Abstract

Purpose

Cerebrovascular disease is common in head and neck cancer patients, but it is unknown whether radiotherapy increases the cerebrovascular disease risk in this population.

Patients and Methods

We identified 6,862 patients (age > 65 years) from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) –Medicare cohort diagnosed with nonmetastatic head and neck cancer between 1992 and 2002. Using proportional hazards regression, we compared risk of cerebrovascular events (stroke, carotid revascularization, or stroke death) after treatment with radiotherapy alone, surgery plus radiotherapy, or surgery alone. To further validate whether treatment groups had equivalent baseline risk of vascular disease, we compared the risks of developing a control diagnosis, cardiac events (myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft, or cardiac death). Unlike cerebrovascular risk, no difference in cardiac risk was hypothesized.

Results

Mean age was 76 ± 7 years. Ten-year incidence of cerebrovascular events was 34% in patients treated with radiotherapy alone compared with 25% in patients treated with surgery plus radiotherapy and 26% in patients treated with surgery alone (P < .001). After adjusting for covariates, patients treated with radiotherapy alone had increased cerebrovascular risk compared with surgery plus radiotherapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.42; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.77) and surgery alone (HR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.18 to 1.90). However, no difference was found for surgery plus radiotherapy versus surgery alone (P = .60). As expected, patients treated with radiotherapy alone had no increased cardiac risk compared with the other treatment groups (P = .63 and P = .81).

Conclusion

Definitive radiotherapy for head and neck cancer, but not postoperative radiotherapy, was associated with excess cerebrovascular disease risk in older patients.

INTRODUCTION

In various cancer populations, radiotherapy is associated with development of vascular disease.1-3 For example, radiotherapy in Hodgkin's disease patients is associated with significantly increased risk of cerebrovascular and cardiac events 10 or more years after treatment.1 In addition, radiotherapy in breast cancer patients treated in earlier eras has been associated with a higher risk of cardiac-related death.2,3

Previous single-institution studies suggest that head and neck cancer patients who undergo radiotherapy have higher incidence of carotid stenosis and stroke compared with controls in the general population.4,5 However, these studies have not definitively established the independent contribution of radiotherapy to cerebrovascular disease risk because analyses have not compared head and neck cancer patients who underwent radiotherapy with patients did not undergo radiotherapy. Therefore, it remains unknown whether the high cerebrovascular event rate observed in head and neck cancer patients represents long-term treatment toxicity or merely reflects the increased prevalence of traditional risk factors in this population, such as history of smoking and male sex.

Establishing the effect of radiotherapy on cerebrovascular risk in head and neck cancer patients is important for helping to define the role of screening for vascular disease and secondary prevention of stroke in this high-risk group. In addition, determining risks associated with radiotherapy is important for identifying whether newer treatment techniques, such as more conformal techniques, alternative fractionation schemes, or use of radioprotective agents, could potentially modify cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality.

We sought to determine the incidence of cerebrovascular events in a cohort of older head and neck cancer patients identified through the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) –Medicare database. We compared the risk of developing cerebrovascular events in patients who underwent radiotherapy alone (more likely to receive higher radiation doses to the carotid),6 surgery plus radiotherapy (more likely to receive slightly lower radiation doses),7,8 or surgery alone (no radiation). Given that treatment fields in head and neck cancer patients typically spare coronary vessels and other cardiac structures, we additionally compared the risk of developing a validating control diagnosis, cardiac events. We hypothesized that radiotherapy to the neck would increase cerebrovascular risk but not affect cardiac risk.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

SEER-Medicare Cohort

The SEER-Medicare database includes a population-based cohort of Medicare beneficiaries with incident cancer identified through SEER tumor registries. Until 1999, SEER included 11 registries, accounting for 14% of the US population; in 2000, the program included an additional five registries, accounting for 26% of the US population.9

Study Sample and Exclusions

The study population included 40,200 participants with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision diagnosis of head and neck cancer (diagnosis codes 142, 144 to 149, 160, 190, 193, or 194) from 1986 to 2002 identified in SEER-Medicare records. Tumors of the larynx were not included based on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code screening criteria. From our study population, we derived a sample of 6,862 patients based on pathologic and clinical exclusion criteria (Appendix, online only).

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was development of cerebrovascular events, including stroke, carotid revascularization, or stroke death. Patients hospitalized for stroke or transient ischemic attack were identified based on Medicare Part A and B claims in the SEER-Medicare linked database, and stroke (cerebrovascular) deaths were identified from the SEER-Medicare cause of death data. All claims codes are listed in the Appendix. This algorithm for identifying cerebrovascular events is a modified combination of algorithms used in prior studies with high sensitivity and specificity for identifying events.3,10 Time to event was calculated from date of cancer diagnosis.

Our secondary, validating outcome was development of cardiac events, including hospitalization for myocardial infarction, percutaneous coronary intervention, or coronary artery bypass graft (based on Medicare Part A and B claims) or cardiac death (based on SEER-Medicare cause of death). This algorithm for identifying cardiac events is modified from prior studies of SEER-Medicare patients.2,11 Because an increased risk of cerebrovascular but not cardiac events was expected, this validating control diagnosis was designed to help exclude the possibility of residual confounding in the association between radiotherapy and cerebrovascular events.

