Abstract

Couple therapy for women with alcohol use disorders (AUDs) yields positive drinking outcomes, but many women prefer individual to conjoint treatment. The present study compared conjoint cognitive behavioral therapy for women with AUDs to a blend of individual and conjoint therapy. Participants were 59 women with AUDs (95% Caucasian, mean age = 46 years) and their male partners randomly assigned to 12 sessions of Alcohol Behavioral Couple Therapy (ABCT) or to a blend of five individual CBT sessions and seven sessions of ABCT (Blended-ABCT). Drinking and relationship satisfaction were assessed during and for one year post-treatment. Treatment conditions did not differ significantly on number of treatment sessions attended, percent of drinking days (PDD), or heavy drinking days (PDH), during or in the 12 months following treatment. However, effect size estimates suggested a small to moderate effect of Blended-ABCT over ABCT in number of treatment sessions attended, d=−.41, and first- and second-half within treatment PDD, d=−.41, d=−.28, and PDH, d=−.46, d=−.38. Moderator analyses found that women lower in baseline sociotropy had lower PDH across treatment weeks 1–8 in Blended-ABCT than ABCT and that women lower in self-efficacy had lower PDH during follow-up in Blended-ABCT than ABCT. The two treatment groups did not differ significantly in within-treatment or post-treatment relationship satisfaction. Results suggest that blending individual and conjoint treatment yields similar or slightly better outcomes than ABCT, is responsive to women’s expressed desire for individual sessions as part of their treatment, and decreases the challenges of scheduling conjoint sessions.

Keywords: Alcohol Treatment, Women, Couple Therapy, CBT, Self-Efficacy

Women in the United States have a lifetime prevalence of Alcohol Use Disorders (AUDs) of approximately 25.4% (Epstein & Menges, 2013). Women with AUDs have high rates of other comorbid psychiatric disorders, are at high risk for serious medical consequences, and have mortality rates 4–7 times those of the general population. Women with AUDs experience more and different barriers to treatment entry than men with AUDs, including guilt and shame; practical barriers in terms of childcare, transportation, and medical insurance coverage; and lack of support from family for help-seeking (Greenfield et al., 2007).

Intimate partners have an integral role in the development, maintenance, and resolution of AUDs in women. Longitudinal studies show that husbands’ premarital drinking is a strong predictor of their wives’ drinking a year into marriage (Leonard & Mudar, 2003), and the rates of AUDs among the male partners of women with AUDs are high (Low, Cui, & Merikangas, 2007). Women with AUDs report relationship difficulties as an important antecedent to alcohol use and relapse (Walitzer & Dearing, 2006; Zweig, McCrady, & Epstein, 2009), and also report drinking to cope with sexual situations (Sobczak, 2009). Given the close interrelationships between drinking and intimate relationships among women with AUDs, partner-involved treatment would seem to hold promise. Two recent randomized clinical trials compared Alcohol Behavioral Couple Therapy (ABCT) to efficacious individual treatments for women with AUDs. In both studies, women were in a committed relationship with a male partner who was willing to participate in the treatment. McCrady, Epstein, Cook, Jensen, & Hildebrandt (2009) compared 12 sessions of ABCT to 12 sessions of individual cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). Although women decreased drinking significantly in both treatment conditions and maintained most gains after treatment, women in the ABCT treatment condition had significantly greater improvement in and a higher percentage of abstinent days (PDA) and significantly greater improvement and a lower percent heavy drinking days (PDH) during and for one year following treatment than women receiving individual CBT. McCrady et al. also found that the presence of both Axis I and Axis II disorders moderated drinking outcomes, with differential positive effects of ABCT for women with co-occurring Axis I and Axis II disorders. Schumm, O’Farrell, Kahler, Murphy, & Muchowski (2014) compared 26 sessions of 12-step oriented individually based 12-step oriented treatment to a protocol of 13 sessions of behavioral couple therapy plus 13 sessions of IBT. Similar to McCrady et al., Schumm et al. reported significant increases in PDA and decreases in substance-related problems across treatment conditions, and also found that women receiving the combination of behavioral couple therapy and 12-step focused individual therapy had greater improvements in both PDA than women receiving only 12-step individual therapy. Schumm et al. also found positive effects of ABCT on relationship satisfaction for the women and their partners.

Despite the strong evidence for the efficacy of partner-involved treatment for women whose partners are willing to participate in treatment, women with AUDs may be reluctant to utilize this treatment modality. In our earlier study of ABCT for women with AUDs (McCrady et al., 2009), only 29% of women who inquired about the study began treatment in the clinical trial. Among those not entering the study, 45% cited partner-related reasons for not pursuing the study treatment. Further, women whose randomly assigned treatment condition matched their preference for individual treatment attended more treatment sessions than women who preferred individual treatment but were assigned to ABCT (Graff et al., 2009). Based on these findings, we designed the current clinical trial to provide women with AUDs a choice of individual or couple therapy. We found that women disproportionately selected individual over couple therapy (75.8%), citing desire to work on their individual problems, lack of perceived support from their partners, and the logistics of scheduling conjoint sessions as reasons for preferring individual treatment. Women who selected conjoint treatment reported a desire for support from their partner, and that they either had a good relationship or wanted to work on relationship problems (McCrady, Epstein, Cook, Jensen, and Ladd (2011).

Certain variables may moderate women’s response to couple therapy. Research consistently has found that higher self-efficacy to cope with drinking-related situations predicts positive drinking outcomes (e.g., Kelly & Hoeppner, 2013). However, some research with women suggests that a focus on network support might have a negative effect on self-efficacy (Litt, Kadden, & Tennen, 2015). Thus, there is a possibility that an all-conjoint therapy approach might not be optimal for women with low self-efficacy.

Autonomy has been described as “the person’s investment in preserving and increasing his [sic] independence, mobility, and personal rights;” sociotropy is defined as “the person’s investment in positive interchange with others” and “dependence on social feedback for gratification and support” (Bieling, Beck, & Brown, 2000, page 763). Sociotropy has been found to correlate with greater interpersonal sensitivity (Otani et al., 2012) and lower self-directedness (Otani et al., 2011). Accordingly, it is possible that individual therapy might add value to couple therapy for women low in autonomy and high in sociotropy by building coping skills, and strengthening the women’s sense of independence and confidence, and decreasing their need to please others before addressing partner support for abstinence and relationship skills. Thus we reasoned that women high in sociotropy might be particularly sensitive to the presence of their partner in therapy sessions, and that a blend of individual and conjoint treatment might be more effective for these women. Although there was not an extant literature to guide the development of hypotheses about autonomy, we reasoned that women who were low in autonomy might benefit particularly from having some individual treatment that focused on individual skills building.

