ABSTRACT

Increased deposition of collagen in extracellular matrix (ECM) leads to increased tissue stiffness and occurs in breast tumors. When present, this increases tumor invasion and metastasis. Precisely how this deposition is regulated and maintained in tumors is unclear. Much has been learnt about mechanical signal transduction in cells, but transcriptional responses and the pathophysiological consequences are just becoming appreciated. Here, we show that the SNAIL1 (also known as SNAI1) protein level increases and accumulates in nuclei of breast tumor cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) following exposure to stiff ECM in culture and in vivo. SNAIL1 is required for the fibrogenic response of CAFs when exposed to a stiff matrix. ECM stiffness induces ROCK activity, which stabilizes SNAIL1 protein indirectly by increasing intracellular tension, integrin clustering and integrin signaling to ERK2 (also known as MAPK1). Increased ERK2 activity leads to nuclear accumulation of SNAIL1, and, thus, avoidance of cytosolic proteasome degradation. SNAIL1 also influences the level and activity of YAP1 in CAFs exposed to a stiff matrix. This work describes a mechanism whereby increased tumor fibrosis can perpetuate activation of CAFs to sustain tumor fibrosis and promote tumor metastasis through regulation of SNAIL1 protein level and activity.

KEY WORDS: Mechanotransduction, SNAIL1, Fibrosis, Extracellular matrix

Highlighted article: SNAIL1 is a mechanoresponsive regulator of the fibrogenic response of tumors. The work provides insight into the transcriptional response of tumors to their microenvironment and CAF activation to sustain tumor fibrogenesis.

INTRODUCTION

Cells are responsive not only to chemical signals but also to mechanical signals. Mechanical signals, like chemical signals, can affect cell proliferation (Wang et al., 2000), differentiation (Engler et al., 2006), morphogenesis (Paszek et al., 2005) and migration (Gardel et al., 2008). Although much has been learned about the molecular basis of chemical signal transduction, how cells sense, transduce and respond to mechanical signals and the pathophysiological consequences of these signals is only just beginning to be appreciated (Humphrey et al., 2014). Mechanical stress can be external to cells, such as exposure to a stiff fibrillar-collagen-rich extracellular matrix (ECM). Cells also probe their immediate environment to sense stiffness by pulling on matrix fibers through ECM adhesion sites. The increase in intracellular tension necessary can be generated from cell-intrinsic signals.

In cancer, it is now appreciated that the tumor microenvironment contributes to tumor development, promotion, spread or metastasis, and response to therapy (Lu et al., 2012). The tumor environment or tumor stroma consists of various non-tumor cells, structural proteins, glycoproteins, embedded growth factors and cytokines, and, in tumors, these components differ from their normal tissue counterparts in composition, architecture, physical character and function. For example, in breast tumors there can be increased collagen deposition, thickening of collagen fibers and alterations in collagen fiber architecture, and, when present, are associated with poor prognosis due to an increased propensity to develop invasive or metastatic disease (Provenzano et al., 2006; Conklin et al., 2011). Increased collagen deposition and cross-linking in the ECM of breast tumor stroma increases tissue stiffness (Paszek et al., 2005). Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are the stromal cells primarily responsible for generating the interstitial matrix associated with tumors (Bhowmick et al., 2004). But CAFs can also remodel the tumor ECM (Gaggioli et al., 2007) and promote matrix stiffness (Calvo et al., 2013; Stanisavljevic et al., 2015). Together, these CAF-mediated changes in the physical properties of the ECM facilitate or enhance tumor cell invasion. Whether these mechanical signals in turn influence CAF functions and, if so, how they do so is only just being evaluated.

It has been shown that the Hippo pathway transcriptional co-activator YAP (also known as YAP1) is activated by mechanical signals (Dupont et al., 2011; Aragona et al., 2013) and, in CAFs, controls the expression of cytoskeletal regulators that increase intracellular tension in order to promote matrix stiffening (Calvo et al., 2013). Recently, the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) factor SNAIL1 (also known as SNAI1) has been found to be crucial for production of ECM by CAFs and also to affect their capacity to increase matrix stiffness. Although SNAIL1 was initially described as a TGFβ target gene that promotes EMT during developmental programs and epithelial tumor progression, accumulating data has shown that SNAIL1 also has important functions in mesenchymal cells, independent of its EMT function (Rowe et al., 2009; Batlle et al., 2013; Stanisavljevic et al., 2015).

SNAIL1 protein expression in tumor samples is detected predominantly in tumor cells and stromal CAFs at the tumor–stromal boundary (Francí et al., 2006). In the absence of environmental signals, intracellular SNAIL1 protein is rapidly degraded, and the importance of post-transcriptional regulation of SNAIL1 protein level as being essential for SNAIL1 function is now appreciated (Zhou et al., 2004; Yook et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2013). Given that the environment of SNAIL1-expressing CAFs is exposed to changes during cancer progression, the full repertoire of environmental signals regulating SNAIL1 protein level and function are likely incompletely understood.

In this study, we find that SNAIL1 protein level, nuclear accumulation and activity are regulated by mechanical signals through ROCK- and ERK2-dependent pathways, which is distinct from how mechanical signals regulate YAP. In addition, and also distinct from YAP function in CAFs, SNAIL1 regulates the fibrogenic response of CAFs exposed to a stiff matrix. These results identify SNAIL1 as a new mechano-responsive transcriptional regulator in CAFs that sets up a feed-forward loop to sustain tumor fibrosis. We discuss how this CAF function for SNAIL1 contributes to tumor cell invasion and metastasis.

RESULTS

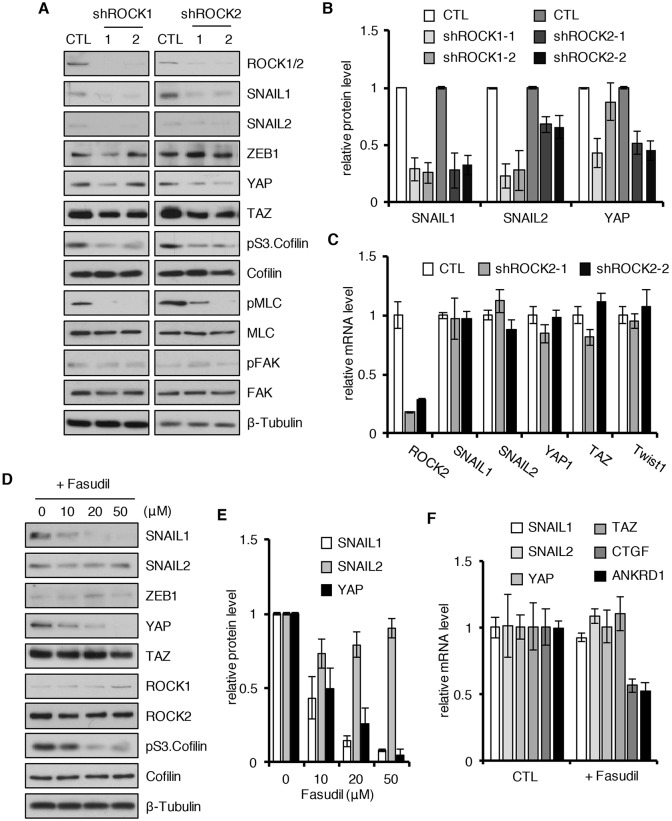

ROCK kinases increase SNAIL1 protein level post-transcriptionally

In a previously described cell-based small interfering RNA (siRNA) screen to identify protein kinases that stabilized the SNAIL1 protein level (Zhang et al., 2011), ROCK2 was identified as a potential candidate. To confirm that the presence and/or activity of ROCK1 and/or ROCK2 influenced the SNAIL1 protein level, we transduced human breast tumor CAFs with lentiviruses expressing short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs; two to four different shRNAs) targeting ROCK1 and ROCK2 using sequences distinct from those of the siRNA oligonucleotides used in the siRNA screen. In ROCK1- and ROCK2-depleted CAFs, the SNAIL1 protein level decreased (Fig. 1A, quantified in Fig. 1B). The protein level of the related EMT factor SNAIL2 (also known as SNAI2) also appeared to decrease, whereas that of ZEB1 was unaffected (Fig. 1A,B). As a measure of ROCK activity, the level of cofilin phosphorylated at S3 (denoted pS3.Cofilin) a downstream target of LIMK1 (Arber et al., 1998) and phosphorylated myosin light chain (MYL2; denoted pMLC), which are both activated by ROCK, were determined. The level of both decreased in ROCK1- and ROCK2-depleted cells (Fig. 1A). The effect of ROCK1 or ROCK2 upon SNAIL1 protein level was found to be post-transcriptional, as shRNA-mediated depletion of either did not affect the level of SNAIL1 mRNA (Fig. 1C). Similar results were observed when SNAIL1-expressing invasive human breast tumor cells MDA-MB-231 was likewise analyzed (Fig. S1A–C).

Fig. 1.

ROCK kinases increase the SNAIL1 protein level post-transcriptionally. Human breast CAFs were infected with lentiviruses expressing two different shRNAs targeting ROCK1 or ROCK2 (shROCK) or control scrambled shRNA (CTL). Western blotting of cell extracts was performed with the indicated antibodies (A). (B) Quantification of the relative protein level of SNAIL1, SNAIL2 and YAP in the experiment described in A. Level of protein in control cells was arbitrarily set at 1. (C) Q-PCR determination for relative mRNA levels for the indicated mRNAs from samples as in experiment A. (D) CAFs were treated with Fasudil at increasing concentrations, as indicated, for 8 h. Western blotting of cell extracts was performed with the indicated antibodies. (E) Quantification of the relative protein level of SNAIL1, SNAIL2 and YAP in the experiment described in D. The level of protein in cells at t=0 were arbitrarily set at 1. (F) Q-PCR of the relative level of mRNA of genes from the CAF cells treated with DMSO (CTL) or 10 µM Fasudil for 8 h, as in experiment D. All experiments were performed two or three times and a representative example shown. Quantifications are plotted as the mean±s.d.

