Abstract

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] activates the yeast cell wall integrity pathway. Candida albicans exposure to caspofungin results in the rapid redistribution of PI(4,5)P2 and septins to plasma membrane foci and subsequent fungicidal effects. We studied C. albicans PI(4,5)P2 and septin dynamics and protein kinase C (PKC)-Mkc1 cell wall integrity pathway activation following exposure to caspofungin and other drugs. PI(4,5)P2 and septins were visualized by live imaging of C. albicans cells coexpressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-pleckstrin homology (PH) domain and red fluorescent protein-Cdc10p, respectively. PI(4,5)P2 was also visualized in GFP-PH domain-expressing C. albicans mkc1 mutants. Mkc1p phosphorylation was measured as a marker of PKC-Mkc1 pathway activation. Fungicidal activity was assessed using 20-h time-kill assays. Caspofungin immediately induced PI(4,5)P2 and Cdc10p colocalization to aberrant foci, a process that was highly dynamic over 3 h. PI(4,5)P2 levels increased in a dose-response manner at caspofungin concentrations of ≤4× MIC and progressively decreased at concentrations of ≥8× MIC. Caspofungin exposure resulted in broad-based mother-daughter bud necks and arrested septum-like structures, in which PI(4,5)P2 and Cdc10 colocalized. PKC-Mkc1 pathway activation was maximal within 10 min, peaked in response to caspofungin at 4× MIC, and declined at higher concentrations. The caspofungin-induced PI(4,5)P2 redistribution remained apparent in mkc1 mutants. Caspofungin exerted dose-dependent killing and paradoxical effects at ≤4× and ≥8× MIC, respectively. Fluconazole, amphotericin B, calcofluor white, and H2O2 did not impact the PI(4,5)P2 or Cdc10p distribution like caspofungin did. Caspofungin exerts rapid PI(4,5)P2-septin and PKC-Mkc1 responses that correlate with the extent of C. albicans killing, and the responses are not induced by other antifungal agents. PI(4,5)P2-septin regulation is crucial in early caspofungin responses and PKC-Mkc1 activation.

INTRODUCTION

Echinocandin antifungals are the agents of choice for the treatment of most cases of invasive candidiasis (1–3). The echinocandins disrupt cell wall integrity through inhibition of β-1,3-d-glucan synthase, an enzyme that synthesizes a major fungal cell wall component (3). Brief exposures to inhibitory concentrations of echinocandins in vitro trigger cellular events that result in sustained killing of Candida albicans (4–7). The killing of certain C. albicans strains is attenuated during ongoing exposure to echinocandins (in particular, caspofungin) at concentrations that significantly exceed the MIC (8). These paradoxical effects are not known to be relevant in the treatment of invasive candidiasis. Nevertheless, the phenomenon is a useful model for studying cell wall stress responses. The precise mechanisms of paradoxical growth are incompletely understood, but the phenotype is associated with increased chitin synthesis (9). It is eliminated in C. albicans mutant strains with disruptions in the protein kinase C (PKC)-Mkc1 (cell wall integrity mitogen-activated protein [MAP] kinase), Hog1 (high-osmolarity glycerol), or calcineurin stress response pathway (8, 10).

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] is a phospholipid that is located primarily at the cytoplasmic face of eukaryotic plasma membranes, where it is a precursor to secondary messengers and serves structural and signaling roles through recruitment of effector proteins (11). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, PI(4,5)P2 activates the cell wall integrity pathway following a variety of stresses through interactions with Rho1, a GTPase that is both an upstream regulator of the pathway and a regulatory subunit of β-1,3-d-glucan synthase, and Rom2, an Rho1 guanine exchange factor (GEF) (11–13). Septins are cytoskeletal proteins that interact with PI(4,5)P2, serve as scaffolds for cytokinesis, septation, and other dynamic plasma membrane events, and help localize chitin deposition (14–16). We recently demonstrated that PI(4,5)P2 and septins colocalize to plasma membrane foci in response to caspofungin (17). Disruption of C. albicans INP51, which encodes a PI(4,5)P2-specific 5′-phosphatase, or IRS4, which encodes an interacting EH domain protein, results in elevated PI(4,5)P2 levels, overactivation of the PKC-Mkc1 pathway in response to stress, cell wall damage response gene expression profiles in the absence of stress, hypersusceptibility to caspofungin, and elimination of paradoxical growth at high caspofungin concentrations (8, 17–19). Disruption of GIN4, which encodes a septin regulatory protein kinase, results in similar phenotypes and cell wall damage response gene expression. Moreover, inp51-, irs4-, and gin4-null mutants exhibit aberrant PI(4,5)P2 and septin colocalization resembling that seen in wild-type C. albicans cells exposed to caspofungin (17, 19). Taken together, the data suggest that PI(4,5)P2 and septins are joined in a pathway that plays a role in the natural response of C. albicans to the cell wall stress imposed by caspofungin (17).

