Abstract

Split-thickness skin grafting is a useful method of wound repair in burn and reconstructive operations. However, skin grafts require a donor site injury that creates a secondary wound at risk for delayed wound healing. Though in young healthy patients such donor sites have minimal risk, patients with risk factors for delayed wound healing are more challenging. We present a method for graft donor site management that offers an alternative to healing by secondary intention for patients with higher risk of poor wound healing. In those patients considered to be at high risk for donor site healing complications, we chose to treat the donor site with a split-thickness skin graft, or “graft back” procedure. An additional graft is taken adjacent to the initial donor site, and meshed 4:1 to cover both donor sites at once. Out of the 17 patients who received this procedure, 1 patient had a complication from the procedure that did not require an operation, and all patients appear to have good functional and cosmetic outcomes. No patients had any graft loss or graft infection. Histologic analysis showed complete epithelialization of the back-grafted area. The graft back method converts an open wound to a covered wound and may result in decreased wound healing time, improved cosmetic outcomes, and fewer complications, particularly in patients where wound healing is a concern. Importantly, it seems to have minimal morbidity. More detailed prospective studies are needed to ensure no additional risk is incurred by this procedure.

DONOR SITE MANAGEMENT

Management of the split-thickness skin graft (STSG) donor site has not been firmly established, and many practitioners have varying methods of caring for these wounds, ranging from different methods of back grafting to several different kinds of dressings.1–5 Donor site management can be especially challenging in patients where wound healing is likely to be compromised, such as in elderly or diabetic patients. Delayed wound healing of donor sites can be as high as 20% in elderly patients with skin graft donor sites.6 Age is a significant risk factor, with 85% of nonhealing wounds being in patients older than 65 years.7 One study cited 17% of patients receiving STSGs as above the age of 55 years, making age an important consideration when contemplating donor site management.8 Thompson9 was the first to describe the value of placing thin skin grafts on donor sites to improve healing. He noted that donor sites without any grafts had a propensity for hypertrophic scars that were cosmetically unfavorable, and that donor sites with thin grafts healed much more quickly and with better quality healing. This formation of hypertrophic scar is expected given that the body senses tension and tries to contract in response to an open wound.10

HYPERTROPHIC SCARRING

Hypertrophic scar formation is largely because of focal adhesions kinase (FAK) signaling causing excessive fibrosis. It has been shown that FAK signaling increased with mechanical force on a wound, and that inhibition of FAK signaling inhibits hypertrophic scar formation through this mechanism.10,11 Reducing the mechanical force on a wound by reducing the need to contract results in less hypertrophic scarring.12 Part of the goal of skin grafting is to reduce this mechanical load to allow for better wound healing. Wound inflammation, in general, through either tension, infection, or prolonged healing by second intention, has been shown to predispose to hypertrophic scar formation.13,14 A possible benefit of the “graft back” procedure is a reduction in all of these causes.

In addition to reducing the incidence of hypertrophic scarring, the type of dressing/coverage of a donor site can affect infection rate.15 There are obvious risks/disadvantages to leaving a donor site open, which is why many clinicians prefer the application of a dressing or cover to promote healing and reduce infection risk. Although many studies were small, one review of several studies comparing infection rates quoted the average infection rate of an exposed donor site at approximately 5%.15 The infection rate with a dressing/cover can vary widely with much higher or lower infection rates than exposed wounds depending on the material used.16,17

SKIN GRAFTING FOR DONOR SITE COVERAGE

The technique and mechanism of skin grafting using a meshed STSG at the site of injury is well established. Tanner et al18 first described these methods, and they have since become an integral aspect of grafting and the care of grafted wounds. Meshing a STSG allows for a limited surface area to be grafted and expanded to cover much larger wound areas than the donor site. It allows for rapid epithelialization of the wound and reduces fluid accumulation underneath the graft, enhancing the graft take and healing.18

Given the success of meshed STSG on graft sites and the relative lack of guidelines for donor site management, we sought a new method that combines these principles. In this article, we describe a method of STSG donor site management involving an identical graft harvested immediately adjacent to the primary graft donor site, meshing the graft 4:1, and placing it over both donor sites after extensive meshing to facilitate reepithelialization. This method might result in improved wound healing on the donor site with faster healing time, improved cosmetic outcome, and rapid epithelialization, although prospective studies are needed before definitive recommendations can be made. We believe that this method has particular value in patients in whom wound healing is likely to be a concern and ideally will prevent wound healing complications postoperatively.

