Abstract

Although all patients with asthma have variable airflow obstruction, airway inflammation, and bronchial hyperresponsiveness, some have disease that is severe in many aspects: persistent airflow obstruction, ongoing symptoms, increased frequency of exacerbations and most importantly, a diminished response to medications. A number of definitions have emerged to characterize the clinical features of severe asthma, but a central feature of this phenotype is the need for high doses of medications, especially corticosteroids, in attempts to achieve disease control. The prevalence of severe asthma is also undergoing reevaluation from the usual estimate of 10% to larger numbers based on medication needs and the lack of disease control achieved. At present, the underlying mechanisms of severe asthma are not established but likely reflect a heterogeneous pattern, rather than a single unifying process. Guideline-directed treatment for severe asthma has limits with usual approaches centered on high doses of inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting beta-agonists, and trials with omalizumab, the monoclonal antibody to IgE. With the development of approaches to recognize asthma phenotypes with distinct pathogenesis and hence unique therapeutic targets, it is hoped that a personalized strategy in treatment directed toward disease-specific features will improve outcomes for this high risk, severely affected population of patients.

Keywords: Asthma, corticosteroids, bronchodilators, immunomodulators, anti-IgE

Introduction

Asthma affects over 18 million adults and 7 million children in the United States making it one of the most common chronic diseases.1 Moreover, the prevalence of asthma has continued to increase significantly, even over the last 10 years, with major expansions found in inner city populations. Fortunately, most patients with asthma can achieve good control of their disease by using anti-inflammatory medications or various combinations of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and bronchodilators. However, a significant proportion of asthma patients remains symptomatic despite treatment with high dose ICS, inhaled long acting bronchodilators (LABA), and, even in some cases, systemic corticosteroids. This group has been defined as “severe asthma”, “refractory asthma”, or “treatment-resistant asthma”. Estimates vary as to what proportion of the asthma population falls into this most severely affected group. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s (NHLBI) Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) suggests that roughly 15% of asthmatic patients are in this group.2 Information from other studies, however, including the Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL (GOAL) study, suggests that this percentage may be an underestimate.3 Regardless of its overall prevalence in asthma, severe asthma remains a major challenge for the clinician as these patients require the greatest degree of health care and suffer the most morbidity. Furthermore, patients with severe asthma likely represent a heterogeneous population of patients complicating an already complex situation.

How may severe asthma be defined?

Asthma is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a chronic disease that is characterized by recurrent attacks of breathlessness and wheezing, which varies in severity and frequency from person to person.4 It is this variance in severity and frequency that led the WHO to propose a more universal definition of severe asthma and one that is based on domains in the level of control, current treatment level given or required, responsiveness to treatment, and the associated risks for exacerbations.5 Based on this expanded perspective, a WHO Panel proposed the inclusion of three groups who would meet criteria for the diagnosis of severe asthma (Table 1). One patient group would have underlying features of severe asthma, but are untreated. This group would include patients for whom the diagnosis of asthma was not made, as well as those who, by choice or circumstance, have not appropriately accessed care and treatment. The undiagnosed patient with the potential for severe asthma or severe asthma exacerbations is important at a world health level as it helps to identify high-risk individuals and, if resources are limited, to direct what treatment efforts are available to this group. The second group would include those who are being treated for asthma, but remain symptomatic because of inadequate treatment plans by healthcare providers, poor adherence to medications, incorrect use of delivery devices, and/or adverse environmental conditions. A final group of severe asthma is patients whose disease either requires high dose ICS to achieve disease control or is not fully responsive, or resistant, to appropriate levels of treatments and, as a consequence, do not achieve asthma control.5 It is this final group that is proving to be the most challenging, even for the asthma specialist; given their underlying severity, it is no surprise that this group accounts for over 50% of healthcare utilization related to this disease.6 A principal feature of the expanding definition of severe asthma is the required need and use of high doses of medications, primarily ICS and, or systemic corticosteroids, to achieve control.

TABLE 1.

Definitions of severe asthma by the WHO.

|

From Bousquet, J et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010; 126:926–38.

Other groups have approached the definition of severe asthma from a slightly different angle. The American Thoracic Society (ATS) defined “refractory or severe asthma” based on the identification of two major and seven minor criteria, of which at least one major and two minor requirements must be met for this diagnosis (Table 2).7 This definition of severe asthma may include patients with good disease control and largely focuses on the need for high corticosteroid doses. These criteria have become the working definition for the NHLBI SARP.2

TABLE 2.

Definition: ATS Workshop. Requires Dx and Rx of comorbidities.

|

From: Adapted from Proceedings of the ATS Workshop on Refractory Asthma: Current Understanding, Recommendations, and Unanswered Questions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000; 162:2341–2351.

In 1999, The European Respiratory Society (ERS) task force defined what they termed “difficult/therapy-resistant asthma” as patients with poorly controlled asthma who require continued use of short acting β2-agonists despite guideline-based therapy with reasonable doses of ICS and regular follow up with a respiratory specialist for 6 months.8

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) had initially, like the NAEPP guidelines, classified asthma into four groups based on markers of severity (intermittent plus mild, moderate, and severe persistent) in untreated subjects. Later revisions of the GINA guidelines have added to these levels of severity markers and levels of asthma control.9 Collectively, the definitions of patients with severe asthma focuses on individuals who require primarily large doses of ICS in attempts to achieve disease control.

What are the characteristics of severe asthma?

ENFUMOSA (European Network For Understanding Mechanisms Of Severe Asthma) compared 163 subjects with severe asthma to 158 subjects with mild-to-moderate disease who were well controlled on low doses of ICS.10 Patients with severe asthma were more likely to be female, overweight, and non-atopic. As expected, the severe asthma group had lower forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) values with less reversibility after bronchodilator administration (Table 3). Significant differences were also seen in sputum analysis with severe asthma having a pattern of fewer macrophages and increased neutrophils. Interestingly, no difference was seen in sputum or blood eosinophils between these two groups. However, patients with severe asthma had a significantly greater urinary eosinophil protein X (EPX) and urinary leukotriene E4 (LTE4). Thus, a conclusion from ENFUMOSA was that severe asthma might not simply represent the worsening of a disease process, but a different disease altogether, thus necessitating the identification of specific factors that may lead to the development of this phenotype or phenotypes.

