Abstract

Objectives. To examine changes in competitive foods (items sold in à la carte lines, vending machines, and school stores that “compete” with school meals) in Massachusetts middle and high schools before and after implementation of a statewide nutrition law in 2012.

Methods. We photographed n = 10 782 competitive foods and beverages in 36 Massachusetts school districts and 7 control state districts to determine availability and compliance with the law at baseline (2012), 1 year (2013), and 2 years (2014) after the policy (overall enrollment: 71 202 students). We examined availability and compliance trends over time.

Results. By 2014, 60% of competitive foods and 79% of competitive beverages were compliant. Multilevel models showed an absolute 46.2% increase for foods (95% confidence interval = 36.2, 56.3) and 46.8% increase for beverages (95% confidence interval = 39.2, 54.4) in schools’ alignment with updated standards from 2012 to 2014.

Conclusions. The law’s implementation resulted in major improvements in the availability and nutritional quality of competitive foods and beverages, but schools did not reach 100% compliance. This law closely mirrors US Department of Agriculture Smart Snacks in School standards, suggesting that complying with strict nutrition standards is feasible, and schools may experience challenges and improvements over time.

Schools have been identified as a key setting for strategies to shape healthy dietary patterns, because children often consume a significant portion of their daily calories at school, and they spend more time at school than any other environment away from home.1–3 Previous studies have shown that school practices can affect children’s dietary behavior4,5 and weight status,6–8 and nutrition policies are associated with improvements in the food environment,9–12 diet quality,12–14 and lower weight gain among children.15

In the 2014–2015 school year, schools began implementing the US Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) Smart Snacks in School nutrition standards, the first major federal update of its kind in more than 4 decades.16 Smart Snacks set standards for competitive foods and beverages: items sold in à la carte lines, vending machines, and school stores that traditionally “compete” with school meals. Generally these items are readily available, but are energy-dense and of poor nutritional quality. National estimates suggest low-nutrient, energy-dense competitive foods add more than 150 calories to children’s diets each day.17 Smart Snacks standards will be phased in over multiple years, with stricter limits on sodium and food ingredients scheduled to take effect July 2016.

Before the national changes, most state competitive foods policies were weak and limited in scope.18 Although there is mounting epidemiological evidence that stronger state-level competitive food laws are associated with healthier products,11 healthier weights,15 and increased food service revenue,19 there is little research evaluating strict state competitive food policies using direct observation methods over a multiyear period.

In 2012, Massachusetts implemented a state law20 (MGL c. 111, § 223) to establish nutrition standards for competitive foods and beverages sold or provided in public schools (105 CMR 225.000). These standards precede, but closely mirror, the final (July 2016) USDA Smart Snacks nutrition standards.21 They aim to limit the calories, portion sizes, saturated and trans fats, sugar, and sodium of snack foods and beverages offered to children, while emphasizing water without additives, skim and 1% milk, fruits and vegetables, and whole grains. Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, displays a comparison between the 2 standards.

The Massachusetts law was neither funded nor monitored for compliance by the state, so the Nutrition Opportunities to Understand Reforms Involving Student Health (NOURISH) study was created to independently assess the nutritional quality (compliance) and availability of packaged snack foods and beverages in middle and high schools before and after the law was implemented, and to examine the degree to which compliance would change over time.

METHODS

We collected data from middle schools and high schools in Massachusetts and a control state. At baseline, we initially identified all public school districts in Massachusetts and the control state with at least 1 middle and 1 high school for potential inclusion into the study. We then stratified districts into tertiles, based on the percentage of low-income students (< 20%, 20%–39%, ≥ 40%), and randomly selected districts from each tertile. We contacted food service directors (FSDs) from these school districts by e-mail in March 2012, requesting their participation for a randomly selected middle and high school in their district. We informed FSDs that participation consisted of completing a yearly survey, in-person site visit, and optional financial survey. The FSDs were provided with $50 gift cards for participating in the survey and site visit.

After 2 rounds of recruitment in 113 Massachusetts districts, 37 agreed to participate (32.7% response rate). A majority of nonconsenting districts cited time or availability constraints, as statewide student testing requirements pushed data collection to late spring.

To account for changes in school meals attributable to new national school meal standards in the 2012–2013 school year, we included a control state to examine trends across states over a parallel time period. The control state was selected because of feasibility, proximity for data collection, and demographically comparable school districts, and we used a parallel inclusion process for recruitment. The control state generally had more lenient standards for competitive foods and beverages, with no changes in its standards over the study period. Because of control state size, fewer districts were available to participate in this study. Seven of 30 contacted districts agreed to participate in the control state (23.3% response rate).