We hypothesized that: (a) The number of treatment sessions attended would be higher in Blended-ABCT, compared to ABCT. We anticipated that the logistics of scheduling conjoint sessions would be less difficult in Blended-ABCT than ABCT; prior research also suggested that women prefer individual to conjoint sessions. (b) Drinking outcomes would be more positive for women in Blended-ABCT than women in ABCT. Attending a greater number of treatment sessions typically predicts more positive treatment response, and the individual sessions were designed to enhance abstinence skills acquisition and early treatment engagement. (c) Blended-ABCT would be particularly effective for women with lower autonomy, higher sociotropy, and lower self-efficacy for coping with drinking-related situations. (d) Blended-ABCT and ABCT would be equally effective in impacting relationship satisfaction. Although the two treatments differed in the number of sessions attended by the male partner, the treatments were equated on the actual number of specific couple therapy interventions (i.e., reciprocity enhancement and communication/joint problem-solving skills training).

Method

Trial Design

The study was a randomized clinical trial (RCT) using a modified intent-to-treat design in which participants who received at least one treatment session were included in all analyses. This RCT is part of a larger parent study; the larger study design allowed women inquiring about the study to choose between an individual or couple therapy study arm. Each study arm was designed as a separate randomized clinical trial (RCT), with the individual arm comparing standard CBT to women’s-specific CBT, and the couple arm comparing ABCT with Blended-ABCT. Of the first 286 callers who were eligible for the study, three-quarters scheduled an individual in-person intake interview, and planned participant recruitment for the individual study arm (n = 99) was completed. When individual study arm recruitment was complete, there were 17 women in the couple arm of the study, so we then advertised and recruited only for the couple arm of the study, retaining the RCT design to compare ABCT with Blended-ABCT. An additional 156 women callers were eligible for the study during the couple-only phase of participant recruitment. The present paper reports the results of the couple arm of the trial.

The 17 women who selected the couple arm attended more sessions (difference=2.30, SE=1.14, p=0.049), had more alcohol dependence symptoms (difference=0.96, SE=0.45, p=.04), and had a lower past year household income (M= $90,275, SD = $47,812 versus M = $128,850, SD = $75,104, t(49.25) = −2.36, p = 0.02) than those consented into the study after the choice period, but the groups did not differ on other baseline measures.

Participants

Study participants were recruited from 2003–2007 using a variety of strategies including print and on-line advertisements; outreach to community groups, health care providers; and various media outlets. All study procedures were conducted at the Center of Alcohol Studies at Rutgers University. Inclusion criteria were: (a) woman; (b) in a committed heterosexual relationship, defined as married, separated with hopes of reconciliation, cohabitating for at least six months, or in a committed dating relationship of at least one year’s duration; (c) consumed alcohol in the past 30 days; (d) met criteria for DSM-IV alcohol abuse or dependence. Exclusion criteria were: (a) either partner meeting criteria for another current substance use disorder with physiological dependence on drugs other than marijuana or nicotine; (b) either partner reporting evidence of psychotic symptoms in past six months; (c) either partner showing evidence of significant cognitive impairment; (d) evidence of intimate partner violence (IPV) in the past 12 months that resulted in injury and/or fear of participating in conjoint therapy. A total of 68 women and their male partners consented to study involvement; 65 were randomly assigned to ABCT (n = 35) or Blended-ABCT (n = 30).

Procedures

Screening and informed consent

Callers initially were screened by telephone for study eligibility. In the initial phase of the study, when women had a choice of individual or couple therapy, the interviewer provided a brief description of each approach. Women who were interested and potentially eligible then scheduled either an individual or conjoint in-person clinical screening interview. Couples who attended the in-person clinical screening interview together could, at the end of the interview, opt for the individual arm of the study. Women who attended the clinical screening interview without their male partner were not eligible for the couple arm of the study. After the individual arm was no longer open for enrollment, telephone interviewers provided a description only of the couple arm of the study and scheduled women and their partners to attend the in-person clinical screening interview together.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board and each couple provided informed consent to participate in the study. During the in-person clinical research interview, with both partners present, a study clinician obtained a brief drinking history, fully assessed study eligibility, and provided a detailed study description. Each partner completed self-report questionnaires and the clinician met separately with each partner to assess intimate partner violence (IPV).

Baseline assessment

After obtaining informed consent, baseline assessment data were collected from the women by to assess drinking, psychopathology, and other aspects of psychosocial functioning. Interviewers were bachelors or masters level staff who were trained all study procedures and on each standardized interview through a review of the purpose of each question, role play rehearsal, and on-going review of interview materials and supervision/ feedback to maintain standardized administration. Standardized questionnaires were computer-administered. At the completion of the baseline assessment, participants were paid $50.

Randomization

At the end of the baseline, participants were randomly assigned to ABCT or Blended-ABCT, using an urn randomization program to counter-balance groups on depression (a score of > 14 on the Beck Depression Inventory versus < 14), male partner drinking status (recovering, abstainer, or light drinker versus moderate or heavy drinker), and self-reported drinking goal (abstinence versus reduced drinking). At the completion of the baseline, the study interviewer entered the three randomization variables into an urn randomization program to determine treatment condition assignment. Clinicians and study interviewers were blind to study condition until the end of baseline data collection.

Study interventions and therapists

Both treatments were manual-guided, 90-minute, 12-session outpatient cognitive-behavioral protocols with an explicit and agreed-upon goal of abstinence from alcohol. Treatment could extend up to 16 weeks to allow for illnesses, holidays, and vacations. In-person clinical research intake interviews and treatment were provided by 12 female and 3 male clinicians (7 doctoral; 8 masters level) who received structured training on study interventions that included review of session materials, role play demonstrations, and role play rehearsal of each session, followed by participation in weekly 90 minute group supervision. The study principal investigators listened to all 12 session recordings for at least the first two clients in each treatment condition of each therapist. Therapists were assigned a clinical supervisor who provided individual supervision as needed to supplement the group supervision.

Treatment integrity was assessed using the Treatment Integrity Rating System for Couples developed by the second and first authors. The C-TIRS included 52 items to assess frequency and quality of specific treatment components (e.g., functional analysis, couple therapy skills), common factors for therapy in general (e.g., empathy), general level of skill administering the manuals, and prescribed and proscribed behaviors. In total, 49 subjects (83%) had at least one session tape rated, an average of 4.04 (SD = 1.61) sessions were rated per subject who attended at least one therapy session, and an average of 44.52% (SD= 14.98) of sessions attended were rated. Treatment integrity (quantity and quality) ratings did not differ between the two treatments, with the exception of the quantity ratings for couples therapy process and interventions, t(46) = −3.01, p =.004, and t(47) = −3.56, p = .001, respectively, both of which were higher for ABCT than Blended-ABCT. Adherence to the treatment protocols (1–5) scale was high for quantity (M = 4.08, SD = .53) and quality ratings (M = 4.15, SD = 0.48).

Alcohol Behavioral Couple Therapy (ABCT) (McCrady & Epstein, 2009a, 2009b)

Both partners participated in all treatment sessions. Early sessions (1–6) focused on strategies to enhance motivation such as assessment feedback, a non-confrontational therapist stance, and use of a decisional matrix, as well as CBT strategies to help the woman attain and maintain abstinence from alcohol, including functional analysis, developing a high-risk hierarchy, self-management planning, skills training to manage urges to drink, and rearranging behavioral consequences of drinking. The only explicitly couple-focused interventions in the first 6 sessions were exercises to notice positive behaviors from the partner and to initiate a shared positive activity. The first six sessions also included strategies to increase partner support for abstinence and reduce partner-related triggers. Sessions 7–12 focused on additional alcohol-related coping skills, including drink refusal, dealing with alcohol-related thoughts, and relapse prevention, additional partner skills to support sobriety, and relationship enhancement interventions with a particular focus on shared activities, communication skills, and problem-solving.

