Abstract

Azoospermia or oligozoospermia due to disruption of spermatogenesis are common causes of human male infertility. We used the technique of spermatogonial transplantation in two infertile mouse strains, Steel (Sl) and dominant white spotting (W), to determine if stem cells from an infertile male were capable of generating spermatogenesis. Transplantation of germ cells from infertile Sl/Sld mutant male mice to infertile W/Wv or Wv/W54 mutant male mice restored fertility to the recipient mice. Thus, transplantation of spermatogonial stem cells from an infertile donor to a permissive testicular environment can restore fertility and result in progeny with the genetic makeup of the infertile donor male.

Approximately 50% of human infertility is attributable to male defects, 70–90% of which arises from impaired spermatogenesis with the clinical presentation of abnormal sperm production, such as oligo- or azoospermia1,2. The process of spermatogenesis can be divided into three phases: mitotic proliferation of spermatogonia, meiotic division of spermatocytes and morphologic differentiation of haploid cells during spermiogenesis. All phases of spermatogenesis are supported by and dependent on an intimate interaction between germ cells and somatic Sertoli cells, which provide the microenvironment essential for functional spermatogenesis3. Disruption of spermatogenesis can therefore be caused by defects affecting either the germ cells or the Sertoli cells and the testicular environment, or by a combination of both. In most cases of male infertility with azoospermia, the underlying pathogenesis is not well defined. To determine the location of the defect and to potentially correct it, germ cells from affected individuals would need to be exposed to a normal testicular environment.

To investigate whether germ cells of an infertile male animal were capable of generating functional spermatozoa after exposure to a defective testicular environment, we used two well-defined mutant mouse strains, Steel (Sl; Genome Database designation, Mgf) and dominant white spotting (W) (ref. 4), and the newly developed spermatogonial transplantation technique5–7. The W locus encodes the Kit proto-oncogene, a membrane-bound tyrosine kinase8,9, that serves as the receptor for Steel factor, the gene product of the Sl locus on mouse chromosome 10 (refs. 10,11). Although Kit is expressed on progenitor cells and differentiating cells during hematopoiesis, melanogenesis and gametogenesis12–14, expression of Steel factor during embryogenesis is associated with the migratory pathways and homing sites of hematopioetic stem cells, melanoblasts and germ cells15. Because of a defect in the Steel factor/Kit receptor system, Sl and W homozygous mutant mice have deficiencies in melanogenesis, hematopoiesis and spermatogenesis4,16.

Studies have investigated whether defects in hematopoiesis and melanogenesis in Sl and W mice can be corrected by reciprocal transplantation of bone marrow17,18, spleen19 and neural crest tissue20 or by the transplantation of wild-type cells into Sl and W recipients17,19,21. These studies have shown that transplantation of Sl or wild-type cells into W recipients can induce hematopoiesis and pigmentation, whereas transplantation into Sl recipients or transplantation of W cells into wild-type recipients fails to restore function19. These experiments indicate that defects in the W mutation are intrinsic to precursor cells, whereas the Sl mutation results in an impaired microenvironment that is deleterious to the development of hematopoiesis or pigment formation. In the reproductive system, W and Sl mutations cause infertility by affecting the survival, migration and proliferation of primordial germ cells in embryos as well as spermatogenesis and oogenesis in adults. Kit is expressed on germ line cells14 whereas Steel factor expression has been identified in the migratory pathway of primordial germ cells and on Sertoli and granulosa cells15,22. Steel factor, especially the membrane-bound form, is important for the survival of primordial germ cells23 and expression of Steel factor on Sertoli cells is essential for spermatogonial proliferation24.

Because transplantation of male germ cells was not possible until recently, a previous study reported the production of aggregation chimeras of Sl and wild-type embryos25. Fertile chimeras produced progeny with the Sl phenotype, indicating that Sl primordial germ cells can develop into spermatogonia and give rise to functional spermatogenesis when supported by wild-type Sertoli cells and environment. In that study25, male germ cells with the Sl mutation were exposed to a normal microenvironment through all stages of development. However, it was not clear if spermatogonia in the testes of an adult homozygous Sl mouse with phenotypic azoospermia would be capable of initiating functional spermatogenesis when they were moved to a permissive microenvironment even though they had never been exposed to membrane-bound Steel factor or a normal testis microenvironment. If successful, transplantation of germ cells from an infertile testis with defective Sertoli cell function to a recipient testis with normal microenvironment could provide a treatment for male infertility caused by defects in the testicular somatic cells, even in cases of long duration, as is often the situation in infertile animals and men.