In our earlier study (17), PI(4,5)P2 and septin redistribution was evident in C. albicans SC5314 cells exposed to caspofungin at the MIC (0.125 μg/ml) for 5 min. The objectives of this study were to determine the extended time course and specificity of the PI(4,5)P2, septin, and PKC-Mkc1 pathway responses to caspofungin, the association between these responses and fungicidal activity or paradoxical effects, and the epistatic relationship between PI(4,5)P2 regulation and MKC1. We hypothesized that PI(4,5)P2 and septin dysregulation is caused by caspofungin but not other antifungal or cell wall-active agents, the extent of dysregulation is dose dependent and correlates with the level of killing, and PI(4,5)P2 responses are not dependent upon Mkc1p.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

We previously created C. albicans SC5314 strains that express a C. albicans-optimized green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged pleckstrin homology (PH) domain tandem repeat (CaPH×2-GFP), a C. albicans-optimized red fluorescent protein (RFP)-tagged Cdc10p, or both (17). PH domains bind specifically to PI(4,5)P2 (20), allowing us to track PI(4,5)P2 localization and levels. In this study, strains were recreated by integrating the constructs into a noncoding genomic region at coordinates 625,000 to 627,000 of chromosome 1, instead of the previously used RP10 locus (17). In preliminary studies, we confirmed that these engineered strains did not differ from SC5314 in growth rates under a range of conditions in vitro, hyphal formation in liquid media, invasive growth into solid medium, Mkc1 phosphorylation, or susceptibility to caspofungin, fluconazole, amphotericin B, H2O2, and calcofluor white. Wild-type DAY286 and mkc1-null mutant VIC1177 strains (generously provided by Aaron Mitchell, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA) were transformed with the CaPH×2-GFP construct. Positive transformants expressing the GFP reporter, once validated, were used for live cell imaging during exposure to caspofungin.

Drug susceptibility.

Caspofungin MICs (SC5314 MIC = 0.125 μg/ml) were measured using a Sensititre Yeast One panel (Trek Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, OH), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Fluconazole and amphotericin B MICs (both 0.5 μg/ml) were measured using reference broth microdilution methods proposed by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Susceptibility to H2O2 and calcofluor white were measured using our previously published methods (19, 21).

Live cell imaging.

Microscopy was performed at the University of Pittsburgh Center for Biologic Imaging, using established protocols (17). We used a Nikon A1 confocal microscope for live cell imaging and acquired data with NIS Elements software (Nikon). C. albicans cells were grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose (YPD) medium at 30°C and then subcultured in the presence of the drug concentrations given below on 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (Matek, Ashland, MA). The dishes were pretreated with 10 μg/cm2 of Cell-Tak adhesive (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) to adsorb a thin layer on which Candida cells were immobilized for microscopy. We measured PI(4,5)P2 levels by tracing and quantitating the GFP signal across frames using Imaris software (Bitplane USA, Concord, MA). This method provided mean GFP intensity values as an arbitrary unit for each field, at each caspofungin concentration, and for each time point up to 3 h. GFP intensities were normalized so that the values at time zero were the same across all fields and all drug concentrations; the intensity of one field from the experiment with no caspofungin exposure served as the control intensity (100%). Finally, averages for 2 to 3 fields at a given drug concentration were calculated and plotted against time.

Protein extraction and Western blotting.

C. albicans cells were grown to mid-exponential phase in YPD medium, exposed to the drug at the concentrations given below, and incubated at 30°C for the assigned length of time without shaking. Cells were harvested, centrifuged at 4°C, and processed as previously described (22). The protein concentration was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay; equal amounts of protein (50 to 100 μg per lane) were loaded for SDS-PAGE. Following migration and transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, phospho-Mkc1p was detected with anti-phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Additionally, as a loading control, Mkc1p was detected with anti-Mkc1p (kindly provided by Jesús Pla, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain).

Time-kill assays.

Candida cells were grown at 30°C without shaking to simulate the conditions used for live cell imaging in 50-ml tubes with YPD medium (control) or YPD medium containing drug at one of the concentrations given below. At 1, 2, 3, 4, and 20 h, an aliquot was removed, serially diluted, and plated to determine the number of CFU.

RESULTS

Live cell imaging of C. albicans exposed to caspofungin.

We performed 3-h live imaging experiments in which C. albicans SC5314 cells expressing CaPH×2-GFP, immobilized on glass-bottom dishes, were incubated at 30°C in YPD medium supplemented with caspofungin at 4× MIC. The PI(4,5)P2 distribution at aberrant plasma membrane foci was apparent at the earliest imaging time point (3 min). These PI(4,5)P2 foci were highly dynamic and unstable, appearing and disappearing at multiple locations in the vicinity of the plasma membranes of individual cells over 3 h (Fig. 1; see also Video S1 in the supplemental material). The PI(4,5)P2 distribution and dynamics were similar to those described above in C. albicans mkc1-null mutant cells (Fig. 2; see also Video S3 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Live cell imaging of PI(4,5)P2 accumulations. (A) Confocal image of live C. albicans SC5314 cells expressing CaPH×2-GFP exposed to caspofungin (1× MIC), highlighting the early accumulation of PI(4,5)P2 foci (arrows) in the vicinity of the plasma membrane. As indicated, the image was acquired 3 min after exposure to caspofungin. Acq. Time, acquisition time. (B) Time-lapse images of SC5314 cells expressing CaPH×2-GFP during a 3-h exposure to caspofungin (4× MIC), demonstrating the chaotic and highly dynamic nature of aberrant PI(4,5)P2 localization (arrows). Images were acquired at 41, 53, 73, and 89 min after exposure to caspofungin (from left to right and top to bottom, respectively, beginning at the top left).

