Abstract

A Turing mechanism implemented by BMP, SOX9 and WNT has been proposed to control mouse digit patterning. However, its generality and contribution to the morphological diversity of fins and limbs has not been explored. Here we provide evidence that the skeletal patterning of the catshark Scyliorhinus canicula pectoral fin is likely driven by a deeply conserved Bmp–Sox9–Wnt Turing network. In catshark fins, the distal nodular elements arise from a periodic spot pattern of Sox9 expression, in contrast to the stripe pattern in mouse digit patterning. However, our computer model shows that the Bmp–Sox9–Wnt network with altered spatial modulation can explain the Sox9 expression in catshark fins. Finally, experimental perturbation of Bmp or Wnt signalling in catshark embryos produces skeletal alterations which match in silico predictions. Together, our results suggest that the broad morphological diversity of the distal fin and limb elements arose from the spatial re-organization of a deeply conserved Turing mechanism.

Mouse digit patterning is controlled by a Turing network of Bmp, Sox9, and Wnt. Here, Onimaru et al. show that fin patterning in the catshark, Scyliorhinus canicula, is controlled by the same network with a different spatial organization; thus, the Turing network is deeply conserved in limb development.

Mouse digit patterning is controlled by a Turing network of Bmp, Sox9, and Wnt. Here, Onimaru et al. show that fin patterning in the catshark, Scyliorhinus canicula, is controlled by the same network with a different spatial organization; thus, the Turing network is deeply conserved in limb development.

Despite the remarkable diversity of animal shapes, the repertoire of genes used for morphogenesis is unexpectedly conserved between species—an observation termed deep homology1. How similar sets of genes can govern the generation of diverse morphologies during evolution, however, is still not well understood. The fin-to-limb transformation is a paradigmatic example of morphological evolution1. The distal skeletal patterns of vertebrate limbs and fins have changed multiple times during evolution (Fig. 1a), and their homologous relationships have been controversial2,3,4,5,6,7. According to comparative anatomy, digits are regarded as a novel structure of tetrapod limbs, and do not trace back to non-tetrapod sarcopterygian fins2,8 (for example, Sauripterus9 and Panderichthys7). Yet despite the clear skeletal differences, recent molecular studies show unexpected similarities between the distal fins and limbs at the genetic level. For example, the digit-specific regulatory sequence of the murine Hoxa and d genes has recently been found in the genomes of the skate and the spotted gar, where they also drive similar expression in the distal fin/limb bud6,10. Thus a deep question remains: how can the skeletal arrangement change so markedly, when the well-known patterning genes do not?

Figure 1. Time course of Sox9 expression in S. canicula pectoral fin buds reveals the distal spot pattern.

(a) Skeletal patterns of S. canicula pectoral fin, fossil fins7,9 and mouse limb. Red colours, distal elements. (b) Upper row shows OPT scans of Sox9 expression in S. canicula pectoral fin buds at stages 29–30. (Dorsal view; anterior is to the top, and distal is to the right). The corresponding lower panels indicate (in red) which part of the future skeleton is represented by the Sox9 pattern above. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Recent studies11,12 have provided strong evidence that digit patterning in the mouse limb is driven by a Turing mechanism, which has long been suggested theoretically13,14,15,16. Specifically, it has been proposed that regulatory interactions between BMP, SOX9 and WNT form a Turing network that creates a periodic molecular pre-pattern specifying the positions of the digits (the BSW model)12. A Turing model can generate different types of patterns, such as spots and stripes with only slight changes in parameter values. Therefore, we explored whether the BSW model could explain the marked changes in the distal skeletal arrangement of fins and limbs.

In this study, we focus on the pectoral fin development of the catshark, Scyliorhinus canicula for two reasons: (a) its fin skeletal elements are formed by individual condensations17, which are similar to the condensation process of tetrapod limbs; and (b) its genome is less derived than that of teleost genomes18. We show that spots of Sox9 expression underlie the distal elements of S. canicula pectoral fin buds. In addition, by building a computer model, we demonstrate that such spot-like Sox9 expression can be explained by the BSW model with slight modification of its parameters. Together, our results suggest that the broad morphological diversity of the distal fin and limb elements arose from the spatial re-organization of a deeply conserved Turing mechanism.

Results

The first periodic expression of Sox9 is a distal row of spots

To understand the dynamics of skeletal patterning in S. canicula pectoral fin buds, we first examined a time course of Sox9 expression using optical projection tomography (OPT)19. Our data revealed that the formation of distal nodular radials can indeed be captured in detail by Sox9 expression, which is initiated as a single row of spots along the anterior–posterior axis (Fig. 1b). In more detail: at early stages Sox9 starts to be expressed in the basal elements (Fig. 1b–i), and in the posterior-distal region (bracket in Fig. 1b–ii). Subsequently, a curved row of spots develop (arrowheads in Fig. 1b–iii), which is initially more continuous in the posterior region, but gradually also breaks up into spots (arrowheads in Fig. 1b–iv and v). These Sox9 spots can be identified as the second row of distal nodular elements of the final skeleton (see Supplementary Fig. 1a–c for the later stages and the detailed annotation). A previous study reported a roughly similar expression pattern for Sox8 (ref. 17), but distinct spots were hard to discern as a three-dimensional imaging technique (such as OPT) had not been used. Our data therefore reveals that the first stage of radial patterning is a dynamic specification of a spot-like pattern, in contrast to the stripy Sox9 pattern of the mouse limb bud. We thus focused our study on control of this spot pattern (rather than subsequent expression of Sox9 proximally or distally) for two reasons: firstly, we are interested in the initial symmetry-breaking process responsible for the overall radial arrangement, and secondly because previous studies suggest that the mechanism of patterning the distal periodic elements shows molecular differences from those controlling more proximal elements12,20.

