Abstract

We obtained field, K+ selective and “sharp” intracellular recordings from the rat entorhinal (EC) and perirhinal (PC) cortices in an in vitro brain slice preparation to identify the events occurring at interictal-to-ictal transition during 4-aminopyridine application. Field recordings revealed interictal- (duration: 1.1 to 2.2 s) and ictal-like (duration: 31 to 103 s) activity occurring synchronously in EC and PC; in addition, interictal spiking in PC increased in frequency shortly before the onset of ictal oscillatory activity thus resembling the hypersynchronous seizure onset seen in epileptic patients and in in vivo animal models. Intracellular recordings with K-acetate + QX314-filled pipettes in PC principal cells showed that spikes at ictal onset had post-burst hyperpolarizations (presumably mediated by postsynaptic GABAA receptors), which gradually decreased in amplitude. This trend was associated with a progressive positive shift of the post-burst hyperpolarization reversal potential. Finally, the transient elevations in [K+]o (up to 4.4 mM from a base line of 3.2 mM) – which occurred with the interictal events in PC – progressively increased (up to 7.3 mM) with the spike immediately preceding ictal onset. Our findings indicate that hypersynchronous seizure onset in rat PC is caused by dynamic weakening of GABAA receptor signaling presumably resulting from [K+]o accumulation.

Keywords: 4-Aminopyridine, Ictogenesis, Inhibition, [K+]o, Perirhinal cortex, Seizure onset

1. Introduction

Intracranial electroencephalographic recordings obtained from patients with pharmaco-resistant focal epilepsy have identified two main seizure-onset patterns, termed low-voltage fast (LVF) and hypersynchronous (HYP) (Bragin et al., 2005a; Ogren et al., 2009; Perucca et al., 2014; Spencer et al., 1992; Velasco et al., 2000). LVF seizure onset is characterized by the occurrence of a spike followed by low amplitude, fast activity, while HYP onset seizures initiate with a series of rhythmic high-amplitude spikes that are also followed by low amplitude, fast activity. In patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy, LVF seizures have a more diffuse site of origin, and they spread more rapidly and more widely than HYP seizures (Spencer et al., 1992; Velasco et al., 2000). In addition, LVF and HYP seizures in these patients are associated with characteristic patterns of neuronal damage and atrophy in the hippocampal formation (Ogren et al., 2009; Spencer et al., 1992; Velasco et al., 2000).

LVF and HYP seizure onset patterns are also recorded in animal models of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy in vivo (Bragin et al., 2005b; Lévesque et al., 2012) and in experiments aimed at inducing epileptiform synchronization in several in vitro brain preparations by employing different pharmacological procedures (Avoli et al., 1996a, 1996b; Derchansky et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2012; Gnatkovsky et al., 2008). Many of these in vitro studies have been carried out by using the K+ channel blocker 4-aminopyridine (4AP) to enhance neuronal excitability and thus to disclose epileptiform activity. These investigations have revealed that glutamatergic ionotropic neurotransmission is required for ictogenesis but also that GABAA receptor signaling plays a fundamental role in initiating and perhaps sustaining ictal discharges in both limbic and extralimbic structures (see for review: Avoli and de Curtis, 2011). In line with this view, the onset of LVF seizures in the immature hippocampus or in adult para-hippocampal structures in rodents corresponds to a single, “sentinel” spike (Avoli et al., 1996a, 1996b). This spike is mainly generated by GABAA receptor-mediated currents and it is associated with a transient increase in [K+]o, presumably caused by the activity of transporters responsible for reuptake of GABA and Cl− extrusion (Viitanen et al., 2010). Indeed, the increase in [K+]o associated with the “sentinel” spike is consistently larger than what observed during the interictal discharges (Avoli and de Curtis, 2011).

The exact cellular mechanisms underlying HYP seizure onset, however, remain unclear. For instance, Derchansky et al. (2008) reported maintained inhibition during the transition to HYP seizure activity in the isolated immature mouse hippocampus perfused in vitro with low Mg2+ medium. However, a successive study employing a similar model demonstrated that HYP seizure onset is characterized by “exhaustion of presynaptic release of GABA, and unopposed increase in glutamatergic excitation” (Zhang et al., 2012), similar to the condition of “failure of inhibitory restraint” described by Trevelyan et al. (2006) in neocortical slices bathed in low Mg2+. It is also unclear which cellular events occur at the onset of HYP ictal discharges in other models of epileptiform synchronization, and in particular during 4AP application; this drug enhances both excitatory and inhibitory currents (Rutecki et al., 1987; Perreault and Avoli, 1991) while application of low Mg2+ medium – i.e., the pharmacological procedure employed by Derchansky et al. (2008) or Zhang et al. (2012) – is known to progressively reduce inhibition (Whittington et al., 1995; Trevelyan et al., 2006).

LVF onset is the most common in vitro pattern in the adult entorhinal cortex (EC) during 4AP treatment (Avoli et al., 2013) but HYP ictal discharges do occur in the perirhinal cortex (PC) in approx. half of the brain slices (Biagini et al., 2013). Here we addressed the fundamental mechanisms underlying electrographic HYP seizure onset under experimental conditions (i.e., 4AP) that are also capable of inducing ictal discharges with LVF onset features. To this end, we employed field, K+ selective and “sharp” intracellular recordings in extended rat brain slices which included interconnected EC and PC during 4AP application.

2. Materials and methods

Brain slices were obtained from adult Sprague–Dawley rats (200–250 g; Charles River, Canada) following the procedures reported by de Guzman et al. (2004) and in accordance to the guidelines established by the Canadian Council of Animal Care. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and the number of animals used. In brief, animals were decapitated under halothane anesthesia and their brain was quickly removed and placed in cold, oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). A brain tissue block containing the retrohippocampal region was then cut by orienting the top to form an angle of approx. 10° with the stereotaxic horizontal plane, and it was glued top-down to the vibratome holding device. Slices (450–500 μm thick) were transferred into a tissue chamber and positioned at the interface between ACSF and humidified gas (95% O2, 5% CO2) at a temperature of 34 °C and at a pH of 7.4. ACSF composition was (in mM): NaCl 124, KCl 2, KH2PO4 1.25, MgSO4 1.2, CaCl2 2, NaHCO3 26, and glucose 10. To avoid any influence exerted by CA3-driven output activity (cf. de Guzman et al., 2004), we used a razor blade mounted on a micromanipulator to surgically separate the PC–EC from the hippocampus proper (see Fig. 1B); this procedure was performed after having placed the slices in the recording chamber.

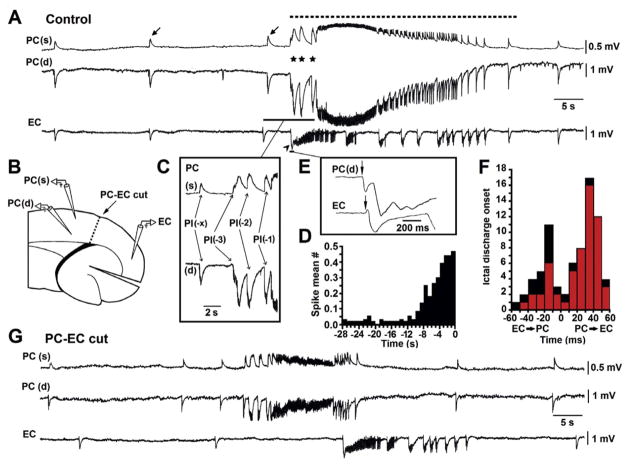

Fig. 1.

