Abstract

Melatonin, via its MT1 receptor, but not the MT2 receptor, can modulate the transcriptional activity of various nuclear receptors (ERα and RARα, but not ERβ) in MCF-7, T47D and ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cell lines. The anti-proliferative and nuclear receptor modulatory actions of melatonin are mediated via the MT1 G protein-coupled receptor expressed in human breast cancer cells. However, the specific G proteins and associated pathways involved in nuclear receptor transcriptional regulation by melatonin are not yet clear. Upon activation, the MT1 receptor specifically couples to the Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq and Gαll proteins, and via activation of Gαi2 proteins, melatonin suppresses forskolin-induced cyclic AMP (cAMP) production, while melatonin activation of Gαq, is able to inhibit phospholipid hydrolysis and ATP’s induction of inositol triphosphate (IP3) production in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Employing dominant-negative (DN) and dominant-positive (DP) forms of these G proteins we demonstrate that Gαi2 proteins mediate the suppression of estrogen-induced ERα transcriptional activity by melatonin, while the Gq protein mediates the enhancement of retinoid-induced RARα transcriptional activity by melatonin. However, the growth-inhibitory actions of melatonin are mediated via both Gαi2 and Gαq proteins.

Keywords: melatonin, G proteins, estrogen receptor alpha, breast cancer

Introduction

It has been shown that melatonin at physiologic concentrations inhibits the growth of ERα-positive human breast cancer cell lines, including MCF-7 cells [1]. The majority of the growth-inhibitory actions of melatonin on breast cancer cells appear to be mediated through the MT1 G protein-coupled membrane melatonin receptor [2]. Activation of MT1 melatonin receptors by melatonin appears to modulate a variety of G-proteins, which subsequently impact a variety of the signal transduction pathways. The heterotrimeric G-proteins activated by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) generally release two groups of activating subunits: a GTP-bound form of the α subunit as well as a βγ dimer [3], both can act individually or simultaneously as the signal transducers [4]. Considering the well-known function of G-protein α subunits in GPCR signaling, this study focuses on the role of the Gα subunit on melatonin receptor-mediated signaling pathways. Each activated GTP-bound Gα subunit belongs to a different G-protein subfamily termed Gs, Gi, Gq and G12/13, which in turn act on individual effectors, including adenylate cyclase (AC), phosphodiesterase (PDE), phospholipase C (PLC) or ion channels to further affect the levels of associated second messengers such as cAMP, cGMP, inositol triphosphate (IP3), and calcium [5]. Previous reports have demonstrated that melatonin, through activation of MT1 G protein-coupled melatonin receptor, regulates a number of these different downstream second messengers in a variety of tissues [6–14].

In MCF-7 breast cancer cells, we have previously reported that melatonin inhibits estrogen-, forskolin (Fsk)- or pituitary adenylate cyclase activating protein (PACAP) -induced increase of cAMP [7]. This inhibitory action appears to be mediated through the membrane Gαi protein-coupled MT1 receptor, since in most cases the inhibitory effect of melatonin on cAMP levels is pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive [8]. Melatonin can blunt and/or block the stimulation of cAMP by forskolin or PACAP without prior stimulation of cAMP, but does not repress the basal level of cAMP [9,10]. Finally, our laboratory has previously reported that melatonin treatment enhances intracellular calcium levels [Ca2+]i induced by ATP, implying the possible involvement of melatonin in phosphoinositol breakdown in MCF-7 breast cancer cells [15]. Also, MLT regulates ERα membrane signaling.

We [16] and others [17] have previously reported that melatonin can regulate the transcriptional activity of a number of steroid receptors, such as estrogen receptor alpha (ERα), retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and the retinoic acid related orphan receptor alpha (RORα) [16–20]. Kiefer et al. [7] demonstrated that the effects of melatonin on ERα transcriptional activity involve PTX-sensitive G-protein mechanisms. Currently, we have not delineated the specific G-proteins or the specific downstream signaling pathways through which melatonin differentially regulates the transcriptional activity of these steroid/thyroid hormone receptors. In the following set of experiments, we begin to define which G-proteins couple to the MT1 receptor and the specific second messengers (i.e. cAMP, cGMP, IP3, etc.) that transduce the effect of melatonin on steroid/thyroid hormone receptors to differentially modulate their transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells.

Materials and Methods

Materials

All chemicals and tissue culture reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). RPMI 1640 medium was purchased from Cellgro (Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gibco-BRL (Grand Island, NY). The dominant-positive (DP) G-protein plasmids (DP-Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq and G11) and wild-type G-protein EE-tag expression vectors (DP Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq, Gα11, G0 and Gz) were purchased from Guthrie cDNA resource center (Sayre, PA). The dominant-negative (DN) G-protein plasmids (DN-Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq, Gα11 and control vector GαiR) were purchased from Cue Biotech (Chicago, IL). Anti-G-protein polyclonal rabbit antibodies (Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gq G0 Gαz, and G12) and an anti-Gα16 goat polyclonal antibodies or anti Gαi-mouse monoclonal antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The ERα antibodies H222 and C134 were purchased from Abbott Laboratories, Abbott, IL.

Cell culture, expression plasmids and HRE reporter constructs

The MCF-7, T47D, and ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells, obtained from the laboratory of the late William L. McGuire (San Antonio, TX) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 50 mM nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM basal medium eagle (BME), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 µg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37° C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

The ERE-luciferase construct used for our ERα transcriptional activity studies was kindly provided by Dr. Carolyn Smith (Houston, TX), and contains three vitellogenin ERE’s upstream to the SV40 promoter in the pGL2P luciferase reporter plasmid. The RARE-luciferase construct for the RARα transcriptional activity studies was kindly provided by Dr. Elwood Linney (Durham, North Carolina) and contains three RAREs from the RARβ gene upstream of the thymidine kinase promoter. The pCMVβ galactosidase plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Jean Lockyer (New Orleans, LA). The dominant-positive (DP) G-protein plasmids (DP-Gαi2, DP-Gαi3, DP-Gαq, and DP-Gα11) and wild type G-protein EE-tag expression vectors (Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq, Gα11, Gαo, and Gαz), were purchased from Guthrie cDNA resource center (Sayre, PA). The pcDNA3.1 control vector was purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). The dominant-negative (DN) G-protein plasmids (DN-Gαi1/2, DN-Gαi3, DN-Gαq, and DN-Gα11) and control vector (GαiR) were purchased from Cue Biotech (Chicago, IL). The FuGENE transfection reagent was purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN).

Transient transfection and luciferase assay

MCF-7, T47D and ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, then grown in phenol red-free medium supplemented with 5% CS-FBS for three days. The cells were then plated in 6-well plates at a density of 0.5 × 105 cells/well in the same media. On the following day, the cells were transiently transfected for 6–8 hours in serum-free medium with 400 ng/well luciferase reporter construct (ERE-luciferase construct or RARE-luciferase construct), 100 ng/well pCMVβ plasmid using the FuGENE transfection reagent. The ERE-luciferase reporter construct contains a region of the vitellogenin A2 promoter upstream of the adenovirus E1b-TATA-promoter in the pGL2 basic luciferase reporter plasmid and was provided by Dr. Carolyn Smith (Houston, TX). Eight hours following transfection the cells were re-fed with 5% CS-FBS supplemented medium and administered the indicated treatment for an additional 18 h prior to preparation of cell extracts. For studies examining the inhibitory effect of melatonin on 17-β estradiol (E2) induction of ERα transcriptional activity, cells (MCF-7, T47D, or ZR-75-1) were treated with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), melatonin (10 nM), E2 (1 nM) or pre-treated with melatonin (10 nM) for 30 min followed by E2.

For studies examining effects of melatonin on all-trans retinoic acid (atRA) induction of RARα transcriptional activity, breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7, T47D, and ZR-75-1) were treated with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), melatonin (10 nM), atRA (1 nM), or melatonin and atRA simultaneously. The RARE-luciferase reporter construct contains three retinoic acid receptor response elements (RAREs) from the retinoic acid receptor-α (RARα) gene upstream of the thymidine kinase promoter in the pW1 luciferase reporter plasmid and was provided by Dr. Elwood Linney (Durham, North Carolina). Eighteen hours following treatment, the cells were harvested in lysis buffer (24 mM Tris, pH7.8, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100) for luciferase assays using the luciferase assay system (Promega, Madison, WI). Cellular protein concentration was measured using the BioRad protein assay kit (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), and β-galactosidase activity was measured by the o-nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) assay. Luciferase assays were performed using a Model 2010 Luminometer (MGM instrument, Inc., Hamden, CT). For each sample, the luciferase activity was normalized to both the protein concentration and the β-galactosidase activity.

In studies to determine which G proteins mediate melatonin’s regulation of ERα and RARα transcriptional activity, MCF-7 cells were used as the model system and transfected with dominant negative (DN)- and dominant positive (DP)-G-proteins. For these studies MCF-7 cells transfected with DN-G-proteins were treated with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), melatonin (10 nM), E2 (1 nM) or pre-treated with melatonin (10 nM) for 30 min followed by E2 or treated with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), melatonin (10 nM), atRA (1 nM), or melatonin and atRA simultaneously, while MCF-7 cells transfected with DP-G-proteins were treated with either vehicle (0.001% ethanol) E2 or atRA. Eighteen hours following treatment, the cells were harvested in lysis buffer and cellular proteins used in luciferase assays as described above. Parallel culture dishes were also set-up for protein extraction and analysis of DP or DN-G protein expression of transfected cells. Protein extraction and Western blot analyses for expressed G proteins were conducted as described above.