Treatments

We determined radiotherapy and/or surgery treatment using SEER records and Medicare claims (Appendix). Patients were categorized as undergoing cancer-directed surgery (total or partial tumor resection) or not undergoing cancer-directed surgery (including biopsy alone). Patients were considered to have undergone radiotherapy and/or surgery treatments if a claim was recorded within 9 months of cancer diagnosis. In addition, sensitivity analyses were conducted using claims within 6 and 4 months of diagnosis.

We compared outcomes for patients who underwent radiotherapy alone, surgery plus radiotherapy, or surgery alone. The two radiotherapy groups were analyzed separately to account for the likelihood that patients who undergo radiotherapy alone may receive higher radiation doses (and higher dose to the carotid) than patients undergoing postoperative radiotherapy.6-8 We also present combined outcomes for patients who underwent any radiotherapy (radiotherapy alone or radiotherapy plus surgery) versus patients who underwent surgery alone. Finally, we present results for the more restrictive outcome of stroke or stroke death because carotid revascularization is an elective procedure and unmeasured factors affecting selection for this procedure may also influence cancer treatment selection.

For all patients, additional treatment with chemotherapy within 6 months of diagnosis (determined from Medicare claims) and surgical treatment to the neck (determined from Medicare claims and SEER records) were considered covariates. Treatment definitions have been used in previously published studies of SEER-Medicare.12,13

Other Covariates

Patient characteristics including age and race were obtained from SEER records. Severity of comorbid disease was based on a modified Charlson comorbidity score validated in prior studies (0 = no comorbidity, 1 = mild to moderate, and 2 = severe).14 This score combined comorbidities from Medicare claims between 12 months and 1 month before cancer diagnosis. To enhance specificity, patients must have had at least one hospital diagnosis (Part A) claim or at least two outpatient (Part B) claims more than 30 days apart.14 History of stroke and myocardial infarction were considered separate covariates in the primary and validating analyses, respectively. Tumor characteristics included size, extent of disease (level of pretreatment primary tumor invasion into adjacent structures based on clinical and pathologic assessment for each tumor site15), extent of positive lymph nodes, grade, and histology, obtained from SEER records. Socioeconomic characteristics included median income of census tract, urban/rural residence, geographic region, and year of treatment, obtained from SEER records. Number of physician visits (characterizing frequency of patients’ interactions with the health care system) between 12 months and 1 month before cancer diagnosis was determined from Medicare claims.

Statistical Analysis

Bivariate associations between the three treatment groups (radiotherapy only, radiotherapy plus surgery, or surgery only) and covariates were tested using the Pearson χ2 test for categoric variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Incidence of cerebrovascular events in each treatment group was calculated using Kaplan-Meier survival function estimates and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models tested whether associations between treatment groups and risk of cerebrovascular events or risk of cardiac events was significant after adjustment for covariates. Covariate selection was based on clinical significance in prior studies or statistical significance in bivariate analyses. Proportionality assumptions were assessed using log-log complementary plots. In multivariate models, we censored patients who died of other causes (nonstroke death in the primary analysis and noncardiac death in the validation analysis) or were lost to follow-up. Finally, for the primary outcome of cerebrovascular events, we tested the potential modifying effects of covariates selected a priori, including age, sex, race, comorbidity, chemotherapy, tumor sites with higher likelihood of receiving radiotherapy to the bilateral neck (nasopharynx, tonsil, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and pharynx), and number of positive nodes, using interaction terms to determine whether a high-risk patient group could be identified.

Finally, to validate the strength and magnitude of the association between treatment group and cerebrovascular risk, we conducted a subsidiary propensity score analysis using the Mayo Greedy Match algorithm (without replacement) with 1:1 matching.16 Balance of measured variables between treatment groups considered all nontreatment covariates listed earlier (plus chemotherapy), and the propensity score (probability of treatment assignment) was based on a logistic regression model. Cox proportional hazards models estimated treatment effect after accounting for propensity scores, with matched pairs stratified by case-control status. This analysis was intended to account for residual confounding associated with treatment selection.

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and all statistical tests assumed a two-tailed α = .05. The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved use of the SEER-Medicare database.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

In 6,862 patients, the median follow-up time was 2.4 years (interquartile range, 1.4 to 4.4 years). This corresponded to median follow-up time of 3.2 years (range, 2.0 to 5.8 years) for patients who survived and 1.8 years (range, 1.1 to 3.4 years) for patients who died. Mean age of the entire cohort was 76 years (standard deviation, 7 years), 54% were men, and 85% were white. At diagnosis, 57% of patients had localized disease, 42% had primary tumor extension into adjacent regional structures, 54% were node negative, and 77% had squamous histology. The most common tumor sites occurred in the oral cavity and oropharynx. The majority of oral cavity tumors were treated with surgery (alone or plus radiotherapy), whereas most oropharynx tumors were treated with radiotherapy alone (Table 1).

Table 1.

