Abstract

Chiral boronic esters are useful intermediates in asymmetric synthesis. We have previously shown that carbonyl-directed catalytic asymmetric hydroboration (CAHB) is an efficient approach to the synthesis of functionalized primary and secondary chiral boronic esters. We now report oxime-directed CAHB of alkyl-substituted methylidene and trisubstituted alkene substrates by pinacolborane (pinBH) affords oxime-containing chiral tertiary boronic esters with yields up to 87% and enantiomer ratios up to 96:4 er. The utility of the method is demonstrated by the formation of chiral diols and O-substituted hydroxylamines, the generation of quaternary carbon stereocenters via carbon-carbon coupling reactions, and the preparation of chiral 3,4,4-trisubstituted isoxazolines.

Keywords: hydroboration, asymmetric catalysis, rhodium-catalyzed, oxime-directed, homogeneous catalysis

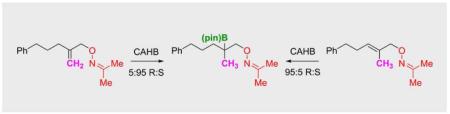

Catalytic asymmetric hydroboration (CAHB) has attracted renewed interest for the synthesis of chiral organoboronates. Many of the successful applications exploit the reaction of vinyl arene substrates.[1,2] Our research has instead focused on the directed-CAHB of β,γ-unsaturated amide and ester substrates. The carbonyl moiety controls regiochemistry in the rhodium-catalyzed addition of simple achiral boranes, such as pinacolborane (pinBH), and chiral phosphite and phosphoramidite ligands control the π-facial selectivity. A variety of chiral primary and secondary boronic esters are readily synthesized.[3] For example, under the conditions specified in Figure 1, methylidene derivative 1 undergoes regioselective CAHB on the alkene si face to afford chiral hydroxyamide 2 in 96:4 er after oxidation of the intermediate γ–borylated amide.

Figure 1.

In contrast to carbonyl-directed CAHB, the reaction of a similar oxime ether substrate leads to the formation of a chiral tertiary boronic ester.

Encouraged by the success of carbonyl-directed CAHB, we are exploring the effectiveness of other potential directing groups. Oxime functionality has been used in conjunction with a variety of transition metal catalyst systems to direct metallation reactions, most frequently to direct ortho-C–H activation of aromatic substrates but increasingly applied to Csp3–H activation as well.[4] In addition, Sanford and co-workers recently reported oxime-directed palladium-catalyzed dioxygenation of an adjacent alkene.[5]

Our initial attempts at oxime-directed CAHB employed benzophenone-derived allylic oxime ethers such as 3. While rhodium-catalyzed hydroboration of 3 led to some γ-borylation, the yield of 4 (after oxidation) is low and the enantioselectivity is poor. The major side reactions are ortho-borylation of the benzophenone-derived oxime with concomitant alkene reduction.[6] We now report that the corresponding acetone-derived oxime ethers are excellent substrates for oxime-directed CAHB; for example, 5a undergoes oxime-directed CAHB/oxidation to give 6a in good yield (71%) and with high levels of asymmetric induction (95:5 er). Furthermore, the borylated intermediate is a tertiary boronic ester arising from re-face β–borylation; in contrast, carbonyl-directed CAHB of 1 proceeds via si-face γ–borylation. It seems likely that the contrasting regio- and stereochemical outcomes obtained with 1 versus 5a arise due to the presence of the oxime substituents in the substrate-catalyst complex, although more work is needed to prove this unambiguously.

Chiral boronic acid derivatives are valuable intermediates in organic synthesis.[7] In particular, recent reviews by Aggarwal highlight transformations of chiral tertiary boronic esters,[ 8 ] including their use for the construction of multiple contiguous quaternary stereocenters.[9] However, the formation of tertiary organoboronates via metal-catalyzed or stoichiometric hydroboration, is rare since hydroboration generally proceeds in an anti-Markovnikov fashion delivering boron to the less substituted site on the alkene.[1, 10]

