Summary

Kyrgyzstan reported 77.5 new cases of human brucellosis per 100,000 inhabitants in 2007, which is one of the highest incidences in the world. However, because this number is based on official records, it is very likely that the incidence is underreported. The diagnostic tests most commonly used in Kyrgyzstan are the Rose Bengal test in ruminants and the Huddleson test in humans. The sensitivity and specificity of these tests have never been evaluated under field conditions in Kyrgyzstan, where the strains circulating in livestock and humans are unknown. Therefore, a representative national cross-sectional serological study was undertaken in humans, cattle, sheep and goats to assess the true seroprevalence and to compare different serological tests. In the year of study (2006), few animals were vaccinated against brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan. A total of 5,229 livestock sera and 1,777 human sera from three administrative regions were collected during spring 2006 and submitted to a range of serological tests. The true seroprevalence of brucellosis, estimated using Bayesian methodology, was 7% (95% credibility interval 4%–9%) in humans, 3% (1%–5%) in cattle, 12% (7%–23%) in sheep and 15% (7%–30%) in goats. The Rose Bengal test was confirmed as a useful screening test in livestock and humans, although its sensitivity was lower than that of other tests. The estimates of specificity of all tests were significantly higher than those for sensitivity. The high seroprevalence of brucellosis in humans, cattle and small ruminants in Kyrgyzstan was confirmed. Bayesian statistical approaches were demonstrated to be useful for simultaneously deriving test characteristics and true prevalence estimates in the absence of a gold standard.

Keywords: Animal, Bayesian model, Brucellosis, Human, Kyrgyzstan, Serology, True seroprevalence, Zoonosis

Introduction

Brucellosis is a bacterial disease of livestock with a high zoonotic impact. Its transmission to humans occurs mainly by the consumption of raw dairy products and by direct contact with the skin or mucosa during parturition and abortion. Cattle (Bos taurus) are natural hosts for Brucella abortus, and sheep (Ovis aries) and goats (Capra hircus) for B. melitensis and B. ovis. Humans are susceptible to both B. abortus and B. melitensis, the latter being most frequently reported in humans (1).

Brucellosis occurs worldwide, particularly in developing and transition countries, but it is well controlled in developed countries. Kyrgyzstan has one of the highest incidences of brucellosis in the world, with 36 reported human cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2002 (2) and 77.5 per 100,000 in 2007 (promedmail.org, Archive Number 20090201.0449, published 1 Feb., 2009). However, it is not known whether the coverage of the Kyrgyz health reporting system is exhaustive and whether all patients have been recorded. It is very likely that the true incidence is underestimated.

Brucellosis can be diagnosed directly by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or isolation (culture) of the bacteria, or indirectly by antibody detection either in serum or milk (1). The direct Brucella culture method proves the existence of the agent in a suspicious sample, but this method of diagnosis is complex and requires a biosafety level 3 laboratory, which is rarely available in the countries where brucellosis is endemic. Hence, serological methods are routinely used for diagnosis in these countries.

Several commercial serological tests are available for humans and animals (1, 3, 4). The Rose Bengal test (RBT) has been recommended as a suitable screening test at the national or local level for diagnosis of brucellosis in animals (1); enzyme-linked immunoassays (ELISA) and the fluorescent polarisation assay (FPA) have recently been added as prescribed tests. They are fairly simple, but robust, tests which can be conducted with a minimum of equipment and are therefore also suitable for smaller laboratories (1, 4). Further serological tests (e.g. the Coombs’ test, the serum or plate agglutination test and the immunocapture test) are available, and have specific advantages and disadvantages (1, 3).

For diagnosis of brucellosis in humans, the RBT is recommended as a sensitive screening test, but decisions regarding clinical treatment may require additional confirmatory methods, and specifically strain culture (1). Information on the characteristics (sensitivity and specificity) of the serological tests differs significantly between publications, and this problem is increased if the tests are not applied according to international standards such as the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) recommendations (4). In Kyrgyzstan, the tests most commonly used are the so-called Huddleson test for humans and the RBT for animals. The Huddleson test is a plate agglutination test based on the RBT principle but with serial dilution of the sample: a result is defined as positive when agglutination is observed above a defined dilution (5). Although the Huddleson and RBT are both agglutination tests used for screening that do not involve quantitative serum dilution, the latter is performed at acidic pH and is not susceptible to the prozone effect (I. Moriyón, personal communication).

When a diagnostic test’s sensitivity or specificity is below 100%, the distortion (bias) has to be accounted for when estimating the true seroprevalence. The Rogan–Gladen estimator is a possible approach that can be used under the condition that both sensitivity and specificity are known (6). This frequentist statistical approach has been applied in several studies (7, 8, 9). However, when the test characteristics are unknown or the expected seroprevalence is low (<5%) this estimator cannot be used. For situations where specific knowledge on test characteristics is lacking but some preliminary information is available, Bayesian methods have been proposed. Several studies have been published describing the use of Bayesian models to estimate prevalence or test characteristics in veterinary medicine (7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15).

In Kyrgyzstan, exact knowledge of the epidemiology of brucellosis, including its prevalence, is lacking. The characteristics of the Huddleson and Rose Bengal tests, which are currently used in Kyrgyzstan, have never been evaluated under field conditions and are therefore unknown in this setting. The overall objective of this study was to assess the seroprevalence of brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan in a representative sample of livestock and humans and to evaluate the association between apparent seroprevalence values in humans and livestock. The latter was addressed in an accompanying study (16). In the present study the authors used Bayesian models to: a) compare the characteristics of the six applied serological tests without a gold standard, and b) estimate the true seroprevalence of brucellosis within the human, cattle, sheep and goat populations in Kyrgyzstan, taking into account test sensitivity and specificity.