In a parallel screen, performed simultaneously, we used human MDA-MB-231 breast tumor cells that contained an exogenous bioluminescent SNAIL1 click beetle green fusion protein (SNAIL1–CBG) under the control of the CMV promoter. We screened these cells with the Pharmakon 1600 drug collection library of FDA-approved compounds for drugs that decreased SNAIL1 protein level. From this library, the ROCK inhibitor Fasudil was identified. Treatment of MDA-MB-231 breast tumor cells with Fasudil or Y-27632, another ROCK inhibitor, resulted in decreased SNAIL1 and SNAIL2 protein level but no change in that of ZEB1 (Fig. S1D, quantified in Fig. S1E). When CAFs were treated with Fasudil, the control pS3.Cofilin level decreased, as did the SNAIL1 protein level (Fig. 1D, quantified in Fig. 1E), but the protein level of SNAIL2 or ZEB1 did not change (Fig. 1D). The effect of Fasudil upon the SNAIL1 protein level was higher in CAFs than in MDA-MB-231 tumor cells (Fig. 1D versus Fig. S1D). Finally, Fasudil treatment of CAFs did not alter the mRNA level of SNAIL1 or SNAIL2 (Fig. 1F).

In sum, two independent unbiased screens designed to identify cellular regulators of SNAIL1 protein level identified the ROCK protein kinases. In both human breast tumor CAFs and invasive human breast tumor cells, ROCK activity regulated the SNAIL1 protein level post-transcriptionally.

Exposure of CAFs to a stiff ECM increases the SNAIL1 protein level post-transcriptionally

Cells sense changes in the physical properties of the surrounding environment, such as stiffness, by increasing intracellular tension in the actomyosin cytoskeleton that pulls against the ECM through cell surface adhesive receptors (e.g. integrins) within focal adhesions (Humphrey et al., 2014). Rho GTPase is a key regulator of the intracellular contractility that allows cells to sense changes in ECM stiffness. The function of Rho in this setting is largely mediated by its effector kinase ROCK (Paszek et al., 2005). Breast tumors that result in a poor prognosis are often associated with increased collagen deposition within the tumor stroma and a resulting increase in tissue stiffness (Paszek et al., 2005). Given that tumor CAFs produce the matrix associated with tumors, and SNAIL1 has recently been shown to be important for CAF function (Stanisavljevic et al., 2015), we asked whether exposure of breast tumor CAFs to a stiff matrix influenced SNAIL1 protein level and activity.

As a positive control for mechano-signaling, we measured the cellular level of YAP protein. The protein level, subcellular localization and activity of the transcriptional co-activator YAP is affected when mesenchymal cells are exposed to a stiff matrix (Dupont et al., 2011). shRNA-mediated depletion of ROCK1 and ROCK2, or Fausidil treatment of CAFs resulted in decreased YAP protein level (Fig. 1A,D, respectively). Fasudil treatment of CAFs did not alter the mRNA level of YAP but did decrease transcription of the YAP-regulated genes CTGF and ANKRD1 (Calvo et al., 2013) (Fig. 1F).

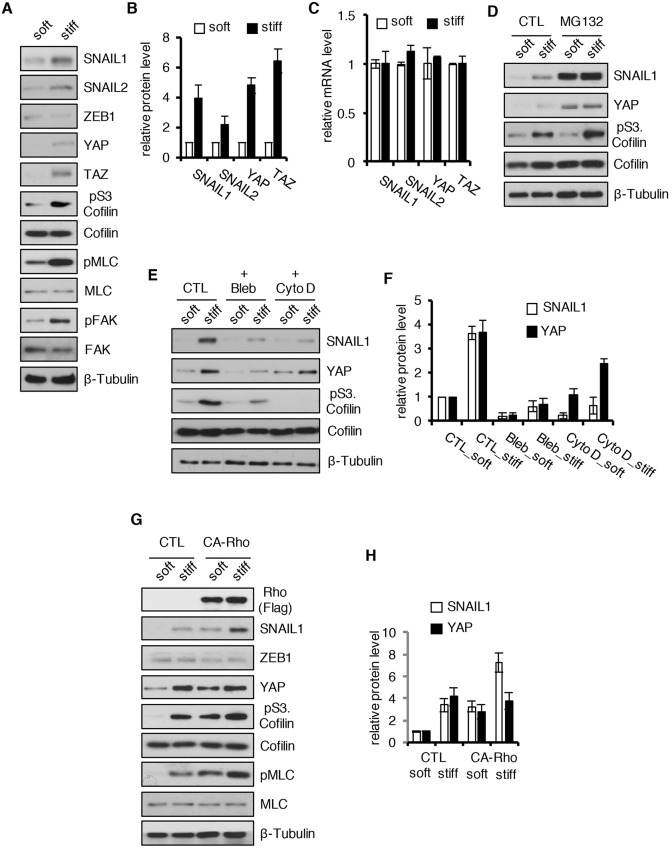

When CAFs were exposed to soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) fibronectin-coated polyacrylamide hydrogels, YAP, SNAIL1 and SNAIL2, but not ZEB1, protein level increased (Fig. 2A, quantified in Fig. 2B). Exposure of CAFs to a stiff matrix increased Rho–ROCK activity as evidenced by increased level of pS3.Cofilin and pMLC, and increased intracellular tension as evidenced by increased level of phosphorylated FAK (pFAK; FAK is also known as PTK2) (Fig. 2A). The increase in SNAIL1, SNAIL2 and YAP protein level occurred post-transcriptionally, as exposure of cells to a stiff matrix did not alter their mRNA levels (Fig. 2C). Similar results were observed when MDA-MB-231 breast tumor cells were likewise treated (Fig. S2A–E).

Fig. 2.

Mechanical signals increase the SNAIL1 protein level post-transcriptionally. (A) Human breast tumor CAFs were cultured on soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) polyacrylamide hydrogels coated with fibronectin for 12 h. Western blotting of cell extracts was performed with the indicated antibodies. (B) Quantification of the relative protein level of SNAIL1, SNAIL2, YAP and TAZ for the experiment described in A. The level of protein in cells on soft substrate was arbitrarily set at 1. (C) Q-PCR determination of relative SNAIL1, SNAIL2, YAP and TAZ mRNA level in CAFs cultured on fibronectin-coated soft or stiff hydrogels, as described in A. (D) CAFs were plated on fibronectin-coated soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) hydrogels for 8 h, then treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (10 µM) for 4 h or left untreated (CTL). Western blotting of cell lysates was performed with the indicated antibodies. (E) CAFs were plated on fibronectin-coated soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) hydrogels for 8 h, then treated with blebbistatin (20 µM) or cytochalasin D (10 µM) for 4 h or untreated (CTL). Western blotting of cell lysates was performed with the indicated antibodies. (F) Quantification of the relative protein level of SNAIL1 and YAP in the experiment described in E. The level of protein in control cells on soft substrate was arbitrarily set at 1 (n=2). (G) WT CAFs (CTL) or CAFs expressing constitutively activated RhoA (CA-Rho) were plated on fibronectin-coated soft or stiff hydrogels for 12 h. Western blotting was performed on cell lysates with the indicated antibodies. (H) Quantification of the relative protein level of SNAIL1 and YAP in the experiment described in G (n=2). The level of protein in control cells on soft substrate was arbitrarily set at 1. All experiments were performed two or three times. Quantifications are plotted as the mean±s.d.

Both YAP and SNAIL1 proteins are phosphorylated in the cytosol and targeted for degradation by proteasomes (Zhou et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2010). Thus, we asked whether inhibition of proteasome function in CAFs on soft matrices increased SNAIL1 protein to the level observed when CAFs were exposed to a stiff matrix. When CAFs were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 prior to addition to a soft matrix, both SNAIL1 and YAP protein levels increased (Fig. 2D). MG132 treatment also increased SNAIL1 and YAP protein level in cells plated on a stiff matrix (Fig. 2D), indicating that external mechanical signals led to an increase in SNAIL1 protein level by preventing its proteosomal degradation and that mechanical signals alone did not maximally stabilize SNAIL1 protein.

Blocking intracellular tension buildup by inhibiting myosin II activity with blebbistatin or actin filament assembly with cytochalasin D prevented the increases in SNAIL1 and YAP protein level in CAFs exposed to a stiff matrix (Fig. 2E, quantified in Fig. 2F). Increasing intracellular tension by expressing constitutively activated RhoA in CAFs led to an increased SNAIL1 and YAP protein level, relative to control cells, for cells plated on both soft and stiff matrices (Fig. 2G, quantified in Fig. 2H). Exposure of CAFs to a stiff matrix (hydrogel) also increased the SNAIL1 protein half-life (Fig. S2F, quantified in Fig. S2G).

In another approach, we exposed cells to a different external mechanical signal. Freshly trypsinized and dissociated CAFs were maintained in solution by gentle rocking for a few hours (i.e. ‘low intracellular tension’) and then added to plastic tissue culture dishes [i.e. ‘high external stiffness’) (Paszek et al., 2005)]. SNAIL1 protein level was determined at increasing times following addition to plastic plates. The pS3.Cofilin and pMLC level progressively increased in cells plated on plastic indicating increased intracellular tension (Fig. S3A). As occurred when CAFs were exposed to stiff hydrogels, the SNAIL1 and YAP protein level progressively increased whereas the ZEB1 level remained unchanged with increasing time of exposure to stiff plastic tissue culture plates (Fig. S3A, quantified in Fig. S3B), and this response was ROCK-dependent because Fasudil treatment blocked the response (Fig. S3A, quantified in Fig. S3B).

