Abstract

The emergence and spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum is of huge concern for the global effort toward malaria control and elimination. Artemisinin resistance, defined as a delayed time to parasite clearance following administration of artemisinin, is associated with mutations in the Pfkelch13 gene of resistant parasites. To date, as many as 60 nonsynonymous mutations have been identified in this gene, but whether these mutations have been selected by artemisinin usage or merely reflect natural polymorphism independent of selection is currently unknown. To clarify this, we sequenced the Pfkelch13 propeller domain in 581 isolates collected before (420 isolates) and after (161 isolates) the implementation of artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs), from various regions of endemicity worldwide. Nonsynonymous mutations were observed in 1% of parasites isolated prior to the introduction of ACTs. Frequencies of mutant isolates, nucleotide diversity, and haplotype diversity were significantly higher in the parasites isolated from populations exposed to artemisinin than in those from populations that had not been exposed to the drug. In the artemisinin-exposed population, a significant excess of dN compared to dS was observed, suggesting the presence of positive selection. In contrast, pairwise comparison of dN and dS and the McDonald and Kreitman test indicate that purifying selection acts on the Pfkelch13 propeller domain in populations not exposed to ACTs. These population genetic analyses reveal a low baseline of Pfkelch13 polymorphism, probably due to purifying selection in the absence of artemisinin selection. In contrast, various Pfkelch13 mutations have been selected under artemisinin pressure.

INTRODUCTION

Artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs) are used as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria in most regions of endemicity (1). The introduction of ACTs has been instrumental in driving the considerable decrease in mortality and morbidity due to malaria in recent years (2). However, since the report of the emergence of two artemisinin-resistant cases from west Cambodia in 2006-2007 (3), there has been a steady increase in the numbers of cases, and range, of infections with apparently artemisinin-resistant parasites (4). Artemisinin-resistant parasites have unique phenotypic characteristics, i.e., slow parasite clearance after treatment in vivo and increased survival rates in in vitro ring stage survival assays (5). Currently, measuring ring stage survival following a short exposure to 700 nM dihydroartemisinin is the most reliable ex vivo method for the assessment of artemisinin resistance (5).

In 2014, Ariey et al. identified an artemisinin resistance candidate gene in Plasmodium falciparum, Pfkelch13, which encodes a 726-amino-acid protein containing a BTB/POZ domain and a C-terminal 6-blade propeller domain (6). Single amino acid changes in the Pfkelch13 propeller domain are associated with both in vivo and ex vivo artemisinin resistance (6). Shortly thereafter, Straimer et al. showed that insertion of particular mutations (M476I, Y493H, R539T, I543T, or C580Y) into the Pfkelch13 gene of an artemisinin-susceptible P. falciparum clone (Dd2) increased ring stage survival rates from 0.6% to 2 to 29% in the in vitro ring stage survival assay, and reversal of Pfkelch13 mutations (R539T, I543T, and C580Y) in artemisinin-resistant clones decreased ring stage survival rates from 13 to 49% to 0.3 to 2.4% (7). Furthermore, large-scale in vivo studies conducted in 10 counties in Africa and Asia have revealed that around 20 nonsynonymous mutations in Pfkelch13 are associated with delayed parasite clearance following artemisinin treatment (8).

Molecular epidemiological analyses have identified as many as 60 nonsynonymous mutations in Pfkelch13 so far, but whether these mutations have been selected by the recent increase of artemisinin usage or merely reflect high natural polymorphism independent of selection is currently unknown. To elucidate this, baseline information of the distribution of Pfkelch13 polymorphism before the implementation of ACTs is required. In this study, we sequenced the Pfkelch13 propeller domain from 581 P. falciparum isolates obtained from Asia, Africa, Melanesia, and South America. All parasites examined here were isolated before the first report of artemisinin resistance in 2006-2007 (3), 420 of which were collected before the implementation of ACTs and 161 during the very early phase of artemisinin usage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sites.

P. falciparum-infected blood samples were obtained from patients of all ages in 14 countries where malaria is endemic, covering a large range of regions of endemicity: Bangladesh, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, Lao People's Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Kenya, Tanzania, Republic of the Congo, Ghana, and Brazil. Sampling year, number, and area are described in Table 1. Other detailed sampling information was described previously (9–16). All studies but one (Bangladesh) were conducted before the first report of artemisinin resistance from west Cambodia in 2006-2007 (3). Samples from Bangladesh were obtained at almost the same time as the first identification of artemisinin resistance. ACTs were not officially implemented in all studied countries except Cambodia and Thailand at the time of sample collection. In Bangladesh, although ACT was officially introduced as the first-line treatment for confirmed P. falciparum cases in 2004, it was implemented in the health facilities in rural areas in the latter half of 2007 (15).

TABLE 1.