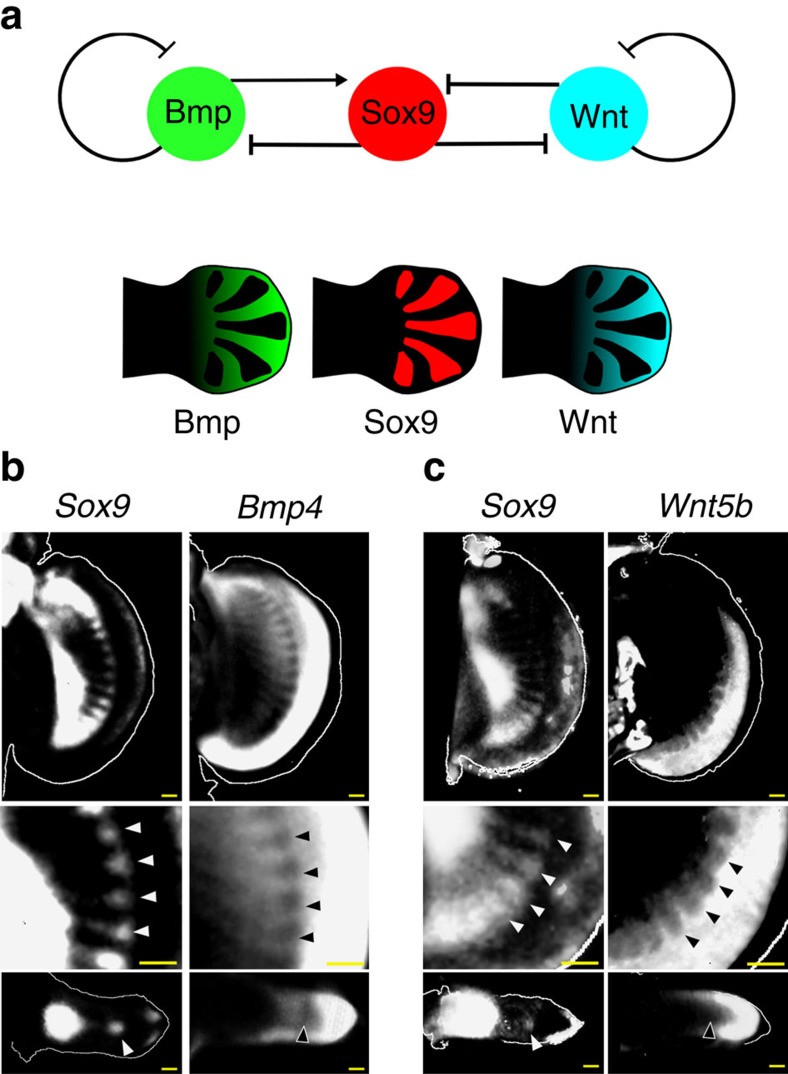

Out-of-phase patterns of Bmp and Wnt expression with Sox9

If the patterning of the S. canicula pectoral fin was controlled by a Turing system similar to that controlling mouse digit patterning12, Bmp and Wnt might be expressed or active in a pattern out-of-phase with Sox9 (Fig. 2a). We thus examined expression of Bmp- and Wnt-related genes in the S. canicula pectoral fin buds. Firstly, we found that Bmp2 was expressed only in the distal fin edges, whereas in mice it displays the strongest out-of-phase pattern with Sox9 (ref. 12) (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Instead, Bmp4 was expressed in the fin mesenchyme and indeed has a pattern complementary to Sox9 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2d; white and black arrowheads indicating a row of expression gaps where Sox9 has a row of spots). Next, we examined genes related to Wnt signalling (Supplementary Fig. 2b,c,e). Wnt5b had a pattern out-of-phase of Sox9 (Fig. 2c; Supplementary Fig. 2e), and a Wnt target gene Lef1 (ref. 21) also showed a shallow pattern complementary to Sox9 (Supplementary Fig. 2c). We also confirmed the complementary expressions by staining adjacent serial sections with either Sox9/Bmp4 or Sox9/Wnt5b (Supplementary Fig. 2f). Thus, although several differences were found, the overall relationship between Bmp, Sox9 and Wnt is conserved from fish to mammals.

Figure 2. Out-of-phase expression patterns of Bmp and Wnt with Sox9.

(a) The generic Turing network in mouse digit patterning, and distribution of Bmp expression (green), Sox9 expression (red) and Wnt signalling activity (blue). (b) Top row, OPT scans of gene expression patterns in the left and right pectoral fin buds of the same S. canicula embryo (stage 30). The Sox9 image has been horizontally flipped to aid comparison of the two expression patterns. The middle panels (below) show magnified views of the top panels, highlighting with arrowheads the spots of Sox9 expression and the corresponding gaps in the Bmp4 expression. The lower panels show perpendicular virtual sections of the same two fin buds (‘transverse' sections) revealing that both the Sox9 spot and the Bmp4 gap, are in the centre of the bud, matching the situation in the mouse. Dorsal is to the top. (c) The same analysis as (b) for the Wnt5b gene. Scale bars, 100 μm.

