Abstract

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is typically diagnosed using subjective complaints, screening measures, clinical judgment, and a single memory score. Our prior work has shown that this method is highly susceptible to false-positive diagnostic errors. We examined whether the criteria also lead to “false-negative” errors by diagnostically reclassifying 520 participants using novel actuarial neuropsychological criteria. Results revealed a false-negative error rate of 7.1%. Participants’ neuropsychological performance, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, and rate of decline provided evidence that an MCI diagnosis is warranted. The impact of “missed” cases of MCI has direct relevance to clinical practice, research studies, and clinical trials of prodromal Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, misclassification, misdiagnosis, neuropsychology

INTRODUCTION

The criteria for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) employed by many large-scale biomarker studies, such as the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), rely on subjective cognitive complaints, cognitive screening measures, clinical judgment, and a single impaired memory score to arrive at the diagnosis [1, 2]. Although efficient, this conventional diagnostic method has resulted in coarse characterizations of the type and severity of MCI examined despite the availability of rich cognitive and functional data in many studies. Using novel cluster analytic statistical techniques, our prior work has shown that conventionally-diagnosed MCI participants present with several distinct cognitive phenotypes (e.g., amnestic MCI, dysnomic MCI, dysexecutive/mixed MCI) which are not captured by standard diagnostic measures [3, 4]. Importantly, we have also demonstrated that one-third of conventionally-diagnosed participants actually perform within normal limits on more extensive cognitive testing despite their MCI diagnosis [3, 4]. Individuals comprising this “Cluster-Derived Normal” MCI subgroup (1) have normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Alzheimer's disease (AD) biomarker levels, (2) over-report subjective cognitive complaints, and (3) show a low rate of progression to AD, all of which suggest they represent “false-positive” errors in MCI diagnosis [4, 5]. Specifically, the Cluster-Derived Normal group demonstrated the lowest rate of progression to dementia (11%) relative to the other MCI subtypes (amnestic MCI: 35%, dysnomic MCI: 41%, dysexecutive/mixed MCI: 56%) over an average of approximately 23 months of follow-up. Further, the Cluster-Derived Normal group showed a high rate of reversion to cognitively normal (9%), while the rate of reversion was only 1-2% in the other MCI subtypes. The designation of “cognitively normal” in these large-scale biomarker studies may suffer from the same lack of precision. Therefore, within the ADNI dataset, we examined whether the conventional criteria also lead to “false-negative” diagnostic errors by misclassifying those with mild cognitive deficits that were not detected using standard diagnostic techniques.

METHODS

Data were obtained from the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). The primary goal of ADNI is to test whether neuroimaging, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. ADNI is the result of efforts of many co-investigators from a range of academic institutions and private corporations, and subjects have been recruited from over 50 sites across the U.S. and Canada. Additional information about ADNI is available at http://www.adni-info.org.

Participants and procedure

Participants were 520 individuals (mean age = 74.3 years, standard deviation [SD] = 5.8; 48.8% male) who were identified as cognitively normal by ADNI (see diagnostic criteria below) and had neuropsychological data available. All ADNI participants underwent a “screening” visit, during which they completed the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale, and the Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised (WMS-R) Logical Memory test. They then underwent a “baseline” visit, at which point they completed a neuropsychological evaluation and underwent lumbar puncture for CSF collection. According to ADNI's procedure manuals, the window from “screening” to “baseline” was not more than 28 days.

For the current study, all participants were diagnostically reclassified using novel actuarial neuropsychological criteria [6] (see below) based on two memory scores (i.e., Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, delayed free recall & recognition), two language scores (i.e., Animal Fluency; Boston Naming Test), and two processing speed/executive function scores (i.e., Trail Making Test, Parts A & B) from each participant's baseline neuropsychological evaluation. We examined baseline CSF biomarker concentrations of amyloid-beta (Aβ1-42) and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau181p).

Conventional diagnostic criteria, as operationalized by ADNI [2]

Participants were diagnosed with MCI by ADNI if the following criteria were met: (1) there was a subjective memory concern reported by the participant or an informant; (2) the participant's total score on the MMSE was between 24-30 (inclusive); (3) the participant's total score on the Global CDR was 0.5; (4) the participant demonstrated abnormal memory function, defined as scoring below education-adjusted cutoffs on a paragraph memory test (i.e., delayed free recall of Story A from WMS-R Logical Memory II). Participants were diagnosed as cognitively normal by ADNI if the following criteria were met: (1) there was no subjective memory concern; (2) the participant's total score on the MMSE was between 24–30 (inclusive); (3) the participant's total score on the Global CDR was 0.0; (4) the participant did not demonstrate abnormal memory function on the paragraph memory test.

