Abstract

Senecavirus A (SVA) is an emerging picornavirus that has been recently associated with an increased number of outbreaks of vesicular disease and neonatal mortality in swine. Many aspects of SVA infection biology and epidemiology remain unknown. Here, we present a diagnostic investigation conducted in swine herds affected by vesicular disease and increased neonatal mortality. Clinical and environmental samples were collected from affected and unaffected herds and were screened for the presence of SVA by real-time reverse transcriptase PCR and virus isolation. Notably, SVA was detected and isolated from vesicular lesions and tissues of affected pigs, environmental samples, mouse feces, and mouse small intestine. SVA nucleic acid was also detected in houseflies collected from affected farms and from a farm with no history of vesicular disease. Detection of SVA in mice and housefly samples and recovery of viable virus from mouse feces and small intestine suggest that these pests may play a role on the epidemiology of SVA. These results provide important information that may allow the development of improved prevention and control strategies for SVA.

INTRODUCTION

Senecavirus A (SVA) is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA virus of the genus Senecavirus within the family Picornaviridae (1). The SVA genome is ∼7.2 kb in length and contains a unique open reading frame encoding a large polyprotein (2,181 amino acids [aa]), which is cleaved to produce 12 mature proteins (5′-L-1A-1B-1C-1D-2A-2B-2C-3A-3B-3C-3D-3′) (1). Among the picornaviruses, SVA is closely related to members of the genus Cardiovirus (1), including the encephalomyocarditis virus (ECMV) and the theiloviruses, which are known to infect a wide range of vertebrate animals, including pigs, mice, and humans (2).

Senecavirus A was originally identified as a cell culture contaminant in the United States in 2002 (1, 3); however, subsequent sequencing of picorna-like viruses isolated from pigs revealed the presence of the virus in the U.S. swine population since 1988 (3–5). In the past 10 years, sporadic reports have described the association of SVA with cases of swine idiopathic vesicular disease (SIVD) in Canada and in the United States (3–6). Notably, since November 2014, several reports of SVA associated with vesicular disease in swine have been described in Brazil, and since March 2015, an increased number of cases of SVA associated with vesicular lesions and neonatal mortality in swine have been reported in the United States (7–11).

Characteristic lesions associated with SVA infection in pigs include vesicles on the snout, oral mucosa, hoofs, and coronary bands, and typical clinical signs include lameness, lethargy, and anorexia (4–7, 9). Recently, SVA has also been associated with increased mortality (30% to 70%) in piglets that are <7 days of age (7). In these cases, SVA has been detected in serum and in multiple tissues of the affected piglets, including the brain, spleen, liver, heart, kidney, small intestine, and colon; however, no pathological changes have been observed in SVA-positive tissues (10).

Many aspects of SVA infection biology, pathogenesis, and epidemiology remain unknown, including the origin of the virus, its natural reservoirs, and its transmission pathways (11). Notably, a serologic survey conducted in the United States demonstrated neutralizing antibodies against SVA in swine, cattle, and mice (3), suggesting a potential role for these species in the epidemiology of the virus. To date, however, SVA (live virus and/or nucleic acid) has been detected only in pigs, and the actual contribution of other species for the virus ecology is still unknown.

Here, we present the results of a diagnostic investigation conducted in swine herds affected by vesicular disease and neonatal mortality in the United States and in Brazil. By using real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (rRT-PCR) screening followed by virus isolation in cell culture, we detected SVA in clinical and environmental samples, including environmental swabs, mouse feces, and mouse small intestine. SVA nucleic acid was also detected in whole-fly homogenates. Detection of SVA in mice and houseflies and isolation of the virus from mice suggest that these pests may play a role in SVA epidemiology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Characteristics of target swine herds.

A diagnostic investigation was conducted on swine herds located in the Midwest and Southern regions of the United States and Brazil, respectively. The U.S. case herd (herd A) is a 2,800-sow farrow-to-wean commercial farm located in a high swine density area of south-central Minnesota. Mouse and fly samples were also collected from an unaffected farm (absence of vesicular disease; herd B) located approximately 0.3 km from herd A. Herd B consists of a 5,400-sow farm divided into a 4,000-sow farrow-to-wean herd and a 1,400-sow gilt developer unit (GDU). These farms contain air filtration systems to minimize the risk of introduction of airborne pathogens.

Case herds C and D are small farrow-to-finish research farms (518 and 843 animals, respectively) that belong to the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa Swine and Poultry) and are located in the western region of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Case herd D is located approximately 0.2 km from case herd C. Samples were also collected from an unaffected farrow-to-finish farm (absence of vesicular disease; herd E; 179 animals) located approximately 0.2 km from case herds C and D. It is important to note that the farms sampled in our study have closed herds, and no external animals had been introduced to their herds for at least 6 months preceding the vesicular disease outbreaks.

Diagnostic investigation.

A diagnostic investigation was conducted on case herds A, C, and D 2 to 3 days after the onset of the vesicular disease outbreaks. Clinical samples collected from case herd A included oral swabs, vesicular fluids, serum, and whole piglets. These samples were submitted to the University of Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (UMN VDL) and were referred to the Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory at the Plum Island Animal Disease Center for foreign animal disease investigation. Oral swabs and tissue samples were subjected to rRT-PCR for Senecavirus A and other vesicular diseases of swine, including foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV), vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), swine vesicular disease (SVD), and vesicular exanthema of swine (VES). Tissue samples collected from piglets, including small and large intestine pools, were subjected to rRT-PCR assays.

Clinical samples from case herds C and D, including vesicular fluid, nasal swabs, skin from ruptured vesicles, intestine, and tonsil, were subjected to conventional reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) for SVA at Embrapa. At necropsy, a complete pathological examination was conducted in affected piglets. The diagnostic investigation at Embrapa was conducted under the supervision of CIDASC (Company of Integrated Agricultural Development of Santa Catarina), the State's official agricultural inspection agency.

Environmental specimen collection and processing.

Multiple environmental samples were collected from affected herd A following the diagnostic confirmation of SVA (Table 2). Samples were collected from the interior and exterior premises of herd A (Table 2). Interior samples included lesion swabs, 2-ml aliquots of injectable veterinary products (antibiotics, anti-inflammatory, etc.), swabs from the surfaces of walkways, personnel entry swabs, aliquots of semen, flies, whole mice, mouse feces, and interior surface swabs of rodent bait boxes. Exterior samples included dust from exhaust fans, concrete pads and walkways, swabs of the interior surfaces of feed bins, whole mice, interior surface swabs of bait boxes, mouse feces, equipment swabs, and flies. Since several mouse and fly samples collected from herd A tested positive for SVA nucleic acid, these samples were collected from the unaffected herd B. Additionally, a few mouse and fly samples were also collected from SVA-affected herds (herds C and D) and from SVA-unaffected herds (herd E) in Brazil.