METHODS

We retrospectively looked at 17 patients who had undergone this graft back procedure to evaluate the efficacy of this new method of donor site grafting. Many of the patients selected for this procedure were burn-injured patients with increased risk for poor wound healing of the donor site. These risk factors include age, diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, immunosuppression, calciphylaxis, malignancy, mixed connective tissue disorder, pain control concerns, or smoking. All patients were patients at level 1 trauma centers, and many had significant comorbidities in addition to age. These constellations of comorbidities we felt put these patients at an extreme risk for wound healing difficulties, which warranted this procedure.

The mechanism of donor site grafting in these patients of high risk was as follows: at the time of the grafting, a STSG is harvested in the usual manner, most frequently from the upper thigh, although any area of viable tissue is acceptable. The first STSG is then placed in its desired location for wound coverage. Attention is then turned to the donor site, where another, identically sized, STSG is taken immediately adjacent to the primary donor site. This STSG is harvested and then meshed at a 4:1 ratio. The graft is then placed over both STSG donor sites, covering the wound entirely (Figure 1). The graft is then affixed with interrupted 5-0 chromic sutures in the corners followed by spray thrombin/fibrinogen and then covered with a mepilex dressing for 5 to 7 days. After the procedure, patients were analyzed for wound healing complications. We defined complications as graft failure, hematoma, or infection at the donor site.

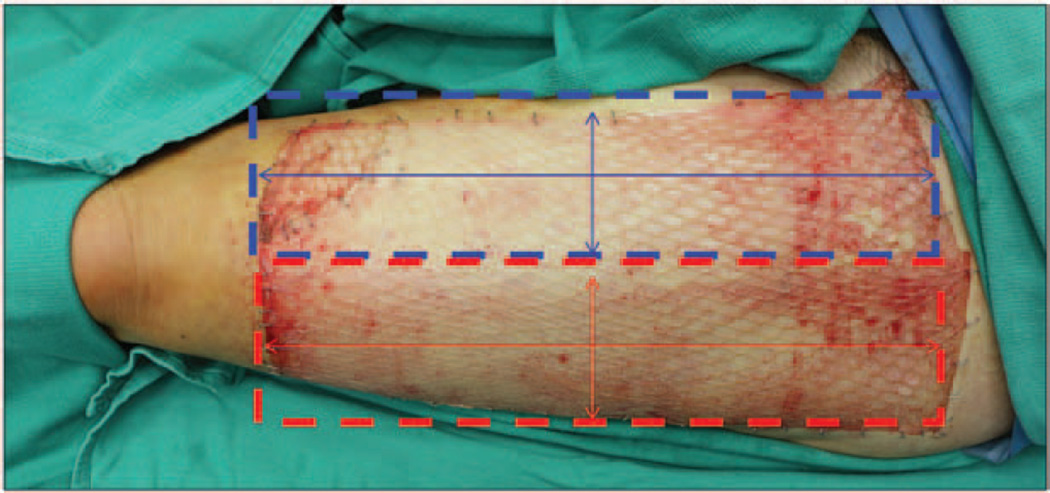

Figure 1.

Schematic demonstrating where grafts are taken on the thigh of a patient who received the “graft back” procedure. The initial donor site is identified in blue, and the “graft back” donor site is identified in red. In this photograph, the second graft (red) has been meshed and placed over both donor sites.

RESULTS

We performed a graft back on 17 patients. The average age of our cohort was 65 years with an average of four comorbidities (Table 1). All of the donor sites that were grafted back were on the thigh. Of the 17 patients selected to undergo this procedure, none have had any reported wound healing complications, including graft failure, hematoma, or infection. Early grafting has a somewhat meshed appearance and only requires a few tacking sutures or staples (Figure 2). Eventually, this meshed pattern improves significantly as the interstices fill in (Figure 3). One patient had postoperative bleeding from the donor site that required bedside intervention. Examination of the grafts postoperatively shows normal wound healing and graft acceptance. Histologic examination of the graft donor sites compared with native skin has demonstrated complete epithelialization of the wound with good result (Figure 4). Most notably, there is relatively equal thickness of epithelium in both specimens. Postoperatively, the graft heals well with acceptable cosmetic outcome (Figures 5 and 6).