Head and Neck Cancer Sites by Treatment Groups (N = 6,862)

| Site | Total Patients |

% of Patients by Treatment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | RT Alone (n = 1,983) | Surgery + RT (n = 2,823) | Surgery Alone (n = 2,056) | ||||

| Oral cavity | 3,106 | 45 | 16 | 35 | 49 | |||

| Anterior tongue | 1,006 | 15 | 10 | 31 | 58 | |||

| Floor of mouth | 566 | 8 | 15 | 39 | 46 | |||

| Gingiva or buccal mucosa | 1,534 | 22 | 20 | 36 | 44 | |||

| Oropharynx | 1,342 | 20 | 56 | 36 | 8 | |||

| Base of tongue | 604 | 9 | 54 | 36 | 10 | |||

| Tonsil | 569 | 8 | 68 | 27 | 5 | |||

| Other oropharynx | 169 | 2 | 59 | 34 | 8 | |||

| Nasopharynx | 256 | 4 | 79 | 20 | 2 | |||

| Hypopharynx | 576 | 8 | 59 | 37 | 4 | |||

| Nasal cavity and sinus | 496 | 7 | 17 | 59 | 25 | |||

| Salivary gland | 934 | 14 | 6 | 68 | 26 | |||

| Other | 152 | 2 | 45 | 41 | 14 | |||

Abbreviation: RT, radiotherapy.

Treatment Characteristics

Among the entire cohort, 29% of patients underwent radiotherapy alone, 41% underwent surgery plus radiotherapy, and 30% underwent surgery alone. In addition, 18% received chemotherapy. As expected based on standard practice patterns, patients who underwent radiotherapy were more likely to have greater tumor involvement (larger tumors, regionally invasive disease, and positive lymph nodes) and more severe comorbid disease than patients who underwent surgery alone (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics by Treatment Group

| Characteristic | % of Patients |

P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT Alone (n = 1,983) | Surgery + RT (n = 2,823) | Surgery Alone (n = 2,056) | ||||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, years | < .0001 | |||||

| Mean | 75 | 75 | 77 | |||

| SD | 7 | 6 | 7 | |||

| White | 80 | 85 | 89 | < .0001 | ||

| Men | 62 | 57 | 44 | < .0001 | ||

| Tumor characteristics | ||||||

| Extent of disease | < .0001 | |||||

| Localized | 42 | 50 | 80 | |||

| Extends into regional structures | 55 | 48 | 20 | |||

| Unknown | 3 | 2 | < 1 | |||

| Size, cm† | < .0001 | |||||

| < 2 | 14 | 28 | 44 | |||

| 2 to < 4 | 27 | 36 | 22 | |||

| > 4 | 11 | 13 | 5 | |||

| Unknown | 48 | 24 | 28 | |||

| No. of positive nodes | < .0001 | |||||

| None | 41 | 48 | 74 | |||

| 1 ipsilateral, ≤ 3 cm | 10 | 8 | 2 | |||

| 1 ipsilateral, > 3 cm to ≤ 6 cm or bilateral/contralateral ≤ 6 cm | 30 | 29 | 4 | |||

| Any, at least 1 > 6 cm | 2 | 1 | < 1 | |||

| Unknown | 17 | 14 | 20 | |||

| Grade | < .0001 | |||||

| Well differentiated | 8 | 11 | 27 | |||

| Moderately differentiated | 37 | 37 | 40 | |||

| Poorly or undifferentiated | 35 | 36 | 11 | |||

| Unknown | 20 | 16 | 21 | |||

| Squamous histology | 88 | 73 | 73 | |||

| Other clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Charlson comorbidity score | < .0001 | |||||

| None (0) | 57 | 62 | 64 | |||

| Mild to moderate (1) | 22 | 21 | 20 | |||

| Severe (2) | 14 | 10 | 11 | |||

| Unknown | 8 | 7 | 5 | |||

| Other treatment | ||||||

| Chemotherapy | 39 | 14 | 2 | < .0001 | ||

| Socioeconomic variables | ||||||

| Married | 50 | 55 | 47 | |||

| Location of residence | .0004 | |||||

| Large metropolitan area | 62 | 58 | 57 | |||

| Metropolitan area | 25 | 27 | 27 | |||

| Urban area | 6 | 7 | 6 | |||

| Less urban area | 5 | 7 | 8 | |||

| Rural area | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Income, quartile | .15 | |||||

| First (median = $23,419) | 24 | 24 | 23 | |||

| Second (median = $36,513) | 23 | 24 | 23 | |||

| Third (median = $47,377) | 25 | 23 | 23 | |||

| Fourth (median = $76,440) | 28 | 29 | 31 | |||

| No. of doctor visits in past year | .31 | |||||

| Mean | 15 | 14 | 15 | |||

| SD | 14 | 12 | 12 | |||

Abbreviations: RT, radiation therapy; SD, standard deviation.

P values reflect the comparison of the three treatment groups.

Size refers to measurement of greatest diameter, as reported in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database.

