Abstract

The link between substance use and suicide is well established. However, little research analyzes how substance use is related to the method of suicide. This paper analyzes how specific drugs are associated with method of suicide, a critical topic because drug use bears on the etiology of suicide and may lead to policies aimed at deterring suicide. We use the COVDRS and logistic regression to examine postmortem presence of drugs among 3,389 hanging and firearm suicides in Colorado from 2004–2009. Net of demographic controls, we find that opiates are positively associated with firearms (OR: 1.92, 95% L: 1.27, 95% U: 2.86]) while antidepressants are positively associated with hanging (OR: 1.45, 95% L: 1.04, 95% U: 2.03). For cocaine and opiates, the association between drug use and violent method vary by educational attainment. Importantly, knowledge of the presence and type of specific drug is strongly associated with the method of suicide.

Keywords: drug use, suicide, suicide method, toxicology, National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS)

Introduction

Suicide prevention is a public health priority (Goldsmith, 2002; Rockett, 2010; Satcher, 1999). In the United States one of the major objectives of Healthy People 2020 (2010) is to reduce suicide rates by 10%. Despite increased attention, from 2000 to 2010 suicide rates increased by 15% (Rockett, et al., 2012), making suicide the tenth overall leading cause of death in the United States and the leading death from external causes, which include deaths due to violence and accidents (Hoyert & Xu, 2012; Rocket, et al., 2012). In 2011 an American died by suicide every 14 minutes—totaling over 38,000 suicides for the year (Hoyert & Xu, 2012). Beyond their tragic consequences for surviving friends and family members, suicides cost the U.S. economy an estimated $5 to $13 billion annually in lost earnings and medical costs (Yang & Lester, 2007).

Because of its public health importance, the causes, correlates, and consequences of suicide have been studied thoroughly (Durkheim, 1897; Eshun, 2003; Inskip et al.,1998; Qin, et al., 2000). One of the most consistent findings of this research is that substance use and abuse is one of the strongest predictors of suicide (Brent, 1995; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention [CDC], 2010; Kung et al., 2003; Sheehan et al., 2013). To date, little is known about the relationship between substance use and method of suicide. The relationship between substance use and suicide is a critical topic because drug use bears on the etiology of suicide and as such a greater understanding of the relationship between drug use and suicide potentially may lead to policies aimed at deterring suicide. For example, the causes of suicide may differ between someone prescribed antidepressants for long-term depression and someone self-medicating with opiates in light of chronic exposure to stressors, pain, or major stressful life events.

Using toxicology reports from suicide decedents in the state of Colorado, we examine the associations between the postmortem presence of licit and illicit drugs and method of suicide. Colorado has one of the highest age-adjusted suicide rates in the United States as well as some of the highest levels of drug use and thus serves as a useful and important context for this analysis (Murphy et al., 2013; Sheehan et al., 2013). We aim to explore how specific drugs are associated with the method of suicide net of social and demographic characteristics. Because of increasing differences in rates of suicide and drug use when stratified by level of educational attainment (Abel & Kruger, 2005; Miech, 2008), we also examine if level of educational attainment moderates drug use.

Background

Drug Use and Suicide

For decades research has shown that illegal drug use and abuse are associated with higher levels of suicide ideation, attempts, and, ultimately, deaths (Brent, 1995; Erinoff et al., 2004; Price et al., 2004). Indeed, the CDC (2010) rank drug and alcohol abuse second to major depression as the one of the strongest risk factors for suicidal behavior. However, illegal drug use is prone to misreports on surveys, and the relationship between drug use and suicide may be dramatically underestimated (Magura & Kang, 1996; Single et al., 1975). This underestimation may be more severe around the time of death: even if a respondent gives accurate responses on a survey, drug use in periods of elevated risk of suicide or around the critical period right before death may differ substantially from the individual’s typical consumption (Hawton, 2005). Additionally, third-party reports or investigations of the scene of death may underestimate the prevalence of drugs when compared to toxicology testing (Gruszecki et al., 2007). Research that focuses solely on current drug users or those with a drug addiction makes it difficult to estimate the prevalence of drug use among the general public near the time of death (Oyefeso et al.,1999). Our data include toxicology reports of drug use around the time of death for the population of suicide decedents in a U.S. state over the course of six years, allowing us to overcome misreporting of drug use on surveys.

While toxicology reports may be the ideal way to examine how drug use is associated with method of suicide, they are not problem-free. The third leading method of suicide is intentional self-poisonings (which comprises roughly 23% of all the suicides in Colorado during our study period), which, by definition, include drugs or substances in the system at the time of death. To avoid this tautology, we examine only “violent” firearm and hanging/strangulation/suffocation suicides (henceforth hanging) (Dumais, et al., 2005). These two methods comprise the vast majority of U.S. suicides, 71% of the Colorado sample, and 78% of the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) sample (Conner et al., 2014).

