Abstract

Context

Rising drug costs have increased focus on how new pharmaceuticals diffuse into the marketplace. The case of gabapentin use in bipolar disorder (BPD) provides an opportunity to study the roles of marketing, clinical evidence, and prior authorization (PA) policy on off-label medication use.

Design

Observational study using Medicaid administrative and Verispan marketing data. We examined the association between marketing, clinical trials, and prior authorization on gabapentin use.

Setting and Patients

Florida Medicaid, BPD-diagnosed enrollees ages 18–64 for fiscal years 1994–2004.

Results

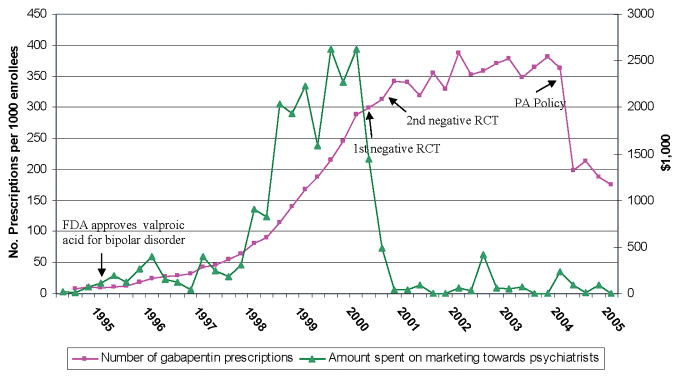

Gabapentin prescriptions increased from 8/1000 enrollees per quarter in 1994 to a peak of 387/1000 enrollees in 2002. Its uptake tracked marketing efforts towards psychiatrists. The publication of two negative clinical trials in 2000 and the discontinuation of marketing expenditures towards psychiatrists were associated with an end to the steep rise in gabapentin prescriptions. After these events gabapentin use remained between 319/1000 and 387/1000 enrollees per quarter until the PA policy, which was associated with a 45% decrease in prescriptions filled. After one year, scientific evidence and marketing discontinuation were associated with a 5.4 percentage point decrease in the predicted probability of filling a gabapentin prescription and the PA policy, a 7.1 percentage point decrease.

Conclusions

Pharmaceutical marketing can influence off-label medication prescribing, particularly when pharmacologic options are limited. Evidence of inefficacy and/or the cessation of pharmaceutical marketing, and a restrictive formulary policy can alter prescriber behavior away from targeted pharmacologic treatments. These results suggest that both information and policy are important means in altering physician prescribing behavior.

Background

Increasing costs for prescription drugs over the past decade(1, 2) have spurred interest in examining how new pharmaceuticals are incorporated into medical practice. Information about new drugs and payment policy can affect the uptake (and abandonment) of pharmaceutical products(3). Prescribing clinicians learn about new drugs from multiple sources including pharmaceutical manufacturers, scientific literature, peers, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Organizations interested in the efficiency of care delivery, such as pharmacy benefit managers and other payers, implement policies such as prior authorization policies or co-payments favoring generics or preferred drugs to promote cost-effective treatment(4–9).

The use of gabapentin in bipolar disorder (BPD) treatment provides an informative case of off-label uptake and abandonment of a new medication. Gabapentin was patented by Warner-Lambert in 1977 and FDA-approved in December1993 for the adjunctive treatment of epilepsy and in 2002 for postherpetic neuralgia (see Appendix 1 for timeline). A lawsuit unsealed in 1999 showed that gabapentin’s maker Warner-Lambert and its marketing division Parke-Davis promoted gabapentin heavily for multiple off-label indications(10). As a result, studies estimate that 83–95% of gabapentin use was off-label and aimed towards indications such as pain, BPD, restless leg syndrome, and anxiety(11–13). Pfizer acquired Warner-Lambert in 2000 and in 2004 settled a $430 million false claims suit for Parke-Davis’s promotion of gabapentin for off-label indications. After the settlement, several state Medicaid programs, including Florida(14, 15), implemented prior authorization policies restricting gabapentin use to only FDA-approved indications.

Appendix 1.