Materials and methods

Dataset (serum samples and population size)

The assessment of human and livestock seroprevalence was planned in an integrated way (17). Serum samples were collected from humans, cattle, sheep and goats during a broad cross-sectional study in spring 2006, which aimed to estimate the seroprevalence of brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan. The sampling procedures are described in detail elsewhere (16). Briefly, a multistage cluster sample, proportional to the size of the small ruminant population, was drawn by levels of oblast (administrative region): Province (n = 3), Rayon (district, n = 9) and Village (n = 90). A total sample size of 1,800 per species was calculated to achieve an absolute precision for the 95% confidence limits of < 3% below and above the estimated seroprevalence. Blood was obtained by venepuncture from humans and livestock (cattle, sheep and goats) into 5 ml and 10 ml Vacutainer® tubes, respectively. The samples were transported to the Rayon health centres (human samples) and veterinary laboratories (livestock samples) and centrifuged. Tubes containing 2 ml of serum were kept at the Rayon veterinary laboratories for testing with the RBT (Kherson Bio-Factory, Ukraine; for test description see next section). In addition, portions of all sera were shipped to Bishkek, either to the Centre for Quarantine for human samples or to the Central Veterinary Laboratory for livestock samples, and used in the tests described below.

Data on the population sizes of humans, cattle and small ruminants (sheep and goats) were retrieved from official records for 2006 (www.fao.org/ag/AGP/AGPC/doc/Counprof/kyrgi.htm). In the year of study very few animals were vaccinated against brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan and their influence on the serological results of this study was considered negligible.

Diagnostic tests

The samples were submitted to a range of serological diagnostic tests (Table I). Human sera were subjected to the Huddleson test, the RBT (Bio-Rad Laboratories®), and an immunoglobulin (Ig)G and IgM ELISA (Chekit®, IDEXX Laboratories Inc.) with anti-human goat IgG and IgM conjugates (Sigma-Aldrich Co.). Human sera that were positive in the Huddleson or the RBT test, but negative in the IgG ELISA, were further subjected to the IgM ELISA, and overall classification of the ELISA was positive if the IgG ELISA and/or the IgM ELISA was positive.

Table I. Total sample size over all Rayons by species and number of samples examined with different diagnostic tests in a seroprevalence survey of brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan in 2006.

| Species | Total no. of samples | RBT (Bio-Rad) | RBT (Ukraine) | ELISA (ruminant) (a) | ELISA IgG (human) (b) | ELISA IgM (human) (c) | FPA | Huddleson test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | 1,818 | 737 | 1,560 | 1,698 | ND | ND | 1,691 | ND |

| Sheep | 2,101 | 761 | 1,853 | 2,027 | ND | ND | 2,029 | ND |

| Goats | 1,310 | 764 | 1,082 | 1,209 | ND | ND | 1,176 | ND |

| Humans | 1,777 | 644 | ND | ND | 1,762 | 369 | 253 | 1,774 |

FPA: fluorescence polarisation assay

ND: not determined

RBT: Rose Bengal test

Indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detecting immunoglobulin G in ruminants

Indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detecting immunoglobulin G in humans

Indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detecting immunoglobulin M in humans

Livestock sera were tested using the RBT test from the Kherson Bio-Factory, Ukraine, which is commonly used for livestock samples in Kyrgyzstan. Additionally, livestock sera were tested using an indirect ELISA for ruminants (Chekit®, IDEXX Laboratories Inc.) and the fluorescence polarisation assay (Brucella FPA®, Diachemix, LLC). Serological test results were interpreted according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The cut-off value of the FPA was set at 90 mP (millipolarisation level), and those for the other tests were set using a titration curve, analogous to previous studies (18, 19). Doubtful test results (0% to 5.6% of the test results, depending on the test, and 10.2% in the IgG ELISA for human samples) were handled as positive. This assumption was based on the consideration that the objective was disease detection (screening).

Bayesian model to estimate test characteristics and true seroprevalence

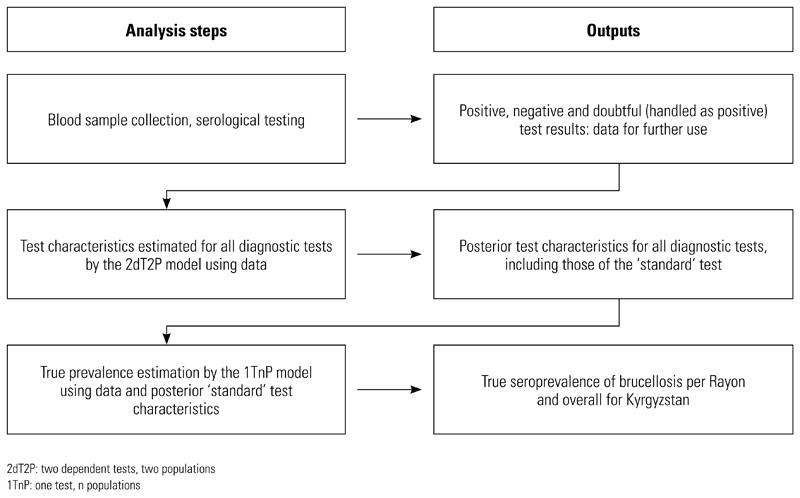

Given that none of the diagnostic tests utilised can be considered a gold standard with perfect diagnostic sensitivity and specificity, the authors used two Bayesian models to derive estimates for: (a) the true seroprevalence (i.e. the seroprevalence taking into account test characteristics below 100%) in the sample population, and (b) the respective diagnostic test characteristics. The work flow of the data analysis steps and their output is depicted in Figure 1. In the first step, test characteristics of all relevant diagnostic tests were estimated in a ‘two dependent tests, two populations’ model (2dT2P model). Posterior test characteristics of the ‘standard’ tests estimated from this model were further incorporated into the ‘one test, n populations’ model (1TnP model) to estimate an overall and Rayon-specific true seroprevalence. In this context, the most common diagnostic test for brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan (Huddleson for humans, RBT for animals) was defined as the ‘standard’ because it is considered to be the reference approach by the Kyrgyz public health and veterinary authorities. Separate Bayesian analyses were conducted for each of the four species in the study.

Fig. 1. Flow chart of analysis steps and their outputs in a seroprevalence estimation survey of brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan in 2006.