Substance abuse is strongly associated with suicide among adolescents (Erinoff, et al., 2004; Hallfors et al., 2004) and adults (Kung et al., 2003; Rossow et al., 1999). Yet a consideration of substance abuse as a broad topic may obscure the unique relationships between specific drug use and suicide risk. In fact, previous work demonstrates associations between specific drugs and suicide risk. For example, Kung and colleagues (2003) show that compared to adults who died by natural causes, males and females who use marijuana are 2.3 and 4.8 times as likely to commit suicide. Similarly, heroin users are estimated to be 14 times as likely to commit suicide compared to their non-drug-using peers (Darke and Ross, 2002). According to a meta-analysis, compared to the general public, opiate addicts face an elevated risk of suicide (Wilcox et al., 2004). Antidepressants are correlated with decreased suicide risk (Gibbons et al.,2005; Grunebaum et al., 2004), and there is mixed evidence about the increased risk of suicide among adolescents who are taking antidepressants (Brent, 2004; Gibbons et al., 2006; Gunnell and Ashby, 2004). Importantly, those on antidepressants are a highly select at-risk population (Isacsson et al., 1996; Sleath and Shih, 2003) who may seek antidepressants to prevent suicide.

Although research has linked substance use and abuse to suicide, less scholarship has focused on how drug use near the time of death is associated the method of suicide. The majority of this work analyzes acute alcohol use before death and finds that associations between alcohol use and method of suicide varies by demographic characteristics (Caetano et al., 2013; Conner et al., 2014; Kaplan et al., 2013). Conner et al. (2014) show that relatively young adults were more likely to use alcohol rather than poisoning before using a firearm and hanging. There are also distinct variations by race and ethnicity. For example, Asians are more likely to use alcohol in poisoning deaths whereas non-Hispanic blacks are least likely to use alcohol during hangings (Conner et al., 2014). The association between alcohol use and selected method of suicide also varies by gender (Kaplan et al., 2013). While the degree to which alcohol influences suicide method has been studied, drug use has not. Therefore, we exclusively analyze drugs rather than include alcohol.

Additionally, less research has analyzed drug use and suicide method, but there are notable exceptions. Sheehan et al. (2013) demonstrate that the postmortem presence of specific substances among victims of violent deaths helped differentiate between cases of suicide and homicide. Darke and Ross (2002) concluded that heroin users were surprisingly less likely to commit suicide by overdose than use other methods. Using suicide decedent data from New York City in 1985, Marzuk and colleagues (1992) determined that decedents who tested positive for cocaine were twice as likely to use firearms as any other method. However, rates of gun ownership vary by state and city, and the relationship may have changed over time. Rather than focusing specifically on the high-risk drug-using population or relying on survey reporting of drug use, we build on previous research by including all Colorado violent suicide decedents from 2004 to 2009, a much larger sample than those examined in previous investigations. As mentioned above, we only analyze hanging and firearm suicides due to them being considered violent (and classified as such see: Dumais et al., 2005), their high degree of lethality (Shenassa et al., 2003), and because they are the two most common methods of suicide in Colorado and the United States (Conner et al., 2014). In addition, we include all drug use in a multivariate rather than descriptive framework, thereby statistically controlling for socioeconomic and demographic factors. Finally, this may be the first study to examine how amphetamines are associated with methods of suicide.

Drug Use, Educational Attainment, and Suicide Method

It is also important to consider that the association between drug use and suicide method may vary by level of educational attainment. Previous research indicates that drug use varies significantly over time by educational attainment; those with lower levels of education are more likely to use and less likely to quit cocaine (Miech, 2008), abuse alcohol (Crum et al., 1993), and face worse health than more educated drug users (Galea & Vlahov, 2003). More attention has been paid to how lower levels of education are associated with the likelihood of committing suicide (Abel & Kruger 2005), socioeconomic disparities in suicide risk (Qin et al., 2003), and how these disparities in suicide rates have widened over time, particularly with the large-scale adoption of antidepressants (Clouston et al., 2013).

A much smaller body of work has examined whether education is associated with the method of suicide. For example, Shojaei et al. (2013) show that in Iran, hanging is the most frequent method of suicide among those with lower levels of education, but this is not the same for those with higher levels of education. However, we are aware of no research that analyzes how educational attainment is associated with suicide method in the United States. This is particularly relevant as the prevalence of suicide by hanging steadily increased in the United States from 2000 to 2010 (Baker et al., 2013). It is possible that the presence of substances may exacerbate the social patterning of suicide method. Said differently, the presence of drugs among those with low levels of education may be a strongly associated with suicide from hanging but have a negligible influence among those with higher levels of education. But it is also possible that the social factors among those with the greater social risks (e.g., those with relatively low levels of education) drive the comorbid risk of both drug use and suicide whereas in more stable environments drug use denotes a stronger indicator of suicide risk for individuals. Thus, it is possible that the association between the presence of drugs and the method of suicide will be significant for those with higher levels of education but negligible among those with lower levels of education. To date, however, it is unclear if the association between drug use prior to death and method of suicide varies by level of education. Indeed, other research has indicated that there are social patterns between substance use and suicide method. For example, Conner and associates (2014) show that blacks are less likely than whites to have used alcohol prior to hangings. Due to the social patterns found in other studies connecting drug use to suicide method and the strong connection between education and drug use, we hypothesize that substance use before death moderates the association between social factors such as educational attainment and method of suicide.