Timeline of events pertaining to the use of gabapentin for bipolar disorder

| Month and Year | Event |

|---|---|

| May, 1977 | U.S. Patent granted to Warner-Lambert for gabapentin |

| December, 1993 | Gabapentin is FDA-approved for adjunctive treatment of partial complex seizures in individuals over 12 years old |

| June, 1995 | Depakote, an anticonvulsant drug, is approved to treat bipolar mania |

| August, 1996 | Lawsuit filed by a former Parke-Davis employee against Warner-Lambert for illegal marketing of gabapentin for off-label uses |

| December, 1999 | Seal on above lawsuit is lifted and litigation resumes. |

| June, 2000 | Pfizer acquires Warner-Lambert and its marketing division Parke-Davis |

| Sept, 2000 | Publication of 1st RCT that showed that gabapentin had no efficacy in the treatment of BPD |

| October, 2000 | Gabapentin is FDA-approved for adjunctive treatment of partial seizures in patients ages 3–12 years old. |

| December, 2000 | Publication of 2nd RCT that showed that gabapentin had no efficacy in the treatment of BPD |

| May, 2002 | Gabapentin is FDA-approved for treatment of postherpetic neuralgia in adults. |

| May, 2004 | Pfizer agrees to a $430 million settlement for Warner-Lambert’s promotion of gabapentin for uses not approved by the FDA |

| July 1, 2004 | Florida Medicaid institutes a prior authorization program restricting gabapentin use to FDA approved indications |

Off-label use of medications is common in medicine and can be clinically appropriate. Estimates suggest 21% of medication use is off-label(13). Clinical research often supports the efficacy of pharmaceutical treatment for off-label indications. While a drug is still under patent, a manufacturer can seek additional FDA indications in such circumstances. In the case of gabapentin, evidence for the use of gabapentin for neuropathic pain syndromes supported off-label use(16–18).

Gabapentin use in BPD is especially instructive because of two factors: the aggressive marketing tactics aimed at off-label gabapentin use that promoted its use for BPD and the emergence of clear evidence that gabapentin was not effective in treating BPD. Prior to this evidence, Warner-Lambert actively disseminated information promoting the use of gabapentin for BPD through Continuing Medical Education programs, dinners, and journal articles based on open-label trials and case studies(10, 19) which resulted in significant use of gabapentin for BPD. In 2000, two randomized, placebo-controlled trials showed no advantage for gabapentin over placebo in any stage of BPD (20, 21). In fact, one study showed gabapentin to be inferior to placebo in the treatment of bipolar mania (20). The clear evidence that emerged regarding the lack of efficacy for gabapentin in treating BPD distinguishes it from other medications used off-label for BPD.

This case study investigates the effects of marketing, research, and the PA policy on the uptake and abandonment of gabapentin in BPD. In particular, we examine the level of marketing towards psychiatrists and adoption of gabapentin in a bipolar cohort in the absence of scientific evidence. We then test the effects of two events, the publication of scientific evidence and the implementation of the PA policy, on both the trend and immediate use of gabapentin in a bipolar cohort.

Methods

Overview

We use two approaches to examine gabapentin use over time for BPD. First, we present descriptive data showing the volume of gabapentin prescriptions and national estimates of promotional spending towards psychiatrists. Second, we apply a statistical model of product diffusion based on logistic regression to estimate the relationship between receiving gabapentin and measures of promotional activity, new research findings, and Florida’s PA policy.

Data Sources

We used administrative data from Florida’s Medicaid program for fiscal years 1994–2004. During this time, Florida’s Medicaid program was primarily fee-for-service, had enrollment ranging from 2.1 to 2.9 million people, and was the fourth largest in the United States(22).

We used Verispan data for fiscal years 1994–2004 to estimate promotional activity for gabapentin directed towards psychiatrists. These data combine two surveys, the detailing audit and the physician meeting and event audit (PMEA), to provide estimates of national, quarterly, marketing data encompassing detailing, physician meetings, and firm-sponsored events (e.g. teleconferences, symposia, dinners, etc.). The detailing survey asks a panel of physicians to report on detailing they received and assigns monetary amounts to each product included in a detailing call. The PMEA surveys physicians to report all firm-sponsored events and assigns monetary amounts to different types of events. Verispan data has been used by industry to estimate product promotion as well as other research studies(23).

Bipolar Cohort

The Medicaid data included enrollees’ age, gender, race/ethnicity, eligibility category, clinical diagnoses, and pharmaceutical utilization. Mental health cohorts derived from claims data have demonstrated validity with positive predictive values of 95% (24, 25). We employed similar, but more stringent, criteria that has been used in other studies(26–33). Our bipolar cohort included enrollees if they were between the ages of 18–64 and had two service claims for BPD on different dates (including ICD9-CM codes 296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.89, 301.11, 301.13). To minimize false positives but include persons more difficult to engage in treatment, enrollees with only one bipolar claim were included if it represented either an inpatient discharge diagnosis or an outpatient visit that accounted for at least 50% of mental health visits. Since this study focuses on medications for BPD, we required at least one BPD claim be submitted by a psychiatrist because of their greater expertise in diagnosing and medicating BPD. Individuals were excluded if they had claims for schizophrenia within one year of a bipolar diagnosis. We excluded enrollees in Medicaid eligibility categories for which we had incomplete pharmaceutical claims data: i.e. enrollees in an HMO or Medicare partial dual eligible’s (the QMB/SLMB’s) which represent around 2–3% of Florida Medicaid beneficiaries(34). The number of enrollees with BPD per quarter ranged from 6,015 in the 4th quarter of 1995 to 12,591 in the 3rd quarter of 2002.

