Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the incidence, natural history, and risk factors predictive of CNS relapse in patients with de novo aggressive lymphomas and to evaluate the efficacy of CNS prophylaxis in patients with initial bone marrow (BM) involvement.

Patients and Methods

We conducted an analysis of CNS events from 20-year follow-up data on 899 eligible patients with aggressive lymphoma treated on Southwest Oncology Group protocol 8516, a randomized trial of CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), MACOP-B (methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin), ProMACE (prednisone, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide)-CytaBOM (cytarabine, bleomycin, vincristine, methotrexate), and m-BACOD (methotrexate, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide). Patients with BM involvement randomly assigned to receive ProMACE-CytaBOM (63 patients) or m-BACOD (58 patients) were to receive CNS prophylaxis, whereas those randomly assigned to receive CHOP or MACOP-B did not.

Results

CNS relapse is uncommon (25 of 899 patients), with a cumulative incidence of 2.8%. CNS relapse occurs early (median time to relapse, 5.4 months from diagnosis). Indeed, 20 of 25 patients with CNS relapse relapsed during chemotherapy, or within 6 months of completion. The number of extranodal sites and the International Prognostic Index were predictive of CNS relapse. There was no significant benefit of CNS prophylaxis in patients with BM involvement at diagnosis; however, given the small number of events, the power of this analysis is limited.

Conclusion

The early occurrence of CNS events suggests that these patients had subclinical disease at initial diagnosis. As such, strategies to better detect and treat patients with subclinical CNS disease at diagnosis would be anticipated to result in a decrease in the incidence of CNS relapse, without subjecting those patients not destined for CNS relapse to unnecessary and potentially toxic prophylaxis strategies.

INTRODUCTION

Involvement of the CNS with lymphoma was reported back in the 1940s.1 It was not until the 1960 to 1970s, however, when chemotherapeutic advances resulted in cures for patients with aggressive lymphomas, that many began to address the problem of CNS relapse.2-5 Early studies showed that patients with Burkitt's and lymphoblastic lymphomas had a high risk of CNS involvement, and over the years, effective CNS prophylaxis strategies for these diseases were developed. It was also shown that patients having diffuse large-cell lymphomas (DLCL) were at increased risk of CNS relapse if they had extranodal disease.2-4 In particular, patients with bone marrow (BM) involvement were found to have a high risk of developing leptomeningeal disease.2 The recommendation based on many early studies was to administer CNS prophylaxis to patients with BM involvement, the practice of which is continued by many today.

In an attempt to decrease the CNS relapse rate in diffuse aggressive lymphoma, several of the second and third generation regimens incorporated CNS prophylaxis into their treatment. For example, the National Cancer Institute ProMACE (prednisone, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide)-CytaBOM (cytarabine, bleomycin, vincristine, methotrexate) regimen included 24 Gy prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with bone or BM involvement.6 The Vancouver MACOP-B (methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin) regimen included intrathecal chemotherapy for those with initial BM involvement.7 In contrast, the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) and Dana-Farber m-BACOD (methotrexate, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide) regimens did not include CNS prophylaxis.8,9

From 1986 to 1991, SWOG conducted a prospective randomized trial whereby patients with de novo aggressive lymphoma were randomly assigned to receive one of four treatments including ProMACE-CytaBOM, MACOP-B, CHOP and m-BACOD (SWOG 8516).8 To better delineate the incidence, natural history, and risk factors predictive of CNS relapse, we performed a 20-year follow-up analysis of SWOG 8516 with a particular focus on CNS events.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and Treatment