TABLE 2.

Detection and isolation of SVA from environmental samples collected in swine herds in the United States and in Brazil

| Herda | Sample identification | Sample description | Real-time PCR (CT)b | VI | VI confirmation real-time PCR (CT) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | Feed residue inside of bins | NDc | ||

| 2 | Dust from exhaust fans | 28.34 | Positive | 9.20 | |

| 3 | Ground outside farm | 29.62 | Positive | 8.48 | |

| 4d | Mortality tractor bucket | 31.6 | Positive | 10.37 | |

| 5 | Vet vehicle cab | ND | |||

| 6 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (gestation) | 30.59 | Positive | 9.57 | |

| 7 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (gestation) | 28.61 | Positive | 8.88 | |

| 8d | Mouse feces in bait boxes (gestation) | 28.84 | Positive | 11.60 | |

| 9 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (farrowing) | 35.74 | NTe | ||

| 10 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (farrowing) | 35.72 | NT | ||

| 11 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (farrowing) | 36.8 | NT | ||

| 12 | Antibiotic A injectable | ND | |||

| 13 | Oxytocin injectable | ND | |||

| 14 | Antibiotic B injectable | 34.89 | NT | ||

| 15 | Gentamicin injectable | ND | |||

| 16 | Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine | ND | |||

| 17 | Acepromazine injectable | ND | |||

| 18 | Porcine circovirus type 2 vaccine | ND | |||

| 19 | Vitamin K injectable | ND | |||

| 20 | Prostaglandin injectable | ND | |||

| 21d | Internal hallway swab | 22.92 | Positive | 11.42 | |

| 22d | Snout lesion swab from affected sow | 18.95 | Positive | 11.83 | |

| 23 | Semen used prior to outbreak | ND | |||

| 24 | Semen used prior to outbreak | ND | |||

| 25 | Office mouse bait box | 34.95 | NT | ||

| 26 | Office floor | ND | |||

| 27 | Concrete pad entrance door | 36.75 | NT | ||

| 28 | Personnel hands and footwear swabs | ND | |||

| 29 | Personnel hands and footwear swabs | ND | |||

| 30 | Personnel hands and footwear swabs | ND | |||

| 31 | Personnel hands and footwear swabs | ND | |||

| 32 | External mouse feces | 32.16 | Positive | 9.78 | |

| 33 | External mouse feces | 35.81 | Positive | 9.07 | |

| 34 | External mouse feces | 35.74 | Negative | ||

| 35 | External mouse feces | ND | |||

| 36 | External mouse feces | ND | |||

| 37 | External bait box swab | 33.85 | Positive | 9.31 | |

| 38 | External bait box swab | 35.02 | Positive | 7.62 | |

| 39 | External bait box swab | ND | |||

| 40 | External bait box swab | ND | |||

| 41 | Feces collected from mouse nest outside the farm | ND | |||

| 42 | Small intestine of mouse collected outside (M1) | ND | |||

| Spleen of M1 | ND | ||||

| Liver of M1 | ND | ||||

| Heart of M1 | ND | ||||

| Lung of M1 | ND | ||||

| Kidney of M1 | ND | ||||

| Brain of M1 | ND | ||||

| 43 | Small intestine of mouse collected outside (M2) | ND | |||

| 44d | Small Intestine of mouse collected inside (M3)d | 30.93 | Positive | 13.06 | |

| Heart of M3 | ND | ||||

| Lung of M3 | ND | ||||

| Brain of M3 | ND | ||||

| 45 | Small Intestine of mouse collected inside (M4) | ND | |||

| 46 | Flies collected inside affected farm | 27.27 | Negative | ||

| 47 | Flies collected outside affected farm | 26.39 | Negative | ||

| 48 | Small intestine of Bird collected outside | ND | |||

| B | 1 | Internal bait box swab (gestation) | ND | ||

| 2 | Internal bait box swab (gestation) | ND | |||

| 3 | Internal bait box swab (farrowing) | ||||

| 4 | Internal bait box swab (farrowing) | ND | |||

| 5 | Mouse feces exterior to farm | ND | |||

| 6 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (gestation) | ND | |||

| 7 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (gestation) | ND | |||

| 8 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (gestation) | ND | |||

| 9 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (gestation) | ND | |||

| 10 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (gestation) | ND | |||

| 11 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (gestation) | ND | |||

| 12 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (farrowing) | ND | |||

| 13 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (farrowing) | ND | |||

| 14 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (farrowing) | ND | |||

| 15 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (farrowing) | ND | |||

| 16 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (farrowing) | ND | |||

| 17 | Mouse feces in bait boxes (farrowing) | ND | |||

| 18 | Small Intestine of Mouse collected outside (M1) | ND | |||

| Spleen of M1 | ND | ||||

| Liver of M1 | ND | ||||

| Kidney of M1 | ND | ||||

| Lung of M1 | ND | ||||

| Brain of M1 | ND | ||||

| 19 | Flies collected outside unaffected farm B | 31.67 | Negative | ||

| 20 | Flies collected inside unaffected farm B | ND | |||

| 21 | Flies collected outside unaffected farm B | ND | |||

| 22 | Flies collected inside unaffected farm B | ND | |||

| 23 | Flies collected outside unaffected farm B | ND | |||

| 24 | Flies collected inside unaffected farm B | ND | |||

| 25 | Flies collected outside unaffected farm B | ND | |||

| 26 | Flies collected inside unaffected farm B | 35.66 | Negative | ||

| C | 1 | Flies collected inside affected farm C | Positive | NT | |

| 2 | Intestine of mouse collected inside 1 | ND | |||

| 3 | Intestine of mouse collected inside 2 | ND | |||

| E | 1 | Flies collected inside unaffected farm | ND |

Herd A, affected farm (Minnesota); herd B, unaffected farm (Minnesota); herd C, affected farm (Santa Catarina, Brazil); herd E, unaffected farm (Santa Caterina, Brazil). Samples from herds A and B were tested by rRT-PCR while samples from herd C were tested by conventional RT-PCR.

CT, threshold cycle.

ND, not detected.

Virus isolates for which complete genome sequences were obtained.

