Abstract

Purpose

Although breast cancer survivors’ lifestyle choices affect their subsequent health, a majority do not engage in healthy behaviors. Because treatment end is a “teachable moment” for potentially altering lifestyle change for breast cancer survivors, we developed and tested two mail-based interventions for women who recently completed primary treatment.

Methods

173 survivors were randomly assigned to: 1) targeting the teachable moment (TTMI, n = 57); 2) standard lifestyle management (SLM, n = 58); or 3) usual care (UC, n = 58) control group. Participants who were assigned to TTMI and SLM received relevant treatment materials biweekly for 4 months. Participants were assessed at baseline (T1; before randomization), post-treatment (T2; 4 month), and follow-up (T3; 7 month). Fruit and vegetable (F/V) intake, fat intake, and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) were assessed.

Results

Results showed promise for these mail-based interventions for changes in health behaviors: Survivors in TTMI (+.47) and SLM (+.45) reported increased F/V intake, whereas those in UC (−.1) reported decreased F/V intake from T1 to T2. Changes in minutes of MVPA from T1 to T2 were higher in SLM than UC and marginally higher in TTMI than UC. However, these differences were due to decreased MVPA in UC rather than increased MVPA in the intervention groups. There were no group differences regarding fat intake. Survivors reported high satisfaction and preference for mail-based interventions, supporting feasibility.

Conclusions

Mail-based lifestyle interventions for breast cancer survivors may benefit F/V intake and physical activity. Further testing and optimizing of these interventions is warranted.

Keywords: mail-based intervention, physical activity, dietary behaviors, teachable moment

Although survival rates have continued to increase, breast cancer (BC) survivors remain at heightened risk for recurrence, second primary cancers, and many other serious health conditions (see [1]). BC survivors’ lifestyles can impact their health and well-being: Following BC, exercise is related to reduced fatigue and increased functional ability, immune capacity, and quality of life along with improved survival and reduced recurrence risk [2-6] while better diet is linked to lower recurrence rates and lengthened survival and reduced risk of second cancers [7-9].

However, according to the National Health Interview Survey, 70% of BC survivors are inactive [10], 58% get five or fewer daily servings of fruits and vegetables (F/V); 56% get more than 30% of their calories from fat, and 54% are overweight or obese [11], none statistically different from the general population of similar-aged women. Because most BC survivors do not meet American Cancer Society [12] guidelines for healthy behaviors, there is tremendous room for improvement.

The teachable moment refers to windows of time following health events when people are more open to making lifestyle changes [13]. For cancer survivors, treatment end is a critical teachable moment when they are especially amenable to implementing changes [13]. Indeed, many of the most successful lifestyle interventions have been conducted after treatment ends [14-17]. Among the most promising interventions are FRESH START [14], which included a workbook and mail-based newsletters, and Project LEAD [18], which included a workbook and biweekly telephone counseling. In addition, there were more intensive interventions such as WHEL (the Women's Healthy Eating and Living) randomized trial (providing counseling calls, cooking classes, and newsletters across four years; see [19]) and WINS (the Women's Intervention Nutrition Study) comprised of eight in-person counseling along with subsequent dietician contacts every 3 month; see [7]). Regardless of intervention methods and duration/intensity, most interventions focus on standard components of basic lifestyle change programs (e.g., for those with diabetes or heart disease) including self-efficacy, readiness for change, goal setting, and behavioral monitoring. Such interventions are effective in helping survivors make positive health behavior changes (e.g., [14]).

However, current lifestyle interventions have several limitations: (1) Virtually none have targeted the specific issues and needs of survivors, but instead used materials developed and appropriate for the general population. Yet BC survivors have unique physical (e.g., concerns about fatigue, lymphedema, mobility problems) and psychosocial (e.g., fears of recurrence, treatment and test-related anxiety) issues; (2) Few interventions have addressed survivorship concerns that can impede positive changes [19] or explicitly focused on teachable moments; (3) Most current BC survivor interventions (e.g., face-to-face, telephone-based), are clinic-based or require intensive staff time and effort [20], yet most cancer care is given in community settings, which often lack the resources to conduct intensive interventions; (4) They do not address barriers such as time, energy, and transportation required by intensive or on-site interventions.

Given these limitations, we developed two mail-based interventions for BC survivors who recently completed primary treatment: (1) Standardized Lifestyle Management (SLM), similar in content to FRESH START and (2) Targeting the Teachable Moment Intervention (TTMI), which incorporates the teachable moment concept, survivorship and psychosocial issues tailored for BC survivors. Unlike FRESH START, however, we delivered mail-based materials more frequently (every 2 weeks vs. every 6 weeks) and did not deliver tailored newsletters but rather materials with which participants would interact, aiming to develop skills and create awareness and self-reflection. Further, we conducted the intervention across a shorter period of time (4 months vs. FRESH START's 10) and provided the change materials for diet and exercise concomitantly rather than sequentially, as did FRESH START.