Between 1986 and 1991, 899 eligible patients were enrolled onto SWOG 8516, a randomized trial for patients with de novo, advanced-stage aggressive lymphomas, defined as any intermediate- or high-grade lymphoma, other than lymphoblastic lymphoma (working formulation groups D through H and group J).8 There were no age restrictions. A pretreatment CSF evaluation was not required. Patients were randomly assigned to receive CHOP, MACOP-B, ProMACE-CytaBOM, or m-BACOD, administered as described in the original reports of these regimens.6-9 Patients receiving ProMACE-CytaBOM, who were BM positive at diagnosis, and who achieved a BM remission after cycle 4, were to receive 24 Gy of whole-brain irradiation. Patients receiving m-BACOD who were BM positive at diagnosis and who achieved a BM remission were to receive intrathecal methotrexate (12 mg) and cytarabine (30 mg) twice weekly for six doses. Patients receiving either CHOP or MACOP-B received no CNS prophylaxis. Randomization was stratified according to BM infiltration (present or absent); bulky disease (present or absent), lactate dehydrogenase concentration (≤ 250 v > 250 U/L), and working formulation group (group D or E v F, G, or H v J). The initial results of this study were previously published.8

Definition of CNS Relapse

CNS relapse was defined as leptomeningeal, brain parenchymal, or intradural involvement with lymphoma, as documented by pathologic, radiologic and/or clinical criteria. Patients with epidural or vertebral body involvement were not classified as having CNS relapse.

Statistical Analysis

A total of 899 patients were analyzed. Progression/relapse was defined as documented progression of lymphoma or death resulting from any cause. Ten-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) estimates were derived according to the Kaplan-Meier method.10 Multivariate modeling of survival was performed using Cox regression.10 Type of relapse was defined as relapse at first progression, including nodal or extranodal, with CNS relapse defined as described earlier herein. Multivariate modeling of the proportion of patients experiencing CNS relapse by a given factor was performed using logistic regression. Nonparametric estimates of cumulative incidence were calculated.11 The statistical significance of differences in relative cumulative incidence at a given time point were computed using permutation sampling.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Survival

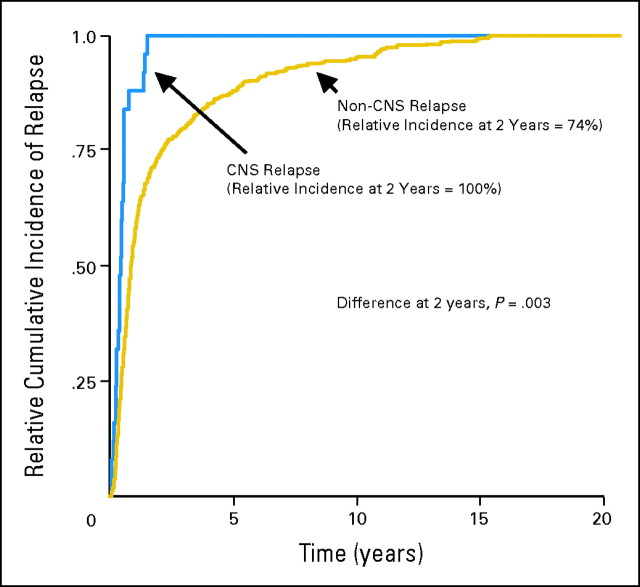

A total of 899 eligible patients were randomly assigned to receive either CHOP (n = 225; 25%), MACOP-B (n = 218; 24%), ProMACE-CytaBOM (n = 233; 26%), or m-BACOD (n = 223; 25%). Patient characteristics by treatment are outlined in Table 1, with no statistically significant differences seen between arms. With 20 years follow-up, there remained no significant differences in either PFS or OS among the four treatment arms. Specifically, for CHOP, m-BACOD, ProMACE-CytaBOM, and MACOP-B, the 10-year estimate of PFS (Fig 1A) was 25%, 31%, 27%, and 26%, respectively, and of OS (Fig 1B) was 34%, 35%, 37%, and 32%, respectively. Adjusting for International Prognostic Index (IPI), there was no evidence of any overall effect of treatment on PFS (P = .22), or OS (P = .81).12

