Abstract

To determine antimicrobial drug resistance mechanisms of Shigella spp., we analyzed 344 isolates collected in Switzerland during 2004–2014. Overall, 78.5% of isolates were multidrug resistant; 10.5% were ciprofloxacin resistant; and 2% harbored mph(A), a plasmid-mediated gene that confers reduced susceptibility to azithromycin, a last-resort antimicrobial agent for shigellosis.

Keywords: Shigella, antimicrobial treatment, multidrug resistance, resistance genes, ciprofloxacin, cephalosporins, azithromycin, antimicrobial resistance, bacteria

Shigella spp. are the etiologic agents of acute invasive intestinal infections clinically manifested by watery or bloody diarrhea. Shigellosis represents a major burden of disease, especially in developing countries, and is estimated to affect at least 80 million persons, predominantly children, each year (1). Disease may be caused by any of the 4 Shigella species: S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, and S. sonnei. In industrialized countries, the most common species is S. sonnei, but this species is spreading intercontinentally to developing countries as a single, rapidly evolving lineage (2). By contrast, in developing countries, the predominant species is S. flexneri, which is characterized by long-term persistence of sublineages in shigellosis-endemic regions with inadequate hygienic conditions and unsafe water supplies (3). More rarely isolated are S. dysenteriae, responsible for large epidemics in the past, and S. boydii (4). Although shigellosis is principally a self-limiting disease, the World Health Organization guidelines recommend antimicrobial drug treatment as a means of reducing deaths, disease symptoms, and organism-excretion time; the current drug of choice is ciprofloxacin (1). Of growing concern is multidrug resistance, and in particular the increasing rate of resistance to ciprofloxacin reported for Shigella isolates from Asian and African regions (5). Furthermore, resistance to recommended second-line antimicrobial drugs, such as the third-generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone and the macrolide azithromycin, is emerging (1).

The Study

To determine antimicrobial drug resistance profiles, we analyzed clinical isolates representing 344 Shigella spp. collected during 2004–2014. We focused on molecular resistance mechanisms that promote resistance to currently recommended antimicrobial drugs.

We performed susceptibility testing by using the Kirby–Bauer disk-diffusion method. Results were interpreted according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute performance standards (6). All 344 isolates were screened for plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) genes (7). A subset of 34 isolates eliciting reduced susceptibility to nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, or both, and representing different years of isolation was subjected to PCR-based detection of mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of the gyrA and parC genes (7). Isolates showing an extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) phenotype were screened by PCR for the presence of genes belonging to the blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M families, by using primers described previously (8). All 344 isolates were analyzed for mph(A) by PCR by using previously published primers (9). Resulting amplicons were purified and sequenced. For database searches, we used blastn (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/).

Multidrug resistance was defined as resistance to >3 classes of antimicrobial agents. Multidrug resistance was detected in 150 (83.8%) of the S. sonnei, 84 (78.5%) of the S. flexneri, 20 (60.6%) of the S. dysenteriae, and 16 (64%) of the S. boydii isolates (Table 1).

Table 1. Antimicrobial drug resistance of 344 Shigella spp. isolates, Switzerland, 2004–2014 .

| Agent | No. (%) isolates |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. sonnei, n = 179 | S. flexneri, n = 107 | S. dysenteriae, n = 33 | S. boydii, n = 25 | |

| Ampicllin | 31 17.3) | 73 (68.2) | 19 (57.6) | 12 (48) |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 (0) |

| Cephalothin | 12 (6.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cefotaxime | 8 (4.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nalidixic acid | 49 (27.4) | 15 (14) | 2 (6) | 2 (8) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 27 (15) | 9 (8.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Azithromycin* | 2 (1.1) | 5 (4.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Trimethoprim | 172 (96) | 70 (65.4) | 20 (60.6) | 15 (60) |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 151 (84.4) | 71 (66.4) | 19 (57.6) | 16 (64) |

| Kanamycin | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Gentamicin | 4 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Streptomycin | 163 (91) | 81 (75.7) | 24 (72.7) | 18 (72) |

| Tetracycline | 145 (81) | 83 (77.6) | 22 (66.6) | 13 (52) |

| Chloramphenicol | 6 (3.4) | 56 (52.3) | 9 (27.3) | 2 (8) |

*For azithromycin, no Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoints for Enterobacteriaceae exist. Isolates harboring mph(A) were regarded as resistant.