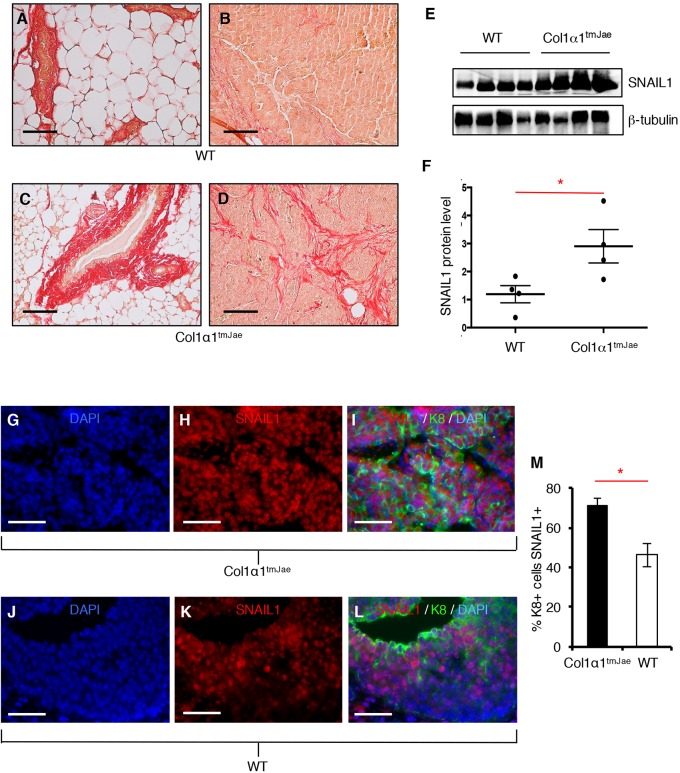

To determine whether exposure of tumors to increased matrix stiffness in vivo stabilized SNAIL1 protein level, we made use of the Col1αltmJae mouse that contains a mutant allele of collagen 1α1 that is resistant to degradation by collagenase. In these mice, there is increased deposition of fibrillar collagen fibers in the breast ECM (Provenzano et al., 2008), which is strongly correlated with increased tissue stiffness (Roeder et al., 2002; Paszek et al., 2005; Provenzano et al., 2009). We confirmed the increase in collagen deposition in the breast and breast tumors in these mice, as compared with wild-type (WT) mice (Fig. 3A,C and B,D, respectively). Primary mammary tumor cells derived from breast oncogenic MMTV-PyMT mice were transplanted into both syngeneic WT or Col1αltmJae mice, and the resulting breast tumors were isolated and lysed, and the SNAIL1 level was assessed by western blotting. When normalized to protein content, there was increased SNAIL1 protein present in breast PyMT tumors from Col1αltmJae mice compared to tumors from WT mice (Fig. 3E, quantified in Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

SNAIL1 protein level increases in breast tumors from mice with increased collagen deposition in the breast. (A–D) Picosirius Red staining of mammary gland from 13-week-old mice (A,C) and implanted PyMT breast tumor from WT (B) and Col1α1tmJae mice (D). (E) Western blot analysis of whole-tumor tissue lysates harvested from mammary tumors of FVB WT or FVB Col1α1tmJae mice transplanted with primary PyMT tumor cells. (F) Graph quantifying SNAIL1 protein level determined by densitometry and normalized to β-tubulin control. Results are presented as mean±s.d.; n=4. (G–L). Tumor epithelial K8 and SNAIL1 immunofluorescence of breast tumors from Col1α1tmJae mice (G–I) and WT mice (J–L). (M) A quantification of the percentage of K8+ tumor cells that were also SNAIL1+ in breast tumors from Col1α1tmJae mice and WT mice. Results are presented as mean±s.d. of five fields that were scored. *P<0.05 (unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests). Scale bars: 50 μm.

In mouse PyMT breast tumor samples, only 5% of cells are fibroblastic (Sharon et al., 2013). The majority are tumor cells or inflammatory cells. Immunofluorescent analysis of primary breast tumors revealed that there was an increased number of K8+ tumor cells expressing SNAIL1 in tumors from Col1αltmJae mice as compared to tumors from WT mice (Fig. 3G–L, quantified in Fig. 3M). Thus, the increase in SNAIL1 protein level observed in PyMT breast tumors from Col1αltmJae mice likely represents mostly tumor cell SNAIL1. Breast tumor cell SNAIL1 protein level also increases in cultured tumor cells exposed to a stiff ECM (Fig. S2A,B).

In summary, using multiple approaches, exposure of human breast tumor CAFs and human breast tumor cells to a stiff environment, or conditions that increase intracellular tension, causes the SNAIL1 protein level to increase post-transcriptionally. This effect is ROCK dependent. In mouse, breast tumors that develop with increased collagen deposition in the breast show an increase in SNAIL1 protein level.

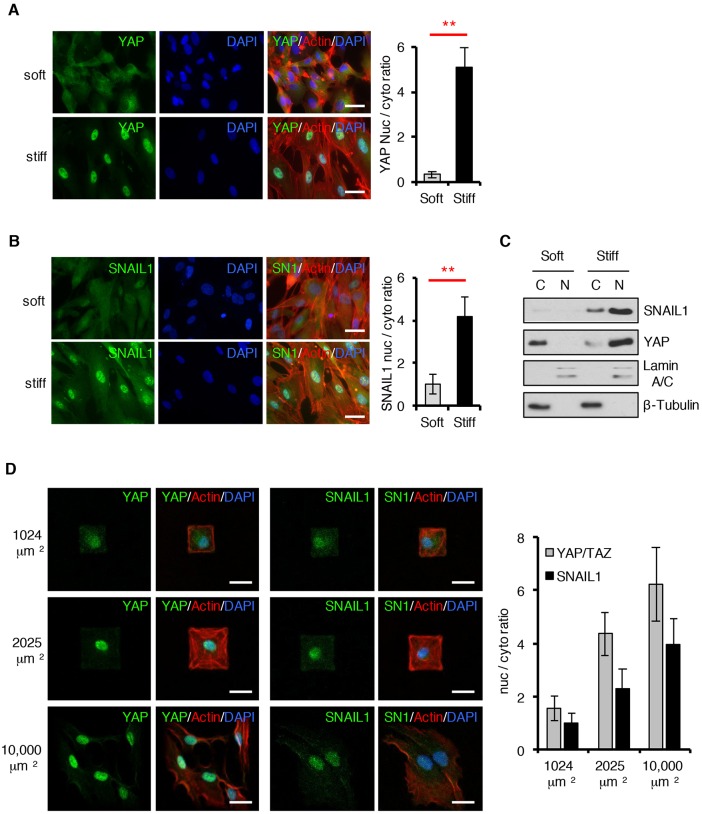

Exposure of CAFs to a stiff ECM induces SNAIL1 nuclear accumulation

SNAIL1 is a transcriptional regulator, and as such, needs to enter the nucleus for its activity. Moreover, when cytosolic proteosomal degradation is prevented, the total cellular SNAIL1 protein half-life increases (Zhang et al., 2013). Therefore, we asked whether SNAIL1 accumulated in the nucleus of CAFs in response to exposure to a stiff matrix. By performing immunofluorescence analysis of endogenous proteins and western blot analysis of isolated nuclear and cytoplasmic cellular fractions from CAFs following exposure to stiff matrices, and taking into account the increase in protein level, nuclear localization of both SNAIL1 and control YAP increased (Fig. 4A–C).

Fig. 4.

In response to mechanical signals SNAIL1 accumulates in the nucleus. (A–C) CAFs were cultured on fibronectin-coated soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) hydrogels for 12 h. Immunofluorescent staining for YAP (A) or SNAIL1 (B) (both green), F-actin (Rhodamine–phalloidin, red) and nuclei (DAPI staining, blue) was performed. The nuclear-to-cytosolic ratio of the YAP or SNAIL1 fluorescent intensity was quantified using ImageJ software. At least 50 cells, in multiple fields, were quantified. (C) CAFs were treated as in A and B, but after 12 h cells were lysed and the nuclear (N) and cytosolic (C) fractions isolated. Western blotting was performed on subcellular fractions with the indicated antibodies. Lamin A/C served as a nuclear marker whereas β-tubulin served as a cytosolic marker. (D) Confocal immunofluorescence images of CAFs plated on fibronectin-coated micropatterns of indicated area sizes (μm2) for 6 h. Scale bars: 20 μm. Histograms to the right show a quantification of the nuclear-to-cytosolic fluorescent intensity ratio of YAP or SNAIL1 in cells as determined with ImageJ software. At least 20 cells were quantified per condition. Results are presented as mean±s.d. **P<0.01 (unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests).

Using another approach, CAFs were plated on fibronectin-coated micro-fabricated square islands of differing areas. When mesenchymal cells are allowed to attach and spread on large islands (10,000 µm2) intracellular tension increases, whereas on smaller islands (1024 µm2), where cells can not spread as well, intracellular tension is lower (Dupont et al., 2011). When CAFs were plated on large islands the control nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio of YAP was high relative to that observed when plated on small islands, as expected (Fig. 4D) (Dupont et al., 2011). The nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio of SNAIL1 was also higher on large islands versus small islands (Fig. 4D). In a third approach, freshly trypsinized and dissociated CAFs were maintained in solution by gentle rocking for a few hours (i.e. ‘low intracellular tension’) and then added to plastic tissue culture dishes (i.e. ‘high external stiffness’). Following a 4-h exposure to stiff plastic tissue culture dishes, the total cellular SNAIL1 protein level increased and was found to accumulate in the nucleus (Fig. S2H).