Transplantation of germ cells from Sl donors to W recipients

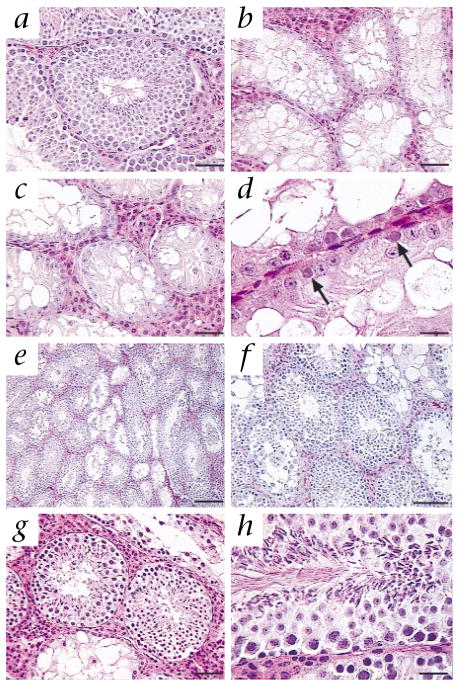

The development of the spermatogonial transplantation technique5,6 allowed us to study if male germ line stem cells taken from an infertile adult male could develop functional spermatogenesis once provided with a permissive testicular microenvironment. We used the well-defined model of male infertility represented by Sl and W mutant mice (Fig. 1). The Sl mutation deletes the entire Sl gene, and the Sld mutation deletes the transmembrane and intracellular domains. Thus, male mice with the Steel (Sl/Sld) mutation are azoospermic because they lack the membrane-bound form of stem cell factor on Sertoli cells26. The testes contain spermatogonia, but spermatogenesis does not occur. The W mutation is a 78-amino-acid deletion that includes the transmembrane domain, and the Wv mutation, with a point mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain, results in a defective receptor on the germ cell. Male mice with these W mutations used as recipients are infertile and their testes do not generate spermatogenesis because of a defect in the Kit receptor on male germ cells8,9,14. The testicular microenvironment is believed to be normal but endogenous spermatogenesis cannot occur. We collected germ cells from infertile Sl/Sld mice and transplanted these into the testes of infertile W/Wv or Wv/W54 mice; any spermatogenesis in a recipient W mutant male testis after transplantation of Sl/Sld germ cells must result from donor stem cells. Testis size in both W and Sl mutant mice is considerably less (approximately 15 mg) than that in fertile wild-type male mice (approximately 110 mg), because spermatogenesis is absent in both mutant strains (Fig. 2a–d). However, some spermatogonia are present in the seminiferous tubules of adult Sl mutant mice (Fig. 2d, arrows), and it is believed, but has not been demonstrated, that some of these spermatogonia are stem cells. After transplantation of fewer than 1 × 105 cells into each W recipient testis (which is less than 10% of the cells recovered from an Sl donor testis), restoration of spermatogenesis occurred in 17 of 21 recipient testes (Table 1), indicating that some of the spermatogonia in adult compound heterozygous mutant Sl males are fully functional stem cells. There was morphologically normal spermatogenesis in the seminiferous tubules of recipient mouse testes, by histological examination (Fig. 2e–h and Table 1). We killed two recipient males for histological analysis of their testes 4 months after spermatogonial transplantation. The remaining recipient W mice were mated with wild-type, Sld/+ or Wv/+ females (+ indicates wild-type) over a period of 1 year to determine whether spermatogonial transplantation had restored fertility in recipient males, and whether the donor haplotype was inherited by progeny of the recipient male. Four of the nine males mated produced progeny within 5.5–8 months after transplantation of Sl/Sld donor cells (Table 1). The level of spermatogenesis and the fertility rate did not seem to differ much between the first experiment, with W/Wv recipients, and the second experiment, with Wv/W54 recipients. In the second experiment, we also administered the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide, which increases colonization in wild-type recipient mice27. There may have been too few recipient mice included in these two experiments to detect an effect of the agonist, or W recipients may be less responsive to leuprolide. Three Wv/Wv males and three Wv/W54 males that had not received germ cell transplantations did not produce any progeny when mated with wild-type females for a period of 1 year, and their testes showed no evidence of spermatogenesis on histological examination (data not shown).