Data Collection Procedures

We collected data on competitive foods and beverages via direct observation through scheduled site visits. Two school districts had a shared cafeteria between the middle school and high school; we double-entered data for these districts to reflect availability to both middle- and high-school students. We excluded 1 consenting school district from the study because of incomplete baseline data. Research assistants collected data via lunchtime site visits in the spring of 2012 (Massachusetts: n = 36 districts; control: n = 7 districts), 2013 (Massachusetts: n = 28; control: n = 4), and 2014 (Massachusetts: n = 21; control: n = 3).

The final sample in the control state was not large enough to examine statistical differences with Massachusetts (n = 3 districts in 2014). However, control state data are presented in Tables B and C (available as supplements to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org), and the data provided availability and compliance trends over the course of the study to explore if there were strong secular trends that needed to be further accounted for in the analysis.

During site visits, research assistants took digital photographs of prepackaged competitive foods and beverages available in all vending machines, à la carte lines (each line counted as a separate location), and school stores. Every photo included the product name, size, brand, and location. Cookies baked by the school were considered a prepackaged food and were included in the analyses because they contained standardized serving sizes and complete nutrition information. We only included prepackaged foods and beverages, including cookies baked by the school, in the analyses. We excluded nonpackaged items from analysis because they were nonstandardized and their nutrition information was unavailable via direct observation methods.

The primary outcome variables were (1) the availability of prepackaged competitive foods and beverages and (2) their alignment with new state nutrition standards (percentage compliant). We calculated availability each year as the number of unique products offered per location per school. We counted locations separately for each à la carte line, vending machine, and school store. Thus, if the same product were offered in 2 vending machines and 2 à la carte lines in the cafeteria, it was counted as available 4 times. We created this variable to account for differences in product availability, where some products were only offered in 1 location, whereas others were offered almost everywhere. We then summed availability for all products in a school and calculated the average amount of items per school.

Because the state nutrition standards were not in place at baseline, compliance figures at baseline in Massachusetts and in the control state throughout the study represent alignment with the nutrition standards implemented in August 2012. We assessed compliance by comparing the nutritional information of each competitive food or beverage to the John Stalker A-List, a comprehensive database of compliant products available online through Framingham State University and the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.22 If products were on the A-List, we coded them as compliant with the law. We compared products not on the A-List with the manufacturer’s nutrition information and recoded them as compliant if they met the law. We previously documented excellent research assistant interobserver agreement of compliance.23 We calculated percentage compliant for each year as a proportion of available products (i.e., unique products per location per school) that comply with the state nutrition standards over the total number of available products.

Data Analysis

To examine whether competitive food and beverage availability and compliance changed during the study period, we calculated mean availability and percentage compliance separately each year for middle and high schools. We conducted joint significance tests to examine mean differences in availability and compliance in 2012, 2013, and 2014 by using ordinary least squares regression with robust standard errors. We conducted the posthoc t test to examine mean differences in availability and compliance from 2013 to 2014.

We conducted statistical analyses with Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). We used multilevel regression models with robust standard errors to examine yearly school-level compliance. All models account for observations nested within schools, and each middle school and high school being nested within a school district. Approximately 21% of the variation in food compliance and 14% of the variation in beverage compliance were attributable to differences between school districts (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC]foodcompliance = 0.21; ICCbeveragecompliance = 0.14).

We calculated compliance by school and then modeled it separately for foods and beverages, with demographic variables included as covariates. We modeled year as an indicator variable to show the effect of schools’ compliance after each year of implementation compared with baseline. We used the school-level percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch (i.e., low-income students) as a proxy for socioeconomic status. We divided income into low, medium, and high tertiles, and we compared middle-income and low-income schools with high-income schools (referent category). We measured school racial/ethnic composition in tertiles: low, medium, and high percentage of racial/ethnic minority students, with which we compared medium- and high-percentage minority schools with low-percentage minority schools (referent category). We measured product venue by comparing vending machine and school store to à la carte (referent category). We modeled school level to understand differences in compliance in high schools compared with middle schools. We used posthoc tests to check for normality and used robust standard errors to correct for heteroskedasticity.