NT, not tested.

Paint rollers were used to sample all interior and exterior surfaces and equipment to collect dust from the exterior shutters of exhaust fans and to sample feed bins (1). Insects were collected using sticky traps and jug traps (Wellmark International, Schaumberg, IL, USA), and whole-fly homogenates were processed as previously described (2, 11). Mouse fecal samples were removed from bait boxes using phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-moistened Dacron swabs and were stored in sterile conical tubes containing 3 ml of PBS (Fisher Scientific, Hanover Park, IL, USA). Similar methods were used to collect interior surface samples from bait boxes and from the hands and soles of footwear of incoming personnel (3). Mice were dissected under a biosafety cabinet, and tissues (small intestine, heart, lung, brain, liver spleen, and kidneys) were collected using standard aseptic techniques. All external samples were collected in the immediate perimeter (within 5 m) of affected or unaffected farm barns.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR.

Viral nucleic acid was extracted using the MagMAX viral RNA/DNA isolation kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) by following the manufacturer's instructions. Detection of SVA RNA was performed using a commercial rRT-PCR kit targeting the SVA 3D polymerase gene (EZ-SVA; Tetracore Inc., Rockville, MD) or a conventional RT-PCR with primers targeting a region of the SVA VP1 to VP3 genes (3). All rRT-PCR screenings of environmental samples from herds A and B were performed at the South Dakota State University (SDSU) Animal Disease and Research Diagnostic Laboratory (ADRDL).

Conventional RT-PCR was performed using SVA-specific primers (SVV-1C556F and SVV-1D441R [3]) and the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) by following the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplicons were subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels and were analyzed under a UV transilluminator.

VI.

Virus isolation (VI) was performed in NCI-H1299 non-small cell lung carcinoma cell lines (ATCC CRL-5803). All samples were processed in PBS (10%, wt/vol). After homogenization samples were cleared by centrifugation at 1,200 rpm at 4°C, the supernatant was diluted (1:1) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with penicillin (300 U/ml), streptomycin (300 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (7.5 μg/ml) and was filtered (0.45 μm) and inoculated into semiconfluent (60 to 80%) monolayers of NCI-H1299 cells cultured in 24-well plates. After 1 h of adsorption, 1 ml complete growth medium (RPMI 1640, 10% fetal bovine serum, 4 mM l-glutamine, penicillin [100 U/ml], streptomycin [100 μg/ml], and amphotericin B [2.5 μg/ml]) was added to each well, and cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 5 days. Each sample was inoculated in duplicate wells, and cell monolayers were monitored daily for cytopathic effect (CPE). Samples were subjected to five blind passages, and those samples that did not induce CPE in inoculated monolayers after the fifth passage were considered negative. Mock-inoculated control cells were included as negative controls on each passage. Isolation of SVA was confirmed by rRT-PCR and immunofluorescence assays.

Immunofluorescence.

Indirect immunofluorescence was used to confirm isolation of SVA. Infected cell cultures that showed CPE were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature, washed three times with PBS, and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After permeabilization, cells were washed three times with PBS and incubated with SVA-specific monoclonal antibody (F61 SVV-9-2-1) (12) or swine convalescent-phase serum. After primary antibody incubation, cells were washed as above and were incubated with anti-mouse (Alexa Fluor 488; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) or anti-swine IgG (DyLight 488; Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) secondary antibodies, respectively.

SVA genome sequencing.

The complete genome sequences of select Senecavirus A isolates obtained in this study were determined by using a primer walking RT-PCR sequencing approach. For this, nine sets of overlapping primers (F1 to F9) covering the entire SVA genome were designed (primer sequences available upon request) using the Primo primer design software (13). Viral cDNA was synthesized using ProtoScript II reverse transcriptase (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and a mixture of oligo d(T)18 and random primer 6 (NEB, Ipswich, MA). Two microliters of cDNA was used in PCR amplification reactions with the Q5 hot start high-fidelity 2× master mix (NEB, Ipswich, MA) by following the manufacturer's protocols. The PCR amplicons (F1 to F9) were subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels to confirm correct target amplification and were purified by using the GenJET PCR purification kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Purified PCR products were sequenced with fluorescent dideoxynucleotide terminators in an ABI 3700 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA). Sequence assembly and editing were performed with the Lasergene analysis software package (Lasergene version 5.07; DNAStar Inc., Madison, WI).

SVA genome comparison and phylogenetic analysis.

Alignment and comparison of the complete genome and VP1 nucleotide sequences between SVA isolates obtained here and those of SVA strains available in GenBank (accession numbers DQ641257, KC667560, KR063108, KR063107, KR063109, KT757280, KT757281, KT757282, KT321458, KR075677, KR075678, EU271758, EU271763, EU271757, EU271762, EU271761, EU271760, EU271759) were performed by using ClustalW (14) in the MEGA 6 software (15). The complete SVA genome and a 539-nucleotide (nt) region of the VP1 gene were used to construct phylogenetic trees. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the neighbor-joining method in MEGA 6 (MEGA version 6) (15). The codon positions included in the analysis were the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and noncoding.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The complete genome sequences of SVA isolates MN15-84-4 (swab from mortality tractor bucket), MN15-84-8 (mouse fecal sample), MN15-84-M3 (mouse small intestine), MN15-84-21 (swab from internal hallway), and MN15-84-22 (lesion swab from sow) are available in GenBank under accession numbers KU359210, KU359211, KU359212, KU359213, KU359214.

RESULTS

Clinical history and SVA diagnosis (case herd A).

On 26 September 2015, an outbreak of acute watery diarrhea followed by profound lethargy was observed in 3- to 7-day-old piglets in two farrowing rooms of herd A. Morbidity of approximately 75% and mortality rates of 50% were observed in piglets housed in the affected farrowing rooms. Clinical signs, including lethargy and diarrhea, were subsequently observed in piglets from two other farrowing rooms of this farm (over 5 to 7 days), with morbidity and mortality rates of 25% and 15%, respectively. On 29 September 2015, an acute outbreak of vesicular disease was observed in approximately 75% of the sows in the gestation barns of herd A. Vesicles ranging from 1 to 3 cm in diameter were observed on the snout and coronary bands of affected sows, and after 5 to 10 days, these vesicles ruptured leaving a dry scab in the affected skin. Affected sows also presented vesicles in the dewclaws and demonstrated lameness.

