Abstract

Among the neuromodulators that regulate prefrontal cortical circuit function, the catecholamine transmitters norepinephrine (NE) and dopamine (DA) stand out as powerful players in working memory and attention. Perturbation of either NE or DA signaling is implicated in the pathogenesis of several neuropsychiatric disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, and drug addiction. Although the precise mechanisms employed by NE and DA to cooperatively control prefrontal functions are not fully understood, emerging research indicates that both transmitters regulate electrical and biochemical aspects of neuronal function by modulating convergent ionic and synaptic signaling in the prefrontal cortex (PFC). This review summarizes previous studies that investigated the effects of both NE and DA on excitatory and inhibitory transmissions in the prefrontal cortical circuitry. Specifically, we focus on the functional interaction between NE and DA in prefrontal cortical local circuitry, synaptic integration, signaling pathways, and receptor properties. Although it is clear that both NE and DA innervate the PFC extensively and modulate synaptic function by activating distinctly different receptor subtypes and signaling pathways, it remains unclear how these two systems coordinate their actions to optimize PFC function for appropriate behavior. Throughout this review, we provide perspectives and highlight several critical topics for future studies.

Keywords: Dopamine, Norepinephrine, Prefrontal cortex, Neuromodulator, Psychiatric disorders

1. The roles NE and DA play in regulating prefrontal synaptic function

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is well-known for its role in numerous cognitive and executive functions, such as attention, working memory, decision making, and inhibitory control. PFC dysfunction has long been recognized as a central feature of many psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and drug addiction. PFC-associated cognitive deficits are largely resistant to current treatment approaches, and greater cognitive deficits often predict worse functional outcomes. Thus, it is critical to understand the molecular and cellular influences that modulate PFC function in order to develop intelligent medications for related psychiatric disorders.

The catecholamine neurotransmitters norepinephrine (NE) and dopamine (DA) stand out as two powerful players in regulating PFC-dependent functions. Given that disruption of the excitation/inhibition balance in the PFC has been associated with many aforementioned psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia (Krause et al., 2013; Lisman, 2012; Winterer and Weinberger, 2004; Yizhar et al., 2011) and ADHD (Moll et al., 2003; Pouget et al., 2009; Won et al., 2011), the individual actions as well as cooperative effects of both transmitters on synaptic transmission, intracellular signaling, and neuronal integration within immature and mature PFC circuitry are thus critical for the execution of prefrontal functions. How NE and DA, individually or synergistically, activate their respective receptors and the effects this on prefrontal functioning at the cellular, physiological, and behavioral level has been well-studied and reviewed in the past (Arnsten, 2011; Arnsten and Pliszka, 2011; Arnsten et al., 2015a; Arnsten et al., 2012b; Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003; Berridge and Arnsten, 2013; Brennan and Arnsten, 2008; Clark and Noudoost, 2014; Puig et al., 2014; Ramos and Arnsten, 2007; Seamans and Yang, 2004; Spencer et al., 2015; Tritsch and Sabatini, 2012). Nevertheless, recent compelling evidence demonstrates that the functional interaction between NE and DA exerts powerful biological effects by activating converging synaptic pathways in PFC circuitry; however this interaction has yet to be well characterized. In the scope of this review, we will focus on the synergistic interactions of NE and DA on synaptic signaling in the PFC. This interaction serves as another level of study that will significantly improve our understanding of how these two catecholamine neurotransmitters modulate prefrontal functions.

Catecholaminergic projections to the cerebral cortex stem from two main sources, NE neurons of the locus coeruleus (LC) in the brainstem and DA neurons of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) in the midbrain. The PFC is a main cortical target of both NE and DA innervations (Knable and Weinberger, 1997; Ramos and Arnsten, 2007) with both neuronal systems modulating PFC activity in addition to memory and attentional performance. Overall noradrenergic fibers target the entire cerebral cortex with a more even distribution, whereas dopaminergic fibers are more restricted, having significantly more innervations in the PFC than in other cortical regions such as the primary visual and auditory cortex or somatosensory and motor cortex (Agster et al., 2013). In addition, laminar differences exist between NE and DA distributions within the PFC; noradrenergic fibers innervate both superficial and deep layers of the cortex, while dopaminergic fibers exhibit a regional variations in laminar pattern (Lewis and Morrison, 1989; Lewis et al., 2001; Nomura et al., 2014; Williams and Goldman-Rakic, 1993).

Recent morphological evidence demonstrates the presence of synaptic complexes formed by axospinous contacts, where dendritic spines of prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons appear to be a common target of both noradrenergic and dopaminergic inputs (Mitrano et al., 2014; Nomura et al., 2014). This specific synaptic microenvironment offers as a great potential for physiological and biochemical interactions to occur between the noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmitter systems, and this interaction will undoubtedly affect PFC functions such as working memory and attention.

Both NE and DA receptors are widely expressed in the CNS, with their distribution and expression levels largely mirroring the density of innervating fibers. Consistently, adrenergic receptors exhibit a broader distribution pattern in the rodent PFC than dopaminergic receptors, which have higher expression in deep cortical layers (Nomura et al., 2014; Santana et al., 2009). It is now clear that different subtypes of adrenergic or dopaminergic receptors have a laminar-specific distribution within the PFC that may contribute to the local circuitry functions.

The adrenergic receptors exhibit wide diversity, with five receptor subtypes having been cloned. These receptors are classified into two main families based on their structural, pharmacological, and signaling properties: α (α1 and α2 receptors) family and β (β1, β2 and β3 receptors) family. Specifically, both α1 and α2 receptors are distributed in the PFC (Aoki et al., 1994; Aoki et al., 1998a; Goldman-Rakic et al., 1990). The α2 receptors are located in both pre- and postsynaptic sites, with the α2A receptor subtype densest in the PFC (Aoki et al., 1994; Aoki et al., 1998). It is reported that approximately 20% of α1 receptors are distributed in GABAergic neurons as well (Nakadate et al., 2006). At subcellular levels, α2 receptor immunoreactivity in the PFC was associated with synaptic and non-synaptic plasma membranes of dendrites and perikarya as well as perikaryal membranous organelles. In addition, cortical tissue exhibited prominent immunoreactivity of the α2 receptor within spine heads (Aoki et al., 1994; Aoki et al., 1998a). The β-adrenergic receptors are densest in the intermediate layers of the PFC (Goldman-Rakic et al., 1990), with β1 receptors in highly enriched in the adult cortex (Rainbow et al., 1984; Summers et al., 1995). Studies in primate PFC have also localized β2 receptors on both glutamatergic pyramidal neurons and GABAergic interneurons (Aoki et al., 1998b). Interestingly, the distribution and density of adrenergic (α1, α2, and β) receptors in the neocortex of rhesus monkeys display age-related changes in a laminar-specific manner. The density of α2 receptors declined in layer I, but β receptors, which are largely confined to the deep layers of the PFC, increased during aging (Bigham and Lidow, 1995).

Adrenergic receptors are the catecholaminergic targets of G protein-coupling. Generally, the α1 receptors are coupled to Gq proteins, and thus activate phospholipase C (PLC) and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) intracellular signaling, leading to activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and release of intracellular calcium (Birnbaum et al., 2004). NE has relatively lower affinity for α1 receptors, of which there are 3 subtypes: the α1A, α1B, and α1D (Hieble et al., 1995). The α2 receptors also consist of 3 subtypes (α2A, α2B and the α2C) and have the highest affinity to NE (MacDonald et al., 1997). Activation of α2 receptors stimulates Gi proteins, which are negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase (AC), leading to the reduction of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and the inactivation of protein kinase A (PKA). In contrast, β receptors have the lowest affinity to the NE and are coupled to Gs, which increases AC and activates cAMP signaling pathway (Table 1).

Table 1.

Localization and distribution of NE and DA receptor subtypes in the PFC

| Receptor class | Receptors | Coupled to | Localization | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1-family | α1A, α1B, α1D | Gq (PKC ↑, Ca2+ ↑) | pre- and post-synaptic | superficial and deep layers |

| α2-family | α2A, α2B, α2C | Gi (PKA ↓) | pre- and post-synaptic | superficial and deep layers |

| β-family | β1, β2, β3 | Gs (PKA ↑) | pre- and post-synaptic | intermediate layers |

| D1-like | D1, D5 | Gs (PKA ↑) | post-synaptic | superficial and deep layers |

| D2-like | D2, D3, D4 | Gi (PKA ↓) β-arrestin 2 (D2, D3) | pre- and post-synaptic | mainly deep layers |

DA receptors are commonly classified into two major subtypes: D1 and D5 receptors are members of the D1-like family, whereas D2, D3 and D4 receptors are members of the D2-like family (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011; Missale et al., 1998; Missale et al., 2010). D1 and D2 receptors are the two most abundant subtypes expressed in both pyramidal neurons and interneurons throughout layers II to VI of the PFC, with their prominent distribution restricted to the deep cortical layers, especially with respect to D2 receptors (Santana et al., 2009). Generally, D1 receptors display a more widespread distribution and higher expression level than D2 receptors (Santana et al., 2009; Tritsch and Sabatini, 2012). In fact, co-localization of D1 and D2 receptors in the same prefrontal cortical neuron is relatively low (Vincent et al., 1993). In the primate PFC, cellular distribution of D5 receptors in pyramidal neurons overlaps with that of D1 receptors (Bergson et al., 1995), while D3 and D4 receptors are mainly expressed on GABAergic interneurons (Khan et al., 1998; Mrzljak et al., 1996).