As ‘standard’ tests the Huddleson test was used for humans, the Rose Bengal test (Ukraine) for livestock

The Bayesian models were implemented in the WinBUGS software version 3.0.3 (mathstat.helsinki.fi/openbugs/SoftwareFrames.html) environment, which uses Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling; the routines were based on published modules (20). In these routines, prior information on test characteristics and disease seroprevalence, mostly described as probability distributions, is combined with the observed data (test results from the respective individuals) to derive posterior density distributions of the parameters of interest. The reported model outcomes were the medians and variation (2.5th and 97.5th percentiles, representing the 95% credibility interval) of the posterior parameter distribution. For each estimate, 100,000 iterations were run; the first 10,000 iterations (burn-in phase) were discarded and not used for calculation of the posterior values. The influence on the posterior estimates of both the prior distributions and the starting values (inits) were tested in a sensitivity analysis.

First step: estimation of diagnostic test characteristics by the ‘two dependent tests, two populations’ model

The sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic tests were estimated by a 2dT2P model described by Branscum et al. and Georgiadis et al. (11, 21). The authors employed the model with conditionally dependent tests because all tests were based on serology. The correlation of the two tests is expressed as λ and γ, where λd+ and λd− reflect the probability of having the same positive and negative results, respectively. The probabilities of contradictory test results are given by γd+ (test 2 positive and test 1 negative) and γd− (test 2 negative and test 1 positive). Details of the conditional dependence of the two tests are described elsewhere (13, 21). Because no prior information from the literature was available for the two correlation parameters, the authors defined a relatively wide (unspecific) beta-distribution for both λ and γ with a mode of 0.7 and 5th percentile of 0.1, using the freeware tool BetaBuster (22).

The prior distribution mode of one test’s sensitivity and specificity was taken from the literature and a relatively wide beta-distribution was determined for variability (Table II). Two subpopulations with distinctly different assumed prevalence were defined by the result of a third diagnostic test, with third-test-positive individuals and third-test-negative individuals belonging to the proposed high and low prevalence populations, respectively. The prior distributions of both the low and the high seroprevalence populations again were defined to be rather wide (the 95th percentile of the high seroprevalence population was set at 0.8 and that of the low seroprevalence population at 0.15), with modes of 0.3 and 0.03 respectively, for all species (Table II).

Table II. Mode, limit and related beta-distribution values (α, β) of the prior test characteristics for the ‘two dependent tests, two populations’ (2dT2P) model in a seroprevalence survey of brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan in 2006.

| Test | Test characteristic | Mode | Source | 95% sure that value is | α | β |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | ||||||

| FPA | Se | 0.95 | (12, 23, 24) | > 0.8 | 21.2 | 2.1 |

| Sp | 0.98 | > 0.8 | 15.8 | 1.3 | ||

| ELISA (ruminant) | Se | 0.96 | (23) | > 0.8 | 19.1 | 1.8 |

| Sp | 0.94 | > 0.8 | 23.8 | 2.5 | ||

| Sheep | ||||||

| FPA | Se | 0.93 | (3, 25) | > 0.5 (a) | 5.1 | 3.0 |

| Sp | 0.98 | > 0.5 (a) | 4.5 | 1.1 | ||

| ELISA (ruminant) | Se | 0.95 | (3, 26, 27) | > 0.5 (a) | 4.8 | 1.2 |

| Sp | 0.99 | > 0.5 (a) | 4.4 | 1.0 | ||

| Goats | ||||||

| FPA | Se | 0.93 | (3, 25) | > 0.8 | 27.0 | 3.0 |

| Sp | 0.98 | > 0.8 | 15.8 | 1.3 | ||

| ELISA (ruminant) | Se | 0.80 | (3, 28, 29) | > 0.65 | 24.1 | 6.8 |

| Sp | 0.99 | > 0.8 | 14.5 | 1.1 | ||

| Humans | ||||||

| ELISA (human) | Se | 0.87 | (30, 31, 32, 33) | > 0.7 | 19.5 | 3.8 |

| Sp | 0.99 | > 0.85 | 20.6 | 1.2 | ||

| RBT (Bio-Rad) | Se | 0.95 | (1, 30, 32, 34, 35) | > 0.8 | 21.2 | 2.1 |

| Sp | 0.95 | > 0.8 | 21.2 | 2.1 | ||

| All species | ||||||

| P low (b) | 0.03 | > 0.15 | 1.8 | 26.7 | ||

| P high (c) | 0.30 | < 0.80 | 1.5 | 2.3 | ||

| λD+ | 0.70 | > 0.10 | 1.376 | 1.161 | ||

| λD− | 0.70 | > 0.10 | 1.376 | 1.161 | ||

| γD+ | 0.70 | > 0.10 | 1.376 | 1.161 | ||

| γD− | 0.70 | > 0.10 | 1.376 | 1.161 | ||

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

FPA: fluorescence polarisation assay

RBT: Rose Bengal test

Se: sensitivity

Sp: specificity

See results of sensitivity analysis for justification of wider prior distribution

Seroprevalence of the population with low seroprevalence

Seroprevalence of the population with high seroprevalence

The different combinations of diagnostic tests which were included in the model, together with the number of positive and negative samples for each test combination, are presented in Table III. This table also lists the third tests, which defines the high and low seroprevalence sub-populations. For the RBT (Ukraine) and the Huddleson tests, where two estimates from different combinations were available, the arithmetic average of the posterior values was used for the second model step.

Table III. Tests of interest for test characteristics and their applied combinations in the ‘two dependent tests, two populations’ (2dT2P) model in a seroprevalence survey of brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan in 2006.

| Cattle | Positive | Negative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Third test for sub-population allocation: RBT (Ukraine) | ELISA (ruminant) | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| FPA | Positive | 18 | 0 | 11 | 47 |

| Negative | 9 | 5 | 98 | 1,230 | |

| Third test for sub-population allocation: ELISA (ruminant) | FPA | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| RBT (Ukraine) | Positive | 18 | 9 | 0 | 5 |

| Negative | 11 | 98 | 47 | 1,230 | |

| Third test for sub-population allocation: FPA | ELISA (ruminant) | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| RBT (Ukraine) | Positive | 18 | 0 | 9 | 5 |

| Negative | 11 | 47 | 98 | 1,230 | |

| Sheep | Positive | Negative | |||

| Third test for sub-population allocation: RBT (Ukraine) | ELISA (ruminant) | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| FPA | Positive | 26 | 18 | 41 | 128 |

| Negative | 13 | 18 | 83 | 1,481 | |

| Third test for sub-population allocation: ELISA (ruminant) | FPA | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| RBT (Ukraine) | Positive | 26 | 13 | 18 | 18 |

