Abstract

Objectives. To assess potential reductions in premature mortality that could have been achieved in 2008 to 2012 if the minimum wage had been $15 per hour in New York City.

Methods. Using the 2008 to 2012 American Community Survey, we performed simulations to assess how the proportion of low-income residents in each neighborhood might change with a hypothetical $15 minimum wage under alternative assumptions of labor market dynamics. We developed an ecological model of premature death to determine the differences between the levels of premature mortality as predicted by the actual proportions of low-income residents in 2008 to 2012 and the levels predicted by the proportions of low-income residents under a hypothetical $15 minimum wage.

Results. A $15 minimum wage could have averted 2800 to 5500 premature deaths between 2008 and 2012 in New York City, representing 4% to 8% of total premature deaths in that period. Most of these avertable deaths would be realized in lower-income communities, in which residents are predominantly people of color.

Conclusions. A higher minimum wage may have substantial positive effects on health and should be considered as an instrument to address health disparities.

The 1938 Fair Labor Standard Act (29 U.S.C.A. § 201 et seq.), which established a minimum wage in the United States, declared that its intention was the “elimination of labor conditions detrimental to the maintenance of the minimum standards of living necessary for health, efficiency and well-being of workers.” The US minimum wage reached its highest real dollar value in 1968, more than 45 years ago, and the federal minimum wage was last increased in 2009.

As research on income and health consistently demonstrates that lower income and poverty are associated with worse health outcomes and earlier death,1–5 the recent national advocacy across the United States to raise the minimum wage as a way of improving the income of the working poor could also have important health consequences.6–11 In New York City (NYC), which is among the most expensive places to live in the United States, the standard minimum wage is currently $9.00 per hour.12 Recent legislation has established a $15.00 per hour minimum wage in several municipalities, including San Francisco and Seattle,11 and advocates in NYC are calling for a similar increase.13

The impact of a $15 minimum wage on family and neighborhood income depends critically on the employment responses to a higher minimum wage. Recent studies have found a range of responses, from a small increase to a modest reduction in employment among low-wage workers following a minimum wage hike.14–18 Although the economic impact of increasing the minimum wage has been the primary focus of debate in NYC,19 less attention has been given to the possible health consequences of such a policy, including the reduction of health inequities.

To fill that gap, we explored the potential impact of a $15 per hour minimum wage on all-cause premature mortality among NYC residents. We used area-based measures of income and premature mortality to create an ecological model and explore the reduction in premature mortality that could have been achieved from 2008 to 2012 if NYC’s minimum wage had been $15 per hour during that period. Recognizing the uncertain effects of a higher minimum wage on the NYC labor market, we assumed 3 alternative scenarios in the analysis.

METHODS

We used the 2008 to 2012 NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Vital Statistics data and population estimates20 to calculate the crude rate of premature death in each of NYC’s 59 community districts: our outcome of interest. With few exceptions, community districts correspond to the Public Use Microdata Areas as defined by the US Census Bureau and on average have approximately 140 000 residents. Although definitions of the “neighborhood” can vary,21 the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has begun to focus on health inequities across community districts because, with their community boards, community districts represent the most local level of government and are a critical area for community planning and decision-making.

Our key predictor of interest was the proportion of residents who were low income—defined as having a family income below 200% of the 2012 federal poverty level determined by the US Department of Health and Human Services, which is generally considered a factor for income-related health disparities—at the community district level. We derived this information from American Community Survey data collected from 2008 to 2012.22 To assess the potential effects of a higher minimum wage on neighborhood income, we used individual-level data to simulate the family income for each survey respondent under 3 different scenarios and then aggregated individual-level information to determine the proportion of residents with low-income status in a community district.

Specifically, we used the 2012 American Community Survey 5-year Public Use Microdata Sample to identify survey respondents in each community district who were low income as well as those who earned less than $15 per hour. We derived a respondent’s family income by summing the total incomes of all members in the respondent’s family. If a respondent’s family income fell below 200% of the 2012 federal poverty level on the basis of family size, we categorized the respondent as having low income. We imputed the hourly wage by dividing annual labor earnings for a respondent by the product of the number of hours worked in the past week and the number of weeks worked in the past year.

Analytic Plan

We conducted our study in 3 stages. First, we performed an ecological analysis of premature death in NYC using linear regression techniques weighted by the size of the neighborhood population younger than 65 years to determine whether there was an independent association between the crude rate of premature death and the proportion of residents who were low income. The dependent variable in the model was the crude rate of premature death in a community district from 2008 to 2012, including only deaths among NYC residents that occurred in NYC.

Because the greatest disparities in mortality associated with socioeconomic status occur between ages 45 and 65 years,1,23 a cutpoint of 65 years may yield wider variability in premature mortality among neighborhoods; therefore, we used 65 years instead of the standard 75 years as the cutpoint for premature mortality. Additionally, using age 65 years as a cutpoint is particularly appropriate for examining the potential impact of a higher minimum wage because only the working age population is likely to be affected by such a policy change. The independent variables included in our regression were the proportion of residents younger than 65 years who were low income as our key predictor of interest; control variables were the proportions of residents younger than 65 years who were women, aged 45 years or older, foreign-born, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other race, as well as those who were aged 25 years and older without a college education.

Second, we conducted simulations to assess the impact of a $15 minimum wage on the proportions of low-income residents in NYC neighborhoods under 3 different assumptions of labor market dynamics.

As the minimum wage in NYC ranged from $7.15 to $7.25 per hour between 2008 and 2012, in the first scenario we assumed that a higher minimum wage would raise the hourly wage of the non–self-employed earning $7.15 to $14.99 to $15.00. Additionally, we assumed that the level of employment would remain constant with a higher minimum wage.15,16

In the second scenario, we followed an approach similar to that adopted in a previous study by assuming that a $15.00 minimum wage would create spillover effects by raising the hourly wage of the non–self-employed earning near the new minimum, even if not required by law, so that the hourly wage of the non–self-employed earning $7.15 to $15.99 increased to $15.00 to $16.00 and the non–self-employed earning $6.15 to $7.14 increased to $6.16 to $14.99.24 Again, in this scenario we assumed employment would remain constant.

In the third scenario, we assumed that a higher minimum wage would not have spillover effects and would result in a loss of employment for 15% of the non–self-employed earning $7.15 to $15.00 per hour.17,18 We derived this figure from previous studies that found employment reductions associated with a higher minimum wage, but because there is limited evidence on who may lose employment among those studies, we assumed that a random selection of 15% of the non–self-employed workers earning $7.15 to $15.00 hourly would lose their jobs owing to a higher minimum wage.

In all 3 scenarios, we assumed that the number of hours worked for individuals who do not experience a job loss would remain the same25,26 and that the wages of self-employed individuals would not change as a result of a higher minimum wage.

For the final part of this analysis, we used the ecological model of premature death to determine the differences between the levels of premature mortality predicted by the actual proportions of low-income residents in 2008 to 2012 and the levels predicted by the proportions of low-income residents under a hypothetical $15 minimum wage. These differences represent the potential reductions in premature mortality owing to a $15 minimum wage. We ran this model using the 3 sets of figures derived from the simulations to estimate the possible range of results.

Income as a Proxy for Multiple Determinants of Health

NYC data showed that lower income was associated with a wide range of health risk factors, such as physical inactivity, poor nutrition, obesity, smoking, depression, and reduced health access.27 Additionally, a lack of financial resources may adversely affect the management of chronic diseases and the prevention or treatment of their complications.28

We assumed that any increases in income stemming from a higher minimum wage would reduce the prevalence of these risk factors for health, which might lead to fewer premature deaths, although research has shown that increased income may also reduce mortality risk through other mechanisms.29 In other words, income serves as a proxy in the model for all income-related factors that would vary with an increase in minimum wage to $15 per hour.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the means for the variables included in the ecological model of premature death stratified by the proportion of low-income population in the neighborhood. It can be discerned that there is a neighborhood income gradient in NYC premature mortality: the premature death rate increased with the proportion of low-income population in the neighborhood. The crude rate of premature death was nearly twice as high in community districts with the highest proportions of low-income population as in those with the lowest proportions of low-income population (251 vs 128 per 100 000). A large low-income population, however, was not the only distinguishing factor for neighborhoods with high premature death rates. Neighborhoods with high premature death rates also had substantially greater proportions of Hispanics, non-Hispanic Blacks, and residents without college education.

TABLE 1—

Means for Community District–Level Variables Stratified by the Proportion of Population With Low Income: American Community Survey and Vital Statistics Data, New York City, 2008–2012

| Proportion of Low-Income Population |

|||||

| Characteristic | < 20%a | 20%–34% | 35%–49% | ≥ 50% | All New York City |

| No. community districts | 10.0 | 14.0 | 20.0 | 15.0 | 59.0 |

| Premature death rate,b % | 128.0 | 175.0 | 212.0 | 251.0 | 199.0 |

| Low income, % | 17.3 | 30.0 | 43.1 | 61.5 | 40.3 |

| Aged 45–64 y, % | 29.9 | 30.4 | 27.9 | 22.9 | 27.5 |

| Female, % | 52.0 | 50.6 | 51.4 | 51.7 | 51.4 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 61.4 | 36.7 | 22.8 | 2.5 | 32.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 8.8 | 12.6 | 31.3 | 30.5 | 22.8 |

| Hispanic | 11.0 | 22.0 | 30.6 | 50.0 | 30.2 |

| Asian | 16.1 | 19.3 | 11.2 | 5.5 | 12.5 |

| Other race | 2.8 | 3.8 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 2.6 |

| Foreign-born, % | 27.1 | 37.2 | 39.2 | 32.6 | 35.0 |

| No college education, % | 17.7 | 36.7 | 45.7 | 58.8 | 42.1 |

Note. We defined low income as family income < 200% of the federal poverty level according to the US Department of Health and Human Services.

We derived all variables as either rates or proportions of the population younger than 65 years in the community district.

We defined premature death rate as the number of deaths at younger than 65 years per 100 000.

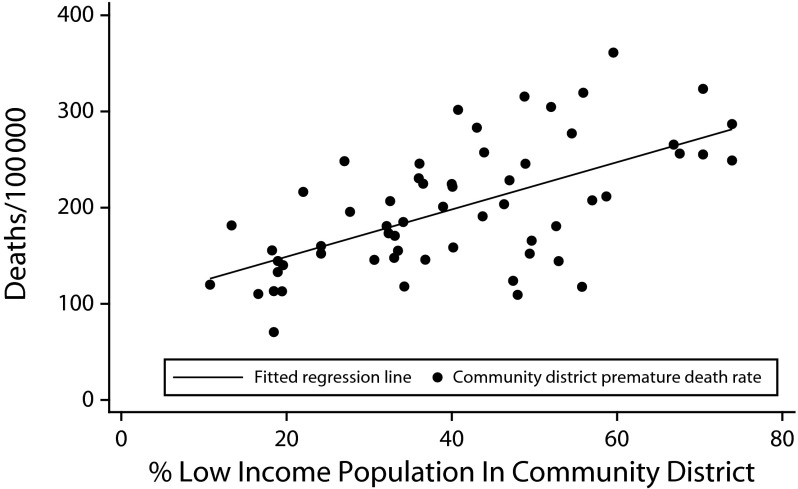

The weighted linear regression estimates for the ecological model of premature death in NYC are presented in Table 2. It is worth noting that almost 90% of the variation in the crude premature death rates among NYC community districts is accounted for by the few neighborhood-level variables included in the model (R2 = 0.87), suggesting that social determinants exert a powerful influence on the health outcomes of NYC residents. After controlling for neighborhood demographic characteristics, the crude premature death rate was significantly associated with the proportion of low-income population. Specifically, a 1% increase in the low-income population was associated with almost 3 additional premature deaths per 100 000 community district residents. The proportion of low-income population and the crude premature death rate for each community district and the relationship between these 2 variables as estimated by the model are plotted in Figure 1.

TABLE 2—

Weighted Linear Regression Estimates for Crude Premature Death Rates per 100 000: American Community Survey and Vital Statistics Data, New York City, 2008–2012

| Variable | b (SE) |

| Low incomea | 2.94 (0.65) |

| Aged 45–64 y | 7.67 (1.45) |

| Female | 4.75 (2.47) |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.91 (0.31) |

| Hispanic | 0.05 (0.37) |

| Asian | 0.09 (0.62) |

| Other race | 0.78 (1.80) |

| Foreign-born | −2.89 (0.52) |

| No college education | 0.71 (0.52) |

| Constant | −327.75 (122.94) |

| No. | 59 |

| R2 | 0.87 |

Note. We derived all variables as either rates or proportions of the population younger than 65 years in the community district.

We defined low income as family income < 200% of the federal poverty level according to the US Department of Health and Human Services.

FIGURE 1—

Estimated Relationship Between the Proportion of Low-Income Population and the Crude Premature Death Rate: American Community Survey and Vital Statistics Data, New York City, New York Community Districts, 2008–2012

Note. The independent variables in the model were the proportions of residents younger than 65 years who were low income, women, aged ≥ 45 years, foreign-born, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, Asian, other race, and aged ≥ 25 years without a college education. Premature death rates were expressed as per 100 000 community district residents younger than 65 years.

To understand the significance of the association between income and premature mortality, we conducted the thought experiment of equalizing the proportions of low-income residents across the poorest and richest community districts while holding other factors in the model constant. The differences in the proportions of low-income residents and premature mortality rates as predicted by the model are 44% and 108 per 100 000, respectively, between the community districts with the highest and lowest proportions of low-income population. The model estimates suggest that the gap in predicted premature mortality rates would disappear in our thought experiment and successful antipoverty measures may have the potential to result in substantial health benefits for NYC residents.

The effects of an increase in minimum wage to $15 per hour on the proportions of low-income residents in community districts and NYC are shown in Table 3. In the most optimistic scenario, in which a higher minimum wage would create spillover effects and result in no employment loss, the proportion of the NYC population younger than 65 years who were low income would decrease from 39.7% to 34.4%. In this scenario, 1.3 million low-income NYC residents younger than 65 years would realize an average annual increase of almost $10 000 in family income, from $26 700 to $36 100. In the pessimistic scenario, in which a $15 minimum wage causes a 15% reduction in employment among the non–self-employed earning $7.15 to $15.00 per hour, the decrease in the proportion of the population younger than 65 years who were low income would be more modest, from 39.7% to 37.1%. In all 3 scenarios, a higher minimum wage would lower the proportion of the low-income population by a greater extent in the lower-income than in the higher-income neighborhoods.

TABLE 3—

Potential Impact of a Hypothetical $15 Minimum Wage on the Proportions of Low-Income Population and Predicted Crude Death Rates by the Proportion of Low-Income Residents: American Community Survey and Vital Statistics Data, New York City, New York Community Districts, 2008–2012

| Proportion With Low Income With $15 Minimum Wage, % |

Premature Death Rate With $15 Minimum Wage, per 100 000 |

|||||||

| Proportion of Low-Income Population in Community Districts | Proportion With Low Income if No Change in Minimum Wage, % | Scenario 1a | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | Premature Death Rate if No Change in Minimum Wage, per 100 000 | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 |

| < 20% | 17.3 | 15.7 | 15.3 | 16.5 | 145.4 | 140.6 | 139.6 | 143.2 |

| 20%–34% | 30.0 | 26.6 | 25.9 | 28.1 | 169.7 | 159.5 | 157.7 | 164.0 |

| 35%–49% | 43.1 | 38.1 | 37.2 | 40.1 | 209.1 | 194.4 | 191.9 | 200.3 |

| ≥ 50% | 61.5 | 55.1 | 54.3 | 57.6 | 253.8 | 235.2 | 232.6 | 242.3 |

| All New York Cityb | 39.7 | 35.2 | 34.4 | 37.1 | 200.3 | 187.4 | 185.3 | 192.7 |

Note. We defined low income as family income < 200% of the federal poverty level according to the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Scenario 1 assumes that a higher minimum wage would create neither spillover nor employment effects. Scenario 2 assumes that a higher minimum wage would result in spillover effects but no employment effects. Scenario 3 assumes that a higher minimum wage would result in no spillover effects and a 15% reduction in employment for non–self-employed workers earning between $7.15 and $15.00 per hour.

We derived the proportions of low-income population for New York City in all scenarios using respondent-level data from the American Community Survey; we calculated the premature death rates for New York City in all scenarios as the averages of community district premature death rates.

The impact of a $15 minimum wage on crude premature death rates is presented in Table 3. A $15 minimum wage could reduce the premature death rate in NYC by as much as 15 per 100 000 in the most optimistic scenario. The total number of NYC premature deaths in 2008 to 2012 was approximately 70 000. A reduction in the crude rate of 15 per 100 000 would translate into approximately 5500 fewer predicted premature deaths from 2008 to 2012, representing 8% of the total premature deaths in NYC over the study period.

Even in the pessimistic scenario, which resulted in a decrease in employment rates, a $15 minimum wage could reduce the crude premature death rate in NYC by nearly 8 per 100 000, translating into almost 2800 fewer premature deaths and 4% of the total number of premature deaths in 2008 to 2012. As low-income neighborhoods would experience much larger reductions in the premature death rate in all 3 scenarios, most of the avertable deaths stemming from a $15 minimum wage would be realized in these low-income communities, contributing to a narrowing of health inequities across the city.

DISCUSSION

Using community-level income and mortality data from 2008 to 2012, we estimated the potential impact a hypothetical $15 minimum wage would have had in NYC during that 5-year period. Our analysis suggests that a minimum wage of $15 per hour would reduce premature deaths, averting as many as 5500 deaths over 5 years. Even if wage increases led to modest job losses, as many as 2800 deaths could be averted in this period. More than a million low-income and poor residents might see a $10 000 boost in family income on average each year, and about 400 000 could move up from below 200% of the federal poverty level.

Among households with less than 80% of the NYC median household income, approximately 60% were rent burdened (paying more than 30% of income in rent and utility costs), and more than one third were severely rent burdened (paying more than 50% of income in rent and utility costs). The severely rent-burdened households in that income category made up more than 90% of all severely rent-burdened households in NYC.30 Being burdened by such a high rent may lead to compromises in quality of housing, nutrition and food security, health care and prescription medications, and other health-promoting inputs. An increase of $10 000 in income from a $15 minimum wage may particularly help severely rent-burdened families improve their health.

Our ecological model found that holding other neighborhood factors constant, income difference may account for the gap in premature death rates between the richest and poorest communities in NYC. For example, the rate of premature death in Central Harlem, where almost 30% of residents live below the federal poverty level, is almost 4 times higher than is that in the financial district, where only 8% live in poverty. A $15 minimum wage would, therefore, have the greatest health benefit for residents in high-poverty communities, who are predominantly people of color, although premature deaths would be averted in all communities and among people of all races and ethnicities across NYC. Of course the association between premature mortality and neighborhood income may reflect cumulative effects of low neighborhood income on health over a long period of time. Hence, caution is needed in interpreting the study findings, and one should not necessarily expect to see an immediate reduction in premature death of the magnitude we estimated in our analysis if minimum wage were raised to $15 per hour in NYC.

Policy Implications

Until recently, state and local health departments have generally not taken positions on minimum wage debates, although the relationship between income and health has long been acknowledged. This analysis adds to a growing body of work by health departments to resurrect the centrality of minimum wages to population health. For example, the San Francisco, California, Health Department adopted “living wages” as essential to good health. Rajiv Bhatia et al. performed analyses to show that a minimum wage would decrease the risk of premature death by 5% for adults aged 24 to 44 years living in households with an income of about $20 000.6 Analyses of the health impact of living wage ordinances have also been done in Los Angeles, California.7 A more recent analysis by Human Impact Partners suggests that nearly 400 premature deaths among low-wage Californians would be averted.9 Some departments have taken these arguments to the legislature. In Minnesota, Edward Ehlinger, the state health commissioner, made it a priority to educate legislators about the health benefits of the minimum wage bill. He declared its successful passage in 2014 as the greatest legislative accomplishment of his tenure, noting, “Even the tobacco tax increase. . . is not as powerful as the minimum wage increase.”10(p1)

Our analysis may help increase appreciation for the potential health impact of not only minimum wage but also policies as diverse as those directed at education, labor, and transportation among legislators and the general public.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. Previous analyses of the health impact of a higher minimum wage generally relied on older, national estimates,6,7,9 which may not be universally applicable to all localities in recent times. This is because studies have shown wide variability in premature mortality both across geography and over time4,31 and a nonconstant association between income and mortality across periods.32 Our analysis was on the basis of contemporary data, although it was specific to NYC. Additionally, as our units of analysis were neighborhoods instead of individuals, we were able to focus on the ecological dimensions of social and economic factors on health.33 Lastly, our approach of triangulating local health data with American Community Survey Public Use Microdata, which are the highest quality and most detailed socioeconomic data available, at the community level could be extended to assess a wide range of policies that may influence health through the social determinants.

Although using income mortality estimates from older, national studies may be less appropriate to our analysis, it would be instructive to compare our results, which were derived from an ecological model, with those from the conventional approach, which is grounded on individual-level national studies.6,7,9 We performed an analysis using the conventional approach and found that a $15 minimum wage would still reduce premature mortality, albeit at a lower level. For example, in the scenario in which a higher minimum wage would create neither spillover effects nor employment loss, a $15 minimum wage would have averted more than 1300 premature deaths among NYC residents aged 25 to 64 years from 2008 to 2012.

This study also has many limitations. First, the ecological model did not include all health-influencing factors that are potentially correlated with neighborhood income because of concerns that many of these factors may vary with income as the minimum wage increases. Nonetheless, as a robustness check, we ran the model with additional controls, including unemployment rate, noninsurance rate, air quality, and the proportions of adults who were smokers, eating fruits and vegetables regularly, physically active, and obese, and we obtained very similar results. Although our estimates appear to be robust, we would like to acknowledge that some of the omitted income-related factors, such as green space, chronic disease states, and certain health-producing institutions or infrastructure, may not accompany an increase in minimum wage, and omission of any such factors could have biased our estimates.

Second, because mortality is a function of cumulative experiences over the life course, in our analysis we implicitly assumed that relative neighborhood income at a point in time correlates fairly well with long-term relative neighborhood income. Although this assumption may be reasonable, it is a potential weakness in our analysis.

Third, the association between premature mortality and the proportion of low-income population may not reflect a causal relationship. However, it is reasonable to assume that neighborhood income may indeed have a causal impact on premature mortality in NYC. Our results are consistent with the pervasive robust links found between premature mortality and low life expectancy and poverty and low income found in numerous other studies.1–5,31,32,34,35 It seems unlikely for such a relationship to persist among multiple populations and over time unless there is an underlying causal mechanism. Additionally, we performed our analysis at a smaller geographical level, namely Neighborhood Tabulation Areas,36,37 which are aggregations of census tracts that are subsets of Public Use Microdata Areas, and the direction and magnitude of the coefficient for the proportion of low-income population was similar.

Finally, whereas our 3 simulations used a range of estimates derived from recent studies that examined the effects of minimum wage hikes legislated across jurisdictions and over time, an increase in minimum wage to $15 per hour would be a substantially larger increase than would the minimum wage hikes that have taken place historically. As a result, its potential impact may not be analogous. And we did not explicitly model the potential impact of increased income on the eligibility for entitlements. However, it should be noted that in the context of our cross-sectional ecological model, a $15 minimum wage would reduce premature death rates of lower-income neighborhoods by essentially lowering the proportions of low-income population in these neighborhoods to the prevailing levels in higher-income neighborhoods while controlling for differences in other demographic characteristics. Because the vast majority of residents in higher-income neighborhoods were already ineligible for entitlements, we by and large implicitly accounted for the potential loss of entitlements by families experiencing increased family income owing to a higher minimum wage.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Wenhui Li, PhD, Meghna Srinath, MPH, Victoria Grimshaw, MPH, Cathy Nonas, MS, RD, Ana Garcia, MPA, and Aletha Maybank, MD, MPH, for their contributions to the study.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Human participant protection was not required because human participants were not involved in the study.

Footnotes

See also Galea and Vaughan, p. 973.

REFERENCES

- 1.Backlund E, Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ. The shape of the relationship between income and mortality in the United States. Evidence from the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(95)00090-9. discussion 21–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmot M. The influence of income on health: views of an epidemiologist. Health Aff (Milwood) 2002;21(2):31–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muennig P, Franks P, Jia H, Lubetkind E, Gold MR. The income-associated burden of disease in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(9):2018–2026. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krieger N, Rehkopf DH, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Marcelli E, Kennedy M. The fall and rise of US inequities in premature mortality: 1960–2002. PLoS Med. 2008;5(2):e46. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolf SH, Braveman P. Where health disparities begin: the role of social and economic determinants—and why current policies may make matters worse. Health Aff (Milwood) 2011;30(10):1852–1859. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia R, Katz M. Estimation of health benefits accruing from a living wage ordinance. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(9):1398–1402. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.9.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole BL, Shimkhada R, Morgenstern H, Kominski G, Fielding JE, Wu S. Projected health impact of the Los Angeles City living wage ordinance. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(8):645–650. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minnesota Department of Health. White paper on income and health. 2014. Available at: http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/opa/2014incomeandhealth.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2015.

- 9.Human Impact Partners. Health impacts of raising California’s minimum wage. 2014. Available at: http://www.humanimpact.org/news/the-health-impacts-of-raising-the-minimum-wage. Accessed April 22, 2015.

- 10.Krisberg K. Raising minimum wage good for public health, not just wallets: advocates call for federal increase. Nations Health. 2015;45(2):1,12. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheiber N. What a $15 minimum wage would mean for your city. 2015. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/13/upshot/what-a-15-minimum-wage-would-mean-for-your-city.html?_r=2. Accessed October 2, 2015.

- 12.New York State Department of Labor. Hospitality industry wage order. Available at: http://www.labor.ny.gov/formsdocs/wp/CR146.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 13.McGeehan P. New York plans $15-an-hour minimum wage for fast food workers. 2015. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/23/nyregion/new-york-minimum-wage-fast-food-workers.html. Accessed January 5, 2016.

- 14.Addison JT, Blackburn ML, Cotti CD. Do minimum wages raise employment? Evidence from the U.S. retail-trade sector. Labour Econ. 2009;16(4):397–408. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allegretto SA, Dube A, Reich M. Do Minimum Wages Really Reduce Teen Employment? Accounting for Heterogeneity and Selectivity in State Panel Data. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley; 2011. IRLE Working Paper No. 166–08. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dube A, Lester TW, Reich M. Minimum Wage Effects Across State Borders: Estimates Using Contiguous Counties. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley; 2010. IRLE Working Paper No. 157–07. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neumark D, Wascher W. Employment Effects of Minimum and Subminimum Wages: Panel Data on State Minimum Wage Laws. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1992. NBER Working Paper No. 4570. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neumark D, Salas JMI, Wascher W. Revisiting the Minimum Wage-Employment Debate: Throwing Out the Baby With the Bathwater? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1992. NBER Working Paper No. 18681. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthews C. The winners and losers of New York’s new $15 fast-food minimum wage. 2015. Available at: http://fortune.com/2015/07/23/new-york-fast-food-minimum-wage-2. Accessed January 6, 2016.

- 20.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Population estimates. New York, NY: Bureau of Epidemiology Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–1789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruggles S, Genadek K, Goeken R, Grover J, Sobek M. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff (Milwood) 2002;21(2):60–76. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giannarelli L, Wheaton L, Morton J. How Much Could Policy Changes Reduce Poverty in New York City? Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirsch BT, Kaufman B, Zelenska T. Minimum wage channels of adjustment. Ind Relat. 2015;54(2):199–239. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zavodny M. The effect of the minimum wage on employment and hours. Labour Econ. 2000;7(6):729–750. [Google Scholar]

- 27.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Epiquery: NYC interactive health data system. 2014. Available at: http://nyc.gov/health/epiquery. Accessed February 26, 2016.

- 28.Brown AF, Ettner SL, Piette J et al. Socioeconomic position and health among persons with diabetes mellitus: a conceptual framework and review of the literature. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26:63–77. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, Williams DR, Mero RP, Chen J. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA. 1998;279(21):1703–1708. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain R. Whose burden is it anyway? Housing affordability in New York City by household characteristics. 2015. Available at: http://www.cbcny.org/sites/default/files/REPORT_RENTBURDEN_11122015_1.pdf. Accessed February 24, 2016.

- 31.Cheng ER, Kindig DA. Disparities in premature mortality between high- and low-income US counties. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dowd JB, Albright J, Raghunathan TE, Schoeni RF, Leclere F, Kaplan GA. Deeper and wider: income and mortality in the USA over 3 decades. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(1):183–188. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMichael AJ. Prisoners of the proximate: loosening the constraints on epidemiology in an age of change. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149(10):887–897. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(suppl 1):S186–S196. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woolf SH, Jones RM, Johnson RE, Phillips RL, Jr, Oliver MN, Vichare A. Avertable deaths associated with household income in Virginia. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):750–755. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panel on Addressing Priority Technical Issues for the Next Decade of the American Community Survey; Committee on National Statistics; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Realizing the Potential of the American Community Survey: Challenges, Tradeoffs, and Opportunities. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Department of City Planning, New York City. American Community Survey. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/census/popacs.shtml. Accessed August 17, 2015.