Blended Alcohol Behavioral Couple Therapy (Blended-ABCT)

Partners attended the first treatment session together, covering content similar to the first session of ABCT. The male partner was given an assignment to provide support to the woman during the weeks when the woman received five sessions of individual CBT, following the same outline of individual CBT skills described for the first six sessions of ABCT. The male partner returned for the second six sessions of treatment, which, similar to ABCT, taught partner skills to support sobriety, relationship enhancement interventions, and relapse prevention. On-line supplemental tables are provided that include detailed session outlines for each treatment.

Follow-up

Women were assessed 3, 9, and 15 months after the baseline interview; the 3 month assessment was delayed to the end of treatment for women who were still in treatment at the 3-month time point. Women were paid $50 for the 3-month interview and $75 for the 9- and 15-month interviews. Follow-up rates were 88% at 3-months; 83% at 9 months, and 80% at 15 months. Only three participants provided no follow-up data, and since the growth curve models used to analyze treatment outcomes do not require complete data, we were able to model outcomes using data from 95% of participants. Interviewers were not blind to treatment condition during follow-up. Two adverse events occurred that were unrelated to the study protocol.

Study Measures

Drinking measures

Form-90 (Miller, 1996)

Daily drinking data were collected using the Form-90 version of the Timeline Followback Interview (TLFB). Baseline data were collected for 90 days prior to the last pre-baseline drinking day; follow-up data were collected onward from the day of the previous interview. Percent drinking days (PDD) and percent days of heavy drinking (PDH) were the primary study outcome variables. Tonigan, Miller, & Brown (1997) report good to excellent test-retest reliability for alcohol use assessed using the TLFB, with ICCs ranging from .76–.97 for percent abstinent days and .60–.95 for percent heavy drinking days.

Daily Drinking Logs (DDLs)

Women maintained daily records of drinking, drinking urges, and relationship satisfaction throughout the treatment. DDL data were used for analyses of within treatment drinking and relationship satisfaction. When DDL data were missing, TLFB data were substituted in the within treatment data set. Previous analyses comparing DDL data to TLFB data suggest good agreement between the two data sources (McCrady et al., 1999).

Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) (Miller, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 1995)

The SIP is a 15-item measure of negative consequences of drinking and was used to describe the severity of the women’s drinking and as part of the feedback provided to couples in session 1. Reported test-retest reliability is in the good to excellent range, with ICCs ranging from .59–.93 for the five subscales; total scale reported ICC is .89 (Miller et al., 1995).

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV), Substance Abuse Module (First, Gibbon, Spitzer, & Williams et al., 1996)

The SCID-IV substance abuse module was used to establish a current and lifetime diagnosis of AUD and to screen for other drug dependence with physiological dependence. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID for alcohol diagnoses has been reported at kappa = .75 (Williams et al., 1992).

The Important People Inventory (IPI; Longabaugh, 2001)

is an interview that assesses dimensions of social network structure, network drinking, and network response to drinking and abstinence (Longabaugh, Wirtz, Zweben, & Stout, 1998). Reported test-retest reliability for the IPA is excellent (Longabaugh et al., 1998). The woman’s report of her partner’s drinking status (abstainer/recovering alcoholic/light vs. moderate or heavy) was used for the urn randomization.

Drinking goal (Hall, Havassy, & Wasserman, 1991)

At the beginning of the clinical screening women were asked to rate their drinking goal on a scale that ranged from “I have decided not change my pattern of drinking” to “I have decided to quit drinking once and for all, even though I realize I may slip up and drink once in a while,” or, “I have decided to quit drinking once and for all, to be totally abstinent, and never drink alcohol ever again for the rest of my life.” Either of the latter two responses was coded as an abstinence goal.

Relationship measures

Dyadic Adjustment Scale – short form (DAS-7) (Hunsley, Best, Lefebvre, & Vito, 2001)

The DAS-7 is an abbreviated version of the original Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976) and was used to measure relationship satisfaction over time. Criterion, convergent, and discriminative validity of the instrument are good (Hunsley et al., 2001).

Modified Conflict Tactics Scale (MCTS) (Pan et al., 1994)

The MCTS, administered during the in-person screening interview, is a 24-item self-report measure of relationship aggression during the past 12 months and was used to screen for Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). Respondents answered each question about their own and their partner’s behavior. Reported agreement between partners on the presence of minor (r = .72) and major (r = .45) IPV is fair (McCrady et al., 2009).

Psychopathology measures

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996)

The BDI is widely used to assess symptoms of depression. BDI score was used as an urn randomization variable. Reported coefficient alpha for the instrument is .91 (Beck, Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996).

SCID for DSM-IV (First et al., 1996)

SCID modules were administered to assess current and lifetime Axis I disorders. Good inter-rater reliabilities have been reported for the SCID, with a mean reported kappa of 0.87 (Epstein, Labouvie, McCrady, Jensen, & Hayaki, 2002). The presence or absence of other psychopathology was tested as a possible moderator.

Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire for DSM-IV (PDQ-4+) (Hyler, 1994)

The PDQ-4+ is a 99 item self-report measure to derive binary diagnostic coding for the 11 personality disorders listed in DSM-IV-TR. Research on the PDQ-4+ has shown a high false-positive rate, low internal consistency for most Axis II diagnostic categories, and low diagnostic agreement for specific personality disorders (Fossati et al., 1998: Hyler, Skodol, Oldham, Kellman, & Doidge, 1992; Wilberg, Dammen, & Friis, 2000). Therefore, use of the total score for screening items is suggested by Wilberg et al. (2000). Although there are no published cut-offs directly applicable to the present sample, for the current study we used a cut-off score of 25 (Davison, Leese, & Taylor, 2001) to characterize the sample as positive or negative for the presence of a possible personality disorder. Internal consistency for the PDQ total score in the present sample was α = .90; mean PDQ score was 23.64 (SD = 13.03).

Other Moderators

Situational Confidence Questionnaire-39 (SCQ-39) (Annis & Graham, 1988)

The SCQ-39 was used as a measure of self-efficacy to cope with drinking situations without consuming alcohol as a possible moderator of treatment outcome. Test-retest reliability and internal consistency are adequate for the measure.

Sociotropy-Autonomy Scale (SAS) (Bieling, Beck, & Brown, 2000)

The SAS was designed originally to measure sociotropy, which focuses on an individual’s concern with others’ opinion of him/her; and autonomy, which focuses on an individual’s concern with his/her independence. Factor analyses of the measure (Bieling et al., 2000) identified four factors. Two factors contributed to the sociotropy construct - Preference for Affiliation and Fear of Criticism and Rejection. The latter scale has a stronger association with psychopathology (Bieling et al., 2000), and was as a possible moderator of treatment response. Factor analysis of the Autonomy scale (Bieling et al., 2000) also yielded a two factor solution - Sensitivity to Others’ Control and Independent Goal Attainment. The latter scale was negatively associated with psychopathology and was used to measure autonomy as a possible moderator of treatment response. Reported construct validity for these factors is good.