DA receptors are also G protein-coupled. Similar to β receptors, the D1-like family stimulates GS, which is positively coupled to AC, leading to elevated cAMP levels and activation of PKA. In contrast, similar to α2 receptors, the D2-like family activates Gi proteins, which directly inhibits the formation of cAMP by inhibiting AC. In addition, the D2 family has also been shown to signal through an independent pathway involving the formation of a complex composed of Akt (protein kinase B), protein phosphatase-2A (PP2A), and β-arrestin 2 (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011), which will be further elaborated in the GSK-3 signaling section below. Moreover, D2-like receptors directly regulate the ion channels responsible for regulating and generating calcium influx through release of the Gβγ subunit upon receptor activation (Hernandez-Lopez et al., 2000). Although the affinity of D2-like receptors for DA has been shown to be 10- to 100-fold greater than that of D1-like receptors, at least in the striatum (Beaulieu and Gainetdinov, 2011), both high and low affinity states of D1 and D2 receptors exist and both exhibit similar nanomolar affinities for DA in their high affinity states [reviewed in (Tritsch and Sabatini, 2012)].

2. NE and DA are essential for PFC functioning

NE has marked effects on PFC function, especially in the context of attention and stress (Morilak et al., 2005). These physiological processes are particularly relevant to ADHD and PTSD. It has been reported that low to moderate levels of NE augment PFC function, whereas high concentrations of NE impair function. As such, NE exhibits an inverted-U relationship between LC-NE activity and optimal performance on attention tasks (Aston-Jones and Cohen, 2005; Berridge and Waterhouse, 2003). Interestingly, the beneficial versus detrimental actions of NE appears to be associated with distinct adrenoceptors. Moderate levels of NE improve PFC function, possibly via α2A receptors; whereas high levels of NE may engage low affinity α1 receptors and blunt PFC performance (Arnsten, 2000; Arnsten et al., 2012b; Lapiz and Morilak, 2006). To further support this notion, many studies have focused on elucidating the mechanisms and found that α2 receptor agonists are able to improve PFC function in mice (Franowicz et al., 2002), rats (Tanila et al., 1996), monkeys (Li et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2007), and even humans (Jakala et al., 1999).

DA's role in PFC function appears to be broader and better characterized than that of NE. Since the study of Brozoski et al. (Brozoski et al., 1979) that established the critical role of DA on PFC working memory function (Castner and Williams, 2007), we have learned that not only is DA critical for PFC cognitive functioning, but NE as well. Several studies have suggested that either too little (Sawaguchi and Goldman-Rakic, 1994) or too much (Zahrt et al., 1997) D1 receptor stimulation impairs PFC function (Arnsten and Goldman-Rakic, 1998; Granon et al., 2000). Thus, low doses of D1 agonists improve working memory and attention regulation (Cai and Arnsten, 1997; Granon et al., 2000), while high level of DA, which overstimulate D1 receptors and activate D2 receptors ( e.g., under extremely stressful conditions), impairs PFC function (Murphy et al., 1996); therefore forming an “inverted U” curve of performance much like NE (Arnsten et al., 2012b; Vijayraghavan et al., 2007; Williams and Castner, 2006). Electrophysiological experiments performed in monkeys suggest similar findings at the cellular level. Low levels of D1 receptor stimulation induced by iontophoresis of DA, increased delay-related persistent activity relative to background firing (Sawaguchi et al., 1988), while higher levels of D1 receptor stimulation decrease delay-related activity (Vijayraghavan et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2004; Williams and Goldman-Rakic, 1995).

However, it appears that neither NE nor DA can act independently without affecting the other system. Both the NE and DA systems are required for proper operation of prefrontal functions because a selective impairment in either transmission within the PFC leads to disrupted working memory (Arnsten, 2004; Arnsten and Jin, 2014; Brozoski et al., 1979; Levy, 2009; Ramos and Arnsten, 2007; Vijayraghavan et al., 2007; Williams and Goldman-Rakic, 1995). Previous studies have also shown that both NE and DA levels undergo moderate and comparably sustained increases during a delayed alternation task in trained animals (Rossetti and Carboni, 2005), and DA may be taken up through the NE transporter (NET) in brain regions with low levels of DA transporter (DAT), such as PFC (Moron et al., 2002; Sesack et al., 1998). Moreover, Ventura and colleagues reported that intact prefrontal cortical NE transmission is necessary for DA release, further indicating that the two systems are inseparable in order for normal execution of prefrontal functions (Ventura et al., 2003; Ventura et al., 2005; Ventura et al., 2007). Additional studies have shown that complementary levels of catecholamine receptor stimulation are needed to optimize PFC cognitive function (Arnsten and Li, 2005; Pascucci et al., 2007). Collectively, these studies suggest that NE and DA pathways work together to exert an essential modulatory influence on PFC-dependent working memory and attention. While the results of these investigations emphasize the complementary roles of the NE and DA systems in normal PFC functions and their application in treatment of disorders with prominent symptoms of PFC dysfunction, the precise mechanisms through which these effects occur are not yet fully understood. We will further discuss how NE and DA interact on cells and circuits in a major catecholaminergic terminal field of the PFC in the sections that follow.

3. NE and DA modulation of synaptic transmission in the PFC circuitry

3.1 NE vs. DA modulation of PFC excitatory circuitry

The PFC circuitry includes both excitatory glutamatergic pyramidal neurons and inhibitory GABAergic interneurons. These two types of neurons form local excitatory microcircuits where recurrent excitation occurs among pyramidal neurons, which is regulated by feedback inhibitory networks via GABAergic interneurons.

NE modulates both excitatory and inhibitory circuitries, effecting cortical neurons in a cell- and receptor-specific manner. Kobayashi et al. reported that activation of α1- and β-adrenoceptors modulates excitatory synaptic transmission in the cerebral cortex in an opposite manner. By using a voltage sensitive dye with in vitro optical imaging, Kobayashi et al. revealed that an α1-adrenoceptor agonist, phenylephrine, suppressed excitatory propagation evoked by stimulation of white matter, whereas a β-adrenoceptor agonist, isoproterenol, potentiated the excitatory propagation (Kobayashi, 2007; Kobayashi et al., 2009). The α1 receptor-mediated suppressive action on synaptic function is consistent with a study conducted in rat mPFC in which adrenergic modulation of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors was differentially regulated by G protein signaling (RGS) and spinophilin (Liu et al., 2006). Specifically, activation of Gq-coupled α1 receptors triggered the PLC–IP3–Ca2+ pathway, leading to a reduction of NMDA receptor-mediated currents. On the other hand, Gi-coupled α2 receptors recruit PKA-ERK signaling and reduce NMDA receptor trafficking. Further, Roychowdhury et al confirmed that bath application of NE transiently curtailed electrically evoked α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPA) receptor-mediated EPSCs from layer II/III to layer V pyramidal neurons in rat mPFC (Roychowdhury et al., 2014). However, Luo et al. reported that in layer V/VI pyramidal neurons of the rat mPFC the α1 receptor agonist, phenylephrine, induced a significant enhancement of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) via presynaptic PKC-dependent pathway (Luo et al., 2014). Phenylephrine enhanced electrically evoked AMPA- and NMDA receptor-mediated EPSCs by pre- and post-synaptic PKC-dependent mechanisms (Luo et al., 2014). Yi and colleagues have shown that the α2A receptor agonist, guanfacine, significantly suppressed evoked AMPA-EPSCs in PFC pyramidal cells. Overall, the a2A receptor inhibition is mediated by the Gi-cAMP-PKA-PP1-calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)-AMPA receptor signaling pathway that can be blocked by different kinase antagonists at different levels (Yi et al., 2013). Conversely, under specific situations such as emotional arousal, NE recruits β receptors to activate the AC-cAMP-PKA-CaMKII pathway, leading to phosphorylation of GluR1 at sites critical for synaptic delivery of AMPARs and memory enhancement (Hu et al., 2007; Tenorio et al., 2010). In addition, activation of β receptors increases charge transfer and Ca2+ influx through NMDA receptors during excitatory synaptic transmission, probably by elevating cAMP-PKA activity (Raman et al., 1996). Conclusively, these results demonstrate a cell- and receptor-specific modulation of pyramidal neurons (Table 2, Figure 1), which must be taken into consideration when reading literature in the field in order to recognize the specific cell types and prefrontal layers examined in each circumstance.