Outcome Variables and Independent Variables

Our outcome variable was gabapentin use, defined as whether or not an individual with BPD filled a gabapentin prescription in a given quarter.

Our main explanatory variables were three factors hypothesized to affect product diffusion: 1) promotional spending 2) the publication of scientific evidence regarding gabapentin’s efficacy in BPD and 3) the implementation of the PA policy. Quarterly, promotional activity was lagged one quarter and measured in millions of dollars. We included promotional activity directed towards psychiatrists and not other physicians for two reasons. First, promotional activity for the treatment of BPD would be aimed at psychiatrists. Second, all promotional activity for gabapentin aimed at psychiatrists would be for off-label indications because there were no psychiatric indications approved by the FDA or backed by randomized clinical trials. The Verispan data showed that the percentage of promotional spending aimed towards psychiatrists varied over time from 0% to 55%. The two studies demonstrating gabapentin’s lack of efficacy for BPD were published in September and December 2000. We used a dichotomous indicator that took on a value of one after the second publication (i.e. the first quarter 2001) to represent the time period when trial results were publicly available. Florida’s Medicaid program implemented its PA policy on July 1, 2004. The PA policy required prior authorization for gabapentin prescriptions for indications other than seizures, diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuropathy, or ALS. A dichotomous variable representing the PA policy took the value of one from the third quarter 2004.

The statistical model also included the following, individual covariates: age, sex, race, geographic region of the state, receipt of SSI, Medicare enrollment, comorbid conditions associated with gabapentin use, and mental health specialty treatment. Comorbid conditions included epilepsy, pain (including neuropathic pain), anxiety, and substance use. An individual was considered to have a comorbid condition by the presence of two or more related ICD9-CM codes at different times over study period. A mental health prescriber was considered present when an enrollee had a psychiatric hospitalization or an outpatient claim from a psychiatrist in the current or previous quarter.

Statistical Analysis

Our quarterly, descriptive analysis includes the unadjusted, aggregate number of gabapentin prescription fills and the amount spent on marketing towards psychiatrists from July, 1994 through June, 2005 as well as the publication of the randomized control trials and the implementation of the Medicaid PA policy.

To quantify the impact of product promotion, scientific evidence, and the PA policy on gabapentin’s diffusion over time in Florida, we fit a logistic regression model. Since we examine repeated observations of the same enrollees, we use a generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach with non-Gaussian data and an exchangeable correlation structure to account for individual clustering(35). This approach is robust to misclassification of correlation. We chose a logistic regression over an aggregate time-series regression in order to adjust for individual, case-mix variations over time. We fit the following model to examine marketing as well as the effects of the two events on trend and the probability of immediate use.

Where t represents time and takes on values from 1 to 44 indicating the number of quarters since the beginning of the study; RCT is a dichotomous variable indicating the publication of scientific evidence; t1 equals 0 for the quarters prior to the publications and takes on values 1 to 17 indicating the number of quarters since publication; PA is an dichotomous variable marking the implementation of the PA policy, t2 takes the value of 0 for the quarters prior to the PA policy and then 1 to 4 indicating the number of quarters since the start of the PA policy; marketing is a quarter-lagged variable; and Χ represents the individual covariates described above. β1 represents the time trend prior to the publication of scientific evidence. β2 and β4 represent the immediate effects of the scientific publications and PA policy, respectively, on the probability of receiving gabapentin. β3 and β5 represent the change in time trend after the two events. The sum of β1 and β3 represent the time trend after the publications and the sum of β1, β3, and β5 represents the time trend after the PA policy. Because we use two lagged, independent variables (marketing and mental health prescriber), the first of the 44 quarters is dropped from the estimation.

We use the model estimates to calculate a variable’s impact on predicted probability of receiving gabapentin. We estimate the immediate effects as the difference between the predicted probability if the event (i.e., scientific evidence, PA policy) were not to happen and the impact of the regression with β2 and β4 turned on and β3 and β5 turned off. To describe the dynamic effect of the change in time trend, we show the difference in slope and probability that would occur in one year if no event occurred and the event only impacted the slope (i.e. β2 and β4 are equal to zero).