TABLE 3.

Pulmonary function tests (per cent of predicted and blood gases).

| Controlled asthma | Severe asthma | Controlled versus severe asthma | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects n | 130 | 133–153# | |

| FEV1 | 88.5±18.1 | 71.8±23.1 | p<0.001 |

| FEV1 post salbutamol | 97.6±17.8 | 80.9±24.1 | p<0.001 |

| FVC | 103.1±16.1 | 94.1±21.1 | p<0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 89.7±12.8 | 79.9±16.6 | p<0.001 |

| TLC | 104.1±13.4 | 104.4±15.2 | NS |

| RV/TLC | 104.2±23.0 | 113.4±28.0 | p<0.01 |

| KCO | 95.0±16.7 | 90.6±19.0 | p<0.05 |

| Pa,O2 kPa | 12.0±1.6 | 11.2±1.9 | p<0.001 |

| Pa, CO2 kPa | 5.1±0.5 | 4.9±0.5 | p<0.01 |

| pH | 7.41±0.03 | 7.42±0.03 | NS |

| HCO3 mmol-L−1 | 24.8±2.4 | 24.3±2.4 | NS |

| Base excess mmol-L−1 | 0.7±2.3 | 0.4±2.2 | NS |

Data presented as mean±SD. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC: forced vital capacity; TLC: total lung capacity; NS: not significant; RV: residual volume; KCO: carbon monoxide transfer coefficient; Pa,O2: arterial oxygen tension; Pa, CO2: carbon dioxide arterial tension.

Twenty subjects did not perform all spirometry measurements or blood gases.

From: The ENFUMOSA Study Group. Eur Respir J 2003; 22:470–477.

Cluster analyses have also been applied to identify characteristics of severe asthma. In SARP, an extensive phenotypic analysis was used to characterize patients with a wide spectrum of disease severity.11 726 subjects over 12 years of age were clustered based on 34 phenotypic variables. This approach yielded 5 phenotypic clusters of patients with asthma (Tables 4 and 5). Patients in clusters 1 and 2 had, respectively, mild to moderate asthma and had good disease control on current medication use. Patients in clusters 3–5 had more severe asthma as reflected by: lower lung function, a requirement for more controller medications, and, despite high medication use, more frequent exacerbations. The stratified patients differed not only on clinical characteristics, but also on biomarker profiles. While the initial cluster analysis did not include biomarkers in all 726 subjects, subsequent evaluations found significant differences across all clusters for features such as total serum IgE, sputum eosinophils, sputum neutrophils, and methacholine PC20.11 As expected, clusters with more problematic, or severe, disease (Clusters 3–5), had higher levels of inflammatory cells in the sputum (eosinophils and neutrophils) than those with more readily controlled disease.

TABLE 4.

Cluster analysis of clinical characteristics in asthma patients enrolled in SARP.

| Cluster 1 n=110 | Cluster 2 n=321 | Cluster 3 n=59 | Cluster 4 n=120 | Cluster 5 n=116 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at Enrollment | 27 | 33 | 50 | 38 | 49 | <0.0001 |

| Gender (% female) | 80 | 67 | 71 | 53 | 63 | 0.0006 |

| Race (% Cauc/AAOther) | 62/29/9 | 63/30/7 | 73/22/5 | 62/33/5 | 68/20/12 | 0.17 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 27 | 28 | 33 | 31 | 31 | <0.0001 |

| Age of Asthma Onset (yrs) | 11 | 11 | 42 | 8 | 21 | <0.0001 |

| Asthma Duration (yrs) | 15 | 22 | 9 | 30 | 29 | <0.0001 |

| Baseline Lung Function* | ||||||

| FEV1 % Predicted | 102 | 82 | 75 | 57 | 43 | <0.0001 |

| FVC % Predicted | 112 | 93 | 80 | 72 | 60 | <0.0001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.57 | <0.0001 |

| Maximal Lung Function† | ||||||

| FEV1 % Predicted | 113 | 94 | 84 | 76 | 58 | <0.0001 |

| FVC % Predicted | 117 | 100 | 87 | 89 | 75 | <0.0001 |

| Atopy: % with ≥1 pos skin test | 85% | 78% | 64% | 83% | 66% | 0.0008 |

Pre-bronchodilator values (>6 hours withhold of bronchodilators).

Post-bronchodilator values after 6–8 puffs of albuterol.

From: Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181:315–323.

TABLE 5.

Cluster analysis of treatment and health care utilization in the 5 clusters of patients in SARP.

| Cluster 1n=110 | Cluster 2n=321 | Cluster 3n=59 | Cluster 4 n=120 | Cluster 5 n=116 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroid Use (%) | ||||||

| None | 45% | 31% | 14% | 15% | 5% | <0.0001 |

| Low-moderate dose ICS | 38% | 40% | 37% | 18% | 16% | |

| High dose ICS* | 10% | 28% | 49% | 63% | 78% | |

| Oral or Systemic CS** | 11% | 10% | 17% | 39% | 47% | |

| Total Controllers(%) | ||||||

| None | 41% | 26% | 10% | 12% | 4% | <0.0001 |

| ≤2 | 41% | 46% | 35% | 33% | 28% | |

| ≥ 3 | 19% | 29% | 54% | 56% | 67% | |

| Health Care Utilization Pst Yr † | ||||||

| None | 67% | 61% | 41% | 38% | 32% | <0.0001 |

| ≥ 1 Urgent Visit and/or ED | 20% | 25% | 34% | 39% | 42% | |

| ≥ 3 Oral CS burst/yr | 11% | 19% | 36% | 46% | 42% | |

| Hospitalization | 7% | 9% | 15% | 23% | 28% | |

High dose ICS dose equivalent to ≥ 1000 fluticasone propionate daily;

Chronic oral corticosteroids (OCS)≥ 20 mg daily or other systemic steroids in the past 3 months.