FIG 2.

The caspofungin-induced redistribution of PI(4,5)P2 is independent of Mkc1 protein kinase. Wild-type DAY286 and mkc1-null mutant VIC1177 strains expressing CaPH×2-GFP were imaged by confocal microscopy for 3 h following exposure to caspofungin (90 ng/ml and 15 ng/ml, respectively). The PI(4,5)P2 redistribution in both strains was similar to that observed in strain SC5314 in response to caspofungin. Arrows, PI(4,5)P2 foci. The acquisition times after caspofungin exposure are indicated. VIC1177 was more sensitive to caspofungin than DAY286; both strains were more sensitive than SC5314. Experiments involving live cell imaging of the response to caspofungin were performed at concentrations ranging from 15 to 600 ng/ml (see also the time lapse videos in the supplemental material).

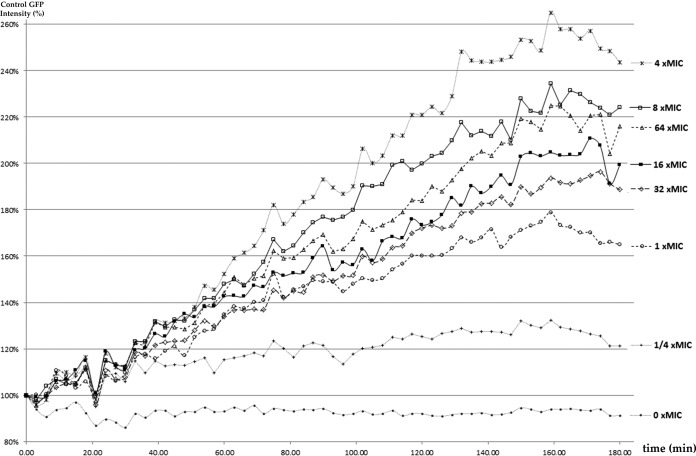

We repeated live cell imaging of C. albicans SC5314 exposed to caspofungin at concentrations ranging from 0.25× to 64× MIC. In the absence of caspofungin, cells grew and divided normally and PI(4,5)P2 was localized throughout the plasma membrane (Fig. 3; see also Video S1 in the supplemental material). At each caspofungin concentration, PI(4,5)P2 levels (measured from the overall intensity of the GFP signal) increased in a roughly linear fashion over time, before reaching a plateau after approximately 2.5 h (Fig. 4). The levels of PI(4,5)P2 increased in a dose-dependent manner at drug concentrations ranging from 0.25× to 4× MIC (Fig. 4; see also Video S1 in the supplemental material). Maximal PI(4,5)P2 accumulation was evident at 4× MIC; steady decrements in PI(4,5)P2 accumulation were obtained as the concentrations increased from 8× to 32× MIC (Fig. 4). PI(4,5)P2 labeling also highlighted the effects of caspofungin on cytokinesis, as cells exhibited broad mother-daughter bud necks and unusually thick and bowed septa (Fig. 5A; see also Video S1 in the supplemental material). In a number of cells, septum-like structures were unidirectional, meandering, and arrested in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5B).

FIG 3.

Live imaging of PI(4,5)P2 within C. albicans cells exposed to caspofungin. Wild-type SC5314 cells expressing CaPH×2-GFP were imaged by confocal microscopy for 3 h following exposure to a range of caspofungin concentrations (0.25× to 64× MIC). Images of representative fields taken from immediately prior to drug exposure (time zero [T0]) and 1, 2, and 3 h after exposure are shown. Images of control cells grown in the absence of caspofungin and cells exposed to 1×, 4×, and 32× MIC are also presented. In control cells, PI(4,5)P2 was distributed regularly throughout the plasma membrane. The PI(4,5)P2 intensity in control cells diminished over the 3-h time frame, due to a dampening of the signal that was consistently observed during growth in the experimental system. In caspofungin-exposed cells, the PI(4,5)P2 intensity increased over time (the results are quantified in Fig. 4), and wide mother-daughter cell necks, thick septa, and aberrant septum-like structures were apparent (detailed in Fig. 5). Abnormal PI(4,5)P2 accumulations were present in the vicinity of the plasma membrane following caspofungin exposure, as shown in greater detail in Fig. 1. Time-lapse videos are provided in the supplemental material.

FIG 4.

Quantification of PI(4,5)P2 levels. GFP intensities over 3 h were measured with Imaris software. The graph presents normalized intensities captured every 3 min in response to the range of caspofungin exposures, with the results being presented as a percentage of the control (no treatment) intensity at time zero. As shown, PI(4,5)P2 levels increased steadily until about 2.5 h at each concentration. The levels increased in a dose-response manner up to a caspofungin concentration of 4× MIC. PI(4,5)P2 levels then decreased in a dose-response manner at concentrations ranging from 8× to 32× MIC. This pattern resembled the paradoxical fungicidal effects of caspofungin at similar concentrations against C. albicans SC5314 and other strains that are well described.