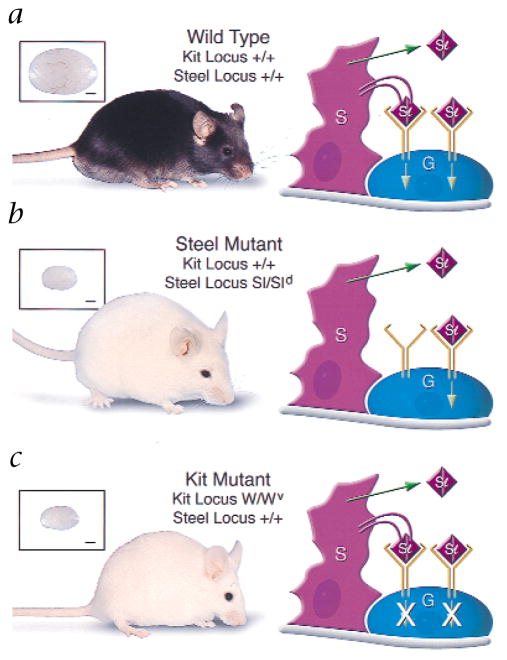

Fig. 1.

Steel factor (Kit ligand)–Kit receptor interaction in the mouse testis, with phenotypes and testis sizes of mice. a, Black wild-type C57BL/6 male; testis weight, 107 mg. In wild-type mice, Sertoli cells (S) express both the soluble and the membrane-bound form of Steel factor. Functional Kit receptor dimers on the germ cells (G) interact with the soluble and membrane-bound form of Steel factor. Signal transduction then occurs by autophosphorylation-induced interaction with target proteins. b, White Sl mutant (Sl/Sld) male; testis weight, 14 mg. In Sl/Sld mice, Sertoli cells do not express the membrane-bound form of Steel factor because the Sl mutation deletes the entire gene, and the Sld mutation deletes the transmembrane and intracellular domains. Therefore, only the soluble form of Steel factor is produced to interact with Kit receptors on germ cells. Binding of the soluble form is not sufficient for normal germ cell differentiation. c, White Kit mutant (W/Wv) male; testis weight, 15 mg. In W/Wv mice, Sertoli cells express both the soluble and the membrane bound form of Steel factor. However, the W mutation is a 78-amino-acid deletion that includes the transmembrane domain, and the Wv mutation results in a defective receptor on the germ cell because of a point mutation in the tyrosine kinase domain. Therefore, neither the bound nor the soluble form of Steel factor can effectively influence germ cells. Scale bars (insets) represent 1 mm.

Fig. 2.

Microscopic appearance of seminiferous tubules of W/Wv recipient mouse testes after transplantation of Sl/Sld germ cells. a, Wild-type C57BL/6 male with normal spermatogenesis. b, W/Wv male (recipient strain). Spermatogenesis is absent; seminiferous tubules contain almost exclusively Sertoli cells. c and d, Sl/Sld male (donor strain). Spermatogenesis is absent, but a few germ cells are present on the basement membrane (arrows, d). e and f, W/Wv recipient male (number 1807) 107 d after transplantation of germ cells from Sl/Sld donor. Spermatogenesis occurs in most seminiferous tubules. g and h, W/Wv recipient male (number 1805) 365 days after transplantation of germ cells from Sl/Sld donor. Spermatogenesis occurs in most seminiferous tubules. Hematoxylin and eosin stain. Scale bars represent 50 μm (a–c and g), 20 μm (d and h), 200 μm (e) and 100 μm (f).

Table 1.

Transplantation of testis cells from infertile Sl mice (Sl/Sld) to infertile W mice (W/Wv or Wv/W54)

| Recipient mouse numbera | Transplantation to analysis (days) | Percent of tubule cross-sections with spermatogenesisb | Transplantation to first progeny (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1803 | R | 365 | 90 (82/91) | 249 |

| L | 55 (50/90) | |||

| 1804 | R | 365 | 28 (33/120) | NP |

| L | 23 (17/73) | |||

| 1805 | R | 365 | 66 (81/122) | 164 |

| L | 25 (37/149) | |||

| 1806 | R | 129 | 45 (81/179) | ND |

| L | 43 (72/166 | |||

| 1807 | R | 107 | 72 (108/150) | ND |

| L | 0 (0/98) | |||

| 2257 | R | 365 | 32 (22/69) | NP |

| L | 0 (0/88) | |||

| 2258 | R | 365 | 46 (64/138) | NP |

| L | 32 (39/123) | |||

| 2259 | R | 365 | 89 (98/118) | 206 |

| L | 62 (74/120) | |||

| 2260 | R | 365 | 90 (56/62) | 234 |

| L | 79 (80/101) | |||

| 2261 | R | 365 | 0 (0/114) | NP |

| L | 0 (0/119) | |||

| 2262 | R | 365 | 19 (14/73) | NP |

| L | ND | |||

Mice 1803–1807, W/Wv; mice 2257–2262, Wv/W54.