RESULTS

At baseline, the NOURISH study included 36 districts in Massachusetts, with 1 middle school and 1 high school per district (Table 1). Participating schools were demographically similar to nonconsenting schools, with no statistically significant differences between groups in school size or the percentage of racial/ethnic minority students. There were also no differences in the proportion of low-income students between middle or high schools in consenting versus nonconsenting districts. Massachusetts schools with both years of follow-up data were demographically similar to schools with incomplete follow-up, with no statistically significant differences in school size, percentage of racial/ethnic minority students, percentage of low-income students, or number of competitive food and beverage locations. Compared with control state schools in our sample (Table B), participating Massachusetts schools had a higher percentage of non-White students at baseline, whereas school size and percentage of low-income students were similar across states.

TABLE 1—

Baseline Sample Characteristics of Massachusetts Schools by School Type: Spring 2012

| Characteristics | Middle Schools (n = 36), Mean (SD) | High Schools (n = 36), Mean (SD) |

| School size, enrollment | 639 (242) | 1041 (490) |

| Percentage White students | 81.2 (16.1) | 80.8 (17.0) |

| Percentage low-income (FRPL) students | 29.3 (18.0) | 24.4 (14.5) |

| Number of à la cartea lines | 4.7 (2.5) | 6.5 (3.8) |

| Number of vending machines | 1.3 (1.8) | 4.5 (3.3) |

| Number of school stores | 0.03 (0.2) | 0.08 (0.3) |

| Total CF&Bb locations per school | 5.9 (3.1) | 11.1 (4.9) |

| Percentage of CF&Bs inside cafeteriac | 92.8 (0.7) | 84.0 (0.6) |

Note. CF&B = competitive food and beverage; FRPL = free and reduced-price lunch. Numbers of CF&B locations may not add up to total numbers because of rounding.

Counts each à la carte line separately; includes snack bars inside the cafeteria.

Total CF&B locations includes à la carte lines, vending machines, and school stores.

CF&Bs located inside the cafeteria as a percentage of all CF&Bs located throughout a school.

Competitive foods and beverages were widely available at baseline in different locations throughout Massachusetts middle schools and high schools (Table 1). In spring 2012 (baseline), middle and high schools had, on average, 5.9 and 11.1 different locations, respectively, for purchasing snack foods and beverages, including à la carte lines, vending machines, and school stores.

Changes in Food Availability and Compliance

Compared with baseline, competitive food availability dropped in middle schools in 2013 (P < .05), while competitive food availability remained steady in high schools over the study period (Table 2). In 2014, high schools offered an average of 39 prepackaged competitive food products for sale, and middle schools offered an average of 18. Chips were the most widely available competitive food item in 2014. Compared with baseline, high schools offered fewer cookies and brownies and ice cream products, popsicles, or frozen treats.

TABLE 2—

Compliance and Availability of Snack Foods and Beverages by Year and School Level Before and After Massachusetts Competitive Food Law: 2012–2014

| Middle Schools |

High Schools |

|||||

| Variables | Baselinea (2012) | 1 Year After (2013) | 2 Years After (2014) | Baselinea (2012) | 1 Year After (2013) | 2 Years After (2014) |

| All foodsb | ||||||

| % Compliant | 18.6 | 68.1c | 54.5d,e | 15.3 | 55.1c | 62.2e,f |

| Availability, no. | 20.0 | 12.9g | 18.1 | 51.9 | 42.8 | 39.0 |

| Cereals, cereal or granola bars, breakfast Items | ||||||

| % Compliant | 34.0 | 68.9c | 59.6e | 22.6 | 63.4c | 69.9e |

| Availability, no. | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 10.9 | 10.3 | 8.2 |

| Chips | ||||||

| % Compliant | 30.8 | 82.2c | 67.1d,e | 25.9 | 62.3c | 67.5e |

| Availability, no. | 5.9 | 4.2 | 7.4f | 14.8 | 14.6 | 15.0 |

| Other sweet snacksh | ||||||

| % Compliant | 28.3 | 55.6c | 80.0e,f | 8.8 | 48.0c | 64.3e,f |

| Availability, no. | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 2.7 |

| Nuts and other salty snacksj | ||||||

| % Compliant | 25.0 | 64.3 | 18.2d | 16.7 | 39.5c | 34.6 |

| Availability, no. | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| Crackers, popcorn, pretzels, snack mix | ||||||