Analytic Plan

There were no significant differences between conditions in the amount of missing data for each week during treatment or each month post-treatment. Those who were missing follow-up data attended fewer treatment sessions (M = 4.75; SD = 4.09; n = 47) than those providing follow-up data (M = 9.62; SD = 3.56, n = 12), t (15.52) = 3.77, p< .001, but did not differ on any baseline variables. Drinking classification (abstinent, non-heavy, or heavy drinking), the proportion of days drinking (PDD), and proportion of days with heavy drinking (PDH) were selected as the primary outcome variables.

We first examined drinking outcomes using a classification-based approach that reflected whether participants were continuously abstinent (“abstainers,” PDD = 0), engaging in some non-heavy drinking (“light-to-moderate drinkers,” PDD > 0, PDH = 0), or engaging in any heavy drinking (“heavy drinkers,” PDH > 0) throughout the treatment and follow-up periods. Differences in the rates of continuous abstinence, non-heavy drinking, and heavy drinking between ABCT and Blended-ABCT were then tested using chi-square tests for each week of the treatment period and each month of the follow-up period.

Second, we examined drinking outcomes using a continuous-measures approach to PDD and PDH via growth curve modeling. Analyses used generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs; Stroup, 2014), which combine linear mixed models (i.e., multilevel modeling) with generalized linear models to account for non-normally distributed outcomes. In these analyses, daily drinking variables reflecting any drinking (yes/no) and any heavy drinking (yes/no) were left as dichotomous variables that were fit using GLMMs with a logit link function. This allowed us to avoid using aggregated PDD and PDH summary measures, which typically have considerable violations to normality (and can increase type-I and type-II errors; Atkins & Gallop, 2007), and instead allowed the GLMM to internally represent continuous values of PDD and PDH across time for each participant. Distributions of variables were examined for anomalies and outliers more than two standard deviations from the mean were Winsorized. Mean-centered values of baseline PDD or PDH were entered as covariates in growth models to control for baseline drinking. Treatment condition was coded as 0 for ABCT and 1 for Blended-ABCT and then was mean-centered. A dichotomous variable reflecting recruitment when women had a choice of individual vs. couple treatment (0) vs. when women had no choice of individual vs. couple treatment (1) also was computed, grand-mean centered, and included in all outcome analyses. The GLMMs were modeled in R using lme4 (Bates, Maechler, Bolker, Walker, 2014) and used maximum likelihood to account for missing data.

Piecewise growth curve models were estimated for three different time periods for PDD and PDH: treatment weeks 1–8, treatment weeks 9–16, and the next 46 weeks post-treatment (after which point, drinking data were unavailable the majority of participants). The choice to model these three periods separately was based on examination of the raw data, overall growth-curve model fit indices, a priori hypotheses about these qualitatively distinct periods of time due to male partners’ being scheduled to attend sessions 7–12 (corresponding on average to weeks 9–16 after the first treatment session) in Blended-ABCT, and empirical comparisons of different growth curve model fits. Nested model comparisons for PDD and PDH indicated better fit for two discontinuous piecewise growth curves during the within-treatment period compared to continuous piecewise growth curves or a single growth curve, all χ2 ≥ 19.60, all p < 0.001. A single growth term was supported for relationship satisfaction, χ2 = 1.62, p = 0.20. The best-fitting models for PDD and PDH at all three time points included fixed and random effects for intercepts and slopes for linear change over time without quadratic growth terms. Time variables were scaled with 0 as the first day for each period in the piecewise growth curve model and a one-unit increase in the time variable corresponded with a period of 30 days.

For the fourth hypothesis (equivalence of relationship satisfaction outcomes), equivalence testing was conducted in line with Rogers, Howard, and Vessey (1993). We defined an equivalence interval where, if the 95% CI of the differences between the treatment groups was contained entirely within that interval, we would reject the null hypothesis of non-equivalence (i.e., we would conclude a likelihood of equivalence between groups). Conversely, if any part of the 95% CI was outside of the interval, we would retain the null hypothesis of non-equivalence. A Cohen’s d effect size of d = ±0.5 was chosen as the equivalence interval, traditionally considered a medium effect size. Cohen’s d was computed based on main effects of treatment for the overall (aggregated) values of the daily relationship satisfaction measures used within treatment and for each of the three follow-up time points after treatment. Estimates controlled for baseline values of the outcome variables and the “choice” variable reflecting choice versus no choice for the couple versus individual format.

Finally, we tested hypothesized moderators of treatment outcomes including sociotropy, autonomy, and self-efficacy, and conducted exploratory analyses of other potential moderators based on previous research with ABCT for women (McCrady, Owens, & Brovko 2013), including the presence of any Axis I disorder, the degree of Axis II psychopathology, and relationship satisfaction. Each moderator was tested in a separate model controlling for fixed and random effects of time.

Results

Participants

Participant flow (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram of Patient Flow

A total of 535 calls were received in inquiry to the parent study (including the individual and couple arms of the study); of these, 442 (82.6%) women met initial screening criteria and 258 (58.4% of eligible callers) scheduled either an individual or couple in-person interview. Of those who scheduled a couple interview (n = 149), 68 (45.6%) completed the interview and consented to study participation. Nine couples (13.2% of those who consented) dropped out prior to the initial treatment session. Thus, of couples initially interested in the couple arm of the study, 39.6% entered treatment.

Participant characteristics

Table 1 summarizes participant characteristics. On average, the women were middle-aged and had completed some college. Prior to treatment, they had been drinking on almost 75% of days, with most of these days being heavy drinking days. About 37% met criteria for at least one additional Axis I diagnosis, 42% were classified with a possible Axis II disorder on the PDQ, and the mean score on the DAS-7 placed women between reported scores for distressed and non-distressed women (Huntley et al., 2001). The two groups did not differ significantly on baseline demographic, drinking, relationship functioning, or other psychopathology measures.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Total N=59 |

ABCT N=31 |

Blended- ABCT N=28 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 46.0 (9.1) | 46.0 (10.8) | 46.0 (6.9) |

| Race (% Caucasian) | 56 (94.9%) | 29 (93.6%) | 27 (96.4%) |

| Years Education | 15.3 (2.7) | 14.9 (3.0) | 15.7 (2.1) |

| Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS-7) | 21.1 (6.7) | 20.5 (7.0) | 21.7 (6.5) |

| Household income (median) | $103,500 | $96,000 | $121,000 |

| Employed full- or part-time (%) | 39 (66.1%) | 20 (64.5%) | 19 (67.9%) |

| Percent Drinking Days Baseline | 73.9 (23.8) | 74.7 (27.3) | 73.2 (19.7) |

| Percent Heavy Drinking Days Baseline | 62.1 (28.4) | 64.6 (30.2) | 59.3 (26.6) |

| Mean drinks per drink day Baseline | 6.7 (4.5) | 6.4 (2.8) | 6.9 (5.9) |

| Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) score | 9.5 (3.1) | 9.4 (3.2) | 9.6 (2.9) |

| Number (%) with other current Axis I dx. | 22 (37%) | 12 (39%) | 10 (36%) |

| Number (%) with Probable Axis II dx.1 | 25 (42%) | 13 (42%) | 12 (43%) |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 18.9 (10.5) | 19.5 (10.1) | 18.3 (11.1) |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 12.4 (9.4) | 13.3 (10.1) | 11.3 (8.6) |

PDQ Score > 25

Treatment Utilization

Treatment attendance (hypothesis 1)

Women in the ABCT condition attended a mean of 7.8 (SD = 4.4) sessions; women in Blended-ABCT attended a mean of 9.5 (SD = 3.7) sessions, which is equivalent to 5 individual sessions and 4.5 conjoint sessions. Number of sessions attended did not differ significantly, t(56.66) = 1.57, p = .12, d = 0.41, 95% CI −0.45 to 3.78.

