Abstract

Dating several people in emerging adulthood has been associated with higher alcohol use compared to being single or being in an exclusive relationship. As a follow-up to that report, we examined whether romantic relationship status is part of a pathway of risk between antecedent alcohol use risk factors and subsequent alcohol outcomes. Participants were 4,410 emerging adults assessed at two time-points during their first year of college. We found that a parental history of alcohol problems was indirectly related to dating several people via two modestly correlated pathways. The first pathway was through conduct problems. The second pathway was through positive urgency (i.e., a positive emotion-based predisposition to rash action). In turn, dating several people was associated with higher alcohol use. Our results suggest that these familial and individual-level alcohol risk factors are related to emerging adults' selection into subsequent romantic relationship experiences that are associated with higher alcohol use. These findings have implications for how romantic relationship experiences may fit into developmental models of the etiology of alcohol use.

Keywords: alcohol risk factors, romantic relationship status, emerging adulthood

The role of romantic relationship status in pathways of risk for emerging adult alcohol use

Exploration and experimentation in romantic relationships are important components of social development in emerging adulthood (Shulman, Scharf, Livne, & Barr, 2013). Romantic experiences during this period of the lifespan are also associated with behavioral health outcomes, including alcohol use and misuse (Braithwaite, Delevi, & Fincham, 2010). Emerging adults in cohabiting relationships engage in less heavy drinking compared to singles (Fleming, White, & Catalano, 2010), and college students in committed relationships drink less often, are less likely to engage in heavy episodic drinking (Braithwaite et al., 2010), and are less likely to have alcohol problems (Whitton, Weitbrecht, Kuryluk, & Bruner, 2013) compared to singles. In a more recent report, first year college students who were single or in an exclusive relationship had lower alcohol use and fewer alcohol problems compared to those dating several people (Salvatore, Kendler, & Dick, 2014).

One question that has not been addressed in this literature concerns whether and how romantic relationship status in emerging adulthood fits into broader etiological models of alcohol use and alcohol use disorder (Sher, Grekin, & Williams, 2005). This is an important gap in our understanding of whether risk factors for alcohol use are also associated with romantic relationship status during this period, and whether romantic relationship status is part of a pathway of risk between antecedent alcohol use risk factors and subsequent alcohol outcomes. Jessor and Jessor's (1977) Problem-Behavior Theory (PBT) provides a useful conceptual backdrop for answering this question. PBT is a systems-based perspective that views one's proneness to deviant behavior as a cumulative process that has its roots in familial and socialization risk factors. It is hypothesized that that these antecedent-background factors predict subsequent psychosocial factors (i.e., personality and perceptions of the environment) that promote or discourage a constellation of deviant behaviors (e.g., conduct problems, underage or risky drinking, unprotected intercourse, etc.) that can undermine individuals' health and safety. Previous research informed by PBT found that psychosocial factors in adolescence accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance (> 50%) in problem drinking in emerging adulthood (ages 23-27) (Jessor, 1987)

Although romantic relationship status is not explicitly addressed in PBT, there is theoretical reason to examine it as part of a broader set of psychosocial risk factors for alcohol use and problems in emerging adulthood. From a developmental perspective, romantic relationships in emerging adulthood are an important context for intimacy and for experimentation in different types of relationships, typically without the pressure of marital commitment (Arnett, 2000). There is variability in emerging adults' participation in and commitment to romantic relationships, and this variability is linked to antecedent psychosocial factors. For example, those with lower self-efficacy, immature dependency (wishing to be cared for while also fearing abandonment, akin to “dinginess”), and lower parental support are more likely to be in non-stable or non-intimately committed romantic relationships seven years later in emerging adulthood (Shulman et al., 2013). Thus, emerging adult romantic relationship participation appears to have meaningful associations with earlier psychosocial factors.

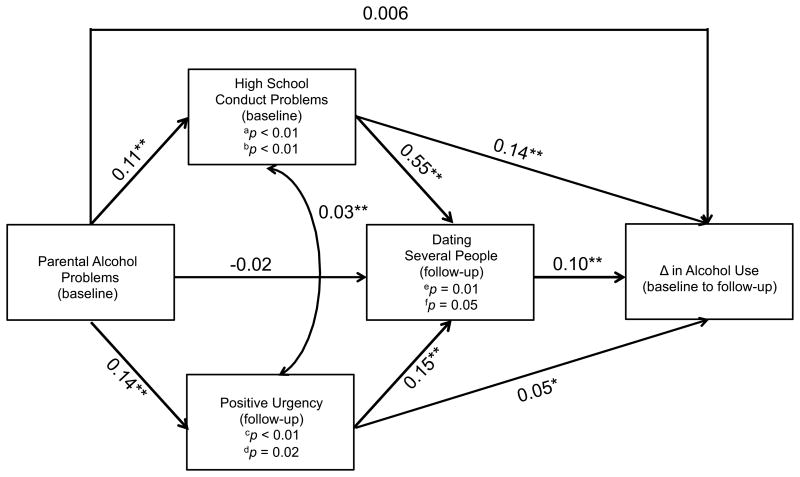

With respect to alcohol, a number of studies show that alcohol use and problems are lower for emerging adults in committed or cohabiting romantic relationships (Braithwaite et al., 2010; Fleming et al., 2010; Whitton et al., 2013). Despite these associations, there has been little attention paid to how romantic relationship status in emerging adulthood fits into a broader set of psychosocial and behavioral risk factors for alcohol use. We were particularly interested in pursuing the recent finding that dating several people is distinctly associated with higher alcohol use compared to being single or being in an exclusive relationship in emerging adulthood (Salvatore et al., 2014). Our goal here was to examine how psychosocial and behavioral risk factors for alcohol use were related to dating several people and, in turn, alcohol use. Our conceptual model is shown in Figure 1. In the sections below, we elaborate on the hypothesized pathways linking parental alcohol problems, intermediate psychosocial and behavioral outcomes, romantic relationship status, and alcohol use.