In summary, using multiple approaches and analyses, SNAIL1 protein was found to accumulate in the nucleus of CAFs following exposure to a stiff environment.

ECM-stiffness-induced ROCK stabilizes and activates SNAIL1 through indirect ERK2 activation

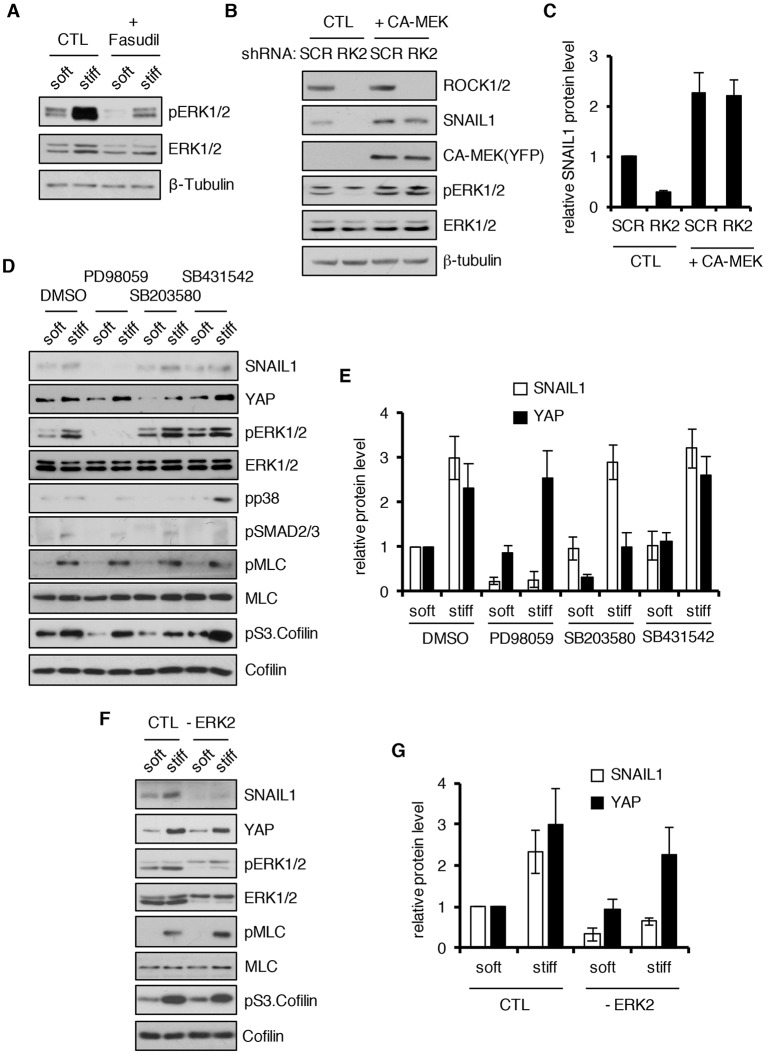

How then does the increased intracellular ROCK activity that occurs following exposure of cells to a stiff ECM lead to stabilization and activation of SNAIL1? We found no supporting data showing that ROCK physically associated with SNAIL1 in cells, arguing that it was unlikely that ROCK directly modified SNAIL1. However, we noted that when CAFs were exposed to a stiff matrix, ERK1 and ERK2 (ERK1/2; also known as MAPK3 and MAPK1, respectively) activity increased (Fig. 5A; Fig. S3A) and inhibition of ROCK activity largely, but not completely, limited this ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 5A). To determine whether ROCK activity influenced the SNAIL1 level only through stimulation of ERK1/2 activity we depleted ROCK1 and ROCK2 with shRNA, and then overexpressed constitutively activated MEK (CA-MEK), a downstream effector of these proteins. In the presence of CA-MEK, depletion of ROCK1 and ROCK2 decreased SNAIL1 levels only slightly, and not to the level seen in the absence of CA-MEK (Fig. 5B, quantified in Fig. 5C). This suggests that the activity of ROCK regulates SNAIL1 level predominantly through activation of ERK1/2, but also through additional pathway(s).

Fig. 5.

ROCK increases SNAIL1 protein level and nuclear accumulation through indirect activation of ERK2. (A) CAFs treated with Fasudil (10 µM) or untreated (CTL) were added to soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) fibronectin-coated hydrogels for 12 h, then the cells were lysed and western blotting performed on cell extracts with the indicated antibodies. (B) CAFs were infected with scrambled shRNA (SCR) or ROCK2-shRNA-expressing lentivirus (RK2) and then transfected with YFP-tagged constitutively activated MEK (CA-MEK) or empty plasmid DNA (CTL). Western blotting was performed on cell extracts with the indicated antibodies. (C) Quantification of the relative SNAIL1 protein level in the experiment described in B. The level of protein in control cells exposed to scrambled shRNA was arbitrarily set at 1. (D) CAFs were cultured on fibronectin-coated soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) hydrogel for 12 h in the presence of dilute DMSO, MEK1 inhibitor PD98059 (50 µM), p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (20 µM) or TGFβ pathway inhibitor SB431542 (10 µM). Western blotting was performed on cell extracts with the indicated antibodies. (E) Quantification of the relative protein level of SNAIL1 and YAP in the experiment described in D. The level of protein in control cells on soft substrate was arbitrarily set at 1. (F) CAFs (CTL) or CAFs depleted of ERK2 with shRNA (–ERK2) were plated on soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) matrices and western blotting was performed on cell extracts with the indicated antibodies. (G) Quantification of the relative protein level of SNAIL1 and YAP in the experiment described in F. The level of protein in control cells on soft substrate was arbitrarily set at 1. All experiments were performed two or three times and a representative example is shown. Quantifications are plotted as the mean±s.d.

Both ROCK proteins and ERK1/2 can be activated as a result of integrin clustering and signaling at focal adhesions that occurs when intracellular tension increases (Paszek et al., 2005; Wong et al., 2012; Esnault et al., 2014). Integrins clustered into large focal adhesions and were activated when CAFs were exposed to a stiff matrix, as evidenced by the increase in the pFAK level (Fig. 2A) and vinculin immunofluorescent analysis of focal adhesion assembly (Fig. S3C–H).

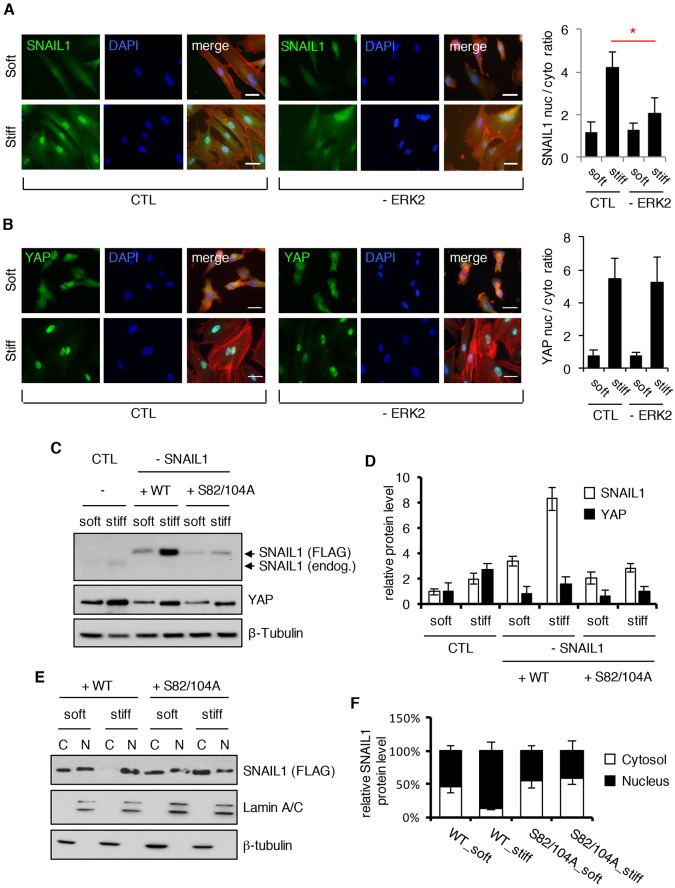

ERK2 can associate with and phosphorylate SNAIL1, and this leads to increased SNAIL1 nuclear accumulation (Zhang et al., 2013). This led us to ask whether ROCK proteins stabilized SNAIL1 by increasing intracellular tension (i.e. increased actomyosin contractility) that then activated integrins, which subsequently led to ERK1/2 activation (i.e. ROCK indirectly increases SNAIL1 protein level by activating ERK2). Pharmacological inhibition of ERK1/2, but not p38 MAPK family proteins or TGFβ signaling, resulted in decreased SNAIL1 protein level in CAFs exposed to a stiff matrix, yet minimally affected ROCK activity, as evidenced by there being no change in pS3.Cofilin and pMLC level (Fig. 5D, quantified in Fig. 5E). In contrast to SNAIL1, inhibition of ERK1/2 did not affect the YAP protein level (Fig. 5D, quantified in Fig. 5E). shRNA-mediated depletion of ERK2 also blocked the ECM-stiffness-induced increase in SNAIL1 protein level (Fig. 5F, quantified in Fig. 5G) and SNAIL1 nuclear accumulation (Fig. 6A), but did not affect ROCK activation (Fig. 5F, see pMLC and pS3.Cofilin levels), YAP protein level (Fig. 5F, quantified in Fig. 5G) or YAP nuclear accumulation (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