Epileptiform activity induced in PC and EC during continuous 4AP application.A: Field potential recordings of interictal and ictal discharges (arrows and dotted line, respectively) occurring synchronously in PC and EC during 4AP application. Note that ictal discharge onset in PC is characterized by a series of 3 field transients (stars) similar to the interictal discharges but of larger amplitude and duration, while in the EC it is associated to a single, large amplitude negative transient (arrowhead). B: Schematic drawing of the brain slice showing the position of the recording electrodes in the PC superficial and deep layers – PC(s) and PC(d), respectively – and in the deep layers of the EC as well as the position of the cut between these two areas. C: Enlargement of the ictal discharge onset recorded in the superficial and depth layers of the PC; the first spike of the series is identified as PI(−x) while the other events are termed PI(−1), PI(−2), etc. according to their temporal relation from the onset of the negative ictal shift. D: Mean number of spikes in the PC before the ictal discharge onset (time 0; n = 58 events from 10 experiments); note that the progressive and consistent increase in spike occurrence during the 8 s epoch that precedes the onset of the overt ictaform activity. E: Magnification of the field recordings obtained from PC(d) and EC at ictal discharge onset in the experiment shown in A; vertical arrows point at the deflections associated to the onset of the first preictal spike and of the single negative transient in PC(d) and EC, respectively. F: Distribution of the delays between ictal events (n = 58) recorded simultaneously from PC and EC and calculated as shown in E; red samples identify ictal discharges that presented with preictal spiking acceleration in PC. Note that most ictal discharges initiate in PC and that the majority of them were associated to this pattern. G: Interictal and ictal discharges occur independently in PC and EC following surgical separation of these two limbic areas. Note that under this experimental condition the isolated PC and EC networks generate ictal discharges that continue to be characterized by onset patterns similar to those seen before the cut. Field recordings in A and G are from the same experiment.

4AP (50 μM) was continuously bath applied from the beginning of the experiment; 3-N[1-(S)-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]amino-2-(S)-hydroxypropyl-P-benzyl-phosphinic acid (CGP 55845; 4 μM), 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX, 10 μM), 3,3-(2-carboxypiperazin-4-yl)-propyl-1-phosphonate (CPP, 10 μM), and picrotoxin (50 μM) were also bath-applied in some experiments. Chemicals were acquired from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), with the exception of CNQX, CPP and CGP 55845 that were obtained from Tocris Cookson (Ellisville, MO, USA).

Simultaneous field potential recordings were performed with glass electrodes filled with 2 M NaCl or ACSF (resistance = 2–10 MΩ), which were positioned in the PC and EC (see Fig. 1B). Signals were fed to high-impedance amplifiers and filtered between DC and 10 KHz. Time-delay measurements of 4AP-induced, synchronous activity recorded from different areas of the brain slice were obtained from expanded traces; in particular, for each trace the onset of the synchronous potentials was determined as the time of the earliest deflection from baseline recording (see Fig. 1E). Sharp-electrode, intracellular recordings were performed in the PC with pipettes filled with either 3 M K-acetate (tip resistance = 70–120 MΩ) or 3 M K-acetate + 50 mM 2-(tri-methyl-amino)-N-(2–6-dimethyl-phenyl)-acetamide (QX-314, a kind gift of Astra, Toronto, ON) (tip resistance = 90–150 MΩ). Intracellular microelectrodes were aimed at depths ranging 500–800 μm from the pia to record from deep PC layer cells. Intracellular signals were fed to a high-impedance amplifier with internal bridge circuit for intracellular current injection. The bridge was monitored throughout the experiment and adjusted as required. Whenever necessary, resting membrane potential (RMP) was kept at a given value with injection of steady intracellular current.

The fundamental electrophysiological parameters of PC neurons included in this study were measured as follows: (i) RMP after cell with-drawal; (ii) input resistance (Ri) from the maximum voltage change in response to a hyperpolarizing current pulse (100–200 ms, < −0.5 nA); (iii) action potential amplitude from baseline. The electrophysiological properties recorded in 4AP-containing ACSF with K-acetate-filled electrodes from deep PC layer cells were: (i) RMP = −73.8 ± 4.8 mV (n = 9), (ii) Ri = 35.1 ± 5.2 MΩ (n = 9), and (iii) action potential amplitude = 92.2 ± 8.3 mV (n = 9). These characteristics were similar to those previously reported by D’Antuono et al. (2001). PC cells could be identified as regularly firing neurons when injected with pulses of intracellular depolarizing current (D’Antuono et al., 2001).

[K+]o measurements in the EC and PC were obtained with double barreled ion-selective electrodes based on the valinomycin ion exchanger Fluka 60,398 (Heinemann et al., 1977; Avoli et al., 1996a, 1996b) using a custom-made high-impedance differential amplier. The ion selective electrode had tip diameters of 2–6 μm. The reference channel was backfilled with 150 mM NaCl, and the ion selective channel with 100 mM KCl. The signal of the reference channel was used both as field potential signal, and as differential signal to the ion channel signal (and hence subtracted from it to yield a “pure” ion signal). In calibration solutions containing 124 mM NaCl and varying concentrations of K+ (1, 3, 10, 30 and 100 mM), the electrode showed a potential change of approx. 58 mV to a tenfold increase in [K+]. Potassium concentration data were obtained by logarithmic fit to the Nernst equation using individual electrode’s steepness, assuming no interference by other ions. In this series of experiments, field potential activity was recorded in the PC and EC through the reference channel of the ion-selective microelectrode. Field potential, [K+]o, and intracellular signals were displayed on Gould chart or WindoGraph recorders.

Ictal activity was defined as an epileptiform event that displayed both tonic- and clonic-like components, and lasted more than 10 s; epileptiform activity lasting less than 4 s was arbitrarily categorized as interictal. Measurements throughout the text are expressed as mean ± SEM, n indicating the number of slices or neurons studied under each experimental procedure. The results obtained were compared using Student’s t-test, ANOVA, or Mann–Whitney Rank Sum test, as indicated, and considered significantly different if p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Electrophysiological and pharmacological characteristics of the epileptiform synchronization induced by 4AP in PC and EC

First, we obtained simultaneous field potential recordings from PC and EC in 14 brain slices during continuous application of 4AP containing medium to characterize the patterns of epileptiform synchronization in these two structures. As shown in Fig. 1A, both interictal and ictal activity (arrows and dotted line, respectively) occurred synchronously in PC and EC within 40 min after the start of 4AP application. Interictal events lasted 1.1 to 2.2 s, recurred every 18–31 s, and originated more often from the EC (310 of 424 discharges analyzed) than from the PC (cf., de Guzman et al., 2004) while ictal events lasted 31 to 103 s and occurred at intervals of 158–316 s. As further detailed below, the PC was the preferred site of ictal discharge onset.

Ictal discharges induced by 4AP in the EC, amygdala or insular cortex (Avoli et al., 1996a, 2013; Benini et al., 2003; Sudbury and Avoli, 2007) initiate with a single, large amplitude transient similar to an interictal event; this “sentinel” spike leads to a tonic-like phase making this electrographic pattern resemble an LVF seizure onset. We consistently observed this type of ictal onset in the EC in the present experiments as well (n = 14; arrow-head in Fig. 1A). In contrast, LVF seizure onset occurred in the PC only in 5 out of 14 slices. In this structure, the majority of ictal discharges (56 out of 75 of all events, see also below) initiated with a series of 3–6 field events that increased progressively in rate of occurrence and/or amplitude until the appearance of tonic-like oscillatory activity at approx. 20 Hz that was associated with negative and corresponding positive shifts in field recordings obtained from the deep and superficial PC layers, respectively (Fig. 1A); these shifts presumably mirror [K+]o accumulation versus site of spatial buffering, which in turn should account for variable onsets and/or amplitudes of these phenomena (Dietzel et al., 1989).