Plasmodium falciparum isolates from 14 countries used in this study

| Country | Area | No. of isolates | Yr(s) of sampling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cambodia | Chumkiri, Kampot | 41 | 2004, 2005, 2006 |

| Thailand | Tak, Kanchanaburi, Ratchaburi | 50 | 2001–2002 |

| Myanmar | Bago | 70 | 2002–2005 |

| Bangladesh | Bandarban | 35 | 2007 |

| Lao PDR | Khammouanne | 12 | 1999 |

| Philippines | Palawan Island | 34 | 1997 |

| Papua New Guinea | East Sepik | 60 | 2002, 2003 |

| Solomon Islands | Guadalcanal Island | 41 | 1995–1996 |

| Vanuatu | Gaua, Santo, Pentecost, Malakula | 49 | 1996, 1998 |

| Kenya | Kisii | 60 | 1998 |

| Tanzania | Rufiji River Delta | 36 | 1998, 2003 |

| Republic of Congo | Pointe-Noire, Brazzaville, Gamboma | 30 | 2006 |

| Ghana | Winneba | 32 | 2004 |

| Brazil | Acre | 31 | 1985–1986, 1999, 2004–2005 |

| Total | 581 |

The study was approved by the Bangladesh Medical Research Council and the local health regulatory body in Bandarban, Bangladesh, the National Center for Parasitology, Entomology, and Malaria Control of Cambodia, the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, the ethical committees of Military Institute of Nursing and Paramedical Sciences in Myanmar, the Laos Ministry of Health, the Palawan Provincial Health Office, the National Department of Health Medical Research Advisory Committee of Papua New Guinea, the Vanuatu Department of Health, the Kenyan Ministry of Health and Education, the Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Medical Research of Tanzania, the Ministry of Research and Ministry of Health of the Republic of the Congo, the Ministry of Health/Ghana Health Service, and the ethics review board of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of São Paulo. In all study sites, informed consent was obtained from individual patients or their guardians and antimalarial treatment was provided if necessary.

Determination of polymorphisms in Pfkelch13.

Blood samples were collected and transferred to filter paper (ET31CHR; Whatman) in all regions. Parasite DNA was purified using the QIAamp DNA blood minikit (Qiagen) or the QIAcube (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The presence of P. falciparum parasites was confirmed by nested PCR (17). An 858-bp portion of the Pfkelch13 gene was sequenced as previously described (6), which covers almost the entire sequence of the six propeller domains. In brief, nested-PCR products were purified using the ExoSAP-IT kit (Affymetrix USB, Cleveland, OH, USA) and were directly sequenced (96°C for 1 min and 25 cycles of 96°C for 10 s, 50°C for 5 s, and 60°C for 4 min) in two directions using the BigDye Terminator v1.1 cycle sequencing kit and the 3130xl genetic analyzer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Eleven samples were found to harbor mixed infections based on the presence of two chromatogram peaks at a single nucleotide site. As each of the 11 samples contained only two allelic types, they were considered to harbor two strains, both of which were included in the analysis.

Sequences of the propeller domain of Pfkelch13 were aligned using MUSCLE (18) implemented in MEGA version 6.0 (19). The sequence from strain 3D7 (PlasmoDB gene identification no. PF3D7_1343700) was used as the reference in the numbering of nucleotide and amino acid positions. Haplotype diversity (h) was calculated as h = [n/(n − 1)] (1 − Σpi2), where n is the number of infections sampled and pi is the frequency of the ith haplotype in a group. The difference in h between groups was evaluated by a permutation test with 10,000 random shuffles.

Molecular evolutionary analysis.

For estimation of nucleotide diversity, the average pairwise nucleotide diversity (π) and the standardized number of polymorphic sites per site (S; Watterson's estimator) were measured using DnaSP version 5.10 (20). The McDonald-Kreitman (MK) test was used to infer the presence of positive or purifying selection acting on the sequenced region of Pfkelch13 (21). A Pfkelch13 sequence from the most related species, P. reichenowi (PRCDC_1342700), was used for interspecies comparison. This test is based on comparison between the ratio of interspecies fixed nonsynonymous substitutions to synonymous substitutions and that of intraspecific nonsynonymous substitutions to synonymous substitutions. These ratios should be the same under neutrality. A higher ratio between species than within species is suggestive of positive selection. In contrast, a higher ratio within species than between species is suggestive of purifying selection. Fisher's exact test was used to test for statistical significance.

The number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (dN) and the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS) was estimated by the Nei and Gojobori method (22) with the Jukes and Cantor correlation as implemented in MEGA version 6 (19). The ratio of dN to dS was used to identify positive or purifying selection acting on Pfkelch13. If dS is significantly higher than dN, purifying selection may be acting, while if dN is higher than dS, positive selection is inferred. A one-sample t test was used to test the null hypothesis that the difference between dN and dS is equal to 0.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The sequences determined in this study have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases (accession no. LC085954 to LC085970).

RESULTS

Polymorphisms in Pfkelch13 and geographical distribution.

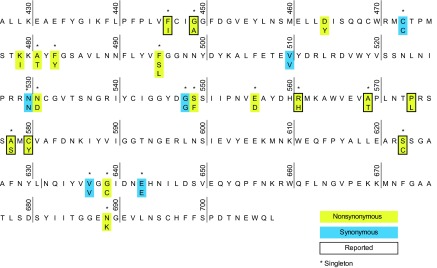

The sequence of Pfkelch13 gene from amino acid positions 427 to 708 was determined for 581 P. falciparum isolates (Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). Among the 25 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (19 nonsynonymous SNPs and 6 synonymous SNPs), 20 SNPs (80%) were observed as singletons. A total of 8 SNPs (32%) were previously reported. Among these, three SNPs (G449A, R561H, and C580Y) were reported to be associated with delayed parasite clearance times following administration of artemisinin (8, 23). The C580Y mutation was observed only in Cambodia, where its frequency was 22%, despite the fact that the samples were obtained prior to the first report of artemisinin resistance. Both G449A and R561H polymorphisms were observed as singletons in Myanmar.

