Abstract

INTRODUCTION

With survival rates of over 80%, the number of survivors from pediatric cancer continues to increase. Late effects resulting from cancer and cancer therapy are being characterized, but little information exists on sexual health for male survivors of childhood cancer.

AIM

To assess erectile dysfunction (ED) in adult male survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers and to identify potential risk factors for ED.

METHODS

1622 male survivors and 271 eligible siblings in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) cohort completed the Male Health Questionnaire (MHQ), which provided information regarding sexual practices and sexual function. Combined with demographic, cancer, and treatment information from medical record abstraction, the results of the MHQ were analyzed using multivariable modeling. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) was used to identify ED in subjects.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURE

International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)

RESULTS

Survivors (mean age 37.2 years; Standard Deviation (SD) 7.3 years) reported significantly lower sexual activity in the year prior to the survey than siblings (mean age 38.8 years; SD 8.5 years) without cancer. ED was reported by 12.3% (95% Confidence Interval (CI) 10.4%–14.3%) of survivors and 4.2 % (95% CI 2.0%–7.9%) of siblings. Survivors demonstrated significantly higher relative risk (RR) for ED (RR 2.63; 95% CI 1.40–4.97). In addition to older age, survivors who were exposed to higher dose (≥10 Gy) testicular radiation (RR 3.55; 95% CI 1.53–8.24), had surgery on spinal cord/nerves (RR 2.87; 95% CI 1.36–6.05), prostate surgery (RR 6.56; 95% CI 3.84–11.20) or pelvic surgery (RR 2.28; 95% CI 1.04–4.98) were at higher risk for ED.

CONCLUSION

Male survivors of childhood cancer have a greater than 2.6-fold increased risk for ED and certain cancer-specific treatments are associated with increased risk. Attention to sexual health, with its physical and emotional implications, as well as opportunities for early detection and intervention in these individuals may be important.

Keywords: Cancer survivorship, sexual dysfunction, erectile dysfunction, pediatric cancer

INTRODUCTION

With advances in treatment for individuals diagnosed with cancer, survival rates for all ages continue to rise, and there is a growing focus on long-term health and quality of life in this population 1,2. Consequently, there are increasing numbers of survivors of childhood cancer who face challenges as they get older. Over 80% of those diagnosed with childhood cancer currently survive at least 5 years, and most recent estimates show that there were nearly 400,000 childhood cancer survivors in the United States at the start of 2012 3. Despite the significant advancement in knowledge regarding the health status of this population as they age 4,5, relatively little information has been published regarding the sexual health of male survivors of childhood cancer as they move into adulthood.

In general, male survivors of childhood cancers remain at risk for the sexual issues that all aging men face. However, the effects of a cancer diagnosis and treatment may add other risks and concerns 6. We sought to analyze self-reported data from a large cohort of childhood cancer survivors to better understand these issues. These data captured information related to sexual function and relationships, infertility, perceived risk from cancer and treatment, and overall health. In this particular report, we specifically address erectile dysfunction in this group, given the attention this subject has received in other populations and its relative lack in childhood cancer survivors, recognizing that it is only one of the issues affecting patients.

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) cohort, consisting of over 14,000 survivors who were diagnosed from 1970–1986 7, was utilized to assess four specific aims: 1) to determine the frequency and type of sexual activities adult male survivors report compared to adult sibling controls, 2) to determine the prevalence of erectile dysfunction (ED), using the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) , in survivors relative to siblings, 3) to determine the effects of treatment and other socio-demographic, health or cancer-related variables on erectile function, and 4) to identify the frequency and types of therapies used to treat ED in male survivors compared to siblings.

METHODS

The CCSS is a retrospective cohort of five-year survivors of childhood cancer from 26 participating institutions in the United States and Canada who were diagnosed between 1970–1986. Cancer diagnosis and treatment data were collected through medical record abstracts, and ongoing assessment of health and quality of life continues to be obtained through self-report in periodic surveys. Siblings of survivors were also included as a comparison group. Details of the study design and cohort have been previously published 7,8. The institutional review board at each institution approved the study; informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Primary diagnosis and detailed treatment data were collected using a structured medical record abstraction form. Cumulative alkylating agent exposure was calculated using cyclophosphamide equivalent dose 9. The initial baseline questionnaire was administered beginning in 1994 with follow-up questionnaires through 2009.

On the CCSS long-term follow-up #4 questionnaire, male survivors and siblings 18 years and older (at time of questionnaire) were asked if they would consider participating in a study “to better understand fertility and sexual function in males.” A total of 2961 survivors and 723 siblings (of the eligible 4000 male survivors and 1097 male siblings who completed the follow-up #4 questionnaire) expressed interest in completing this additional questionnaire. The Male Health Questionnaire (MHQ) was subsequently mailed in 2008–09 to this group. The MHQ was created to obtain information about sexual experiences and practices as well as sexual function, infertility, testicular function, and perceptions of the impact of cancer diagnosis and treatment on sexual function among this cohort (questionnaires available at https://ccss.stjude.org/documents/questionnaires/original-cohort-questionnaires.html).