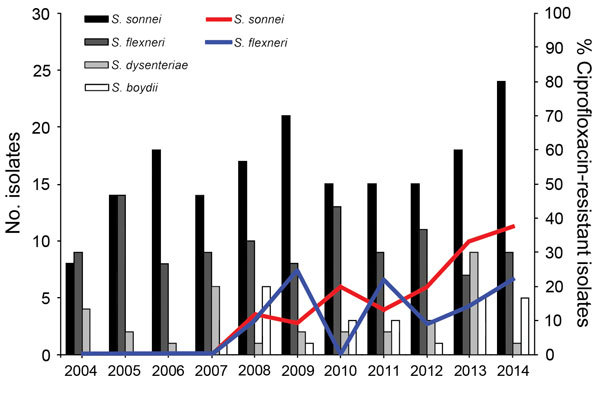

Resistance to nalidixic acid was detected in all species, but none of the S. dysenteriae and S. boydii isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin (Table 1). The time distribution and the frequency of ciprofloxacin-resistant S. sonnei isolates showed a rising tendency (Figure). A similar tendency was noted for ciprofloxacin-resistant S. flexneri isolates, which, however, revealed higher variability throughout the study period (Figure). No ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates were found before 2008. In total, 27 (15%) S. sonnei and 9 (8.4%) S. flexneri isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin.

Figure.

Shigella spp. isolated in Switzerland, 2004–2014, and percentages of ciprofloxacin-resistant S. sonnei and S. flexneri.

The qnrS1 gene was found in 13 (3.8%) of the strains: 4 S. dysenteriae, 4 S. flexneri, 4 S. boydii, and 1 S. sonnei. Other PMQR genes included qnrB19, detected in S. sonnei (n = 1), and qnrB4, detected in combination with qepA in S. sonnei (n = 1). Of the 15 PMQR-positive isolates, only 2 were resistant to nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin, illustrating the potential for development of resistance in susceptible strains (Table 2).

Table 2. Presence of PMQR determinants, amino acid changes in QRDR, ESBLs and the macrolide resistance gene mph(A) in Shigella spp. isolated in Switzerland, 2004–2014, and MICs of azithromycin against isolates containing mph(A)*.

| Year of isolation, strain | Shigella species | PMQR | QRDR |

ESBL | mph(A) | MIC, μg/mL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GyrA |

ParC |

|||||||||

| Ser83 | Asp87 | Ser80 | Ala85 | |||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||||

| 412–04 | sonnei | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 1497–04 |

flexneri

|

– |

ND |

ND |

|

ND |

ND |

ND |

+ |

24 |

| 2005 | ||||||||||

| 1826–05 | sonnei | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 263–05 | flexneri | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 693–05 | flexneri | – | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | 32 | |

| 1319–05 | sonnei | – | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | 256 | |

| 1742–05 |

flexneri

|

– |

ND |

ND |

|

ND |

ND |

ND |

+ |

12 |

| 2006 | ||||||||||

| 1920–06 | flexneri | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 1549–06 |

sonnei

|

– |

Leu |

wt |

|

wt |

wt |

ND |

– |

ND |

| 2007 | ||||||||||

| 2389–07 | sonnei | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 1374–07 |

flexneri

|

– |

Leu |

wt |

|

wt |

wt |

ND |

– |

ND |

| 2008 | ||||||||||

| 2372–08 | boydii | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 2157–08 | sonnei | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 2134–08 | boydii | – | Leu | wt | wt | Ser | ND | – | ND | |

| 822–08 | flexneri | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 959–08 |

boydii

|

qnrS1

|

ND |

ND |

|

ND |

ND |

ND |

– |

ND |

| 2009 | ||||||||||

| 09–2751 | flexneri | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 09–2192 | sonnei | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | CTX-M-14 | – | ND | |

| 09–1001 | dysenteriae | – | wt | Asn | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 09–684 | sonnei | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 006–09 | flexneri | – | Leu | Asn | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 375–09 | flexneri | qnrS1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 09–736 |

sonnei

|

– |

ND |

ND |

|

ND |

ND |

CTX-M-15 |

– |

ND |

| 2010 | ||||||||||

| 10–1982 | sonnei | – | wt | Tyr | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 10–1935 | boydii | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 10–1557 | dysenteriae | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 10–433 | sonnei | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 10–383 | flexneri | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 10–1166 | flexneri | qnrS1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 10–929 | boydii | qnrS1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 10–338 |

dysenteriae

|

qnrS1

|

ND |

ND |

|

ND |

ND |

ND |

– |

ND |

| 2011 | ||||||||||

| 11–0683 | sonnei | – | wt | Tyr | wt | wt | CTX-M-15 | – | ND | |

| 11–0616 | flexneri | – | wt | Tyr | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 11–0162 | sonnei | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 11–0029 | flexneri | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 11–1023 |