FIG 5.

Cytokinesis and septation during caspofungin exposure. (A) Time-lapse images obtained every 6 min after exposure to caspofungin (4× MIC) reveal broad mother-daughter necks and thick, bowed septa during cytokinesis. (B) Time-lapse images obtained every 3 min after exposure to caspofungin (4× MIC) demonstrate aberrant septation in certain cells. Unidirectional septum-like structures which become arrested in the cytoplasm are visualized.

We then performed live imaging of C. albicans SC5314 cells that coexpressed CaPH×2-GFP and RFP-tagged septin Cdc10p. As anticipated, Cdc10p was highly mobile throughout the cell cycle. Nevertheless, Cdc10p colocalized with PI(4,5)P2 at foci within wide bud necks and aberrant septum-like structures in response to caspofungin (Fig. 6; see also Video S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 6.

Colocalization of PI(4,5)P2 and Cdc10p during caspofungin exposure. C. albicans SC5314 cells coexpressing CaPH×2-GFP and RFP-Cdc10 were imaged by confocal microscopy for 3 h following exposure to 4× MIC caspofungin. PI(4,5)P2 and Cdc10p colocalize (yellow signals) at numerous foci within abnormally wide bud necks and at aberrant plasma membrane foci. Arrows, several examples of colocalization. The acquisition times after caspofungin exposure are indicated. DIC, differential interference contrast; CaRFP, C. albicans-optimized RFP.

Cell wall integrity pathway activation and caspofungin time-kill assays.

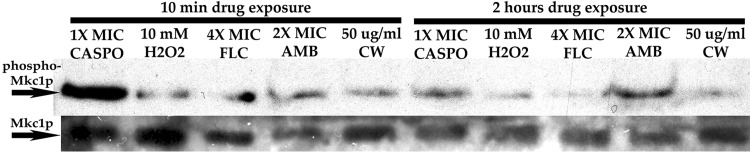

We next measured the time course of Mkc1p phosphorylation in response to caspofungin at 1× MIC, as an assay of PKC-Mkc1 cell wall integrity pathway activation. Pathway activation was striking within 5 min, reached a peak at 10 min, and then declined over 3 h (Fig. 7A). In dose-response experiments, pathway activation at 10 min was progressively stronger as caspofungin concentrations were increased to 4× MIC (Fig. 7B). After peaking at a caspofungin concentration of 4× MIC, pathway activation was progressively weaker at caspofungin concentrations of ≥8 × MIC.

FIG 7.

Cell wall integrity pathway activation in response to caspofungin. (A) C. albicans cells were exposed to caspofungin (CSF; 1× MIC) for 3 h, and Western blotting was performed at the indicated time points using anti-phospho-p44/42 MAP kinase to detect the phosphorylated form of Mkc1p. After caspofungin exposure, Mkc1p was phosphorylated within minutes. Phosphorylation reached a peak at 10 min, after which it was diminished over 3 h. Data were confirmed in two independent experiments. (B) In a dose-ranging experiment, C. albicans cells were exposed to caspofungin (0.5× to 64 × MIC) for 10 min. The intensities of the Western blot bands (bottom) were measured with Adobe Photoshop software, and a graph of the mean values from two independent experiments was plotted (top). There was a dose-response of pathway activation that reached a maximum at 4× MIC. At higher concentrations, pathway activation was attenuated, consistent with paradoxical effects. The bar graph shows mean values and error bars from replicate experiments. In both panels, Mkc1p was detected as a loading control.

We performed time-kill assays at caspofungin concentrations ranging from 0.5× to 64× MIC (2-fold dilutions) under in vitro conditions similar to those used for live cell imaging. By 20 h, caspofungin exerted similar levels of killing at concentrations ranging from 0.5× to 4× MIC (Fig. 8). At concentrations ranging from 8× to 64× MIC, however, caspofungin was less active than at the lower concentrations, in keeping with the previously described paradoxical growth (8).

FIG 8.

Caspofungin time-kill experiments. Time-kill experiments were conducted under in vitro conditions similar to those used for live cell imaging. Killing of C. albicans over 20 h was similar at caspofungin concentrations ranging from 0.5× to 4× MIC. Killing was attenuated at concentrations ranging from 8× to 64× MIC, consistent with the paradoxical fungicidal effects that were demonstrated previously under slightly different growth conditions (5, 8).

Effects of other agents.

In order to determine if our findings represented specific responses to caspofungin or more generalized stress responses, we repeated experiments in the presence of fluconazole (4× MIC), amphotericin B (4× MIC), H2O2 (10 mM), and calcofluor white (50 μg/ml). In the presence of fluconazole, the PI(4,5)P2 distribution, cell morphology, and cytokinesis were not disturbed over 3 h (Fig. 9). The PI(4,5)P2 signal intensity increased, although these effects were not as striking as they were with caspofungin exposure. In the presence of amphotericin B, there was an accumulation of large, dense PI(4,5)P2 accumulations within the cytoplasm of some daughter cells over 2 h. The PI(4,5)P2 distribution patterns were similar at lower amphotericin B concentrations (data not shown). These findings were distinct from the aberrant PI(4,5)P distributions seen in response to caspofungin. As the fungicidal activity of amphotericin B became apparent at 2 h, the overall PI(4,5)P2 signal was dissipated in inviable cells. Cytokinesis and septation among viable cells were not impacted. The results obtained with H2O2 and calcofluor white were largely comparable to those obtained with amphotericin B, as a loss of viability over time was associated with the dissipation of the PI(4,5)P2 signal. However, the distinctive large cytoplasmic accumulations observed with amphotericin B were not evident. Likewise, the PI(4,5)P2 distribution, cell morphology, cytokinesis, and septation abnormalities apparent with caspofungin were not observed. Cdc10p did not colocalize with PI(4,5)P2 at aberrant sites after exposure to any of the agents except caspofungin.