A dynamical model of S. canicula fin development

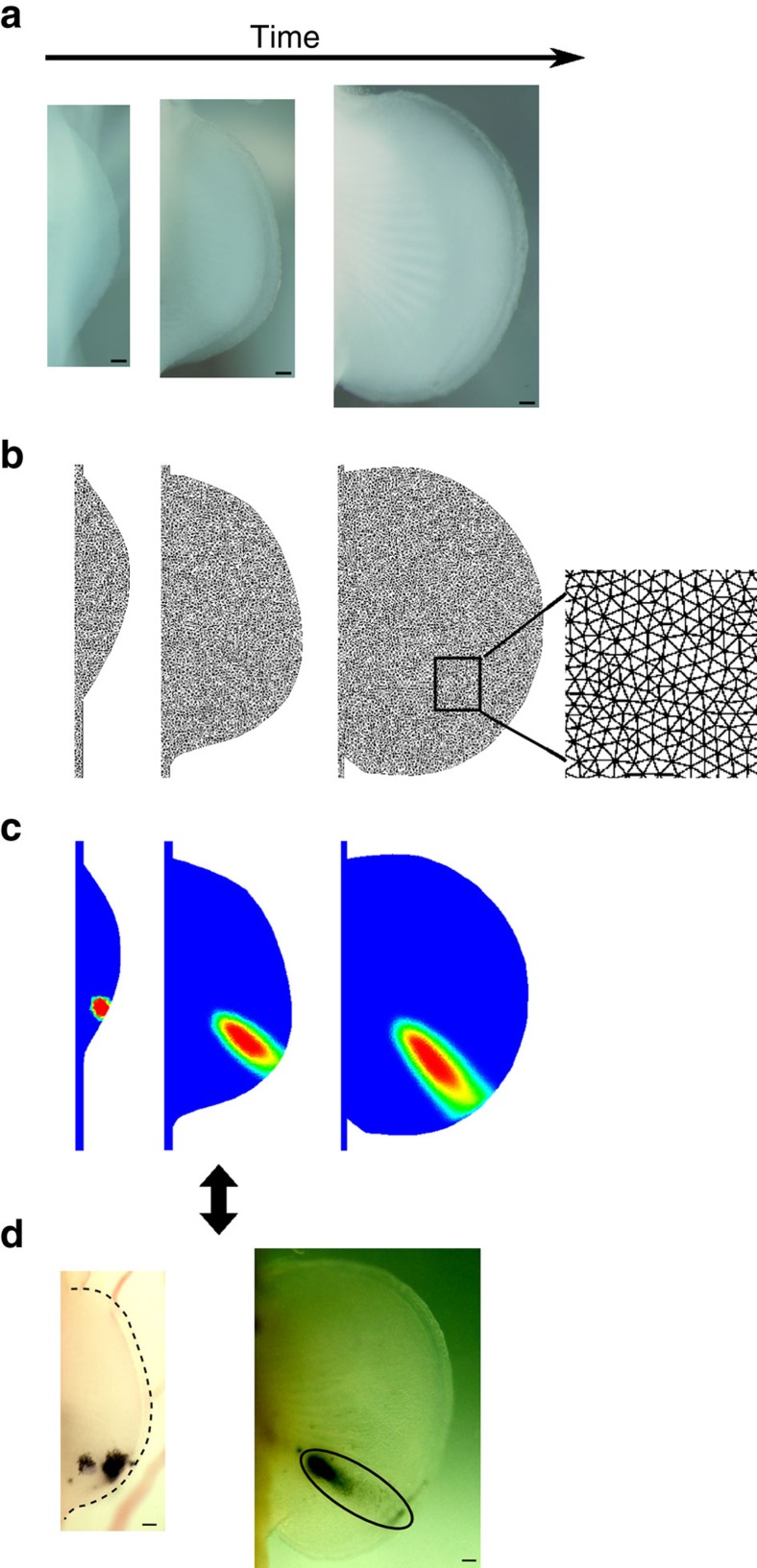

To confirm if a BSW Turing network could reproduce the early spot pattern of the S. canicula fin, we built a realistic computational model using a similar approach to our previous mouse limb model22. In particular, we obtained a time course of pectoral fin morphologies, created a series of two-dimensional (2D) triangular meshes, and calculated hypothetical tissue trajectories which represent possible growth maps (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. 3). A crucial step was to determine how to align the chronological series of fin shapes (Supplementary Fig. 4a). To constrain this configuration, we required real fate map data, and thus despite the very slow growth of S. canicula fins we performed carbon-particle-based fate mapping23 (which required a minimum of 30 days to observe sufficient displacement of labelled tissue). By comparing real tissue displacements with in silico predictions, we could derive a realistic computational growth map, in which the posterior part of pectoral fin bud expanded more than the anterior part (Supplementary Fig. 4b–e). Interestingly, the asymmetry in growth observed along anterior–posterior axis is consistent with the fate maps observed in chick limb buds24,25.

Figure 3. Construction of a fin growth model.

(a) Dorsal views of S. canicula pectoral fin buds from stages 26 to 32. Anterior is to the top. Outlines of these fin buds are used for the fin growth model. (b) The fin growth model from stage 26 to stage 31. The spatial domain at each time point is discretized by a fine triangular mesh (see magnified view in the oldest fin shape). (c) An example of virtual fate map analysis. A small group of triangular elements are labelled with a virtual dye (concentration equal to one) at the earliest stage and the fate of the dye is simulated using the sequence of deformations and interpolations of the growth model. (The probability distribution of ink concentration is shown from red (high) to blue (low)). (d) Hypothetical growth maps are then compared to real fate map analysis with Indian ink. Scale bars, 100 μm.

In silico modelling of the spot-type Sox9 expressions

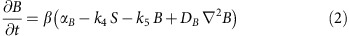

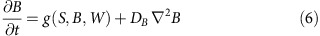

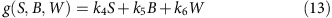

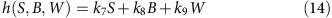

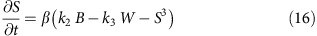

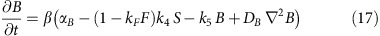

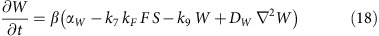

Because of the overall conservation of the distribution of Sox9, Bmp and Wnt, we next explored whether the S. canicula distal fin elements could also be specified by the BSW model12, which is expressed by the following partial differential equations:

|

|

|

where S, B and W are abstract variables representing the amounts of Sox9, Bmp and Wnt expression, respectively, k2 to k9 are kinetic parameters (Fig. 4a), DB and DW are diffusion constants of B and W, respectively, αB and αW are constant production terms of B and W, respectively, and β is a global coefficient that controls the speed of pattern appearance. This system is composed of one non-diffusive molecule, Sox9 (S) and two diffusive molecules, Bmp (B) and Wnt (W). Our numerical simulations revealed that the model formed spots instead of stripes when Wnt production was significantly higher than Bmp production (Supplementary Fig. 5a). When we simulated with this condition in the fin growth model, a uniform distribution of spots emerged that had no resemblance to the real Sox9 expression patterns (Supplementary Fig. 5a).

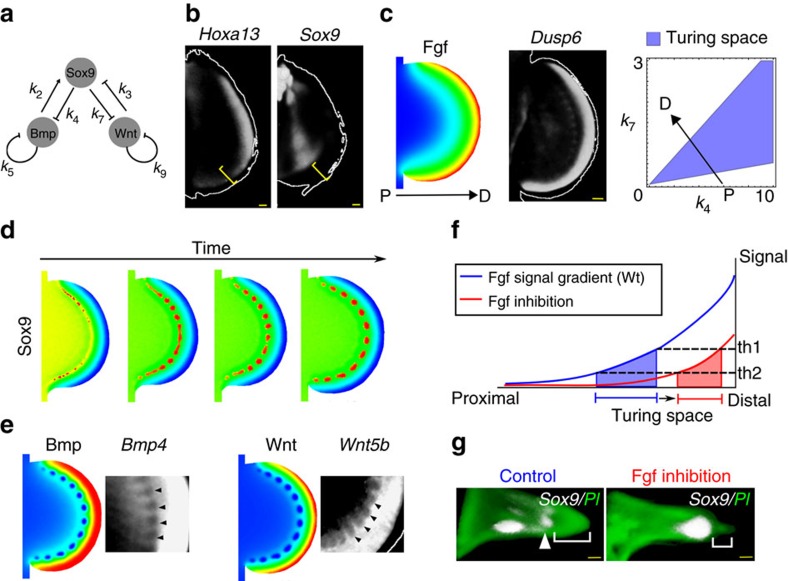

Figure 4. The in silico Turing model can reproduce the spot pattern of Sox9 expression.

(a) The generic Turing network model. (b) Hoxa13 and Sox9 expression in the right and left pectoral fin buds of the same embryo at stage 30. Yellow bracket: the distance of Sox9 expression from the fin edge, indicating non-significant overlap with Hoxa13. (c) The simulated Fgf gradient (left) corresponds well to the experimental expression pattern of an Fgf target gene, Dusp6 (centre). Right: parameter space of k4 and k7 (see a) indicates which combinations of parameter values lead to a Turing pattern (blue region). The arrow indicates how k4 and k7 change along the Fgf gradient, passing from low proximal Fgf (P) to high distal Fgf (D). This ensures that the spot pattern of Sox9 occurs only within a certain distance range from the AER. (d) The time course of a simulation result of the BSW model on the fin growth model. Red to blue colours indicate high to low concentrations of Sox9 (S). (e) The distribution of Bmp (B; left) and Wnt (W; right) concentration at the final time of the simulation matches the real expression patterns. In particular, shallow gaps of expression (black arrowheads) occur within a steep PD gradient. (f) Illustration of how Fgf inhibition changes the position of Turing space. Space is represented on the x axis, and the strength of Fgf signal on the y axis. A Turing pattern forms between the two threshold activity levels th1 and th2. When the normal Fgf signalling gradient (blue) is repressed (red), the position of the Turing pattern (shaded regions) shifts distally. (g) Virtual sections of S. canicula fin buds show Sox9 expression (white) in Control (DMSO, n=8/8) or Fgf inhibited (SU5402 n=7/12) experiments (stage 30). In the latter case the distance from distal Sox9 expression to the edge of the fin bud (square brackets) is reduced. Dorsal is up, distal is right. Green, nuclear staining with propidium iodide (PI). Arrowhead, the position of distal Sox9 expression. Scale bars, 100 μm.