FIG 1.

Polymorphism in the Plasmodium falciparum Kelch13 propeller domain from worldwide parasite populations taken before the first report of artemisinin resistance. Nonsynonymous substitutions and synonymous substitutions observed in 581 samples examined in this study are colored in yellow and blue, respectively. The sequence from strain 3D7 (PlasmoDB, PF3D7_1343700) is used as a reference. Substitutions reported by other investigators are framed by a bold line. *, singleton.

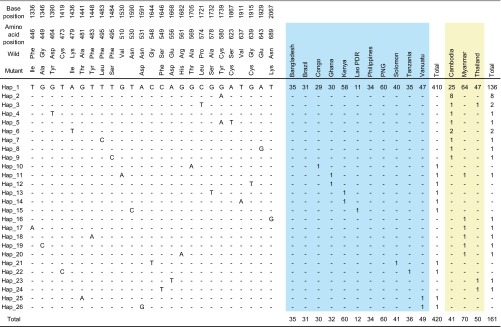

In total, there were 26 nucleotide haplotypes in our sample set (Fig. 2). Nearly all haplotypes harbored only one mutation. One exception is haplotype 5, which possessed two nonsynonymous mutations at positions 580 and 623. Nearly all parasites (94%) harbored a wild type (haplotype 1, strain 3D7) in all countries. Haplotype 2, containing C580Y, was the next most prevalent haplotype (n = 8) and was distributed exclusively in Cambodia. All the other haplotypes except two (haplotypes 3 and 6) were present in only a single isolate each.

FIG 2.

Haplotypes of Pfkelch13 observed in 581 worldwide Plasmodium falciparum isolates. Nucleotide and amino acid positions are numbered according to the strain 3D7 sequence (PF3D7_1343700).

Next, we divided the samples into two groups according to the levels of artemisinin pressure in the study areas (Fig. 2). A total of 420 isolates were obtained from 11 regions with no or very low artemisinin usage at the time of sampling (artemisinin-Neg), including Bangladesh, Lao PDR, Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Kenya, Tanzania, Republic of the Congo, Ghana, and Brazil. The remaining 161 isolates were from three regions with considerable artemisinin usage at the time of sampling (artemisinin-Pos), including Cambodia, Thailand, and Myanmar. A marked difference was observed between the two groups. The prevalence of parasites harboring nonsynonymous mutations in Pfkelch13 was significantly higher in the artemisinin-Pos group (23/161, 14%) than in the artemisinin-Neg group (5/420, 1%) (P < 0.0001 by Fisher's exact test). Consistent with this, haplotype diversity was significantly higher in the artemisinin-Pos group (0.285) than in the artemisinin-Neg group (0.047) (P < 10−4 by permutation test) (Table 2). In particular, a remarkably high degree (0.599) of haplotype diversity compared to the other countries (0 to 0.167) was found in Cambodia, where the strongest artemisinin pressure was expected at the time of sampling. Collectively, these observations indicate that the frequency of Pfkelch13 mutant parasites may have increased in relation to artemisinin usage, perhaps due to a fitness advantage of the parasites harboring Pfkelch13 mutations under such circumstances.

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide diversity and amino acid haplotypes of the Kelch13 propeller in 420 Plasmodium falciparum isolates taken before the introduction of ACTs

| Exposure to artemisinins and geographic area | Nucleotide diversity (mean ± SD) |

No. of amino acid haplotypes | ha (mean ± SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| θp | θs | |||