Table 1.

Summary of the 17 Patients Included in This Study, Their Graft-Requiring Injury, Site of Graft Back, and Comorbidities

| Age (yr) |

Sex | Primary Injury |

Site of Graft Back |

Comorbidities/Complicating Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | F | Burn | Thigh | Chronic pain |

| 85 | F | Chronic venous s tasis ulcer |

Thigh | None |

| 54 | M | Calciphylaxis | Thigh | End-stage renal disease, calciphylaxis, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, gout, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation |

| 63 | F | Burn/thin skin | Thigh | Pulmonary embolism, hypertension, osteoarthritis, chronic pain syndrome, history of alcohol abuse, asthma, hemochromatosis, depression, sleep apnea, hyperlipidemia, GERD |

| 56 | M | Calciphylaxis | Thigh | Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with asplenia, coronary artery disease, end-stage renal disease secondary to systemic lupus erythematosus, calciphylaxis, severe aortic stenosis with valve replacement, hyperparathyroidism, medullary papillary thyroid cancer with thyroidectomy |

| 64 | M | Calciphylaxis | Thigh | Wegener’s granulomatosis, renal transplant, chronic pain syndrome, colovesicular fistula, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hyperthyroidism, gout |

| 79 | F | Burn | Thigh | Elderly |

| 57 | F | Chronic wound | Thigh | Mixed connective tissue disease with pulmonary hypertension, serositis, arthralgias, scleroderma, Raynaud’s disease, GERD, calcinosis, hypothyroidism, depression, previous tobacco use |

| 87 | M | Chronic wounds secondary to T-cell lymphoma |

Thigh | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, type 2 diabetes mellitus, pyoderma gangrenosum, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, chronic venous insufficiency |

| 86 | F | Burn | Thigh | Elderly, atrial fibrillation on coumadin, previous history of TIA, hypertension, congestive heart failure with last ejection fraction of 40%, anal melanoma with metastases, lyme disease |

| 24 | M | Burn | Thigh | Hypoplastic left heart with orthotopic heart transplant |

| 65 | M | Burn | Thigh | IV heroin and alcohol abuse, hepatitis B and C |

| 44 | F | Ischemic wounds | Thigh | Sepsis, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, and purpura fulminans |

| 57 | M | Burn | Thigh | Peripheral neuropathy |

| 64 | M | Burn | Thigh | Diabetic peripheral neuropathy |

| 71 | M | Burn | Thigh | COPD, diabetes mellitus |

| 85 | F | Burn | Thigh | Elderly, malnutrition |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; F, female; M, male; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Figure 2.

Photographs of the back-grafted area in a 65-year-old man intraoperatively (A) and 5 days postoperatively (B). The graft is held in place by tacking staples to cover as much area as possible.

Figure 3.

Serial photographs of a 24-year-old man with lower extremity burns 6 days postoperatively (A), 14 days postoperatively (B), 39 days postoperatively (C), and 159 days postoperatively (D). Note the initial obvious mesh pattern to the wound and significant improvement as the interstices heal in as well.

Figure 4.

Images (10× magnification) of the back-grafted donor site (A) and adjacent normal tissue (B) 5 months postoperatively. Note the lack of glands and completed epithelialization on the back-grafted tissue compared with normal tissue.

Figure 5.

Intraoperative photograph (A) of the placement of the 4:1 meshed graft on the donor site of a 71-year-old patient, and the same patient 1 month postoperatively (B). After 1 month, the graft has healed well and has had a good cosmetic result.

Figure 6.

Serial photographs of the same patient as in Figure 4 at both the wound graft site (A, B, C) and donor site (D, E, F) 4 days postoperatively (A, D), 1 month postoperatively (B, E), and 4 months postoperatively (C, F). Postoperatively, the wound graft site (B, C) and donor site (E, F) have healed well with good functional and cosmetic result.

