Abstract

Adolescence is a period of major behavioral and brain reorganization. As diagnoses and treatment of disorders like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) often occur during adolescence, it is important to understand how the prefrontal cortices change and how these changes may influence the response to drugs during development. The current study uses an adolescent rat model to study the effect of standard ADHD treatments, atomoxetine and methylphenidate on attentional set shifting and reversal learning. While both of these drugs act as norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, higher doses of atomoxetine and all doses of methylphenidate also block dopamine transporters (DAT). Low doses of atomoxetine, were effective at remediating cognitive rigidity found in adolescents. In contrast, methylphenidate improved performance in rats unable to form an attentional set due to distractibility but was without effect in normal subjects. We also assessed the effects of GBR 12909, a selective DAT inhibitor, but found no effect of any dose on behavior. A second study in adolescent rats investigated changes in norepinephrine transporter (NET) and dopamine beta hydroxylase (DBH) density in five functionally distinct subregions of the prefrontal cortex: infralimbic, prelimbic, anterior cingulate, medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortices. These regions are implicated in impulsivity and distractibility. We found that NET, but not DBH, changed across adolescence in a regionally selective manner. The prelimbic cortex, which is critical to cognitive rigidity, and the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, critical to reversal learning and some forms of response inhibition, showed higher levels of NET at early than mid- to late adolescence.

Keywords: Norepinephrine transporter, Dopamine beta hydroxylase, Prelimbic cortex, Lateral orbitofrontal cortex, Anterior cingulate cortex

1. Introduction

There is an increasing awareness that disruption of the development of prefrontal cortex in adolescence increases vulnerability to a multitude of neuropsychiatric disorders (Casey and Jones, 2010; Andersen, 2008). Moreover the diagnoses of disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) that are made in childhood require pharmacologic treatment for prolonged periods to improve attention and to decrease vulnerability to substance abuse related to impaired impulse control (Mannuzza et al., 2008; Szobot and Bukstein, 2008). Though much of the literature has examined the impact of these drugs on dopaminergic systems (Somkuwar et al., 2013), many of these agents also affect noradrenergic neurotransmission in the prefrontal cortex and this action has been hypothesized to be a major factor underlying the clinical efficacy of these compounds (Berridge et al., 2006, 2012; Devilbiss and Berridge, 2008; Agster et al., 2011). Two commonly prescribed medications for ADHD, atomoxetine and methylphenidate, share a common mechanism of blocking norepinephrine transporters (NET) thus prolonging the availability of extracellular norepinephrine. As NET is a target for drugs used to treat ADHD (Chamberlain et al., 2007; Cabellero and Nahata, 2003), it is imperative that we: 1) differentiate the effects of dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake blockade on executive functions in adolescents and 2) understand how substrates for the actions of these drugs, e.g. NET, change in prefrontal cortical sub-regions across development.

To address these questions, the current study was designed in two parts. The first was to compare the effects of drugs that block NET, DAT or both on the behavior of adolescent rats in an attentional set-shifting paradigm that allows assessment of reversal learning, response inhibition, distractibility, as well as the formation and shifting of an attentional set (Birrell and Brown, 2000; Robbins et al., 1998). These tests model behavior in humans (Owen et al., 1991), and are amenable to use in non-human primates (Roberts et al., 1992; Roberts and Wallis, 2000) and rodents (Danet et al., 2010; Tait et al., 2007) thus facilitating cross-species translation of findings. Normal subjects show flexible attentional control that allows for focused attention but can also respond when response contingencies have changed (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005; Bouret and Sara, 2005). Cognitive rigidity is the inability of subjects to disengage from focused attention to learn new response contingencies (McGaughy et al., 2008; Newman et al., 2008; Newman and McGaughy, 2011a) whereas distractibility results when subjects cannot adequately focus attentional scope. Prior work with adolescent rats revealed immaturities in cognitive control when compared to adults (Newman and McGaughy, 2011b). These data support the hypothesis that maturation of different aspects of cognitive control occur independent of one another with the ability to shift an attentional set developing prior to reversal learning (Newman and McGaughy, 2011b). The administration of atomoxetine improves the former, but not the latter function when given to adolescent rats (Cain et al., 2011). Because previous studies have shown a critical role for norepinephrine (NE) in the prelimbic cortex (PL) in attentional set shifting, atomoxetine was administered immediately prior to this test (McGaughy et al., 2008; Newman et al., 2008). However this design cannot provide information about the impact of this drug on attentional set formation and may introduce state-dependent effects between the formation of the attentional set and the set shift. To address this limitation in our prior work, we administered all drugs prior to the formation of the attentional set. In the present study, we compare the effects of atomoxetine to methylphenidate in male, adolescent rats. Though these drugs are often dissociated on the basis of their ability to block norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake (methylphenidate) versus norepinephrine alone (atomoxetine) in forebrain terminal fields, it should be noted that higher doses of atomoxetine increase the levels of dopamine in the rat prefrontal cortex (Bymaster et al., 2002; Tzavara et al., 2007). We also assessed the effects of GBR 12909, a selective blocker of the dopamine transporter (Andersen, 1989) in an additional cohort of rats to determine how increasing dopamine without concomitant increases in norepinephrine would impact executive function in adolescents. Because of their effects on norepinephrine reuptake, we hypothesized that both the low dose of atomoxetine and methylphenidate would decrease cognitive rigidity in young adolescents. Furthermore because response inhibition has been shown to depend upon dopamine (Dalley et al., 2004; Dias et al., 1997), we hypothesized that both methylphenidate and GBR would improve response inhibition as measured in part by tests of reversal learning and the shifting of attentional set. All behavioral tests occurred during early adolescence (<PND 45) to best assess the impact of these medications on stages of development coincident with immaturities in attentional set-shifting as well as reversal learning (Newman and McGaughy, 2011b) and in line with our prior work on the effects of atomoxetine in adolescent rats (Cain et al., 2011).

Prior work in adults has shown that density of norepinephrine varicosities varies across prefrontal subregions with the density of innervation lower in lateral orbitofrontal (LOrb) than medial frontal cortex (Agster et al., 2013). This study provides evidence of a cytoarchitecture capable of providing for differential norepinephrine release as well as differential noradrenergic modulation of circuit function and cognitive operations in prefrontal sub-regions of adult animals. However comparable developmental studies and inferences regarding norepinephrine regulation of executive control in adolescents are lacking. To address this gap in the literature we used unbiased stereology to determine how noradrenergic markers in prefrontal subregions were altered over the course of early, middle and late adolescence. Density of NET and dopamine beta-hydroxylase was measured in PL, infralimbic, anterior cingulate (ACC), medial and lateral orbitofrontal (LOrb) cortices since these regions have specific associations with attentional set-shifting (Birrell and Brown, 2000; Lapiz and Morilak, 2006), impulse control (Stopper et al., 2014; Robinson et al., 2007; Bari and Robbins, 2013), and distractibility (Newman et al., 2014). Because the cognitive rigidity found in adolescents is similar to that found in adults after selective noradrenergic deafferentation of the PL (Newman et al., 2008) and the administration of a selective noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) to adolescent rats remediates this rigidity (Cain et al., 2011), we hypothesized that densities of norepinephrine transporters in prefrontal cortex would be highest in early adolescence but decline in later adolescence and that this decline would be paralleled by changes in DBH. Additionally, we hypothesized that there would be regional differences in these changes in line with prior behavioral work showing that aspects of cognitive control reliant on LOrb cortices mature later than those that rely upon the functional integrity of the PL.

