006;13:105–109. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li C., Wen T.F., Yan L.N. Predictors of patient survival following living donor liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2011;10:248–253. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ueda M., Egawa H., Ogawa K. Portal vein complications in the long-term course after pediatric living donor liver transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2005;37:1138–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon J.I., Jung G.O., Choi G.-S. Risk factors for portal vein complications after pediatric living donor liver transplantation with left-sided grafts. Transplant. Proc. 2010;42:871–875. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.02.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mali V.P., Aw M., Quak S.H. Vascular complications in pediatric liver transplantation; single-center experience from Singapore. Transplant. Proc. 2012;44:1373–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.01.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banshodani M., Tashiro H., Onoe T. Long-term outcome of hepatic artery reconstruction during living-donor liver transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2011;43:1720–1724. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uchiyama H., Hashimoto K., Hiroshige S. Hepatic artery reconstruction in living donor liver transplantation: a review of its techniques and complications. Surgery. 2002;131:S200–S204. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.119577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstein M.J., Salame E., Kapur S. Analysis of failure in living donor liver transplantation: differential outcomes in children and adults. World J. Surg. 2003;27:356–364. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6598-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuan L., Tian-Fu W., Lu-Nan Y. Predictors of patient survival following living donor liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 2011;10:248–253. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taniai N., Onda M., Tajiri T. Anticoagulant therapy in living-related liver transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2002;34:2788–2790. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francoz C., Valla D., Durand F. Portal vein thrombosis, cirrhosis, and liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2012;57:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaneko J., Sugawara Y., Tamura S. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia after liver transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2014;40:1518–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian M.G., Tso W.K., Lo C.M. Treatment of hepatic artery thrombosis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Asian J. Surg. 2004;27:213–217. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60035-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang C.C., Lin T.S., Chen C.L. Arterial reconstruction in hepatic artery occlusions in adult living donor liver transplantation using gastric vessels. Surgery. 2008;143:686–690. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tamsel S., Demirpolat G., Killi R. Vascular complications after liver transplantation: evaluation with Doppler US. Abdom. Imaging. 2007;32:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s00261-006-9041-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin M., Moon H.H., Kim J.M. Importance of donor-recipient age gradient to the prediction of graft outcome after living donor liver transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2013;45:3005–3012. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin C.C., Chuang F.R., Wang C.C. Early postoperative complications in recipients of living donor liver transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2004;36:2338–2341. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marsh J.W., Gray E., Ness R. Complications of right lobe living donor liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2009;51:715–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vali T., Tein A., Tikk T. Surgical complications accompanying liver transplantation in Estonia. Transpl. Proc. 2010;42:4455–4456. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.09.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zameer M.M., Vinay C., Rao S. Vascular complications in living donor pediatric liver transplant (LDLT) J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 2011;1:133–154. doi: 10.1016/S0973-6883(11)60159-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen H.L., Concejero A.M., Huang T.L. Diagnosis and interventional radiological treatment of vascular and biliary complications after liver transplantation in children with biliary atresia. Transplant. Proc. 2008;40:2534–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buckels J.A.C., Tisone G., Gunson B.K. Low hematocrit reduces hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 1989;21:2460–2461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langnas A.N., Marujo W., Stratta R.J. Vascular complication after orthotopic liver transplantation. Am. J. Surg. 1991;161:76–83. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90364-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuel D., Gillet D., Castaing D. Portal and arterial thrombosis in liver transplantation: a frequent even in severe rejection. Transpl. Proc. 1989;21:2225–2227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kadry Z., Seizner N., Handschin A. Living donor liver transplantation in patients with portal vein thrombosis: a survey and review of technical issues. Transplantation. 2002;74:696–701. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orlando G., De L.L., Toti L. Liver transplantation in the presence of portal vein thrombosis: report from a single center. Transpl. Proc. 2004;36:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ou H.Y., Concejero A.M., Huang T.L. Portal vein thrombosis in biliary atresia patients after living donor liver transplantation. Surgery. 2011;149:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wakiya T., Sanada Y., Mizuta K. A comparison of open surgery and endovascular intervention for hepatic artery complications after pediatric liver transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2013;45:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim S.Y., Kim K.W., Kim M.J. Multidetector row CT of various hepatic artery complications after living donor liver transplantation. Abdom. Imaging. 2007;32:635–643. doi: 10.1007/s00261-006-9145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jeon G.S., Won J.H., Wang H.J. Endovascular treatment of acute arterial complications after living-donor liver transplantation. Clin. Radiol. 2008;63:1099–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim B.S., Kim T.K., Jung D.J. Vascular complications after living related liver transplantation: evaluation with gadolinium enhanced three-dimensional MR angiography. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;181:467–474. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.2.1810467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y., Yan L.N., Zhao J.C. Microsurgical reconstruction of hepatic artery in A-A LDLT: 124 consecutive cases without HAT. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2682–2688. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i21.2682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li P.-C., Jeng L.-B., Yang H.-R. Hepatic artery reconstruction in living donor liver transplantation: running suture under surgical loupes by cardiovascular surgeons in 180 recipients. Transplant. Proc. 2012;44:448–450. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saad W.E. Management of hepatic artery steno-occlusive complications after liver transplantation. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2007;10:207–220. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kodama Y., Sakuhara Y., Abo D. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for hepatic artery stenosis after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:465–469. doi: 10.1002/lt.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Orons P., Zajko A., Bron K. Hepatic artery angioplasty after liver transplantation: experience in 21 allografts. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2005;6:523–529. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim B., Won J., Maruzzelli L. Percutaneous endovascular treatment of hepatic artery stenosis in adult and pediatric patients after liver transplantation. Cardiovasc Interv. Radiol. 2010;33:1111–1119. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9848-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nussler N.C., Settmacher U., Haase R. Diagnosis and treatment of arterial steal syndromes in liver transplant recipients. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:596–602. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.50080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ko E.Y., Kim T.K., Kim P.Y. Hepatic vein stenosis after living donor liver transplantation: evaluation with Doppler US. Radiology. 2003;229:806–810. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2293020700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ueda M., Oike F., Kasahara M. Portal vein complications in pediatric living donor liver transplantation using left-side grafts. Am. J. Transpl. 2008;8:2097–2105. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woo D.H., Laberge J.M., Gordon R.L. Management of portal venous complications after liver transplantation. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2007;10:233–239. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vignali C., Cioni R., Petruzzi P. Role of interventional radiology in the management of vascular complications after liver transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2004;36:552–554. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kawano Y., Mizuta K., Sugawara Y. Diagnosis and treatment of pediatric patients with late-onset portal vein stenosis after living donor liver transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2009;22:1151–1158. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaneko J., Sugawara Y., Togashi J. Simultaneous hepatic artery and portal vein thrombosis after living donor liver transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 2004;36:3087–3089. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]