Actuarial neuropsychological diagnostic criteria [6]

Participants were diagnosed with MCI if any one of the following three criteria were met: (1) the participant demonstrated an impaired score, defined as less than 1 SD below the age-corrected normative mean, on two measures within at least one cognitive domain (i.e., memory, language, or processing speed/executive function); or (2) the participant demonstrated one impaired score, defined as less than 1 SD below the age-corrected normative mean, in each of the three cognitive domains sampled; or (3) the participant's total score on the Functional Activities Questionnaire was greater than or equal to 9. This latter criterion approximates Jak et al.'s [7] incorporation of instrumental activities of daily living assessment into diagnosis. If none of these three MCI criteria were met, the participant was diagnosed as cognitively normal.

Assessment of progression to MCI or AD

ADNI participants were followed longitudinally, with visits every 6 months for the first two years, followed by annual visits. At each follow-up visit, any change to a participant's diagnosis (e.g., progression to MCI or AD) was coded in the ADNI database. ADNI's diagnosis of MCI at each follow-up visit was based on the conventional diagnostic criteria described above. A diagnosis of AD was based on the following criteria: (1) there was a subjective memory concern reported by the participant or an informant; (2) the participant's total score on the MMSE was between 20–26 (inclusive); (3) the participant's total score on the Global CDR was 0.5 or 1.0; (4) the participant demonstrated abnormal memory function by scoring below education-adjusted cutoffs on Story A of the WMS-R Logical Memory II subtest; and (5) the participant met National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria for probable AD.

RESULTS

Thirty-seven individuals (mean age = 75.2 years, SD = 6.0; 48.6% male) were identified as cognitively normal based on the conventional criteria but met criteria for MCI using the actuarial neuropsychological approach, a potential false-negative diagnostic error rate of 7.1%. The remaining 483 individuals were identified as cognitively normal by both the conventional criteria and the actuarial neuropsychological approach, a true-negative rate of 92.9%. There were no differences between the false-negative and true-negative groups with regard to age or gender (p-values > 0.05); however, the false-negative group was less educated than the true-negative group (p = 0.02); see Table 1. The false-negative group performed worse on all neuropsychological measures examined compared to the true-negative group (p < 0.001); see Table 1. The overall sample of 520 participants had an average follow-up period of 40 months (SD = 31 months; range 0–120 months).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and neuropsychological performance for the false-negative and true-negative groups.

| False-Negative (n = 37) | True-Negative (n = 483) | F or χ2 | Sig. | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age (years) | 75.2 (6.0) | 74.3 (5.8) | F = 0.89 | P = 0.38 | |

| Education (years) | 15.4 (3.2) | 16.5 (2.6) | F = 5.87 | P = 0.02 | |

| Gender (% male) | 48.6% | 48.9% | χ2 = 0.001 | p = 0.98 | φc < 0.01 |

| Neuropsychological battery (raw) | |||||

| AVLT Recall | 5.1 (3.9) | 7.7 (3.8) | F = 15.33 | p < 0.001 | |

| AVLT Recognition | 10.0 (3.7) | 13.0 (2.3) | F = 53.45 | p < 0.001 | |

| Animal Fluency | 16.4 (5.3) | 20.8 (5.3) | F = 24.00 | p < 0.001 | |

| BNT | 25.4 (3.9) | 28.3 (1.8) | F = 67.56 | p < 0.001 | |

| TMT, Part A (s) | 52.9 (20.6) | 33.4 (10.0) | F = 107.15 | p < 0.001 | |

| TMT, Part B (s) | 144.1 (73.1) | 81.6 (37.1) | F = 81.37 | p < 0.001 |

Data are summarized as mean (standard deviation), unless otherwise indicated. AVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; BNT, Boston Naming Test; TMT, Trail Making Test.