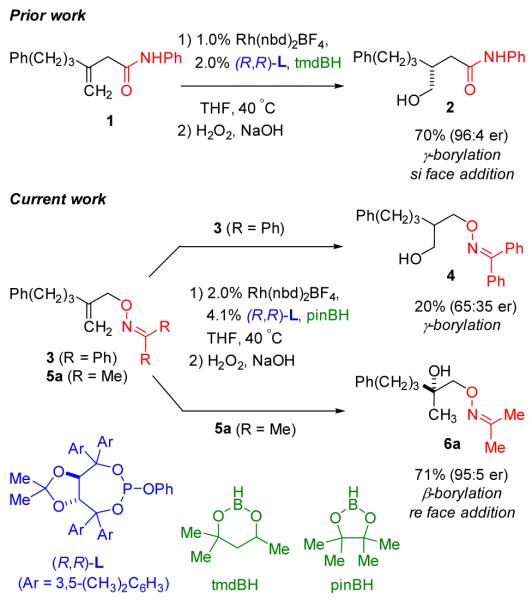

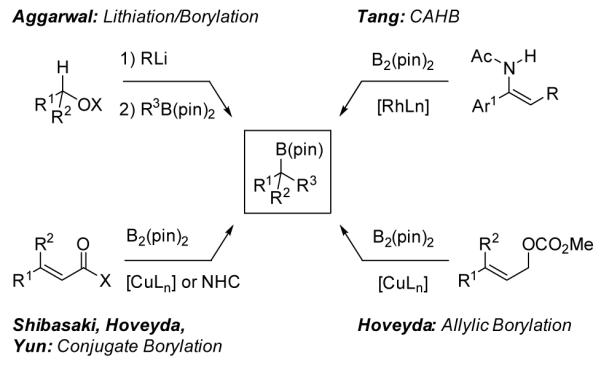

Several complementary methods for the preparation of chiral tertiary boronic esters have recently been reported (Figure 2). Three of these methods use bis(pinacolato)diboron (B2pin2) to carry out the net hydroboration of functionalized alkenes. For example, Tang recently described a remarkable rhodium-catalyzed reaction of α-arylenamides with B2(pin)2 to provide the first enantioselective synthesis of chiral tertiary α-aminoboronic esters.[11] Shibasaki,[12] Hoveyda,[13] and Yun[14] independently developed asymmetric conjugate additions of B2(pin)2 to unsaturated esters, ketones, and thioesters. Hoveyda also developed an efficient copper-catalyzed SN2′ substitution of allylic carbonates by B2(pin)2.[15] Aggarwal has very elegantly exploited enantioselective lithiation followed by the addition of a boronic ester and subsequent rearrangement to prepare chiral tertiary boronic esters bearing benzyl, allyl, propargyl, and most recently all alkyl substituents.[16] Tertiary boronic esters can also be constructed by deborylative alkylation of geminal bis(boronates) as reported by Kingsbury[17] and Morken.[18]

Figure 2.

Recently reported approaches to the synthesis of chiral tertiary boronic esters.

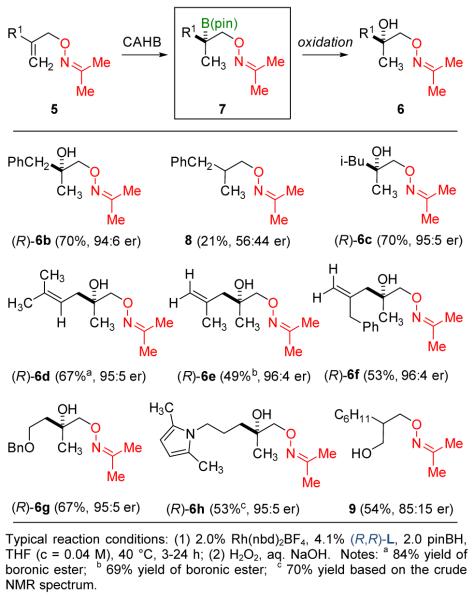

A series of methylidene derivatives 5 in which the vinyl substituent R1 varies were subjected to CAHB (Figure 3). Oxime ether 5b (R1 = CH2Ph) affords the intermediate chiral boronic ester 7b (R1 = CH2Ph) leading to the tertiary alcohol 6b (70%, 94:6 er) after oxidation; alkene reduction leading to 8 (21%, 56:44 er) is the major competing side reaction here and elsewhere. The isobutyl derivative 5c (R1 = CH2CH(CH3)2) reacts similarly giving the tertiary derivative 6c (70%, 95:5 er). Several substrates, in which the R1 substituent contains a second site of unsaturation, were also found to undergo CAHB. It is particularly noteworthy that only the alkene closest to the oxime directing group undergoes borylation in these diene substrates. For example, the 1,4-dienes 5d-f afford monounsaturated alcohols 6d-f after oxidation. Simple pendant oxygen- and nitrogen-substituents are tolerated as illustrated in the formation of 6g and 6h. The level of regioselectivity favoring β- over γ-borylation is high except for substrates in which the vinyl substituent R1 is more sterically demanding. For example, 5i (R1 = cyclohexyl) undergoes predominantly γ-borylation to afford the regioisomeric primary alcohol 9 (54%, 85:15 er) after oxidation.