The diagnostic investigation conducted at the UMN VDL revealed the presence of SVA nucleic acid in oral swabs collected from affected sows (seven out of seven tested [7/7]) and in intestinal homogenates from affected piglets (3/3). A summary of the diagnostic results is presented in Table 1. All tests performed for other vesicular diseases (FMDV, VSV, VES, and SVD) were negative.

TABLE 1.

Detection of SVA in clinical samples following outbreaks of vesicular disease in sow herds in the United States and in Brazil

| Herd | Sample identification | Sample description | PCR result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | Sow 1 | Oral swab | Positive |

| Sow 2 | Oral swab | Positive | |

| Sow 3 | Oral swab | Positive | |

| Sow 4 | Oral swab | Positive | |

| Sow 5 | Oral swab | Positive | |

| Sow 6 | Oral swab | Positive | |

| Sow 7 | Oral swab | Positive | |

| Piglet 1 | Intestineb | Positive | |

| Piglet 2 | Intestine | Positive | |

| Piglet 3 | Intestine | Positive | |

| Cc | Sow 150 | Nasal swab | NDd |

| Sow 154e | Vesicular fluid | Positive | |

| Nasal swab | ND | ||

| Sow 190 | Nasal swab | ND | |

| Sow 271e | Vesicular fluid | Positive | |

| Nasal Swab | ND | ||

| Coronary band of the hoof | Positive | ||

| Sow 278 | Nasal swab | ND | |

| Sow 346 | Nasal swab | ND | |

| Sow 798 | Vesicular fluid | Positive | |

| Sow 767 | Vesicular fluid | Positive | |

| Sow 820 | Nasal swab | ND | |

| Sow 966 | Nasal swab | ND | |

| Sow 975 | Nasal swab | ND | |

| Sow 988e | Vesicular fluid | Positive | |

| Nasal swab | ND | ||

| Sow 1170 | Nasal swab | ND | |

| Sow 1551 | Nasal swab | ND | |

| Piglet 262 | Intestine | ND | |

| Piglet | Intestine | Positive | |

| Dc | Piglet 1 | Tonsil | Positive |

| Piglet 2 | Tonsil | Positive | |

| Piglet 2 | Coronary band of the hoof | Positive |

Herd A was located in Minnesota. Samples from herd A were tested by rRT-PCR.

Pooled small and large intestine homogenate.

Herds C and D were located in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Samples from herd C and D were tested by conventional RT-PCR.

ND, not detected.

These animals presented vesicular lesions. Vesicular fluids tested positive for SVA while nasal swabs were negative.

Clinical history and SVA diagnosis (case herds C and D).

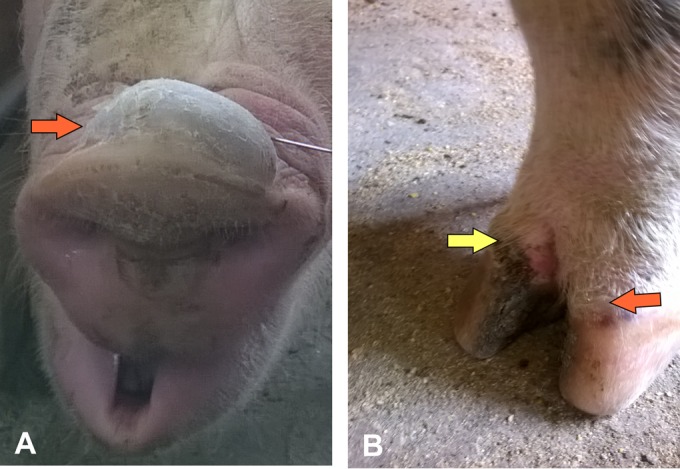

Clinical signs were first observed in sows in the gestation barn of herd C on 30 October 2015. Initially, five animals presented vesicular lesions, including one sow with vesicles on the snout and coronary band of the hoof (Fig. 1) and four sows with ruptured vesicles on the snout. A total of 28 sows (25 in the gestation barn and three in the maternity barn) and 2 boars were affected (morbidity of 15%). Piglets were not affected in this herd. Six sows presented lameness, and 3 days later, ulcerative lesions were observed on the walls of their hoofs.

FIG 1.

Clinical presentation of Senecavirus A in sows. Vesicular lesions on the snout (A) and coronary bands (B) of a sow from herd C. (A) Large vesicles (1 to 3 cm in diameter, orange arrow) were filled with fluid, ruptured, and dried out after 5 to 10 days, leaving a dry scab covering the affected skin. (B) Dried scab (yellow arrow) on the wall of the hoof and ruptured vesicle on the coronary band (orange arrow).

On 3 November, clinical signs were observed in two sows in the maternity room of herd D (located 0.2 km from herd C). One sow presented an intact vesicle on the snout, and another sow had a ruptured vesicle on the snout (morbidity of 1.5%). Interestingly, a sudden increase in neonatal mortality was observed in 3- to 5-day-old piglets. Mortality rates in piglets reached 34% one week after the first vesicular lesions were observed in the sows. In addition, the suckling piglets presented lethargy and watery diarrhea over a period of approximately 5 to 7 days.

Diagnostic investigation conducted at Embrapa revealed the presence of SVA nucleic acid in various clinical samples, including vesicular fluid collected from lesions, the skin of ruptured vesicles, and in the small intestine, tonsil, and coronary band of affected piglets. No SVA was detected in nasal swabs (Table 1). At necropsy, the piglets presented enlargement and edema of inguinal lymph nodes, ascites, severe edema of the mesocolon, and severe necrosis of the coronary bands (data not shown).

Detection of Senecavirus A in environmental samples.