This type of ictal discharge onset resembled a HYP seizure onset, and it will be hereafter termed preictal spiking acceleration. In addition, for further intracellular and [K+]o analyses, we classified its components as follows: (i) we marked the first preictal spike of the series as PI(−x) and (ii) termed the other preictal events as PI(−1), PI(−2), etc. according to their temporal relation from the onset of the negative ictal shift (Fig. 1C). The mean number of spikes recorded from the PC before the onset (time 0) of tonic-like oscillatory activity in 56 ictal discharges (from 10 experiments) is summarized in Fig. 1D; this plot indicates that spike occurrence progressively and consistently increased during the period of 8 s that preceded the negative shift marking the beginning of the tonic-like oscillatory activity.

Next, we analyzed in these 14 experiments the site of ictal discharge onset by establishing the initial deflection of the field potential(s) leading to the tonic-like oscillatory activity (Fig. 1E). This deflection usually corresponded to the “sentinel” spike or to the first of the preictal spikes in LVF or HYP-onset discharges, respectively. As illustrated in Fig. 1F, the majority (i.e., 77.3%) of ictal discharges initiated in the PC. Moreover, events with ictal discharges originating in PC significantly correlated to preictal spiking acceleration (red plot samples in Fig. 1F; p = 0.008; Mann–Whitney Rank Sum Test). Thus 91.8% of the ictal discharges initiating in PC were characterized by this pattern, which in turn occurred in only 50% of the ictal discharges when these originated in the EC. Surgical separation of the EC from the PC (n = 4 experiments; see diagram in Fig. 1B) made both interictal and ictal discharges occur independently in these two limbic areas (Fig. 1G) (cf., de Guzman et al., 2004). The ability of isolated PC and EC networks to generate ictal discharges continued to be associated to similar patterns of initiation.

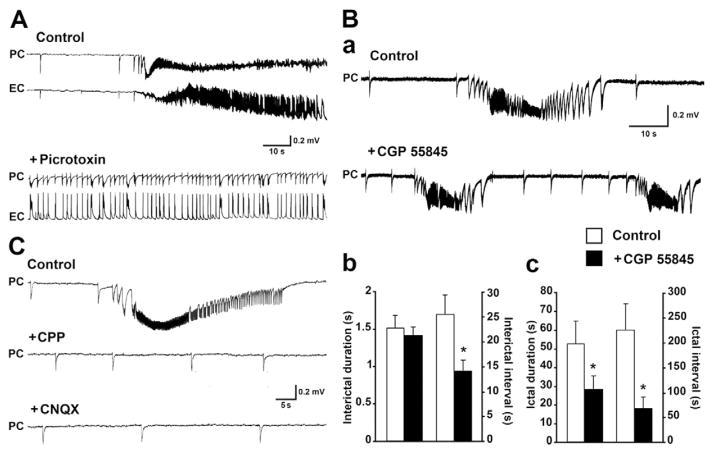

As previously reported in several studies (cf., Avoli and de Curtis, 2011), the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxin (50 μM; n = 5 slices) abolished 4AP-induced ictal discharges in both EC and PC, and it disclosed a continuous pattern of short-lasting epileptiform discharges (duration = 2.2 ± 0.4 s) which recurred regularly at intervals of 2.5 ± 0.6 s (n = 5) (Fig. 2A). Given the possible role played by presynaptic GABAB receptors in HYP seizure onset (Zhang et al., 2012), we an-alyzed the effects induced by the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 55845 (4 μM); however, interictal and ictal activity along with the preictal spiking acceleration continued to occur in the PC during this pharmacological treatment (n = 5 slices; Fig. 2B, panel a), even though at higher frequencies, and with shorter durations at least for the ictal events (Fig. 2B, b and c). Finally, as reported in previous studies (cf., Avoli et al., 1996a, 1996b; de Guzman et al., 2004) we found that application of the NMDA receptor antagonist CPP (20 μM; n = 8 slices) abolished the occurrence of ictal discharges, while interictal events continued to occur with similar intervals (27.0 ± 4.4 s in control versus 24.8 ± 4.3 s) and durations (1.6 ± 0.3 s in control versus 1.5 ± 0.3 s); this interictal activity was not influenced by successive, concomitant application of the non-NMDA receptor antagonist CNQX (20 μM; n = 6 slices), as it occurred at intervals of 25.3 ± 5.0 s and had durations of 1.4 ± 0.1 s (Fig. 2C) (cf., Avoli and de Curtis, 2011).

Fig. 2.

Pharmacological properties of 4AP-induced epileptiform activity. A: Effects induced by the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxin (50 μM) on the epileptiform activity simultaneously recorded from the PC and EC; note that ictal discharges are abolished by this pharmacological procedure while a continuous pattern of robust interictal activity is disclosed in both areas. B: Field recordings obtained from the PC under control conditions (i.e., 4AP continuous application) and in the presence of the GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 55845 (4 μM) are shown in a; note that interictal and ictal events continue to occur but more frequently than in control during GABAB receptor blockade as well as the pattern of preictal spiking acceleration occurs at ictal discharge onset in both experimental conditions. Quantification of the duration and of the interval of occurrence of interictal and ictal discharges under control conditions and during CGP 55845 application are shown in b and c, respectively. Data were obtained from 5 experiments; asterisks identify statistical significance. C: Effects induced on the epileptiform activity generated by the PC by the NMDA receptor antagonist CPP (20 μM) and by successive, concomitant application of the non-NMDA receptor antagonist CNQX (20 μM); note that CPP abolishes ictal discharge while interictal events continue to occur even when CNQX is added to the superfusing medium.

