Abstract

Background

Sepsis is a leading cause of death, but evidence suggests that early recognition and prompt intervention can save lives. In 2005 Houston Methodist Hospital prioritized sepsis detection and management in its ICU. In late 2007, because of marginal effects on sepsis death rates, the focus shifted to designing a program that would be readily used by nurses and ensure early recognition of patients showing signs suspicious for sepsis, as well as the institution of prompt, evidence-based interventions to diagnose and treat it.

Methods

The intervention had four components: organizational commitment and data-based leadership; development and integration of an early sepsis screening tool into the electronic health record; creation of screening and response protocols; and education and training of nurses. Twice-daily screening of patients on targeted units was conducted by bedside nurses; nurse practitioners initiated definitive treatment as indicated. Evaluation focused on extent of implementation, trends in inpatient mortality, and, for Medicare beneficiaries, a before-after (2008–2011) comparison of outcomes and costs. A federal grant in 2012 enabled expansion of the program.

Results

By year 3 (2011) 33% of inpatients were screened (56,190 screens in 9,718 unique patients), up from 10% in year 1 (2009). Inpatient sepsis-associated death rates decreased from 29.7% in the preimplementation period (2006–2008) to 21.1% after implementation (2009–2014). Death rates and hospital costs for Medicare beneficiaries decreased from preimplementation levels without a compensatory increase in discharges to postacute care.

Conclusion

This program has been associated with lower inpatient death rates and costs. Further testing of the robustness and exportability of the program is under way.

Sepsis is the 11th leading cause of death in the United States,1 ranking 10th for people 65 years of age or older.2 Medicare is the primary payer for 76% of sepsis-related hospitalizations.3 From 2008 through 2011, combined Medicare and Medicaid inpatient reimbursements for a diagnosis-related group (DRG) linked to sepsis totaled $17.7 billion, 5% of which was for stays classified as high-cost outliers.3 Reported in-hospital death rates vary by severity, ranging from 11% in sepsis to more than 40% in septic shock.4–10 Sepsis begins with a systemic immunological response to infection that ultimately becomes dysregulated. Inflammatory mediators that are part of the normal local immune response to infection begin to exert their effects systemically. The incipient organisms can be bacterial, fungal, parasitic, viral, or, in some cases, unknown.11–13 It is important for clinicians to understand that blood cultures are negative in a significant proportion of sepsis cases5,14,15 and that the entire cascade of events in the body's response to infection is not completely understood. Sepsis is defined as “The presence (probable or documented) of infection together with systemic manifestations of infection.”5(p. 583) The systemic Inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is marked by two or more of the following: fever or hypothermia, rapid heart rate, rapid respiratory rate, abnormal white blood cell count.16,17 Clinical signs of early sepsis are often subtle, nonspecific, and overlooked. Sepsis may progress to “severe sepsis,” defined as sepsis with acute single or multiple organ dysfunction, including but not limited to, abnormalities of the coagulation/fibrinolysis system and/or altered mental status, and to “septic shock,” sepsis complicated by persistent hypotension and hypoperfusion despite adequate fluid resuscitation, necessitating the infusion of vasopressors. Some evidence suggests that early recognition and treatment of sepsis according to evidence-based guidelines can avert progression in some patients, thus saving lives and avoiding associated costs.18–24

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign, launched in 2002,25 sparked many hospitals and health care systems, such as Christiana Care,26 to create programs to improve the care and, hopefully, the outcomes of patients with sepsis. These programs were developed largely starting in the mid-2000s; although they shared a common goal, their target populations differed, as did their approaches to achieving the goal. Like the international sepsis performance improvement initiative that was linked to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign,27 the individual programs in the United States for which results have been reported showed improvements in the processes of sepsis care28,29 or both processes and outcomes.24,26,30

In 2005 Houston Methodist Hospital (HMH) established a Sepsis Care Management Performance Improvement (CMPI) committee and prioritized sepsis detection and management in its ICUs, using the approaches of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign.31 That effort was suspended in late 2007 because the effects on sepsis death rates were marginal despite substantial outlays of effort and dollars. The redirection of our hospital's efforts that began in late 2007 focused on designing a program that would be readily used by nurses and ensure early recognition of patients showing signs suspicious for sepsis as well as the institution of prompt, evidence-based interventions to diagnose and treat it.

In this article, we describe the outcomes of HMH's sepsis early recognition and response program. The success of this precedent program led to the grant, in 2012, of a large three-year Health Care Innovation Award from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Center to export this program for further testing to 14 other acute and postacute care facilities.

Methods

Setting

HMH is a tertiary referral and teaching hospital that is the flagship of Houston Methodist, which is composed of the Houston Methodist Research Institute, six community hospitals, emergency centers, and physical therapy clinics serving the greater Houston area.32 HMH itself has 839 operating beds, 73 operating rooms, more than 1,800 affiliated physicians, and more than 6,000 employees. There are more than 35,000 inpatient stays annually at HMH.