Results

We analyzed a Florida, Medicaid cohort consisting of 23,831 individuals with BPD and 427,694 person-quarters (Table 1). The cohort was predominantly female with high rates of co-occurring disorders such as substance use, anxiety, and pain.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Individual-Quarter observations

| Variable | Individuals | Individual-Quarters |

|---|---|---|

| N | 23,831 | 427,694 |

| Age* | 36.6±11.6 | 40.7 ± 11.5 |

| Female | 69.7% | 69.4% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Non- Hispanic White | 71.6% | 69.9% |

| Non- Hispanic Black | 8.8% | 8.7% |

| Hispanic | 6.4% | 4.7% |

| Other/Missing Race | 13.2% | 16.7% |

| Medicaid Eligibility Criteria** | ||

| Social Security Insurance | 43.7% | 43.5% |

| Medicare Full Dual Eligible | 20.8% | 35.2% |

| Other*** | 36.1% | 21.3% |

| Co-Occurring disorders | ||

| Epilepsy | 4.0% | 5.7% |

| Substance Use Disorder | 22.5% | 25.4% |

| Anxiety | 18.2% | 23.9% |

| Pain | 43.1% | 54.4% |

| Mental Health Prescriber | n/a | 50.2% |

| Average # quarters in sample | 17.9±13.0 | n/a |

For individuals, this reports the average age for the quarter in which the individual entered the cohort

For individuals, this reports the Medicaid eligibility criteria for the quarter in which they entered the cohort

Includes Medically Needy, AFDC, general assistance, HMO ineligible, OBRA children, and Foster Care

Trends in use and marketing

Quarterly estimates of gabapentin prescription fills in Florida ranged from a minimum of 8/1000 enrollees in the first quarter to a maximum of 387/1000 enrollees in the third quarter of 2002 (Figure 1). Quarterly national spending on marketing to psychiatrists ranged from zero during the end of 2001 and 2003 to a high of $2,622,000 during the second quarter of 2000. The dramatic growth in gabapentin use to treat BPD between 1997 and 2000 closely tracked spending on marketing to psychiatrists. The publications of the randomized control trials corresponded to a sharp decline in the rate of growth in use of gabapentin and a dramatic decrease in marketing to psychiatrists. After two quarters, promotional activity towards psychiatrists fell from $1,442,000/quarter to $37,000/quarter (a 97.5% decrease) and remained relatively low until the end of the study period. After the publications of the randomized control trials, the use of gabapentin remained relatively constant ranging from 319/1000 enrollees to 387/1000 enrollees until the implementation of the PA policy. The PA policy was associated with an immediate 45% decrease in the number of gabapentin prescriptions from 362/1000 enrollees to 199/1000 enrollees. After the PA policy, the number of gabapentin prescriptions hovered from 175/1000 enrollees to 215/1000 enrollees.

Figure 1.

Interrupted time series of number of prescriptions by quarter and marketing by quarter. Four events have been noted in the time series: (1) the quarter of FDA approval for valproic acid for BPD; (2) the quarters of the publication of the 1st and 2nd randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCT) that showed gabapentin’s lack of efficacy in BPD; (3) the quarter in which Florida’s prior authorization (PA) policy was implemented.

Regression results: Estimation of Impact

The regression analysis confirms that all three variables of interest—marketing, scientific literature, and PA policy—had statistically significant affects on the probability of gabapentin use in Florida (Table 2). Marketing expenditures were positively associated with gabapentin use; publication of inefficacy evidence and the PA policy were associated with declines in gabapentin prescribing. The publication of scientific evidence had the combined effect of decreasing the predicted probability of receiving gabapentin by 5.4% at one year from 17.1% to 11.7% (Table 2). As might have been expected, the publications of these trials had a stronger effect on the time trend of use than on the immediate impact, which showed a slight increase at the time of the publication (Table 3). The combined effect of the PA policy after one year was to decrease the predicted probability of receiving gabapentin by 7.1% (Table 2). In contrast to the publications, the PA policy had a strong immediate impact and a smaller impact on the time trend (Table 3). Overall, individual characteristics played a smaller role in predicting the probability of gabapentin use (data not shown; see Appendix 2).

Table 2.

