Abstract

Background

Children with urinary incontinence (UI) have associated functional constipation (FC) and fecal incontinence (FI). The physiology between lower urinary tract (LUT) and anorectum in children has not been elucidated.

Aims

Observe the effect of rectal distention (RD) on LUT function, and bladder filling and voiding on anorectal function.

Methods

Children with voiding dysfunction referred to Boston Children’s Hospital were prospectively enrolled for combined urodynamic (UDS) and anorectal manometry (ARM). Anorectal and urodynamic parameters were simultaneously measured. Patients underwent 2 micturition cycles, 1st with rectal balloon deflated and 2nd with it inflated (RD). LUT and anorectal parameters were compared between cycles.

Key Results

10 children (7 UI, 4 recurrent UTIs, 9 FC ± FI) were enrolled. Post void residual (PVR) increased (p=0.02) with RD. No differences were observed in percent of bladder filling to expected bladder capacity, sensation, and bladder compliance with and without RD. Bladder and abdominal pressures increased at voiding with RD (p<0.05). Intra-anal pressures decreased at voiding (p<0.05), at 25% (p=0.03) and 50% (p=0.06) of total volume of bladder filling.

Conclusions & Inferences

The PVR volume increased with RD. Stool in the rectum does not alter filling cystometric capacity but decreases the bladder’s ability to empty predisposing patients with fecal retention to UI and UTIs. Bladder and abdominal pressures increased during voiding demonstrating a physiological correlate of dysfunctional voiding. Intra-anal pressures decreased during bladder filling and voiding. This is the first time intra-anal relaxation during bladder filling and voiding has been described.

Keywords: Anorectal manometry, urodynamics, voiding dysfunction, bowel and bladder dysfunction, fecal incontinence, constipation, children

INTRODUCTION

Bowel and bladder dysfunction commonly affect children and adults with a significant impact on their quality of life and emotional and psychological well-being (1–8). Children with incontinence experience greater psychosocial difficulties than their healthy counterparts and parents report significantly greater parental and familial stresses (7).

Lower urinary tract (LUT) dysfunction may be associated with functional constipation (FC) and functional fecal incontinence (FI). Adults (9) and children (10–12) with LUT dysfunction have an increased prevalence of FC and FI. Greater than 50% of children with LUT symptoms fulfill Rome III criteria for functional defecation disorders (13).

Conversely, children with FC and FI also have a higher prevalence of LUT symptoms (14–18). Approximately 22% of children with FC experience urinary incontinence (UI) (16) and up to 29% and 34% have day and night time urinary symptoms respectively (15). Children with FC and FI have been reported to have an increased frequency of urinary tract infections (UTIs) 11% (15) to 42.1% (12, 17) while others have a higher prevalence of both urinary frequency and urgency (17). Treatment of constipation results in a decrease in LUT symptoms and recurrent UTIs (15, 19–21). These children with both urinary and bowel symptoms have been recently labeled as having bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD) by the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS) in its newly published terminology document (22).

The pathophysiology of the interaction between the LUT and the anorectum is not precisely known. It has been suggested in limited adult studies that rectal distention may have an effect on bladder function producing variable changes in volume of sensation, bladder capacity, and bladder overactivity (23–27). Conversely, alterations in bladder filling dynamics may impact anorectal pressure and sensation (28–30), but no study has simultaneously studied changes in both systems. There is limited data regarding the physiological interaction between the LUT and the anorectum in children with BBD. This is the first study to examine the dynamic interaction between the bladder and the anorectum with and without rectal distention during bladder filling and voiding.

We hypothesize that there is a physiological interaction between the anorectum and the LUT in children. Moreover, we hypothesize that rectal distention alters bladder function during the micturition cycle of filling and voiding, and that bladder filling and voiding alter intra-anal pressure profiles and anorectal function. The aims of the present study were a) to observe the effect of rectal distention on parameters of LUT function, and b) to observe the effect of bladder filling and voiding on parameters of anorectal function.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Patient Selection

Healthy fully toilet trained children ≥ four years of age who were scheduled to have Urodynamic studies (UDS) for the evaluation of voiding dysfunction (VD) were prospectively recruited to undergo simultaneous urodynamic (UDS) and anorectal manometry (ARM). Records were reviewed to obtain demographic and clinical characteristics. Patients with anorectal, urological, systemic, neuromuscular, and spinal malformations were excluded.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston Children’s Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from each patient/family before the performance of the combined UDS and ARM study.

Study Design & Protocol

Patients underwent a combined UDS & ARM study, customized to simultaneously capture anorectal pressure changes and urodynamic parameters during this combined evaluation. Standard UDS testing includes both components of the micturition cycle, bladder filling and voiding. Bladder, abdominal, (and consequently detrusor), and urethral pressures are continuously monitored as the bladder is actively filled and when the child voids. ARM tracing depicts the rectal and intra-anal pressures in conjunction with rectal balloon distention pressures. An interface between these two systems was created to simultaneously capture the dynamic changes of the LUT and the anorectum onto a single screen. This combination allowed assessment of the dynamic changes in pressures taking place between the bladder and the anorectum as the bladder was actively filled and during voiding, with and without rectal balloon inflation.

