Abstract

Background

Hematuria is the most important clinical manifestation of IgA nephropathy. This study was undertaken with the objective to describe the spectrum of histological changes with reference to the Oxford classification and the ultrastructural changes in the glomerular basement membrane and to correlate them with hematuria.

Methods

66 patients who underwent renal biopsy for IgA nephropathy were evaluated histologically by the Oxford system and also subject to electron microscopic examination for glomerular immune deposits, as well as alterations in the glomerular basement membrane.

Results

On comparing the histological scores generated by the Oxford classification with degree of hematuria, it was found that the status of ‘endocapillary proliferation’ and the status of ‘tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis showed a significant correlation. Correlation of hematuria with location of the deposits, i.e. mesangial only, and mesangial with capillary wall deposits (subendothelial and subepithelial) did not show any association. Other alterations of the GBM were seen in 12 cases. The changes included thinning alone in 4 cases, thinning and lamellar splitting in 5 cases, and lamellar splitting alone in 2 cases.

Conclusion

At presentation, endocapillary proliferation is one histological parameter which shows close association with hematuria.

Keywords: IgA nephropathy, Hematuria, Oxford classification, Electron microscopy

Introduction

IgA nephropathy is known to be the most common form of primary glomerulonephritis in the entire world.1 It is an immune complex mediated disease defined by the presence of either dominant or co-dominant deposits of IgA, predominantly in the glomerular mesangium. In India, the prevalence has been estimated to be between 12 and 15% of all renal biopsies.2 The classical presentation of the disease is with hematuria, although purely proteinuric presentations are also not unknown. Histological evaluation of the disease is now done according to the Oxford system of classification which generates a score based on four histological parameters.3 Electron microscopic examination in this disease has been mostly limited to evaluation for presence of immune complex type of electron dense deposits which may be seen in the mesangium, as well as the glomerular capillary walls. Alterations in the glomerular basement membrane have been often described, though poorly characterized.4 They have usually been considered to be rare. However, thinning of the glomerular basement membrane has been reported upon earlier to occur with some frequency.5 This study was undertaken with the objective to describe the spectrum of histological changes with reference to the Oxford classification and the ultrastructural changes in the glomerular basement membrane and to correlate them with hematuria.

Materials and methods

A total of 98 cases who underwent renal biopsy and were reported as IgA nephropathy were included in the study. The sample size was calculated at α = 95% and prevalence of 14.3%2 with a precision of 10%. Out of the total 98 cases, 22 cases had not undergone an electron microscopic examination and were excluded from the study. Cases with IgA nephropathy, but with sclerosed glomeruli were also excluded from the study. The remaining 66 cases were evaluated further for presence and degree of hematuria, light microscopic findings based on the Oxford system of classification, direct immunofluorescence findings, and electron microscopy. Degree of hematuria was classified as microscopic and gross. The gold standard for diagnosis of IgA nephropathy was considered to be dominant or codominant glomerular staining for IgA on IF. In all cases, the biopsy was fixed in formalin and routinely processed 3 μm serial sections were studied with H&E, PAS, and Massons Trichrome stains. Tissue for Immunofluorescence was transported in Michels medium and frozen sections were stained with FITC conjugated antibodies to IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, Kappa, Lambda, and C1q. Tissue for EM was routinely processed and stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate.

On light microscopy, the cases were categorized as per the Oxford system3, 6 and the four histological variables studied were mesangial hypercellularity (M), endocapillary proliferation (E), segmental glomerulosclerosis (S), and the proportion of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis, IF/TA(T). On electron microscopy, the changes looked for were the location and nature of immune complex type of electron dense deposits, and thinning, thickening, lamellar splitting, or rarefaction of the glomerular basement membrane. The clinical parameter studied was hematuria. Chi square test was used for analysis with SPSS 19.

