Abstract

Although the many positive and negative psychosocial consequences of alcohol use are well documented, evidence of the association between prior drinking consequences and subsequent alcohol-related outcomes is mixed. Social learning theory highlights that cognitive appraisals of prior drinking consequences play a crucial intermediate role in the relation of prior drinking consequences with subsequent alcohol-related outcomes. This prospective study was designed to test the mediating effects of subjective evaluations (i.e., perceived valence and controllability) in the association of prior drinking consequences with change in binge drinking and drinking consequences over time. Participants were 171 college students (68% female, 74% White, mean age = 18.95 years [SD = 1.35]) who completed two online surveys, with an average interval of 68 days [SD = 10.22] between assessments. Path analyses of the data did not support mediational effects of perceived valence or controllability of prior drinking consequences on subsequent alcohol-related outcomes. Specifically, greater frequency of negative consequences was associated with lower perceived valence and controllability, and greater frequency of positive consequences was associated with lower perceived controllability of the experienced consequences. However, perceptions of valence and controllability were not in turn associated with subsequent binge drinking and drinking consequences. Instead, greater frequency of positive consequences was directly associated with greater subsequent frequency of binge drinking. Findings highlight the importance of prior positive consequences in the escalation of binge drinking over a short period of time, although this relation may not be accounted for by perceptions of valence and controllability of the prior drinking consequences.

Keywords: subjective evaluations, drinking consequences, alcohol, college, binge drinking

Drinkers experience an array of positive consequences (e.g., reduction of negative affect, enhanced social relationships) and negative consequences (e.g., injury, fights with family and friends) from drinking. According to associative learning theory, consequences following alcohol use should change subsequent drinking behavior (Wasserman & Miller, 1997). While negative drinking consequences may be associated with decreases in subsequent drinking through aversive learning, positive drinking consequences may be associated with increases in subsequent drinking through reward learning. However, extant findings on the association between prior consequences and subsequent alcohol-related outcomes are mixed. For example, negative consequences were associated with the “contemplation” (i.e., envisioning future behavior change), as opposed to the “pre-contemplation” (i.e., no intention of future behavior change), stage of change among non-problematic drinkers (Read, Merrill, Kahler, & Strong, 2007). In contrast, negative consequences were associated with a lower intent to change binge drinking among drinkers mandated to attend alcohol education sessions (Barnett, Goldstein, Murphy, Colby, & Monti, 2006) and with a higher number of planned drinks during the next drinking episode among non-problematic drinkers (Patrick & Maggs, 2008). Further, prospectively, negative consequences were not associated with subsequent binge drinking, after controlling for prior binge drinking (A. Park, Kim, Gellis, Zaso, & Maisto, 2014; A. Park, Kim, & Sori, 2013). Compared to negative consequences, positive consequences have been more consistently associated with subsequent alcohol-related outcomes, although research is limited. Prior positive drinking consequences have been positively associated with frequency and quantity of current alcohol use (Corbin, Morean, & Benedict, 2008), importance of experiencing subsequent positive consequences (Patrick & Maggs, 2008), and increases in binge drinking over time, even after controlling for alcohol outcome expectancies (A. Park et al., 2013).

The sole occurrence of negative and/or positive drinking consequences may not fully explain subsequent alcohol-related outcomes. Subjective evaluations, or cognitive appraisals, of prior drinking consequences may be important intermediates in the relation between the occurrence of drinking consequences and subsequent alcohol-related outcomes. Social learning (cognitive) theory proposes that past experience influences later behavior through intermediate cognitive factors of the experience (Bandura, 1977). When applied to alcohol consumption, cognitive appraisals of past drinking consequences may affect subsequent drinking behavior (Maisto, Carey, & Bradizza, 1999). Although the association between subjective evaluations of expected alcohol outcomes and subsequent alcohol-related outcomes has been well documented (e.g., Fromme & D’Amico, 2000; Fromme, Stroot, & Kaplan, 1993), subjective evaluations of prior drinking consequences have only been recently examined, as described below.

Subjective evaluations of drinking consequences include an individual’s perceived valence of experienced consequences (i.e., positivity versus negativity). For negative drinking consequences, the more frequently drinkers experience negative consequences, the more they may “normalize” negative consequences as part of the drinking experience and thereby perceive them to be less aversive (i.e., increasing their perceived positive valence). Thus, consequences classified as “negative” by researchers may no longer be perceived as negative by drinkers. This less aversive/more positive valence of prior negative consequences may lead drinkers to continue drinking, thereby experiencing more negative drinking consequences; drinkers may further increase their subsequent drinking to experience additional, positive drinking consequences, given that the same drinking behavior brings positive as well as negative consequences. Indeed, drinkers who experienced more negative drinking consequences rated their prior consequences more positively (Gaher & Simons, 2007; Lee, Geisner, Patrick, & Neighbors, 2010; Logan, Henry, Vaughn, Luk, & King, 2012), with the exception of one recent study in which a greater number of prior negative consequences was associated with more negative valence (Merrill, Read, & Colder, 2013b). In turn, more positive valence of prior negative drinking consequences has been associated with greater subsequent alcohol use quantity and negative drinking consequences in all three prospective studies with follow-up durations ranging from one week to six months (Lee et al., 2010; Merrill, Read, & Barnett, 2013a; Merrill, Read, & Colder, 2013b). The only extant mediation analysis involving negative consequences showed that perceived valence of prior negative consequences mediated the association between prior negative consequences and subsequent weekly drinking (but not subsequent negative consequences), with more positive valence associated with greater subsequent drinking (Merrill, Read, & Colder, 2013b). Therefore, a higher frequency of prior negative drinking consequences may lead to increases in subsequent drinking through more positive evaluation of prior negative consequences.