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Arm

| Factor | Treatment Arm (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHOP (n = 225) | MACOP-B (n = 218) | ProMACE-CytaBOM (n = 233) | m-BACOD (n = 223) | ||||

| Age > 60 years | 43 | 42 | 38 | 43 | |||

| Stage III or IV | 85 | 83 | 85 | 83 | |||

| Performance status ≥ 2 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 6 | |||

| LDH > ULN | 65 | 63 | 68 | 64 | |||

| > 1 extranodal site | 36 | 38 | 32 | 35 | |||

| IPI risk | |||||||

| Low | 18 | 24 | 21 | 22 | |||

| Low-intermediate | 39 | 31 | 37 | 37 | |||

| High-intermediate | 32 | 32 | 29 | 27 | |||

| High | 10 | 13 | 12 | 14 | |||

| Bone marrow involvement | 24 | 24 | 26 | 25 | |||

Abbreviations: CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; MACOP-B, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin; ProMACE, prednisone, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide; CytaBOM, cytarabine, bleomycin, vincristine, methotrexate; m-BACOD, methotrexate, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, institutional upper limit of normal; IPI, International Prognostic Index.

Fig 1.

(A) Progression-free and (B) overall survival by treatment arm in Southwest Oncology Group protocol 8516. CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; MACOP-B, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin; ProMACE, prednisone, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide; CytaBOM, cytarabine, bleomycin, vincristine, methotrexate; m-BACOD, methotrexate, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide.

Patterns of Relapse

Among the 899 patients, 515 had documented relapse, with 348 (68%) presenting with nodal relapse alone and 167 presenting with evidence of extranodal relapse (33 of which relapsed in multiple sites). CNS relapse was an uncommon event, found in 25 of 899 patients with a cumulative incidence over time of 2.8%. In comparison, the cumulative incidence over time of non-CNS relapse was 55%.

Temporal Relationship of CNS Relapse and Chemotherapy

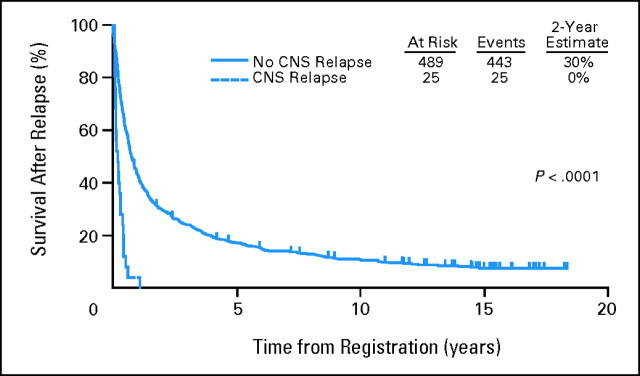

Patients with CNS relapse recurred earlier than patients with non-CNS relapse. Figure 2 illustrates the cumulative incidence of CNS relapse over time relative to the maximum cumulative incidence of relapse at all sites over time. One hundred percent of CNS relapses occurred by year 2, compared with 74% of non-CNS relapses (P = .003). The median time from diagnosis to CNS relapse was 5.4 months (range, 0.6 to 18.3 months).

Fig 2.

Cumulative incidence of relapse relative to the maximum cumulative incidence in Southwest Oncology Group protocol 8516.

The time to CNS relapse in relation to when patients received chemotherapy, and whether such patients were responding systemically at the time of CNS relapse was next determined. Thirteen of the 25 patients with CNS relapse developed CNS disease during chemotherapy. Of these, nine were responding systemically, two were progressing, and two were not assessed for systemic progression. Three of the 25 patients with CNS relapse developed CNS disease within 1 month of chemotherapy completion, (all responding systemically); the remaining four, two, and three patients developed CNS disease 2 to 3 months, 4 to 6 months, and more than 9 months after chemotherapy was completed, respectively (all responding systemically at the time of CNS disease except for one patient whose systemic disease was not assessed). There were no patients who had a CNS relapse more than 13 months after completion of chemotherapy.

Characteristics of CNS-Relapsed Patients

Of the 25 patients with CNS relapse, 11 had isolated CNS relapse and 10 had systemic progression at any time from diagnosis of CNS disease until death; in four patients, systemic disease was never assessed.