Homework completion

Overall, couples assigned to ABCT completed a mean of 60.3% (SD = 30.1) of individual and conjoint homework assignments; homework completion in the Blended-ABCT condition was not significantly different (M = 69.7%; SD = 22.1), t(54.87) = 1.37, p > .05, d = 0.38, 95% CI −0.14 to 0.90.

Utilization of other treatment services

In the 12 months following the study treatment, no women used any inpatient treatment, and 12 women in Blended-ABCT and 13 in ABCT used other outpatient counseling (alcohol or psychiatric). Six women in Blended-ABCT and 5 women in ABCT attended at least one AA meeting. There were no significant differences between conditions.

Drinking Outcomes (Hypothesis 2)

Categorical drinking outcomes

Participants were classified as abstinent, light or moderate, or heavy drinkers for each week during treatment and each month in the follow-up. Chi-square tests indicated that rates of complete abstinence, non-heavy drinking, and heavy drinking during each week or month period were not significantly different between the two treatment conditions. The percentages of participants who were abstinent on any given week ranged from 16–50%, but only 14% of participants in Blended-ABCT and 13% in ABCT remained abstinent during the whole treatment period. About a quarter of participants reported no heavy drinking days during the full treatment period (29% in Blended-ABCT, 23% in ABCT), and heavy drinking was more common during earlier treatment weeks. Few participants remained fully abstinent during the follow-up period (11% in Blended-ABCT, 6% in ABCT), although abstinence rates within any particular follow-up month were higher (ranging from 16% to 29%), reflecting the episodic nature of drinking. Forty three percent of women in Blended-ABCT and 35% of women in ABCT had no heavy drinking days during the follow-up period.

Growth curves models: Drinking outcomes

Growth curve model results are presented in Table 2, with results for PDD presented on the left side, PDH presented on the right, and significant effects shown in bold. There were no significant main effects for treatment condition or significant treatment × time interactions, indicating that the overall levels of PDD and PDH and the amount of change over time did not differ between conditions. Effect sizes were estimated for between-group differences in outcomes, controlling for the baseline value of the outcome variable, and for the choice versus no choice status of participants. Standardized regression estimates suggested a small to moderate effect of Blended-ABCT compared to ABCT for weeks 1–8 of treatment for both PDD, d = −0.41 (95% CI: −0.90, 0.07), and PDH, d = −0.46 (95% CI: −0.97, 0.05), a small effect favoring Blended-ABCT for weeks 9–16 for PDD, d = −0.28 (95% CI: −0.83, 0.26), and a small to moderate effect favoring Blended-ABCT for weeks 9–16 for PDH, d = −0.38 (95% CI: −0.94, 0.18). Post-treatment effect size estimates were d ≤ .10.

Table 2.

| Percentage of Drinking Days (PDD) |

Percentage of Heavy Drinking Days (PDH) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | z | p | Estimate | SE | z | p | |

| Treatment Weeks 1–8 | ||||||||

| Intercept | −0.38 | 0.42 | −0.93 | .355 | −2.03 | 0.38 | −5.36 | .000 |

| Baseline PDD or PDH | 4.60 | 1.62 | 2.83 | .005 | 3.90 | 1.13 | 3.44 | .001 |

| Choice variable1 | −0.80 | 0.83 | −0.97 | .333 | 0.07 | 0.65 | 0.11 | .909 |

| Condition | −1.49 | 0.83 | −1.79 | .074 | −1.29 | 0.71 | −1.83 | .067 |

| Time | −0.85 | 0.33 | −2.54 | .011 | −0.87 | 0.36 | −2.40 | .017 |

| Condition × Time | 0.36 | 0.66 | 0.55 | .584 | 0.42 | 0.65 | 0.64 | .519 |

| Random Intercept Var. | 8.10 | 4.88 | ||||||

| Random Time Var. | 4.56 | 3.63 | ||||||

| Intercept-Time Corr. | −0.35 | −0.41 | ||||||

| Treatment Weeks 9–16 | ||||||||

| Intercept | −2.02 | 0.48 | −4.24 | .000 | −3.80 | 0.67 | −5.69 | .000 |

| Baseline PDD or PDH | 3.08 | 1.97 | 1.56 | .119 | 3.85 | 1.91 | 2.02 | .044 |

| Choice variable | 0.23 | 1.01 | 0.23 | .820 | 0.78 | 1.11 | 0.71 | .480 |

| Condition | −0.47 | 0.94 | −0.50 | .616 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.00 | .997 |

| Time | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.14 | .888 | −0.42 | 0.59 | −0.70 | .483 |

| Condition × Time | −0.35 | 0.62 | −0.56 | .573 | −0.84 | 0.76 | −1.10 | .270 |

| Random Intercept Var. | 9.15 | 8.21 | ||||||

| Random Time Var. | 3.40 | 3.92 | ||||||

| Intercept-Time Corr. | −0.10 | −0.09 | ||||||

| Post-Treatment | ||||||||

| Intercept | −1.38 | 0.43 | −3.21 | .001 | −3.20 | 0.44 | −7.20 | .000 |

| Baseline PDD or PDH | 5.40 | 1.83 | 2.94 | .003 | 5.11 | 1.57 | 3.27 | .001 |

| Choice variable | 0.72 | 0.98 | 0.74 | .462 | 1.32 | 0.98 | 1.35 | .176 |

| Condition | −0.62 | 0.89 | −0.70 | .484 | −0.93 | 0.88 | −1.05 | .292 |

| Time | −0.10 | 0.12 | −0.78 | .434 | −0.27 | 0.11 | −2.52 | .012 |

| Condition × Time | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.25 | .803 | 0.34 | 0.20 | 1.71 | .087 |

| Random Intercept Var. | 7.78 | 7.10 | ||||||

| Random Time Var. | 0.66 | 0.41 | ||||||

| Intercept-Time Corr. | 0.03 | 0.00 | ||||||

Choice variable denotes participants who had a choice of individual or couple therapy versus those who only had the option of some form of couple therapy.

Significant main effects for time indicated that both PDD and PDH decreased significantly in both groups during treatment weeks 1–8 with no significant change over time during treatment weeks 9–16 or the follow-up period. All models had significant effects for baseline PDD or PDH control variables except the PDD model for treatment weeks 9–16.

