Abstract

Lipin-1, a mammalian phosphatidic acid phosphatase (PAP), is a bi-functional molecule involved in various signaling pathways via its function as a PAP enzyme in the triglyceride synthesis pathway and in the nucleus as a transcriptional co-regulator. In the liver, lipin-1 is known to play a vital role in controlling the lipid metabolism and inflammation process at multiple regulatory levels. Alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD) is one of the earliest forms of liver injury and approximately 8–20% of patients with simple steatosis can develop into more severe forms of liver injury, including steatohepatitis, fibrosis/cirrhosis, and eventually hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The signal transduction mechanisms for alcohol-induced detrimental effects in liver involves alteration of complex and multiple signaling pathways largely governed by a central and upstream signaling system, namely, sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)-AMP activated kinase (AMPK) axis. Emerging evidence suggests a pivotal role of lipin-1 as a crucial downstream regulator of SIRT1-AMPK signaling system that is likely to be ultimately responsible for development and progression of AFLD. Several lines of evidence demonstrate that ethanol exposure significantly induces lipin-1 gene and protein expression levels in cultured hepatocytes and in the livers of rodents, induces lipin-1-PAP activity, impairs the functional activity of nuclear lipin-1, disrupts lipin-1 mRNA alternative splicing and induces lipin-1 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Such impairment in response to ethanol leads to derangement of hepatic lipid metabolism, and excessive production of inflammatory cytokines in the livers of the rodents and human alcoholics. This review summarizes current knowledge about the role of lipin-1 in the pathogenesis of AFLD and its potential signal transduction mechanisms.

Keywords: Lipin-1, Alcoholic fatty liver disease, Lipid metabolism, Inflammation, Transcriptional regulators, Signal transduction

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol abuse leads to liver injury associated with alcoholic steatosis/steatohepatitis, hepatitis, liver fibrosis/cirrhosis, and liver cancer (1,2). Clinically, up to 44% of all deaths from liver injury may be attributable to alcohol abuse (1,2). Alcoholic fatty liver (AFLD) is the most common and early response of the liver in response to heavy chronic, acute or chronic-binge alcohol consumption (3). Despite AFLD being a reversible presentation of the liver pathology, patients with simple alcoholic steatosis (approximately 8–20%) can progress to more severe forms of liver injury, including steatohepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis, and eventually liver failure (1–5). Multiple factors contribute to progression of AFLD to more sever forms of liver injuries including race, gender, obesity, hepatitis C virus (HCV), known or unknown genetic or environmental factors (1–5). Although life-style changes such as abstinence from alcohol is the long-term goal of management of alcoholic liver disease, this may not be always practical or sufficient. To date, an effective treatment to cure AFLD is still lacking. It is only through better understanding of pathogenic mechanisms that novel therapies targeting AFLD can be discovered.

Over the past decades, there has been significant research progress toward understanding the pathogenesis of AFLD. Chronic, acute, or chronic-binge ethanol exposure impairs lipid metabolism and inflammation pathways mediated by various crucial transcriptional regulators and leads to excessive accumulation of fat and generation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in liver (1–5). The various signaling pathways for alcohol-induced detrimental effects in liver is largely governed by the upstream signaling system, namely, sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)-AMP-activated kinase (AMPK) axis (3). Nevertheless, the crucial issue of whether and how ethanol-mediated disruption of a vital downstream signaling route that is ultimately responsible for development and progression of AFLD has not been resolved.

Lipin-1 is a bi-functional molecule that regulates lipid metabolism and inflammation process in the nucleus via interactions with transcription regulators and at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) as a mammalianMg2+-dependent phosphatidic acid phosphohydrolase (PAP) to catalyzethe penultimate step in triglyceride synthesis (6,7). The gene encoding lipin-1 (LPIN1) was first identified in 2001 and two additional lipin family members, lipin-2 and lipin-3, were identified based on a −60% similarity in predicted amino acid sequence to lipin-1 (6–8). All three lipin proteins have a PAP activity and contain a putative nuclear localization signal (6–8).

Three lipin-1 protein isoforms [lipin-1α (891 amino acids), lipin-1β (924 amino acids), and lipin-1γ (26 amino acids)] can be generated via alternative mRNA splicing of an internal exon within the LPIN1 (9–13). While lipin-1α and lipin-1β express in various tissues, lipin-1γ isoform is a lipid droplet-associated protein highly expressed in the brain (13). In the liver and adipose tissue, lipin-1α and lipin-1β are localized at different subcellular compartments. In hepatocytes, lipin-1α is predominantly located in the nucleus, whereas lipin-1β is primarily located in the cytoplasm (9–13).

In recent several years, lipin-1 has emerged as a pivotal regulator involved in the development and progression of AFLD via its dual function as a PAP enzyme in the triglyceride synthesis pathway and in the nucleus as a transcriptional co-regulator (14–18). In this review, we will summarize the current knowledge of the role of lipin-1 in the pathogenesis of AFLD and discuss the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms and pathways affected by alcohol, which result in altering the lipin-1 gene and protein expression, alternative mRNA splicing, cellular localization and functions of lipin-1. We will also assess the potential therapeutic strategies for treating patients with AFLD via nutritional and pharmacological modulation of lipin-1 signaling.

ROLE OF LIPIN-1 IN AFLD

Considerable evidence suggests a vital role for lipin-1 in the development and progression of AFLD (14–22). Ethanol exposure up-regulates the lipin-1 expression (gene and protein) and favors production of cytosolic lipin-1 protein, resulting in increased PAP activity and TAG synthesis in cultured hepatocytes and in mouse livers (14,15). Ethanol also blocks lipin-1 nuclear entry, and suppresses nuclear lipin-1-mediated fatty acid oxidation as well as hepatic very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)-triacylglyceride (TG) secretion in mouse livers (15–18). Moreover, ethanol-mediated impairment of lipin-1 alternative mRNA splicing occurs in cultured hepatocytes and in the livers of rodents and patients with alcoholic hepatitis (19). The net consequences of these alterations are to promote hepatic steatosis, inflammation, mild fibrosis and contributes to AFLD. In an alcoholic cellular steatosis model, ethanol or overexpression of lipin- 1β significantly increased the lipid accumulation in AML-12 hepatocytes and lipin-1β overexpression also mildly enhanced ethanol-mediated fat accumulation (19). However, the ethanol-mediated lipid accumulation was largely alleviated in Ad-lipin-1α-overexpressing AML-12 cells compared to Ad-GFP controls (19). In a genetic lipin-1 liver specific knockout mouse (lipin-1LKO) model, chronic ethanol administration to lipin-1LKO mice exacerbated alcohol-induced steatohepatitis (19). These findings clearly demonstrate the causal role of lipin-1 in development and progression of AFLD.

Epidemiological evidence shows that alcohol abuse synergistically increases the prevalence and severity of liver injury in obese patients (18,22–27). On the other hand, liver damage in alcohol abusers is significantly exacerbated by obesity. Despite the synergistic effects of alcohol and obesity in liver injury in clinical patients being well documented, the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. Utilizing genetically obese mice fed with ethanol, the obese ob/ob mice displayed much more pronounced changes in terms of liver steatosis and elevated plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), indicators of liver injury, compared with lean pair-fed control mice (18). More importantly, the exacerbated fatty liver observed in chronically ethanol-fed ob/ob mice is closely associated with aberrant lipin-1 signaling, suggesting that alcohol and obesity may work in unison to exacerbate development of steatohepatitis via disruption of lipin-1 signaling in the liver (18).

Lipin-1-mediated phosphatidate phosphohydrolase (PAP) activity and AFLD

As addressed above, lipin-1 displays enzymatic activity as a cytosolic PAP protein (6–8). Lipin-1-mediated PAP activity is Mg2+-dependent and n-ethylmaleimide (NEM) sensitive and is responsible for most of the PAP activity that occurs in the glycerol phosphate pathway (6–8). In the elevated fatty acid conditions, lipin-1-PAP protein translocates from the cytosol to the endoplasmicreticulum (ER) membrane, where PAP enzyme converts phosphatidic acid (PA) to diacylglycerol(DAG) (6–8). The DAG then serves as a substrate for thesynthesis of triglycerides (TGs) as well as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE). Among three mammalian lipin proteins (lipin-1, lipin-2 and lipin-3), lipin-1 exhibits the highest specific PAP activity (6–8).

