Abstract

Shone's anomaly is a very rare congenital cardiac malformation characterized by four serial obstructive lesions of the left side of the heart (i) Supravalvular mitral membrane (ii) parachute mitral valve (iii) muscular or membranous subaortic stenosis and (iv) coarctation of aorta. We report a unique presentation of Shone's complex in a 14-year-old adolescent male. In addition to the four characteristic lesions the patient had bicuspid aortic valve, aneurysm of sinus of valsalva, patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, persistent left superior vena cava opening into coronary sinus and severe pulmonary artery hypertension. This case report highlights the importance of a strong clinical suspicion of the coexistence of multiple congenital cardiac anomalies in Shone's complex and the significance of a careful comprehensive echocardiography.

Keywords: Coarctation of aorta, patent ductus arteriosus, ventricular septal defect, Shone's complex

INTRODUCTION

Shone's syndrome is an uncommon congenital anomaly described by Shone first in 1963. The incidence of Shone's syndrome commonly known as Shone's complex or Shone's anomaly is 0.6% of all congenital heart diseases.[1] The characteristic four lesions are coarctation of aorta, subaortic stenosis, parachute mitral valve (PMV), and supramitral ring.[2] In a complete Shone's complex all the four pathological lesions are present, while in an incomplete case three or less pathological lesions are present. The obstructive lesions in Shone's complex have a tendency to worsen over time as compared to other congenital heart diseases. The severity of mitral obstruction is the most significant indicator of survival and long-term prognosis.

CASE REPORT

A 14-year-old, adolescent male attended a routine rural health camp for complaints of increasing effort intolerance for the last 1-year and was referred to Cardiology Department for further evaluation. The major findings on clinical examination were: Pulse rate 88 beats/min with radio femoral delay; upper limb blood pressure (BP) 140/70 mm Hg; lower limb BP 86/70 mm Hg; jugular venous pressure not raised; no cyanosis and no clubbing; apex beat localized to the sixth intercostal space outside mid-clavicular line; and grade III parasternal heave. Cardiac auscultation revealed normal first heart sound, a loud pulmonary component of second heart sound, a grade 4 pansystolic murmur along the left parasternal border and a grade 3 mid diastolic murmur over the mitral area.