Similarly, for positive drinking consequences, as drinkers experience more positive consequences, they may perceive those consequences to be more positive, because drinkers, particularly in late adolescence and young adulthood, tend to have a propensity toward stimulating and risky experiences (MacPherson, Magidson, Reynolds, Kahler, & Lejuez, 2010). Drinkers may then increase their subsequent drinking to experience additional, positive drinking consequences, thereby increasing their experience of subsequent positive drinking consequences. Indeed, college students who experienced more positive consequences have rated their consequences more positively (Logan et al., 2012). In turn, greater perceived positive valence of potential positive drinking consequences has been associated with greater subsequent alcohol use after one semester, controlling for previous alcohol use (Patrick & Maggs, 2011). However, this otherwise well-designed study assessed only potential future drinking consequences, not actual experienced drinking consequences. Thus, the relation of perceived valence of prior positive drinking consequences to subsequent drinking behavior and positive drinking consequences remains unknown.

In addition to perceived valence, perceived controllability of drinking consequences may also influence subsequent alcohol use. Attribution theory (Weiner, 1985) proposes that individuals interpret the causes of their past behaviors’ outcomes, including their ability to control the outcomes, and these attributions influence individuals’ subsequent behavior. The more frequently drinkers experience drinking consequences, the more they may become accustomed to diverse outcomes of their drinking behavior and thus perceive that they can control the alcohol-related outcomes. Greater perceived ability to control their alcohol-related consequences (regardless of the perceived valence of the outcomes) may then promote increased subsequent drinking and in turn experience of both positive and negative drinking consequences, as drinkers perceive themselves able to obtain positive consequences while limiting negative consequences. To our knowledge, no research has examined the impact of perceived controllability of prior drinking consequences on subsequent alcohol-related outcomes. Existing, albeit limited, research suggests an impact of perceived controllability of possible (rather than prior) drinking consequences on drinking behavior. Specifically, current drinkers have rated possible alcohol outcomes (e.g., dizziness, talkative, depressed mood) as more controllable than former drinkers (Nagoshi, 1999). Also, greater perceived behavioral control over drunk driving was associated with greater intention to engage in the behavior (Chan, Wu, & Hung, 2010). Research on perceived control over alcohol use (rather than drinking consequences) suggests similar associations of greater perceived control over drinking with greater subsequent binge drinking (Elliott & Ainsworth, 2012), although a null finding has also been reported (Norman, Armitage, & Quigley, 2007). Further, perceived control over behavior (including both risky and health-promoting) was found to have a small, positive association with prospective behavior in a meta-analysis (Armitage & Conner, 2001). Based on this broad literature, the current study tested whether perceived controllability of prior drinking consequences influences subsequent drinking behavior and experience of drinking consequences.

The purpose of this study was to examine whether subjective evaluations of drinking consequences account for the relations between experience of prior drinking consequences and subsequent alcohol outcomes. Specifically, the current study examined whether two dimensions of subjective evaluations (i.e., perceived positive valence and controllability) mediated the relationship of the occurrence of negative and positive drinking consequences with subsequent binge drinking and drinking consequences over time using data from a short-term two-wave prospective study of college students. It was hypothesized that greater frequency of negative and positive drinking consequences would be associated with higher perceived valence and controllability, both of which in turn would be associated with an increase in binge drinking and drinking consequences over time.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Data were obtained from a two-wave short-term prospective study (Author). Participants were 171 introductory psychology students who were at least 18 years of age and reported consuming at least one alcoholic drink in the past 30 days. Participants were, on average, 18.95 years old (SD = 1.35, range = 18 – 28), 68% female, 98% full-time students, 15% fraternity/sorority members, 52% first-year students, and 74% White (along with 12% Asian, 7% Black, 7% multiracial, and 1% American Indian). Participants provided electronic informed consent and completed two online surveys with an average interval of 68 days (SD = 10.22) between assessments at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2). Of the 171 students who participated in the T1 survey, 157 (92%) students also participated in the T2 survey. Students were compensated for participation with credit for the research component of the introductory psychology course. All study measures and procedures were reviewed and approved by the university’s institutional review board.

Independent-sample t-tests for continuous T1 study variables (i.e., T1 binge drinking, T1 frequencies of negative and positive consequences, perceived valence and controllability of negative and positive consequences) and a χ2 test for the categorical T1 study variable (i.e., gender) were conducted to compare the participants who completed both surveys (completers; n = 157) with those who participated in the T1 survey only (attriters; n = 14). Attriters did not differ significantly from completers on any of these variables at p < .05. As described in Data Analytic Strategies, full information maximum likelihood estimation was used to deal with missing data, rather than dropping the missing data from attriters.

Measures

Gender

An item was administered to assess gender (0 = female and 1 = male) at T1, which was included as a covariate in all analyses.

Binge drinking

An item was administered at T1 and T2 to measure frequencies of binge drinking occasions during the past 2 months: “In the past 2 months, how often did you have 5 (males) or 4 (females) or more drinks containing any kind of alcohol within a two-hour period?” (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2004) The time frame of the original item was adapted to conform to the 2-month follow-up period of the current study. The definition of a drink was given to participants as a 12-oz can or bottle of beer or wine cooler, a 5-oz glass of wine, or a 1.5-oz shot of liquor straight or in a mixed drink. Participants responded to the item based on a 9-point scale (0 = I did not have 5/4 or more drinks within a two-hour period in the past 2 months, 1 = Once in the past 2 months, 2 = Once a month [twice in the past 2 months], 3 = Twice to three times a month [less than once a week], 4 = Once or twice a week, 5 = Three to four times a week, 6 = Five to six times a week, 7 = Nearly every day, and 8 = Every day). Participants’ reports of any binge drinking in the past 2 months (83% at T1 and 87% at T2) were comparable to previous studies of college students over the past 90 days (74%; Read, Beattie, Chamberlain, & Merrill, 2008) and over the past 30 days (60%; Gaher & Simons, 2007).