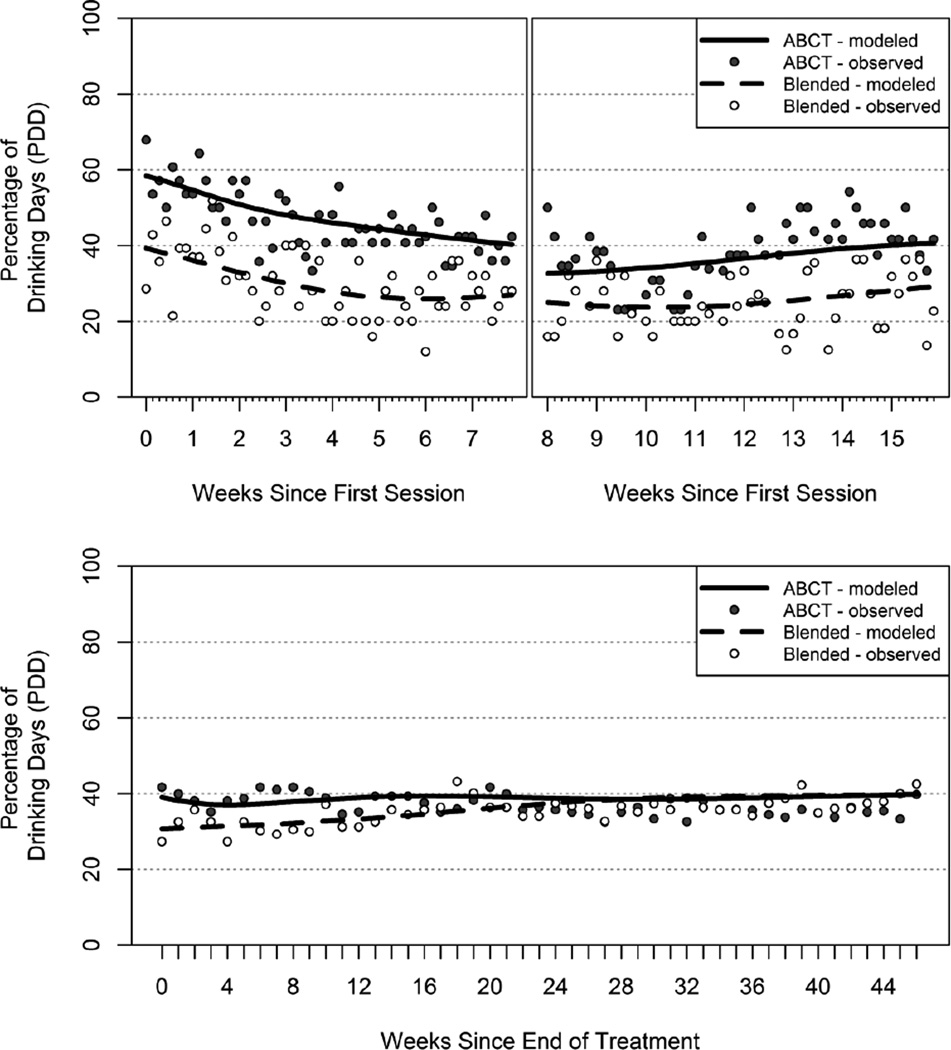

Growth curve models are plotted in Figures 2 (PDD) and 3 (PDH) to illustrate the combined results shown in Table 2. As illustrated in the figures, PDD started at approximately 60% in ABCT and 40% in Blended-ABCT and decreased by roughly 15–20% in both groups during weeks 1–8. PDD remained between 35–40% in ABCT and around 25% in Blended-ABCT during treatment weeks 9–16. In the post-treatment period, PDD started at approximately 30% in Blended-ABCT and 40% in ABCT, leveling off to approximately 40% in both groups (regression effects for time were non-significant). PDH displayed a similar pattern of reduction during treatment weeks 1–8 and leveling off in subsequent treatment and follow-up weeks.

Figure 2.

Growth Curve Models Percent Drinking Days. Model-implied marginal growth curves (lines) and observed point estimates of PDD (dots) are shown for each day in the within-treatment periods (top panels) and each week in the post treatment period (bottom panel).

Figure 3.

Growth Curve Models Percent Days of Heavy Drinking. Model-implied marginal growth curves (lines) and observed point estimates of PDH (dots) are shown for each day in the within-treatment periods (top panels) and each week in the post treatment period (bottom panel).

Moderators of Drinking Outcome (Hypothesis 3 and Post Hoc Analyses)

Three variables, sociotropy, autonomy, and self-efficacy, were hypothesized moderators of response to treatment. Post hoc, we also tested the presence/absence of an Axis I or Axis II disorders as possible moderators. Among the baseline variables tested as moderators, sociotropy, self-efficacy, and having a current axis-I diagnosis and had significant interactions with treatment to predict PDD or PDH. There was a significant sociotropy × treatment effect in predicting PDH across treatment weeks 1–8 (B = 0.16, SE = 0.05, p = .004) and the 12 month follow-up period (B = 0.27, SE = 0.09, p = .004). There was a significant self-efficacy × treatment effect (B = 2.21, SE = 1.05, p = 0.04) and a significant axis-I diagnosis × treatment effect (B = 3.68, SE = 1.86, p = .048) for predicting PDH across the 12 month follow up period. Plots of these interactions are displayed in Figure 4, which shows the relationships between moderator variables (x-axes) and PDD or PDH (y-axes) for each treatment condition (separate lines). Follow-up analyses identified regions of significance where values of the moderator variables were associated with significant differences between the ABCT and Blended-ABCT conditions. Moving-intercept models were tested where the values of the baseline moderators were centered with values of 0 along different points on their observed distributions (similar to McCrady et al., 2009). Moving-intercept models used aggregate PDD and PDH estimates across the periods in which they were analyzed due to occasional non-convergence of GLMM. Significant main effects of treatment condition within the moderation analysis along each point were taken to indicate a significant difference between the conditions at that point. Results of the moving-intercept models are presented in Figure 4 with vertical bars indicating standard error estimates of the treatment effect at each point in the moving-intercept models and asterisks indicating the significance between treatment conditions at each point. Histograms of the distributions of moderator variables are displayed below each interaction for reference and moving intercept models are tested along equally spaced intervals between the 10th and 90th percentiles of the moderator variable distributions.

Figure 4.

Moderator Analyses

Based on the moving intercept models, participants in Blended-ABCT had significantly lower PDH across treatment weeks 1–8 if they were low in baseline sociotropy, and had no difference in PDH if they were high in sociotropy (top row of Figure 4). Despite significant moderation, moving-intercept models did not yield any significant differences between Blended-ABCT and ABCT on post-treatment PDH based on current axis-I diagnosis, baseline sociotropy, or baseline self-efficacy.