FIG 9.

Live imaging of PI(4,5)P2 within C. albicans cells exposed to various agents. Experiments were conducted as described in the legend to Fig. 3, and images of cells exposed to caspofungin (4× MIC) and the indicated other drugs for 3 h are shown. The abnormalities in PI(4,5)P2 levels, distribution, cell morphology, and cytokinesis and septation that were observed in response to caspofungin were not observed in the presence of the other agents.

Caspofungin was also notable for activating the PKC-Mkc1 cell wall integrity pathway more strongly than any of the other agents at 10 min (Fig. 10).

FIG 10.

Cell wall integrity pathway activation in response to various agents. Western blot experiments were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 5, using cells exposed to caspofungin and other agents. Caspofungin caused greater activation of the cell wall integrity pathway than the other agents, as measured by the intensity of Mkc1p phosphorylation. Mkc1p was detected as a loading control. CASPO, caspofungin; FLC, fluconazole; AMB, amphotericin B; CW, calcofluor white.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated previously that rapid PI(4,5)P2 and septin redistribution plays a role in the natural response of C. albicans to caspofungin (17). In this study, we provide more detailed insights into the relationship between cell wall stress, PI(4,5)P2 and septin regulation, and PKC-Mkc1 cell wall integrity pathway activation. We show that PI(4,5)P2, septin, and PKC-Mkc1 pathway responses to caspofungin are highly dynamic and correlate with the extent of fungicidal activity. PI(4,5)P2 and septin dysregulation, which was evident by their accumulation and chaotic redistribution within aberrant plasma membrane foci, is an early marker of deleterious responses to caspofungin that are associated with subsequent fungicidal effects. These observations are consistent with our reports that C. albicans inp51, irs4, and gin4 mutants, in which PI(4,5)P2 and septins accumulate at plasma membrane sites, are hypersusceptible to caspofungin (17). We show here that attenuation of PI(4,5)P2 dysregulation and PKC-Mkc1 pathway activation at caspofungin concentrations ≥8× MIC are associated with paradoxical growth, rather than enhanced killing. Of note, disruption of the C. albicans PKC-Mkc1 pathway, as in rho1 or mkc1 mutants, also confers caspofungin hypersusceptibility (10, 23, 24). Therefore, a large body of data now supports a model in which both the activation and downregulation of PI(4,5)P2 responses and the cell wall integrity pathway are required for C. albicans viability in the face of β-1,3-d-glucan synthesis inhibition.

The PI(4,5)P2 and septin responses that we observed are caspofungin specific, rather than more generalized reactions to cell wall or plasma membrane stress or to cell death. PI(4,5)P2 accumulation and aberrant plasma membrane foci were evident within 3 min of exposure to caspofungin (our earliest imaging time point) and occurred in a dose-response manner over 3 h at concentrations ≤4× MIC. In contrast, the fungicidal effects of caspofungin were not apparent by time-kill assays under our experimental conditions until after 3 h. Fluconazole (4× MIC), amphotericin B (4× MIC), calcofluor white (50 μg/ml), and H2O2 (10 μg/ml) did not affect PI(4,5)P2 or Cdc10p in a fashion similar to that by which caspofungin affected them, even though the agents are active against plasma membrane or cell wall targets and/or exert fungicidal activity. Our finding that caspofungin maximally activates the C. albicans cell wall integrity pathway within minutes is consistent with the findings of previous studies of MKC1 expression and Mkc1p phosphorylation (10, 25). Like the PI(4,5)P2 responses, Mkc1p phosphorylation was caspofungin dose dependent and correlated with the extent of fungicidal activity and paradoxical growth. As previously reported, PI(4,5)P2 may activate the cell wall integrity pathway directly through interactions with the GTPase Rho1 and the GEF Rom2 upstream of PKC and the MAP kinase cascade (13, 23). A nonmutually exclusive possibility is that PI(4,5)P2 accumulation and mislocalization create their own plasma membrane and cell wall stresses that activate Mkc1p through other mechanisms. In either scenario, the PI(4,5)P2 and septin dysregulation and PKC-Mkc1 activation associated with deleterious outcomes of caspofungin exposure are overexuberant expressions of normally protective responses against cell wall stress.