Figure 3.

CAHB of methylidene substrates 5 leading to the formation of chiral tertiary boronic esters 7.

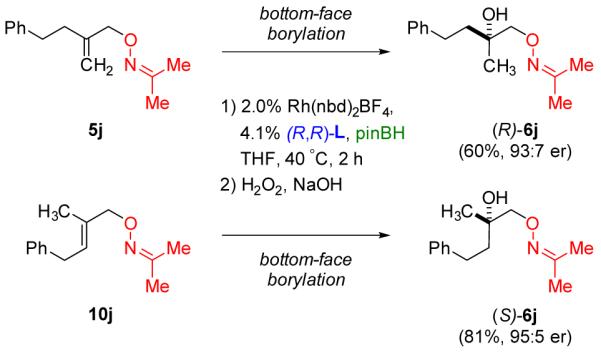

Trisubstituted alkene substrates typically react sluggishly in catalyzed hydroboration but nevertheless readily undergo oxime-directed CAHB. Borane adds to the same π-face as in the corresponding methylidene substrates and therefore yields the enantiomeric tertiary boronic ester intermediate and the enantiomeric tertiary alcohol after oxidation. For example, as shown in Figure 4, CAHB/oxidation of methylidene 5j affords predominantly (R)-6j (60%, 93:7 er); the isomeric trisubstituted substrate 10j affords predominantly (S)-6j (81%, 95:5 er).

Figure 4.

Using the same catalyst system, isomeric methylidene and trisubstituted alkene substrates undergo CAHB with the same π-facial selectivity thus giving the enantiomeric tertiary alcohols after oxidation.

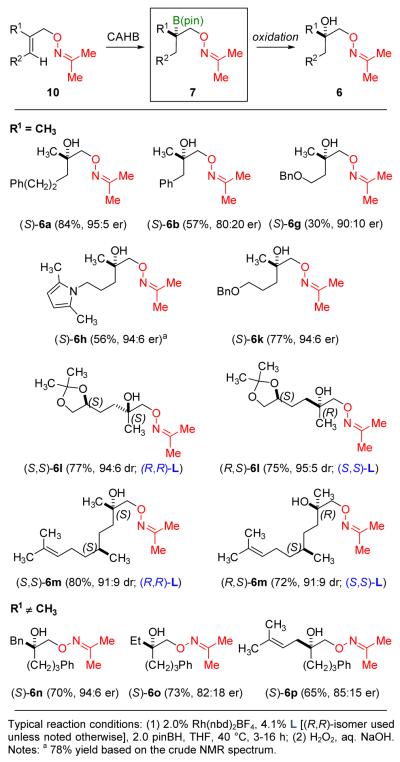

Figure 5 summarizes the results obtained for the oxime-directed CAHB/oxidation of a number of trisubstituted alkene derivatives 10. In addition to giving the opposite enantiomer, the yields obtained with unhindered trisubstituted alkene substrates are often somewhat higher than those obtained for the corresponding methylidene substrates due to less competing alkene reduction. For example, the formation of (S)-6a (84%, 95:5 er) from trisubstituted alkene 10a (R1 = Me, R2 = PhCH2CH2) is a bit higher than the formation of (R)-6a (71%, 95:5 er) from methylidene 5a.[ 19 ] However, in other cases, methylidene substrates react more efficiently. For example, 5b and 5g each undergo oxime-directed CAHB/oxidation to afford (R)-6b (70% 94:6 er) and (R)-6g (67% 95:5 er). The yields and levels of enantioselectivity are somewhat higher than those obtained with the isomeric trisubstituted substrates 10b [(S)-6b (57%, 80:20 er)] and 10g [(S)-6g (30%, 90:10 er)]. In contrast to 10g, substrate 10k in which the benzyl ether substituent resides one methylene group more remote to the site of reaction undergoes CAHB in good yield and high enantioselectivity to give (S)-6k (77%, 94:6 er). A simple nitrogen-containing side chain is again accommodated, as illustrated by CAHB of 10h to (S)-6h (56%, 94:6 er).