Previous work in the mouse has shown that distal Hox genes and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signalling provide spatial modulation of the Turing network to sculpt the Sox9 pattern into the normal digit arrangement12. We thus hypothesized that these molecules could play in a role in shaping the Sox9 expression into a curved row of spots at a certain distance from the distal fin edge. In the mouse model, Hoxd13 restricts the domain where the Turing instability occurs. Because in S. canicula, Hoxa13 instead of Hoxd13 is significantly expressed in the distal fin buds17,26, we first examined Hoxa13 expression with OPT, but found that the Hoxa13 expression domain did not overlap significantly with the distal expression of Sox9 (Fig. 4b). Hence, we ruled out a similar role of Hoxa13 in S. canicula fin bud.

We therefore asked whether Fgf alone could control the Sox9 spot pattern. We simulated an Fgf gradient by assuming that the ligand is produced at the distal fin edge and diffused towards the proximal part (Fig. 4c). The shape of the resulting gradient was roughly similar to the expression domain of an Fgf target gene, Dusp6 (ref. 27) (Fig. 4c). Next, we assumed that the Fgf gradient modulated the BSW model by regulating the same parameters as in the mouse model—repressing k4 and boosting k7—which made the system pass through the Turing space from proximal to distal (Fig. 4c; and see Methods for the equations). When the BSW model was simulated under the influence of the Fgf gradient, a curved row of Sox9 spots was formed at a certain distance from the ectoderm (Fig. 4d). More specifically, the dynamic pattern shared two features with the observed time course: (a) it started at the anterior and posterior ends (which are also the more proximal positions) and gradually extended distally, and (b) it initially showed some connected regions of expression, which then broke up into a series of spots (compare Fig. 4d with Fig. 1b). To evaluate the role of growth in the model, we also simulated the BSW network on a static fin model, and found that without growth the Sox9 pattern broke into spots more slowly than with growth (Supplementary Fig. 5b), suggesting that growth may contribute to reliable spot separation. In addition, both Bmp and Wnt showed strong expression in the distal region and a series of expression gaps which correspond to the spots of Sox9 (Fig. 4e), consistent with the experimental data. The relatively shallow predicted interdigital Wnt distribution was also consistent with the real expression pattern of Wnt5b. Therefore, the model qualitatively reproduced the expression patterns of Sox9, Bmp4 and Wnt5b in S. canicula fin buds.

Our computer model reflects the normal Sox9 patterning, but could it correctly predict the main features of experimental perturbations? A clear prediction of the model is that if Fgf signalling is reduced, the position of Sox9 spot expressions will move closer to the distal fin edge (Fig. 4f). To test this prediction, we treated S. canicula embryos with the Fgf receptor inhibitor SU5402 (ref. 28), and confirmed the efficiency of inhibition by qPCR of the target gene Dusp6, Supplementary Fig. 5c). The resulting Sox9 pattern showed some variability (losing its periodic form and losing expression in the anterior fin—discussed further in the legend accompanying Supplementary Fig. 5d) but it was frequently shifted distally, consistent with the prediction (Fig. 4g; Supplementary Fig. 5d for details). Thus, the row of Sox9 expression spots appears to be positioned by Fgf signalling.

Experimental tests for in silico model predictions

We wished to test two other molecular perturbations: inhibitions of Bmp and Wnt, to see if our model predictions would match with in vivo experiments. Firstly, we performed numerical simulations with decreasing values of k2, which represents inhibition of Bmp signalling. The simulation showed two features: the distal-most Sox9 spots failed to form, and those which did form were smaller (compare Fig. 5b with Fig. 5a). To carry out experimental perturbations, we treated embryos with inhibitors about 4 days before the distal Sox9 expression appears, and checked the efficiency of inhibition by qPCR analysis and in situ hybridization on target genes (Supplementary Fig. 6a,b,c). Consistent with this prediction, S. canicula embryos treated with a Bmp inhibitor LDN-193189 (ref. 29) showed a loss of some or all of the Sox9 spots (compare Fig. 5d and e). To assess the skeletal patterns of Bmp inhibitor-treated embryos, we carried out longer treatments on embryos and cultured them more than 1 month. Interestingly, this long-term treatment sometimes resulted in an expansion of the apical ectodermal ridge-like structure and the width of the pectoral fin buds (Supplementary Fig. 6d), suggesting that the previously reported negative effect of Bmp on the chick AER30 is also conserved in catshark fin buds. Cartilage staining clearly showed that the posterior nodular elements were lost and sizes of the remaining spots were smaller (black arrowheads in Fig. 5h) than in control fins (Fig. 5g), as seen in the simulation.

Figure 5. The in silico model can predict phenotypes of in vivo perturbation.

(a) In silico simulation results of Sox9 (S) with the same parameter values as Fig. 4d. (b) To simulate inhibition of Bmp signalling we decreased k2 by 20% (as the LDN drug interferes with receptor binding). (c) To simulate inhibition of Wnt we decreased αW by 50% (as the C59 drug reduces secretion of Wnt protein). (d–i) In vivo Sox9 expression (d–f) and Alcian Blue stainings (AB; (g–i)) of pectoral fins treated with DMSO ((d,g) n=18/18 for Sox9 expression, n=3/3 for AB), Bmp inhibitor, LDN-193189 ((e,h) n=6/8 for Sox9 expression, n=2/2 for AB) and Wnt inhibitor, C59 ((f,i) n=10/10 for Sox9 expression, n=3/3 for AB). Arrowheads in h smaller nodular elements than those in the control. Arrowheads in i larger nodular elements than those in the control. Bracket in i a continuous nodular element. Scale bars, 100 μm.

We next examined Wnt inhibition. In the model, this perturbation was performed by decreasing the Wnt production term. The simulated Sox9 spots became partially fused into continuous regions, and those spots which did form were larger than in the control simulation (Fig. 5c). Consistent with this in silico prediction, treatment with a porcupine inhibitor C59, which inhibits Wnt secretion (thus Wnt production)31 also resulted in a partial or complete fusion of Sox9 into a continuous domain parallel to the distal fin edge of S. canicula embryos (Fig. 5f). The later cartilaginous patterns of treated fins also showed continuous or larger condensations (bracket and arrowheads in Fig. 5i)—again reflecting the simulation result. We thus found a high consistency between the model predictions and the phenotypes of in vivo experimental perturbations, and also a remarkable similarity in response to these inhibitors between catshark and mouse. Taken together, this suggests that the distal elements of S. canicula pectoral fins and mouse digits share a deeply conserved Turing system.