Frequency of negative drinking consequences

The 23-item Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (White & Labouvie, 1989) was administered at T1 and T2 to measure negative drinking consequences experienced during the past 2 months. Time frames and response options of the original scale were adapted to the past 2 months to conform to the 2-month follow-up time period of the current study. Participants responded to each item on a 7-point scale (0 = Never in the past 2 months, 1 = Once in the past 2 months, 2 = Twice in the past 2 months, 3 = Three times in the past 2 months, 4 = Four times in the past 2 months, 5 = Five times in the past 2 months, and 6 = Six times or more in the past 2 months). Sum scores at T1 (Cronbach’s α = .87) and T2 (Cronbach’s α = .94) were used for the current analyses. Although rates of negative consequences in the current sample are not directly comparable to previous research using a one-year time frame due to the current study’s shorter 2-month time frame, reports of any negative consequences experienced in the past 2 months in the current study (95% at T1 and 90% at T2) are comparable to previous reports over the past year (84%; Gaher & Simons, 2007).

Frequency of positive drinking consequences

The 14-item Positive Drinking Consequences Questionnaire (Corbin et al., 2008) was administered at T1 and T2 to assess the frequency of positive drinking consequences experienced during the past 2 months (e.g., “Told a funny story or joke and made others laugh,” “I stood up for a friend or confronted someone who was in the wrong,” “The intensity of a sexual experience was enhanced”). Consistent with the assessment of negative drinking consequences, time frames and response options of the original scale were adapted to the past 2 months, and participants responded to each item on the same 7-point scale that was used for the negative drinking consequence items. Sum scores at T1 (Cronbach’s α = .86) and T2 (Cronbach’s α = .87) were used for the current analyses.

Perceived valence of negative and positive drinking consequences

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (White & Labouvie, 1989) and the Positive Drinking Consequences Questionnaire (Corbin et al., 2008) were modified to assess perceived valence of experienced negative and positive drinking consequences, respectively. For each consequence reported at least once in the past 2 months at T1, participants were asked “How positive or negative was the experience?,” consistent with the methodology of previous research examining perceived valence of past-year negative drinking consequences (Mallett, Bachrach, & Turrisi, 2008). Participants responded to each item on a 5-point scale (−2 = very negative, −1 = negative, 0 = neutral, 1 = positive, and 2 = very positive). Valence ratings for all experienced consequences on the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index were averaged to create a single variable of the perceived valence of prior negative drinking consequences (Cronbach’s α = .93), with higher scores indicating more positive valence. Valence ratings for all experienced consequences on the Positive Drinking Consequences Questionnaire were averaged to create a single variable of the perceived valence of prior positive drinking consequences (Cronbach’s α = .84), with higher scores indicating more positive valence.

Perceived controllability of negative and positive drinking consequences

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (White & Labouvie, 1989) and the Positive Drinking Consequences Questionnaire (Corbin et al., 2008) were also modified to assess perceived controllability of experienced negative and positive drinking consequences, respectively. For each consequence they reported at least once in the past 2 months at T1, participants were asked “How much control do you have over whether you experience each of the below events from drinking or not?” Participants responded to each item on a 5-point scale (0 = no control at all, 1 = slightly in control, 2 = somewhat in control, 3 = moderately in control, and 4 = very much in control). Controllability ratings for all experienced consequences on the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index and on the Positive Drinking Consequences Questionnaire were averaged to create variables of the perceived controllability of prior negative drinking consequences (Cronbach’s α = .95) and prior positive drinking consequences (Cronbach’s α = .92), respectively. Higher scores indicated greater perceived controllability of prior consequences.

Data Analytic Strategies

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among all study variables were conducted in SPSS, Version 21. As main analyses, path analysis was conducted using Mplus, Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012), a structural equation modeling software package. Path analysis is an extension of multiple regression, which allows for estimation of complex relationships among multiple predictors and outcomes in a single model simultaneously.

Maximum Likelihood estimation with Robust standard error (MLR) was specified to deal with non-normally distributed variables (defined as skewness and kurtosis values more extreme than ±1): T1 frequency of negative consequences (skewness = 1.72; kurtosis = 3.02), T2 frequency of negative consequences (skewness = 2.43; kurtosis = 6.35), valence of positive consequences (skewness = −1.08; kurtosis = 2.70), and T2 frequency of binge drinking (skewness = −0.27; kurtosis = −1.17). Maximum likelihood estimation also dealt with missing data in endogenous variables (i.e., T1 mediating and T2 outcome variables in our models) by determining the parameters that maximized the probability of the sample data on the basis of all the available data without imputing missing data (Graham, Cumsille, & Elek-Fish, 2003). In addition to missing data in the T2 variables among students who did not complete the T2 survey (n = 14), there was also missing data in two proposed mediators: valence of positive consequences (n = 2) and valence of negative consequences (n = 9). There was no missing data in any of our predictors or covariates.

T2 frequencies of binge drinking, negative consequences, and positive consequences were specified as count outcomes, given that they were characterized by discrete, non-negative integer values representing a number of occurrences. T2 frequency of binge drinking was modeled with a Poisson distribution (M = 2.50; variance = 2.25; dispersion parameter = 0.00, p > .05), while both T2 frequency of negative consequences (M = 12.10; variance = 243.54; dispersion parameter = 0.60, p < .01) and T2 frequency of positive consequences (M = 17.29; variance = 154.26; dispersion parameter = 0.19, p < .001) were modeled with a negative binomial distribution due to significant over-dispersion (Hilbe, 2011). Monte Carlo integration was used to model the influence of continuous mediators (with missing data) on count outcomes (Muthén & Muthén, 2012, pp. 470–472). Residual error covariances between count outcomes were modeled by specifying a latent variable that influenced both outcomes (Muthén & Muthén, 2012, p. 582). We note that ancillary analyses not specifying T1 frequencies of binge drinking and drinking consequences as count outcomes yielded the same pattern of significance of both total and mediating effects as the results presented below.

Standardized regression coefficients are presented for paths with continuous outcomes (i.e., valence and controllability of prior consequences), and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) are presented for paths with count outcomes (i.e., T2 frequencies of binge drinking and consequences) as effect size measures. IRRs measure the percent increase/decrease in the outcome with a one-unit increase in the predictor/covariate, with an IRR of 1 indicating no change in the outcome with a one-unit increase in the predictor/covariate. For example, an IRR of 1.02 indicates a 2% increase in the outcome with a one-unit increase in the predictor/covariate.

We estimated auto-regressive cross-lagged path models of the reciprocal relationships between binge drinking and frequency of drinking consequences over time (unmediated models), as well as potential mediating influences of subjective evaluations of drinking consequences on these reciprocal relationships (mediated models). An unmediated and mediated model were estimated separately for negative and positive consequences, resulting in a total of four path models. The effect of male gender was controlled for in all models, due to its potential influences on alcohol consumption and consequences (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004).

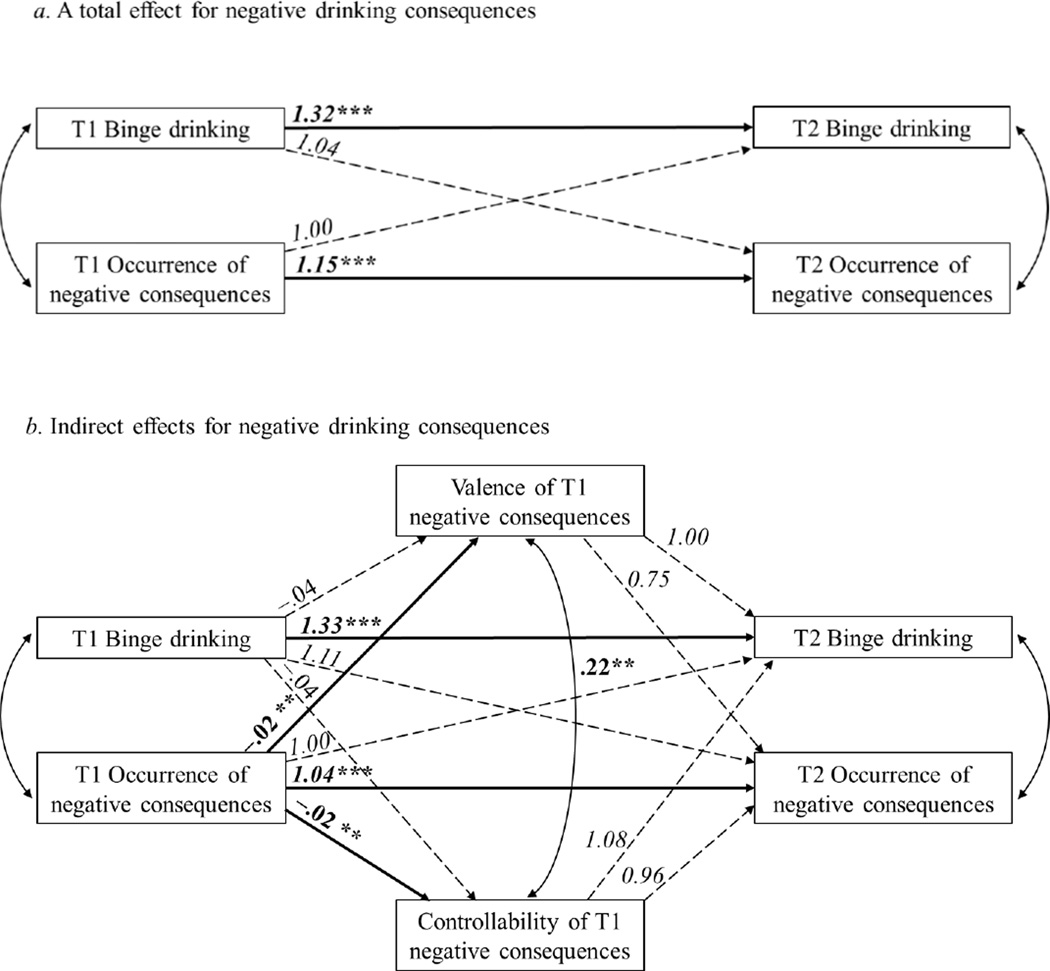

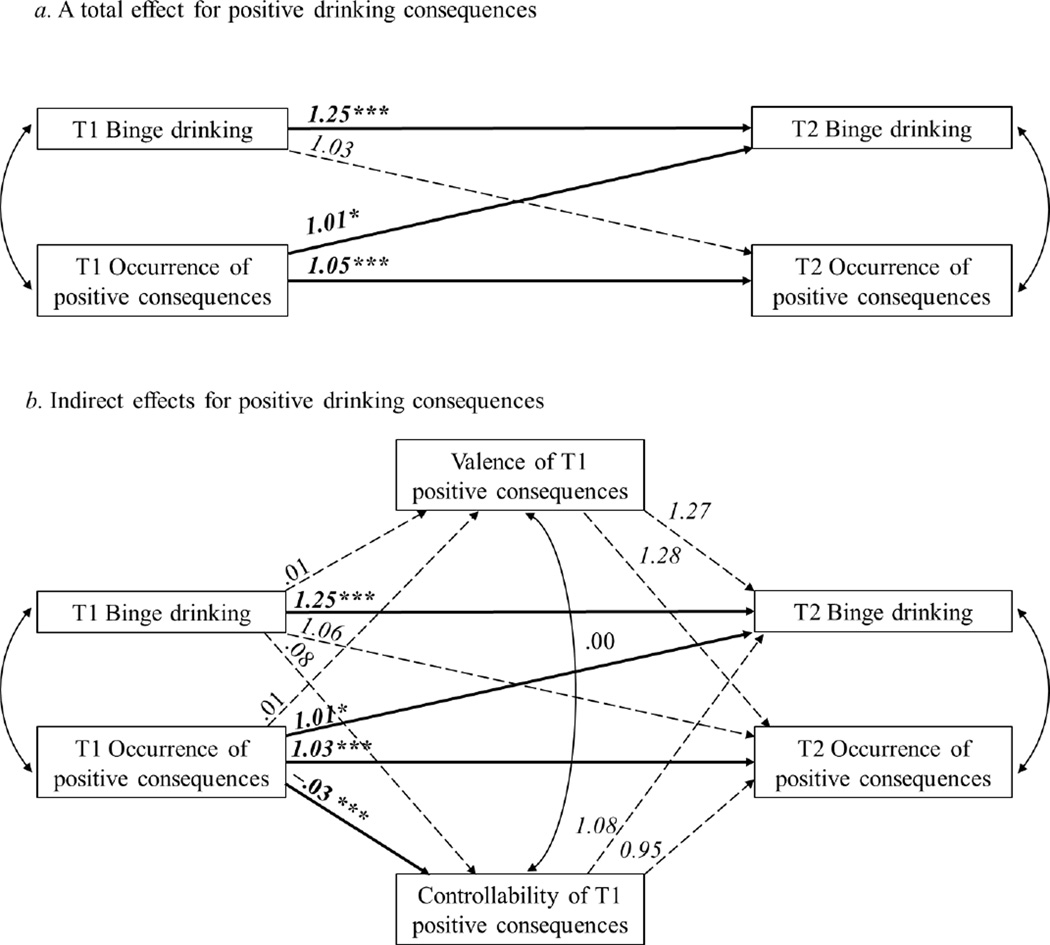

The top panels of Figures 1 and 2 show the path diagrams of the two unmediated models to test the total effect of T1 frequency of drinking consequences on T2 binge drinking and drinking consequences (after controlling for T1 binge drinking and gender), without consideration of potential cognitive mediators (i.e., Path c; total effect, without mediators). The bottom panel of Figures 1 and 2 show the path diagrams of the two mediational models to test the mediating effect of T1 subjective evaluations of drinking consequences (after controlling for T1 binge drinking and gender). Paths from T1 frequencies of binge drinking and drinking consequences to T1 perceived valence and controllability represent the paths from the predictors to the proposed mediators (Path a). Paths from T1 perceived valence and controllability to T2 binge drinking and drinking consequences represent the paths from the proposed mediators to the outcomes (Path b). Paths from T1 predictors to T2 outcomes through a T1 mediator represent the indirect (i.e., mediated) effect, which is calculated by multiplying the unstandardized estimates of the two paths (Path a * Path b); in analyses with count outcomes, estimation of the mediating effect as the product of the two paths (a*b) has been shown to be less biased than estimation through alternative methods (e.g., c-c’; Coxe & MacKinnon, 2010). Paths from T1 predictors to T2 outcomes represent the direct effect after accounting for the indirect effect through the mediators (Path c’; direct effect). Because the Sobel test has been shown to lack in power (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Virgil, 2002) and bootstrapping is not available with Monte Carlo numerical integration (Muthén & Muthén, 2012, p. 548), confidence intervals of the indirect effects were computed with the Monte Carlo method, which has been shown to perform comparatively to other widely-used methods of confidence interval estimation for indirect effects (Preacher & Selig, 2012). Significance testing was performed using an online Monte Carlo calculator (Selig & Preacher, 2008) that generated 95% confidence intervals of the indirect effects based on 20,000 resamples; confidence intervals (CI) that did not include zero indicated significant mediation.