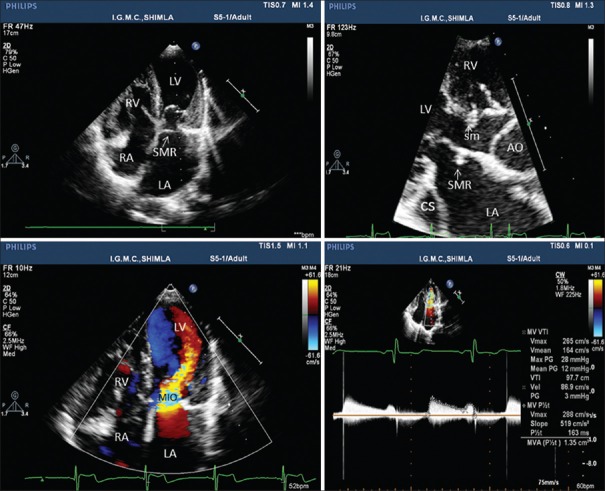

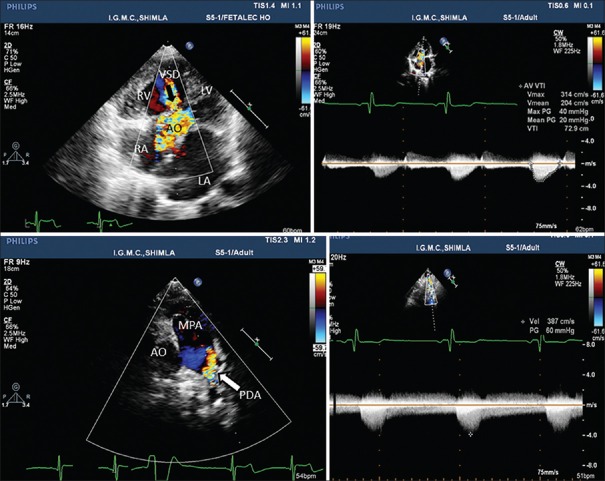

The electrocardiogram depicted a heart rate of 90 beats/min, normal sinus rhythm, and right ventricular enlargement. The chest skiagram in posteroanterior view revealed a cardiothoracic ratio of 0.6 and pulmonary plethora. Transthoracic echocardiography showed a supramitral ring (intramitral variant) and parachute like asymmetric mitral valve leading to mitral inflow obstruction with a mean gradient of 12 mmHg between left atrium and left ventricle (LV) [Figure 1, Supplementary Video File 1], subaortic membrane with left ventricular outflow obstruction with peak and mean gradients of 40 and 20 mmHg, respectively [Figures 1b and 2b], a subaortic ventricular septal defect (VSD) with left to right shunt [Figure 2a, Supplementary Video Files 2 and 3]. The parasternal short axis view demonstrated enlarged main pulmonary artery (PA) with bicuspid aortic valve. The color Doppler imaging showed retrograde flow in PA suggestive of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) [Figure 2c, Supplementary Video File 4] and suprasternal view demonstrated PDA and postductal coarctation of the aorta. Continuous wave Doppler revealed peak Doppler gradient of 60 mmHg across coarctation of aorta [Figure 2d, Supplementary Video File 5].

Figure 1.

Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrating supramitral ring, subaortic membrane, dilated coronary sinus and mitral inflow obstruction. AO: Aorta, LA and RA: Left and right atrium, LV and RV: Left and right ventricle

Figure 2.

Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrating ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, subaortic stenosis and coarctation of aorta. AO: Aorta, LA and RA: Left and right atrium, LV and RV: Left and right ventricle, MPA: Main pulmonary artery

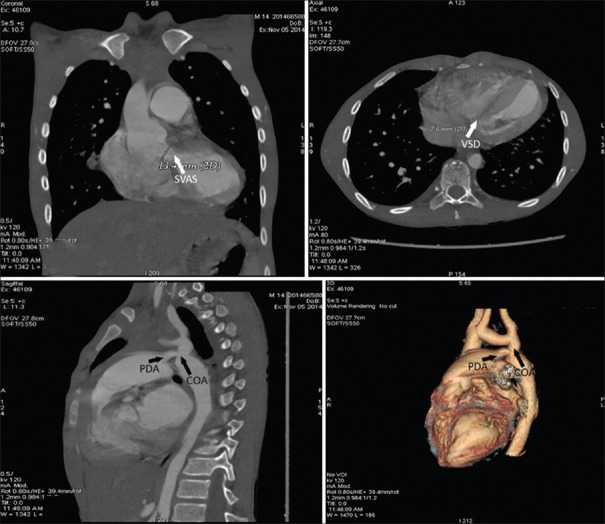

Due to dilated coronary sinus we also suspected a persistent left superior vena cava to coronary sinus, which was confirmed by contrast echocardiography [Supplementary Video File 6]. Computerized tomography demonstrated VSD, subvalvular aortic stenosis, PDA, and postductal coarctation of aorta [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Computed tomography angiography demonstrating subvalvular aortic stenosis, ventricular septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, and coarctation of aorta

The catheterization studies revealed baseline saturation of 94%, severe post-capillary PA hypertension with mitral inflow gradient of 25 mm Hg and gradient of 20 mm Hg each, across LV and left ventricular outflow tract and across coarctation segment. It also demonstrated left superior vena cava opening into coronary sinus [Supplementary Video File 7]. There was significant oxygen step-up at right ventricular level. Aortic root angiography demonstrated bicuspid aortic valve and aneurysm of sinus of valsalva, PDA, and postductal coarctation of the aorta.

DISCUSSION

Shone's syndrome comprises of multilevel left sided pathological lesions causing inflow and outflow obstruction of LV from mild to severe intensity. Mitral valve obstruction is thought to be the first pathological event in Shone's complex during early embryogenesis. This results in underdevelopment of the LV cavity, giving rise to various degrees of LV outflow tract obstruction and aortic coarctation.[1]

The origin of supra valvular mitral membrane is due to incomplete division of endocardial cushion tissue. The condition is characterized by an abnormal circumferential ridge of connective tissue on the atrial side of the mitral valve intruding on the orifice of the mitral valve. Adhesion of this ridge to the leaflets of the valve may lead to restricted movements causing mitral-valve inflow obstruction.[3] Two variants of supramitral ring have been described in relation to mitral annulus; supramitral and intramitral type.[4] The supramitral type is a fibrous shelflike membrane located superior to mitral annulus but inferior to the opening of left atrial appendage in comparison to membrane of cortriatriatum, which is superior to opening of left atrial appendage. The membrane is nonadherent to the mitral valve leaflets and the mitral valve apparatus is otherwise normal. The intramitral variant is located within the mitral tunnel, closely adherent to the valve leaflets and is associated with a high incidence of mitral valve abnormalities.[5] The intramitral type is also frequently part of the Shone's complex, as is seen in our patient.