Melatonin regulation of ERα and ERβ- transcriptional activity

For these studies ERα/β-negative HEK293 embryonic kidney cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, then grown in phenol red-free medium supplemented with 5% CS-FBS for three days. The cells were then plated in 6-well plates at a density of 0.5 × 105 cells/well in the same media. On the following day, the cells were transiently transfected for 6–8 hours in serum-free medium with 400 ng/well of ERα or ERβ and MT1, as well as 400 ng/well of luciferase reporter construct (ERE-luciferase construct or RARE-luciferase construct), and 100 ng/well pCMVβ plasmid using the FuGENE transfection reagent. Eight hours following transfection the cells were re-fed with 5% CS-FBS supplemented medium and treated with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), melatonin (10 nM), E2 (1 nM) or pre-treated with melatonin (10 nM) for 30 min followed by E2 for an additional 18 h prior to preparation of cell extracts. Luciferase assays were done as described above.

ERα phosphorylation assay

MCF-7 cells were cultured in estrogen- and phosphate-free medium for 16 h prior to treatment. Cells were treated with either melatonin (10 nM), E2 (1 nM) or transfected with a DP-Gαi2 expression construct in the presence of [32P]-orthophosphate (50 µCi/ml) for 4 h. Cells were then rinsed in cold PBS and harvested in 40 mM Tris-Hcl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM EDTA. The cells were lysed for 1 h in 500 ml of 50 mM Tris-Hcl, pH 8.0, 1% NP-40, 2% Sarkosyl, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 100 µM sodium vanadate, 10 mM sodium molybdate, 20 mM sodium fluoride, leupeptin, aprotinin and PMSF. The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4° C and the supernatant used for immunprecipitation. Phosporylated ERα was measured by immunoprecipitating total ERα with the H222 ERα (2.5 µg) [Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL] and the resulting immunoprecipitate was run on a 12% polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted overnight onto Hybond-C membrane. The phosphorylation state of the ERα was determined by exposure of the membrane to the P5747 anti-phosphoserine antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) at a 1:300 dilution. Total ERα levels were determined using the C-134 Abbott anti-ERα antibody.

Whole cell lysate preparation and Western blot analysis

Whole cell lysates were extracted from MCF-7 breast cancer cells maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS. After washing with ice-cooled PBS, the cells were incubated in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% Nonidet P40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and protease inhibitors), homogenized by 10 strokes of a dounce homogenizer, and incubated for one hour at 4° C. To remove the insoluble components, the homogenized suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4° C. Whole cell lysates (70 µg per sample) were denatured in sample loading buffer (70 mM Tris pH6.8, 2% SDS, 4 M urea, 40 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol, 0.05% bromophenol blue) for 5 min at 80° C, separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and then transferred onto a Hybond membrane (Hybond-ECL, Amersham pharmacia, NJ). The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS-T20 buffer (10 mM Tris, pH8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.2% Tween 20) for one hour at room temperature, and then incubated with a variety of anti-G-protein polyclonal antibodies (Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq, Gα11, Gαo, Gαz, Gα12, and Gα16) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) (1:1000) with TBS-T20 containing 5% non-fat milk for one hour at room temperature. After several washes with TBS-T20 buffer, the membranes were incubated with horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-conjugated anti-goat IgG, or HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) at a dilution of 1:2000 with TBS-T20 containing 5% non-fat milk for 45 min. After several washes in TBS-T20 buffer, the immunoreactive proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection reagents (Amersham Pharmacia, NJ) and exposure of membrane to Kodak BIOMAX film.

Whole cell extracts and co-immunoprecipitation assays

The MCF-7 cells stably transfected with and over-expressing the MT1 receptor (MT1-MCF-7) were maintained in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, and treated with 10 nM melatonin or vehicle (0.001% ethanol) for 30 min, then washed twice with ice-cold PBS. For melatonin-treated samples, all subsequent steps were performed in the presence of 10 nM melatonin. The cells were incubated with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 150 mM sodium chloride, 1% Nonidet P40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and protease inhibitors), scraped with a rubber policeman and homogenized by 10 strokes of the dounce homogenizer. The homogenized cellular lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4° C and the supernatant was pre-adsorbed with 50 µl protein A-agarose beads (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) for at least 3 h at 4° C. The supernatant was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 20 s at 4° C. Whole cell lysates were incubated with the MT1 536 anti-body (kindly provided by Dr. Ralf Jockers, Paris, France) at a dilution 1:50 for one hour at 4° C. Fifty microliters of protein A-agarose beads were added to the cell lysate, and the suspension was rotated overnight at 4° C. After centrifugation for at 12,000 × g at 4° C for 20 sec, the beads were washed twice in lysis buffer at 4° C for 20 min, followed by washes in a high salt washing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mM sodium chloride, 0.1% Nonidet P40, 0.05% sodium deoxycholate and protease inhibitors) for 20 min at 4° C, then one wash in low salt washing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 0.1% Nonidet P40, 0.05% sodium deoxycholate and protease inhibitors) for 20 min at 4° C. Finally, protein A-agarose beads were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4° C for 20 s, and denatured in 25 µl sample loading buffer as described above. The proteins were electrophoretically separated on a 15% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto Hybond membranes. The co-immunoprecipitated G-proteins were detected by Western blot analysis as described above using a variety of anti-G-protein antibodies at a 1:500 dilution.

Cyclic AMP radioimmunoassay

MCF-7 cells grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells per well. On the day following plating, the cells were transiently transfected with either DN- or DP-G-proteins described as above. Twenty-four hours following transfection, the cells were rinsed and re-fed with serum-free RPMI 1640 for an additional 24 h. The cells transfected with DN-G-proteins were pre-treated with 0.1 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX) for 10 min, and then treated for 10 min with vehicle (0.1% DMSO), melatonin (10 nM), forskolin (1 µM), or melatonin and forskolin, simultaneously. Cells transfected with DP-G-proteins were pretreated with 0.1 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX) for 10 min and then with either vehicle (0.1% DMSO) or forskolin (1 µM) for 10 min. The cells were lysed in ice-cold 100% ethanol and cell lysates were centrifuged at 2000 × g for 15 min at 4° C. The supernatants were concentrated in a Speed-Vac (Savant, Farmingdale, NY) and the dried extracts were re-suspended in 200 µl of cAMP assay buffer (0.05 M acetate buffer, pH5.8) and 1:1000 dilution of extract was analyzed for cAMP levels using the cAMP- [125I] assay system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cyclic GMP radioimmunoassay

MCF-7 cells grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells per well. On the following day, the cells were rinsed with RPMI 1640 medium and pre-treated with 0.1 mM IBMX for 10 min, followed by a 10 min treatment with either vehicle (0.001% DMSO), 5-cyclopropyl-2[1(2-fluoro-benzyl)-1H-pyraxolo[3,4-b]pyrimidine-4-ylamine (BAY 41-2272) at a concentration of 1 µM (for 10 min), melatonin (10 nM) or pre-treated with different doses of melatonin (1 nM to 10 µM) followed by BAY 41-2272 for 10 min. After 10 min of BAY 41-2272 treatment the cells were lysed in ice-cold 100% ethanol and lysates were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min at 4° C. The supernatant was concentrated in a Speed Vac and dried extracts re-suspended in 200 µl of cGMP assay buffer (0.05 M acetate buffer, pH5.8). A 1:1000 dilution of cell extract was analyzed for cGMP levels by using the cGMP-[125I] assay system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) as per the manufacturer’s instruction.

Inositol-1, 4, 5-trisphosphate (IP3) assay

MCF-7 cells grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 0.5 × 106 cells per well. On the following day, the cells were transiently transfected with either DN or DP-G-proteins described as above. Twenty-four hours following transfection, the cells were rinsed and re-fed with serum-free RPMI 1640 for an additional 24 h. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were rinsed with RPMI 1640 medium and pre-incubated for 20 min in 10 mM LiCl. The cells were pre-treated with either vehicle (0.001% ethanol) or melatonin (10 nM) for 30 min followed by 100 mM ATP. After 20 min of treatment, the cells were lysed in 3% ice-cold perchloric acid for 20 min. The lysates were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min at 4° C. The supernatants were neutralized to pH 7.5 with ice-cold 10 M KOH, and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 15 min at 4° C. The resulting aqueous phase was analyzed using the Inositol-1, 4,5-triphosphate (IP3) [3H] assay system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont Buckinghamshire, England) as per the manufacturer’s instruction.

Growth study

MCF-7 cells were plated at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS in 6-well plates. Twenty-four hours after plating cells were transiently transfected with 50 ng/well of the pcDNA3.1 control vector, DN-G or DP-G-protein plasmids using the FuGENE transfection reagent in serum-free medium. After an 8 h transfection, the cells transfected with DN-G-proteins were re-fed with fresh serum-containing medium and treated with either vehicle (0.001% ethanol) or melatonin (1 nM), while the cells transfected with DP-G-proteins were re-fed with fresh serum-containing medium and treated with vehicle (0.001% ethanol) alone. After 7 days, the cells were harvested with PBS-EDTA, mixed with 2% trypan blue to determine cell viability, and viable cells were counted on a hemacytometer.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical significance using a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests.

