Abstract

Polysplenism and accessory spleen are congenital, usually asymptomatic anomalies. A rare case of polysplenism with ectopic spleen in pelvis of a 67-year-old, Caucasian female is reported here. A transvaginal ultrasound found a soft well-defined homogeneous and vascularized mass in the left pelvis. Patient underwent MRI evaluation and contrast-CT abdominal scan: images with parenchymal aspect, similar to spleen were obtained. Abdominal scintigraphy with 99mTc-albumin nanocolloid was performed and pelvic region was studied with planar scans and SPECT. The results showed the presence of an uptake area of the radiopharmaceutical in the pelvis, while the spleen was normally visualized. These findings confirmed the presence of an accessory spleen with an artery originated from the aorta and a vein that joined with the superior mesenteric vein. To our knowledge, in the literature, there is just only one case of a true ectopic, locally vascularized spleen in the pelvis.

Keywords: True ectopic, Accessory spleen, Scintigraphy, Ultrasound

Riassunto

Il polisplenismo e la milza accessoria sono anomalie congenite generalmente asintomatiche. Riportiamo un raro caso di polisplenismo con milza pelvica ectopica in una donna bianca di 67 anni. Nella pelvi di sinistra all’ecografia transvaginale è stata ritrovata una massa soffice, ben definita, omogenea e vascolarizzata. La paziente è stata quindi sottoposta a valutazione con RM e TC addominale con contrasto: sono state ottenute immagini con aspetto parenchimale simile alla milza. E’ stata eseguita una scintigrafia addominale con albumina umana colloidale radiomarcata con tecnezio sulla regione pelvica con scansioni planari e SPECT. I risultati hanno mostrato la presenza di un’area di captazione del radiofarmaco nella pelvi, mentre la milza è stata normalmente visualizzata. Questi ritrovamenti hanno confermato la presenza di una milza accessoria con una arteria originante dall’aorta ed una vena che si anastomizzava con la vena mesenterica superiore. Alla nostra conoscenza, nella letteratura, esiste solo un caso di vera milza ectopica localmente vascolarizzata nella pelvi.

Introduction

Polysplenism and accessory spleen are congenital, usually asymptomatic, anomalies found between approximately 10 and 30 % of the population [1], with an autoptic ectopic spleen incidence of 17 % [2]. Ectopia can possibly occur, even if less frequent, in the pelvic area [3].

A case of polysplenism with ectopic spleen in the pelvis is reported herein.

Case report

An asymptomatic 67-year-old Caucasian female with an incidental transvaginal ultrasound finding (Fig. 1) of a soft well-defined homogeneous and vascularized mass in the left pelvis underwent an MRI evaluation. The MRI (Signa GE Healthcare, 1.5T, Milwaukee, USA) showed a 3 × 2 cm ovular mass in the left side of the pelvis, in the presacral adipose tissue, with T1, T2, and DWI images compatible with the parenchymal aspect similar to the spleen (Fig. 2). The study showed the presence of a long vascular pedicle with an artery that originated from the aorta (1.5 cm away from the origin of renal arteries) and a vein that joined with the superior mesenteric vein, just before the portal vein. The spleen was in the regular site and was normal in size, and polysplenism was found, with small masses near the splenic hilum.