Controllers include LTRA, ICS, LABA, theophyllines, OCS, omalizumab. P value from Chi-Square Analysis of ranked ordinal composite variables.

From: Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181:315–323.

Haldar and colleagues in the United Kingdom also performed a cluster analysis of asthma patients with both mild/moderate asthma and severe asthma.12 While some overlap exists between the clusters identified in SARP, there were important differences as well, possibly reflecting the approaches of each study. The Haldar study measured sputum eosinophils in all patients and used this variable in their cluster analysis. Both studies identified a cluster of older females, mostly with elevated BMIs, who had late onset and largely non-atopic asthma. Both groups also identified an early onset, atopic cluster of patients who required larger amounts of corticosteroids (both inhaled and systemic), but continued to have symptoms including increases in unscheduled healthcare utilization. Lastly, both groups identified a late-onset, less atopic group with significantly decreased lung function and a reduced male:female ratio. Interestingly, in SARP, this cluster was highly symptomatic while in the Haldar study this patient group had evidence of ongoing eosinophilic inflammation without the expected degree of symptomatology.11,12

While the previously referenced studies were limited to adults, Fitzpatrick and colleagues specifically assessed severe asthma in children who were also enrolled in SARP.13 Seventy-five patients underwent baseline characterization including spirometry, lung volume testing, methacholine bronchoprovocation studies, measurement of exhaled nitric oxide, and evaluation of allergen sensitization (Table 6). Those with severe asthma were more likely to be African American and younger at the time of their diagnosis. Severe asthma subjects also had lower baseline FEV1 values, but demonstrated greater reversibility after bronchodilator administration. Children in the severe asthma group also had more exacerbations and more healthcare utilization. The majority of subjects in both groups showed evidence of allergen sensitization. However, unlike adults in the ENFUMOSA study, children with severe asthma had higher total serum IgE levels as well as greater numbers of positive skin prick tests than youngsters with mild-to-moderate asthma. An important conclusion to this study is that in children, unlike adults, severe asthma may be less phenotypically heterogeneous.

TABLE 6.

Characteristics of children with asthma*

| Severe (n = 39) | Mild-to-moderate (n = 36) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 10 (6–17) | 10 (6–15) | .119 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 9 (23%) | 26 (72%) | .000 |

| African American | 27 (69%) | 7 (19%) | |

| Other | 3 (8%) | 3 (8%) | |

| Male | 21 (54%) | 18 (50%) | .459 |

| Female | 18 (46%) | 18 (50%) | |

| Age at diagnosis (mo) | 22 (2–144) | 60 (2–156) | .000 |

| Daily daytime symptoms† | 19 (49%) | 6 (17%) | .007 |

| Daily nocturnal symptoms | 11 (28%) | 0 | .030 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 27 (69%) | 15 (42%) | .021 |

| Immediate family history of asthma | 31 (79%) | 19 (53%) | .027 |

| Total hospital admissions | 4 (0–25) | 0 (0–3) | .000 |

| Total intensive care unit admissions | 1 (0–10) | 0 (0–1) | .000 |

| Daily medications | |||

| Short-acting β-agonists‡ | 22 (56%) | 3 (8%) | |

| Long-acting β-agonists§ | 33 (85%) | 23 (64%) | |

| Montelukast (Merck, Whitehouse Station, NJ) | 39 (100%) | 23 (64%) | |

| Prednisone | 8 (21%) | 0 | |

Values represent the frequency (percentage) or the median (range).

Six subjects with mild-to-moderate asthma experienced bronchospasm with daily participation in organized sports.

Three subjects with mild-to-moderate asthma used prophylactic β-agonists before daily sports participation.

All children with long-acting β-agonist use were on fluticasone/salmeterol combination therapy.

From: Fitzpatrick, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006; 118:1218–25.

Jenkins et al. compared children and adults with severe asthma.14 Using a retrospective, cross-sectional study of 275 patients referred to a tertiary center for difficult to control asthma, they found that children with severe asthma were more likely to be male reflecting the sex distribution at a younger age. They also found that children with severe asthma tended to be more responsive to glucocorticoids in vitro and tended to have less impairment in lung function compared to adult counterparts, suggesting a progressive decline in lung function over time in patients with early onset disease who eventually develop more severe disease.

Overall, these studies show that severe asthma is a protean disease, and that a better understanding of the different phenotypic variants may allow for not only greater understanding of the disease, but also direction for improved treatment strategies.

What are the underlying mechanisms of severe asthma?

When compared with many other chronic disease states, the underlying mechanisms of asthma, including severe asthma, are incompletely understood.15 Research has initially focused on the pattern of inflammatory cells in the sputum and airway tissue biopsies to identify unique features of more severe disease. Following this strategy, Wenzel and colleagues identified two groups of patients with severe asthma based on levels of eosinophils in endobronchial tissue specimens.16 One group of patients with severe asthma had increased numbers of eosinophils despite long-term corticosteroid treatment compared to the other group with severe disease who actually had fewer airway eosinophils than control subjects. This latter group, termed eosinophil-negative severe asthma, had primarily a neutrophilic infiltration of the endobronchial tissue. In this particular study, eosinophil levels in endobronchial tissue samples varied widely amongst all levels of asthma severity. While eosinophil counts were higher in asthma than controls, there was no significant difference between airway tissue eosinophil levels of severe asthma and mild-to-moderate disease. Clinical measurements of disease severity were also similar between these two severe groups. This study, as well as other investigations, has shown that although airway tissue eosinophilia likely contributes to the pathogenesis of asthma, it does not always necessarily correlate with disease severity and may be less important than other markers of airway tissue inflammation, such as neutrophilia, in defining severe asthma.17 How much of the airway neutrophilia is attributable to the effects of long-term corticosteroid use is unclear, although it should be noted that Wenzel et al. did not note any differences in corticosteroid use between the eosinophil-positive and eosinophil-negative groups.16