Figure 1.

A path model depicting the associations among parental alcohol problems, romantic relationship status, and changes in alcohol use. The estimates are unstandardized coefficients. The information noted inside conduct problems, positive urgency, and dating several people boxes indicates which assessment the variables came from (baseline or follow-up) and the p-values associated with the mediation effects through those variables. Variables are mediators for multiple pathways, which are denoted by the following superscripts: aparental alcohol problems→conduct problems→dating several people; bparental alcohol problems→conduct problems→alcohol use; cparental alcohol problems→positive urgency→dating several people; dparental alcohol problems→positive urgency→ alcohol use; eparental alcohol problems→conduct problems→dating several peopled alcohol use; fparental alcohol problems→positive urgency→dating several peopled alcohol use. Sex and race were entered as covariates but are not shown. *p < 0.05. ** p < 0.01.

Parental Alcohol Problems, Romantic Relationship Status, and Alcohol Use

Parental alcohol use disorder confers environmental and genetic risk for alcohol problems in offspring (Kendler et al., 2015b) and also puts individuals at risk for more problematic and less stable and satisfying romantic relationships (Kearns-Bodkin & Leonard, 2008; Larson, Taggart-Reedy, & Wilson, 2001). Young adult children with a parental history of alcohol use disorder express more negative views about marriage and a desire to wait longer to commit (Larson & Thayne, 1999), but also tend to marry earlier than those without a parental history of alcohol use disorder (Dawson, Grant, & Harford, 1992). Furthermore, parental alcohol use disorder is also associated with insecure romantic attachment (Cash, Grant, Kelley, Miles, & Santos, 2004; Jackson, Parra, Sher, & Vungkhanching, 2004). Attachment avoidance, where individuals minimize their needs for emotional intimacy out of concerns of abandonment, has previously been linked to “hooking up” (i.e., sexual interactions outside of a committed relationship; Epstein, Calzo, Smiler, & Ward, 2009) (Fielder, Walsh, Carey, & Carey, 2013). In short, emerging adults with a parental history of alcohol use disorder appear to have mixed feelings and behaviors toward exclusive romantic relationships. This ambivalence and their tendency to avoid intimacy may manifest in emerging adulthood as a higher likelihood of participating in multiple non-exclusive romantic relationships.

Above and beyond these direct effects, parental alcohol use disorder or problems are also hypothesized to have indirect effects on offspring romantic relationship status and subsequent alcohol use. As shown in Figure 1, we consider two potential pathways for understanding the links from parental alcohol problems to romantic relationship status and eventually alcohol use: a deviance proneness pathway, and a positive affect regulation pathway (Sher et al., 2005). We selected these two etiological pathways for the present study over two others described by Sher et al. (2005) (i.e., the negative affect regulation pathway and the pharmacological vulnerability pathway) in view of their potential relevance for understanding how romantic relationship status may be related to alcohol risk factors and subsequent alcohol use in an emerging adult sample. As detailed in the next two sections, we selected conduct problems and positive urgency as markers of the deviance proneness and positive affect regulation pathways, respectively.

Deviance Proneness Pathway from Parental Alcohol Problems to Romantic Relationship Status and Alcohol Use

The deviance proneness pathway refers to one's predisposition toward impulse control problems and disinhibited behavior, including antisocial behavior and substance use/misuse (Kendler, Prescott, Myers, & Neale, 2003; Krueger et al., 2002), and is historically one of the most well-studied and robust etiological pathways for alcohol misuse (Sher et al., 2005). The central premise is that alcohol misuse reflects a long-standing susceptibility to disinhibited behavior that begins to manifest as deviant behavior in childhood and adolescence (Zucker & Lisansky Gomberg, 1986). This broadband predisposition appears to largely reflect familial risk (Hicks, Krueger, Iacono, McGue, & Patrick, 2004); for example, parental alcohol use disorder has a well-replicated association with deviant behavior in offspring (Haber et al., 2010; Sher, Walitzer, Wood, & Brent, 1991). Deviant behavior and conduct problems in adolescence are, in turn, a well-known risk factor for risky alcohol use outcomes later on, including higher alcohol use (Lynskey & Fergusson, 1995) and the probability of developing an alcohol use disorder (Slutske et al., 1998).

We further hypothesize that there may be an indirect effect of parental alcohol problems on alcohol use via adolescent conduct problems and romantic relationship involvement. Specifically, there is evidence that conduct problems earlier in development appear to be a barrier to the formation of harmonious romantic relationships later on (Quinton, Pickles, Maughan, & Rutter, 1993). Horn et al. (2013) found that those who were married or cohabiting with a romantic partner in early adulthood had fewer conduct problems compared to unpartnered individuals, and that this reduced prevalence existed prior to the initiation of the cohabiting or marital relationship. Similarly, men with fewer conduct problems early in life were more likely than men with conduct problems to marry in adulthood (Jaffee, Lombardi, & Coley, 2013). In short, individuals who are prone to deviant behavior may be less likely to form exclusive, committed romantic relationships later in life. Thus, we expect there to be continuity between individuals' history of deviant behavior, their romantic relationship involvement, and their alcohol use.