Discussion

In this study, we have provided experimental and theoretical evidence that a Bmp–Sox9–Wnt Turing network represents a new example of deep homology—underlying skeletal patterning all the way from sharks to mammals. The molecular details are not identical (for example the Bmp4 ligand is the stronger candidate in the catshark, while it is BMP2 in the mouse), however the most striking feature of our results is that in both species the same basic interactions are seen between Bmp, Wnt, Sox9 and Fgf. Furthermore, the experimental perturbations of Bmp and Wnt signalling closely mirror both the model predictions and the results from mouse experiments12. In S. canicula fin buds, Sox9 forms a spot-like pattern, which is different to the stripe-like pattern in mouse digits. However, our computer simulation reveals that the BSW network of the mouse digit patterning12 is also able to explain this spot pattern with just quantitative adjustments of its parameters. Therefore, relatively minor changes to the underlying deeply conserved network may be enough to trigger dramatic changes in skeletal arrangement.

Interestingly, teleosts seem not to use the BSW network (in zebrafish sox9a and b are expressed uniformly across the fin bud with no periodic pattern32, and bmp2a expression overlaps with sox9s (ref. 33)), and do not pattern their radials in the same manner (they produces a uniform endochondral disc, which is subsequently perforated to make the final skeletal pattern34). Although convergent or parallel evolution is theoretically possible—with a Turing network developing separately in cartilaginous fish and tetrapods—the most parsimonious explanation is that the BSW network was lost (or significantly altered) in the teleost lineage.

Although most components of the mouse BSW model appear to have conserved roles in the catshark (Bmp, Wnt, Sox9 and Fgf), the exception to this is the distal Hox genes, which play no role in our catshark model. This decoupling of the BSW network with the distal Hox genes is suggested by our observations and previous studies17,26 that Hox expression domains do not overlap with the Sox9 expressing region significantly (Fig. 4b), and is consistent with recently published results highlighting the differences in Hox gene regulation between tetrapods and fish. In tetrapod limbs, Hoxa and Hoxd genes are regulated by two distinct genomic domains: a 3′ domain regulating expression in the zeugopod and a 5′ counterpart controlling autopod expression3,31. Fish fins, by contrast, do not have such strict relationship between Hox gene regulations and their anatomical regions. Although a bimodal regulation has been found in fish fins3,6, the expression pattern of Hoxa13b in zebrafish, for example, is almost uniform35. Similarly, misexpression of the distal Hox genes also causes very different results: misexpression of Hoxd13 or a13 in chick limb buds results in a truncation of zeugopod elements36,37, while a similar experiment in zebrafish pectoral fin buds causes an increase of cartilage condensation in the distal region38. Thus, much experimental data supports the idea that while the Hox gene regulation and anatomical modules are strictly coupled in tetrapod limb development, this modular regulation is less strict in fish fin development. Elaboration of Hox gene regulation, suggested by many other studies3,10,38,39, may be relevant to coupling the interaction between Hox genes and the BSW network in the digit patterning.

We have focused here only on the distal nodular bone formation in S. canicula—because it is the first periodic pattern to form in the fin bud—and thus the mechanism of the proximal stripe formation remains to be addressed. Because the distal nodular elements are each connected with a proximal stripe element in adult catshark fins, one possibility is that the proximal elements are formed just by elongation of the distal Sox9 expression spots. Our Wnt inhibition experiments question this idea, as even when the distal Sox9 expression becomes continuous, the stripe elements are still formed (though they are thicker and fewer in number), suggesting that formation of the stripe elements is not totally dependent on the patterning of the distal nodular elements (Fig. 5i). This semi-independent nature of the distal and proximal elements implies that additional unknown molecular controls might contribute to patterning of the proximal regions. Nevertheless, the very periodic nature of this pattern suggests that even if different molecules are involved, Sox9 is likely patterned by a Turing-type mechanism, which may be related to the BSW model.

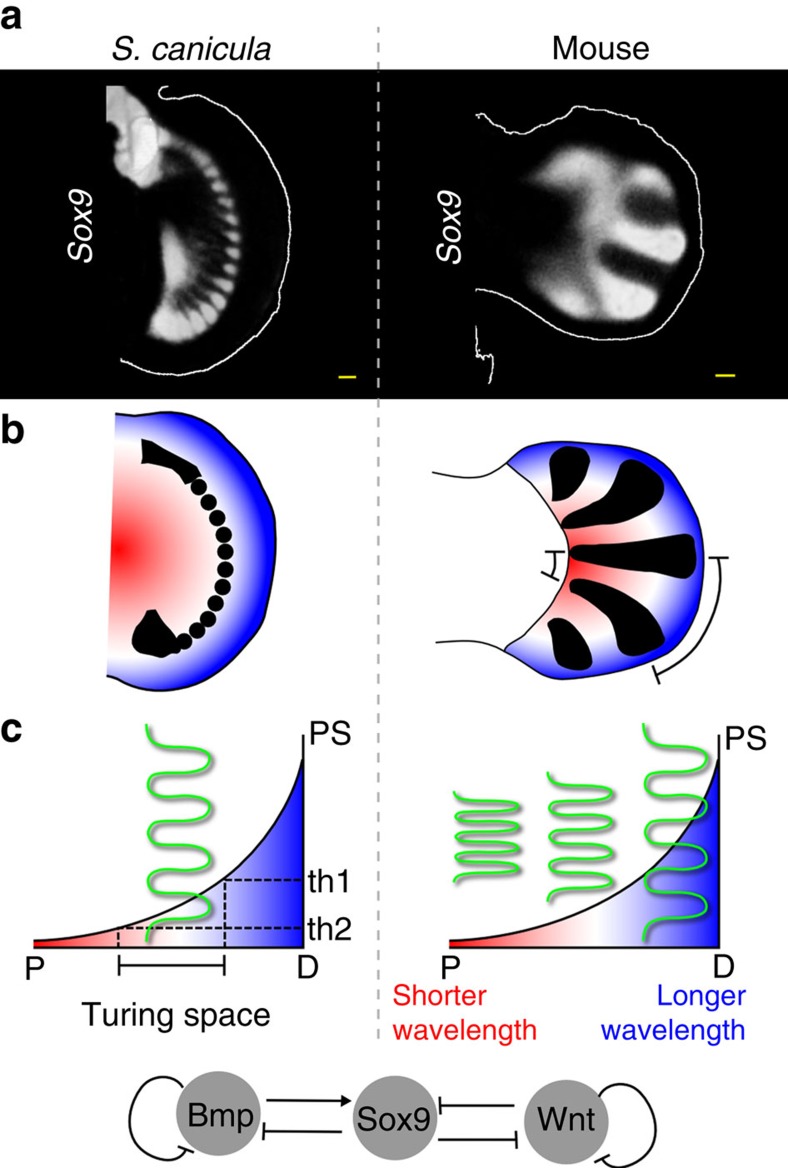

Finally, we propose that the changes in the fin and limb skeletal arrangement may have involved a change in the role of Fgf gradient for organizing the Sox9 expression patterns. In S. canicula Fgf appears to act as a positional cue40—positioning the row of Sox9 spots at a certain distance from, and therefore parallel to, the distal fin edge—while in the mouse it appears to align the digital stripes perpendicular to the distal limb edge, and to control the wavelength41 (Fig. 6). In the model, this dynamical difference can be explained by at least two parameters (Supplementary Fig. 7). One is the ratio between Wnt and Bmp production terms, which can change spots to stripes—also demonstrated by the Wnt inhibitor treatment in Fig. 5. The other is the inhibition of Sox9 by Wnt (k3), which affects the position of Turing space. Decreasing k3 results in a shift of Turing space to the distal edge, allowing it to form a pattern in the distal domain. In our computer model, these Wnt-related parameters are enough to change the role of Fgf gradient from positioning spots to aligning stripes. Biologically, FGF and WNT are known to have a synergetic repressive activity to Sox9 expression42. Therefore, we could speculate that this synergetic activity of Wnt and Fgf might be relatively stronger in the distal mesenchyme of catshark fin bud than in the mouse digit forming region. Although the real fin-to-limb transformation must have involved more complex processes, including fin/limb shape changes, anterior–posterior patterning changes43, the loss of actinotrichia proteins44, Hox gene regulation3,10,38,39 and others, our simple BSW model is nevertheless able to capture some key qualitative features of this morphogenetic change.