The airway epithelium, which was once considered as only a barrier between the external environment and the lung parenchyma, is increasingly recognized as a major component in the pathogenesis of asthma.18 In severe asthma, the restoration of injured epithelium is compromised and, as a consequence, is proposed to become a chronic, unhealing wound.18 As a response to chronic damage, the underlying mesenchyme releases a variety of growth factors in an attempt to heal the wound. The resulting aberrant communication between the epithelium and mesenchyme leads to increased extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition, fibrosis, and airway smooth muscle proliferation.19 Holgate and colleagues have likened this response to the epithelial-mesangial trophic unit (EMTU), which is important in lung morphogenesis and, may perhaps, become reactivated in severe asthma.19,18 The complex interactions between the EMTU and the mediators of Th2-type inflammation likely drive the development of disease by increasing both chronic airway inflammation and airway wall remodeling, a process which can then become ongoing and independent of the initiating inflammation (Figure 1).18 This theory differs from the traditional model of asthma pathogenesis whereby inflammation and remodeling are both increased over time and with disease severity, but do so in a more parallel and related fashion with inflammation directly leading to remodeling.18

Figure 1.

Inflammatory and remodelling responses in asthma with activation of the epithelial mesenchymal trophic unit. Epithelial damage alters the set point for communication between bronchial epithelium and underlying mesenchymal cells, leading to myofibroblast activation, an increase in mesenchymal volume, and induction of structural changes throughout airway wall. Adapted from J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003; 111: 215–25. From: Holgate and Polosa. Lancet 2006; 368:780–93.

Airway remodeling has been used as an all-encompassing term to describe the morphologic changes seen in chronic severe asthma. One of the most extensively studied components of remodeling has been subepithelial basement membrane (SBM) thickness. Some studies find a correlation between SBM thickness and asthma severity, whereas others have shown no difference between severe and mild-to-moderate asthma.20,21 Increases in the goblet cell to ciliated epithelial cell ratio are seen in severe asthma and can lead to increased mucous production with plugging of small airways further limiting airflow.15 Increased airway smooth muscle mass (because of increases in size and number of smooth muscle bundles) is found in severe asthma and is noted from the trachea to the smallest respiratory bronchioles and alveolar ducts.22 An increase in smooth muscle, along with greater matrix deposition, disruption of elastin filaments, and increased deposition of collagen and proteoglycans, leads to stiffer airways and a greater likelihood of fixed airflow obstruction.23

Decreased responsiveness to both inhaled and systemic corticosteroids also plays a prominent and defining role in severe asthma. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain a lack of corticosteroid responsiveness including changes in the expression of corticosteroid receptors, decreased production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in response to corticosteroids, and reduced activation of anti-inflammatory genes.23 All of these, plus other likely factors, result in corticosteroid treatment being less effective in severe disease.

As mentioned previously, the mechanisms underlying severe asthma have yet to be fully understood. Differences obviously exist between the airways of severe asthma and those of normal controls and mild-to-moderate disease. The consequences of these differences are becoming more fully recognized, in general, and within different populations of asthma patients. As this information emerges, it is anticipated that more targeted and effective therapies for severe asthma will appear.

What are management strategies of severe asthma?

Management of severe asthma should begin with confirming the correct diagnosis. The NHLBI Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3) suggests that a thorough history and physical examination should be performed along with spirometry, which should include an assessment of reversibility.24 Although other studies are not routinely recommended, they should be obtained if the diagnosis is unclear and include additional pulmonary studies to exclude COPD (diffusing capacity), restrictive defects (lung volumes), and vocal cord dysfunction (evaluation of inspiratory flow-volume loops and direct laryngeal observation).24 If asthma is strongly suspected, but the spirometry is normal, bronchoprovocation studies should be considered to determine whether hyperresponsiveness exits. In the absence of airway hyperresponsiveness, the diagnosis of asthma is less likely. Lastly, radiographic imaging of the chest using plain films or computed tomography (CT) may be beneficial in some cases, largely to identify diseases other than asthma.

Asthma can coexist with other conditions that contribute to increased severity and poor control. Gastroesophageal reflux disease can worsen asthma and should be treated aggressively with diet/lifestyle modifications and/or use of an H2 receptor antagonist or a proton pump inhibitor.24 Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), or other allergic mycoses, can complicate asthma. Patients must meet criteria for the diagnosis of ABPA: (1) asthma, (2) proximal bronchiectasis (dilated bronchi in the inner two thirds of the chest field on CT), (3) immediate cutaneous reactivity to Aspergillus species or Aspergillus fumigatus, (4) an elevated total serum IgE (>417 kU/L or 1000 ng/mL), and (5) the presence of serum IgE to A. fumigatus and/or serum IgG to A. fumigatus.25 Treatment of ABPA consists of optimal asthma therapy plus oral corticosteroids.25 Itraconazole has also shown benefit, but as adjunctive, not primary, therapy.25 There are also data that certain persistent respiratory tract infections, Mycoplasma or Chlamydophilia pneumonia can contribute to the severity of asthma and treatment with macrolide antibiotics can result in improved control for some patients.26 Similar treatment approaches can be applied to other fungal organisms.27 Lastly, appropriate management of rhinitis, especially when respiratory allergen sensitization and exposure are involved, may improve asthma symptoms.28 Sinusitis should be treated with intranasal corticosteroids and antibiotics when indicated.24 Allergen immunotherapy should be considered if respiratory allergen sensitivity is present and contributing to disease severity.24 However, in severe disease a concern exists that anaphylactic reactions to immunotherapy may have profound effects on already compromised lung function.29 In addition, like in other diseases, psychological diseases can complicate management of asthma. Depression is common in asthma and its role contributing to disease severity is not well established.30 Management of these and other comorbid conditions can enhance the effectiveness of treatment of severe asthma.