Table 2.

Actions of NE and DA receptors in synaptic transmission in the PFC.

| Receptors | presynaptic action | postsynaptic action |

|---|---|---|

| α1 | ↑ GABA release (Terakado, 2014) | ↓ AMPAR(Roychowdhury et al., 2014) or ↑ AMPAR (Luo et al., 2014); ↓ NMDAR (Liu et al., 2006a) or ↑ NMDAR (Luo et al., 2014) |

| α2 | ↓ Glu release (Chiu et al., 2011) | ↓ AMPAR (Yi et al., 2013); ↓ MVIDAR (Liu et al., 2006a) |

| β | ↑ GABA release (Chiu et al., 2011); ↑ Glu release (Huang and Hsu, 2006) |

↑ AMPAR (Hu et al., 2007; Tenorio et al., 2010); ↑ NMDAR (Raman et al., 1996) |

| D1 | ↓ Glu release (Gao et al., 2001; Gao and Goldman-Rakic, 2003; Gonzalez-Islas and Hablitz, 2003; Seamans et al., 2001a) | ↓ AMPAR(Gao et al., 2001; Law-Tho et al., 1994; Seamans et al., 2001a) or ↑ AMPAR(Gonzalez-Islas and Hablitz, 2003; Onn et al., 2006); ↑ NMDAR(Flores-Hernandez et al., 2002; Law-Tho et al., 1994; Seamans et al., 2001a) |

| D2 | ↓ GABA release (Chiu et al., 2010; Seamans et al., 2001b; Xu and Yao, 2010) | ↓ AMPAR (Sun et al., 2005; Sun et al., 2008); ↓ NMDAR (Beazely et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2006b; Wang et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 1999) |

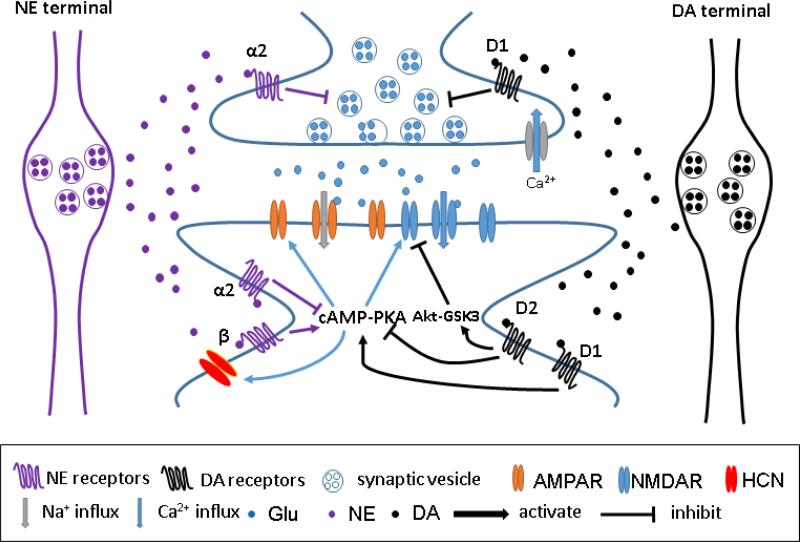

Figure 1.

Simplified modulatory effects of NE and DA on prefrontal cortical excitatory synapses. At presynaptic sites, NE and DA can inhibit glutamate release through activation of α2 receptors and D1 receptors, respectively, to control the opening of Ca2+ channels. At postsynaptic sites, both NE and DA can enhance AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated excitatory currents through β receptor- and D1 receptor-activated cAMP-PKA signaling pathways, respectively. In addition, by inhibiting cAMP-PKA signaling, NE and DA can decrease excitatory currents through activation of α2 receptors and D2 receptors, respectively. Activation of D2 receptors also blocks excitatory currents by recruiting Akt-GSK3 signaling.

In PFC cortical slices, DA, or a selective D1 agonist, decreased evoked AMPA receptor-mediated EPSP/Cs in layer V pyramidal neurons without altering the postsynaptic current induced by local application of AMPA (Gao et al., 2001; Law-Tho et al., 1994; Seamans et al., 2001a). This suggests that the D1-mediated reduction of AMPA-EPSP/Cs may occur presynaptically in the PFC. Accordingly, unitary EPSCs evoked by single axon inputs between layer V PFC pyramidal cell pairs were reduced by focally applied DA and D1 agonists in ferret PFC slices (Gao et al., 2001; Gao and Goldman-Rakic, 2003). However, this effect on paired-cell EPSPs may be species (Gonzalez-Burgos et al., 2005) or laminar specific, because in primate PFC slices, Urban et al. (Urban et al., 2002) found no such reduction in paired-cell recordings from layer III neurons. Nonetheless, they found that EPSCs evoked by a stimulating electrode were indeed reduced by DA via D1 receptors, consistent with the findings in the ferret paired recordings (Gao et al., 2001). Although most studies show a decrease in the evoked AMPA-EPSP/Cs by DA, two studies reported an increase (Gonzalez-Islas and Hablitz, 2003; Onn et al., 2006). The explanation for these contradictory results remains unclear, but it may be that the effects of D1 receptors on PFC neurons are input-specific (Urban et al., 2002) or synapse- and neuron-specific (Gao and Goldman-Rakic, 2003). Nevertheless, the immuno-electron microscope (EM) finding of target-specific D1 receptor immunoreactivity on axonal terminals that form asymmetric synapses on dendritic spines of glutamatergic pyramidal neurons, but not parvalbumin-containing interneurons, in the PFC has provided a structural basis for this hypothesis (Paspalas and Goldman-Rakic, 2005). The effect of DA on NMDA receptor-mediated excitatory transmission is dose-dependent, as low doses of DA and D1-like receptor activation potentiates NMDA responses (Flores-Hernandez et al., 2002; Hu et al., 2010; Law-Tho et al., 1994; Li et al., 2009; Seamans et al., 2001a), whereas high doses of DA and D2-like receptor activation leads to an inhibitory effect on NMDA receptor-mediated currents in the PFC (Beazely et al., 2006; Li et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2006b; Wang et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 1999).

3.2 NE vs. DA modulation of PFC inhibitory circuitry

Prefrontal cortical GABAergic interneurons are a highly heterogeneous cell population that forms complex functional networks and have key roles in information processing [reviewed in (DeFelipe et al., 2013; Le Magueresse and Monyer, 2013; Markram et al., 2004; Silberberg et al., 2005)]. Both NE and DA act as extrinsic modulators of neocortical interneuron function, and their effects can differentially affect subgroups of GABAergic cells that express different subfamilies of NE and DA receptors in a layer-specific manner in PFC [reviewed in (Bacci et al., 2005)]. The cortical GABAergic system consists of many different subclasses of interneurons, each having unique phenotypes defined by morphology, content of neuropeptide and calcium-binding protein (CB), as well as synaptic connectivity (Kawaguchi, 1995; Monyer and Markram, 2004). Morphologically, interneurons can be grouped by their structure and targets: basket cells preferentially target soma and proximal dendrites; double bouquet cells (and others such as Martinotti, Cajal–Retzius (CR) and bipolar cells) target dendrites and dendritic tufts; whereas chandelier cells exclusively target the axonal initial segment (AIS) of pyramidal neurons. Physiologically, interneurons can be divided into fast-spiking (FS) cells and several other non-FS cell types. Although non-FS interneurons are much more complicated, the parvalbumin (PV)-containing cells are exclusively FS interneurons and constitute the majority of the interneurons, including both perisomatic targeted basket and chandelier cells (Cauli et al., 1997). NE enhances the excitability of many types of GABAergic interneurons through up-regulation of the somatodendritic K+ channels via activation of α but not β receptors (Bennett et al., 1998; Kawaguchi and Shindou, 1998). However, a recent study has found that both β1 and β2 receptors are expressed, albeit differently, in a majority of GABAergic interneurons in mouse PFC, indicating a potential role of β receptors in modulating different cortical interneuron populations (Liu et al., 2014). Interestingly, NE triggers spike firing only in a subset of interneurons such as somatostatin (SST)-containing cells and cholecystokinin (CCK)-positive interneurons, but not in FS and late-spiking interneurons (Bennett et al., 1998). NE modulation of neuronal activity and synapses in the local prefrontal circuitry is synapse-specific. In particular, NE selectively depresses excitatory synaptic transmission in pyramidal (P)–FS connections but has no detectable effect on the excitatory synapses in P–P connections and the inhibitory synapses in FS–P connections. In this case, NE exerts distinctly different modulatory actions on identified synapses that target GABAergic interneurons but has no effect on those in the pyramidal neurons in the developing (juvenile) rat mPFC (Wang et al., 2013).