Figure 6. Comparison between fins and limbs.

(a) Sox9 expression patterns (white) in S. canicula pectoral fin bud at stage 30 and mouse digits at embryonic day 12. (b) Schematics of Sox9 expression (black) and proximal-distal positional information represented by a smooth gradient of colours from red to blue. Bracket: the large wavelength of Sox9 expression at the distal side of the mouse limb bud. (c) Two graphs illustrate the proposed difference in Fgf function between shark and mouse buds. In the case of S. canicula a Turing pattern (spots) can only form between the threshold values (th1 and th2). In the case of mouse a Turing pattern (stripes) forms along the whole gradient, and the Fgf signalling level instead influences the local wavelength. Space is represented on the x axis, and Fgf signalling (positional signal, PS) on the y axis. Green lines represent the Turing pattern. Bottom, the Turing network represented by this BSW model. Scale bars, 100 μm.

In conclusion, our study reveals that the morphological diversity of the distal fin and limb elements can be explained as the re-organization of a Turing patterning process. It highlights how relatively small regulatory changes can lead to major re-arrangements of the skeleton, and also emphasizes the difficulty of assigning homologous relationships between the distal elements of fins and limbs.

Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines for animal experiments of Tokyo Tech and CRG, and experiments involving mice were approved by animal ethics committees of CRG (JMC-07-1001P3-JS). Catshark (Scyliorhinus canicula) eggs were provided by A. Tweedale (Bangor university) and Station Biologique de Roscoff, France, and they were incubated at 16 °C in seawater and staged according to the standard staging system45. C52BL/6 (Charles River) mouse timed-pregnant females were sacrificed at different days after gestation E11.5. For in situ hybridization, embryos were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in 1 M phosphate-buffered saline, dehydrated in a graded methanol series, and stored in 100% methanol at −20 °C.

Gene isolation and in situ hybridization

Total RNA was extracted from stages 24 to 29 S. canicula embryos using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized by SuperScript III first strand (Invitrogen) and used as a template for PCR. To clone S. canicula genes, we used primers that were based on the nucleotide sequences found in the Elephant Shark Genome Project database (http://esharkgenome.imcb.a-star.edu.sg/)46 and SkateBase47,48 (http://skatebase.org/; Supplementary Table 1). The gene fragments were cloned into pBluescript SK—(Bmp2, Bmp4 and Dusp6) and pCR4 (Invitrogen; Lef1, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Id3, Nkd1 and Hoxa13), respectively. The partial coding sequences for Bmp2 (731 bp), Bmp4 (729 bp), Dusp6 (511 bp), Lef1 (907 bp), Wnt5a (1,031 bp), Wnt5b (1,156 bp), Id3 (635 bp), Nkd1 (804 bp), Eef1a1 (1,389 bp) and Hoxa13 (838 bp) of S. canicula have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers KT124217–KT124222, KU310672, KU310673, KU725979 respectively. Phylogenetic analysis was used to confirm the orthology of newly identified S. canicula genes (Supplementary Fig. 8). Amino-acid sequences were aligned using ClustalX and trimmed manually49. Phylogenetic trees of amino-acid sequence data sets were constructed with neighbour-joining method50 by MEGA5 (ref. 51). The cloned genes described above were used as templates for RNA probe synthesis. RNA probes of Sox9 (EU241880) of S. canicula and mouse Sox9 (NM_011448) respectively were synthesized as described43. Namely, the plasmid templates were amplified by PCR with T3/T7 or Sp6/T7 primer pairs, and transcribed by T3, T7 or Sp6 RNA polymerases (Roche). Whole-mount in situ hybridization was carried out with a standard protocol. Stained embryos were scanned with OPT as described19 and analysed with Volviewer52. And the colours of pictures were made grey scale with GIMP.

Chemical treatments

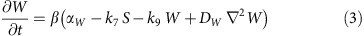

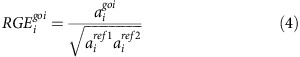

S. canicula embryos at early stage 30 were removed from the egg shells and cultured in 6-well plate with 2∼4 ml artificial seawater containing penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). SU5402 (Sigma), LDN-193189 (Stemgent) and C59 (Merck Millipore) were dissolved in DMSO as stock solutions. The embryos were treated with 100 μM SU5402, 50 μM LDN-193189, 20 μM C59, or indicated concentrations and 1% DMSO during 4 days and fixed for in situ hybridization analysis. We also analysed gene expressions 2 days after the treatments, but found no significant differences (Supplementary Fig. 6e). For qPCR analysis, the left and right pectoral fin buds of each inhibitor-treated embryos were dissected and pooled. RNA extraction was carried out with RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen), and cDNA synthesis was done with SuperScript III (Invitrogen). LightCycler 480 (Roche) and SYBR Green I (Roche) were used for the measurement of each gene expression amount. The qPCR primers were listed in Supplementary Table 1. Relative gene expressions were normalized by 18s rRNA and Eef1a1 of S. canicula with the following equation53:

|

where  is a relative gene expression amount of the gene of interest (goi) in sample i,

is a relative gene expression amount of the gene of interest (goi) in sample i,  is average of gene expression amount of goi in sample i, and

is average of gene expression amount of goi in sample i, and  and

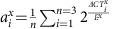

and  are averages of gene expression amount of ref1 (18S rRNA) and ref2 (Eef1a1) in sample i, respectively. Average of gene expression amount was calculated by

are averages of gene expression amount of ref1 (18S rRNA) and ref2 (Eef1a1) in sample i, respectively. Average of gene expression amount was calculated by  , where x is any gene,

, where x is any gene,  is a differential threshold cycle of gene x in sample i, and Ex is PCR efficiency of gene x. For cartilage staining, embryos were cultured with the chemicals for 20 days and additional 10–20 days with the normal artificial seawater. Before alcian blue staining, embryos were permealized by xylene and staining was carried out with a standard protocol.

is a differential threshold cycle of gene x in sample i, and Ex is PCR efficiency of gene x. For cartilage staining, embryos were cultured with the chemicals for 20 days and additional 10–20 days with the normal artificial seawater. Before alcian blue staining, embryos were permealized by xylene and staining was carried out with a standard protocol.