Risk of Cerebrovascular Events

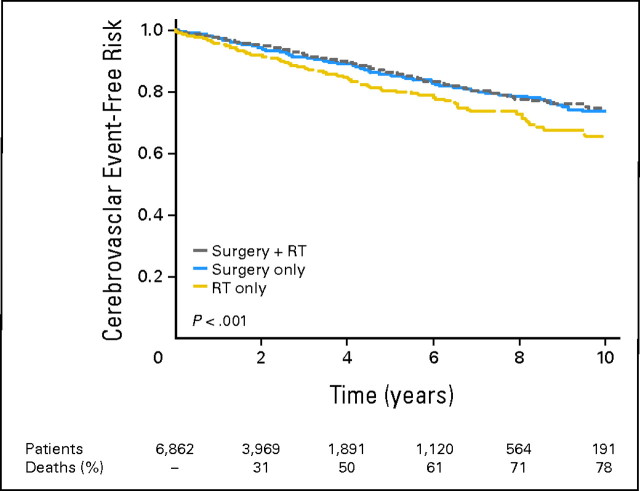

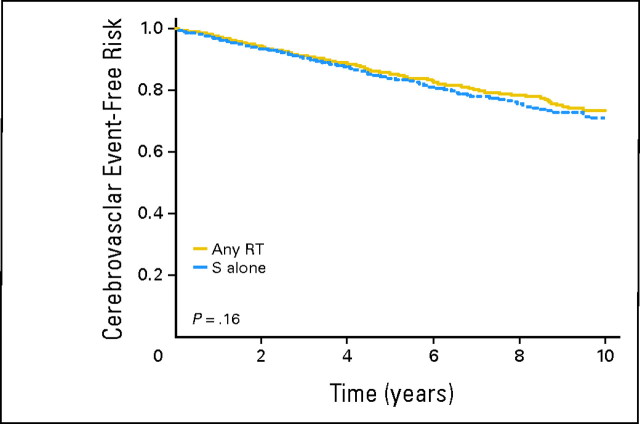

The incidence of events was highest in patients who underwent radiotherapy alone compared with any other treatment group (P < .001). Specifically, by 5 years after diagnosis, actuarial incidence of cerebrovascular events was 19% in patients who underwent radiotherapy alone compared with 14% in patients who underwent surgery plus radiotherapy and 14% in patients who underwent surgery alone; the corresponding actuarial incidences by 10 years after diagnosis were 34%, 25%, and 26%, respectively (Table 3, Fig 1). However, there was no significant difference between incidence of cerebrovascular events in the combined group of patients who underwent any radiotherapy (with or without surgery; 29%) and patients who underwent surgery alone (26%; Appendix Fig A1, online only).

Table 3.

Actuarial Incidence of Cerebrovascular Events by Treatment Group

| Treatment | No. of Events per 1,000 Person-Years | Incidence of Cerebrovascular Events (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Year | 5 Years | 10 Years | ||||

| RT alone | 42.8 | 4 | 19 | 34 | ||

| Surgery + RT | 28.0 | 3 | 14 | 25 | ||

| Any RT | 33.6 | 3 | 16 | 29 | ||

| Surgery alone | 30.7 | 3 | 14 | 26 | ||

NOTE. P values were as follows: RT alone v surgery + RT, P < .001; RT alone v surgery alone, P < .001; surgery + RT v surgery alone, P = .56; and any RT v surgery alone, P = .20.

Abbreviation: RT, radiotherapy.

Fig 1.

Cerebrovascular event-free risk over time by treatment groups. RT, radiotherapy.

On multivariate analysis, patients who underwent radiotherapy alone again had significantly higher risk of developing a cerebrovascular event than did those who underwent surgery plus radiotherapy (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.42; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.77) and those who underwent surgery alone (HR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.18 to 1.90; Table 4). The combined group of patients who underwent any radiotherapy (with or without surgery) were not at significantly higher risk for a cerebrovascular event compared with patients treated with surgery alone (HR = 1.17; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.41). The interaction term between any radiotherapy and surgery was significant (P = .002). No other factors modifying this association were identified, including positive lymph nodes or tumor sites more likely to receive bilateral neck radiotherapy (Appendix Table A1, online only).

Table 4.

Adjusted Risk of Cerebrovascular and Cardiac Events by Treatment Group

| Comparison of treatment groups* | HR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk of cerebrovascular events | |||

| RT alone v surgery + RT | 1.42 | 1.14 to 1.77 | .002 |

| RT alone v surgery alone† | 1.50 | 1.18 to 1.90 | .0009 |

| Any RT v surgery alone | 1.17 | 0.97 to 1.41 | .10 |

| Risk of stroke or stroke death only | |||

| RT alone v surgery + RT | 1.44 | 1.14 to 1.82 | .003 |

| RT alone v surgery alone | 1.59 | 1.22 to 2.06 | .0005 |

| Any RT v surgery alone | 1.23 | 1.00 to 1.51 | .05 |

| Risk of cardiovascular events | |||

| RT alone v surgery + RT | 1.02 | 0.84 to 1.25 | .81 |

| RT alone v surgery alone | 0.95 | 0.76 to 1.18 | .63 |

| Any RT v surgery alone | 0.93 | 0.80 to 1.09 | .38 |

| Risk of MI or cardiac death only | |||

| RT alone v surgery + RT | 1.08 | 0.88 to 1.31 | .48 |

| RT alone v surgery alone | 1.01 | 0.81 to 1.25 | .93 |

| Any RT v surgery alone | 0.96 | 0.81 to 1.12 | .58 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; RT, radiotherapy; MI, myocardial infarction.

