Abstract

The severity, sudden onset, and multipronged nature of the Great Recession (2007–2009) provided a unique opportunity to examine the health impacts of macroeconomic downturn. We comprehensively review empirical literature examining the relationship between the Recession and mental and physical health outcomes in developed nations. Overall, studies reported detrimental impacts of the Recession on health, particularly mental health. Macro- and individual-level employment- and housing-related sequelae of the Recession were associated with declining fertility and self-rated health, and increasing morbidity, psychological distress, and suicide, although traffic fatalities and population-level alcohol consumption declined. Health impacts were stronger among men and racial/ethnic minorities. Importantly, strong social safety nets in some European countries appear to have buffered those populations from negative health effects. This literature, however, still faces multiple methodological challenges, and more time may be needed to observe the Recession’s full health impact. We conclude with suggestions for future work in this field.

Keywords: Great Recession, economy, mental health, mortality, fertility, health behavior

INTRODUCTION

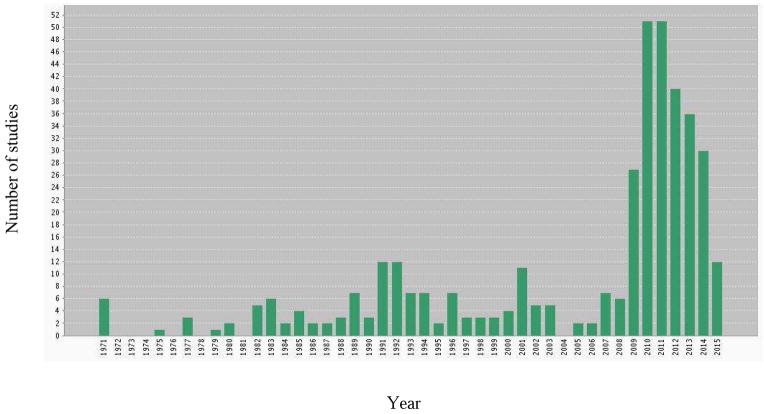

During the Great Recession of 2007–2009, the world witnessed one of the deepest and most extensive economic downturns in recent history, characterized by synchronous crises in the global financial system, employment (e.g., unemployment rose to 10% in the United States and the Europe Union [1]), and the housing market (e.g., over 15% of U.S. mortgages were either delinquent or in foreclosure by 2010 [2]). Many immediately began to question whether and how the Great Recession impacted mental and physical health. Although researchers have examined the relationship between the macroeconomy and health as far back as Durkheim’s Suicide [3], the Great Recession spurred a substantial increase in such research (Figure 1). Previous literature includes several reviews of the evidence on health effects of economic decline [4–6]; however, no existing review has focused exclusively on evidence from the Great Recession, which—due to its composition (i.e., multiple concurrent crises), severity, and global nature—may have uniquely impacted health outcomes. The current paper fills this gap by providing a comprehensive review of the literature examining the impact of the Great Recession on mental and physical health in developed nations. In addition to summarizing findings from the literature to date, we focus on three additional questions to frame our review.

Figure 1.

Number of studies identified by a search of Web of Science on “recession AND economy AND health”, July 15, 2015.

Did the housing crisis uniquely affect health?

The distinctive nature of the Recession as both a housing crisis and an unemployment crisis presents a valuable opportunity to understand how factors such as foreclosure and mortgage strain—experienced by both individual homeowners and residents of hard-hit neighborhoods—influence health. We aim to determine whether the literature is consistent with an independent effect of the housing crisis on health, above and beyond employment- or financial-related sequelae of the Recession.

How did health effects of the Recession vary within and between populations?

In the United State (U.S.), the Recession disproportionately impacted already marginalized populations. Non-Hispanic blacks (NHB), Hispanics, and those with less than a college education suffered disproportionately high unemployment compared to other groups, due in part to their greater representation in the hard-hit construction and manufacturing industries [7, 8]. Availability of subprime credit and discriminatory lending also led to higher foreclosure rates for NHBs and Hispanics and in poor and minority communities [9]. Furthermore, it is plausible that the Recession could have exacerbated existing gender-based, racial/ethnic, or social inequities in health [4, 10]. Exposure to labor and housing market recessionary factors may have differed substantially across nations due to social, political, or cultural differences [4]. The effect on health is thus likely to vary across countries based on demographic trends, social safety nets, and healthcare systems.

Do differences in aggregate- vs. individual-level findings persist?

Despite a large evidence base, prior research did not reach consensus on the nature of the relationship between the economy and health [4–6]. Whereas individual-level studies have mostly supported a relationship between job loss and worsened mental and physical health, aggregate-level (i.e., ecologic) studies have often linked rising unemployment with declines in mortality and unhealthy behaviors [4, 6, 11]. The recent literature may provide insight into whether these discrepancies between individual and aggregate findings persist in the context of a severe recession. Moreover, the rise of “multilevel” studies that examine associations between macro-level measures of economic downturn (e.g., the unemployment rate) and individual-level health outcomes may provide insight due to their ability to examine macroeconomic indicators while controlling for individual-level covariates.

OBJECTIVE

Our objective was to comprehensively review the empirical literature examining the relationship between the Great Recession and mental and physical health outcomes in developed nations. We sought to assess: 1) the unique contribution of the housing crisis to health during the Recession; 2) the presence of heterogeneity by population characteristics and geography in health effects of the Recession; and 3) the existence and degree of convergence of findings across individual, multilevel, and aggregate levels of analysis.

METHODS

In July 2015, we conducted a search of peer-reviewed journal articles using Web of Science, which includes publications from both social and medical/public health sciences. We conducted a key word search using “Great Recession”, “global financial crisis”, or “foreclosure”, and the following health outcomes: health, disease, mortality, depressi*, anxiety, distress, suicide*, cardiovascular, cancer, infection, alcohol, smoking, obesity, diet, drinking, birth, and fertility. We also identified articles by searching the National Bureau of Economic Research working paper series and all articles citing one of 4 recent reviews on the macro-economy and health [4, 5, 12, 13]. Our search identified 531 publications of which 118 met our inclusion criteria—in English, empirical, related to health outcomes, and related to the Great Recession in developed nations—based on title and abstract alone. Upon further review, we excluded an additional 34 articles that examined health services, health insurance, or internet searches and those that did not specifically examine the Recession, either by comparing Recessionary periods with earlier or later periods or by examining economic indicators primarily during the Recession (2007–2009). Studies using long time series without specifically isolating the effects of the Recession were also excluded. A total of 85 publications were included and divided into four outcome categories: reproductive and early life health (n=7), adult physical health (n=24), mental health (n=42) and health behaviors (n=20); some studies fell into >1 category.