Prior to the cloning of lipin-1 in 2001, several lines of evidence had suggested that alcohol-mediated dysregulation of PAP contributes to the abnormalities in hepatic lipid metabolism linked with AFLD (20–22).Hepatic PAP activity substantially increased in the livers of ethanol-fed baboons and human alcoholics, and activation of PAP by ethanol consumption was associated tightly with the development of liver steatosis (20–22). Consistent with these previous findings, our group has found that chronic ethanol exposure significantly up-regulates total lipin-1 gene and protein expression levels and favors accumulation of cytosolic lipin-1 protein, resulting in increased PAP activity and TAG synthesis in both cultured hepatocytes and in mouse livers (15,17). These findings by us and others clearly suggest that the elevated hepatic lipin-1 mRNA and protein levels observed with ethanol exposure in whole or in part contribute to increased hepatic PAP activity and the development of excessive fat accumulation in liver.

Recent emerging evidence suggests a much more complex role of lipin-1-PAP and its relationship with AFLD (17). Utilizing lipin-1LKO mice, our group sought to determine whether loss of hepatic lipin-1-PAP would reduce ethanol-induced intrahepatic fat accumulation via attenuated PAP activity (17). Indeed, we found that specific removal of lipin-1 from the liver effectively abolished the increase in ethanol-mediated hepatic PAP activity. To our surprise, chronic ethanol administration to lipin-1-PAP deficiency mice (lipin-1lKO) has revealed a dramatically aggravated accumulation of neutral lipid droplets in the liver, implying that lipin-1-PAP may play a protective role against alcoholic steatosis in mice (17). Lipin-1-PAP deficiency in liver also exacerbated inflammation and liver injury in ethanol-fed lipin-1LKO mice. In the fatty liver dystrophy (fld) mice, the severe liver steatosis was associated with increased hepatic lipin-2-mediated PAP activity (8). However, given the fact that the hepatic total PAP activity was abolished in the lipin-1LKO mice (17), it is unlikely that lipin-2-mediated PAP activity contributes to exacerbated fatty liver in lipin-1LKO mice fed with ethanol.

Although the basis for the apparently paradoxical action of lipin-1-PAP in the pathogenesis of AFLD is not fully understood, the induction in lipin-1-PAP activity in AFLD may play a protective role by normalizing phosphatidic acid (PA) levels, inducing autophagy, limiting inflammation, promoting efficient lipid storage, or controlling the transcriptional regulation of fatty acid catabolism. The protective function of lipin-1-PAP against AFLD will be further discussed in the following sections.

Lipin-1-mediated transcriptional co-regulator activity and AFLD

The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), and PPARγ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) are two prominent regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis and cellular energy metabolism in several tissues including liver (28, 29). The PGC-1α /PPARα dyad plays a key role in regulating enzymes encoding genes involved in mitochondrial and peroxisomal β-fatty acid oxidation, including long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, medium-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, acyl-CoA oxidase, and very-long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase, carnitine palmitoyl transferase-I, and fatty acid binding protein, which, in turn, influence the fatty acid catabolism in liver (28,29).

Lipin-1 protein contains a putative nuclear localization signal and can be nuclear-localized. Therefore, lipin-1 displays a second distinct function in regulating lipid metabolism that is dependent on its nuclear localization (30). Lipin-1 enters the nucleus and directly interacts with and co-activates PGC-1α and PPARα and enhances the expression of mitochondrial genes involved in fatty acid oxidation. Interestingly, lipin-1-mediated PAP activity is dispensable for its ability to co-activate PGC-1α/PPARα dyad (30).

The role of PGC-1α/PPARα dyad in the pathogenesis of AFLD has been unequivocally established (3, 31,32). Severely impaired hepatic PGC-1α/PPARα signaling occurred consistently in ethanol-fed animals, and associated closely with development of fatty liver injury in several rodent models (3,31,32). PPARα knockout mice administrated with ethanol developed exacerbated steatohepatitis while treatment of PPARα agonists prevented liver steatosis in ethanol-fed animals via stimulating PGC-1α/PPARα regulated enzymes and increasing the rate of hepatic fatty acid oxidation (31,32).

Accumulating evidence shows that ethanol induced hepatic lipin-1 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (14–18). Chronic or chronic-binge ethanol exposure robustly increased the amount of lipin-1 in the cytoplasm and drastically decreased it in the nucleus of both cultured hepatocytes and mouse livers (15).In mouse AML-12 hepatocytes, the ability of ethanol to block lipin-1 nuclear entry impaired nuclear lipin-1-mediated PGC-1α transcriptional activity (16). As discussed above, genetic ablation of hepatic lipin-1 in mice not only caused loss of PAP activity but also diminished the nuclear levels of lipin-1 in mouse livers (17). In lipin-1LKO mice fed with ethanol, the drastic liver responsiveness to ethanol in lipin-1 LKO mice are largely due to disruption of nuclear lipin-1 function and impaired capacity for fatty acid catabolism via aberrant PGC-1α (17). Indeed, removal of lipin-1 led to exacerbated suppression of a panel of enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation and augmented impairment of fatty acid oxidizing capacity in the livers of ethanol-fed mice, suggesting that the impairments in the rate of fatty acid oxidation in ethanol-fed lipin-1 LKO mice is suffice to elicit profound liver steatosis (17). Altogether, these findings suggest that nuclear lipin-1 plays a predominant role in development and progression of AFLD in liver.

Nuclear lipin-1-mediated SREBP-1 inhibition and AFLD

Sterol regulatory element binding proteins (SREBPs) (SREBP-1a, SREBP-1c, and SREBP-2) regulate lipid and cholesterol biosynthetic gene expression (33). In the liver, activation of SREBP-1 leads to enhanced hepatic lipogenesis via elevation of mRNAs of SREBP-1 regulated enzymes such as fatty acid synthase, steroyl-CoA desaturase, mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase 1, malic enzyme, ATP citrate lyase, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase, which, in turn, causes excessive hepatic lipid accumulation (33).

Lipin-1 is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein, and interestingly, nuclear-localized lipin-1 suppresses the functions of SREBP-1 (34). In hepatocytes, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) positively regulates the activity of SREBP-1 via phosphorylation and blocking the nuclear entry of lipin-1, demonstrating that nuclear lipin-1 acts as a key component of mTORC1-SREBP-1 pathway (34,35). Moreover, inhibition of hepatic mTORC1 suppresses SREBP-1 function and makes mice resistant to the development of hepatic steatosis induced by a Western diet in a nuclear lipin-1-dependent fashion (34). It is important to note that lipin-1-PAP activity is required for the effect of lipin-1 on SREBP-1 (34).

Ethanol-induced hepatic fat accumulation depends upon an activated hepatic SREBP-1 signaling in several AFLD models such as zebrafish, mice, and micropigs (3). SREBP-1 knockout mice are protected from development of fatty liver induced by ethanol (36). Paradoxically, the development of AFLD sometimes can occur in the presence of suppressed SREBP-1 signaling in rats (37,38). This apparent disparity might be due to different animal species or different diets used for the alcohol feeding studies. The mechanisms by which ethanol stimulates SREBP-1 activity are incompletely understood. Ethanol-induced endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and ethanol-mediated impairment of SIRT1-AMPK signaling system have each been suggested to contribute to the activation of SREBP-1 signaling in the AFLD mice (39,40).

As discussed above, ethanol exposure blocks lipin-1 nuclear entry in hepatocytes and in mice (15). Hepatic total and phosphorylated levels of mTOR were increased in ob/ob mice with a further increase in the ethanol administrated ob/ob mice (18). Conceivably, severely reduced nuclear lipin-1 levels seen with ethanol exposure may contribute to activate SREBP-1 signaling and the development of liver steatosis in mice. Given that ethanol stimulates mTOR signaling, the activation of SREBP activity may be mediated at least in part, through mTOR signaling. It will be of great interest to further investigate the regulation of mTORC1-nuclear lipin-1-SREBP-1 axis by ethanol, and its relationship to the alcoholic steatosis.

Lipin-1-mediated hepatic VLDL-TG secretion and AFLD

The assembly and secretion of triacylglycerol (TG)-rich very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) represents a crucial component of hepatic TG homeostasis. Owning to the complexity of lipin-1, it is very challenging to determine the precise role of lipin-1 in promoting or attenuating VLDL secretion in the liver. While lipin-1 promotes VLDL assembly/secretion in cultured hepatocytes, studies with the fld mice demonstrate that lipin-1 functions directly in the liver to inhibit VLDL-TG secretion (12,41). Studies have demonstrated that lipin-1 regulates VLDL-TG secretion via its nuclear signaling and independent of its PAP activity (12,41).