Twenty-one of the 25 patients with CNS relapse had leptomeningeal disease; of these, 14 had no evidence of brain parenchymal disease and two had concomitant brain parenchymal disease. The brain was not assessed in five patients. Three patients had brain parenchymal disease without assessment of the CSF, and one patient had intradural disease.

Prognosis of CNS-Relapsed Patients

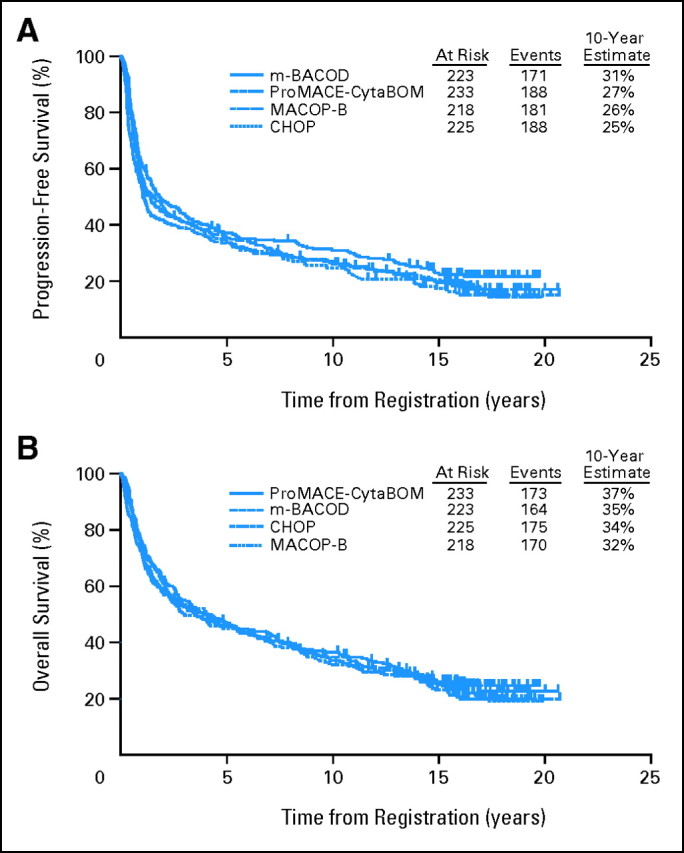

Patients with CNS relapse had a poor outcome (median survival after relapse, 2.2 months compared with 9 months for non–CNS-relapsed patients). Two-year estimates of survival after relapse were 30% for the non–CNS-relapsed patients and 0% for CNS relapsed patients (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Survival after relapse in Southwest Oncology Group protocol 8516.

Risk Factors for CNS Relapse

There were no differences in CNS relapse rate by treatment group (CHOP, 4.4%; m-BACOD, 2.2%; ProMACE-CytaBOM, 3.0%; and MACOP-B, 1.4%; P = .77). Observed CNS relapse rates were higher in the adverse group for each of the five IPI factors (Table 2). Adjusted for treatment, statistically significant differences were evident in patients with more than one extranodal site (4.4% v 1.9%; P = .03) and in patients with higher IPI scores (4.2% v 1.7%; P = .03; Table 2). A test for trend in the CNS relapse rates by individual IPI category found a highly significant effect of risk level, with CNS relapse rates of 0.5%, 2.5%, 3.7%, and 5.4% in low, low-intermediate, high-intermediate, and high IPI, respectively (P = .007). There were no differences in CNS relapse rates by treatment arm or bone marrow status (Table 3).

Table 2.