Early electrophysiological studies have indicated that DA can increase the frequency of spontaneous but not miniature IPSCs, suggesting that it enhances spiking activity of local GABAergic interneurons that target pyramidal neurons of PFC (Kroner et al., 2007; Seamans et al., 2001b; Zhou and Hablitz, 1999). FS basket and chandelier cells seem to be the predominant target for DA regulation of prefrontal cortical GABAergic interneurons (Gao and Goldman-Rakic, 2003; Gao et al., 2003; Gorelova et al., 2002; Towers and Hestrin, 2008; Zhou and Hablitz, 1999). Transgenic mice expressing the Cre recombinase in specific interneuron populations have allowed researchers to begin to identify cortical circuit elements that modulate complex PFC-dependent behaviors (Perova et al., 2015). For example, oxytocin modulates female socio-sexual behavior through a specific class of prefrontal cortical interneurons named somatostatin-positive cells that express the oxytocin receptor (Nakajima et al., 2014). Silencing oxytocin-expressing interneurons in the mPFC of female mice results in a loss of social interest in male mice, specifically during the sexually receptive phase of the estrous cycle. Therefore, targeting molecularly defined interneuron populations offers novel opportunities for understanding how extrinsic modulators such as NE and DA interactively regulate local prefrontal inhibitory circuitry.

DA regulation of inhibitory circuitry is also cell-type and synapse specific (Kroner et al., 2007). DA reduces perisomatic (FS interneuron to pyramidal cell), but not peridendritic (non-FS interneuron to pyramidal cell), IPSPs in neuronal pairs of the young ferret PFC (Gao et al., 2003). However, DA regulation of inhibition in the PFC seems to be more complicated as discussed below. In PFC neurons, Penit-Soria et al. first showed that DA increased spontaneous IPSPs in layer V/VI neurons, suggesting that DA could increase action potential dependent release of GABA (Penit-Soria et al., 1987). Subsequently, Law-Tho et al. reported that DA depressed IPSPs evoked by extracellular stimulation (Law-Tho et al., 1994). These studies suggested that DA might differentially modulate spontaneous and evoked IPSPs, in spite of the fact that both are largely dependent on the action potential-mediated release of GABA, and hence, theoretically, they should share common presynaptic release machineries (Gao et al., 2003; Gonzalez-Islas and Hablitz, 2001; Kroner et al., 2007; Seamans et al., 2001b; Zhou and Hablitz, 1999). The enhancement of sIPSCs by DA can be attributed to D1 receptors activation, leading to membrane depolarization and increases excitability of FS interneurons. On the other hand, the inhibitory effect of DA on evoked IPSCs largely depend on the indirect effect of FS interneurons on action potentials, specifically, activated FS interneurons project to the action potential initiation site (cell bodies and initial axon segments of pyramidal neurons) and decrease the action potential initiation threshold [for review see (Tritsch and Sabatini, 2012)]. In addition, DA also exhibited a biphasic modulation of IPSPs via combined D1 and D2 effects in both pre- and post-synaptic sites (Seamans et al., 2001b; Trantham-Davidson et al., 2004) (Figure 2) and a D4 receptor-mediated postsynaptic modulation (Graziane et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2002).

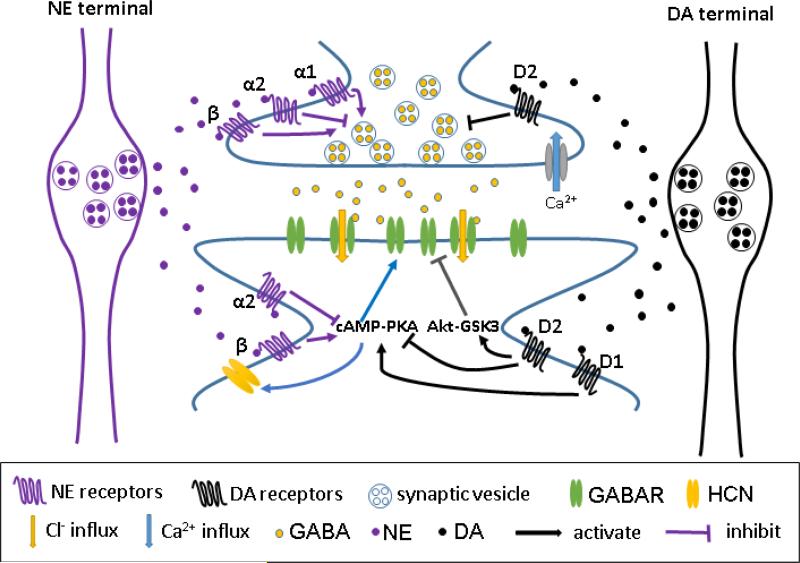

Figure 2.

Simplified summary of the modulatory effects of NE and DA on prefrontal cortical inhibitory synapses. At presynaptic sites, NE and DA can inhibit GABA release by activating α2 receptors and D2 receptors, respectively; whereas NE also enhance GABA release through activation of α1 or β adrenergic receptors. At postsynaptic sites, NE and DA increase GABAA receptor-mediated inhibitory current through β receptors and D1 receptors by activating camp-PKA signaling pathway. NE and DA also recruit α2 receptors and D2 receptors, respectively, leading to inhibition of cAMP-PKA signaling and thus decreased GABAA receptor-mediated inhibitory current. Activation of D2 receptors also triggers Akt-GSK3 signaling to decrease GABAA receptor-mediated inhibitory current.

There are only limited studies addressing the adrenergic modulation of cortical inhibition in sensorimotor (Bennett et al., 1998) and frontal cortex (Kawaguchi and Shindou, 1998). Recording from layer V pyramidal neurons of rat sensorimotor cortex, Bennett et al. found that epinephrine had mixed effects on evoked IPSCs, with enhancement, depression, or no effect at all, although depression was more commonly observed. In agreement, Kawaguchi and Shindou examined the effects of noradrenergic agonists on the activity of identified GABAergic interneurons in young rats and also reported either excitatory or inhibitory effects on cortical interneurons, depending on the cell type (Kawaguchi and Shindou, 1998). A recent study conducted by Roychowdhury and colleagues revealed that the effects of NE on electrically evoked GABAA receptor-mediated IPSCs were area- and layer-dependent, as NE enhanced the amplitude of evoked IPSCs in layer II/III pyramidal neurons from slices of temporal cortex and layer V in PFC, but depressed evoked inhibitory current in layer II/III neurons from PFC without affecting IPSCs in layer V neurons from temporal cortex (Roychowdhury et al., 2014). In spite of these findings, there has not been a full accounting of how NE regulates synaptic communication among individual pyramidal neurons and interneurons in the local prefrontal circuitry. To address this issue, we examined the effects of NE on monosynaptically connected and individually identified synaptic connections in layer V of mPFC slices by using quadruple patch clamp recordings conducted with DA application (Gao et al., 2001; Gao and Goldman-Rakic, 2003; Gao et al., 2003). The results indicated that NE selectively depresses excitatory synaptic transmission in pyramidal neuron–FS interneuron (P-NP) connections, but has no apparent effect on the excitatory synapses on the pyramidal neuron–pyramidal neuron connection (P-P) and on the inhibitory synapses in the FS interneuron–pyramidal neuron connections (NP-P) (Wang et al., 2013). Together with the action of DA on these connections (Gao et al., 2001; Gao and Goldman-Rakic, 2003; Gao et al., 2003), we propose a complementary effect of NE and DA on the synaptic communications between pyramidal neurons and FS interneurons in the local prefrontal circuitry as shown in Figure 3. However, it should be noted that these complementary observations were obtained from studies conducted in juvenile animals; whether these data can be replicated in adult animals, or can be used to interpret the behaviors in adult animals, remains to be tested. In addition, this schematic graph is a simplified model to show the potential complementary interaction between NE and DA without including the sophisticated dose-dependent action, as well as complex receptor and signaling pathways.

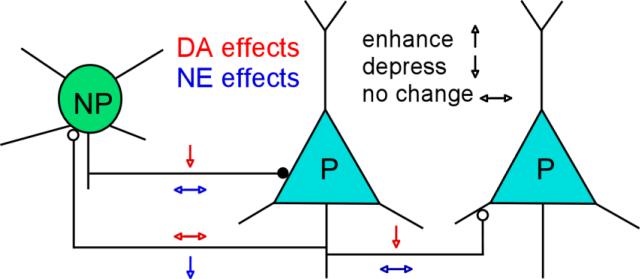

Figure 3.

Schematic model showing the complementary NE and DA effects on the synaptic transmission in PFC local circuitry. DA differentially affects the monosynaptic connections between P and NP, depending on the pre- and postsynaptic target neurons. In contrast, NE has opposite effects on P-P, P-NP and NP-P connections. Note: P, pyramidal neuron; NP, non-pyramidal neuron.