Patients with severe asthma should be closely followed, with visits every 2–6 weeks in patients who are just starting therapy or have recently stepped up their level of treatment. Follow up visits at 1–6 month intervals may then become appropriate for those who have achieved sustained control of asthma, with shorter intervals reserved for those with more severe or brittle disease.24 Spirometry should be performed at any visit when a loss of asthma control appears. It is recommended that spirometry be performed at least every 1–2 years, regardless of the level of control, though this is perhaps not sufficiently frequent, especially in severe asthma.24 It is important to routinely assess each patient’s technique in using asthma medications and to assure that the asthma action plan is understood. Some centers now obtain measurements of the fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FENO) in asthma patients at each clinic visit and studies have suggested that this could be an effective means of monitoring the disease course, treatment adherence, and guiding treatment.31 Because treatment adherence is common at all levels of asthma severity, efforts to assess this component of management always needs to be considered before concluding that a medication is not effective.

What treatment approaches are considered for severe asthma?

The initial management of severe asthma should focus on the treatment steps recommended by guidelines such as EPR3.24 Patients with severe asthma should be started on Step 4 therapy which includes maintenance use of a medium dose inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) in combination with either a long-acting β2 agonist (LABA) or a leukotriene modifier, although some studies have raised doubt as to the efficacy of the latter class of medications as add-on therapy in severe asthma.32 Often, patients are also given a short course of oral prednisone to first achieve control, determine the degree of which lung function can be improved, and stabilize the disease. Often patients with severe asthma do not achieve good levels of control even on Step 5 or Step 6 therapy, which can include daily oral corticosteroids. It is this group of patients that remains the most challenging for even the most experienced asthma specialist.

The NHLBI guidelines recommend the consideration of omalizumab as add on therapy for patients who are not controlled with Step 5 or 6 therapy and have evidence of respiratory allergen sensitivity.24 Omalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to IgE, which forms complexes with free IgE, thus reducing this antibody from binding to mast cells and basophils.33 Omalizumab also down-regulates the expression of the FcεRI (high-affinity IgE) receptor.34

Several studies have shown the effectiveness of omalizumab as add-on therapy in severe asthma. Humbert and colleagues randomized 419 patients with severe allergic asthma and poor control to add-on omalizumab or placebo.35 Omalizumab significantly reduced clinically significant asthma exacerbations, severe exacerbations, and emergency room visits for asthma exacerbations. Bousquet and colleagues pooled data from seven studies that evaluated the effectiveness of omalizumab as add-on therapy in severe allergic asthma.36 Five of these studies were double-blinded and compared omalizumab to placebo, while two were open label studies and evaluated the addition of omalizumab to current asthma therapy. Of the 4308 patients included, 93% met criteria for severe persistent asthma by GINA guidelines. The collective data found overall reductions in exacerbation rates of 38% and 47% in emergency visits.

A prospective multicenter study by Hanania and colleagues evaluated 850 patients with severe allergic asthma, which was inadequately controlled on high dose ICS/LABA (fluticasone 500 mcg/salmeterol 50 mg twice per day) plus or minus other controller medications, including oral corticosteroids.37 A 25% relative reduction in exacerbations was found in the omalizumab treated group as well as improved scores on asthma control tests, reduced daily SABA use, and decreased asthma symptom scores.

Omalizumab has proven to be a safe and effective adjunctive therapy in patients with allergic asthma that is not well controlled on high levels of asthma therapy.33,35,36,37 The dosing and treatment intervals are based on body weight and pretreatment serum IgE levels. There is no serological test to monitor the effectiveness of omalizumab therapy, as measurements of free IgE are not commercially available.

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology (ACAAI) issued a joint task force report in 2007 stating that patients started on omalizumab should sign an informed consent, have an epinephrine autoinjector available at the time of injections and be familiar with the signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis, receive only omalizumab in a healthcare setting equipped to manage anaphylaxis, have a preinjection health assessment including a measurement of lung function, and be supervised for a period of 2 hours after each of the first 3 injections and for 30 minutes after subsequent injections.38

While the data for the use of omalizumab in asthma are favorable, recommendations for the duration of long-term management of patients on omalizumab are sparse. Most recommend an initial trial of at least twelve weeks39 and periodically thereafter to assess the observed efficacy to determine if continuation of omalizumab would be of further benefit. It is also recommended to continue omalizumab for as long as there is evidence of ongoing clinical benefit.40 Large-scale studies examining long-term benefits of omalizumab are ongoing. One study, the EXCELS study, suggests continued efficacy at 2 years of treatment in a cohort of approximately 5000 patients with moderate to severe asthma.41 A small study by Pace and colleagues reported increases in FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio were more pronounced at years 5–7 of omalizumab therapy than in the first four years of therapy.42 Data from the EXCELS study and other ongoing studies will provide insight into the benefits of long term omalizumab therapy and give guidance on how long clinicians should continue omalizumab therapy when a clinical response has been achieved.

Other monoclonal antibodies targeting key cytokines involved in asthma have been studied extensively. Interleukin (IL) -5 is central to eosinophil biology and increased in some asthma patients; based on these findings, its inhibition should be beneficial in asthma.43 Early studies with an anti-IL-5, mepolizumab, failed to show consistent evidence of clinical benefit in a broad group of asthmatic patients, despite reducing blood and bronchial tissue eosinophils.43 Later studies, however, found mepolizumab treatment significantly reduced exacerbations in subgroups of asthmatic patients with severe disease who had ongoing evidence of eosinophilic inflammation despite ongoing corticosteroid therapy.44,45,46 Castro and colleagues examined the effects of reslizumab, another monoclonal antibody to IL-5, in patients with moderate to severe asthma with persistent sputum eosinophilia and found a reduction in blood and sputum eosinophils as well as an improvement in FEV1.47 There was a non-significant trend towards an improvement in asthma symptom scores. Thus, while anti-IL-5 therapy may not provide benefit to all patients with severe asthma, it does appear to have a therapeutic potential to reduce exacerbations in subgroups with severe eosinophilic disease.

