Abstract

We report the complete genome sequences of a buffalo coronavirus (BufCoV HKU26) detected from the faecal samples of two domestic water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in Bangladesh. They possessed 98–99% nucleotide identities to bovine coronavirus (BCoV) genomes, supporting BufCoV HKU26 as a member of Betacoronavirus 1. Nevertheless, BufCoV HKU26 possessed distinct accessory proteins between spike and envelope compared to BCoV. Sugar-binding residues in the N-terminal domain of S protein in BCoV are conserved in BufCoV HKU26.

Keywords: Coronavirus, water buffalo

Coronaviruses are classified into four genera, with bat coronaviruses known as the gene source of Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus, and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus [1], [2]. However, lineage A Betacoronavirus is unique among the genus in originating in rodents instead of bats [3]. Lineage A Betacoronavirus comprises several coronavirus species, including murine coronavirus, human coronavirus HKU1, Chinese Rattus coronavirus HKU24, rabbit coronavirus HKU14 and Betacoronavirus 1 [3], [4], [5]. Betacoronavirus 1 is best known for its tendency for recombination and interspecies transmission among various mammalian species [3], [6], [7]. In particular, human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV OC43) likely originated from a relatively recent zoonotic transmission event, with the most recent common ancestor of HCoV OC43 and bovine coronavirus (BCoV) dating to around 1890 [8]. Besides cattle, BCoV-like viruses have been detected in various ungulates, including water buffalo calves with gastroenteritis in Italy [9], [10]. However, only partial gene sequences, the longest one being ∼9.6 kb spanning ORF1b to nucleocapsid (N), were obtained from the buffalo viruses [9], [10].

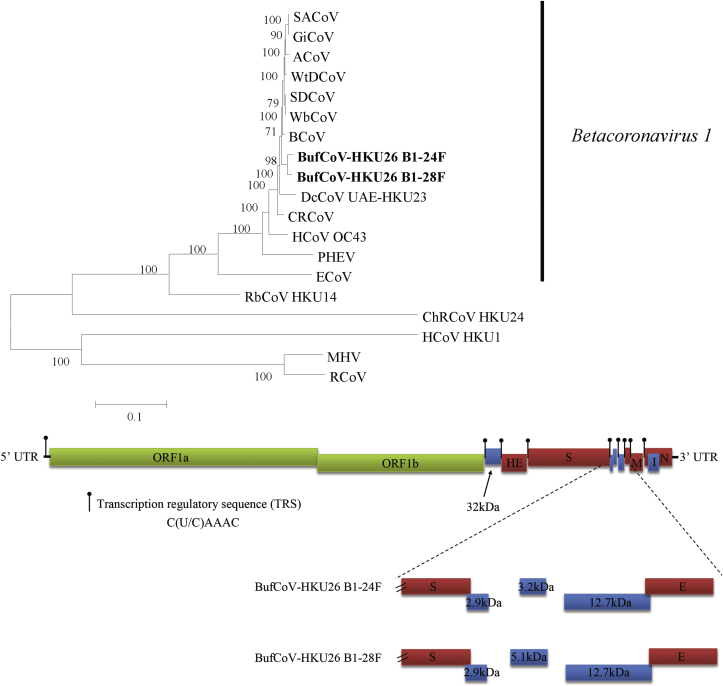

We report the complete genome sequences of a buffalo coronavirus (BufCoV HKU26) detected from the faecal samples of two domestic adult water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in Bangladesh. RT-PCR for coronavirus detection, and complete genome sequencing and analysis were performed as described previously [11], [12]. The genomes of BufCoV HKU26 strains B1-24F and B1-28F were 31 021 and 30 975 in length, with G+C content of 40%. They possessed 98–99% nucleotide identities to the genomes of BCoVs, supporting the classification of BufCoV HKU26 as a member of the species Betacoronavirus 1 (Fig. 1). The genome organization is also characteristic of lineage A Betacoronavirus, with the putative transcription regulatory sequence motif 5′-C(U/C)AAAC-3′ (Fig. 1). The two BufCoV HKU26 genomes encode five putative accessory proteins conserved among most members of Betacoronavirus 1, including a 32 kDa protein between ORF1ab and haemagglutinin-esterase, three proteins between spike (S) and envelope (E) and one internal protein overlapping with N. In BCoV, the three proteins between S and E were of typical size: 4.9, 4.8 and 12.8 kDa respectively. In BufCoV, the 4.9 kDa protein is replaced by a 2.9 kDa protein (25 aa) due to a premature stop codon. The 4.8 kDa protein of BufCoV HKU26 was also different from that of BCoVs, with a smaller protein of 29 aa in strain B1-24F and a protein of 44 aa in strain B1-28F due to a frameshift mutation caused by a single nucleotide deletion after the original start codon. Compared to other BCoV-like viruses, BufCoV HKU26 possessed a unique serine→asparagine substitution at position 354 of N protein. In contrast to murine coronavirus, which utilizes carcinoembryonic antigen–related cell adhesion molecule 1 as a receptor, BCoV and HCoV OC43 bind to N-acetyl-9-O acetyl neuraminic acid for cell entry [13], [14]. All the known critical and noncritical sugar-binding residues in the N-terminal domain of S protein in BCoV are conserved in BufCoV HKU26 [15]. The genome sequences of BufCoV HKU26 have been lodged at GenBank under accession numbers KU558922 and KU558923.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree constructed from complete genomes of BufCoV and other members of Betacoronavirus lineage A (top). Tree was constructed by maximum likelihood method using general-time-reversible model including proportion of invariable sites with gamma-distributed substitution rates and bootstrap values calculated from 100 trees. Betacoronavirus 1 indicated at right. Boldface type indicates 2 strains of BufCoV with complete genomes sequenced in this study. SACoV, sable antelope coronavirus (EF424621); GiCoV, giraffe coronavirus (EF424623); ACoV, alpaca coronavirus (DQ915164); WtDCoV, white-tailed deer coronavirus (FJ425187); SDCoV, sambar deer coronavirus (FJ425189); WbCoV, waterbuck coronavirus (FJ425186); BCoV, bovine coronavirus (DQ811784); BufCoV, buffalo coronavirus; DcCoV, dromedary camel coronavirus (KF906249); CRCoV, canine respiratory coronavirus (JX860640); HCoV OC43, human coronavirus OC43 (AY391777); PHEV, porcine haemagglutinating encephalomyelitis virus (DQ011855); ECoV, equine coronavirus (EF446615); RbCoV HKU14, rabbit coronavirus HKU14 (JN874559); ChRCoV, China Rattus coronavirus HKU24 (KM349742); HCoV HKU1, human coronavirus HKU1 (AY597011); MHV, murine hepatitis virus (FJ647223); RCoV, rat coronavirus (FJ938068). Genome organization of BufCoV (bottom). Position of transcriptional regulatory sequences of each gene is indicated. ORFs between spike (S) and envelope (E) gene are magnified to show differences between two BufCoVs. ORF1ab are represented by green boxes. Haemagglutinin-esterase (HE), S, E, membrane (M) and nucleocapsid (N) are represented by red boxes. Putative accessory proteins are represented by blue boxes.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the generous support of C. Yu, R. Yu, H. Hoy and H. Ming in the genomic sequencing platform. Supported in part by Theme-Based Research Scheme (project T11/707/15) and Research Grant Council Grant, University Grant Council; Strategic Research Theme Fund, University Development Fund and Special Research Achievement Award, The University of Hong Kong; and Croucher Senior Medical Research Fellowships.