3.2. Intracellular characterization of interictal–ictal transition in the PC

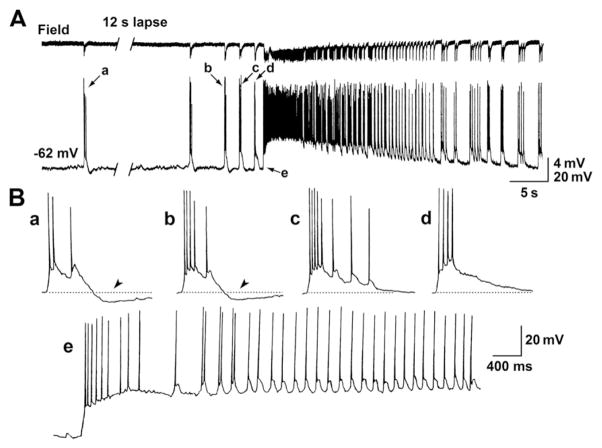

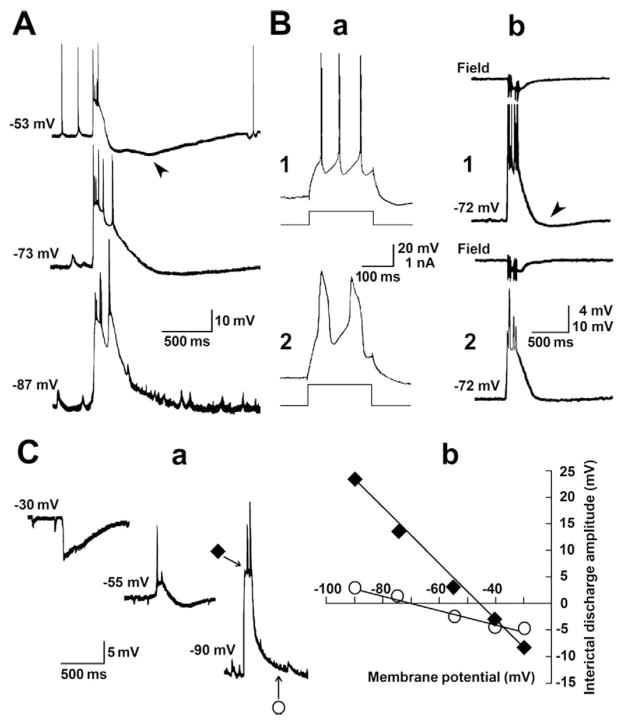

Next, we obtained intracellular recordings with K-acetate-filled electrodes from 9 PC regularly firing cells in brain slices in which ictal discharge initiation was characterized by preictal spiking acceleration during application of 4AP. The intracellular counterpart of the interictal discharges consisted of a depolarization from RMP, which triggered a burst of action potentials followed by a hyperpolarizing potential (Fig. 3, Aa and Ba as well as Fig. 4A). Injection of steady hyperpolarizing or depolarizing current modified the amplitude of the different components of these intracellular interictal discharges as expected for synchronous events that are mainly generated by synaptic conductances, and a biphasic long lasting hyperpolarization was disclosed during injection of steady depolarizing current (Fig. 4A); previous work has shown that the early and late phase of this hyperpolarization reflect the postsynaptic activation of GABAA and GABAB receptors, respectively (Nicoll et al., 1990). Preictal spiking acceleration recorded from these 9 PC cells corresponded to a decrease of this post-burst hyperpolarization (arrowheads in Fig. 3B), which usually coincided with a more intense action potential bursting leading to the sustained firing seen during the ictal oscillatory discharge.

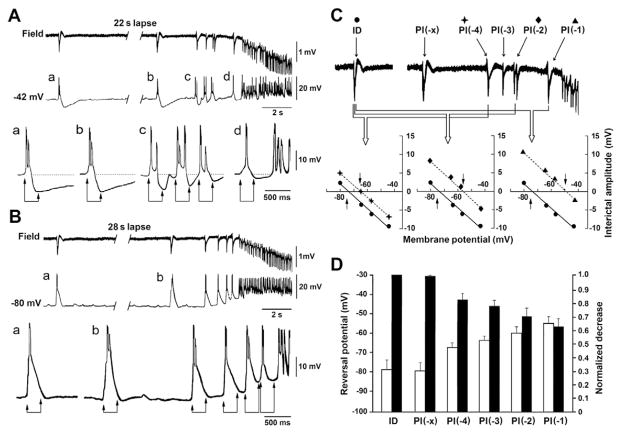

Fig. 3.

Intracellular characterization of the interictal to ictal transition in PC cells recorded with K-acetate-filled electrodes. A: Simultaneous field potential and intracellular recordings of spontaneous epileptiform discharges induced by 4AP in the PC; interictal spikes and an ictal discharge characterized by preictal spiking acceleration onset are shown. The intracellular signal was obtained with a K-acetate-filled microelectrode from a regularly firing PC neuron. Note that the intracellular counterpart of the interictal discharges (a) consists of a depolarization that triggers action potential burst and is followed by a hyperpolarizing potential. B: Selected portions of the recordings shown in A (which are identified with lower case letters) are reproduced at faster time base to illustrate that preictal spiking acceleration is characterized by a progressive decrease in the amplitude of the post-burst hyperpolarizations (arrow heads) coinciding with more intense action potential bursting. Note also that these changes appear to lead to the sustained firing seen during the ictal discharge (e).

Fig. 4.

Intracellular characterization of the 4AP-induced interictal discharges generated by PC neurons. A: Interictal discharges recorded intracellularly with a K-acetate-filled microelectrode from a PC neuron that was held at different membrane potentials by injecting steady hyperpolarizing or depolarizing current. RMP = −73 mV. Note that a biphasic long lasting hyperpolarization is seen when the membrane potential is set at −53 mV; the arrowhead points at the late component of the hyperpolarization. B: Intracellular recordings obtained with K-acetate + QX-314-filled microelectrode shortly after impalement (1) and 22 min later (2). Responses to intracellular pulses of depolarizing current and interictal events are illustrated in a and b, respectively. In b the field potential recorded simultaneously from a microelectrode positioned in the PC deep layers is also shown (Field). Note that fast action potentials (1a) are later replaced by slow spikes presumably representing Ca2+ dependent events (2a) as well as that similar changes can be seen with the action potentials riding over the interictal intracellular depolarizations that are illustrated in 1b and 2b panels. Note also that the slow, presumably GABAB mediated hyperpolarization (arrowhead in 1b) is reduced over time during the recording. Action potentials in 1b are truncated. C: Effects induced by varying the membrane potential with intracellular current injection in a PC neuron recorded with K-acetate + QX-314-filled microelectrode. RMP of this neuron was −74 mV. Note in a that the interictal depolarization becomes hyperpolarizing at membrane potentials less negative than −45 mV while injection of hyperpolarizing current increases the interictal depolarization and abolishes the post-burst hyperpolarizing potential. Plot of the membrane values obtained 50 (diamond) and 450 ms (open circle) after interctal discharge onset are shown in b. Extrapolated reversal potentials of −44 mV and −72 mV were obtained for the initial and late components of the intracellular interictal events recorded from this PC neuron.

To better identify the changes in post-burst hyperpolarization occurring during preictal spiking acceleration, we used K-acetate-filled electrodes containing QX-314. In addition to blocking voltage-gated Na+ channels (and thus action potential firing, Connors and Prince, 1982), QX-314 abolishes GABAB receptor-mediated hyperpolarizations (Nathan et al., 1990) along with Ih (Perkins and Wong, 1995), thus allowing a better estimation of the changes seen when the membrane polarization is modified with intracellular current injection. As illustrated in Fig. 4Ba, depolarizing current pulses (200 to 300 ms, 0.2–1 nA) applied shortly after the start of the recording (with K-acetate + QX-314-filled electrodes) induced fast action potentials, which were later replaced by slow intracellular spikes that presumably represented Ca2+ dependent regenerative events (Galvan et al., 1985); similar changes also occurred over time for the action potentials riding over the interictal depolarizations (Fig. 4Bb). In addition, in all experiments (n = 10), QX-314 was able to reduce the slow, presumably GABAB mediated hyperpolarization (arrowhead in Fig. 4Bb). In 7 neurons, we analyzed the amplitude changes of the interictal depolarizations induced by varying the membrane potential with intracellular current injection. As shown in Fig. 4C, interictal depolarizations decreased in amplitude during injection of depolarizing current and became hyperpolarizing at membrane potentials more positive than −45 mV; conversely, injection of hyperpolarizing current increased the interictal depolarizing envelope thus making the post-burst late hyperpolarizing component disappear. Extrapolated reversal potentials of −40.4 ± 5.9 mV and −80.3 ± 4.8 mV (n = 7) were obtained for the initial and late components of the intracellular interictal event (as gauged 50 and 450 ms after discharge onset) (Fig. 4C), suggesting the possible involvement of GABAA receptor-mediated currents along with intrinsic currents such as voltage-gated or Ca2+-activated K+ currents.