DISCUSSION

There are many different options for management of the STSG donor site ranging from exposure to synthetic material or dressings, many of which are valid. The numerous options available for management allow each surgeon to have individual preferences and styles of how to manage the skin graft donor site. The overarching goal of the management of the STSG donor site is prevention of infection, minimize pain, and to preserve aesthetic appearance as much as possible. This is achieved by providing a moist wound environment, preventing disruption to allow for reepithelialization, and to ensure healing in the shortest period of time possible. Numerous comparisons have been made among various dressings and treatment options to evaluate these outcomes, but given the sheer number of dressing and treatment possibilities, it is difficult to compare all of them in a single study.5 The volume of different types of studies also makes establishing a baseline complication rate for donor site management impossible. Some studies comparing various dressings suggest options such as duoderm and Xeroform are among the best dressing options.19–23

Despite the number of studies regarding wound dressings, it is difficult to find studies discussing autologous grafts for management of donor sites. This is important given the potential for high donor site complication rates, ranging from 6 to 100% depending on the type of donor site.24–27 One study of 20 patients compared a living skin equivalent to autograft and polyurethane occlusive dressing for management of the STSG donor site and showed a living skin equivalent and autograft to be similar, and both superior to the polyurethane occlusive dressing.28 Other case reports have reported various methods of autologous grafting of the donor site, without reporting complication rates or other statistics.1,29 One case study describing an autologous grafting method used in 46 patients reported no complications in their cohort.3 However, more rigorous studies comparing autografting to donor site dressings are warranted given the theoretical benefits in certain situations of autologous grafting vs wound dressings related to wound healing. Additionally, variations of autografting the donor site have been reported, and it would be clinically useful to the practicing surgeon to know the comparisons of these treatment options to popular dressings.1,3,30

The method of grafting back the donor site presented in this article is a viable one with good results given that no complications have been reported in the patients receiving this treatment thus far and have had acceptable cosmetic and functional outcomes. We recommend adding this procedure to the trauma surgeon’s repertoire of skin graft donor site management for use in patients likely to have extreme wound healing difficulty. More studies are necessary to further evaluate the absolute complication rates and compare with dressing options, but with our initial sample, the complication rate seems to be lower than other methods of donor site management available. Comparison with a cohort of similarly aged and comorbid patients would strengthen our recommendation for this method of donor site management and is an area of future research. It is important to consider the utility of this method, as many of our patients with extreme comorbidities were able to heal well with this method.