| No exposure | ||||

| Overall | 0.00006 ± 0.00002 | 0.00201 ± 0.00063 | 11 | 0.047 ± 0.014 |

| Congo | 0.00009 ± 0.00008 | 0.00034 ± 0.00034 | 2 | 0.067 ± 0.061 |

| Ghana | 0.00017 ± 0.00011 | 0.00066 ± 0.00047 | 3 | 0.123 ± 0.078 |

| Kenya | 0.00009 ± 0.00006 | 0.00057 ± 0.00040 | 3 | 0.066 ± 0.044 |

| Tanzania | 0.00007 ± 0.00007 | 0.00032 ± 0.00032 | 2 | 0.056 ± 0.052 |

| Lao PDR | 0.00022 ± 0.00018 | 0.00044 ± 0.00044 | 2 | 0.167 ± 0.134 |

| Bangladesh | 0.00000 ± 0.00000 | 0.00000 ± 0.00000 | 0 | 0.000 ± 0.000 |

| Philippines | 0.00000 ± 0.00000 | 0.00000 ± 0.00000 | 0 | 0.000 ± 0.000 |

| Papua New Guinea | 0.00000 ± 0.00000 | 0.00000 ± 0.00000 | 0 | 0.000 ± 0.000 |

| Solomon Islands | 0.00007 ± 0.00007 | 0.00031 ± 0.00032 | 2 | 0.049 ± 0.046 |

| Vanuatu | 0.00011 ± 0.00007 | 0.00060 ± 0.00042 | 3 | 0.081 ± 0.053 |

| Brazil | 0.00000 ± 0.00000 | 0.00000 ± 0.00000 | 0 | 0.000 ± 0.000 |

| Exposure | ||||

| Overall | 0.00042 ± 0.00008 | 0.00376 ± 0.00094 | 17 | 0.285 ± 0.047 |

| Cambodia | 0.00098 ± 0.00017 | 0.00248 ± 0.00088 | 9 | 0.599 ± 0.078 |

| Thailand | 0.00016 ± 0.00009 | 0.00089 ± 0.00051 | 4 | 0.118 ± 0.062 |

| Myanmar | 0.00023 ± 0.00009 | 0.00165 ± 0.00068 | 7 | 0.165 ± 0.054 |

h, haplotype diversity.

Nucleotide diversity.

We used two population genetic indices for the assessment of nucleotide diversity, i.e., θπ, the average pairwise nucleotide distance, and θS, the standardized number of polymorphic sites per site (Table 2). In all studied countries, θπ was lower than θS, which reflects the observation that most SNPs were rare alleles. The highest θπ (0.00098) was observed in Cambodia. Overall, nucleotide diversity was higher in the artemisinin-Pos group (0.00016 to 0.00098) than in the artemisinin-Neg group (0 to 0.00017), again suggesting the increase of nucleotide diversity in Pfkelch13 in the presence of artemisinin-selecting pressure.

Population genetic analysis.

It may be possible that the observed low level of nucleotide diversity in the artemisinin-Neg group is due to purifying selection acting on the Pfkelch13 propeller domain. To test this possibility, we performed a McDonald and Kreitman test using the most closely related species to P. falciparum with full genome data, Plasmodium reichenowi (PRCDC_1342700), for the interspecies comparison. We found a significant abundance of intraspecific nonsynonymous substitutions to synonymous substitutions compared to interspecies fixed nonsynonymous substitutions to synonymous substitutions (P = 0.0325 by Fisher's exact test) (Table 3). Pairwise comparison of dN and dS (n = 420, 87,990 pairs) also revealed a significant excess of dS compared with dN (P = 1.6 × 10−218 by one-sample t test). These two observations clearly indicate that the Pfkelch13 propeller domain is conserved, suggesting strong purifying selection acting on this domain. In support of this, pairwise comparison of eight closely related Plasmodium species pairs (P. falciparum, P. reichenowi, P. vivax, P. cynomolgi, P. knowlesi, P. berghei, and P. chabaudi) also showed low dN/dS ratios (0.0152 to 0.1071) (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 3.

Natural selection acting on Kelch13 in artemisinin-unexposed and -exposed P. falciparum populations

| Exposure to artemisinins | No. of P. falciparum isolates | McDonald and Kreitman test result |

Nucleotide divergence |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interspecies fixed difference |

Intraspecific difference |

P value | Substitution rate (per site) |

P value | |||||

| Synonymous | Nonsynonymous | Synonymous | Nonsynonymous | dS ± SD | dN ± SD | ||||

| Unexposed | 420 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0.0325 | 0.02225 ± 0.00995 | 0.00974 ± 0.00432 | dS > dN, 1.6 × 10−218 |

| Exposed | 161 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 0.000012 | 0.01285 ± 0.00970 | 0.02545 ± 0.00706 | dN > dS, 1.2 × 10−193 |

We next sought to examine the impact of artemisinin selection pressure in the parasite population, again by pairwise comparison of dN and dS in the artemisinin-Pos groups (n = 161, 12,880 pairs). In contrast to the result in the artemisinin-Neg group, a significant excess of dN compared with dS was detected (P = 1.2 × 10−193 by one-sample t test), suggesting the presence of positive selection, perhaps produced by the increased artemisinin pressure.

These results demonstrate that Pfkelch13 is conserved among Plasmodium species. In the populations not exposed to ACTs, intraspecific polymorphisms were extremely rare, probably due to purifying selection. In contrast, high levels of nucleotide diversity were observed with the evidence of positive selection in the samples that were exposed to ACTs but obtained before the first report of artemisinin resistance in 2006-2007 (3).

DISCUSSION

In the present molecular epidemiological and population genetic analysis, we determined a baseline for polymorphisms in the propeller region of the Pfkelch13 gene using 420 global P. falciparum samples isolated prior to the introduction of artemisinin derivatives. There were only five nonsynonymous mutations, two of which (A569T and A578S) have been previously described. Of these, A569T was previously observed only in Kenya, where it was present in a single sample, as in our analysis (24). In contrast, the A578S polymorphism is present in Africa (8, 24–28) and Bangladesh (29). Conflicting findings have been reported regarding the role of A578S in artemisinin resistance (8, 26, 30). Previous computational modeling using the betapropeller domain of the btb-kelch protein krp1 (PDB ID 2WOZ) suggested that a structural change induced by the A578S mutation potentially disrupts the normal function of the Pfkelch13 protein (29). Since this mutation is one of the most prevalent mutations in Africa, where emergence of artemisinin resistance has not been observed, this mutation may not be associated with artemisinin resistance (8, 25). However, one report has linked this mutation to possible artemisinin resistance, although the sample size was very small (26). Further elucidation of the role of the A578S mutation is warranted.