Models were adjusted for age, sex, race, history of stroke (or MI for control diagnosis), other comorbid disease, chemotherapy, surgery, tumor size, extent, positive lymph nodes, grade, squamous histology, tumor site, socioeconomic status variables, year of treatment, and geographic region.

Comparison of risk of cerebrovascular events for surgery alone v surgery + RT shows no significant difference (P = .60).

Risk of Cardiac Events

There was no significant difference in incidence of cardiac events between the three treatment groups (5-year incidence of 20% in each group, P = .62). On multivariate analysis, patients who underwent radiotherapy were no more likely to experience cardiac events, even when patients who underwent radiotherapy alone were compared with the surgery plus radiotherapy and surgery alone treatment groups (P = .81 and P = .63, respectively; Table 4).

Subsidiary Analyses

Effect size of the association between treatment group and cerebrovascular events was validated in the propensity score analysis, with radiotherapy alone still associated with significantly higher cerebrovascular risk than surgery plus radiotherapy (HR = 1.37; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.72) or surgery alone (HR = 1.51; 95% CI, 1.12 to 2.05; Appendix Table A2, online only). Sensitivity analyses restricting treatment claims to those identified within 6 months and 4 months did not significantly alter associations.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrated that older head and neck cancer patients who underwent radiotherapy alone were at increased risk for subsequent cerebrovascular events. Of patients who did not succumb to other causes, approximately one third of patients who underwent radiotherapy alone experienced a cerebrovascular event within 10 years of cancer diagnosis. In contrast, only approximately one quarter of patients who underwent surgery plus radiotherapy or surgery alone experienced an event.

Our study adds several novel insights on the association between radiotherapy and cerebrovascular events in head and neck cancer patients. This study was conducted on a large, representative sample that included patients who received treatment with or without radiotherapy, thus delineating the independent effect attributable to radiotherapy. This association between treatment with radiotherapy and subsequent cerebrovascular events was maintained after thorough adjustment for covariates. Furthermore, the validating finding that no significant cardiac risk was associated with radiotherapy suggested that the increased cerebrovascular risk was less likely to be attributable to unmeasured confounding affecting patients’ treatment assignment.

Vascular risks have been explored in various cancer populations, including head and neck cancer patients.1-5,11,17-24 Dorresteijn et al4 reported a 12% 15-year incidence of stroke in younger head and neck cancer patients treated with radiation. Haynes et al5 reported a 12% 5-year incidence in patients who received a median dose of 64 Gy to the neck, similar to the 5-year incidence rate of 14% to19% reported in our study.

Stroke risks in previously studied head and neck cancer cohorts clearly exceeded risks in comparable healthy populations by 2 to 9 times.4,5 Similarly, the stroke incidence of 28.0 to 42.8 per 1,000 person-years in our sample exceeded incidences of 9.8 to 16.6 per 1,000 person-years found in an elderly community-based cohort.25 Prior studies included detailed information on the course of radiotherapy in head and neck cancer patients who suffered stroke4,5,19,23 but lacked data on stroke outcomes in head and neck cancer patients who did not undergo radiotherapy. Thus, the magnitude of independent contribution of radiotherapy to stroke events has required further clarification. Our study reported a magnitude of increased cerebrovascular risk of up to 50% in patients who underwent radiotherapy alone compared with patients who underwent surgery (Table 5). This finding is consistent with the independent effect of radiotherapy on cerebrovascular and cardiac sequelae reported in other cancer patient populations, including Hodgkin's disease,1 leukemia,17 and breast cancer.20

Table 5.

Comparison of Effect Sizes Reported in Prior Studies and Our Study

| Measure | Dorresteijn et al4 | Haynes et al5 | Present Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 2002 | 2002 | 2008 |

| No. of patients | 367 | 413 | 6,862 |

| Site | Head and neck | Head and neck | Head and neck |

| Actuarial incidence of event | 12% over 15 years | 12% over 5 years | 14%-19% over 5 years |

| Comparison (relative risk or hazard ratio) | |||

| Any RT (± surgery) v general population | 5.1 to 8.5 | 2.1 | 1.7 to 4.4* |

| Any RT (± surgery) v no RT | Analysis not performed | Analysis not performed | 1.17 to 1.23† |

| RT only v surgery + RT | Analysis not performed | Analysis not performed | 1.42 to 1.44† |

| RT only v surgery only | Analysis not performed | Analysis not performed | 1.50 to 1.59† |

Abbreviation: RT, radiotherapy.