2. Results

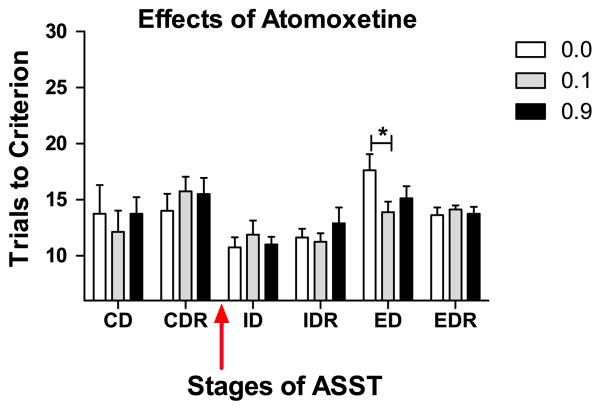

2.1. Effects of atomoxetine, a selective NET inhibitor

All subjects given atomoxetine formed an attentional set and so required more trials to reach criterion performance on the ED than ID (Test: F(1,7)=115.42, ID vs. ED at 0.0 mg/kg/ml: t (7)=7.07, both p<0.05; Fig. 1). The administration of atomoxetine prior to the ID replicated data gathered when atomoxetine was given immediately prior to the EDS (Cain et al., 2011). Performance on the ED was improved in a dose dependent manner (Dose × Test: F(2,14)=6.66; p<0.05). When performance at the 0.0 mg/kg/ml dose was compared to the low and high doses of drug, the 0.1 (t (7)=2.45; p<0.05) but not the 0.9 dose (t(7)=1.89; p>0.05) improved attentional set-shifting. As we have observed previously, the administration of atomoxetine had no effect on reversal learning (all p>0.05).

Fig. 1.

Stages of the ASST repeated over testing days are shown on the abscissa here and in Figs. 2–4: CD: compound discrimination, CDR: reversal of compound discrimination, ID: intra-dimensional shift, IDR: reversal, ED: extra-dimensional shift, EDR: reversal. Similarly, the red arrow here and in Figs. 2–4 indicates the timing of drug administration prior to the ID. All rats (PND 41–43) showed normal performance after vehicle injection (white bars) and required more trials to reach criterion performance (ordinate) on the ED than on the ID. As indicated by the asterisk the 0.1 (gray bars), but not a 0.9 (black bars) mg/kg/ml, dose of atomoxetine improved performance on the ED selective to vehicle. There was no effect on any other stage of the ASST. The effective dose was highly selective for increasing cortical norepinephrine while the higher dose causes concomitant increases in cortical dopamine and acetylcholine.

All tests prior to the ID were performed in a drug-free state but these data were analyzed to determine if any differences existed in performance prior to drug-dosing across the testing days. Subjects showed no modality based difference in exemplars (all p>0.05). There was no difference in the CDs or CDRs across the different days of testing for the atomoxetine rats (all p>0.05).

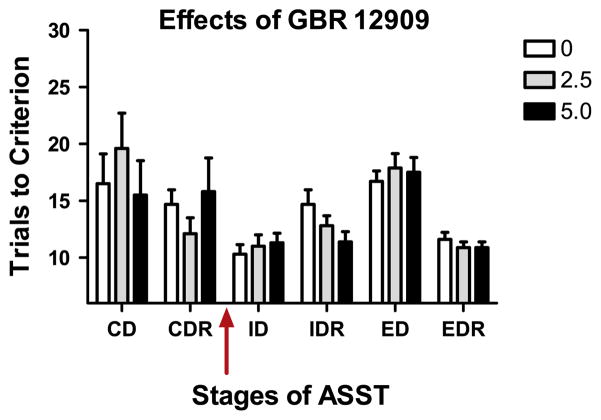

2.2. Effects of GBR 12909, a selective DAT inhibitor

All subjects in the GBR cohort formed an attentional set and showed a cost of shifting this set (Test: F(1,9)=121.14, ID vs. ED at 0.0 mg/kg/ml: t(9)=6.53, both p<0.05; Fig. 2). There were no effects of GBR 12909 on formation (ID) or shifting of attentional set (ED, Drug: F(2,18)=0.44; p>0.05; Drug × Test: F(2,30)=0.11; p>0.05). There was no effect of GBR on reversals that occurred after drug administration, i.e. IDR or EDR (all p>0.05). There was no difference in discriminability of stimulus based on modality as acquisition of all exemplar stages were similar (p>0.05). No changes were found across repeated tests of CD or CDRs in the rats assigned to receive GBR 12909 prior to the ID (all p>0.05).

Fig. 2.

Similar to the performance of young adolescent rats tested with atomoxetine shown in Fig. 1, rats tested with GBR 12909, a selective blocker of the dopamine transporter, required more trials to reach criterion on the ED than the ID demonstrating the cost of shifting attentional set. There were no effects of either dose of this drug on any stage of testing.

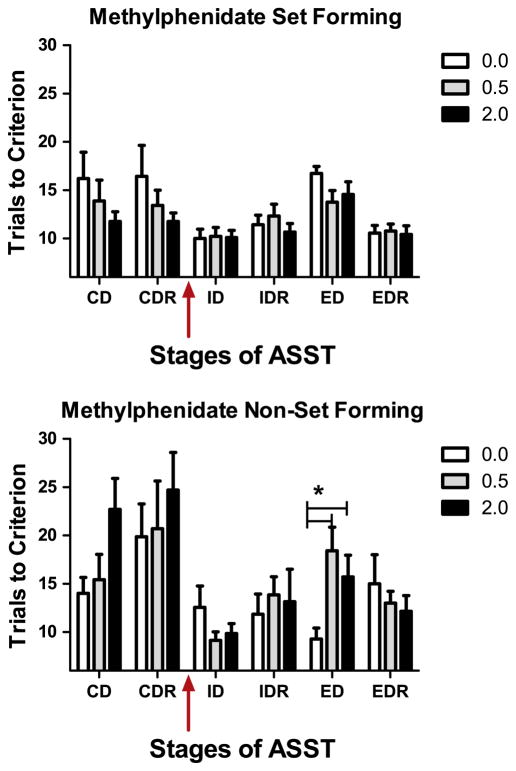

2.3. Effects of methylphenidate, a NET and DAT inhibitor

The initial assessment of the effects of methylphenidate on formation and shifting of attentional set failed to show any effects of drug on performance (Drug: F(2,30)=0.086; p>0.05; Drug × Test: F(2,30)=1.43; p>0.05; Fig. 3). There was a main effect of test (F(2,30)=32.22, p<0.05) with the average number of trials required to reach criterion on ED greater than that on the ID when collapsed across all doses of drug. In contrast to the other two cohorts, there was no difference at baseline when the number of trials required to reach criterion performance on the ID was compared to the ED (t(15)=1.48; p>0.05). This cohort unlike the other two had a clear subgroup of rats that did not show a cost of shifting attentional set as discussed below. The administration of methylphenidate did not alter reversal learning (all p>0.05). Performance on exemplar training was similar regardless of testing modality (p>0.05). Similar to results found in rats given atomoxetine, there was no difference in the CDs or CDRs across the different days of testing for the rats assigned to the methylphenidate group (all p>0.05).

Fig. 3.