One of the parasites from Cambodia carried two mutations in Pfkelch13. Such cases appear to be rare, although two previous studies have described Pfkelch13 double mutants: P574L F446I from the China-Myanmar border (31) and G548S G595S and R575G G639V from Mali (32).

We found that purifying selection was acting on the propeller domain of Pfkelch13. The average nucleotide diversities in Pfkelch13 were much lower than those in the two P. falciparum housekeeping genes, P type Ca2+-ATPase (serca) and adenylosuccinatelyase (adsl), that we previously reported (33), suggesting that the intensity of purifying selection on Pfkelch13 appears to be much stronger than that on serca and adsl (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). This further suggests that the Pfkelch13 protein is functionally constrained. Very recently, dihydroartemisinin, a bioactive derivative of artemisinin, has been reported to be a potent inhibitor of P. falciparum phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PfPI3K) (34). PfPI3K phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol (PI) to produce phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P), which promotes cell signaling for parasite survival such as inhibition of apoptosis. Hence, inhibition of PfPI3K activity by dihydroartemisinin causes a reduction in PI3P level and subsequently leads to parasite death. Likewise, Pfkelch13 is proposed to act as a PfPI3K inhibitor. Therefore, decreased binding affinity of mutant Pfkelch13 to PfPI3K can further increase PfPI3K activity. This may compensate for its kinase activity, which is inhibited by dihydroartemisinin, and confer artemisinin resistance. In fact, introduction of C580Y into an artemisinin-sensitive laboratory clone strain (NF54) increased the amount of PfPI3K 1.5-fold and resulted in the acquisition of resistance against dihydroartemisinin (34).

The artemisinin resistance-associated mutations that occur in Pfkelch13 confer structural changes to the protein that affect its function. It is possible that such mutations confer a fitness cost to parasites in the absence of artemisinin pressure (35). This supposition is supported by the fact that in parasite populations not exposed to artemisinin, there is strong purifying selection acting on the gene, indicative of functional constraint. A genome-wide association study incorporating isolates from Southeast Asia and Africa identified genomic loci that were strongly associated with a delay in parasite clearance following artemisinin treatment, including fd (ferredoxin), arps10 (apicoplast ribosomal protein S10), mdr2 (multidrug resistance protein 2), and pfcrt (chloroquine resistance transporter) (36). It is possible that mutations within these genes might be necessary for the survival of parasites carrying artemisinin resistance-associated mutations in the Pfkelch13 gene in the absence of artemisinin selection pressure. This could explain the observation that artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum has emerged multiple times in Southeast Asia, where polymorphisms of these loci were prevalent, but not in Africa, where nearly all of these loci are of the wild type (36–38). Laboratory studies have shown, however, that African parasites can display reduced sensitivity to artemisinin when specific mutations are artificially induced in Pfkelch13 (7). The relative fitness of these parasites was not assessed, however, and it is possible that fitness costs incurred through these mutations would render the parasites unable to compete with wild-type parasites in the typical African environment of high transmission, without additional mutations in other genes.

Parasite populations under artemisinin pressure (Cambodia, Myanmar, and Thailand) showed much higher frequencies of Pfkelch13 mutant parasites and nucleotide diversity within the gene than those isolated from regions without, or with very little, artemisinin usage. Positive selection was observed acting on the Pfkelch13 propeller domain in these regions, which, taken together with the evidence for the role of Pfkelch13 in modulating artemisinin resistance, suggests that mutations in this gene are selected through artemisinin pressure. This evolutionary pattern is in sharp contrast to that observed in chloroquine and SP resistance. In pfcrt, dhfr, and dhps, a limited number of key mutations were selected in the presence of pressure induced by the relevant drug (39). In contrast, as many as 60 nonsynonymous mutations have been reported in the propeller domain of Pfkelch13. Among these, five mutations (M476I, Y493H, R539T, I543T, and C580Y) have been shown to confer artemisinin resistance by laboratory studies (7), whereas the role of the other polymorphisms remains unknown. Of particular interest, the C580Y mutation is the most prevalent in parasite populations under artemisinin pressure, despite the fact that other mutations (M476I, R539T, and I543T) have been shown to confer stronger in vitro artemisinin resistance (7). In general, the most successful mutation in the population will be determined by many factors, including levels of in vivo resistance, parasite fitness, and environmental factors such as the intensity of artemisinin pressure, the intensity of transmission, and interactions among these factors. Various mutations in Pfkelch13 appear to be able to coexist in the early stages of the evolutionary process of artemisinin resistance selection; most mutations might then be gradually outcompeted by a limited number of the most fit mutation(s) during the course of natural selection (40). If it is the case, continuous assessment of allele frequencies in Pfkelch13 worldwide may assist the elucidation of the “key mutations” for artemisinin resistance.

Molecular markers for drug resistance in malaria parasites are highly important, as in regions with high transmission rates, resistant parasites may not be observed clinically due to the masking effects of host immunity (41). This current study shows that the C580Y mutation was already prevalent several years before the first clinical report of artemisinin resistance in 2007 (3), supporting a previous report (6). In particular, as much as 20% of parasites carried this mutation in Cambodia. This finding suggests that molecular epidemiological assessment of Pfkelch13 genotypes might potentially detect the selection of particular mutations for artemisinin resistance before clinical identification of reduced parasite response to artemisinin.

