Abstract

The Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF) is a conceptual model that supports coalition-driven efforts to address underage drinking and related consequences. Although the SPF has been promoted by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s Center for Substance Abuse Prevention and implemented in multiple U.S. states and territories, there is limited research on the SPF’s effectiveness on improving targeted outcomes and associated influencing factors. The present quasi-experimental study examines the effects of SPF implementation on binge drinking and enforcement of existing underage drinking laws as an influencing factor. The intervention group encompassed 11 school districts that were implementing the SPF with local prevention coalitions across eight Kansas communities. The comparison group consisted of 14 school districts that were matched based on demographic variables. The intervention districts collectively facilitated 137 community-level changes, including new or modified programs, policies, and practices. SPF implementation supported significant improvements in binge drinking and enforcement outcomes over time (p < .001), although there were no significant differences in improvements between the intervention and matched comparison groups (p > .05). Overall, the findings provide a basis for guiding future research and community-based prevention practice in implementing and evaluating the SPF.

Keywords: Strategic Prevention Framework, binge drinking, enforcement, youth and adolescents, risk and protective factors, community intervention

Although state and national efforts to reduce underage drinking have been prominent in the last few decades, alcohol remains one of the most commonly abused substances among youth, often associated with later drug use (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). Binge drinking, defined as consuming more than five alcoholic drinks in one occasion, is a common type of alcohol consumption affecting as many as 20% of youth ages 12 to 17 in the United States (CDC, 2011; Eaton et al., 2012). Studies have consistently shown that youth who engage in binge drinking are at an increased risk for other unhealthy behaviors and conditions such as risky sexual behavior (Miller, Naimi, Brewer, & Jones, 2007), acquiring sexually transmitted infections (Shafer et al., 1993), using illicit drugs (Kirby & Barry, 2012), and engaging in violence (Blitstein, Murray, Lytle, Birnbaum, & Perry, 2005).

One of the key influencing factors for binge drinking among adolescents is the enforcement of existing laws and policies. Enforcing underage drinking laws have the potential to be a cost-effective method for reducing alcohol consumption among youth and can play a critical role in supporting community-based efforts to address the issue (Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2011). Early research found that poor enforcement was correlated with higher rates of alcohol consumption (Wagenaar & Wolfson, 1995); conversely, later studies have concluded that interventions that integrated enforcement as a major component yielded promising effects (Holder et al., 2000; Schelleman-Offermans, Knibbe, Kuntsche, & Casswell, 2012). Despite the evidence that prioritizing enforcement in interventions can support improved underage drinking outcomes, there remains limited research on its contribution to underage drinking, and adolescent binge drinking more specifically.

Community-level Intervention Strategies for Enforcement

Within the past couple of decades, comprehensive community interventions have become a commonly promoted approach used in prevention research to address community-level problems such as violence, obesity and underage drinking. It has been suggested that implementing environmental changes, including the enforcement of policy, may be more likely to reduce underage drinking than single program interventions targeting only individual-level behavior change (e.g., alcohol education programs) (Paek & Hove, 2012). Interventions using such approaches often consider multiple ecological levels as it relates to enforcement, policies, and practices to address outcomes such as binge drinking among youth (Schelleman-Offermans et al., 2012). The literature suggests that implementing interventions that target multiple systems of influence is useful in promoting multisectoral engagement in the implementation and sustainability of environmental changes, which makes it more likely that reductions in alcohol consumption will be maintained over time (Giesbrecht & Greenfield, 2003; Paek & Hove, 2012; Williams et al., 2006).

Comprehensive community-based interventions often promote the implementation of environmental strategies, including the adoption of laws and regulations, to reduce alcohol consumption among youth (Giesbrecht & Greenfield, 2003). The United States Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), through its Healthy People 2020 initiative, also recommended a number of interventions to address alcohol consumption, including increasing alcohol beverage taxes (Elder et al., 2010) and limiting the days and hours that alcohol can be sold (Middleton et al., 2010). Overall, the aforementioned strategies highlight the more widespread adoption of community-level interventions that support environmental strategies as approaches to address underage drinking in research and practice.

Strategic Prevention Framework

The Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF) is a five-phase model that supports the use of comprehensive or multi-component community-based approaches (Eddy et al., 2012; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011). The SPF phases include assessment, capacity, planning, implementation, and evaluation, which work in concert to promote cultural competency and sustainability of community-based prevention efforts. Because the phases are both iterative and interactive (e.g., community organizations continually engage in capacity building efforts across all phases), the SPF provides a conceptual foundation for developing and implementing evidence-based prevention strategies. One key aspect of the SPF is that it promotes coalitions’ efforts to facilitate both programs and environmental changes, with attention to improved outcomes.