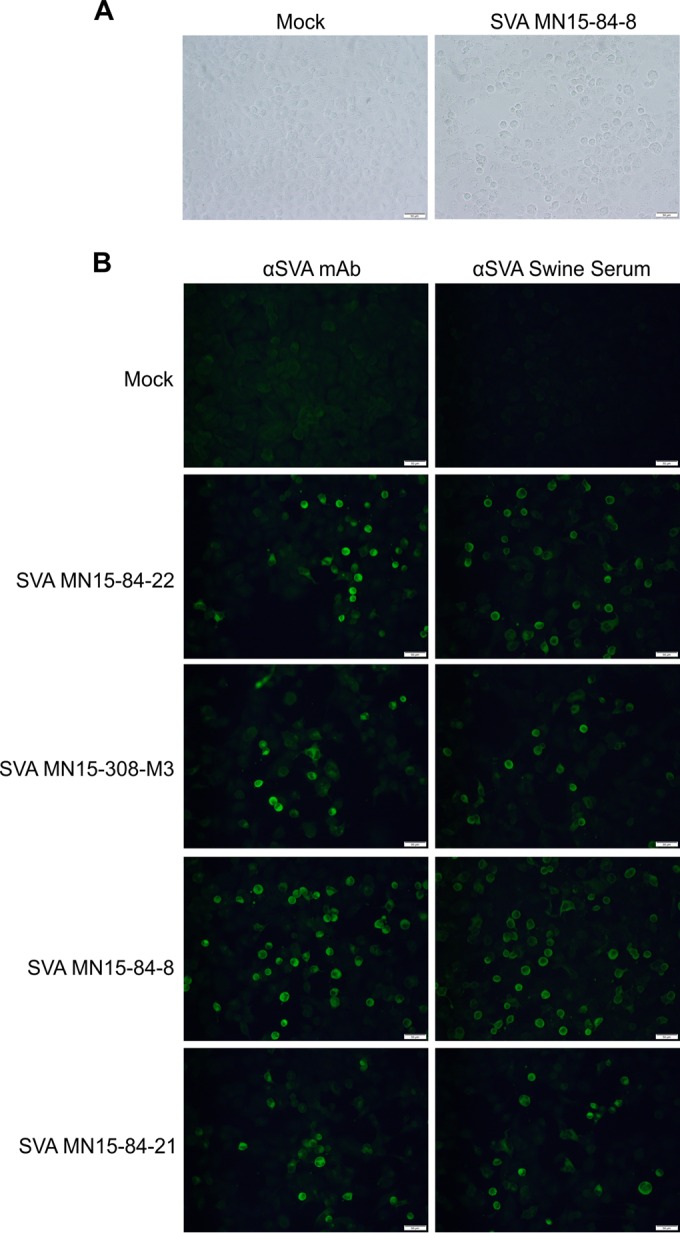

Environmental samples collected from case herd A and from unaffected herd B were screened by rRT-PCR. All samples were collected following standard sampling protocols (16–18), processed for viral RNA isolation, and screened by SVA rRT-PCR at the SDSU ADRDL. A summary of the rRT-PCR screening results is presented in Table 2. Senecavirus A was detected in clinical samples (lesion swabs) and in multiple environmental samples collected from the interior and exterior areas of the affected farm. Notably, the virus was detected in mouse fecal samples collected in bait boxes located in the interior and exterior areas of case herd A. Additionally, the small intestine collected from a mouse on farm A was positive for SVA (Table 2; Fig. 2). All other tissues collected from this mouse, including its heart, brain, and lungs, were negative for SVA (Table 2). Fly samples collected from the affected herd A and from the unaffected herd B were also positive for SVA nucleic acid. In addition, a pool of flies collected from herd C (Brazilian farm) tested positive for SVA (Table 2).

FIG 2.

Isolation of Senecavirus A in cell culture. (A) Cytopathic effect (rounded cells) observed in H1299 non-small lung cell carcinoma cells following inoculation of mouse fecal sample into semiconfluent monolayers (48 h postinoculation; right). Mock-infected control cells (left). (B) Immunofluorescence assay confirming isolation of SVA from environmental samples. SVA-specific monoclonal antibody (F61 SVV-9-2-1 [12], left) or convalescent-phase serum (right) were used. SVA isolates shown were obtained from a swab from the snout of a sow (SVA-MN15-84-22), mouse small intestine (SVA-MN15-308-M3), mouse fecal sample (SVA-MN15-84-8), and from an environmental swab (SVA-MN15-84-21). Magnification, 200×; scale bar, 50 μm.

Isolation of Senecavirus A from environmental samples.

Virus isolation (VI) was performed in select SVA PCR-positive samples to assess the presence of viable virus. All VIs were performed in a highly permissive human non-small lung carcinoma cell line (H1299) (19). SVA isolation, as evidenced by development of CPE in inoculated cell cultures (Fig. 2A), was confirmed by rRT-PCR (Table 2) and by immunofluorescence assays (Fig. 2B). A summary of the VI results is presented in Table 2. Senecavirus A was isolated from multiple environmental samples. Most interestingly, SVA was consistently isolated from mouse fecal samples and from a mouse small intestine collected in case herd A. No virus was isolated from PCR-positive fly samples.

Genetic comparisons and phylogenetic analysis.

Complete genome sequences of five SVA isolates (MN15-84-4, MN15-84-8, MN15-84-21, MN15-84-22, and MN15-308-M3) obtained from case herd A were compared to other SVA sequences available in GenBank. Complete genome sequence comparisons revealed that the isolates characterized here share 93% to 94% nucleotide identity with the prototype U.S. SVA strain SVV-001, 96% nucleotide identity with an isolate obtained in Canada in 2011 (SVA-11-55910-3), 98% to 99% nucleotide identity with other contemporary isolates recently obtained in the United States (IA40380/2015, IA46008/2015, and SD41901/2015), 97% nucleotide identity with Brazilian isolates (BRA-MG1/2015, BRA-MG2/2015, and BRA-GO3/2015), and 96% nucleotide identity with a recent Chinese isolate (CH-1-2015) (Table 3). Comparison of the amino acid sequences of SVA polyprotein (2,181 aa) revealed that the MN isolates here share 97% to 99% amino acid identity with other SVA strains (Table 3). Comparisons based on a 541-nt region of the VP1 gene revealed a similar genetic heterogeneity between these isolates (Table 4). A greater genetic divergence (86% to 88% nucleotide identity), however, was observed when the MN isolates were compared to historical isolates obtained prior to 2002 (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Complete genome sequence comparisons between the SVA isolates MN15-84-4, MN15-84-8, MN15-84-21, MN15-84-22, and MN15-308-M3 and other historical and contemporary SVA strains

| SVA isolatea | Percentage identity for SVA isolateb |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MN15-84-4 |

MN15-84-8 |

MN15-84-21 |

MN15-84-22 |

MN15-308-M3 |

||||||

| nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | nt | aa | |

| SVV001 | 93 | 97 | 94 | 97 | 93 | 97 | 93 | 97 | 94 | 97 |

| 11-55910-3 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 98 |

| IA40380/15 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 |

| IA46008/15 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 99 |

| SD41901/15 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 99 | 98 | 99 |

| BRAMG1/15 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 |

| BRAMG2/15 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 |

| BRAGO3/15 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 | 97 | 99 |

| CH-1-15 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 98 |

| MN15-84-4 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | ||

| MN15-84-8 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | ||

| MN15-84-21 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | ||

| MN15-84-22 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | ||

| MN15-308-M3 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 | ||

TABLE 4.