This study examined whether these mail-based interventions would increase physical activity and healthy diet over time compared with the control condition. We hypothesized that participants receiving either TTMI or SLM would improve health behaviors from baseline to post-treatment more than would those in the usual care (UC) condition. We also expected that health behaviors in TTMI and SLM would be higher from post-intervention to the second follow-up compared to their UC counterparts. We did not make specific hypotheses about comparative effects of TTMI versus SLM. Finally, we examined intervention feasibility.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We planned to recruit 225 participants to provide sufficient power (1-β=.94) for omnibus tests and comparisons of each treatment group to UC (1-β=.88 and .79, respectively) at α=.05. However, we were able to recruit only 173 survivors during our funding period. Mean age was 56.40 years. The majority was White, married or in a long-term partnered relationship, and had at least 4-year college degree. See Table 2 for detailed information.

Table 2.

Participants Characteristics

| Group |

Difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTMI | SLM | UC control | ||

| Age (SD) | 55.73 (10.91) | 57.74 (10.70) | 55.72 (10.92) | F(2, 169) = .67 |

| Race/Ethnicity n (%) | χ2(8) = 4.55 | |||

| White | 54 (94.7) | 56 (96.6) | 53 (93.0) | |

| African American | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.5) | |

| Hispanics | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (1.8) | |

| Other | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Marital status n (%) | χ2(2) = .93 | |||

| Single, never married | 3 (5.4) | 1 (1.7) | 3 (5.3) | |

| Divorced/separated | 10 (17.9) | 10 (17.2) | 11 (19.3) | |

| Widowed | 2 (3.6) | 6 (10.3) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Married/other long-term partnered relationship | 41 (73.2) | 41 (70.7) | 42 (73.7) | |

| Education n (%) | χ2(14) = 11.16 | |||

| Less than high school | 0 | 1 (1.7) | 0 | |

| High school/GED | 6 (10.5) | 7 (12.1) | 8 (14.0) | |

| Some college | 11 (19.3) | 9 (15.5) | 8 (14.0) | |

| 2-year college degree (Associate's) | 7 (12.3) | 4 (6.9) | 5 (8.8) | |

| 4-year college degree (BA/BS) | 17 (29.8) | 23 (39.7) | 20 (35.1) | |

| Graduate degree (MA, PhD) | 16 (28.1) | 13 (22.4) | 12 (21.0) | |

| Professional degree (MD, JD) | 0 | 1 (1.7) | 4 (7.0) | |

| Household income n (%) | χ2(18) = 13.73 | |||

| < $20,000 | 5 (9.1) | 2 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) | |

| $20-40,000 | 2 (3.6) | 3 (5.4) | 6 (11.0) | |

| $40-60,000 | 5 (9.1) | 13 (23.6) | 9 (16.4) | |

| $60-80,000 | 10 (18.2) | 6 (10.9) | 9 (16.4) | |

| >$80,0000 | 33 (60.0) | 31 (56.4) | 30 (54.5) | |

| Prior diagnosis | χ2(2) = 7.99* | |||

| No | 50 (87.7) | 39 (67.2) | 48 (82.8) | |

| Yes | 7 (12.3) | 19 (32.8) | 10 (17.2) | |

| Current cancer treatment | χ2(2) = 1.58 | |||

| No | 35 (64.8) | 38 (70.4) | 33 (58.9) | |

| Yes | 19 (35.2) | 16 (29.6) | 23 (41.1) | |

Note.

p < .05

We initially targeted women who had completed primary treatment for invasive BC (no inflammatory or metastatic disease) at stage I or II within the past 3 months. However, due to difficulties in recruitment, we expanded eligibility criteria to stage 0-II and diagnosed in the past 1.5 years. Further, we included only survivors able to read/write English, not participating in other health behavior research, and without apparent serious mental disturbance.