Studies suggest that implementing the SPF may yield reductions in adolescent substance abuse. In a cross-site evaluation, Florin and colleagues (2012) found that as part of a comprehensive community intervention, policy, media, and enforcement related prevention efforts were associated with improvements in their respective outcomes. Another study found that implementing the SPF resulted in decreases in students’ past 30-day alcohol use, binge drinking, and ease of obtaining alcohol over time (Eddy et al., 2012). Although the Eddy et al. study showed improvements in underage-drinking related outcomes, similar prevention outcome findings in other communities have not been published in the peer-reviewed literature. Rather, several studies have been published on enhancing coalition capacity and infrastructure to support SPF implementation (e.g., Anderson-Carpenter, Watson-Thompson, Jones, & Chaney, 2014; Florin et al., 2012; Orwin, Stein-Seroussi, Edwards, Landy, & Flewelling, 2014). Although studies have described process measures used in SPF implementation (e.g., Florin et al., 2012; Piper et al., 2012), few published studies have examined its effects on changes in substance use outcomes and related influencing factors. Thus, the purpose of this multi-site study is to examine the effects of implementing the SPF on binge drinking and enforcement of existing underage drinking laws across multiple school districts. The hypotheses for the present study are that: (1) SPF implementation will support coalition- facilitated implementation of environmental changes in intervention communities, (2) the intervention will yield significant improvements in binge drinking and enforcement outcomes over time, and (3) students in the intervention school districts will show significantly greater improvements in binge drinking and enforcement outcomes than students in the comparison districts. This study was part of a larger study approved by a university Institutional Review Board.

Method

Participating Coalitions and Communities

Eight coalitions funded through the Kansas SPF State Incentive Grant (SPF-SIG) participated in the present quasi-experimental study. The coalitions sought to implement programs, policies, and practices to bring about community-level change and improvement in targeted outcomes. Coalition volunteers included representatives from multiple sectors, such as business, local government, youth-serving organizations, media, law enforcement, and schools.

Intervention districts

The study included 11 school districts across eight communities (larger communities encompassed multiple school districts), which were geographically distributed across Kansas. Across the intervention districts, the demographic characteristics were representative of the overall state, and approximately 26% of the residents were younger than 18 years. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the intervention and matched comparison districts. To ensure a representative sample of students from the district were included, intervention school districts were required to have KCTC student survey data with participation rates of 50% or higher for at least two years prior to the intervention period and throughout the duration of the study. Over the six-year study, data from 24,357 students in intervention districts were collected.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Intervention and Matched Comparison Districts

| District characteristic | Intervention Districts |

Comparison Districts |

|---|---|---|

| District enrollment size at time of matching procedure |

31,611 | 28,150 |

| Geographic designation | ||

| Urban | 27% | 36% |

| Rural | 73% | 64% |

| Student characteristics | ||

| Past 30-day alcohol use | 28% | 27% |

| Free/reduced lunch | 37% | 35% |

| White, not Hispanic/Latino | 84% | 89% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6% | 4% |

Comparison districts

To examine comparisons for binge drinking and enforcement outcomes, the matching process for a comparison youth sample occurred at the school district level using similar procedures from sampling of the intervention districts. If an intervention district could not be matched to a single comparison district, a cluster of comparison districts was used based on characteristics of the student population. When clustered comparison districts were used, the data were aggregated and analyzed across school districts in the cluster group. School districts were excluded if less than 50% of students in grades 6, 8, 10, and 12 participated in the KCTC Survey.

Of the eligible school districts, comparisons were matched according to the following variables: (a) the 30-day alcohol consumption rate reported by students in the 2007 KCTC survey, (b) the 2007 district enrollment size, (c) the 2007 KCTC student-reported binge-drinking rate, (d) the 2007 percentage of KCTC participants who identified as White not Hispanic/Latino, (e) the 2007 percentage of KCTC participants who identified as Hispanic/Latino, (f) the 2007 percentage of students in the school district receiving free or reduced lunch, and (g) the geographical designation as reported by the Kansas Department of Health and Environment. Data from 28,150 students in comparison districts were collected.

SPF Intervention Components and Elements

Within and across each of the five phases of the SPF model, coalitions received training and technical support from the state-level prevention support system, which included the Kansas SPF-SIG director, state-based training and technical assistance providers, and a team of evaluators for the initiative. Approximately two months prior to implementing each SPF phase, coalition representatives received training from the Kansas state prevention team. As part of the training, the state prevention team provided the coalitions with guidelines to support their efforts.

The coalitions planned and then implemented the SPF phases in collaboration with diverse partners across multiple local community sectors. To evidence implementation and completion of each phase, the coalitions submitted developed materials (e.g., community assessments, strategic and action plans) that were reviewed and approved by the Kansas SPF- SIG state prevention team based on the state and federally established SPF guidelines.

Assessment

Each coalition used epidemiological data to understand the scope of underage drinking within their communities. The coalitions conducted in-depth analyses of underage drinking to identify the root causes and factors contributing to underage drinking locally (Altman, 1995). The community assessments centered around four themes related to underage drinking in the context of the SPF: (1) naming and defining the problem behavior; (2) investigating both how and where underage drinking occurred; (3) analyzing the root causes of the problem behavior; and (4) examining the factors influencing and contributing to the prevalence of underage drinking.

Capacity

The participating coalitions engaged in capacity-building efforts to enhance their readiness and capabilities to address underage drinking. In this phase, the participating coalitions engaged in cross-site collaboration, including individual and group-based training and technical assistance, to support implementation of evidence-based strategies. The Kansas Social and Rehabilitation Services (SRS) encouraged cross-sector representatives from the coalitions to collaborate as communities of practice to address underage drinking (Anderson-Carpenter, Watson-Thompson, Jones, & Chaney, 2014).