Embedded within the MHQ was the previously validated International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) 10. The 15-question IIEF is divided into five domains: erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, intercourse satisfaction, and overall satisfaction. Each domain can be scored separately. An IIEF Erectile Function domain (IIEF-EF) score of ≤ 25 was used as the definition of ED for this study11. The IIEF-EF domain items are designed to assess erectile function in men who have been sexually active within the past four weeks. IIEF-EF domain scores and the binary (yes/no) outcome were computed only for subjects who were sexually active during the four-week period prior to completing the questionnaire. All subjects were asked whether they had ever received treatment for ED. Subjects responding “yes” were asked to provide information about treatment type.

Other definitions were consistent with prior publications involving the CCSS cohort. Cardiac conditions followed the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0 as recently reported among CCSS patients 12 with grade 3 conditions considered severe or disabling and grade 4 conditions considered life-threatening. For physical activity, subjects who reported engaging in at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity on ≥ 5 days per week or at least 20 minutes of vigorous intensity physical activity on ≥ 3 days per week were classified as meeting the CDC guidelines for physical activity that were in place at the time of the follow-up #4 questionnaire 13. This is the same definition used in a previous report regarding physical activity in childhood cancer survivors 14.

Data Analysis

Data collected were tabulated for descriptive statistics, and statistical models were created to compare results between groups. Estimates of the relative risk (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for ED and ED treatment were calculated using generalized linear modeling. A log-link model, rather than a logistic model, was chosen because ED was not rare in the study population and hence the log-link is more suitable for estimating relative risk. The model utilized a Poisson error distribution with robust variance estimation 15. When evaluating associations between cancer treatment variables and the ED outcomes, the factors investigated were testicular radiation, alkylating agents, surgery on the spinal cord or sympathetic nerves, prostate surgery, pelvic surgery, orchiectomy, age at cancer diagnosis, age at MHQ, and race. Preliminary univariable models were estimated, and any factors with a univariable p-value less than 0.20 were considered candidates for further evaluation in a multivariable context. Alkylating agents, orchiectomy, age at cancer diagnosis, and race were not significant in the univariate model and were therefore not included in the final model. The final multivariable model selected for each outcome included factors that showed a multivariable p-value <0.05, plus any additional factors whose omission would alter another factor’s relative risk estimate by more than 10%.

For the survivor versus sibling comparisons, the ED outcome frequencies were tabulated and presented along with the raw (univariable) RR estimate and an adjusted RR estimate that accounts for age at MHQ, general health status, physical activity level, and selected self-reported health conditions (cardiac condition grade 3 or higher, hypertension requiring medication, diabetes, depression, other major psychiatric illness, prostate disease, current use of exogenous testosterone). Analyses comparing survivors versus siblings accounted for potential within-family correlation by utilizing Generalized Estimating Equation methodology. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two-sided.