Contributor Information

S.K.P. Lau, Email: skplau@hku.hk.

P.C.Y. Woo, Email: pcywoo@hku.hk.

References

- 1.de Groot R.J., Baker S.C., Baric R., Enjuanes L., Gorbalenya A., Holmes K.B. Coronaviridae. In: King A.M.Q., Adams M.J., Carstens E.B., Lefkowitz E.J., editors. Virus taxonomy, classification and nomenclature of viruses: ninth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, International Union of Microbiological Societies, Virology Division. Elsevier Academic Press; Amsterdam: 2011. pp. 806–808. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Lam C.S., Lau C.C., Tsang A.K., Lau J.H. Discovery of seven novel mammalian and avian coronaviruses in the genus deltacoronavirus supports bat coronaviruses as the gene source of alphacoronavirus and betacoronavirus and avian coronaviruses as the gene source of gammacoronavirus and deltacoronavirus. J Virol. 2012;86:3995–4008. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06540-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Li K.S., Tsang A.K., Fan R.Y., Luk H.K. Discovery of a novel coronavirus, China Rattus coronavirus HKU24, from Norway rats supports the murine origin of Betacoronavirus 1 and has implications for the ancestor of Betacoronavirus lineage A. J Virol. 2015;89:3076–3092. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02420-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Yip C.C., Fan R.Y., Huang Y., Wang M. Isolation and characterization of a novel Betacoronavirus subgroup A coronavirus, rabbit coronavirus HKU14, from domestic rabbits. J Virol. 2012;86:5481–5496. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06927-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Chu C.M., Chan K.H., Tsoi H.W., Huang Y. Characterization and complete genome sequence of a novel coronavirus, coronavirus HKU1, from patients with pneumonia. J Virol. 2005;79:884–895. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.884-895.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Wernery U., Wong E.Y., Tsang A.K., Johnson B. Novel betacoronavirus in dromedaries of the Middle East, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:560–572. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau S.K., Lee P., Tsang A.K., Yip C.C., Tse H., Lee R.A. Molecular epidemiology of human coronavirus OC43 reveals evolution of different genotypes over time and recent emergence of a novel genotype due to natural recombination. J Virol. 2011;85:11325–11337. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05512-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vijgen L., Keyaerts E., Moes E., Thoelen I., Wollants E., Lemey P. Complete genomic sequence of human coronavirus OC43: molecular clock analysis suggests a relatively recent zoonotic coronavirus transmission event. J Virol. 2005;79:1595–1604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1595-1604.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decaro N., Cirone F., Mari V., Nava D., Tinelli A., Elia G. Characterisation of bubaline coronavirus strains associated with gastroenteritis in water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) calves. Vet Microbiol. 2010;145:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decaro N., Martella V., Elia G., Campolo M., Mari V., Desario C. Biological and genetic analysis of a bovine-like coronavirus isolated from water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) calves. Virology. 2008;5(370):213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Li K.S., Huang Y., Wang M., Lam C.S. Complete genome sequence of bat coronavirus HKU2 from Chinese horseshoe bats revealed a much smaller spike gene with a different evolutionary lineage from the rest of the genome. Virology. 2007;367:428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau S.K., Woo P.C., Li K.S., Huang Y., Tsoi H.W., Wong B.H. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like virus in Chinese horseshoe bats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;27(102):14040–14045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506735102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vlasak R., Luytjes W., Spaan W., Palese P. Human and bovine coronaviruses recognize sialic acid–containing receptors similar to those of influenza C viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:4526–4529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams R.K., Jiang G.S., Holmes K.V. Receptor for mouse hepatitis virus is a member of the carcinoembryonic antigen family of glycoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:5533–5536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng G., Xu L., Lin Y.L., Chen L., Pasquarella J.R., Holmes K.V. Crystal structure of bovine coronavirus spike protein lectin domain. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:41931–41938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.418210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]