Comparison of nucleotide sequences of VP1 gene between historical and contemporary SVA isolates

| SVA isolatea | Percentage identity for SVA isolateb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MN15-84-4 | MN15-84-8 | MN15-84-21 | MN15-84-22 | MN15-308-M3 | |

| SVV001 | 91 | 91 | 91 | 91 | 91 |

| 11-55910-3 | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 |

| 131395 | 92 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| 1278 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| 89-47752 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| 92-48963 | 87 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| 90-10324 | 87 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 88 |

| 88-36695 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 |

| 88-23626 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 86 |

| IA40380/15 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| IA46008/15 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 |

| SD41901/15 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 |

| BRAMG1/15 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| BRAMG2/15 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| BRAGO3/15 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| BRA/UEL-B2/15 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| BRA/UEL-A1/15 | 96 | 97 | 97 | 97 | 97 |

| CH-1-15 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 | 96 |

| MN15-84-4 | 99 | 99 | 99 | 99 | |

| MN15-84-8 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| MN15-84-21 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| MN15-84-22 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| MN15-308-M3 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

GenBank accession numbers are DQ641257, KC667560, EU271758, EU271763, EU271757, EU271762, EU271761, EU271760, EU271759, KT757280, KT757282, KT757281, KR063107, KR063108, KR063109, KR075678, KR075677, KT321458, KU359210, KU359211, KU359212, KU359213, and KU359214, respectively.

A 541-nt region of the VP1 gene (nucleotide positions 2680 to 3220 of the genome of SVA prototype strain SVV-001) were aligned by using CLUSTAL W (14).

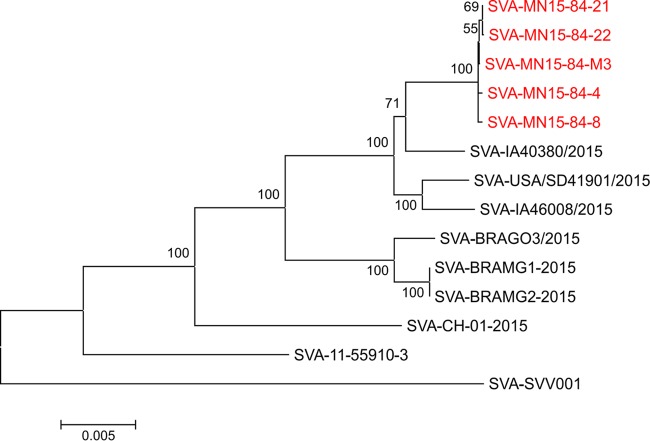

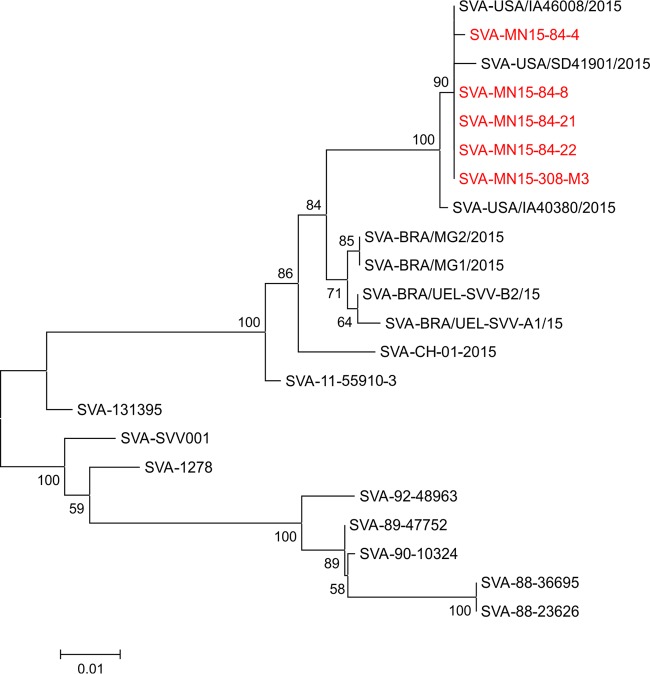

Phylogenetic reconstructions based on complete genome sequences or the VP1 gene show clear phylogenetic separation between historical (1988 to 2002) and contemporary (2007 to 2015) SVA strains (Fig. 3 and 4). Phylogenetic analysis based on the VP1 gene revealed that all of the isolates obtained here cluster with other SVA strains currently circulating in swine in the United States (Fig. 3). Similarly, contemporary SVA isolates from distinct geographic locations (i.e., the United States, Brazil, and China) form separate phylogenetic clusters (Fig. 3 and 4). The virus that appears to be most closely related to the isolates characterized here is the strain SVA-IA40380/2015, which was obtained from an exhibition pig in Iowa (8) (Fig. 3 and 4).

FIG 3.

Evolutionary relationships of Senecavirus A based on complete genome sequences. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method (24). The optimal tree with a sum of branch length of 0.11793138 is shown. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches (25). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method (26) and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 14 nucleotide sequences. Codon positions included were 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and noncoding. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 7,098 positions in the final data set. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA 6 (15).

FIG 4.

Evolutionary relationships of Senecavirus A based on the VP1 gene. The evolutionary history was inferred using the neighbor-joining method (24). The optimal tree with a sum of branch length of 0.21986844 is shown. The percentages of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches (25). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method (26) and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 22 nucleotide sequences. Codon positions included were 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and noncoding. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 539 positions in the final data set. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA 6 (15).

DISCUSSION

Senecavirus A has been associated with sporadic outbreaks of vesicular disease in pigs in the United States since the late 1980s (3–6). Recently, however, an increased number of reports have described the association of SVA with vesicular disease and neonatal mortality in swine (7, 8). Notably, the number of cases of SVA has jumped from 2 in 2014 to over 100 in 2015 (December 2015 report of the Swine Health Monitoring Project). Since November 2014, SVA has also been frequently reported in swine in Brazil (7, 9). However, the factors that contributed to the reemergence of SVA in the United States and its emergence in Brazil remain unknown.