Positive Affect Regulation Pathway from Parental Alcohol Problems to Romantic Relationship Status and Alcohol Use

The positive affect regulation pathway refers to emotionality characteristics that are associated with the use of alcohol for its positive reinforcement effects (i.e., feeling good) (Mezquita et al., 2015), and is closely tied to traits associated with perceiving alcohol use as rewarding (Sher et al., 2005). One of these traits is positive urgency, which is a positive emotion-based predisposition to rash action (Cyders & Smith, 2008; Cyders et al., 2007). Although the association between parental alcohol use disorder and positive urgency has not been explicitly examined in the past, there is evidence that parental alcohol use disorder is associated with deactivation in the fronto-parietal region in the context of an emotional Go-NoGo inhibitory task (Cservenka, Fair, & Nagel, 2014). This provides reason to believe that a parental history of alcohol problems might also predict difficulty controlling one's self in the context of positive emotions (i.e., higher levels of positive urgency). Positive urgency is a distinctive risk factor for alcohol use in emerging adulthood (Cyders et al., 2007), and there is longitudinal evidence that it predicts alcohol use above and beyond other indicators of non-emotion based impulsivity such as sensation seeking (Cyders & Smith, 2010). Positive urgency appears to be an especially useful trait for understanding alcohol use in emerging adult college students, whose drinking typically is associated with celebratory events and positive moods (Del Boca, Darkes, Greenbaum, & Goldman, 2004).

We hypothesize that positive urgency may also be related to emerging adults' romantic relationship status. Involvement in romantic relationships becomes increasingly normative during emerging adulthood (Carver, Joyner, & Udry, 2003; Shulman et al., 2013), and is associated with positive emotionality (Shiner, Masten, & Tellegen, 2002). The mesolimbic dopamine pathway is also implicated in social bonding (Burkett & Young, 2012), suggesting that exploration and experimentation in romantic relationships may be rewarding, in part, because these novel social experiences tap into relevant neurocircuitry. On the basis of these lines of evidence, we would expect there to be continuity between individuals' positive urgency, their romantic relationship involvement, and their alcohol use.

Current Study and Hypotheses

We were interested in mapping the direct and indirect effects of parental alcohol problems on romantic relationship involvement and alcohol use at the beginning of emerging adulthood. We tested whether three alcohol-related risk factors (parental history of alcohol problems, conduct problems, and positive urgency) were associated with romantic relationship status and alcohol use in a sample of 4,410 individuals at the beginning of emerging adulthood. We tested a model informed by the deviance proneness and positive affect regulation pathways as well as the results from an earlier report (based on n = 2,056; Salvatore et al., 2014) that dating several people is distinctly associated with higher alcohol use compared to being single or being in an exclusive relationship. We had three primary hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: A parental history of alcohol problems would predict a higher likelihood of dating several people.

Hypothesis 2: A parental history of alcohol problems would have indirect effects on the likelihood of dating several people via elevations in conduct problems and positive urgency.

Hypothesis 3: These alcohol risk factors would have indirect effects on alcohol use via dating several people.

In supplemental exploratory analyses, we examined whether there were sex differences in these hypothesized effects.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants came from a large, on-going longitudinal study of the behavioral and emotional health of college students at a public university in the mid-Atlantic (Dick et al., 2014). The present report uses data from the August 2014 project data release. Baseline and follow-up data were collected on three consecutive cohorts during the fall and the spring, respectively, of participants' first year of college via on-line surveys administered using REDCap software (Harris et al., 2009). For the baseline assessment, incoming first-year students 18 years of age or older were invited via email to complete the survey starting one week before their arrival on-campus up until the tenth week of the fall semester. Of the 10,497 individuals who were eligible to complete the study's baseline fall assessment, 6,120 participated (58% response rate, cohort 1 n = 2055, cohort 2 n = 2038, cohort 3 n = 2027. Of these, 38% were male, 61% were female, 1% declined to identify sex. The sample reflected the population from which it was drawn: 51% White, 19% African-American, 16% Asian, 6% Hispanic/Latino, 8% other/multi-race/unknown/declined to respond. The average age at assessment was 18.42 years.

Those who completed the baseline survey were subsequently invited via email to complete a follow-up assessment between weeks 7 and 14 of the spring semester of their freshman year. Of those who completed the baseline assessment and who were still enrolled at the University (5,893 participants), 4,410 also completed the follow-up assessment (75% retention). This study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board. Participants read through an on-line consent document and indicated that they understood the potential risks and benefits of participating, and were paid $10 for each survey.

Measures

Parental history of alcohol problems (baseline)

Participants reported whether they believed their biological mother or father ever had a drinking problem (Yes or No). For our analyses, we created a composite parental history of alcohol problems measure indexing whether either parent had an alcohol problem. Participants who indicated that neither parent had an alcohol problem were assigned a score of 0 and those who indicated that either parent had an alcohol problem were assigned a score of 1. Further details regarding the development and predictive validity of these brief family history screening items can be found in Kendler et al. (2015a).

High school conduct problems (baseline)

Participants were asked six items about how frequently they engaged in a range of problem behaviors as teenagers (e.g., skipping school, stealing) on a four-point scale coded 0 (Never), 1 (1-2 times), 2 (3-5 times), 3 (6 or more times). Items were adapted from the Conduct Disorder section of the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (Bucholz et al., 1994). Sum scores were calculated for use in analyses.

Positive urgency (follow-up)

Participants were asked three positive urgency items from the abbreviated positive urgency subscale of the UPPS-P (Lynam, Smith, Whiteside, & Cyders, 2006). These items asked each participant to indicate the degree to which he or she tends to lose control when in a great mood; the degree to which others are shocked or worried about the things the participant does when he or she is feeling very excited; and the degree to which the participant tends to act without thinking when he or she is really excited. Responses were made on a four-point scale with the following possible response options: 1 (Disagree strongly), 2 (Disagree a little), 3 (Agree a little), 4 (Agree strongly). Cronbach's alpha for these items was 0.75, and mean scores were calculated for use in analyses.

Relationship status (follow-up)

At follow-up, participants reported which of the following best described their current relationship status: not dating, dating several people, dating one person exclusively, engaged, married, married but separated, divorced, or widowed.