We categorized articles by level of analysis, economic measure, and assessment of heterogeneity by demographics and geography (Table 1). We defined levels of analysis as follows: individual, if the study measured independent variables at the individual-level (e.g., job loss, financial strain, housing distress); multilevel, if the study measured independent variables at the aggregate level (e.g., the unemployment rate or pre-Recession vs. Recession time periods), but outcome variables at the individual level; and aggregate, if the study examined both independent and outcome variables at the aggregate level. This last category also included comparisons of prevalence from cross-sectional surveys conducted before and after the Recession. To inform conclusions in each outcome area, we evaluated each study on external and internal validity, defined as the degrees to which the study population represented a general population and to which findings in the study population could provide inference about the target population by limiting threats to validity from confounding, measurement, and selection biases, respectively.

Table 1.

Empirical studies of the associations between the Great Recession and mental and physical health outcomes in developed nations (n=85).

| Outcome | Level of analysis | Economic measure | Examined heterogeneity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment related1 | Housing related2 | Time period3 | Other4 | By demographics | By geography | ||

| Reproductive and early life health | |||||||

| Individual | [17] | ||||||

| Multilevel | [17] | ||||||

| Aggregate | [15, 16] | [16] | [14, 18, 19] | [20] | [14–16, 19] | [14, 15] | |

|

| |||||||

| Adult physical health | |||||||

| Self-reported Health | |||||||

| Individual | [24–27] | [21–23, 27, 35] | [21–24, 26] | [25] | |||

| Multilevel | [26, 28] | [29] | [26] | ||||

| Aggregate | [25, 30, 91] | [25, 30, 91] | [25, 30] | ||||

| General Morbidity | |||||||

| Individual | [31] | [21, 23, 27, 35] | [21, 31] | ||||

| Multilevel | [99] | [32] | |||||

| Aggregate | [34] | [30, 33] | [30, 33] | [30] | |||

| Mortality | |||||||

| Individual | [40] | ||||||

| Multilevel | [40] | ||||||

| Aggregate | [28, 36, 37, 39, 41, 97, 100] | [37, 41] | [39, 97] | [36, 37] | |||

|

| |||||||

| Mental Health | |||||||

| Psychological distress | |||||||

| Individual | [24, 26, 42–45] | [21–23, 27, 56, 57] | [101] | [21–24, 26, 44] | [44] | ||

| Multilevel | [26] | [55] | [46, 47] | [24, 26, 46, 47] | |||

| Aggregate | [30, 49, 51] | [52] | [48, 50, 53, 54] | [30, 48–50, 52, 53] | [30, 51] | ||

| Diagnosed psychiatric disorder | |||||||

| Individual | [31] | [102] | [102] | ||||

| Multilevel | |||||||

| Aggregate | [58–60, 103] | [58–60, 103] | |||||

| Suicidal behavior | |||||||

| Individual | |||||||

| Multilevel | |||||||

| Aggregate | [61, 65, 67–70] | [61, 71, 72] | [62–65, 104] | [61–63, 68, 70, 72, 104] | [61, 69, 70] | ||

|

| |||||||

| Health Behaviors | |||||||

| Alcohol | |||||||

| Individual | [26, 74–76, 78–80, 84, 105] | [74–79, 105] | [84] | [26, 74–76, 78, 79, 105] | |||

| Multilevel | [26, 83, 86] | [26, 83, 86] | |||||

| Aggregate | [81] | [80, 82] | [80, 81] | ||||

| Smoking | |||||||

| Individual | [26, 84, 85] | [84, 85] | [26] | ||||

| Multilevel | [26, 83, 86] | [26, 83, 86] | |||||

| Aggregate | [38] | [87] | [87] | ||||

| Diet/Nutrition | |||||||

| Individual | [85] | [88] | [85, 88] | [85, 88] | |||

| Multilevel | [86] | [86] | |||||

| Aggregate | [66] | ||||||

| Physical Activity | |||||||

| Individual | [26, 85, 89] | [85] | [26, 85] | ||||

| Multilevel | [26, 83, 89] | [26, 83, 89] | |||||

| Aggregate | |||||||

Studies assess individual-level job loss, the unemployment rate, and other employment-related measures

Studies assess individual-level experience of foreclosure, mortgage strain, and housing distress as well as measures of exposure to community-level foreclosure and mortgage strain.

Studies use time periods or years as exposure variable (e.g., pre-Recession vs. Recession or 2006 vs. 2008–2010)

Studies assess individual-level self-reported financial strain or change in economic resources; gross domestic product; and number of children enrolled in school lunches.

RESULTS

Reproductive and early life health (7 studies)

Fertility

Evidence suggests precipitous declines in fertility coincident with the Recession. Cherlin and colleagues [14] report an 11% decline in the total fertility rate (TFR) in the U.S. from 2007 to 2011. Although this study did not account for the pre-Recession secular decline in fertility, studies that did control for pre-Recession trends also found that rising unemployment [15, 16] as well as foreclosure rates [16] were associated with fertility declines in both the U.S. [16] and Europe [15]. Notably, all studies found stronger fertility declines among teen and younger women compared to older women [14–16], suggesting postponement of fertility, rather than overall reduction.

Birth outcomes and child health

Although limited in size and scope, this literature generally suggests negative impacts of the Recession on birth outcomes and child health. The most rigorous study of birth outcomes found that the announcement of mass layoffs (an indicator of fear or stress related to the economy) was associated with declines in birthweight even prior to actual layoffs [17]. Evidence from Spain suggested that maternal educational inequalities in adverse birth outcomes may have increased during the Recession [18]. Another study in Spain was more mixed; it found that while prevalence of child overweight/obesity increased, children’s health-related quality of life improved [19]. Both studies were based on cross-sectional data and could therefore reflect secular trends not attributable to the Recession, such as changes in demographic composition. Participation in a school lunch program, an indicator of declining household income during the Recession, was positively correlated with the prevalence of dental caries among kindergarteners [20].