ROCK increases SNAIL1 nuclear accumulation through activation of ERK2. (A,B) Immunofluorescent staining for SNAIL1 (A) or YAP (B) (green), F-actin (Rhodamine–phalloidin, red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in CAFs cultured on fibronectin-coated soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) hydrogels for 12 h that were treated with scrambled shRNA (CTL) or depleted of ERK2 with shRNA (–ERK2). Histograms on right quantify the nuclear-to-cytosolic fluorescent intensity ratio of SNAIL1 (A) or YAP (B) using ImageJ software. Bars represent the mean±s.d.; more than 50 cells, in multiple fields were scored. *P<0.05 (unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests). Scale bars: 20 μm. (C) Human breast tumor CAFs were depleted of SNAIL1 with shRNA (–SNAIL1) or scrambled shRNA (CTL). SNAIL1-depleted cells were concurrently rescued with FLAG-tagged shRNA-resistant WT SNAIL1, or an S82A,S104A (S82/104A) SNAIL1 mutant. Cells were then cultured on fibronectin-coated soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) hydrogels for 12 h. Western blotting was performed on cell extracts with the indicated antibodies. (D) Quantification of the relative amount of SNAIL1 and YAP protein level in the experiment described in C. The protein level in CTL cells on soft substrate was arbitrarily set at 1. (E) Human breast CAFs were depleted of SNAIL1 with shRNA (–SNAIL1) or scrambled shRNA (CTL). SNAIL1-depleted cells were concurrently rescued with FLAG-tagged shRNA-resistant WT SNAIL1, or an S82A,S104A SNAIL1 mutant. Cells were then cultured on fibronectin-coated soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) hydrogels for 12 h. Nuclear (N) and cytosolic (C) fractions were isolated and western blotting performed on extracts from each subcellular fraction. Lamin A/C served as a nuclear marker whereas β-tubulin served as a cytosolic marker. The experiment was performed twice (n=2). (F) Quantification of the relative distribution of SNAIL1 protein level between the nucleus and cytosol for experiment the described in E. Quantifications are plotted as the mean±s.d.

Active ERK2 phosphorylates SNAIL1 at S82 and S104 (Zhang et al., 2013). To test whether these ERK2 phosphorylation events were required for stabilization of SNAIL1 in CAFs exposed to a stiff matrix, we depleted endogenous SNAIL1 with shRNA and expressed either shRNA-resistant WT SNAIL1 (FLAG-tagged) or an ERK2-phosphorylation-defective mutant of SNAIL1 (FLAG-tagged SNAIL1 S82A, S104A) using a double copy lentivirus that concurrently expresses shRNA and shRNA-resistant rescue isoforms in the same cell (Feng et al., 2010). Whereas rescue with WT SNAIL1 restored the mechanical response, SNAIL1 S82A,S104A was not stabilized in CAFs exposed to a stiff matrix (Fig. 6C, quantified in Fig. 6D). Mutant SNAIL1 S82A,S104A also did not accumulate in the nucleus in response to exposure to a stiff matrix (Fig. 6E, quantified in Fig. 6F).

In summary, these results indicate that ECM-stiffness-induced ERK2 activation predominantly contributes to the increase in SNAIL1 protein level, likely as a result of its nuclear accumulation and subsequent avoidance of cytosolic proteosomal degradation. ROCK activity increased SNAIL1 protein level by increasing intracellular tension, which leads to integrin clustering and signaling that then activates ERK2 (i.e. ROCK activity indirectly stabilizes SNAIL1 through ERK2).

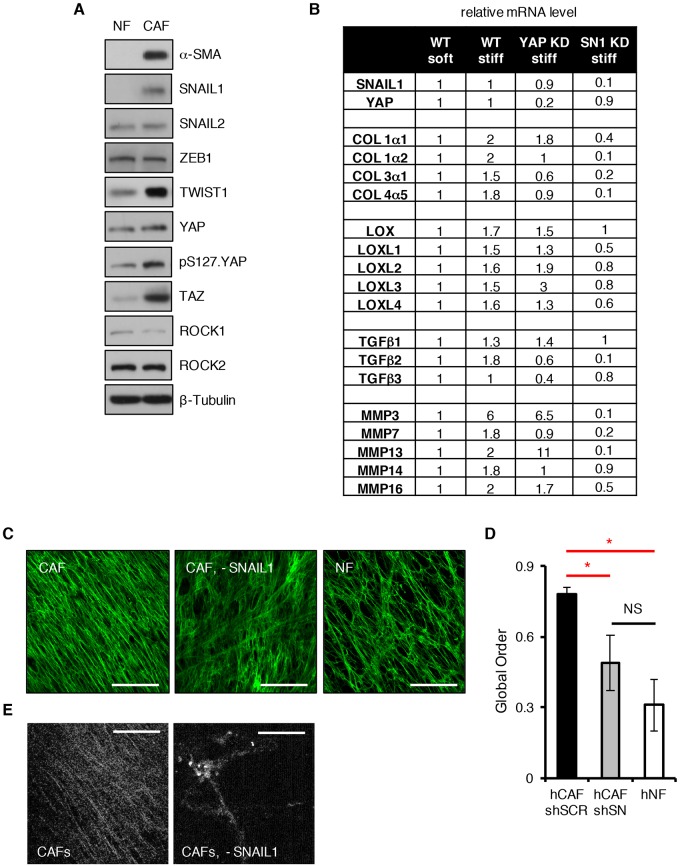

In response to ECM stiffness, CAFs increase matrix production and remodeling in a SNAIL1-dependent manner

Recently, the action of SNAIL1 in CAFs has been shown to control the production of ECM and orientation of fibronectin fibers (Stanisavljevic et al., 2015). In contrast to breast tumor CAFs, normal breast fibroblasts did not express SNAIL1 protein, although they did express other EMT factors (SNAIL2, TWIST1 and ZEB1; Fig. 7A). We contrasted fibrosis-related gene expression of human breast tumor CAFs following their exposure to soft versus stiff matrices. In control WT CAFs, expression of many genes changed upon exposure to a stiff matrix (Fig. S4A). Depletion of SNAIL1 resulted in altered expression of many fibrotic or inflammatory related genes by CAFs (Fig. S4A).

Fig. 7.

SNAIL1 regulates the fibrogenic response of CAFs following exposure to mechanical signals. (A) Western blotting was performed on cell extracts of normal human breast fibroblasts (NF) and human breast tumor cancer CAFs (CAF) with the indicated antibodies. (B) Q-PCR analyses for mRNA level of select fibrogenic genes in CAFs [WT, YAP-depleted (YAP KD) or SNAIL1-depleted (SN1 KD)] after plating on soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPA) fibronectin-coated hydrogels for 12 h: collagens (COL), TGFβs, MMPs and lysyl oxidases (LOX). (C) Fibronectin immunostaining of ECM produced by human breast cancer CAFs infected with control scrambled shRNA or SNAIL1 shRNA (–SNAIL1), and normal human breast fibroblasts (NF). (D) The degree of global order of fibronectin fibers from images in C. shSCR, scrambled shRNA; shSN, SNAIL1 shRNA. This experiment was performed three times (n=3). Results are presented as mean±s.d. *P<0.05; NS, not significant (unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests). Scale bars: 50 μm. (E) SHG images of collagen fiber production and organization in matrix produced by cultured human breast cancer CAFs and CAFs depleted of SNAIL1 with shRNA (–SNAIL1).

We performed quantitative real-time PCR (Q-PCR) analysis of select gene sets that impact upon ECM matrix production and remodeling to determine whether SNAIL1 affected their transcription following exposure to a stiff matrix. Transcription of collagens, collagen-modifying lysyl-oxidase genes (LOX), TGFβs and metalloproteinases (MMPs) generally increased in WT CAFs following their exposure to a stiff matrix (Fig. 7B). When SNAIL1 was depleted by use of shRNA in CAFs, this response was significantly diminished for most genes analyzed, whereas depletion of YAP did not affect transcription of LOX genes, only minimally affected collagen and MMP gene transcription, but did reduce TGFβ gene transcription (Fig. 7B). The absence of SNAIL1 only slightly affected the transcription of the YAP-dependent genes ANKRD1, CTGF and SPDR (Calvo et al., 2013) (Fig. S4B).

Next, we determined and contrasted the nature of the ECM produced by CAFs and CAFs lacking SNAIL1. As reported by Stanisavljevic et al. (2015) , we also observed that matrix produced by WT CAFs, as assessed by fibronectin fiber organization (Fig. 7C) and second harmonic generation (SHG) analysis of collagen fibers (Fig. 7E), was highly organized into linear tracks. In CAFs lacking SNAIL1, the fibronectin matrix produced was more disorganized, similar to that produced by normal breast fibroblasts (Fig. 7C, quantified in Fig. 7D), and there was decreased collagen fiber production as determined by SHG analysis (Fig. 7E).

In sum, these data indicate that when human breast tumor CAFs are exposed to a stiff ECM, SNAIL1 protein level increased and accumulated in the nucleus. Nuclear accumulation of SNAIL1 enhanced the transcription of fibrogenic genes, and subsequent production and organization of the ECM. In contrast, although control YAP protein level also increased and accumulated in the nucleus it exerted little effect upon the transcription of fibrogenic genes in CAFs following exposure to a stiff matrix.