Fate map analysis

Eggs of S. canicula embryos around stages 26–28 were partially opened to label them with Indian ink (Pelican). To stop embryos from moving, eggs were cooled with iced seawater. Indian ink was injected into the pectoral fin buds with glass capillary, and the pictures were taken if applicable. After labelling the embryos, eggs were closed with plastic wraps and glue, and incubated in the artificial seawater containing penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco) for around 30 days. The labelled pectoral fin buds were scanned with OPT as described above. The images were manipulated with GIMP (the GNU Image Manipulation Program; http://www.gimp.org/).

In silico modelling

The technique for mouse limb modelling, which was implemented with Java22, was applied to the 2D fin growth model. Serial pictures of S. canicula pectoral fin buds were taken from stage 25 to stage 32 embryos (Supplementary Fig. 3a), and their outlines were converted into spline curves. Then the shapes between each key stage were calculated by interpolation with one day temporal resolution (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Each fin shape had an independent triangle mesh implemented by gmsh54 (Supplementary Fig. 3c). To carry out numerical simulations in the growing fin model, each mesh transmits information of species' concentrations to the next mesh. When a mesh was deformed to match the next shape, concentration of a triangle in the deformed mesh is split into the overlapping triangles of the next mesh (as previously described22). This implementation also allows virtual fate map analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3d). We are happy to supply the code on request.

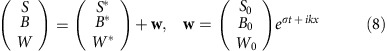

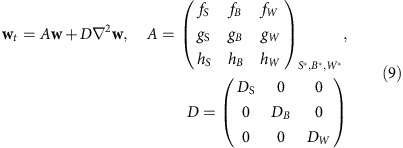

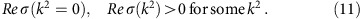

Mathematical analysis and numerical simulation

Mathematical analysis of Turing space and numerical simulations were carried out in conditions previously described12,55, in particular using the linear stability analysis described in White and Gilligan55. We considered the following general reaction-diffusion equations for Bmp (B), Sox9 (S) and Wnt (W):

|

|

|

where DS, DB and DW are diffusion constants of S, B and W respectively. To linearize them about the steady state (S*, B*, W*), we set

|

where S0, B0 and W0 are constants, k is the wavenumber and σ can either be a real number or a complex number. For |w| small, the equations (5)–(7), , becomes

|

where A is the Jacobian matrix at the steady state, and f, g and h are the partial derivatives of the indicated variables. For nontrivial solutions, the σ is determined by the roots of the characteristic polynomial

|

Turing instability requires

|

We implemented a simple linear model:

|

|

|

where k1 to k9 are kinetic parameters representing regulatory interactions between genes. As described previously12, under DS=0, k1=k6=k8 =0, k2>0, k3<0, k5=k9<0, we obtained the following inequality by solving (10) and (11) with Mathematica (Wolfram):

|

This inequality was used for determining the Turing space in Fig. 4c (parameter values were β=1, k2=1, k3 =1, k5 =0.1, DB=160, DW=25). For numerical simulations, partial differential equations (PDEs) were solved by PDE solver written in Java with Huen method. Time step was 0.002. The finite volume method was used to calculate the amount of diffusion between neighbouring triangles. Zero-flux boundary condition was used in all simulations. Initial conditions were set as homogeneous steady states of each species. 1% of Gaussian multiplicative noise was added at each time step. Simulations were carried out from stage 29 to stage 31. Equations (1)–(3), , were used in Supplementary Fig. 5a. Parameter values were β=1, k2=1, k3=1, k4=1, k7=1, k5 =0.1, k9 =0.1, DB=160, DW=25. αB and αW were spatially varied from 0 to 2. The equations used in Figs 4 and 5 and Supplementary Fig. 5b are:

|

|

|

where F is the Fgf gradient defined below and kF is a constant. Parameter values were β=8, k2=1, k3=3, k4=6, k7=2.4, k5=0.1, k9=0.1, kF=0.667, DB=160, DW=25, αB=0.1 and αW=1.2. The Fgf gradient (F) was created with the following equation and normalized between 0 and 1:

|

where the decay rate, μF=0.1 and the diffusion constant, DF=600. αF is a local production from the fin edge where apical ectodermal ridge is formed in S. canicula fin buds. For the simulations on squares in Supplementary Fig. 7, the Fgf gradient was substituted to e−3x (0≤x≤1).

Additional information

Accession codes: Sequences for newly identified genes have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers KT124217 to KT124222, KU310672, KU310673, KU725979.

How to cite this article: Onimaru, K. et al. The fin-to-limb transition as the re-organization of a Turing pattern. Nat. Commun. 7:11582 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11582 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-8, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Tweedale and Station Biologique de Roscoff for collecting S. canicula embryos; L. Quintana, A. Robert-Moreno and J. Raspopovic for technical advice; X. Diego-Iñiguez and K. Wotton for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, through ‘Centro de Excelencia Severo Ochoa 2013–2017', SEV-2012-0208, and the Plan Nacional grant BFU2010-16428 and BFU2015-68725-P (co-financed by FEDER funds of the European commissions) to K.O., L.M., M.M. and J.S., and by ICREA to J.S. and in part by the Global COE Program ‘Evolving Education and Research Center for Spatio-Temporal Biological Network' from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and the Program for Leading Graduate Schools ‘Education Academy of Computational Life Sciences' from the MEXT to K.O. and M.T., the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 25291086 and the Inamori Foundation to M.T.

Footnotes

Author contributions K.O., L.M., M.T. and J.S. designed the project. K.O., L.M. and J.S. wrote the manuscript. K.O. performed experiments with catshark embryos and simulations. L.M. performed mathematical analysis and Java programming for simulations. M.M. performed interpolation of fin shapes.