Other Th-2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 have been cited as possible targets for asthma therapy. A monoclonal antibody to IL-4, pascolizumab, had disappointing results in asthma patients.48 Monoclonal antibodies to IL-13, in contrast, have shown mixed results. Anrukizimab showed efficacy in patients with mild asthma, but not in those individuals with more severe disease.49 Lebrikizumab, and anti-IL-13, improved FEV1 values in patients with severe asthma that was inadequately controlled on ICS; symptoms were not affected.50 Lebrikizumab was most effective in subjects who had elevated levels of periostin, a marker of Th-2 inflammation (Figure 2), and FeNO. These observations raise the possibility that some biomarkers may identify patients most likely to respond to a regulation of the Th2 profile. Lebrikizumab is currently in Phase III clinical trials.51 AMG317, a monoclonal antibody to the IL-4Rα chain, shared by IL-4 and IL-13, failed to demonstrate significant clinical efficacy.52

Figure 2.

Relative Change in Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second (FEV1) in the Intention-to-Treat Population. At week 12, the increase from baseline in FEV1 was higher by 5.5 percentage points (95% CI, 0.8 to 10.2) in the lebrikizumab group than in the placebo group (mean [±SE] change, 9.8±1.9% vs. 4.3±1.5%; P = 0.02) (Panel A). In the subgroup of patients with high periostin levels (high Th2), the relative increase from baseline FEV1 was higher by 8.2 percentage points (95% CI, 1.0 to 15.4) in the lebrikizumab group than in the placebo group (mean change, 14.0±3.1% vs. 5.8±2.1%; P = 0.03) (Panel B). Among patients in the low-periostin subgroup (low Th2), the relative increase from baseline FEV1 was higher by 1.6 percentage points (95% CI, –4.5 to 7.7) in the lebrikizumab group than in the placebo group (mean change, 5.1±2.4% vs. 3.5±2.1%; P = 0.61) (Panel C). From Corren J, Lemanske RF, Hanania NA, et al. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1088–1098.

Bronchial thermoplasty consists of administering thermal energy during bronchoscopy with the intent to decrease the smooth muscle mass of the airway.53 Castro and colleagues randomized 288 patients with moderate to severe asthma to either bronchial thermoplasty or a sham control bronchoscopy. All patients underwent three bronchoscopy procedures. Patients in the bronchial thermoplasty group had greater improvement in asthma control scores compared with those in the sham treatment group. Over the 52 weeks following treatment, those patients who received active thermoplasty had fewer exacerbations, emergency department visits, and days missed from work (Figure 3). Pavord and colleagues showed improvements in asthma control test scores and prebronchodilator FEV1 and reductions in rescue medication use with bronchial thermoplasty.54 Both studies showed an initial increase in asthma symptoms immediately following bronchoscopy and thermoplasty. With increased experience and greater understanding of the mechanism of action, thermoplasty may become a more widespread treatment option in severe asthma.

Figure 3.

Healthcare utilization events during the posttreatment period. Severe exacerbations (exacerbation requiring treatment with systemic corticosteroids or doubling of the inhaled corticosteroids dose), emergency department visits, and hospitalizations occurring in the post-treatment period. Open bars, sham; shaded bars, bronchial thermoplasty. All values are means 6 SEM statistical significance. From: Castro M, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181:116–124.

Bel and colleagues sought to determine whether those patients with severe eosinophilic asthma and persistent sputum eosinophilia, despite high dose inhaled or oral corticosteroid therapy, would respond if additional doses of corticosteroids were given parenterally.55 Twenty-two patients with severe eosinophilic asthma were randomized to receive 120 mg of intramuscular triamcinolone acetonide or a matched placebo. Two weeks after administration of triamcinolone, sputum eosinophils were significantly reduced, as well as improved post-bronchodilator FEV1 values and Borg scores, a subjective score of dyspnea. Significant reductions in FENO and rescue medication usage were also seen. This study illustrated that even severe, and apparently refractory, asthma is not necessarily a static disease and may still be responsive to high dose parenteral corticosteroids.

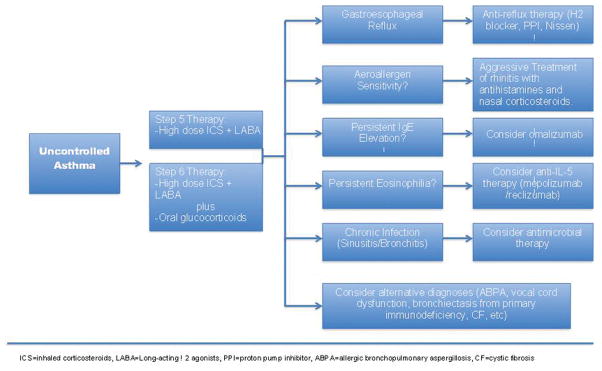

The management of severe asthma is often a significant challenge to even the most experienced asthma specialist. The development of a logical and schematic approach to the treatment of patients with severe asthma is paramount to providing the most effective care to those with the most demanding disease (Figure 4). Such an approach should be developed with the knowledge that severe asthma is a heterogeneous disease and each patient is likely to respond differently to combinations of therapy depending on their particular phenotype. Attention to an individual’s comorbidities can also lead to better asthma control. A personalized approach to the treatment of severe asthma has been illustrated by Richard Martin and colleagues who used bronchoscopy to evaluate and guide treatment of 58 patients with difficult to treat asthma.56 Out of the recruited 58 patients, 22 had bronchoscopic evidence of gastroesophageal reflux, 13 had subacute bacterial infection, and 4 had evidence of tissue eosinophilia. 13 had a combination of two or more of these findings, and 6 had a nonspecific phenotype. Patients with evidence of gastroesophageal reflux underwent intensive anti-reflux therapy with 7 requiring Nissen fundoplication. Patients with evidence of subacute bacterial infection, most of whom had either Mycoplasma or Chlamydophilia, were treated with appropriate antibiotics. The patients with evidence of tissue eosinophilia were considered to have a Th2 phenotype and received omalizumab. In each case, a specific treatment for a defined phenotype resulted in an improvement in both lung function and symptom scores 3–6 months later. This study serves as a prime example to identify and treat specific etiological factors in individual patients which may lead to improved lung function and symptom control.