Based on our data, we propose that PI(4,5)P2 and septins function upstream of Mkc1 in a previously unrecognized cell wall integrity pathway. Indeed, C. albicans has evolved an extensive cell wall regulatory circuitry which is comprised of pathways that are conserved, novel, or rewired compared to those in S. cerevisiae (17, 26–28). C. albicans cell wall responses are regulated, at least in part, through several well-studied networks that operate in parallel but which intercommunicate and provide some measure of redundancy (29–34). PKC-Mkc1, HOG1, and calcineurin pathways work in concert to regulate chitin synthesis, which reinforces the cell wall and promotes echinocandin tolerance (8–10, 27, 30, 33–37). Recent data for S. cerevisiae suggest that PI(4,5)P2, Rho1, and PKC coordinate both septin ring assembly and cell wall integrity responses through pathways that are at least partly independent and that cross talk with one another (38). A C. albicans PI(4,5)P2-septin pathway may promote cell wall stress responses, chitin deposition, and paradoxical growth in the presence of caspofungin through Mkc1 activation and/or localization of chitin synthase by septins.

It is notable that caspofungin at inhibitory concentrations induces aberrant septation and impairs cytokinesis. Although previous studies have described abnormal septa in C. albicans cells exposed to echinocandins (39, 40), the specific defects observed here have not been reported. PI(4,5)P2 and septins play essential roles in cytokinesis in diverse eukaryotes (41, 42), and echinocandins perturb cytokinesis in S. cerevisiae (43). However, reports of the effects of echinocandins on cytokinesis in C. albicans are inconsistent (40, 43). The abnormal septum-like structures that we observed resemble plasma membrane invaginations of C. albicans inp51 and irs4 mutant cells in the absence of caspofungin, within which PI(4,5)P2, septins, chitin, and cell wall material are incorporated (17, 19).

The septation defects observed in the present study are also similar to those seen in S. cerevisiae mutants with mislocalized septins (14, 44–46). The S. cerevisiae septation apparatus, which includes septins and chitin synthase, can function autonomously at ectopic locations independently of cell division (14). Therefore, the data suggest that the caspofungin-induced aberrant septation in C. albicans stems from the redistribution of PI(4,5)P2 and the subsequent recruitment of septins and the septation apparatus. In this light, the plasma membrane foci of PI(4,5)P2, septins, and chitin that were demonstrated in our earlier study may correspond to the early stages of aberrant septation events (17). The broad mother-daughter necks that we observed in this study are reminiscent of the faulty septin and chitin rings seen in S. cerevisiae mutants, in which inhibition of growth at the neck is lost and cytokinesis does not take place (45). C. albicans cells with aberrant septa or impaired cytokinesis due to caspofungin are likely to undergo cell lysis as a consequence of the disturbed cell wall architecture, as described for phenotypically similar S. cerevisiae mutants (44, 45). Alternatively, such cells may be selected to undergo apoptosis, which we have shown is a prominent mechanism by which caspofungin exerts anti-Candida activity in the first hours of exposure (4).

