Abstract

Context

In 2004, California's Paid Family Leave Insurance Program (PFLI) became the first state program to provide paid leave to care for an ill family member.

Objective

To assess awareness and use of the program by employed parents of children with special health care needs, a population likely to need leave.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Telephone interviews with successive cohorts of employed parents before (November 21, 2003-January 31, 2004; n=754) and after (November 18, 2005-January 31, 2006; n=766) PFLI began, randomly sampled from 2 children's hospitals, one in California (with PFLI) and the other in Illinois (without PFLI). Response rates were 82% before and 81% after (California), and 80% before and 74% after (Illinois).

Main Outcome Measures

Taking leave, length of leave, unmet need for leave, and awareness and use of PFLI.

Results

Similar percentages of parents at the California site reported taking at least 1 day of leave to care for their ill child before (295 [81%]) and after (327 [79%]) PFLI, taking at least 4 weeks before (64 [21%]) and after (74 [19%]) PFLI, and at least once in the past year not missing work despite believing their child's illness necessitated it before (152 [41%]) and after (156 [41%]) PFLI. Relative to Illinois, parents at the California site reported no change from before to after PFLI in taking at least 1 day of leave (difference of differences, −3%; 95% confidence interval [CI], −13% to 7%); taking at least 4 weeks of leave (1%; 95% CI, −9% to 10%); or not missing work, despite believing their child's illness necessitated it (−1%; 95% CI, −13% to 10%). Only 77 parents (18%) had heard of PFLI approximately 18 months after the program began, and only 20 (5%) had used it. Even among parents without other access to paid leave, awareness and use of PFLI were minimal.

Conclusions

Parents of children with special health care needs receiving care at a California hospital were generally unaware of PFLI and rarely used it. Among parents of children with special health care needs, taking leave in California did not increase after PFLI implementation compared with Illinois.

CHRONICALLY ILL CHILDREN, OR children with special health care needs, constitute 13% to 17% of children in the United States.1-3 Children with special health care needs average 3 times as many medical encounters as other children,1-4 account for one-half of child hospital days,1 and miss nearly 3 times as much school.5 Their health-related needs create substantial pressure on parents to miss work.6,7

Parents of children with special health care needs were a major target of the 1993 Federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), which guarantees eligible workers up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave with job protection (ie, protection from being fired) to care for themselves or ill family members.8 However, only 47% of employees are eligible for FMLA leave,9 and many cannot afford unpaid leave.8 Of the 3.5 million employees who needed but could not take leave in 2000, 78% cited inability to afford leave as a reason; of these, 88% said they would have taken leave had they received some pay or additional pay.8 Availability of employer-provided leave, meanwhile, ranges widely.10 Many employees use sick leave (often violating employer policies) or vacation to care for family; other employees have no access to leave.11

Consequently, several states have passed paid family leave legislation,12-15 with additional states and Congress exploring it.16-20 Our prior research suggests that paid leave might be important for parents of children with special health care needs—parents with access to employer-provided paid leave were less likely to have unmet need for leave,7 and paid leave was associated with parent-perceived positive effects of leave on their emotional health and finances and their children's health.21 California was the first state to offer paid family leave.12 In 2004, its Paid Family Leave Insurance Program (PFLI) began providing 6 weeks of non–job-protected paid leave annually for most part-time and full-time employees at approximately 55% of salary (maximum 2008 benefit, $917 per week).12 Benefits apply after employees miss 1 week of work (continuously or cumulatively). A mandatory payroll tax (currently approximately $1 per week, subject to increase if PFLI expenditures grow) is added to the State Disability Insurance wage-statement line item and reserved in a statewide pool. A statement signed by a physician documenting the illness is required.

The Paid Family Leave Insurance Program has been a model for state and federal paid family leave efforts, yet its impact is unknown. We surveyed 2 successive cohorts of employed parents of children with special health care needs. We examined parents’ reports of taking leave and need for leave before PFLI, PFLI awareness and use approximately 18 months after benefits began, and PFLI's effect on taking leave.

METHODS

Sampling Frame

We sampled children receiving inpatient or outpatient care at 2 large tertiary-care referral centers (both major referral centers for children with special health care needs): Children's Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois (abbreviated as Illinois) and Mattel Children's Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles (abbreviated as California). Children's hospitals like Children's Memorial Hospital and Mattel Children's Hospital provide the majority of highly specialized care for children with complex and rare conditions.22 Because Illinois does not have a paid leave program, Children's Memorial Hospital served as a comparison. Both states have similar labor markets, particularly regarding unemployment,23,24 average per capita income,25,26 and nonfarming job distribution.27

We identified children with special health care needs by adapting a validated International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision billing code approach.28-31 The unmodified approach generally yields samples dominated by common diagnoses that typically require few missed work days. Because we were most interested in children with special health care needs whose parents needed to miss work, we restricted the code-list to disease categories7 with the highest average per-patient physician charges, which have been shown to correlate with illness severity.4,32-34 These disease categories included bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cerebral palsy, chronic anemias, chronic enteritis/colitis, chronic renal failure, congenital heart diseases, cystic fibrosis, degenerative neurological disorders, hydrocephalus, immunologic disorders, malignancies, organ transplant complications, and rheumatologic disorders. We omitted human immunodeficiency virus at institutional review board request.

Using this list, we recruited 2 successive cohorts of children by identifying all children (<18 years) in each hospital's billing databases who were assigned a qualifying diagnosis between October 1, 2002, and September 30, 2003 (before PFLI became available) and between October 1, 2004, and September 30, 2005 (after PFLI), listed as alive, and living in their respective states.

Because PFLI is available only to employed individuals, we focused on children with special health care needs with employed parents. However, the hospital databases that we used did not include any information regarding parent employment status. To undersample parents who were less likely to be employed, we stratified by Medicaid status, the best proxy for employment status available in the databases (details appear elsewhere7).