In parenthesis, tubule cross-sections containing spermatogenesi/total cross-sections examined in each testis. R, right testis; L, left testis; ND, not determined; NP, no progeny.

Analysis of progeny

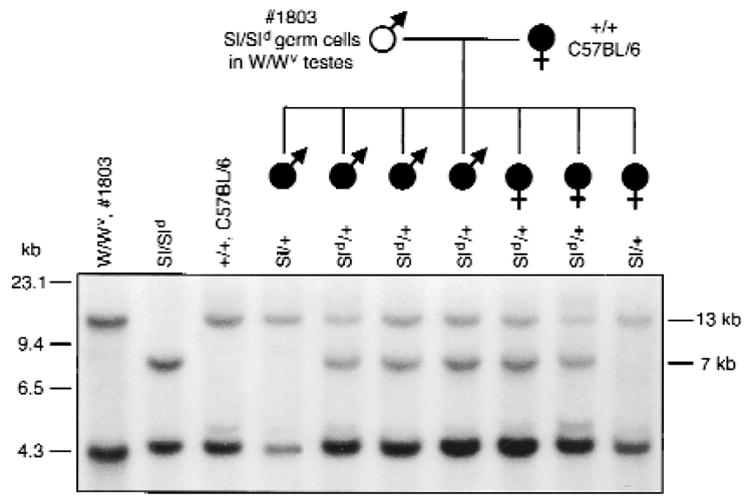

Examining the coat color of pups that resulted from mating recipient males to females heterozygous for the Sl or W mutation allowed us to clearly identify progeny resulting from recipient sperm with the Sl mutant haplotype. A completely white phenotype could only be produced when both parental alleles had the Steel mutation. The progeny of W/Wv recipient mice with transplanted Sl/Sld germ cells mated with Sld/+ females consisted of pups with a dark coat color (potentially Sl/+ or Sld/+) and pups with the completely white phenotype (potentially Sl/Sld or Sld/Sld) typical of the homozygous Steel mutation (Table 2). This demonstrates that spermatozoa from recipient males had the Sl or Sld alleles, because completely white pups could only result from matings in which both male and female gametes had the Sl genotype. No white pups resulted from the mating of recipient males with Wv/+ females, indicating that, as expected, the transplanted Sl/Sld testis cells were not able to confer functional capability to the defective spermatogonia of homozygous W mice. To further confirm the genotypes of the progeny, we analyzed DNA from seven weanling mice resulting from the mating of a wild-type female with a W/Wv recipient male transplanted with Sl/Sld germ cells by Southern blot analysis using a probe generated from Sl cDNA (Fig. 3). This analysis demonstrated that both the Sl and Sld haplotypes were transmitted to the progeny of the W recipient male.

Table 2.

Progeny from W/Wv recipient mice injected with Sl/Sld donor testis cells

| Fertile recipient | Number of litters | Litter size (mean ± SD) | Progeny of Sld/+ female | Progeny of Wv/+ female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of litters | White progenya | Number of Litters | White Progenya | |||

| 1803 | 10 | 3.7 ± 2.0 | 2 | 2/5 | 3 | 0/10 |

| 1805 | 16 | 4.3 ± 2.4 | 4 | 5/18 | 3 | 0/11 |

Completely white progeny/total progeny. Number of litters from Sld/+ and Wv/+ females does not equal total number of litters because some matings were with wild-type females.

Fig. 3.

Pedigree and Southern blot analysis of seven weanling mice from the mating of a white (open symbol) W/Wv recipient male mouse (number 1803) to a black (filled symbols) wild-type (+/+, C57BL/6) female mouse. Both the Sl and Sld haplotype of the donor germ cells were transmitted to male and female progeny of the recipient, indicating that both alleles present in donor cells were segregated during meiosis to individual spermatozoa. Left and right margins, molecular size markers: The wild-type locus produces bands at 4.3 and 13 kb, the Sl locus produces no bands, and the Sld locus produces bands at 4.3 and 7 kb (ref. 10).