Ethics

The project was reviewed and approved by the HMH Institutional Review Board (IRB); because the program described here is a quality improvement activity, the IRB found that there is no requirement under current regulations for it to be conducted with patients' informed consent.

The Intervention and Its Four Components

The HMH sepsis program was built on the premise that early identification of patients developing sepsis and rapid intervention will halt or slow progression along the clinical trajectory, thus improving outcomes and reducing costs. The program does not reduce the risk for or incidence of sepsis. The program engages bedside nurses—the health professionals who spend the most time with patients—as “first responders” and nurse practitioners (NPs) as “second responders.”

The HMH sepsis intervention has four components: (1) organizational commitment and data-based leadership; (2) development and integration of an early sepsis screening tool into the electronic health record (EHR); (3) creation and implementation of screening and response protocols; and (4) education and training of clinicians (RNs, NPs), who serve as the program's first and second responders.

1. Leadership

The program was designed and refined and continues to be led by a multidisciplinary CMPI committee [including S.L.J., C.B.-G., E.G., M.D.], which is chaired by physicians [including F.M.] and monitors screening statistics, evaluates the program's effects on patient outcomes and costs, and advocates for hospital policies and educational efforts intended to improve the care for HMH patients at risk for sepsis.

2. Development of the Early Sepsis/SIRS Screening Tool

A tool that could be used by bedside nurses to screen patients for early signs of sepsis and a screening process seamlessly integrated into routine bedside nursing care and documentation were thought by HMH leaders to be the core of the program. In fact, a major reason the 2005 initiative was unsuccessful was that HMH nurses found the Surviving Sepsis Campaign-Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI; Cambridge, Massachusetts) screening tool too cumbersome and time-consuming, which posed barriers to adoption and use. Accordingly, after reviewing other screening tools,33–35 a team led by HMH acute care surgeons developed an early sepsis/SIRS screening tool for use by bedside nurses.18 Like a part of the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II system,33 the early sepsis screening tool employs subscores for routinely collected clinical data—heart rate, respiratory rate, minimum and maximum temperatures, and white blood cell count—that are derived from a 5-point ordinal scale (0–4) on the basis of increasing deviation from normal values, and combined with a “yes (1)/no (0)” subscore for acute deterioration in mental status as assessed by the bedside nurse (Appendix 1, available in online article). The total score can range from 0 to 17. A score of ≥ 4 was set as the threshold for a positive early sepsis/SIRS screen; this score triggers an evaluation by a “second responder,” as we describe in the next section. When evaluated during a five-month period beginning on September 1, 2007, in HMH's 31-bed surgical ICU, the probability that sepsis was present in a patient who screened positive (positive predictive value) was 80.2%, while the probability that sepsis was absent when a screen was negative (negative predictive value) was 99.5%.18 A recent study found that severe sepsis or septic shock was present in 87.9% of ICU patients who met > 2 SIRS criteria.36

We took the screening tool through three major format iterations between January 2008 and September 2011, culminating in its integration into HMH's EHR. The first version, a pen-and-paper tool, was effective but unlikely to be able to support growth in the program, and nurses had difficulty translating a value of a parameter (for example, heart rate) to an integer on the scale. These problems were solved by a Web-based version that automated the scoring algorithm. The development of the Web-based tool followed a rigorous process of task, user, representation (user interface), and function analysis37,38 (Appendix 2, available in online article). Automation eliminated interpretive and mathematical errors, and, after the user interface was refined by inserting representative icons next to data entry fields, transposition errors (for example, heart rate entered into field for respiratory rate) were eliminated. Transcription errors (for example, misplaced decimal point on the white blood cell count) still occurred. The third iteration, which involved integrating the screening tool into HMH's EHR system, was accomplished in September 2011. This integrated tool eliminates all data-entry errors by autopopulating the fields with a patient's most recent vital signs (heart and respiratory rates within the previous 2 hours; minimum and maximum temperatures within the previous 24 hours) and white blood cell count (within the previous 24 hours), with data retrieved directly from the EHR. Bedside nurses report that, when using this integrated tool, it takes them a minute or less to screen a patient for signs and symptoms of sepsis. After a bedside nurse initiates a screen, validates vital signs, and enters and saves the assessment of the patient's mental status, a score is derived automatically. If it is positive (≥ 4), the program pages the second responder, and a message appears instructing the nurse to contact a second responder, which provides an opportunity for a nurse-to–nurse practitioner discussion of the patient.