The study was designed to detect a reduction from an anticipated 40% of parents at the California site with unmet need for leave before PFLI to 25% after (80% power, 2-sided P<.05 for difference-of-differences analysis), with no corresponding change from a 40% Illinois baseline. This required 380 completes per site per wave among employed parents (designed to be 70% of our sample). We projected a 70% response rate and a design effect of 1.15 from sample design/nonresponse weighting, requiring an initial sample size of 777 per site per wave.

We identified children with special health care needs at the California site (1570 before and 1499 after PFLI) and at the Illinois site (3680 before and 4752 after PFLI). At each wave, we randomly selected separate cohorts of 800 children from each site.

Data Collection

Telephone interviewers conducted 40-minute computer-assisted telephone interviews (in English and Spanish). Our protocol for sampling parents in 2-parent households appears elsewhere.7

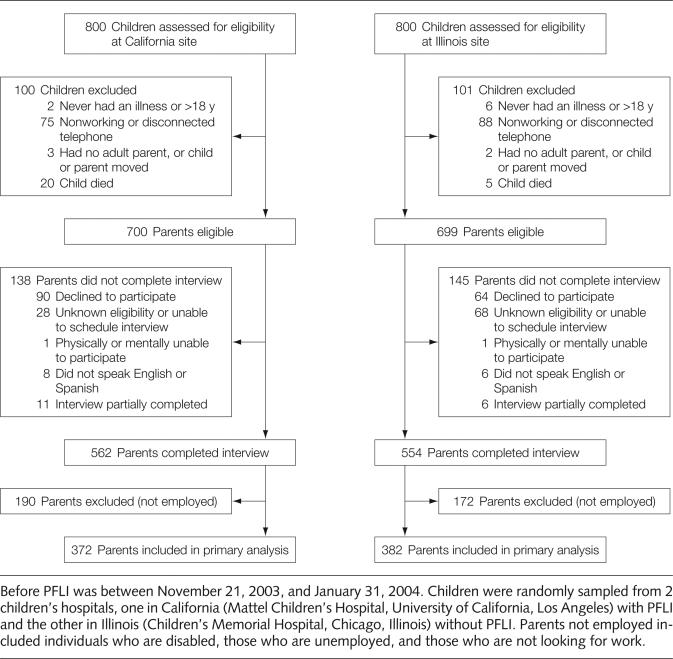

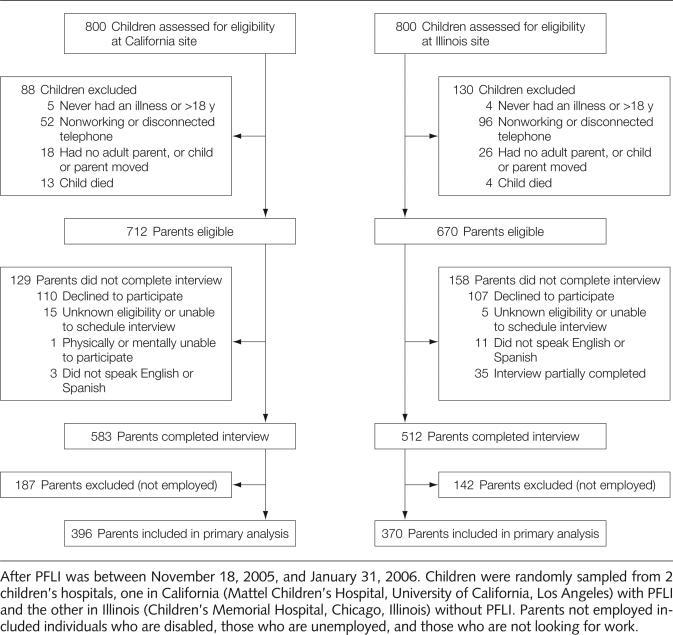

Before PFLI benefits began (November 21, 2003-January 31, 2004), we interviewed 562 parents at the California site and 554 parents at the Illinois site. Excluding parents who were never located (11%) or who were otherwise ineligible (2% had moved out-of-state or their child had died), response rates were 82% at the California site and 80% at the Illinois site.35 Approximately 18 months after benefits began (November 18, 2005-January 31, 2006), 583 parents at the California site and 512 parents at the Illinois site participated. Response rates were 81% at the California site and 74% at the Illinois site.

We received Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waivers to use hospital databases to obtain necessary private health information. The protocol was approved by all participating institutional review boards.

Survey Outcomes

Leave Usage. At each wave, we asked parents of children with special health care needs how many days of work they had missed in the past year because of their child's illness. We also asked parents about unmet need for leave (“Was there any time in the last 12 months that you felt you needed to miss work because of [child]'s illness, but you did not miss work?”). Parents who said yes were asked the reasons why they did not take leave (>1 answer could be selected). Parents were also asked about their longest leave ever due to their child's illness, whether they had cut short that leave, and why.

Awareness and Use of PFLI. After PFLI began, we asked parents at the California site whether they had heard of and used PFLI. Parents who had heard of but not used PFLI were asked why not (>1 answer could be selected).

Survey Predictors

We collected standard demographic and employment data (Table 1 and Table 2). Some items came from the US Department of Labor Survey of Employees.8 Other items were developed by the researchers; reviewed by clinicians, attorneys, and social scientists familiar with children with special health care needs and labor issues; and piloted among parents of children with special health care needs. Parents were asked about self-reported race/ethnicity (using investigator-defined categories) because of its relevance to family leave studies.11 We included overtime eligibility because having a nonsalaried position that is eligible for overtime often indicates a less-flexible work schedule.

Table 1.