| Negative | 41 | 83 | 128 | 1,481 | |

| Third test for sub-population allocation: FPA | ELISA (ruminant) | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| RBT (Ukraine) | Positive | 26 | 18 | 13 | 18 |

| Negative | 41 | 128 | 83 | 1,481 | |

| Goats | Positive | Negative | |||

| Third test for sub-population allocation: RBT (Ukraine) | ELISA (ruminant) | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| FPA | Positive | 15 | 25 | 18 | 64 |

| Negative | 10 | 33 | 40 | 715 | |

| Third test for sub-population allocation: ELISA (ruminant) | FPA | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| RBT (Ukraine) | Positive | 15 | 10 | 25 | 33 |

| Negative | 18 | 40 | 64 | 715 | |

| Third test for sub-population allocation: FPA | ELISA (ruminant | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| RBT (Ukraine) | Positive | 15 | 25 | 10 | 33 |

| Negative | 18 | 64 | 40 | 715 | |

| Humans | Positive | Negative | |||

| Third test for sub-population allocation: Huddleson | ELISA (human) | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| RBT | Positive | 85 | 10 | 5 | 8 |

| (Bio-Rad) | Negative | 66 | 58 | 94 | 318 |

| Third test for sub-population allocation: RBT (Bio-Rad) | ELISA (human) | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| Huddleson | Positive | 85 | 10 | 66 | 58 |

| Negative | 5 | 8 | 94 | 318 | |

| Third test for sub-population allocation: ELISA (human) | RBT (Bio-Rad) | ||||

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | ||

| Huddleson | Positive | 85 | 66 | 10 | 58 |

| Negative | 5 | 94 | 8 | 318 | |

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

FPA: fluorescent polarisation assay

RBT: Rose Bengal test

Second step: estimation of the true seroprevalence by the Bayesian ‘one test, n populations’ model

To estimate the seroprevalence per Rayon and the overall seroprevalence of brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan by species, specific 1TnP models were employed as described elsewhere (12, 36). Data from the country’s standard diagnostic test (‘one test’), stratified by the Rayons (n = 9) (‘n populations’), were integrated into the model.

The prior distribution of the test characteristics was transformed from the 2dT2P model’s posterior values. The seroprevalence pi of Rayon i was estimated by

| (1) |

where infi denotes a Bernoulli distribution of τ, which reflects the probability of a seroprevalence unequal to 0, i.e. the probability of the presence of brucellosis, and is described as a beta-distribution. The prior value of τ was set very close to 1, because the possibility of freedom from brucellosis in the Rayons can be neglected; ϖ is a beta-distribution of the parameters a and b, which were calculated using

| (2) |

| (3) |

In these equations, μ is beta-distributed and reflects the prior value of the average seroprevalence in the populations (12). For μ, the authors assumed a mode of 0.15 (the mean of the prior values of the low [0.03] and high [0.3] prevalence populations, respectively) with a 95% certainty that μ was smaller than 0.52. The φ is expressed as a gamma-distribution and is based on the estimated upper percentile of the seroprevalence distribution, as well as on a given certainty that this upper percentile is not exceeded (12, 36). Here, the authors were 99% sure that the seroprevalence was lower than 0.5 for all Rayons and all species. The prior distribution values of the 1TnP model are presented in Table IV.

Table IV. Parameters (α, β) of the prior beta-distribution values of the ‘one test, n population’ (1TnP) model in a seroprevalence survey of brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan in 2006.

| Species | α | β | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test sensitivity(a),(b) | Cattle | 11.0 | 5.5 | Transformation from Table VI |

| Sheep | 12.1 | 14.6 | by BetaBuster | |

| Goats | 14.9 | 12.4 | ||

| Humans | 45.9 | 4.4 | ||

| Test specificity(a),(b) | Cattle | 560.7 | 6.7 | Transformation from Table VI |

| Sheep | 464.6 | 6.6 | by BetaBuster | |

| Goats | 436.0 | 23.9 | ||

| Humans | 159.5 | 33.5 | ||

| τ (b) | All | 15.8 | 1.3 | Assumption |

| φ (c) | All | 4.524 | 0.387 | (11) |

| μ (b) | All | 1.83 | 5.71 | (11) |

Rose Bengal test (Ukraine) for cattle, sheep, goats; Huddleson for humans

Beta-distribution

Gamma-distribution

To estimate the overall true seroprevalence (TPov) in the sampled regions of Kyrgyzstan, the authors calculated Rayon-specific seroprevalences (pi) weighted on the Rayon’s population size (Ni) from

| (4) |

TPov was calculated from equation (4), implemented in WinBUGS; hence, the credibility interval of TPov was influenced by the credibility intervals of each pi.

Sensitivity analyses of the Bayesian models

For both applied Bayesian models a sensitivity analysis was conducted by examining the dependence of the posterior values (median and 95% credibility intervals) on both the prior values (mode and variability) and the inits (starting values). To evaluate the dependence on the prior values, the authors ran the model with a varying range of the distributions but a fixed mode of the priors. To estimate the dependence on the inits, three different chains with different sets of starting values were analysed by the Gelman–Rubin convergence statistic, as modified by Brooks and Gelman (37).

Results

True seroprevalence and diagnostic test characteristics

True seroprevalence estimates are presented per Rayon and per species (Table V). The overall seroprevalence in cattle was significantly lower than that in the other livestock species. Posterior values of the estimated sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic tests, based on the dataset and analysis of the authors, are presented in Table VI. With only the exception of the specificity of the Huddleson test (human ‘standard’), no substantial difference was observed when comparing the results for the test characteristics estimated by the two models (2dT2P and 1TnP models). The authors observed a statistically significant higher sensitivity for the ELISA (ruminant) in cattle, for FPA in goats (marginally significant) and for both ELISA (ruminant) and FPA in sheep than for the current ‘standard’ test (RBT). The RBT (Ukraine) was found to have the highest specificity of all diagnostic tests in livestock. The specificity of the RBT (Bio-Rad) in humans was significantly higher than that of the ‘standard’ test (Huddleson), but its sensitivity was significantly lower.