3. Screening and Response Protocols

Initially, screening was focused on patients in the ICUs, but it was soon realized that the real opportunity to detect sepsis early and avert progression to more severe stages existed on the regular inpatient units. Accordingly, after conducting analyses of internal unit-level data, the CMPI Committee used sepsis rates and risk to prioritize the inpatient units (for example, the surgical units) and types of patients (for example, patients transferred to HMH from other health care facilities or admitted to an acute care ward from the emergency department) for inclusion in the screening program. Screening is not conducted on 100% of HMH units but rather is focused on higher-risk units. Bedside nurses screen patients for sepsis on hospital admission, at 12-hour intervals, and on changes in clinical condition. The 12-hour screening interval was set after analyses had shown that patients transferred from the wards to the HMH surgical ICUs with advancing signs and symptoms of sepsis had, in fact, manifested the initial signs for an average of 25 hours before those signs were noted and interpreted correctly. (Nursing directors are allowed to decide the specific clock-time that the 12-hour screening will occur on their unit, which enhances compliance with the program.) Patients with positive screens are evaluated by a second responder, who at HMH is a NP. Second evaluation and the initiation of definitive therapy (Appendix 3, available in online article) are slated to take place within one hour of the positive screen. The evaluation and treatment protocols used by second responders with screen-positive patients are based on the 2008 and 2012 recommendations for goal-directed therapies from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock and others22,39 and consensus recommendations of a trans-disciplinary panel of HMH clinicians.

Besides knowing how to assess the patient's likelihood of sepsis, search for a potential infection source, and initiate guideline-based care, second responders must be able to start therapy quickly, which means they must be free of other clinical assignments that limit their ability to respond rapidly when called and have the clinical privileges and scope-of-practice credentials to institute already-approved medical protocols or have ready access to someone who does. In the state of Texas, nurse practitioners are licensed to diagnose and treat acute and chronic diseases, including sepsis, and hospital-based NPs can be credentialed for diagnosis and treatment by the hospital staffs on which they serve. At HMH, second responders always notify the attending physicians of the patients they evaluate, but the start of the sepsis protocol by the nurse practitioner is not dependent on the physician's approval.

4. Education and Training of Nurses

As part of HMH's sepsis program, HMH clinicians developed a series of courses covering the epidemiology, signs and symptoms, and impact of sepsis. These have been combined with HMH's in-service learning modules for bedside nurses, who must demonstrate mastery of content before using the screening tool with patients as well as on annual reexamination. HMH's second responders must undergo intensive education and training that involves simulation scenarios to ensure competency in sepsis diagnosis and treatment. Second responder training includes completion of an online course (SimSuite “Sepsis Comprehensive”; Medical Simulation Corporation, Denver), as well as a four-hour simulation workshop using SimSuite Sepsis Scenarios software and a SimMan 3G Simulator (Laerdal, Wappingers Falls, New York).

Evaluation Plan and Statistical Analyses

During the three implementation years of 2009 through 2011, the program was supported entirely by HMH resources. In 2012 HMH was awarded a federal grant to expand the program internally and to other sites; although we present HMH mortality data through 2014, the results of the federally funded program are not yet available.

Patients Screened, Screens per Unique Patient, and Proportion of Patients with Positive Screens

Evaluation focused on the “reach” of the screening program in terms of numbers of patients screened per time period after the start of the program (January 2009), the number of screens per unique patient, and the proportion of patients screened who had positive screens.

Inpatient Death Rates of Sepsis-Associated Stays

Inpatient death rates of sepsis-associated stays per time period were also tracked. These data were obtained from inputs from the sepsis screening program itself, as well as data from hospital discharge abstracts, provided by the HMH performance improvement department. A sepsis-associated stay was defined as a hospital inpatient encounter with one or more of the following International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes in any diagnosis slot of hospital discharge abstract (Uniform Billing Form 04): 038 (septicemia), 995.91 (sepsis), 995.92 (severe sepsis), or 785.52 (septic shock).

To determine the likelihood that changes in inpatient death rates of sepsis-associated stays observed after program implementation were chance fluctuations rather than real differences, we conducted several analyses of monthly mortality data on all HMH sepsis-associated stays of persons older than 18 years of age from January 2006 through December 2014 (108 months), with the preimplementation period being January 2006 through December 2008 and the implementation period January 2009 and thereafter.

First, we conducted a two-sample test of proportions comparing the inpatient death rate in the preimplementation period with that in the implementation period—an analysis that does not incorporate the time series autocorrelation present in the data. Next, to show a smoothed estimate of the month-over-month inpatient death rate, we created a Lowess plot40 with a bandwidth of 0.1 and plotted the averages of the death rate in the preimplementation period and the implementation period. Confidence intervals of the monthly sepsis-associated death rates were calculated assuming binomial distribution and using the exact method. These analyses were conducted using Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas). Finally, we analyzed the monthly death rates using Change-Point Analyzer 2.3 (Taylor Enterprises, Inc., Libertyville, Illinois), which uses cumulative sums of the deviations to detect changes and uses bootstrap analysis to determine confidence intervals.