3.3 NE and DA modulation of neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity

Pharmacological and behavioral studies have shown that stimulation of α2 or D1 receptors within the PFC improves goal-directed performance [reviewed in (Arnsten, 2009)]. This improvement is accompanied by a selective increase in PFC neuronal activity during delay periods induced by NE and DA. Accordingly, it has been postulated that NE and DA act to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of PFC neuronal firing during working memory tasks by either increasing task-related activity (Wang et al., 2007), or decreasing background activity (Sawaguchi et al., 1990; Williams and Goldman-Rakic, 1995). Consistent with this theory, NE enhances delay-related neuronal firing of PFC pyramidal neurons (Dodt et al., 1991; Shi et al., 1997) in preferred directions by stimulating α2 receptors, whereas activation of D1 receptors weakens the neuron's response to non-preferred directions, probably via increased PKA-cAMP signaling (Vijayraghavan et al., 2007). However, high NE and DA levels cause recruitment of α1, β, and excessive D1 receptor activation during abnormal conditions such as stress, weakening neuronal firing and prefrontal functioning [reviewed in (Arnsten, 2009; Arnsten et al., 2012a; Ramos and Arnsten, 2007)].

The cellular mechanisms responsible for enhanced effects of NE and DA on working memory are largely unknown. Utilizing slice preparations from PFC, recent studies have found that the enhanced neuronal excitability caused by α2 receptor activation is mediated by the inhibition of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated cation (HCN) channels through either PLC–PKC signaling (Carr et al., 2007) or the cAMP-PKA pathway (Wang et al., 2007). Interestingly, blockage of these channels by α2 receptors produces a hyperpolarization of the resting membrane potential, but a significant enhancement in EPSP and recurrent network interactions, thus altering the gain in the transformation from pre- to postsynaptic activity (Barth et al., 2008). In other words, the net effect is the suppression of isolated excitatory inputs with enhancement of the response to a coherent burst of synaptic activity. Indeed, gene deletion of HCN1 decreases the intrinsic persistent firing. The membrane hyperpolarization caused by the deletion of HCN1 contributes to the reduction in persistent firing, and behavioral studies demonstrate that prefrontal HCN1 supports the resolution of proactive interference during working memory tasks (Thuault et al., 2013). The causal role of D1 receptor stimulation in reduction of PFC neuronal firing remains an open question, as activation of D1 receptors can have multiple actions in the PFC [reviewed in (Tritsch and Sabatini, 2012)]. It is proposed that D1 receptor stimulation can reduce presynaptic glutamate release (Gao et al., 2001) or alter opening of calcium channels (Yang and Seamans, 1996). Arnsten and colleagues have suggested that activation of D1 receptors may also reduce firing by increasing the open probability of HCN channels via cAMP signaling (Gamo et al., 2015). They have found the co-localization of HCN channels and D1 receptors on dendritic spines located in layer III of primate dorsolateral PFC, and D1-mediated increase in h-current. Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of D1 receptor activity on prefrontal neuronal firing and working memory performance are blocked by direct inhibition of HCN channels with blocker ZD7288. Thus, the cAMP-HCN channel signaling pathway represents a potential point for crosstalk between α2 and D1 receptors in regulating executive functions of the PFC. However, a fundamental question raised by these studies is the role that D2 and α1 receptors partake in this process, as both receptors are apparently involved in multiple psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and ADHD, and both remain under-studied in both normal and pathological conditions (Arnsten et al., 1999; Arnsten et al., 2012b; Wang et al., 2004).

Another important topic is how NE and DA individually or cooperatively affect long-term synaptic plasticity in the PFC circuitry. It has been proposed that lasting modifications of synapses in the PFC neurons underlie learned associations for central executive functions, such as rule learning and strategy shifting (Goto et al., 2010). The catecholamine transmitters have been shown to have a great influence on synaptic plasticity (Jay, 2003; Katsuki et al., 1997). The concurrent stimulation of LC adrenergic neurons in combination with the hippocampus increased hippo-PFC long-term potentiation (LTP). This effect was enhanced by administration of an α2 receptor antagonist, idazoxan, prior to high-frequency stimulation of the hippocampus, but impaired by administration of the α2 receptor agonist, clonidine. These data indicate that NE modulates hippo-PFC LTP and thus potentially affects PFC function (Lim et al., 2010). NE has also repeatedly been reported to enhance long-lasting modifications in synaptic efficacy in both the dentate gyrus and CA1 region of the hippocampus (Hopkins and Johnston, 1984; Stanton and Sarvey, 1985), likely via activation of β receptors (Hopkins and Johnston, 1988; Lin et al., 2003; Qian et al., 2012). Similarly, activation of β2 receptors in the PFC facilitates spike-timing-dependent long-term potentiation under physiological conditions with intact GABAergic inhibition and fear memory via cAMP-PKA signaling (Zhou et al., 2013), an effect reminiscent of D1 receptors that control the timing window for spike-timing dependent LTP induction in the PFC neurons (Xu and Yao, 2010). Intriguingly, stimulation of presynaptic D2 receptors in GABAergic interneurons can gate this spike timing-dependent plasticity of glutamatergic synapses through suppressing the activity of GABAergic inhibitory circuits (Xu and Yao, 2010). Similarly, NE enables the induction of associative LTP at thalamo-amygdala synapses. Specifically, NE suppresses GABAergic inhibition of projection neurons in the lateral amygdala and enables the induction of LTP at thalamo-amygdala synapses under conditions of intact GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition. These data indicate that the efficacy of inhibition due to NE signaling could result from a decrease in the excitability of local circuit interneurons (Tully et al., 2007). Together, these studies suggest that both NE and DA can affect long-term synaptic plasticity in the PFC or its connections, but whether and how these two neurotransmitters cooperate to regulate synaptic plasticity within the PFC local circuitry, synergistically or antagonistically, remains elusive.

4. Akt/GSk-3β signaling as a novel integrator of NE and DA interaction?

In addition to the aforementioned signaling pathways associated with both NE and DA modulation (Figure 4), glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3), a serine/threonine kinase that was originally identified as a regulator of glycogen metabolism (Scheid and Woodgett, 2001), appears to be a novel intracellular regulator for DA, especially hyperdopamine/D2 receptor-mediated signaling pathways and DA-associated behaviors (Beaulieu et al., 2007; Beaulieu et al., 2004; Beaulieu et al., 2005; Li and Gao, 2011). GSK-3 is known to regulate cell division, proliferation, differentiation, and adhesion (Bijur and Jope, 2001; Forde and Dale, 2007; Frame and Cohen, 2001). It is also associated with receptor trafficking (Li et al., 2009) and synaptic plasticity regulation (Forde and Dale, 2007; Peineau et al., 2008)(Xing et al, unpublished observation). GSK-3 consists of two isoforms, GSK3α and GSK3β, which unlike other cellular kinases, are constitutively active at basal conditions and are negatively regulated by upstream serine/threonine kinases such as Akt (also known as protein kinase B) through phosphorylation at serine residues. This novel signaling pathway is not dependent on canonical actions of G protein-mediated signaling and the cAMP/PKA/DARPP-32 pathway (Beaulieu et al., 2004). Beaulieu and colleagues revealed that activation of striatal D2 receptors by DA promotes β-arrestin 2, a scaffolding protein, binding with protein phosphatase-2A (PP2A) and Akt, thus forming a complex (Beaulieu et al., 2007; Beaulieu et al., 2004; Beaulieu et al., 2005). Formation of this complex leads to inactivation of Akt after the dephosphorylation of its regulatory threonine 308 (Thr-308) residue by PP2A (Beaulieu et al., 2005). Inactivated Akt ultimately contributes to the expression of DA-associated behaviors (Beaulieu et al., 2004) due to the loss of its regulation over GSK-3 activity, leading to GSK-3 hyperactivity. Although the role of GSK-3β in hyperdopamine-dependent behavior, synaptic transmission and plasticity is widely studied (Chen et al., 2007; Du et al.; Prickaerts et al., 2006; Roh et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2010), the identity of the downstream targets remains elusive. In the past several years, we have reported that GSK-3β signaling is required for both D2 receptor-mediated regulation of NMDA receptor and GABAA receptor function (Li et al., 2009; Li et al., 2012). Specifically, under hyperdopaminergic conditions such as those induced by in vitro administration of high-dose DA or in vivo injection of the DA reuptake inhibitor GBR12909, GSK-3β is involved in D2 receptor-mediated depression of NMDA receptors through inhibition of protein synthesis by disrupting the interaction between β–catenin and NR2B subunits (Li et al., 2009) (Figure 1). Similarly, GSK-3β signaling is involved in the high dose DA/D2 receptor-induced decrease in BIG2-dependent insertion and an increase in the dynamin-dependent internalization of GABAA receptors, which leads to suppression of inhibitory synaptic transmission (Li et al., 2012) (Figure 2).