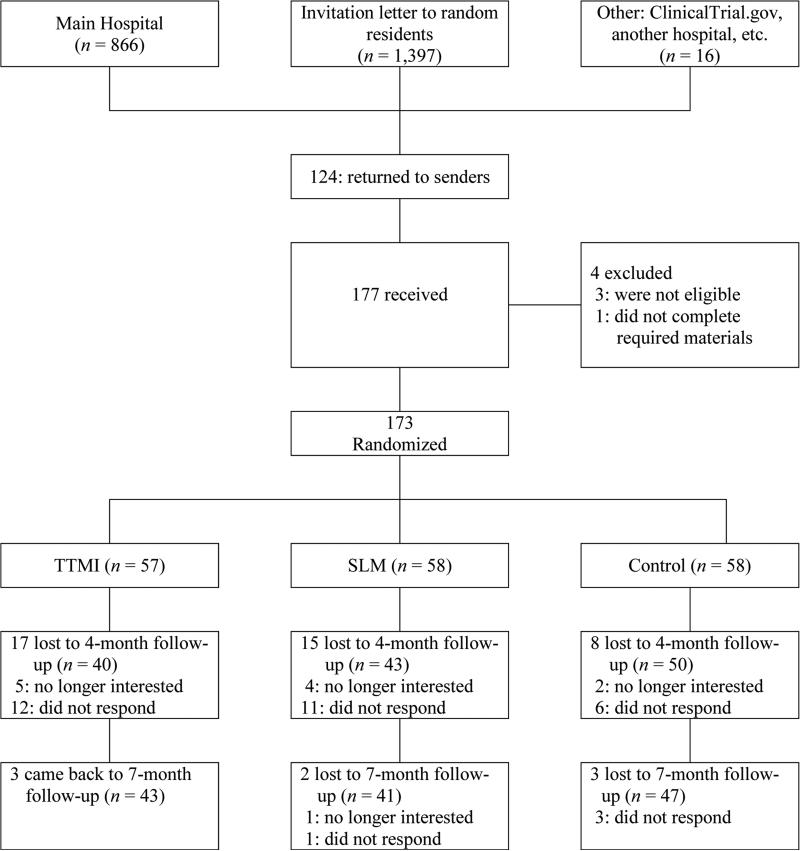

Recruitment was conducted from September, 2011 through October, 2013. The majority of participants (84.97%) were recruited through a regional cancer center in the Northeastern US. Eligible participants were identified by the hospital registry and a recruitment packet was mailed to them. Participants were also recruited through ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT01819324) and another regional hospital (7.52%) as well as mailings sent to randomly selected community residents (women aged 40-60) (6.36%). Finally, we distributed flyers to local radiology clinics, community locations and websites for BC foundations and support groups (1.15%). We present participant flow in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow

Participants completed baseline questionnaires (T1) and then were randomly assigned (using a blocked design to ensure equal numbers of participants in each group) to one of three groups: 1) TTMI (n=57), 2) SLM (n=58), and 3) UC (n=58). Participants assigned to TTMI or SLM were unaware of their group assignment; those assigned to UC were notified that they were assigned to that group and would receive treatment materials after completing the T3 assessment. Participants in TTMI and SLM received a mail-based program of biweekly treatment materials for four months (i.e., a total of 8 mailings). Post-assessments took place shortly after last mailing (T2) and follow-up (3 months after last mailing; T3). UC participants were provided with the SLM treatment materials after completing T3 assessment. All participants received $60 after T2 and T3 assessments. This research was approved by the regional cancer hospital IRB.

Treatment Materials

Participants in both TTMI and SLM received materials focused on cancer survivor health behaviors. As in FRESH START [14], goals for participants were to consume at least 5 servings of F/V per day, consume <30% of calories from fat, and gradually increase moderate intensity physical activity to 150 minutes/week. In each mailing, treatment materials included a mix of reviewing their behavioral goals, recipe modifications to help participants reach their dietary goals, and opportunities for physical activity. Specific behavioral skills were addressed in each mailing (e.g., ways to stretch safely; ways to eat healthily in social settings). To ensure that participants were engaging in the intervention, each mailing included a brief section that participants were asked to complete and return in a self-addressed, stamped envelope corresponding to that mailing's topic as well as their goals and goal progress in the past two weeks. Participants also kept a copy of each mailing.

Along with the common content, TTMI materials had additional content focused on enhancing and directing motivation to change explicitly based on the teachable moment related to BC survivorship. The research team drew upon our experiences creating and implementing stress management and behavior change interventions and the literature on BC survivors’ psychosocial concerns and stress management programs to develop a lifestyle intervention tailored to BC survivors. This intervention addresses survivorship concerns relevant to health behavior change by providing materials explicit to these topics and experiential writing exercises (“How might being a cancer survivor help you find the motivation to make and maintain important lifestyle changes?”) to deepen their impact. Table 1 outlines the eight TTMI topics.

Table 1.