Planning

Based on the needs assessments, the coalitions developed logic models to assist in further analyzing and identifying appropriate interventions to address influencing factors of underage drinking at the local level. Using backward-logic intervention mapping (Kirby, 2004; Work Group for Community Health and Development, 2015), the logic models specified target behaviors (i.e., binge drinking), influencing factors of underage drinking (i.e., enforcement), and culturally appropriate evidence-based strategies to occasion widespread behavior change and improvement in underage drinking outcomes.

Based on the assessment findings, coalitions developed objective statements focused on measurable changes to be attained in enforcement and binge drinking outcomes. The coalitions selected evidence-based prevention strategies to address enforcement as a targeted influencing factor of underage drinking, which were then reviewed and approved by the state prevention team. Evidence-based strategies were required to have empirical support in peer-reviewed literature or be recognized as a best practice by organizations that conduct and disseminate prevention research (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration). After receiving approval for the objective statements, the coalitions developed action plans to guide strategy implementation. The action plans identified specific community changes (i.e., new or modified programs, policies, and practices) that the coalition sought to facilitate with respect to its stated objectives.

Implementation

From January 2009 through June 2012, the coalitions implemented between one and two environmental strategies (i.e., policies and practices) related to enforcement based on their action plans (see Table 2 for a list of implemented environmental strategies). Collectively, the coalitions implemented nine environmental strategies that prioritized enforcement as an influencing factor of binge drinking. During the intervention phase, the coalitions actively engaged multiple community sectors to take action in supporting strategy implementation. For example, coalition representatives worked with district attorneys, local judges, law enforcement, and policy makers to increase the penalty for providing alcohol to youth. Additionally, the coalitions partnered with local law enforcement personnel to coordinate the implementation of Saturation Patrols. The Saturation Patrols were designed to increase enforcement in community areas where binge drinking was more problematic. Through technical assistance, coalitions adapted strategy components as needed to fit the local cultural context. Coalitions also participated in training and technical assistance to aid in sustaining prevention efforts. The partner coalitions developed discrete steps to guide their sustainability activities, which were then integrated into the action plans.

Table 2.

Distribution of Implemented Environmental Strategies by Eight Community Coalitions with Descriptions

| Implemented Strategy | Strategy Description/Purpose | % Coalitions Implementing Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Collaboration, Advocacy, and Education with Law Enforcement |

Enhance advocacy for legislation to strengthen existing underage drinking policies |

12.5% |

| Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol |

Community organizing program to reduce alcohol access by changing policies and practices |

50.0% |

| Collaboration with Schools | Collaborative effort between coalitions, schools, and law enforcement to strengthen underage drinking prevention efforts |

12.5% |

| Law Enforcement Visibility | Increase local law enforcement presence in the community | 12.5% |

| Letters to Parents: Social Access | Designed to educate parents on the dangers and consequences of providing alcohol to youth |

12.5% |

| Responsible Beverage Service |

Training and certification program to educate retailers on state laws for providing alcohol to minors |

12.5% |

| Retailer Compliance Checks | Ensure retailers comply with laws against selling alcohol to youth | 12.5% |

| Saturation Patrols | Identify and reduce high-intensity substance use areas in the community | 25.0% |

| Sobriety Checkpoints | Law enforcement-led strategy to reduce driving under the influence of substances |

12.5% |

Evaluation

From January 2009 through June 2012, the evaluation team guided the coalitions in quarterly data review meetings, which consisted of a guided interview and in-depth data analysis of either process or outcome data. The sessions supported coalition representatives in reflecting on how the implementation of evidence-based strategies supported improvements in prioritized outcomes related to underage drinking. The data review sessions also permitted coalitions to make necessary adjustments to enhance implementation of prevention strategies.

Community Changes Measure

To better understand the implementation of environmental strategies within and across communities, changes in community and system practices and policies were examined. To be scored as a community change in this study, the documented activity or event was required to: (a) be an instance of a new policy or modified practice (e.g., a policy is adopted in a community by local government, a practice or way of doing things is changed in a sector), which was (b) facilitated by the coalition, and (c) related to underage drinking objectives (i.e., enforcement, binge drinking). Examples of community changes included the implementation of increased penalties for hosting parties at which youth can access alcohol (policy change), and reducing vendor sales of alcohol in public activities such as a fair (practice change). Community changes were documented by coalition representatives in a web-based data collection platform. For the present study, community changes were analyzed by frequency and type (i.e., policy or practice) to examine how coalition-facilitated changes in the community contributed to improvements in underage drinking outcomes.

Interobserver agreement was calculated for 50% of documented coalition activities based on independent scoring by two researchers. Agreement for community changes was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the sum of agreements plus disagreements, and then multiplying the quotient by 100%. For this study, acceptable agreement was established at 80% or above. The mean interobserver agreement across intervention districts was 92.3% (Range: 89.1% - 94.6%).