Estimation of Impact: Logistic regression results and the combined effects of the publication of scientific evidence and the PA policy on the predicted probability of receiving gabapentin

| Variable | β | Std Error | Predicted Probability (CI): One Year After Event | Change in Predicted Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t: Quarter | 0.14** | 0.00 | - | - |

| Publication of scientific evidence | ||||

| Evidence | 0.10* | 0.04 | 11.7% (11.6–11.8) | −5.4%§ |

| Evidence × t1 | −0.14** | 0.01 | ||

| Implementation of the PA policy | ||||

| PA Policy | −0.65** | 0.04 | 5.2% (5.1–5.2) | −7.1%§ |

| PA Policy × t2 | −0.08** | 0.01 | ||

| Marketing (per million) | ||||

| Marketing | 0.09** | 0.02 | - | 0.6%§§ |

Model 1 Wald chi2 (df 28) = 2935 with p < 0.00001

p < 0.05

p<0.001

Difference from predicted probability after 1 year if event did not occur

Difference shown is calculated from the difference in predicted probability for a marketing effort of 1 million dollars per quarter and 2 million dollars per quarter

Table 3.

The impact of the publication of scientific evidence and the PA policy on the immediate probability of gabapentin use and the time trend of gabapentin use

| Immediate Impact | Time Trend | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted probability* | Slope of logistic GEE model | Change in predicted probability after 1 year** | ||||||

| Without event | With event | Change | Without event | With event | Without event | With event | Change | |

| Evidence | 12.5% | 13.6% | 1.1% | 0.14 | 0 | 4.6% | −0.4% | −5.0% |

| PA policy | 12.4% | 7.0% | −5.4% | 0 | −0.08 | −0.2% | −2.3% | −2.1% |

Calculated as the difference between the predicted probability if the event were not to happen and the impact of the regression with the coefficients for the time trend turned off.

Calculated as the difference between the predicted probability after one year with the coefficients for the immediate impact turned off

Appendix 2.

Individual covariates and predicted probabilities from the generalized estimating equation predicting quarterly gabapentin use

| β | SD | Predicted Probability | Difference in Predicted Probability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.01** | 0.00 | - | 0.8%*** |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | - | - | 7.4%(7.4–7.4) | - |

| Female | −0.02 | 0.07 | 7.4%(7.4–7.4) | 0.0% |

| Race and Ethnicity | ||||

| White | - | - | 7.7%(7.7–7.7) | - |

| Black | −0.42* | 0.12 | 5.3%(5.3–5.4) | −2.4% |

| Hispanic | −0.19 | 0.13 | 6.6%(6.5–6.6) | −1.1% |

| Other Race | −0.10 | 0.07 | 7.0%(7.0–7.0) | −0.7% |

| Eligibility | ||||

| Other Eligibility | - | - | 6.6%(6.6–6.6) | - |

| SSI | 0.04 | 0.06 | 6.9%(6.9–6.9) | 0.3% |

| Medicare | 0.31** | 0.07 | 8.5%(8.5–8.6) | 1.9% |

| Presence of Mental Health Prescriber | ||||

| Other prescriber | - | - | 6.1%(6.0–6.1) | - |

| Mental Health Prescriber | 0.42** | 0.02 | 8.7%(8.7–8.7) | 2.6% |

| Comorbid Illness | ||||

| Epilepsy | −0.56 | 0.35 | 4.4%(4.4–4.4) | −3.2%§ |

| Substance Use | 0.36** | 0.06 | 9.2%(9.2–9.3) | 2.5%§ |

| Pain | 0.48** | 0.06 | 8.7%(8.7–8.7) | 3.0%§ |

| Anxiety | 0.25** | 0.06 | 8.7%(8.6–8.7) | 1.8%§ |

Model 1 Wald chi2 (df 28) = 2935 with p < 0.00001

p < 0.05

p<0.001

Difference shown is between 10 years of age. Predicted probabilities for this difference were calculated with age equal to 30 years old and 40 years old.

Discussion

During the decade studied, gabapentin use for BPD in Florida increased significantly in tandem with its marketing towards psychiatrists. When new evidence showing gabapentin to be ineffective in treating BPD became available and the marketing was discontinued, the rapid growth of gabapentin use stopped while the level of its use remained constant. The PA policy was associated with a substantial decrease in the immediate use of gabapentin but a more limited effect on the trend of gabapentin use in BPD. These results are not surprising. One would expect a restrictive policy’s immediate impact to be more pronounced while the impact of literature and marketing would accumulate over time.

These findings raise two fundamental questions. First, in the absence of convincing evidence, why was there such a brisk uptake of gabapentin in treating BPD? Second, why did the high rate of gabapentin use persist even after the publication of two randomized trials showing it to be ineffective?