Components of Interventions

| Mailing | Common Content in SLM and TTMI | Additional TTMI Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Introductory Materials on Need for Health Behavior Change and Specific Strategies | The Teachable Moment Concept |

| 2. | Barriers | Strengths as well as barriers |

| 3. | Stress/Coping Problem-solving skills | Concerns and Worries directly related to Breast cancer |

| 4. | Social Support | Social Support Issues in Cancer Survivorship |

| 5. | More Advanced Material on Healthy Diets | Boost Positive Affect through Focus on Gratitude/Benefits |

| 6. | More Advanced Material on Physical Activities | Spirituality and Life Meaning |

| 7. | Self-Efficacy | Self-efficacy in making changes. Drawing on Identified Strengths |

| 8. | Changes as a Lifestyle to Maintain/Relapse Prevention | Journey as a Cancer Survivor |

Measures

Demographics and cancer-related variables at baseline

Age, race/ethnicity, level of education, level of income, marital status, and weight and height to calculate body mass index (BMI) were assessed. Also, prior cancer diagnosis (yes/no), and current cancer treatment (yes/no) were assessed.

Health behaviors at each time point

Daily servings of F/V intake was assessed and scored according to the National Institute of Health fruit and vegetable screener [21]. Participants reported their frequency and amount of various kinds of F/V intakes such as 100% juice, fruits, lettuce salad, vegetable soups, and so on over the last month. Further, fat intake (daily estimated calories from fat) was assessed and scored according to the National Cancer Institute fat screener [22]. Participants reported their eating habits on 15 foods over the past month from 0 (never) to 7 (2 or more times per day). Sample items include: “How often did you eat regular fat cheese or cheese spread?” and “How often did you eat regular fat sausage or bacon?” Physical activity was assessed with a widely used measure, the Paffenbarger Activity Questionnaire. Participants reported number of flights of stairs they climbed and number of city blocks they walked, on average, each day in the past week. Also, they reported any sports, recreational, or physical activities they participated and their frequency and length (minutes) during the past week. We computed weekly minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (multiplying frequency and length). However, many participants (n=81 at T1; n=60 at T2; and n=66 at T3) marked their answers on other items on the scale, but left blank the frequency and length of physical activity item, which was needed to calculate MVPA. We replaced their MVPA with zero.

Intervention feasibility

At T2 and T3, intervention group participants rated their intervention with respect to recommendations to others, satisfaction, relevance, meaningfulness, and motivation maintenance from 1 (strongly disagree) to 8 (strongly agree). They were also asked to select the most desirable format of intervention from among face-to-face, internet, conference calls, and mail-based (multiple choices were allowed).

Analytic Strategies

First, we compared baseline demographics and health behaviors among groups to determine whether randomization was successful. Second, skewed dependent variables were log10-transformed and a correlational analysis among demographics and cancer-related variables and health behaviors was conducted. Finally, repeated measures ANCOVAs (controlling for demographics and cancer-related variables based on the correlational analysis) were conducted to examine whether the effects of intervention differ across time. If sphericity was not assumed, Greenhouse-Geisser was reported. Further repeated measures ANCOVAs and subsequent univariate ANCOVAs with post-hoc (LSD) investigated interaction effects. Unlike FRESH START and other mail-based interventions, we did not exclude participants at baseline who expressed an interest in improving their health behaviors. Analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS 22.

Results

Randomization Check

The three groups did not differ with respect to baseline demographics including age, race/ethnicity, education, household income, or marital status (see Table 2). Although there was no group difference in current treatment, more survivors who had a prior cancer diagnosis were in the SLM group. There were also no group differences with respect to baseline BMI, F/V and fat intake, or minutes of MVPA. At baseline, 59.4% of participants reported less than 30% of fat intake and 25.9% of participants engaged in ≥150 minutes of MVPA; only 3% of participants reported 5 servings of F/V intake.

Attrition

Participants who completed the T2 survey and those who did not did not differ with respect to baseline age, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, BMI, F/V and fat intake, MVPA, or group status. Also, participants who completed the T3 survey and those who did not did not differ in baseline age, race/ethnicity, education, income, marital status, BMI, F/V and fat intake, MVPA, or group status.

Relationships among Demographics, Cancer-related Variables and Health Behaviors

A correlational analysis was conducted to examine relationships among demographics, cancer-related variables and health behaviors. First, given that F/V intake and MVPA were positively skewed, they were log10-transformed. Results (both transformed and raw data) are presented in Table 3. Most demographics and cancer-related variables were unassociated with dietary behaviors, but several were significantly associated with physical activity: baseline age and BMI were negatively related to minutes of MVPA, whereas higher education and income were positively associated with MVPA.

Table 3.