Cost and Utilization Data for Medicare Beneficiaries

We also conducted a before-after analysis of cost and utilization data for Medicare beneficiaries treated for sepsis at HMH. We designated January through June 2008 as the baseline period (sepsis program being designed but not yet implemented) and January through June 2011 as the comparison period. These data were obtained from the HMH hospital claims databases, and the analyses were conducted by the HMH business office using the same ICD-9-CM codes as identified earlier. We included discharge disposition in these analyses because we posited that, if any decreases in inpatient death rates were observed, they might be attributable to the discharge of moribund patients to postacute care rather than to the saving of lives by the sepsis screening and early recognition program.

Results

Patient Screens, Screens per Unique Patient, and Proportion of Patients with Positive Screens

In 2009, the first year of program implementation, 22,771 sepsis screens were performed on 3,413 unique patients, an average of 6.7 screens per patient (Table 1, page 487). By 2011, this had increased to 56,190 screens in 9,718 patients (an average of 5.8 screens per patient). In 2011 about 33% of HMH inpatient stays were included in the screening program, up from about 10% in 2009. As Table 1 shows, the proportion of unique patients screened who had positive screens was relatively stable at 11%, 12%, and 11% in 2009, 2010, and 2011, respectively.

Table 1. Screening Program Volume and Sepsis Detection Rates, 2009–2011, Houston Methodist Hospital*.

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of unique patients screened | 3,413 | 7,965 | 9,718 |

| % < 65 years of age | 58 | 58 | 57 |

| % 65–74 years of age | 16 | 19 | 20 |

| % ≥ 75 years of age | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| % age unknown | 4 | 1 | < 1 |

| No. of screens | 22,771 | 48,486 | 56,190 |

| Average no. of screens/patient | 6.7 | 6.1 | 5.8 |

| No. (%) of unique patients screened who had positive screens | 372 (11) | 933 (12) | 1,044 (11) |

2008 was the preimplementation year, during which the program was being designed.

Inpatient Death Rates of Sepsis-Associated Stays

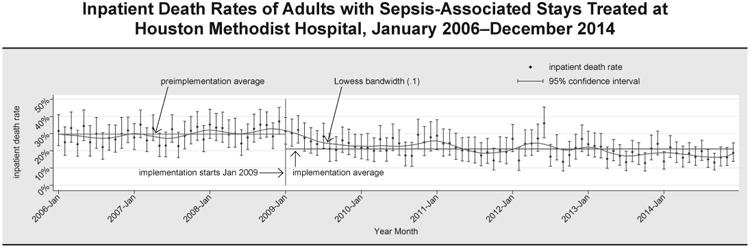

Between 2006 and 2014, there were 15,353 sepsis-associated inpatient stays at HMH. After implementation of the program (2009 forward), the sepsis-associated inpatient death rate was 21.1% (2,213/10,479)—significantly lower than the rate in the preimplementation period (2006–2008) of 29.7% (1,450/4,874); p < .0001. Figure 1 (page 488) shows the trend over time in monthly inpatient death rates of sepsis-associated stays at HMH. Death rates trended down over the period, though the downward trend month-over-month was not monotonic. If the average death rate of 29.7% observed in the preimplementation period 2006–2008 had been sustained through 2009–2014, there would have been 3,117 deaths instead of the 2,213 observed; thus the rough estimate of deaths averted is 904. The decrease in death rates has been sustained through December 2014; the plot in Figure 1 indicates that the mortality rate continues to fall. (In fall 2011 HMH prepared the grant application for the CMS Innovation Award for the Sepsis Early Recognition and Response Initiative; the announcement and funding of the award in the first half of 2012 and the subsequent infusion of additional infrastructure resources enabled screening to be extended to additional HMH units and undoubtedly influenced the effects associated with the program in ways that cannot be measured.) Change-point analysis identified one level-1 change point (p < .001)—a decrease in the inpatient death rate in Month 5 of 2009, about five months after implementation began.

Figure 1. A Lowess plot was graphed to show a smoothed estimate of the month-over-month death rate; 2006–2008 was the preimplementation period; program implementation began in 2009.

Inpatient Death Rates of Sepsis-Associated Stays and Cost and Utilization Data for Medicare Beneficiaries

To further evaluate the possibility that the observed changes in inpatient death rates of sepsis-associated stays were coincidental rather than attributable to the sepsis early recognition and response program, we conducted a detailed analysis of Medicare beneficiaries treated for sepsis at HMH (Table 2, above), designating the first two quarters of 2008 (the preimplementation year) as the baseline period and the first two quarters of 2011 (full implementation) as the comparison period. The inpatient death rate for sepsis-associated stays was 31% at baseline and 23% in the comparison period. Among survivors, 46% were discharged home with or without home health in the baseline period, compared with a small decrease to 42% in the comparison period. Among patients surviving to hospital discharge, there was a 4-percentage-point increase in the number of patients discharged to postacute care (in contrast to home with or without home health) in the post-implementation period (Table 2). The proportion of survivors discharged to postacute care (long-term acute care hospital, skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation, or other hospital) was 44% at baseline and 48% in the comparison period.