RESULTS

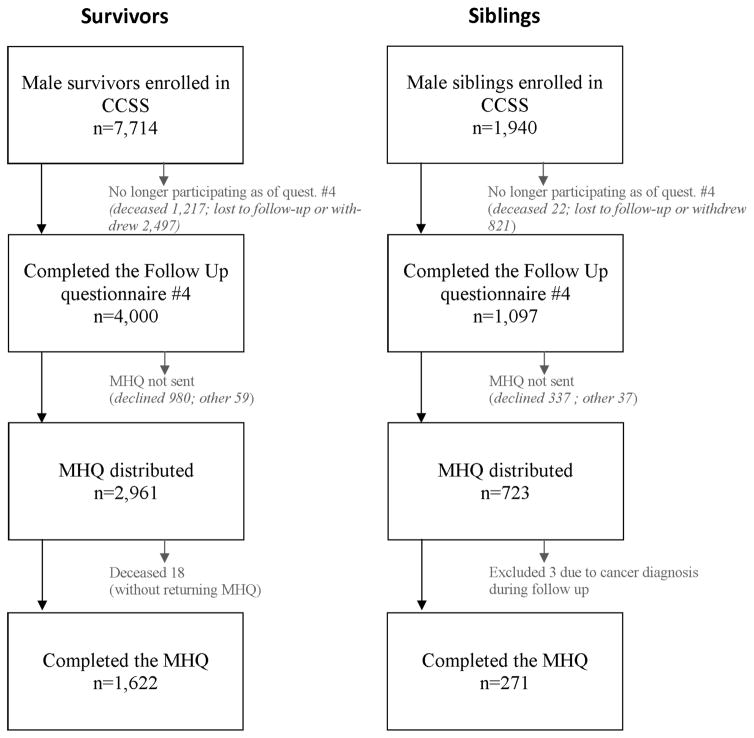

A total of 1622 survivors and 274 siblings completed and returned the MHQ for analysis, and this represented approximately 40% and 25%, respectively, of CCSS males who completed the follow-up #4 questionnaire (Figure 1). Three siblings were excluded from analysis due to a cancer diagnosis reported on a previous CCSS questionnaire. Mean age of analyzed survivors and siblings at time of MHQ completion was 37.2 years (SD 7.3 years) and 38.8 years (SD 8.5 years), respectively. Demographic characteristics and treatment variables for MHQ respondents and nonrespondents have been previously described in detail 16. Briefly, survivors who completed the MHQ were slightly older than survivor nonrespondents (mean age at start of MHQ distribution: 37.2 years for respondents, 35.3 years for nonrespondents). The survivor respondent group had a higher proportion who were white race (93.4%) and married (75.9%), compared to nonrespondents (84.8% white, 60.5% married). Treatment characteristics were similar for MHQ respondents and nonrespondents. Demographic data for the study cohort are provided in Table 1 with comparison of MHQ participants and non-participants in a supplemental table (A).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for Male Health Questionnaire recruitment and participation

Table 1.

Comparison of study participants by survivors and siblings#

| Characteristic | Survivors [Total N=1622] | Siblings [Total N=271] | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Number | (%) | Number | (%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

|

| |||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 1441 | (93) | 253 | (97) | 0.06 |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 30 | (2) | 0 | (0) | |

| Hispanic | 44 | (3) | 5 | (2) | |

| Other | 27 | (2) | 3 | (1) | |

|

| |||||

| Age at MHQ completion | |||||

|

| |||||

| 20–29 years | 270 | (17) | 43 | (16) | 0.03 |

| 30–39 years | 705 | (43) | 107 | (39) | |

| 40–49 years | 562 | (35) | 91 | (34) | |

| 50+ years | 85 | (5) | 30 | (11) | |

| Mean age in years (SD) | 37.4y | (7.3) | 38.8y | (8.5) | |

|

| |||||

| Primary cancer diagnosis | |||||

|

| |||||

| Leukemia | 535 | (33) | -- | ||

| CNS tumors | 138 | (9) | -- | ||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 259 | (16) | -- | ||

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 179 | (11) | -- | ||

| Kidney (Wilms tumor) | 132 | (8) | -- | ||

| Neuroblastoma | 81 | (5) | -- | ||

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 145 | (9) | -- | ||

| Bone cancer | 153 | (9) | -- | ||

|

| |||||

| Age at cancer diagnosis | |||||

|

| |||||

| 0–4 years | 553 | (34) | -- | ||

| 5–9 years | 360 | (22) | -- | ||

| 10–14 years | 377 | (23) | -- | ||

| 15–21 years | 332 | (20) | -- | ||

|

| |||||

| Testicular radiation dose (Gy) | |||||

|

| |||||

| None | 506 | (34) | -- | ||

| <4.0 | 875 | (59) | -- | ||

| ≥4.0 to <10 | 43 | (3) | -- | ||

| ≥ 10 (mean 21; maximum 48) | 71 | (5) | |||

|

| |||||

| Cyclophosphamide Equivalent Dose (mg/m2) | |||||

|

| |||||

| None | 678 | (48) | -- | ||

| >0 to <8000 | 342 | (24) | -- | ||

| ≥8000 to <16,000 | 254 | (18) | |||

| ≥16,000 (mean 22,449; maximum 50,357) | 147 | (10) | -- | ||

|

| |||||

| Surgery on spinal cord/sympathetic nerves | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 44 | (3) | -- | ||

| No | 1493 | (97) | -- | ||

|

| |||||

| Prostate surgery | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 13 | (1) | -- | ||

| No | 1524 | (99) | -- | ||

|

| |||||

| Sexual activity in lifetime | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 1567 | (99) | 270 | (100) | 0.23 |

| -with opposite gender | 1498 | (95) | 262 | (97) | |

| -with same gender | 67 | (4) | 14 | (5) | |

| No | 12 | (1) | 0 | (0) | |

| Mean age of ejacularche in years (SD) | 13.4y | (2.3) | 13.0y | (1.7) | |

|

| |||||

| Sexual activity over past year | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 1482 | (93) | 262 | (97) | <0.0001 |

| No | 114 | (7) | 7 | (3) | |

|

| |||||

| General health (self-reported) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Excellent | 248 | (15) | 57 | (21) | 0.02 |

| Very good | 659 | (41) | 112 | (41) | |

| Good | 541 | (34) | 86 | (32) | |

| Fair or Poor | 160 | (10) | 16 | (6) | |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | |||||

|

| |||||

| Married or living as married | 1053 | (65) | 189 | (70) | 0.14 |

| Not married and not living as married | 561 | (35) | 82 | (30) | |

|

| |||||

| Met CDC recommendations for physical activity | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 796 | (50) | 156 | (58) | 0.02 |