Progression to MCI or AD

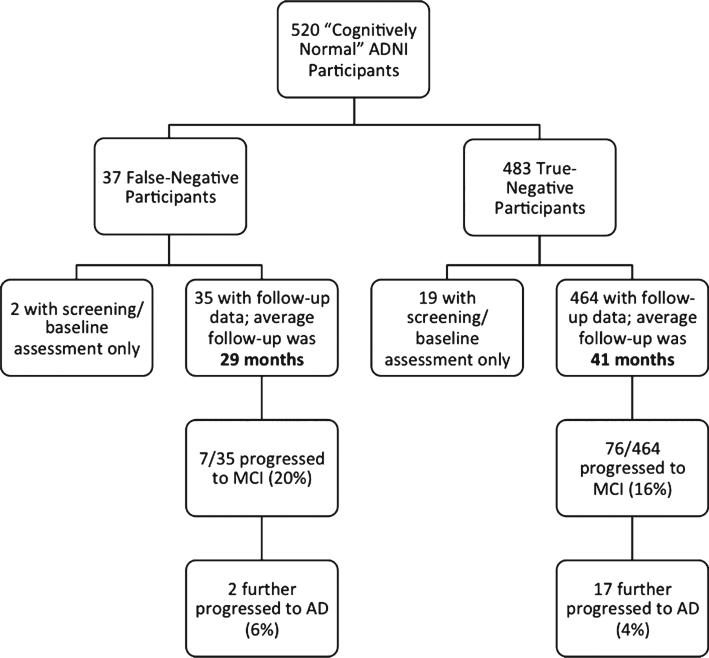

Of the 37 false-negative diagnoses, follow-up data was available for 35 participants. Of these, seven individuals (20%) progressed to an ADNI diagnosis of MCI. The time point at which an MCI diagnosis was made ranged from 12 months to 84 months following the initial screening (mean time point of diagnosis = 45 months; SD = 26 months). Two of these seven individuals progressed further to meet criteria for a diagnosis of AD (diagnoses made at 72 and 96 month follow-up visits); see Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing the flow of progression to MCI and AD for the false-negative and true-negative groups. Note that the true-negative group had a significantly longer period of follow-up compared to the false-negative group (p < 0.01).

The 20% rate of decline in the false-negative group is higher than that of the false-positive (i.e., Cluster-Derived Normal) group who showed a progression rate of 11% [4], although this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.11). The false-negative group did not show a progression rate as high as the true-positive MCI participants (i.e., amnestic MCI, dysnomic MCI, and dysexecutive/mixed MCI [4]) who had an overall progression rate of 40% (p < 0.01). There was no difference in the average amount of follow-up between the false-negative, false-positive, and true-positive groups (p > 0.05), as each group had approximately 26–29 months of follow-up data available. The true-negative group had an overall progression rate of 16%; however, this group also had a significantly longer period of follow-up relative to the other groups (mean = 41 months; p < 0.01); see Fig. 1.

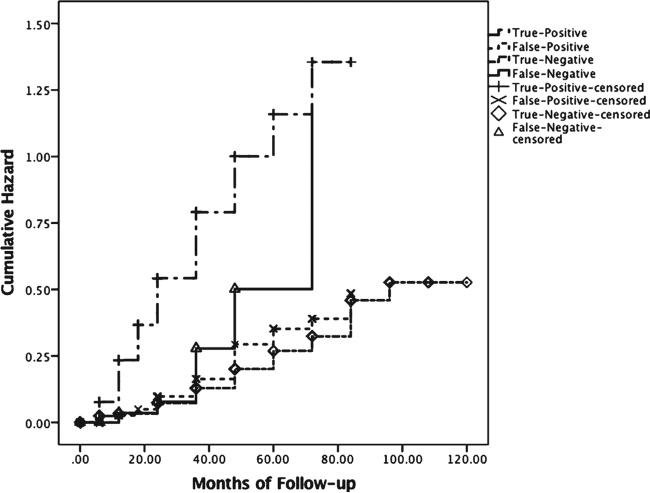

Hazard curves from a survival analysis are shown in Fig. 2 for the false-negative, true-negative, false-positive (i.e., Cluster-Derived Normal [4]), and true-positive (i.e., amnestic MCI, dysnomic MCI, and dysexecutive/mixed MCI [4]) groups. Findings show that the false-negative group is initially similar to the true-negative and false-positive groups with regard to progression rates, but diverges at approximately 36 months and reaches the level of the true-positive group by month 74.

Fig. 2.