Parent Characteristics in Families With at Least 1 Employed Parent Before and After PFLIa

| No. (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before PFLI |

After PFLI |

|||

| Parent Characteristics | California (n = 372) | Illinois (n = 382) | California (n = 396) | Illinois (n = 370) |

| Age, y | ||||

| 18-35 | 101 (29) | 70 (20) | 98 (27) | 95 (28) |

| 36-45 | 187 (52) | 201 (50) | 180 (43) | 181 (45) |

| ≥46 | 83 (20) | 110 (30) | 118 (30) | 94 (27) |

| Female sex | 220 (59) | 242 (65)b | 234 (64) | 226 (64) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 23 (6) | 51 (18) | 17 (6) | 37 (15) |

| Hispanic | 124 (39) | 34 (10) | 109 (38) | 47 (16) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 184 (45) | 269 (65) | 201 (41) | 256 (62) |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 41 (11) | 28 (7)b | 69 (15) | 30 (7)b |

| Parent education | ||||

| ≤High school graduate | 97 (31) | 63 (19) | 85 (34) | 57 (21) |

| Some college | 128 (35) | 134 (37) | 127 (30) | 105 (31) |

| College graduate/postgraduate education | 147 (33) | 185 (44)b | 184 (36) | 208 (49)b |

| Employment | ||||

| Full-time | 294 (78) | 287 (73) | 318 (75) | 280 (74) |

| Part-time | 78 (22) | 95 (27) | 78 (25) | 90 (26) |

| Eligible for overtime | 152 (44) | 159 (44) | 167 (41) | 152 (46) |

| Access to employer-provided paid leavec | 275 (82) | 300 (85) | 316 (75) | 301 (85)b |

| Spouse/partner's employment status | ||||

| No spouse/partner | 66 (21) | 65 (22) | 73 (26) | 63 (23) |

| Spouse employed full-time | 180 (44) | 206 (49) | 206 (47) | 205 (51) |

| Spouse employed part-time | 42 (11) | 44 (11) | 45 (10) | 43 (10) |

| Spouse not employed | 82 (25) | 67 (18) | 72 (16) | 59 (16) |

| Annual household income, $ | ||||

| < 20 000 | 46 (20) | 23 (13) | 31 (20) | 30 (16) |

| 20 000-49 999 | 100 (29) | 65 (18) | 83 (25) | 61 (21) |

| 50 000-99 999 | 114 (27) | 157 (39) | 134 (29) | 141 (34) |

| 100 000-149 999 | 49 (12) | 68 (17) | 77 (15) | 63 (15) |

| ≥150 000 | 53 (12) | 53 (13)b | 58 (11) | 59 (14) |

| No. of other children in household | ||||

| 0 | 99 (28) | 114 (29) | 115 (29) | 92 (26) |

| 1 | 149 (36) | 155 (40) | 161 (37) | 157 (40) |

| 2 | 84 (24) | 78 (21) | 89 (23) | 89 (23) |

| ≥3 | 40 (12) | 35 (10) | 31 (11) | 32 (11) |

Abbreviation: PFLI, Paid Family Leave Insurance Program.

California indicates Mattel Children's Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles; and Illinois indicates Children's Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois. All data were obtained by parent report.

P < .05 for differences between California and Illinois. Parent age and number of other children in the household were measured and tested continuously; income and education were tested as linear categories; other variables were tested as unordered categories.

Employer-provided paid leave includes sick, vacation, and other non-PFLI paid leave.

Table 2.

Child Characteristics in Families With at Least 1 Employed Parent Before and After PFLIa

| No. (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before PFLI |

After PFLI |

|||

| Child Characteristics | California (n = 372) | Illinois (n = 382) | California (n = 396) | Illinois (n = 370) |

| Age, y | ||||

| 0-4 | 96 (28) | 86 (23) | 119 (27) | 88 (21) |

| 5-9 | 88 (22) | 94 (23) | 85 (19) | 95 (25) |

| 10-14 | 117 (29) | 104 (28) | 104 (28) | 115 (33) |

| ≥15 | 71 (20) | 98 (26)b | 88 (25) | 72 (21) |

| Female sex | 193 (50) | 168 (43) | 191 (49) | 170 (46) |

| Medicaid enrollment | 35 (26) | 23 (17)b | 37 (35) | 32 (23)b |

| PedsQL scorec | ||||

| 0-40 | 55 (15) | 51 (13) | 61 (19) | 50 (15) |

| 41-60 | 68 (18) | 71 (20) | 76 (22) | 62 (17) |

| 61-80 | 126 (35) | 107 (27) | 132 (29) | 111 (30) |

| 81-100 | 123 (32) | 153 (40) | 127 (30) | 147 (39)b |

| No. of hospital admissions in past year | ||||

| 0 | 217 (55) | 246 (64) | 232 (60) | 233 (62) |

| 1 | 66 (19) | 57 (16) | 75 (18) | 65 (17) |

| 2-3 | 50 (13) | 38 (10) | 51 (13) | 45 (12) |

| ≥4 | 39 (13) | 41 (11) | 38 (9) | 27 (8) |

| No. of nights spent in hospital in past year | ||||

| 0 | 218 (56) | 250 (65) | 234 (61) | 235 (63) |

| 1-7 | 61 (18) | 64 (16) | 72 (16) | 75 (20) |

| 8-28 | 45 (13) | 41 (12) | 49 (13) | 41 (12) |

| ≥29 | 48 (14) | 27 (6)b | 41 (10) | 19 (6)b |

Abbreviation: PFLI, Paid Family Leave Insurance Program.

California indicates Mattel Children's Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles; and Illinois indicates Children's Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois. All data were obtained by parent report.

P < .05 for differences between California and Illinois. Child age, PedsQL score, number of hospital admissions, and number of nights spent in the hospital were measured and tested continuously; other variables were tested as unordered categories.