Table V. True seroprevalence (TP) estimates of brucellosis in nine Rayons of Kyrgyzstan for humans, cattle, sheep and goats in 2006.

| Species | Population size estimate | Sample size for ‘standard’ test (a) | Positive cases by ‘standard’ test (a) | TP by Bayesian model; median (95% Cr. Int.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At-Bashy | ||||

| Humans | 52,806 | 206 | 41 | 0.13 (0.07–0.21) |

| Cattle | 26,990 | 200 | 5 | 0.02 (0–0.07) |

| Sheep | 123,280 | 200 | 21 | 0.22 (0.12–0.39) |

| Goats | 20,550 | 200 | 40 | 0.31 (0.20–0.51) |

| Naryn | ||||

| Humans | 42,427 | 181 | 35 | 0.13 (0.06–0.21) |

| Cattle | 25,490 | 20 | 2 | 0.08 (0–0.28) |

| Sheep | 92,185 | 181 | 32 | 0.36 (0.22–0.60) |

| Goats | 15,370 | 181 | 32 | 0.27 (0.16–0.46) |

| Kochkor | ||||

| Humans | 55,978 | 177 | 61 | 0.30 (0.21–0.39) |

| Cattle | 27,004 | 220 | 4 | 0.01 (0–0.05) |

| Sheep | 155,080 | ND | ND | ND |

| Goats | 25,850 | ND | ND | ND |

| Jaiyl | ||||

| Humans | 52,395 | 197 | 17 | 0 (0–0.07) |

| Cattle | 22,747 | 142 | 14 | 0.13 (0.06–0.25) |

| Sheep | 50,430 | 180 | 21 | 0.24 (0.14–0.43) |

| Goats | 8,400 | 201 | 22 | 0.16 (0.07–0.30) |

| Sokuluk | ||||

| Humans | 126,718 | 206 | 37 | 0.11 (0.05–0.18) |

| Cattle | 42,936 | 199 | 6 | 0.03 (0–0.09) |

| Sheep | 74,400 | 211 | 4 | 0.03 (0–0.11) |

| Goats | 12,400 | 190 | 5 | 0 (0–0.05) |

| Yssyk-Ata | ||||

| Humans | 104,285 | 203 | 27 | 0.06 (0–0.13) |

| Cattle | 40,109 | 201 | 3 | 0.01 (0–0.05) |

| Sheep | 49,650 | 219 | 0 | 0 (0–0.01) |

| Goats | 8,280 | 85 | 0 | 0 (0–0.05) |

| Karakulga | ||||

| Humans | 87,077 | 200 | 39 | 0.13 (0.06–0.20) |

| Cattle | 24,504 | 199 | 0 | 0 (0–0.02) |

| Sheep | 86,980 | 200 | 0 | 0 (0–0.02) |

| Goats | 14,500 | 200 | 0 | 0 (0–0.02) |

| Uzgen | ||||

| Humans | 166,727 | 202 | 0 | 0 (0–0.01) |

| Cattle | 45,354 | 179 | 0 | 0 (0–0.02) |

| Sheep | 11,080 | 376 | 0 | 0 (0–0.01) |

| Goats | 1,850 | 25 | 1 | 0.04 (0–0.30) |

| Karasuu | ||||

| Humans | 299,325 | 202 | 16 | 0 (0–0.06) |

| Cattle | 72,072 | 200 | 0 | 0 (0–0.02) |

| Sheep | 173,055 | 286 | 0 | 0 (0–0.01) |

| Goats | 28,840 | ND | ND | ND |

| Total/overall seroprevalence | ||||

| Humans | 987,738 | 1,774 | 273 | 0.07 (0.04–0.09) |

| Cattle | 327,206 | 1,560 | 34 | 0.03 (0.01–0.05) |

| Sheep | 971,220 | 1,853 | 78 | 0.12 (0.07–0.23) |

| Goats | 136,040 | 1,082 | 100 | 0.15 (0.07–0.30) |

Huddleson for humans, Rose Bengal test (Ukraine) for cattle, sheep and goats; sample size over all Rayons presented in Table I

Cr. Int.: credibility interval

ND: not determined

TP: true prevalence

Table VI. Estimation of sensitivity and specificity of different diagnostic tests in four species.

| Test | Model used | Sensitivity (95% Cr. Int.)(a) | Specificity (95% Cr. Int.)(a) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | |||

| RBT (Ukraine) | 2dT2P | 0.69 (0.47–0.85) | 0.99 (0.987–0.998) |

| 1TnP | 0.65 (0.41–0.85) | 0.99 (0.986–0.997) | |

| FPA | 0.64 (0.46–0.80) | 0.96 (0.95–0.97) | |

| ELISA (ruminant) | 0.92 (0.79–0.99) | 0.93 (0.91–0.94) | |

| Sheep | |||

| RBT (Ukraine) | 2dT2P | 0.45 (0.30–0.60) | 0.99 (0.98–0.996) |

| 1TnP | 0.46 (0.29–0.64) | 0.996 (0.991–0.998) | |

| FPA | 0.71 (0.57–0.83) | 0.92 (0.90–0.94) | |

| ELISA (ruminant) | 0.63 (0.49–0.76) | 0.94 (0.93–0.96) | |

| Goats | |||

| RBT (Ukraine) | 2dT2P | 0.55 (0.39–0.71) | 0.95 (0.93–0.98) |

| 1TnP | 0.54 (0.37–0.72) | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | |

| FPA | 0.70 (0.54–0.84) | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | |

| ELISA (ruminant) | 0.43 (0.29–0.58) | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) | |

| Humans | |||

| Huddleson | 2dT2P | 0.93 (0.84–0.98) | 0.83 (0.78–0.88) |

| 1TnP | 0.92 (0.82–0.97) | 0.91 (0.89–0.94) | |

| ELISA (human) | 0.90 (0.81–0.95) | 0.77 (0.72–0.81) | |

| RBT (Bio-Rad) | 0.60 (0.48–0.70) | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | |

Cr. Int.: credibility interval

ELISA: enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

FPA: fluorescence polarisation assay

RBT: Rose Bengal test

2dT2P: two dependent tests, two populations

1TnP: one test, n populations

Results of the sensitivity analysis

1TnP model

For cattle and goats, the median of the posterior values and variability (credibility interval) increased slightly when using priors with wider distributions. However, none of the differences was significant (no median lay outside the credibility intervals of the other value). For sheep, the median did not change when wider prior distributions were used, but the variability was slightly enhanced. For humans, however, the medians of the seroprevalences were significantly greater when wider prior distributions were implemented in the model. For the overall true seroprevalence, a median of 0.13 (95% credibility interval 0.10–0.17) was calculated when a wider prior distribution was implemented, differing significantly from the median in Table V with the ‘original’ priors, which was 0.07 (95% credibility interval 0.04–0.09). The posterior values were not dependent on the init values for any Rayon or species.