Table 2. Sepsis-Associated Hospital Volume, Costs, and Outcomes, Houston Methodist Hospital, Medicare Beneficiaries Only*.

| 2008 Q1 & Q2 | 2011 Q1 & Q2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total No. of Sepsis-Associated Medicare Discharges | 4 11 | 442 |

| N(%) < 65 years of age | 115(28) | 134(30) |

| 65–74 years of age | 102(25) | 123(28) |

| 75+ years of age | 194(47) | 185(42) |

| Average length of stay (interquartile range) | 15.1(6–20) | 12.8(5–16) |

| No. (%) CMS high-cost outlier stays | 161(39) | 104(24) |

| Total CMS outlier payments for these sepsis stays | $5,566,691 | $3,212,070 |

| Average outlier payment | $34,576 | $30,885 |

| Average MS-DRG weight, sepsis stays | 4.1218 | 3.6933 |

| No. (%) inpatient deaths | 128(31) | 103(23) |

| Discharge destination of survivors, N (%)† | ||

| Home, routine | 100(35) | 97(29) |

| Home health | 29(10) | 44(13) |

| Hospice | 19(7) | 31(9) |

| Long-term acute care hospital | 73(26) | 83(24) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 38(13) | 68(20)‡ |

| Rehabilitation hospital or unit | 9(3) | 8(2) |

| Other hospital | 5(2) | 3(1) |

| Nursing home | 7(2) | 5(1) |

Q1, first quarter (January–March); Q2, second quarter (April–June); CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; MS-DRG, Medicare severity-diagnosis-related group.

Sepsis International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code (0.38.0–038.9; 995.91; 995.92; or 758.52) in any diagnosis field of Uniform Billing Form 04, first six months of 2008 (preimplementation; baseline period) and first six months of 2011 (postimplementation; comparison period). Data are drawn from hospital claims databases.

Discharge destination was unknown for three survivors in 2008.

p < .05; 2011 versus 2008.

During the baseline period, there were 411 sepsis-associated stays of Medicare beneficiaries at HMH (49 sepsis-associated stays per 1,000 Medicare stays at HMH), 39% of which reached CMS outlier status. (To protect hospitals from large financial losses, CMS supplements its predetermined base payment rate for a DRG with outlier payments when services for a given hospital stay reach extraordinarily high costs.41) Outlier payments for these stays totaled nearly $5.6 million. During the comparison period, there were 442 sepsis-associated Medicare stays at HMH (48 per 1,000 Medicare stays at HMH, roughly the same as in the first half of 2008), but only 24% reached CMS outlier status, and outlier payments for this six-month period decreased to roughly $3.2 million—a reduction of nearly $2.4 million compared with the baseline period. In addition, a reduction in the average MS (Medicare severity)-DRG weight (case complexity or severity) was observed for these sepsis-associated stays between the baseline and comparison periods, from 4.1218 to 3.6933. Taking together the reductions in outlier payments and base case payments (CMS base case payments for inpatient care are linked to MS-DRG weight), CMS reimbursed HMH more than $6.5 million less in inpatient prospective system payments in 2011 than it would have if sepsis care patterns had been the same as they were in 2008.

Discussion

The analyses of the pre- and postimplementation periods at HMH indicate that its sepsis early recognition and response program was associated with substantial and sustained decreases in inpatient death rates in patients treated for sepsis at HMH. To assess the overall trend in mortality and discharge dispositions of the sepsis-associated inpatient population, we derived these results from an analysis of the entire population of sepsis associated stays in the pre- and postexpansion periods, regardless of whether or not the patient was screened or responded to during the encounter. Other multifaceted sepsis performance improvement initiatives have also reported such decreases, though they focused on severe sepsis and septic shock (HMH includes septicemia/sepsis) and targeted only patients in ICUs (HMH targets patients on general inpatient units).24,26,29 The cornerstone of the HMH program is nurses: hospital nurses who serve as the initial detectors of signs of sepsis, as well as the initiators of evidence-based diagnosis and treatment protocols. The analyses of Medicare beneficiaries treated at HMH for sepsis provide evidence that improved patient outcomes (lower death rates) were associated with lower costs of inpatient care. Lower inpatient death rates and lower inpatient costs were not offset by comparable increases in the proportions of survivors discharged to higher levels of postacute care. The presumed mechanism by which early detection of sepsis reduces in-hospital mortality and reduces the costs of inpatient care is that it stops the progression of sepsis along the trajectory to severe sepsis and septic shock and avoids their attendant morbidity and treatment costs.