Adult physical health (24 studies)

Self-Rated Health

Nearly all individual-level studies indicated that job loss, financial strain, and housing issues were associated with declines in self-rated health (SRH) during the Great Recession [21–27]. Multilevel studies also suggested that state-level unemployment as well as census-tract foreclosure risk was associated with declining SRH [26, 28, 29]. Results from most aggregate-level studies suggested a decline in SRH with the Great Recession, as well [25, 30]. The most rigorous aggregate-level study found a long-term decline in SRH after a possible brief period of improvement in the United Kingdom [30].

Morbidity

Individual, multilevel, and aggregate studies generally converged on the finding that the Recession was associated with declining physical health. Individuals in the U.S. were more likely to report a disability as well as various health symptoms (e.g., nausea, backache, diarrhea, heart burn, fatigue, sleeping problems) during the Recession [21, 23]. Incidence of diabetes among salaried workers who survived large layoffs at a multinational aluminum company increased [31]. Findings from studies examining incidence of hypertension, asthma, and tuberculosis were, however, inconsistent [27, 30–35]. Notably, some studies found that the largest morbidity effects were seen among those least vulnerable, i.e. those who remained employed [30, 31], those who held managerial or professional occupations [30], whites and the highly educated [21], and the non-homeless [33].

Mortality

All studies of mortality focused on unemployment effects, and nearly all used aggregate-level analyses. The most rigorous studies, which took into account both secular trends in mortality as well as demographic characteristics of the study populations, suggest that impacts of the Recession on mortality may have differed by age and country. Specifically, in the E.U., rising unemployment rates during the Recession were associated with declining mortality among individuals <65 years [36], while studies that looked at mortality among all age groups combined reported no effect [37,41]. In the U.S., the previously described association between rising unemployment and declining mortality appears to have tapered off before the onset of the Recession [39]. Individual and multilevel analyses also found that older individuals in the U.S. who lost their jobs during recessions faced increasing mortality risk [40]. Effects of the Recession were more marked in E.U. countries with lower expenditures on “social protection,” relative to countries with higher levels [36, 37]. Studies of cause-specific mortality indicated a decline in transportation-related mortality [36, 37] and an increase in suicide mortality [36, 37, 41].

Mental health (42 studies)

Psychological distress (defined as cases of mental disorder that may meet clinical diagnostic criteria, but more likely involve milder subclinical symptoms)

At the individual level, the loss of one’s job, income, or investment wealth stemming from the Great Recession conveyed excess risk for psychological distress in both Europe and the U.S. [24, 42–46]. Multilevel studies suggested that the psychological impact of the Recession’s onset extended beyond those who were directly affected financially, although this group suffered the most [26, 47]. At the aggregate level, inference was more mixed. Repeated cross-sectional survey data from several countries in Europe suggested that increases in rates of psychological distress were only moderate and may have been limited to adult men [30, 48–50]; European adolescents seem to have been mostly unaffected [51]. In contrast, three separate U.S. studies using national survey data reported significant population-wide increases in psychological distress [52–54]. Although these studies did not examine heterogeneity by gender or age, two analyses indicated that non-Hispanic black (NHB) and/or Hispanic individuals experienced particularly large escalations in psychological distress [26, 53]. Evidence also suggested that Americans were more adversely affected by the Recession than Europeans due to the U.S.’s lack of robust safety net programs, which may mitigate the psychological impact of job loss [44].

Cross-national differences may also stem from the housing crisis in the U.S., which appears to have been uniquely detrimental to population-level mental health. In one rigorous aggregate-level study, rising county-level foreclosure rates independently explained a small but significant portion of county-wide increases in psychological distress [52]. This association was especially pronounced in counties with high proportions of NHB and low-income residents, again suggesting that these groups were disproportionately impacted by the crisis [52]. In individual-level analyses, personally experiencing foreclosure or mortgage distress during the Recession – or living in a neighborhood that experienced large increases in foreclosure rates – also significantly increased risk for psychological distress, even after accounting for other individual- or area-level financial stressors [21–23, 27, 55–57].

Diagnosed psychiatric disorder

Evidence from aggregate-level studies using clinically diagnostic psychiatric data was largely consistent with studies of psychological distress. The most rigorous studies (i.e., those that used representative data and controlled for secular trends) reported that the prevalence of clinically diagnosable depression and anxiety significantly increased in the U.S., Europe, and East Asia during the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession [54, 58–60]. A substantial portion of the incidence of diagnosed psychiatric disorder during the Recession could be attributed to the increased rates of individual-level unemployment, financial shock, and mortgage difficulties that accompanied the Recession [58–60]. Nevertheless, excess disorder was observed in both employed and unemployed individuals [58–60].

Only two studies explicitly examined the effects of the Great Recession on diagnosed disorder at the individual level, and both used panel data from samples of working adults, limiting the external validity of their results. Study participants experienced no change in diagnosed depression after the onset of the Recession, even when the participants were continuously employed workers at a company undergoing large-scale downsizing [61, 62].

Suicidal behavior (defined as deaths due to suicide, injuries stemming from suicide attempts, and other deaths attributable to mental disorder)

In the aftermath of the Recession, suicide rates in Europe and Canada—which had been declining or stable—increased by several percentage points [62]. In the U.S., where suicide rates had already been increasing, this pace accelerated [62]. Suicide attempts and deaths due to mental disorder also increased [63–66]. The most methodologically rigorous studies in this literature (i.e., those that use decomposition techniques and/or comparison populations) concluded that rising unemployment levels were likely to be a causal determinant of many, but by no means all, excess suicide deaths observed worldwide during the Recession [61–63, 67–70]. At least in the U.S., foreclosure and other housing-related distress accounted for a portion of the remaining increase in suicide rates, over and above the effect of unemployment [67, 71, 72].