Baseline drinking goals were categorized as abstinent or nonabstinent. Overall, 32 (54.2%) women selected a nonabstinent goal, 20 (33.9%) selected an abstinent goal, and 7 (11.9%) defined their own goal. Drinking goals did not differ between treatment conditions and did not predict session attendance (mean sessions attended for participants with a goal of abstinence = 7.35, SD=4.42; mean sessions attended for participants with nonabstinent goals = 9.28, SD=3.89; p = 0.09). There were no differences in PDD or PDH during the first or second half of treatment between those who defined an abstinent versus a nonabstinent goal. Post-treatment, there was a significant difference in PDD favoring the group with an abstinence goal (M (nonabstinent) = 45, SD = 33; M PDA (abstinent) = 24, SD = 33), t(26.18) = 2.09; p = .047.

Hypothesis 4: Relationship Outcomes

Growth curve models for relationship satisfaction within treatment (DDL) and post-treatment (DAS-7) indicated that were no significant main effects of time, condition, or time x condition interactions during treatment. Equivalence testing supported the equivalence of the treatments on the DAS-7 at post treatment, d =-0.05 (95% CI: −0.43, 0.33, but did not support the equivalence hypothesis during treatment (based on DDL data), d = 0.09 (95% CI: −0.49, 0.68) or at 6- or 12-months post-treatment, d = −0.14 (95% CI: −0.58, 0.30) at 6 months; d = −0.08 (95% CI: −0.62, 0.45) at 12 months, based on the DAS-7.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to develop and test a model of treatment for women with AUDs that combined behavioral individual and conjoint treatment against an established treatment of just behavioral conjoint therapy. Overall, in both treatment conditions, women decreased the frequency of drinking and heavy drinking during treatment and maintained these gains after treatment. We found suggestive but inconclusive support for the four hypotheses tested in the present study: (a) We predicted that the number of treatment sessions attended would be higher in Blended-ABCT than ABCT. We found small to moderate but non-significant effects of Blended-ABCT over ABCT in treatment session attendance; (b) We predicted that drinking outcomes would be more positive for women receiving Blended-ABCT than women receiving ABCT. We found small to moderate but non-significant effects of Blended-ABCT over ABCT for PDD and PDH during treatment, but no overall significant differences in drinking or heavy drinking outcomes. (c) We predicted that the blended treatment would be more effective for women lower in autonomy and self-efficacy and higher in sociotropy. Sociotropy moderated early response to treatment - participants in Blended-ABCT had significantly lower average PDH across treatment weeks 1–8 compared to women in the ABCT condition, if they were low in baseline sociotropy. This finding was contrary to prediction. Self-efficacy moderated post-treatment heavy drinking. As predicted, women lower in self-efficacy had a more positive response in Blended-ABCT than ABCT. (d) We predicted that Blended-ABCT and ABCT would be equally effective in impacting couple relationship satisfaction. The two treatments did not differ significantly in relationship satisfaction during or after treatment. However, there was limited support for treatment equivalence, a finding potentially explained in part by the small sample size.

ABCT is a well-supported treatment, and the present results suggest that providing women with a blend of individual and couple therapy yields outcomes that are least equivalent to a strictly couple-based treatment approach. The sample size was small, resulting in a study that was underpowered, and although effect size estimates favored Blended-ABCT over ABCT in treatment attendance and early response to treatment, growth curve analyses yielded non significant trend results in favor of blended-ABCT especially during the first half of the therapy protocol. Results support the promise of further testing of Blended ABCT in a larger sample.

The challenges of recruiting women with AUDs and their male partners to come to treatment together were evident. Women clearly preferred individual treatment when they had a choice (McCrady et al., 2011), and a minority of couples who expressed initial interest in conjoint therapy actually entered the clinical trial. Thus, providing a treatment that blends the attractive aspects of individual treatment (e.g., giving women time to talk privately about their problems) with the efficacy of conjoint treatment might be particularly appealing to women with AUDs in intimate relationships. Combining individual and couple treatment was achieved with little difficulty, and there was no suggestion that the women balked at the return of the male partner to the treatment (i.e., there was no spike in treatment dropout or increase in alcohol use at that point). We had anticipated that the blended treatment would be particularly valuable for women who were less confident (lower in self-efficacy) and autonomous and more focused on pleasing others because it would help them focus on their own needs and skills development. In contrast to prediction, the moderation analyses suggested that women who were less driven by pleasing others responded particularly well to the availability of some individual treatment, and in fact may be less well-suited to a couple therapy model in which the male spouse attends every session. It may be that the individual treatment component of Blended-ABCT fits well with the women’s pre-treatment inclination to focus on themselves and worry less about pleasing others. In contrast, the drive to please others was associated with less drinking in the ABCT condition, perhaps suggesting that the desire to please others translated into a desire to please their partners.

Drinking outcomes were somewhat less favorable than in two previously reported studies of couple-based treatment for women with AUDs (McCrady et al., 2009; Schumm et al., 2014). Both previous studies reported that women maintained abstinence on about 80% of days during follow-up compared to about 60% of days in the present sample. Two factors may help to explain these findings. First, the ABCT and Blended-ABCT models both were twelve session treatments in the present study, compared to 20-sessions of ABCT (McCrady et al., 2009), or to 13 sessions of behavioral couple therapy 13 sessions of 12-step individual treatment sessions (Schumm et al., 2014). Thus, treatment intensity (in number of sessions and weeks) was much lower in the present study. It may be that the treatment dose was insufficient. In addition, although all women in the present study agreed to the defined treatment goal of abstinence, only 20 (about one-third) endorsed an abstinence goal at the beginning of the clinical screening. Women who entered treatment with a nonabstinent goal had a significantly higher PDD after treatment, which may account, in part, for the discrepancy between outcomes for this sample compared to other treatment samples.

There were limitations to the present study. First, despite extensive recruitment efforts, the sample size was smaller than projected, resulting in an under-powered study. Second, although a greater proportion of women inquiring about the study actually entered treatment than in our earlier ABCT study with women, that proportion was 39.6%, suggesting caution in generalizing the findings to the broader population of women with AUDs in intimate relationships. Third, the sample was predominantly Caucasian, educated, and economically middle-class, thus limiting the generalizability of the results to more diverse populations. Finally, although the intent of the design was to equate the two treatments on specified couple-focused interventions related to relationship enhancement and communication, treatment integrity ratings suggested that the couple therapy content and process was greater in ABCT than in the Blended-ABCT condition. However, the lesser exposure to couple therapy interventions did not disadvantage women in Blended-ABCT in either drinking or relationship outcomes.

Despite these limitations, the study had a number of important strengths. The study was designed to maximize internal validity by carefully specifying the study population, procedures, and intervention; randomization techniques were used to balance the groups on variables known to affect treatment outcomes; therapists provided treatment in both conditions, thus minimizing potential confounding of therapist and treatment effects; we used reliable and valid measures of treatment integrity, drinking behavior, and other psychological factors; therapists showed good adherence to the treatments; and interviewers and therapists were carefully trained and monitored throughout the study. Follow-up rates were high and did not differ between conditions. Finally, we used GLMM to model outcomes, which better accounts for the distributional irregularities of PDD and PDH and has less bias and inefficiency in the presence of missing data.