Range is based on comparing incidence rates of 28.0 to 42.8 events per 1,000 person-years in our study cohort with 9.8 to 16.6 events per 1,000 person-years in a comparable elderly cohort.25

Ranges reflect primary outcome of stroke, carotid revascularization, or stroke death and restrictive outcome of stroke or stroke death.

Unexpectedly, patients who underwent surgery plus radiotherapy did not show increased cerebrovascular risk. This finding could have been attributable to these patients potentially having tumor sites less likely to receive comprehensive radiotherapy to the neck including significant portions of carotid vessels. Specifically, although we adjusted for tumor site in multivariate analysis, our study cannot rule out residual confounding from this important source.

In addition, head and neck cancer patients who received postoperative radiotherapy in this era typically received total doses of approximately 57.6 to 66 Gy7,8 (or up to 70 Gy boost), whereas patients treated definitively typically received 70 to 72 Gy.6 One interesting hypothesis is that a dose threshold for developing clinically significant cerebrovascular events could occur between 60 and 70 Gy. However, dose data were unavailable for our cohort, and prior population-based studies of head and neck cancer patients have not adequately investigated dose-response effects on vascular outcomes in this range. Notably, one study of older breast cancer patients reported no increased risk of stroke in patients more likely to receive radiotherapy to a supraclavicular field (with doses typically between 45 and 50 Gy).3 Furthermore, in head and neck cancer patients, a threshold effect could be biologically plausible given evidence for an additional one to two logs of vascular cell killing over this range.26 In contrast, studies of Hodgkin's disease patients report adverse cardiovascular events with doses as low as 38 to 40 Gy.27,28 Our study cannot rule out a more subtle effect of lower radiation doses in this cohort of older patients with relatively short survival, given that such an effect could require a longer latency period for development of clinically significant events compared with higher dose treatments. Alternatively, it is important to note that unidentified confounders may still exist for the association with cerebrovascular events in patients treated with radiotherapy alone. Thus, an alternative interpretation of our data would suggest that the true magnitude of association in patients treated with radiotherapy alone could be lower than that found in our cohort.

If independently validated, however, our findings could have important implications for evaluating cerebrovascular risks associated with newer radiotherapy strategies in head and neck cancer, including conformal therapy, which may spare carotid vessels, and alternative fractionation schemes.29 Additionally, benefits of screening, stroke preventive therapies, and intervention with carotid endarterectomy in these patients are unknown; prior studies suggest that screening of high-risk patients for asymptomatic carotid stenosis could be cost effective,30 and patients undergoing definitive radiotherapy may represent a subset that could benefit from noninvasive assessment including routine carotid bruit auscultation and imaging (with ultrasonography, magnetic resonance angiography, or computed tomographic angiography) within several years after treatment. Future studies may also evaluate whether stricter goals for blood pressure, lipids, and hemoglobin A1c (such as those applied to high-risk patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease) could improve outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. Because only older patients (age ≥ 65 years) were included, results require validation in younger cohorts, particularly because patients with longer survival could manifest significant risks with lower radiation doses. SEER-Medicare does not have information on specific radiation fields or dosages available, and thus, treatment groups may not reflect completely homogeneous treatment strategies. Of note, a prior study of compliance in head and neck cancer radiotherapy trials found that nearly 90% of patients fully received prescribed radiation doses.31 However, potential heterogeneity would have likely biased results toward the null if some patients were not fully treated to standard doses. Future studies with more detailed radiotherapy and comorbidity data may seek to further rule out potential residual confounding, particularly given our finding of no association with surgery plus radiotherapy.

In this cohort of older head and neck cancer patients, patients who underwent radiotherapy alone had increased cerebrovascular risk compared with patients who underwent surgery with or without radiation (19% v 14% at 5 years and 34% v 26% at 10 years after therapy, respectively). Further study of the impact of evolving radiotherapy techniques that could minimize dose to carotid arteries may be warranted, particularly in patients undergoing definitive radiotherapy.

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Grace L. Smith, Benjamin D. Smith, Thomas A. Buchholz, Sharon H. Giordano, Adam S. Garden, Wendy A. Woodward, Harlan M. Krumholz, Randal S. Weber, K-Kian Ang, David I. Rosenthal

Data analysis and interpretation: Grace L. Smith, Benjamin D. Smith, Thomas A. Buchholz, Sharon H. Giordano, Adam S. Garden, Wendy A. Woodward, Harlan M. Krumholz, Randal S. Weber, K-Kian Ang, David I. Rosenthal

Manuscript writing: Grace L. Smith, Benjamin D. Smith, Thomas A. Buchholz, Sharon H. Giordano, Adam S. Garden, Wendy A. Woodward, David I. Rosenthal

Final approval of manuscript: Grace L. Smith, Benjamin D. Smith, Thomas A. Buchholz, Sharon H. Giordano, Adam S. Garden, Wendy A. Woodward, Harlan M. Krumholz, Randal S. Weber, K-Kian Ang, David I. Rosenthal