Results

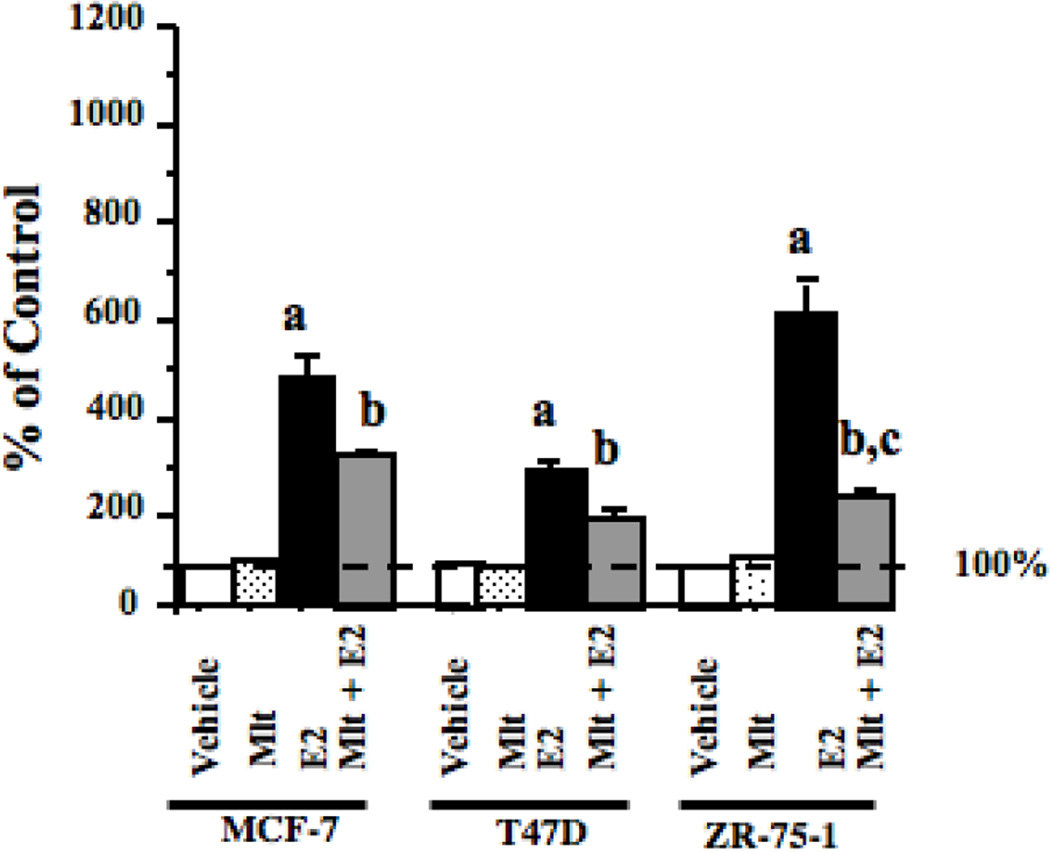

We have previously demonstrated that melatonin can suppress estrogen-induced transcriptional activation of the ERα in MCF-7 breast cancer cells [7,16], however, we have not confirmed that this is seen in other ERα-positive human breast cancer cell lines. Therefore, we conducted ERE-luciferase reporter analysis to examine the ability of melatonin to repress E2-induced ERα transactivation in T47D and ZR-75-1 human breast tumor cell lines. As shown in Fig. 1, pre-treatment of MCF-7 cells with 10 nM melatonin significantly blunted E2-induced ERα transcriptional activation by 42% in MCF-7 cells, 30% in T47D cells and 64% in ZR-75-1 breast cancer cells. The suppression of ERα transcriptional activity by melatonin was significantly enhanced in ZR-75-1 cells as compared to T47D cells.

Fig. 1.

Effects of melatonin on ERα transcriptional activity in MCF-7, T47D and ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells. MCF-7, T47D and ZR-75-1 breast cancer cells grown in phenol red-free medium supplemented with 5% CS-FBS and were used to examine ERα transcriptional activity using an ERE-luciferase reporter construct as described in Materials and Methods with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), 10 nM melatonin, 1 nM E2, or pretreated with melatonin for 30 min followed by E2. Luciferase activity was recorded as mean relative light units (RLUs). For comparison purposes between tumor cell lines diluent treated values were set at 100% and activity in response to other treatments was recorded as percent of control activity. n=3 independent experiments; a, P < 0.05 vs. control; b, P < 0.05 vs. E2 alone.

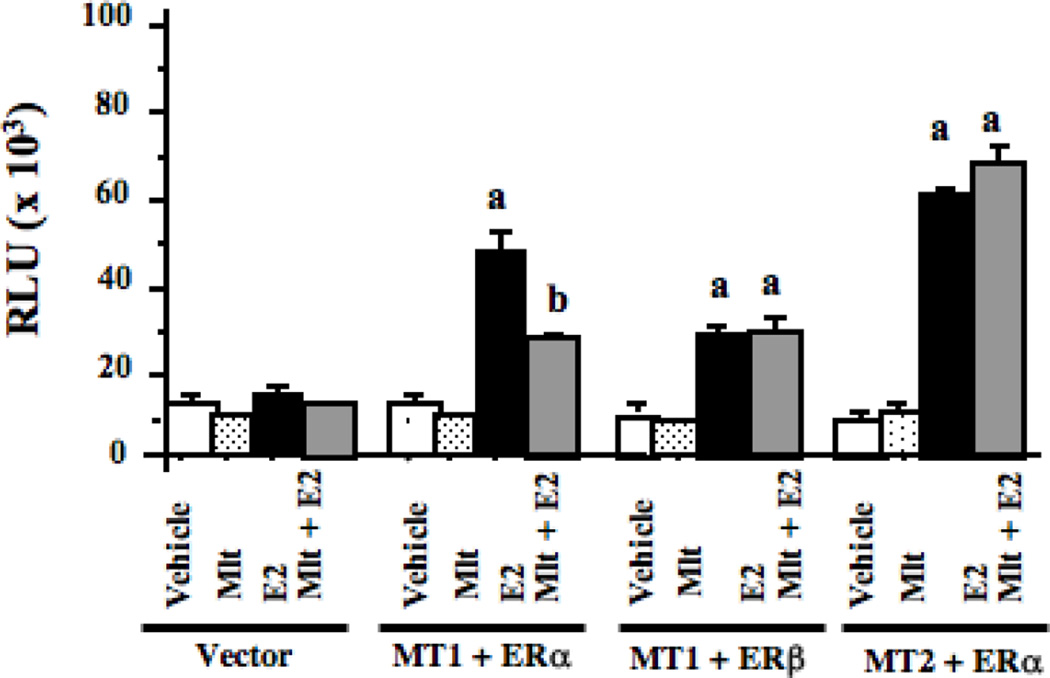

To determine if melatonin also represses E2-induced ERβ transcriptional activity, we conducted ERE-luciferase reporter assays in HEK293 cells, which do not express endogenous ERα, ERβ, MT1, or MT2 receptors. For these studies HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with expression constructs for ERα, ERβ and MT1 or MT2 as well as an ERE-luciferase reporter construct. As shown in Fig. 2, treatment of transfected HEK293 cells with E2 (1 nM) did not alter ERE-luciferase activity in HEK293 cells transfected with only the ERE-luciferase reporter construct or the pcDNA3.1 vector. However, in cells transfected with the ERα construct, treatment with 1 nM E2 resulted in a 4.2-times increase in luciferase activity and pre-treatment of cells with 10 nM melatonin significantly blunted ERα transcriptional activity by 41%. However, E2 induced a 2.7-times increase in ERβ transcriptional activity and this activity was not blunted by melatonin. When HEK293 cells were transfected with ERα and the MT2 melatonin receptor, E2 again induced a 4.6-times increase in ERα activity, but ERα transcriptional activity was not blocked by melatonin when the MT2 receptor was expressed.

Fig. 2.

Effects of melatonin via MT1 and MT2 receptors on ERα and ERβ transcriptional activity in HEK293 embryonic kidney cells. HEK293 embryonic kidney cells were grown in phenol red-free medium supplemented with 5% CS-FBS. After 3 days in media supplemented with 5% CS-FBS cells were transiently transfected with ERα or ERβ, MT1 or MT2 cDNA expression vectors, an ERE-luciferase reporter construct and treated for 18 h with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), 10 nM melatonin, 1 nM E2, or pretreated with melatonin for 30 min followed by E2 as described in Materials and Methods. Luciferase activity was recorded as mean relative light units (RLUs). n=3 independent experiments; a, P < 0.05 vs. control; b, P < 0.05 vs. E2 alone.

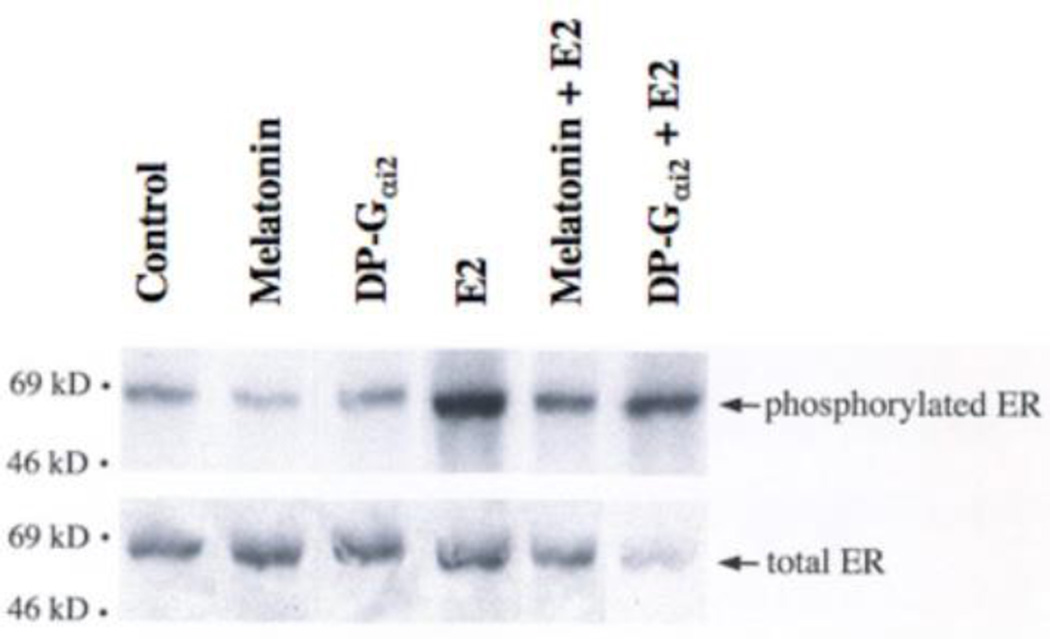

The ERα demonstrates a basal level of phosphorylation in the absence of ligand, which increases approximately 3.0-times upon stimulation with E2. Analysis of the effect of melatonin and DP-Gαi2 protein expression on E2-induced ERα phosphoryation demonstrates that melatonin induces a marked decrease (56%) in basal ERα phosphorylation (Fig. 3). In addition, expression of a DP-Gαi2 protein also resulted in a marked diminution (38%) in E2-stimulated ERα phosphorylation.