The mean PedsQL score in our sample was 66; the mean PedsQL for healthy children is 84.36

We collected 3 child illness-related measures: (1) a PedsQL short version,37 (2) number of hospitalizations in past year, and (3) number of hospital nights in past year. The PedsQL, a standard measure of pediatric health-related quality of life, does not exist for children younger than 2 years; we assigned these children the mean PedsQL score in our data and marked them with an indicator variable, allowing them to be included in models without biasing estimates of PedsQL-related associations. The number of hospitalizations and hospital nights allowed us to examine whether experiencing serious illness episodes that required hospitalization was associated with PFLI awareness and use.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses incorporated weights accounting for nonresponse (inverse predicted probabilities of multivariate logistic regressions) and Medicaid-status stratification. No variable was missing more than 3% of observations before PFLI began or more than 4% after PFLI. To prevent bias from limiting multivariate analyses to complete cases,38 we used a single-chained equations imputation.39

The analysis sample for both waves consisted of all part-time and full-time employed parents (372 from California and 382 from Illinois before PFLI began, and 396 from California and 370 from Illinois after PFLI). To analyze whether PFLI resulted in changes in taking leave and unmet need for leave, we used a difference-of-differences approach, which compared change at the California site (with PFLI) with change at the Illinois site (without PFLI). To analyze PFLI awareness and use, we used them as outcome variables in bivariate logistic regressions for parents at the California site surveyed after PFLI, with Table 1 and Table 2 variables as predictors. Although too few parents (n=20) had used PFLI to conduct multivariate analyses of use, we were able to conduct multivariate logistic regression of awareness, using a limited number of predictors (those with P<.05 bivariately) to avoid over-fitting.40,41 Finally, we performed bivariate subanalyses among parents who were aware of PFLI to examine predictors of use.

Analyses were performed by using Stata version 10 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Reported P values were 2-tailed and significance level was set at P<.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics

Respondent study flow is shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Table 1 and Table 2 show characteristics of California and Illinois respondents.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram of Participants Before Paid Family Leave Insurance Program (PFLI)

Figure 2.

Flow Diagram of Participants After Paid Family Leave Insurance Program (PFLI)

Effect of PFLI on Taking Leave

California's PFLI did not increase the percentage of parents taking leave from before to after initiation of the program (Table 3). Before PFLI began, 295 parents (81%) at the California site and 290 parents (78%) at the Illinois site took at least 1 day of leave in the previous year to care for their ill child compared with after PFLI began (327 parents [79%] at the California site and 296 parents [79%] at the Illinois site). In a difference-of-differences analysis comparing change at the California site (with PFLI) with change at the Illinois site (without PFLI), California reported no change relative to Illinois in taking at least 1 day of leave (difference-of-differences analysis, −3%; 95% confidence interval [CI], −13% to 7%).

Table 3.

Taking Leave Among Employed Parents at the California and Illinois Sites Before and After PFLIa

| No. (%) of Parents | Difference of Differences (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | California | Illinois | ||

| Took ≥1 d of leave to care for child | –3 (–13 to 7) | |||

| Before | 585 (79) | 295 (81) | 290 (78) | |

| After | 623 (79) | 327 (79) | 296 (79) | |

| Took ≥4 weeks of leave to care for child | 1 (–9 to 10) | |||

| Before | 115 (18) | 64 (21) | 51 (14) | |

| After | 112 (15) | 74 (19) | 38 (11) | |

| Not always able to miss work when necessary to care for child | –1 (–13 to 10) | |||

| Before | 290 (38) | 152 (41) | 138 (36) | |

| After | 291 (39) | 156 (41) | 135 (37) | |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PFLI, Paid Family Leave Insurance Program.

California indicates Mattel Children's Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles; and Illinois indicates Children's Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois. The change from before to after PFLI did not significantly differ between California and Illinois for these measures.

The Paid Family Leave Insurance Program also did not increase the amount of leave parents took (Table 3). Before PFLI began, 64 parents (21%) at the California site and 51 parents (14%) at the Illinois site took at least 4 weeks of leave compared with after (74 parents [19%] at the California site and 38 parents [11%] at the Illinois site). In a difference-of-differences analysis, California reported no change relative to Illinois (difference-of-differences analysis, 1%; 95% CI, −9% to 10%).

Effect of PFLI on Unmet Need for Leave

Before PFLI began, 152 parents (41%) at the California site and 138 parents (36%) at the Illinois site, and after PFLI began, 156 parents (41%) at the California site and 135 parents (37%) at the Illinois site said that, at least once in the past year, they did not miss work despite believing their child's illness necessitated it (Table 3). In a difference-of-differences analysis, California reported no change relative to Illinois (−1%; 95% CI, −13% to 10%).

Before PFLI began, the most-cited reasons (California and Illinois combined) for not missing work were could not afford to miss income (179 [24%]), might lose job or business (118 [17%]), might hurt career (108 [15%]), work was too important (103 [13%]), could not afford to miss benefits for child (111 [13%]) or self (97 [11%]), and did not want to use up time off (91 [11%]). Of parents whose longest leave was unpaid, 141 (68%) said they cut it short for financial reasons.

Awareness and Use of PFLI

Main Analyses. Only 77 parents (18%) reported having heard of PFLI and only 20 (5%) reported using it (Table 4 and Table 5). In bivariate analyses, overtime-eligible parents (generally with less flexible schedules) compared with ineligible parents were more likely to have heard of PFLI (45 [29%; 95% CI, 21%-39%] vs 32 [10%; 95% CI, 7%-14%]; P<.001) and used PFLI (13 [9%; 95% CI, 5%-18%] vs 7 [2%; 95% CI, 1%-4%]; P=.004). Parents who were employed full-time (63 [20%; 95% CI, 15%-27%]) compared with part-time (14 [10%; 95% CI, 6%-17%]; P=.03) were more likely to have heard of PFLI, but were not more likely to have used it. Compared with parents with full-time–employed spouses (43 [20%; 95% CI, 14%-28%]), single parents were less likely to have heard of PFLI (12 [9%; 95% CI, 5%-15%]; P=.02), but not less likely to have used it. Use of PFLI also increased with the number of nights spent in the hospital (odds ratio [OR], 1.07 for each additional week in the hospital; 95% CI, 1.00-1.15). Finally, neither awareness nor use of PFLI was significantly associated with parent education, access to employer provided paid leave, household income, child PedsQL score, or number of hospitalizations in the past year.