| No | 787 | (50) | 114 | (42) | |

|

| |||||

| Grade 3+ cardiac condition | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 127 | (8) | 7 | (3) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1495 | (92) | 264 | (97) | |

|

| |||||

| Hypertension requiring medication | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 229 | (14) | 28 | (10) | 0.06 |

| No | 1393 | (86) | 243 | (90) | |

|

| |||||

| Diabetes | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 55 | (3) | 5 | (2) | 0.18 |

| No | 1567 | (97) | 266 | (98) | |

|

| |||||

| Currently taking testosterone | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 105 | (7) | 6 | (2) | 0.005 |

| No | 1498 | (93) | 264 | (98) | |

|

| |||||

| Depression (self-reported) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 228 | (14) | 37 | (14) | 0.77 |

| No | 1352 | (86) | 232 | (86) | |

|

| |||||

| Other major psychiatric illness (self-reported) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 26 | (2) | 4 | (2) | 0.84 |

| No | 1518 | (98) | 259 | (98) | |

|

| |||||

| Pelvic surgery (self-reported) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 42 | (3) | 2 | (1) | 0.06 |

| No | 1520 | (97) | 265 | (99) | |

|

| |||||

| Prostate disease (self-reported) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Yes | 35 | (2) | 12 | (5) | 0.09 |

| No | 1507 | (98) | 252 | (95) | |

Due to information not provided for some study participants, total numbers for each group do not always sum to total number in cohort.

Frequency of sexual activities

All siblings and 99.2% of survivors reported sexual activity in their lifetime (p=0.23, Table 1), with 92.9% of survivors and 97.4% of siblings self-reporting sexual activity alone or with a partner in the past year (p<0.0001). Survivors that reported a lifetime experience with the opposite gender were 94.9% (vs. 97.0% of siblings) and with the same gender were 4.2% (vs. 5.2%). Past year sexual experience of survivors with opposite gender was 80.5% (vs. 82.2%) and with same gender was 2.2% (vs. 3.3%).

Prevalence of erectile dysfunction

A total of 12.3% (95% CI 10.4%–14.3%) of survivors and 4.2% (95% CI 2.0%–7.9%) of siblings had IIEF-EF scores ≤ 25 (Table 2). Survivors were at greater risk for ED than siblings (RR 2.63; 95% CI 1.40–4.97) among subjects with recent (past four weeks) sexual activity (Table 3). Comparatively, when separately asked the single questions, “How frequently in the past month have you had the problems listed…,” 23.9% and 31.7% of survivors reported some degree of “difficulty getting an erection” or “losing an erection during sexual activity”, respectively. This compared to 19.8% (p=0.15) and 23.4% (p<0.01) of siblings, respectively. The mean scores for the remaining domains of the IIEF are listed in a supplemental table (B).

Table 2.

Frequency of ED and treatment for ED

| IIEF-EF ≤25 | Ever received treatment for ED | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Survivors | Siblings | Survivors | Siblings | |||||

| Frequency | (% Yes) | Frequency | (% Yes) | Frequency | (% Yes) | Frequency | (% Yes) | |

| Overall # | 143 / 1166 | (12) | 9 / 213 | (4) | 88 / 1474 | (6) | 6 / 260 | (2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Age at MHQ compleJon †, ‡ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 20–29 years | 13 / 176 | (7) | 2 / 30 | (7) | 4 / 242 | (2) | 1 / 38 | (3) |

| 30–39 years | 54 / 519 | (10) | 0 / 87 | (0) | 31 / 641 | (5) | 2 / 105 | (2) |

| 40–49 years | 65 / 419 | (16) | 2 / 76 | (3) | 38 / 520 | (7) | 1 / 89 | (1) |

| 50+ years | 11 / 52 | (21) | 5 / 19 | (26) | 15 / 71 | (21) | 2 / 27 | (7) |

|

| ||||||||

| General health (self-reported) †, ‡ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Excellent | 7 / 200 | (4) | 1 / 49 | (2) | 9 / 234 | (4) | 0 / 54 | (0) |

| Very good | 48 / 522 | (9) | 6 / 91 | (7) | 18 / 632 | (3) | 1 / 107 | (1) |

| Good | 60 / 358 | (17) | 2 / 62 | (3) | 40 / 476 | (8) | 3 / 83 | (4) |

| Fair/poor | 28 / 84 | (33) | 0 / 11 | (0) | 21 / 129 | (16) | 2 / 16 | (13) |

|

| ||||||||

| Met CDC recommendations for physical activity | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 74 / 597 | (12) | 6 / 126 | (5) | 36 / 736 | (5) | 3 / 150 | (2) |

| No | 66 / 541 | (12) | 3 / 86 | (3) | 52 / 703 | (7) | 3 / 109 | (3) |

|

| ||||||||

| Grade 3+ cardiac condiJon † | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 15 / 72 | (21) | 1 / 4 | (25) | 10 / 107 | (9) | 0 / 7 | (0) |