Overall the mean performance on the ID was better than the ED after vehicle injection to this group of rats but methylphenidate did not impact performance at any stage of testing. In contrast, to the two other cohorts, mean performance reflected the average of two distinct subgroups. One group showed a cost of attentional set-shifting (n=9), i.e. required more trials to reach criterion performance on the ED than ID, while another group did not (n=7). We present data from these two cohorts separately in Fig. 4.

2.3.1. Analyses based on attentional set formation

Because many of the rats assigned to the methylphenidate group failed to form an attentional set, we were afforded an opportunity to determine the effects of the drug on subjects who formed an attentional set and those that did not form an attentional set. Subjects who required an equal or lesser number of trials to reach criterion on the ED than the ID were classified as non-set formers, n=7. Rats that required more trials to reach criterion on ED than ID were classified as set-formers, n=9. The performance on the ID and ED of rats who formed an attentional set was unaffected by the administration of methylphenidate (Dose: F(2,16)=0.86, Dose × Test: F(2,16)=1.6, both p>0.05; Fig. 4, top panel). In contrast, the administration of the methylphenidate to rats who failed to form an attentional set after vehicle injection, showed a cost of attentional set-shifting after the administration of either dose of the drug (F(2,12)=8.47; p<0.05; Fig. 4, bottom panel). In non-set forming subjects, the administration of the drug did not impact performance on the ID (all p>0.05), but both doses of the drug increased the number of trials to reach criterion performance on the ED when compared to vehicle (0.0 vs. 0.5 mg/kg/ml t(6)=3.47; 0.0 vs. 2.0 mg/kg/ml t(6)=2.91, both p<0.05). There was no effect of methylphenidate on reversal learning in either set-forming or non-set forming subjects (all p>0.05). A re-analyses of pre-drug data was done to compare the acquisition of CD and CDR on all days prior to drug injection of animals who showed an attentional set-shifting cost to those that did not. Though performance did not differ on any one stage or any one day (all p>0.05), the animals who failed to show an attentional set-shifting cost required more trials than set-forming subjects when performance on all CDs and CDRs was combined (F(1,14)=14.19; p<0.05). As these stages of testing all involved complex stimuli, we also compared set-forming to non-setting forming subjects performance on all testing involving simple, conditional discriminations (exemplars and SD) and found no differences between the groups (p>0.05).

Fig. 4.

Rats that formed an attentional set, required fewer trials to reach criterion performance on the CD and CDR, which was drug-free for all subjects, than rats who did not show a cost of shifting attentional set. Because these discriminations all involve complex stimuli containing an irrelevant stimulus dimension, we hypothesized that performance resulted from a greater degree of distractibility in non-set forming subjects. We compared performance of these two groups on all discriminations involving stimuli that differed on only one dimension (exemplars and SD) and found no difference between the groups (exemplar data not shown). The graphs below show that methylphenidate had no effect on rats able to form an attentional set (top panel), but induces a set-shifting cost in distractible animals thus normalizing performance.

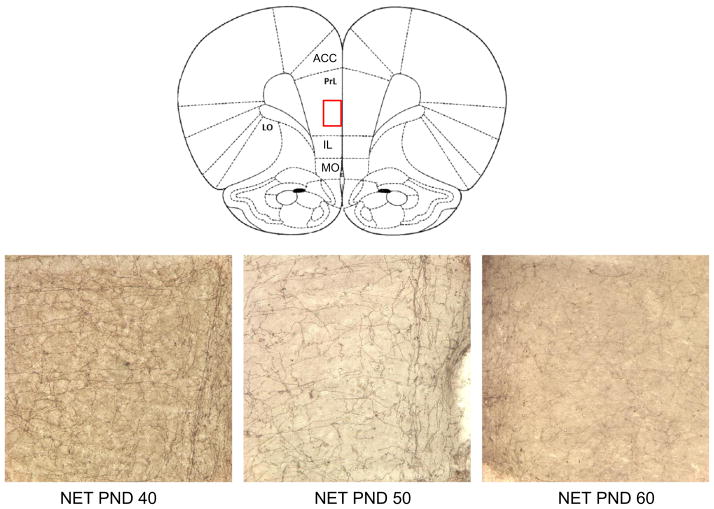

2.4. Norepinephrine transporter density

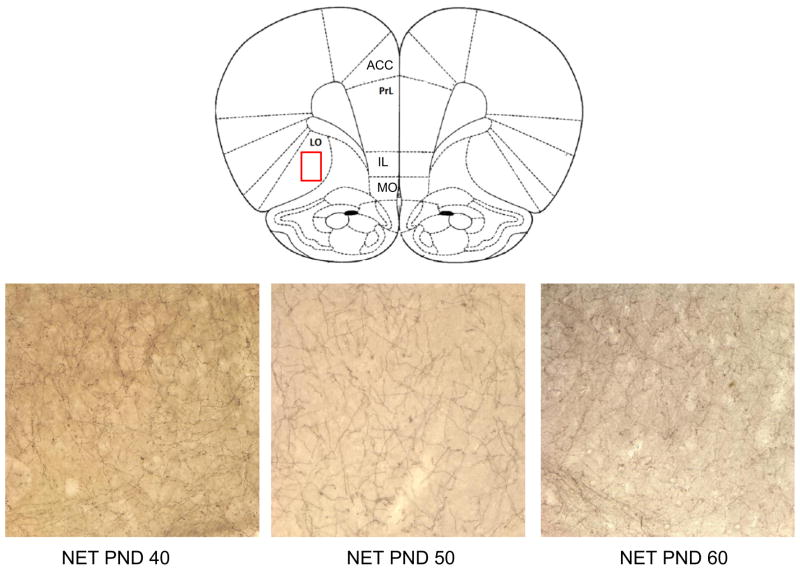

Density of NET-stained varicosities in the PrL and lORB (Figs. 5 and 6) decreased between post-natal days 40–60 (PrL, F(2,15)=3.80; p<0.05; lORB, F(2,15)=5.55; p<0.05; Fig. 7, top panel). Planned comparisons showed that NET density in PrL was lower at PND 60 than at either PND 50 (t(10)=2.47; p<0.05) or PND 40 (t(10)=2.37; p<0.05) but there was no difference when PND 40 was compared to PND 50 (t(10)=1.14; p>0.05). In the lORB, NET density was higher at PND 40 than PND 50 (t(10)=2.42; p<0.05) and PND 60 (t(10)=2.74; p<0.05) but no difference was found between PND 50 and 60 (t(10) = 0.53; p>0.05; Fig. 7 top panel). No other sub-region showed significant changes in NET density across adolescence.

Fig. 5.

A representative section showing a schematic diagram of all five prefrontal subregions sampled, ACC: anterior cingulate, IL: infralimbic, lORB: lateral orbitofrontal, mORB: medial orbitofrontal, PL: prelimbic cortices. Photomicrographs of NET staining for representative subjects at each age, post-natal day (PND) 40, PND 50 and PND 60 showing a magnification (400 ×) of the PL cortex region highlighted in red in the schematic diagram.

Fig. 6.

Photomicrographs of NET staining for representative subjects at each age, post-natal day (PND) 40, PND 50 and PND 60 showing a magnification (400 ×) of the LOrb region highlighted in red in the schematic diagram.

Fig. 7.