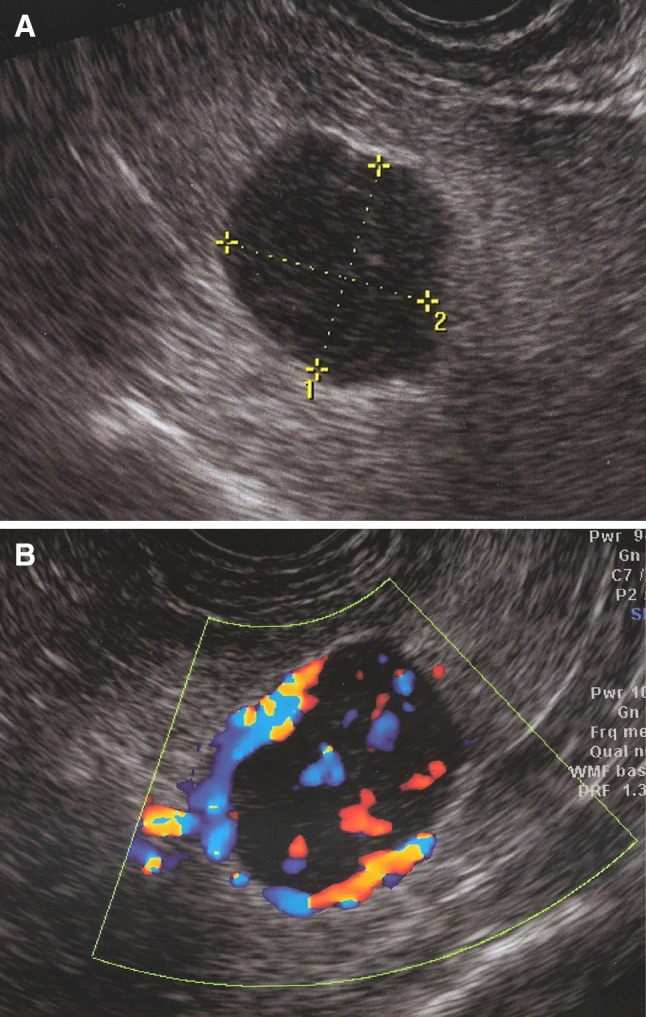

Fig. 1.

Ultrasonography demonstrates a a hypoechogenic well-marginated nontransonic presacral mass showing a b peri-intra vascularization color Doppler pattern

Fig. 2.

Sagittal T2-weighted MRI shows 3 × 2 cm well-marginated presacral mass with intensity signal similar to the spleen