| % Compliant | 10.6 | 52.9c | 45.5e | 7.8 | 39.3c | 55.6e,f |

| Availability, no. | 3.9 | 1.8g | 2.6 | 8.9 | 7.2 | 6.0 |

| Ice cream, popsicles, and frozen treats | ||||||

| % Compliant | 2.6 | 75.0c | 21.7d,e | 3.2 | 70.3c | 43.1d,e |

| Availability, no. | 4.2 | 0.7g | 2.9 | 6.0 | 1.3g | 2.4i |

| Cookies and brownies | ||||||

| % Compliant | 0.0 | 78.9c | 75.0e | 3.5 | 59.4c | 79.2e,f |

| Availability, no. | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 4.0 | 2.3g | 2.3i |

| Yogurt and cheesek | ||||||

| % Compliant | 0.0 | 18.2 | 14.3 | 0.0 | 9.7 | 4.2 |

| Availability, no. | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| All beverages | ||||||

| % compliant | 35.4 | 74.0c | 83.1e,f | 26.0 | 67.6c | 76.6e,f |

| Availability, no. | 14.9 | 9.5g | 11.3 | 47.5 | 22.4g | 23.4i |

| Bottled water (unflavored) | ||||||

| % Compliant | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Availability, no. | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.6 |

| Milkl | ||||||

| % Compliant | 58.2 | 100c | 100e | 65.6 | 96.2c | 96.1e |

| Availability, no. | 3.7 | 2.9 | 5.3e,f | 5.3 | 3.8 | 7.3f |

| Flavored waterm | ||||||

| % Compliant | 35.5 | 94.4c | 54.3d | 33.3 | 74.7c | 78.1e |

| Availability, no. | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 10.3 | 7.8 | 6.1 |

| 100% juice | ||||||

| % Compliant | 11.8 | 36.2c | 61.4e,f | 9.7 | 39.2c | 55.0e |

| Availability, no. | 4.0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 7.8 | 2.8g | 2.9i |

| Othern | ||||||

| % Compliant | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.8 | 0 |

| Availability, no. | 2.2 | 0.8 | 0.2i | 10.8 | 1.9g | 1.1i |

| Sports drinks | ||||||

| % Compliant | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Availability, no. | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.1i | 8.7 | 1.6g | 1.4i |

Note. % Compliant = number of unique products available per location per school that meet the new nutrition standards/total number of unique products available per location per school. Compliance only calculated among schools that offered any packaged products in a given year. Availability = average number of items available per school, calculated as the sum of unique items available per location per school (e.g., if the same product is available in 4 vending machines, 4 à la carte lines, and a school store, count as available 9 times). Availability is averaged across all participating schools per year (even if schools offer 0 packaged products that year). Product categories are ranked in order by baseline percentage compliance. n = 36 school districts in 2012, 28 school districts in 2013, and 21 school districts in 2014.

The new Massachusetts policy was not in place at baseline, so compliance figures at baseline represent compliance if the new law had already been in place.

Nonpackaged foods were excluded from this analysis.

Higher in 2013 compared with 2012 (statistically significant at P < .05).

Lower in 2014 compared with 2013 (statistically significant at P < .05).

Higher in 2014 compared with 2012 (statistically significant at P < .05).

Higher in 2014 compared with 2013 (statistically significant at P < .05).

Lower in 2013 compared with 2012 (statistically significant at P < .05).

Other sweet snacks includes items such as animal and graham crackers, candy, and dried fruit.

Lower in 2014 compared with 2012 (statistically significant at P < .05).

Other salty snacks includes items such trail mix, bagels, and beef jerky.

Yogurt and cheese includes yogurt, string cheese, and pudding products.

Includes milk and milk substitutes such as lactose-free milk and soy milk.

Flavored water is any flavored beverage containing “water” or “H2O” in its title.

Other includes fruit drinks, teas, diet sodas, other sugary drinks.

Both middle schools and high schools increased snack compliance with the competitive food law 2 years after implementation compared with baseline. High schools increased compliance in 2013 (55.1%; P < .001) compared with baseline (15.3%), and further increased compliance in 2014 (62.2%; P < .001). Middle schools increased compliance in 2013 (68.1%; P < .001) compared with baseline (18.6%), but saw a decline in 2014 compliance (54.5%; P < .001) compared with 2013. In both middle and high schools, compliance was highest for cookies and brownies, “other” sweet snacks such as graham crackers and dried fruit, and chips. Categories with the highest percentages of noncompliant items include nuts and other salty snacks (including trail mix), yogurt and cheese products, and ice cream, popsicles, and frozen treats.