Figure 5.

CAHB of trisubstituted alkene substrates 10 leading to the formation of chiral tertiary boronic esters 7.

Trisubstituted alkene substrates bearing remote stereocenters undergo oxime-directed CAHB with good catalyst-controlled diastereoselectivity. For example, the chiral ketal-containing substrate (S)-10l affords either (S,S)- or (R,S)-6l depending on the configuration of the chiral ligand L used in the reaction. Similarly, catalyst-controlled CAHB affords either diastereomer of 6m, again noting that only the proximal alkene in the diene substrate reacts. The examples described thus far all lead to chiral tertiary boronic esters in which one of the substituents is a methyl group. Substrate 10n extends the scope with the formation of (S)-6n (70%, 94:6 er). However, substrates in which the trisubstituted alkene is increasingly congested (e.g., 10o and 10p) tend to react slower and with lower levels of enantioselectivity under the conditions found to date.

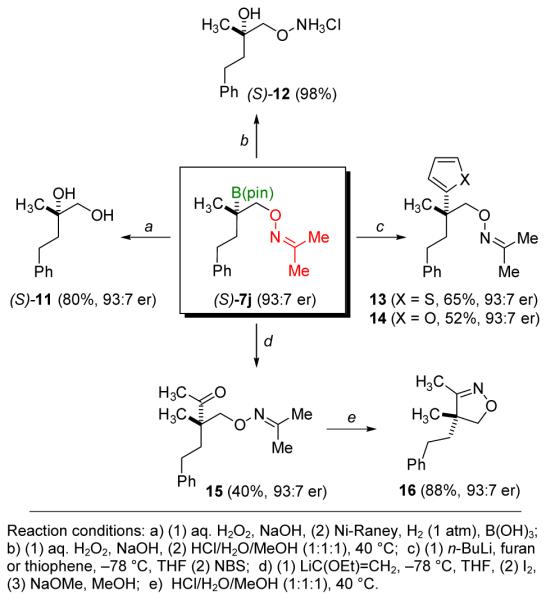

Figure 6 illustrates selected transformations of chiral tertiary boronic ester 7j (93:7 er).[20] Oxidation of the C–B bond followed by cleavage of the N–O bond affords chiral diol 11 (80%, 93:7 er). Alternatively, oxidation followed by hydrolysis affords the chiral O-alkyl hydroxylamine 12 (98%, 93:7 er). Carbon-carbon bond formation is accomplished using the method developed by Aggarwal.[21] Addition of lithiated thiophene or furan followed by electrophile-induced rearrangement of the intermediate borate with retention of configuration affords coupled products 13 and 14 (65% and 53% yield, respectively). A similar sequence using lithiated ethyl vinyl ether followed by hydrolysis affords the keto-oxime 15 with high enantioselectivity, albeit in moderate yield (40%). Nonetheless, treatment with acid gives the chiral 3,4,4-trisubstituted isoxazoline 16 (88%, 93:7 er). 5,5-Disubstituted isoxazolines are found in many natural products and often exhibit diverse biological properties. Hence, isoxazolines are common pharmacophores of interest in medicinal chemistry.[22] The synthesis of 16 constitutes to our knowledge the first reported enantioselective preparation of a 3,4,4-trisubstituted isoxazoline.

Figure 6.

Selected transformations of oxime-containing chiral, tertiary boronic ester 7j.

In summary, asymmetric hydroboration is seemingly an unlikely candidate for the preparation of chiral tertiary boronic esters since hydroboration generally proceeds in an anti-Markovnikov fashion. Nonetheless, we find that unsaturated substrates bearing acetone-derived oxime functionality are excellent substrates for directed-CAHB and yield novel, functionalized tertiary organoboronates with good-to-excellent levels of enantioselectivity. Methylidene and trisubstituted alkene substrates, the latter traditionally considered poor substrates for catalyzed hydroboration, readily undergo oxime-directed CAHB. Borane adds with the same sense of π-facial selectivity in both classes of alkene substrates, and therefore, isomeric substrates yield enantiomeric tertiary boronic esters. A range of substituents are tolerated in the reaction. Of particular note are the findings that substrates bearing remote stereocenters undergo oxime-directed CAHB with good catalyst-controlled diastereoselectivity and that only the proximal alkene undergoes borylation in several diene substrates. The chemistry complements other recently reported methods for the preparation of chiral tertiary boronic esters, particularly for the preparation of organoboronates possessing alkyl, rather than aryl, substituents at the carbon bearing boron. Chiral tertiary boronic esters are versatile synthetic intermediates, and the utility of the chemistry is illustrated by several subsequent transformations. Of particular note is the application of chemistry introduced by Aggarwal for stereoretentive C–C bond formation which we have applied in the enantioselective preparation of a 3,4,4-trisubstituted isoxazoline. Further studies are in progress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support for these studies from the NIH (GM100101) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document.