Results

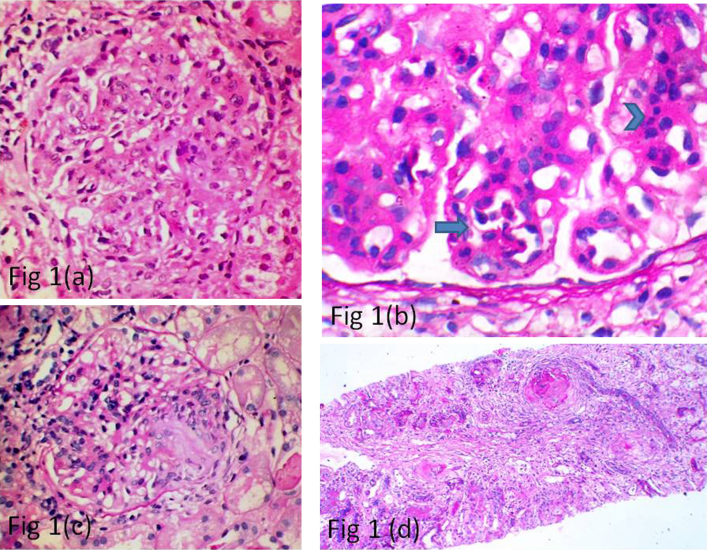

Of the 66 cases finally included in the study, 51 patients were males and 15 were females. The age ranged from 8 to 66 years with a mean of 37 years. Histologically, as per the Oxford classification, out of the 66 cases, 61 cases showed the presence of mesangial proliferation (M1) (Fig. 1(a)), 13 showed endocapillary proliferation (E1) (Fig. 1(b)), 32 showed segmental sclerosis (S1) (Fig. 1(c)), 36 showed mild tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (T1) (Fig. 1(d)), while 7 showed severe tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis (T2).

Fig. 1.

(a) Photomicrograph showing glomerulus with prominent mesangial cellularity (H&E, ×40). (b) Photomicrograph showing prominent mesangial cellularity (arrow head) and endocapillary proliferation (arrow) (PAS, ×100). (c) Photomicrograph showing glomerulus with a segmental sclerotic lesion (PAS, ×40). (d) Photomicrograph showing 2 sclerosed glomeruli and a focus of interstitial fibrosis (PAS, ×10).

On comparing the MEST scores with degree of hematuria, it was found that the status of E (endocapillary proliferation) and the status of T (degree of tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis) showed a significant correlation (Table 1). The degree of mesangial expansion and segmental sclerosis had no significant correlation with hematuria. Combined scoring of E and T lesions was attempted with microscopic and gross hematuria, but we could not demonstrate any association due to an insufficient number of cases falling into the E1T2 group.

Table 1.

Association of the 4 variables of the Oxford classification with hematuria.

| Microscopic | Gross | Total | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status of M | ||||

| 0 | 04 | 01 | 05 | 0.367 |

| 1 | 37 | 24 | 61 | |

| Total | 41 | 25 | 66 | |

| Status of E | ||||

| 0 | 36 | 16 | 52 | 0.021 |

| 1 | 05 | 09 | 14 | |

| Total | 41 | 25 | 66 | |

| Status of S | ||||

| 0 | 20 | 14 | 34 | 0.619 |

| 1 | 21 | 11 | 32 | |

| Total | 41 | 25 | 66 | |

| Status of T | ||||

| 0 | 19 | 04 | 23 | 0.009 |

| 1 | 19 | 16 | 35 | |

| 2 | 03 | 05 | 08 | |

| Total | 41 | 25 | 66 | |

M, mesangial expansion; E, endocapillary proliferation; S, segmental sclerosis; T, tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis.

In addition to hematuria, proteinuria was also noted in 45 cases which ranged from trace to subnephrotic.

In addition to mesangial immune complex type of electron dense deposits which were seen in all cases, glomerular basement membrane deposits were seen in 47/66 cases (71.2%). Of these 47 cases, 43 cases (68.1%) showed mesangial and subendothelial deposits and 4 cases showed mesangial, subendothelial, and subepithelial deposits. Correlation of hematuria with location of the deposits, i.e. mesangial only, and mesangial with capillary wall deposits (subendothelial and subepithelial) did not show any association (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association of location of immune complex type of electron dense deposits in the glomeruli with hematuria.

| Location of deposit | Hematuria |

Total | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microscopic | Gross | |||