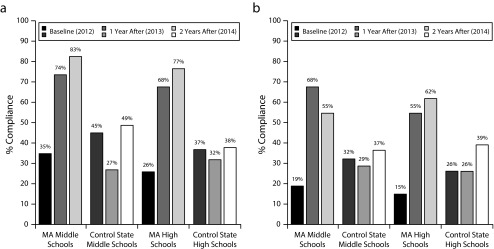

In the control state, competitive food availability remained stable in middle schools and high schools throughout the study (Table C), and alignment with the Massachusetts nutrition standards remained low (Figure 1 and Table C).

FIGURE 1—

Changes in Compliance of (a) Beverages and (b) Foods: Massachusetts and Control State Middle Schools and High Schools, 2012–2014

Note. Compliance percentage = number of products available that meet the new nutrition standards / total number of products available. Compliance figures at baseline and in the control state represent alignment with the law. Massachusetts district n (1 middle and 1 high school per district) = 36 in 2012, 28 in 2013, 21 in 2014. Control district n (1 middle and 1 high school per district) = 7 in 2012, 4 in 2013, 3 in 2014.

Changes in Beverage Availability and Compliance

Compared with baseline, competitive beverage availability dropped in middle schools in 2013 (P < .05; Table 2). In high schools, competitive beverage availability dropped in 2013 and remained lower in 2014 compared with baseline (P < .05). This was largely driven by the removal of sports drinks and “other” drinks, including fruit drinks, teas, diet sodas, and sugary drinks. In 2014, middle and high schools offered an average of 11 and 23 beverage items, respectively, compared with 15 and 48 products in 2012. Milk (flavored and unflavored) was the most widely available competitive beverage item in 2014. Compared with baseline, middle schools offered more milk and fewer sports drinks and “other” drinks, whereas high schools offered fewer 100% juice products, sports drinks, and “other” drinks.

For beverages, both middle schools and high schools increased alignment with the law in 2013, and then showed further increases in 2014. High schools increased compliance in 2013 (67.6%; P < .001) compared with baseline (26.0%), and further increased compliance in 2014 (76.6%; P < .001). Middle schools increased compliance in 2013 (74.0%; P < .001) compared with baseline (35.4%), and further increased compliance in 2014 (83.1%; P < .001). Among all beverages, compliance for 100% juice increased in middle schools from 2013 to 2014; almost all milk was already compliant in middle and high schools by 2013; and unflavored bottled waters were compliant at all time points. No sports drinks and “other” drinks were ever compliant with the law. A majority of flavored waters—any flavored beverages containing “water” or “H2O” in the title—were compliant with the law in 2014 (54.3% in middle and 78.1% in high schools).

In the control state, competitive beverage availability remained stable in middle schools and high schools during the study period (Table C), and alignment with the Massachusetts nutrition standards remained below 50% (Figure 1 and Table C).

Compared with the average percentage of products per school that would have met updated state nutrition standards before the policy (2012), unadjusted models using multilevel regression analysis (model 1; Table 3) for foods showed an absolute 46.2% increase (95% confidence interval [CI] = 36.2, 56.3) and for beverages a 46.8% increase (95% CI = 39.2, 54.4) in schools’ alignment with state nutrition standards after 2 years of implementing the policy (2014). When we added product venue and adjusted for school level, school socioeconomic status, and school race/ethnicity (model 2; Table 3), the results remained significant. After 2 years, competitive beverages in vending machines had a 11.6% (95% CI = –2.8, –20.3) lower predicted compliance, on average, compared with beverages in à la carte locations, after we controlled for other variables. High schools had a 9.6% (95% CI = –3.9, –15.4) lower predicted beverage compliance, on average, compared with middle schools (model 2). School level was not a statistically significant predictor of compliance for competitive foods (95% CI = –10.2%, 2.0%). Adjusting for school socioeconomic status and school size had nonsignificant effects on food and beverage compliance, and adjusting for school race/ethnicity showed a small effect only among medium-percentage minority high schools compared with low-percentage minority high schools (95% CI = 0.4%, 25.7%).

TABLE 3—

Multilevel Model of Snack Food and Beverage School Compliance in Massachusetts Middle and High Schools Over Time: 2012–2014

| Variable | b (95% CI) | P |

| Model 1a—overall compliance | ||

| Food compliance (n = 159)c | ||

| Year 1 after law (2013) | 0.454 (0.364, 0.544) | < .001 |

| Year 2 after law (2014) | 0.462 (0.362, 0.563) | < .001 |

| School district random intercept | 0.142 (0.110, 0.184) | |

| Beverage compliance (n = 168)d | ||

| Year 1 after law (2013) | 0.412 (0.298, 0.527) | < .001 |

| Year 2 after law (2014) | 0.468 (0.392, 0.544) | < .001 |

| School district random intercept | 0.143 (0.094, 0.217) | |

| Model 2b—compliance by product location | ||

| Food compliance (n = 230)e | ||

| Year 1 after law (2013) | 0.423 (0.335, 0.511) | < .001 |

| Year 2 after law (2014) | 0.444 (0.350, 0.538) | < .001 |

| High-school level | −0.041 (−0.102, 0.020) | .19 |

| Vending | −0.034 (−0.108, 0.039) | .36 |

| School store | −0.140 (−0.260, –0.021) | .02 |

| Medium-income school | −0.076 (−0.179, 0.028) | .15 |

| Low-income school | −0.110 (−0.247, 0.027) | .12 |

| Medium-percentage racial/ethnic minority school | −0.070 (−0.179, 0.038) | .21 |

| High-percentage racial/ethnic minority school | 0.008 (−0.120, 0.137) | .90 |

| School district random intercept | 0.113 (0.083, 0.153) | |

| Beverage compliance (n = 290)f | ||

| Year 1 after law (2013) | 0.437 (0.332, 0.542) | < .001 |

| Year 2 after law (2014) | 0.480 (0.405, 0.556) | < .001 |

| High-school level | −0.096 (−0.154, –0.039) | .001 |

| Vending | −0.116 (−0.203, –0.028) | .01 |

| School store | −0.070 (−0.282, –0.141) | .52 |

| Medium-income school | −0.007 (−0.112, 0.098) | .89 |

| Low-income school | −0.024 (−0.143, 0.094) | .69 |

| Medium-percentage racial/ethnic minority school | 0.131 (0.004, 0.257) | .04 |

| High-percentage racial/ethnic minority school | 0.136 (−0.025, 0.297) | .1 |

| School district random intercept | 0.137 (0.092, 0.205) | |

Note. CI = confidence interval. Low-income school, low-percentage racial/ethnic minority school, and à la carte product location are the referent categories; robust standard errors used in all models.

Model 1 is unadjusted. Model 1 regressions were conducted after calculating mean percentage compliance by school in 2012, 2013, and 2014.

Model 2 adjusts for school level, socioeconomic status, and the percentage of racial/ethnic minority students. Model 2 regressions were conducted after calculating mean percentage compliance by product venue (à la carte, vending machines, or school stores) per school in 2012, 2013, and 2014.

Includes school compliance of any school that offered competitive foods in 2012, 2013, or 2014.

Includes school compliance of any school that offered competitive beverages in 2012, 2013, or 2014.

Models the school compliance separately among foods in à la carte lines, vending, and school stores.

Models the school compliance separately among beverages in à la carte lines, vending, and school stores.

DISCUSSION

The NOURISH study results support previous findings demonstrating that state legislation can be effective at improving the competitive food environment in schools.10,15,24,25 Despite these significant gains, however, schools did not reach 100% compliance as required by law. Compliance increased unevenly across school level and between different categories over the 2-year follow-up period. Schools more than doubled compliance overall during this time, and by 2014, 60% of competitive foods and 79% of competitive beverages in NOURISH schools were compliant with the new policy.

Both compliant and noncompliant competitive products were still widely available 2 years after the law was implemented. The drop in middle-school snack food compliance from 2013 to 2014 may be partly explained by lack of clarity for FSDs over which items met the law. Although it was relatively clear-cut whether items in categories such as milk and unflavored water met the law, other categories were less clear. For example, noncompliant chips largely drove declining compliance in middle schools from 2013 to 2014. A majority of these were name-brand items, and they either exceeded the sodium limits or contained more than 35% of total calories from fat, despite frequently being reformulated versions or smaller portion sizes of higher-fat, -calorie, or -sodium products. Viewing the front of the package alone would not convey enough information to determine the product’s compliance. Foodservice would need to use guides such as the A-List, as many similarly labeled and packaged products differed in compliance.

Although their availability was limited, nuts and other salty snacks, yogurt and cheese products, and ice cream, popsicles, and frozen treats were largely noncompliant. Most noncompliant nuts and other salty snacks exceeded the sodium or calorie limits (e.g., several were chocolate trail mix varieties), most noncompliant yogurt items exceeded sugar limits, most cheese items exceeded saturated fat or sodium limits, and most noncompliant ice cream products exceeded either the sugar or calorie limits.

The availability of juice and other flavored or sugary beverages that did not meet the law proved to be major challenges as well. A majority of noncompliant 100% juices exceeded the law’s 4-ounce limit. Although the availability of sports drinks and “other” drinks declined, none ever met the law. A majority of these items contained artificial sweeteners. Categorically, only water, juice, and milk were allowed. A majority of available flavored waters—items containing “water” or “H2O” in their titles—were not compliant with the law because they contained artificial sweeteners, which may not be obvious to FSDs because of the beverages’ marketing and nutritional profile (e.g., many were zero-calorie beverages).

After this study was completed, in December 2014, state policymakers made minor modifications to incorporate Smart Snacks standards. These updates made additional exemptions for nuts, nut butters, and cheese items; allowed nonfat flavored milk with no more than 22 grams of sugar; and relaxed the sugar requirements (≤ 35% of weight from total sugars) and portion size limits for juice (8 ounces). These changes were unrelated to the NOURISH study and would likely result in minor increases in compliance among some food and beverage subgroups, though not among chips, sports drinks, or “other” beverages.

This study had several limitations. Although control state schools showed relatively stable availability and compliance, the sample size was too small to make statistical comparisons to Massachusetts. Our response rate and loss to follow-up are also limitations, and primarily occurred because of lack of time and staff turnover. However, nonconsenting districts were not statistically different than schools from districts in our sample, and districts with incomplete data at either of the follow-up periods had similar demographic characteristics and product availability as districts with full follow-up data. These results may not be generalizable to elementary schools, and Massachusetts schools may not be generalizable to other states with lower baseline compliance rates and different demographic characteristics.

We excluded nonpackaged competitive food products from analysis because they were nonstandardized, which prevented us from capturing changes in entrée à la carte items, fresh fruits, and vegetables. Future research should aim to capture changes in these items. Not all competitive foods served in Massachusetts (e.g., after-school bake sales) fall under the scope of the law, nor could they be observed with the data collection methods. As national standards for school meals were implemented during the study period, they may have affected competitive food compliance, though this was unlikely, as availability and compliance in the control state remained steady.

This analysis was limited to changes in the competitive food environment and did not capture changes in food sales or children’s consumption. Future research should assess the impact, if any, that the law had on school finances, as well as on children’s consumption during and outside of school.

Overall, we found that a statewide competitive food and beverage law closely mirroring national Smart Snacks in School nutrition standards resulted in some healthy changes to the school food environment in Massachusetts middle and high schools. However, on average, schools did not achieve perfect compliance. In particular, compliance could be improved for beverages by removing artificially flavored or sweetened drinks, and by serving smaller portion sizes of juice. Compliance for packaged snacks could be improved by offering items with fewer calories, less sodium, and less sugar. Finding healthier packaged products that clearly meet new standards is an ongoing challenge for many schools, so working with groups that provide technical assistance such as the Stalker Institute, USDA, and the Alliance for a Healthier Generation may help. Manufacturer labels certifying that foods meet updated nutrition standards may also help FSDs more easily identify compliant packaged products.

Because this law was neither funded nor monitored for compliance by the state, these results may underestimate schools’ potential adherence to Smart Snacks in School nutrition standards. Nationally, schools are provided with compliance tools and additional technical assistance by USDA to help meet new standards, as well as a longer phased-in implementation period.26 These data suggest that implementing policies with strict nutrition criteria, such as Massachusetts 105 CMR 225.000 and Smart Snacks in School, are feasible, and schools may experience both challenges and major improvements in compliance with new standards over time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for the Nutrition Opportunities to Understand Reforms Involving Student Health study was provided by Harvard Catalyst and the Healthy Eating Research Program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. J. F. W. Cohen is supported by the Nutrition Epidemiology of Cancer Education and Career Developing Program (grant R25 CA 098566). M. Gorski is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant T32HS000055).

The authors thank the participating school districts and research assistants who made this study possible, as well as Tom Land, Kathleen Millett, Christina Nordstrom, Laura York, and Julianna Valcour, who were at the Massachusetts departments of Public Health and Elementary and Secondary Education. They also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers whose feedback greatly improved this article.