Table 4.

Awareness and Use of PFLI by Parent Characteristics Among Employed Parents at the California Site After PFLI Begana

| Parent Characteristics | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness of PFLI (n = 394) | Use of PFLI (n = 394) | |

| Total No. (%) | 77 (18) | 20 (5) |

| Age, y | ||

| 18-35 | 21 (16) | 10 (6) |

| 36-45 | 34 (20) | 7 (4) |

| ≥46 | 22 (17) | 3 (5) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 32 (20) | 5 (5) |

| Female | 45 (16) | 15 (5) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 4 (30) | 1 (3) |

| Hispanic | 25 (17) | 8 (8) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 37 (16) | 8 (3) |

| Other (non-Hispanic) | 11 (18) | 3 (4) |

| Parent education | ||

| ≤High school graduate | 18 (16) | 5 (7) |

| Some college | 26 (16) | 5 (3) |

| College graduate/postgraduate education | 33 (21) | 10 (5) |

| Spouse/partner's employment status | ||

| No spouse/partner | 12 (9) | 5 (25) |

| Spouse employed full-time | 43 (20) | 11 (55) |

| Spouse employed part-time | 11 (33) | 4 (20) |

| Spouse not employed | 11 (16)b | 0 (0) |

| Employmentc | ||

| Part-time | 14 (10) | 5 (3) |

| Full-time | 63 (20)b | 15 (6) |

| Eligible for overtime | ||

| No | 32 (10) | 7 (2) |

| Yes | 45 (29)b,d | 13 (9)b |

| Access to employer-provided paid leavee | ||

| No | 9 (13) | 3 (8) |

| Yes | 65 (19) | 16 (4) |

| Annual household income, US $ | ||

| <20 000 | 5 (8) | 2 (5) |

| 20 000-49 999 | 21 (24) | 6 (7) |

| 50 000-99 999 | 28 (18) | 7 (4) |

| 100 000-149 999 | 11 (20) | 1 (1) |

| ≥150 000 | 11 (19) | 4 (7) |

| No. of other children in household | ||

| 0 | 26 (25) | 7 (9) |

| 1 | 30 (15) | 8 (4) |

| 2 | 17 (19) | 3 (2) |

| ≥3 | 4 (6) | 2 (3) |

Abbreviation: PFLI, Paid Family Leave Insurance Program.

Two respondents replied “don't know” in response to the awareness item and were excluded from analysis; respondents who replied “no” to awareness were coded as “no” for use of PFLI. Comparisons were conducted using logistic regressions, with awareness (yes/no) and use (yes/no) as the outcomes, one for each combination of predictor and outcome. Parent age and number of other children in the household were measured and tested continuously; income was tested as linear categories; other variables were tested as unordered categories. California site indicates Mattel Children's Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles.

Significant difference (P < .05) among categories for this characteristic (within column), based on block testing of categories, when applicable.

One hundred eighty-seven unemployed parents (15%) had heard of PFLI.

A multivariate analysis predicting PFLI awareness was conducted with Table 4 and Table 5 variables. Overtime-eligible parents were more likely to have heard of PFLI than ineligible parents (odds ratio, 0.31; 95% confidence interval, 0.17-0.57). No other significant bivariate association in Table 4 or Table 5 remained significant in multivariate analysis.

Employer-provided paid leave includes sick, vacation, and other non-PFLI program paid leave.

Table 5.

Awareness and Use of PFLI by Child Characteristics Among Employed Parents at the California Site After PFLI Begana

| Child Characteristics | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness of PFLI (n = 394) | Use of PFLI (n = 394) | |

| Age, y | ||

| 0-4 | 31 (26) | 10 (9) |

| 5-9 | 10 (9) | 3 (3) |

| 10-14 | 15 (13) | 5 (6) |

| ≥15 | 21 (20) | 2 (2) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 36 (16) | 12 (6) |

| Female | 41 (20) | 8 (4) |

| Medicaid enrollment | ||

| No | 72 (20) | 18 (5) |

| Yes | 5 (13) | 2 (5) |

| PedsQL score | ||

| 0-40 | 13 (14) | 5 (5) |

| 41-60 | 7 (6) | 2 (2) |

| 61-80 | 30 (24) | 8 (7) |

| 81-100 | 27 (22) | 5 (6) |

| No. of hospital admissions in past year | ||

| 0 | 46 (16) | 9 (4) |

| 1 | 8 (12) | 3 (7) |

| 2-3 | 13 (24) | 4 (4) |

| ≥4 | 10 (27) | 4 (8) |

| No. of nights spent in hospital in past year | ||

| 0 | 47 (17) | 10 (4) |

| 1-7 | 10 (12) | 2 (2) |

| 8-28 | 8 (16) | 4 (6) |

| ≥29 | 12 (35) | 4 (13)b |

Abbreviation: PFLI, Paid Family Leave Insurance Program.

Two respondents replied “don't know” in response to the awareness item and were excluded from analysis; respondents who replied “no” to awareness were coded as “no” for use of PFLI. Comparisons were conducted using logistic regressions, with awareness (yes/no) and use (yes/no) as the outcomes, one for each combination of predictor and outcome. Child age, PedsQL score, number of hospital admissions, and number of nights spent in the hospital were measured and tested continuously; other variables were tested as unordered categories. California site indicates Mattel Children's Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles. See Table 2 for description of PedsQL score.

Significant difference (P < .05) among categories for this characteristic (within column), based on block testing of categories, when applicable.

In a multivariate analysis predicting PFLI awareness, overtime-eligible parents were more likely to have heard of PFLI than ineligible parents (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.17-0.57). No other significant bivariate associations remained significant in multivariate analysis.