Appendix

Study Sample and Exclusions

We excluded from this population patients diagnosed before age 65 years (n = 14,940) or before 1992 (n = 6,097) because Medicare linkage data were unavailable for these patients. We also excluded patients with prior nonskin cancer (n = 5,127), missing stage information (n = 2,941), no pathologic confirmation (n = 658), or distant metastases at diagnosis (n = 2,969), leaving 17,053 patients who met initial inclusion criteria. We further excluded patients who did not have Medicare Fee-for-Service coverage from 12 months before to 9 months after diagnosis date (n = 7,312; effectively missing comorbidity or treatment information) or who were missing date of diagnosis (n = 51). To improve sample homogeneity, we excluded patients with a diagnosis of cancer of the lip (n = 1,440), sublingual gland (n = 6), salivary gland type not specified (n = 31), or middle ear (n = 13) and patients without a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) –confirmed diagnosis of a tumor of the oral cavity or pharynx (n = 519) because the radiation treatment strategies for these patients may differ substantially from strategies for included sites. Finally, we excluded patients who were not treated with any radiotherapy or surgery (n = 773) because our study was intended to compare the effects of radiotherapy and/or surgery and patients who had neither treatment differed substantially in age and comorbid disease, leaving a final sample of 6,862 patients.

Claims Codes

Primary outcome: cerebrovascular event. Hospitalization for stroke or transient ischemic attack, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes 433 to 436 or 438; carotid revascularization procedure ICD-9 procedure code 38.12 or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 35301, 35501, or 35506 to 35508; or stroke (cerebrovascular) -related death SEER-Medicare cause of death code 160.

Secondary outcome: cardiovascular event. Hospitalization for myocardial infarction ICD-9 diagnosis code 410; percutaneous coronary intervention ICD-9 procedure code 360; coronary artery bypass graft ICD-9 procedure code 361; or cardiovascular-related death SEER-Medicare cause of death code 154.

Treatment with radiation therapy. ICD-9 procedure codes 92.21 to 92.27 or 92.29; diagnosis codes V58.0, V66.1, or V67.1; CPT codes 77401 to 77525 or 77761 to 77799; or Revenue Center codes 0330 and 0333.

Treatment with surgery. ICD-9 procedure codes 21.5 to 21.6, 22.31, 22.42, 22.60 to 22.66, 24.31, 25.1 to 25.4, 26.2, 26.29 to 26.32, 27.3, 27.32, 27.4, 27.42 to 27.43, 27.49, 27.72, 28.92, 29.33, 29.39, 30.0, 30.09, 30.1, 30.21 to 30.22, 30.29, 30.3 to 30.5, 31.5, 40.40 to 40.42, 76.2, 76.31, 76.39 to 76.42, or 76.44 to 76.45; or CPT codes 21044 to 21045, 21555 to 21557, 30117 to 30118, 30130, 30140, 30150, 31200 to 31201, 31205, 31225, 31230, 31299, 31365, 31367 to 31368, 31370, 31375, 31380, 31382, 31390, 31395, 31420, 38700, 38720, 38724, 40810, 40812, 40814, 40816, 40819, 41110, 41112 to 41114, 41116, 41120, 41130, 41135, 41140, 41145, 41150, 41153, 41155, 41825 to 41827, 42104, 42106 to 42107, 42120, 42140, 42410, 42415, 42420, 42425 to 42456, 42440, 42450, 42842, 42844 to 42845, or 42890.

Treatment with chemotherapy. ICD-9 procedure code 99.25; ICD-9 diagnosis codes V58.1, V66.2, or V67.2; CPT codes 96400 to 96549; Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes J9000 to J9999 or Q0083 to Q0085; or Revenue Center codes 0331, 0332, or 0335.

Surgical treatment to the neck. ICD-9 procedure codes 30.4 or 40.40 to 40.42; CPT codes 21045, 31365, 31368, 31390, 31395, 18720, 38724, 41135, or 42426.

Fig A1.

Cerebrovascular event-free risk over time by combined treatment groups. RT, radiotherapy; S, surgery.

Table A1.

Analysis of Potential Modifying Factors for Cerebrovascular Risk

| Interaction Term | P | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RT and age | .37 | Older age does not worsen event risk |

| RT and sex | .63 | No difference by sex in event risk |

| RT and race | .28 | No difference by race in event risk |

| RT and comorbidity | .53 | More severe comorbidity does not worsen event risk |

| RT and chemotherapy | .69 | Administration of chemotherapy does not modify event risk |

| RT and positive nodes | .43 | Presence of positive nodes does not modify event risk |

| RT and high-risk patients* | .49 | No tumor site identified modifies event risk |

Abbreviation: RT, radiotherapy.

High-risk patients are defined as those with head and neck sites of nasopharynx, tonsil, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and pharynx (sites more likely to require bilateral neck RT).

Table A2.

Detailed Results of Propensity Score Analysis

| Parameter* | Model 1: RT Alone v RT Plus Surgery | Model 2: RT Alone v Surgery Alone |

|---|---|---|

| Logistic model | ||

| Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit (P) | .64 | .31 |

| Proportional hazards model | ||

| No. of matched pairs | 1,466 | 725 |

| Hazard ratio | 1.37 | 1.51 |

| 95% CI | 1.09 to 1.72 | 1.12 to 2.05 |

| P | .006 | .008 |

Abbreviations: RT, radiotherapy; Dmax, maximum Euclidean distance.