As illustrated in Fig. 5, the transition from interictal to ictal activity in these PC neurons was characterized by preictal spiking acceleration corresponding to a progressive decrease of the post-burst hyperpolarization with events that occurred closer to the onset of the ictal oscillatory activity. Analysis of the reversal potential of these post-burst hyperpolarizations (approx. 400 ms after the onset of each preictal event) in 7 PC neurons recorded with K-acetate + QX-314-filled electrodes, revealed that it had similar values when the first preictal discharge, identified as PI(−x), was compared with that identified in spikes occurring during the interictal stage. However, this reversal potential progressively, and significantly (p < 0.001, Student’s t-test, interictal versus preictal discharges) shifted to more positive values as the preictal spikes occurred closer to the onset of ictal activity (Fig. 5C and D); specifically, the reversal potentials of the post-burst hyperpolarizations seen during PI(−x) and PI(−1) were −80.0 ± 3.9 and −55.4 ± 2.4 mV, respectively, indicating a positive shift of about 25 mV.

Fig. 5.

Intracellular characterization of the interictal to ictal transition in PC cells recorded with K-acetate + QX-314-filled microelectrodes. A and B: Simultaneous field potential and intracellular recordings obtained from the PC at the transition from interictal to ictal discharge; intracellular signals were obtained from a PC neuron that was recorded with K-acetate + QX-314-filled electrode and set to depolarized (−42 mV, A panel) and hyperpolarized (−80 mV, B panel) membrane values. RMP of this neuron was −66 mV. In both A and B, selected portions of the intracellular recordings shown on top, and identified with lower case letters, are reproduced at a faster time base below to illustrate in detail the progressive changes in the post-burst hyperpolarizations occurring progressively during the preictal spiking when the membrane is set at a depolarized level. C: A progressive shift of the reversal potential of the post-burst hyperpolarization to less negative values characterize the transition from interictal to ictal activity. Top field recording highlights the transition and defines the events as interictal (ID) and preictal discharges (PD) according to the terminology established in Fig. 1 legend. Plots shown below illustrate the shift of the reversal potential of the post-burst hyperpolarizations in the experiment shown in A and B; values were computed 450 ms after the onset of each preictal event. D: Changes in the reversal potential of the post-burst hyper-polarization during interictal to ictal transition in 7 PC cells recorded with K-acetate + QX-314-filled electrodes. Absolute and normalized values of the reversal potential are given in the white and black columns. Note that similar values are seen when the first preictal discharge (PI(−x)) was compared with the interictal discharge (ID) as well as that a progressive and significant (p < 0.001, Student’s t-test, ID versus PI(−4) to PI-1) shift to more positive values occurs.

3.3. Increases in [K+]o associated to epileptiform discharges recorded in the PC

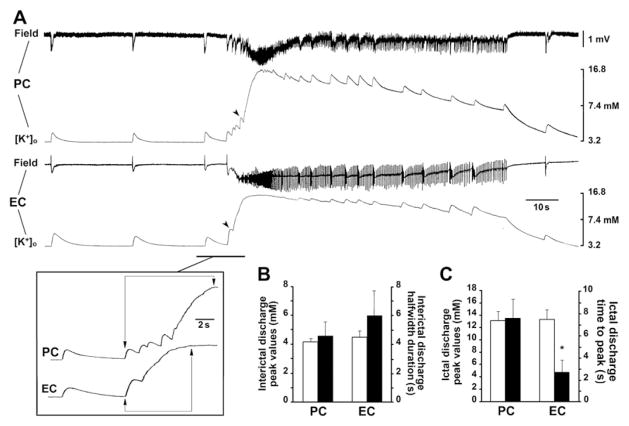

Previous experiments have shown that interictal discharges recorded in the EC during 4AP application are associated with transient elevations in [K+]o that are mainly contributed by the postsynaptic activation of GABAA receptors (Avoli et al., 1996a). It has also been proposed in this study that these elevations in [K+]o should represent a causative factor in ictal discharge initiation in the EC (cf., Avoli and de Curtis, 2011). Therefore, in 6 experiments, we employed simultaneous field and [K+]o recordings in the PC and EC during 4AP application. As illustrated in Fig. 6A and B, interictal spikes recorded from the PC and EC were associated with transient increases in [K+]o that had similar amplitudes (i.e., peak values of 4.17 ± 0.17 and 4.41 ± 0.43 mM from a resting level of approx. 3.2 mM in PC and EC, respectively) and kinetics values (i.e., half-width duration of 4.6 ± 1.3 and 5.9 ± 1.9 s in PC and EC, respectively). In addition, as previously reported in several in vitro and in vivo models of epileptiform synchronization (Avoli and de Curtis, 2011; Heinemann et al., 1977, 1986), [K+]o in PC and EC increased to values larger than 12 mM during ictal activity. Specifically, we found similar peak values in the two areas (i.e., 13.2 ± 1.6 and 14.0 ± 1.8 mM in PC and EC, respectively). However, while [K+]o rose briskly in EC, it gradually increased in PC, concomitant to the appearance of the pattern of preictal spiking acceleration (see also insert in Fig. 6A); accordingly, time to peak during ictal discharge in PC was 7.7 ± 2.1 s while in EC was 2.75 ± 1.2 s (p < 0.001, Student’s t-test) (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Increases in [K+]o associated to epileptiform discharges recorded in PC and EC. A: Simultaneous field and [K+]o recordings obtained in the deep layers of PC and EC during 4AP application. In both limbic areas interictal and ictal discharges are associated to similar transient increases in [K+]o. Note also in the insert that while [K+]o rises briskly in the EC, it gradually increased in PC, concomitant to the appearance of preictal spikes; ictal discharge onset in PC and EC occur when [K+]o rises in excess of 6.3 mM (arrowheads). B: Quantification of the peaks and halfwidth durations of the [K+]o elevations associated to interictal discharges in PC and EC. C: Quantification of the peaks and of the time to peak of the increase in [K+]o associated to ictal discharges in PC and EC. The time to peak was measured as indicated in the insert in panel A. Asterisk indicates p < 0.001. Data were obtained from 6 different slices.

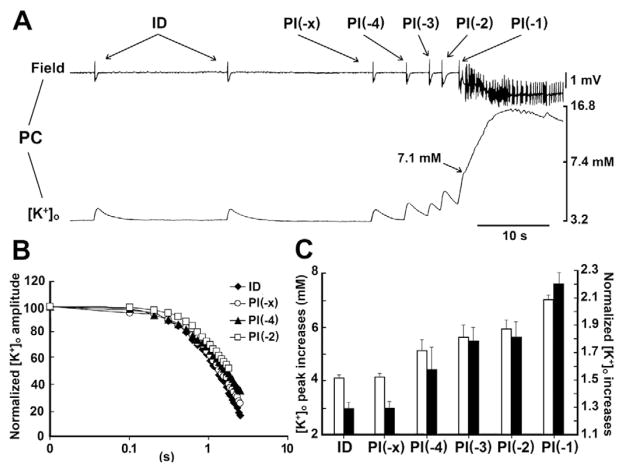

We focused therefore on the changes in [K+]o that occur in the PC during the transition from interictal to ictal discharge. In line with previous studies performed in the EC (Avoli et al., 1996a) and in the juvenile hippocampus (Avoli et al., 1996b), the initiation of ictal discharge in PC was set on when [K+]o rose in excess of 6.3 mM. However, while this value was attained in EC with the single spike initiating the ictal discharge (arrowhead in Fig. 6A), [K+]o rises in PC summated with each preceding preictal event to reach the critical threshold value (usually with the fourth or fifth preictal spike) (Figs. 6A and 7A). As illustrated in Fig. 7, we found that these preictal elevations in [K+]o were larger than those associated to the interictal events (p < 0001, Student’s t-test). In addition, statistical comparison of the preictal increase in [K+]o demonstrated that this increase usually started only with the last four pre-ictal events, i.e. roughly within the last 5 s before an ictal event (Fig. 7C). These findings were presumably not due to a reduced K+ uptake capacity, as [K+]o kinetics were similar with each preictal spike (Fig. 7B), but rather caused by the temporal coding of the preictal events (Fig. 7A). Thus, as shown in Fig. 7A, even though discernible peaks emerged with each preictal spike and kinetics remained constant, [K+]o during successive preictal spikes could never return to baseline.