Subanalyses. Even among subsets of parents with greater potential need for paid leave, PFLI awareness and use were minimal. Among parents who, despite having no access to paid leave beyond sick, vacation, or other non-PFLI leave, still missed work in the past year due to their child's illness, 102 (71%) missed enough days (>5) to qualify for PFLI; however, only 30 (15%) reported having heard of it and 10 (6%) used it. Among parents who reported unmet need for leave, 20 (9%) had heard of PFLI and 5 (2%) had used it.

Before PFLI, 63 parents (22%) at the California site and 57 parents (15%) at the Illinois site had no access to paid sick or vacation leave; after PFLI, 70 parents (26%) at the California site and 54 parents (16%) at the Illinois site had no access to paid sick or vacation leave. In addition, 219 parents (74%) at the California site and 247 parents (78%) at the Illinois site had no access to other non-PFLI paid leave before PFLI began, and 248 parents (77%) at the California site and 245 parents (81%) at the Illinois site had no such access after PFLI. In a subanalysis among parents who had heard of PFLI, parents who did not have access to vacation, sick, or other non-PFLI paid leave were more likely to have used PFLI than those with such access (3 [63%; 95% CI, 27%-89%] vs 16 [20%; 95% CI, 12%-32%]; P=.01).

Among parents who had heard of PFLI but had not used it, 34 (59%) used vacation, sick, or other non-PFLI paid leave instead, 21 (41%) did not know about or understand the program at the time, 8 (11%) missed less than the required waiting period, and 3 (10%) said their supervisors told them not to take time off even though they were eligible for PFLI (Table 6).

Table 6.

Reasons for Not Using PFLI Among Employed Parents at California Site (After PFLI Began) Who Had Heard of PFLI But Did Not Use Ita

| Reasons for Not Using PFLI | No. (%) of Parents (n = 57) |

|---|---|

| You used sick leave, vacation, or other paid time off instead | 34 (59) |

| You did not know about or understand the program | 21 (41) |

| You missed less than the mandatory 1-week waiting period | 8 (11) |

| Your supervisors told you not to take time off even though you were eligible | 3 (10) |

| You were afraid of being demoted or fired | 5 (7) |

| The application process was too difficult or inconvenient | 5 (7) |

| You were afraid of losing good job assignments or opportunities for career advancement | 4 (6) |

| You were afraid that supervisors or coworkers might resent your taking time off | 3 (4) |

| Your employer told you that you were not eligible | 1 (2) |

| Your supervisors or coworkers asked you not to take time off | 0 |

Abbreviation: PFLI, Paid Family Leave Insurance Program.

California site indicates Mattel Children's Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles.

Discussing Leave Laws With Health Care Professionals

Twenty-eight parents (6%) reported that a physician or other hospital/office staff person had discussed leave laws with them. Those parents reported that the topic was raised in these discussions by the child's physician (6 [28%]), other office/hospital staff (14 [50%]), the parent (7 [19%]), or another family member (1 [3%]).

COMMENT

Initial implementation of the nation's first paid family leave law failed to reach a large and vulnerable target constituency: parents of children with special health care needs. Approximately 18 months after PFLI began, only 18% of employed parents in our sample—drawn from a facility that serves the sickest of the sick22—had heard of PFLI and only 5% had used it. Even especially vulnerable subgroups (eg, parents without employer-provided paid leave, parents with unmet need for leave) reported low PFLI awareness and use. Results are particularly surprising because, although we intentionally studied children who were sicker than children with special health care needs nationally,22,42 their parents’ employment status still matched national trends,43 making them especially likely to need leave.

Many factors may explain the minimal use of PFLI, but lack of awareness is likely important. Uptake of new policies generally requires a combination of awareness, low perceived costs (eg, minimal income loss), and high perceived benefits (eg, improving children's health, allaying children's fears).44-46 Currently, PFLI requires that employers provide a pamphlet only to new employees (along with other benefits descriptions) and employees who take leave for a covered purpose,47 meaning that some employees must know about PFLI before asking about it or decide to take leave before knowing that they could receive pay. Indeed, many employees might never apply because they presume leave would be unpaid. Even wage statements collapse the PFLI tax into the State Disability Insurance line, which (perhaps inadvertently) further hides the existence of the benefit from employees.

In contrast with PFLI, FMLA was accompanied by a 2-year Department of Labor publicity campaign and mandatory posting of FMLA information at workplaces. In 1995, at the end of the campaign, 58% of employees who worked for employers affected by FMLA knew about the law.48 This number stands in marked contrast to the 18% of employed parents in our sample who were aware of PFLI. The discrepancy seems especially striking given that our population had substantial reason to be aware of leave options.

Potential barriers to uptake, however, do not end with lack of awareness. The PFLI does not protect employees from being fired, although employees who are also covered by FMLA are protected. Among parents in our sample who had heard of PFLI but not used it, reasons included supervisors telling them not to take time off even though they were eligible (10%) and fear of being demoted or fired (7%). An explicit job protection provision might help parents feel more confident in using PFLI.

Another potential barrier is PFLI's requirement that employees miss more than 1 week of work before receiving benefits. Among parents in our sample who had heard of but not used PFLI, 11% reported not using it because they missed less than the mandatory waiting period.

Finally, PFLI's provision of partial pay (approximately 55% of one's salary up to a cap) may have limited its use. In our prior work, we found that, although parents who received full pay during leave were more likely than parents who received no pay to report positive effects of leave on health and finances, the same was not true for parents who received only partial pay.21 If perceived benefits of paid leave diminish at lower rates of pay, 55% may not be enough to persuade some parents to apply.

This lack of awareness and use are concerning, because our data indicate a substantial need for leave among parents of children with special health care needs. Seventy-nine percent of baseline parents at California and Illinois sites took at least 1 day of leave to care for their child; 18% took at least 4 weeks. Nevertheless, 38% of parents reported not missing work when they needed to for their child's illness, often citing an inability to afford missed income. Likewise, among parents whose longest leave was unpaid, 68% said they cut it short for financial reasons.