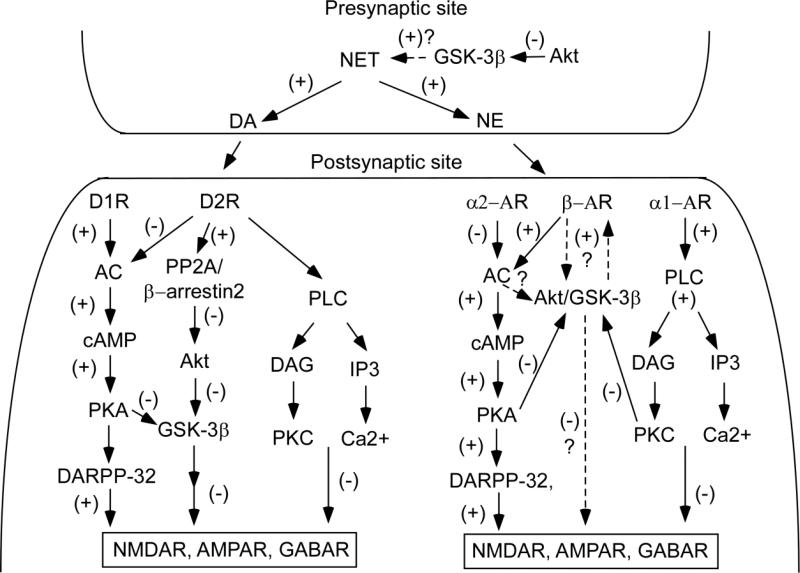

Figure 4.

Schematic graph shows the potential roles of Akt/GSK-3β signaling in DA and NE modulation of synaptic functions in the PFC. At presynaptic sites, activation of Akt down-regulates the expression of NET, which will result in an elevation of both DA and NE. At postsynaptic sites, activation of D1 receptors activates, but activation of D2 receptors inhibits, the cAMP/PKA/DARPP-32 signaling pathway to regulate both glutamatergic and GABAgeric receptor function. In addition, activation of D2 receptors also triggers β-arrestin2 binding with PP2A and Akt to form a complex. Within the complex, PP2A dephosphorylates and deactivates Akt, resulting in an activation of GSK-3β, which in turn down-regulates glutamatergic and GABAgeric receptor function. In addition to DA receptors, Akt/GSK-3β is probably also involved in β receptor-mediated regulation of synaptic transmission. Similarly, β receptors activate, but α2 receptors inhibit, the cAMP/PKA/DARPP-32 signaling pathway. In addition, activation of either α2 receptors or D2 receptors also stimulates PLC/PKC and PLC/IP3/Ca2 signaling, which will result in down-regulation of both glutamatergic and GABAgeric receptor function.

An immediate question raised by this novel hyperdopamine/D2 receptor-mediated GSK-3β signaling is whether Akt and GSK-3β are also involved in the regulation of neurotransmission mediated by NE. Recent studies have reported that Akt/GSK-3β is indeed implicated in NE-mediated signaling in different cell types, yet there is no single report in neurons. For example, in Rat-1 fibroblast cells treatment with insulin or phenylephrine (PE), an α1-adrenergic receptor agonist, induced Ser-9 phosphorylation of GSK-3β and inhibited GSK-3β activity (Ballou et al., 2001). However, PE-induced GSK-3β phosphorylation was also significantly reduced when Rat-1 cells were treated with a cell-permeable PKCzeta pseudo-substrate peptide inhibitor. These results suggest that the α1A-adrenergic receptor regulates GSK-3β through two signaling pathways: one inhibits insulin-induced GSK-3β phosphorylation by blocking insulin activation of Akt, while another stimulates Ser-9 phosphorylation of GSK-3β, probably via PKC (Ballou et al., 2001). Moreover, in rat epididymal fat cells, a β-adrenoceptor agonist, isoproterenol, was found to increase Akt and decrease GSK-3 activity, and this inhibition was neither sensitive to inhibition by the PI3K inhibitors (wortmannin or LY 294002), nor mimicked by addition of permeant cAMP analogues or forskolin to the cells (Moule et al., 1997). In colonic smooth muscle cells, NE also elevated the α1C subunit of Cav1.2b calcium channels that was found through β receptor-mediated PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β signaling (Li and Sarna, 2011). A large body of evidence also indicates that GSK-3β is a downstream target of β-adrenoreceptor-mediated signaling in cardiac myocytes (Daniels et al., 2012; Menon et al., 2007; Morisco et al., 2000; Singh et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011). Furthermore, in cultured spinal astrocytes, stimulation of β receptors induced inhibition of GSK-3β through Ser-9 phosphorylation (Morioka et al., 2014). In astroglial cells, two distinct pathways, PKA-CREB and Src-GSK-3β, were found to play crucial roles in NE-mediated regulation of Per1 expression (Morioka et al., 2014).

Based on these studies, and the fact that NE is a key neurotransmitter with a close functional interaction with DA in the brain, it is likely that Akt/GSk-3β signaling is also required for or involved in NE-associated function and behavior. However, there is still little information for the molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction of these two neurotransmitters. GSK-3β, which has been recognized as one of the main target of lithium, a commonly prescribed mood stabilizer for the treatment of bipolar disorder and depression (Johnson et al., 1971; Klein and Melton, 1996; O'Brien et al., 2004) is highly implicated in the pathology of schizophrenia (Emamian et al., 2004; Emamian, 2012; Mao et al., 2009). Indeed, GSK-3β is inhibited by antipsychotics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers (Gould and Manji, 2005; Sutton and Rushlow), all of which directly or indirectly target D2 receptors, but also the entire monoamine spectrum, including DA, NE and serotonin. Therefore, Akt/GSK-3β signaling likely serves as an important intracellular hub for the effects and interactions induced by NE and DA. A large body of evidence has indicated the direct and indirect interaction of α1 receptors with either D1 receptors (Blanc et al., 1994; Darracq et al., 1998; Mitrano et al., 2014; Taghzouti et al., 1988; Tassin, 1998; Vezina et al., 1991) or D2 receptors (Gioanni et al., 1998) in neocortex and striatum, and these interactions might co-regulate PLC signaling. There is also evidence of cross-talk between α2 and D2 receptors via DARPP-32 signaling, indicating that cAMP/PKA is a common integrator for NE and DA (Hara et al., 2010).

Similarly, it has been reported that D2 and β1 receptors co-localized within prefrontal cortical neurons, providing a basis for the functional crosstalk between NE and DA (Montezinho et al., 2006). Interestingly, their crosstalk is affected by lithium, which attenuates the inhibitory effect of D2 receptors on β1 receptor-stimulated cAMP production, thus indicating that GSK-3β is involved in regulating the interaction of NE and DA (Masana et al., 1991; Montezinho et al., 2006). Furthermore, lithium can suppress β1 receptor-induced enhancement of cAMP levels (Masana et al., 1991; Montezinho et al., 2006). Therefore, in addition to indirectly regulating β1 receptors via D2/GSK-3β signaling, GSK-3β might directly up-regulate the β1 receptor function, or act as an intermediate downstream of β1 receptors. Moreover, cortical NE transporter (NET) seems to be responsible for the re-uptake of both NE and DA in the PFC, which decides the tone of NE and DA. Evidence has shown that Akt acts as a modulator to regulate noradrenergic tone via NET in both the hippocampus (Robertson et al., 2010) and cortex (Siuta et al., 2010), indicating that Akt signaling contributes to the regulation of NE and DA concentrations in the synaptic cleft as well. Therefore, it is likely that Akt/GSK-3β signaling plays a crucial role as an integrator of NE and DA signaling via both pre-synaptic and post-synaptic mechanisms, ultimately converging in order to regulate PFC-dependent functions and behaviors. In Figure 4, we summarize the possible involvement of Akt/GSK3β signaling in DA and NE modulation of synaptic functions within the PFC; although some roles remain to be explored and are speculations, particularly those related to NE signaling, we have included all possible pathways for future discussions.

5. Catecholaminergic systems exhibit region- and cell-specific changes during cortical development

Multiple lines of evidence have suggested that the monoaminergic systems produce brain region-specific alterations during puberty and adolescent periods and that these alterations are crucial for the onset of many psychiatric disorders (Goto and Grace, 2007; Lewis, 1992). During postnatal development, especially juvenile and adolescent periods, several brain regions are still developing and environmental risk factors such as drugs or stress could target vulnerable immature systems like NE and DA neurons, which could then translate into a psychiatric disorder associated with PFC dysfunction (Andersen, 2002; Arnsten et al., 2015b; Niwa et al., 2013; Spear, 2000; Thompson et al., 2004). For example, it has been shown that aversive postnatal experiences impairs sensitivity to natural rewards and increases susceptibility to negative events in adulthood (Ventura et al., 2013). A single, chronic stressful event can alter LC-NE function (George et al., 2013) and early adolescence has been identified as a critical window during which social stress is able to strongly affect behavior and brain norepinephrine activity (Bingham et al., 2011). These findings demonstrate that an unstable maternal environment impairs the natural propensity to seek pleasurable sources of reward, enhances sensitivity to negative events in adult life, blunts prefrontal DA outflow, and negatively modulates NE release depending on the exposure to rewarding or aversive stimuli. Therefore, it is important to understand how interaction between NE and DA changes throughout development.