In conclusion, our findings attest to the complexity of caspofungin's fungicidal activity and the compensatory responses of C. albicans to β-1,3-glucan synthesis inhibition and cell wall stress. We show that PI(4,5)P2 and septin regulation and PKC-Mkc1 cell wall integrity pathway activation are finely balanced and that precise modulation of these processes is necessary for optimal adaptation to caspofungin. The PI(4,5)P2 and septin responses in this study were specific to caspofungin and not seen with other cell wall-active agents. We previously demonstrated that strict PI(4,5)P2 regulation is also required for invasive growth into solid agar and the initiation and progression of tissue invasion during hematogenously disseminated C. albicans infections (17–19, 47). Furthermore, maintenance of PI(4,5)P2 plasma membrane gradients is necessary for filamentous growth (48), an important virulence determinant. The experiments described here focused on cells in the yeast morphology, but in our previous study, we showed an aberrant PI(4,5)P2-septin distribution in hyphal cells (17). Taken together, our data lay the foundation for more detailed investigations into the specific mechanisms by which PI(4,5)P2 and septins contribute to cell wall regulatory responses and other clinically relevant phenotypes in C. albicans and other Candida spp. As a sensitive marker for early deleterious responses to echinocandins, the redistribution of PI(4,5)P2 and septin at the plasma membrane may prove to be a useful marker in studies of drug susceptibility, resistance, and tolerance.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02711-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andes DR, Safdar N, Baddley JW, Playford G, Reboli AC, Rex JH, Sobel JD, Pappas PG, Kullberg BJ. 2012. Impact of treatment strategy on outcomes in patients with candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis: a patient-level quantitative review of randomized trials. Clin Infect Dis 54:1110–1122. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cornely OA, Bassetti M, Calandra T, Garbino J, Kullberg BJ, Lortholary O, Meersseman W, Akova M, Arendrup MC, Arikan-Akdagli S, Bille J, Castagnola E, Cuenca-Estrella M, Donnelly JP, Groll AH, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Jensen HE, Lass-Florl C, Petrikkos G, Richardson MD, Roilides E, Verweij PE, Viscoli C, Ullmann AJ. 2012. ESCMID* guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: non-neutropenic adult patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 18(Suppl 7):S19–S37. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eschenauer GA, Nguyen MH, Clancy CJ. 2015. Is fluconazole or an echinocandin the agent of choice for candidemia. Ann Pharmacother 49:1068–1074. doi: 10.1177/1060028015590838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hao B, Cheng S, Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. 2013. Caspofungin kills Candida albicans by causing both cellular apoptosis and necrosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:326–332. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01366-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, Clancy CJ. 2011. Five-minute exposure to caspofungin results in prolonged postantifungal effects and eliminates the paradoxical growth of Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:3598–3602. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00095-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen KT, Ta P, Hoang BT, Cheng S, Hao B, Nguyen MH, Clancy CJ. 2009. Anidulafungin is fungicidal and exerts a variety of postantifungal effects against Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, and C. krusei isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:3347–3352. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01480-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen KT, Ta P, Hoang BT, Cheng S, Hao B, Nguyen MH, Clancy CJ. 2010. Characterising the post-antifungal effects of micafungin against Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida parapsilosis and Candida krusei isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents 35:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Du C, Press E, Cheng S, Clancy CJ. 2011. Paradoxical effect of caspofungin against Candida bloodstream isolates is mediated by multiple pathways but eliminated in human serum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:2641–2647. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00999-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker LA, Munro CA, de Bruijn I, Lenardon MD, McKinnon A, Gow NA. 2008. Stimulation of chitin synthesis rescues Candida albicans from echinocandins. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000040. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiederhold NP, Kontoyiannis DP, Prince RA, Lewis RE. 2005. Attenuation of the activity of caspofungin at high concentrations against Candida albicans: possible role of cell wall integrity and calcineurin pathways. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:5146–5148. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.5146-5148.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strahl T, Thorner J. 2007. Synthesis and function of membrane phosphoinositides in budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta 1771:353–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morales-Johansson H, Jenoe P, Cooke FT, Hall MN. 2004. Negative regulation of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate levels by the INP51-associated proteins TAX4 and IRS4. J Biol Chem 279:39604–39610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405589200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arkowitz RA, Bassilana M. 2014. Rho GTPase-phosphatidylinositol phosphate interplay in fungal cell polarity. Biochem Soc Trans 42:206–211. doi: 10.1042/BST20130226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roh DH, Bowers B, Schmidt M, Cabib E. 2002. The septation apparatus, an autonomous system in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell 13:2747–2759. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeMarini DJ, Adams AE, Fares H, De Virgilio C, Valle G, Chuang JS, Pringle JR. 1997. A septin-based hierarchy of proteins required for localized deposition of chitin in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. J Cell Biol 139:75–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertin A, McMurray MA, Thai L, Garcia G III, Votin V, Grob P, Allyn T, Thorner J, Nogales E. 2010. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate promotes budding yeast septin filament assembly and organization. J Mol Biol 404:711–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Badrane H, Nguyen MH, Blankenship JR, Cheng S, Hao B, Mitchell AP, Clancy CJ. 2012. Rapid redistribution of phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate and septins during the Candida albicans response to caspofungin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:4614–4624. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00112-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badrane H, Cheng S, Nguyen MH, Jia HY, Zhang Z, Weisner N, Clancy CJ. 2005. Candida albicans IRS4 contributes to hyphal formation and virulence after the initial stages of disseminated candidiasis. Microbiology 151:2923–2931. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27998-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badrane H, Nguyen MH, Cheng S, Kumar V, Derendorf H, Iczkowski KA, Clancy CJ. 2008. The Candida albicans phosphatase Inp51p interacts with the EH domain protein Irs4p, regulates phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate levels and influences hyphal formation, the cell integrity pathway and virulence. Microbiology 154:3296–3308. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harlan JE, Hajduk PJ, Yoon HS, Fesik SW. 1994. Pleckstrin homology domains bind to phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Nature 371:168–170. doi: 10.1038/371168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hao B, Clancy CJ, Cheng S, Raman SB, Iczkowski KA, Nguyen MH. 2009. Candida albicans RFX2 encodes a DNA binding protein involved in DNA damage responses, morphogenesis, and virulence. Eukaryot Cell 8:627–639. doi: 10.1128/EC.00246-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navarro-Garcia F, Alonso-Monge R, Rico H, Pla J, Sentandreu R, Nombela C. 1998. A role for the MAP kinase gene MKC1 in cell wall construction and morphological transitions in Candida albicans. Microbiology 144(Pt 2):411–424. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-2-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corvest V, Bogliolo S, Follette P, Arkowitz RA, Bassilana M. 2013. Spatiotemporal regulation of Rho1 and Cdc42 activity during Candida albicans filamentous growth. Mol Microbiol 89:626–648. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu D, Jiang B, Ketela T, Lemieux S, Veillette K, Martel N, Davison J, Sillaots S, Trosok S, Bachewich C, Bussey H, Youngman P, Roemer T. 2007. Genome-wide fitness test and mechanism-of-action studies of inhibitory compounds in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 3:e92. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leach MD, Stead DA, Argo E, Brown AJ. 2011. Identification of sumoylation targets, combined with inactivation of SMT3, reveals the impact of sumoylation upon growth, morphology, and stress resistance in the pathogen Candida albicans. Mol Biol Cell 22:687–702. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blankenship JR, Fanning S, Hamaker JJ, Mitchell AP. 2010. An extensive circuitry for cell wall regulation in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000752. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bruno VM, Kalachikov S, Subaran R, Nobile CJ, Kyratsous C, Mitchell AP. 2006. Control of the C. albicans cell wall damage response by transcriptional regulator Cas5. PLoS Pathog 2:e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finkel JS, Xu W, Huang D, Hill EM, Desai JV, Woolford CA, Nett JE, Taff H, Norice CT, Andes DR, Lanni F, Mitchell AP. 2012. Portrait of Candida albicans adherence regulators. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002525. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinoso-Martin C, Schuller C, Schuetzer-Muehlbauer M, Kuchler K. 2003. The yeast protein kinase C cell integrity pathway mediates tolerance to the antifungal drug caspofungin through activation of Slt2p mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. Eukaryot Cell 2:1200–1210. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.6.1200-1210.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh SD, Robbins N, Zaas AK, Schell WA, Perfect JR, Cowen LE. 2009. Hsp90 governs echinocandin resistance in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans via calcineurin. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000532. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monge RA, Roman E, Nombela C, Pla J. 2006. The MAP kinase signal transduction network in Candida albicans. Microbiology 152:905–912. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28616-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LaFayette SL, Collins C, Zaas AK, Schell WA, Betancourt-Quiroz M, Gunatilaka AA, Perfect JR, Cowen LE. 2010. PKC signaling regulates drug resistance of the fungal pathogen Candida albicans via circuitry comprised of Mkc1, calcineurin, and Hsp90. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001069. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munro CA, Selvaggini S, de Bruijn I, Walker L, Lenardon MD, Gerssen B, Milne S, Brown AJ, Gow NA. 2007. The PKC, HOG and Ca2+ signalling pathways co-ordinately regulate chitin synthesis in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol 63:1399–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heilmann CJ, Sorgo AG, Mohammadi S, Sosinska GJ, de Koster CG, Brul S, de Koning LJ, Klis FM. 2013. Surface stress induces a conserved cell wall stress response in the pathogenic fungus Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell 12:254–264. doi: 10.1128/EC.00278-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anonymous. 1988. NCCLS proposes HIV reference material specifications. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Clin Chem 34:1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rauceo JM, Blankenship JR, Fanning S, Hamaker JJ, Deneault JS, Smith FJ, Nantel A, Mitchell AP. 2008. Regulation of the Candida albicans cell wall damage response by transcription factor Sko1 and PAS kinase Psk1. Mol Biol Cell 19:2741–2751. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vasicek EM, Berkow EL, Bruno VM, Mitchell AP, Wiederhold NP, Barker KS, Rogers PD. 2014. Disruption of the transcriptional regulator Cas5 results in enhanced killing of Candida albicans by fluconazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:6807–6818. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00064-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Merlini L, Bolognesi A, Juanes MA, Vandermoere F, Courtellemont T, Pascolutti R, Seveno M, Barral Y, Piatti S. 2015. Rho1- and Pkc1-dependent phosphorylation of the F-BAR protein Syp1 contributes to septin ring assembly. Mol Biol Cell 26:3245–3262. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-06-0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bizerra FC, Melo AS, Katchburian E, Freymuller E, Straus AH, Takahashi HK, Colombo AL. 2011. Changes in cell wall synthesis and ultrastructure during paradoxical growth effect of caspofungin on four different Candida species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:302–310. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00633-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishiyama Y, Uchida K, Yamaguchi H. 2002. Morphological changes of Candida albicans induced by micafungin (FK463), a water-soluble echinocandin-like lipopeptide. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo) 51:247–255. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/51.4.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Echard A. 2012. Phosphoinositides and cytokinesis: the “PIP” of the iceberg. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 69:893–912. doi: 10.1002/cm.21067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brill JA, Wong R, Wilde A. 2011. Phosphoinositide function in cytokinesis. Curr Biol 21:R930–R934. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Formosa C, Schiavone M, Martin-Yken H, Francois JM, Duval RE, Dague E. 2013. Nanoscale effects of caspofungin against two yeast species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3498–3506. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00105-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cid VJ, Adamikova L, Cenamor R, Molina M, Sanchez M, Nombela C. 1998. Cell integrity and morphogenesis in a budding yeast septin mutant. Microbiology 144(Pt 12):3463–3474. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-12-3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmidt M, Bowers B, Varma A, Roh DH, Cabib E. 2002. In budding yeast, contraction of the actomyosin ring and formation of the primary septum at cytokinesis depend on each other. J Cell Sci 115:293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slater ML, Bowers B, Cabib E. 1985. Formation of septum-like structures at locations remote from the budding sites in cytokinesis-defective mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol 162:763–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raman SB, Nguyen MH, Cheng S, Badrane H, Iczkowski KA, Wegener M, Gaffen SL, Mitchell AP, Clancy CJ. 2013. A competitive infection model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis in mice redefines the role of Candida albicans IRS4 in pathogenesis. Infect Immun 81:1430–1438. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00743-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vernay A, Schaub S, Guillas I, Bassilana M, Arkowitz RA. 2012. A steep phosphoinositide bis-phosphate gradient forms during fungal filamentous growth. J Cell Biol 198:711–730. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.