The four key elements of the HMH sepsis early recognition and response program can be summed up as leadership coupled with organizational commitment, health information technology support for bedside nurses, evidence-based screening and response protocols, and nursing workforce education and training. Regarding the first element, the institution's disappointments with its severe sepsis and septic shock screening efforts in the mid-2000s led to redoubled commitment and refocused effort. The institution devoted substantial effort to the development and deployment of a sepsis program that would work and made it apparent to its nursing and medical staffs—and the information technology staff who integrated the screening tool into the EHR—that improving care and outcomes for patients with sepsis was an organizational priority. Audit and feedback of data, one of the most powerful influences on provider behavior,42 allowed continual refinement of the program. In addition, positive results, made available throughout the organization, created and sustained energy and commitment to the program. As Rogers pointed out in his landmark book Diffusion of Innovations, “the easier it is for individuals to see the results of an innovation, the more likely they are to adopt it.”43(p. 16) From the beginning, the HMH Sepsis CMPI Committee used data on screening volume and results to refine the early detection and response program. However, the integration of the screening tool into HMH's EHR system made it much easier for the CMPI Committee to evaluate and communicate the reach of the program, compliance with screening and response protocols, and the epidemiology and outcomes of HMH patients with sepsis.

All sepsis quality improvement programs include the four key elements of leadership, technology, evidence-based clinical protocols, and workforce education to varying degrees and in various configurations. We believe that the factors that differentiate our program are its focus on all inpatients, not just patients in the ICU; the goal of identifying sepsis early, before it progresses to severe sepsis and septic shock; the fact that nurses are the frontline implementers of screening and response protocols; the intensive simulation training that our second-responder nurses undergo; and the seamless integration of the screening tool into the hospital's electronic data and information systems supporting bedside patient care.

Our statistical and change-point analyses show that inpatient death rates for sepsis-associated stays at HMH undoubtedly changed beginning in 2009, coinciding with the implementation of the new program. Because this is a before-after study, we cannot establish causation or rule out the possibility that the decreases in inpatient death rates for sepsis-associated stays at HMH simply reflected temporal trends affecting the United States as a whole.44 In fact, Stevenson et al. have shown that 28-day mortality rates of patients with severe sepsis randomized to the control or “usual care” arms of multicenter trials of sepsis therapy decreased from 46.9% for the 1991–1995 period to 29% for the 2006–2009 period,45 when decreases in observational data of inpatient death rates of sepsis-associated stays were also found. However, there are several reasons why the 2008–2011 decreases in HMH's sepsis-associated inpatient death rates and revenues for sepsis-associated stays might reasonably be attributed to its sepsis early recognition and response program. First, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the proportion of infections, including sepsis, related to antibiotic-resistant “super-bugs” continues to increase over time,46,47 which would have increased, not decreased, treatment intensity and length of stay during the period we studied. Second, the MS-DRG system came online in 2007 with its three-tiered DRG classification of no complications or comorbidities (CC); with CC; and with major CC (MCC). Because sepsis puts stays into an MCC DRG class, the MS-DRG weight for sepsis should have increased thereafter at HMH, but it decreased. Furthermore, at HMH the overall case mix index for all discharges increased from 1.9757 in 2008 to 2.0943 in 2011. Thus, the reduction in the DRG weight for sepsis-associated stays was not due to an overall trend of decreasing severity of patients treated at our hospital. Finally, CMS did not make any significant changes to the outlier payment structure between 2008 and 2011, so that is not an explanation for the decrease in outlier stays and payments to HMH.

After the announcement of a national peer-reviewed competition for projects that could save lives, improve care, and reduce costs (authorized by the 2010 Affordable Care Act48), HMH created the Texas Gulf Coast Sepsis Network to bring together hospitals, long-term acute care hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities interested in testing the HMH model at their own sites. The CMS Innovation Center awarded HMH and the 14-site Network a three-year Health Care Innovation Award—the Sepsis Early Recognition and Response Initiative, SERRI—to test the extent to which the HMH sepsis early recognition and response program can be implemented and its outcomes replicated in these disparate facilities.49 The CMS–funded project is entering its final year, and results are not yet available.

Limitations

Because this was an observational study using a pre-post design without a concurrent control, we cannot be sure that the implementation of the sepsis early recognition and response program caused the decrease in inpatient death rates of sepsis-associated stays and reductions in the costs of hospital care for Medicare beneficiaries treated for sepsis at HMH. Also, our analyses of outcomes and costs were not restricted just to patients who were hospitalized on units where the sepsis screening program was active but rather included all patients during the period who had sepsis-associated stays at HMH. Finally, even if the improvements in outcomes and reductions in costs are due to the sepsis early recognition and response program, it is not possible to know the extent to which the program is generalizable to other acute care hospitals.

Conclusions

The HMH program reported in this article is one of many being implemented across the United States to detect sepsis early and treat it promptly.50 Further testing of the robustness and exportability of these programs is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 1. Scoring Algorithm, Early Sepsis/SIRS Screening Tool

Appendix 2. Screen Shot of the Web-Based Early Sepsis/SIRS Screening Tool

Appendix 3. Decisional Protocol Followed by Second Responders, SERRI Program

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by Grant Number 1C1CMS330975-01-00 from the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US Department of Health and Human Services or any of its agencies. The research presented here was conducted by Houston Methodist. Findings might or might not be consistent with or confirmed by the independent evaluation contractor.