CNS Relapse Rates by Baseline Factors, Adjusted for Treatment (n = 25)

| Factor | CNS Relapse (%) | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 1.85 | 0.83 to 4.14 | .13 | |

| > 60 | 3.8 | |||

| ≤ 60 | 2.1 | |||

| Stage | 4.51 | 0.60 to 33.6 | .14 | |

| III or IV | 3.2 | |||

| Bulky II | 0.7 | |||

| Performance status | 1.34 | 0.60 to 2.99 | .48 | |

| ≥ 2 | 5.8 | |||

| < 2 | 2.6 | |||

| LDH | 1.37 | 0.56 to 3.31 | .49 | |

| > ULN | 3.1 | |||

| ≤ ULN | 2.2 | |||

| No. of extranodal sites | 2.46 | 1.10 to 5.49 | .03 | |

| > 1 | 4.4 | |||

| ≤ 1 | 1.9 | |||

| IPI risk | 2.50 | 1.09 to 5.74 | .03 | |

| High or high/intermediate | 4.2 | |||

| Low or low/intermediate | 1.7 |

Abbreviations: LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, institutional upper limit of normal; IPI, International Prognostic Index.

Table 3.

CNS Relapse Rates

| Factor | No. of CNS Cases |

CNS Relapse Rate (%) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numerator | Denominator | ||||

| All patients | 25 | 899 | 2.8 | ||

| Treatment arm | .24 | ||||

| CHOP | 10 | 225 | 4.4 | ||

| m-BACOD | 5 | 223 | 2.2 | ||

| ProMACE-CytaBOM | 7 | 233 | 3.0 | ||

| MACOP-B | 3 | 218 | 1.4 | ||

| Bone marrow status | .53 | ||||

| Negative | 17 | 661 | 2.6 | ||

| Positive | 8 | 238 | 3.4 | ||

| Receipt of CNS prophylaxis* | |||||

| Yes | 2 | 72 | 2.8 | .74 | |

| No | 6 | 166 | 3.6 | ||

| CNS prophylaxis strategy* | |||||

| Yes | 3 | 121 | 2.5 | .44 | |

| No | 5 | 117 | 4.3 | ||

Abbreviations: CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; m-BACOD, methotrexate, bleomycin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide; ProMACE, prednisone, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide; CytaBOM, cytarabine, bleomycin, vincristine, methotrexate; MACOP-B, methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and bleomycin.

Analysis of CNS prophylaxis strategy and receipt of CNS prophylaxis was restricted to the bone marrow positive cases (n = 238) only, per protocol specifications that only those patients are eligible to receive CNS prophylaxis.

Efficacy of CNS Prophylaxis

The data set was restricted to the 238 patients who had BM involvement at the time of diagnosis. The outcome based on the patients who actually received prophylaxis was analyzed first. Of the 58 patients in the m-BACOD group with BM disease at diagnosis, 34 patients (59%) actually received at least one dose of intrathecal therapy. Of the 34 patients who received intrathecal therapy, 68% received five or six of the planned six doses of intrathecal therapy. Of the 63 patients in the ProMACE-CytaBOM group with BM involvement at diagnosis, 38 (60%) actually received cranial radiation. The most common reason for not receiving intrathecal therapy or cranial irradiation was failure to obtain a BM remission. Overall, the CNS relapse rates were 2.8% for the patients who received prophylaxis and 3.6% for the patients who did not receive prophylaxis (P = .74; Table 3). Given that CNS prophylaxis was administered only in the bone marrow remission cases, the postrandomization comparison just outlined is likely biased in favor of prophylaxis (ie, would expect lower CNS relapse in the prophylaxis group). Despite this, the estimated rates are not statistically different.