Propensity score was based on Greedy Match algorithm with the following parameters: 1:1 case:control matching, weight 1, Dmax = 0.2, distance = weighted sum, case seed value 1, and control seed value 1. Euclidean distance yielded identical results.

Acknowledgments

We thank A.R. Todd for her assistance in editing of this article. This study used the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) –Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. We acknowledge the efforts of the Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; Information Management Services (IMS), Inc; and the SEER Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER-Medicare database.

Footnotes

published online ahead of print at www.jco.org on August 25, 2008.

Supported in part by the American Society of Clinical Oncology Young Investigator Award (B.D.S.) and by the Department of Scientific Publications, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bowers DC, McNeil DE, Liu Y, et al: Stroke as a late treatment effect of Hodgkin's disease: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 23:6508-6515, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giordano SH, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, et al: Risk of cardiac death after adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:419-424, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodward WA, Giordano SH, Duan Z, et al: Supraclavicular radiation for breast cancer does not increase the 10-year risk of stroke. Cancer 106:2556-2562, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dorresteijn LD, Kappelle AC, Boogerd W, et al: Increased risk of ischemic stroke after radiotherapy on the neck in patients younger than 60 years. J Clin Oncol 20:282-288, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynes JC, Machtay M, Weber RS, et al: Relative risk of stroke in head and neck carcinoma patients treated with external cervical irradiation. Laryngoscope 112:1883-1887, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu KK, Pajak TF, Trotti A, et al: A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) phase III randomized study to compare hyperfractionation and two variants of accelerated fractionation to standard fractionation radiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: First report of RTOG 9003. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 48:7-16, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang KK, Trotti A, Brown BW, et al: Randomized trial addressing risk features and time factors of surgery plus radiotherapy in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 51:571-578, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, et al: Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med 350:1937-1944, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Cancer Institute: SEER-Medicare linked database. http://healthservices.cancer.gov/seermedicare/

- 10.Matsen SL, Chang DC, Perler BA, et al: Trends in the in-hospital stroke rate following carotid endarterectomy in California and Maryland. J Vasc Surg 44:488-495, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patt DA, Goodwin JS, Kuo YF, et al: Cardiac morbidity of adjuvant radiotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:7475-7482, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith BD, Gross CP, Smith GL, et al: Effectiveness of radiation therapy for older women with early breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:681-690, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith BD, Haffty BG, Buchholz TA, et al: Effectiveness of radiation therapy in older women with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:1302-1310, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al: Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol 53:1258-1267, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results: SEER Extent of Disease: 1998—Codes and coding instructions. http://www.seer.cancer.gov/manuals/EOD10Dig.3rd.pdf

- 16.Mayo Clinic: Locally written SAS macros. http://mayoresearch.mayo.edu/mayo/research/biostat/sasmacros.cfm

- 17.Bowers DC, Liu Y, Leisenring W, et al: Late-occurring stroke among long-term survivors of childhood leukemia and brain tumors: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 24:5277-5282, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brada M, Burchell L, Ashley S, et al: The incidence of cerebrovascular accidents in patients with pituitary adenoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 45:693-698, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown PD, Foote RL, McLaughlin MP, et al: A historical prospective cohort study of carotid artery stenosis after radiotherapy for head and neck malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 63:1361-1367, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooning MJ, Botma A, Aleman BM, et al: Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease in 10-year survivors of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 99:365-375, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hooning MJ, Dorresteijn LD, Aleman BM, et al: Decreased risk of stroke among 10-year survivors of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24:5388-5394, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hull MC, Morris CG, Pepine CJ, et al: Valvular dysfunction and carotid, subclavian, and coronary artery disease in survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma treated with radiation therapy. JAMA 290:2831-2837, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam WW, Leung SF, So NM, et al: Incidence of carotid stenosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients after radiotherapy. Cancer 92:2357-2363, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson G, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al: Increased incidence of stroke in women with breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 41:423-429, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, et al: Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2007 update—A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation 115:e69-e171, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hei TK, Marchese MJ, Hall EJ: Radiosensitivity and sublethal damage repair in human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 13:879-884, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel DA, Kochanski J, Suen AW, et al: Clinical manifestations of noncoronary atherosclerotic vascular disease after moderate dose irradiation. Cancer 106:718-725, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hancock SL, Tucker MA, Hoppe RT: Factors affecting late mortality from heart disease after treatment of Hodgkin's disease. JAMA 270:1949-1955, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourhis J, Overgaard J, Audry H, et al: Hyperfractionated or accelerated radiotherapy in head and neck cancer: A meta-analysis. Lancet 368:843-854, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Derdeyn CP, Powers WJ: Cost-effectiveness of screening for asymptomatic carotid atherosclerotic disease. Stroke 27:1944-1950, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khalil AA, Bentzen SM, Bernier J, et al: Compliance to the prescribed dose and overall treatment time in five randomized clinical trials of altered fractionation in radiotherapy for head-and-neck carcinomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 55:568-575, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]