| No | 128 / 1094 | (12) | 8 / 209 | (4) | 78 / 1367 | (6) | 6 / 253 | (2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Hypertension requiring medicaJon †, ‡ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 26 / 156 | (17) | 3 / 21 | (14) | 19 / 198 | (10) | 1 / 27 | (4) |

| No | 117 / 1010 | (12) | 6 / 192 | (3) | 69 / 1276 | (5) | 5 / 233 | (2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Diabetes †, ‡ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 7 / 29 | (24) | 2 / 3 | (67) | 8 / 48 | (17) | 1 / 5 | (20) |

| No | 136 / 1137 | (12) | 7 / 210 | (3) | 80 / 1426 | (6) | 5 / 255 | (2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Depression (self-reported) †, ‡ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 36 / 142 | (25) | 2 / 28 | (7) | 29 / 200 | (15) | 2 / 33 | (6) |

| No | 103 / 1004 | (10) | 7 / 183 | (4) | 56 / 1245 | (4) | 4 / 225 | (2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Other major psychiatric illness (self-reported) ^, ‡ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 5 / 12 | (42) | 0 / 3 | (0) | 7 / 23 | (30) | 0 / 4 | (0) |

| No | 128 / 1111 | (12) | 9 / 203 | (4) | 74 / 1391 | (5) | 6 / 248 | (2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Prostate disease (self-reported) ‡ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 7 / 21 | (33) | 0 / 11 | (0) | 10 / 31 | (32) | 1 / 12 | (8) |

| No | 126 / 1099 | (11) | 9 / 196 | (5) | 72 / 1382 | (5) | 5 / 241 | (2) |

|

| ||||||||

| Currently taking testosterone (self-reported) †, ‡ | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Yes | 19 / 68 | (28) | 0 / 5 | (0) | 14 / 84 | (17) | 2 / 6 | (33) |

| No | 124 / 1092 | (11) | 9 / 207 | (4) | 74 / 1383 | (5) | 4 / 253 | (2) |

Indicates that this factor was significantly associated (p <0.05) with IIEF-EF≤25 overall among all participants. Where numbers permitted, interaction tests were performed to assess whether the association with IIEF-EF≤25 differed for survivor and sibling groups; no statistically significant interactions were found.

Indicates that this factor was significantly associated (p <0.05) with ever having received treatment for ED overall among all participants. Where numbers permitted, interaction tests were performed to assess whether the association with ED treatment differed for survivor and sibling groups; no statistically significant interactions were found.

Rates calculated on total number of participants on whom information was available

Psychiatric illness other than depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder

IIEF-EF = International Index of Erectile Function (Erectile Function Domain); ED = erectile dysfunction

Table 3.

Multivariable comparison summary of survivors and siblings for ED and treatment of ED

| Outcome measure | Frequency (% Yes) | Unadjusted Relative Risk (95% CI) | Adjusted Relative Risk1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ED | |||

| Survivors | 143/1166 (12%) | 2.90 (1.50, 5.60) | 2.63 (1.40, 4.97) |

| Siblings | 9/213 (4%) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Self-reported receiving treatment for ED | |||

| Survivors | 88/1474 (6%) | 2.59 (1.14, 5.86) | 2.73 (1.26, 5.94) |

| Siblings | 6/260 (2%) | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

Adjusted for age at time of MHQ, general health level, physical activity, grade 3 or higher cardiac condition, hypertension requiring medication, diabetes, depression and other major psychiatric illness, prostate disease and current use of exogenous testosterone.

IIEF-EF = International Index of Erectile Function (Erectile Function Domain); ED = erectile dysfunction

Risk factors related to sexual function in survivors

In addition to older age, testicular radiation dose ≥ 10 Gy (RR 3.55; 95% CI 1.53–8.24), history of surgery involving the spinal cord or sympathetic nerves (RR 2.87; 95% CI 1.36–6.05), and history of prostate surgery (RR 6.56; 95% CI 3.84–11.20) or pelvic surgery (RR 2.28; 95% CI 1.04–4.98) were all significantly associated with ED among the survivors (Table 4). Health status variables assessed at time of the MHQ (e.g. general health) were not included in the treatment factors model because they may themselves be downstream consequences of treatment factors.