Discussion

In this study of the Sl and W mutant mouse models, germ cell transplantation overcame infertility caused by a defective testicular microenvironment. These results confirm that the relationship between Sl and W mice, which has been demonstrated by transplantation studies in hematopoietic and melanogenic systems17–20, holds true in the spermatogenic system as well. Furthermore, Sl/Sld germ cells that had never been exposed to the membrane-bound form of Steel factor during development to sexual maturity were able to generate spermatogenesis in the recipient testis. Previous experiments using aggregation chimeras of Sl and wild-type mouse embryos, in which Sl germ cells were able to produce spermatozoa after development in a permissive environment from early embryonic stages onward, could not address this long-term effect of the Sl defect25. Moreover, here the testicular environment in W mutant recipient mice, which had never been exposed to endogenous germ cell differentiation, supported spermatogenesis from competent transplanted germ cells that resulted in fertility of recipient mice. Thus, neither the stem cells of the Sl testis nor the supporting cell compartment of the W testis lost their ability to function appropriately despite never having been exposed to the full complement of intercellular signals before transplantation.

The high level of fertility achieved here was unexpected. In previous studies, transplantation of wild-type testis cells to W recipients resulted in spermatogenesis, but the recipient mice never became fertile (refs. 6,28 and R.L.B. and T.O, unpublished observations). A possible explanation is that here, cells were introduced by injection into the efferent ducts7, whereas in earlier studies, cells were transplanted by direct injection into the seminiferous tubules of the recipient testis6,28. Thus, this difference in technique could account for our success. However, transplantation of wild-type testis cells directly into the seminiferous tubules of wild-type recipients does result in fertility of some recipient animals6. Therefore, the tubule injection technique can produce fertile recipients. Another possible reason for our success is a higher concentration of stem cells in the suspension of donor cells. Testes of Sl/Sld mice do not contain differentiated germ cells, which constitute 90% of the cell population of a normal testis29. Therefore, spermatogonial stem cells might be present at a higher concentration in Sl/Sld donor testes, although the total number of stem cells could be less than that in a normal testis30. Thus, the donor cells we used were possibly enriched for stem cells; the extent of colonization is related to the number of stem cells transplanted31,32. In some cases of human oligo- or azoospermia, stem cells may also represent a higher proportion of total cells than found in the normal testis, particularly in situations in which differentiated cells are absent but spermatogonia are present.

No human equivalent to the Steel mutation has been documented, but a genetic defect in humans resulting in abnormal pigmentation (piebaldism) is equivalent to the W mutation in mice33. In this defect, affected individuals are fertile, probably because they are heterozygous and the normal allele assures production of sufficient protein to allow function. Unfortunately, in most cases of human male infertility with oligo- or azoospermia, the etiology and pathogenesis are undefined. When a male is infertile, but a few spermatozoa or haploid stages of differentiated germ cells are present, the condition may be overcome by assisted reproductive techniques like in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection34 and perhaps round spermatid injection35. However, clinical conditions like Sertoli cell only syndrome, severe germ cell depletion or spermatogenic maturation arrest36 cannot be corrected by the assisted reproductive techniques now available, because few germ cells or only diploid cells are present. Given the results presented here using an infertile mouse model with only a few diploid spermatogonia, spermatogonial transplantation could be a therapeutic option when a defective testicular environment is suspected, and no differentiated haploid germ cells or spermatozoa are produced.

Advances in recent years have greatly expanded the range and versatility of the spermatogonial transplantation technique, and continued progress may soon make it an option in some cases of animal or human infertility. Germ cells of many species can now be transplanted and will colonize recipient testes5,37–41, and the technical feasibility of homologous male germ cell transfer has been reported for the primate testis42. Studies in the rat demonstrate that the immunological differences between animals of the same species may not pose a difficult problem for the generation of spermatogenesis after spermatogonial transplantation40. In cases in which only small numbers of spermatogonial stem cells can be recovered from a donor testis, it will be useful to expand the germ cells in vitro before transplantation; spermatogonial stem cell culture systems are now being developed43,44. Autologous transfer of spermatogonial stem cells could also have potential clinical applications for patients undergoing radiation or chemotherapy that will destroy endogenous spermatogenesis. In these cases, stem cells could be collected before therapy, stored frozen and transplanted back to the patient when the testicular environment has recovered. Cryopreservation of spermatogonial stem cells before transplantation has been successful in all species studied so far39,41,45. In selected situations, xenogeneic transplantation of spermatogonia37,39,41 could provide a therapeutic approach. For example, spermatogonia from an infertile male might be transplanted to a heterologous recipient to determine whether the cells are capable of undergoing expansion in the seminiferous tubules of a recipient animal. Future developments might even allow donor-derived gametes recovered from the heterologous recipient to be used for in vitro fertilization or intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Although many options are available for investigation in the clinical application of spermatogonial transplantation, appropriate procedures must be developed before results can be extrapolated to a variable, out-bred, clinical population. Whatever the reasons for or the protocol used in germ cell transplantation, a healthy microenvironment in recipient testes is essential for successful colonization. Although many factors are necessary to achieve the appropriate milieu, treatment of recipient animals with the gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist leuprolide improves donor cell-derived colonization of recipient testes in mice and rats27,40. Similar regimens will likely be useful or required in other recipient species.