The top panel shows the NET staining across all ages for all sub-regions sampled. ACC: anterior cingulate, IL: infralimbic, lORB: lateral orbitofrontal, mORB: medial orbitofrontal, PL: prelimbic cortices. Changes in NET density were regionally specific. Asterisks indicate NET density in PL was higher at PND 40 than 60 and also higher at PND 50 than 60. Density in lORB declined between PND 40 and 50 but showed no greater decline at PND 60. There were no other significant changes in NET density in the other prefrontal regions sampled. The bottom panel shows DBH stained varicosities in the same regions. There were no statistically significant difference in DBH stained varicosities at the three ages and five subregions sampled.

2.5. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase density

One-way ANOVAs showed that the density of dopamine beta-hydroxylase was unchanged in all prefrontal sub-regions sampled as shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 7.

3. Discussion

3.1. Summary of results

The current study replicates previous work showing that atomoxetine improves cognitive flexibility in adolescent rats (Cain et al., 2011; Harvey et al., 2013), and extends this work by showing methylphenidate does not produce the same effects. Here we explicitly test the effects of atomoxetine on the formation of the attentional set by administering the drug prior to the ID. Prior studies have assessed the effects of the drug administered immediately prior to the test of the ED so the effect of this drug on the formation of the attentional set remained unresolved. The present design better addresses concerns that changes at the ED may have resulted from state-dependent memory as the administration of drug immediately prior to the ED may impair recall of an attentional set learned in a drug free set, i.e. during the ID. The replication of a selective effect on the ED when subjects were tested in the same drug state during formation of the attentional set and the set shift supports the hypothesis that this effect is not an artifact of state dependent memory, but an improvement in cognitive flexibility specific to attentional set shifting. Previous research has shown that damage to the PL impairs this form of cognitive flexibility (Birrell and Brown, 2000; Ng et al., 2007; Dias et al., 1996a; McAlonan and Brown, 2003) and selective noradrenergic deafferentation of the region is sufficient to produce these impairments (Tait et al., 2007). As before (Newman et al., 2008; Cain et al., 2011), we found the most effective dose of atomoxetine was that which selectively increased prefrontal norepinephrine (0.1 mg/kg/ml) without concomitant changes in other neuromodulators (Tzavara et al., 2007). Though these data support the hypothesis that prefrontal norepinephrine produces an inverted-U dose response curve in this task (Newman et al., 2008; Cain et al., 2011), this conclusion would be strengthened by an expansion of the dose range and age of subjects tested. In the present study, drugs that increase prefrontal dopamine either preferentially or in concert with norepinephrine, i.e. GBR or methylphenidate, did not improve attentional set shifting. This contrasts with prior work from Floresco and others who show a curvilinear dose response curve for D1 and D2 like receptors in two alternate versions of the set-shifting task. This may result from developmental differences in the density of these receptors in the prefrontal cortex receptors during early adolescence and remains an area that requires further study (Andersen et al., 2000). Together the data suggest remediation of cognitive rigidity is best achieved by doses of drugs that selectively increase cortical norepinephrine. Higher doses of atomoxetine, beyond those that produce selective increases in norepinephrine, improve other forms of impulsivity in adult rats as assessed by a stop-signal (Robinson et al., 2007; Bari et al., 2009), rat gambling (Baarendse et al., 2013), or a serial reaction time task (Robinson et al., 2007; Bari et al., 2009). It is unclear whether the lack of effects on other aspects of the ASST is age-related or whether the benefits to impulsivity reflect changes in other neuromodulators, e.g. dopamine produced by these doses.

Stereological analyses revealed region specific changes in NET density with both prelimbic and lateral orbitofrontal cortices showing steep declines from early to later adolescence. Somewhat surprisingly we found discrepancies between noradrenergic markers. NET but not DBH showed marked declines across the ages sampled. The basis of this discrepancy is unknown but suggests that developmental trajectories of DBH and NET are independent. We hypothesize that the higher density of NET concurrent with stable level of DBH results in a functional deficit of norepinephrine that is remediated by NET blockade but unchanged by DAT blockade. We will discuss the implications of these findings together with the pharmacological findings.

3.2. Effects of methylphenidate are baseline dependent

In contrast to the effects of atomoxetine, methylphenidate’s effects depended upon the baseline attentional ability of the subject in line with other studies (Harvey et al., 2011). Kantak and colleagues found similar results in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) that were given chronic methylphenidate from PND 28–55. SHR rats show more difficulty in acquiring a visual discrimination than Wistar-Kyoto or Wistar rats when tested as young adolescents. Methylphenidate improved performance of adolescent SHR rats but was without effect on the other two strains of rat (Harvey et al., 2011). In the present study the methylphenidate cohort showed two distinct sub-populations. The first formed an attentional set and showed the typical cost of set-shifting. In contrast, the second showed no cost of shifting attentional set. As shown in Fig. 4, the subjects that responded to methylphenidate performed differently prior to drug administration on discriminations involving complex stimuli (i.e. CD, CDR). These sub-groups did not differ on their ability to discriminate when pairs of stimuli differed on only one dimension (exemplars, SD). These data suggest that some adolescent rats were more distractible and had difficulty performing discriminations with complex stimuli which contained irrelevant stimulus dimensions. Our prior work has shown that this form of distractibility in the ASST relies on the function of the ACC and results from the irrelevant dimension’s prior association with reinforcement rather than a general susceptibility to distraction (Newman and McGaughy, 2011a). As a result, we hypothesize that the beneficial effect of methylphenidate in the current study may depend upon the ACC, but the present study did not directly test this hypothesis. Interestingly, this form of distractibility to salient features of stimuli has been shown in humans to rely on similar circuits and may be critical to processing of drug-associated cues (Bush et al., 2003; Janes et al., 2015, 2009). The present version of the set-shifting task retains a third, salient dimension that must be disregarded throughout testing. This may increase this form of distractibility in all stages of the task with complex stimuli, i.e. CD-EDR. The current findings with methylphenidate are in line with prior data from Arnsten showing that increasing prefrontal dopamine levels can decrease distractibility (Arnsten and Rubia, 2012; Arnsten and Li, 2005). Unfortunately, neither of the other two cohorts tested had a sub-group of highly distractible rats that failed to form an attentional set leaving unresolved in the current work whether the improvement in disregarding salient stimuli results from DAT or NET blockade.

3.3. The effects of GBR 12909

The absence of any effect of GBR 12909 on behavior is somewhat unexpected. One plausible explanation for this negative finding may be related to a floor effect on the critical tests (IDR, EDR). This may also be true for the absence of any drug effect on reversal learning. This type of learning has previously been shown to depend on the functional integrity of the orbitofrontal cortex (McAlonan and Brown, 2003; Dias et al., 1996b). As subjects typically require more trials to reach criterion performance on the first test of reversal learning (CDR) than subsequent reversals, it would be useful to assess the effects of all drugs on this stage of testing. The lack of effect of GBR may also be a result of the dose range tested. These doses were selected based on prior work in rats showing they impacted attention (Seu et al., 2008) and impulsivity (Fernando et al., 2012), but these tests were conducted in adult rats. Another possibility is the absence of appropriate DAT targets in the adolescent brain. Little is known about how the density of DAT changes in the prefrontal cortex over adolescence. Some reports have demonstrated that DAT levels are undetectable in frontal cortex at this age (Moll et al., 2000) so that the absence of effect may reflect the unavailability of the critical substrate upon which DAT blockers act. Future studies should be aimed at both the quantification of DAT in prefrontal sub-regions across the lifespan including adolescents and testing the effects of higher doses of GBR during adolescence.