Alcohol use (baseline and follow-up)

Frequency and quantity information were used to calculate separate “grams of ethanol consumed per month” alcohol use variables for the baseline and follow-up assessments. At the baseline assessment for the first cohort, participants reported on their alcohol use on continuous measures. The continuous alcohol frequency question was, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you drink one or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage?” with response options 0 through 30 at one day intervals, I choose not to answer and Don't know. The continuous alcohol quantity question was, “On the days that you drank during the past 30 days, how many drinks did you usually have each day?” with response options 1 through 20 at one drink intervals, more than 20, I choose not to answer and Don't know.

Participants who responded “0” to the alcohol frequency question were not asked the alcohol quantity question, and were thus coded as 0 for alcohol quantity. Participants who selected I choose not to answer or Don't know to either the frequency or quantity question were coded as missing. The “grams of ethanol consumed” alcohol use variable was calculated by multiplying the product of frequency and quantity by 14 (the standard alcoholic drink contains 14 grams of ethanol per serving; i.e., Frequency × Quantity × 14).

For the second and third cohorts' baseline assessments, and for all cohorts' follow-up assessments, participants reported on their recent alcohol use with ordinal frequency and quantity items from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998). Frequency of alcohol use was assessed with the question “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?” and the response options were never, monthly or less, 2 to 4 times a month, 2 to 3 times a week, 4 or more times a week, and I choose not to answer. Quantity of alcohol use was assessed with the question “How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking?” with response options 1 or 2, 3 or 4, 5 or 6, 7, 8 or 9, 10 or more, and I choose not to answer.

These ordinal frequency and quantity items were combined to create a single “grams of ethanol consumed per month” alcohol use variable using a method previously reported in Dawson (2000). 1 This involved first converting the categorical response options for frequency and quantity to the midpoints of the range for each option, and then multiplying the product of these conversions by 14 (i.e., Frequency × Quantity × 14). The frequency conversions (shown in parentheses) were based on a month with 30 days and were: never (0), monthly or less (0.5), 2 to 4 times a month (3), 2 to 3 times a week (10.7), 4 or more times a week (23.54). The quantity conversions (shown in parentheses) were: 1 (1.5) or 2, 3 or 4 (3.5), 5 or 6 (5.5), 7, 8 or 9 (8), 10 or more (15.5; the upper bound for this category was defined as 21 to match the upper bound of the continuous alcohol quantity question administered to the first cohort). Participants who responded “0” to the alcohol frequency question were not asked the alcohol quantity question, and were thus coded as 0 for alcohol quantity. Participants who selected I choose not to answer to either the frequency or quantity question were coded as missing.

Covariates

Covariates included sex and race. Sex was coded 0 (female) and 1 (male). Race was coded with two dummy variables to indicate self-identification in the two largest racial/ethnic minority groups in the sample. Race1 was coded 0 (not black) and 1 (black); Race2 was coded 0 (not Asian) and 1 (Asian).

Analytic Plan

We first examined all continuous variables for normality, and applied appropriate statistical transformations so that the skew for all variables in our path model was less than |1|. A logarithm (base 10) transformation was applied to variables that were positively skewed. The logarithm of zero is undefined. In instances where a skewed variable had zero as a possible score, we added “1” as a constant prior to taking the logarithm [e.g., log10(alcohol use + 1) in order to retain these individuals in our analyses.

Following these preliminary analyses, we fit our theoretically informed path model in Mplus version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2011). As shown in Figure 1, this model tests whether parental alcohol problems have direct and indirect effects on follow-up romantic relationship status, and whether romantic relationship status is part of an indirect pathway linking these alcohol risk factors and alcohol use. In addition to these paths of primary interest, we also statistically controlled for the direct effects of all variables and covariates on alcohol use. This allowed us to examine whether our hypothesized indirect paths of interest were significant above and beyond the direct paths from parental alcohol problems, conduct problems, and positive urgency on alcohol use, as well as the indirect paths from parental alcohol problems→conduct problems→alcohol use and from parental alcohol problems→positive urgency→ alcohol use.

We chose to focus on dating several people as the romantic relationship status of interest in this model in view of earlier findings in this same sample that dating several people was distinctively associated with higher alcohol use and problems compared to being single or being in an exclusive relationship (Salvatore et al., 2014). 2 Accordingly, relationship status was dummy coded “Dating Several People” as 0 (Not dating several people: single, exclusive, engaged, married) or 1 (Dating several people). For our alcohol use outcome, we used a residualized change score (i.e., the saved residuals from a regression of follow-up alcohol use on baseline alcohol use). By using a residualized change score as our alcohol outcome, we reduce the potential confound that observed associations (e.g., between reports of parental alcohol problems and follow-up alcohol use) are purely attributable to the stability in alcohol use across the baseline and follow-up assessments, r(3736) = 0.69, p < 0.01. Covariates included sex and two dummy-coded race variables. Owing to the fact that our binary relationship status variable was a mediator in our model, we employed a robust weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) and THETA parameterization. Indirect effects in Mplus are estimated using the product of coefficients approach. The assumption that this product is normally distributed is often violated (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). Thus, in keeping with best practices proposed by MacKinnon et al. (2004), we used a bias-corrected bootstrap (n = 5000) in order to calculate 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects.

Following this primary analysis, we also conducted an exploratory analysis to examine potential sex differences in any observed effects. To do this, we ran the model shown in Figure 1 for males and females as part of a multi-group model. We then examined whether the paths could be equated across the male and female models in an omnibus test (df = 10).

Results

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for the study variables are shown for the sample in Table 1. Preliminary analyses indicated that the high school conduct problems and baseline and follow-up alcohol use variables were positively skewed (skew = 1.63, 5.34, and 5.40, respectively). As described above, logarithm transformations were applied in order to normalize variables so that their skew was less than |1| prior to running any analyses. All variables were positively intercorrelated (rs = 0.06 – 0.69), with the exception that the tetrachoric correlation between parental alcohol problems and dating several people was non-significant.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations among continuous study measures.