Because postrandomization selection biases relate to both the probability of getting prophylaxis (ie, remission response) and to the outcome (CNS relapse), an alternative analysis would be to compare the strategy of prophylaxis within the baseline BM-positive group. This approach would represent an intention-to-treat analysis. The rate of CNS relapse in the prophylaxis strategy group was 2.5% and in the nonstrategy group was 4.3% (P = .44; Table 3). Taken together, both of these analyses show no statistically significant benefit of CNS prophylaxis in patients who are BM positive at the time of diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

CNS relapse is an uncommon event for patients with aggressive lymphoma, with a cumulative incidence of 2.8% in our study. Indeed, the incidence of CNS relapse in other series of chemotherapy-treated patients with aggressive lymphomas ranges from 1.6% to 5%, with differences in patient populations, treatment regimens (including in some cases the use of CNS prophylaxis), and in how CNS relapse is defined likely accounting for the variability in incidence among these studies.13-17 All of these studies, including ours, were in the pre-rituximab era, and given that rituximab in combination with CHOP-like chemotherapy is now a standard of care for patients with DLCL, a critical question is whether rituximab decreases the rate of CNS relapse.18 An analysis of the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte (GELA) study, in which 399 elderly patients with DLCL were treated with eight cycles of CHOP, with or without rituximab, demonstrated no effect of rituximab on the risk of CNS recurrence.19 In contrast, a recent preliminary analysis of CNS events in the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group trials of CHOP-14 with or without rituximab suggested that rituximab decreased the risk of CNS recurrence.20

What is striking about CNS recurrences is that when they occur, they occur early (median time to a CNS event in the present study, 5.4 months from initial diagnosis). Indeed, a majority of the patients who had a CNS event presented with such an event during their initial chemotherapy. Similar findings have been reported in other series.13,17 For example, the median time to CNS recurrence in the study of van Besien et al13 was 6 months, with only one patient experiencing recurrence more then 13 months after initial diagnosis. Furthermore, in our study, almost all CNS events occurred at a time when the patient was responding systemically. Taken together, these data strongly suggests that such patients likely had subclinical CNS disease at diagnosis.

In our study, patients with more than one extranodal site had a significantly higher rate of CNS relapse compared with those with one or fewer extranodal sites of involvement, a risk factor that is predictive of CNS relapse in multiple studies.13-16 Indeed, as the interplay of adhesion molecules and chemokine receptors on lymphocytes with their ligands in the microenvironment regulate normal lymphocyte trafficking, recent work suggests that lymphoma dissemination is regulated by the same physiologic processes.21 As such, it is possible that there are lymphomas destined to disseminate to multiple extranodal sites that includes the CNS. That the IPI score is highly predictive of CNS relapse in our series suggests that additional factors which predict for an overall poor prognosis for patients with diffuse lymphomas may also be predictive for CNS relapse.

Because BM involvement has previously been described as a risk factor for CNS relapse, it has often been recommended that patients with BM involvement receive CNS prophylaxis.2 The design of SWOG 8516, whereby patients are first stratified according to presence or absence of BM involvement, and then randomly assigned to one of four treatment arms, two of which require CNS prophylaxis and two of which do not, allows us to calculate whether CNS prophylaxis for such patients is of benefit.8 We analyzed these using two approaches. First we evaluated the incidence of CNS events in the patients who actually received CNS prophylaxis. Such patients, by definition, must have achieved a BM remission to receive prophylaxis, and as such, might be considered a favorable group. Further, because CNS relapses tend to happen earlier than non-CNS relapses, this selection pattern could potentially bias the analysis in favor of prophylaxis. Therefore, we also evaluated the incidence of CNS events among all patients with BM involvement who were therefore initially eligible for prophylaxis, representing an intention-to-treat analysis. Neither analysis showed any evidence of a beneficial effect of CNS prophylaxis for patients with BM involvement.

As discussed, our findings that most cases of CNS relapse occurred during, or shortly after, completion of chemotherapy suggests that such patients likely had subclinical CNS disease at diagnosis. A corollary of this hypothesis is that if we had a more sensitive marker of subclinical disease than classical cytology, many of such patients would be identified at diagnosis and would then be treated, rather then administered prophylaxis, for CNS disease.