Our study has limitations. Our sample, which was limited to 2 institutions in 2 states, may not generalize to all parents of children with special health care needs. A larger study might be more broadly representative and might find variations by geographic region, job type, and child illness category. In particular, our diagnosis list did not include serious mental health conditions and, although we included the number of hospital admissions and hospital nights as predictors, our condition selection did not directly incorporate severity grading. Furthermore, it is unclear to what degree lack of awareness of PFLI reflected a lack of effort by employers and the state to disseminate information vs poor parental recall. Parents might have learned about PFLI but then forgot about it. If this were the case, however, it would still be concerning, because our population is one for which this information would likely be especially salient. Such as cenario would simply reinforce questions about the effectiveness of PFLI dissemination.

Although our findings are generally disappointing, they are not without promise. In our subanalysis of parents who had heard of PFLI, parents were more likely to have used it if they did not have access to sick, vacation, or other non-PFLI paid leave. This suggests that, among parents who are aware of the law and undeterred by its barriers to use, PFLI might be a viable option for those who lack employer-provided leave or who need more leave than their employer provides. Forty-three percent of US private-sector workers have no paid sick leave, 33% have no paid vacation, and 62% have no paid personal leave.49 Thus, if lack of awareness and other barriers can be reduced, there is reason to believe that a substantially larger pool of parents will benefit from having PFLI.

Almost no parents reported that clinicians had discussed leave laws with them; however, clinicians (including health educators and social workers) can play a valuable role in informing parents about leave and leave laws. The American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes parents’ importance in promoting the health of ill children and advocates that clinicians adopt a family-centered approach.50,51 When children are hospitalized or diagnosed with chronic disease, it may be a particularly relevant moment to teach parents about family leave options and to discuss strategies for balancing job demands and child needs. Clinicians can advise parents of children with special health care needs that leave should be considered in family health and employment decisions, and that taking leave might improve child health and parent emotional health.

For policymakers considering paid leave programs, our findings suggest that it is insufficient for employees to learn about the program only when starting a new job or requesting leave. Additional dissemination (eg, media campaigns, periodic employer-based notification of all employees) may raise awareness. Maximizing uptake of paid leave programs among parents of children with special health care needs may be a particularly important policy goal, given their substantial need for leave.

Although our findings are preliminary, they highlight both the need for paid leave options among parents of children with special health care needs in our sample and the initial failure of California's PFLI program to meet that need. Before PFLI's implementation, many employed parents of children with special health care needs receiving care at the hospitals in our study experienced financial constraints that precluded taking leave or required them to cut short their leave. Although PFLI was designed to minimize a leave's financial hardship, parents in our California sample were generally unaware of PFLI and rarely used it, and PFLI neither increased the frequency or duration of taking leave nor decreased unmet need for leave compared with parents in the Illinois sample. Dissemination strategies may need examination before individual states or the United States as a whole adopt similar policies.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported in part by grants R21 HD052586 from the National Institutes of Health and U48/DP000056 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, RAND Health, RAND Institute for Civil Justice, and the California Endowment.

Role of the Sponsors: The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Mr Klein had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Schuster, Chung, Garfield.

Acquisition of data: Schuster, Chung, Garfield.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Schuster, Chung, Elliott, Garfield, Vestal, Klein.

Drafting of the manuscript: Schuster, Chung, Vestal.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Schuster, Chung, Elliott, Garfield, Vestal, Klein.

Statistical analysis: Schuster, Chung, Elliott, Klein.

Obtained funding: Schuster, Chung.

Study supervision: Schuster.

Additional Contributions: We thank Children's Memorial Hospital, Chicago, Illinois, and Mattel Children's Hospital, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), for providing administrative data for the study; the RAND Survey Research Group for data collection; the UCLA/RAND Work-Family Advisory Board for advice during questionnaire development; the UCLA/RAND Center for Adolescent Health Promotion and the Evanston Northwestern Healthcare Research Institute for administrative and research assistance; and Scott Stephenson, BA, and Jacquelyn Chou, BA (RAND) for manuscript assistance. Mr Stephenson and Ms Chou were both paid by the grant funding that supported the study.

Financial Disclosures: None reported.

Financial Disclosures: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newacheck PW, Kim SE. A national profile of health care utilization and expenditures for children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(1):10–17. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Dyck PC, Kogan MD, McPherson MG, Weissman GR, Newacheck PW. Prevalence and characteristics of children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(9):884–890. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.9.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein RE, Silver EJ. Comparing different definitions of chronic conditions in a national data set. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(1):63–70. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0063:cddocc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neff JM, Sharp VL, Muldoon J, Graham J, Popalisky J, Gay JC. Identifying and classifying children with chronic conditions using administrative data with the clinical risk group classification system. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(1):71–79. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0071:iaccwc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newacheck PW, Strickland B, Shonkoff JP, et al. An epidemiologic profile of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1 pt 1):117–123. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein RE. Challenges in long-term health care for children. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1(5):280–288. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001<0280:cilthc>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung PJ, Garfield CF, Elliott MN, Carey C, Eriksson C, Schuster MA. Need for and use of leave among parents of children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):e1047–e1055. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cantor D, Waldfogel J, Kerwin J, et al. Balancing the Needs of Families and Employers: Family and Medical Leave Surveys. Westat & US Dept of Labor; Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han WJ, Waldfogel J. Parental leave: the impact of recent legislation on parents' leave taking. Demography. 2003;40(1):191–200. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perrin JM, Fluet CF, Honberg L, et al. Benefits for employees with children with special needs: findings from the Collaborative Employee Benefit Study. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(4):1096–1103. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heymann SJ, Earle A, Egleston B. Parental availability for the care of sick children. Pediatrics. 1996;98(2 pt 1):226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.2002. California Paid Leave Law, S 1661.

- 13.2007. Washington Paid Leave Law, S 5659, 60th Leg.