In line with previous evidence on unemployment levels and suicide [13], excess suicide deaths during the Recession have been concentrated among working-aged men [61, 63, 70, 72], who may more frequently encounter job loss and foreclosure, although the literature lacked individual-level analyses. Again, active labor market programs and social insurance appear to have substantially reduced the negative effect of unemployment on suicide rates [61, 69, 73].

Health behaviors (20 studies)

Alcohol consumption

Individuals who experienced job loss or housing distress related to the Recession tended to increase alcohol consumption and problematic drinking [74–78], particularly non-Hispanic blacks and men (compared to non-Hispanic whites and women) [74, 79]. Contrary to the individual-level evidence, multilevel and aggregate-level studies indicated that alcohol consumption and abuse declined at the population level during the Recession [26, 80–83]. Results imply that, while individuals experiencing job loss increased alcohol consumption, the larger population reduced alcohol use [80–82].

Smoking

Evidence on the relationship between the Recession and smoking was mixed. Two individual-level studies set in the Midwestern region of the U.S. found that individuals experiencing economic strain due to the Recession were more likely to smoke [84, 85]; evidence also suggested a stronger relationship between smoking and job loss among those with less education [85]. Multilevel and aggregate studies provided little evidence to support any relationship between the Recession and smoking [26, 38, 83]. A particularly rigorous multilevel study from Iceland that controlled for time-invariant confounders such as sex and risk preferences indicated that individuals smoked less during the recession than they had prior to the recession [86]. In the Netherlands, the Recession appeared to widen existing education and income inequalities in current smoking among older adults and in smoking cessation among younger adults [87].

Diet/Nutrition

The evidence linking the Recession to diet or nutrition differed by geographical context. In the U.S., greater individual-level financial strain during the crisis was associated with a lower likelihood of making healthy decisions about food [85], and increasing unemployment was associated with an increase in calories purchased at the aggregate level [66]. In Russia, there was no change in the food consumption among households experiencing income loss during the crisis [88]. In Iceland, consumption of soft drinks, sweets, and fast food increased but consumption of fruit declined during the crisis [86].

Physical Activity

Evidence examining physical activity was mixed. While individual unemployment was associated with a substantial increase in physical activity [26], increased individual-level financial strain during the recession had a negative impact on physical activity [85]. A methodologically rigorous multilevel study examined data from the American Time Use Survey and showed that, while recreational activity increased with rising unemployment rates, total physical activity declined [89].

DISCUSSION

Scholars have long sought to quantify the impact of macroeconomic downturns on physical and mental health, and our review of over 80 empirical studies indicates that this literature has expanded substantially since the onset of the Great Recession. Recent studies have examined health outcomes ranging from dental caries and physical activity to fertility and suicide and extended the literature to examine health effects of individual- and community-level housing distress and foreclosure.

Overall, studies reported detrimental impacts of the Recession on health, particularly mental health. Not only did individuals experiencing job loss, financial strain, and housing distress exhibit increased risk of psychological distress, but psychological distress, diagnosed disorder, and suicide all appeared to increase at the population level. Research consistently indicated declines in self-rated health, which likely represents a combination of mental and physical symptoms. Individuals exposed to employment, financial or housing strains were also at increased risk of physical health problems, although the literatures on any specific outcome were too sparse to draw strong conclusions. Fertility rates declined during the Recession. The literature did not support a clear impact of the Recession on mortality. Consistent with previous literature, population-level alcohol consumption declined during the Recession, despite increases in alcohol consumption among job losers. Literature on other health behaviors such as smoking, diet, and physical activity remained notably inconsistent.

The housing crisis

The housing crisis appears to have had a detrimental impact on mental health—above and beyond impacts related to unemployment or financial strain—particularly in the U.S. Findings indicated that both personal and community-level experiences of foreclosure or housing strain were associated with increases in psychological distress [21–23, 27, 55–57] and suicide rates [67, 71, 72]. Individuals experiencing housing strain or foreclosure also reported declines in SRH [21–23, 35]. Studies examining physical health impacts of the housing crisis reported conflicting results [27, 32]. Few studies attempted to separate out the unemployment- and housing-related health effects of the Recession; more research is needed to adequately answer this question.

Heterogeneity

Men were more likely than women to suffer ill physical and mental health consequences [24, 61, 63, 70, 72, 74, 89], and minority racial/ethnic groups also experienced more negative health effects [14, 26, 52, 53, 79]. Fertility declined primarily among younger women [14–16]. Less vulnerable groups, such as those who remained employed [30, 31], still experienced negative health impacts of the Recession, suggesting a possible role of stress and uncertainty apart from actual job, income, or housing loss [17, 90]. Evidence from the E.U. suggested widening inequalities in birth outcomes, smoking behavior, and SRH [18, 48, 87, 91], but further inquiry into the impact of the Recession on socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in health outcomes—especially in the U.S.—remains an important area for future research.

Levels of analysis

Literature from the Great Recession separates less clearly along levels of analysis than pre-Recession work, where findings often differed by individual- vs. aggregate-level [4–6]. We found categorizing studies as individual- or aggregate-level more complicated than in the past because multilevel studies, which were previously rare, now abound. Many studies also included analyses at multiple levels (e.g., both individual and multilevel). Findings from individual- and aggregate-level studies demonstrated some consistency, particularly with respect to the finding that psychological distress increased during the Recession. Findings on alcohol consumption consistently differ by level of analysis, as individuals who lost their jobs drank more, while the overall population drank less.

Importantly, stronger safety nets in some European countries may have buffered their populations against negative health impacts of the economic downturn or limited the widening of inequalities, a finding with strong policy implications for the U.S. [44, 91]. This finding is bolstered by research demonstrating that generosity of unemployment benefits is positively correlated with mental and self-rated health [92, 93] and reduces the association between unemployment and suicide [73]. Whether programs that assisted people experiencing mortgage distress may have offset some of the negative health effects of the housing crisis remains unknown.