The managing surgeon must also balance the considerations of additional grafting and wound creation with the perceived benefits of autologous donor site coverage to facilitate healing. Other methods of grafting, such as harvesting a thinner graft or grafting from an area with greater dermal thickness, are also valid considerations; however, our method presents an opportunity to consolidate both donor sites and provide autologous coverage via a single graft. In patients with sufficient intact soft tissue to permit this method, it seems to be a reasonable consideration for management of a STSG donor site.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we introduce a method to promote wound healing in STSG by including a second graft covering the donor site using a “graft back” method. In patients with increased risk for poor wound healing who undergo STSG for burns or graft-requiring injury, this approach should be considered. Further study is warranted to evaluate additional strengths and benefits of the back graft. However, in our experience, it results in improved healing and cosmetic appearance of the donor site without an increase in complications.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this was provided with the help of 1K08GM109105-01 and Plastic Surgery Foundation National Endowment Award.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ablaza VJ, Berlet AC, Manstein ME. An alternative treatment for the split skin-graft donor site. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21:207–209. doi: 10.1007/s002669900112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demirtas Y, Yagmur C, Soylemez F, Ozturk N, Demir A. Management of split-thickness skin graft donor site: a prospective clinical trial for comparison of five different dressing materials. Burns. 2010;36:999–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuenkongkaew T. Modification of split-thickness skin graft: cosmetic donor site and better recipient site. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;50:212–214. doi: 10.1097/01.SAP.0000029632.62669.CE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins L, Wasiak J, Spinks A, Cleland H. Split-thickness skin graft donor site management: a randomized controlled trial comparing polyurethane with calcium alginate dressings. Int Wound J. 2012;9:126–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voineskos SH, Ayeni OA, McKnight L, Thoma A. Systematic review of skin graft donor-site dressings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:298–306. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8072f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fatah MF, Ward CM. The morbidity of split-skin graft donor sites in the elderly: the case for mesh-grafting the donor site. Br J Plast Surg. 1984;37:184–190. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(84)90008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thourani VH, Ingram WL, Feliciano DV. Factors affecting success of split-thickness skin grafts in the modern burn unit. J Trauma. 2003;54:562–568. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000053246.04307.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson N. A clinical and histological investigation into the fate of epithelial elements buried following the grafting of “shaved” skin surfaces based on a study of the healing of split-skin graft donor sites in man. Br J Plast Surg. 1960;13:219–242. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(60)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong VW, Rustad KC, Akaishi S, et al. Focal adhesion kinase links mechanical force to skin fibrosis via inflammatory signaling. Nat Med. 2012;18:148–152. doi: 10.1038/nm.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen R, Zhang Z, Xue Z, et al. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) siRNA inhibits human hypertrophic scar by suppressing integrin α, TGF-β and α-SMA. Cell Biol Int. 2014;38:803–808. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliot D, Mahaffey PJ. The stretched scar: the benefit of prolonged dermal support. Br J Plast Surg. 1989;42:74–78. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(89)90117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edriss AS, Mesták J. Management of keloid and hypertrophic scars. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2005;18:202–210. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gauglitz GG, Korting HC, Pavicic T, Ruzicka T, Jeschke MG. Hypertrophic scarring and keloids: pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies. Mol Med. 2011;17:113–125. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rakel BA, Bermel MA, Abbott LI, et al. Split-thickness skin graft donor site care: a quantitative synthesis of the research. Appl Nurs Res. 1998;11:174–182. doi: 10.1016/s0897-1897(98)80296-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vartak AM, Keswani MH, Patil AR, Savitri S, Fernandes SB. Cellophane—a dressing for split-thickness skin graft donor sites. Burns. 1991;17:239–242. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(91)90113-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prasad JK, Feller I, Thomson PD. A prospective controlled trial of Biobrane versus scarlet red on skin graft donor areas. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1987;8:384–386. doi: 10.1097/00004630-198709000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanner JC, Jr, Vandeput J, Olley JF. The mesh skin graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1964;34:287–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masella PC, Balent EM, Carlson TL, Lee KW, Pierce LM. Evaluation of six split-thickness skin graft donor-site dressing materials in a swine model. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2013;1:e84. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brölmann FE, Eskes AM, Goslings JC, et al. REMBRANDT Study Group. Randomized clinical trial of donor-site wound dressings after split-skin grafting. Br J Surg. 2013;100:619–627. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malpass KG, Snelling CF, Tron V. Comparison of donor-site healing under Xeroform and Jelonet dressings: unexpected findings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:430–439. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000070408.33700.C7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haith LR, Stair-Buchmann ME, Ackerman BH, et al. Evaluation of Aquacel Ag for autogenous skin donor sites. J. Burn Care. Res. 2014 doi: 10.1097/BCR.0000000000000212. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feldman DL, Rogers A, Karpinski RH. A prospective trial comparing Biobrane, Duoderm and Xeroform for skin graft donor sites. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991;173:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samson MC, Morris SF, Tweed AE. Dorsalis pedis flap donor site: acceptable or not? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1549–1554. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199810000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richardson D, Fisher SE, Vaughan ED, Brown JS. Radial forearm flap donor-site complications and morbidity: a prospective study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:109–115. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199701000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirzabeigi MN, Wilson AJ, Fischer JP, et al. Predicting and managing donor-site wound complications in abdominally based free flap breast reconstruction: improved outcomes with early reoperative closure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:14–23. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim S, Chung SW, Cha IH. Full thickness skin grafts from the groin: donor site morbidity and graft survival rate from 50 cases. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;39:21–26. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2013.39.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muhart M, McFalls S, Kirsner RS, et al. Behavior of tissue-engineered skin: a comparison of a living skin equivalent, autograft, and occlusive dressing in human donor sites. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:913–918. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.8.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood RJ, Peltier GL, Twomey JA. Management of the difficult split-thickness donor site. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;22:80–81. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198901000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cirodde A, Leclerc T, Jault P, Duhamel P, Lataillade JJ, Bargues L. Cultured epithelial autografts in massive burns: a single-center retrospective study with 63 patients. Burns. 2011;37:964–972. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]