Past studies have shown a clear relationship between the promotion of drugs to physicians and a medications use(36, 37). In the case of gabapentin, Florida physicians adopted this treatment quickly for BPD even though little research supported such use. This pattern is reflected in national data illustrating a similar uptake of gabapentin for multiple off-label indications(10). Two factors contributed to this pattern of diffusion: Warner-Lambert’s active dissemination of information encouraging the use of gabapentin in BPD and the clinical context for the treatment of BPD.

Warner-Lambert’s promotional efforts would not have succeeded without a reasonable clinical rationale for using gabapentin for BPD. Gabapentin was the first medication launched of a new generation of anti-convulsants. The previous generation included valproic acid and carbamazapine both of which demonstrated efficacy in treating bipolar mania in randomized, placebo-controlled trials(38, 39) and were accepted treatments for BPD in addition to lithium by 1994. These three medications required monitoring of blood levels, they could be poorly tolerated, and some patients displayed only a partial response(40–42). These limitations contributed to a precedent of off-label prescribing for BPD with 1st and 2nd generation antipsychotics and novel anticonvulsants. Further, multiple drugs released in the 1990s that were initially used off-label for BPD (e.g., lamotrigine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) later received FDA approval for at least one phase of BPD based on evidence of clinical efficacy(43–47). Unlike its predecessors, gabapentin was easy to use. It required no blood monitoring and had few serious side effects. Physicians facing a complicated illness with limited FDA-approved treatment options may have found gabapentin an attractive alternative to the three agents in common use at the time of gabapentin’s release. The result was a rapid increase in its market share.

The publication of two negative randomized controlled trials and the concurrent drop in marketing stopped the rapid growth of gabapentin but did little to reduce the immediate level of use. In fact, the number of filled prescriptions continued to rise--albeit more slowly--until 2002. Research shows that changing behavior through information alone has mixed results. On the one hand, active dissemination either through pharmaceutical detailing by sales representatives, FDA black box warnings, or strong media campaigns, can promote behavior change(48, 49). Gabapentin’s uptake reflects the success of such dissemination. On the other hand, the simple diffusion of guidelines or studies reported in scientific journals and at meetings take time(50). In medicine, the volume of scientific publications makes synthesizing results difficult for physicians, and the diffusion of clinical guidelines has resulted in, at best, modest success(51–54). For gabapentin use in BPD, the two randomized, placebo-controlled trials were published in relatively obscure journals with limited circulation and reinforced in 2002 through the American Psychiatric Association’s updated treatment guidelines(43). These results likely contributed to the halt in the marketing of gabapentin towards psychiatrists. The combination of negative results and decline in marketing resulted in stopping the uptake of gabapentin with little change in the level of use raising questions about the short-term effectiveness of passive diffusion of information in altering physician-prescribing behavior. Unfortunately, since the publication of the negative trials and discontinued marketing of gabapentin occurred at a similar time-point, we are unable to examine the independent associations of these events with gabapentin prescribing.

Given the negative publicity around the litigation regarding the off-label use of gabapentin, the slow diffusion of the clinical results, and the increasing use of atypical antipsychotics and lamotrigine in BPD, the rate of gabapentin use would likely have decreased slowly even without the PA policy. The PA policy, however, had a large and immediate impact on gabapentin’s use. Prior authorization policies and other payment policies are blunt tools and the consequences of limiting pharmacological treatments can be concerning. Psychiatric medications have often been excluded from PA policies because the wide variability in response to these medications requires multiple treatment options(55). In the case of gabapentin, the PA policy appropriately stopped its use for BPD but may have interfered with its use for other indications for which there was stronger evidence.

There are several limitations in this study. First, claims-based studies are limited by the absence of clinical detail. Second, we do not know the clinical rationales for gabapentin use at the patient level. There was a high rate of comorbidity in this population; possibly the clinical decision-making included treatment of comorbid conditions for which gabapentin is efficacious. For this reason, we controlled in the model for the comorbidities most likely to be treated with gabapentin. Third, the Verispan data were national and not specific to Florida. However, there is no reason to believe that Florida was immune from the national trends in promotional activities. In fact, Florida Medicaid presented evidence at the trial suggesting that it was fully included in Parke-Davis’s off-label promotion of gabapentin. The Verispan data did not include journal ads and direct to consumer advertising (DTCA). Past research has shown that the amount spent on journal ads is small compared to other promotional activities(56). Further, there was no DTCA for gabapentin use in BPD because the FDA only allows DTCA for FDA-approved indications. Next, Florida Medicaid does not identify in their claims data the type of physician prescribing gabapentin. To address this limitation, our cohort included only individuals who had bipolar diagnosed by a psychiatrist and we controlled in the model for whether or not an individual appeared to be in active treatment by a psychiatrist. Finally, we examined gabapentin use for BPD in a Medicaid population because Medicaid insures a high percentage of individuals with severe mental illness such as BPD. However, the generalizability of this study to a commercially-insured population may be limited.