The 1TnP model was found to be sensitive to the change in the prior modes of the test characteristics: when the prior modes were changed, the median posterior values of the seroprevalence changed in the same direction.

2dT2P model

With regard to the RBT (Ukraine) used in cattle and goats and the Huddleson and ELISA used in humans, the medians of the test characteristics decreased slightly, but not statistically significantly, when using priors with wider distributions. For sheep, however, the model was unstable when the originally planned prior values were used, i.e. there was no convergence of the three chains with the different inits, but the model converged with wider prior distributions. None of the medians of the test characteristics was dependent on the inits (with the exception of sheep, as mentioned). However, for the sensitivity of the RBT (Ukraine) in sheep and cattle and that of the ELISA (ruminant) in sheep, the convergence of chains was late (at around 50,000 iterations).

In the 2dT2P model, the posterior values of interest (test characteristics of test 2) were quite stable when changing the prior modes of both the test characteristics and the seroprevalence of the two distinct populations. Instability was only visible when sheep data were incorporated into the 2dT2P model, when no convergence of the different inits was possible.

Discussion

The authors used Bayesian models to estimate the true seroprevalence of brucellosis for humans, cattle, sheep and goats in three oblasts of Kyrgyzstan in 2006. To their knowledge this is the first estimation of the true seroprevalence of brucellosis in a Central Asian country published in English. Because doubtful test results were handled as positive, the reported seroprevalence may be a slight overestimation of the true seroprevalence. In addition, the intended sample size of 1,800 animals, as calculated elsewhere (16), could not be achieved for goats (Table I) and, therefore, the precision of the seroprevalence estimation for this species may be poorer than 3% (16). The estimated seroprevalence in cattle was lower than that in small ruminants and humans, from which it may be concluded that keeping small ruminants has a higher zoonotic potential than keeping cattle. This is also in line with the higher zoonotic potential of B. melitensis, whose natural hosts are small ruminants, than that of B. abortus, which is mainly carried by cattle (1). However, Kasymbekov et al. isolated only B. melitensis from samples in the same dataset as used in this study, including cattle samples (38). The positive correlation of brucellosis seroprevalence in small ruminants and in humans has been documented and presented elsewhere (16).

The authors chose a 2dT2P model to estimate the test characteristics of the standard test because this model was the most stable one; i.e. based on the sensitivity analysis, the posterior values were less influenced by the chosen prior values than for the other model tested. The assignment to low and high prevalence populations by a third test may have been biased, mainly because the results of the third test may be correlated with the results of tests 1 and 2 (all were serological tests). In addition, the authors assumed equal test characteristics for both the high and low prevalence populations, although test characteristics depend on the prevalence in the population to which they are applied (8). However, these two populations were created artificially and did not reflect spatially different populations with diverse prevalence values.

Given the unreliable results in some species–test combinations, not all the laboratory results were considered suitable for further analysis to estimate the true seroprevalence. For humans, the results of the RBT (Bio-Rad), ELISA (human) and the Huddleson test, and for livestock, the RBT (Ukraine), FPA and ELISA (ruminant) were used for the data analysis. Frequentist-based prevalence estimates did not differ substantially from the Bayesian-derived estimates presented here (data not shown). The choice of the ‘standard’ tests was based only on their common use in Kyrgyzstan. Of all diagnostic tests, they had the greatest influence on the seroprevalence estimates because their data were directly incorporated into the 1TnP model for seroprevalence estimation. However, prior distributions of the ‘standard’ test characteristics had previously been estimated using the 2dT2P model, using the results of the other diagnostic tests.

The estimates of sensitivity and specificity of the diagnostic tests can be used to compare the different tests. The relatively low sensitivity of the RBT in small ruminants estimated in the present study could have been increased if the test had been adapted for use in small ruminants. High sensitivities can be reached with use of the adapted RBT in sheep and goats (28, 39). In the present study, a 1:1 dilution of serum to antigen was applied for small ruminant samples, according to the manufacturer’s recommendation, although the current standard dilution for sheep and goats is 3:1. This may have caused the relatively low sensitivity of the RBT in sheep and goats, and it stresses the importance of performing the tests correctly. The ELISA applied in this study (Chekit®) was based on the use of B. abortus antigen as the solid phase. Although the validation of this test showed good results also for B. melitensis (Bommeli Diagnostics, Switzerland), the resulting test characteristics may be comparatively low. The low sensitivity of the RBT (Bio-Rad) in humans when compared with the other tests, as estimated from the authors’ data, is in contrast with other studies in which high sensitivity of the RBT in humans was described (1). Mert et al. revealed 100% sensitivity in detection of antibodies for both the RBT and the Huddleson test (40). However, the estimation of sensitivity in that paper was based only on culture-positive samples; the application of this technique is unrealistic in field study situations.

The RBT currently remains the recommended screening test for brucellosis in humans (1, 41). Although the ‘standard’ test continues to be used in Kyrgyzstan, another diagnostic test may equal or enhance the precision of diagnosis as a result of better test characteristics. However, besides test characteristics, other issues, including practicability, costs and the specific laboratory settings in Kyrgyzstan, should be taken into account when recommending the ‘best’ diagnostic tests for brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan. Therefore, information regarding improved diagnostics must be used in cost–benefit calculations related to the choice and correct performance of diagnostic tests. In addition, considerations related to the application of the tests, such as their use as confirmatory versus screening tests, are essential, and guidelines for their application exist (4).