3.4. Implications of stereological findings

The stereological analyses of the prefrontal sub-regions studied revealed several novel insights. First, changes in NET were regionally specific with differences found in lORB and PL but none of the other sub-regions sampled. Recent work in adults has shown that neurons originating in the locus coeruleus provide circumscribed innervation of prefrontal sub-regions with few neurons innervating multiple sub-regions (Chandler et al., 2013). The present data support the hypothesis that development may also occur in a regionally specific manner. The stereological data in conjunction with previous data from our laboratories supports the hypothesis that differences in cognitive flexibility between adolescents and adults results from changes in NET density in PL and LOrb cortices. We have shown that adolescent rats are more susceptible to distraction when tested with complex stimuli containing irrelevant stimulus dimensions. However, once adolescent rats disregard this irrelevant dimension, they become more cognitively rigid than adults and have difficulty shifting attentional set (Newman and McGaughy, 2011b). Because set-shifting has been consistently linked to noradrenergic function in the PL cortex (McGaughy et al., 2008; Newman et al., 2008), we hypothesize that the systemic administration of a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor to adolescent rats compensates for the high levels of NET in PL and thus optimizes NE in this region. In contrast, reversal learning which has been linked to the functional integrity of the LOrb cortex was unchanged in adolescent rats following all drug treatments. This lack of improvement is likely to reflect the greater involvement of dopamine and serotonin in reversal learning than norepinephrine (Dalley et al., 2004; Zeeb et al., 2010; Cardinal et al., 2004) but may also reflect neuroanatomical organization of this sub-region where noradrenergic varicosities are less dense than in medial frontal cortex; thus noradrenergic modulation of this region may require higher drug doses than those tested here (Chandler et al., 2013). Interestingly, the SHR rat which is commonly used as a model of ADHD has been shown to have higher rates of NE clearance in the region of the lORB, but not in medial prefrontal subregions including PL, IL and ACC (Somkuwar et al., 2015). Further evidence of the functional independence of the noradrenergic innervation of these prefrontal sub-regions come from Vanderschuren and colleagues who have shown that social play behavior in juvenile rats (PND 33–36) is reliant on NE in IL and ACC, but injection of methylphenidate or atomoxetine in PL or lORB has no impact on these behaviors (Achterberg et al., 2015). Taken together with the current work, these data suggest that development of social behavior is sub-served by distinct prefrontal sub-regions than those that mediate cognitive flexibility though all are dependent upon norepinephrine. A critical expansion of the current work would be to assess markers of norepinephrine at both younger and older ages.

We predicted that changes in NET would mirror changes in DBH, but these markers changed in distinctive ways across adolescence. The current study cannot resolve whether this differential trajectory is a unique feature of prefrontal cortices or is also present in other noradrenergic terminal fields. Others have reported similar disconnections in tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and DAT in ACC but found substantial overlap between these two markers in other regions such as the ventral tegmental area (Ciliax et al., 1995). The discrepancy between TH and DAT may be in part explained by fact that TH marks more than dopaminergic neurons, but it is also possible that these markers are indicative of either distinct sub-populations of dopaminergic neurons (Ciliax et al., 1995). As the varicosities of norepinephrine neurons represent the functional elements of the axons of these cells (Descarries et al., 1977; Chiti and Teschemacher, 2007), it is important to understand whether DBH levels are influenced by NET changes or vice versa across development. Though the data shown in Fig. 8 suggest that DBH decreases at PND 50, there were no statistically significant changes in this marker across adolescence. It may be argued that the study had too few subjects to detect differences, but these were the same subjects used to assess NET and the n was comparable to other stereological studies of prefrontal cortex. Because DBH is relatively static at the ages sampled, the high levels of NET at PND 40 are hypothesized to result in rapid reuptake of norepinephrine from the extracellular space and thus a functional deficit of norepinephrine action in PFC at this age. This functional deficit is hypothesized to produce cognitive rigidity which can be remediated by blockade of NET as shown in the current study and others (Cain et al., 2011; Harvey et al., 2013). A less likely possibility is that the high density of NET leads to increased extracellular levels of NE and prefrontal hypodopaminergia as found in rictor null knockout mice. This supra-optimal level of NE was hypothesized to result from the pre-synaptic conversion of dopamine to norepinephrine (Siuta et al., 2010) after both are moved by NET in noradrenergic neurons. This type of imbalance would also likely require concomitant changes in DBH density which was not observed in the present study. Moreover, drugs and doses of atomoxetine that increased frontal dopamine were ineffective at improving cognitive rigidity as previously discussed while doses of atomoxetine the selectively increased NE were effective. This supports the hypothesis that cognitive rigidity in adolescence most likely results from functional deficits in norepinephrine rather than supra-optimal levels of NE.

Fig. 8.

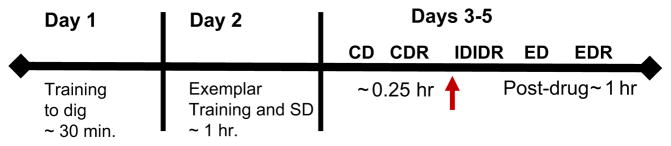

The experimental timeline is provided for all behavioral testing days. On post-natal day (PND 39), all subjects were trained by successive approximation to dig for a reinforcer in a stimulus pot. The next day, PND 40, rats were trained in three simple, conditional discriminations so each subject learned that one of three exemplars, odor, digging media or texture could predict reinforcement. The final discrimination was the first stage of the set-shifting task, the simple discrimination (SD) which trained the rat which of the three modalities would be reinforced for this and the next four stages of training. For three consecutive days, rats were then tested on the subsequent stages of the attentional set-shifting task (ASST) CD: compound discrimination, CDR: reversal of compound discrimination, ID: intra-dimensional shift, IDR: reversal, ED: extra-dimensional shift, EDR: reversal. A detailed description of each stage is provided in the methods sections.

The present data support our general hypothesis that noradrenergic innervation of the prefrontal sub-regions develop at different rates, but it remains unresolved whether these difference in maturation are also reflected in the locus coeruleus, the origin of these pathways or the expression of adrenergic receptors in this same developmental window. Though work in humans and rodents have consistently shown benefits to attention of acute dosing of atomoxetine and methylphenidate (Devilbiss and Berridge, 2008; Chamberlain et al., 2007; Newman et al., 2008; Cain et al., 2011; Robinson et al., 2007; Seu et al., 2008), an additional critical issue for future studies is to understand how chronic drug treatment during adolescence influences these developmental changes in NET and if these changes persist into adulthood. The current data provide new information about structural changes in the prefrontal cortex across adolescence that have functional consequences on both on the ontogeny of cognitive control, and the response of the adolescent brain to pharamacotherapies aimed at treating ADHD. Our data support the hypothesis that atomoxetine at noradrenergically selective doses may be best used to reduce cognitive rigidity. In contrast, methylphenidate may be better suited to improving distractibility especially to stimuli whose salience has been enhanced by prior reinforcement.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Subjects for behavioral pharmacology studies

A total of 34 male rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used in the behavioral studies. Rats arrived to the vivarium at the University of New Hampshire on exactly PND 34. They were handled daily and began food restriction 2 days prior to training. Rats were singly-housed and fed approximately 16 g of standard chow/day in addition to reinforcers received during testing. Housing was maintained on a standard 12:12 light/dark cycle (lights on 07:00 a.m.). Rats were checked for preputial separation daily and weighed weekly as a measure of overall health. Behavioral training occurred between 9 a.m. and 1 p.m. beginning on PND 39 and was completed by PND 43. All procedures described in this paper were approved by the University of New Hampshire Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and comply with all relevant federal regulations regarding the care and use of vertebrate animals.