Table 4.

| Frequency (%) of survivors with ED† | Relative risk for ED (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at MHQ completion | ||||

|

| ||||

| 50+ years | 8 / 35 | (23) | 3.47 (1.39–8.69) | 0.008 |

| 40–49 years | 53 / 358 | (15) | 2.12 (1.10–4.09) | 0.02 |

| 30–39 years | 42 / 448 | (9) | 1.42 (0.73–2.76) | 0.30 |

| 20–29 years | 11 / 161 | (7) | 1.00 (referent) | -- |

|

| ||||

| Testicular radiation dose | ||||

|

| ||||

| ≥10 Gy | 5 / 17 | (29) | 3.55 (1.53–8.24) | 0.003 |

| ≥4.0 Gy to <10 Gy | 5 / 21 | (24) | 1.45 (0.56–3.78) | 0.45 |

| >0 Gy <4.0 Gy | 72 / 559 | (13) | 1.32 (0.89–1.95) | 0.17 |

| None | 29 / 340 | (9) | 1.00 (referent) | -- |

|

| ||||

| Surgery on spinal cord/sympathetic nerves (records/self-reported) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 6 / 20 | (30) | 2.87 (1.36–6.05) | 0.006 |

| No | 105 / 937 | (11) | 1.00 (referent) | -- |

|

| ||||

| Prostate surgery (records/self-reported)^ | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 7 /10 | (70) | 6.56 (3.84–11.20) | <0.0001 |

| No | 104 / 947 | (11) | 1.00 (referent) | -- |

|

| ||||

| Pelvic surgery (self-reported) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Yes | 7 / 21 | (33) | 2.28 (1.04–4.98) | 0.04 |

| No | 103 / 956 | (11) | 1.00 (referent) | -- |

Only cancer treatment factors and basic demographic characteristics were considered in this model. Health status variables assessed at time of the Men’s Health Questionnaire (e.g. general health) were not included in the treatment factors model because they may themselves be downstream consequences of treatment factors.

For analyses assessing the impact of treatments received for primary cancer, subjects who experienced a recurrence or second malignant neoplasm were excluded.

Biopsies or other diagnostic procedures not included

ED=erectile dysfunction; IIEF-EF = International Index of Erectile Function (Erectile Function Domain)

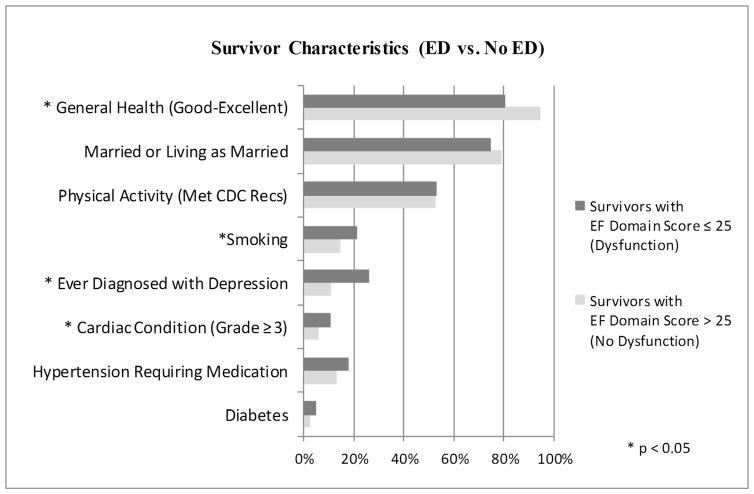

Long-term follow-up characteristics of survivors with and without ED (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Health and lifestyle characteristics of survivors by IIEF-EF score

A significantly higher percentage of the survivors with IIEF-EF scores in the normal range reported good to excellent general health (94.5% vs. 80.4%), and a significantly lower percentage reported an advanced cardiac condition (5.6% vs. 10.5%), previous diagnosis of depression (10.5% vs. 25.9%), or history of smoking (14.4% vs. 21.0%) when compared to survivors with lower IIEF-EF scores (p<0.05).

Frequency of treatment for sexual dysfunction

A total of 5.9% of survivors and 2.3% of siblings reported ever having received treatment for ED (RR 2.73; 95% CI 1.26–5.94) (Table 3). With rare exception, reported ED treatment consisted of oral medication.

DISCUSSION

When cancer occurs early in life, the cancer experience may have an adverse effect on an individual’s sexual functioning in the formative years that may potentially persist throughout his lifetime. In this study, we characterized erectile dysfunction in a large cohort of adult males treated for childhood cancers and a sibling comparison group based on responses collected about ED and other issues in the MHQ. The data suggest that survivors may be at higher risk for subsequent ED. Previous work from our group demonstrated that these survivors are also at higher risk for male infertility but that many go on to father children, although they may have fewer children than they originally desire16.