Here, we present the findings of a diagnostic investigation conducted in two swine breeding farms located in high swine density areas in the United States and Brazil. In September and October 2015, outbreaks of vesicular disease and neonatal mortality were confirmed in two swine breeding farms located in Minnesota and in the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina. Senecavirus A nucleic acid was detected in vesicular fluid, oral and lesion swabs (coronary bands) from affected sows, and in intestinal homogenates, tonsil, and coronary swabs from affected piglets (Table 1). These findings corroborate the results of recent reports that describe the association of SVA with vesicular disease and neonatal mortality in swine (7, 9, 10). Additionally, results here are consistent with studies that demonstrated the detection of SVA in vesicular fluid, lesion swabs, lesion scrapings, and oral swabs, indicating that these specimens are appropriate for SVA diagnosis (9, 20). SVA nucleic acid has also been detected in serum and in various tissues from affected animals (lymph nodes, tonsil, spleen, and lung) (7, 20). Notably, piglets that died during SVA outbreaks presented high viral loads in multiple tissues, including brain, liver, lung, heart, kidney, small intestine, and colon (10). Interestingly, SVA nucleic acid was not detected in nasal swabs collected from affected sows from herd C (Table 1); however, the possibility that they contained small amounts of viral nucleic acid below the detection limit of the RT-PCR assay used for testing cannot be formally excluded.

Clinically, the outbreaks investigated here were characterized by lethargy, watery diarrhea, and increased neonatal mortality (15% to 50% in piglets <7 days of age), which occurred concomitantly with vesicular lesions (snout and coronary bands) and lameness in sows (morbidity ranging from 1.5% to 75%). Clinical signs and neonatal mortality lasted for approximately 5 to 10 days when lesions started to subside and neonatal mortality decreased to preoutbreak rates (5% to 8%). The morbidity and mortality rates observed here are similar to those described in recent reports of SVA outbreaks in Brazil and the United States (7–10). Historically, SVA has been associated with vesicular lesions in adult animals (4–6, 9), whereas common findings in recent outbreaks include diarrhea and sudden death in suckling piglets (7). Similarly, in the outbreaks investigated here, piglets presented diarrhea, lethargy, and mortality, which were followed by the development of vesicular lesions in sows. This was observed in two of the three affected herds (herds A and D), while in the third herd (herd C), only sows presented clinical signs (vesicular lesions and lameness). Although several aspects of SVA infection biology remain unknown (i.e., the pathogenesis of the disease in swine), our study presents additional evidence demonstrating the association of SVA with vesicular disease and neonatal mortality in pigs. Detection and isolation of the virus from lesions and tissues from affected animals coupled with the absence of other pathogens known to cause vesicular and/or enteric disease in swine strengthen the notion that SVA may be the cause of these distinct clinical presentations in swine. Indeed, vesicular disease has been recently reproduced in pigs inoculated with SVA (L. R. Joshi and D. G. Diel, unpublished data; K. J. Yoon, N. Montiel, and K. Lager, presented at the 2015 NA PRRSV Symposium and Conference for Research Workers on Animal Health Meeting, Chicago, IL, 5 to 8 December 2015), confirming the role of the virus as the etiologic agent of vesicular disease in swine.

After confirmation of SVA infection in pigs (Table 1), an investigation was conducted to assess possible sources of SVA within affected herds. For this, multiple environmental samples (Table 2) were collected from affected herd A and were tested for the presence of SVA. SVA nucleic acid was detected and viable virus was recovered from various environmental samples from herd A, including swabs from internal and external building surfaces and farm tools and equipment. Interestingly, SVA was also detected and isolated from mouse fecal samples and from a mouse (Mus musculus) small intestine collected from farm A (Table 2; Fig. 2). Additionally, SVA nucleic acid was detected in houseflies (Musca domestica) collected within the premises of the affected farm A. Following detection of SVA in mice and houseflies in herd A, we collected these samples from an unaffected farm in the United States (herd B) and from affected (herd D) and unaffected farms (herd E) in Brazil. Notably, SVA nucleic acid was detected in houseflies collected from the exterior of the unaffected farm in the United States (herd B; located 0.3 km from affected farm A) and in a pool of flies collected from the affected farm in Brazil (herd D) (Table 2). Results here demonstrate viable SVA in various environmental samples, including farm tools, building surfaces and equipment, and in multiple mouse samples (feces and intestine) collected from SVA-affected farm A. Given that these samples were collected after the SVA outbreak in swine, it is not possible to draw definitive conclusions about the source of the virus responsible for the outbreak. However, these results suggest that farm tools and equipment can potentially function as fomites and transfer SVA to susceptible animals within affected herds. Most interestingly, our data demonstrating that mice can carry and, perhaps, shed SVA in feces (Table 2) suggest that these pests may contribute to the spread of SVA within affected herds. Additional sampling and testing are needed, however, to determine the actual role of this species in the ecology of SVA. It would be interesting, for example, to collect mouse samples in areas where SVA has not been detected in swine to assess whether this species functions as a natural reservoir for SVA. Although no viable SVA was recovered from rRT-PCR-positive housefly samples tested here, detection of the virus on this pest deserves consideration.

Mice and houseflies are among the most common and widely distributed pests and have been frequently associated with infectious disease transmission to humans and animals (21, 22, 27). They can serve as natural reservoirs or mechanical vectors for several bacterial and viral pathogens, including various picornaviruses such as enteroviruses and ECMV, which are known to infect humans, pigs, and other animal species (21, 22). Results showing that mice can carry viable SVA (small intestine and feces) and that flies can carry the virus' nucleic acid suggest that these species may play a role in SVA ecology. Detection of SVA in mice corroborates early serologic surveys that have shown the presence of neutralizing antibodies against SVA in this species (14% of samples tested were positive) (3). Although the results presented here demonstrate the association of SVA with mice and houseflies, additional studies are needed to define the actual role and contribution of these species in SVA infection biology and epidemiology. Studies designed to assess the susceptibility of mice to SVA infection, to define sites of virus replication and routes and duration of virus shedding, and to assess the survival of SVA in houseflies would shed light on the potential role of these pests in SVA ecology and the actual risk they may pose to swine.

Many factors may have contributed to the recent emergence of SVA in swine (23), including the genetic evolution of contemporary virus strains (Fig. 3 and 4). Genetic comparisons between historical (obtained between 1988 and 2002) and contemporary SVA isolates (obtained between 2007 and 2015) revealed a high genetic diversity between these viruses (86% to 88% at the VP1 gene and 93% to 94% nucleotide identity when the complete genome sequence was compared). All contemporary isolates that have been sequenced to date (including those obtained in the United States, Brazil, and most recently in China), however, share 96% to 99% nucleotide identity. Additionally, phylogenetic analysis and inference of the evolutionary distances (data not shown) between SVA isolates revealed a marked evolution of contemporary SVA isolates compared to historical viral strains (Fig. 3 and 4). These evolutionary changes may have resulted in (i) an increased adaptation of SVA to pigs or (ii) an improved ability of the virus to spread between hosts and/or natural reservoirs. These possibilities, however, await experimental confirmation.