The authors thank Jennifer Steele, who served as lead second responder for the sepsis program at Houston Methodist Hospital (HMH); Lindrel Thompson, who served a key role in the analyses of outcomes and costs of Medicare beneficiaries treated at HMH for sepsis; Shirley K. Tran, Theresa T. Pinn, Juan C. Nicolas, and Alexis L. Rose, who helped to transform the HMH sepsis program into an ongoing multicenter innovation sepsis study; Belimat Askary, who provided hospital claims data for the analyses; Mary A. Hall, who helped draft earlier versions of this manuscript; Laura J. Moore, Fred A. Moore, Joe F. Sucher, Krista L. Turner, and S. Rob Todd, who conceived and crafted the first paper version of the sepsis screening tool; and Jiajie Zhang, Todd R. Johnson, and Dean F. Sittig, who were instrumental in development of the user interface for the tool and its usability and who also served as mentors to Dr. Jones as he pursued his Master of Science in Health Informatics (2008–2010). Dr. Jones, at that time, was supported in part by a training fellowship from the Keck Center for Interdisciplinary Bioscience Training of the Gulf Coast Consortia (NLM Grant No. 5T15LM007093). Also, the authors thank the information technology team that integrated the screening tool into the electronic health record system of the Methodist Hospital System: Penny Black, Xiaoyang (Maggie) He, Christopher Magnussen, Jennifer Peterson, and Michael Shimp. Finally, the authors thank the clinical leaders whose support has been essential for the development and maturation of the sepsis program at HMH: Marc Boom, Roberta Schwartz, Barbara Bass, Stuart Dobbs, Ron Galfione, Ashley Drews, Janice Zimmerman, and Victor Feinstein.

Footnotes

Online Only Content: http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/jcaho/jcjqs, See the online version of this article for

Contributor Information

Stephen L. Jones, Sepsis Early Recognition and Response Initiative, and Chief Clinical Informatics Officer, Department of Surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital; Division Chief of Health Informatics, Center for Outcomes Research, and Research Scientist and Assistant Member, Houston Methodist Research Institute; and Assistant Professor of Medical Informatics in Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City.

Carol M. Ashton, Department of Surgery, Methodist Institute for Technology, Innovation, and Education, Houston; Co-Director, Center for Outcomes Research, Houston Methodist Research Institute; and Research Professor of Medicine in Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Lisa Kiehne, Sepsis Early Recognition and Response Initiative, Department of Surgery, Houston Methodist Hospital Research Institute.

Elizabeth Gigliotti, Nurse Practitioner Program, Houston Methodist Hospital, is Director, Nurse Practitioner Program, Houston Methodist West Hospital.

Charyl Bell-Gordon, Nurse Practitioner Program, Houston Methodist Hospital, is Director of Emergency Services, Houston Methodist San Jacinto Hospital.

Maureen Disbot, Quality Operations and Patient Safety, Houston Methodist Hospital, and Vice President, Clinical Analytics, Houston Methodist Hospital System, is Vice President, Quality and Patient Safety, St. Joseph Health System, Irvine, California.

Faisal Masud, Weill Cornell Medical College, and Medical Director of Critical Care and Associate Quality Officer, Houston Methodist Hospital.

Beverly A. Shirkey, Center for Outcomes Research, Department of Surgery, Houston Methodist Research Institute.

Nelda P. Wray, Center for Outcomes Research, Houston Methodist Research Institute; Research Scientist, Department of Surgery, Methodist Institute for Technology, Innovation, and Education; and Research Professor of Medicine in Surgery, Weill Cornell Medical College.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Vital Statistics System: Leading Causes of Death. [Accessed Oct 1, 2015]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/LCWK9_2013.pdf. [PubMed]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Vital Statistics System, National Center for Health Statistics. Ten Leading Causes of Death and Injury by Age Group, United States—2013. [Accessed Oct 1, 2015]; http://www.cdc.gov/injury/images/lc-charts/leading_causes_of_death_by_age_group_2013-a.gif. [PubMed]

- 3.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP Statistical Brief 160. Torio CM, Andrews RM. [Accessed Sep 24, 2015];National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011. 2013 Aug; http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb160.pdf. [PubMed]