Ethanol exposure suppresses hepatic VLDL secretion in cultured hepatocytes and in animals (42). More importantly, impaired secretion of hepatic VLDL is frequently associated with massive accumulation of TG in the livers of AFLD patients (1,2,42). We have discovered that ethanol feeding significantly decreased the rates of VLDL-TAG secretion in the livers of wild-type mice compared with pair-fed control mice (17). While VLDL-TAG secretion rates were significantly increased in lipin-1LKO mice fed a control diet compared with wild-type control mice, ethanol feeding largely abolished the increase in VLDL-TAG secretion in lipin-1LKO mice, indicating that genetic removal of hepatic lipin-1 deranges the rate of VLDL-TAG secretion and the impairments of VLDL-TAG secretion are likely further aggravated in response to ethanol in lipin-1LKO mice (17). Conceivably, the ability of alcohol to impair hepatic lipin-1 function may be an underlying mechanism linking alcohol with inhibited VLDL secretion and increased excessive fat accumulation in liver. It is important to point out that, in addition to regulate fatty acid oxidation, PGC-1α activation also stimulates VLDL-TG secretion, which, in turn, attenuates high-fat diet-induced fatty liver in mice (43). Therefore, ethanol mediated disruption of the nuclear lipin-1- PGC-1α axis may inhibit VLDL-TG secretion in mice. The effects of ethanol-mediated disruption of lipin-1 signaling on hepatic VLDL-TG secretion warrants additional investigation.

Lipin-1 alternative mRNA splicing via SFRS10 and AFLD

Alternative pre-mRNA splicing is a process by which exons are either included or excluded from a single pre-mRNA, resulting in the synthesis of functionally diverse protein isoforms from an identical gene (44). In the liver, two major lipin-1 protein isoforms, namely, lipin-1α and lipin-1β are generated via alternative lipin-1 mRNA splicing (9–12). The regulation of lipin-1 mRNA splicing process is highly complex, and the underlying mechanisms remain largely unknown.

SFRS10 (official gene name, TRA2B), the homolog of Drosophila transformer-2 (Tra2), belongs to the serine/arginine-rich (SR)-like protein family of splicing factors (45). The alternatively spliced exon 6 of Lpin1 contains a GGAA sequence motif that can bind to SFRS10 (11). Therefore, SFRS10 is an important modulator of lipin-1 mRNA splicing in a PAP-independent manner (11). SFRS10 is down-regulated in the livers of obese humans and contributes to enhanced liver lipogenesis and hepatic fat accumulation (11). In mouse liver, the effects of reduced SFRS10 on lipin-1 mRNA splicing, favors the lipin-1β isoform, and increase in expression of lipogenic genes, activation of lipogenesis and development of fatty liver (11).

Ethanol significantly inhibits mRNA and protein levels of SFRS10 both in vitro cultured hepatic cells and in mouse livers (16, 19). Hepatocytes or mice administrated with ethanol show mildly but significantly reduced the mRNA levels of hepatic lipin-1α while lipin-1β mRNA expression levels were increased compared with their respective controls (18,19). As a result, the ratio of hepatic Lpin1β/α in the ethanol-exposed hepatocytes or mice was significantly elevated compared with controls (18,19).

SIRT1-SFRS10-Lpin1 β/α axis and AFLD

Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) is the founding member of the sirtuin family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent class III histone deacetylase (46). SIRT1 regulates lipid metabolism and inflammation by modifying the acetylation status of various target molecules, including histones, transcriptional factors, and its co-activators (46). Over the past several years, accumulating evidence from rodent and human studies has unequivocally demonstrated that ethanol-induced aberrant hepatic SIRT1 plays a central in the pathogenesis of AFLD (18,19.47–53). The causal role of SIRT1 in the development and progression is demonstrated by several lines of evidence. In chronically ethanol-fed mice, treatment with resveratrol, a known SIRT1 agonist, can alleviate alcoholic fatty liver injury (52). Overexpression of SIRT1 in hepatocytes prevents fat accumulation in hepatocytes exposed to ethanol (19).On the other hand, specific removal of hepatocyte SIRT1 is associated with rapid onset and progression of steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis in response to chronic-binge ethanol challenge in liver specific SIRT1 knockout (Sirt1LKO) mice (19).

Cellular and molecular mechanisms of ethanol-mediated SIRT1 inhibition and subsequent development of liver steatosis/steatohepatitis are complicated, multiple, and remain incompletely understood. However, disrupted SIRT1-SFRS10-Lpin1 β/α axis in AFLD has emerged as one of the major mechanisms (18,19). Under a chow diet, removal of hepatic SIRT1 significantly induced mRNA expression levels of total lipin-1 and lipin-1β, in SIRT1 liver specific knockout mice (Sirt1LKO) compared with the wild-type controls (19). Accordingly, the ratio of Lpin1β/α was substantially increased in the livers of Sirt1LKO mice (19). Both mRNA and protein expression levels of SFRS10 were severely reduced in Sirt1LKO compared with wild-type controls (19). These findings suggest that SIRT1 regulates LPIN 1 alternative splicing via modification of SFRS10.

Under chronic-binge alcohol challenge, genetic ablation of hepatic SIRT1 drastically exacerbated the ethanol-mediated disruption of SFRS10-Lpin1β/α, and development of steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis in ethanol-administered Sirt1LKO mice (19). More importantly, paralleling these findings in hepatocytes and mice, similar changes in mRNA levels of SIRT1, Lpin1β/α or SFRS10 were found in liver samples from patients with alcoholic hepatitis (19). Collectively, these findings strongly demonstrate that ethanol-induced aberrant lipin-1 mRNA signaling is mediated through disruption of the SIRT1-SFRS10 axis. The precise mechanism by which SIRT1 regulates SFRS10 gene and protein expression and subsequently impairs lipin-1 mRNA splicing in the livers of ethanol-fed mice remains to be elucidated.

Lipin-1-medated autophagy clearance and AFLD

Macroautophagy (referred to as autophagy) is an essential genetically programmed, evolutionarily conserved intracellular degradation process in response to various stress conditions including alcohol abuse (54). Autophagy is a highly complex dynamic process involving multiple steps. The autophagy process is regulated by over 30 autophagy-related (Atg) genes, and involves the formation of double-membraned autophagosomes, which envelop the substrates and fuse with lysosomes for degradation (54).

Recently, a role for lipin-1 in regulating autophagy clearance in muscle has been established (55). Lipin-1-related myopathy in the mouse is associated with a blockade in autophagic flux and accumulation of aberrant mitochondria. Remarkably, lipin-1-mediated PAP activity is found to be required in regulating autophagy clearance through generation of DAG and activation of the PKD-Vps34 signaling cascade (55).

Autophagy actively participates in pathogenesis of ALD (54). Owning to the complexity of autophagy process and the use of various AFLD cellular or rodent models, there are some controversial reports regarding the role of autophagy in the development of ALD. However, it is generally established that acute ethanol expose increases autophagy in cultured hepatic cells and in mouse livers (56,57). Inhibition of autophagy in hepatocytes exposed to ethanol increases intracellular lipid content (54,56,57). Loss of the autophagy capacity in rodents also aggravates fatty liver condition and liver injury induced by acute alcohol exposure, suggesting ethanol-mediated induction of autophagy is likely to regulate the intracellular level of lipids through its function in eliminating lipid droplets (54,56–58). In contrast to acute ethanol treatment, chronic alcohol exposure seems to cause impaired autophagy in the liver (54,59). Regardless of the controversies on autophagy status in ALD, it has been unequivocally established that autophagy serves as a cellular protective mechanism against alcohol-induced liver injury (54,59).

As discussed above, ethanol robustly induceslipin-1-PAP activity in cultured hepatic cells, in the livers of mouse or human (15,17,20–22). Unexpectedly, hepatic lipin-1-PAP deficiency led to increased TGs in lipin-1LKO mice fed with or without ethanol (17). While ethanol-mediated increased PAP activity can certainly lead to increased TAG synthesis and subsequently fat accumulation, the ethanol-mediated induction of hepatic PAP activity may also play a protective role, at least in part, via regulating autophagy by eliminating lipid droplets in AFLD mice. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that exacerbated accumulation of fat in the liver by ethanol administration of lipin-1LKO mice is likely because of loss of PAP activity and subsequently impaired autophagy. It will be important to further investigate whether and how ethanol-mediated induction of hepatic lipin-1-PAP activity and autophagy is functionally involved in the control of lipid homeostasis and their impacts on AFLD.