Aims

Our analysis has two major objectives. First, we document whether the use of specific drugs before death is associated with violent method of suicide. Hanging and firearms comprise 78% of all suicides in the NVDRS (Conner et al., 2014). While there are other methods of violent suicide (such as cutting, using a blunt object, or self-immolation), individually and collectively they denote a relatively small proportion of suicides. As a result, the different mechanisms of suicide have very small cell sizes that limit our ability to analyze them statistically. Due to the tautological nature of drug consumption before death and drug overdose, we also exclude intentional self-poisoning (which comprise just under 23% of the total suicides among those 18 and older in Colorado from 2004–2009) or other causes from the following analysis. We build on previous research by focusing exclusively on drug use and controlling for demographic characteristics. Second, we explore whether the association between drug use and method of suicide significantly varies by level of educational attainment.

Method

Data

The data come from the Colorado Violent Death Reporting System (COVDRS). Colorado is one of 32 states receiving federal funding to participate in the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) (http://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/NVDRS/index.html). The NVDRS, administered by the CDC, was established in 2002 to provide high quality data on all types of violent deaths including suicide, homicide, unintentional firearm fatalities, and deaths of undetermined intent (CDC, 2010; Paulozzi et al., 2004). The NVDRS complies, then codes data regarding the context of the death, toxicological reports, police reports, geographic location, and, crucial for this investigation, cause of death (Paulozzi et al., 2004). The cause of death codes are based on the tenth revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Problems, or ICD-10 codes (World Health Organization, 2007). Using data from 2004–2009, we exclude all homicide victims, individuals under age 18 (when education is often not completed), and suicide decedents who did not die from hanging or firearms. After these exclusions, our study population contains 3,389 decedents (71% of the adult Colorado suicide decedent population from 2004–2009), all of whom are used in every multivariate analysis. Colorado currently has the eleventh highest age-adjusted suicide rate in the United States and is situated in a cluster of mountain west states which, except for Alaska and Oregon, have the highest age-adjusted suicide rates in the country (Murphy et al., 2013).

Measures

We code our dependent variable, method of suicide, into two categories based on the ICD-10 cause of death codes: suicide due to firearms, coded “0” (ICD-10 codes X72–X74), and hanging/self-strangulation, coded “1” (ICD-10 code X70). We analyze hanging, which has a lower level of lethality, relative to firearms, the most common method (69.5% of our sample), due in part to its higher likelihood of fatality (Shenassa et al., 2003). All of our sample are decedents.

The five drugs we analyze are antidepressants, opiates, cocaine, marijuana, and amphetamines. Excluding alcohol, these drugs are the most commonly tested for and confirmed in violent death decedents as measured by toxicology reports (benzodiazepines were not tested for as often as the other drugs listed). Antidepressants serve as an important control and backdrop in which to compare the magnitude of other drugs. There is considerable within-drug heterogeneity for opiates and antidepressants. For example, there are numerous forms of antidepressants and opiates, ranging from heroin to prescription drugs. Due to the COVDRS data, we are unable to differentiate different types of antidepressants or opiates. Unlike for homicide decedents, toxicology tests are not legally required for suicides but may be conducted based on circumstances of the suicide (for example drugs found near the place of death) or characteristics of the decedent, as such not all decedents have toxicology reports, a limitation we address in the discussion. Therefore, we represent each drug with two dummy variables, the first indicating whether it was found to be present by a toxicology test (coded “1” if present, “0” if not) and the second indicating whether a test was done at all or whether the results were missing (coded “1” if a test was not conducted or the result was missing, “0” if not). The absence of the drug is the reference category.

The COVDRS also contains detailed information regarding the demographic characteristics of the decedents. We code men “1” and women “0.” Based on previous research (Conner et al., 2014), we divide age into the following set of four dummy variables: 18–24 (referent), 25–44, 45–64, and 65 and over. Due to small cell sizes, we operationalize race/ethnic group affiliation as a dummy variable where we code nonwhites as “1” and whites as “0.” We code marital status into the following set of five dummy variables: married (referent), never married, divorced, widowed, and missing marital status. Finally, we measure education as a dummy variable based on the number of years of education completed: less than high school/missing educational attainment (just over 1% of our sample are missing information regarding their educational attainment) (referent) and high school or greater.

Analytical Strategy

The first set of logistic regression models in Table 2 compares hanging versus firearm-related suicides. This model includes all of the drugs and controls for demographic factors to ascertain if the association between drug use and violent suicide method withstands controls for demographic factors and, equally important, other drug use. The next set of logistic models (Table 3) includes an interaction term between the presence of drugs and educational attainment to determine if the association of drug use significantly varies by educational attainment. We then use the postestimation values from the interaction and Stata’s margins command to graph the probabilities of drug use and education in predicting the method of suicide with all of the other controls held at their means. For a detailed overview of the calculation and interpretation of marginal effects, see Karaca-Mandic et al. (2012).

Table 2.

Logistic Model of Drug Use and Odds Ratios of Suicide Method in Suicide Decedents, Colorado, 2004–2009

| Hanging Versus Firearms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| OR | 95% L | 95% U | |

| Drug Presence | |||

| Opiates (Not Present) | |||

| Present | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.79 |

| Not Tested or Missing | 0.90 | 0.41 | 1.94 |

| Antidepressants (Not Present) | |||

| Present | 1.45 | 1.04 | 2.03 |

| Not Tested or Missing | 0.99 | 0.64 | 1.52 |

| Cocaine (Not Present) | |||

| Present | 1.30 | 0.90 | 1.88 |

| Not Tested or Missing | 0.99 | 0.47 | 2.11 |

| Amphetamines (Not Present) | |||

| Present | 1.05 | 0.71 | 1.56 |

| Not Tested or Missing | 0.70 | 0.38 | 1.28 |

| Marijuana (Not Present) | |||

| Present | 1.05 | 0.77 | 1.43 |

| Not Tested or Missing | 1.42 | 0.86 | 2.34 |

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Gender (Female) | |||

| Male | 0.56 | 0.45 | 0.69 |

| Age (18–24) | |||

| 25–44 | 0.94 | 0.74 | 1.19 |

| 44–64 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.69 |

| 65+ | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.37 |

| Race/Ethnicity (White) | |||

| Non-White | 1.78 | 1.45 | 2.18 |

| Educational Attainment (Less than high school) | |||

| High school or greater | 0.59 | 0.47 | 0.73 |

| Marital Status (Married) | |||

| Never Married | 1.37 | 1.12 | 1.68 |

| Divorced | 1.28 | 1.04 | 1.58 |

| Widowed/other category | 0.97 | 0.63 | 1.50 |

| Missing marital status | 1.68 | 0.61 | 4.66 |

Model also adjusts for missing values in drug results.

(Referent in parenthases)

Source: Colorado Violent Death Reporting System, 2004–2009

Table 3.

Logistic Model of Drug Use and Odds Ratios of Suicide Method in Suicide Decedents, Colorado, 2004–2009

| Hanging Versus Firearmsa | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Model 1: Opiates | Model 2: Antidepressants | Model 3: Cocaine | Model 4: Amphetamines | Model 5: Marijuana | |||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| b | 95% L | 95% U | b | 95% L | 95% U | b | 95% L | 95% U | b | 95% L | 95% U | b | 95% L | 95% U | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Drug | −1.96 | −3.23 | −0.70 | 0.08 | −1.02 | 1.18 | −0.39 | −1.10 | 0.31 | −0.57 | −1.34 | 0.19 | 0.40 | −0.31 | 1.10 |

| High school and above | −0.68 | −0.94 | −0.41 | −0.66 | −0.93 | −0.38 | −0.67 | −0.94 | −0.40 | −0.67 | −0.94 | −0.39 | −0.52 | −0.80 | −0.23 |

| Drug × high school and above | 1.58 | 0.24 | 2.92 | 0.28 | −0.88 | 1.43 | 0.84 | 0.03 | 1.64 | 0.82 | −0.06 | 1.70 | −0.47 | −1.25 | 0.31 |

Models control for gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, and missing drug values.

Findings

Table 1 displays drug presence among suicide decedents by method of violent suicide. Overall, the testing/missing rate is relatively consistent but varied slightly by method and drug. Decedents who test positive for antidepressants had slightly higher rates of hanging (6.4%) than firearms (5.1%). The opposite pattern is apparent for opiates, where decedents who used firearms (5.9%) have almost twice as high percentages found positive than those who used hanging (3.3%). For firearms, only 3.4% of decedents test positive for cocaine whereas for hanging the comparable number is 6.6%. Marijuana and amphetamines have higher levels of positive tests among those who used hanging than firearms. By method, the majority of violent suicide decedents died from self-inflicted gunshot wounds (69.5%), whereas 30.5% died from hanging. The percentage not tested is relatively large but the percentage missing is very small.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Suicide Decedents by Method of Suicide, Colorado, 2004–2009

| Firearm | Hanging/Strangulation | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Presence | |||

| Antidepressants | |||

| Percent Positive | 5.1% | 6.4% | 5.5% |

| Not Tested or Missing | 36.2% | 33.7% | 35.8% |

| Opiates | |||

| Percent Positive | 5.9% | 3.3% | 5.1% |

| Not Tested or Missing | 31.7% | 27.1% | 30.3% |

| Cocaine | |||

| Percent Positive | 3.4% | 6.6% | 4.4% |

| Not Tested or Missing | 31.7% | 31.9% | 30.4% |

| Marijuana | |||

| Percent Positive | 5.9% | 7.8% | 6.5% |

| Not Tested or Missing | 35.2% | 31.9% | 34.2% |

| Amphetamines | |||

| Percent Positive | 3.3% | 4.9% | 3.8% |

| Not Tested or Missing | 34.2% | 29.1% | 32.6% |

| Demographic Characteristics | |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 87.4% | 80.2% | 85.2% |

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | 11.0% | 20.2% | 13.8% |

| 25–44 | 31.7% | 46.5% | 36.2% |

| 44–64 | 39.0% | 27.8% | 35.6% |

| 65+ | 18.4% | 5.5% | 14.4% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Non-White | 12.1% | 25.5% | 16.2% |

| Educational Attainment | |||

| High School or Greater | 88.6% | 80.3% | 84.3% |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 40.5% | 31.0% | 37.6% |

| Never Married | 28.6% | 43.6% | 33.2% |

| Divorced | 23.0% | 21.6% | 22.6% |

| Widowed | 7.5% | 3.2% | 6.2% |

| Missing marital status | 0.4% | 0.7% | 0.5% |

| N | 2,355 | 1,034 | 3,389 |

Source: Colorado Violent Death Reporting System, 2004–2009

The multivariate logistic regression results in Table 2 indicate significant associations between postmortem presence of drugs and method of suicide. All of the models control for age, gender, race/ethnic group, educational attainment, marital status, and missing drug values. The results of Table 2 indicate that those who tested positive for opiates are significantly less likely to use hanging than firearms (OR: 0.52, 95% L: 0.35, 95% U: 0.79). On the other hand, those who test positive for antidepressants are significantly more likely to use hanging (OR: 1.45, 95% L: 1.04, 95% U: 2.03) than firearms. There is no significant association between cocaine, amphetamines, and marijuana and method of suicide. Overall, the model that includes the five drugs (−2LL = −3,832) is a significant improvement (LR = 22.07, df=10, p<.05) over the baseline model with only demographic characteristics (−2LL =3,854), statistically verifying our assumption that drug use is associated with the method of suicide above and beyond demographic characteristics.

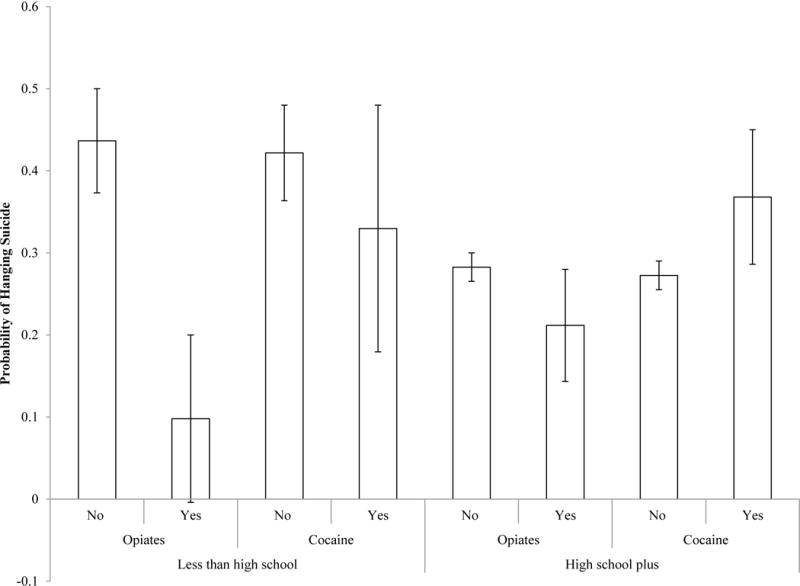

Table 3 uses interaction terms to investigate if any of the drug use associations vary significantly by educational attainment. We estimate each drug separately. We find significant interactions between the presence of drugs and education level for opiates and cocaine (p<.05) and some tentative evidence for amphetamines (p<.10). The association between opiates and suicide method (e.g., hanging compared to firearm) is significantly reduced for those who finished high school (OR: 0.68) compared to those who did not finish high school (OR: 0.14). These results also show that the association between cocaine and hanging is negative for those who did not finish high school (OR: 0.67) but positive for those who did finish high school (OR 1.55). While the direction is negative, the interaction is not significant at the .05 level for those who did not graduate high school. Similar to cocaine, the association of amphetamines operated in different directions based on educational attainment (at the 0.1 level). There are not significant differences at the .05 level found for amphetamines, marijuana, and antidepressants. These results indicate that decedents who had less than a high school education and were not on opiates or cocaine were more likely to hang but those who did test positive for those drugs were much more likely to use a firearm. Conversely, those with a high school education or more who tested positive for cocaine were more likely to use hanging than firearms. For ease of interpretation, Figure 1 graphically illustrates the interaction effects. In this figure it is clear that not being on opiates is strongly associated with hanging for those with less than a high school education, whereas the gap is much smaller for those with greater than a high school education. In sum, education is a significant moderator between drug use and method of violent suicide.

Figure 1.

Predicted Probability of Hanging Relative to Firearms by Presence of Drug and Educational Attainment.

Discussion

Whereas previous research has established drug abuse as a major risk factor for suicide, this study is one of the first to show that drug use before suicide is associated with the selected method of violent suicide and that these patterns vary by level of educational attainment. We find that the opiate use before death is associated with using firearms compared to hanging whereas the use of antidepressants is associated with hanging compared to firearms. The model that includes the drug use covariates explains significantly more of the variance than a model that includes only demographic characteristics. In addition, we explored models where we summed the total number of drugs the decedent tested positive for; the results (not shown) were not significant. In other words specific drugs rather than the number of drugs were associated with the selected method. We also find significant differences in the association between the drugs in predicting method of suicide by educational attainment. For those with less than a high school degree, opiates are strongly associated with using firearms compared to hanging, but the presence of opiates does little to differentiate the method of suicide among those with a high school degree or higher. In contrast, the presence of cocaine significantly increases the likelihood of hanging among those with higher levels of education but is not linked to method of suicide for those with less than a high school education. Compared to previous research that collapsed firearms and hanging into a “violent” category (Dumais et al., 2005), our results suggest that firearms and hanging differ based on drug use and demographic factors.

While our work comports with previous research which illustrates that acute alcohol use is associated with method of suicide and that these relationships vary by demographic characteristics (Caetano et al., 2013; Conner et al., 2014; Kaplan et al., 2013), it remains unclear why there are associations between drug use and selected method of suicide. While we did not include adolescents in our study population, Goldston’s (2004) excellent overview regarding substance use and suicide among adolescents offers some potential explanations of why certain drugs used before death may be associated with certain methods. Those who use drugs and commit suicide may experience tremendous stress, and the substance use may be taken as a means of escape. Similarly, drug use and suicide do not occur alone as they are also correlated with other risk behaviors, for example weapon ownership. Furthermore, substance use may increase cogitations and diminish impulse control, potentially making suicide more likely. Future research must analyze why these drugs are associated with the specific methods and if these associations are apparent in other contexts. While speculative, those who hang themselves may face longer term depression (thus the antidepressants) whereas those who shoot themselves may do so more impulsively (thus the opiates). Of course, this may not be the case for those who have suffered from long-term chronic pain that they treat with prescription pain killers. Clearly, more research is needed regarding the strong connection between drug use and suicide.

Drug use may not necessarily cause someone to select a specific method. Drug use may also precipitate a period of elevated risk for suicide or be taken in response to a critical situation (Hawton, 2005). Risk periods are relatively brief and once they are overcome, the likelihood of suicide drops (Hawton, 2005); therefore, a reduction in access to drugs during these critical times may reduce suicides, particularly if these drugs reduce inhibition. Drug use has been documented as a cause and consequence of impulsive behavior (de Wit, 2009). Those who self-select into using similar drugs in the critical periods immediately before suicide may also be more prone to using specific methods, which would make targeted interventions focusing on these users more effective. Because of the association between drug use and method of suicide, limiting drug use may lead to fewer suicides. In particular, gun owners with low levels of education who use opiates may be considered worthy of means restriction counseling to reduce their suicide rates (Bryan et al., 2011). Additionally, reducing drug use may have differential impacts on suicide rates by level of educational attainment (Conner et al., 2014).

There are substantial and important distinctions between our analyses of decedents and analyses of the risk of death, including differences with the questions that can be addressed, the data that are analyzed, and the results that can be drawn. A major strength of this paper is the detailed data set that provides toxicology reports of drug presence at the time of death over the course of a six-year period among all suicide decedents in Colorado. A separate research question could instead examine the risk of death by, say, linking survey or census records to death records, which would enable estimates of the association between drug use at the time of the survey and subsequent death. Such research would require expensive and logistically complicated collection of toxicology reports at the time of the survey. But drug use at the time of the survey may not reflect regular use, may be biased downward (because heavy drug users may be missed by surveys and many interviewees may curtail their drug use before agreeing to drug testing), and may differ radically from drug use at the time of death (which might be atypical). Surveys can also collect self-reported drug use information, but such data will differ substantially from drug use at the time of death. Thus, the analyses of rich and detail decedent information provides advantages absent in other types of data collection.

Limitations

We identify four limitations to this investigation. First, decedents who use violent methods differ from those who use less violent methods; for example, they are more likely to be male (Denning et al., 2000). Second, toxicologists did not test every suicide decedent for every drug used. However, in ancillary analyses, controlling for demographic factors, we found no significant difference in testing between methods, giving us confidence that our results are not driven by selective testing between methods. Thus we find no evidence for a consistent bias in testing between methods. Still, the missing data may mean we are underestimating the prevalence levels. For example, other research has asserted that in some studies over 60% of all suicide decedents are not tested for alcohol (Chepitel et al., 2004). One potential way to overcome these underestimates would be mandatory statewide testing for all suicides; however, this dataset may include the most complete set of drug tests of decedents extant, especially if potential budget cuts further restrict funds in state coroner systems. Third, firearms are slightly more lethal than hanging. Shenassa and associates (2013) found that firearms are about 4% more lethal than hanging among adults who were hospitalized for their suicide attempt. Other research corroborates that firearms are more lethal than hanging but notes that lethality differs by the type of firearm and the location of the gunshot wound (Rhyne et al. 1995). Because the higher lethality of firearms could lead to some issues with selection (Hernan et al., 2004), we ran auxiliary analyses to examine any potential bias. If we assume that the probability of death for those who were on antidepressants and used hanging is 0.9 (the overall estimate of the lethality of hanging produced by Rhyne and colleagues [1995] and more conservative than Shenassa et al. 2013), the probability of a successful suicide for those without antidepressants who use firearms would have to be as low as 0.62 for us to observe an odds ratio of 1.45 (which we observed for antidepressants). Rhyne et al. (1995) and Shenassa et al. (2013) both estimate the probability of mortality when using a firearm is above 90%, regardless of type of firearm or location of wound. Thus, the selection of methods could influence but is unlikely to drive our results. Finally, testing criteria and cutoffs may differ from state to state and country to country, which will affect the generalizability of our results (Kuhns et al., 2009).

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, this is one of the first papers to show that drug use at the time of death is a significantly association with the selected suicide method among the two leading methods. This study has illustrated that it is not only critical to examine how drug use is associated with method of suicide but how suicide method can even more accurately be understood with an interaction between suicide method and educational attainment. The interaction between education and the presence of drugs reinforces the notion that suicide is characterized with both individual and environmental risks. Because of our use of toxicological reports from an entire state, we are able to overcome data limitations of previous research that has analyzed the associations between self-reports of drug use and suicide. Previous research illustrates the importance of contextual factors, availability of fatal method, demographic factors, and personality traits in determining the method of suicide. To further elucidate the etiology of suicide, we suggest that future researchers investigate how contextual circumstances and drug use, and personal impulsivity, interact with the selected method and how these situations and drug use interact with demographic factors. The NVDRS would allow such analyses. A greater focus on the method, drug use, and demographic factors relating to suicide could allow policymakers to develop more specific policies to mitigate America’s distressingly high suicide rates. Specifically, policies that take into account the complex interactions among drug use, educational attainment, and method may be best equipped to slow or even reverse the increase in suicide rates.

Acknowledgments

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: We thank the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD-funded University of Colorado Population Center (Grant R24 HD066613) and the University of Texas Population Research Center (Grant R24 HD42849) for administrative and computing support, and the NICHD Ruth L. Kirschstien National Research Service Award (T32 HD007081-35) for training support.

Contributor Information

Connor M. Sheehan, University of Texas at Austin

Richard G. Rogers, University of Colorado Boulder

Jason D. Boardman, University of Colorado Boulder

References

- Abe K, Mertz KJ, Powell KE, Hanzlick RL. Characteristics of black and white suicide decedents in Fulton County, Georgia, 1988–2002. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1794–1798. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.082131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel E, Kruger M. Educational attainment and suicide rates in the United States. Psychology Reports. 2005;97:25–28. doi: 10.2466/pr0.97.1.25-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrams RC, Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC. Preference for fall from height as a method of suicide by elderly residents of New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1000–1002. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.037861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajdacic-Gross V, Weiss MG, Ring M, Hepp U, Bopp M, Gutzwiller F, Rössler W. Methods of suicide: International suicide patterns derived from the WHO mortality database. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86:726–732. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahraini NH, Gutierrez PM, Harwood JE, Huggins JA, Hedegaard H, Chase M, Brenner LA. The Colorado Violent Death Reporting System (COVDRS): Validity and utility of the veteran status variable. Public Health Reports. 2012;127:304–309. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker S, Guoqing H, Wilcox H, Baker T. Increase in suicides by hanging/suffication in the U.S. American Journal of Preventitive Medicine. 2013;44:146–149. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA. Risk factors for adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior: Mental and substance abuse disorders, family environmental factors, and life stress. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1995;25:52–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA. Antidepressants and pediatric depression: the risk of doing nothing. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:1598–1601. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Stone SL, Rudd MD. A practical, evidence-based approach for means-restriction counseling with suicidal patients. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2011;42:339. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Kaplan MS, Huguet N, McFarland BH, Conner K, Giesbrecht N, Nolte KB. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide among United States ethnic/racial groups: Findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:839–846. doi: 10.1111/acer.12038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] Suicides Due to Alcohol and/or Drug Overdose: A Data Brief from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Atlanta, GA: Center of Disease Control; 2010. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/NVDRS_Data_Brief-a.pdf (Accessed on 9/16/13) [Google Scholar]

- Cherpitel C, Borges G, Wilcox H. Acute alcohol use and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:18S–28S. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000127411.61634.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouston S, Rubin M, Colen C, Link B. The fundamental causes of social inequalities in sucide. Presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of American; New Orleans. April 11–13, 2013.2013. [Google Scholar]

- Conner KR, Huguet N, Caetano R, Giesbrecht N, McFarland BH, Nolte KB, Kaplan MS. Acute use of alcohol and methods of suicide in a US national sample. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:171–178. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Helzer JE, Anthony JC. Level of education and alcohol abuse and dependence in adulthood: A further inquiry. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83:830–837. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Ross J. Suicide among heroin users: Rates, risk factors and methods. Addiction. 2002;97:1383–1394. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Leo D, Dwyer J, Firman D, Neulinger K. Trends in hanging and firearm suicide rates in Australia: Substitution of method? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33:151–164. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.2.151.22775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denning DG, Conwell Y, King D, Cox C. Method choice, intent, and gender in completed suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2000;30:282–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: A review of underlying processes. Addiction Biology. 2009;14:22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumais A, Lesage AD, Lalovic A, Séguin M, Tousignant M, Chawky N, Turecki G. Is violent method of suicide a behavioral marker of lifetime aggression? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1375–1378. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim E. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Free Press; 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston M. Patterns and problems of deliberate self-poisoning in the developing world. Quarterly Journal of Medicine. 2000;93:715–731. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.11.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erinoff L, Compton WM, Volkow ND. Drug abuse and suicidal behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:S1–S2. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshun S. Sociocultural determinants of suicide ideation: A comparison between American and Ghanaian college samples. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2003;33:165–171. doi: 10.1521/suli.33.2.165.22779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Vlahov D. Social determinants and the health of drug users: Socioeconomic status, homelessness, and incarceration. Public Health Reports. 2002;117:S135–S145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ. The relationship between antidepressant medication use and rate of suicide. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:165–172. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RD, Hur K, Bhaumik DK, Mann JJ. The relationship between antidepressant prescription rates and rate of early adolescent suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1898–1904. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith SK. Reducing suicide: A national imperative. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldston DB. Conceptual issues in understanding the relationship between suicidal behavior and substance use during adolescence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:S79–S91. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunebaum MF, Ellis SP, Li S, Oquendo MA, Mann JJ. Antidepressants and suicide risk in the United States, 1985–1999. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:1456–1462. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruszecki A, Booth J, Davis G. The predictive value of history and scene investigation for toxicology results in a medical examiner population. American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 2007;28:103–106. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0b013e318061956d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D, Ashby D. Antidepressants and suicide: What is the balance of benefit and harm. British Medical Journal. 2004;329:34–38. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7456.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, Iritani B. Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K. Restriction of access to methods of suicide as a means of suicide prevention. In: Hawton K, editor. Prevention and treatment of suicidal behaviour from science to practice. Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- Healthy People 2020. Mental Health Status Improvement Objectives. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology. 2004;15:615–625. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000135174.63482.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyert DL, Xu J. Deaths: Preliminary data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2012;61:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inskip HM, Harris EC, Barraclough B. Lifetime risk of suicide for affective disorder, alcoholism and schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;172:35–37. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isacsson G, Bergman U, Rich CL. Epidemiological data suggest antidepressants reduce suicide risk among depressives. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1996;41:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, McFarland BH, Huguet N, Conner K, Caetano R, Giesbrecht N, Nolte KB. Acute alcohol intoxication and suicide: A gender-stratified analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System. Injury Prevention. 2013;19:38–43. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaca-Mandic P, Norton E, Dowd B. Interaction terms in nonlinear models. Health Services Research. 2012;47:255–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns JB, Wilson DB, Maguire ER, Ainsworth SA, Clodfelter TA. A meta-analysis of marijuana, cocaine and opiate toxicology study findings among homicide victims. Addiction. 2009;104:1122–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung HC, Pearson JL, Liu X. Risk factors for male and female suicide decedents ages 15–64 in the United States. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2003;38:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s00127-003-0656-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin KA, Leyland AH. Urban/rural inequalities in suicide in Scotland, 1981–1999. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:2877–2890. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Kang SY. Validity of self-reported drug use in high risk populations: A meta-analytical review. Substance Use & Misuse. 1996;31:1131–1153. doi: 10.3109/10826089609063969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC, Stajic M. Prevalence of cocaine use among residents of New York City who committed suicide during a one-year period. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:371–375. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miech R. The formation of a socioeconomic health disparity: The case of cocaine use during the 1980s and 1990s. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49:352–366. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S, Xu J, Kochanek K. Deaths: Final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2013;61:1–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyefeso A, Ghodse H, Clancy C, Corkery JM. Suicide among drug addicts in the UK. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;175:277–282. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulozzi L, Mercy J, Frazier L, Annest J. CDC’s national violent death reporting system: Background and methodology. Injury Prevention. 2004;10:47–52. doi: 10.1136/ip.2003.003434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RK, Risk NK, Haden AH, Lewis CE, Spitznagel EL. Post-traumatic stress disorder, drug dependence, and suicidality among male Vietnam veterans with a history of heavy drug use. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:S31–S43. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB. Suicide risk in relation to socioeconomic, demographic, psychiatric, and familial factors: A national register–based study of all suicides in Denmark, 1981–1997. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:765–772. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin P, Mortenson PBO, Agerbo E, Westergard-Nielsen N, Eriksson T. Gender differences in risk factors for suicide in Denmark. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;177:546–550. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhyne CE, Templer DI, Brown LG, Peters NB. Dimensions of suicide: perceptions of lethality, time, and agony. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 1995;25:373–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett IRH. Counting suicides and making suicide count as a public health problem. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention. 2010;31:227–230. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett IRH, Regier MD, Kapusta ND, Coben JH, Miller TR, Hanzlick RL, Kleinig J. Leading causes of unintentional and intentional injury mortality: United States, 2000–2009. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:e84–e92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossow I, Romelsjo A, Leifman H. Alcohol abuse and suicidal behaviour in young and middle aged men: Differentiating between attempted and completed suicide. Addiction. 1999;94:1199–1207. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.948119910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satcher D. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Suicide. US Public Health Service; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan CM, Rogers RG, Williams GW, Boardman JD. Gender differences in the presence of drugs in violent deaths. Addiction. 2013;108:547–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04098.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenassa E, Catlin S, Buka S. Lethality of firearms relative to other suicide methods: A population based study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57:120–124. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.2.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shojaei A, Moradi S, Aladdini F, Khodadoost M, Barzegar A, Khademi A. Association between suicide method, and gender, age, and education level in Iran over 2006–2010. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry. 2014;6:18–22. doi: 10.1111/appy.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Single E, Kandel D, Johnson B. The reliability and validity of drug use responses in a large scale longitudianl survey. Journal of Drug Issues. 1975;5:426–443. [Google Scholar]

- Sleath B, Shih YC. Sociological influences on antidepressant prescribing. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:1335–1344. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox HC, Conner KR, Caine ED. Association of alcohol and drug use disorders and completed suicide: An empirical review of cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:S11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. Geneva: WHO; 2007. Tenth Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Lester D. Recalculating the economic cost of suicide. Death Studies. 2007;31:351–361. doi: 10.1080/07481180601187209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]