sonnei

|

– |

ND |

ND |

|

ND |

ND |

CTX-M-15 |

– |

ND |

| 2012 | ||||||||||

| 12–0580 | sonnei | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 12–0273 | flexneri | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 12–0094 | dysenteriae | – | Leu | wt | wt | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 12–0573 | dysenteriae | qnrS1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 12–0087 |

flexneri

|

qnrS1

|

ND |

ND |

|

ND |

ND |

ND |

– |

ND |

| 2013 | ||||||||||

| 13–2304 | flexneri | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 13–1996 | boydii | – | Leu | wt | wt | Ser | ND | – | ND | |

| 13–1909 | sonnei | – | wt | Tyr | wt | wt | CTX-M-14 | – | ND | |

| 13–0136 | flexneri | qnrS1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 13–1494 | dysenteriae | qnrS1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 13–1295 | sonnei | qnrS1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 13–1205 | boydii | qnrS1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 13–2356 |

boydii

|

qnrS1

|

ND |

ND |

|

ND |

ND |

ND |

– |

ND |

| 2014 | ||||||||||

| 14–2394 | sonnei | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 14–0754 | flexneri | – | Leu | Asn | Ile | wt | ND | + | 16 | |

| 14–0369 | sonnei | – | Leu | Gly | Ile | wt | ND | – | ND | |

| 14–1127 | sonnei | – | ND | ND | ND | ND | CTX-M-15 | – | ND | |

| 14–1843 | flexneri | – | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | 48 | |

| 14–1990 | sonnei | qnrB4, qepA | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | >256 | |

| 14–1929 | sonnei | qnrB19 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 14–1570 | dysenteriae | qnrS1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | – | ND | |

| 14–1495 | sonnei | – | ND | ND | ND | ND | CTX-M-3 | – | ND | |

| 14–1820 | sonnei | – | ND | ND | ND | ND | CTX-M-15 | – | ND | |

*ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; ND, not determined; PMQR, plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance; QRDR, quinolone resistance determining regions; wt, wild type; –, negative; +, positive.

Most of the 34 isolates analyzed for mutations in their QRDR carried mutations in the gyrA and parC genes (Table 2). Most frequently observed was the first-step amino acid substitution within GyrA at Ser83Leu (n = 14), which was associated with resistance to nalidixic acid. The double substitutions within GyrA at Ser83Leu/Asp87Gly (n = 11) and Ser83Leu/Asp87Asn (n = 2) occurred invariably in combination with the substitution in ParC (Ser80Ille) and occurred in ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates. In addition, some unusual genotypes were detected; strains containing only second-step mutations within GyrA were observed for Asp87Tyr (n = 4) and Asp87Asn (n = 1) and were associated with resistance to nalidixic acid. The substitution ParC(Ala85Ser) was observed in nalidixic acid–resistant S. boydii isolates with Gly(Ser80Leu) (n = 2) (Table 2).

Our data document an ongoing trend toward dominance of S. sonnei, which is reflective of a current global shift in the epidemiologic distribution of this species (10). Of the 18 patients for whom travel to India was documented, isolates from 55.6% were resistant to ciprofloxacin, a finding that supports previous reports of importation of ciprofloxacin-resistant Shigella from India to Europe and the United States (11,12) and emphasizes the need to obtain travel information from patients receiving treatment for shigellosis. Furthermore, therapeutic efficiency of fluoroquinolones may be decreased because of the presence of PMQR determinants in phenotypically susceptible strains. PMQR genes are of concern because they not only promote mutations within the QRDR, resulting in resistance to fluoroquinolones, but they may disseminate among other species of Enterobacteriaceae.

Besides ciprofloxacin, the third-generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone is recommended as an alternative for the treatment of shigellosis (1). Resistance to the broad-spectrum β-lactam ampicillin was observed in all Shigella species (Table 1); however, the ESBL phenotype (resistance to cefotaxime; Table 1) was restricted to S. sonnei and was found in 8 strains (4.5% of S. sonnei isolates). PCR analysis confirmed the presence of blaCTX-M genes in all 8 isolates: blaCTX-M-3 (n = 1), blaCTX-M-14 (n = 2), and blaCTX-M-15 (n = 5) (Table 2). The establishment of blaCTX-M–harboring Shigella as an additional reservoir of these widely disseminated resistance determinants poses a threat to the treatment of shigellosis, especially because all ESBLs detected in this study were CTX-M enzymes, which are also potent ceftriaxone hydrolyzers (13).