Involvement of lipin-1 in the inflammation process of AFLD

Several lines of evidence demonstrate that lipin-1 has potent anti-inflammatory properties (17, 60–62). In adipocytes, suppression of lipin-1 expression increases monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, a regulator related to adipose inflammation. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IFN-γ decrease lipin-1 mRNA and protein, but not lipin-2 or lipin-3,in mouse adipose tissue and in cultured 3T3-L1 adipocytes (60–62). Paradoxically, a recent study has revealed an unexpected role for lipin-1 as a mediator of macrophage proinflammatory activation (63). Upon Toll- Like-Receptor (TLR4) stimulation of macrophages from lipin-1-deficient animals and human macrophages deficient in the lipin-1 enzyme, the generation of proinflammatory cytokines known to be involved in inflammatory process, was reduced, suggesting that lipin-1-PAP acts as a proinflammatory mediator downstream of TLR signaling and during the development of inflammatory processes in macrophage (63).

The accumulation of hepatic fat in ALD is known to be associated with the over production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 (1–5). Our group has discovered that hepatic lipin-1 ablation led to significant increases in mRNA levels of several important proinflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1beta (IL-1β), lipocalin-2 (LCN-2) and serum amyloid A-1 (SAA-1) in mice fed with a control diet (17). Moreover, the magnitude of the increases in mRNA expression levels of those cytokines were significantly greater in ethanol-fed lipin-1 LKO mice than pair-fed controls (17). Our findings clearly suggest that endogenous hepatic lipin-1 has potent anti-inflammatory properties in mice.

The mechanism for lipin-1 function in mediating hepatic inflammatory process involves two major inflammatory regulators, namely, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and nuclear factor activated T cells c4 (NFATc4) (17,60–62). Interestingly, lipin-1 has been identified as a repressor of NFATc4 transcriptional activity in a PAP independent manner in adipocytes (62).

Ethanol administration to lipin-1LKO mice exacerbated the stimulation of NF-kB and NFATc4 as demonstrated by increased acetylated NF-κB, enhanced phosphorylated IκBα, reduced IκBα protein, elevated NF-κB DNA binding activity, and increased nuclear accumulation of NFATc4 (17). The activation of both NF-κB and NFATc4 in lipin-1LKO mice also suggests a possible cross-talk between the NF-κB and NFATc4 pathways regulated by lipin-1, and ethanol.

We have found that removal of hepatocytes lipin-1 generates oxidative stress in the liver, and the oxidative stress is further drastically augmented in response to ethanol administration in lipin-1LKO mice (17). Therefore, up-regulation of hepatic pro-inflammatory cytokines and excess production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in lipin-1LKO mice are likely contributors to markedly elevated serum makers of liver injury. In addition to hepatocytes, whether and how ethanol-mediated alteration of lipin-1 would affect inflammatory processes in Kupffer cells, and their impacts on progression of AFLD needs to be further investigated.

MODIFICATIONS OF LIPIN-1 BY ETHANOL

Owning to the complexity of lipin-1, alcohol disrupts hepatic lipin-1 at multiple regulatory levels. In cultured hepatic cells or animal livers, ethanol exposure enhances activity of a mouse Lpin1 promoter, increases cytosolic lipin-1 protein levels and induces cellular PAP activity.Ethanol exposure sequestered lipin-1 to the cytosol, and ultimately disrupts lipin-1 functions (14–22).

Lipin-1 gene (LPIN 1) expression and ethanol

The human LPIN1 promoter contains the sterol-response element (SRE) and nuclear factor Y (NF-Y)-binding sites (64). Binding of these elements by SREBP-1 and NF-Y promotes transcription of the LPIN1. Indeed, sterol-mediated regulation of lipin-1 gene transcription modulates triglyceride accumulation via activation of SREBP-1 in a PAP-dependent manner (64). As addressed above, the ability of ethanol to stimulate hepatic SREBP-1 has been firmly established (3,36). We have found that the effect of ethanol on induction of LPIN 1 is largely due to activation of SREBP-1 in cultured hepatic cells and in animal livers (15). Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIP) assays have also demonstrated that ethanol exposure significantly increased association of acetylated histone H3-Lysine 9 with the SRE-containing region in the promoter of the lipin-1 gene both in vitro cultured hepatic cells and in mouse liver (15). The recent preliminary studies in our laboratory have shown that the ability of ethanol to induce hepatic lipin-1 mRNA expression is completely abolished in SREBP-1 knockout mice (Srebp-1KO) fed with ethanol, further confirming the causal role of SREBP-1 in ethanol-mediated up-regulation of lipin-1 gene expression.

AMPK plays a key role in regulating the effects of ethanol on SREBP-1 activation, lipid metabolism, and development of AFLD (3, 39). In AML-12 hepatocytes, pharmacological or genetic stimulation of AMPK largely prevented ethanol-dependent increases in Lpin1 promoter activity and mRNA expression (15). On the contrary, pharmacological inhibition or epigenetic silencing of AMPK exacerbated the effect of ethanol on Lpin1 (15). Moreover, stimulating SREBP-1 activity by overexpression of activated nuclear form of SREBP-1c in AML-12 hepatocytes abolished the ability of AMPK to inhibit ethanol-mediated up-regulation of lipin-1 (15).Collectively, these findings suggest that ethanol-mediated up-regulation of lipin-1 is mediated, at least in part, by modulating upstream AMPK-SREBP-1 signaling.

There are several putative glucocorticoid receptor (GR) response elements (GREs) in the LPIN 1 promoter (65,66). LIPN 1 expression is directly regulated by the binding of glucocorticoids (GCs) to the GR, an effect exclusive only for lipin-1, not lipin-2 and lipin-3 in the liver and in adipose (65,66).In cultured hepatocytes, levels of lipin-1 mRNA were increased by dexamethasone (a synthetic GC), and this resulted in increased lipin-1 gene and protein levels as well as PAP activity (66).

Ethanol ingestion increases endogenous GC levels in both animals and humans (1–5,67). The involvement of GCs in ethanol’s induction of PAP activity is further supported by the study demonstrating that increased PAP levels was partially attenuated in adrenalectomized rats fed with alcohol (20). Paradoxically, lipin-1 exhibits reciprocal patterns of gene expression in livers and adipose tissues of chronically ethanol-fed mice, suggesting a mechanism partially independent of GCs effects (14). The causal role of GCs in ethanol-mediated up-regulation of lipin-1 will need to be investigated through use of genetically modified animal models such as liver-specific GR knockout mice.

Post-translational modifications of lipin-1 and ethanol

Lipin-1 is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein, and nucleocytoplasmic localization of lipin-1 is a critical factor in the determination of lipin-1 function (6–13). More importantly, nucleocytoplasmic location of lipin-1 is regulated in response to post-translational modifications such as sumoylation of lipin-1 (68). Lipin-1, including both lipin-1 α and lipin-1β, is modified by sumoylation at two consensus sumoylation sites (K566/596). Sumoylation of lipin-1α facilities its nuclear localization and increases its transcriptional co-activator activity whereas lipin-1β function is not apparently affected by sumoylation (67).Chronic alcohol administration to mice drastically decreased sumoylation levels of hepatic lipin-1, while at the same time markedly increased its level of acetylation (15). The ethanol-mediated modification of acetylation/sumoylation of lipin-1 coincided with the robustly increased amount of lipin-1 in the cytoplasm and dramatically decreased levels in the nucleus in mouse livers (15). Those findings suggest that disruption of acetylation/sumoylation by ethanol may contribute to the impairment of the nuclear localization and co-regulator activity of lipin-1 in AFLD. SIRT1 has been implicated in functional regulation of several important molecules via modification of a lysine acetylation/deacetylation-sumoylation switch (46,69). Thus, the ability of ethanol to alter acetylation/deacetylation-sumoylation of lipin-1 may be mediated via inhibition of SIRT1 by ethanol.

SIRT1 regulates lipin-1 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (16,19). Stimulation of SIRT1 largely blocked lipin-1α nucleocytoplasmic shuttling induced by ethanol in AML-12 hepatocytes (16,19). Consistently, Sirt1LKO mice or ethanol-fed wild-type mice displayed a markedly increased amount of lipin-1 in the cytoplasm, and a substantially reduced amount of nuclear lipin-1 in the liver (19). Ethanol-mediated lipin-1 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling was greatly augmented in the Sirt1LKO mice compared with wild-type mice fed with or without ethanol (19). Whether acetylation/de-acetylation-sumoylationwould serve as a molecular switch to control the nuclear localization and coactivator activity of lipin-1 in liver and how ethanol affects the functional interplay of SIRT1 and lipin-1 will require further investigation.