Figure 4.

Personalized treatment algorithm for difficult to control asthma patients.

The treatment of severe asthma is not straightforward and evolves in each individual patient over his or her lifetime. Using a personalized treatment approach designed to affect specific phenotype characteristics of a patient’s disease should allow for better asthma control and a better quality of life. Prior to an individualized approach, it is appropriate to follow guideline-based therapy with high-dose ICS plus LABA, the preferred initial directive. Moreover, in patients who have evidence of allergic rhinosinusitis, identification of allergen sensitivities may allow for allergen avoidance (i.e. removing pets from the home) or immunotherapy. Allergic rhinosinusitis should be aggressively treated with antihistamines and nasal corticosteroids as poor control of upper airway symptoms can lead to worsening of asthma control.28 Patients with chronic sinusitis should be treated with appropriate courses of antibiotics, often in conjunction with corticosteroids, as this can improve asthma symptoms.57 Patients with nasal polyps often have aspirin sensitivity. There are data that aspirin desensitization may be of benefit in some patients.58 Omalizumab should be considered in uncontrolled patients who qualify for its use. Vocal cord dysfunction can coexist with and mimic asthma. Referral to otolaryngology for evaluation of vocal cord motion can be instrumental in determining exactly where a patient’s symptoms are originating. As mentioned previously, gastroesophageal reflux should be treated in patients for whom it is problematic. Ensuring that patients have an appropriate level of knowledge of asthma and that they employ proper techniques with asthma inhalers is often overlooked, but of considerable importance. If symptoms remain problematic, a more in depth look for other disorders that may be worsening or masquerading as asthma is warranted. Finally, it is always essential to determine the level of medication adherence as a contributing factor to an inadequate response to treatment.

Conclusion

Regardless of how it is defined, severe asthma represents a heterogeneous disorder that, despite intensive research, still presents a significant challenge to the treating physician. The importance of understanding that specific severe asthma phenotypes exist and recognizing important comorbidities cannot be understated. Guideline-based care should be heeded, but its limitations should be recognized in this important subpopulation of asthma. As our understanding of this asthma phenotype improves, the availability of different treatment modalities will continue to expand and with these advances improved outcomes.

Research into severe, uncontrolled asthma now appropriately dominates the asthma research landscape. Changes on the horizon, including gene-based treatment strategies, are becoming more of a reality. In adults with severe asthma, treatment with omalizumab and anti-IL-5 antibodies has shown promise as a more personalized approach in specific phenotypes. Research in the pediatric groups is ongoing as well and soon a more tailored approach to therapy may be possible in that age group. Overall, the clinician must recognize the changing nature of the field and the availability of new treatment modalities so that all patients with severe asthma will be assured the best possible care.