Generally, much smaller credibility intervals were found for specificity than for sensitivity in this study, which may have been due to the clear majority of seronegative samples and the resulting larger sample size for estimation of the specificity when compared with the sensitivity. This observation was also made in a recent study of brucellosis data from Cameroon (42).

In the 1TnP model, no significant influence of either the prior distribution width or inits was observed on the posterior values for cattle, sheep and goats. For humans, however, the median of the overall seroprevalence was significantly higher when a wider prior distribution of the test sensitivity and specificity was incorporated into the model. A possible reason for this could be the extremely narrow prior distribution of the diagnostic test’s specificity in the first step model (2dT2P model), which resulted in a small range for the prevalence estimation. However, such a narrow prior distribution of the test specificity was given for all species, as a result of the low variability of the posterior values of the specificity estimated by the 2dT2P model.

The posterior values of the 1TnP model seem to be highly sensitive to the prior modes of the test characteristics used. Consequently, reliable prior information is needed for incorporation into the model. Within this study, such information was obtained by applying the 2dT2P model, in which all diagnostic test results were integrated; this increased the reliability of the prior modes. The observed dependence on the incorporated prior values could have been caused by the often conflicting results from the various diagnostic tests. Such considerable dependence of the posterior values on the modes, and especially the width of the prior information, was also found in the study of brucellosis in Cameroon (42). The prior values of the probability that brucellosis is absent in any Rayon and species were set close to zero. This may be questioned, especially with respect to the absence of positive cases in some Rayons and species when the standard test was used (Table V), and may have led to an overestimation of the true seroprevalence. However, it is very unlikely that the true seroprevalence of brucellosis in any species is zero in a Kyrgyz Rayon, when the relatively low sensitivities of the standard diagnostic tests are also considered.

Conclusion

This study confirms the high seroprevalence of brucellosis in Kyrgyzstan. The test characteristics of the different diagnostic tests show that the standard test for brucellosis currently used in Kyrgyzstan for ruminants is less sensitive than other applied tests, but it is more specific. For humans, the standard test was found to be the most sensitive but not the most specific one. Bayesian models enabled estimation of the true seroprevalence without the use of gold-standard diagnostic tests. The results for the sensitivity analyses revealed that reliable prior information on the test characteristics is essential, especially if the various diagnostic tests may produce contradictory results, which is often the case in the diagnosis of brucellosis. The Bayesian models used in the present study can easily be applied, but the choice and influence of (potentially unreliable) priors should always be explored carefully.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of a project carried out within the Transversal Package Project ‘Pastoral Production Systems’ co-funded by the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research North–South: Research Partnerships for Mitigating Syndromes of Global Change, and the Swiss Development Cooperation, through the Swiss Red Cross in Kyrgyzstan. The authors acknowledge support from the African Research Consortium on Ecosystem and Population Health: Expanding Frontiers in Health (‘Afrique One’), which is funded by the Wellcome Trust (WT087535MA). The authors also acknowledge Penelope Vounatsou and Laura Gosoniou, who provided important input into the critical discussion of the results.

References

- 1.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, World Organisation for Animal Health & World Health Organization (WHO) Brucellosis in humans and animals. WHO; Geneva: 2006. Principle author: M.J. Corbel. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pappas G, Papadimitriou P, Akritidis N, Christou L, Tsianos EV. The new global map of human brucellosis. Lancet infect Dis. 2006;6:91–99. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70382-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare. Brucellosis in sheep and goats (Brucella melitensis) European Commission; Brussels: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) Bovine brucellosis. [accessed on 1 February 2009];Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals. 2008 Available at: www.oie.int/en/international-standard-setting/terrestrial-manual/access-online/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cernyseva MI, Knjazeva EN, Egorova LS. Study of the plate agglutination test with Rose Bengal antigen for the diagnosis of human brucellosis. Bull WHO. 1977;55:669–674. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rogan WJ, Gladen B. Estimating prevalence from the results of a screening test. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;107:71–76. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borel N, Doherr MG, Vretou E, Psarrou E, Thoma R, Pospischil A. Seroprevalences for ovine enzootic abortion in Switzerland. Prev vet Med. 2004;65:205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greiner M, Gardner IA. Application of diagnostic tests in veterinary epidemiologic studies. Prev vet Med. 2000;45:43–59. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen SS, Toft N. A review of prevalences of paratuberculosis in farmed animals in Europe. Prev vet Med. 2009;88:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enoe C, Georgiadis MP, Johnson WO. Estimation of sensitivity and specificity of diagnostic tests and disease prevalence when the true disease state is unknown. Prev vet Med. 2000;45:61–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(00)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Branscum AJ, Gardner IA, Johnson WO. Estimation of diagnostic-test sensitivity and specificity through Bayesian modeling. Prev vet Med. 2005;68:145–163. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branscum AJ, Gardner IA, Johnson WO. Bayesian modeling of animal- and herd-level prevalences. Prev vet Med. 2004;66:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner IA, Stryhn H, Lind P, Collins MT. Conditional dependence between tests affects the diagnosis and surveillance of animal diseases. Prev vet Med. 2000;45:107–122. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(00)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muma JB, Toft N, Oloya J, Lund A, Nielsen K, Samui K, Skjerve E. Evaluation of three serological tests for brucellosis in naturally infected cattle using latent class analysis. Vet Microbiol. 2007;125:187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muller B, Vounatsou P, Ngandolo BN, Guimbaye-Djaibe C, Schiller I, Marg-Haufe B, Oesch B, Schelling E, Zinsstag J. Bayesian receiver operating characteristic estimation of multiple tests for diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis in Chadian cattle. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonfoh B, Kasymbekov J, Durr S, Toktobaev N, Doherr MG, Schueth T, Zinsstag J, Schelling E. Representative seroprevalences of brucellosis in humans and livestock in Kyrgyzstan. EcoHealth. 2012;9(2):132–138. doi: 10.1007/s10393-011-0722-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zinsstag J, Schelling E, Bonfoh B, Fooks AR, Kasymbekov J, Waltner-Toews D, Tanner M. Towards a ‘One Health’ research and application tool box. Vet ital. 2009;45:121–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinmann P, Bonfoh B, Peter O, Schelling E, Traore M, Zinsstag J. Seroprevalence of Q-fever in febrile individuals in Mali. Trop Med int Hlth. 2005;10:612–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonfoh B, Fane A, Traore AP, Tounkara K, Simbe CF, Alfaroukh IO, Schalch L, Farah Z, Nicolet J, Zinsstag J. Use of an indirect enzyme immunoassay for detection of antibody to Brucella abortus in fermented cow milk. Milchwissenschaft. 2002;57:374–376. [Google Scholar]