References

- Shubin N., Tabin C. & Carroll S. Deep homology and the origins of evolutionary novelty. Nature 457, 818–823 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clack J. A. The fin to limb transition: new data, interpretations, and hypotheses from paleontology and developmental biology. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 37, 163–179 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Woltering J. M., Noordermeer D., Leleu M. & Duboule D. Conservation and divergence of regulatory strategies at hox loci and the origin of tetrapod digits. PLoS Biol. 12, e1001773 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. C., Dahn R. D. & Shubin N. H. An autopodial-like pattern of Hox expression in the fins of a basal actinopterygian fish. Nature 447, 473–476 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson Z. et al. Fish fingers: digit homologues in Sarcopterygian fish fins. J. Exp. Zool. Part B Mol. Dev. Evol. 308, 757–768 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrke A. R. et al. Deep conservation of wrist and digit enhancers in fish. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 803–808 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert C. A., Mark-Kurik E. & Ahlberg P. E. The pectoral fin of Panderichthys and the origin of digits. Nature 456, 636–638 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates M. The evolution of paired fins. Theor. Biosci. 122, 266–287 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. C., Shubin N. H. & Daeschler E. B. A new specimen of Sauripterus taylori (Sarcopterygii, Osteichthyes) from the Famennian Catskill Formation of North America. J. Vert. Paleontol. 24, 26–40 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Schneider I. et al. Appendage expression driven by the Hoxd Global Control Region is an ancient gnathostome feature. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 12782–12786 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth R. et al. Hox genes regulate digit patterning by controlling the wavelength of a Turing-type mechanism. Science 338, 1476–1480 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raspopovic J., Marcon L., Russo L. & Sharpe J. Digit patterning is controlled by a Bmp-Sox9-Wnt Turing network modulated by morphogen gradients. Science 345, 566–570 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. A. & Frisch H. L. Dynamics of skeletal pattern formation in developing chick limb. Science 205, 662–668 (1979). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T., Shiota K., Morriss-Kay G. & Maini P. K. Mixed-mode pattern in Doublefoot mutant mouse limb-Turing reaction-diffusion model on a growing domain during limb development. J. Theor. Biol. 240, 562–573 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Zhang Y. T., Alber M. S. & Newman S. A. Bare bones pattern formation: A core regulatory network in varying geometries reproduces major features of vertebrate limb development and evolution. PLoS ONE 5, (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turing A. M., Transactions P., Society R., Sciences B. & Turing B. Y. A. M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 237, 37–72 (1952). [Google Scholar]

- Freitas R., Zhang G. & Cohn M. J. Biphasic Hoxd gene expression in shark paired fins reveals an ancient origin of the distal limb domain. PLoS ONE 2, e754 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renz A. J., Meyer A. & Kuraku S. Revealing less derived nature of cartilaginous fish genomes with their evolutionary time scale inferred with nuclear genes. PLoS ONE 8, e66400 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe J. et al. Optical projection tomography as a tool for 3D microscopy and gene expression studies. Science 296, 541–545 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benazet J.-D. et al. Smad4 is required to induce digit ray primordia and to initiate the aggregation and differentiation of chondrogenic progenitors in mouse limb buds. Development 139, 4250–4260 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atcha F. A., Munguia J. E., Li T. W. H., Hovanes K. & Waterman M. L. A new beta-catenin-dependent activation domain in T cell factor. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 16169–16175 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcon L., Arqués C. G., Torres M. S. & Sharpe J. A computational clonal analysis of the developing mouse limb bud. PLoS Comp. Biol. 7, e1001071 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muneoka K., Wanek N. & Bryant S. V. Mammalian limb bud development: in situ fate maps of early hindlimb buds. J. Exp. Zool. 249, 50–54 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura N., Yokoyama H. & Tamura K. Altered developmental events in the anterior region of the chick forelimb give rise to avian-specific digit loss. Dev. Dyn. 243, 741–752 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M. et al. Fin development in a cartilaginous fish and the origin of vertebrate limbs. Nature 416, 527–531 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K. et al. Heterochronic shift in Hox-mediated activation of Sonic hedgehog leads to morphological changes during fin development. PLoS ONE 4, e5121 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eblaghie M. C. et al. Negative feedback regulation of FGF signaling levels by Pyst1/MKP3 in chick embryos. Curr. Biol. 13, 1009–1018 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi M. et al. Structures of the tyrosine kinase domain of fibroblast growth factor receptor in complex with inhibitors. Science 276, 955–960 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P. B. et al. BMP type I receptor inhibition reduces heterotopic ossification. Nat. Med. 14, 1363–1369 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizette S. & Niswander L. BMPs negatively regulate structure and function of the limb apical ectodermal ridge. Development 126, 883–894 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt K. D. et al. Pharmacological inhibition of the Wnt acyltransferase PORCN prevents growth of WNT-driven mammary cancer. Cancer Res. 73, 502–507 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Y.-L. et al. A pair of Sox: distinct and overlapping functions of zebrafish sox9 co-orthologs in craniofacial and pectoral fin development. Development 132, 1069–1083 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse B. & Thisse C. High throughput expression analysis of ZF-models consortium clones. ZFIN Direct Data Submission (2005). Available at http://zfin.org/cgi-bin/webdriver?MIval=aa-pubview2.apg&OID=ZDB-PUB-051025-1.

- Grandel H. & Schulte-Merker S. The development of the paired fins in the Zebrafish (Danio rerio). Mech. Dev. 79, 99–120 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn D. & Ho R. K. Tri-phasic expression of posterior Hox genes during development of pectoral fins in zebrafish: implications for the evolution of vertebrate paired appendages. Dev. Biol. 322, 220–233 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff D. J. & Tabin C. J. Analysis of Hoxd-13 and Hoxd-11 misexpression in chick limb buds reveals that Hox genes affect both bone condensation and growth. Development 124, 627–636 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokouchi Y. et al. Misexpression of HoxA-13 induces cartilage homeotic transformation and changes cell adhesiveness in chick limb buds. Genes Dev. 9, 2509–2522 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas R., Gómez-Marín C., Wilson J. M., Casares F. & Gómez-Skarmeta J. L. Hoxd13 contribution to the evolution of vertebrate appendages. Dev. Cell 23, 1219–1229 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amemiya C. T. et al. The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolution. Nature 496, 311–316 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert L. Positional information and the spatial pattern of cellular differentiation. J. Theor. Biol. 25, 1–47 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J. B. A. & Sharpe J. Positional information and reaction-diffusion: two big ideas in developmental biology combine. Development 142, 1203–1211 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Berge D., Brugmann S. A., Helms J. A. & Nusse R. Wnt and FGF signals interact to coordinate growth with cell fate specification during limb development. Development 135, 3247–3257 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onimaru K. et al. A shift in anterior–posterior positional information underlies the fin-to-limb evolution. eLIFE 4, e07048 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. Loss of fish actinotrichia proteins and the fin-to-limb transition. Nature 466, 234–237 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard W. W., Mellinger J. & Lechenault H. A series of normal stages for development of Scyliorhinus canicula, the lesser spotted dogfish (Chondrichthyes: Scyliorhinidae). J. Exp. Zool. 267, 318–336 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh B. et al. Elephant shark genome provides unique insights into gnathostome evolution. Nature 505, 174–179 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyffels J. et al. SkateBase, an elasmobranch genome project and collection of molecular resources for chondrichthyan fishes. F1000Res. 3, 191 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. et al. Community annotation and bioinformatics workforce development in concert--Little Skate Genome Annotation Workshops and Jamborees. Database 2012, bar064 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F. & Higgins D. G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N. & Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. 28, 1530–1534 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. et al. Visualizing plant development and gene expression in three dimensions using optical projection tomography. Plant Cell 18, 2145–2156 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellemans J., Mortier G., De P. A., Speleman F. & Vandesompele J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol. 8, R19 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geuzaine C. & Remacle J.-F. Gmsh: a three-dimensional finite element mesh generator with built-in pre- and post-processing facilities. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng 79, 1309–1331 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- White K. A. J. & Gilligan C. A. Spatial heterogeneity in three-species, plant-parasite-hyperparasite, systems. Phil.Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 353, 543–557 (1998). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-8, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary References