Abstract

Latina/o Americans are at high risk for sexually transmitted infections and adolescent pregnancies. Needed urgently are innovative health promotion approaches that are engaging and culturally sensitive. East Los High is a transmedia edutainment program aimed at young Latina/o Americans. It embeds educational messages in entertainment narratives across digital platforms to promote sexual and reproductive health. We employed online analytics tracking (2013–2014), an online viewer survey (2013), and a laboratory experiment (El Paso, TX, 2014) for season 1 program evaluation. We found that East Los High had a wide audience reach, strong viewer engagement, and a positive cognitive, emotional, and social impact on sexual and reproductive health communication and education. Culturally sensitive transmedia edutainment programs are a promising health promotion strategy for minority populations and warrant further investigation.

Latina/os are the largest and fastest-growing racial/ethnic minority in the United States.1 Per US Census Bureau projections, 25% of American adolescents will be Latina/o by 2020.2 These changing demographics have significant implications for public health. Although risky sexual behaviors among American youths have declined since 1990, Latina/o youths have higher rates of sexually transmitted infections and unintended pregnancies than do other racial/ethnic groups.3,4 One in 3 Latina adolescents become pregnant before age 20 years—1.5 times the national average.2 This is not surprising considering that only about half of sexually active Latina/o adolescents reported using a condom during their last sexual intercourse, and only 1 in 7 used birth control pills or other contraceptives.5 Latina adolescent mothers bear the greatest burden of higher order and rapid repeat pregnancies.6 Poverty, school dropout, and limited health care access also affect young Latina/o Americans, exacerbating disparities in sexual and reproductive health.7

Despite the high risks, there is a dearth of effective health interventions tailored to Latina/o youths.4 Current interventions are targeted predominantly at African Americans and tied largely to school-based programs, and their effectiveness is limited.3 Innovative and culturally sensitive health promotion approaches for Latina/o youths are urgently needed.4,8 East Los High is such a sexual and reproductive health intervention. Incorporating an online drama series and several narrative extensions across multiple digital platforms, East Los High followed the principles of entertainment–education and transmedia storytelling to reach, engage, and influence young Latina/o Americans regarding adolescent pregnancy prevention and better sexual and reproductive health.

We set up the context of this project after a review of transmedia edutainment, including its theoretical foundations in narrative engagement and persuasion. We analyzed the strategic design elements of East Los High’s season 1 programming and we have reported the research methods used for program evaluation along with a discussion about the key findings and implications for designing sexual and reproductive health interventions for Latina/o youths.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Although storytelling has served as a vehicle for recreation, instruction, and transformation for thousands of years, only in recent decades has it been used in entertainment media for health promotion—a field of scholarship and practice known as “entertainment–education” or “edutainment.”9,10 Edutainment programs increasingly supplement and complement traditional public health interventions. In the early days of edutainment, radio and television dramatic serials were designed and broadcast in Latin America, Asia, and Africa to entertain and educate on a variety of topics.9,10 Using fictional melodramatic narratives, they educated audiences about contraceptive methods and modeled positive sexual attitudes and behaviors; thus, they have improved the sexual and reproductive health of millions in developing countries.9,10

However, edutainment programs in North America and Europe face stiff competition in their media-saturated environments.11 To earn audience ratings, sexual content on commercial channels is usually highly explicit, often inaccurate, and commonly devoid of discussion about risks and associated consequences.12 To overcome these challenges, several institutions (e.g., Hollywood Health & Society in the United States) have given creative writers and producers the knowhow to accurately portray critical health information in the popular media.10

Transmedia storytelling is an innovative media programming trend.10 Instead of telling the story in a single medium, narrative elements are creatively coordinated across different media platforms (hence “transmedia”) to build a story world, engage a broader spectrum of audience, and provide them an enriching experience beyond pure entertainment.13,14 Inspired by the commercial success of transmedia in entertainment franchises such as Star Wars, some transmedia producers are now collaborating with nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and public health professionals to create prosocial programs. For young audience members, who are savvy entertainment consumers and can easily navigate multiple digital platforms, transmedia edutainment holds promise as a health promotion and education interventional tool.10

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

Edutainment programs are grounded in theories of narrative persuasion that explain the factors and processes that facilitate changes in audience members’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. By contrast to political campaigns, embedding educational messages in entertainment narratives creates a genre of implicit persuasion.15 Certain elements of narrative-based entertainment help suspend audience disbelief and reduce resistance to counterarguments.16

Many edutainment programs use social cognitive theory, an agentic framework of psychosocial change with a dual path of influence: direct exposure to media models and indirect social learning through interpersonal discussions.17 The transportation–imagery model posits that narratives can be highly immersive, prompting the audience to pay attention and generate mental imagery of a prospective potentiality and transporting the audience into a world of a different time and space.18 In addition, narratives resonate particularly well with audience members when they perceive the stories to be realistic and can identify with the characters on the basis of existing similarities or desirable attributes.16,19,20 Furthermore, theories of culturecentric health promotion emphasize that narratives built with familiar cultural markers are especially effective when targeting minority populations.8,21

Recent meta-analyses have demonstrated the advantages of using narratives in health interventions. Narratives have a sizably significant impact on combined changes in attitudes, intention, and behavior, even though they have a relatively small effect size in individual outcomes. Narratives are powerful interventional tools for eliciting affective audience response, and evidence suggests that those delivered through audio and video are more effective than are those delivered through print.22,23 Moreover, empirical studies show that narrative-based interventions effectively reduce health disparities for racial/ethnic minority groups.24 Narrative persuasion theories guided East Los High program development in terms of character building and content production and its program evaluation in terms of choosing key measures and hypotheses.

EAST LOS HIGH PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT

At least 3 aspects of East Los High set it apart from other popular series, such as Degrassi and 16 and Pregnant, that discuss sexual and reproductive health issues among youths: cultural sensitivity, transmedia edutainment programing, and collaborative multilateral partnerships.

East Los High is a culturally sensitive intervention: it is the first English-language edutainment program in the United States made for Latina/os that uses exclusively Latina/o creators, writers, and cast members. East Los High is set in a fictional high school in East Los Angeles, a predominantly Latina/o area in Los Angeles County with high rates of poverty, low educational attainment, and low household income. It was designed to subvert the stereotypes of Latina/o characters as gardeners, maids, and gang members.25

Among the main characters are Jacob, a graduating senior and popular football player; Jessie, an intelligent, attractive junior who secretly admires Jacob and is new to the school’s Bomb Squad dance team; Maya, Jessie’s cousin, a troubled runaway who takes refuge in Jessie’s home and quickly becomes Jacob’s heartthrob; Ceci, a lead dancer in the Bomb Squad, who is sexually active, becomes pregnant, and finds her life turned upside-down; and Vanessa, captain of the Bomb Squad, who trades sex for favors and discovers she is HIV positive. The plot simmers when Jessie, a member of the “virgin club,” is forced to disclose her secret as things get hot between her and Jacob. Maya, scarred by a past rape, rebuilds her life through work in a restaurant owned by Jacob’s father. Ceci, deserted by her boyfriend when she becomes pregnant, considers abortion but decides to keep her child. Vanessa, jealous and vengeful, orchestrates Jessie’s seduction and repents as she copes with HIV.

Furthermore, East Los High is the first transmedia program purposefully designed as edutainment to tackle sexual and reproductive health issues. Some commercial franchises created such transmedia experiences for their audience members. A notable example was The Matrix, in which the overarching storyline was conveyed through the movie trilogy and a series of animations, comic books, and a video game tie-ins.14 The interwoven transmedia tapestry made a richer story world, deepening the audience’s relationship with the characters, plotlines, and issues.

Similarly, East Los High offered multiple entry points for Latina/o youths, who are avid consumers of dramas and digital entertainment, to engage in the narrative through their preferred platform.14,26,27 East Los High’s transmedia approach was highly strategic because Latinas/os are 40% more likely than is the general population to watch television and videos online or on a smartphone and 3 times more likely to check, via social media, which programs their friends are watching.28 East Los High capitalized on the digital usage patterns of Latina/o youths to engage them about sexual and reproductive health issues.

East Los High, season 1 was a 24-episode original drama series on Hulu, the popular Web-streaming site. At the end of each episode, viewers were nudged to the East Los High Web site (eastloshigh.com), where they could access 9 transmedia narrative extensions (Figure 1). Viewers could watch, for instance, an extended scene in which a health clinic counselor talks compassionately with Maya about correct condom use. They could also access Ceci’s vlogs. After being abandoned by her boyfriend, the pregnant Ceci is taken in by a women’s shelter. There she learns about services available for pregnant adolescents. These include the options of giving birth and raising the child, giving up the child for adoption, and terminating the pregnancy. Viewers could access 6 of Ceci’s vlogs, which were linked to different episodes as the major storyline unfolded in the online drama. In the vlogs, the audience sees Ceci talking about how she feels about being a pregnant adolescent, the physiological changes in her body, and the socioeconomic and cultural challenges she faces. From there, viewers could visit the East Los High resources page, use widgets to find local health clinics, and click on external links for additional information. These transmedia extensions of East Los High were promoted on popular social networking sites (i.e., Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, and Instagram).

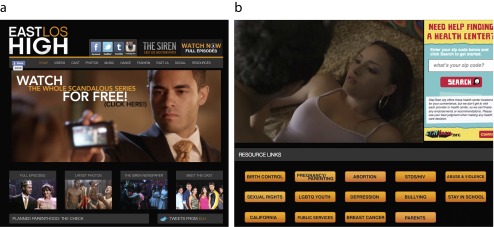

FIGURE 1—

East Los High’s Web Site: Season 1, 2013

Note. East Los High’s transmedia extensions included extended scenes (part a), the Siren news article, Ask Paulie, Ceci’s vlogs, Maya’s recipes, dance tutorials, La Voz with Xavi, comic strips, and StayTeen.org public service announcements. East Los High also has a comprehensive resources page with embedded health service widgets (part b).

Finally, East Los High fostered an extensive web of collaborative multilateral partnerships. More than 3 years in development, East Los High was the brainchild of executive producer Katie Elmore Mota. Mota forged a unique collaboration between Wise Entertainment (a Hollywood-based production company), Population Media Center (a Vermont-based nonprofit organization that excels in edutainment), and various national, regional, and local NGOs. These NGOs included the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, Advocates for Youth, the National Latina Initiative, the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health, California Latinas for Reproductive Justice, and Legacy LA.

Focus groups with Latina/o adolescents, conducted through NGO partners, ensured realistic character portrayals and authentic dialogues.29 The result is that since 2013, East Los High has been consistently rated as a top show on Hulu, helping to draw 1 million unique visitors each month to its Hulu Latino page. Since 2015, East Los High has received 5 Daytime Emmy Award nominations, including “outstanding new approaches to drama series” in 2015 and “outstanding digital daytime drama series” in 2016.

EAST LOS HIGH PROGRAM EVALUATION

Program evaluation of edutainment programs in the 1980s and 1990s relied primarily on audience surveys. In recent decades, more methods are being used,30 including studies that employ experimental design to assess the effect of various narrative persuasion mechanisms.24,31 Telephone hotlines have tracked viewer response postexposure to an edutainment program. Participant observation and in-depth interviews have provided deeper insights into the viewer’s experience.30

METHODS

We adopted a mixed methods approach to evaluate East Los High, season 1: (1) analytics tracking to assess audience reach, which monitored Web traffic to the East Los High Web site and to NGO partners’ Web sites and widgets; (2) a viewer survey to assess narrative engagement and intended outcomes; and (3) a laboratory experiment with nonviewers of East Los High to compare the effect of transmedia edutainment with other forms of narrative presentation. Our complementary methods included (1) social network analysis and content analysis to understand the social dynamics, message framing, and user-generated content on East Los High’s social media presence and (2) participant observation and in-depth interviews with young Latino couples to reveal East Los High’s influence on their sexual decision-making. Preliminary results of these analyses are reported elsewhere.32–34

Analytics Tracking

We collected anonymous unobtrusive tracking data through Google Analytics from May 2013 to January 2014 to capture East Los High audience reach during the preprogram publicity, the premiere of season 1, and after season 1 ended. We recorded number of visitors, number of page views, average duration of page views, and geographical location of visitors. We used geographical information system software to generate spatiotemporal dynamic visualizations of the geographical diffusion of East Los High Web site visitors over time. Two NGO partners (Planned Parenthood and StayTeen.org) independently monitored and shared the statistics of their Web traffic and health service widgets on the East Los High Web site.

Viewer Survey

We embedded an online survey on the East Los High Web site and promoted it on social media with custom incentives. Between August and September 2013, 202 viewers who watched at least 20 of the 24 episodes completed the survey, including 110 Latinas who were aged 23 years or younger—the program’s primary target audience (Table 1). Approximately 55% of those watched the entire series more than once, and 87% viewed transmedia extensions.

TABLE 1—

Characteristics of East Los High Viewer Survey Participants: United States, 2013

| Characteristic | Total Sample (n = 202), Responded Yes, % | Primary Targeta (n = 110), Responded Yes, % |

| Female | 91 | 100 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 78 | 100 |

| Age, y | ||

| 12–17 | 25 | 35 |

| 18–23 | 50 | 66 |

| 24–30 | 15 | 0 |

| 31–60 | 10 | 0 |

| Education completed | ||

| Elementary school | 1 | 2 |

| Middle school | 10 | 11 |

| High school | 64 | 72 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 20 | 12 |

| Master’s degree and beyond | 5 | 0 |

| Household annual income, $ | ||

| < 20 000 | 39 | 43 |

| 20 000–49 999 | 35 | 43 |

| 50 000–79 999 | 19 | 7 |

| ≥ 80 000 | 7 | 0 |

| Pregnant adolescent connection | ||

| Self | 9 | 5 |

| Mother | 21 | 22 |

| Aunt | 15 | 19 |

| Sister | 14 | 12 |

| Cousin | 41 | 48 |

| Niece | 4 | 2 |

| Friend | 68 | 76 |

| Acquaintance | 35 | 34 |

The primary target audience of East Los High is Latina adolescents and young women because they are critical to the issues of safe sex and adolescent pregnancy and are avid consumers of dramas and online video streaming.

Participants answered closed- and open-ended questions about their impressions of the program, their engagement with its narrative elements, their interpersonal discussions about the show, and their knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions related to sexual and reproductive health. We derived measures of audience experience from established scales of transportation, identification, and narrative engagement (Table 2). We adapted health-related outcome measures from the 2013 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey.16,18,20,24,35

TABLE 2—

East Los High Audience Narrative Engagement: United States, 2013

| Survey Item | Total Mean ±SD | Target Mean ±SD |

| Audience program ratinga | ||

| Storyline appeal | 4.68 ±0.79 | 4.61 ±0.83 |

| Enjoyment of Hulu drama series | 4.88 ±0.45 | 4.93 ±0.26 |

| Enjoyment of transmedia extensions | 4.56 ±0.86 | 4.58 ±0.83 |

| Production quality | 4.74 ±0.53 | 4.73 ±0.55 |

| Wanting more | 4.96 ±0.23 | 4.97 ±0.17 |

| Audience narrative engagementb | ||

| Attention focus | 1.34 ±0.50 | 1.35 ±0.49 |

| Narrative understanding | 1.37 ±0.56 | 1.31 ±0.49 |

| Narrative presence | 1.51 ±0.67 | 1.49 ±0.68 |

| Perceived realism | 1.35 ±0.51 | 1.30 ±0.48 |

| Cognitive processing | 1.42 ±0.62 | 1.42 ±0.62 |

| Emotional engagement | 1.44 ±0.62 | 1.46 ±0.67 |

| Audience character identificationc | ||

| You feel like you know | ||

| Jacob | 1.43 ±0.70 | 1.40 ±0.70 |

| Jessie | 1.57 ±0.82 | 1.48 ±0.77 |

| Maya | 1.45 ±0.81 | 1.53 ±0.88 |

| Ceci | 1.72 ±0.94 | 1.70 ±1.04 |

| Vanessa | 1.91 ±1.05 | 1.91 ±1.12 |

| Abe (Ceci’s abusive boyfriend) | 3.14 ±1.34 | 3.19 ±1.42 |

| Freddie (Vanessa trades him sex for a favor) | 3.24 ±1.33 | 3.13 ±1.31 |

| Ramon (Maya’s rapist) | 3.09 ±1.30 | 2.98 ±1.25 |

| You like | ||

| Jacob | 1.31 ±0.70 | 1.22 ±0.62 |

| Jessie | 2.28 ±1.40 | 2.21 ±1.44 |

| Maya | 1.51 ±0.99 | 1.52 ±1.00 |

| Ceci | 1.55 ±0.76 | 1.51 ±0.72 |

| Vanessa | 2.73 ±1.50 | 2.62 ±1.50 |

| Abe (Ceci’s abusive boyfriend) | 3.72 ±1.43 | 3.55 ±1.51 |

| Freddie (Vanessa trades him sex for a favor) | 3.40 ± 1.46 | 3.25 ±1.47 |

| Ramon (Maya’s rapist) | 3.76 ±1.40 | 3.63 ±1.45 |

Laboratory Experiment

We used a 2 (nondramatic vs dramatic narratives) × 3 (text vs multimedia vs transmedia) partial factorial design to test the effect of different storytelling formats on East Los High’s target audience. A priori power analysis with the α level set at 0.05, power = 0.80, and a medium effect size of F = 0.25 for 5 groups and 3 repeated measures suggested a sample size of at least 14 participants in each condition. We screened 1379 students at the University of Texas at El Paso; 309 met our inclusion criteria: female, aged 18 to 28 years (mean = 20.74; SD = 2.39), Latina, with sufficient English proficiency, and a nonviewer of East Los High, Degrassi, and 16 & Pregnant. Of the 309, 136 completed the study. We randomly assigned them to 1 of 5 conditions.

Participants in condition 1 (n = 30) were the control group; there was no intervention for them. In conditions 2 to 5, we asked participants to read a text or view a video as follows. In condition 2 (n = 21), participants read a nondramatic text version of East Los High presented as a newspaper story. In condition 3 (n = 21), participants read a dramatic text version presented as an East Los High script. In condition 4 (n = 32), participants viewed an online drama presented as an abbreviated version of the East Los High Hulu original series. In condition 5 (n = 32), participants viewed a transmedia version of the series presented as the online drama along with selected transmedia extensions. We carefully selected the content according to the program’s objectives, and the messages were identical across all experimental conditions.

Repeated measures of narrative engagement, knowledge (of correct use of condoms, birth control pills, and emergency contraception), attitudes (on sex education, women’s right to choose abortion, the importance of HIV testing, the importance of sex communication), and behavior (used protection during last instance of sexual intercourse, engaged in sex communication) occurred at baseline (T1), posttest (T2), and a 2-week follow-up (T3). We collected data from June to August 2014 and gave participants gift card rewards. We used mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) models to test the effect of stimuli in different conditions over time in SPSS version 23 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

This project is a large-scale program evaluation using a multi-method, multi-phase approach. Given the space constraints, we report the most important and insightful findings in this article.

Analytics Tracking

During the 9 months of tracking (most of it post–season 1), the East Los High Web site attracted 215 964 visits from 123 728 unique visitors, with 870 684 page views and an average of 9.2 minutes per viewing session. About 57% were new visitors and 43% were returning visitors. Interestingly, even after season 1 ended, the East Los High Web site attracted 36 935 new visitors and 34 784 returning visitors in 136 251 viewing sessions, with 535 124 page views and an average of 12.0 minutes per viewing session. The resources page had 5254 page views with information and hyperlinks to NGO partners.

Planned Parenthood reported that during season 1, 22% of their total widget visits (n = 26 414) were accessed through the East Los High Web site. In the 6 weeks thereafter, they had 30 868 widget visits accessed through the East Los High Web site, including 52% new visits. They had 4795 direct East Los High referrals to the Planned Parenthood Web site, including 72% new visits.

StayTeen.org reported that the season premiere day generated a notable spike in traffic to their Web site, with almost 4000 visits—more than double the traffic on a typical day. About half of these visits were from direct traffic, with users entering the URL in their Web browser. In the first month, StayTeen.org had about 566 000 visits—11% higher than a comparable period—and there was a 53% increase in direct traffic.

Analyses of the geographical information system data indicated that East Los High reached an audience across all 50 states and the District of Columbia.36 Most visitors were located in states with a high Latina/o population and the highest rates of adolescent pregnancy (California, Texas, Florida, New York, Illinois, Arizona, and New Jersey).1,37 Visitors from California accounted for 46% of the total traffic. Within California, 31% of the Web traffic came from Los Angeles, and 47% of the visitors came from cities with both a high Latina/o population and high poverty rates. Although East Los High was primarily developed for the English-speaking Latina/o youth population in the United States, 10 398 visitors hailed from another 163 countries, including 20 countries in Latin America.38

Viewer Survey

Participants gave East Los High 5-star ratings on its story appeal, its production quality, their enjoyment of the drama series and its transmedia extensions, and their desire for more shows like East Los High (Table 2). Audience involvement with East Los High was evident in their undivided attention to the show, their clear understanding of its narrative, their immersion and felt presence in the story, their perception of the characters’ realism, their constant cognitive processing of the show’s elements, and their high degree of emotional engagement (Table 2).

Participants exhibited strong identification with the main characters. The most liked characters were those who demonstrated positive attitudes and behaviors; the least liked characters embodied violence, abuse, and irresponsibility (Table 2). All participants considered themselves East Los High fans, and most were active on social media by way of liking, commenting, sharing, retweeting, and hash tagging East Los High posts. Approximately 19% of the participants were active endorsers of East Los High, 25% were disseminators, and 53% were advocates. Participants in the target sample reported discussing East Los High on social media with their friends (84%), siblings (66%), parents (31%), and relatives (26%). Furthermore, 80% engaged in face-to-face discussions; 69% did so via text messaging and 46% did so by mobile phone.

Half of the participants reported learning at least 1 of 10 facts about correct condom use that they did not know, and 36% reported learning at least 1 of 7 facts about birth control pills and emergency contraception. Regarding attitudes and behavioral intentions about sexual responsibility, 95% agreed that “it doesn’t matter if you are a girl or a guy, you should take your own responsibility for birth control,” 98% said they were likely to use condoms correctly from now on, and 91% said they were likely to use condoms during sex every time.

Regarding unprotected sex, 86% said they were likely to adopt emergency contraception, and 93% said they were likely to recommend emergency contraception to someone they know. Almost all participants were aware of testing services for sexually transmitted infections (91%), HIV (90%), and pregnancy (100%) although most had not been tested (69%, 72%, and 70%, respectively).

After watching East Los High, willingness to be tested for sexually transmitted infections, HIV, and pregnancy was higher (96%, 96%, and 95%, respectively) as was the resolve to recommend testing to others (99%, 99%, and 100%, respectively). Most participants in the target sample knew that social services existed for pregnant adolescents (84%), child adoption (91%), and abortion (86%), but not many knew where to go for these services (40%, 41%, and 36%, respectively). After watching East Los High, a majority of participants said they were more likely to recommend these services (93%, 89%, and 75%, respectively).

Moreover, 48% of the participants visited the East Los High resources page; of those, 100% found the information to be helpful, and 81% shared the resources page with others. One participant’s comment in the open-ended questions provides an excellent summary:

East Los High changed my life a lot because it was so realistic. . . . I learned a lot of things that my sex-ed class didn’t talk to us about such as abortion and other options. It taught me that I have choices and responsibilities.

Laboratory Experiment

Participants in the experimental conditions had higher transportation and character identification, although this was not significantly better in the transmedia condition (condition 5) except for identification with Jacob. This may be because of the substantial abbreviation of the original drama series and transmedia content in condition 5. Mixed ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of time for participants assessing knowledge of correct condom use (F(2/262) = 15.15; P < .001; partial η2 = 0.104), suggesting that participants’ knowledge changed over time. Pairwise comparisons showed a significant knowledge gain about correct condom use from T1 to T2 (P < .001) and from T1 to T3 (P = .007) but not from T2 to T3 (P = .062), indicating retention of the knowledge gain.

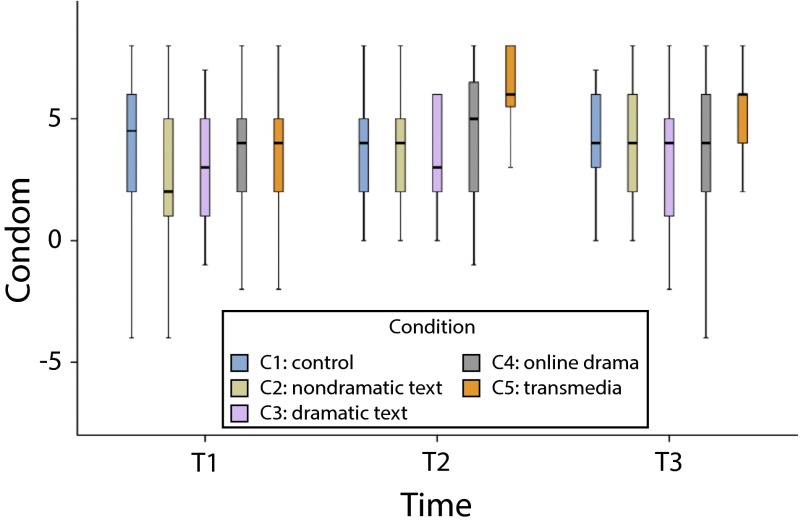

There was also a significant main effect of condition (F(4/131) = 4.62; P = .002; partial η2 = 0.124), suggesting that some conditions yielded better outcomes than did others. In post hoc tests, we found no significant differences between pairs of conditions 1 to 4; however, condition 5 was significantly higher, suggesting a higher positive effect of transmedia storytelling in this format than in all other formats tested. Moreover, there was a significant interaction effect (F(8/262) = 3.74; P < .001; partial η2 = 0.103), suggesting that condition 5 achieved significantly more knowledge gain than do other conditions about correct condom use from baseline to posttest and sustained it till the 2-week follow-up (Figure 2).39

FIGURE 2—

Clustered Boxplots of Knowledge About Correct Condom Use Over Time by Condition: El Paso, TX, 2014

Note. T1 = baseline. CONDOM is the sum of 8 items about correct condom use, with each correct answer coded as 1 and each incorrect answer coded as –1. The boxplots show the distributions of CONDOM knowledge scores for the 3 different periods across all 5 conditions. Each box represents the interquartile range, the whiskers at the top and bottom of the box indicate the upper and lower quartile, and the middle line in each box represents the median. Descriptive U3 effect size statistics60 indicated that at T2 (posttest), 94% of participants in condition 5 had higher scores than did those in condition 4, and 97% of participants in condition 5 had higher scores than did those in condition 3, condition 2, and condition 1; at T3 (2-week follow-up), 69% of participants in condition 5 had higher scores than did those in condition 2, and 91% of participants in condition 5 had higher scores than did those in condition 4, condition 3, and condition 1.39

An upward trend of knowledge about birth control pills and emergency contraception was evident, with higher scores for participants in condition 5, although the differences from those in other conditions were not statistically significant. All attitude measures were high across conditions and over time, showing a stable and positive tendency. Behavior results of using protection during last instance of sexual intercourse among sexually active participants were not significant because of small subsample size.

Sex-related communication with family, friends, and health professionals increased over time for conditions 4 and 5, although it was not statistically significant. After being exposed to East Los High, 30% of the participants in the experimental conditions searched online for more, 30% talked to people about the show, 6% watched full episodes, and 1% of active Facebook users and 7% of active Twitter users started following East Los High. As expected, participants in the laboratory experiment displayed less enthusiasm about East Los High than did the self-selected heavy viewers who participated in the survey.

DISCUSSION

The East Los High transmedia edutainment intervention and our evaluation findings have significant implications for scholars and practitioners of health promotion and education, specifically regarding the sexual and reproductive health of Latina/o (or minority) youths. Digital health is a critical area for public health promotion and education among youths and minority groups.

East Los High is the first culturecentric intervention that was designed to use transmedia edutainment to promote sexual and reproductive health, especially among Latina adolescent girls and young women. The program development and evaluation were informed by theories of narrative persuasion and realized through collaborative partnerships between Hollywood-based independent producers; national, regional, and local NGOs; and edutainment researchers. In our summative research on East Los High, season 1, we focused on audience reach, narrative engagement, and intervention impact, using primarily analytics tracking, a viewer survey, and a laboratory experiment.

Major Findings and Implications

Viewership and Web traffic to the program Web site suggested that the audience responded to East Los High with great enthusiasm. In addition to the millions of viewers who watched it on Hulu, hundreds of thousands visited the show’s Web site to access full episodes, transmedia extensions, and other resources. Tens of thousands of visits occurred after season 1 ended. The trend over 9 months indicated that viewers were spending more time on the East Los High Web site, and almost half returned for multiple visits, showing the potential of transmedia edutainment as a sustainable platform for large-scale, longer-term audience engagement.

Moreover, the East Los High Web site served as a portal to additional health and social services via embedded widgets and referral to NGO partners’ Web sites. These tight connections between the intervention exposures and an infrastructure for follow-up actions (e.g., personalized health information seeking) can greatly boost the efficacy for behavior change. Furthermore, East Los High was popular across the United States and around the world, reaching geographical areas with the highest Latino populations, adolescent pregnancy rates, and poverty rates. This suggests that culturally sensitive interventions can help address, and even reduce, health disparities in minority groups.

The viewer survey offered a snapshot from 202 East Los High fans, who were predominantly young Latinas with low socioeconomic status, hence at risk for adolescent pregnancy. Their high ratings of the program and their fervent desire for more such programs suggest that the transmedia edutainment approach was effectively implemented in East Los High.

Viewers consistently demonstrated high levels of narrative engagement, carefully attended to the show, understood the nuances of the characters and their stories, felt immersed in the story world of East Los High, related content to their real-life experiences, actively reflected on the plotlines, and were emotionally engaged.

Furthermore, among the target audience group of Latina girls and women, East Los High spurred interpersonal discussions. They talked to their friends, siblings, parents, and relatives about East Los High face to face and via social media, text messages, and telephone calls. They reported a high level of awareness of various health services for testing and assistance to pregnant adolescents but somewhat lower levels of actual testing behavior and knowledge of where to seek help.

After watching East Los High, participants indicated learning new information (correct use of condoms, birth control pills, and emergency contraception), and they displayed higher levels of behavioral intentions (using and recommending testing and pregnancy services) and appreciation for the comprehensive resources on the show’s Web site. Overall, the survey results suggested that East Los High resonated well with its target audience; they perceived the program to be compelling, educational, and transformative. Their enthusiasm suggests that narrative-based transmedia edutainment interventions like East Los High can cultivate a fan base for deeper learning, lasting engagement, and broader social change.

The laboratory experiment added evidence of the East Los High effects on 136 nonviewers who fit the characteristics of its target audience and were randomly assigned to 1 of the 5 conditions. Although the messages embedded in the stimuli were identical, the results varied. There were encouraging positive trends over time and tendencies showing the advantages of transmedia, but most were not statistically significant and warrant future investigation.

However, one revealing result regarded knowledge of correct condom use: transmedia yielded significantly better outcomes than did other conditions over time. This may have resulted from the extended scene of Maya’s conversation with a health counselor about condom use, which was one of the selected transmedia extensions in condition 5. This suggests that even though the message of promoting condom use for safe sex and preventing sexually transmitted infections and unplanned pregnancies is the same across all experimental conditions, using transmedia to highlight critical and accurate information as incorporated in the dialogue with a main character can give the intervention a turbocharged boost.

Among the nonviewers, 30% reported searching for information and discussing East Los High after their participation in the experiment, although few watched full episodes or started following East Los High on social media. Our results indicate that the self-selection among East Los High fans can make a difference in how they interact with the content. Future interventions should be mindful of the match between the edutainment themes and presentation styles with the characteristics, motivations, interests, and media habits of a potential target audience.

Changing demographics and consumer markets require public health interventions to be adaptive and versatile to achieve broader reach, deeper engagement, and more positive and sustainable outcomes. East Los High is exemplary in that it is rewriting what is programmatically possible. The development and evaluation of East Los High, season 1 demonstrates that culturally sensitive transmedia edutainment is an innovative and promising approach to health promotion among minority populations, such as young Latina/o Americans.

Limitations

Despite the merits of mixed methods program evaluation for East Los High, season 1, there are several limitations to our work. First, the analytics tracking data were aggregated; hence, no individual demographic information or actual health seeking behavior could be directly attributed to the program. More advanced analytics tools and features should be designed and used in collaboration with NGO partners to provide more granular digital data points at the personal level while respecting individual privacy.

Second, because of time and financial constraints, we were able to collect postexposure survey data from only a small sample of viewers and conduct a laboratory experiment with only a limited number of nonviewers. Large-scale randomized field studies would be useful for comparing the intervention experience and effect between viewers and nonviewers, Latinos and other racial/ethnic groups, and younger and older individuals over a longer period of time.24,40

Finally, the primary target audience of East Los High was Latina adolescents and young woman who enjoy watching dramas streamed online. We acknowledge the important roles that males and parents play in communicating about, making decisions about, and practicing sexual and reproductive health. Although these were addressed to some degree in the East Los High programming, they warrant separate investigation beyond the scope of our project.

Conclusions

Pioneering transmedia edutainment interventions such as East Los High are tremendously promising for health promoters and educators, and more rigorous research design and empirical testing with future interventions are needed to validate this further.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research project was funded by the Population Media Center, Shelburne, Vermont.

We deeply appreciate the help from the East Los High production team at Wise Entertainment, our nongovernmental organization partners (especially Planned Parenthood Federation of America and StayTeen.org), and members of our research team: Carliene Quist, Anu Sachdev, Weiai Xu, Gregory D. Saxton, Michael Reinti Jr., Susan Kum, Gabriel A. Lira, Dana Himoff, Kristin Maki, Claudia Boyd, and Georges Khalil.

Note. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the Population Media Center.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

The University at Buffalo, The State University of New York institutional review board approved any primary data collection that involved human research participants in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown A, Lopez MH. Mapping the Latino population, by state, county and city. 2013. Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/08/29/mapping-the-latino-population-by-state-county-and-city. Accessed January 23, 2015.

- 2.National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Fast facts: teen pregnancy and childbearing among Latina teens. 2015. Available at: https://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/fast_facts_-_teen_pregnancy_and_childbearing_among_latino_teens_july_2015.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- 3.Goesling B, Colman S, Trenholm C, Terzian M, Mooer K. Programs to reduce teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, and associated sexual risk behaviors: a systematic review. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54(5):499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maness SB, Buhi ER. A systematic review of pregnancy prevention programs for minority youth in the US: a critical analysis and recommendations for improvement. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2013;6(2):91–106. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Fast facts: Latino teens’ sexual behavior and contractive use: data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2013. 2014. Available at: https://thenationalcampaign.org/sites/default/files/resource-primary-download/fast-facts-hispanic-teen-sexual-behavior-and-contraceptive-use-yrbs-2013.aug2014.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2015.

- 6.Cardoza VJ, Documét PI, Fryer CS, Gold MA, Butler J., III Sexual health behavior interventions for U.S. Latino adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25(2):136–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guilamo-Ramos V, Goldberg V, Lee JJ, McCarthy K, Leavitt S. Latino adolescent reproductive and sexual health behaviors and outcomes: research informed guidance for agency-based practitioners. Clin Soc Work J. 2012;40(2):144–156. doi: 10.1007/s10615-011-0355-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larkey LK, Hecht M. A model of effects of narrative as culture-centric health promotion. J Health Commun. 2010;15(2):114–135. doi: 10.1080/10810730903528017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singhal A, Cody MJ, Rogers EM, Sabido M, editors. Entertainment–Education and Social Change: History, Research, and Practice. New York, NY: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singhal A, Wang H, Rogers EM. The entertainment–education communication strategy in communication campaigns. In: Rice RE, Atkins C, editors. Public Communication Campaigns. 4th ed. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage; 2013. pp. 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherry JL. Media saturation and entertainment–education. Commun Theory. 2002;12(2):206–224. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kunkel D, Eyal K, Finnerty K, Biely E, Donnerstein E. Sex on TV 4. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scolari CA. Transmedia storytelling: implicit consumers, narrative worlds, and branding in contemporary media production. Int J Commun. 2009;3:586–606. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins H. Convergence Culture: Where Old & New Media Collide. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slater MD, Rouner D. Entertainment–education and elaboration likelihood: understanding the processing of narrative persuasion. Commun Theory. 2002;12(2):173–191. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moyer-Gusé E. Toward a theory of entertainment persuasion: explaining the persuasive effects of entertainment–education messages. Commun Theory. 2008;18(3):407–425. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandura A. Social cognitive theory for personal and social change by enabling media. In: Singhal A, Cody MJ, Rogers EM, Sabido M, editors. Entertainment–Education and Social Change: History, Research, and Practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green MC, Brock TC. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79(5):701–721. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy ST, Frank LB, Moran MB, Patnoe-Woodley P. Involved, transported, or emotional? Exploring the determinants of change in knowledge, attitudes, and behavior in entertainment–education. J Commun. 2011;61(3):407–431. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busselle R, Bilandzic H. Measuring narrative engagement. Media Psychol. 2009;12(4):321–347. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H, Fawcett J, DeMarco R. Storytelling/narrative theory to address health communication with minority population. Appl Nurs Res. 2015;30(154):58–60. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen F, Sheer VC, Li R. Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: a meta-analysis. J Advert. 2015;44(2):105–113. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zebregs S, van den Putte B, Neijens P, de Graaf A. The differential impact of statistical and narrative evidence on beliefs, attitude, and intention: a meta-analysis. Health Commun. 2015;30(3):282–289. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2013.842528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy ST, Frank LB, Chatterjee JS et al. Comparing the relative efficacy of narrative vs nonnarrative health messages in reducing health disparities using a randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2117–2123. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castro T. “East Los High” on Hulu is first English language show with all Latino cast. 2013. Available at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/06/06/east-los-high-hulu_n_3395762.html. Accessed November 4, 2014.

- 26. Fritz B. Hollywood takes Spanish lessons as Latinos stream to the movies. Wall Street Journal. August 10–11, 2013:A1, A10.

- 27.Lopez MH, Gonzalez-Barrera A, Patten E. Closing the digital divide: Latinos and technology adoption. 2013. Available at: http://www.pewhispanic.org/2013/03/07/closing-the-digital-divide-latinos-and-technology-adoption. Accessed November 4, 2014.

- 28.Razzetti G. Latinos and media usage revisited. 2012. Available at: http://www.clickz.com/clickz/column/2134703/latinos-media-usage-revisited. Accessed November 13, 2013.

- 29.Del Barco M. East LA homegirl goes Hollywood. 2013. Available at: http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/09/13/218943510/east-la-homegirl-goes-hollywood. Accessed November 4, 2014.

- 30.Singhal A, Rogers EM. A theoretical agenda for entertainment–education. Commun Theory. 2002;12(2):117–135. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moyer-Gusé E, Nabi RL. Comparing the effects of entertainment and education television programming on risky sexual behavior. Health Commun. 2011;26(5):416–426. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.552481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang H, Xu W, Saxton GD. Network structures for a better Twitter community. Paper presented at the 2014 Social Media and Society International Conference. Toronto, Canada; September 27-28, 2014.

- 33. Wang H, Xu W, Saxton GD. Cultivating a fan base on Facebook for public health promotion: the case of East Los High. Paper presented at the Medicine 2.0 International Conference. Maui, HI; November 13-14, 2014.

- 34.Sachdev A, Singhal A. Where international, intranational, and development communication converge: effects of East Los High, an entertainment–education Web series, on sexual decision-making of young Latino/a couples. J Dev Comm. 2015;26(2):15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/data.htm. Accessed July 5, 2013.

- 36. East Los High state level spatial-temporal dynamic visualization. Available at: https://www.dropbox.com/s/hdzqbu6e6q6q1lb/ELH_State_May_v1.avi?dl=0. Accessed October 11, 2014.

- 37.Kost K, Henshaw S. U.S. teen pregnancies, births and abortions, 2008: state trends by age, race and ethnicity. 2013. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrendsState08.pdf. Accessed February 14, 2014.

- 38. East Los High national level spatial-temporal dynamic visualization. Available at: https://www.dropbox.com/s/9sog7423220aqun/ELH_World%204-14-14.avi?dl=0. Accessed October 11, 2014.

- 39.Valentine JC, Aloe AM, Lau TS. Life after NHST: how to describe your data without “p-ing” everywhere. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2015;37(5):260–273. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaughan PW, Rogers EM, Singhal A, Swalehe RM. Entertainment–education and HIV/AIDS prevention: a field experiment in Tanzania. J Health Commun. 2000;5(suppl):81–100. doi: 10.1080/10810730050019573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]