Male survivors who responded to the MHQ were less likely to have engaged in some type of sexual experience in the year prior to the survey than their siblings, although the vast majority of both groups were sexually active. There may be multiple reasons, including sexual dysfunction, for being less sexually active. Based on analysis of IIEF-EF scores, cancer survivors had significantly higher RR for ED than siblings. The relatively low percentage of total subjects reaching the definition of ED is most likely a reflection of the lower ages of the group compared to other well-known general health cohorts, such as the Massachusetts Male Aging Study, where more than half of men aged 40–70 years reported erectile dysfunction 17. Less data exist on the prevalence of erectile dysfunction in younger, healthy men, and reports have varied widely. Study populations for this group are historically heterogeneous, and the incidence is often different based on the country of origin. The multinational Cross-National Survey on Male Health Issues (CNSMHI) reported the prevalence of ED in men <40 years of age at 4–6%, although the percentage varied slightly between individual countries in the study, with the U.S. showing values similar to the UK, Italy and Germany but higher than France and Spain in the 30–39 year-old patient subgroup, the range where the majority MHQ patients reside18. For CNSHMI, the categorization of ED was based on a single self-report question, but the percentage of subjects <40 years defined as having ED is comparable to our MHQ sibling control group.

ED can result from vascular, neurologic, psychogenic, and/or hormonal factors, and often the etiology in individual patients is multifactorial 18. For the cancer patient, the physiologic alteration that can result from cancer treatment exposures, including chemotherapy, radiation and surgery, is often compounded by the psychological impact of the diagnosis and treatment experience on intimacy and sexual function 20–22. In previous reports, adult survivors of childhood cancer have expressed concern regarding their sexual function 6, 23–25. In the current study, survivors with a history of higher dose testicular radiation, spinal cord/nerve surgery, prostate surgery, or pelvic surgery did have a higher risk of ED than survivors without these exposures. While erectile dysfunction has been associated with testosterone deficiency 26, high dose alkylators, which can cause Leydig cell damage and testosterone deficiency, were not associated with increased risk of ED in this study. Patients exposed to high-dose alkyators had no statistically higher use of testosterone replacement therapy that could help explain this result. Previous reports have also shown Leydig cell damage can occur at testicular radiation doses of ≥20 Gy27, but there was suggestion of ED in patients who had received lower doses.

Based on experience in prostate cancer patients, we know that radiation treatment to the pelvis can induce ED, possibly through effects on the corpora cavernosa or penile bulb 28. The fact that significant differences in IIEF-EF scores were seen with exposures of ≥10 Gy to the testes may suggest vulnerability for permanent changes of the penile structures at a young age, although the specific dose threshold could not be unequivocally determined due to the smaller numbers of patients receiving the higher doses. Adults may be more resistant to radiation, as doses of around 50 Gy to the penile bulb were needed to show significant effects on erectile function 29. All CCSS survivors responding to the MHQ had less than this dose, and only 5% received > 10 Gy. Nerves controlling erectile function course along the posterior-lateral prostate, and surgery in that region likely has effects on these neurovascular bundles, which explains the higher risk of ED in patients who had prostate or pelvic surgery 30. None of the survivors who had prostate surgery also had higher dose radiation therapy. Importantly, the techniques of both radiation and surgical therapy for prostate cancer have continued to advance over the years, and these refinements may lessen the adverse effects for future patients. Although the numbers of subjects having pelvic or spinal surgery is small in this series, the association with ED was strongly significant in the multivariable model. While the connection between ED and pelvic surgery may not be surprising and likely true at any age, it is important to highlight that treatment to this area at a young age may have long-lasting ramifications for sexual function, even if the patient/family and treating provider are not considering that as a priority at the time.

Erectile function is often difficult to measure as it can change based on situational influences. Therefore, self-reported questionnaires are often used so that patients can report on collective experiences over a period of time rather than at single points in time. The self-report nature of the MHQ, like all self-report questionnaires, is potentially a limitation of the current study. Likewise, the IIEF was primarily first used to assess responses of men during drug development of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors and may have differing utility in other clinical scenarios 31. Nonetheless, the IIEF represents one of the most widely used assessments for ED, so its inclusion as an outcome measure seems appropriate and understandable to the clinician. The nature of the study does not allow for collection of data through individual patient interviews, but clearly qualitative research methodology, like interviews, combined with structured questionnaire responses would augment the current interpretation of the data22.

Data collection is also limited by the subjects’ ability and willingness to fully respond to MHQ questions. CCSS subjects complete a number of questionnaires during participation, and motivation to complete a particular set of questions, like the MHQ, may be different for individual subjects. Nonetheless, an extensive effort was made to collect and analyze data in a standardized fashion across all subjects to allow meaningful comparisons. Despite the relatively lower response rate to the questionnaire, the end study sample represents the largest known group to address these questions in this population. The demonstrated higher RR for receiving treatment for ED in the survivor group compared to the sibling group appears to corroborate the higher RR of ED, as measured by the IIEF-EF.