Fig. 7.

Increases in [K+]o occurring in the PC during preictal spiking. A: Interictal and ictal activity recorded with simultaneous field and K+ selective electrodes in the PC during 4AP application. Note that the [K+]o elevations associated to the preictal spikes (PI(−x) to PI(−1)) become progressively larger than those associated to interictal discharges (ID). B: Time decay of the increases in [K+]o associated to the interictal discharges and to selected preictal events recorded in the experiments shown in A; note that interictal and preictal spikes show similar [K+]o kinetics. C: Absolute and normalized values of the peak increases in [K+]o associated to interictal discharges and to preictal spikes defined as established in Fig. 1 legend. Note the progressive increase as well as that values for PI(−4) to PI(−1) are significantly different from those seen with ID as well as with PI(x). (p < 0001, Student’s t-test). Data were obtained from 40 ictal discharges recorded during 11 experiments.

4. Discussion

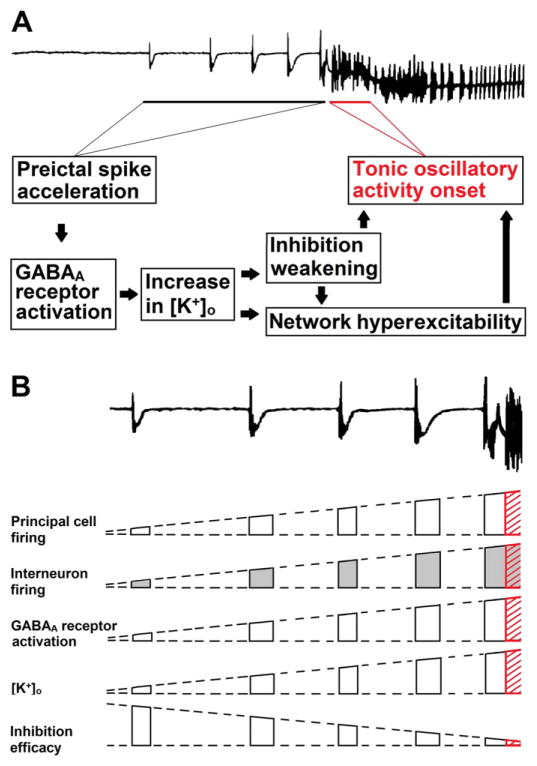

The main findings of our study are as follows. First, 4AP-induced ictal discharges recorded in vitro from the EC and PC present with electrographic patterns resembling LVF and HYP seizure onsets, respectively; these seizure onset types can occur in vivo both in epileptic patients and in animal models. Second, the post-burst hyperpolarizations (presumably representing GABAA receptor signaling) recorded from PC principal cells during the preictal spiking acceleration seen with the HYP pattern is accompanied by a progressive decrease in amplitude along with a positive shift in its reversal potential. Finally, such dynamic weakening in inhibition is mirrored in PC by transient elevations in [K+]o that increase during preictal spiking acceleration reaching values as high as 7.3 mM with the spike immediately preceding the onset of tonic ictal activity. The results obtained from experiments in which HYP onset pattern was generated by PC networks during 4AP treatment are summarized and further elaborated in the block diagrams of Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Schematic block diagram of the main events occurring during HYP seizure onset. A: Mechanistic overview of the transition from preictal spike acceleration to the occurrence of tonic oscillatory activity. Block diagrams highlight the activation of GABAA receptors that coincides with the repetitive preictal spikes, and causes an increase in [K+]o that weakens inhibition and makes networks hyperexcitable. B: Diagramatic, “semiquantitative” summary of the dynamic changes in principal cell and interneuron firing, amount of GABAA receptor activation, [K+]o and inhibition efficacy within the network during the preictal spike acceleration that leads to the tonic oscillatory activity of the electrographic seizure-like discharge (highlighted in red). Note that the interneuron firing is shaded in gray since it is the only presumptive parameter as no actual recordings from inhibitory cells were performed in our study. Top field recordings in A and B were redrawn from the experiment shown in Fig. 7A.

4.1. LVF and HYP seizure onset patterns in vitro

We found that contrary to what occurring in EC, in which ictal discharges are often preceded by a single “sentinel” spike evolving into a tonic-like event (Avoli et al., 1996a, 2013), ictal activity onset in the PC is often characterized by a build-up of hypersynchronous spikes (Biagini et al., 2013) defined here as preictal spiking acceleration. These in vitro electrographic features recapitulate those seen in LVF and HYP onset seizures occurring in patients with pharmaco-resistant focal epilepsy (Bragin et al., 2005a; Ogren et al., 2009; Perucca et al., 2014; Spencer et al., 1992; Velasco et al., 2000) and in in vivo animal models (Bragin et al., 2005b; Lévesque et al., 2012). Both the EC and PC belong to the limbic system that is known to be closely involved in the pathophysiogenesis of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (Gloor, 1997).

The two seizure onset patterns could coexist in the EC and PC of intact combined brain slices, in which ictal discharges occurred synchronously in these two structures. Moreover, ictal discharges initiating in PC and propagating to EC were consistently associated to HYP characteristics suggesting that, at least in the in vitro 4AP model, the HYP onset may identify the site of ictal activity initiation. This, and perhaps even the fact that interictal spikes appear to be more readily generated in EC (de Guzman et al., 2004) may reflect, in turn, a greater excitability in the site generating primarily such LVF onsets, i.e., the EC. Irrespective of whether the EC is more excitable than the PC, the two seizure onset patterns persisted in each structure following their surgical separation suggesting that they mirror specific regional network properties; nonetheless, robust inhibitory potentials could be recorded in vitro from EC or PC principal cells at the onset of LVF (Lopantsev and Avoli, 1998) or HYP (present experiments) seizures, respectively. Therefore, these findings indicate that different interactions between interneurons and principal cells occur in these two areas thus leading to the two onset types. A different tune of inhibitory function in temporal neocortex-PC pathways as compared to the EC to PC pathways has been indeed identified (Garden et al., 2002; de Curtis and Paré, 2004; Woodhall et al., 2005). In spite of different onset patterns, NMDA receptor antagonism abolished ictal discharges in EC and PC, and it disclosed interictal activity occurring synchronously in both areas. In addition, ictal discharges were changed in both structures into a continuous pattern of robust interictal activity during blockade of GABAA receptors; this evidence further underscores the role of GABAA receptor signaling in ictogenesis as proposed by studies performed in several limbic and paralimbic structures (Avoli and de Curtis, 2011) as well as in the neocortex (Trevelyan et al., 2006; Trevelyan, 2009). Our data are, however, at odds with those obtained in the CA3 region of the in vitro intact mouse hippocampus during application of low Mg2+ medium (Zhang et al., 2012); these investigators reported that GABAA receptor antagonism did not influence ictogenesis. This variance may result from the two different pharmacological procedures used to disclose epileptiform activity, different animal structure/species and from the different ages of the animals that in the study by Zhang et al. (2012) were 6 to 12 day-old. Finally, following blockade of NMDA and non-NMDA glutamatergic receptors, PC networks continued to generate interictal events that had similar rates of occurrence and duration as those recorded under similar pharmacological condition from the EC (Avoli et al., 1996a, 2013) suggesting that glutamatergic-independent synchronization disclosed by 4AP has similar characteristics in these two limbic structures.