DA immunoreactivity revealed exponential growth of DA neurons until postnatal day 30 (P30) in rats, followed by a slower growth until P90. DA innervation in the PFC achieves maturity at about P90 in rodents (Dawirs et al., 1993). Similarly, pyramidal cells and non-pyramidal interneurons are differentially innervated by catecholaminergic fibers and this pattern exhibits distinct cell-type specific alterations during development in the primate PFC (Lambe et al., 2000). Moreover, D1 receptors appear in the rat mPFC at P7, increase 3-fold by P14 to P21, and then decline in P28 to P42 (Leslie et al., 1991). Similarly, the gene expression of D1 is higher in adolescent and young adult rats. The peak in D1 mRNA levels around adolescence may be of particular relevance to neuropsychiatric disorders such as ADHD and schizophrenia in which symptoms manifest during the same developmental period. Indeed, the postnatal maturation of DA innervation in the PFC is sensitive to a single dose of methamphetamine treatment (Dawirs et al., 1994), and both D1-NMDA interaction (Tseng and O'Donnell, 2005) and DA modulation of prefrontal cortical interneurons (Tseng and O'Donnell, 2007) exhibited dramatic changes during adolescence. In contrast, NE innervation of rat cerebral cortex exhibits a different developmental pattern compared to DA. NE fibers are present at birth and gradually innervate all cortical layers during subsequent weeks. The adult pattern of distribution is largely attained by P12 to 21 (Latsari et al., 2002; Levitt and Moore, 1979).

Because of the differential distributions of adrenergic and dopaminergic receptors and subtypes on pyramidal cells and non-pyramidal GABAergic interneurons in the PFC, it would be interesting to know how NE and DA would cooperatively modulate excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmissions in the immature versus mature PFC circuitry. Do these two transmitters have synergistic or antagonistic effects when they are proportionally increased or decreased, or changed in different proportions within the PFC? Is there any crosstalk between the receptor-mediated signaling pathways activated by these two transmitters when both of them are simultaneously released? In a previous study, Marek and Aghajanian reported that the DA-induced increase of EPSC frequency on pyramidal neurons could be blocked by application of α1 receptor antagonist prazosin (Marek and Aghajanian, 1999). This study clearly demonstrate the existence of a crosstalk within catecholaminergic systems between the two neurotransmitters and their heterogeneous receptors. These observations suggest that, as the NE and DA systems mature, NE and/or DA may engage in interactions with other cortical neurotransmitter systems and collectively these two systems may exert their combined effects on target cells within the PFC.

6. Future perspectives

As discussed above, most studies focused on modulation of synaptic function in the PFC by NE or DA were conducted separately in order to elucidate the mechanisms associated with each neurotransmitter. Yet, NE and DA systems are intertwined within the PFC circuitry not only with their shared reuptake transporter NET, co-localized receptors, and common signaling pathways, but also with co-release in response to various stimulations and even normal PFC-dependent functions. Unfortunately, the research in this regard is very limited and the scope of how NE and DA systems interact to regulate PFC function remains to be characterized. Many questions remain, but we have critically evaluated topics that should be prioritized and addressed in future experiments in order to better understand how functional interaction of NE and DA regulates PFC function.

It is widely accepted that both NE and DA are mainly taken up by NET in the PFC because of the limited expression of DAT in this brain region (Sesack et al., 1998) and the relatively high affinity of DA for NET compared to DAT (Giros et al., 1994; Gu et al., 1994). Thus, theoretically, selective NE reuptake inhibitors could be more effective than selective DA reuptake inhibitors or in general NE/DA reuptake inhibitors in terms of their effects on PFC-dependent cognition or on treatment of PFC-dependent diseases such as ADHD. However, this assumption may not be correct. Berridge and colleagues first reported that methylphenidate, a psychostimulant that selectively inhibits both NE and DA reuptake, preferentially increased catecholamine neurotransmission within the PFC at low doses that enhanced cognitive function (Berridge et al., 2006). This finding was further confirmed by direct administration of methylphenidate within the PFC (Spencer et al., 2012). However, a follow-up study indicated that AHN 2-005, a compound with DAT selectivity, significantly increased extracellular levels of both NE and DA in the PFC at a cognition-enhancing dose that lacked locomotor activating effects, although AHN 2-005 produced a larger increase in extracellular DA in the nucleus accumbens (Schmeichel et al., 2013). Collectively, these studies provide a strong rationale for future research focused on the neural mechanisms contributing to the cognition-enhancing actions and the potential clinical utility of AHN 2-005 and other compounds that target DAT, NET or both [also see reviews (Schmeichel and Berridge, 2013; Spencer et al., 2015)]. In addition, the contribution of DAT and NET to the uptake of both catecholamines across development should be addressed. Specifically, is PFC DAT expression low at birth, or does the expression of DAT progressively decreased during postnatal development. Since methylphenidate induces opposite effects on neuronal activity, synaptic transmission, and plasticity in the juvenile versus adult animal PFC in a clinical-relevant dose for adult (Urban et al., 2012; Urban et al., 2013), it is important to explore the developmental expression and function of NET and DAT in the PFC.

In addition, Akt/GSK-3β appears to be a novel signaling pathway for hyperdopaminergic action that is highly involved in both normal and abnormal PFC-dependent functions. However, to our knowledge there are no publications on whether this signaling pathway also mediates NE modulation of synaptic function in the PFC or neuronal function in the brain. Since NE and DA act like twins, i.e., neither NE nor DA can act alone without affecting the other system under various conditions (Kandel, 2013), it is hard to believe that Akt/GSK-3β would not be activated when NE concentration is significantly increased under a hyper-norepinephrine condition (e.g., cocaine addiction, methylphenidate treatment, or extreme stress). Furthermore, how these two protein kinases coordinate their activity in response to NE and DA stimulation over a range of concentrations is worthwhile to explore.

In terms of NE and DA actions and interactions in the PFC, there is more than meets the eye, especially in regard to the developmental, regional, and laminar differences of NE and DA receptor profile expressions within the PFC (Chandler et al., 2014b). The key requirement here is a spatially and temporally far better view of the activity of noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurons and their release in the target prefrontal cortical area. Discovery of the diverse innervation pattern of the PFC by subsets of NE and DA neurons is certainly an important conceptual advancement in our understanding of these two systems (Chandler and Waterhouse, 2012; Chandler et al., 2013; Chandler et al., 2014a; Lammel et al., 2008; Lammel et al., 2012). Many questions still remain as listed in our recent review (Chandler et al., 2014b). Furthermore, exploration of the properties of specified groups of LC- and VTA-cortical projection neurons could help determine the susceptibility of these organizations to pharmacological, environmental, or genetic insults that manifest in symptoms of neuropsychiatric or neurodegenerative diseases associated with noradrenergic and dopaminergic dysfunctions.

Efforts on these topics will provide novel insights into their collective impact on PFC-dependent functions and behaviors. In this case, new technologies based on transgenic Cre-driver mouse lines, along with viral vector-based optogenetic and pharmacogenetic approaches will likely elucidate much more complex microcircuits and provide more definitive answers as to the roles of genetically defined cell-type and synaptic-specific roles in PFC functioning (Lammel et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2008; Oh et al., 2014). Furthermore, these studies will enhance drug development for the treatment of many NE and NE/DA-related neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Highlights.

The role NE and DA play in regulation of prefrontal synaptic function

NE and DA are essential for PFC functioning

NE and DA modulation of synaptic transmission in the PFC circuitry

Akt/GSk-3β signaling as a novel integrator of NE and DA interaction?