4.2. Apparatus and materials

All training and testing was performed in a plastic testing box (57.0 × 44.5 × 30.0 cm3; L × W × H, Quantum Storage, Elk Grove, IL) and occurred over 5 consecutive days. Stimuli were terra cotta pots with a height of 7 cm and an internal diameter of 7.0 cm and affixed to the floor of the testing box with Velcro (Manchester, NH). Test stimuli were placed in either end of the testing box with access to these sections prevented by a divider while stimuli were placed. Reinforcement for both training and testing was a 20 mg food pellet (Dustless Precision Pellets, Bioserv, Frenchtown, NJ). For all trials with two stimuli, a crushed amount of reinforcer equal to 20 mg was put in the incorrect pot to prevent subjects from using olfactory cues related to reward to solve discriminations.

4.2.1. Training – Day 1 – PND 39

A timeline of the experimental protocol is provided in Fig. 8. Each rat was shaped to dig for a food reward in a flower pot filled with pine shavings. The limited hold for each trial was 90 s. For the first three trials, the reinforcer was atop the bedding. The rat was then given 5 trials with the reinforcer partially buried. After this, the rat was required to retrieve 10 fully buried reinforcers. Upon successful completion of these fully buried trials, the rats were considered eligible to begin testing.

4.2.2. Exemplar training – Day 2 – PND 40

Three pairs of exemplar pots were tested in a series of conditional discriminations. Subjects were trained to discriminate between the pair of stimulus pots based on one of three attributes: texture, odor or digging media. Pots were either wrapped in fabric to give each a different texture (fuzzy vs. smooth fur), filled with different digging media (white vs. green paper), or scented with different odors (cherry vs. pine). Texture discriminations were always made between a pot with the fabric right side out and one with the fabric reverse side out. This ensured that rats attended to texture and could not use odor cues associated with two distinct textures. Similarly, digging media differed in brightness but were made of the same material, e.g. paper or foam, to minimize the use of odor cues on these discriminations. The pots were filled with unscented manilla folder during the odor and texture discrimination to cover the reinforcer. These exemplars were not used again.

Each trial started with the pair of pots was placed in the box behind a divider with the rat on the other side of the divider. This allowed the experimenter to control access to test stimuli. The trial began when the experimenter removed the divider and started the timer. After the rat successfully retrieved the reinforcer, the divider was placed in the opposite end of the box and the pots for the next trial were placed behind the divider. On subsequent trials, the position of the reinforced stimulus was varied, i.e. left or right side in a pseudorandom fashion to prevent the development of a side bias. Response latency was the amount of time elapsed between the removal of the divider and displacement of the digging medium with either the nose or forepaw. The first four trials of each discrimination were discovery trials. These trials differed from subsequent trials in two ways. First, the limited hold was longer (90 s) on these trials than on non-discovery trials (60 s). Secondly, if the rat made an incorrect response during a discovery trial he was allowed to explore the correct pot and retrieve the reinforcer. When rats responded, accuracy and latency were recorded. Trials where the limited hold expired without any response were marked as omissions but not incorrect. Criterion performance for all stages was seven correct, consecutive responses. Once the rat achieved criterion performance on non-discovery trials for all exemplars, he began testing in the attentional set shifting task (ASST). The order of testing pairs was varied across subjects so the modality of the last exemplar was the same as the subsequent simple discrimination (SD). The first discrimination in the ASST is the simple discrimination (SD) where the pots differ on only one dimension (texture, digging medium, or odor) as in the prior exemplar tests. As before, the rat was given four discovery trials in which they were permitted to dig in both pots, and again one pot was baited (i.e. patchouli scented pot) while the other contained an equal amount of crushed reinforcer. Once the animal achieved criterion performance on the SD, testing ended for the day.

4.2.3. Attentional set shifting stages with complex stimuli –Days 3–5, PND 41–43

Testing began with the compound discrimination (CD). For all testing pots beyond the simple discrimination, the outer surfaces of the pots were covered with textures and the inside of the pots were filled with digging media which were scented using diluted aromatherapy oils (essential oils diluted 1:100 in canola oil) so this and all subsequent discriminations were between two complex stimuli. The rat was still rewarded for attending to the previously reinforced dimension, odor (e.g. patchouli). In order to minimize the number of pairs of pots needed, the dimension that was irrelevant to both the first ID and ED was held constant across all pots. For example, rats trained to attend to odor in tests of the SD→intradimensional reversal (IDR) that shifted responding to digging media in the ED→extradimensional reversal (EDR) received two pairs of pots with identical texture cues. Any deficits seen at the CD would suggest deficits in ignoring novel, irrelevant stimuli.

After reaching criterion performance on the CD, the reinforcement contingencies within a modality were reversed (i.e. cinnamon scented pot was rewarded, CDR). After seven consecutive, correct responses, a new set of stimuli (new odors, digging media, textures) was introduced using a total changeover design. For the next discrimination, the intradimensional shift (ID), the animal was reinforced for maintaining attentional focus to the same dimension as the previous discrimination in this example odor, e.g. lilac scented pot. Learning at this stage should be facilitated by the animal maintaining attentional focus on the previously rewarded stimulus dimension; so rats able to focus attention typically require fewer trials to achieve criterion here than on the CD. After achieving criterion performance on ID, another reinforcement reversal was performed (IDR; reinforced for digging in rose scented pot). This test was followed by the introduction of a second novel set of stimuli to test the extradimensional shift (ED). At this stage, the animal is reinforced for attending to a previously unattended but variable dimension, i.e. shifting attentional set (digging medium; metallic beads). If the animal has formed an attentional set then he should take significantly more trials to achieve criterion performance on the ED than on the ID. After successful completion of the ED, the final reversal (EDR; plastic beads) of the session was given. In order to determine how attentional abilities changes over the course of adolescence, the ID/ED shift and reversals were repeated for two more days (PND 42 and 43). These test days were abbreviated by eliminating the SD to minimize satiety and fatigue.

4.3. Drug dosing

There were three cohorts of rats tested with separate drugs. Within each cohort, a within-subjects design was used so each subject received three doses of drug. The first group received (n=8) 0.0, 0.1 or 0.9 mg/kg/ml of atomoxetine. The second (n=10) received 0.0, 2.5 and 5.0 mg/kg/ml of GBR 12909. The third (n=16) received methylphenidate at 0.0, 0.5 and 2.0 mg/kg/ml. The order of presentation of the dimensions throughout testing was counterbalanced across subjects and drug doses were randomly assigned to a day. Drug administration occurred 30 min prior to the ID.

4.4. Experiment 2. Changes in noradrenergic markers across adolescence

A separate experiment was conducted to determine how markers of cortical noradrenergic systems were changed over early, mid and late adolescence. We examined five prefrontal sub-regions, the prelimbic, infralimbic, anterior cingulate cortex, lateral and medial orbitofrontal cortices.

Eighteen male rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were used in the immunohistochemical studies. Rats were 34, 44 or 54 days (n=6/age) upon arrival in the vivarium at the University of New Hampshire. Rats were free-fed, singly-housed and briefly handled each day prior to euthanasia.