Given the small sample size, clinical implications of the findings should be approached with caution, but several implications can be considered. First, the blended treatment was developed to appeal to women’s preferences for individual treatment while still preserving the positive impacts of conjoint treatment. Second, although the research design required that couples agree to conjoint treatment, in clinical practice the findings suggest that providing individual treatment initially, and then discussing male partner involvement later in treatment might be a more common way in clinical practice to engage patients in a blended ABCT treatment protocol. Third, couples find it difficult to come to treatment together on a consistent basis, and having a more flexible treatment model and blends individual and couple treatment might enhance treatment engagement and retention by decreasing that barrier to treatment.

In summary, the results of this carefully designed, small clinical trial provide support for the feasibility and efficacy of a treatment approach for women with AUDs that combines individual and conjoint cognitive behavioral therapy. Future research should focus more on the process of engaging women and their partners in treatment, as well as potential moderators and mediators of treatment outcome.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIAAA grant R37AA07070 to the first author.

The authors are grateful for the assistance of the many research assistants, therapists, and students who worked on this project.

Contributor Information

Barbara S. McCrady, Center of Alcohol Studies, Rutgers University

Elizabeth E. Epstein, Center of Alcohol Studies, Rutgers University

Kevin A. Hallgren, Department of Psychiatry, University of Washington School of Medicine

Sharon Cook, Center of Alcohol Studies, Rutgers University.

Noelle K. Jensen, Center of Alcohol Studies, Rutgers University

References

- Annis HM, Graham JM. Situational Confidence Questionnaire (SCQ-39) user’s guide. Toronto: Alcoholism and Drug Addiction Research Foundation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version 1.1–6. 2014 http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) manual. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bieling PJ, Beck AT, Brown GK. The Sociotropy-Autonomy Scale: Structure and implications. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:763–780. [Google Scholar]

- Connors GJ, Walitzer KS. Reducing alcohol consumption among heavily drinking women: Evaluating the contributions of life-skills training and booster sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:447–456. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison S, Leese M, Taylor PJ. Examination of the screening properties of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire 4+ (PDQ-4+) in a prison population. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2001;15(2):180–194. doi: 10.1521/pedi.15.2.180.19212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, Labouvie E, McCrady BS, Jensen NK, Hayaki J. A multi-site study of alcohol subtypes: Classification and overlap of unidimensional and multidimensional typologies. Addiction. 2002;97(8):1041–1053. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein EE, Menges D. Women and addiction. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, editors. Addictions: A comprehensive guidebook. 2nd. NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 788–818. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. User’s guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV Axis I Disorders - Research version. New York: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1996a. [Google Scholar]

- Fossati A, Maffei C, Bagnato M, Donati D, Donini M, Fiorelli M, et al. Criterion validity of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-41 (PDQ-41) in a mixed psychiatric sample. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1998;12:172–178. doi: 10.1521/pedi.1998.12.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff FS, Morgan TJ, Epstein EE, McCrady BS, Cook SM, Jensen NK, Kelly S. Engagement and retention in outpatient alcoholism treatment for women. American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18:277–288. doi: 10.1080/10550490902925540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Brooks AJ, Gordon SM, Green CA, Kropp F, McHugh RK, Lincoln M, Hien D, Miele GM. Substance abuse treatment entry, retention, and outcome in women: A review of the literature. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;86:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman Da. Effects of commitment to abstinence, positive moods, stress, and coping on relapse to cocaine use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:526–532. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsley J, Best M, Lefebvre M, Vito D. The seven-item short form of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale: Further evidence for construct validity. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2001;29:325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hyler SE. Personality Questionnaire, PDQ-41. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hyler SE, Skodol AE, Oldham JM, Kellman HD, Doidge B. Validity of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-Revised: A replication in an outpatient sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1992;33(2):73–77. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(92)90001-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Hoeppner BB. Does Alcoholics Anonymous work differently for men and women? A moderated multiple-mediation analysis in a large clinical sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;30:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Mudar P. Peer and partner drinking and the transition to marriage: A longitudinal examination of selection and influence processes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:115–125. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Tennen H. Network support treatment for alcohol dependence: Gender differences in treatment mechanisms and outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;45:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Wirtz PW, Zweben A, Stout RL. Network support for drinking, Alcoholics Anonymous and long-term matching effects. Addiction. 1998;93:1313–1333. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.93913133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low N, Cui L, Merikangas KR. Spousal concordance for substance use and anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2007;41:942–951. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook S, Jensen NK, Hildebrandt T. A randomized trial of individual and couple behavioral alcohol treatment for women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:243–256. doi: 10.1037/a0014686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Hirsch LS. Maintaining change after conjoint behavioral alcohol treatment for men: Outcomes at six months. Addiction. 1999;94:1381–1396. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.949138110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Cook S, Jensen NK, Ladd BO. What do women want? Alcohol treatment choices, treatment entry and retention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:521–529. doi: 10.1037/a0024037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Owens M, Brovko J. Couples and family treatment methods. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, editors. Addictions: A comprehensive guidebook, second edition. NY: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 454–481. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR. Form 90: A structured assessment interview for drinking and related behaviors. NIH Publication No. 96–4004. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC). An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. NIH Publication No. 95–3911. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Otani K, Suzuki A, Kamata M, Matsumoto Y, Shibuya N, Sadahiro R. Relationships of sociotropy and autonomy with dimensions of the Temperament and Character Inventory in healthy subjects. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2011;52:507–510. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani K, Suzuki A, Kamata M, Matsumoto Y, Shibuya N, Sadahiro R. Interpersonal sensitivity is correlated with sociotropy but not with autonomy in healthy subjects. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2012;200:153–155. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182438cba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan HS, Neidig PH, O’Leary KD. Predicting mild and severe husband-to-wife physical aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62(5):975–981. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JL, Howard KI, Vessey JT. Using significance tests to evaluate equivalence between two experimental groups. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:553–565. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumm JA, O’Farrell TJ, Kahler CW, Murphy MM, Muchowski P. A randomized clinical trial of behavioral couples therapy versus individually based treatment for women with alcohol dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:993–1004. doi: 10.1037/a0037497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobczak JA. Alcohol use and sexual function in women: A literature review. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2009;20:71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stroup WW. Rethinking the analysis of non-normal data in plant and soil science. Agronomy Journal. 2014 Retrieved from https://dl.sciencesocieties.org/publications/aj/articles/0/0/agronj2013.0342. [Google Scholar]

- Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Brown JM. The reliability of Form 90: An instrument for assessing alcohol treatment outcome. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(4):358–364. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walitzer KS, Dearing RL. Gender differences in alcohol and substance use relapse. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:128–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilberg T, Dammen T, Friis S. Comparing Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4+ with longitudinal, expert, all data (LEAD) standard diagnoses in a sample with a high prevalence of Axis I and Axis II disorders. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2000;41(4):295–302. doi: 10.1053/comp.2000.0410295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III--R (SCID): II. Multisite test-retest reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1992;49:630–636. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080038006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweig RD, McCrady BS, Epstein EE. Investigation of the psychometric properties of the Drinking Patterns Questionnaire. Addictive Disorders and Their Treatment. 2009;8:39–51. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.