Figure 1.

Standardized regression coefficients (for paths predicting continuous outcomes, including valence and controllability) and incidence rate ratios (for paths predicting count outcomes, including T2 frequencies of binge drinking and negative consequences; italicized) from two path analysis models of negative drinking consequences. The top panel (a) shows results from a model testing the total effect, or the reciprocal association between binge drinking and negative consequences over time without consideration of potential cognitive mediators. The lower panel (b) shows results from a model testing mediating roles of subjective evaluations (i.e., perceived valence and controllability) on the reciprocal association between frequency of negative consequences and binge drinking over time. Bolded coefficients and lines indicate significant paths at p < .05; unbolded coefficients and dotted lines indicate nonsignificant paths at p ≥ .05. The effects of gender on mediators and outcomes were controlled for in both models (paths are not shown for simplicity). T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Figure 2.

Standardized regression coefficients (for paths predicting continuous outcomes, including valence and controllability) and incidence rate ratios (for paths predicting count outcomes, including T2 frequencies of binge drinking and positive consequences; italicized) from two path analysis models of positive drinking consequences. The top panel (a) shows results from a model testing the total effect, or the reciprocal association between binge drinking and positive consequences over time without consideration of potential cognitive mediators. The lower panel (b) shows results from a model testing mediating roles of subjective evaluations (i.e., perceived valence and controllability) on the reciprocal association between frequency of positive consequences and binge drinking over time. Bolded coefficients and lines indicate significant paths at p < .05; unbolded coefficients and dotted lines indicate nonsignificant paths at p ≥ .05. The effects of gender on mediators and outcomes were controlled for in both models (paths are not shown for simplicity). T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Means (with standard deviations in parentheses) and bivariate Pearson correlation coefficients of study variables are presented in Table 1. On average, participants reported binge drinking about twice per month at both assessment points. Participants reported experiencing more positive drinking consequences than negative drinking consequences at both assessment points, despite more items on the negative consequences measure (range of possible scores = 0 – 138) than the positive consequences measure (range of possible scores = 0 – 84).

Table 1.