In this regard, Hegde et al22 examined the CSF by cytology and flow cytometry in a select group of patients thought to be at high risk for CNS involvement: patients with AIDS-related and Burkitt's lymphomas, as well as high-risk DLCL. Eleven patients had flow cytometric evidence of CSF lymphoma with only one such patient having positive cytology, demonstrating that flow cytometry is more sensitive than cytology in detecting CSF lymphoma. The incidence of overt CNS relapse was 45% in the flow-positive group compared with 8% in the flow-negative group, suggesting that detection of subclinical CSF lymphoma by flow cytometry is associated with a high risk of developing overt CNS disease.22 What is concerning, however, was that overt CNS disease developed in five of nine patients with flow-positive CSF treated aggressively with a prolonged course of intrathecal or intraventricular methotrexate (cytarabine and/or cranial radiation were used as clinically indicated in patients not responding to intrathecal/ventricular therapy).22 This suggests that a positive CSF at diagnosis by flow cytometry is a sensitive marker of occult CNS disease; however, the optimal treatment approach for such patients is not known.

Insight into a possible approach for patients with subclinical CSF involvement is suggested from a study by Tilly et al17 whereby elderly patients with aggressive lymphoma with one or more poor prognostic IPI factors were randomly assigned to receive either ACVBP (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone; which included both high-dose systemic methotrexate [3 gm/m2] and intrathecal methotrexate) or CHOP (no CNS prophylaxis). Nine CNS events were seen in the ACVBP group compared with 26 events in the CHOP group (P = .004).17 These data suggest that high-dose systemic methotrexate and intrathecal methotrexate may have benefit for patients destined for CNS relapse. It is noteworthy that in the study by Tilly et al, similar to that found in our study, six of nine and 21 of 26 patients with CNS progression who received either ACVBP or CHOP, respectively, progressed in the CNS during chemotherapy treatment.17

Limitations to our analysis exist. First, the CNS prophylaxis in ProMACE-CytaBOM may not have been optimal. Patients were treated with cranial radiation alone. As the dose of methotrexate given in this regimen (120 mg/m2) was considered at the time to be high-dose, no intrathecal methotrexate was given.6 More recently however, clinicians have been using methotrexate doses greater than 1 gm/m2 for CNS penetration. Secondly, the number of patients having CNS events is small, and as such, the power of our analysis is limited. For example, the power to detect a change from 5% to 2% is 60% with a type 2 error of 40%. Finally, this study was not originally designed to test the efficacy of CNS prophylaxis but rather to prospectively compare the outcome of four established regimens, administered as originally published, two of which included CNS prophylaxis.

In summary, our study clearly demonstrates that CNS events occur early in the treatment of patients with aggressive NHL, suggesting that such patients have subclinical CSF involvement at diagnosis. These data strongly support the recommendation that routine evaluation of the CSF at diagnosis be performed in patients at high risk for CNS relapse, such as patients with a high-intermediate or high-risk IPI score and/or those with at least one extranodal site of involvement. Although we found no benefit of CNS prophylaxis for patients with BM evaluation, the small number of CNS events in this study limits the power of this analysis. These data do, however, bring into question the efficacy of CNS prophylaxis and further suggests that the paradigm should perhaps shift away from CNS prophylaxis to one of better detection of subclinical CNS involvement at diagnosis, such as using flow cytometry, and to developing better treatment strategies for patients with subclinical CNS involvement. We anticipate that such a paradigm, which needs to be tested in the context of prospective clinical trials, would result in a decrease in the incidence of CNS relapse without subjecting a large number of patients to unnecessary prophylaxiss.

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Steven H. Bernstein, Joseph M. Unger, Michael LeBlanc, Jonathan Friedberg, Thomas P. Miller, Richard I. Fisher

Administrative support: Richard I. Fisher

Provision of study materials or patients: Thomas P. Miller, Richard I. Fisher

Collection and assembly of data: Steven H. Bernstein, Joseph M. Unger, Michael LeBlanc, Jonathan Friedberg, Richard I. Fisher

Data analysis and interpretation: Steven H. Bernstein, Joseph M. Unger, Michael LeBlanc, Jonathan Friedberg, Richard I. Fisher

Manuscript writing: Steven H. Bernstein, Joseph M. Unger, Michael LeBlanc, Jonathan Friedberg, Thomas P. Miller, Richard I. Fisher

Final approval of manuscript: Steven H. Bernstein, Joseph M. Unger, Michael LeBlanc, Jonathan Friedberg, Thomas P. Miller, Richard I. Fisher

Footnotes

published online ahead of print at www.jco.org on December 1, 2008.