In summary, our molecular epidemiological survey of populations not exposed to ACTs provides basic information for Pfkelch13 as a molecular marker of artemisinin resistance. SNPs were observed in most cases in single isolates and were different from those SNPs that have been shown to confer resistance. Continuous assessment of polymorphisms in the propeller domain of Pfkelch13 will be required to assess which SNPs are crucial for the development of clinical resistance to artemisinin and to map the spread and evolution of artemisinin resistance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all the patients, all the local staff, and all the participating staff for assistance with sample collection and Maiko Okochi and Hanako Yoshitake for technical assistance. T.M., R.C., A.B., H.E., and J.O. designed the research; M.N., T.T., Z.Z.W., W.W.H., A.S.M., L.D., M.N., M.D., W.S.A., J.K., A.K., F.H., and M.U.F. performed field surveys; N.T., C.W.H., and H.U. performed laboratory work; T.M. and J.O. analyzed the data; and T.M., R.C., and J.O. wrote the paper.

Funding Statement

This work, including the efforts of Toshihiro Mita, was funded by Cooperative Research Grants of NEKKEN, Japan (25-Ippan-05 and 26-Ippan-11), the Foundation of Strategic Research Projects in Private Universities (S0991013), grants-in-aid from scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (23659211 and 23590498), and Health and Labour Science Research Grants from Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, Japan (H26-Iryokiki-Ippan-004). This work, including the efforts of Marcelo U. Ferreira, was funded by Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo (grant 98/14587-1).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02370-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO. 2014. World malaria report 2014. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eastman RT, Fidock DA. 2009. Artemisinin-based combination therapies: a vital tool in efforts to eliminate malaria. Nat Rev Microbiol 7:864–874. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noedl H, Se Y, Schaecher K, Smith BL, Socheat D, Fukuda MM, Artemisinin Resistance in Cambodia 1 Study Consortium. 2008. Evidence of artemisinin-resistant malaria in western Cambodia. N Engl J Med 359:2619–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0805011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. 2013. Emergency response to artemisinin resistance in the Greater Mekong subregion. Regional Framework for Action 2013–2015. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Khim N, Sreng S, Chim P, Kim S, Lim P, Mao S, Sopha C, Sam B, Anderson JM, Duong S, Chuor CM, Taylor WR, Suon S, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Fairhurst RM, Menard D. 2013. Novel phenotypic assays for the detection of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Cambodia: in-vitro and ex-vivo drug-response studies. Lancet Infect Dis 13:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70252-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ariey F, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Beghain J, Langlois AC, Khim N, Kim S, Duru V, Bouchier C, Ma L, Lim P, Leang R, Duong S, Sreng S, Suon S, Chuor CM, Bout DM, Menard S, Rogers WO, Genton B, Fandeur T, Miotto O, Ringwald P, Le Bras J, Berry A, Barale JC, Fairhurst RM, Benoit-Vical F, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Menard D. 2014. A molecular marker of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 505:50–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Straimer J, Gnadig NF, Witkowski B, Amaratunga C, Duru V, Ramadani AP, Dacheux M, Khim N, Zhang L, Lam S, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Benoit-Vical F, Fairhurst RM, Menard D, Fidock DA. 2015. Drug resistance. K13-propeller mutations confer artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum clinical isolates. Science 347:428–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1260867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashley EA, Dhorda M, Fairhurst RM, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, Anderson JM, Mao S, Sam B, Sopha C, Chuor CM, Nguon C, Sovannaroth S, Pukrittayakamee S, Jittamala P, Chotivanich K, Chutasmit K, Suchatsoonthorn C, Runcharoen R, Hien TT, Thuy-Nhien NT, Thanh NV, Phu NH, Htut Y, Han KT, Aye KH, Mokuolu OA, Olaosebikan RR, Folaranmi OO, Mayxay M, Khanthavong M, Hongvanthong B, Newton PN, Onyamboko MA, Fanello CI, Tshefu AK, Mishra N, Valecha N, Phyo AP, Nosten F, Yi P, Tripura R, Borrmann S, Bashraheil M, Peshu J, Faiz MA, Ghose A, Hossain MA, Samad R, Rahman MR, Hasan MM, Islam A, Miotto O, Amato R, MacInnis B, Stalker J, Kwiatkowski DP, Bozdech Z, Jeeyapant A, Cheah PY, Sakulthaew T, Chalk J, Intharabut B, Silamut K, Lee SJ, Vihokhern B, Kunasol C, Imwong M, Tarning J, Taylor WJ, Yeung S, Woodrow CJ, Flegg JA, Das D, Smith J, Venkatesan M, Plowe CV, Stepniewska K, Guerin PJ, Dondorp AM, Day NP, White NJ, Tracking Resistance to Artemisinin Collaboration (TRAC) . 2014. Spread of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med 371:411–423. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakihama N, Kaneko A, Hattori T, Tanabe K. 2001. Limited recombination events in merozoite surface protein-1 alleles of Plasmodium falciparum on islands. Gene 279:41–48. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(01)00748-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akhwale WS, Lum JK, Kaneko A, Eto H, Obonyo C, Bjorkman A, Kobayakawa T. 2004. Anemia and malaria at different altitudes in the western highlands of Kenya. Acta Trop 91:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi J, Phompida S, Toma T, Looareensuwan S, Toma H, Miyagi I. 2004. The effectiveness of impregnated bed net in malaria control in Laos. Acta Trop 89:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakihama N, Nakamura M, Palanca AA Jr, Argubano RA, Realon EP, Larracas AL, Espina RL, Tanabe K. 2007. Allelic diversity in the merozoite surface protein 1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum on Palawan Island, the Philippines. Parasitol Int 56:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanabe K, Sakihama N, Rooth I, Bjorkman A, Farnert A. 2007. High frequency of recombination-driven allelic diversity and temporal variation of Plasmodium falciparum msp1 in Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg 76:1037–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dysoley L, Kaneko A, Eto H, Mita T, Socheat D, Borkman A, Kobayakawa T. 2008. Changing patterns of forest malaria among the mobile adult male population in Chumkiri District, Cambodia. Acta Trop 106:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marma AS, Mita T, Eto H, Tsukahara T, Sarker S, Endo H. 2010. High prevalence of sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine resistance alleles in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from Bangladesh. Parasitol Int 59:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsumori Y, Ndounga M, Sunahara T, Hayashida N, Inoue M, Nakazawa S, Casimiro P, Isozumi R, Uemura H, Tanabe K, Kaneko O, Culleton R. 2011. Plasmodium falciparum: differential selection of drug resistance alleles in contiguous urban and peri-urban areas of Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. PLoS One 6:e23430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN. 1993. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol 61:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90077-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Librado P, Rozas J. 2009. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonald JH, Kreitman M. 1991. Adaptive protein evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature 351:652–654. doi: 10.1038/351652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nei M, Gojobori T. 1986. Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions. Mol Biol Evol 3:418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takala-Harrison S, Jacob CG, Arze C, Cummings MP, Silva JC, Dondorp AM, Fukuda MM, Hien TT, Mayxay M, Noedl H, Nosten F, Kyaw MP, Nhien NT, Imwong M, Bethell D, Se Y, Lon C, Tyner SD, Saunders DL, Ariey F, Mercereau-Puijalon O, Menard D, Newton PN, Khanthavong M, Hongvanthong B, Starzengruber P, Fuehrer HP, Swoboda P, Khan WA, Phyo AP, Nyunt MM, Nyunt MH, Brown TS, Adams M, Pepin CS, Bailey J, Tan JC, Ferdig MT, Clark TG, Miotto O, MacInnis B, Kwiatkowski DP, White NJ, Ringwald P, Plowe CV. 2015. Independent emergence of artemisinin resistance mutations among Plasmodium falciparum in Southeast Asia. J Infect Dis 211:670–679. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamau E, Campino S, Amenga-Etego L, Drury E, Ishengoma D, Johnson K, Mumba D, Kekre M, Yavo W, Mead D, Bouyou-Akotet M, Apinjoh T, Golassa L, Randrianarivelojosia M, Andagalu B, Maiga-Ascofare O, Amambua-Ngwa A, Tindana P, Ghansah A, MacInnis B, Kwiatkowski D, Djimde AA. 2015. K13-propeller polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum parasites from sub-Saharan Africa. J Infect Dis 211:1352–1355. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conrad MD, Bigira V, Kapisi J, Muhindo M, Kamya MR, Havlir DV, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. 2014. Polymorphisms in K13 and falcipain-2 associated with artemisinin resistance are not prevalent in Plasmodium falciparum isolated from Ugandan children. PLoS One 9:e105690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkes M, Conroy AL, Opoka RO, Namasopo S, Zhong K, Liles WC, John CC, Kain KC. 2015. Slow clearance of Plasmodium falciparum in severe pediatric malaria, Uganda, 2011-2013. Emerg Infect Dis 21:1237–1239. doi: 10.3201/eid2107.150213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isozumi R, Uemura H, Kimata I, Ichinose Y, Logedi J, Omar AH, Kaneko A. 2015. Novel mutations in K13 propeller gene of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Emerg Infect Dis 21:490–492. doi: 10.3201/eid2103.140898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taylor AR, Flegg JA, Nsobya SL, Yeka A, Kamya MR, Rosenthal PJ, Dorsey G, Sibley CH, Guerin PJ, Holmes CC. 2014. Estimation of malaria haplotype and genotype frequencies: a statistical approach to overcome the challenge associated with multiclonal infections. Malar J 13:102. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohon AN, Alam MS, Bayih AG, Folefoc A, Shahinas D, Haque R, Pillai DR. 2014. Mutations in Plasmodium falciparum K13 propeller gene from Bangladesh (2009-2013). Malar J 13:431. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conrad MD, LeClair N, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, Kakuru A, Bigira V, Muhindo M, Kamya MR, Tappero JW, Greenhouse B, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ. 2014. Comparative impacts over 5 years of artemisinin-based combination therapies on Plasmodium falciparum polymorphisms that modulate drug sensitivity in Ugandan children. J Infect Dis 210:344–353. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Z, Shrestha S, Li X, Miao J, Yuan L, Cabrera M, Grube C, Yang Z, Cui L. 2015. Prevalence of K13-propeller polymorphisms in Plasmodium falciparum from China-Myanmar border in 2007-2012. Malar J 14:168. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0672-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouattara A, Kone A, Adams M, Fofana B, Maiga AW, Hampton S, Coulibaly D, Thera MA, Diallo N, Dara A, Sagara I, Gil JP, Bjorkman A, Takala-Harrison S, Doumbo OK, Plowe CV, Djimde AA. 2015. Polymorphisms in the K13-propeller gene in artemisinin-susceptible Plasmodium falciparum parasites from Bougoula-Hameau and Bandiagara, Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg 92:1202–1206. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanabe K, Mita T, Jombart T, Eriksson A, Horibe S, Palacpac N, Ranford-Cartwright L, Sawai H, Sakihama N, Ohmae H, Nakamura M, Ferreira MU, Escalante AA, Prugnolle F, Bjorkman A, Farnert A, Kaneko A, Horii T, Manica A, Kishino H, Balloux F. 2010. Plasmodium falciparum accompanied the human expansion out of Africa. Curr Biol 20:1283–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mbengue A, Bhattacharjee S, Pandharkar T, Liu H, Estiu G, Stahelin RV, Rizk SS, Njimoh DL, Ryan Y, Chotivanich K, Nguon C, Ghorbal M, Lopez-Rubio JJ, Pfrender M, Emrich S, Mohandas N, Dondorp AM, Wiest O, Haldar K. 2015. A molecular mechanism of artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature 520:683–687. doi: 10.1038/nature14412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hott A, Tucker MS, Casandra D, Sparks K, Kyle DE. 2015. Fitness of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:2787–2796. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miotto O, Amato R, Ashley EA, MacInnis B, Almagro-Garcia J, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Mead D, Oyola SO, Dhorda M, Imwong M, Woodrow C, Manske M, Stalker J, Drury E, Campino S, Amenga-Etego L, Thanh TN, Tran HT, Ringwald P, Bethell D, Nosten F, Phyo AP, Pukrittayakamee S, Chotivanich K, Chuor CM, Nguon C, Suon S, Sreng S, Newton PN, Mayxay M, Khanthavong M, Hongvanthong B, Htut Y, Han KT, Kyaw MP, Faiz MA, Fanello CI, Onyamboko M, Mokuolu OA, Jacob CG, Takala-Harrison S, Plowe CV, Day NP, Dondorp AM, Spencer CC, McVean G, Fairhurst RM, White NJ, Kwiatkowski DP. 2015. Genetic architecture of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Genet 47:226–234. doi: 10.1038/ng.3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miotto O, Almagro-Garcia J, Manske M, Macinnis B, Campino S, Rockett KA, Amaratunga C, Lim P, Suon S, Sreng S, Anderson JM, Duong S, Nguon C, Chuor CM, Saunders D, Se Y, Lon C, Fukuda MM, Amenga-Etego L, Hodgson AV, Asoala V, Imwong M, Takala-Harrison S, Nosten F, Su XZ, Ringwald P, Ariey F, Dolecek C, Hien TT, Boni MF, Thai CQ, Amambua-Ngwa A, Conway DJ, Djimde AA, Doumbo OK, Zongo I, Ouedraogo JB, Alcock D, Drury E, Auburn S, Koch O, Sanders M, Hubbart C, Maslen G, Ruano-Rubio V, Jyothi D, Miles A, O'Brien J, Gamble C, Oyola SO, Rayner JC, Newbold CI, Berriman M, Spencer CC, McVean G, Day NP, White NJ, Bethell D, Dondorp AM, Plowe CV, Fairhurst RM, Kwiatkowski DP. 2013. Multiple populations of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Cambodia. Nat Genet 45:648–655. doi: 10.1038/ng.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talundzic E, Okoth SA, Congpuong K, Plucinski MM, Morton L, Goldman IF, Kachur PS, Wongsrichanalai C, Satimai W, Barnwell JW, Udhayakumar V. 2015. Selection and spread of artemisinin-resistant alleles in Thailand prior to the global artemisinin resistance containment campaign. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004789. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mita T, Tanabe K, Kita K. 2009. Spread and evolution of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance. Parasitol Int 58:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tun KM, Imwong M, Lwin KM, Win AA, Hlaing TM, Hlaing T, Lin K, Kyaw MP, Plewes K, Faiz MA, Dhorda M, Cheah PY, Pukrittayakamee S, Ashley EA, Anderson TJ, Nair S, McDew-White M, Flegg JA, Grist EP, Guerin P, Maude RJ, Smithuis F, Dondorp AM, Day NP, Nosten F, White NJ, Woodrow CJ. 2015. Spread of artemisinin-resistant Plasmodium falciparum in Myanmar: a cross-sectional survey of the K13 molecular marker. Lancet Infect Dis 15:415–421. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70032-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cravo P, Culleton R, Hunt P, Walliker D, Mackinnon MJ. 2001. Antimalarial drugs clear resistant parasites from partially immune hosts. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:2897–2901. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.10.2897-2901.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.