- 20.University of California, Davis. [accessed on 1 December 2008];Bayesian epidemiologic screening techniques. 2006 Available at: www.epi.ucdavis.edu/diagnostictests/software.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Georgiadis MP, Johnson WO, Gardner IA. Sample size determination for estimation of the accuracy of two conditionally independent tests in the absence of a gold standard. Prev vet Med. 2005;71:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.University of California, Davis. Bayesian epidemiologic screening techniques Obtaining the specific Beta prior distributions for Se, Sp and prevalence with BetaBuster. [accessed on 1 December 2008];Graduate Group in Epidemiology. 2010 Available at: www.epi.ucdavis.edu/diagnostictests/betabuster.html.

- 23.Gall D, Nielsen K. Serological diagnosis of bovine brucellosis: a review of test performance and cost comparison. Rev sci tech Off int Epiz. 2004;23(3):989–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nielsen K, Lin M, Gall D, Jolley M. Fluorescence polarization immunoassay: detection of antibody to Brucella abortus. Methods. 2000;22:71–76. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minas A, Stournara A, Minas M, Papaioannou A, Krikelis V, Tselepidis S. Validation of fluorescence polarization assay (FPA) and comparison with other tests used for diagnosis of B melitensis infection in sheep. Vet Microbiol. 2005;111:211–221. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dajer A, Luna-Martínez E, Zapata D, Villegas S, Gutierrez E, Pena G, Gurria F, Nielsen K, Gall D. Evaluation of a fluorescence-polarization assay for the diagnosis of bovine brucellosis in Mexico. Prev vet Med. 1999;40:67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(99)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marin CM, Moreno E, Moriyón I, Diaz R, Blasco JM. Performance of competitive and indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, gel immunoprecipitation with native hapten polysaccharide, and standard serological tests in diagnosis of sheep brucellosis. Clin diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:269–272. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.2.269-272.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Díaz-Aparicio E, Marín C, Alonso-Urmeneta B, Aragón V, Pérez-Ortiz S, Pardo M, Blasco JM, Díaz R, Moriyón I. Evaluation of serological tests for diagnosis of Brucella melitensis infection of goats. J clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1159–1165. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1159-1165.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gall D, Colling A, Marino O, Moreno E, Nielsen K, Perez B, Samartino L. Enzyme immunoassays for serological diagnosis of bovine brucellosis: a trial in Latin America. Clin diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:654–661. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.5.654-661.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gómez MC, Nieto JA, Rosa C, Geijo P, Escribano MA, Muñoz A, López C. Evaluation of seven tests for diagnosis of human brucellosis in an area where the disease is endemic. Clin vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:1031–1033. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00424-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Memish ZA, Almuneef M, Mah MW, Qassem LA, Osoba AO. Comparison of the Brucella Standard Agglutination Test with the ELISA IgG and IgM in patients with Brucella bacteremia. Diagn Microbiol infect Dis. 2002;44:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(02)00426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konstantinidis A, Minas A, Pournaras S, Kansouzidou A, Papastergiou P, Maniatis A, Stathakis N, Hadjichristodoulou C. Evaluation and comparison of fluorescence polarization assay with three of the currently used serological tests in diagnosis of human brucellosis. Eur J clin Microbiol infect Dis. 2007;26:715–721. doi: 10.1007/s10096-007-0363-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esalatmanesh K, Soleimani Z, Soleimani A. Diagnostic value of Brucella ELISA (IgG and IgM) in patients with brucellosis in Kashan, Iran – 2004. Poster presentation, 13th International Congress on Infectious Diseases; 19–22 June; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yumuk Z, Afacan G, Caliskan S, Irvem A, Arslan U. Relevance of autoantibody detection to the rapid diagnosis of brucellosis. Diagn Microbiol infect Dis. 2007;58:271–273. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laudat P, Audurier A, Choutet P, De Gialluly C, Ducroix JP, Loulergue J. Sérologie de la brucellose: évaluation comparative des réactions d’agglutination, de fixation du complément, d’immuno-fluorescence indirecte et de la contre-immuno-électrophorèse. Méd Mal infect. 1987;17(2):58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanson T, Johnson WO, Gardner IA. Hierarchical models for estimating herd prevalence and test accuracy in the absence of a gold standard. J agric biol environ Stat. 2003;8:223–239. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooks SP, Gelman A. General methods for monitoring convergence of iterative simulations. J comput graph Stat. 1998;7:434–455. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasymbekov J, Imanseitov J, Ballif M, Schürch N, Paniga S, Tonolla M, Benagli C, Petrini O, Akylbekova K, Jumakanova Z, Schelling E, et al. Typing and antibiotic susceptibility of Brucella melitensis isolates from Naryn oblast, Kyrgyzstan. PLoS negl trop Dis. 2013;7(2):e2047. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreira AC, Cardoso R, Travassos Dias I, Mariano I, Belo A, Rolao Preto I, Manteigas A, Pina FA, Correa de Sa MI. Evaluation of a modified Rose Bengal test and an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the diagnosis of Brucella melitensis infection in sheep. Vet Res. 2003;34:297–305. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mert A, Ozaras R, Tabak F, Bilir M, Yilmaz M, Kurt C, Ongoren S, Tanriverdi M, Ozturk R. The sensitivity and specificity of Brucella agglutination tests. Diagn Microbiol infect Dis. 2003;46:241–243. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zinsstag J, Schelling E, Solera J, Blasco JM, Moriyón I. Brucellosis. In: Palmer S, Soulsby L, Torgerson P, Brown D, editors. Oxford textbook of zoonoses: biology, clinical practice and public health control. 2nd Ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bronsvoort BM, Koterwas B, Land F, Handel IG, Tucker J, Morgan KL, Tanya VN, Abdoel TH, Smits HL. Comparison of a flow assay for brucellosis antibodies with the reference cELISA test in West African Bos indicus. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]