Aberrant expression of a specific MicroRNA, MicroRNA 217 (miR-217), mediated SIRT1 inhibition contributes to the development of AFLD (16). Interestingly, miR-217 disturbs the functions of lipin-1 via SIRT1 inhibition. Overexpression of miR-217 in AML-12 hepatocytes significantly induced total lipin-1 mRNA levels as well as the Lpin-1β/α ratio (16). While lipin-1α was localized in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of AML-12 cells, overexpression of miR-217resulted in lipin-1α localized to the cytoplasm, indicating that miR-217 governs lipin-1α nucleocytoplasmic shuttling in hepatocytes (16). Activation of SIRT1 relieved the effects of miR-217 on lipin-1, indicating involvement of miR-217-SIRT-lipin-1 axis in mediating ethanol action (16).

Lipin-1 is also modified by phosphorylation, and approximately more than 19 phosphorylation sites on lipin-1 has been identified (34,70–72). Ser106 is a major site of insulin-stimulated lipin-1 phosphorylation (72). Phosphorylation state of lipin-1 is a key mechanism for the partitioning of lipin-1 between cytosol and microsomes, and hence a determinant of PAP activity. As discussed above, mTORC1, a protein kinase, directly phosphorylates lipin-1 at multiple sites to regulate lipin-1 translocation and nuclear eccentricity (34). Whether ethanol regulates lipin-1 phosphorylation via mTORC1 and subsequently blocks lipin-1 nuclear entry and induces SREBP-1 activation will require to be further investigated.

Ethanol metabolism and its effect on lipin-1

In the liver, alcohol is predominantly metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) into acetaldehyde, and acetaldehyde is further metabolized by aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) into acetate (1–5). Ethanol can be metabolized by cytochrome P450 family 2, subfamily E, polypeptide 1 (Cyp2E1) to predominately generate reactive oxygen species. Additionally, ethanol can also be metabolized via nonoxidative pathways (5).

In AML-12 hepatocytes, pre-treatment with either 4-methylpyrazole (an ADH inhibitor) or cyanamide (an ALDH2 inhibitor) essentially blocked the ability of ethanol to interfere with lipin-1 functions (15,17). Moreover, acetate, one of ethanol’s major metabolites, shared ethanol’s ability to perturb lipin-1 signaling in hepatocytes (15,17). These results clearly indicate that ethanol metabolism is required for its effects on lipin-1 in vitro cultured hepatic cells. However, the future exploration of the in vivo effects of ethanol metabolism on lipin-1 signaling is still needed. Whether and how post-translational modifications of lipin-1 and lipin-1 function is affected by major ethanol metabolites (e.g. acetaldehyde, acetate, or ROS) also warrants future investigation.

Regulation of lipin-1 by adiponectin and ethanol

Adiponectin (30-kDa) is the most abundant adipocyte-derived adipokine in circulation and is associated with a wide range of benefits, including lipid lowering and anti-inflammatory properties (3). In the circulation, adiponectin exists either as a full-length protein or as a fragment comprised of the C-terminal globular domain. Mammalian full-length adiponectin also circulates in the serum in homomeric complexes, ranging from a low molecular weight trimeric form (LMW), to a medium molecular weight hexameric form (MMW) and a high molecular weight multimeric form (HMW) (3). These various adiponectin isoforms regulate distinct signaling pathways in the liver (3).

Dysregulation of adipose adiponectin expression and production can lead to development of alcoholic steatosis/steatohepatitis (3,73–76). In adipose tissues, peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) plays a key role in the regulation of adiponectin. Rosiglitazone, one of known PPAR-γ agonists, up-regulates adiponectin production via activation of PPAR-γ in adipocytes (3, 14). In chronically ethanol-administrated mice,supplementation of rosiglitazone up-regulated adiponectin, normalized HMW form of circulating adiponectin, increased the mRNA expression levels of hepatic adiponectin receptors, and significantly attenuated alcoholic fatty liver injury (14). While ethanol administration significantly increased the mRNA and cytosolic protein levels of hepatic lipin-1, rosiglitazone supplementation to ethanol-fed mice normalized and reduced hepatic lipin-1 levels in the livers of mice, suggesting that stimulation of adipoenctin by rosiglitazone can restore the lipin-1 function and prevent liver steatosis in response to ethanol (14).

In addition to liver, lipin-1 is highly expressed in adipocytes, and plays a vital role in the regulation of adipocyte development and function.In adipose tissue, lipin-1 is required for the induction of two important adipogenic genes, PPAR-γ and CAAT enhancer binding protein α (C/EBPα) (7,77). Both PPAR-γ and C/EBPα are major transcriptional regulators of adiponectin gene expression (3,78). Intriguingly, in contrary to the liver, the mRNA expression levels of lipin-1 were markedly reduced in visceral adipose tissue of mice receiving ethanol diet compared with the pair-fed control mice (14).

In adipocyte specific lipin-1-deficient (Adn-lipin-1KO) mouse, specific loss of adipocyte lipin-1 exacerbated the development ofAFLD (79). Mechanistic studies revealed that adipocyte adiponectin gene expression, serum total or HMW adiponectin protein levels as well as hepatic adiponectin receptor 1 and 2 were all drastically reduced in Adn-lipin-1KO mice fed with or without an ethanol-containing diet compared to wild-type control mice, indicating an essential role of adipocyte lipin-1 in regulating adiponectin signaling (79). These findings suggest that adipocyte-specific lipin-1 deletion in mice exacerbates the development and progression of AFLD potentially via impairment of adiponectin signaling.