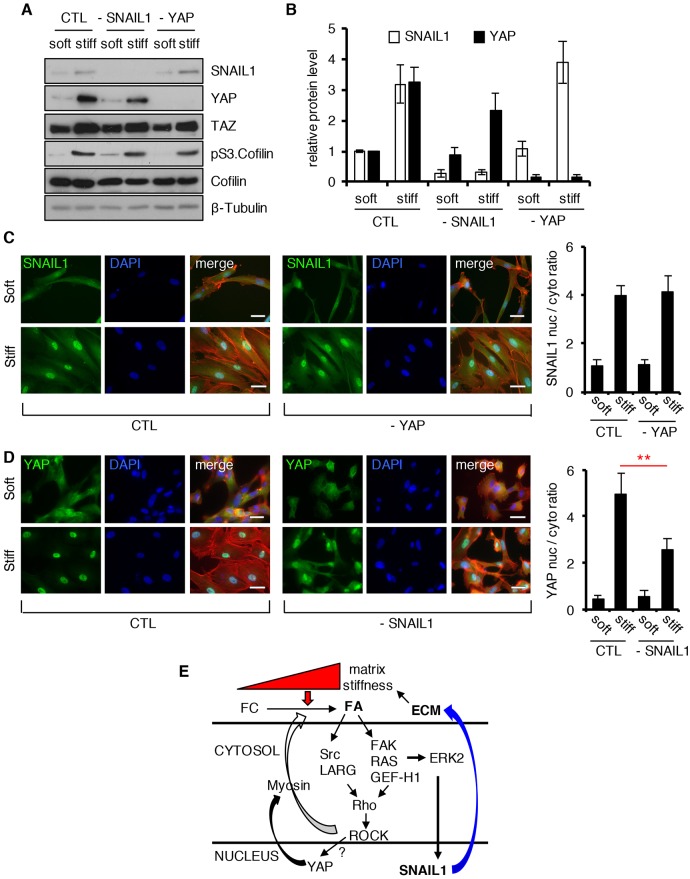

SNAIL1 affects YAP activity in response to mechanical signals

Given that both YAP and SNAIL1 have been implicated in CAF function (Calvo et al., 2013; Stanisavljevic et al., 2015), and both are stabilized and activated in cells exposed to a stiff matrix (Dupont et al., 2011 and data herein), we asked whether the absence of one affected the activity of the other. shRNA-mediated depletion of YAP in CAFs did not affect the SNAIL1 protein level (Fig. 8A, quantified in Fig. 8B) or nuclear accumulation (Fig. 8C) when cells were exposed to a stiff matrix. However, when SNAIL1 was depleted in CAFs, YAP protein level (Fig. 8A, quantified in Fig. 8B), YAP nuclear accumulation (Fig. 8D), and the YAP or TEAD transcriptional activity (Fig. S4C, quantified in Fig. S4D) were modestly decreased following exposure of cells to a stiff matrix. This indicated that in CAFs, SNAIL1 influenced the activity of YAP following exposure to external mechanical signals, whereas the presence of YAP did not affect SNAIL1 protein level or nuclear accumulation.

Fig. 8.

SNAIL1 affects YAP activity in response to mechanical signals. (A) Human breast tumor CAFs were infected with lentiviruses expressing shRNA targeting SNAIL1 (–SNAIL1) or YAP (–YAP) or with scrambled shRNA (CTL) and then plated on fibronectin-coated soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) hydrogels for 12 h. Western blotting on cell extracts was performed with the indicated antibodies. (B) Quantification of the relative protein level of SNAIL1 and YAP in the experiment described in A. Level of protein in control cells on soft substrate was arbitrarily set at 1. (C,D) Immunofluorescent staining for SNAIL1 (C) or YAP (D) (green), F-actin (Rhodamine–phalloidin, red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in human CAFs cells plated on fibronectin-coated soft (80–120 Pa) or stiff (120 kPa) hydrogels for 12 h. Histograms on right quantify the nuclear-to-cytosolic fluorescent intensity ratio of SNAIL1 (C) or YAP (D) using ImageJ software. Bars represent mean±s.d. More than 50 cells, in multiple fields were scored. **P<0.01 (unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests). Scale bars: 20 μm. (E) Summary of mechanotransduction regulation of SNAIL1 protein and resultant cellular response in CAFs. FC, focal complex; FA, focal adhesion.

DISCUSSION

Increases in tissue stiffness are largely due to increased deposition and cross-linking of fibrillar collagen, and is frequently associated with cancer, especially breast cancer. This physical change in the tumor environment can cause progression of disease (Paszek et al., 2005), and when present predicts for poor clinical outcome and response to therapy (Hasebe et al., 2002; Provenzano et al., 2008). Herein, we show in CAFs and breast tumor cells that the transcriptional regulator SNAIL1 protein level increases and accumulates in the nucleus in response to exposure to mechanical signals, such as a stiff ECM. Exposure of breast tumor CAFs to a stiff matrix increased their fibrogenesis and SNAIL1 was crucial for this response. These results suggest a model of a feed-forward cycle whereby stiffness in the tumor environment sustains fibrogenesis and tumor fibrosis by maintaining the level and activity of SNAIL1 in CAFs (Fig. 8E). SNAIL1 already has well described functions in tumor cells, where it can influence tumor-initiating cells and the invasion and metastasis of tumor cells (Ye et al., 2015; Moody et al., 2005; Tran et al., 2014). Less appreciated, perhaps, is the importance of SNAIL1 in mesenchymal cells (e.g. CAFs) within the tumor stroma in the regulation of metastasis.

The Hippo pathway transcriptional co-activator YAP is also regulated by mechanical signals in CAFs and regulates intracellular tension generation (Dupont et al., 2011; Calvo et al., 2013). We find that mechanical regulation of YAP and SNAIL1 in CAFs differs. YAP is predominantly regulated by the increase in intracellular Rho–ROCK activity and is independent of ERK2 activity, whereas SNAIL1 is regulated predominantly by an indirect increase in ERK2 activity, which occurs as a result of increased integrin activation mediated by intracellular tension (e.g. ROCK) (Fig. 8E). YAP is thought to be regulated by F-actin dynamics (Aragona et al., 2013). In tumor-associated CAFs, YAP regulates ECM remodeling by increasing intracellular tension (Calvo et al., 2013) whereas, as shown herein and elsewhere SNAIL1 regulates fibrogenesis (Stanisavljevic et al., 2015).

Within the tumor environment, other cells and factors can also influence the fibrogenic response of CAFs. This can include immune cells and inflammatory mediators secreted by tumor cells, tumor-associated immune cells and CAFs (Wynn and Ramalingam, 2012). Along these lines, SNAIL1 in tumor cells has recently been shown to modulate cytokine secretion that affected recruitment of myeloid cells into the tumor environment (Hsu et al., 2014). This effect of SNAIL1 could also be contributing to fibrogenic regulation in tumors in vivo.

Interestingly, depletion of SNAIL1 in CAFs led to a modest reduction in YAP protein level and activity following exposure to stiff ECM. Precisely how this occurs is unclear. Recently, in endothelial cells, YAP has been shown to regulate TGFβ-induced SNAIL1 upregulation (Zhang et al., 2014) and, in the developing heart, YAP interacts with β-catenin to affect transcription of SNAIL2 (Heallen et al., 2011). SNAIL1 has also been shown to interact with β-catenin (Stemmer et al., 2008).

Another EMT regulator TWIST1 has been found, in breast tumor cells, to be responsive to mechanical signals (Wei et al., 2015). TWIST1 promotes tumor EMT in response to exposure to a stiff matrix. In contrast to SNAIL1, matrix stiffness did not affect the TWIST1 protein level although it did induce its nuclear localization. Interestingly, the authors noted that the mechanotransduction pathways regulating TWIST1 were, like SNAIL1, distinct from YAP regulation. In that work, CAFs were not examined; however, another report studying gastric cancer CAFs has found that TWIST1 is important for the differentiation of normal tissue fibroblasts into CAFs (Lee et al., 2015). We also noted that TWIST1 protein levels increased as fibroblasts evolved from normal tissue fibroblasts to CAFs (Fig. 7A). Whether TWIST1 contributes to breast tumor CAF function is not known; however, deletion of SNAIL1 clearly altered CAF functions (e.g. tumor fibrosis) that affect tumor progression, invasion, metastasis and response to therapy, despite the continued presence of TWIST1. In sum, the TWIST1 data, our SNAIL1 data herein, and the SNAIL1 data from Stanisavljevic et al. (2015) suggest that the primary role for TWIST1 in breast tumorigenesis could be in the tumor cell, whereas SNAIL1 function might be most important in CAFs, although genetic data also supports a role for SNAIL1 in tumor cells (Moody et al., 2005; Tran et al., 2014; Ye et al., 2015).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

High-throughput screens

Human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing a SNAIL1–CBG bioluminescent reporter (Zhang et al., 2011) were generated. 20,000 cells per well were seeded in black-walled 96-well plates with 100 μl Phenol-Red-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). At 24 h following cell plating, with a 96 multichannel head on the FX liquid handler, the original medium was removed from plates and replaced with 130 μl/well Phenol-Red-free DMEM with 10% FBS supplemented with individual compounds in the PHARMAKON 1600 (MicroSource Discovery Systems, Gaylordsville, CT) machine at a final concentration of 10 μM. The experimental compounds being screened were arrayed in columns 2–11 of each plate. Three wells treated with DMSO (0.5%, negative vehicle control) or MG132 (Sigma, 10 μM, positive control) were placed in columns 1 and 12 on each plate. The luminescent signal was measured in an ultrasensitive detection mode on an EnVision plate reader (Perkin-Elmer) every 4 h for 24 h in the presence of compound. Cell viability was then determined as conversion of Resazurin dye (Sigma R7017) (final concentration 44 μM) to Resorufin after 4 h incubation at 37°C, monitored at 590 nm on a FLUOstar OPTIMA fluorescence reader (BMG Labtech) excited at 544 nm. For each compound, the Z-scores (MAD) for all compounds (three independent plates) were averaged (Zhang et al., 2006). Targets with a MAD of at least three were selected as potential hits for further identification.