Fig. 3.

Modulation of ERα phosphorylation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells by E2, melatonin and a DP-Gαi2 protein. Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated ERα in response to E2 (1 nM), melatonin (10 nM) and expression of a DP-Gαi2 (50 mg/well) cDNA. Phosphorylated ERα is on the top band and total ERα is the bottom band.

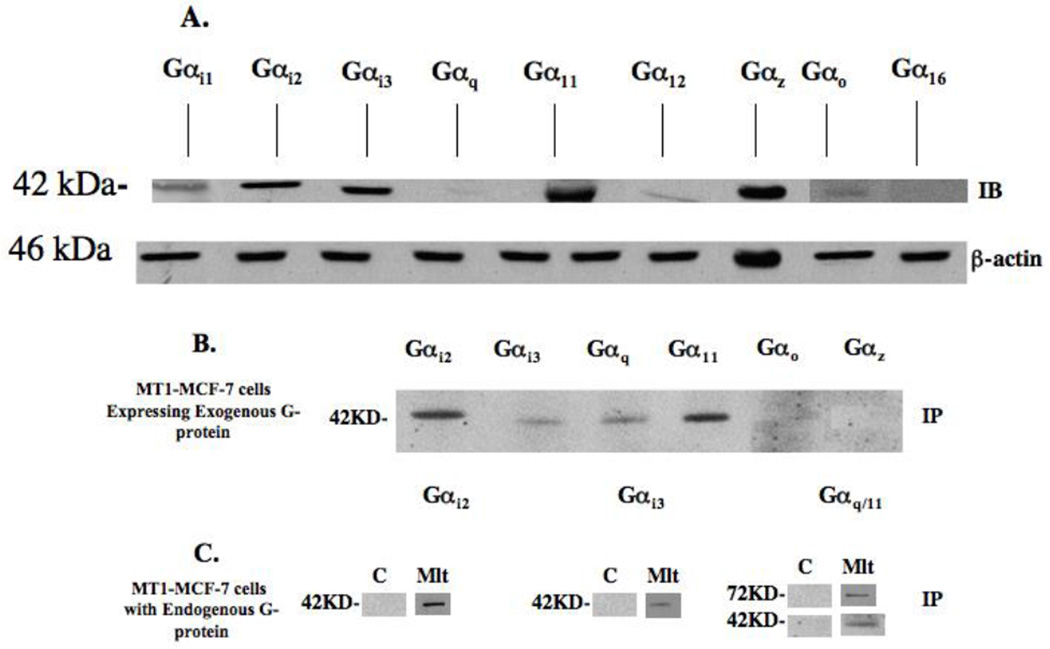

Our laboratory has previously demonstrated that the growth-inhibitory effects of melatonin on human breast tumor cells are largely mediated through the MT1 G-protein-coupled receptor [2]. To further clarify the MT1 receptor coupled signaling pathway(s) in breast cancer, we set out to identify which G-proteins coupled to the MT1 receptor in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. First, we identified the endogenous G-proteins expressed in MCF-7 cells using immuno (Western)-blot analyses (Fig. 4A). Using whole cell lysates from MCF-7 cells and a panel of anti-G-protein + subunit antibodies, numerous endogenous G-proteins were detected, including Gαi1, Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαz, Gαo, Gαq, Gα11, and Gα12. However, not all G-proteins appear to be expressed in MCF-7 cells, for example, the Gα16 protein, previously reported to couple to the MT1 receptor in MT1-transfected HEK293 cells [21], was not expressed in MCF-7 cells.

Fig. 4.

Expression of G proteins and MT1 receptor in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. (a) G-proteins expressed in MCF-7 cells. Seventy micrograms of total cellular protein from MCF-7 cells were loaded onto each lane. Specific G-proteins were detected using anti-G protein polyclonal rabbit antibodies (Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq, Gα11, Gαo, Gαz, and Gα12), anti-Gα16 goat polyclonal antibodies, or anti-Gαi1 mouse monoclonal antibody at a 1:1000 dilution. (b) MT1-MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type G-protein (Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq, Gα11, Gαo, Gαz, Gα12, Gα16 and Gαi1) expression vectors for 24 h, followed by treatment with 10 nM melatonin. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with the anti-MT1 536 and protein A-agarose beads. (c) The extracts from the MT1-MCF-7 cells treated with either control vehicle (C) [0.001% alcohol] or 1 nM melatonin (Mlt) for 30 min. were incubated with anti-MT1 536 antibody for immunoprecipition. G-proteins coupled to the MT1 receptor were detected by immunoblot blot analysis, using specific anti-G-protein antibodies as described in Materials and Methods.

Second, we examined which G-protein(s) couple to the MT1 receptor in MCF-7 cells. Considering the low level of expression of the endogenous MT1 receptor in MCF-7 cells, immunoprecipitation experiments were conducted in MT1-MCF-7 cells stably transfected with and over-expressing the human MT1 melatonin receptor and wild type of G-proteins. As shown in Fig. 4B, melatonin treatment stimulated the Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq, and Gα11 proteins, but not the Gαo and Gαz to couple to and co-immunoprecipitate with the MT1 receptor.

To demonstrate that the endogenously expressed G-proteins couple to the activated MT1 receptor, we repeated our co-immunoprecipitation studies in MT1-MCF-7 cells and treated the cells with either vehicle or 1 nM melatonin for 30 min. Fig. 4C shows that endogenously expressed Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq and Gα11 proteins indeed couple to and co-immunoprecipitate with the melatonin-activated MT1 receptor in MCF-7 cells.

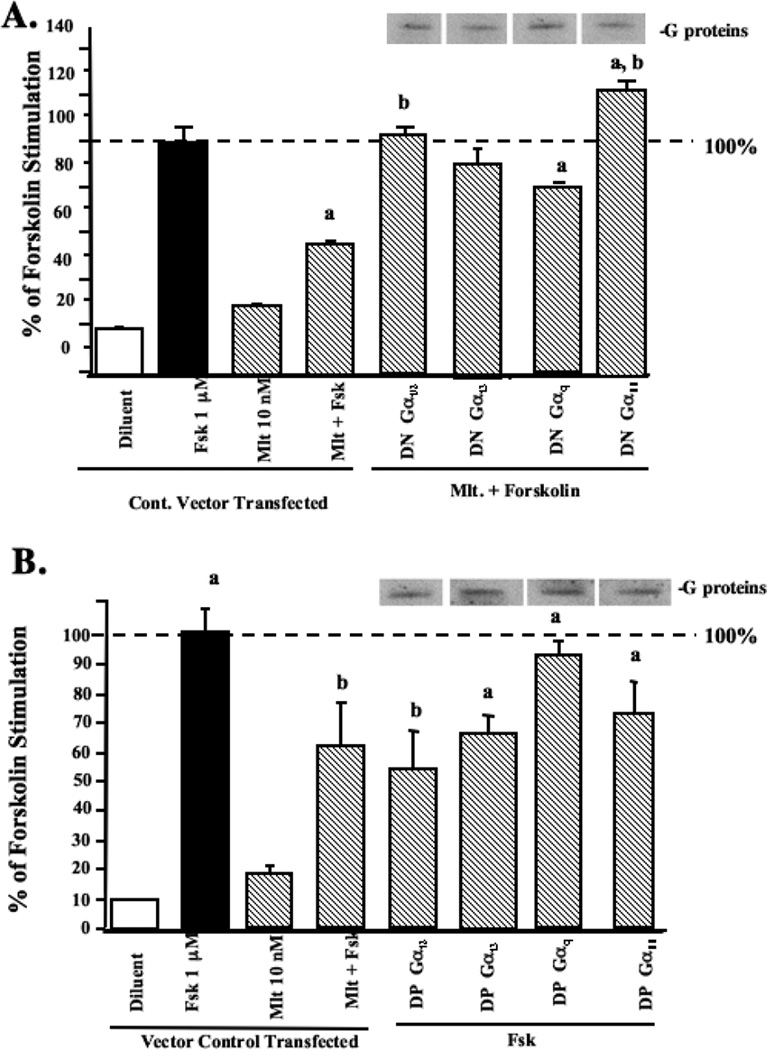

Melatonin has previously been shown in tissues other than the breast, to negatively regulate intracellular cAMP levels [6,8], and down-stream components of the cAMP-signaling pathway including PKA activity and CREB phosphorylation [22]. As well, Gαi proteins are also known to negatively regulate cAMP signaling, including repressing Fsk-induced cAMP accumulation through PTX-sensitive mechanism [8]. Therefore, we employed a cAMP radioimmunoassay assay to determine if MT1 receptor-coupled Gi or Gq proteins are involved in mediating melatonin inhibition of cAMP levels induced by Fsk in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. As shown in Fig. 5, stimulation of MCF-7 cells with Fsk (1 µM) induced an approximately eight-fold increase in cAMP levels. Treatment of MCF-7 cells with melatonin alone had no significant effect on basal levels of cAMP, however, pre-treatment of MCF-7 cells for 10 min with melatonin (10 nM) significantly blunted (by 50%) the increase in intracellular cAMP concentrations induced by Fsk. Furthermore, melatonin inhibition of forskolin-induced cAMP accumulation was blocked by the expression of DN-Gαi1/2, DN-Gαi3, and DN-Gα11 proteins, but not the DN-Gαq protein (Fig. 5A). Conversely, DP-Gαi2, DP-Gαi3, and DP-Gα11 proteins (Fig. 5B), but not the DN-Gαq protein significantly inhibited Fsk-induced cAMP accumulation.