Abbreviations

- ABPA

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis

- ATS

American Thoracic Society

- COPD

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- CT

Computed Tomography

- ECM

Extracellular Matrix

- EMTU

Epithelial Mesangial Trophic Unit

- EPR3

Expert Panel Report 3

- ERS

European Respiratory Society

- FENO

Fraction of Exhaled Nitric Oxide

- FEV1

Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second

- GINA

Global Initiative for Asthma

- ICS

Inhaled Corticosteroid

- LABA

Long Acting β2-Agonist

- NHLBI

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute

- PC20

Provocative concentration of a substance causing a 20% fall in FEV1

- SARP

Severe Asthma Research Program

- SBM

Subepithelial Basement Membrane

- WHO

World Health Organization

References

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Bailey C, et al. Trends in asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality in the United States, 2001–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarjour NN, Erzurum SC, Bleecker ER, et al. Severe asthma: lessons learned from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:356–62. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1317PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bateman ED, Boushey HA, Bousquet J, et al. Can guideline-defined asthma control be achieved? The Gaining Optimal Asthma ControL study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:836–44. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-033OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Office of Health Communications and Public Relations. Asthma. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bousquet J, Mantzouranis E, Cruz AA, et al. Uniform definition of asthma severity, control, and exacerbations: document presented for the World Health Organization Consultation on Severe Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:926–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desai D, Brightling C. Cytokine and anti-cytokine therapy in asthma: ready for the clinic? Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;158:10–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03998.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(ATS) ATS. Proceedings of the ATS workshop on refractory asthma: current understanding, recommendations, and unanswered questions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2341–51. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.ats9-00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung KF, Godard P, Adelroth E, et al. Difficult/therapy-resistant asthma: the need for an integrated approach to define clinical phenotypes, evaluate risk factors, understand pathophysiology and find novel therapies. ERS Task Force on Difficult/Therapy-Resistant Asthma. European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:1198–208. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13e43.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:143–78. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Group TES. The ENFUMOSA cross-sectional European multicentre study of the clinical phenotype of chronic severe asthma. European Network for Understanding Mechanisms of Severe Asthma. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:470–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00261903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:315–23. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, et al. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:218–24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzpatrick AM, Gaston BM, Erzurum SC, Teague WG. Features of severe asthma in school-age children: Atopy and increased exhaled nitric oxide. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins HA, Cherniack R, Szefler SJ, Covar R, Gelfand EW, Spahn JD. A comparison of the clinical characteristics of children and adults with severe asthma. Chest. 2003;124:1318–24. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wenzel S. Mechanisms of severe asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:1622–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2003.01799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenzel SE, Schwartz LB, Langmack EL, et al. Evidence that severe asthma can be divided pathologically into two inflammatory subtypes with distinct physiologic and clinical characteristics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1001–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9812110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wenzel SE, Szefler SJ, Leung DY, Sloan SI, Rex MD, Martin RJ. Bronchoscopic evaluation of severe asthma. Persistent inflammation associated with high dose glucocorticoids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:737–43. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9610046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davies DE, Wicks J, Powell RM, Puddicombe SM, Holgate ST. Airway remodeling in asthma: new insights. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:215–25. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.128. quiz 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight DA, Holgate ST. The airway epithelium: structural and functional properties in health and disease. Respirology. 2003;8:432–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2003.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chetta A, Foresi A, Del Donno M, Bertorelli G, Pesci A, Olivieri D. Airways remodeling is a distinctive feature of asthma and is related to severity of disease. Chest. 1997;111:852–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.4.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wenzel SE, Balzar S, Cundall M, Chu HW. Subepithelial basement membrane immunoreactivity for matrix metalloproteinase 9: association with asthma severity, neutrophilic inflammation, and wound repair. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1345–52. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sutherland ER, Martin RJ, Bowler RP, Zhang Y, Rex MD, Kraft M. Physiologic correlates of distal lung inflammation in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1046–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holgate ST, Polosa R. The mechanisms, diagnosis, and management of severe asthma in adults. Lancet. 2006;368:780–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69288-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Heart L Blood Institute. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR-3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma-Summary Report 2007. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:S94–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberger PA. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110:685–92. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.130179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraft M, Cassel GH, Pak J, Martin RJ. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae in Asthma. Chest. 2002;121:1782–1788. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.6.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bush RK, Swenson C, Fahlberg B, Evans MD, Esch R, Busse WW. House dust mite sublingual immunotherapy: Results of a US trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:974–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simons FE. Allergic rhinobronchitis: the asthma-allergic rhinitis link. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:534–40. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70320-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Viswanathan RK, Busse WW. Allergen immunotherapy in allergic respiratory diseases: from mechanisms to meta-analyses. Chest. 2012;141:1303–14. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenkranz MA, Davidson RJ. Affective neural circuitry and mind-body influences in asthma. NeuroImage. 2009;47:972–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith AD, Cowan JO, Brassett KP, Herbison GP, Taylor DR. Use of exhaled nitric oxide measurements to guide treatment in chronic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2163–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson DS, Campbell D, Barnes PJ. Addition of leukotriene antagonists to therapy in chronic persistent asthma: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;357:2007–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05113-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. Omalizumab, anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:184–90. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacGlashan DW, Jr, Bochner BS, Adelman DC, et al. Down-regulation of Fc(epsilon)RI expression on human basophils during in vivo treatment of atopic patients with anti-IgE antibody. J Immunol. 1997;158:1438–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humbert M, Beasley R, Ayres J, et al. Benefits of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002 step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy. 2005;60:309–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bousquet J, Cabrera P, Berkman N, et al. The effect of treatment with omalizumab, an anti-IgE antibody, on asthma exacerbations and emergency medical visits in patients with severe persistent asthma. Allergy. 2005;60:302–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hanania NA, Alpan O, Hamilos DL, et al. Omalizumab in severe allergic asthma inadequately controlled with standard therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:573–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-9-201105030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox L, Platts-Mills TA, Finegold I, Schwartz LB, Simons FE, Wallace DV. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology/American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology Joint Task Force Report on omalizumab-associated anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:1373–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strunk RC, Bloomberg GR. Omalizumab for asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2689–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct055184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holgate S, Buhl R, Bousquet J, Smith N, Panahloo Z, Jimenez P. The use of omalizumab in the treatment of severe allergic asthma: A clinical experience update. Respir Med. 2009;103:1098–113. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eisner MD, Zazzali JL, Miller MK, Bradley MS, Schatz M. Longitudinal changes in asthma control with omalizumab: 2-year interim data from the EXCELS Study. J Asthma. 2012;49:642–8. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.690477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pace E, Ferraro M, Bruno A, Chiappara G, Bousquet J, Gjomarkaj M. Clinical benefits of 7 years of treatment with omalizumab in severe uncontrolled asthmatics. J Asthma. 2011;48:387–92. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2011.561512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Busse WW, Ring J, Huss-Marp J, Kahn JE. A review of treatment with mepolizumab, an anti-IL-5 mAb, in hypereosinophilic syndromes and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:803–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nair P, Pizzichini MM, Kjarsgaard M, et al. Mepolizumab for prednisone-dependent asthma with sputum eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:985–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haldar P, Brightling CE, Hargadon B, et al. Mepolizumab and exacerbations of refractory eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:973–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:651–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60988-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castro M, Mathur S, Hargreave F, et al. Reslizumab for poorly controlled, eosinophilic asthma: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1125–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0396OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hart TK, Blackburn MN, Brigham-Burke M, et al. Preclinical efficacy and safety of pascolizumab (SB 240683): a humanized anti-interleukin-4 antibody with therapeutic potential in asthma. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;130:93–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gauvreau GM, Boulet LP, Cockcroft DW, et al. Effects of interleukin-13 blockade on allergen-induced airway responses in mild atopic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1007–14. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201008-1210OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Corren J, Lemanske RF, Hanania NA, et al. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1088–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomas NC, Patel M, Smith AD. Librikizumab in the personalized management of asthma. Biologics: Targets and Therapy. 2012;6:329–335. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S28666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corren J, Busse W, Meltzer EO, et al. A randomized, controlled, phase 2 study of AMG 317, an IL-4Ralpha antagonist, in patients with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:788–96. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200909-1448OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Castro M, Rubin AS, Laviolette M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bronchial thermoplasty in the treatment of severe asthma: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:116–24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0354OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pavord ID, Cox G, Thomson NC, et al. Safety and efficacy of bronchial thermoplasty in symptomatic, severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1185–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-571OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.ten Brinke A, Zwinderman AH, Sterk PJ, Rabe KF, Bel EH. “Refractory” eosinophilic airway inflammation in severe asthma: effect of parenteral corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:601–5. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-440OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Good JT, Jr, Kolakowski CA, Groshong SD, Murphy JR, Martin RJ. Refractory asthma: importance of bronchoscopy to identify phenotypes and direct therapy. Chest. 2012;141:599–606. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rachelefsky GS, Katz RM, Siegel SC. Chronic sinus disease with associated reactive airway disease in children. Pediatrics. 1984;73:526–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.White AA, Stevenson DD. Aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease: Update on pathogenesis and desensitization. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33:588–594. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]