Relationships among Demographics, Cancer-related Variables, and Health Behaviors Outcomes

| M (SD) | age | Education | Income | Marital status | Prior cancer diagnosis | Current treatment | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 F/V intake | 1.55 (1.21) | −.08 (−.06) | .10 (.07) | .14† (.08) | .09 (.02) | −.00 (.03) | .08 (.09) | −.02 (−.06) |

| T2 F/V intake | 1.91 (1.49) | −.10 (−.05) | −.02 (−.03) | −.02 (−.04) | −.12 (−.13) | −.10 (−.03) | .01 (.07) | −.06 (−.10) |

| T3 F/V intake | 1.81 (1.34) | −.14 (−.12) | .09 (.06) | −.01 (−.01) | −.09 (−.10) | −.17† (−.17†) | .03 (.06) | −.04 (−.08) |

| T1 Fat intake | 29.54 (3.61) | (.06) | (−.08) | (−.13) | (−.06) | (−.05) | (.04) | (.09) |

| T2 Fat intake | 28.76 (3.80) | (.11) | (−.07) | (−.06) | (−.02) | (.09) | (.08) | (−.08) |

| T3 Fat intake | 28.66 (2.83) | (.09) | (.01) | (−.03) | (.01) | (.08) | (.06) | (.01) |

| T1 MVPA | 27.15 (46.44) | −.21** (−.18*) | .32** (.27**) | .23** (.21*) | .04 (.07) | .00 (−.03) | .07 (.13) | −.26** (−.27**) |

| T2 MVPA | 51.02 (90.27) | −.06 (.02) | .21** (.22*) | .14 (.20) | .04 (.12) | −.03 (−.04) | .03 (.05) | −.23** (−.20*) |

| T3 MVPA | 66.60 (149.19) | −.25** (−.17†) | .22* (.15) | .30** (.21*) | .17† (.20*) | −.16† (−.15) | .05 (−.02) | −.18** (−.12) |

Note. Raw M and SD are presented. Correlation coefficients are based on log10-transformed data. Correlation coefficients in parenthesis reflect correlation coefficients of raw data. Fat intake was not log10-transformed. F/V = fruit and vegetables; MVPA = moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

p < .10

p < .05

p < .01.

Changes in F/V Intake over Time among Groups

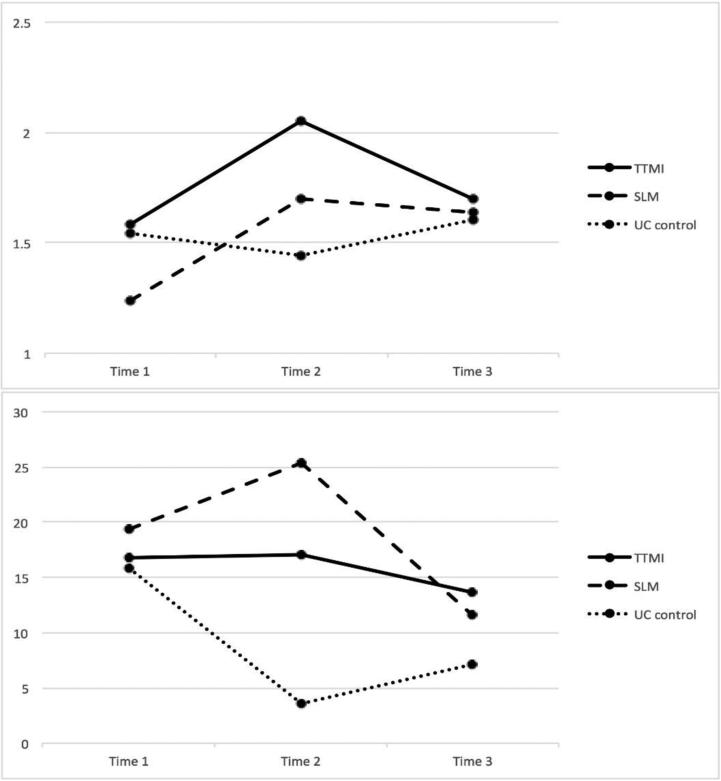

A repeated measure ANCOVA was conducted by controlling for prior cancer diagnosis and household income, based on the correlational analysis with log10-transformed data (See Figure 2 upper panel). There was no main effect of group [F(2,107)=.62, p=.54, partial eta square (ηp2)=.01], but there was a main effect of time [F(1.83,195.38)=5.55, p=.01, ηp2=.05] and a time × group interaction [F(3.65,195.38)=3.08, p=.02, ηp2=.05]. To understand the interaction effect, we conducted a series of repeated measure ANCOVA (again controlling for prior cancer diagnosis and income) for F/V change from T1 to T2, F/V change from T2 to T3, and F/V change from T1 to T3. Results showed that there was a significant interaction effect from T1 to T2 and from T2 to T3: F/V intake increased in TTMI and SLM, whereas it decreased in UC from T1 to T2: F(2,121)=5.35, p=.01, ηp2=.08. Also, F/V intake decreased in TTMI and SLM, whereas it increased in UC from T2 to T3: F(2,107)=3.88, p=.02, ηp2=.07.

Figure 2.

The upper panel shows fruit and vegetable intake. The lower panel shows minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Y axis reflects estimated marginal means retransformed from log10.