Fig. 5.

Modulation of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation by melatonin in MCF-7 cells with transient expression of G-protein. (a) Modulation of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation by melatonin in the cells expressing DN-G-proteins. Cells were transfected transiently with DN-G-protein expression constructs then treated as described in Materials and Methods. Cell extracts (1:1000 dilution) were analysized for cAMP levels using the cAMP-[125I] assay system as described in Materials and Methods. (b) Modulation of forskolin-stimulated cAMP accumulation in the cells expressing DP-G-proteins. Cell extracts (1:1000 dilution) were analyzed for cAMP levels as described above. Expression of DN-G-proteins and DP-G-proteins following transfection was evaluated by immunoblot analysis of duplicate cell lysates and expression is shown above the bar graph. Results are expressed as a percentage of Fsk stimulation. (n =3 experiments in triplicate for each group). a, P < 0.05 vs. control, b, P < 0.05 vs. Fsk).

It has been reported that melatonin elevates the levels of cGMP in mammary tissue [23], but the effect of melatonin on the level of cGMP has not been examined in breast cancer cells. To test whether MT1 receptor activation modulates the cGMP signaling pathway, MCF-7 cells expressing endogenous MT1 receptor were incubated in the presence of the non-specific inhibitor of phosphodiesterases IBMX and then treated with either DMSO, 5-Cyclopropyl-2[1(2-fluoro-benzyl)]-1H-pyraxolo[3,4-b]pyrimdin-4-ylamine (BAY 41-2272), a known inducer of cGMP, melatonin or pre-treated with melatonin for 5 min followed by BAY 41-2272 [24]. BAY 41-2272 induced a significant 2.1-times increase in intracellular cGMP levels, while melatonin treatment alone (10 nM) did not affect of the cGMP levels in MCF-7 cells. Furthermore, pre-treatment of cells with various doses of melatonin (1 nM to 10 µM) did not affect the BAY 41-2272-induced elevation of intracellular cGMP levels, (data not shown).

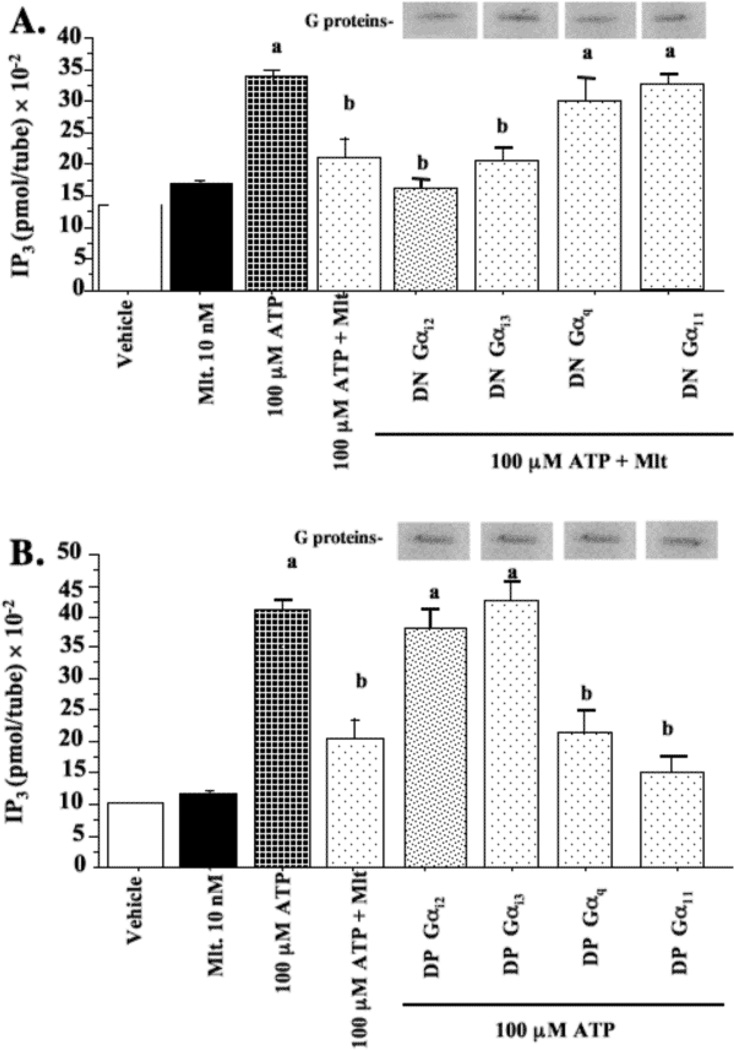

Previous data from our laboratory has shown that melatonin can potentiate ATP-induced stimulation and accumulation of intracellular calcium [Ca2+]i in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, but melatonin alone does not alter the basal levels of [Ca2+]i [15]. This result suggests the involvement of the Gαq/11-coupled signaling pathways in the regulation of [Ca2+]i. To determine if IP3, or Gαq/11 activated PLC pathway is modulated by melatonin, MCF-7 cells were pre-treated with LiCl for 20 min to block the degradation of IP3 as measured with the D-myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate assay. To evaluate the effect of melatonin on IP3 levels in MCF-7 cells, we examined the effect of melatonin on either basal levels of IP3 or ATP-induced IP3 levels. As shown in Fig. 6, stimulation of MCF-7 cells with 100 mM ATP induced approximately a 3.0-times increase in IP3 levels. Melatonin (10 nM) had no significant effect on basal IP3 levels, however, pre-treatment of MCF-7 cells for 5 min with melatonin (10 nM) significantly blunted (by 52%) the increase in IP3 levels induced by ATP. Furthermore, the expression of DN-Gαq and DN-Gα11 proteins, but not the DN-Gαi2 and DN-Gαi3 proteins blocked melatonin-induced inhibition of ATP-induced IP3 accumulation. Conversely, DP-Gαq and DP-Gα11 proteins, but not the DP-Gαi2 and DP-Gαi3 proteins, significantly inhibited ATP-induced IP3 levels by 50% and 59%, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Modulation of ATP-stimulated IP3 levels by melatonin in MCF-7 cells. MCF-7 cells were transfected with DN-G proteins (a) or DP-G proteins [Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq and Gll] (b) and treated with ATP. Following the plating, the cells were incubated for 20 min in 10 mM LiCl, and then treated as described in Materials and Methods. Cell lysates were analyzed using the Inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) [3H] assay system as described in Materials and Methods. Expression of DP-G-proteins following transfection was evaluated by immunoblot analysis of duplicate cell lysates and expression is shown above the appropriate bar graphs. The data is presented as the mean IP3 (pmol/tube) × 10−2 ± S.E.M. n=3 independent experiments; a, P < 0.05 vs. control; b, P < 0.05 vs. ATP.

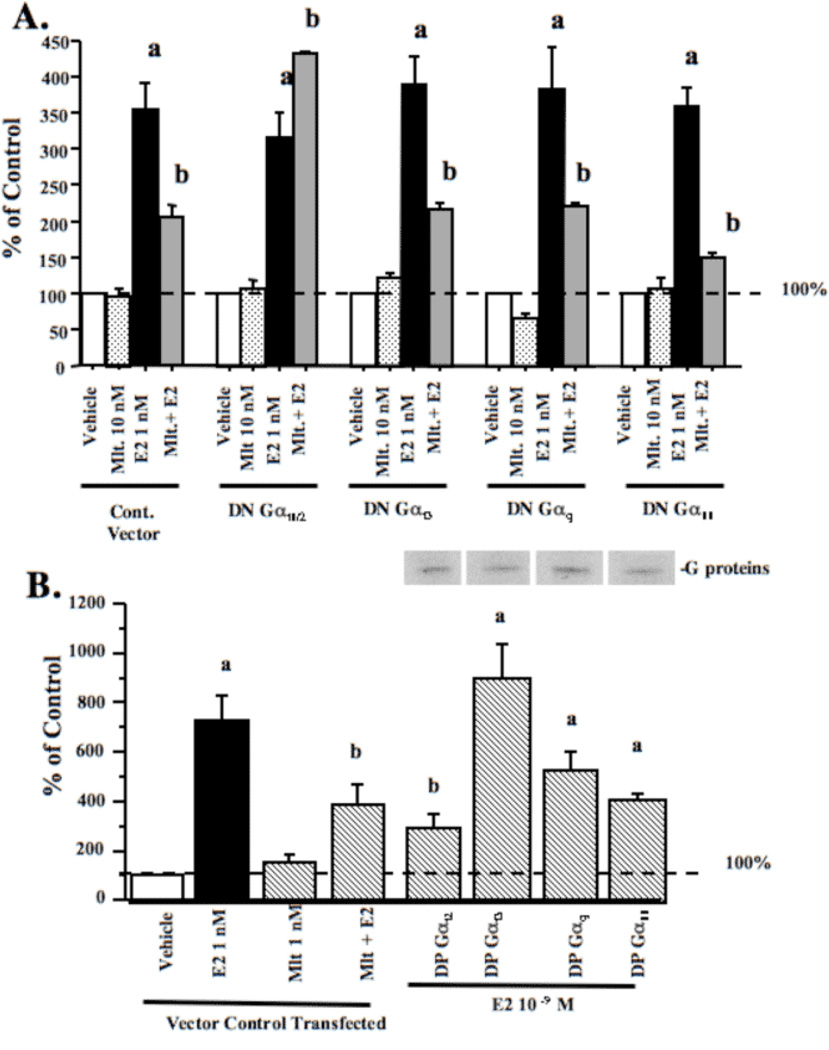

Previous reports have shown that melatonin can repress E2-induced ERα-dependent transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells [7,16,25]. Since both PTX-sensitive and-insensitive G-proteins have been shown to couple to the MT1 receptor, we examined whether the functional coupling between MT1 receptor and specific G-proteins affects ERα transcriptional activity. Treatment of MCF-7 cells transfected with ERE-luciferase reporter construct and a control vector with melatonin produced no significant change in luciferase activity, whereas E2 treatment induced 3.46-times increase in luciferase activity (Fig. 7A). However, pre-treatment with melatonin for 30 min. followed by E2 for 18 hours resulted in the 40% inhibition of ERα transcriptional activity compared to the cells treated with 1 nM E2 (Fig. 7A). The expression of DN-Gαi2 protein, but not the DN-Gαi3, DN-Gαq or DN-Gα11 proteins blocked the ability of melatonin to repress E2-induced ERα transcriptional activity. Conversely, expression of a DP-Gαi2 protein mimicked the inhibitory effect of melatonin, repressing E2-induced ERα transactivation by approximately 50% compared to control cells stimulated with E2 (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Effects of G-proteins on ERα transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells.

MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with an ERE-luciferase reporter construct and DN-G-protein plasmids. (a) Cells were treated with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), 10 nM melatonin, 1 nM E2, or pretreated with melatonin for 30 min followed by E2 and harvested for luciferase assay. (b) Effects of on melatonin-mediated inhibition of ERα transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells. Cells were treated as described above, but transfected with DP-G-protein plasmids. Expression of DP-G-proteins following transfection was evaluated by immunoblot analysis of duplicate cell lysates and expression is shown above the bar graphs. For comparison purposes vector control diluent treated values were set at 100% and activity in response to other treatments was recorded as percent of control activity. n=3 independent experiments; a, P < 0.05 vs. control; b, P < 0.05 vs. E2 alone.

In order to elucidate whether melatonin can regulate RARα transcriptional activity through the G protein-coupled MT1 receptor and its associated G-protein signaling pathways, MCF-7 cells were transiently co-transfected with DN- or DP-G-proteins, and a RARE-luciferase reporter construct and treated with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), melatonin (10 nM), atRA (1 nM), or melatonin followed by atRA as described in materials and methods. As shown in Fig. 8 in the cells transfected with the control G-protein vector, melatonin treatment alone did not modulate basal RARα transcriptional activity, while atRA stimulated a 3.46-times increase in luciferase activity. However, administration of melatonin 5 min prior to atRA, significantly enhanced atRA-induced RARα transactivation by approximately 54%. The enhancement of atRA-induced RARα transactivation by melatonin was blocked by the expression of either DN-Gαq or DN-Gα11 proteins, but not DN-Gαi1/2 or DN-Gαi3 proteins (Fig. 8A). The expression of the constitutively active DP-Gαq or DP-Gα11, but not DP-Gαi2 or DP-Gαi3 proteins, mimicked the stimulatory effect of melatonin on atRA-induced RARα transactivation, and enhanced atRA-induced luciferase activity by 46% or 69%, respectively (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Effects of melatonin and DN/DP-G-proteins on RARα transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells. (a) Effects of DN-G-proteins on melatonin-mediated enhancement of atRA-induced RARα transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells. Cells were transiently transfected with RARE-luciferase reporter construct and DN-G-protein plasmids. Cells in medium supplemented with 5% CS-FBS were treated for with vehicle (0.001% ethanol), 10 nM melatonin, 1 nM atRA, or melatonin and atRA simultaneously. (b) Effects of DP-G-proteins on melatonin-mediated enhancement of RARα transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells. Cells were transfected with an RARE as described above and DP-G-protein plasmids and treated with either vehicle (0.001% ethanol) 10 nM melatonin or 1 nM atRA. Expression of DP-G-proteins was evaluated by immunoblot analysis is shown above the bar graphs. For comparison purposes vector control diluent treated values were set at 100% and activity in response to other treatments was recorded as percent of control activity. n=3 independent experiments; a, P < 0.05 vs. control; b, P < 0.05 vs. atRA-stimulated vector controls.

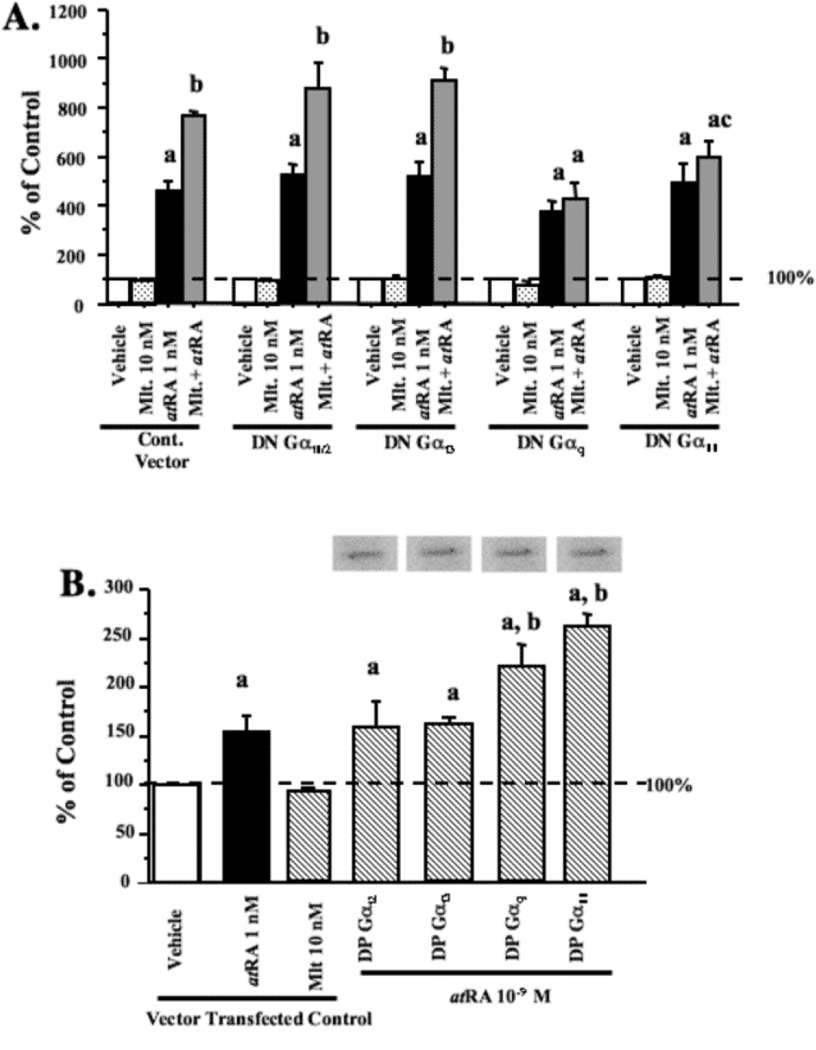

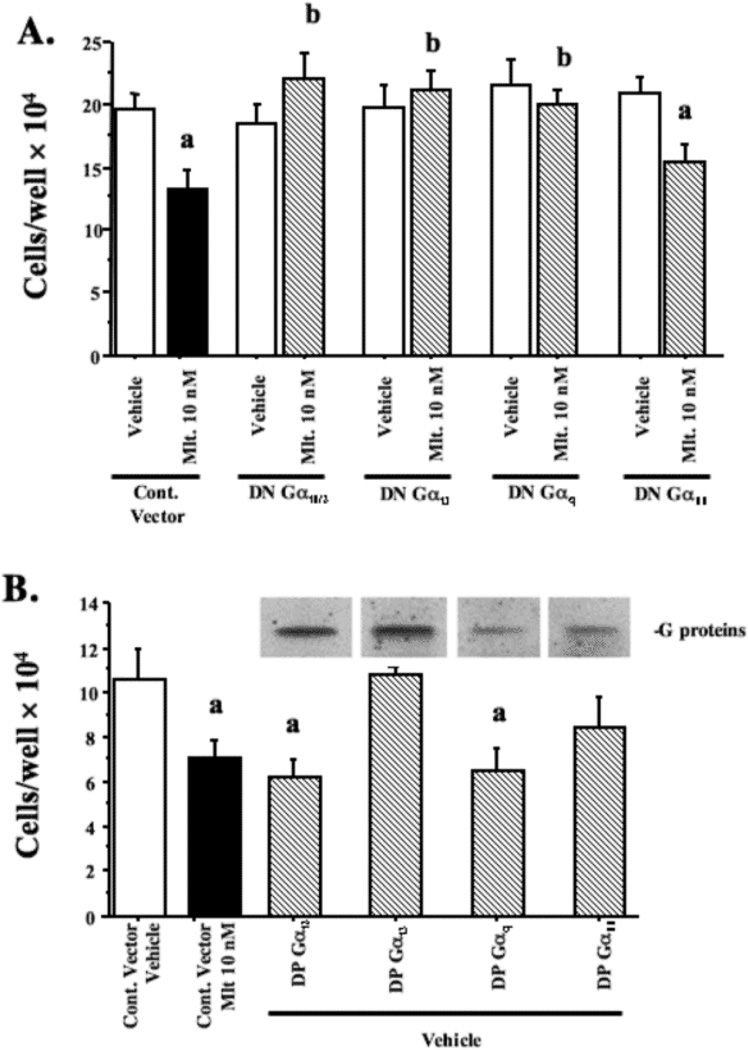

We and others have reported that the growth of MCF-7 cells is suppressed by melatonin [1,26]. To define if G-proteins that mediate the actions of melatonin on steroid hormone receptor transcriptional activity also mediate the growth-suppressive effects of melatonin, MCF-7 cells were transfected with either a control vector or a plasmid for the expression of the various DN-G-proteins and treated with either vehicle (0.001% ethanol) or melatonin (10 nM) for 7 days. Fig. 9A demonstrates that melatonin significantly suppresses cell proliferation by 43% in MCF-7 cells transfected with the control vector. The expression of DN-Gαi2, DN-Gαi3, or DN-Gαq proteins blocked the growth-inhibitory activity of melatonin. To further establish the involvement of these G-proteins in the melatonin response pathway, we examined the effect of melatonin on MCF-7 cells transiently transfected with DP-G-proteins. Expression of either the DP-Gαi2 or DP-Gαq protein, but not DP-Gαi3 or DP-Gα11 protein, mimicked the inhibitory effect of melatonin on MCF-7 cell growth, suppressing cell numbers by 45% or 48%, respectively (Fig. 9 A and B). Thus, the growth-inhibitory effect of melatonin on MCF-7 cells appears to be mediated via the activation of both Gαi2 and Gαq proteins.