Means (and Standard Deviations) of All Study Variables and Their Bivariate Correlation Coefficients

| M (SD) | r | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | ||

| 1. Male gender | 32% | — | |||||||||

| 2. T1 Binge drinking frequency | 2.71 (1.72) | .12 | — | ||||||||

| 3. T1 Negative consequences, frequency | 11.43 (11.61) | .06 | .37*** | — | |||||||

| 4. T1 Negative consequences, valence | −0.34 (0.77) | .09 | −.14 | −.25** | — | ||||||

| 5. T1 Negative consequences, controllability | 3.05 (0.85) | .19* | −.14 | −.27*** | .28*** | — | |||||

| 6. T1 Positive consequences, frequency | 21.20 (12.94) | .11 | .53*** | .68*** | −.22** | −.23** | — | ||||

| 7. T1 Positive consequences, valence | 0.87 (0.56) | .07 | .07 | −.13 | .38*** | .06 | .09 | — | |||

| 8. T1 Positive consequences, controllability | 2.80 (0.81) | .17* | −.04 | −.19* | .31*** | .74*** | −.28*** | −.01 | — | ||

| 9. T2 Binge drinking frequency | 2.50 (1.50) | .15 | .55*** | .19* | −.12 | −.03 | .43*** | .17* | .02 | — | |

| 10. T2 Negative consequences, frequency | 12.10 (15.61) | .13 | .22** | .40*** | −.28** | −.14 | .39*** | −.04 | −.15 | .22** | — |

| 11. T2 Positive consequences, frequency | 17.29 (12.42) | .16 | .35*** | .42*** | −.14 | −.14 | .58*** | .18* | −.17* | .44*** | .69*** |

Note. N = 157 – 171 due to missing data.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Negative Drinking Consequences

In regards to the total effect (top panel of Figure 1), there were significant auto-regressive effects, with T1 negative consequences positively associated with T2 negative consequences (b = .04, IRR = 1.15, p < .001) and T1 binge drinking positively associated with T2 binge drinking (b = .28, IRR = 1.32, p < .001). However, after accounting for these auto-regressive effects (and gender), there were no significant cross-lagged associations; T1 negative consequences were not associated with T2 binge drinking and T1 binge drinking was not associated with T2 negative consequences.

In regards to the indirect/mediating effects (bottom panel of Figure 1), the mediational model for negative drinking consequences was tested despite the lack of a significant total effect, because mediation can occur in the absence of a significant total effect if inclusion of a mediator strengthens the association between the predictor and outcome (i.e., suppression; MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000). The effect of T1 negative consequences on T2 binge drinking was mediated by neither perceived valence (point estimate = 0.000; 95%CI [−0.001,0. 003]) nor perceived controllability (point estimate = −0.001; 95% CI [−0.003,0.001]) of the negative consequences. Specifically, although greater T1 frequency of negative consequences was associated with less positive valence (b = −0.02, β = −.02, p = .007) and lower controllability (b = −0.02, β = −.02, p = .003) of the prior consequences, perceived valence and controllability were not significantly associated with T2 frequencies of binge drinking or negative drinking consequences (after controlling for T1 binge drinking and gender). We note that supplementary analyses using the number of negative consequences experienced (rather than the frequency of negative consequences) yielded the same pattern of nonsignificant mediation effects.

Positive Drinking Consequences

In regards to the total effect (top panel of Figure 2), there were significant auto-regressive effects, with T1 positive consequences positively associated with T2 positive consequences (b = 0.03, IRR = 1.05, p < .001) and T1 binge drinking positively associated with T2 binge drinking (b = 0.23, IRR = 1.25, p < .001). After accounting for these auto-regressive effects (and gender), there was also a significant, positive cross-lagged association between T1 positive consequences and T2 binge drinking (b = .01, IRR = 1.01, p = .016), indicating that greater experience of positive consequences at T1 was associated with greater binge drinking over time. However, no significant cross-lagged association between T1 binge drinking and T2 positive consequences was found, indicating that greater frequency of binge drinking at T1 was not associated with change in experience of positive consequences over time.

In regards to the indirect/mediating effects (bottom panel of Figure 2), the effect of T1 positive consequences on T2 binge drinking was mediated by neither perceived valence (point estimate = 0.001; 95%CI [−0.001, 0.002]) nor perceived controllability (point estimate = −0.002; 95%CI [−0.004,0.001]) of the positive consequences. Specifically, although greater T1 frequency of positive consequences was associated with lower controllability (b = −0.02, β = − .03, p < .001), but not valence, of the prior consequences, greater perceived controllability was not in turn associated with greater T2 frequencies of binge drinking or positive drinking consequences (after controlling for T1 binge drinking and gender). We note that supplementary analyses using the number of negative consequences experienced (rather than the frequency of negative consequences) yielded the same pattern of nonsignificant mediation effects.

Discussion

This study extended the literature by examining whether subjective evaluations (i.e., perceived valence and controllability) of prior drinking consequences explained, or mediated, the prospective relationships between drinking consequences and binge drinking. Findings demonstrated that neither perceived valence nor controllability mediated the relationship between prior frequency of drinking consequences and subsequent alcohol outcomes. Greater frequency of negative consequences was associated with lower perceived valence and controllability, and greater frequency of positive consequences was associated with lower perceived controllability of the prior consequences. However, these perceptions were not in turn associated with subsequent binge drinking over 2 months. The lack of mediating effects suggests that cognitive appraisals of prior drinking consequences may not account for the escalation of binge drinking behavior over a short period of time, although replication is needed.

For evaluation of negative drinking consequences, our findings suggest that students who experienced negative consequences more frequently rated them as more negative. This result is in line with findings of Merrill and colleagues (2013b) but contradicts other findings in which students experiencing more frequent negative consequences rated them as more positive (Gaher & Simons, 2007; Lee et al., 2010; Logan et al., 2012). These mixed findings in the literature may be due to differences in sample characteristics, specifically levels of alcohol use. Both the current study and the study by Merrill and colleagues (2013b) sampled students from universities in the Northeastern U.S. with primarily White students, both characteristics associated with heavier drinking in college (Wechsler, Lee, Kuo, & Lee, 2000). In contrast, studies by Lee and colleagues (2010) and Logan and colleagues (2012) sampled from universities in the Pacific Northwestern U.S. with a substantial proportion of Asian students, both characteristics associated with lighter drinking in college (Wechsler et al., 2000). Heavier drinkers with a history of more frequent negative consequences may perceive such consequences as more negative than lighter drinkers. Indeed, students who experienced negative drinking consequences more often perceived them to be more negative than students who experienced negative consequences less often (Logan et al., 2012). In addition, our findings suggest that students who experienced more frequent negative consequences rated them as less controllable. The current study was the first to examine perceived controllability of actual, prior drinking consequences, although there was a previously reported positive association of drinking status with perceived controllability of possible drinking consequences (Nagoshi, 1999). Students may predict themselves to have more control over possible alcohol-related outcomes, while being more accurate in their evaluation of the controllability of prior alcohol-related consequences they actually experienced. Although replication is needed, the current findings suggest that drinkers with more negative drinking consequences may accurately perceive their lack of control over at least some of their drinking experiences; as their frequency of drinking consequences increases, their ability to control these outcomes may decrease.