Subsequent univariate ANCOVAs (controlling for income and prior cancer diagnosis) were conducted to find out whether there was a group difference regarding changes in F/V intake. Results showed a significant group difference in changes from T1 to T2: [F(2,121)=5.35, p=.01, ηp2=.08]. Post-hoc (LSD) analysis showed that TTMI [t(122)=2.71, p=.01] and SLM [t(122)=2.79, p=.01] participants increased in F/V intake from T1 to T2 more than did UC participants. Changes from T2 to T3 were also significant: F(2,107)=3.88, p=.02, ηp2=.07. TTMI participants reported greater decreases in F/V intake from T2 to T3 compared with those in UC: t(122)=−2.83, p=.01.

Changes in Fat Intake over Time among Groups

There was a main effect of time [F(2,226)=4.31, p=.02, ηp2=.04] in fat intake; fat intake decreased over time. However, there was no significant effect for group [F(2,113)=1.89, p=.16, ηp2=.03] or time × group interaction [F(4,226)=1.13, p=.34, ηp2=.02].

Changes in Minutes of MVPA over Time among Groups

A repeated measure ANCOVA controlling age, prior diagnosis, level of education, household income, marital status, and baseline BMI was conducted for minutes of MVPA (see Figure 2 lower panel). Results showed that there was no main effects of time [F(2,200)=.27, p=.77, ηp2=.003] or group [F(2,100)=1.72, p=.19, ηp2=.03]. The interaction effect of time × group was marginally significant [F(4,200)=218, p=.07, ηp2=.04]. A series of repeated measure ANCOVAs showed that there was a significant interaction effect from T1 to T2 and a marginally significant interaction effect from T2 to T3. Minutes of MVPA increased in SLM and TTMI, but decreased in UC from T1 to T2: F(2,116)=3.51, p=.03, ηp2=.06. From T2 to T3, minutes of MVPA tended to decrease in SLM and TTMI, but increased in UC: F(2,100)=2.85, p=.06, ηp2=.05.

Univariate ANCOVAs (controlling for age, income, education, marital status, prior cancer diagnosis, and baseline BMI) showed that there was a significant group difference in changes from T1 to T2: F(2,116)=3.51, p=.03, ηp2=.06. Changes in minutes of MVPA from T1 to T2 were significantly higher in SLM than UC [t(117)=1.80, p=.07] and marginally significantly higher in TTMI than UC, [t(117)=2.01, p=.046]. Changes from T2 to T3 were only marginally significant, [F(2,100)=2.85, p=.06, ηp2=.05]. A post-hoc test showed that minutes of MVPA from T2 to T3 decreased more in SLM than in UC: t(101)=−2.36, p=.02.

Intervention Adherence

Mean number of materials sent back from participants (range=0-8) in the intervention groups was 6.04 (SD=2.43). However, about one fifth (21.7%) sent back fewer than four of the materials. Number of returned materials did not differ by groups (TTMI vs. SLM), t(113)=−.09, p=.85. Excluding participants who did not send back at least four sets of materials, we conducted the above-reported repeated measure ANCOVAs and univariate ANCOVAs (if appropriate) for each health behavior. Results were similar (data not shown).

Feasibility Analyses

We examined the M and SD of the general ratings of the interventions at T2 and T3 among participants in the intervention groups. Results (see Table 4) showed that participants reported high satisfaction with the content of the interventions. There was no group difference regarding answers to any of the five questions. We further examined the extent to which participants perceived this study helped improve their health behaviors. Results (see Table 4) showed that participants perceived that the intervention slightly helped them improve their health behaviors and was slightly useful to improve health behaviors. Again, there was no group difference.

Table 4.

Ratings regarding satisfaction and usefulness of the Interventions at Post and Follow-up Intervention

| Post-intervention | Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| General Ratings regarding the Interventions | |||

| 1. | “I would recommend the approach I was taught in this program to other breast cancer survivors” (1-8) | 6.19 (1.66) | 6.32 (1.70) |

| 2. | “I am satisfied with what I've achieved in this program” (1-8) | 5.79 (1.93) | 5.76 (1.89) |

| 3. | “The information I learned in the program would be relevant to other breast cancer survivors” (1-8) | 6.56 (1.63) | 6.62 (1.57) |

| 4. | “Participating in this program was a meaningful experience for me” (1-8) | 5.83 (2.06) | 6.10 (1.83) |

| 5. | “I am certain that I will remain motivated to incorporate these healthy behaviors in the future” (1-8) | 6.67 (1.61) | 6.67 (1.68) |

| Perceived Usefulness of the Effects of Interventions on Health Behaviors | |||

| 1. | “How much did you increase your fruit/vegetable intake?” (0-3) | 1.72 (.83) | 1.51 (.80) |