Dependent Measures

Data collection process

Underage drinking measures included self-reported behaviors obtained from the Kansas Communities That Care (KCTC) survey (http://kctcdata.org). To ensure students felt free to report honestly, the survey was voluntary and anonymous with results only reported at an aggregate level. No personally identifiable information was collected. The KCTC, based on the work developed by the Social Development and Research Group (Arthur, Hawkins, Pollard, Catalano, & Baglioni, 2002), is a structured set of validated indicators measuring risk and protective factors associated with youth substance use and delinquency. Currently, funded by the Kansas Department for Aging and Disability Services, the KCTC survey is offered annually, free of charge, to all Kansas students in 6th, 8th, 10th, and 12th grades.

Using a census approach, all Kansas school districts are actively recruited to participate. Average participation rates for the intervention and matched districts across the six years of the study ranged from 63% to 91% of all eligible students, with on average a 70% participation rate statewide. School districts had the option of administering the KCTC as an online or a paper-and pencil-questionnaire. The student surveys included a serial number, but all data were de- identified. The survey findings were analyzed and reported aggregately across students, demographic characteristics, and behavioral outcome measures.

Outcome measures

The intervention coalitions prioritized both binge drinking and enforcement as influencing factor and outcome measures based on KCTC survey data of youth in grades 6, 8, 10 and 12. Binge drinking was defined as consuming five or more alcoholic drinks in a row and measured within a two-week period. The survey assessed the self-reported prevalence of problem behaviors across multiple ecological domains (e.g., individual, family, school, community). In the current study, binge drinking was assessed in terms of the level of use in the past two weeks (none, 1 time, 2 times, 3-5 times, 6-9 times, 10 or more times). Binge drinking was used to examine alcohol consumption trends in the intervention and comparison communities. Laws and norms favorable to drug use was used as an indicator of enforcement is based on a risk factor scale score made up of multiple questions measuring the same construct. The present study examined enforcement of underage drinking laws by student responses (1=NO!; 2=no; 3= yes; 4= YES!) to the survey item from this scale: “If a kid drank some beer, wine or hard liquor (for example, vodka, whiskey, or gin) in your neighborhood how likely would he or she be caught by the police?”

Data Analysis

To compare data across each year of the study, data were transformed in SPSS by level of use to create new dichotomous variables that were then aggregated to calculate and report the percentage of students reporting binge drinking one or more times, as well as the percentage of students reporting “No” (responses for “NO!” and “no” were collapsed) for perceived enforcement at the district and community levels for both intervention and comparison conditions.

Mixed level modeling was used to accommodate the unbalanced sample and nesting of districts in communities. A two-level model was used to evaluate whether there was a change in youth binge drinking and perceived enforcement in school districts across conditions (i.e., from baseline to intervention), and both within and across intervention and comparison districts. Prior to modeling, a rigorous matching criteria based on district characteristics was used to identify appropriate comparison districts. The resulting two-level hierarchical data structure included 25 districts (level 1) that were nested within eight communities across study groups (level 2).

Analyses were computed using a SPSS linear mixed model procedure. The main effect of study conditions (1 = baseline, 0 = intervention) and district (1 = SPF intervention, 0 = comparison) was included, as well as the interaction between baseline condition and district was examined. A total of six parameters were tested, including four fixed effect parameters that estimated the fixed intercept, baseline, district, and baseline-district interaction. Two random parameters estimated the variability between districts and within districts. The method used the maximum likelihood estimation and an unstructured covariance structure. Separate models were estimated for each dependent variable. Wald test statistics for significance using a 95% confidence interval are reported.

Results

Number and Types of Community Change

From January 1, 2009 to June 30, 2012, coalitions from the intervention communities collectively facilitated 137 community changes (M = 17.1, SD = 27.78) consisting of new or modified policies and practices that supported implementation of the nine environmental strategies. Approximately 5.8% of the community changes were policy changes (e.g., courts ordering parents to attend parenting classes through the Strengthening Families program), and 94.2% were practice changes (e.g., stricter enforcement of checking identification by retailers) established in communities (see Table 3 for illustrative examples of policy and practice changes). More community changes (36%, n = 48) were related to Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol than any other implemented environmental strategy, and also half of the SPF coalitions selected this strategy to implement.

Table 3.

Illustrative Examples of Facilitated Community Changes by Type and Environmental Strategy

| Environmental Strategy | Community Change Type | Community Change Description |

|---|---|---|

| Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol |

Policy | Coalition members introduced an amendment to a House Bill that was signed into law by the Governor to clarify the crimes and punishment for social hosting by defining social hosting as intentionally or recklessly permitting one's residence or property to be used by another party in a way that results in the possession or consumption of alcohol by minors. |

| Collaboration with Schools | Policy | Local school board modified a policy in the handbook to include sanctions for the use and distribution of mood altering chemicals. New Policy: Twenty-four hours each day during the season of each activity, a student shall not use or consume, have in possession, buy, sell or give away any beverage containing alcohol, any illegal drug or controlled substance, tobacco, or any mood altering chemical in any form, including chewing tobacco. |

| Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol |

Policy | School district adopted a new policy for students and alcohol use. The policy includes clear penalties for students who use or are caught with alcohol and covers all students, not just those in sports activities. Task Force members were involved in the revision & adoption of the policy. |

| Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol |

Practice | For the first time, three weekly public service announcements have ran on broadcast television and cable talking about the consequences of underage drinking. Broadcast television reached 124,934 viewers ages 18-49 and 220 total spots. |

| Communities Mobilizing for Change on Alcohol |

Practice | Sheriff and deputies patrolled the county fair events to help with the efforts to prevent underage drinking. In the past, there has been underage drinking at the county fair with adults involved. This year there were no reports of underage drinking on county fair grounds. |

| Saturation Patrols | Practice | For the first time, police conducted "Operation Did You Know?" Police went to 27 liquor stores and issued 7 citations for selling alcohol to minors. |

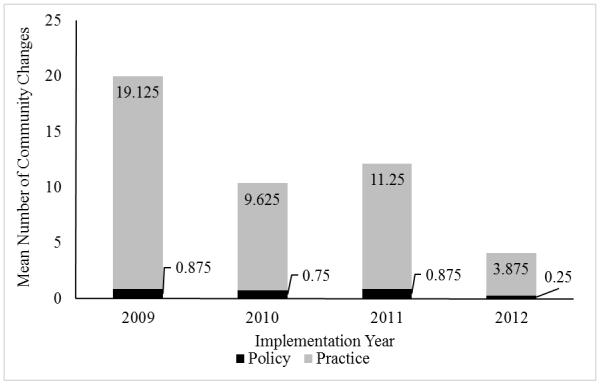

Figure 1 shows the mean number of program and policy changes per community for 2009-2012. The greatest number of mean community changes occurred in 2009, with coalitions facilitating a mean of 20 policy and practice changes. In each implementation year, new practices accounted for the majority of the community changes, with an average of 88 facilitated policy and practice changes per community. Policy changes accounted for the fewest percentage of community changes from 2009-2012, with a mean of five policy and practice changes.

Figure 1.

Mean number of policy and practice changes facilitated by eight coalitions in the intervention group by year, from 2009-2012.

The cumulative number of facilitated community changes across the study period indicated that almost 30% (n = 38) of all community changes were implemented in 2009 and consisted of practice changes. In each implementation year, new practices accounted for the majority of the community changes, ranging from 89% - 100%. Policy changes accounted for the fewest percentage of community changes from 2009-2012, ranging from 0% - 13%.

Enforcement of Existing Underage Drinking Laws

In 2007, a larger percentage of youth in the intervention districts reported they would not be caught by police for drinking alcohol than youth in the comparison districts (73.2% versus 69.7%, respectively). By the end of the study period, the rates were comparable between the intervention and comparison districts (63.1% versus 63.0%, respectively). In 2012, the intervention group showed a 15.3% increase in enforcement of underage drinking laws compared to 2007. The comparison group showed a 15.9% increase, suggesting that both study groups showed comparable percent improvement compared to the baseline year.

Results from the multilevel model for outcomes related to enforcement of existing underage drinking laws are shown in Table 4. Intraclass correlation coefficients showed substantial variation in enforcement outcomes within and between districts. The within-district variation was 99%, whereas the between-district variation was 2%. The multilevel model revealed significant increases in the percentage of youth reporting that they would be caught by police for consuming alcohol, F(1,44415) = 29.36, p < .001. There were also significant differences between the intervention and comparison districts, F(1,26) = 5.13, p = .032. However, no significant study condition by study group interactions were found, F(1,44415) = 0.82, p = .366. Significant variances were found in the within-districts random effect, Wald Z = 148.98, p < .001 and in the between-districts random effect, Wald Z = 3.16, p = .002.

Table 4.

Multilevel Model of Binge Drinking and Enforcement for Districts within Communities

| Multilevel Model of Binge Drinking for Districts within Communities | |||

|

| |||

| Parameter | Test statistic | Wald-Z | p-value |

|

| |||

| Fixed effects* | |||

| Intercept | 5637.83 | -- | <.001 |

| Study condition (intervention vs. baseline) |

10.80 | -- | .001 |

| Study group (intervention vs. comparison) |

0.14 | -- | .713 |

| Condition × group | 9.05 | -- | .003 |

| Random parameters** | |||

| Within-district variance | 0.87(0.01) | 151.68 | <.001 |

| Between-district variance | 0.01(0.002) | 3.15 | .002 |

|

| |||

| Multilevel Model of Enforcement for Districts within Communities | |||

|

| |||

| Test statistic | Wald-Z | p-value | |

|

| |||

| Fixed effects* | |||

| Intercept | 10779.79 | -- | <.001 |

| Study condition (intervention vs. baseline) |

29.36 | -- | .002 |

| Study group (intervention vs. comparison) |

5.13 | -- | .075 |

| Condition × group | 44414.82 | -- | .366 |

| Random parameters** | |||

| Within-district variance | 0.86(0.01) | 148.98 | <.001 |

| Between-district variance | 0.01(0.002) | 3.16 | .002 |

F-statistic is reported;

Estimate(SE) is reported

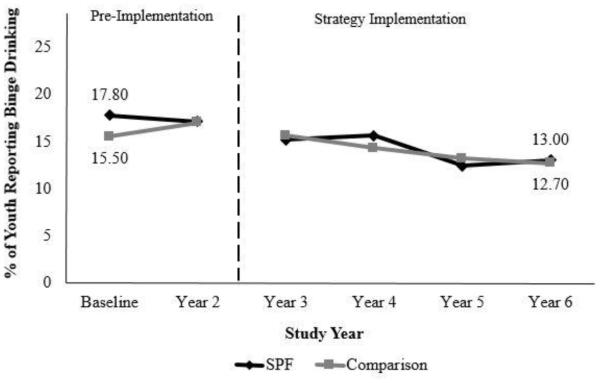

Binge Drinking

Over the study period, youth reported lower prevalence of binge drinking. In 2007, the intervention districts reported a higher mean prevalence of binge drinking than the comparison districts (17.8% versus 15.5%, respectively). By 2012, the rates were comparable between the groups (13.0% versus 12.7%, respectively). Although both study groups showed reductions in binge drinking, the intervention group showed a greater percent change than the comparison group between 2007 and 2012 (27% versus 18% reduction, respectively).

Results from the multilevel model for binge drinking outcomes are shown in Table 4. Intraclass correlation coefficients, which indicate the total variance of the outcome into its clusters, showed substantial variation in the within-district (level 1) and between-district (level 2) binge drinking rates. The within-district variation was 99%, and the between-district variation was 0.2%. The multilevel model revealed that across all districts in the study, there was a significant main effect for study condition, indicating a reduction in binge drinking outcomes between the baseline and intervention conditions, F(1,46038) = 10.80, p = .001. However, there were no significant differences between districts in the intervention versus comparison groups, F(1,27) = 0.14, p = .713. The results revealed a significant interaction between study condition (i.e., baseline versus intervention) and study group (i.e., intervention versus comparison), F(1, 46038) = 9.05, p = .003. Significant variances were also found in the within-districts random effect, Wald Z = 151.68, p < .001 and in the between-districts random effect, Wald Z =3.15, p = .002.

Discussion

The present study examined the effects of implementing the Strategic Prevention Framework on binge drinking prevalence and enforcement of existing underage drinking laws. Although the intervention communities showed improvements in outcomes that were more substantial than in the comparison districts, differences between the groups were not significant. These findings suggest that the overall effects on self-reported behavior change related to binge drinking across the intervention communities were minimal. However, in the context of implementing multi-site, comprehensive community prevention interventions, effect sizes may be too small to detect between study groups. In the present study, the state substance abuse prevention system sought to reduce underage drinking outcomes in communities that were affected disproportionately. Therefore, the very modest improvements, although not statistically significant in the present study, may have some merit by local coalitions and state partners in regards to efforts to improve overall statewide levels of enforcement and binge drinking.

Number and Type of Community Changes

During the intervention period (2009 -2012), the SPF-funded coalitions facilitated community changes through their implementation of environmental strategies. The coalitions facilitated substantially more practice changes than policy changes as a result of implementing the SPF. When implemented and enforced, policy changes may be more readily maintained longer-term, as compared to prevention programs, as it is not often contingent on funding (Mittlemark, Hunt, Heath, & Schmid, 1993).

Additional considerations may explain the relatively lower percentage of implemented policies compared to practices. First, policy changes require more effort on the part of coalition representatives and change agents; such work may include establishing and maintaining partnerships, mobilizing community members, and obtaining support from key stakeholders. Second, changing the conditions that contribute to underage drinking through policy changes change takes a longer time to facilitate, particularly given the effort and community engagement required to implement these changes successfully. Facilitating policy change may span multiple years, from policy development to approval to implementation. Thus, it is likely that some of the coalitions’ ongoing work may have been related to enacting future policy change, which may have been more fully achieved after the study period. More broadly, facilitating new practices may serve a precursor to implementing new policies, which collectively contribute to widespread behavior change.

Binge Drinking and Enforcement

The study’s findings were mixed with respect to implementing the Strategic Prevention Framework and its effects on improving outcomes related to binge drinking and enforcement. Although the intervention communities showed a more substantial reduction in outcomes, there were significant reductions in underage drinking outcomes in both the intervention and comparison districts during the study period. The multilevel model showed that youth in school districts that implemented enforcement interventions reported a greater likelihood of being caught by police if they were drinking alcohol in their neighborhood than did youth in similar districts that did not implement enforcement interventions. However, the reduction in reported binge drinking outcomes was not significantly greater in districts that implemented enforcement interventions. Additional studies may be helpful to examine some of the intervention communities that demonstrated more substantial improvements in outcomes to better understand the community and coalition factors and contexts that may have enabled more full and effective implementation of the environmental strategies related to enforcement and binge drinking.

A few reasons may explain why the comparison communities also showed reductions in binge drinking and enforcement outcomes. There may have been delayed effects of community changes implemented in the latter years of the intervention. For example, policy changes implemented in 2012 may have had a lesser impact on outcomes during the study period; however, those policy changes may be more impactful in subsequent years. Other research focused on supporting improvements in community-level prevention outcomes using measures from the CTC survey has shown that it may take 2 to 5 years to modify risk and protective factor outcomes, and 4 to 10 years before community-level impact on adolescent substance use may be observed (Oesterle et al., 2015).