| Only mesangial | 11 | 08 | 19 | 0.652 |

| Mesangial and capillary wall | 30 | 17 | 47 | |

| Total | 41 | 25 | 66 | |

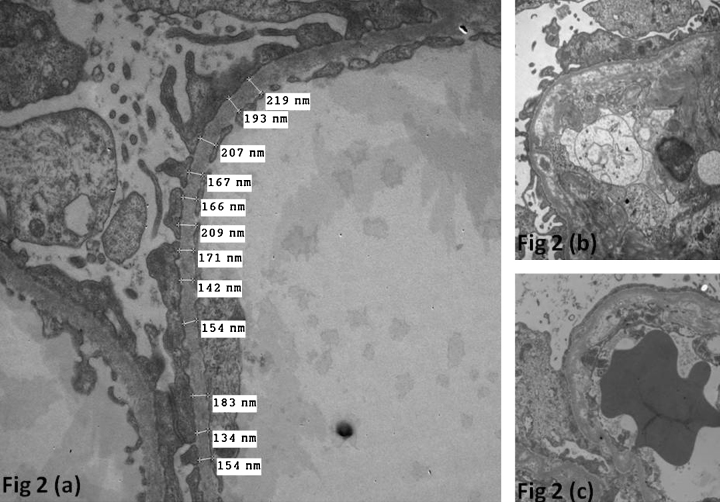

Other alterations of the GBM were seen in 12 cases. The changes included thinning alone in 4 cases, thinning and lamellar splitting in 5 cases, and lamellar splitting alone in 2 cases (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

(a) Ultrastructure photomicrograph showing thinning of the glomerular basement membrane (×5000). (b and c) Ultrastructure photomicrographs showing thickenings of the glomerular basement membranes with lamellations (×5000).

Discussion

In the present study, we have attempted to describe the correlation of hematuria with renal histology as per the MEST score and ultrastructural changes in the glomerular basement membrane. IgA nephropathy has traditionally been considered to be a disease affecting males more than females. The male:female ratio ranged from less than 2:1 in Japan to as high as 6:1 in northern Europe and the United States.7 Our study showed the prevalence of the disease to be more in males (77.2%). This is against the findings of Chandrika2 who reported the ratio to be 1.5:1 in a study from south India.

With the publication of the Oxford classification, various studies have been carried out over the years to study the significance of the four variables under consideration. We tried to correlate them with hematuria at presentation.

Gross and microscopic hematuria are considered to be important clinical presentations of the disease. As far as outcome is concerned, some studies have found a negative association between gross hematuria and renal outcome.8, 9 Multivariate analysis has shown a loss of this negative association.10 We were able to show correlation of gross hematuria with degree of endocapillary proliferation (i.e. E1 lesions) and tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis only out of the four components of the MEST score. In Haas's classification, it was found that while hematuria was seen in 90% of the cases, gross hematuria was seen in only 30%.11 Also, it was seen that gross hematuria was common in subclasses I (minimal histologic changes) and III (focal proliferative glomerulonephritis) of the Haas classification and less common in classes II (focal segmental glomerulosclerosis like) and V (advanced chronic glomerulonephritis), indicating that it was more common in earlier and milder lesions, as against the chronic lesions. In our study, we found hematuria to be more associated with active glomerular disease, i.e. endocapillary proliferation (E1), at presentation, rather than the milder lesions of mesangial proliferation (M1). Also, it continued to show association with the chronic lesions of interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy.

Deposition of immune complexes in the glomerular basement membrane in IgA nephropathy is well established. Lee et al. described their presence in 37% of all cases in a subendothelial location and 18% of all cases in a subepithelial location. Kusaba et al. reported a much lower rate of subendothelial deposits (2.2%).12 In this study, we found the presence of these deposits to be 68% which is much higher than the literature. Subepithelial deposits were seen in only 4 cases. The deposits were of the amorphous type and no organized substructure could be identified. We could not detect any association between location of the deposits on electron microscopy and hematuria (Table 2).

The thickness of the normal glomerular basement membrane in the Indian context has been reported to be 321 ± 28 nm with 265 nm being the level fixed for the diagnosis of thin basement membrane nephropathy (TBMN).13 TBMN is a common glomerular abnormality encountered in up to 7% of otherwise normal individuals.14 It has been considered to be a cause of microscopic hematuria in children and adults, though the condition is also known to be asymptomatic. In a review by Norby et al., the association of thin membrane disease with other glomerulopathies was described.15 They described situations where the thin membrane could be seen as an artifactual or an acquired finding in patients with other glomerulopathies, as a coexistence of two independent disease processes, or as a situation where the thin membrane is seen as a consequence of the other glomerulopathies. IgA nephropathy has been included as one of the situations where the glomerulopathy due to IgA could lead to the development of thin glomerular basement membranes. The association of TBMN and IgA nehropathy has been known since long.16 It has also been said that TBMN itself may be a predisposition for IgA nephropathy and the outcome in these patients is worse than for those with TBMN alone.17 Furthermore, it has also been shown that the occurrence of TBMN in cases of IgA nephropathy is significantly higher than in those without. In our study, we found the occurrence of thin glomerular basement membranes to be 9/66 cases, i.e. 13.6% which is much above the value for the general population. Further evaluation of these cases showed that of the 9 cases with thin membranes, 7 showed presence of deposits in the subendothelium or subepithelial regions. However, since familial studies to rule out TBMN in the siblings were not performed, we could not conclusively prove or disprove the causal role of the IgA nephropathy in the genesis of thin membranes. Also, none of the cases with thin membranes showed gross hematuria in the clinical findings. But it is also important to note that TBMN in the absence of any other disease process is unlikely to progress; however, if seen in the presence of any other glomerulopathy, like IgA nephropathy, it is likely to progress.