Finally, men place significant importance on sexual functioning, yet they often fail to discuss it with their physicians 32. Additionally, physicians frequently do not ask about sexual concerns, resulting in many disorders going untreated 33. As cancer patients survive years beyond treatment of their life-threatening disease, quality of life issues become increasingly important. Understanding sexual concerns of male childhood cancer survivors will allow treating clinicians to better predict male health late effects for future generations, as well as provide treatment for those who experience difficulties. The evidence-based Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines of the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) recommend screening for low testosterone and infertility after high dose alkylator therapy/heavy metal exposure, testicular radiation, and orchiectomy; screening for psychosexual dysfunction after spinal cord surgery; and screening for sexual dysfunction after pelvic surgery34. Screening tools, like the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM)35, can assist both patients and providers in identifying items of concern, but further development of questionnaires for this population may be important. As knowledge and treatment options have expanded since the time of diagnosis for these men in this study, examination of adult survivors in the future will also be important.

CONCLUSIONS

As measured by the IIEF-EF, male survivors of childhood cancer demonstrate higher risk of ED than their siblings. Likewise, survivors were more likely than siblings to have received treatment for ED. Age greater than 40 years, testicular radiation ≥10 Gy, surgery on spinal cord/nerves and prostate or pelvic surgery were significantly associated with ED in survivors. Further studies on ED in this patient population and on early intervention to either prevent or mitigate ED should be performed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.De Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:561–70. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: lifelong risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2012. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: Apr, 2015. < http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/>, based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER website. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson MM, Ness KK, Gurney JG, et al. Clinical ascertainment of health outcomes among adults treated for childhood cancer. JAMA. 2013;309:2371–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs LA, Pucci DA. Adult survivors of childhood cancer: the medical and psychosocial late effects of cancer treatment and the impact on sexual and reproductive health. J Sex Med. 2013;10(suppl 1):120–6. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a National Cancer Institute-supported resource for outcome and intervention research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2308–2318. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, et al. Pediatric cancer survivorship research: experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2319–2327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green D, Nolan V, Goodman P, et al. The cyclophosphamide equivalent dose as an approach for quantifying alkylating agent exposure: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:53–67. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC, Smith MD, et al. Mishra Diagnostic evaluation of the erectile function domain of the International Index of Erectile Function. Urology. 1999;54:346–351. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00099-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armstrong GT, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, et al. Aging and risk of severe, disabling, life-threatening, and fatal events in the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1218–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ness KK, Leisenring WM, Huang S, et al. Predictors of inactive lifestyle among adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2009;115:1984–94. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wasilewski-Masker K, Seidel KD, Leisenring W, et al. Male infertility in long-term survivors of pediatric cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:437–47. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0354-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, et al. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shabsigh R, Perelman MA, Laumann EO, et al. Drivers and barriers to seeking treatment for erectile dysfunction: a comparison of six countries. BJU Int. 2004;94(7):1055–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lue TF. Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1802–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006153422407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson AL, Long KA, Marsland AL. Impact of childhood cancer on emerging adult survivors’ romantic relationships: a qualitative account. J Sex Med. 2013;10(suppl 1):65–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson AL, Marsland AL, Marshal MP, et al. Romantic relationships of emerging adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:767–74. doi: 10.1002/pon.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stinson JN, Jibb LA, Greenberg M, et al. A qualitative study of the impact of cancer on romantic relationships, sexual relationships, and fertility: perspectives of Candian adolescents and parents during and after treatment. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2015;4(2):84–90. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2014.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bober SL, Zhou ES, Chen B, et al. Sexual function in childhood cancer survivors: a report from Project REACH. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2084–93. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sundberg KK, Lampic C, Arvidson J, et al. Sexual function and experience among long-term survivors of childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpentier MY, Fortenberry JD. Romantic and sexual relationships, body image, and fertility in adolescent and young adult testicular cancer survivors: a review of the literature. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:115–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isidori AM, Buvat J, Corona G, et al. A critical analysis of the role of testosterone in erectile function: from pathophysiology to treatment-a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2014;65:99–112. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sklar C. Reproductive physiology and treatment-related loss of sex hormone production. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:2–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199907)33:1<2::aid-mpo2>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van der Wielen GJ, Mulhall JP, Incrocci L. Erectile dysfunction after radiotherapy for prostate cancer and radiation dose to the penile structures: a critical review. Radiother Oncol. 2007;84:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roach M, Nam J, Gagliardi G, et al. Radiation Dose-Volume Effects and the Penile Bulb. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(suppl 3):S130–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.04.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walsh PC. The discovery of the cavernous nerves and development of nerve sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 2007;177:1632–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Gendrano N. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a state-of-the-science review. Int J Impot Res. 2002;14:226–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marwick C. Survey says patients expect little physician help on sex. JAMA. 1999;281:2173–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.23.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metz M, Seifert MJ. Men’s expectations of physicians in sexual health concerns. J Sex Marital Ther. 1990;16:79–88. doi: 10.1080/00926239008405254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Children's Oncology Group. Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers, Version 4.0. Monrovia, CA: Children's Oncology Group; Oct, 2013. [Accessed August 11, 2015]. Available on-line: www.survivorshipguidelines.org. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cappelleri JC, Rosen RC. The Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM): a 5-year review of research and clinical experience. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:307–19. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.