In conclusion, our studies indicate that both male germ line stem cells and the supporting environment can retain full functional capability for long periods of time in the absence of normal intercellular signals and cellular differentiation stages. This has important implications for males who have never been fertile or have been infertile for a long period. If a few spermatogonial stem cells remain, it may be possible for them to generate spermatogenesis to haploid stages of differentiation or even mature spermatozoa, provided a suitable environment is supplied, and these differentiated cells could be used in assisted reproductive techniques. Transplantation of stem cells from an infertile testis to a normal testis, preferably devoid of competing endogenous spermatogenesis, could provide the necessary environment and allow in situ differentiation of stem cells to occur. The possibility of obtaining offspring from males with oligo- and azoospermia has improved considerably with the development of assisted reproductive techniques, and testis cell transplantation should allow additional progress in this area. Our demonstration that spermatogonial stem cells retain their functional capability for a long period even in a defective environment will encourage attempts to provide the conditions necessary for these stem cells to differentiate and thus lead to new approaches to correct infertility.

Methods

Collection of germ cells from Sl mutant donor mice

Donor cells (approximately 1 × 106 cells/testis) were isolated from 8-week-old Sl/Sld mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) by a two-step enzymatic digestion technique as described7. Cells were suspended in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 6 mM glutamine, 6 mM lactate, 0.5 mM pyruvate, 30 mg/l penicillin and 50 mg/l streptomycin) at a final concentration of 2.2 × 107 cells/ml in the first experiment (with W/Wv recipients) and 2.9 × 107 cells/ml in the second experiment (with Wv/W54 recipients). The viability of cells was more than 95% as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

Recipient W mutant mice and donor cell transplantation

Donor cells were transplanted to five W/Wv and seven Wv/W54 recipient mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine) in the first and second experiments, respectively. Homozygous W/W and W54/W54 mice die in utero or are born dead. Therefore, the less-severe Wv allele must be paired with the homozygous lethal mutations in order to produce viable, infertile recipients. Both recipients are immunologically compatible with the donor Sl/Sld mice. The seminiferous tubules of recipient mice were filled with the donor cell suspension by injection through the efferent ducts as described7. A cell suspension of approximately 3 μl (less than 1 × 105 cells) was injected into a W recipient testis, filling 83 ± 5.4% (mean ± s.d.) of the tubules in each testis. This is in contrast to the 10 μl used for a busulfan-treated wild-type recipient testis in earlier experiments7; the W testis (approximately 15 mg) is smaller than the busulfan-treated wild-type testis (approximately 34 mg). In the second experiment, recipient mice received 7.6 mg/kg leuprolide acetate (gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist; a gift from TAP Pharmaceuticals, Deerfield, Illinois) subcutaneously 4 weeks before transplantation; this treatment improves colonization after spermatogonial transplantation27,40.

Analysis of recipient mice

Two recipient W/Wv mice were killed by CO2 narcosis at 107 and 129 days after donor cell transplantation, and both testes were removed. Testes were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 h and processed for paraffin embedding and sectioning. Four histological sections were made from the testes of each mouse, with a 25-μm interval between sections, and the sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Each slide was viewed at a magnification of ×400 to determine the extent of spermatogenesis in recipient mouse testes: The number of tubule cross-sections with spermatogenesis (defined as the presence of multiple layers of germ cells in the seminiferous tubule) or no spermatogenesis was recorded for one section from each testis. The remaining recipient mice were housed with several types of females (Sld/+, Wv/+ or wild-type) during the course of 1 year. In the resulting progeny, coat color was recorded and tail samples were collected from selected mice to determine genotype. One year after transplantation, all remaining recipient males were killed and their testes were processed as described above. As controls, three Wv/Wv and three Wv/W54 non-transplanted males were housed with wild-type females for 1 year, and their testes were then analyzed for evidence of spermatogenesis.