- 14.New Jersey Paid Leave Law. 2008:S786/A873. 213th Leg. [Google Scholar]

- 15.2008:17–152. Accrued Sick and Safe Leave Act of 2008, DC Law. [Google Scholar]

- 16.MSNBC Associated Press Survey: U.S. work-place not family-oriented. [June 13, 2008];Nation lags behind virtually all wealthy countries in work-life balance. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/16907584/from/ET/.

- 17.Healy P. [June 13, 2008];Clinton proposes big grants for family leave. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/17/us/politics/17clinton.html?ex=1350360000&en=e455abfedf1705c6&ei=5124&partner=permalink&exprod=permalink.

- 18.The Paid Family Leave Collaborative Web site Paid Family Leave California. [June 13, 2008];Paid leave activity in other states. http://www.paidfamilyleave.org/otherstates.html.

- 19.National Partnership for Women and Families [June 13, 2008];State and local action on paid family and medical leave: 2008 outlook. http://www.nationalpartnership.org/site/DocServer/Paid_Leave_Tracking.pdf?docID=1921.

- 20.Chen DW. [June 13, 2008];New Jersey Assembly approves paid leave to care for baby or ailing kin. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/14/nyregion/14leave.html.

- 21.Schuster MA, Chung PJ, Elliott MN, Garfield CF, Vestal KD, Klein DJ. Parents of children with special health care needs: perceived effects of leave from work and the role of paid leave. Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.138313. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions . All Children Need Children's Hospitals. 2nd ed. National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions; Alexandria, VA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Department of Labor [June 13, 2008];Bureau of Labor Statistics. California at a Glance. http://www.bls.gov/eag/eag.ca.htm.

- 24.US Department of Labor [June 13, 2008];Bureau of Labor Statistics. Illinois at a Glance. http://www.bls.gov/eag /eag.IL.htm.

- 25.US Department of Commerce [June 13, 2008];Bureau of Economic Analysis. BEARFACTS: Illinois 1996-2006. http://www.bea.gov/bea/regional/bearfacts/stateaction.cfm?fips=17000&yearin=2006.

- 26.US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis [June 13, 2008];BEARFACTS: California 1996-2006. http://www.bea.gov/bea/regional/bearfacts /stateaction.cfm?fips=06000&yearin=2006.

- 27.US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics [June 13, 2008];Employees on nonfarm payrolls by state and selected industry sector, seasonally adjusted. http://www.bls.gov/news.release/laus.t05.htm.

- 28.Kuhlthau KA, Beal AC, Ferris TG, Perrin JM. Comparing a diagnosis list with a survey method to identify children with chronic conditions in an urban health center. Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2(1):58–62. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2002)002<0058:cadlwa>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang W, Ireys HT, Anderson GF. Comparison of risk adjusters for Medicaid-enrolled children with and without chronic health conditions. Ambul Pediatr. 2001;1(4):217–224. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2001)001<0217:corafm>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perrin JM, Kuhlthau K, McLaughlin TJ, Ettner SL, Gortmaker SL. Changing patterns of conditions among children receiving Supplemental Security Income disability benefits. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(1):80–84. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferris TG, Perrin JM, Manganello JA, Chang Y, Causino N, Blumenthal D. Switching to gatekeeping: changes in expenditures and utilization for children. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):283–290. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muldoon JH, Neff JM, Gay JC. Profiling the health service needs of populations using diagnosis-based classification systems. J Ambul Care Manage. 1997;20(3):1–18. doi: 10.1097/00004479-199707000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gay JC, Muldoon JH, Neff JM, Wing LJ. Profiling the health service needs of populations: description and uses of the NACHRI Classification of Congenital and Chronic Health Conditions. Pediatr Ann. 1997;26(11):655–663. doi: 10.3928/0090-4481-19971101-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neff JM, Sharp VL, Muldoon J, Graham J, Myers K. Profile of medical charges for children by health status group and severity level in a Washington State Health Plan. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(1):73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Association for Public Opinion Research [June 13, 2008];AAPOR Outcome Rate Calculator Version 2.1. http: //www.aapor.org/uploads/Response_Rate_Calculator.xls.

- 36.Chan KS, Mangione-Smith R, Burwinkle TM, Rosen M, Varni JW. The PedsQL: reliability and validity of the short-form generic core scales and Asthma Module. Med Care. 2005;43(3):256–265. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(6):329–341. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003<0329:tpaapp>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):227–241. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford T, Feinstein A. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun GW, Shook TL, Kay GL. Inappropriate use of bivariable analysis to screen risk factors for use in multivariable analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(8):907–916. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.US Department of Health and Human Services . The National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs Chartbook 2001. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, US Dept of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davidoff AJ. Insurance for children with special health care needs: patterns of coverage and burden on families to provide adequate insurance. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):394–403. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Daponte B, Sanders S, Taylor L. Whydolow-income households not use food stamps? evidence from an experiment. J Hum Resour. 1999;34(3):612–628. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shone LP, Szilagyi PG. The State Children's Health Insurance Program. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2005;17(6):764–772. doi: 10.1097/01.mop.0000187192.74295.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Currie J, Grogger J. Medicaid expansions and welfare contractions: offsetting effects on prenatal care and infant health? J Health Econ. 2002;21(2):313–335. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(01)00125-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.California Employment Development Department [June 13, 2008];Disability insurance: about the DI program. State of California. http://www.edd.ca.gov/direp/diind.htm.

- 48.Commission on Family and Medical Leave . A Workable Balance: Report to Congress on Family and Medical Leave Policies. Women's Bureau, US Dept of Labor; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 49.US Bureau of Labor Statistics . National Compensation Survey: Employee Benefits in Private Industry in the United States, March 2007. Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Dept of Labor; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Committee on Hospital Care American Academy of Pediatrics. Family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 pt 1):691–697. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coleman WL, Garfield CF, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health Fathers and pediatricians: enhancing men's roles in the care and development of their children: American Academy of Pediatrics Policy Statement. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1406–1411. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]