Understanding the factors driving the diffusion of pharmaceuticals and medical technologies may help promote more efficient health systems. The rise and fall of off-label gabapentin use in BPD in Florida illuminates the complex interplay of product promotion, scientific evidence, and PA policy in the clinical context of a challenging illness. Even in the absence of convincing evidence, the use of gabapentin for BPD was encouraged by an effective marketing campaign and a clinical precedent for using anticonvulsants in the treatment for BPD. The availability of new evidence and a discontinuation of marketing halted the aggressive growth of gabapentin for use in BPD in Florida while Florida’s PA policy changed immediate levels of use. These results suggest that both information and policy are important means in altering physician-prescribing behavior. Information shapes growth trends and thus its effects grow larger over time. Policy has a larger immediate impact yet should remain limited to where there is clear evidence regarding effectiveness. Utilizing both methods will be important as we attempt to improve efficiency in our health system.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following funding support from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) grants: 5T32 MH019733, 5R01 MH069721, 2R01 MH061434, and K01 MH071714.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Christina Fu for excellent programming support. Haiden Huskamp, Anthony Weiss, and Roy Perlis offered thoughtful comments on previous drafts of this paper. We thank Sharon-Lise Normand, James O’Malley, Thomas McGuire, Tim Manning and Brian Neelon for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper were presented at the 25th Academy Health Annual Research Meeting on June 9th, 2008 in Washington DC.

References

- 1.Kaiser Family Foundation. Prescription Drug Trends. 2007;(5) Available at: http://www.kff.org/rxdrugs/upload/3057_06.pdf.

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 25, 2008];National Health Expenditure Accounts, Historical. Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/

- 3.Geroski PA. Models of technology diffusion. Research Policy. 2000;29:603–625. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, et al. Listening to generic prozac: winners, losers, and sideliners. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:210–216. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.5.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Use of atypical antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia in Maine Medicaid following a policy change. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:w185–w195. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.w185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delate T, Mager DE, Sheth J, et al. Clinical and financial outcomes associated with a proton pump inhibitor prior-authorization program in a Medicaid population. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer MA, Cheng H, Schneeweiss S, et al. Prior authorization policies for selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in Medicaid: a policy review. Med Care. 2006;44:658–663. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000218775.04675.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siracuse MV, Vuchetich PJ. Impact of medicaid prior authorization requirement for COX-2 Inhibitor drugs in Nebraska. Health Serv Res. 2008;43:435–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00766.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smalley WE, Griffin MR, Fought RL, et al. Effect of a prior-authorization requirement on the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs by Medicaid patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1612–1617. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506153322406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinman M, Bero LA, Chren M-M, et al. Narrative review: The promotion of gabapentin: An analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:284–293. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, Deshpande AD, Jiang R, et al. An epidemiological investigation of off-label anticonvulsant drug use in the Georgia Medicaid population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:629–638. doi: 10.1002/pds.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamer AM, Haxby DG, McFarland BH, et al. Gabapentin Use in a Managed Medicaid Population. J Manag Care Pharm. 2002;8:266–271. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2002.8.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford R. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1021–1026. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Florida Medicaid. [Accessed March 5, 2008];Medicaid Prescribed Drug Spending Control Program Initiatives: Quarterly Report, July 1-September 30, 2004. 2004 Available at: http://www.fdhc.state.fl.us/Medicaid/Prescribed_Drug/pdf/quarterly_report_09_30_04.pdf.

- 15.Agency for Health Care Administration: Medicaid Services. [Accessed March 5, 2008];Historical Remittance Banner Messages. Available at: http://www.fdhc.state.fl.us/Medicaid/Prescribed_Drug/banner_history.shtml.

- 16.Serpell MG group Nps. Gabapentin iin neuropathic pain syndromes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pain. 2002;99:557–566. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rowbotham M, Harden N, Stacey B, et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of postherpectic neuralgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1837–1842. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.21.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morello CM, Leckband SG, Stoner CP, et al. Randomized double-blind study comparing the efficacy of gabapentin with amitriptyline on diabetic peripheral neuropathy pain. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1931–1937. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.16.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mack A. Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin. J Manag Care Pharm. 2003;9:559–568. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.6.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pande AC, Crockatt JG, Janney CA, et al. Gabapentin in bipolar disorder: a placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive therapy. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2:249–255. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2000.20305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frye MA, Ketter TA, Kimbrell TA, et al. A placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:607–614. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200012000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Office of Research Development and Information, Mathematica Policy Research. [Accessed September 28, 2007];The Medicaid Analytic Extract Chartbook. 2007 Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/Downloads/MAX_Chartbook_2007.pdf.