Parachute mitral valve is characterized by the unifocal attachment of chordae irrespective of the number of papillary muscles. A true PMV is characterized by attachment of the chordae to a single or fused papillary muscle. Oosthoek et al.[6] described parachute like mitral valve with asymmetrical mitral valves having two papillary muscles, one of which is dominant and elongated, with its tip reaching to the valve leaflets. The unifocal attachment of the chordae results in stenosis of the mitral valve since the valves are held in close proximity. Our patient showed parachute like an asymmetric mitral valve, with the unifocal attachment of chordae to one papillary muscle and the second being rudimentary.

Subaortic stenosis is a fixed form of anatomic obstruction to the left ventricular outflow tract. Four anatomic variants of subaortic stenosis are thin discrete membrane consisting of endocardial fold and fibrous tissue, a fibromuscular ridge consisting of a thickened membrane with a muscular base at the crest of the interventricular septum, a diffuse and fibromuscular tunnel-like narrowing of the left ventricular out flow tract (LVOT), and accessory or anomalous mitral valve tissue. Subaortic stenosis in our patient comprises of thin discrete membrane and tunnel-like LVOT.

Presence of aortic coarctation or mitral valve anomalies should raise the suspicion of other cardiac defects since aortic coarctation occurs in 20–59% of cases with mitral valve anomalies, whereas the mitral supravalvular ring is associated with other defects in almost 90% of cases.[7] Our patient in addition to complete Shone's complex had a bicuspid aortic valve, aneurysm of sinus of valsalva, PDA, VSD, and persistent left superior vena cava opening into the coronary sinus.

Surgery can be performed to correct the defects and is typically done in stages, that too before development of pulmonary hypertension. Severity of mitral valve obstruction correlates with poor long-term prognosis. Severe forms of mitral obstruction resulting in severely elevated PA pressure portends poorest prognosis.[8,9] If either of the components of Shone's complex is detected, comprehensive echocardiography should be performed in all echocardiographic windows, so as to avoid possibility of missing other coexisting pathologies.

CONCLUSION

Additional cardiac anomalies can co-exist along with Shone's complex. The longer the patient goes undiagnosed and untreated, the more is the PA pressure elevation and poorer is the outcome thus highlighting the importance of a strong clinical suspicion and careful echocardiography.

Video available on www.heartviews.org

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Popescu BA, Jurcut R, Serban M, Parascan L, Ginghina C. Shone's syndrome diagnosed with echocardiography and confirmed at pathology. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:865–7. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shone JD, Sellers RD, Anderson RC, Adams P, Jr, Lillehei CW, Edwards JE. The developmental complex of “parachute mitral valve,” supravalvular ring of left atrium, subaortic stenosis, and coarctation of aorta. Am J Cardiol. 1963;11:714–25. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(63)90098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subramanyan R. Mitral Stenosis, Supravalvular Ring. [Last accessed on 2014 October 20]. Available from: http://www.emedicine.com/ped/topic2516.htm .

- 4.Anderson RH. When is the supravalvar mitral ring truly supravalvar? Cardiol Young. 2009;19:10–1. doi: 10.1017/S1047951108003442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Toscano A, Pasquini L, Iacobelli R, Di Donato RM, Raimondi F, Carotti A, et al. Congenital supravalvar mitral ring: An underestimated anomaly. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:538–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oosthoek PW, Wenink AC, Wisse LJ, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Development of the papillary muscles of the mitral valve: Morphogenetic background of parachute-like asymmetric mitral valves and other mitral valve anomalies. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;116:36–46. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70240-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serra W, Testa P, Ardissino D. Mitral supravalvular ring: A case report. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2005;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zucker N, Levitas A, Zalzstein E. Prenatal diagnosis of Shone's syndrome: Parental counseling and clinical outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2004;24:629–32. doi: 10.1002/uog.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikemba CM, Eidem BW, Fraley JK, Eapen RS, Pignatelli R, Ayres NA, et al. Mitral valve morphology and morbidity/mortality in Shone's complex. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:541–3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.