Experience of negative consequences was not associated with subsequent binge drinking either directly or indirectly through subjective evaluations, after controlling for prior binge drinking and gender. This lack of a direct effect suggests that experience of negative consequences may not discourage future binge drinking among college students. Rather than being deterred by negative consequences, students may instead increase their binge drinking over time to “chase” positive consequences that also occur during drinking episodes. Indeed, students have reported that negative consequences would not influence their future drinking as much as positive consequences (C. L. Park, 2004), and experience of more negative consequences than usual was not associated with plans to drink during the upcoming week (Patrick & Maggs, 2008). Also, our prior study found that prior negative drinking consequences were not associated with change in binge drinking over a 2-month period (Author). However, another study found a significant effect of prior negative consequences on change in binge drinking over one year (Read, Wardell, & Bachrach, 2013). These findings suggest that experience of negative consequences may have a more apparent impact on binge drinking after longer follow-up intervals as students mature and/or gain more drinking experiences. Regarding the lack of indirect effects through subjective evaluations, these results contradict a finding from the only existing mediational analysis by Merrill and colleagues (2013b), which found that students who perceived their prior negative drinking consequences as more positive had greater subsequent weekly drinking quantity. Merrill and colleagues (2013b) examined effects of the single negative consequence rated as most negative, severe, and/or aversive in the past week, while the current study examined the average perceived valence of all consequences experienced during the past 2 months. Future studies designed to test differences in subsequent drinking outcomes based on perceived valence of negative drinking consequences as a function of follow-up intervals and measurements of valence would be of value.

For evaluation of positive drinking consequences, students who experienced consequences more frequently rated these consequences as less controllable. The finding of an inverse relation between frequency of prior drinking consequences and perceived controllability was unexpected, suggesting that the more frequently drinkers experience positive consequences, the less they view such consequences as controllable. Similar to associations with negative consequences, drinkers with more positive drinking consequences may accurately perceive their lack of control over some of their drinking experiences. In addition, students who experienced positive consequences more frequently did not rate these consequences as more positive. The lack of association between frequency of prior positive consequences and perceived valence contradicts previous research (Logan et al., 2012), which suggests that the more frequently drinkers experience positive drinking consequences the more they may view such consequences as desirable. Such mixed findings may be due to the heavier-drinking nature of the current sample, as compared to the sample of Logan and colleagues (2012), as described above. Heavier-drinking students likely experience more frequent positive as well as negative drinking consequences, and more frequent experience of negative consequences may reduce their positive evaluations of any experienced drinking outcomes.

Our results indicate that students’ perceptions of valence and controllability about their prior positive consequences were not associated with subsequent change in binge drinking. This finding suggests that, while perceived valence of possible, positive consequences (which may be closely related to positive alcohol outcome expectancies) may be associated with subsequent drinking (Patrick & Maggs, 2011), perceived valence of actual, prior consequences may not drive changes in binge drinking over time. Students with more frequent experience of positive drinking consequences showed greater subsequent frequency of binge drinking, regardless of their perceptions of the valence and controllability of these consequences. Escalations in binge drinking following positive consequences may instead be driven by other subjective evaluations, such as acceptability, likelihood, or severity of prior drinking consequences, which have been associated with alcohol use (Foster, Neighbors, & Krieger, 2015; Gaher & Simons, 2007; Merrill, Read, & Barnett, 2013a; Merrill, Read, & Colder, 2013b) although their mediating roles in the impact of positive consequences on subsequent drinking are yet to be examined. Additionally, rather than a mediating role of subjective evaluations, potential third variables (i.e., novelty-seeking, subjective norms) may impact both experience of positive consequences and binge drinking. Future studies are needed to examine diverse subjective evaluations of prior drinking consequences and their associations with other individual differences as well as subsequent alcohol outcomes.

The current findings have implications for intervention and prevention efforts to curb binge drinking by college students. Our findings suggest that experience of positive, rather than negative, drinking consequences is associated with increases in subsequent binge drinking over a short time period. Personalized feedback interventions, however, often attempt to reduce drinking with a focus on the negative drinking consequences experienced by students (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & DeMartini, 2007; Cronce & Larimer, 2011; White, 2006), and such interventions have had limited efficacy in reducing college student drinking (Larimer & Cronce, 2002). Instead, personalized feedback interventions could focus on identifying students’ positive drinking consequences, helping college students achieve similar positive outcomes from alternative activities.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First, the current study was based upon a convenience sample of college students taken from a private Northeastern university, who were mainly White and first-year students. Generalizability of study findings to other samples needs to be demonstrated empirically. Second, binge drinking was measured at only two time points, with an average interval of 68 days between assessments. Although the current examination of prospective relationships between experience of drinking consequences, subjective evaluations, and alcohol use represents an important addition to existing literature, research following the longitudinal trajectories of alcohol use is needed to model these mediational relationships over a longer period of time. Similar to our finding, a 7-year prospective study of a community sample of adolescents and young adults also found that rating negative drinking consequences as more bothersome was not associated with subsequent alcohol use (White & Ray, 2014). However, future studies need to examine whether relationships between subjective evaluations and subsequent alcohol use differ across college and community samples and between shorter- and longer-term follow-up. Third, experience of drinking consequences and subjective evaluations were measured concurrently. Although subjective evaluations of actual drinking consequences are, by nature, subsequent to the drinking consequences, prospective event-level measurements are needed in future research to assess subjective evaluations of drinking consequences in the same drinking experience prospectively. Finally, students rated their prior drinking consequences on a single dimension of valence (i.e., negative to positive), which could not account for consequences perceived as both positive and negative. Despite its limitations, our findings highlight the importance of prior positive drinking consequences in the escalation of binge drinking over a short period of time, although different mechanisms may underlie the relation between prior alcohol-related consequences and escalation of binge drinking over time.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by NIH grant R15 AA022496 to Aesoon Park.