Presented in part at the 49th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology, December 8-11, 2007, Atlanta, GA.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sparling HJ, Adams R, Parker F Jr: Involvement of the nervous system by malignant lymphoma. Medicine 26:285-332, 1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunn PA Jr, Schein PS, Banks PM, et al: Central nervous system complications in patients with diffuse histiocytic and undifferentiated lymphoma: Leukemia revisited. Blood 47:3-10, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litam JP, Cabanillas F, Smith TL, et al: Central nervous system relapse in malignant lymphomas: Risk factors and implications for prophylaxis. Blood 54:1249-1257, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herman TS, Hammond N, Jones SE, et al: Involvement of the central nervous system by non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: The Southwest Oncology Group experience. Cancer 43:390-397, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law IP, Dick FR, Blom J, et al: Involvement of the central nervous system in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer 36:225-231, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longo DL, DeVita VT Jr, Duffey PL, et al: Superiority of ProMACE-CytaBOM over ProMACE-MOPP in the treatment of advanced diffuse aggressive lymphoma: Results of a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 9:25-38, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klimo P, Connors JM: MACOP-B chemotherapy for the treatment of diffuse large-cell lymphoma. Ann Intern Med 102:596-602, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, et al: Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with three intensive chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 328:1002-1006, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shipp MA, Harrington DP, Klatt MM, et al: Identification of major prognostic subgroups of patients with large-cell lymphoma treated with m-BACOD or M-BACOD. Ann Intern Med 104:757-765, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox D: Regression models and life tables. J Royal Stat Soc 34:187-220, 1972 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice R: Non-parametric estimates of cumulative incidence were calculated, in The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York, John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1980

- 12.A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: The International Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. N Engl J Med 329:987-994, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Besien K, Ha CS, Murphy S, et al: Risk factors, treatment, and outcome of central nervous system recurrence in adults with intermediate-grade and immunoblastic lymphoma. Blood 91:1178-1184, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollender A, Kvaloy S, Nome O, et al: Central nervous system involvement following diagnosis of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A risk model. Ann Oncol 13:1099-1107, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haioun C, Besson C, Lepage E, et al: Incidence and risk factors of central nervous system relapse in histologically aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma uniformly treated and receiving intrathecal central nervous system prophylaxis: A GELA study on 974 patients—Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Ann Oncol 11:685-690, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boehme V, Zeynalova S, Kloess M, et al: Incidence and risk factors of central nervous system recurrence in aggressive lymphoma: A survey of 1693 patients treated in protocols of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Ann Oncol 18:149-157, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tilly H, Lepage E, Coiffier B, et al: Intensive conventional chemotherapy (ACVBP regimen) compared with standard CHOP for poor-prognosis aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 102:4284-4289, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al: CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 346:235-242, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feugier P, Virion JM, Tilly H, et al: Incidence and risk factors for central nervous system occurrence in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: Influence of rituximab. Ann Oncol 15:129-133, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boehme V, Zeynalova S, Lengfelder E, et al: CNS-disease in elderly patients treated with modern chemotherapy (CHOP-14) with or without rituximab: An analysis of CNS events in the RICOVER-60 Trial of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Blood 110, 2007. (abstr 519) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Pals ST, de Gorter DJ, Spaargaren M: Lymphoma dissemination: The other face of lymphocyte homing. Blood 110:3102-3111, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hegde U, Filie A, Little RF, et al: High incidence of occult leptomeningeal disease detected by flow cytometry in newly diagnosed aggressive B-cell lymphomas at risk for central nervous system involvement: The role of flow cytometry versus cytology. Blood 105:496-502, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]