Lamellar splitting of the glomerular basement membrane was seen in 7 cases. A previous study had correlated the splitting with the degree of hematuria.18 However, in our study, we could not make any such inference.

Conclusion

Hematuria is the most17 common clinical presentation of IgA nephropathy, and correlates well with the presence of severe lesions like endocapillary proliferation on biopsy; however, it failed to show a significant correlation with early mild lesion like mesangial expansion and chronic lesion like segmental sclerosis on MEST scoring. A wide range of ultrastructural changes are seen in IgA nephropathy. In addition to the presence of immune complex type of electron dense deposits, a spectrum of changes can also be seen in the glomerular basement membrane including thinning, lamellar splitting, and combinations thereof. The location of the immune deposits has no bearing on the presence or severity of hematuria. The association between TBMN and IgA nephropathy is complex, with the incidence of thin membranes in cases of IgA nephropathy being much higher than what would expect in the general population. There is no clear association between presence of these ultrastructural glomerular basement membrane changes and hematuria.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgement

Dept of Histopathology, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh.

References

- 1.D’Amico G. The commonest glomerulonephritis in the world: IgA nephropathy. Q J Med. 1987;64:709–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chandrika B.K. IgA nephropathy in Kerala, India: a retrospective study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:14–16. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.44954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coppo R., Cattran D., Roberts Ian S.D. The new oxford clinico-pathological classification of IgA nephropathy. Contrib/Maced Acad Sci Arts Sect Biol Med SciPrilozi/Makedonska akademija na naukite i umetnostite, Oddelenie za bioloski i medicinski nauki. 2010;31:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee H.S., Choi Y., Lee J.S., Yu B.H., Koh H.I. Ultrastructural changes in IgA nephropathy in relation to histologic and clinical data. Kidney Int. 1989;35:880–886. doi: 10.1038/ki.1989.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danilewicz M., Wagrowska-Danilewicz M. Glomerular basement membrane thickness in primary diffuse IgA nephropathy: ultrastructural morphometric analysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 1998;30:513–519. doi: 10.1007/BF02550234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts I.S., Cook H.T., Troyanov S. The oxford classification of IgA nephropathy: pathology definitions, correlations, and reproducibility. Kidney Int. 2009;76:546–556. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donadio J.V., Grande J.P. IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:738–748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Amico G. Natural history of idiopathic IgA nephropathy: role of clinical and histological prognostic factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:227–237. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espinosa M., Ortega R., Gomez-Carrasco J.M. Mesangial C4d deposition: a new prognostic factor in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:886–891. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D’Amico G. Natural history of idiopathic IgA nephropathy and factors predictive of disease outcome. Semin Nephrol. 2004;24:179–196. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas M. Histologic subclassification of IgA nephropathy: a clinicopathologic study of 244 cases. Am J Kidney Dis. 1997;29:829–842. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90456-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kusaba G., Ohsawa I., Ishii M. Significance of broad distribution of electron-dense deposits in patients with IgA nephropathy. Med Mol Morphol. 2012;45:29–34. doi: 10.1007/s00795-011-0538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rayat C.S., Joshi K., Sakhuja V., Datta U. Glomerular basement membrane thickness in normal adults and its application to the diagnosis of thin basement membrane disease: an Indian study. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2005;48:453–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dische F.E., Anderson V.E., Keane S.J., Taube D., Bewick M., Parsons V. Incidence of thin membrane nephropathy: morphometric investigation of a population sample. J Clin Pathol. 1990;43:457–460. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.6.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norby S.M., Cosio F.G. Thin basement membrane nephropathy associated with other glomerular diseases. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanteri M., Wilson D., Savige J. Clinical features in two patients with IgA glomerulonephritis and thin-basement-membrane disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:791–793. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tonna S., Wang Y.Y., MacGregor D. The risks of thin basement membrane nephropathy. Semin Nephrol. 2005;25:171–175. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasaki T. Electron microscopy study on alterations of glomerular basement membrane in IgA nephropathy. Nihon Jinzo Gakkai shi. 1993;35:1033–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]