Fig. 9.

Growth-inhibitory effect of melatonin regulated by Gai2 and Gaq proteins in MCF-7 cells. The MCF-7 cells were transiently transfected with control vector or (a) DN-G-protein plasmids for 8 h and then treated with 0.001% ethanol or 10 nM melatonin for 7 days; (b) MCF-7 cells were transfected with DP-G-protein plasmids for and then treated with 0.001% ethanol for 7 days. Control cells include diluent treated controls (0.001% ethanol) and melatonin (10 nM) treated controls. Expression of DP-G-proteins was evaluated by immunoblot analysis is shown above the bar graphs. Viable cells as measured by trypan blue exclusion were counted using a hemocytometer. The results represent the mean cell number × 104/well ± S.E.M. of data from at least three independent experiments each performed in triplicate; a, P < 0.05 vs. control; b, P < 0.05 vs. melatonin treated.

Discussion

In this study, we employed human breast cancer cell lines that express endogenous MT1 receptor to demonstrate the different mechanisms regulating the transcriptional activity of ERα and RARα in response to melatonin and to elucidate the underlying signaling pathways leading to the growth-inhibitory actions of melatonin in breast cancer. The starting point for our study was to determine if melatonin modulated ERα transcriptional activity in human breast cancer cell lines other than MCF-7 cells and if melatonin also modulated the transcriptional activity of ERβ. From our studies presented in figures 1 and 2, melatonin is able to repress E2-induced ERα transcriptional activity in three different ERα-positive MCF-7, T47D and ZR-75-1 cell lines, however, the actions of melatonin on ERα transcriptional activity was significantly greater in MCF-7 and ZR-75-1 cells as compared to T47D cells. This however, is not due to expression differences in the MT1 melatonin receptor in the two lines, as we have already demonstrated [27] that ZR-75-1 and T47D cells express equivalent levels of MT1 at the mRNA level, but both express somewhat lower levels of the MT1 receptor than the MCF-7 cells. We have previously reported that in a panel of 25 primary breast tumors, varying levels of MT1-melatonin receptor mRNA is expressed in the different breast tumors and breast cancer cell lines, with levels ranging from high, to very low. Furthermore, a recent report by Dillon et al. [28] has demonstrated that the melatonin MT1 receptor is expressed at different levels in different human breast tumors. Our current report is also the first to demonstrate that melatonin via its MT1 receptor, but not the MT2 receptor, represses E2-induced transcriptional activity of ERα, but not ERβ.

We next set out to identify which G-proteins coupled to the MT1 receptor in MCF-7 breast cancer cells using co-immunoprecipitation assays. Our data demonstrate that the MT1 receptor couples with a limited set of G-proteins including: Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq and Gα11 proteins, but does not couple with other G-proteins including Gαi1, Gαo, Gαz, and Gα12, which are also expressed in MCF-7 cells. The coupling of these G-proteins (Gαi2, Gαi3, Gαq and Gα11) is strictly melatonin dependent since MT1 receptor-G-protein complexes are not observed in the absence of melatonin. Our results confirm the previous report that Gαi2, Gαi3 and Gαq/11 proteins coupled to the MT1 receptor in a melatonin-dependent and guanine nucleotide-sensitive manner in HEK293 cells expressing exogenous MT1 receptor [21].

Receptors with dual signaling properties often stimulate different pathways with different efficacy. In previous work, we reported that melatonin differentially regulates the transcriptional activity of steroid/thyroid hormone receptors, suppressing ERα, RORα and GR ligand-induced transcriptional activity while potentiating RARα-induced transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells [7,16]. The concept that different G-proteins mediating different signaling pathways might be responsible for this differential response of nuclear receptors to melatonin is suggested by G-protein uncoupling studies using PTX treatment. Pre-treatment of MCF-7 breast cancer cells with PTX, which inhibits Gi protein function by ADP-ribosylation of the GDP-bounded α subunit of Gi protein [29,30], effectively abrogates the inhibitory effect of melatonin on estrogen-dependent ERα transcriptional activity, but does not affect the stimulatory effect of melatonin on atRA-dependent RARα transcriptional activity in MCF-7 cells. As well, our current results indicate that multiple heterotrimeric G-proteins (Gαi2, Gαq and Gα11) are involved in regulating the differential melatonin-dependent modulation of ERα and RARα.

The above data indicate that Gαi2 and/or Gαi3 are effectors for melatonin’s modulation of ERα signaling, whereas PTX-insensitive Gαq and Gα11 proteins are effectors for melatonin’s modulation of RARα signaling pathway in breast cancer. Melatonin can inhibit Fsk-induced cAMP levels and ATP-induced IP3 levels, but does not affect cGMP levels in breast cancer cells. As for melatonin regulation of ATP-induced IP3 levels, this action is mediated via activation of Gαq and Gα11 proteins, but not Gαi2 or Gαi3 proteins. These results are consistent with previous reports demonstrating that melatonin can modulate several G-protein-coupled intracellular signal pathways, including the cAMP [9], PKC/calcium [15,30], and MAP kinase cascades [31], which are the key second messengers in signaling systems known to modify the transcriptional activity of steroid receptors.

In breast cancer cells, it has been reported that activation of the cAMP signaling pathway can lead to ligand-dependent and ligand-independent phosphorylation of ERα, and stimulation of ERα transcriptional activity [32]. In sertoli cells, it has been reported that PKC activation can induce ligand-independent RARα transcriptional activity and modify ligand-dependent RARα transcriptional activity [33]. These studies demonstrate the critical connection of the different G-proteins to steroid hormone receptor transcriptional activity. Transient-transfection studies with DN- and DP-G-protein constructs demonstrate the specific action of Gαi2 as the mediator of melatonin’s effect on ERα transcriptional activity, and the role of Gαq and Gα11 as the mediators of melatonin’s effect on RARα activity. Furthermore, the ability of a DP-Gαi2 to mimic melatonin’s suppression of E2-induced ERα phosphorylation, suggests that melatonin via the MT1 receptor and activation of Gαi2 alters ERα transcriptional activity via modulation of ERα phosphorylation. This however, does not exclude the possibility of melatonin’s modulation of ERα transcriptional activity through phosphorylation changes in ERα co-activators (CBP, Src-1 or Calmodulin).

It is well established that nuclear and steroid hormone receptors are targets for regulation by “cross talk” from other signaling pathways [34–36]. Modulation of G-proteins in MCF-7 cells by melatonin may result in the selective phosphorylation and activation of specific steroid/thyroid hormone receptors or other transcription factors. In these studies, we have attempted to establish whether the MT1-coupled G-proteins are responsible for inhibition of MCF-7 cell growth by using a selective competitive G-protein agonist and antagonist. First, the observation that PTX prevents melatonin-induced suppression of PC12 pheochromocytoma cancer cell growth strongly implies that the MT1 receptor via Gαi proteins mediates the anti-proliferative action of melatonin [37]. Studies in which we over-expressed DN-Gαi2 and DN-Gαq suggest that not one, but both the Gαi2 and Gαq proteins play important roles in mediating melatonin’s growth inhibitory activity in MCF-7 breast cancer cells.

We have previously reported that at least part of melatonin’s anti-proliferative and E2-inhibitory effect on MCF-7 cells is mediated via suppression of E2’s non-genomic induction of cAMP [7]. The above data suggests that the down-regulation of cAMP, by melatonin, may be an initiating biochemical event in suppressing breast cancer cell proliferation. This concept is supported by studies with PC12 pheochromocytoma cell A126-1B2-1 mutants with significantly diminished PKA activity (80% reduction compared to controls), which is unresponsive to the growth-suppressive actions of melatonin [37].

To date, the exact pathway(s) downstream of the MT1 receptor that mediate breast cancer growth inhibition in MCF-7 cells, have not been definitively elucidated. Our findings demonstrate that the MT1 receptor-mediated growth-inhibitory effect of melatonin involves both the activation and suppression of the transcriptional activity of specific steroid/thyroid hormone receptors and their regulation of growth-modulatory genes via multiple G-protein coupled signal transduction pathways. In general, melatonin acts as an anti-mitogenic molecule suppressing ERα signaling and potentiating the transcriptional activity of RARα to inhibit breast tumor cell growth. Previous studies have already shown that melatonin cross talks with the estrogen signaling pathways in breast cancer, by inhibiting the expression of ERα mRNA via transcription-related events [18] decreasing the ERα-ERE complex binding stability [16], and further suppressing E2-induced ERα transcriptional activity of ERα [20]. A recent report by Del Rio et al. [25], has demonstrated that calmodulin (CaM) is essential for melatonin’s suppression of ERα transcriptional activity. This work, does not conflict with our data demonstrating that melatonin mediates ERα transcriptional activity via activation of a Gαi2 signaling pathway, as we have previously reported that melatonin can modulate CaM localization, shifting CaM from the nucleus to the cell membrane [15]. These data combined with numerous reports that Gαi proteins can regulate many second messengers including cAMP and intracellular calcium, and CaM’s reported actions as an ERα co-activator [25] suggest that melatonin modulation of CaM, although involved in regulation of ERα function, is clearly down-stream of melatonin’s action on Gαi2 proteins.