Hazard function showing risk of progression to MCI/AD across time for the false-negative (n = 37), true-negative (n = 483), true-positive (i.e., amnestic MCI, dysnomic MCI, and dysexecutive/mixed MCI [4]; n = 543) and false-positive (i.e., Cluster-Derived Normal [4]; n = 282) groups.

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers

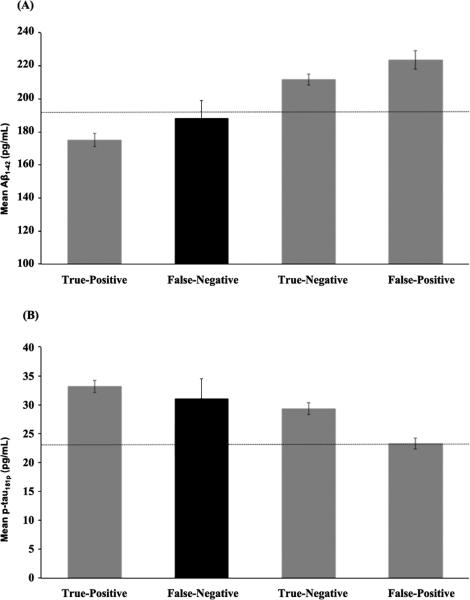

CSF AD biomarker levels for false-negative, true-negative, false-positive (i.e., Cluster-Derived Normal [4]), and true-positive (i.e., amnestic MCI, dysnomic MCI, and dysexecutive/mixed MCI [4]) groups are presented in Fig. 3. For Aβ1-42, the false-negative group demonstrated an average concentration value that did not differ from the true-positive group (p = 0.34), suggesting that individuals with a false-negative diagnosis are indeed comparable to the impaired MCI subtypes. The false-negative group had lower values than the true-negative group although this difference was not statistically signifi-cant (p = 0.09), as well as significantly lower Aβ1-42 values than the false-positive group (p = 0.01).

Fig. 3.

CSF (A) Aβ1-42 and (B) p-tau181 biomarkers levels for the true-positive participants (i.e., amnestic MCI, dysnomic MCI, and dysexecutive/mixed MCI [4]; n = 278 with CSF data), false-negative participants (n = 24 with CSF data; highlighted in black), true-negative participants (n = 324 with CSF data), and false-positive participants (i.e., Cluster-Derived Normal [4]; n = 156 with CSF data). Error bars represent standard error of the mean. The dotted lines represent the cut-points for an abnormal value (Aβ1-42:<192 pg/mL; p-tau181p:>23 pg/mL) [8].

Forp-tau181p,the false-negative group again looked similar to the impaired MCI subtypes, as the average concentration value did not differ from the true-positive group (p = 0.59). There was also no significant difference between the false-negative and the true-negative groups (p = 0.64); this appeared to be driven by the presence of more individuals with abnormal levels of p-tau181p than would be expected in a true-negative/cognitively normal group. Finally, the false-negative group had significantly higher levels of p-tau181p than the false-positive group (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Our findings show that the widely-used conventional diagnostic criteria for MCI lead to significant errors in classification. False-negative diagnostic errors were relatively common (7.1% of ADNI's cognitively normal cohort), although less common than the false-positive diagnostic errors we previously observed (34.2% of ADNI's MCI cohort) [4]. These results are in line with those from previous research showing that cognitive screening measures (e.g., the MMSE) have limited value in distinguishing between healthy controls versus MCI [9], as well as research showing that errors in MCI diagnosis can occur when individuals are classified based on subjective complaints [10]. Our actuarial neuropsychological criteria for MCI provide an alternative to diagnostic approaches that emphasize subjective complaints, screening measures, clinical judgment, and a single impaired cognitive test score. MCI diagnosed via our actuarial neuropsychological method has been shown to yield stronger associations with CSF and genetic biomarkers, more stable diagnoses, and identified a greater percentage of participants who progressed to dementia compared to conventional MCI diagnostic criteria [6].

A limitation of the study is that we cannot be certain that all individuals identified as false-negatives will show progression to AD, particularly given the limited amount of follow-up data available (25 of the 37 participants had less than or equal to 24 months of follow-up). Additional longitudinal follow-up is needed to further clarify whether each of these participants truly represents a missed case of MCI. However, their neuropsychological performance, CSF biomarkers, and rate of decline observed over the short timeframe provide compelling evidence that these individuals are more at-risk than their original ADNI classification as “cognitively normal” would suggest. Thus, a diagnosis of MCI appears warranted in these cases.