Cell culture, plasmids and lentiviral infections

MDA-MB-231 cells were from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). H-tert-immortalized human breast-tumor-associated fibroblast cells (CAFs) and normal breast fibroblasts were provided by Sandy McAllister (Harvard Medical School, Cambridge, MA). HEK293 and MDA-MB-231 clones stably expressing SNAIL1-CBG were as described previously (Zhang et al., 2011, 2013). Production of lentiviruses and infection of target cells were as described previously (Zhang et al., 2013). To make stable MDA-MB-231 and CAF cell lines, cells were selected in 2 μg/ml puromycin.

STBS-Luciferase (a YAP and TEAD transcriptional reporter) was provided by Fernando D. Camargo (Harvard University, Cambridge, MA) (Mohseni et al., 2014). Double copy lentiviruses expressing an shRNA that specifically targets SNAIL1 and an shRNA-resistant SNAIL1 isoform or mutant isoforms of SNAIL1 were generated as previously described (Feng et al., 2010). Flag-tagged constitutively activated RhoA (Q63L) was subcloned into a pFLRu construct. shRNAs were from the Broad collection (Washington University Genome Center). There were five to seven shRNAs for each target. All were screened and at least two or three used for all targets. shRNA target sequences used are listed in Table S3.

Antibodies and chemicals

For antibodies and dilutions used for western blotting, immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry see Table S1. The ROCK kinase inhibitor Fasudil was from MicroSource Discovery Systems Inc (Gaylordsville, CT); Y-27632 was from Sigma (St Louis, MO); PD98059 and SB203580 were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA); and TGF-β inhibitor SB431542 was from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Type I collagen and Fibronectin were from BD Biosciences (Bedford, MA). Rhodamine–phalloidin was from Invitrogen. Mounting medium with DAPI was from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA).

Hydrogels

Polyacrylamide substrates were fabricated as described previously (Elkabets et al., 2011). Briefly, acrylamide solution (Bio-Rad) was mixed with N-N′-methylene-bis-acrylamide solutions (Bio-Rad) and then polymerized between a glutaraldehyde-activated glass surface and hydrophobic coverslip. Polymerized substrates were then activated for protein conjugation with the heterobifunctional crosslinker Sulfo-SANPAH at 0.5 mg/ml (Pierce Chemical) under UV exposure for 15 min. After washing with HEPES buffer, functionalizing with fibronectin or type I collagen at a nominal surface density of 2.6 µg/cm was performed (Elkabets et al., 2011). Elastic moduli were determined by atomic force microscopy. Soft substrates were 80–120 Pa, whereas stiff substrates were 120 kPa.

Western blotting

Unless stated otherwise, all protein lysates were obtained from cells seeded overnight in DMEM with 5% FBS on top of polyacrylamide gel coated with fibronectin or type I collagen. Protein lysates were processed following standard procedures. Antibody description and working dilutions used can be found in Table S1.

Bioluminescence imaging

Bioluminescence measurements on MDA-MB-231 (SNAIL1–CBG) and CAFs (STBS–Luc) cells were acquired in an IVIS 100 imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA) at 37°C under 5% CO2 flow. Bioluminescence photon flux (photons/s) data were analyzed by region of interest (ROI) measurements in Living Image 3.2 (Caliper Life Sciences). This raw data was imported into Excel (Microsoft Corp.) and normalized to controls.

In vivo mammary tumor SNAIL1 expression assay

Cells for transplantation were prepared by isolating primary cancer epithelial cells from mouse mammary tumors (<2 cm in size) extracted from FVB MMTV-PyMT mice. Tumor samples were rinsed with antibiotic, minced, digested in collagenase with trypsin, treated with DNase and tumor epithelial cells separated out by differential centrifugation. The cells were then cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with serum, insulin, hydrocortisone and glutamine. For transplants, 8-week-old FVB (Charles River Laboratories) or FVB Colα1tmJae mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane (1.5% in oxygen), and the isolated primary PyMT tumor cells (1×106) in 50 µl DMEM/F12 were injected into the fourth mammary gland without clearing. Four weeks post surgery, the mice were killed and the resulting tumor and contralateral fourth normal mammary gland were removed. A portion of the tumor was processed for whole-tumor tissue lysate by suspending in 9 M urea lysis buffer containing 5% 0.1 M dithiothreitol and homogenizing using a high-speed tissue homogenizer followed by sonication. The remaining tumor tissue and normal mammary gland were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h, and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin blocks were sectioned with a microtome (6 µm) and stained with Picosirius Red for histological analysis. All mouse work was approved by the Washington University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

ECM production by CAFs in culture and analyses

3×105 cells were plated on 12-mm glass coverslips in DMEM with 10% FBS containing 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid. Medium was changed daily for 7 days. Cells were extracted on day 7 with a minimal amount of pre-warmed cell extraction buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM sodium chloride, 0.5% Triton X-100 and 20 mM ammonia hydroxide) for 3–5 min. Cellular debris was carefully washed away with 1× PBS. Resultant cell-free ECM was fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min at room temperature. Cell-free ECM was incubated in mouse anti-fibronectin antibody (BD Biosciences, 610077) overnight at 4°C, washed twice, and then incubated with goat anti-mouse-IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies, A11001) for 1 h at room temperature. ECM was then washed four times, mounted in Vectashield (VWR, 101098-044), and sealed with nail polish. Immunofluorescence was performed on a confocal microscope (LSM 700; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) at room temperature with Zen 2009 software. ImageJ was used to adjust brightness and contrast. The degree of global order of matrix fibers was measured using a sub-window 2D Fourier transform method (Cetera et al., 2014; Sander and Barocas, 2009).

Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were grown on fibronectin-coated polyacrylamide hydrogel overnight or plated onto fibronectin-coated micropatterned coverslips with different sizes of square adhesive islands (300, 1024, 2025 and 10,000 μm2) (Cytoo SA, Grenoble, France). Single cells were allowed to adhere for 6 h. Subsequently cells were washed, fixed, permeabilized, blocked and stained. Fluorescence was detected using a Nikon ELIPSE Ti microscope. Images were acquired as sets of color images and prepared and quantified using ImageJ software.

SHG imaging of collagen fibers

The collagen matrix images were observed using multiphoton laser scanning microscopy (MPLSM) and SHG on a custom-built multiphoton microscope platform with an excitation source produced by a Spectra Physics Mai Tai DeepSee laser (Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA), tuned to a wavelength of 890 nm, mounted around a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). Images were focused onto a Nikon 20× Plan Apo mullit-immersion lens (numerical aperture 1.4), and SHG emission was observed at 445 nm and discriminated from fluorescence using a 445-nm and 20-nm narrow bandpass emission filter (Semrock, Inc., Lake Forest, IL).

Real-time RT-PCR and fibrosis gene array analysis

Real-time PCR (Q-PCR) reactions were performed using the SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in the ABI detection system (Applied Biosystems). The thermal cycling conditions were composed of 95°C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s. The experiments were carried out in triplicate for each data point. The relative quantification in gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Primers used for RT-PCR and Q-PCR are listed in Table S2. The fibrosis gene array was examined with RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array (Human Fibrosis) from Qiagen. Data were analyzed with web-based software (Qiagen) using the comparative cycle threshold method normalized to expression of housekeeping genes.

Statistics

Results are expressed as the mean±s.d. Comparisons among groups were performed, with P-values calculated using unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-tests (*P<0.05; **P<0.01). For each experiment there were at least three experimental runs for each point and each experiment was performed at least two times.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

K.Z., W.R.G., S.V.H., H.B. and S.M.P. were involved in project planning, experimental work and data analysis. K.W.E., P.J.K. and G.D.L. were involved in project planning and data analysis. G.D.L. wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers P50CA94056 to the Imaging Core of the Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University, CA143868 to G.D.L.]; and Susan G. Komen for the Cure [grant number KG110889 to G.D.L.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/jcs.180539/-/DC1