Furthermore, cross-diffusion of intervention effects may have occurred. For instance, one intervention community intentionally increased car stops for alcohol checks on roads bordering the county line to minimize displacement effects (e.g., youth now binge drinking at parties in county neighboring county after stricter enforcement in the intervention community). State prevention systems may find the diffusion not only appropriate, but also desirable to achieve long-term goals. Additionally, the improvements may have been influenced by statewide prevention efforts to reduce underage drinking, such as the statewide media campaign.

Another factor that may contribute to modest improvements between the intervention and comparison groups is regression to the mean. Based on the selection criteria by the state department that was awarded the grant, participant communities selected higher prevalence of binge drinking in the state, therefore, by the end of the study period, the levels of binge drinking in the intervention communities was more comparable to the comparison group average. It is plausible that more substantial differences may have been observed between the intervention and comparison groups if communities with the highest prevalence were not intentionally selected for study participation. However, due to political factors, random selection was not possible in the present study.

Study Limitations

There were limitations with the present study that warrant consideration. Because randomization was not used to assign communities to study conditions, causal inferences between the independent and dependent variables are limited. Future studies should attempt to randomize communities into study conditions. However, because states may have varying selection criteria for local coalition funding, randomization may not be feasible. There was also a possibility of binge drinking and enforcement outcomes regressing toward the mean, particularly if the study communities’ prevalence rates were higher than rates from communities not included in the present study.

While efforts were made to collect permanent products of documented community changes (e.g., meeting minutes, written policies, newspaper articles), it is possible that there was underreporting of coalition prevention activities. Additionally, the KCTC survey data were based on youth’s self-reported behavior. Although the Communities That Care Survey has been validated and commonly used in prevention research, there is a possibility of reactive measurement bias to self-report. Future work should consider also using more objective or corroborating data to provide additional support for self-reported findings. Finally, the statewide prevention efforts (e.g., statewide media campaign) may have been a confounding variable in examining differential effects in outcomes between the intervention and comparison communities. In practice, however, a multi-layered prevention approach that combines efforts from local coalitions and statewide prevention systems may be desirable to occasion population- level improvement in underage drinking outcomes over time and across communities.

Conclusion

The present study represents one of the few empirical examinations of the SPF’s effects on underage drinking and associated influencing factors. One factor that may contribute to the modest number of studies examining behavioral outcomes is that process measures are more readily available across local and state prevention systems, whereas behavioral outcome data may be limited (e.g., Orwin et al., 2014; Piper et al., 2012). Our findings suggest that SPF implementation may support coalitions in facilitating community changes, which may contribute to some modest improvements in binge drinking and enforcement-related outcomes over time. The reductions observed in the intervention districts were more substantial than in the matched comparison districts, but since significant differences were not observed between the groups, which suggests minimal intervention effects noted in the present study. Additional studies and of potentially longer duration are needed to examine the intervention effects of the model, specifically within the context of the implementation of environmental strategies, on risk and protective factor and longer-term community-level outcomes.

The present study is part of a larger study examining the implementation of the SPF in Kansas. The focus of the present study specifically examined the use of the SPF model to support implementation of evidence-based strategies across multiple communities prioritizing enforcement and binge drinking as influencing factor and community-level outcomes. The present study specifically examines the implementation of enforcement strategies by SPF-funded communities and related outcomes. It is important to support additional studies that may comprehensively examine multiple strategies (e.g., programs and environmental strategies) and additional outcomes (e.g., 30-day use) implemented in supporting the comprehensive community interventions.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has provided millions of dollars in grant funding to state prevention systems over the past 10 years to support substance use prevention efforts. At the community level, harmful behaviors and associated adverse conditions occur across multiple socioecological levels. Given the context and conditions in which such behaviors occur, coalitions often use interventions that use both evidence-based programs and environmental strategies to affect change. Understanding the implementation of environmental strategies as components of comprehensive prevention interventions may help to better associate improvements in targeted influencing factors with improvements in outcomes such as binge drinking. Investigating the relationship between influencing factors and outcomes is critical, as influencing factors serve as precipitating events for binge drinking outcomes. Furthermore, by examining coalition efforts that facilitate community-level changes to support improvements in outcomes, scientists and practitioners can develop and implement effective interventions that are both culturally appropriate and sustainable over time.

Figure 2.

Binge drinking outcomes over time for intervention and comparison districts, 2007- 2012.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by funding from the Kansas SPF-SIG, awarded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to the Kansas Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award number 5T32DA007272-23. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or any other participating organization.