CONCLUSION

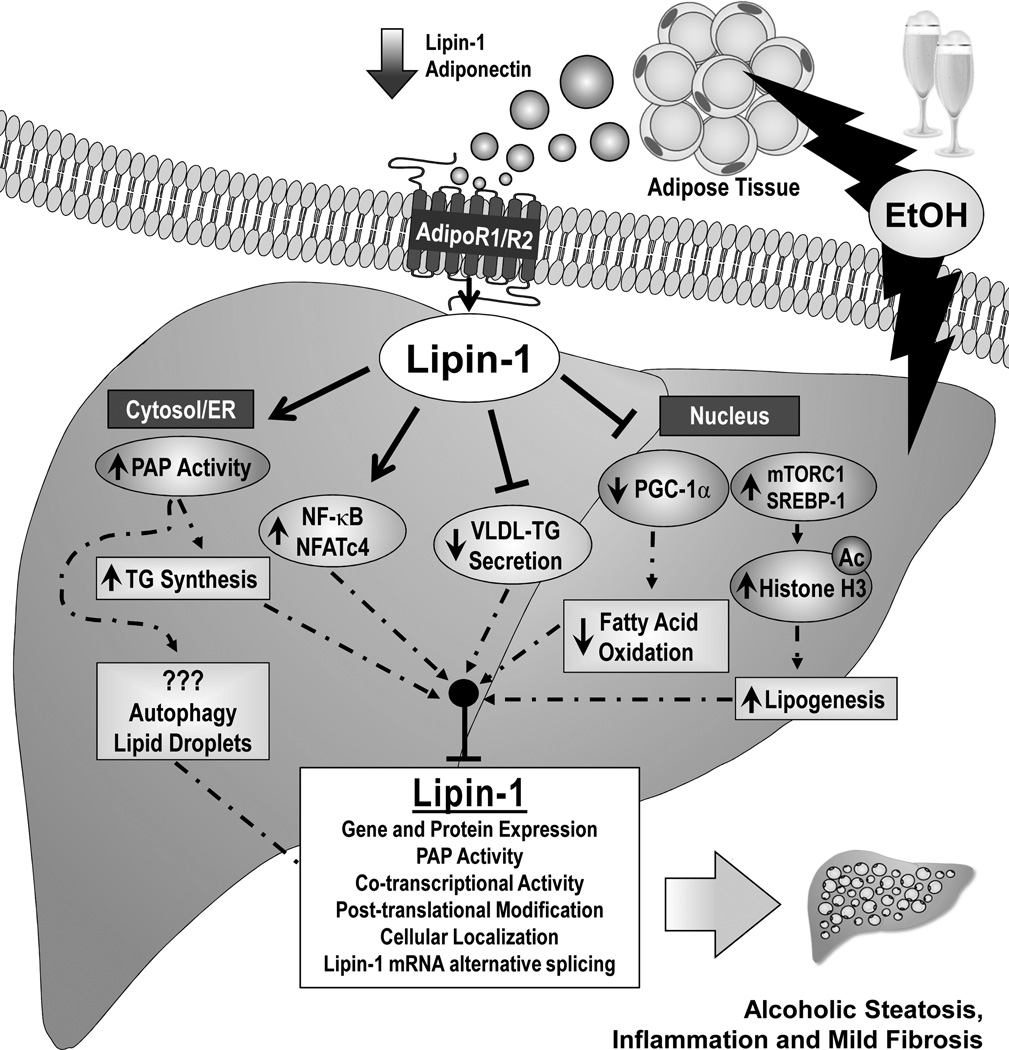

In recent years, lipin-1 has emerged as a vital signaling molecule in the pathogenesis of alcoholic fatty liver injury (14–22). Considerable evidence demonstrates that ethanol-mediated impairment of lipin-1 contributes to the abnormalities in hepatic lipid metabolism, inflammation, and mild fibrosis associated with AFLD in rodents and human alcoholics. Ethanol exposure increases total lipin-1 expression (gene and protein) levels, causes cytosolic lipin-1 protein accumulation, induces PAP activity and TAG synthesis in mouse livers. Ethanol blocks lipin-1 nuclear entry and inhibits nuclear lipin-1-mediated fatty acid oxidation and disturbs VLDL secretion in mouse liver. Moreover, ethanol perturbs Lpin1 alternative splicing and subsequently increases ratio of Lpin1β/α via impairment of the SIRT1-SFRS10 axis. Ethanol induces production of a panel of proinflammatory cytokines by interfering with the lipin-1-NF-κB/NFATc4 axis. The net consequences of these alcohol mediated lipin-1 alterations is to promote hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in liver (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proposed role of lipin-1 in the development and progression of alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Abbreviations: Ac, acetylated; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; NFATc4, nuclear factor of activated T cells c4; mTORC1, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1; PAP, phosphatidate phosphatase; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PGC-1α, PPARγ co-activator-alpha; SREBP-1, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1; TG, triglyceride; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein.

The precise and detailed mechanisms by which ethanol affects the lipin-1-PAP activity, disturbs post-translational modifications of lipin-1 (e.g. acetylation, sumoylation, or phosphorylation), induces lipin-1 nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling and impairs co-regulator activity of nuclear lipin-1 remain to be elucidated. Given that lipin-1 is regulated by upstream signaling molecules, including miR-217, SIRT1, AMPK, SREBP-1, and adiponectin in cellular or animal models of AFLD, it will be of great importance to investigate the relationship with those molecules and explore whether there is potential feedback regulation via those signaling molecules, which can ultimately compromise lipin-1 functions (Figure 2). More importantly, exactly how ethanol deregulates the intracellular localization of lipin-1 will require to be further investigated.

Figure 2. Proposed mechanisms by which ethanol regulates hepatic lipin-1.

Abbreviations: AMPK, AMP-activated kinase; GCs, glucocorticoids; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NF-Y; nuclear factor-Y; PAP, phosphatidate phosphatase;SIRT1, Sirtuin 1; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SREBP-1, sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1

Lipin-1 acts as an important signaling molecule within the network of effects generated by ethanol in the liver. However, owing to the complex functionality of lipin-1, the detailed cellular and molecular signaling events of ethanol-mediated impairment of hepatic nuclear lipin-1 functions, and subsequent causes of fatty liver injury remain elusive. Considerable evidence over the past decades demonstrates that ethanol exposure causes development of steatosis, inflammation or fibrosis via disrupting multiple regulatory pathways of lipid metabolism and inflammatory processes (1–6). Such regulation involves impairment of a signaling network regulated by various important signaling molecules, including SIRT1, SREBP-1, AMPK, PGC-1α/PPARα, Forkhead box O (FoxO) and histones in rodents and in humans (2,3). Nevertheless, the central and crucial issue of how ethanol-mediated impairment of these signaling molecules ultimately leads to development and progression of AFLD has not been resolved. Therefore, whether and how lipin-1 may act as a crucial downstream regulator that is ultimately responsible for ethanol regulation of multiple hepatic signaling pathways, and AFLD warrants future investigations.

The existence of other members of the lipin family, including lipin-2 and lipin-3, are also likely to contribute to a complex regulatory mechanism in response to ethanol (6–8). As addressed above, the fld mice display fatty liver due to increased hepatic lipin-2-mediated PAP activity (8). Therefore, the effect of ethanol on hepatic lipin-2 or lipin-3 will need to be carefully evaluated in rodents or human alcoholics. It will also be of importance to explore the potential connections among lipin-1, lipin-2, and lipin-3 in the liver and whether and how ethanol perturbs the coordination of lipin family member’s network.

It is necessary to clarify the paradoxical interplay among ethanol-induced hepatic lipin-1-PAP activity, autophagy and AFLD. In addition to regulation of autophagy, lipin-1 has been implicated in circadian rhythms and ER stress response (80–82). Aberrant circadian rhythms and ER stress are associated with pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease (2,3,40,83–85).Therefore, it is worthwhile to explore whether and how ethanol-mediated disruption of lipin-1 functions contribute to disturbed circadian rhythms or ER stress response and subsequently contributes to development and progression of AFLD.

Despite the fact that synergistic effects of alcohol and obesity in liver injury in rodents and humans are well documented, the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms are still not fully understood. To date, there is little knowledge of ethanol, obesity or ethanol plus obesity’s effects on hepatic mRNA splicing enzymes, including SFRS10. Ethanol, obesity, or ethanol-obesity specifically and significantly inhibits hepatic SFRS10 expression, which leads to aberrant downstream lipin-1 mRNA splicing and exacerbated steatohepatitis in mice (18,19). The detailed signaling mechanisms connecting SIRT1 and SFRS10-lipin-1 axis and the modulation of the presumed SIRT1-SFRS10-lipin-1 axis by ethanol, obesity, or interaction of ethanol-obesity warrants additional investigation. Moreover, ethanol feeding studies with various genetically modified animal models, including tissue specific SIRT1, SFRS10, lipin-1 conditional knockout mice or transgenic mice will ultimately provide a clearer and a better mechanistic picture of the interplay of these signaling molecules with ethanol.

The clinical relevance of lipin-1 in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver diseases has been suggested by several lines of evidence. For example, the association of increased PAP activity in clinical patients with fatty liver disease. The impairment of mRNA levels of SIRT1, lipin-1 α, lipin-1β was found in human liver samples with alcoholic hepatitis (19–22). However, the gene expression of SIRT1 and lipin-1 in the livers of patients with alcoholic hepatitis are likely to correlate with liver disease severity. It will be necessary to further examine the protein expression and subcellular distribution of endogenous total lipin-1, PAP activity, lipin-1α, lipin-1β, SFRS10 and SIRT 1 in the livers of patients with mild to moderate alcoholic fatty liver injury, compared to healthy controls or patients with alcoholic hepatitis. A better knowledge of mechanism of regulation of lipin-1 by ethanol will undoubtedly help the development of novel pharmacological or nutritional reagents for treating patients with alcoholic steatosis/steatohepatitis.

Acknowledgments

Grants: This study was supported by grants from National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (AA013623 and AA015951 to M You), National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL103227 to Y Zhang) and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK095895 to Y Zhang), and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney diseases (DK093774 to YK Lee).