References

- Aragona M., Panciera T., Manfrin A., Giulitti S., Michielin F., Elvassore N., Dupont S. and Piccolo S. (2013). A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell 154, 1047-1059. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber S., Barbayannis F. A., Hanser H., Schneider C., Stanyon C. A., Bernard O. and Caroni P. (1998). Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature 393, 805-809. 10.1038/31729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batlle R., Alba-Castellón L., Loubat-Casanovas J., Armenteros E., Francí C., Stanisavljevic J., Banderas R., Martin-Caballero J., Bonilla F., Baulida J. et al. (2013). Snail1 controls TGF-beta responsiveness and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Oncogene 32, 3381-3389. 10.1038/onc.2012.342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick N. A., Neilson E. G. and Moses H. L. (2004). Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression. Nature 432, 332-337. 10.1038/nature03096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo F., Ege N., Grande-Garcia A., Hooper S., Jenkins R. P., Chaudhry S. I., Harrington K., Williamson P., Moeendarbary E., Charras G. et al. (2013). Mechanotransduction and YAP-dependent matrix remodelling is required for the generation and maintenance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 637-646. 10.1038/ncb2756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetera M., Ramirez-San Juan G. R., Oakes P. W., Lewellyn L., Fairchild M. J., Tanentzapf G., Gardel M. L. and Horne-Badovinac S. (2014). Epithelial rotation promotes the global alignment of contractile actin bundles during Drosophila egg chamber elongation. Nat. Commun. 5, 5511 10.1038/ncomms6511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin M. W., Eickhoff J. C., Riching K. M., Pehlke C. A., Eliceiri K. W., Provenzano P. P., Friedl A. and Keely P. J. (2011). Aligned collagen is a prognostic signature for survival in human breast carcinoma. Am. J. Pathol. 178, 1221-1232. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont S., Morsut L., Aragona M., Enzo E., Giulitti S., Cordenonsi M., Zanconato F., Le Digabel J., Forcato M., Bicciato S. et al. (2011). Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474, 179-183. 10.1038/nature10137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkabets M., Gifford A. M., Scheel C., Nilsson B., Reinhardt F., Bray M.-A., Carpenter A. E., Jirström K., Magnusson K., Ebert B. L. et al. (2011). Human tumors instigate granulin-expressing hematopoietic cells that promote malignancy by activating stromal fibroblasts in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 784-799. 10.1172/JCI43757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engler A. J., Sen S., Sweeney H. L. and Discher D. E. (2006). Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126, 677-689. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esnault C., Stewart A., Gualdrini F., East P., Horswell S., Matthews N. and Treisman R. (2014). Rho-actin signaling to the MRTF coactivators dominates the immediate transcriptional response to serum in fibroblasts. Genes Dev. 28, 943-958. 10.1101/gad.239327.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Nie L., Thakur M. D., Su Q., Chi Z., Zhao Y. and Longmore G. D. (2010). A multifunctional lentiviral-based gene knockdown with concurrent rescue that controls for off-target effects of RNAi. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 8, 238-245. 10.1016/S1672-0229(10)60025-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francí C., Takkunen M., Dave N., Alameda F., Gomez S., Rodríguez R., Escrivà M., Montserrat-Sentís B., Baro T., Garrido M. et al. (2006). Expression of Snail protein in tumor-stroma interface. Oncogene 25, 5134-5144. 10.1038/sj.onc.1209519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaggioli C., Hooper S., Hidalgo-Carcedo C., Grosse R., Marshall J. F., Harrington K. and Sahai E. (2007). Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1392-1400. 10.1038/ncb1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardel M. L., Sabass B., Ji L., Danuser G., Schwarz U. S. and Waterman C. M. (2008). Traction stress in focal adhesions correlates biphasically with actin retrograde flow speed. J. Cell Biol. 183, 999-1005. 10.1083/jcb.200810060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasebe T., Sasaki S., Imoto S., Mukai K., Yokose T. and Ochiai A. (2002). Prognostic significance of fibrotic focus in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast: a prospective observational study. Mod. Pathol. 15, 502-516. 10.1038/modpathol.3880555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heallen T., Zhang M., Wang J., Bonilla-Claudio M., Klysik E., Johnson R. L. and Martin J. F. (2011). Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science 332, 458-461. 10.1126/science.1199010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu D. S.-S., Wang H.-J., Tai S.-K., Chou C.-H., Hsieh C.-H., Chiu P.-H., Chen N.-J. and Yang M.-H. (2014). Acetylation of snail modulates the cytokinome of cancer cells to enhance the recruitment of macrophages. Cancer Cell 26, 534-548. 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey J. D., Dufresne E. R. and Schwartz M. A. (2014). Mechanotransduction and extracellular matrix homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 802-812. 10.1038/nrm3896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.-W., Yeo S.-Y., Sung C. O. and Kim S.-H. (2015). Twist1 is a key regulator of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cancer Res. 75, 73-85. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P., Weaver V. M. and Werb Z. (2012). The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J. Cell Biol. 196, 395-406. 10.1083/jcb.201102147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni M., Sun J., Lau A., Curtis S., Goldsmith J., Fox V. L., Wei C., Frazier M., Samson O., Wong K. K. et al. (2014). A genetic screen identifies an LKB1–MARK signalling axis controlling the Hippo–YAP pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 16, 108-117. 10.1038/ncb2884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody S. E., Perez D., Pan T.-c., Sarkisian C. J., Portocarrero C. P., Sterner C. J., Notorfrancesco K. L., Cardiff R. D. and Chodosh L. A. (2005). The transcriptional repressor Snail promotes mammary tumor recurrence. Cancer Cell 8, 197-209. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszek M. J., Zahir N., Johnson K. R., Lakins J. N., Rozenberg G. I., Gefen A., Reinhart-King C. A., Margulies S. S., Dembo M., Boettiger D. et al. (2005). Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell 8, 241-254. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano P. P., Eliceiri K. W., Campbell J. M., Inman D. R., White J. G. and Keely P. J. (2006). Collagen reorganization at the tumor-stromal interface facilitates local invasion. BMC Med. 4, 38 10.1186/1741-7015-4-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano P. P., Inman D. R., Eliceiri K. W., Knittel J. G., Yan L., Rueden C. T., White J. G. and Keely P. J. (2008). Collagen density promotes mammary tumor initiation and progression. BMC Med. 6, 11 10.1186/1741-7015-6-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzano P. P., Inman D. R., Eliceiri K. W. and Keely P. J. (2009). Matrix density-induced mechanoregulation of breast cell phenotype, signaling and gene expression through a FAK–ERK linkage. Oncogene 28, 4326-4343. 10.1038/onc.2009.299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder B. A., Kokini K., Sturgis J. E., Robinson J. P. and Voytik-Harbin S. L. (2002). Tensile mechanical properties of three-dimensional type I collagen extracellular matrices with varied microstructure. J. Biomech. Eng. 124, 214-222. 10.1115/1.1449904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R. G., Li X.-Y., Hu Y., Saunders T. L., Virtanen I., de Herreros A. G., Becker K.-F., Ingvarsen S., Engelholm L. H. et al. (2009). Mesenchymal cells reactivate Snail1 expression to drive three-dimensional invasion programs. J. Cell Biol. 184, 399-408. 10.1083/jcb.200810113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander E. A. and Barocas V. H. (2009). Comparison of 2D fiber network orientation measurement methods. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 88A, 322-331. 10.1002/jbm.a.31847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon Y., Alon L., Glanz S., Servais C. Erez E. (2013). Isolation of normal and cancer-associated fibroblasts from fresh tissues by Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACSa). J. Vis. Exp. 71, e4425 10.3791/4425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanisavljevic J., Loubat-Casanovas J., Herrera M., Luque T., Pena R., Lluch A., Albanell J., Bonilla F., Rovira A., Pena C. et al. (2015). Snail1-expressing fibroblasts in the tumor microenvironment display mechanical properties that support metastasis. Cancer Res. 75, 284-295. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stemmer V., de Craene B., Berx G. and Behrens J. (2008). Snail promotes Wnt target gene expression and interacts with beta-catenin. Oncogene 27, 5075-5080. 10.1038/onc.2008.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H. D., Luitel K., Kim M., Zhang K., Longmore G. D. and Tran D. D. (2014). Transient SNAIL1 expression is necessary for metastatic competence in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 74, 6330-6340. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. B., Dembo M. and Wang Y. L. (2000). Substrate flexibility regulates growth and apoptosis of normal but not transformed cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C1345-C1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S. C., Fattet L., Tsai J. H., Guo Y., Pai V. H., Majeski H. E., Chen A. C., Sah R. L., Taylor S. S., Engler A. J. et al. (2015). Matrix stiffness drives epithelial–mesenchymal transition and tumour metastasis through a TWIST1–G3BP2 mechanotransduction pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 678-688. 10.1038/ncb3157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong V. W., Rustad K. C., Akaishi S., Sorkin M., Glotzbach J. P., Januszyk M., Nelson E. R., Levi K., Paterno J., Vial I. N. et al. (2012). Focal adhesion kinase links mechanical force to skin fibrosis via inflammatory signaling. Nat. Med. 18, 148-152. 10.1038/nm.2574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn T. A. and Ramalingam T. R. (2012). Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. Nat. Med. 18, 1028-1040. 10.1038/nm.2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X., Tam W. L., Shibue T., Kaygusuz Y., Reinhardt F., Ng Eaton E. and Weinberg R. A. (2015). Distinct EMT programs control normal mammary stem cells and tumour-initiating cells. Nature 525, 256-260. 10.1038/nature14897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yook J. I., Li X.-Y., Ota I., Hu C., Kim H. S., Kim N. H., Cha S. Y., Ryu J. K., Choi Y. J., Kim J. et al. (2006). A Wnt–Axin2–GSK3beta cascade regulates Snail1 activity in breast cancer cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1398-1406. 10.1038/ncb1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. D., Yang X. C., Chung N., Gates A., Stec E., Kunapuli P., Holder D. J., Ferrer M. and Espeseth A. S. (2006). Robust statistical methods for hit selection in RNA interference high-throughput screening experiments. Pharmacogenomics 7, 299-309. 10.2217/14622416.7.3.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Rodriguez-Aznar E., Yabuta N., Owen R. J., Mingot J. M., Nojima H., Nieto M. A. and Longmore G. D. (2011). Lats2 kinase potentiates Snail1 activity by promoting nuclear retention upon phosphorylation. EMBO J. 31, 29-43. 10.1038/emboj.2011.357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Corsa C. A., Ponik S. M., Prior J. L., Piwnica-Worms D., Eliceiri K. W., Keely P. J. and Longmore G. D. (2013). The collagen receptor discoidin domain receptor 2 stabilizes SNAIL1 to facilitate breast cancer metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 677-687. 10.1038/ncb2743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., von Gise A., Liu Q., Hu T., Tian X., He L., Pu W., Huang X., He L., Cai C.-L. et al. (2014). Yap1 is required for endothelial to mesenchymal transition of the atrioventricular cushion. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 18681-18692. 10.1074/jbc.M114.554584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B., Li L., Tumaneng K., Wang C.-Y. and Guan K.-L. (2010). A coordinated phosphorylation by Lats and CK1 regulates YAP stability through SCF (beta-TRCP). Genes Dev. 24, 72-85. 10.1101/gad.1843810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B. P., Deng J., Xia W., Xu J., Li Y. M., Gunduz M. and Hung M. C. (2004). Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3beta-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 931-940. 10.1038/ncb1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]