Southern blot analysis

Genomic DNA (8 μg) isolated from tail tissue samples was digested for 6 h with EcoRI, separated by electrophoreses in an 0.8% agarose gel, and blotted onto a nylon membrane (Hybond-N4; Amersham). The membrane was hybridized for 16 h at 45 °C with a 32P-random-prime-labeled (Boehringer) Sl cDNA probe (0.4 kb) in the presence of formamide, then was washed and exposed to X-ray film for 3 d at −80°C. The Sl cDNA probe used for hybridization was prepared by cutting a 434-base-pair fragment from the full-length Sl cDNA (provided by Y. Matsui) using digestion with NciI and BglI.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Nagano, K. Orwig and T. Shinohara for discussions and suggestions. We also thank O. Jacenko and M. Campbell for advice and assistance with DNA analysis, and J. Barker for the W54 mouse line. In addition, we thank C. Freeman and R. Naroznowski for assistance with animal maintenance and experimentation, and J. Hayden (registered biological photographer; Blue Bell, Pennsylvania., BioGraphics) for photography and Fig. 1 schematic. Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NICHD 36504), the US Department of Agriculture/National Research Institute Competitive Grants Program (99-35205-8620), the Commonwealth and General Assembly of Pennsylvania, and the Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation.

References

- 1.Greenberg SH, Lipshultz LI, Wein AJ. Experience with 425 subfertile male patients. J Urol. 1978;119:507–510. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57531-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sigman M, Lipshulz LI, Howard SS. In: Infertility in the Male. 3. Lipshulz LI, Howard SS, editors. Mosby; St. Louis: 1997. pp. 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell LD, Ettlin RA, SinhaHikim AP, Clegg ED. Histological and Histopathological Evaluation of the Testis. Cache River, Clearwater, Florida: 1990. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silvers WK. The Coat Colors of Mice. Springer Verlag; New York: 1979. pp. 206–223. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinster RL, Zimmermann JW. Spermatogenesis following male germ-cell transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11298–11302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinster RL, Avarbock MR. Germline transmission of donor haplotype following spermatogonial transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11303–11307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogawa T, Aréchaga JM, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Transplantation of testis germinal cells into mouse seminiferous tubules. Int J Dev Biol. 1997;41:111–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabot B, Stephenson DA, Chapman VM, Besmer P, Bernstein A. The protooncogene c-kit encoding a transmembrane tyrosine kinase receptor maps to the mouse W locus. Nature. 1988;335:88–89. doi: 10.1038/335088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geissler EN, Ryan MA, Housman DE. The dominat white spotting (W) locus of the mouse encodes the c-kit protooncogene. Cell. 1988;55:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zsebo KM, et al. Stem cell factor is encoded at the Sl locus of the mouse and is the ligand for the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor. Cell. 1990;63:213–224. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90302-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang E, et al. The hematopoietic growth factor KL is encoded by the Sl locus and is the ligand of the c-kit receptor, the gene product of the W locus. Cell. 1990;63:225–233. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90303-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nocka K, et al. Expression of c-kit gene products in known cellular targets of W mutations in normal and W mutant mice – evidence for impaired c-kit kinase in mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1989;3:816–826. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogawa M, et al. Expression and function of c-kit in hemopoietic progenitor cells. J Exp Med. 1991;174:63–71. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorrentino V, Giorgi M, Geremia R, Besmer P, Rossi P. Expression of the c-kit protooncogene in the murine male germ cells. Oncogene. 1991;6:149–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsui Y, Zsebo KM, Hogan BLM. Embryonic expression of a haematopoietic growth factor encoded by the Sl locus and the ligand for c-kit. Nature. 1990;347:667–669. doi: 10.1038/347667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Russell ES. Hereditary anemias of the mouse: A review for geneticists. Adv Genet. 1979;20:357–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell ES, Bernstein SE, Lawson FA, Smith LJ. Long-continued function of normal blood-forming tissue transplanted into genetically anemic hosts. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;23:557–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCulloch EA, Siminovich EA, Till JL. Spleen-colony formation in anemic mice of genotype W/Wv. Science. 1964;144:844–846. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3620.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernstein SE. Tissue transplantation as an analytic and therapeutic tool in hereditary anemias. Am J Surg. 1970;119:448–451. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(70)90148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer TC, Green MC. An experimental analysis of the pigment defect caused by mutations at the W and Sl loci in mice. Dev Biol. 1968;18:62–75. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(68)90023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huszar D, Sharpe A, Jaenisch R. Migration and proliferation of cultured neural crest cells in W mutant neural crest chimeras. Development. 1991;112:131–141. doi: 10.1242/dev.112.