Screening of the 344 Shigella isolates for the presence of mph(A) revealed 7 (2%) positive strains: 2 S. sonnei and 5 S. flexneri (Table 2). Shigella species exhibiting reduced susceptibility to azithromycin are of great concern because azithromycin, in combination with colistin, has recently been found to represent a potentially invaluable option for the treatment of gram-negative rods expressing MDR, including carbapenem-resistant isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Acinetobacter baumannii (14). Hence, judicious use of this particular drug and susceptibility monitoring are warranted. Furthermore, our data show that mph(A) may be present in isolates displaying MICs as low as 12 μg/mL, highlighting the urgency with which azithromycin susceptibility breakpoints and interpretive criteria for Enterobacteriaceae are needed.

Conclusions

Treatment of shigellosis with currently recommended antimicrobial drugs is increasingly threatened by the emergence of ciprofloxacin resistance, ESBLs, or plasmid-mediated azithromycin resistance in multidrug-resistant Shigella isolates. Because azithromycin is a last-resort antimicrobial agent used to treat shigellosis, the emergence of mph(A) among Shigella spp. is cause for concern.

Acknowledgments

We thank Grethe Sägesser for her help in strain collection and technical assistance.

This project was supported by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, Berne, Switzerland.

Biography

Dr. Nüesch-Inderbinen is a research associate at the National Centre for Enteropathogenic Bacteria and Listeria and the Institute for Food Safety and Hygiene, University of Zurich, Switzerland. Her research interest is the dissemination of antimicrobial drug resistance genes among Enterobactericeae in humans and food animals.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Nüesch-Inderbinen M, Heini N, Zurfluh K, Althaus D, Hächler H, Stephan R. Shigella antimicrobial drug resistance mechanisms, 2004–2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jun [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2206.152088

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Guidelines for the control of shigellosis, including epidemics due to Shigella dysenteriae type 1. Geneva: WHO Document Production Services; 2005. p. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holt KE, Baker S, Weill FX, Holmes EC, Kitchen A, Yu J, et al. Shigella sonnei genome sequencing and phylogenetic analysis indicate recent global dissemination from Europe. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1056–9. 10.1038/ng.2369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connor TR, Barker CR, Baker KS, Weill F-X, Talukder KA, Smith AM, et al. Species-wide whole genome sequencing reveals historical global spread and recent local persistence in Shigella flexneri. Elife. 2015;4:e07335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Livio S, Strockbine NA, Panchalingam S, Tennant SM, Barry EM, Marohn ME, et al. Shigella isolates from the global enteric multicenter study inform vaccine development. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:933–41. 10.1093/cid/ciu468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu B, Cao Y, Pan S, Zhuang L, Yu R, Peng Z, et al. Comparison of the prevalence and changing resistance to nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin of Shigella between Europe-America and Asia-Africa from 1998 to 2009. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:9–17. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 21st informational supplement. Wayne (PA): The Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karczmarczyk M, Martins M, McCusker M, Mattar S, Amaral L, Leonard N, et al. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella enterica food and animal isolates from Colombia: identification of a qnrB19-mediated quinolone resistance marker in two novel serovars. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;313:10–9. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geser N, Stephan R, Hächler H. Occurrence and characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing Enterobacteriaceae in food producing animals, minced meat and raw milk. BMC Vet Res. 2012;8:21. 10.1186/1746-6148-8-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ojo KK, Ulep C, Van Kirk N, Luis H, Bernardo M, Leitao J, et al. The mef(A) gene predominates among seven macrolide resistance genes identified in gram-negative strains representing 13 genera, isolated from healthy Portuguese children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3451–6. 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3451-3456.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson CN, Duy PT, Baker S. The rising dominance of Shigella sonnei: an intercontinental shift in the etiology of bacillary dysentery. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003708. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folster JP, Pecic G, Bowen A, Rickert R, Carattoli A, Whichard JM. Decreased susceptibility to ciprofloxacin among Shigella isolates in the United States, 2006 to 2009. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1758–60. 10.1128/AAC.01463-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Lappe N, O'Connor J, Garvey P, McKeown P, Cormican M. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Shigella sonnei associated with travel to India. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:894–6. 10.3201/eid2105.141184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossolini GM, Dandrea MM, Mugnaioli C. The spread of CTX-M-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:33–41. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01867.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin L, Nonejuie P, Munguia J, Hollands A, Olson J, Dam Q, et al. Azithromycin synergizes with cationic antimicrobial peptides to exert bactericidal and therapeutic activity against highly multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial pathogens. EBioMedicine. 2015;2:690–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]