4.5. Euthanasia procedures

Rats were sacrificed on post-natal days (PND) 40, 50, or 60 corresponding to early, middle and late adolescence. After receiving an overdose of euthasol (390 mg/ml Sodium Pentobarbital, 50 mg/ml Phenytoin Sodium, 0.5 ml/kg, Virbac, Fort Worth, TX), rats were exsanguinated with 0.9% saline (35 ml/min) for 5 min. Tissue was then fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 5–7 min (35 mL/min). Brains were post-fixed for 1 h and then placed in a 30% sucrose solution until they sank. Forty μm sections were sliced at 20 °C and then alternately stained for dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH), norepinephrine transporters (NET), or nissl bodies. Every fifth section was saved as part of a set representative of the prefrontal cortices.

4.5.1. Norepinephrine transporter immunohistochemistry

Staining for NET began with a 30 min rinse in a 1% sodium borohydride solution. This was followed by a 30 min bath in a blocking serum of 3% normal goat serum, 1% bovine serum albumin in 1% triton TBS. Without rinsing, tissue was transferred to the primary antibody mouse anti-NET (1:2000 NET in blocking solution; Mab Technologies, Stone Mountain, GA) and remained overnight. Tissue was then rinsed in TBS (3 × 10 min) and placed in the secondary antibody (biotinylated horse anti-mouse, rat adsorbed IgG; 1:400 in blocking solution, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). After TBS rinses, sections were incubated in ABC solution (1:1000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min, rinsed in TBS, and exposed to a 0.022% 3,3 diaminobenzidine/0.0003% hydrogen peroxide solution until fibers were clearly visible (2–30 min). Tissue was mounted on gelatin coated slides. The sections were then dehydrated with a series of ethanol baths, and cover slipped.

4.5.2. Dopamine beta-hydroxylase immunohistochemistry

Tissue was bathed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 30% hydrogen peroxide. After PBS rinses (3 × 10 min), sections were incubated for 2 h in 1% triton PBS followed by overnight incubation in the primary antibody, monoclonal mouse anti-DβH (1:1000). Sections were then rinsed in 0.3% triton PBS and incubated in the secondary antibody, biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (1:1000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 2 h. The tissue was again washed in 0.3% triton PBS and an avidin–biotin reaction was used to visualize the fibers. Sections were incubated in the ABC solution (1:1000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 90 min, rinsed in PBS, and exposed to nickel-enhance 3,3 diaminobenzidine until fibers were clearly visible (2–60 min).

4.6. Stereological methods

Regions of interest were demarcated using Paxinos and Watson (1998), The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. We sampled varicosities throughout the A–P length of each region (Figs. 5 and 6). For determination of cortical fields and sub-fields we relied on coordinates and anatomical landmarks specified in the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos and Watson, 1998; Gundersen and Jensen, 1987), cross-referenced with the atlas of Zilles (1985). The borders of regions of interest were identified after matching tissue sections with comparable atlas sections (Figs. 5 and 6).

Sections were initially viewed at 5 × magnification to contour anatomical boundaries. A Zeiss Axioplan microscope and computer equipped with StereoInvestigator software (version 7; MicroBrightField, Inc., Williston, VT) were used to complete the analysis. A systematic random sample to count varicosities used a grid with spacing of 230 × 180 μm2 that was placed over all regions of interest. Varicosities were counted within a counting frame 10 μm in length, 10 μm in width, and 5 μm in height. A guard zone of 3 μm was employed to avoid irregularities on the tissue surface. The optical fractionator probe was used to estimate the total number of noradrenergic varicosities. Varicosities were counted at 100 × magnification with oil immersion. To estimate regional volume a Cavalieri probe was completed (Gundersen and Jensen, 1987). Grid spacing for the Cavalieri probe was 250 × 250 μm2. The value obtained for the number of varicosities estimated with the optical fractionator was divided by the regional volume to obtain an estimate for the density of noradrenergic varicosities in each region.

4.7. Data analyses behavioral pharmacology

Data from each drug was analyzed in three separate ANOVA’s. The stages of testing that occurred post-injection were segregated from those stages (ID, IDR, ED and EDR) occurring prior to injection (SD, CD, CDR). A critical comparison to determine if subjects have formed an attentional set is the comparison of the ID to the ED, these stages were compared in a repeated measures ANOVA of Test (2) × Dose (3) for each drug. Performance on the ID was compared to the ED after the saline injection for each group using a planned t-test to confirm all subjects demonstrated a cost of shifting attentional set under baseline conditions. A similar series of analyses were run for the post-injection reversals (IDR, EDR). Pre-drug testing was analyzed in two separate repeated-measures ANOVA’s: one for exemplars and SD, test (4, digging media, odor, texture, SD) and one for the first two stages of the ASST/day, test (2; CD, CDR) × day (3).

4.8. Stereological data analyses

A series of one-way ANOVAs were used to compare changes across 3 stages of adolescence (Age, 3) in NET and DBH staining with analyses separated by sub-region. Planned comparisons were used to compare NET density and DBH density in PL and lORB based on prior data showing unique developmental trajectories of attentional set-shifting and reversal learning which rely on these cortical regions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the outstanding technical support of Andrew T. Bates in both the immunohistochemical and behavioral studies. This work was supported by NIH 5R21MH087921 (JM/BDW), 5R01DA017960 (BDW), 5F32MH0-84478 (KLA).