- 23.Nemeroff CB, Kaladi A, Keller MB, et al. Impact of publicity concerning pediatric suicidality data on physician practice patterns in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:466–472. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Unutzer J, Simon G, pabiniak C, et al. The treated prevalence of bipolar disorder in a large staff-model HMO. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:1072–1078. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.8.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Unutzer J, Simon G, Pabiniak C, et al. The use of administrative data to assess quality of care for bipolar disorder in a large staff model HMO. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(99)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Landrum MB. Bipolar-I disorder in a Medicaid population: Correlates of quality of care. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:848–854. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Neelon B, et al. Longitudinal racial/ethnic disparities in antimanic medication use in bipolar-I disorder. Med Care. 2009 doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181adcc4f. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Busch AB, Ling DC, Frank RG, et al. Changes in bipolar-I disorder quality of care during the 1990’s. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:27–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.1.27-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Busch AB, Frank RG, Lehman AF, et al. Co-occurring substance use disorders and quality of care: The differential effect of a managed behavioral health care carve-out. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:388–397. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0045-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Busch AB, Frank RG, Lehman AL. The effect of a managed behavioral health care carve-out on quality of care for Medicaid patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:442–448. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Busch AB, Huskamp HA, Normand S-LT, et al. The impact of parity on major depression treatment quality on the federal employees’ health benefits program after parity implementation. Med Care. 2006;44:506–512. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215890.30756.b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busch AB, Lehman AF, Goldman HH, et al. Changes over time and disparities in schizophrenia treatment quality. Med Care. 2009;44:199–207. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818475b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank RG, Berndt ER, Busch AB, et al. Quality constant “prices” for the ognoing treatment of schizophrenia: An exploratory study. Q Rev Econ Finance. 2004;44:390–409. doi: 10.1016/j.qref.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellis ER, Smith VK, Rousseau DM. Medicaid enrollment in 50 states: June 2004 data update. Washington D.C: The Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeger SL, Liang K-Y. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manchanda P, Honka E. The effects and role of direct-to-physician marketing in teh pharmaceutical industry: An integrative review. Yale Journal of Health Policy, Law, and Ethics. 2005;5:785–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steinman M, Harper GM, Chren M-M, et al. Characteristics and impact of drug detailing for gabapentin. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040134. doi:110.1371/journal.pmed.0040134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Small JG, Klapper MH, Milstein V, et al. Carbamazepine compared with lithium in the treatment of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:915–921. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810340047006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Freeman TW, Clothier JL, Pazzaglia P, et al. A double-blind comparison of balproate and lithium in the treatment of acute mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:108–111. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-Depressive Illness. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss RD, Greenfield SF, Najavits LM, et al. Medication compliance among patients with bipolar and substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:172–174. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scott J, Pope M. Nonadherence with mood stabilizers: prevalence and predictors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:384–390. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision) Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tohen M, Jacobs TG, Grundy SL, et al. Efficacy of olanzapine in acute bipolar mania: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:841–849. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.9.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs GS, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in outpatients with bipolar I depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:79–88. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khanna S, Vieta E, Lyons B, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of acute mania: Double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:229–234. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bowden CL, Grunze H, Mullen J, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study of quetiapine or lithium as monotherapy for mania in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:111–121. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Libby AM, Brent DA, Morrato EH, et al. Decline in treatment of pediatric depression after FDA advisory on risk of suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:884–891. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Libby AM, Orton HD, Valuck RJ. Persisting decline in depression treatment after FDA warnings. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:633–639. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice; effective implementation of change in patient’s care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–1230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weiss AP. Measuring the impact of medical research: moving from outputs to outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:206–214. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, et al. No magic bullets: A systematic review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ. 1995;153:1423–1431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shaneyfelt M. Building bridges to quality. JAMA. 2001;286:2600–2601. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bauer M. A review of quantitative studies of adherence to mental health clinical practice guidelines. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002;10:138–153. doi: 10.1080/10673220216217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soumerai SB. Benefits and risks of increasing restriction on access to costly drugs in Medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23:135–146. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosenthal MB, Berndt ER, Donohue JM, et al. Promotion of prescription drugs to consumers. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:498–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]