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manova K, et al. The expression pattern of the c-kit ligand in gonads of mice supports a role for the c-kit receptor in oocyte growth and in proliferation of spermatogonia. Dev Biol. 1993;157:85–99. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolci S, et al. Primordial germ cell survival in culture requires membrane bound mast cell growth factor. Nature. 1991;352:809–811. doi: 10.1038/352809a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshinaga K, et al. Role of c-kit in mouse spermatogenesis: identification of spermatogonia as a specific site of c-kit expression and function. Development. 1991;113:689–699. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakayama H, et al. Effect of the steel locus on mouse spermatogenesis. Development. 1988;402:117–126. doi: 10.1242/dev.102.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flanagan JG, Chan D, Leder P. Transmembrane form of the c-kit ligand growth factor is determined by alternative splicing and is missing in the Sld mutation. Cell. 1991;64:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90326-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogawa T, Dobrinski I, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Leuprolide, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist, enhances colonization after spermatogonial transplantation into mouse testes. Tissue Cell. 1998;30:583–588. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(98)80039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell LD, Franca LR, Brinster RL. Ultrastructural observations of spermatogenesis in mice resulting from transplantation of mouse spermatogonia. J Androl. 1996;17:603–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellvé AR. Purification, culture, and fractionation of spermatogenic cells. Meth Enzymol. 1993;225:84–113. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25009-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCoshen JA, McCallion DJ. A study of the primordial germ cells during their migratory phase in Steel mutant mice. Experientia. 1975;31:589–590. doi: 10.1007/BF01932475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dobrinski I, Ogawa T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Computer assisted image analysis to assess colonization of recipient seminiferous tubules by spermatogonial stem cells from transgenic donor mice. Mol Reprod Dev. 1999a;53:142–148. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199906)53:2<142::AID-MRD3>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shinohara T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. β1- and α6-intergin are surface markers on mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5504–5509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleischman RA, Saltman DL, Stastny V, Zneimer S. Deletion of the c-kit protoconcogene in the human developmental defect piebald trait. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10885–10889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silber SJ. What forms of male infertility are there left to cure? Hum Reprod. 1995;10:503–504. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a135977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tesarik J, Mendoza C, Testart J. Viable embryos from injection of round spermatids into oocytes. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:525. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508243330819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin-du Pan RC, Campana A. Physiopathology of spermatogenic arrest. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:937–946. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clouthier DE, Avarbock MR, Maika SD, Hammer RE, Brinster RL. Rat spermatogenesis in mouse testis. Nature. 1996;381:418–421. doi: 10.1038/381418a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jiang FX, Short RV. Male germ cell transplantation in rats: Apparent synchronization of spermatogenesis between host and donor seminiferous epithelia. Int J Androl. 1995;18:326–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1995.tb00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogawa T, Dobrinski I, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Xenogeneic spermatogenesis following transplantation of hamster germ cells to mouse testes. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:515–521. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogawa T, Dobrinski I, Brinster RL. Recipient preparation is critical for spermatogonial transplantation in the rat. Tissue Cell. 1999;31:461–530. doi: 10.1054/tice.1999.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dobrinski I, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Transplantation of germ cells from rabbits and dogs into mouse testes. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:1331–1339. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.5.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schlatt S, et al. Germ cell transfer into rat, bovine, monkey and human testes. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:144–150. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.1.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagano M, Avarbock MR, Leonida EB, Brinster CJ, Brinster RL. Culture of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Tissue Cell. 1998;30:389–397. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(98)80053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dirami G, Ravindranath N, Pursel V, Dym M. Effects of stem cell factor and granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor on survival of porcine type A spermatogonia cultured in KSOM. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:225–230. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Avarbock MR, Brinster CJ, Brinster RL. Reconstitution of spermatogenesis from frozen spermatogonial stem cells. Nature Med. 1996;2:693–696. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]