4.2. Weakening of post-burst hyperpolarizations and GABAA receptor-dependent increases in [K+]o lead to ictal discharge onset

We have found that preictal spiking acceleration corresponds in PC principal cells to a progressive decrease of the post-burst hyperpolarization up to the onset of the overt tonic component of the ictal discharge. By using K-acetate + QX-314-filled microlectrodes we have identified a progressive, positive shift of ~25 mV in the reversal potential of these post-burst hyperpolarizations that presumably reflected postsynaptic GABAA receptor signaling since intracellular QX-314 abolishes GABAB receptor-mediated post-synaptic inhibition (Nathan et al., 1990; Jensen et al., 1993). Therefore, we are inclined to conclude that the progressive weakening of GABAA receptor signaling, which in turn uncovers glutamatergic currents, coincides with the preictal spiking acceleration and thus with HYP seizure onset. In addition, these preictal changes corresponded to progressive increases of the peaks in [K+]o until the critical threshold value (> 7.0 mM) for the occurrence of tonic ictal activity was reached. These summating preictal elevations in [K+]o may originate from the close temporal coding of the preictal spikes rather than from a reduced K+ uptake capacity. Previous studies have indeed shown that the GABAA receptor-mediated IPSP reversal potential is shifted to less polarized values by applying medium containing [K+] similar to those recorded in our study with sensitive electrodes (Jensen et al., 1993; Korn et al., 1987; Thompson and Gähwiler, 1989). Therefore, the dynamic weakening of the post-burst hyperpolarizations recorded during HYP onset pattern may be caused by the concomitant increased in [K+]o. This is further corroborated by a study by Viitanen et al. (2010), where GABA-receptor activation was shown to be linked to increased Cl− influx, and in turn to increased K+-Cl− extrusion via the cotransporter KCC2. In line with a potential “pro-epileptic” role played by KCC2 activity, our group has recently reported that blockade of this co-transporter reduces epileptiform synchronization (Hamidi and Avoli, 2015). Therefore, we propose that these increases in [K+]o mainly result from the postsynaptic activation of GABAA receptors, as more closely discussed in the following paragraph.

A major contribution of GABAA signaling to [K+] elevation stems from previous studies in which we showed that: (i) interictal spikes that are abolished by glutamatergic receptor antagonists are accompanied by [K+] increases that are lower than those seen during interictal spikes mainly contributed by GABAA receptor activation (Avoli et al., 1996a; Barbarosie et al., 2000) and (ii) application of glutamatergic receptor antagonists does not decrease these [K+]o elevations (Avoli et al., 1996a, 1996b). Barolet and Morris (1991) were the first to find that activation of GABAA receptors causes per se increases in [K+]o. Later these findings have been explained as due to the activity of the cotransporter KCC2, which is exclusively expressed in the mature brain and is the main extruder of Cl− from neurons Viitanen et al. (2010). At the best of our knowledge, LVF onset ictal discharges in vitro can only be recorded during application of 4AP; the start of these ictal events coincides with a synchronous (“sentinel”) spike that is contributed by GABAA receptor currents and is associated to sizeable increases in [K+]o (Avoli and de Curtis, 2011; see also EC recordings in Fig. 7A). In contrast, HYP onset events can be reproduced under different conditions including rodent hippocampal slices bathed in high K+ medium (Traynelis and Dingledine, 1988; Jensen and Yaari, 1988), the low Mg2+ model in the immature mouse hippocampus (Derchansky et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2012), and the human subiculum kept alive in a brain slice preparation during perfusion with low Mg2+/high K+ medium along with alkalinization (Huberfeld et al., 2011). Different cellular and pharmacological mechanisms have been proposed in these studies to underlie HYP onset ictal events; such diversity is indeed expected since HYP onset result from a variety of experimental procedures and in vitro brain preparations.

It is relevant that in our experiments, by using the same pharmacological manipulation (i.e., application of the K+ channel blocker 4AP) we have found here that ictal discharges with LVF and HYP onset characteristics can coexist in two limbic areas. Moreover, our data show that the first spike of the preictal series has electrophysiological and pharmacological features that are similar to those of the spikes occurring between ictal discharges. Thus our data indicate that synaptic inhibition in this model is maintained up to the ictal discharge onset but that its efficacy progressively decreases during pre-ictal acceleration (Fgi. 7B). Although this phenomenon may be contributed by “exhaustion of presynaptic release of GABA” (Zhang et al., 2012), we are inclined to suggest that the progressive ‘overpowering’ excitation during preictal spiking acceleration results from a weakening of GABAA receptor signaling mainly caused by transient, summating elevations in [K+]o. This view is supported by our experiments in which we continued to observe HYP seizure onset during blockade of GABAB receptors.