In summary, we describe the detection of Senecavirus A in swine presenting vesicular disease and neonatal mortality and in two common and widely distributed pests, mice and houseflies. These results provide the first evidence of live SVA in mice, corroborating the findings of Knowles at al. who detected neutralizing antibodies against SVA in this species (3). These observations suggest that mice and houseflies may play a role in SVA epidemiology.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our colleagues Matthew Dammen and Michael Dunn from the SDSU ADRDL Molecular Diagnostics Section and Marcos Morés and Nelson Morés from Embrapa Swine and Poultry for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Tetracore Inc. for providing the real-time PCR reagents and Ming Yang (National Centre for Foreign Animal Disease, Winnipeg, Canada) for providing SVA-specific monoclonal antibodies for our study.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Swine Health Information Center (project 15-192), the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Hatch (project SD00H517-14), and by Embrapa (project 02.11.01.006).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hales LM, Knowles NJ, Reddy PS, Xu L, Hay C, Hallenbeck PL. 2008. Complete genome sequence analysis of Seneca Valley virus-001, a novel oncolytic picornavirus. J Gen Virol 89:1265–1275. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carocci M, Bakkali-Kassimi L. 2012. The encephalomyocarditis virus. Virulence 3:351–367. doi: 10.4161/viru.20573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowles NJ, Hales BH, Jones JG, Landgraf JA, House KL, Skele KD, Burroughs KD, Hallenbeck PL. 2006. Epidemiology of Seneca Valley virus: identification and characterization of isolates from pigs in the United States, p G2 In EUROPIC 2006: XIVth Meeting of the European Study on Molecular Biology of Picornaviruses Saariselka, Inari, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh K, Corner S, Clark SG, Scherba G, Fredrickson R. 2012. Seneca Valley virus and vesicular lesions in a pig with idiopathic vesicular disease. J Vet Sci Technol 3:123. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amass SF, Schneider JL, Miller CA, Shawky SA, Stevenson GW, Woodruff ME. 2004. Idiopathic vesicular disease in a swine herd in Indiana. J Swine Health Prod 12:192–196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasma T, Davidson S, Shaw SL. 2008. Idiopathic vesicular disease in swine in Manitoba. Can Vet J 49:84–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vannucci FA, Linhares DCL, Barcellos DESN, Lam HC, Collins J, Marthaler D. 2015. Identification and complete genome of Seneca Valley virus in vesicular fluid and sera of pigs affected with idiopathic vesicular disease, Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis 62:589–593. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Piñeyro P, Chen Q, Zheng Y, Li G, Rademacher C, Derscheid R, Guo B, Yoon K-J, Madson D, Gauger P, Schwartz K, Harmon K, Linhares D, Main R. 2015. Full-length genome sequences of Senecavirus A from recent idiopathic vesicular disease outbreaks in U.S. swine. Genome Announc 3(6):e01270-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leme RA, Zotti E, Alcântara BK, Oliveira MV, Freitas LA, Alfieri AF, Alfieri AA. 2015. Senecavirus A: an emerging vesicular infection in brazilian pig herds. Transbound Emerg Dis 62:603–611. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linhares D, Vannucci F. 2015. Epidemic transient neonatal losses and Senecavirus A. Pig333. https://www.pig333.com/what_the_experts_say/epidemic-transient-neonatal-losses-and-senecavirus-a_10634/.

- 11.Joshi LR, Diel DG. 2015. Senecavirus A: a newly emerging picornavirus of swine. EC Microbiol 2:363–364. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang M, van Bruggen R, Xu W. 2012. Generation and diagnostic application of monoclonal antibodies against Seneca Valley virus. J Vet Diagn Invest 24:42–50. doi: 10.1177/1040638711426323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li P, Kupfer KC, Davies CJ, Burbee D, Evans GA, Garner HR. 1997. PRIMO: a primer design program that applies base quality statistics for automated large-scale DNA sequencing. Genomics 40:476–485. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.4560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dee S, Clement T, Schelkopf A, Nerem J, Knudsen D, Christopher-Hennings J, Nelson E. 2014. An evaluation of contaminated complete feed as a vehicle for porcine epidemic diarrhea virus infection of naïve pigs following consumption via natural feeding behavior: proof of concept. BMC Vet Res 10:176. doi: 10.1186/s12917-014-0176-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitkin A, Deen J, Otake S, Moon R, Dee S. 2009. Further assessment of houseflies (Musca domestica) as vectors for the mechanical transport and transmission of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus under field conditions. Can J Vet Res 73:91–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schurrer JA, Dee SA, Moon RD, Rossow KD, Mahlum C, Mondaca E, Otake S, Fano E, Collins JE, Pijoan C. 2004. Spatial dispersal of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus-contaminated flies after contact with experimentally infected pigs. Am J Vet Res 65:1284–1292. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2004.65.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reddy PS, Burroughs KD, Hales LM, Ganesh S, Jones BH, Idamakanti N, Hay C, Li SS, Skele KL, Vasko A-J, Yang J, Watkins DN, Rudin CM, Hallenbeck PL. 2007. Seneca Valley virus, a systemically deliverable oncolytic picornavirus, and the treatment of neuroendocrine cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 99:1623–1633. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bracht AJ, O'Hearn ES, Fabian AW, Barrette RW, Sayed A. 2016. Real-time reverse transcription PCR assay for detection of Senecavirus A in swine vesicular diagnostic specimens. PLoS One 11(1):e0146211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Backhans A, Fellström C. 2012. Rodents on pig and chicken farms—a potential threat to human and animal health. Infect Ecol Epidemiol 2:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graczyk TK, Knight R, Gilman RH, Cranfield MR. 2001. The role of non-biting flies in the epidemiology of human infectious diseases. Microbes Infect 3:231–235. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morse SS. 1995. Factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Emerg Infect Dis 1:7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felsenstein J. 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39:783. doi: 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. 2004. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:11030–11035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Otake S, Dee SA, Moon RD, Rossow KD, Trincado C, Farnham M, Pijoan C. 2003. Survival of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in houseflies. Can J Vet Res 67:198–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]