Contributor Information

Michelle J. Zaso, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University

Aesoon Park, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University.

Jueun Kim, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University.

Les A. Gellis, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University

Hoin Kwon, Department of Counseling Psychology, Jeonju University.

Stephen A. Maisto, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University

References

- Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2001;40(4):471–499. doi: 10.1348/014466601164939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett NP, Goldstein AL, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. “I’ll Never Drink Like That Again”: Characteristics of alcohol-related incidents and predictors of motivation to change in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(5):754–763. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey MP, DeMartini KS. Individual-level interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analytic review. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2469–2494. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan DCN, Wu AMS, Hung EPW. Invulnerability and the intention to drink and drive: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2010;42(6):1549–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Morean ME, Benedict D. The Positive Drinking Consequences Questionnaire (PDCQ): Validation of a new assessment tool. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(1):54–68. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxe S, MacKinnon DP. Abstract: Mediation analysis of poisson distributed count outcomes. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2010;45(6):1022–1022. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2010.534375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronce JM, Larimer ME. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Research & Health. 2011;34(2):210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MA, Ainsworth K. Predicting university undergraduates’ binge-drinking behavior: A comparative test of the one- and two-component theories of planned behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37(1):92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DW, Neighbors C, Krieger H. Alcohol evaluations and acceptability: Examining descriptive and injunctive norms among heavy drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;42:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, D’Amico EJ. Measuring adolescent alcohol outcome expectancies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14(2):206–212. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot EA, Kaplan D. Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5(1):19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gaher RM, Simons JS. Evaluations and expectancies of alcohol and marijuana problems among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(4):545–554. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Cumsille PE, Elek-Fish E. Methods for handling missing data. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Research Methods in Psychology. New York, NY: Wiley; 2003. pp. 446–454. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Negative binomial regression. 2. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Cronce JM. Identification, prevention and treatment: A review of individual-focused strategies to reduce problematic alcohol consumption by college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol Supplement. 2002;(14):148–163. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Geisner IM, Patrick ME, Neighbors C. The social norms of alcohol-related negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(2):342–348. doi: 10.1037/a0018020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan DE, Henry T, Vaughn M, Luk JW, King KM. Rose-colored beer goggles: The relation between experiencing alcohol consequences and perceived likelihood and valence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(2):311–317. doi: 10.1037/a0024126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1(4):173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Shets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Magidson JF, Reynolds EK, Kahler CW, Lejuez CW. Changes in sensation seeking and risk-taking propensity predict increases in alcohol use among early adolescents. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010;34(8):1400–1408. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey KB, Bradizza CM. Social learning theory. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. New York, NY: Guilford; 1999. pp. 106–163. [Google Scholar]

- Mallett KA, Bachrach RL, Turrisi R. Are all negative consequences truly negative? Assessing variations among college students’ perceptions of alcohol related consequences. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(10):1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP, Barnett NP. The way one thinks affects the way one drinks: Subjective evaluations of alcohol consequences predict subsequent change in drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013a;27(1):42–51. doi: 10.1037/a0029898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP, Colder CR. Normative perceptions and past-year consequences as predictors of subjective evaluations and weekly drinking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2013b;38(11):2625–2634. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide. 7. Los Angeles CA: Muthén Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi CT. Perceived control of drinking and other predictors of alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Addiction Research. 1999;7(4):291–306. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Retrieved August 25, 2012];Recommended alcohol questions. 2004 from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/research/guidelines-and-resources/recommended-alcohol-questions.

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in risk factors and consequences for alcohol use and problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24(8):981–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman P, Armitage CJ, Quigley C. The theory of planned behavior and binge drinking: Assessing the impact of binge drinker prototypes. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(9):1753–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Kim J, Gellis LA, Zaso MJ, Maisto SA. Short-term prospective effects of impulsivity on binge drinking: Mediation by positive and negative drinking consequences. Journal of American College Health. 2014;62(8):517–525. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2014.929579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A, Kim J, Sori ME. Short-term prospective influences of positive drinking consequences on heavy drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27(3):799–805. doi: 10.1037/a0032906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(2):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Maggs JL. Short-term changes in plans to drink and importance of positive and negative alcohol consequences. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31(3):307–321. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Maggs JL. College students’ evaluations of alcohol consequences as positive and negative. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Selig JP. Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures. 2012;6(2):77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Beattie M, Chamberlain R, Merrill JE. Beyond the “Binge” threshold: Heavy drinking patterns and their association with alcohol involvement indices in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(2):225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Predicting functional outcomes among college drinkers: Reliability and predictive validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wardell JD, Bachrach RL. Drinking consequence types in the first college semester differentially predict drinking the following year. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(1):1464–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig JP, Preacher KJ. Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [Computer software] 2008 Jun; Available from http://quantpsy.org/

- Wasserman EA, Miller RR. What’s elementary about associative learning? Annual Review of Psychology. 1997;48:573–607. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Lee H. College binge drinking in the 1990s: A continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. Journal of American College Health. 2000;48(5):199–210. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review. 1985;92(4):548–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR. Reduction of alcohol-related harm on United States college campuses: The use of personal feedback interventions. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(4):310–319. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Ray AE. Differential evaluations of alcohol-related consequences among emerging adults. Prevention Science. 2014;15(1):115–124. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]