References

- 1.Rehm J, Shield KD. Global alcohol-attributable deaths from cancer, liver cirrhosis, and injury in 2010. Alcohol Res. 2013;35:174–183. doi: 10.35946/arcr.v35.2.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1572–1585. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.You M, Rogers CQ. Adiponectin: a key adipokine in alcoholic fatty liver. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:850–859. doi: 10.3181/0902-MR-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang HJ, Gao B, Zakhari S, Nagy LE. Inflammation in alcoholic liver disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2012;32:343–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basaranoglu M, Basaranoglu G, Sentürk H. From fatty liver to fibrosis: a tale of “second hit”. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1158–1165. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i8.1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csaki LS, Dwyer JR, Fong LG, Tontonoz P, Young SG, Reue K. Lipins, lipinopathies, and the modulation of cellular lipid storage and signaling. Prog Lipid Res. 2013;52:305–316. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris TE, Finck BN. Dual function lipin proteins and glycerolipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterfy M, Phan J, Xu P, Reue K. Lipodystrophy in the fld mouse results from mutation of a new gene encoding a nuclear protein, lipin. Nat Genet. 2001;27:121–124. doi: 10.1038/83685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han GS, Carman GM. Characterization of the human LPIN1-encoded phosphatidate phosphatase isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14628–14638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.117747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Péterfy M, Phan J, Reue K. Alternatively spliced lipin isoforms exhibit distinct expression pattern, subcellular localization, and role in adipogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32883–32889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pihlajamäki J, Lerin C, Itkonen P, Boes T, Floss T, Schroeder J, Dearie F, Crunkhorn S, Burak F, Jimenez-Chillaron JC, Kuulasmaa T, Miettinen P, Park PJ, Nasser I, Zhao Z, Zhang Z, Xu Y, Wurst W, Ren H, Morris AJ, Stamm S, Goldfine AB, Laakso M, Patti ME. Expression of the splicing factor gene SFRS10 is reduced in human obesity and contributes to enhanced lipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2011;14:208–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bou Khalil M, Sundaram M, Zhang HY, Links PH, Raven JF, Manmontri B, Sariahmetoglu M, Tran K, Reue K, Brindley DN, Yao Z. The level and compartmentalization of phosphatidate phosphatase-1 (lipin-1) control the assembly and secretion of hepatic VLDL. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:47–58. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800204-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Zhang J, Qiu W, Han GS, Carman GM, Adeli K. Lipin-1γ isoform is a novel lipid droplet-associated protein highly expressed in the brain. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1979–1984. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shen Z, Liang X, Rogers CQ, Rideout D, You M. Involvement of adiponectin-SIRT1-AMPK signaling in the protective action of rosiglitazone against alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G364–G374. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00456.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu M, Wang F, Li X, Rogers CQ, Liang X, Finck BN, Mitra MS, Zhang R, Mitchell DA, You M. Regulation of hepatic lipin-1 by ethanol: role of AMP-activated protein kinase/sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 signaling in mice. Hepatology. 2012;55:437–446. doi: 10.1002/hep.24708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin H, Hu M, Zhang R, Shen Z, Flatow L, You M. MicroRNA-217 promotes ethanol-induced fat accumulation in hepatocytes by down-regulating SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:9817–9826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.333534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu M, Yin H, Mitra MS, Liang X, Ajmo JM, Nadra K, Chrast R, Finck BN, You M. Hepatic-specific lipin-1 deficiency exacerbates experimental alcohol-induced steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology. 2013;58:1953–1963. doi: 10.1002/hep.26589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Everitt H, Hu M, Ajmo JM, Rogers CQ, Liang X, Zhang R, Yin H, Choi A, Bennett ES, You M. Ethanol administration exacerbates the abnormalities in hepatic lipid oxidation in genetically obese mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;304:G38–G47. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00309.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin H, Hu M, Liang X, Ajmo JM, Li X, Bataller R, Odena G, Stevens SM, Jr, You M. Deletion of SIRT1 from hepatocytes in mice disrupts lipin-1 signaling and aggravates alcoholic fatty liver. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:801–811. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brindley DN, Cooling J, Burditt SL, Pritchard PH, Pawson S, Sturton RG. The involvement of glucocorticoids in regulating the activity of phosphatidate phosphohydrolase, the synthesis of triacylglycerols in the liver Effects of feeding rats with glucose, sorbitol, fructose, glycerol, and ethanol. Biochem J. 1979;180:195–199. doi: 10.1042/bj1800195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Savolainen MJ, Baraona E, Pikkarainen P, Lieber CS. Hepatic triacylglycerol synthesizing activity during progression of alcoholic liver injury in the baboon. J Lipid Res. 1984;25:813–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson KJ, Venkatesan S, Martin A, Brindley DN, Peters TJ. Activity and subcellular distribution of phosphatidate phosphohydrolase (EC 3.134) in alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Effect of moderate alcohol consumption on liver enzymes increases with increasing body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1097–1103. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.4.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diehl AM. Obesity and alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol. 2004;34:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chronic ethanol consumption lessens the gain of body weight, liver triglycerides, and diabetes in obese ob/ob mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;331:23–34. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.155168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alcohol increases tumor necrosis factor alpha and decreases nuclear factor-kappab to activate hepatic apoptosis in genetically obese mice. Hepatology. 2005;42:1280–1290. doi: 10.1002/hep.20949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Synergistic steatohepatitis by moderate obesity and alcohol in mice despite increased adiponectin and p-AMPK. J Hepatol. 2011;55:673–682. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Auwerx J. Regulation of PGC-1α, a nodal regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001917. 884S-8890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pawlak M, Lefebvre P, Staels B. Molecular Mechanism of PPARα Action and its Impact on Lipid Metabolism, Inflammation and Fibrosis in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. J Hepatol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.039. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finck BN, Gropler MC, Chen Z, Leone TC, Croce MA, Harris TE, Lawrence JC, Jr, Kelly DP. Lipin 1 is an inducible amplifier of the hepatic PGC-1alpha/PPARalpha regulatory pathway. Cell Metab. 2006;4:199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fischer M, You M, Matsumoto M, Crabb DW. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) agonist treatment reverses PPARalpha dysfunction and abnormalities in hepatic lipid metabolism in ethanol-fed mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27997–28004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakajima T, Kamijo Y, Tanaka N, Sugiyama E, Tanaka E, Kiyosawa K, Fukushima Y, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Aoyama T. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha protects against alcohol-induced liver damage. Hepatology. 2004;40:972–980. doi: 10.1002/hep.20399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeon TI, Osborne TF. SREBPs: metabolic integrators in physiology and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peterson TR, Sengupta SS, Harris TE, Carmack AE, Kang SA, Balderas E, Guertin DA, Madden KL, Carpenter AE, Finck BN, Sabatini DM. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBPpathway. Cell. 2011;146:408–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakan I, Laplante M. Connecting mTORC1 signaling to SREBP-1 activation. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2012;23:226–234. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328352dd03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ji C, Chan C, Kaplowitz N. Predominant role of sterol response element binding proteins (SREBP) lipogenic pathways in hepatic steatosis in the murine intragastric ethanol feeding model. J Hepatol. 2006;45:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He L, Simmen FA, Ronis MJ, Badger TM. Post-transcriptional regulation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 by ethanol induces class I alcohol dehydrogenase in rat liver. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28113–28121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400906200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baumgardner JN, Shankar K, Korourian S, Badger TM, Ronis MJ. Undernutrition enhances alcohol-induced hepatocyte proliferation in the liver of rats fed via total enteral nutrition. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G355–G364. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00038.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.You M, Matsumoto M, Pacold CM, Cho WK, Crabb DW. The role of AMP-activated protein kinase in the action of ethanol in the liver. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1798–1808. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ji C, Kaplowitz N. Betaine decreases hyperhomocysteinemia, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and liver injury in alcohol-fed mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1488–1499. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Z, Gropler MC, Norris J, Lawrence JC, Jr, Harris TE, Finck BN. Alterations in hepatic metabolism in fld mice reveal a role for lipin 1 in regulating VLDL- triacylglyceride secretion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1738–1744. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.171538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kharbanda KK, Todero SL, Ward BW, Cannella JJ, 3rd, Tuma DJ. Betaine administration corrects ethanol-induced defective VLDL secretion. Mol Cell Biochem. 2009;327:75–78. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Z, Norris JY, Finck BN. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC1alpha) stimulates VLDL assembly through activation of cell death-inducingDFFA-like effector B (CideB) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25996–26004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.141598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berasain C, Goñi S, Castillo J, Latasa MU, Prieto J, Avila MA. Impairment of pre-mRNA splicing in liver disease: mechanisms andconsequences. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3091–3102. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i25.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elliott DJ, Best A, Dalgliesh C, Ehrmann I, Grellscheid S. How does Tra2β protein regulate tissue-specific RNA splicing? Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:784–788. doi: 10.1042/BST20120036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang HC, Guarente L. SIRT1 and other sirtuins in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2014;25:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li M, Lu Y, Hu Y, Zhai X, Xu W, Jing H, Tian X, Lin Y, Gao D, Yao J. Salvianolic acid B protects against acute ethanol-induced liver injury through SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of p53 in rats. Toxicol Lett. 2014;228:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nascimento AF, Ip BC, Luvizotto RA, Seitz HK, Wang XD. Aggravation of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by moderate alcohol consumption is associated with decreased SIRT1 activity in rats. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2013:252–259. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2013.07.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lehwald N, Tao GZ, Jang KY, Papandreou I, Liu B, Liu B, Pysz MA, Willmann JK, Knoefel WT, Denko NC, Sylvester KG. β-Catenin regulates hepatic mitochondrial function and energy balance in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:754–764. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang X, Hu M, Rogers CQ, Shen Z, You M. Role of SIRT1-FoxO1 signaling in dietary saturated fat-dependent upregulation of liver adiponectin receptor 2 in ethanol-administered mice. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:425–435. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shen Z, Ajmo JM, Rogers CQ, Liang X, Le L, Murr MM, Peng Y, You M. Role of SIRT1 in regulation of LPS- or two ethanol metabolites-induced TNF-alpha production in cultured macrophage cell lines. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1047–G1053. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00016.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ajmo JM, Liang X, Rogers CQ, Pennock B, You M. Resveratrol alleviates alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G833–G842. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90358.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lieber CS, Leo MA, Wang X, Decarli LM. Effect of chronic alcohol consumption on Hepatic SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li Y, Wang S, Ni HM, Huang H, Ding WX. Autophagy in alcohol-induced multiorgan injury: mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/498491. 498491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang P, Verity MA, Reue K. Lipin-1 regulates autophagy clearance and intersects with statin drug effects in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2014;20:267–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ding WX, Li M, Yin XM. Selective taste of ethanol-induced autophagy for mitochondria and lipid droplets. Autophagy. 2011 Feb;7(2):248–249. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.2.14347. Epub 2011 Feb 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ni HM, Du K, You M, Ding WX. Critical role of FoxO3a in alcohol-induced autophagy and hepatotoxicity. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1815–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hernández-Gea V, Hilscher M, Rozenfeld R, Lim MP, Nieto N, Werner S, Devi LA, Friedman SL. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induces fibrogenic activity in hepatic stellate cells through autophagy. J Hepatol. 2013;59:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin CW, Zhang H, Li M, Xiong X, Chen X, Chen X, Dong XC, Yin XM. Pharmacological promotion of autophagy alleviates steatosis and injury in alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver conditions in mice. J Hepatol. 2013;58:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Michot C, Mamoune A, Vamecq J, Viou MT, Hsieh LS, Testet E, Lainé J, Hubert L, Dessein AF, Fontaine M, Ottolenghi C, Fouillen L, Nadra K, Blanc E, Bastin J, Candon S, Pende M, Munnich A, Smahi A, Djouadi F, Carman GM, Romero N, de Keyzer Y, de Lonlay P. Combination of lipid metabolism alterations and their sensitivity to inflammatory cytokines in human lipin-1-deficient myoblasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832:2103–2114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takahashi N, Yoshizaki T, Hiranaka N, Suzuki T, Yui T, Akanuma M, Oka K, Kanazawa K, Yoshida M, Naito S, Fujiya M, Kohgo Y, Ieko M. Suppression of lipin-1 expression increases monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;415:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kim HB, Kumar A, Wang L, Liu GH, Keller SR, Lawrence JC, Jr, Finck BN, Harris TE. Lipin 1 represses NFATc4 transcriptional activity in adipocytes to inhibit secretion of inflammatory factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3126–3139. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01671-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meana C, Peña L, Lordén G, Esquinas E, Guijas C, Valdearcos M, Balsinde J, Balboa MA. Lipin-1 integrates lipid synthesis with proinflammatory responses during TLR activation in macrophages. J Immunol. 2014;193:4614–4622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ishimoto K, Nakamura H, Tachibana K, Yamasaki D, Ota A, Hirano K, Tanaka T, Hamakubo T, Sakai J, Kodama T, Doi T. Sterol-mediated regulation of human lipin 1 gene expression in hepatoblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:22195–22205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.028753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang P, O’Loughlin L, Brindley DN, Reue K. Regulation of lipin-1 gene expression by glucocorticoids during adipogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1519–1528. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800061-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manmontri B, Sariahmetoglu M, Donkor J, Bou Khalil M, Sundaram M, Yao Z, Reue K, Lehner R, Brindley DN. Glucocorticoids and cyclic AMP selectively increase hepatic lipin-1 expression, and insulin acts antagonistically. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1056–1067. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800013-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun X, Luo W, Tan X, Li Q, Zhao Y, Zhong W, Sun X, Brouwer C, Zhou Z. Increased plasma corticosterone contributes to the development of alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G849–G861. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00139.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu GH, Gerace L. Sumoylation regulates nuclear localization of lipin-1alpha in neuronal cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Rechem C, Boulay G, Pinte S, Stankovic-Valentin N, Guérardel C, Leprince D. Differential regulation of HIC1 target genes by CtBP and NuRD, via anacetylation/SUMOylation switch, in quiescent versus proliferating cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:4045–4059. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00582-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Eaton JM, Mullins GR, Brindley DN, Harris TE. Phosphorylation of lipin 1 and charge on the phosphatidic acid head group control its phosphatidic acid phosphatase activity and membrane association. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:9933–9945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Péterfy M, Harris TE, Fujita N, Reue K. Insulin-stimulated interaction with 14-3-3 promotes cytoplasmic localization of lipin-1 in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3857–3864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harris TE, Huffman TA, Chi A, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Kumar A, Lawrence JC., Jr Insulin controls subcellular localization and multisitephosphorylation of the phosphatidic acid phosphatase, lipin 1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:277–286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.You M, Considine RV, Leone TC, Kelly DP, Crabb DW. Role of adiponectin in the protective action of dietary saturated fat against alcoholic fatty liver in mice. Hepatology. 2005;42:568–577. doi: 10.1002/hep.20821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Correnti JM, Juskeviciute E, Swarup A, Hoek JB. Pharmacological ceramide reduction alleviates alcohol-induced steatosis and hepatomegaly in adiponectin knockout mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G959–G973. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00395.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nepal S, Park PH. Activation of autophagy by globular adiponectin attenuates ethanol-induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells: involvement of AMPK/FoxO3A axis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:2111–2125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mandal P, Roychowdhury S, Park PH, Pratt BT, Roger T, Nagy LE. Adiponectin and heme oxygenase-1 suppress TLR4/MyD88-independent signaling in rat Kupffer cells and in mice after chronicethanol exposure. J Immunol. 2010;185:4928–4937. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Phan J, Péterfy M, Reue K. Lipin expression preceding peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is critical for adipogenesis in vivo and in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29558–29564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Park BH, Qiang L, Farmer SR. Phosphorylation of C/EBPbeta at a consensus extracellular signal-regulated kinase/glycogen synthase kinase 3 site is required for the induction of adiponectin gene expression during the differentiation of mouse fibroblasts into adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8671–8680. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8671-8680.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yin H, Liang X, Ajmo JM, Finck B, You M. Adipocyte-Specific Lipin-1 Deficiency Disturbs Adiponectin Signaling and Aggrevates Alcoholic Fatty Liver in Mice. Hepatology. 2013;58:318A–319A. doi: 10.1002/hep.26589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gorné LD, Acosta-Rodríguez VA, Pasquaré SJ, Salvador GA, Giusto NM, Guido ME. The mouse liver displays daily rhythms in the metabolism of phospholipids and in the activity of lipid synthesizing enzymes. Chronobiol Int. 2014 doi: 10.3109/07420528.2014.949734. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Xu J, Lee WN, Phan J, Saad MF, Reue K, Kurland IJ. Lipin deficiency impairs diurnal metabolic fuel switching. Diabetes. 2006;55:3429–3438. doi: 10.2337/db06-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Takahashi N, Yoshizaki T, Hiranaka N, Suzuki T, Yui T, Akanuma M, Kanazawa K, Yoshida M, Naito S, Fujiya M, Kohgo Y, Ieko M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress suppresses lipin-1 expression in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;431:25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang T, Yang P, Zhan Y, Xia L, Hua Z, Zhang J. Deletion of circadian gene Per1 alleviates acute ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Toxicology. 2013;314:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Filiano AN, Millender-Swain T, Johnson R, Jr, Young ME, Gamble KL, Bailey SM. Chronic ethanol consumption disrupts the core molecular clock and diurnal rhythms of metabolic genes in the liver without affecting the suprachiasmatic nucleus. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71684. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kudo T, Tamagawa T, Shibata S. Effect of chronic ethanol exposure on the liver of Clock-mutant mice. J Circadian Rhythms. 2009;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1740-3391-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]