Perspectives and critical topics for future studies

Acknowledgment

This study is supported by NIH R01MH085666 to WJG and NIH R03MH101578 to YCL. We thank Dr. Kimberly Urban, Mr. Zachary Brodnik, and Ms. Sarah Monaco for commenting on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AC

adenylate cyclase

- ADHD

attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Akt

protein kinase B

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- cAMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- DA

dopamine

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DARPP-32

dopamine- and cAMP-regulated phosphoprotein, Mr 32 kDa

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic current

- EPSP

excitatory postsynaptic potential

- FS

fast-spiking

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- GSK-3

glycogen synthase kinase-3

- IP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- LC

locus coeruleus

- LTP

long-term potentiation

- mEPSCs

miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- NE

norepinephrine or noradrenaline

- NET

norepinephrine transporter

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartic acid

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PLC

Phospholipase C

- PP2A

protein phosphatase-2A

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- PV

parvalbumin

- RGS

regulators of G protein signaling

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors claim no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- Agster KL, et al. Evidence for a regional specificity in the density and distribution of noradrenergic varicosities in rat cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:2195–207. doi: 10.1002/cne.23270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL. Changes in the second messenger cyclic AMP during development may underlie motoric symptoms in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Behav Brain Res. 2002;130:197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, et al. Perikaryal and synaptic localization of alpha 2A-adrenergic receptor-like immunoreactivity. Brain Res. 1994;650:181–204. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, et al. Cellular and subcellular sites for noradrenergic action in the monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex as revealed by the immunocytochemical localization of noradrenergic receptors and axons. Cereb Cortex. 1998a;8:269–77. doi: 10.1093/cercor/8.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, Venkatesan C, Kurose H. Noradrenergic modulation of the prefrontal cortex as revealed by electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. Adv Pharmacol. 1998b;42:777–80. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60862-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Goldman-Rakic PS. Noise stress impairs prefrontal cortical cognitive function in monkeys: evidence for a hyperdopaminergic mechanism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:362–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.4.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, et al. Alpha-1 noradrenergic receptor stimulation impairs prefrontal cortical cognitive function. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:26–31. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Stress impairs prefrontal cortical function in rats and monkeys: role of dopamine D1 and norepinephrine alpha-1 receptor mechanisms. Prog Brain Res. 2000;126:183–92. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)26014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Adrenergic targets for the treatment of cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;174:25–31. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1724-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Li BM. Neurobiology of executive functions: catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical functions. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1377–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:410–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF. Catecholamine influences on dorsolateral prefrontal cortical networks. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:e89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Pliszka SR. Catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical function: relevance to treatment of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and related disorders. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99:211–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Wang MJ, Paspalas CD. Neuromodulation of thought: flexibilities and vulnerabilities in prefrontal cortical network synapses. Neuron. 2012a;76:223–39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Jin LE. Molecular influences on working memory circuits in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2014;122:211–31. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420170-5.00008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AF, Wang M, Paspalas CD. Dopamine's Actions in Primate Prefrontal Cortex: Challenges for Treating Cognitive Disorders. Pharmacol Rev. 2015a;67:681–96. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.010512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten Amy F.T., Wang Min J., Paspalas Constantinos D. Neuromodulation of thought: flexibilities and vulnerabilities in prefrontal cortical network synapses. Neuron. 2012b;76:223–239. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AFT, et al. The effects of stress exposure on prefrontal cortex: Translating basic research into successful treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder. Neurobiology of Stress. 2015b;1:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Cohen JD. An integrative theory of locus coeruleus-norepinephrine function: adaptive gain and optimal performance. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:403–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacci A, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Modulation of neocortical interneurons: extrinsic influences and exercises in self-control. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:602–10. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballou LM, et al. Dual regulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta by the alpha1A-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:40910–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth AM, et al. Alpha2-adrenergic receptors modify dendritic spike generation via HCN channels in the prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:394–401. doi: 10.1152/jn.00943.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu J-M, et al. Regulation of Akt signaling by D2 and D3 dopamine receptors in vivo. The Journal of neuroscience. 2007;27:881–885. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5074-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, et al. Lithium antagonizes dopamine-dependent behaviors mediated by an AKT/glycogen synthase kinase 3 signaling cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5099–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307921101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, et al. An Akt/beta-arrestin 2/PP2A signaling complex mediates dopaminergic neurotransmission and behavior. Cell. 2005;122:261–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM, Gainetdinov RR. The physiology, signaling, and pharmacology of dopamine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:182–217. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BD, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Adrenergic modulation of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in rat sensorimotor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:937–46. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergson C, et al. Regional, cellular, and subcellular variations in the distribution of D1 and D5 dopamine receptors in primate brain. J Neurosci. 1995;15:7821–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-07821.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;42:33–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, et al. Methylphenidate preferentially increases catecholamine neurotransmission within the prefrontal cortex at low doses that enhance cognitive function. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1111–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge CW, Arnsten AF. Psychostimulants and motivated behavior: arousal and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:1976–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigham MH, Lidow MS. Adrenergic and serotonergic receptors in aged monkey neocortex. Neurobiol Aging. 1995;16:91–104. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)80012-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijur GN, Jope RS. Proapoptotic stimuli induce nuclear accumulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β*. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:37436–37442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105725200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham B, et al. Early Adolescence as a Critical Window During Which Social Stress Distinctly Alters Behavior and Brain Norepinephrine Activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:896–909. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum SG, et al. Protein kinase C overactivity impairs prefrontal cortical regulation of working memory. Science. 2004;306:882–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G, et al. Blockade of prefronto-cortical alpha 1-adrenergic receptors prevents locomotor hyperactivity induced by subcortical D-amphetamine injection. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:293–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan AR, Arnsten AF. Neuronal mechanisms underlying attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: the influence of arousal on prefrontal cortical function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:236–45. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brozoski TJ, et al. Cognitive deficit caused by regional depletion of dopamine in prefrontal cortex of rhesus monkey. Science. 1979;205:929–32. doi: 10.1126/science.112679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai JX, Arnsten AF. Dose-dependent effects of the dopamine D1 receptor agonists A77636 or SKF81297 on spatial working memory in aged monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:183–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr DB, et al. alpha2-Noradrenergic receptors activation enhances excitability and synaptic integration in rat prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons via inhibition of HCN currents. J Physiol. 2007;584:437–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.141671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castner SA, Williams GV. Tuning the engine of cognition: a focus on NMDA/D1 receptor interactions in prefrontal cortex. Brain Cogn. 2007;63:94–122. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauli B, et al. Molecular and physiological diversity of cortical nonpyramidal cells. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3894–906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03894.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler D, Waterhouse BD. Evidence for broad versus segregated projections from cholinergic and noradrenergic nuclei to functionally and anatomically discrete subregions of prefrontal cortex. Front Behav Neurosci. 2012;6:20. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2012.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler DJ, Lamperski CS, Waterhouse BD. Identification and distribution of projections from monoaminergic and cholinergic nuclei to functionally differentiated subregions of prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 2013;1522:38–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler DJ, Gao WJ, Waterhouse BD. Heterogeneous organization of the locus coeruleus projections to prefrontal and motor cortices. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014a;111:6816–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320827111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler DJ, Waterhouse BD, Gao W-J. New Perspectives on Catecholaminergic Regulation of Executive Circuits: Evidence for Independent Modulation of Prefrontal Functions by Midbrain Dopaminergic and Noradrenergic Neurons. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 2014b;8:53. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 regulates N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel trafficking and function in cortical neurons. Molecular pharmacology. 2007;72:40–51. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark KL, Noudoost B. The role of prefrontal catecholamines in attention and working memory. Front Neural Circuits. 2014;8:33. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2014.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels CR, et al. Exogenous ubiquitin modulates chronic beta-adrenergic receptor-stimulated myocardial remodeling: role in Akt activity and matrix metalloproteinase expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H1459–68. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00401.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darracq L, et al. Importance of the noradrenaline-dopamine coupling in the locomotor activating effects of D-amphetamine. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2729–39. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-07-02729.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawirs RR, Teuchert-Noodt G, Czaniera R. Maturation of the dopamine innervation during postnatal development of the prefrontal cortex in gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus). A quantitative immunocytochemical study. J Hirnforsch. 1993;34:281–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawirs RR, Teuchert-Noodt G, Czaniera R. The postnatal maturation of dopamine innervation in the prefrontal cortex of gerbils (Meriones unguiculatus) is sensitive to an early single dose of methamphetamine. A quantitative immunocytochemical study. J Hirnforsch. 1994;35:195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, et al. New insights into the classification and nomenclature of cortical GABAergic interneurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14:202–216. doi: 10.1038/nrn3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodt HU, Pawelzik H, Zieglgansberger W. Actions of noradrenaline on neocortical neurons in vitro. Brain Res. 1991;545:307–11. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91303-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, et al. A kinesin signaling complex mediates the ability of GSK-3β to affect mood-associated behaviors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:11573–11578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913138107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamian ES, et al. Convergent evidence for impaired AKT1-GSK3beta signaling in schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:131–7. doi: 10.1038/ng1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamian ES. AKT/GSK3 signaling pathway and schizophrenia. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:33. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Hernandez J, et al. Dopamine enhancement of NMDA currents in dissociated medium-sized striatal neurons: role of D1 receptors and DARPP-32. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:3010–20. doi: 10.1152/jn.00361.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forde J.a., Dale TC. Glycogen synthase kinase 3: a key regulator of cellular fate. Cellular and molecular life sciences. 2007;64:1930–1944. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frame S, Cohen P. GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem. J. 2001;359:1–16. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franowicz JS, et al. Mutation of the alpha2A-adrenoceptor impairs working memory performance and annuls cognitive enhancement by guanfacine. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8771–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08771.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamo NJ, et al. Stress impairs prefrontal cortical function via D1 dopamine receptor interactions with hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Biol Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]