References

- Anderson-Carpenter KD, Watson-Thompson J, Jones M, Chaney L. Using Communities of Practice to Support Implementation of Evidence-Based Prevention Strategies. Journal of Community Practice. 2014;22(1-2):176–188. doi:10.1080/10705422.2014.901268. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur MW, Hawkins JD, Pollard JA, Catalano RF, Baglioni AJJ. Measuring risk and protective factors for substance use, delinquency, and other adolescent problem behaviors: The communities that care survey. Evaluation Review. 2002;26(6):575–601. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0202600601. http://doi.org/10.1177/019384102237850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitstein JL, Murray DM, Lytle LA, Birnbaum AS, Perry CL. Predictors of violent behavior in an early adolescent cohort: Similarities and differences across genders. Health Education and Behavior. 2005;32(2) doi: 10.1177/1090198104269516. http://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104269516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National high school YRBS data files, 1991-2011. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/data/index.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Fact sheets--underage drinking. Alcohol and Public Health. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/underage-drinking.htm.

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Wechsler H. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance--United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summary. 2012;61(4):1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy JJ, Gideonsen MD, McClaflin RR, O’Halloran P, Peardon FA, Radcliffe PL, Masters LA. Reducing alcohol use in youth aged 12-17 years using the strategic prevention framework: Reducing alcohol in youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;40(5):607–620. http://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21485. [Google Scholar]

- Elder RW, Lawrence B, Ferguson A, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Chattopadhyay SK, Fielding JE. The Effectiveness of Tax Policy Interventions for Reducing Excessive Alcohol Consumption and Related Harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(2):217–229. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florin P, Friend KB, Buka S, Egan C, Barovier L, Amodei B. The interactive systems framework applied to the strategic prevention framework: The Rhode Island experience. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;50(3-4):402–414. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9527-5. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9527-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesbrecht N, Greenfield TK. Preventing alcohol-related problems in the US through policy: Media campaigns, regulatory approaches and environmental interventions. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2003;24(1):63–104. [Google Scholar]

- Holder HD, Gruenwald PJ, Ponicki WR, Treno AJ, Grube JW, Roeper P. Effect of community-based interventions on high-risk drinking and alcohol-related injuries. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(18):2341–2347. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D. A useful tool for designing strengthening and evaluating programs to reduce adolescent sexual risk-taking, pregnancy, HIV, and other STDs. 2004 Retrieved from http://recapp.etr.org/recapp/documents/bdilogicmodel20030924.pdf.

- Kirby T, Barry AE. Alcohol as a gateway drug: A study of US 12th graders. Journal of School Health. 2012;82(8):371–379. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2012.00712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton JC, Hahn RA, Kuzara JL, Elder R, Brewer R, Chattopadhyay S, Lawrence B. Effectiveness of policies maintaining or restricting days of alcohol sales on excessive alcohol consumption and related harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;39(6):575–589. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.015. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007;119:76–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittlemark MB, Hunt MK, Heath GW, Schmid TL. Realistic outcomes: Lessons from community-based research and demonstration programs for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Public Health Policy. 1993;14(4):437–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwin RG, Stein-Seroussi A, Edwards JM, Landy AL, Flewelling RL. Effects of the Strategic Prevention Framework State Incentives Grant (SPF SIG) on state prevention infrastructure in 26 states. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2014;35(3):163–180. doi: 10.1007/s10935-014-0342-7. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-014-0342-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle S, Hawking JD, Kuklinski MR, Fagan AA, Fleming C, Rhew IC, Catalano RF. Effects of communities that care on males’ and females’ drug use and delinquency 9 years after baseline in a community-randomized trial. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2015;56:217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9749-4. doi:10.1007/s10464-015-9749-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paek H-J, Hove T. Determinants of underage college student drinking: Implications for four major alcohol reduction strategies. Journal of Health Communication. 2012;17(6):659–676. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.635765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper D, Stein-Seroussi A, Flewelling R, Orwin RG, Buchanan R. Assessing state substance abuse prevention infrastructure through the lens of CSAP’s Strategic Prevention Framework. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2012;35(1):66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.07.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelleman-Offermans K, Knibbe RA, Kuntsche E, Casswell S. Effects of a natural community intervention intensifying alcohol law enforcement combined with a restrictive alcohol policy on adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51(6):580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.03.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer MA, Hilton JF, Ekstrand M, Keogh J, Gee L, DiGiorgio-Haag L, Schacter J. Relationship between drug use and sexual behaviors and the occurrence of sexually transmitted diseases among high-risk male youth. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1993;20(6):307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Prevention of substance abuse and mental illness: Strategic Prevention Framework components. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.samhsa.gov/prevention/spfcomponents.aspx.

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services Recommendations on Dram Shop Liability and Overservice Law Enforcement Initiatives to Prevent Excessive Alcohol Consumption and Related Harms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2011;41(3):344–346. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.024. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenaar AC, Wolfson M. Deterring sales and provision of alcohol to minors: A study of enforcement in 295 counties in four states. Public Health Reports. 1995;110(4):419–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RD, Jr., Perko MA, Belcher D, Leaver-Dunn DD, Usdan SL, Leeper J. Use of social ecology model to address alcohol use among college athletes. American Journal of Health Studies. 2006;21(4):228–236. [Google Scholar]

- Work Group for Community Health and Development Chapter 2, section 1: Developing a logic model or theory of change. 2015 Retrieved from the Community Tool Box: http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/overview/models-for-community-health-and-development/logic-model-development/main.