References

- Achterberg EJ, et al. Methylphenidate and atomoxetine inhibit social play behavior through prefrontal and subcortical limbic mechanisms in rats. J Neurosci. 2015;35(1):161–169. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2945-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agster KL, et al. Experimental strategies for investigating psychostimulant drug actions and prefrontal cortical function in ADHD and related attention disorders. Anat Rec. 2011;294(10):1698–1712. doi: 10.1002/ar.21403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agster KL, et al. Evidence for a regional specificity in the density and distribution of noradrenergic varicosities in rat cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:2195–2207. doi: 10.1002/cne.23270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, et al. Dopamine receptor pruning in prefrontal cortex during the periadolescent period in rats. Synapse. 2000;37(2):167–169. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200008)37:2<167::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen PH. The dopamine inhibitor GBR 12909: selectivity and molecular mechanism of action. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;166(3):493–504. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL. Trajectories of brain development: point of vulnerability or window of opportunity? Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;27:3–18. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(03)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AFT, Li BM. Neurobiology of executive functions: catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical functions. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1377–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Rubia K. Neurobiological circuits regulating attention, cognitive control, motivation, and emotion: disruptions in neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(4):356–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baarendse PJ, Winstanley CA, Vanderschuren LJ. Simultaneous blockade of dopamine and noradrenaline reuptake promotes disadvantageous decision making in a rat gambling task. Psychopharmacology. 2013;225(3):719–731. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2857-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, Robbins TW. Inhibition and impulsivity: Behavioral and neural basis of response control. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;108:44–79. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bari A, et al. Dissociable effects of noradrenaline, dopamine, and serotonin uptake blockade on stop task performance in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2009;205(2):273–283. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1537-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, et al. Methylphenidate preferentially increases catecholamine neurotransmission within the prefrontal cortex at low doses that enhance cognitive function. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1111–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, et al. Differential sensitivity to psychostimulants across prefrontal cognitive tasks: differential involvement of noradrenergic alpha(1)- and alpha(2)-receptors. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(5):467–473. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JM, Brown VJ. Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. J Neurosci. 2000;20(11):4320–4324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04320.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouret S, Sara SJ. Network reset: a simplified overarching theory of locus coeruleus noradrenaline function. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28(11):574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush G, et al. The multi-source interference task: validation study with fMRI in individual subjects. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:60–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bymaster FP, et al. Atomoxetine increases extracellular levels of norepinephrine and dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rat: a potential mechanism for efficacy in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;27:699–711. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00346-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabellero J, Nahata MC. Atomoxetine hydrochloride for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Ther. 2003;25:3065–3083. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)90092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain RE, et al. Atomoxetine facilitates attentional set shifting in adolescent rats. Dev Cognit Neurosci. 2011;1:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal RN, et al. Limbic corticostriatal systems and delayed reinforcement. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:33–50. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Jones RM. Neurobiology of the adolescent brain and behavior: implications for substance use disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(12):1189–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.08.017. quiz 1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain SR, et al. Atomoxetine improved response inhibition in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:977–984. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler DJ, Lamperski CS, Waterhouse BD. Identification and distribution of projections from monoaminergic and cholinergic nuclei to functionally differentiated subregions of prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 2013;1522:38–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti Z, Teschemacher AG. Exocytosis of norepinephrine at axon varicosities and neuronal cell bodies in the rat brain. FASEB J. 2007;21(10):2540–2550. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7342com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciliax BJ, et al. The dopamine transporter: immunochemical characterization and localization in brain. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1714–1723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01714.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalley JW, Cardinal RN, Robbins TW. Prefrontal executive functions in rodents: neural and neurochemical substrates. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;28:771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danet M, Lapiz-Bluhm S, Morilak DA. A cognitive deficit induced in rats by chronic intermittent cold stress is reversed by chronic antidepressant treatment. International J Psychopharmacol. 2010;11:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S1461145710000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descarries L, Watkins KC, Lapierre Y. Noradrenergic axon terminals in the cerebral cortex of rat. III Topometric ultrastructural analysis. Brain Res. 1977;133(2):197–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90759-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devilbiss DM, Berridge CW. Cognition-enhancing doses of methylphenidate preferentially increase prefrontal cortex neuronal responsiveness. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Dissociation in prefrontal cortex of affective and attentional shifts. Nature. 1996b;380:69–72. doi: 10.1038/380069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Primate analogue of the Wisconsin card sorting test: effects of excitotoxic lesions of the prefrontal cortex in the marmoset. Behav Neurosci. 1996a;110:872–886. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.5.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias R, Robbins TW, Roberts AC. Dissociable forms of inhibitory control within prefrontal cortex with an analog of the Wisconsin card sort test: restriction to novel situations and independence from “on-line” processing. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9285–9297. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09285.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando AB, et al. Modulation of high impulsivity and attentional performance in rats by selective direct and indirect dopaminergic and noradrenergic receptor agonists. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219(2):341–352. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2408-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology and its prediction. J Microsc. 1987;147:229–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1987.tb02837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RC, et al. Methylphenidate treatment in adolescent rats with an attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder phenotype: cocaine addiction vulnerability and dopamine transporter function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(4):837–847. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RC, et al. Performance on a strategy set shifting task during adolescence in a genetic model of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: methylphenidate vs. atomoxetine treatments. Behav Brain Res. 2013;244:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes AC, et al. Brain fMRI reactivity to smoking-related images before and during extended smoking abstinence. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;17(6):365–373. doi: 10.1037/a0017797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janes AC, et al. Insula-dorsal anterior cingulate cortex coupling is associated with enhanced brain reactivity to smoking cues. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(7):1561–1568. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapiz MD, Morilak DA. Noradrenergic modulation of cognitive function in rat medial prefrontal cortex as measured by attentional set shifting capability. Neuroscience. 2006;137:1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, et al. Age of methylphenidate treatment initiation in children with ADHD and later substance abuse: prospective follow-up into adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:604–609. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07091465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlonan K, Brown VJ. Orbital prefrontal cortex mediates reversal learning and not attentional set-shifting. Behav Brain Res. 2003;146:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaughy J, Ross RS, Eichenbaum HB. Noradrenergic, but not cholinergic, deafferentation of prefrontal cortex impairs attentional set-shifting. Neuroscience. 2008;153(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll GH, et al. Age-associated changes in the densities of presynaptic monoamine transporters in different regions of the rat brain from early juvenile life to late adulthood. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;7:251–257. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman LA, McGaughy J. Attentional effects of lesions to the anterior cingulate cortex: how prior reinforcement influences distractibility. Behav Neurosci. 2011a;125:360–371. doi: 10.1037/a0023250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman LA, McGaughy J. Adolescent rats show cognitive rigidity in a test of attentional set shifting. Dev Psychobiol. 2011b;53:391–401. doi: 10.1002/dev.20537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman LA, Darling J, McGaughy J. Atomoxetine reverses attentional deficits produced by noradrenergic deafferentation of medial prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:39–50. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1097-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman LA, Creer DJ, McGaughy JA. Cognitive control and the anterior cingulate cortex: how conflicting stimuli affect attentional control in the rat. J Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng CW, et al. Double dissociation of attentional resources: prefrontal versus cingulate cortices. J Neurosci. 2007;27(45):12123–12131. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2745-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen AM, et al. Extra-dimensional versus intra-dimensional set-shifting performance following frontal lobe excisions, temporal lobe excisions or amygdalohippocampectomy in man. Neuropsychologia. 1991;29:993–1006. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(91)90063-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson . The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 6. Academic Press; Cambridge, MA: 2008. Compact. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, et al. A study of performance on tests from the CANTAB battery sensitive to frontal lobe dysfunction in a large sample of normal volunteers: implications for theories of executive function and cognitive aging. Cambridge neuropsychological test automated battery. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1998;4:474–490. doi: 10.1017/s1355617798455073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AC, Wallis JD. Inhibitory control and affective processing in the prefrontal cortex: neuropsychological studies in the common marmoset. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:252–262. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AC, et al. A specific form of cognitive rigidity following excitotoxic lesions of the basal forebrain in marmosets. Neuroscience. 1992;47:251–264. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90241-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson ESJ, et al. Similar effects of the selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine on three distinct forms of impulsivity in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;33:1028–1037. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seu E, et al. Inhibition of the norepinephrine transporter improves behavioral flexibility in rats and monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2008;202:505–519. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1250-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuta MA, et al. Dysregulation of the norepinephrine transporter sustains cortical hypodopaminergia and schizophrenia-like behaviors in neuronal rictor null mice. Plos Biol. 2010;8(6):e1000393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somkuwar SS, et al. Adolescence methylphenidate treatment in a rodent model of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: dopamine transporter function and cellular distribution in adulthood. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somkuwar SS, Kantak KM, Dwoskin LP. Effect of methylphenidate treatment during adolescence on norepinephrine transporter function in orbitofrontal cortex in a rat model of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Neurosci Methods. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stopper CM, Green EB, Floresco SB. Selective involvement by the medial orbitofrontal cortex in biasing risky, but not impulsive, choice. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(1):154–162. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szobot CM, Bukstein O. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and substance use disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17:309–323. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait DS, et al. Lesions of the dorsal noradrenergic bundle impair attentional set shifting in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3719–3724. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzavara ET, et al. Procholinergic and memory enhancing properties of the selective norepinephrine uptake inhibitor atomoxetine. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;11:187–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeeb FD, Floresco SD, Winstanley CA. Contributions of the orbitofrontal cortex to impulsive choice: interactions with basal levels of impulsivity, dopamine signalling, and reward-related cues. Psychopharmacology. 2010;211:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1871-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]