Limitations to the current literature

Few studies examined the health of infants or children during the Recession, an important omission given evidence that early-life economic conditions may have lasting consequences [94]. Moreover, aside from a well-developed literature on unemployment and alcohol, the evidence on smoking, diet/nutrition, and physical activity was inconclusive, and no studies explicitly examined impacts of foreclosure on health behaviors. As health behaviors may represent mechanisms connecting the macroeconomy to mental or physical health outcomes [32], rigorous studies are needed to determine whether behaviors represent targets for intervention during economic downturns. In general, the literature lacked empirical assessments of pathways connecting the Recession to health, although mechanisms such as fear or stress [17], food insecurity, and foregone medical care [95] have been implicated.

Despite the substantial number of findings indicating negative health consequences of the Great Recession, we urge caution in the interpretation of these findings. First, we defined our exposure of interest loosely as “the Great Recession”, scholars operationalized this using a variety of variables (e.g., local unemployment or foreclosure rates; individual-level job or housing loss). It was thus challenging to summarize findings across this myriad of exposures. In fact, the Recession itself, as a source of fear and stress, may have impacts on health above and beyond the effect of any one indicator [96].

Second, internal and external validity varied substantially across the included studies. The strongest individual-level studies used longitudinal data to compare outcomes within individuals before, during, or after the Recession, to overcome the challenge of separating out health effects of economic adversity from selection effects—i.e., those with worse health are more likely to experience financial and employment problems. The most rigorous aggregate-level studies controlled for unmeasured third factors—such as changes in medical care, health insurance, and in-/out-migration that could alter population composition—and accounted for pre-Recession trends in outcomes such as fertility, suicide, and mortality. Long time series are necessary for this work, as aggregate-level estimates may be imprecise if based on <15 years of data [39]. Finally, findings from studies using non-representative samples or very specific populations (e.g., workers in one industry) may not generalize to the general population.

Third, drawing conclusions about the impacts of the Great Recession on health may still be premature. Many outcomes of interest, particularly chronic diseases, but also mental health outcomes, take many years to develop. For example, evidence shows that adults experiencing a recession their late 50s may experience reduced longevity in the long run [97], impacts that would be difficult to observe in the short time since the onset of the Great Recession.

Gaps in our review

The current review excludes research from developing nations, yet it is possible that the health effects of the Recession may have been greater in these countries, where the financial market meltdown resulted in a crisis of “food, fuel, and finance” [98]. We also excluded studies examining health care utilization, an important outcome but one that conflates changes in health status with changes in health insurance and access.

CONCLUSIONS

Our review suggests that the macro- and individual-level sequelae of the Great Recession were associated with declining fertility and self-rated health and increasing morbidity, psychological distress, and suicide, whereas traffic fatalities and population-level alcohol consumption declined. The Recession appears to have impacted the health not only of those who personally suffered job, income, or housing loss, but of the population as a whole. Associations were often strongest among men and racial/ethnic minorities. In Europe, socioeconomic inequalities in some health outcomes seem to have widened. Strong social safety nets, however, may have buffered some populations from negative health impacts of the economy. Nevertheless, we urge caution in the interpretation of findings due to methodological challenges and the fact that more time may be needed to observe some health effects of the Recession. We hope to see continued efforts at improving methods, examining the impact of the Recession on socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities, and investigating health behaviors and other potential mechanisms connecting the macroeconomy to individual health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Claire Margerison-Zilko, Sidra Goldman-Mellor, April Falconi, and Janelle Downing declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guideline

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Claire Margerison-Zilko, Email: cmargerisonzilko@epi.msu.edu.

Sidra Goldman-Mellor, Email: sgoldman-mellor@ucmerced.edu.

April Falconi, Email: afalconi@stanford.edu.

Janelle Downing, Email: jdowning@berkeley.edu.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.United Nations. The Great Recession and the jobs crisis. New York: United Nations; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fligstein N, Goldstein A. The Roots of the Great Recession. In: Grusky DB, Western B, Wimer C, editors. The Great Recession. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durkheim E. Suicide. Paris: 1897. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgard SA, Ailshire JA, Kalousova L. The Great Recession and Health: People, Populations, and Disparities. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2013;650(1):194–213. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catalano R, Goldman-Mellor S, Saxton K, Margerison-Zilko C, Subbaraman M, LeWinn K, et al. The health effects of economic decline. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011;32:431–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuckler D, Reeves A, Karanikolos M, McKee M. The health effects of the global financial crisis: can we reconcile the differing views? A network analysis of literature across disciplines. Health Econ Policy Law. 2015;10(1):83–99. doi: 10.1017/S1744133114000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hout M, Levanon A, Cumberworth E. Job Loss and Unemployment. In: Grusky DB, Western B, Wimer C, editors. The Great Recession. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoynes H, Miller DL, Schaller J. Who Suffers During Recessions? Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2012;26(3):27–47. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grusky DB, Western B, Wimer C. The Consequences of the Great Recession. In: Grusky DB, Western B, Wimer C, editors. The Great Recession. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bacigalupe A, Escolar-Pujolar A. The impact of economic crises on social inequalities in health: what do we know so far? Int J Equity Health. 2014;13 doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-13-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tapia Granados JA, House JS, Ionides EL, Burgard S, Schoeni RS. Individual joblessness, contextual unemployment, and mortality risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(3):280–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zilko CE. Economic contraction and birth outcomes: an integrative review. Hum Reprod Update. 2010;16(4):445–58. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman-Mellor SJ, Saxton KB, Catalano RC. Economic contraction and mental health. Int J Ment Health. 2010;39(2):6–31. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cherlin A, Cumberworth E, Morgan SP, Wimer C. The Effects of the Great Recession on Family Structure and Fertility. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2013;650(214) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein JR, Kreyenfeld M, Jasilioniene A, Oersal DK. Fertility reactions to the “Great Recession” in Europe: Recent evidence from order-specific data. Demogr Res. 2013;29:85–104. [Google Scholar]

- 16*.Schneider D. The Great Recession, Fertility, and Uncertainty: Evidence From the United States. J Marriage Fam. 2015;77(5):1144–56. Of importance: Schneider 2015. This study represents the most rigorous analysis of fertility during the time of the Recession. The author regressed annual, state-level general fertility rates from 2001–2012 on 1-year lagged and concurrent state economic measures, controlling for state and national secular trends, using multiple measures of the economy including annual, state unemployment, the employment-to-population ratio, foreclosure rates, the consumer confidence index, and even a measure of media coverage. Employment and foreclosure measures were all associated with declines in fertility of approximately 7–8%. [Google Scholar]