In MCF-7 cells, it has been shown that melatonin enhances atRA-induced RARα transcriptional activity using RARE-luciferase reporter assay without interfering with the expression of RARα [38]. The synergism between melatonin and the RARα signaling pathway was also demonstrated in the N-nitroso-N-methylurea (NMU)-induced rat mammary tumor model, where melatonin sensitizes not only the suppressive effect of retinoic acid on the incidence of NMU-induced mammary tumor [39], and also the regression of the carcinogen-induced mammary tumors [40].

In summary, we have demonstrated that melatonin inhibits E2-induced ERα transcriptional activity in a variety of human breast cancer cell lines, that this effect is specific for ERα and does not affect ERβ, and that these effects are mediated via the MT1 and not the MT2 melatonin receptor. MCF-7 breast tumor cells were used to study the role of heterotrimeric G-protein subunits Gαi2 and Gαq as well as ERα and RARα activity in the growth of breast cancer cells as they are growth-inhibited by melatonin. Our studies employing DN- and DP-G-proteins show that melatonin differentially regulates ERα, but not ERβ, and RARα transcriptional activity acting through different G-protein-dependent pathways by a mutant G-protein strategy. Although coupling to Gαi2 may be essential for some of the actions of melatonin, stimulation of the RARα signaling pathways seems to require functional coupling between the activated MT1 receptor and the Gαq protein family. Our results also suggest that melatonin may regulate breast cancer cell proliferation via these two separate, but interrelated, G-proteins and their downstream signaling partners (Fig. 9). Moreover, expression of the constitutively active mutants of Gαi2 and Gαq can promote growth inhibition in the absence of melatonin.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NIH/NCI grant 5R01 CA 54152-14 to SMH.

References

- 1.Hill SM, Blask DE. Effects of the pineal hormone on the proliferation and morphological characteristics of human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) in culture. Cancer Res. 1998;48:6121–6126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan L, Collins AR, Dai J, Dubocovich ML, Hill SM. MT1 melatonin receptor overexpression enhances the growth suppressive effect of melatonin in human breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;192:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourne HR, Landis CA, Masters SB. Hydrolysis of GTP by the alpha chain of GS and other GTP binding proteins. Proteins. 1989;6:222–230. doi: 10.1002/prot.340060304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neer EJ, Clapham DE. Roles of G protein subunits in transmembrane signaling. Nature. 1988;333:129–134. doi: 10.1038/333129a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birnbaumer L. Receptor-to-effector signaling through G proteins: roles for beta gamma dimmers as well as alpha subunits. Cell. 1992;71:1069–1072. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olcese J. Cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating melatonin action: a review. Aging Male. 1998;1:113–128. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiefer TL, Ram PT, Yuan L, Hill SM. Melatonin inhibits estrogen receptor transactivation and cAMP levels in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2002;;71:37–45. doi: 10.1023/a:1013301408464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godson C, Reppert SM. The Mel1a melatonin receptor is coupled to parallel signal transduction pathways. Endocrinology. 1997;138:397–404. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanecek J, Vollrath L. Melatonin inhibits cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP accumulation in the rat pituitary. Brain Res. 1989;505:157–159. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan PJ, Lawson W, Davidson G, Howell HE. Melatonin inhibits cyclic AMP in cultured ovine pars tuberalis cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1989;5:R3–R8.X. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faillace MP, Keller-Sarmiento MI, Rosenstein RE. Melatonin effect on the cyclic GMP system in the golden hamster retina. Brain Res. 1996;711:112–117.X. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilad E, Matzkin H, Zisapel N. Interaction of melatonin receptors by protein kinase C in human prostate cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4255–4261.X. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilad E, Pick E, Matzkin H, Zisapel N. Melatonin in benign prostate epithelila cells: evidence for the involvment of cholera and pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins in their signal transduction pathways. Prostate. 1998;35:27–34.X. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980401)35:1<27::aid-pros4>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popova JS, Dubocovich ML. Melatonin receptor-mediated stimulation of phosphoinositide breakdown in chick brain slices. J Neurochem. 1995;64:130–138.X. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64010130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dai J, Inscho EW, Yuan L, Hill SM. Modulation of intracellular calcium and calmodulin by melatonin in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. J Pineal Res. 2002;32:112–119. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-079x.2002.1844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiefer TL, Lai L, Burow ME, Hill SM. Differential regulation of estrogen receptor alpha, glucocorticoid receptor and retinoic acid receptor transcriptional activity by melatonin is mediated via the Gαi2 protein. J Pineal Res. 2005;38:231–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2004.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sommer S, Fuqua SA. Estrogen receptor and breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2001;11:339–352. doi: 10.1006/scbi.2001.0389. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Molis TM, Spriggs LL, Hill SM. Modulation of estrogen receptor mRNA expression by melatonin in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:1681–1690. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.12.7708056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molis TM, Spriggs LL, Jupiter Y, Hill SM. Melatonin modulation of estrogen-regulated proteins, growth factors, and proto-oncogenes in human breast cancer. J Pineal Res. 1995;18:93–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1995.tb00146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ram PT, Kiefer T, Silverman M, Song Y, Brown GM, Hill SM. Estrogen receptor transactivation in MCF-7 breast cancer cells by melatonin and growth factors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;141:53–64. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brydon L, Roka F, Petit L, de Copet P, Tissot M, Barrett P, Morgan PJ, Nanoff C, Strosberg AD, Jockers R. Dual signaling of human Mel1a melatonin Receptors via Gi2, Gi3, and Gq/11 proteins. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:2025–2037. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.12.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witt-Enderby PA, Masana MI, Dubocovich ML. Physiological exposure to melatonin supersensitizes the cyclic adenosine 3’, 5’-monophosphate-dependent signal transduction cascade in Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing the human mt1 melatonin receptor. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3064–3071. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.7.6102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardinali DP, Bonanni-Rey RA, Mediavilla MD, Sanchez-Barcelo E. Dirunal changes in cyclic nucleotide response to pineal indoles in murine mammary glands. J Pineal Res. 1992;13:111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079x.1992.tb00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalsi JS, Rees RW, Hobbs AJ, Royle M, Kell PD, Ralph DJ, Moncada S, Cellek S. BAY41-2272, a novel nitric oxide independent soluble guanylate cyclase activator, relaxes human and rabbit corpus cavernosum in vitro. J Urol. 2003;169:761–766. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000043880.58140.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Del Rio B, Garcia-Pedrero JM, Martinez-Campa C, Zuazua P, Lazo PS, Ramos S. Melatonin: An endogenous specific inhibitor of estrogen receptor alpha via calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38294–38302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cos S, Sanchez-Barcelo E. Melatonin modulates growth factor activity in MCF-7 human breast cancer cell growth; influence of cell proliferation rate. Cancer Lett. 1995;93:207–212. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03811-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ling L, Kiefer T, Burow M, Yuan L, Cheng Q, Hill SM. Gi and Gq proteins mediate the effects of melatonin on steroid receptor transcriptional activity. 95th Annual Mtg. American Association for Cancer Research. 2004 Abst. 2335. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillon DC, Easley SE, Asch BB, Cheney RT, Brydon L, Jockers R, Winston JS, Brooks JS, Hurd T, Asch HL. Differential expression of high-affinity melatonin receptors (MT1) in normal and malignant breast tissue. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:451–453. doi: 10.1309/1T4V-CT1G-UBJP-3EHP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ui M, Katada T. Bacterial toxins as probe for receptor-Gi coupling. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1990;24:63–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McArthur AJ, Gillette MU, Prosser RA. Melatonin action and signal transduction in the rat suprachiasmatic circadian clock: activation of protein kinase C at dusk and dawn. Endocrinology. 1997;138:627–634. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.2.4925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan ASL, Lai FPL, Lo RKH, Voyno-Yasenetskaya TA, Stanbridge EJ, Wong YH. Melatonin MT1 and MT2 receptors stimulate c-Jun N-terminal kinase via pertussis toxin-sensitive and -insensitive G proteins. Cell Signal. 2002;14:249–157. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00240-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho H, Katzenellenbogen BS. Synergistic activation of estrogen receptor-mediated transcription by estradiol and protein kinase activators. Mol Endocrinol. 1993;7:441–452. doi: 10.1210/mend.7.3.7683375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith CL. Cross talk between peptide growth factor and estrogen receptor signaling pathways. Biol Reprod. 1998;58:627–632. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.3.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braun KW, Vo MN, Kim KH. Positive regulation of retinoic acid receptor alpha by protein kinase C and mitogen-activated protein kinase in sertoli cells. Biol Reprod. 2002;67:29–37. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod67.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato S, Masuhiro Y, Watanabe M, et al. Molecular mechanism of a cross-talk between oestrogen and growth factor signalling pathways. Genes Cells. 2000;5:593–601. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee YN, Park YG, Choi YH, Cho YS, Cho-Chung YS. CRE-transcription factor decoy oligonucleotide inhibition of MCF-7 breast cancer cells: cross-talk with p53 signaling pathway. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4863–4868. doi: 10.1021/bi992272o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roth JA, Rosenblatt T, Lis A, Bucelli R. Melatonin-induced suppression of PC12 cell growth is mediated by its Gi coupled transmembrane receptors. Brain Res. 2001;919:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eck-Enriquez K, Kiefer TL, Spriggs LL, Hill SM. Pathways through which a regimen of melatonin and retinoic acid induces apoptosis in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2000;61:229–239. doi: 10.1023/a:1006442017658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teplitzky SR, Kiefer TL, Cheng Q, et al. Chemoprevention of NMU-induced rat mammary carcinoma with the combination of melatonin and 9-cis-retinoic acid. Cancer Lett. 2001;168:155–163. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00548-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melancon K, Cheng Q, Kiefer TL, et al. Regression of NMU-induced mammary tumors with the combination of melatonin and 9-cis-retinoic acid. Cancer Lett. 2005;227:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]