The impact of “missed” cases of MCI is not trivial and may have direct relevance to clinical practice. Specifically, incorrectly identifying individuals as cognitively normal may lead to missed opportunities for intervention (e.g., cognitive rehabilitation) or cause them to be withheld from potentially beneficial treatment. In addition, the particular diagnosis impacts the type of recommendations that a clinician provides to a patient and family. Recommendations related to maintaining cognitive function by controlling vascular risk factors and encouraging physical/intellectual activity may be relevant for both MCI and cognitively normal individuals; however, such preventative measures may be highlighted more strongly in cases of MCI. There are also a number of recommendations that a clinician may make for a patient who is diagnosed with MCI which are not applicable if one is cognitively normal. These could include compensatory strategies (e.g., use of a calendar or pillbox; receiving written instructions from medical providers), referral to a neurologist or other provider, and recommendation for a follow-up neuropsychological evaluation to monitor change. Thus, accurate diagnosis is key in providing the most appropriate recommendations to a patient and family.

Diagnostic errors arising from the use of conventional MCI criteria could also adversely impact research studies of prodromal AD. Enrolling false-positive MCI cases and missing false-negative MCI cases in such studies may weaken observed relationships among diagnosis, AD biomarkers, and rates of progression. Results could be further weakened by including cognitively impaired individuals in “cognitively normal” samples used for comparison to MCI groups. Finally, diagnostic inaccuracy has important implications for clinical trials aimed at treatment of MCI. Our results suggest that the application of actuarial neuropsychological methods to subject selection for clinical trials of MCI, and less reliance on conventional MCI diagnostic criteria, will enhance the ability to discover significant drug effects. In sum, by using more comprehensive cognitive data and employing actuarial methods, diagnostic precision can be enhanced resulting in more homogeneous participant samples for biomarker and clinical trials in MCI and prodromal AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research reported was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 AG049810 (MB), K24 AG026431 (MB), and P50 AG05131 (DG). Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer's Association; Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; GE Healthcare; Innogenetics, N.V.; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (http://www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/15-0986r1).

REFERENCES

- 1.Petersen RC, Morris JC. Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity and treatment target. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1160–1163. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.7.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, Jack CR, Jr, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Toga AW, Trojanowski JQ, Weiner MW. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): Clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74:201–209. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark LR, Delano-Wood L, Libon DJ, McDonald CR, Nation DA, Bangen KJ, Jak AJ, Au R, Salmon DP, Bondi MW. Are empirically derived subtypes of mild cognitive impairment consistent with conventional subtypes? J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2013;19:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1355617713000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Clark LR, Jak AJ, Nation DA, McDonald CR, Libon DJ, Au R, Galasko D, Salmon DP, Bondi MW. Susceptibility of the conventional criteria for mild cognitive impairment to false-positive diagnostic errors. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:415–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Galasko DR, Salmon DP, Bondi MW. Subjective cognitive complaints contribute to misdiagnosis of mild cognitive impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20:836–847. doi: 10.1017/S135561771400068X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bondi MW, Edmonds EC, Jak AJ, Clark LR, Delano-Wood L, McDonald CR, Nation DA, Libon DJ, Au R, Galasko D, Salmon DP. Neuropsychological criteria for mild cognitive impairment improves diagnostic precision, biomarker associations, and prediction of progression. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:275–289. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jak AJ, Bondi MW, Delano-Wood L, Wierenga C, Corey-Bloom J, Salmon DP, Delis DC. Quantification of five neuropsychological approaches to defining mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:368–375. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819431d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw LM, Vanderstichele H, Knapik-Czajka M, Clark CM, Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Blennow K, Soares H, Simon A, Lewczuk P, Dean R, Siemers E, Potter W, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker signature in Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative subjects. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:403–413. doi: 10.1002/ana.21610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitchell AJ. A meta-analysis of the accuracy of the mini-mental state examination in the detection of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:411–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenehan ME, Klekociuk SZ, Summers MJ. Absence of a relationship between subjective memory complaint and objective memory impairment in mild cognitive impairment (MCI): Is it time to abandon subjective memory complaint as an MCI diagnostic criterion? Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1505–1514. doi: 10.1017/S1041610212000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]