References

- [1] a).Carroll AM, O’Sullivan TP, Guiry P. J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;347:609–631. [Google Scholar]; b) Crudden CM, Edwards D. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003;24:4695–4712. [Google Scholar]

- [2] a).Zhang L, Zuo Z-Q, Wan X-L, Huang Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:15501–15504. doi: 10.1021/ja5093908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen J, Xi T, Lu Z. Org. Lett. 2014;16:6452–6455. doi: 10.1021/ol503282r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) He Z, Zhao Y, Tian P, Wang C, Dong H, Lin G. Org. Lett. 2014;16:1426–1429. doi: 10.1021/ol500219e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Feng X, Jeon H, Yun J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:3989–3992. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Moteki SA, Toyama K, Liu Z, Ma J, Holmes AE, Takacs JM. Chem. Commun. 2012:263–265. doi: 10.1039/c1cc16146f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Noh D, Yoon SK, Won J, Lee JY, Yun J. Chem. Asian J. 2011;6:1967–1969. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Noh D, Chea H, Ju J, Yun J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6062–6064. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Moteki SA, Takacs JM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:894–897. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Moteki SA, Wu D, Chandra KL, Reddy DS, Takacs JM. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3097–3100. doi: 10.1021/ol061117g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Kwong FY, Yang QT, Mak CW, Chan ASC, Chan KS. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:2769–2777. doi: 10.1021/jo0159542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Schnyder A, Hintermann L, Togni A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1995;34:931–933. [Google Scholar]; l) Togni A, Breutel C, Schnyder A, Spindler F, Landert H, Tijani A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:4062–4066. [Google Scholar]; m) Hayashi T, Matsumoto Y, Ito Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:3426–3428. [Google Scholar]