| 2. | “How much did you reduce your fat intake?” (0-3) | 1.72 (.85) | 1.40 (.90) |

| 3. | “How much did you increase your activity level?” (0-3) | 1.47 (1.47) | 1.41 (.94) |

| 4. | “How useful was this study for helping you increase your fruit/vegetable intake?” (0-3) | 1.81 (.90) | 1.63 (.98) |

| 5. | “How useful was this study for helping you reduce your fat intake?” (0-3) | 1.58 (.94) | 1.43 (1.01) |

| 6. | “How useful was this study for helping you increase your activity level?” (0-3) | 1.58 (.94) | 1.36 (1.01) |

Finally, at T2 and T3, we investigated preferred intervention formats in intervention participants. Results showed that participants preferred mail-based intervention (51.4%) followed by face to face (44.6%), Internet (31.1%), and conference call (23.0%) at T2. At T3, participants preferred mail-based intervention (61.1%) followed by face to face (34.1%), Internet (34.1%), and conference call (19.5%). There was no group difference.

Discussion

We aimed to determine if mail-based interventions that required minimal resources would be effective in helping BC survivors change their health behaviors following treatment, a teachable moment. Previous mail-based studies have demonstrated effectiveness in helping survivors change their diet and exercise in healthy ways. Our overarching goal was to determine whether such interventions might be efficacious if conducted over a shorter period of time that involved more frequent contact with participants.

Our interventions produced short-term salutary effects in F/V consumption. Both TTMI and SLM participants reported increased F/V intake from T1 to T2. In contrast, participants in UC reported slightly decreased daily F/V intake from T1 to T2. We found no intervention effects on fat intake, but participants’ fat intake decreased over time. With respect to physical activity, changes in minutes of MVPA from T1 to T2 were higher in SLM than UC and marginally higher in TTMI than UC. However, these changes were due to decreased minutes of MVPA in UC rather than increases in minutes of MVPA in the intervention groups: SLM (+5.99) vs. TTMI (+.25) vs. UC (−12.32).

These gains in F/V intake and physical activity are modest. Unlike interventions like FRESH START, we did not exclude participants who were already at or above goal, meaning that we included a number of survivors already living healthy lifestyles and having little room for improvement. Thus, ceiling effects may have limited our ability to effect more change.

Effects of behaviors changes did not differ between TTMI and SLM. Indeed, they have similar health behavior trends, suggesting that including psychosocial issues along with behavior change strategies provided no additional advantage. Perhaps survivors were not fully ready to absorb additional content, consequently yielding equivocal results. Future research is needed to understand whether and how to specifically incorporate survivorship concerns.

Intervention participants did not effectively maintain these changes. Participants in TTMI reported greater decreases in F/V intake from T2 to T3 compared with those in control group: −.36 vs. +.16. Likewise, minutes of MVPA from T2 to T3 tended to decrease in SLM (−13.8), but increase in UC (+3.53). We do not know why UC participants slightly increased F/V intake and MVPA during the short maintenance period in our study. Participants assigned to UC expressed disappointment; although they did not engage in healthier behaviors right after group assignment, they may have been highly motivated (evidenced by their low attrition) to engage in other health behavior improvement efforts. Substantial improvement in control condition participants is common; for example, in FRESH START, the attention control group improved their F/V and fat intake as well as their MVPA (mean increasing from 44 to 83 minutes/week across a year of maintenance) [23].

Maintenance of health behavior change is difficult [24]; our intervention made no provisions to provide support or guidance following its end; it is thus, perhaps, not surprising that participants regressed towards their baseline levels of diet and physical activity. However, this may be due to intervention characteristics. For example, a recent meta-analysis regarding health behavior maintenance following PA and dietary interventions [26] showed that intervention characteristics such as duration (e.g., more than 24 weeks) and number of intervention contacts (e.g., mean 13) differentiated interventions achieving maintenance from those not achieving maintenance. Indeed, intensive interventions (≥ 10-month duration and/or more frequent contacts) reported sustained intervention effects (add FRESH START, WINS, WHEL) in cancer survivors. Thus, the shorter duration (about 16 weeks) and lower frequency (8 mailings) might explain why our effects were not prolonged, although effects of intervention characteristics in health behavior maintenance among BC survivors are not yet established [24]. In fact, few lifestyle interventions for BC survivors include a maintenance phase [24], clearly an important direction to pursue in continued intervention development of these.

Study limitations should be noted. Our study was not fully statistically powered and had a fairly high attrition rate (about 23%). Also, substantial missing data in physical activity, which we assumed to be zero, may underestimate participants’ actual amount of physical activity. Moreover, health behaviors were assessed via self-report measures; future studies should use objective measures. Finally, our sample was largely white and middle-class, which may limit generalizability.