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parental alcohol problems | — | |||||

| 2. Conduct problems | 0.18 | — | ||||

| 3. Positive urgency | 0.07 | 0.15 | — | |||

| 4. Dating several people | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | — | ||

| 5. Baseline alcohol use | 0.15 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 0.12 | — | |

| 6. Follow-up alcohol use | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.69 | — |

| n | 5344 | 6043 | 4253 | 4296 | 5391 | 4219 |

| Mean | — | 2.11 | 1.91 | — | 170.73 | 204.59 |

| SD | — | 2.24 | 0.73 | — | 424.63 | 461.39 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 1 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 5108.18 | 5108.18 |

Notes. Abbreviations: n = sample size. SD = standard deviation. Min = minimum observed value. Max = maximum observed value. Descriptive statistics are reported using the original data. Correlations are based on logarithm (base 10) transformed versions of the conduct problems and alcohol use variables. Transformations were implemented so that skew<|1|. Pearson correlations are reported when both variables are continuous. Point biserial correlations are reported when one variable is continuous and the other is binary. The tetrachoric correlation is reported for the two binary variables (parental alcohol problems and dating several people). Bolded correlations indicate p < 0.01.

With respect to parental history of alcohol problems, 510 (8%) and 1281 (21%) participants reported that their mother and father, respectively, had an alcohol problem. In total, 3761 (61%) of participants indicated that neither parent had an alcohol problem, 1583 (26%) indicated that one or both parents had an alcohol problem. Participants who did not know or declined to respond for both parents [234 (4%)], or who did not know or declined to respond for one parent and indicated that the other parent did not have a suspected drinking problem [542 (9%)] were coded as missing, as it cannot be assumed that a parent for whom there is missing information would be unaffected. With respect to romantic relationship status, 2345 (53%) participants were single; 250 (6%) were dating several people; 1701 (39%) were in an exclusive relationship (dating one person exclusively, engaged, married, or partnered); and the remaining 114 (2%) were married but separated (n = 3) or declined to respond (n = 111). The latter two groups were coded as missing for the analyses.

Cohort effects and attrition analyses

We ran a series of analyses to examine whether there were any cohort effects for the focal study variables and whether those who did not complete the follow-up assessment (n = 1710, 755 male, 951 female, 4 missing sex) differed from those who did complete the follow-up assessment. There was no evidence for cohort effects for any of the focal study variables (parental alcohol problems, conduct problems, positive urgency, dating several people, or alcohol use; all p-values > 0.09; full results available upon request from the first author). The attrition analyses indicated that males were more likely to miss the follow-up assessment than females (OR = 1.42, p < 0.01), that black participants were less likely to miss the follow-up compared to non-black participants (OR = 0.68, p < 0.01), and that Asian participants were less likely to miss the follow-up compared to non-Asian participants (OR = 0.75, p < 0.01). Those with higher conduct problems (OR = 1.22, p = 0.04) and baseline alcohol use (OR = 1.11, p < 0.01) were more likely to miss the follow-up assessment. Those who completed the follow-up assessment did not differ from those who did not complete the follow-up in terms of parental alcohol problems (OR = 1.10, p = 0.16) or positive urgency (OR=1.00, p = 1.00).

Path modeling results

Figure 1 summarizes the results of the path analysis. The full results are shown in Table 2, which includes the coefficients, 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and p-values for the paths shown in Figure 1. This model provided an adequate fit to the data (RMSEA = 0.045) according to the criteria described by Hu and Bentler (1999). We specify the significance associated with each mediational pathway in the boxes inside of the respective mediators in Figure 1. When a variable was a mediator for multiple pathways, the pathway referred to is denoted by superscript.

Table 2. Estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the parameters in Figure 1.

| B | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive urgency | |||

| Parental alcohol problems | 0.14 | [0.09, 0.19] | <0. 01 |

| Conduct problems | |||

| Parental alcohol problems | 0.11 | [0.1, 0.13] | <0.01 |

| Dating several people | |||

| Positive urgency | 0.15 | [0.06, 0.24] | <0.01 |

| Conduct problems | 0.55 | [0.30, 0.79] | <0.01 |

| Parental alcohol problems | −0.02 | [−0.17, 0.13] | 0.78 |

| Change in alcohol use | |||

| Dating several people | 0.10 | [0.04, 0.16] | <0.01 |

| Conduct problems | 0.14 | [0.05, 0.24] | <0.01 |

| Positive urgency | 0.05 | [0.01, 0.10] | 0.01 |

| Parental alcohol problems | 0.01 | [−0.06, 0.07] | 0.85 |

Contrary to our hypothesis, parental alcohol problems did not have a direct association with the likelihood of dating several people (p = 0.78). However, parental alcohol problems did have indirect effects on the likelihood of dating several people via the deviance proneness pathway (indirect effect: B = 0.06, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.035, 0.093]). As hypothesized, parental alcohol problems predicted higher levels of conduct problems (p < 0.01), and higher conduct problems predicted a higher likelihood of dating several people (p < 0.01). Furthermore, dating several people was associated with higher alcohol use (p < 0.01), and was part of an indirect effect from parental alcohol problems to alcohol use via the deviance proneness pathway (indirect effect: B = 0.006, p = 0.01, 95% CI [0.002, 0.012]). Parental alcohol problems also had an indirect effect on the likelihood of dating several people via the positive affect regulation pathway (indirect effect: B = 0.02, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.009, 0.039]). Parental alcohol problems predicted higher positive urgency (p < 0.01), and higher positive urgency predicted a higher likelihood of dating several people (p < 0.01). Furthermore, dating several people was part of an indirect effect from parental alcohol problems to alcohol use via the positive affect regulation pathway (indirect effect: B = 0.002, p = 0.05, 95% CI [0.001, 0.005]). 3

In addition to these hypothesized indirect effects via dating several people, we also statistically controlled for and examined additional direct and indirect effects. Conduct problems and positive urgency had direct effects on alcohol use (p ≤ 0.01), but parental alcohol problems did not (p = 0.85). There was a significant indirect effect from parental alcohol problems→conduct problems→alcohol use (indirect effect: B = 0.02, p < 0.01, 95% CI [0.005, 0.028]) and from parental alcohol problems→positive urgency →alcohol use (indirect effect: B = 0.008, p = 0.02, 95% CI [0.002, 0.015]). In an exploratory analysis we examined potential sex differences using an omnibus test of whether the path coefficients could be equated across males and females. The result of our omnibus test of sex differences was not significant (Wald test of parameter constraints: χ2 (10) = 12.78, p = 0.24). Thus, there did not appear to be sex differences in the effects.

Discussion

The main goals of the current study were to examine whether romantic relationship experiences in emerging adulthood reflect, in part, risk factors for alcohol use and misuse, and whether romantic relationship status accounted for, in part, the associations between these risk factors and subsequent alcohol use. Contrary to our expectations, a parental history of alcohol problems did not have a direct association with dating several people. However, as hypothesized, there was an indirect effect of parental alcohol problems on dating several people via a deviance proneness pathway. Participants whose parents had a history of alcohol problems reported more conduct problems, and in turn higher conduct problems was associated with a greater likelihood of dating several people. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that parental alcohol use disorder is associated with offspring conduct problems (Haber et al., 2010; Sher et al., 1991) as well as previous research that suggests that conduct problems are associated with lower likelihood of involvement in exclusive relationships (Horn et al., 2013; Jaffee et al., 2013).

We also found that romantic relationship status (specifically, dating several people) accounted for, in part, the associations between the deviance proneness pathway variables and subsequent alcohol use. Notably, this effect through romantic relationship status held even after we statistically controlled for the direct effects of parental alcohol problems and conduct problems on alcohol use, as well as the indirect effect of parental alcohol problems→conduct problems→alcohol use. In an earlier report based on the same sample, dating several people was uniquely associated with higher alcohol use and problems compared to being single or being in an exclusive relationship (Salvatore et al., 2014). The current study goes beyond this earlier finding to suggest that this association may be driven, in part, by the fact that individuals on a deviance proneness pathway are also likely to select into romantic relationship experiences associated with increased alcohol use. One implication of this is that it may be important to revisit Zucker and Gomberg's (1986) suggestion to explicitly incorporate salient socioemotional experiences into etiological models of alcohol use and misuse. This is likely to be particularly relevant for understanding continuity in behavior during the emerging adulthood period as individuals move out of the family home and have more autonomy to select into or create social environments that complement their behaviorally disinhibited predispositions (Newman, Caspi, Moffitt, & Silva, 1997; Quinton et al., 1993).

We also found evidence for the positive affect regulation pathway. Participants whose parents had a history of alcohol problems reported higher positive urgency, and in turn higher positive urgency predicted a greater likelihood of dating several people. Our finding that parental alcohol problems is associated with greater positive urgency is consistent with earlier findings from the neuroimaging literature that suggest that impulse control processes may be compromised in the context of heightened emotions for youth with a family history of alcohol use disorder (Cservenka et al., 2014). Furthermore, our finding that positive urgency is associated with a higher likelihood of dating several people similarly maps onto previous findings linking positive emotionality, reward-related neurobiology, and involvement in romantic relationships (Burkett & Young, 2012; Shiner et al., 2002). Finally, dating several people was part of an indirect pathway between the positive affect regulation variables and subsequent alcohol use. Notably, this indirect effect held even after we statistically controlled for the direct effects of parental alcohol problems and positive urgency on alcohol use, as well as the indirect effect of parental alcohol problems→positive urgency→alcohol use.

When considered together, our deviance proneness pathway and positive affect regulation pathway findings provide an interesting example of equifinality (von Bertalanffy, 1968) when it comes to understanding how romantic relationship status fits into etiological models of alcohol use. Equifinality is the idea that the same “state” (in this case, dating several people) can be reached through multiple means. We observe equifinality in that parental alcohol problems appears to indirectly increase the likelihood that one will date several partners via individual differences in conduct problems and positive urgency that are only modestly correlated. Said another way, it appears likely that there are individuals who “arrive” at dating several people via the deviance proneness pathway while others are likely to “arrive” via the positive urgency pathway. This underscores the diverse alcohol-related pathways to this particular romantic relationship status.

Limitations, Implications, and Future Directions

Our results should be interpreted in the context of four main limitations. First, although our sample is racially diverse, it is a college sample, and the results may not generalize to non-college attending emerging adults. For example, college-attending young adults tend to be lower on dimensions of impulsivity (Fromme & Quinn, 2011) but tend to drink more (Slutske et al., 2004) than their non-college attending peers, suggesting that individuals who select into a college environment may differ from the larger population of emerging adults. Second, we rely on self-report, and in some cases, retrospective, measures. The results may be different if independent sources of information (e.g., parents' own reports of their alcohol problems) were available. However, we note that the rates of parental alcohol problems reported by participants using our one-item measures (26%) map well to those reported in the 2001-2002 National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) (21%), which used the highly reliable parental history module of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (Thompson, Lizardi, Keyes, & Hasin, 2008). Third, although our sample as a whole is demographically representative of the diverse undergraduate population from which it is drawn, there was some evidence that individuals with higher levels of conduct problems and alcohol use were less likely to participate in the follow-up. Finally, although our design capitalizes on data collected at two time-points, we do not make causal claims about whether dating several people causes individuals to drink more. Instead, we believe that dating several people lies in pathways of risk for alcohol use in this age group. In other words, we conceptualize dating several people as marker of risk for elevated alcohol use, rather than as part of a causal chain per se.

The results from this work have implications on both theoretical and practical levels. On a theoretical level, our results indicate that romantic relationship status may be important to consider in models of alcohol use, similar to the way that Jessor and Jessor's (1977) PBT considers peer factors. Our results indicate that involvement with multiple dating partners is associated with one's proneness to deviant behavior and increases in alcohol use. Furthermore, the indirect effects from parental alcohol problems to dating several people and alcohol use via deviance proneness and positive affect regulation pathways can be capitalized on in prevention and intervention efforts. Knowing that there are these distinct pathways may be important for tailoring preventive interventions that address the diverse etiologies that may contribute to individuals' selection into (or creation of) environments that are related to higher alcohol use.

Future research aimed at understanding what it means to date several people would increase our understanding of why this particular romantic relationship status is associated with higher alcohol use. For instance, ecological momentary assessment data could be collected to test competing hypotheses about how alcohol is used in the context of dating several people. Do individuals use alcohol to facilitate interactions with their partners? Or do individuals who use more alcohol find themselves exposed to more potential dating partners, and thus see less value in forming an exclusive relationship? Additionally, a conceptual analysis of what emerging adults mean when they indicate that they are dating several people would be valuable for understanding how this relationship status is different from or similar to other romantic relationship experiences outside of commitment/exclusivity (Claxton & van Dulmen, 2013). For example, dating several people may also be associated with sexual hookups. A recent study showed that emerging adult females who report hooking up also tend to be higher in impulsivity and sensation-seeking (Fielder et al., 2013), which are traits also known to be related to higher alcohol use and problems (Magid & Colder, 2007).

Conclusions

In summary, the present study integrates romantic relationship status into extant etiological models of alcohol use/misuse. We examined whether alcohol-related risk factors predicted whether emerging adults' were dating several people, and whether dating several people was in turn related to alcohol use using short-term longitudinal data from a large multi-cohort study. We find evidence that parental alcohol problems have indirect effects on romantic relationship status via a deviance proneness pathway (marked by conduct problems) and a positive affect regulation pathway (marked by positive urgency). In turn, dating several people was associated with alcohol use. These results underscore the idea that familial and individual-level risk factors for alcohol use are also associated with relationship experiences that may support behavioral continuity.

Acknowledgments

Spit for Science: The VCU Student Survey is funded by R37AA011408 (to KSK) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, with support for DMD through K02AA018755 and JES through T32MH20030-14 and F32AA022269. Additional support for the project provided by the National Institutes of Health P20AA107828, Virginia Commonwealth University, and UL1RR031990 from the National Center for Research Resources and National Institutes of Health Roadmap for Medical Research. We would like to thank the VCU students for making this study a success, as well as the many VCU faculty, students, and staff who contributed to the design and implementation of the project. The contents of the paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

Footnotes

A subset of the participants in the study (those in the second and third cohorts, n = 4065) also reported on their alcohol use using continuous frequency and quantity measures (described in Methods) at the fall baseline assessment, which allowed us to compare the grams of ethanol consumed per month estimate—derived from ordinal measures—with a grams of ethanol consumed per month estimate derived from more fine-grained continuous measures of alcohol frequency and quantity. The alcohol use variables derived from the continuous and ordinal variables were highly correlated, r(3828) = 0.67, p < 0.01.

In an earlier report based on a subsample of the participants in the present study, dating several people was distinctively associated with higher alcohol use and problems compared to being single or being in an exclusive relationship (Salvatore et al., 2014). The results of a one-way ANOVA for the larger sample in the present study were consistent with this earlier report, F(2, 4092) = 36.68, p < 0.01. After controlling for sex, age, and race, participants who were dating several people had higher alcohol use (M = 450.43 gethanol/month) compared to those who were single (M = 198.53 gethanol/month) or in an exclusive relationship (M = 179.30 gethanol/month) (p values < 0.01 according to Bonferroni-corrected paired comparisons). Alcohol use did not differ between those who were single and those who were in an exclusive relationship (p = 0.17).

At the suggestion of a reviewer, we examined an alternative model with relationship status as a moderator. We tested whether relationship status moderated the pathways between parental alcohol problems, conduct problems, positive urgency, and changes in alcohol use. As with the primary model presented in Figure 1, relationship status was dummy coded as 0 (Not dating several people: single, exclusive, engaged, married) or 1 (Dating several people). Dating several people moderated the association between high school conduct problems and changes in alcohol use. However, the RMSEA for the model that treated relationship status as a moderator was 0.10, suggesting that it did not provide an adequate fit for the data according to criteria described by Hu and Bentler (1999).

Author Note: Jessica E. Salvatore, Department of Psychology and Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University; Nathaniel S. Thomas, Institute for Drug and Alcohol Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University; Seung Bin Cho, Departments of Psychology and African American Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University; Amy Adkins, Departments of Psychology and African American Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University; Kenneth S. Kendler, Department of Psychiatry and Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics, Virginia Commonwealth University; Danielle M. Dick, Departments of Psychology and African American Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- Arnett J. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. doi: 10.1037//0003-066X.55.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SR, Delevi R, Fincham FD. Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01248.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz KK, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie SH, Hesselbrock VM, Nurnberger JL, Schuckit MA. A new, semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: A report on the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkett JP, Young LJ. The behavioral, anatomical and pharmacological parallels between social attachment, love and addiction. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;224:1–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2794-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158:1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver K, Joyner K, Udry JR. National estimates of adolescent romantic relationships. In: Florsheim P, editor. Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications. Mahawah, New Jersey: Erlbaum; 2003. pp. 23–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, Grant AR, Kelley ML, Miles DL, Santos MT. Parental alcoholism: Relationships to adult attachment in college women and men. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1633–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton SE, van Dulmen MHM. Casual Sexual Relationships and Experiences in Emerging Adulthood. Emerging Adulthood. 2013;1:138–150. doi: 10.1177/2167696813487181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cservenka A, Fair DA, Nagel BJ. Emotional processing and brain activity in youth at high risk for alcoholism. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;1912-1923;38 doi: 10.1111/acer.12435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the urgency traits over the first year of college. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2010;92:63–69. doi: 10.1080/00223890903381825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psycholical Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. US low-risk drinking guideline: An examination of four alternatives. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:1820–1829. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Harford TC. Parental history of alcoholism and probability of marriage. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1992;4:117–129. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(92)90012-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J, Greenbaum PE, Goldman MS. Up close and personal: temporal variability in the drinking of individual college students during their first year. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:155–164. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Nasim A, Edwards AC, Salvatore JE, Cho SB, Adkins A, Kender KS. Spit for Science: Launching a longitudinal study of genetic and environmental influences on substance use and emotional health at a large US university. Frontiers in Genetics. 2014;5:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Calzo JP, Smiler AP, Ward LM. “Anything from making out to having sex”: men's negotiations of hooking up and friends with benefits scripts. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46:414–424. doi: 10.1080/00224490902775801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Walsh JL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Predictors of sexual hookups: A theory-based, prospective study of first-year college women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:1425–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0106-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming CB, White HR, Catalano RF. Romantic relationships and substance use in early adulthood: An examination of the influences of relationship type, partner substance use, and relationship quality. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:153–167. doi: 10.1177/0022146510368930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Quinn PD. Alcohol use and related problems among college students and their noncollege peers: The competing roles of personality and peer influence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:622–632. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber JR, Bucholz KK, Jacob T, Grant JD, Scherrer JF, Sartor CE, Heath A. Effect of paternal alcohol and drug dependence on offspring conduct disorder: Gene-environment interplay. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:652–663. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Iacono WG, McGue M, Patrick CJ. Family transmission and heritability of externalizing disorders - A twin-family study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:922–928. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn EE, Xu YS, Beam CR, Turkheimer E, Emery RE. Accounting for the physical and mental health benefits of entry into marriage: A genetically informed study of selection and causation. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27:30–41. doi: 10.1037/a0029803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KM, Parra GR, Sher KJ, Vungkhanching M. Relation of attachment style to family history of alcoholism and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Lombardi CM, Coley RL. Using complementary methods to test whether marriage limits men's antisocial behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25:65–77. doi: 10.1017/s0954579412000909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R. Problem-behavior theory, psychosocial development, and adolescent problem drinking. British Journal of Addiction. 1987;82:331–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1987.tb01490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, Jessor SL. Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Kearns-Bodkin JN, Leonard KE. Relationship functioning among adult children of alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:941–950. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.941. doi:jsad.2008.69.941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Edwards A, Myers J, Cho SB, Adkins A, Dick D. The predictive power of family history measures of alcohol and drug problems and internalizing disorders in a college population. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 2015a doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Ji J, Edwards AC, Ohlsson H, Sundquist J, Sundquist K. An extended Swedish national adoption study of alcohol use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015b;72:211–218. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Hicks BM, Patrick CJ, Carlson SR, Iacono WG, McGue M. Etiological connections among substance dependence, antisocial behavior, and personality: Modeling the externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:411–424. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.111.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson JH, Taggart-Reedy M, Wilson SM. The effects of perceived dysfunctional family-of-origin rules on the dating relationships of young adults. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2001;23:489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Larson JH, Thayne TR. Marital attitudes and personal readiness for marriage of young adult children of alcoholics. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 1999;16:59–73. doi: 10.1300/J020v16n04_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam DR, Smith GT, Whiteside SP, Cyders MA. The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lynskey MT, Fergusson DM. Childhood conduct problems, attention deficit behaviors, and adolescent alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1995;23:281–302. doi: 10.1007/bf01447558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39. 2004;99 doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, Colder CR. The UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: Factor structure and associations with college drinking. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:1927–1937. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mezquita L, Camacho L, Ibáñez MI, Villa H, Moya-Higueras J, Ortet G. Five-factor model and alcohol outcomes: Mediating and moderating role of alcohol expectancies. Personality and Individual Differences. 2015;74:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Sixth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2011. [Google Scholar]

- Newman DL, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Antecedents of adult interpersonal functioning: Effects of individual differences in age 3 temperament. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:206–217. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton D, Pickles A, Maughan B, Rutter M. Partners, peers, and pathways: Assortative pairing and continuities in conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:763–783. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400006271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore JE, Kendler KS, Dick DM. Romantic relationship status and alcohol use and problems across the first year of college. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:580–589. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Grekin ER, Williams NA. The development of alcohol use disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:493–523. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Walitzer KS, Wood PK, Brent EE. Characteristics of children of alcoholics: Putative risk factors, substance use and abuse, and psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:427–448. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner RL, Masten AS, Tellegen A. A developmental perspective on personality in emerging adulthood: Childhood antecedents and concurrent adaptation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:1165–1177. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.5.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, Scharf M, Livne Y, Barr T. Patterns of romantic involvement among emerging adults: Psychosocial correlates and precursors. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2013;37:460–467. doi: 10.1177/0165025413491371. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Heath AC, Dinwiddie SH, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Dunne MP, Martin NG. Common genetic risk factors for conduct disorder and alcohol dependence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:363–374. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slutske WS, Hunt-Carter EE, Nabors-Oberg RE, Sher KJ, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Heath AC. Do college students drink more than their non-college-attending peers? Evidence from a population-based longitudinal female twin study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:530–540. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RG, Jr, Lizardi D, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Childhood or adolescent parental divorce/separation, parental history of alcohol problems, and offspring lifetime alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98:264–269. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bertalanffy L. General systems theory: Foundations, development, applications. New York: George Braziller; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Whitton SW, Weitbrecht EM, Kuryluk AD, Bruner MR. Committed dating relationships and mental health among college students. Journal of American College Health. 2013;61:176–183. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.773903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Lisansky Gomberg ES. Etiology of alcoholism reconsidered: The case for a biopsychosocial process. American Psychologist. 1986;41:783–793. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.41.7.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]