- 17*.Carlson K. Fear itself: The effects of distressing economic news on birth outcomes. J Health Econ. 2015;41:117–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.02.003. Of importance: This study is notable because of the author’s attempt to isolate the effects of fear and/or stress associated with the announcement of mass layoffs from the material effects of job loss itself. In addition, this study includes both aggregate- and individual-level analyses, the findings of which generally converge. In counties with large layoffs, average birth weight declined approximately 1–4 months prior to the layoff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juarez S, Revuelta-Eugercios BA, Ramiro-Farinas D, Viciana-Fernandez F. Maternal Education and Perinatal Outcomes Among Spanish Women Residing in Southern Spain (2001–2011) Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(8):1814–22. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajmil L, Medina-Bustos A, Fernandez de Sanmamed M-J, Mompart-Penina A. Impact of the economic crisis on children’s health in Catalonia: a before-after approach. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abasaeed R, Kranz AM, Rozier RG. The impact of the Great Recession on untreated dental caries among kindergarten students in North Carolina. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(9):1038–46. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ailshire JA. Linked lives in the “Great Recession”: personal and family econoimc stress and older adult health. Gerontologist. 2012;52:503. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgard SA, Seefeldt KS, Zelner S. Housing instability and health: Findings from the Michigan recession and recovery study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cannuscio CC, Alley DE, Pagan JA, Soldo B, Krasny S, Shardell M, et al. Housing strain, mortgage foreclosure, and health. Nursing Outlook. 2012;60(3):134–42. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drydakis N. The effect of unemployment on self-reported health and mental health in Greece from 2008 to 2013: A longitudinal study before and during the financial crisis. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reile R, Helakorpi S, Klumbiene J, Tekkel M, Leinsalu M. The recent economic recession and self-rated health in Estonia, Lithuania and Finland: a comparative cross-sectional study in 2004–2010. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(11):1072–9. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tekin E, McClellan C, Minyard K. NBER Working Papers. Cambridge MA: 2013. Health and health behaviors during the worst of times: evidence from the Great Recession. [Google Scholar]