- 4.Rangel-Frausto MS, et al. The natural history of the systemic Inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). A prospective study. JAMA. 1995 Jan 11;273(2):117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger RP, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin GS, et al. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003 Apr 17;348(16):1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angus DC, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: Analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaieski DF, et al. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(5):1167–1174. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ProCESS Investigators. A randomized trial of protocol-based care for early septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 1;370(18):1683–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asfar P, et al. High versus low blood-pressure target in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr 24;370(17):1583–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gulamhussein MA, et al. Hepatopulmonary fistula: A life threatening complication of hydatid disease. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015 Jul 29;10:103. doi: 10.1186/s13019-015-0311-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepak A, Andes D. Fungal sepsis: Optimizing antifungal therapy in the critical care setting. Crit Care Clin. 2011;27(1):123–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinberg BE, Goldenberg NM, Lee WL. Do viral infections mimic bacterial sepsis? The role of microvascular permeability: A review of mechanisms and methods. Antiviral Res. 2012;93(1):2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pien BC, et al. The clinical and prognostic importance of positive blood cultures in adults. Am J Med. 2010;123(9):819–828. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinstein MP, et al. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures: A comprehensive analysis of 500 episodes of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. II. Clinical observations, with special reference to factors influencing prognosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5(1):54–70. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bone RC, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bone RC, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. 1992. Chest. 2009;136(5 Suppl):e28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore LJ, et al. Validation of a screening tool for the early identification of sepsis. J Trauma. 2009;66(6):1539–1546. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181a3ac4b. discussion 1546–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Micek ST, et al. Before-after study of a standardized hospital order set for the management of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(11):2707–2713. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000241151.25426.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumar A, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1589–1596. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar A, et al. Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest. 2009;136(5):1237–1248. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivers E, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 8;345(19):1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kortgen A, Niederprüm P, Bauer M. Implementation of an evidence-based “standard operating procedure” and outcome in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(4):943–949. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206112.32673.D4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen HB, et al. Implementation of a bundle of quality indicators for the early management of severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with decreased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(4):1105–1112. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000259463.33848.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall JC, Dellinger RP, Levy M. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: A history and a perspective. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2010;11(3):275–281. doi: 10.1089/sur.2010.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zubrow MT, et al. Improving care of the sepsis patient. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(4):187–191. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(08)34022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy MM, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: Results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(2):222–231. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1738-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whippy A, et al. Kaiser Permanente's performance improvement system, part 3: Multisite improvements in care for patients with sepsis. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2011;37(11):483–493. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(11)37061-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seoane L, et al. Using quality improvement principles to improve the care of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Ochsner J. 2013;13(3):359–366. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller RR, 3rd, et al. Multicenter implementation of a severe sepsis and septic shock treatment bundle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Jul 1;188(1):77–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201212-2199OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dellinger RP, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(3):858–873. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000117317.18092.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Texas Medical Center. Houston Methodist Hospital. [Accessed Sep 26, 2015]; http://www.texasmedicalcenter.org/member/houston-methodist-hospital/

- 33.Knaus WA, et al. APACHE II: A severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldhill DR, et al. A physiologically-based early warning score for ward patients: The association between score and outcome. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(6):547–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2005.04186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simpson SQ, et al. Daily routine screening for SIRS is inefficient for detecting severe sepsis. Chest. 2006;130(4 MeetingAbstracts):222S–b. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaukonen KM, et al. Systemic Inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. New Engl J Med. 2015 Apr 23;372(17):1629–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Butler KA. UFuRT: A work-centered framework and process for design and evalution of information systems. Proceedings of HCI International. 2007:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, Walji MF. TURF: Toward a unified framework of EHR usability. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(6):1056–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dellinger RP, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(1):296–327. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000298158.12101.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J Am Stat Assoc. 1979;74(368):829–836. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levinson DR. Washington, DC: US Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Inspector General; 2013. [Accessed Sep 26, 2015]. Medicare Hospital Outlier Payments Warrant Increased Scrutiny. http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-10-00520.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ivers N, et al. Audit and feedback: Effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Jun 13;6:CD000259. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th. New York City: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iwashyna TJ, Angus DC. Declining case fatality rates for severe sepsis: Good data bring good news with ambiguous implications. JAMA. 2014 Apr 2;311(13):1295–1297. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stevenson EK, et al. Two decades of mortality trends among patients with severe sepsis: A comparative meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):625–631. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Antibiotic/Antimicrobial Resistance. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. [Accessed Oct 1, 2015];2013 http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System. The 2013 NARMS Annual Human Isolates Report. [Accessed Oct 1, 2015]; http://www.cdc.gov/narms/reports/annual-human-isolates-report-2013.html.

- 48.GovTrack. H.R. 3590 (111th) Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Public Law 111–148. [Accessed Sep 26, 2015];2010 Mar 23; http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr3590.

- 49.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Health Care Innovation Awards: Project Profile. The Methodist Hospital Research Institute; [Accessed Sep 16, 2015]. Project Title: “Sepsis Early Recognition and Response Initiative (SERRI)”. http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/participant/Health-Care-Innovation-Awards/SERRI.html. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rhee C, Gohil S, Klompas M. Regulatory mandates for sepsis care—Reasons for caution. N Engl J Med. 2014 May 1;370(18):1673–1676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1400276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Scoring Algorithm, Early Sepsis/SIRS Screening Tool

Appendix 2. Screen Shot of the Web-Based Early Sepsis/SIRS Screening Tool

Appendix 3. Decisional Protocol Followed by Second Responders, SERRI Program