Many BC survivors have poor health behaviors, impairing life quality and creating vulnerabilities for future health problems (see [1]). Interventions are needed to help survivors improve their lifestyles [16]. Most currently-offered interventions require intense resources and are difficult to sustain, especially in community-based hospitals where most patients receive their cancer and post-cancer care. We aimed to determine if interventions that can be easily implemented would be useful to survivors. Results suggest that these interventions assisted survivors in their change efforts. Further, survivors rated them quite highly and would recommend them to other survivors.

In this digital age, we anticipated that participants would prefer Web-based interventions but in fact, by T3, nearly two-thirds expressed a preference for receiving materials in the mail. Perhaps receiving something tangible and distinct from the daily barrage of email made the materials stand out. Such low-resource interventions may be important ways to promote healthy lifestyles necessary for survivor’ health and well-being.

Acknowledgement

This research was funded by the National Cancer Institute (5R21CA152129-2).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Adams RN, Mosher CE, Blair CK, et al. Cancer survivors' uptake and adherence in diet and exercise intervention trials: an integrative data analysis. Cancer. 2015;121:77–83. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28978. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison S, Hayes SC, Newman B. Level of physical activity and characteristics associated with change following breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:387–394. doi: 10.1002/pon.1504. doi:10.1002/pon.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holick C, Newcomb P, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Physical activity and survival after diagnosis of invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:379–385. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0771. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes M, Chen W, Feskanich D, Kroenke C, Colditz G. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293:2479–2486. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. doi:10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newton RU, Galvão DA. Exercise in prevention and management of cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2008;9:135–146. doi: 10.1007/s11864-008-0065-1. doi:10.1007/s11864-008-0065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Kane R. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1588–1595. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0703. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chlebowski RT, Blackburn GL, Thomson CA, et al. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: interim efficacy results from the women's intervention nutrition study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1767–1776. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj494. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, et al. Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: An American Cancer Society Guide for Informed Choices. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:323–353. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.6.323. doi:10.3322/canjclin.56.6.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vrieling A, Buck K, Seibold P, et al. Dietary patterns and survival in German postmenopausal breast cancer survivors. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:188–192. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.521. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, McNeel T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: Examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8884–8893. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coups E, Ostroff J. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and non-cancer controls. Prev Med. 2005;40:702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.011. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kushi LH, Doyle C, McCullough M, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines on nutrition and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:30–67. doi: 10.3322/caac.20140. doi:10.3322/caac.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rabin CS. Promoting lifestyle change among cancer survivors: When is the teachable moment? Am J Lifestyle Med. 2009;3:369–378. doi:10.1177/1559827609338148. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, et al. Main outcomes of the FRESH START trial: A sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;19:2709–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7094. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. doi:10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz N, Rowland J, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: Promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5814–5830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demark-Wahnefried W, Jones LW. Promoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:319–342. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.012. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Morey MC, et al. Lifestyle intervention development study to improve physical function in older adults with cancer: outcomes from Project LEAD. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3465–3473. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.7224. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.05.7224c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, et al. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: the Women's Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;298:289–298. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.289. doi:10.1001/jama.298.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blanchard CM, Denniston MM, Baker F, et al. Do adults change their lifestyle behaviors after a cancer diagnosis? Am J Health Behav. 2003;27:246–256. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.3.6. doi:10.5993/AJHB.27.3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stull VB, Snyder DC, Demark-Wahnefried W. Lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors: designing programs that meet the needs of this vulnerable and growing population. J Nutr. 2007;137:243S–248S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.243S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. [9 November 2015];National Institutes of Health Eating at America's table study Quick food scan. http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/diet/screeners/fruitveg/allday.pdf.

- 23. [9 November 2015];National Cancer Institute Quick food scan. http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/diet/screeners/fat/percent_energy.pdf.

- 24.Mosher CE, Lipkus I, Sloane R, Snyder DC, Lobach DF, Demark-Wahnefried W. Long-term outcomes of the FRESH START trial: exploring the role of self-efficacy in cancer survivors' maintenance of dietary practices and physical activity. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:876–885. doi: 10.1002/pon.3089. doi: 10.1002/pon.3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spark LC, Reeves MM, Fjeldsoe BS, Eakin EG. Physical activity and/or dietary interventions in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of the maintenance of outcomes. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:74–82. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0246-6. doi:10.1007/s11764-012-0246-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fjeldsoe B, Neuhaus M, Winkler E, Eakin E. Systematic review of maintenance of behavior change following physical activity and dietary interventions. Health Psychol. 2011;30:99–109. doi: 10.1037/a0021974. doi:10.1037/a0021974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]