5. Conclusions

As summarized in Fig. 8, our results strongly suggest that HYP seizure onset in the PC of rodent slices maintained in vitro is associated with a dynamic weakening of GABAA receptor signaling that results from [K+]o accumulation caused paradoxically by the activation of GABAA receptors and to the subsequent increase in KCC2 activity. Interestingly, we have recently found that 4AP-induced ictal discharges recorded in vitro from the piriform cortex or the EC are abolished or facilitated by inhibiting or enhancing KCC2 activity, respectively (Hamidi and Avoli, 2015). In conclusion, at least in the in vitro 4AP model, both LVF and HYP onset ictal discharges appear to depend on periodic excessive function of inhibition. This view in line with in vivo studies performed in epileptic patients (Schevon et al., 2012; Truccolo et al., 2011) and in animal models (Grasse et al., 2013; Toyoda et al., 2015) in which sustained firing of interneurons at seizure initiation has been identified.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR grants 8109 and 74609), from the Savoy Foundation to MA and from the BfArM V-14415/68502/2011-2014 to RK.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Avoli M, de Curtis M. GABAergic synchronization in the limbic system and its role in the generation of epileptiform activity. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95:104–132. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Barbarosie M, Lücke A, Nagao T, Lopantsev V, Köhling R. Synchronous GABA-mediated potentials and epileptiform discharges in the rat limbic system in vitro. J Neurosci. 1996a;16:3912–3924. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Louvel J, Kurcewicz I, Pumain R, Barbarosie M. Extracellular free potassium and calcium during synchronous activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in the juvenile rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1996b;493:707–717. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Panuccio G, Herrington R, D’Antuono M, de Guzman P, Lévesque M. Two different interictal spike patterns anticipate ictal activity in vitro. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;52:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarosie M, Louvel J, Kurcewicz I, Avoli M. CA3-released entorhinal seizures disclose dentate gyrus epileptogenicity and unmask a temporoammonic pathway. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:1115–1124. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barolet AW, Morris ME. Changes in extracellular K+ evoked by GABA, THIP and baclofen in the guinea-pig hippocampal slice. Exp Brain Res. 1991;84:591–598. doi: 10.1007/BF00230971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benini R, D’Antuono M, Pralong E, Avoli M. Involvement of amygdala networks in epileptiform synchronization in vitro. Neuroscience. 2003;120:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biagini G, D’Antuono M, Benini R, de Guzman P, Longo D, Avoli M. perirhinal cortex and temporal lobe epilepsy. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:130. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, Wilson CL, Fields T, Fried I, Engel J., Jr Analysis of seizure onset on the basis of wideband EEG recordings. Epilepsia. 2005a;46(Suppl 5):59–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A, Azizyan A, Almajano J, Wilson CL, Engel J. Analysis of chronic seizure onsets after intrahippocampal kainic acid injection in freely moving rats. Epilepsia. 2005b;46:1592–1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connors BW, Prince DA. Effects of local anesthetic QX-314 on the membrane properties of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982;220:476–481. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Antuono M, Biagini G, Tancredi V, Avoli M. Electrophysiology of regular firing cells in the rat perirhinal cortex. Hippocampus. 2001;11:662–672. doi: 10.1002/hipo.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Curtis M, Paré D. The rhinal cortices: a wall of inhibition between the neocortex and the hippocampus. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Guzman P, D’Antuono M, Avoli M. Initiation of electrographic seizures by neuronal networks in entorhinal and perirhinal cortices in vitro. Neuroscience. 2004;123:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derchansky M, Jahromi SS, Mamani M, Shin DS, Sik A, Carlen PL. Transition to seizures in the isolated immature mouse hippocampus: a switch from dominant phasic inhibition to dominant phasic excitation. J Physiol. 2008;586:477–494. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzel I, Heinemann U, Lux HD. Relations between slow extracellular potential changes, glial potassium buffering, and electrolyte and cellular volume changes during neuronal hyperactivity in cat brain. Glia. 1989;2:25–44. doi: 10.1002/glia.440020104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan M, Constanti A, Franz P. Calcium-dependent action potentials in guinea-pig olfactory cortex neurones. Pflugers Arch. 1985;404:252–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00581247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garden DL, Kemp N, Bashir ZI. Differences in GABAergic transmission between two inputs into the perirhinal cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:437–444. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloor P. The Temporal Lobe and Limbic System. Oxford University Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gnatkovsky V, Librizzi L, Trombin F, de Curtis M. Fast activity at seizure onset is mediated by inhibitory circuits in the entorhinal cortex in vitro. Ann Neurol. 2008;64:674–686. doi: 10.1002/ana.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasse DW, Karunakaran S, Moxon KA. Neuronal synchrony and the transition to spontaneous seizures. Exp Neurol. 2013;248:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi S, Avoli M. KCC2 function modulates in vitro ictogenesis. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;79:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.04.006. (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann U, Lux HD, Gutnick MJ. Extracellular free calcium and potassium during paroxysmal activity in the cerebral cortex of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1977;27:237–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00235500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann U, Konnerth A, Pumain R, Wadman WJ. Extracellular calcium and potassium concentration changes in chronic epileptic brain tissue. Adv Neurol. 1986;44:641–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberfeld G, Menendez de la Prida L, Pallud J, Cohen I, Le Van Quyen M, Adam C, Clemenceau S, Baulac M, Miles R. Glutamatergic pre-ictal discharges emerge at the transition to seizure in human epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:627–634. doi: 10.1038/nn.2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MS, Yaari Y. The relationship between interictal and ictal paroxysms in an in vitro model of focal hippocampal epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:591–598. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MS, Cherubini E, Yaari Y. Opponent effects of potassium on GABAA-mediated postsynaptic inhibition in the rat hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:764–771. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.69.3.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn SJ, Giacchino JL, Chamberlin NL, Dingledine R. Epileptiform burst activity induced by potassium in the hippocampus and its regulation by GABA-mediated inhibition. J Neurophysiol. 1987;57:325–340. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque M, Salami P, Gotman J, Avoli M. Two seizure onset types reveal specific patterns of high frequency oscillations in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13264–13272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5086-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopantsev V, Avoli M. Participation of GABAA-mediated inhibition in ictal like discharges in the rat entorhinal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:352–360. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan T, Jensen MS, Lambert JDC. The slow inhibitory postsynaptic potential in rat hippocampal neurons is blocked by intracellular injection of QX-314. Neurosci Lett. 1990;110:309–313. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90865-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoll RA, Malenka RC, Kauer JA. Functional comparison of neurotransmitter receptor subtypes in mammalian central nervous system. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:513–565. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogren JA, Bragin A, Wilson CL, Hoftman GD, Lin JJ, Dutton RA, Fields TA, Toga AW, Thompson PM, Engel J, Jr, Staba R. Three-dimensional hippocampal atrophy maps distinguish two common temporal lobe seizure-onset patterns. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1361–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KL, Wong RK. Intracellular QX-314 blocks the hyperpolarization-activated inward current Iq in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 1995;73:911–915. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.73.2.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault P, Avoli M. Physiology and pharmacology of epileptiform activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol. 1991;65:771–785. doi: 10.1152/jn.1991.65.4.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perucca P, Dubeau F, Gotman J. Intracranial electroencephalographic seizure-onset patterns: effect of underlying pathology. Brain. 2014;137:183–196. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutecki PA, Lebeda FJ, Johnston D. 4-Aminopyridine produces epileptiform activity in hippocampus and enhances synaptic excitation and inhibition. J Neurophysiol. 1987;57:1911–1924. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.6.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schevon CA, Weiss SA, McKhann G, Jr, Goodman RR, Yuste R, Emerson RG, Trevelyan AJ. Evidence of an inhibitory restraint of seizure activity in humans. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1060. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SS, Kim J, Spencer DD. Ictal spikes: a marker of specific hippocampal cell loss. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;83:104–111. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(92)90023-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudbury J, Avoli M. Epileptiform synchronization in the rat insular and perirhinal cortices in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:3571–3582. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SM, Gähwiler BH. Activity-dependent disinhibition. II Effects of extracellular potassium, furosemide, and membrane potential on EC- in hippocampal CA3 neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1989;461:512–523. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.3.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda I, Fujita S, Thamattoor AK, Buckmaster PS. Unit activity of hippocampal interneurons before spontaneous seizures in an animal model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6600–6618. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4786-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynelis SF, Dingledine R. Potassium-induced spontaneous electrographic seizures in the rat hippocampal slice. Neurophysiology. 1988;59:259–276. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevelyan AJ. The direct relationship between inhibitory currents and local field potentials. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15299–15307. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2019-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevelyan AJ, Sussillo D, Watson BO, Yuste R. Modular propagation of epilepti-form activity: evidence for an inhibitory veto in neocortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12447–12455. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2787-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truccolo W, Donoghue JA, Hochberg LR, Eskandar EN, Madsen JR, Anderson WS, Brown EN, Halgren E, Cash SS. Single-neuron dynamics in human focal epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:635–641. doi: 10.1038/nn.2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasco AL, Wilson CL, Babb TL, Engel J., Jr Functional and anatomic correlates of two frequently observed temporal lobe seizure-onset patterns. Neural Plast. 2000;7:49–63. doi: 10.1155/NP.2000.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viitanen T, Ruusuvuori E, Kaila K, Voipio J. The K+–Cl− cotransporter KCC2 promotes GABAergic excitation in the mature rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2010;588:1527–1540. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington MA, Traub RD, Jefferys JG. Erosion of inhibition contributes to the progression of low magnesium bursts in rat hippocampal slices. J Physiol. 1995;486:723–734. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhall GL, Bailey SJ, Thompson SE, Evans DI, Jones RS. Fundamental differences in spontaneous synaptic inhibition between deep and superficial layers of the rat entorhinal cortex. Hippocampus. 2005;15:232–245. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZJ, Koifman J, Shin DS, Ye H, Florez CM, Zhang L, Valiante TA, Carlen PL. Transition to seizure: ictal discharge is preceded by exhausted presynaptic GABA release in the hippocampal CA3 region. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2499–2512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4247-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]