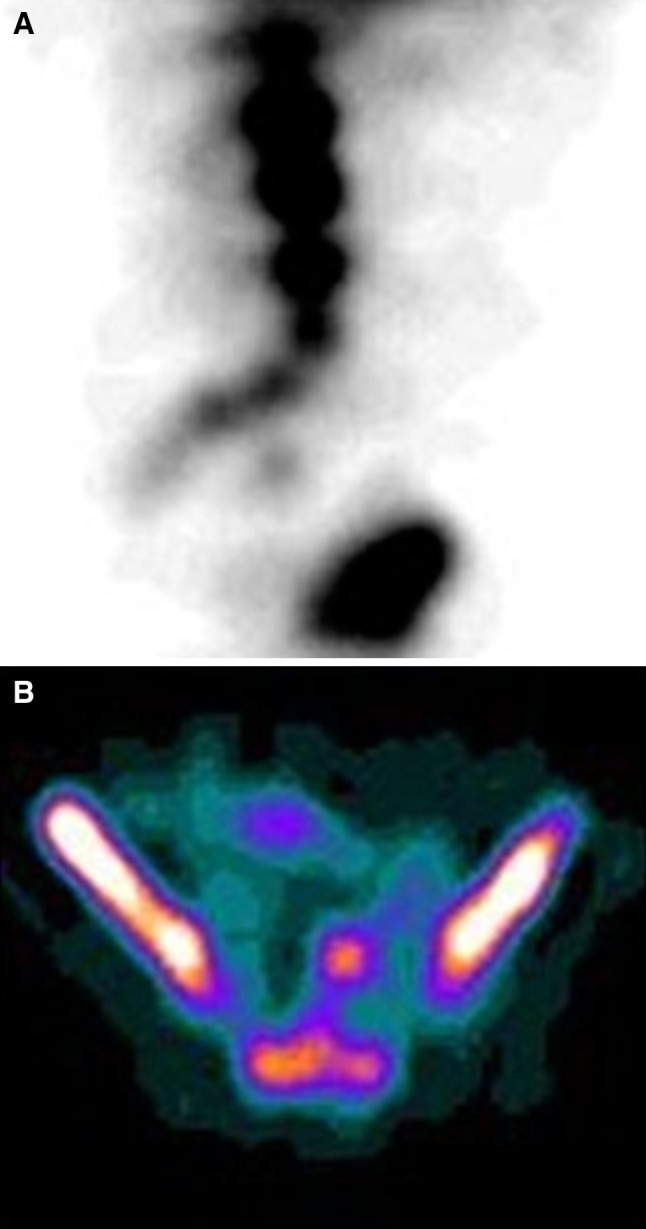

A contrast abdominal CT scan (Optima, GE Healthcare, 64S, Milwaukee, USA) confirmed these results (Fig. 3). An abdominal scintigraphy with 99mTc-albumin nanocolloid (Nanotop, ROTOP Pharmaka GmbH, Dresden, D, 200 MBq e.v.) was performed by a large field-of-view gamma camera (Infinia, G.E. Healthcare, Milwaukee, USA) (Fig. 4). The maximum concentration of radioactivity in the liver and spleen occurred within 10–20 min from the injection of the radiopharmaceutical, and after 30 min, abdominal and pelvic regions were studied with planar scans and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). The results showed the presence of an uptake area of the radiopharmaceutical in the pelvis, while the spleen was normally visualized. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of accessory spleen. The patient did not undergo further invasive procedures, and an ultrasonographic follow-up was proposed instead.

Fig. 3.

Volume rendering CT images of a arterial and b portal phases show arterial and venous mass supply (see text)

Fig. 4.

a 99mTc-albumin nanocolloid coronal and b sagittal SPECT imaging demonstrates radiotracer uptake in the pelvic mass, confirming the diagnosis of accessory spleen

Discussion

The spleen appears approximately at the sixth week of embryologic life as a localized thickening of the coelomic epithelium of the dorsal mesogastrium near its cranial end. The proliferating cells invade the underlying angiogenic mesenchyme, which becomes condensed and vascularized. The process occurs simultaneously in several adjoining areas, which soon fuse to form a lobulated spleen. In the subsequent periods of embryologic life, the earlier lobulated character of the spleen disappears but is indicated in the adult by the presence of notches on its upper border [4]. Accessory spleens may form during the embryonic development as an ectopic or separated splenic tissue along the path between the place where the spleen is formed at the midline and the final location of the organ on the left side of the abdomen.

The computed tomography scan with intravenous contrast is very useful in delineating the vascular pedicle of the accessory spleen, but the magnetic resonance imaging is also used to evaluate tissue aspects. However, only the nuclear medicine imaging can confirm the diagnosis, with liver and spleen scintigraphy performed with 99mTc-labeled colloids. This scan localizes the reticuloendothelial cells of the liver and/or spleen and also shows the presence of any anomalous areas of uptake of the radiopharmaceutical scattered in the abdomen in different locations from those typical of the above-mentioned organs.

To our knowledge, there is only one case of a true ectopic, locally vascularized spleen in the pelvis, whereas all other cases of accessory spleens in the pelvis quoted in the literature are vascularized by the splenic artery [5].

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

None to disclose.

Ethical standard statement

Ethics committee approval was obtained before beginning any research involving human subjects or clinical information.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. All patients provided written informed consent for enrolment in the study and for the inclusion in this article of information that could potentially lead to their identification.

References

- 1.Gardakis S, Pitiakoudis M, Sigalas I, et al. Infarction of an accessory spleen presenting as acute abdomen in a neonate. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2005;15:203–205. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unver Dogan N, Uysal II, Demirci S, et al. Accessory spleens at autopsy. Clin Anat. 2011;24:757–762. doi: 10.1002/ca.21146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsiao SM, Lee LC, Chang MH. Large pelvic accessory spleen mimicking an adnexal malignancy in a teenage girl. J Formos Med Assoc. 2001;100:565–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Üngor B, Malas MA, Sulak O, et al. Development of the spleen during the foetal period. Surg Radiol Anat. 2007;29:543–550. doi: 10.1007/s00276-007-0240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darius T, Tollens T, Chr Aelvoet, et al. True ectopic, locally vascularized spleen: a very rare anomaly. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109:419–420. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2009.11680453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]