- 27*.Yilmazer T, Babiarz P, Liu F. The impact of diminished housing wealth on health in the United States: Evidence from the Great Recession. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:234–41. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.028. Of importance: The authors evaluated not only how changes in wealth during the Recession led to changes in multiple health outcomes, but also analyzed the effects of unrealized (e.g., housing wealth, decline of asset value invested in stocks) and realized (e.g., foreclosure, unemployment, income loss) financial losses on health. Their results showed a small, but statistically significant positive correlation between housing and non-housing wealth—but not unemployment—and psychological distress and self-rated health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McInerney M, Mellor JM. Recessions and seniors’ health, health behaviors, and healthcare use: Analysis of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. J Health Econ. 2012;31(5):744–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schootman M, Deshpande AD, Pruitt SL, Jeffe DB. Neighborhood foreclosures and self-rated health among breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(1):133–41. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9929-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30*.Astell-Burt T, Feng X. Health and the 2008 Economic Recession: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Plos One. 2013;8(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056674. Of importance: The authors analyzed data collected on quarterly basis during and since the Recession, enabling the detection of changes in health outcomes during the Recession. The prevalence of poor health status improved among the unemployed in the short run but declined at the population level in the long run. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Modrek S, Cullen MR. Health consequences of the ‘Great Recession’ on the employed: Evidence from an industrial cohort in aluminum manufacturing. Soc Sci Med. 2013;92:105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.027. Of importance: This study found that the likelihood of new depression diagnoses among workers at a large manufacturing company did not change with the onset of the Recession. In combination with other studies by this group of authors (e.g., Modrek et al. 2015), this study fills an important gap in our understanding of how the Great Recession affected the mental health of workers who remained employed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arcaya M, Glymour MM, Chakrabarti P, Christakis NA, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV. Effects of Proximate Foreclosed Properties on Individuals’ Systolic Blood Pressure in Massachusetts, 1987 to 2008. Circulation. 2014;129(22):2262–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Danno K, Komukai J, Yoshida H, Matsumoto K, Koda S, Terakawa K, et al. Influence of the 2009 financial crisis on detection of advanced pulmonary tuberculosis in Osaka city, Japan: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holland DP, Person AK, Stout JE. Did the ‘Great Recession’ produce a depression in tuberculosis incidence? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(5):700–2. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pollack CE, Lynch J. Health Status of People Undergoing Foreclosure in the Philadelphia Region. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(10):1833–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toffolutti V, Suhrcke M. Assessing the short term health impact of the Great Recession in the European Union: A cross-country panel analysis. Preventive Medicine. 2014;64:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumbach A, Gulis G. Impact of financial crisis on selected health outcomes in Europe. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(3):399–403. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallus S, Ghislandi S, Muttarak R. Effects of the economic crisis on smoking prevalence and number of smokers in the USA. Tob Control. 2015;24(1):82–8. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruhm CJ. Recessions, healthy no more? J Health Econ. 2015;42:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noelke C, Beckfield J. Recessions, Job Loss, and Mortality Among Older US Adults. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):E126–E34. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mattei G, Ferrari S, Pingani L, Rigatelli M. Short-term effects of the 2008 Great Recession on the health of the Italian population: an ecological study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(6):851–8. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0818-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brenner MH, Andreeva E, Theorell T, Goldberg M, Westerlund H, Leineweber C, et al. Organizational Downsizing and Depressive Symptoms in the European Recession: The Experience of Workers in France, Hungary, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Plos One. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hyclak TJ, Meyerhoefer CD, Taylor LW. Older Americans’ health and the Great Recession. Rev Econ Househ. 2015;13(2):413–36. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Riumallo-Herl C, Basu S, Stuckler D, Courtin E, Avendano M. Job loss, wealth and depression during the Great Recession in the USA and Europe. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(5):1508–17. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Urbanos-Garrido RM, Lopez-Valcarcel BG. The influence of the economic crisis on the association between unemployment and health: an empirical analysis for Spain. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(2):175–84. doi: 10.1007/s10198-014-0563-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McInerney M, Mellor JM, Nicholas LH. Recession depression: Mental health effects of the 2008 stock market crash. J Health Econ. 2013;32(6):1090–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sargent-Cox K, Butterworth P, Anstey KJ. The global financial crisis and psychological health in a sample of Australian older adults: A longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(7):1105–12. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bartoll X, Palencia L, Malmusi D, Suhrcke M, Borrell C. The evolution of mental health in Spain during the economic crisis. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(3):415–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buffel V, van de Straat V, Bracke P. Employment status and mental health care use in times of economic contraction: a repeated cross-sectional study in Europe, using a three-level model. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14 doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0153-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katikireddi SV, Niedzwiedz CL, Popham F. Trends in population mental health before and after the 2008 recession: a repeat cross-sectional analysis of the 1991–2010 Health Surveys of England. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pfoertner T-K, Rathmann K, Elgar FJ, de Looze M, Hofmann F, Ottova-Jordan V, et al. Adolescents’ psychological health complaints and the economic recession in late 2007: a multilevel study in 31 countries. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(6):961–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Houle JN. Mental health in the foreclosure crisis. Soc Sci Med. 2014;118:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lo CC, Cheng TC. Race, unemployment rate, and chronic mental illness: a 15-year trend analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(7):1119–28. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0844-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehta K, Kramer H, Durazo-Arvizu R, Cao G, Tong L, Rao M. Depression in the US Population During the Time Periods Surrounding the Great Recession. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(4):E499–E504. doi: 10.4088/JCP.14m09637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cagney KA, Browning CR, Iveniuk J, English N. The Onset of Depression During the Great Recession: Foreclosure and Older Adult Mental Health. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):498–505. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McLaughlin KA, Nandi A, Keyes KM, Uddin M, Aiello AE, Galea S, et al. Home foreclosure and risk of psychiatric morbidity during the recent financial crisis. Psychol Med. 2012;42(7):1441–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Osypuk TL, Caldwell CH, Platt RW, Misra DP. The Consequences of Foreclosure for Depressive Symptomatology. Ann Epidemiol. 2012;22(6):379–87. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2012.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Economou M, Madianos M, Peppou LE, Patelakis A, Stefanis CN. Major depression in the Era of economic crisis: A replication of a cross-sectional study across Greece. J Affect Disord. 2013;145(3):308–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gili M, Roca M, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(1):103–8. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cks035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee S, Guo W-j, Tsang A, Mak ADP, Wu J, Ng KL, et al. Evidence for the 2008 economic crisis exacerbating depression in Hong Kong. J Affect Disord. 2010;126(1–2):125–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reeves A, McKee M, Gunnell D, Chang S-S, Basu S, Barr B, et al. Economic shocks, resilience, and male suicides in the Great Recession: cross-national analysis of 20 EU countries. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(3):404–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cku168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reeves A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Economic suicides in the Great Recession in Europe and North America. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(3):246–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.144766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Corcoran P, Griffin E, Arensman E, Fitzgerald aP, Perry IJ. Impact of the economic recession and subsequent austerity on suicide and self-harm in Ireland: An interrupted time series analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2015:969–77. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Vogli R, Marmot M, Stuckler D. Excess suicides and attempted suicides in Italy attributable to the great recession. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(4) doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-201607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.De Vogli R, Vieno A, Lenzi M. Mortality due to mental and behavioral disorders associated with the Great Recession (2008–10) in Italy: a time trend analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(3):419–21. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ng SW, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Turning point for US diets? Recessionary effects or behavioral shifts in foods purchased and consumed(1–3) Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(3):609–16. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.072892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67*.DeFina R, Hannon L. The Changing Relationship Between Unemployment and Suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(2):217–29. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12116. Of importance: This study uses a long time series (1979–2010) and rigorous statistical methods to conclude that the Great Recession led to an increase in suicide rates, but that higher unemployment levels were only partly responsible. The authors frame their analysis within the broad context of the long-term relationship between unemployment and suicide in the U.S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gemmill A, Falconi A, Karasek D, Hartig T, Anderson E, Catalano R. Do macroeconomic contractions induce or ‘harvest’ suicides? A test of competing hypotheses. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015 doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-205489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Norstrom T, Gronqvist H. The Great Recession, unemployment and suicide. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(2):110–6. doi: 10.1136/jech-2014-204602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Phillips JA, Nugent CN. Suicide and the Great Recession of 2007–2009: The role of economic factors in the 50 US states. Soc Sci Med. 2014;116:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fowler KA, Gladden RM, Vagi KJ, Barnes J, Frazier L. Increase in Suicides Associated With Home Eviction and Foreclosure During the US Housing Crisis: Findings From 16 National Violent Death Reporting System States, 2005–2010. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):311–6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72*.Houle JN, Light MT. The Home Foreclosure Crisis and Rising Suicide Rates, 2005 to 2010. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1073–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301774. Of importance: The authors rigorously assessed the independent effect of the home foreclosure crisis on suicide rates in the U.S., and found that state-level foreclosure rates were positively associated with suicide rates overall but especially among the middle-aged. Results controlled for the effect of state-level unemployment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cylus J, Glymour MM, Avendano M. Do Generous Unemployment Benefit Programs Reduce Suicide Rates? A State Fixed-Effect Analysis Covering 1968–2008. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;180(1):45–52. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mulia N, Zemore SE, Murphy R, Liu H, Catalano R. Economic Loss and Alcohol Consumption and Problems During the 2008 to 2009 U. S. Recession. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(4):1026–34. doi: 10.1111/acer.12301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Richman JA, Brown RL, Rospenda KM. The great recession and drinking outcomes: protective effects of politically oriented coping. J Addict. 2014;2014:646451. doi: 10.1155/2014/646451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Richman JA, Rospenda KM, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Vijayasira G, Cloninger L, et al. Drinking in the age of the Great Recession. J Affect Disord. 2012;31(2):158–72. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.665692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Murphy RD, Zemore SE, Mulia N. Housing Instability and Alcohol Problems during the 2007–2009 US Recession: the Moderating Role of Perceived Family Support. J Urban Health. 2014;91(1):17–32. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9813-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vijayasiri G, Richman JA, Rospenda KM. The Great Recession, somatic symptomatology and alcohol use and abuse. Addict Behav. 2012;37(9):1019–24. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zemore SE, Mulia N, Jones-Webb RJ, Liu H, Schmidt L. The 2008–2009 Recession and Alcohol Outcomes: Differential Exposure and Vulnerability for Black and Latino Populations. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74(1):9–20. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bor J, Basu S, Coutts A, McKee M, Stuckler D. Alcohol Use During the Great Recession of 2008–2009. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48(3):343–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cotti C, Tefft N. Decomposing the Relationship between Macroeconomic Conditions and Fatal Car Crashes during the Great Recession: Alcohol- and Non-Alcohol-Related Accidents. B E J Econom Anal Policy. 2011;11(1) [Google Scholar]