Note. The funding agencies had no involvement in the study design, interpretation of data, article preparation, or the decision to submit the article for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Story M, Nanney MS, Schwartz MB. Schools and obesity prevention: creating school environments and policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):71–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan LK, Sobush K, Keener D et al. Recommended community strategies and measurements to prevent obesity in the United States. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-7):1–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French SA, Story M, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. An environmental intervention to promote lower-fat food choices in secondary schools: outcomes of the TACOS study. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(9):1507–1512. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry CL, Bishop DB, Taylor GL et al. A randomized school trial of environmental strategies to encourage fruit and vegetable consumption among children. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(1):65–76. doi: 10.1177/1090198103255530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Story M. Schoolwide food practices are associated with body mass index in middle school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1111–1114. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox MK, Dodd AH, Wilson A, Gleason MP. Association between school food environment and practices and body mass index of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2 suppl):S108–S117. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennessy E, Oh A, Agurs-Collins T et al. State-level school competitive food and beverage laws are associated with children’s weight status. J School Health. 2014;84(9):609–616. doi: 10.1111/josh.12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whatley Blum JE, Beaudoin CM, O’Brien LM, Polacsek M, Harris DE, O’Rourke KA. Impact of Maine’s statewide nutrition policy on high school food environments. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8(1):A19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woodward-Lopez G, Gosliner W, Samuels SE, Craypo L, Kao J, Crawford PB. Lessons learned from evaluations of California’s statewide school nutrition standards. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(11):2137–2145. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.193490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chriqui JF, Turner L, Taber DR, Chaloupka F. Association between district and state policies and US public elementary school competitive food and beverage environments. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(8):714–722. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chriqui JF, Picket M, Story M. Influence of school competitive food and beverage policies on obesity, consumption, and availability: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(3):279–286. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briefel RR, Crepinsek MK, Cabili C, Wilson A, Gleason PM. School food environments and practices affect dietary behaviors of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2 suppl):S91–S107. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nanney MS, MacLehose R, Kubik MY, Davey CS, Coombes B, Nelson TF. Recommended school policies are associated with student sugary drink and fruit and vegetable intake. Prev Med. 2014;62:179–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taber DR, Chriqui JF, Perna FM, Powell LM, Chaloupka FJ. Weight status among adolescents in states that govern competitive food nutrition content. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):437–444. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.US Department of Agriculture. Smart Snacks in School. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/allfoods_flyer.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2015.

- 17.Fox MK, Gordon A, Nogales R, Wilson A. Availability and consumption of competitive foods in US public schools. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2) suppl:S57–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. Competitive foods and beverages in US schools: a state policy analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kids’ Safe and Healthful Foods Project and Health Impact Project. Health Impact Assessment: National Nutrition Standards for Snack and a la Carte Foods and Beverages. 2012. Available at: http://www.pewtrusts.org/∼/media/Assets/2012/06/SnackFoodsHealthImpactAssessment.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2015.

- 20.Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Massachusetts General Law c 111, § 223 (adopted July 2010) Available at: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleXVI/Chapter111/Section223. Accessed March 15, 2016.

- 21.US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. 7 CFR Parts 210 and 220: National School Lunch and School Breakfast Program: Nutrition Standards for All Foods Sold in School as Required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010; Interim Final Rule. Fed Reg. 78(125). June 28, 2013. Available at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-06-28/pdf/2013-15249.pdf. Accessed March 15, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. The John C. Stalker Institute of Food and Nutrition at Framingham State University. JSI A-List. Available at: http://www.johnstalkerinstitute.org/alist. Accessed June 8, 2015.

- 23.Hoffman JA, Rosenfeld L, Schmidt N et al. Implementation of competitive food and beverage standards in a sample of Massachusetts schools: the NOURISH study (Nutrition Opportunities to Understand Reforms Involving Student Health) J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(8):1299–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.04.019. e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips MM, Raczynski JM, West DS et al. Changes in school environments with implementation of Arkansas Act 1220 of 2003. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(suppl 1):S54–S61. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long MW, Henderson KE, Schwartz MB. Evaluating the impact of a Connecticut program to reduce availability of unhealthy competitive food in schools. J Sch Health. 2010;80(10):478–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Food and Nutrition Service, US Department of Agriculture. “Smart Snacks in School” Nutrition Standards Interim Final Rule Questions and Answers. Available at: http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/allfoods_QandA.pdf. Accessed July 13, 2015.