- [3] a).Hoang GL, Yang ZD, Smith SM, Pal R, Miska JL, Perez DE, Pelter LSW, Zeng XC, Takacs JM. Org. Lett. 2015;17:940–943. doi: 10.1021/ol503764d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yang Z, Pal R, Hoang GL, Zeng XC, Takacs JM. ACS Catal. 2014;4:763–773. doi: 10.1021/cs401023j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Smith SM, Hoang GL, Pal R, Khaled MOB, Pelter LSW, Zeng XC, Takacs JM. Chem. Commun. 2012:12180–12182. doi: 10.1039/c2cc36199j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Smith SM, Thacker NC, Takacs JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3734–3735. doi: 10.1021/ja710492q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Smith SM, Takacs JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1740–1741. doi: 10.1021/ja908257x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Smith SM, Uteuliyev M, Takacs JM. Chem. Commun. 2011:7812–7814. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11746g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4] a).Xu Y, Yan G, Ren Z, Dong G. Nature Chem. 2015;7:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang H, Yu S, Qi Z, Li X. Org. Lett. 2015;17:2812–2815. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ebe Y, Nishimura T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:5899–5902. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Guo K, Chen X, Guan M, Zhao Y. Org. Lett. 2015;17:1802–1805. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Kang T, Kim H, Kim JG, Chang S. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:12073–12075. doi: 10.1039/c4cc05655h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Zhou B, Du J, Yang Y, Feng H, Li Y. Org. Lett. 2014;16:592–595. doi: 10.1021/ol403477w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Xie F, Qi Z, Yu S, Li X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:4780–4787. doi: 10.1021/ja501910e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Yeh C, Chen W, Gandeepan P, Hong Y, Shih C, Cheng C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014;12:9105–9108. doi: 10.1039/c4ob01876a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Yu S, Wan B, Li X. Org. Lett. 2013;15:3706–3709. doi: 10.1021/ol401569u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Chan W, Lo S, Zhou Z, Yu W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13565–13568. doi: 10.1021/ja305771y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k) Hyster TK, Rovis T. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:11846–11848. doi: 10.1039/c1cc15248c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l) Desai LV, Stowers KJ, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13285–13293. doi: 10.1021/ja8045519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Neufeldt SR, Sanford MS. Org. Lett. 2013;15:46–49. doi: 10.1021/ol303003g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Thacker NC, Shoba VM, Geis AE, Takacs JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:3306–3310. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2014.12.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7] a).Matteson DS. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:10009–10023. doi: 10.1021/jo4013942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li L, Zhao S, Joshi-Pangu A, Diane M, Biscoe MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14027–14030. doi: 10.1021/ja508815w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Matthew SC, Glasspoole BW, Eisenberger P, Crudden CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:5828–5831. doi: 10.1021/ja412159g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Buesking AW, Ellman JA. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:1983–1987. [Google Scholar]; e) Zhang C, Yun J. Org. Lett. 2013;15:3416–3419. doi: 10.1021/ol401468v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Mlynarski SN, Karns AS, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem.Soc. 2012;134:16449–16451. doi: 10.1021/ja305448w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Imao D, Glasspoole BW, Laberge VS, Crudden CM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:5024–2025. doi: 10.1021/ja8094075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8] a).Leonori D, Aggarwal VK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:2–17. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Leonori D, Aggarwal VK. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:3174–3183. doi: 10.1021/ar5002473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Scott HK, Aggarwal VK. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:13124–13132. doi: 10.1002/chem.201102581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9] a).Watson CG, Balanta A, Elford TG, Essafi S, Harvey JN, Aggarwal VK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:17370–17373. doi: 10.1021/ja509029h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Marek I, Minko Y, Pasco M, Mejuch T, Gilboa N, Chechik H, Das JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:2682–2694. doi: 10.1021/ja410424g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Burgess K, van der Donk WA. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1994;220:93. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hu N, Zhao G, Zhang Y, Liu X, Li G, Tang W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:6746–6749. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12] a).Chen IH, Yin L, Itano W, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11664–11665. doi: 10.1021/ja9045839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen IH, Yin L, Kanai M, Shibasaki M. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4098–4101. doi: 10.1021/ol101691p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13] a).O’Brien JM, Lee K, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10630–10633. doi: 10.1021/ja104777u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Radomkit S, Hoveyda AH. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:3387–3391. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Feng X, Yun J. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:13609–13612. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].O’Brien M, Lee K, Hoveyda AH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10634–10637. doi: 10.1021/ja104254d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16] a).Stymiest JL, Bagutski V, French RM, Aggarwal VK. Nature. 2008;456:778. doi: 10.1038/nature07592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Bagutski V, French RM, Aggarwal VK. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:5142. doi: 10.1002/anie.201001371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Pulis AP, Aggarwal VK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:7570. doi: 10.1021/ja303022d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Aggarwal VK, Binanzer M, Ceglie M. C. d., Gallanti M, Glasspoole BW, Kendrick SJF, Sonawane RP, Vázquez-Romero A, Webster MP. Org. Lett. 2011;13:1490. doi: 10.1021/ol200177f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Partridge BM, Chausset-Boissarie L, Burns M, Pulis AP, Aggarwal VK. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:11795. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Pulis AP, Blair DJ, Torres E, Aggarwal VK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16054–16057. doi: 10.1021/ja409100y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Watson CG, Aggarwal VK. Org. Lett. 2013;15:1346–1349. doi: 10.1021/ol400289v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wommack AJ, Kingsbury JS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:3163–3166. [Google Scholar]

- [ 18 ].Hong K, Liu X, Morken JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:10581–10584. doi: 10.1021/ja505455z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [ 19 ].(Z)-10a also affords (S)-6a but in somewhat lower yield and lower enantioselectivity (55%, 90:10 er).

- [20].CAHB of 10j was performed on 1.3 mmol scale using lower catalyst loading and higher concentration than described in Figure 4 (0.5% Rh(nbd)2BF4, 1.03% (R,R)-L1, 1.5 pinBH, THF (c = 0.13 M, 40 °C, 7 h) to afford 78% of boronic ester 7j albeit with a slightly lower level of enantioselecivity (93:7 er).

- [21].Bonet A, Odachowski M, Leonori D, Essafi S, Aggarwal VK. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:584–589. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kaur K, Kumar V, Sharma AK, Gupta GK. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014;77:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.