- 82.Harhay MO, Bor J, Basu S, McKee M, Mindell JS, Shelton NJ, et al. Differential impact of the economic recession on alcohol use among white British adults, 2004–2010. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24(3):410–5. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nandi A, Charters TJ, Strumpf EC, Heymann J, Harper S. Economic conditions and health behaviours during the ‘Great Recession’. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(12):1038–46. doi: 10.1136/jech-2012-202260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kalousova L, Burgard SA. Unemployment, measured and perceived decline of economic resources: Contrasting three measures of recessionary hardships and their implications for adopting negative health behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2014;106:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Macy JT, Chassin L, Presson CC. Predictors of health behaviors after the economic downturn: A longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2013;89:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86*.Ásgeirsdóttir TLCH, Noonan K, Reichman N. NBER Working Papers. Cambridge MA: 2015. Lifecycle Effects of a Recession on Health Behaviors: Boom, Bust, and Recovery in Iceland. Of importance: This study used individual-level longitudinal data from Iceland collected prior to and after the major economic crisis in that country. By using an individual-fixed effects approach combined with individual-level covariates, the analysis controls for both unobserved time-invariant and observed time-varying potential confounders. The authors found that the economic crisis contributed to reductions in both health-compromising and health-promoting behaviors such as smoking, binge drinking, and consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Benson FE, Kuipers MAG, Nierkens V, Bruggink J-W, Stronks K, Kunst AE. Socioeconomic inequalities in smoking in The Netherlands before and during the Global Financial Crisis: a repeated cross- sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15 doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1782-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88*.Nikoloski Z, Ajwad MI. Do economic crises lead to health and nutrition behavior responses?: Analysis using longitudinal data from Russia. Policy Research Working Paper - World Bank. 2013;6538:31. Of importance: A study with longitudinal data from Russian families from 2007 to 2010 used a semi-parametric difference in difference strategy with propensity score matching. The study finds that indicators of household health and nutritional behavior do not differ between households experiencing an income loss of >30% during the crisis and those experiencing smaller or no losses. [Google Scholar]

- 89*.Colman G, Dave D. Exercise, physical activity, and exertion over the business cycle. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.032. Of importance: This study utilized data from the American Time Use Survey to investigate whether the local-area employment rate affected use of time on exercise through either an individual’s own change in employment or through an intra-household spillover. The authors report that, as work time decreases, recreational exercise (as well as TV-watching, sleeping, childcare, and housework) increase. These findings are strongest in low educated men, and because recreational activity does not offset work-related physical activity, total physical activity declines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Catalano R, Serxner S. The effect of ambient threats to employment on low birth weight. J Health Soc Behav. 1992;33(4):363–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Copeland A, Bambra C, Nylen L, Kasim A, Riva M, Curtis S, et al. All in it together? The effects of recession on population health and health inequalities in England and Sweden, 1991–2010. Int J Health Serv. 2015;45(1):3–24. doi: 10.2190/HS.45.1.b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cylus J, Glymour MM, Avendano M. Health Effects of Unemployment Benefit Program Generosity. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):317–23. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.O’Campo P, Molnar A, Ng E, Renahy E, Mitchell C, Shankardass K, et al. Social welfare matters: A realist review of when, how, and why unemployment insurance impacts poverty and health. Soc Sci Med. 2015;132:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van den Berg GJ, Lindeboom M, Lopez M. Inequality in individual mortality and economic conditions earlier in life. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(9):1360–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Burgard SA, Hawkins JM. Race/Ethnicity, Educational Attainment, and Foregone Health Care in the United States in the 2007–2009 Recession. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):E134–E40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ruhm CJ. NBER Working Paper Series. Cambridge MA: 2015. Health effects of economic crises. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Coile CC, Levine PB, McKnight R. Research NBoE, editor. Recessions, older workers, and longevity: how long are recession good for your health? Cambridge, MA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bank W. Global Monitoring Report. Washington DC: World Bank; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 99.O’Brien RL. Economy and Disability: Labor Market Conditions and the Disability of Working-Age Individuals. Soc Probl. 2013;60(3):321–33. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang Q. The Effects of Unemployment Rate on Health Status of Chinese People. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44(1):28–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Modrek S, Hamad R, Cullen MR. Psychological Well-Being During the Great Recession: Changes in Mental Health Care Utilization in an Occupational Cohort. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):304–10. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Malard L, Chastang J-F, Niedhammer I. Changes in major depressive and generalized anxiety disorders in the national French working population between 2006 and 2010. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dagher RK, Chen J, Thomas SB. Gender Differences in Mental Health Outcomes before, during, and after the Great Recession. Plos One. 2015;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kaplan MS, Huguet N, Caetano R, Giesbrecht N, Kerr WC, McFarland BH. Economic contraction, alcohol intoxication and suicide: analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Inj Prev. 2015;21(1):35–41. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2014-041215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Brown RL, Richman JA, Rospenda KM. Economic Stressors and Alcohol-Related Outcomes: Exploring Gender Differences in the Mediating Role of Somatic Complaints. J Addict Dis. 2014;33(4):303–13. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2014.969604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]