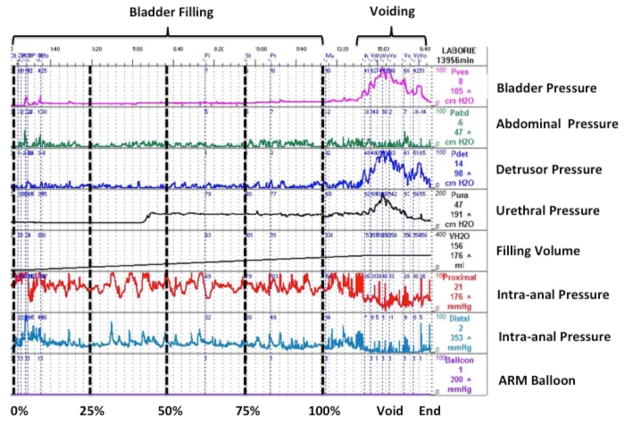

The study protocol comprised of 3 phases described in detail below: a) standard UDS b) standard ARM c) UDS in the presence of constant rectal balloon inflation (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

A: Study Protocol consisting of 3 phases (Standard UDS, ARM, UDS with rectal balloon inflation). Standard UDS: Following placement of urodynamic and anorectal catheters 1st bladder filling was started with rectal balloon deflated and cystometric and abdominal pressures measured to obtain subtracted detrusor pressure. ARM: After the patient voided and the bladder was emptied standard ARM was performed with serial balloon distensions. The smallest volume during the serial balloon inflation that produced the maximum IAS relaxation but a minimum of 60mL, if tolerated, was used for each patient. If the patient experienced pain, the volume of maximum relaxation for that specific patient for rectal distention was used during the 2nd filling phase of the study. UDS with rectal balloon inflation: After rectal balloon inflation the 2nd filling phase was begun with the same pressure recordings obtained. B: Customized interface where urodynamic and intra-anal pressure parameters are simultaneously depicted. This allows the dynamic changes in pressures between the bladder and the anorectum as the bladder is filled, during the act of voiding, and with distention of the rectal balloon to be seen. After total volume of bladder filling was completed in each patient, the volume was divided into 4 quartiles and cystometric and anorectal pressures were noted at the end of each quartile. Start of filling is represented at 0%, 25% as 1st quartile, 50% as 2nd quartile, 75% as 3rd quartile, and 100% as 4th quartile as maximum volume of instilled water.

Standard UDS - Once the urodynamic and anorectal catheters were in place bladder filling began and bladder and anorectal parameters were measured.

ARM - After the patient voided and emptied the bladder, standard baseline ARM was performed (see below). The smallest volume during serial balloon inflation that produced the maximum internal anal sphincter (IAS) relaxation was determined for each patient. The rectal balloon was then inflated to that volume for the second bladder filling (see below).

Second UDS - Once the rectal balloon was left inflated a 2nd filling of the bladder commenced at the same filling rate as before. During this filling the urodynamic and anorectal pressure parameters were measured; the rectal balloon remained inflated throughout the 2nd UDS study.

Specific Procedures

Urodynamics

Patients underwent UDS testing as previously described (31) using Triton Wireless Urodynamics Systems (Laborie Medical Technologies, Willinston VT). The machine was adapted to add 4 ports for ARM (1 for rectal pressure, 2 for intra-anal pressure, and 1 for the balloon distention). The ARM tracings were viewed simultaneously with the UDS tracings in one screen.

UDS includes a cystometrogram to determine bladder capacity, contractility, compliance, sensation, and voiding dynamics. For the study all patient were placed in the supine position. A triple-lumen 8F urodynamic catheter was inserted trans-urethrally into the child’s bladder. The intravesical pressure was recorded, the bladder drained and residual urine measured. In routine UDS the urethral and rectal catheters are used to obtain the intravesical and intra-abdominal pressures respectively. Detrusor pressure is then calculated by subtracting the intra-abdominal pressures from the intravesical pressures to correct for artifact during the study such as laughing, coughing, and movement. In our study we substituted the rectal catheter with an anorectal manometry catheter (see below).

The bladder was filled at a rate of 10% of predicted or known capacity for age per minute with normal saline. The bladder is filled until the child has a strong urge to void, is uncomfortable, micturition occurs, detrusor pressure exceeds 40 cm H2O, the infused volume exceeds at least 150% of expected capacity, or the rate of leakage is greater than the rate of infusion. As noted above two bladder fillings were completed.

Anorectal Manometry

All patients underwent ARM as previously described (32, 33). Patients fasted overnight and were given a phosphate enema the evening prior to the procedure. Manometric studies were performed with a multilumen polyvinyl catheter continuously perfused by a low compliance pneumohydraulic pump (Model ARM2, Arndorfer Medical Specialties Inc., Greendale, WI). The catheter contained 4 distal recording ports at 1-cm intervals arrayed at 90° angles from one another. The most distal recording port was situated 3 cm from the tip of the catheter, where a non-latex balloon was attached. The balloon was connected to the recording system that denoted the time of balloon distention. Baseline measurements were set at atmospheric pressure.

The catheter was withdrawn in 0.5 cm increments until the area of maximum intra-anal resting pressure was identified and secured in place with Tegaderm and hypoallergenic tape. The manometry catheter was positioned within the most distal port in the rectum so that two pressure ports were in the area of maximum intra-anal pressure. The balloon was positioned 4 cm proximal to the high-pressure zone. Prior to securing the manometry catheter the position was confirmed by eliciting the recto-anal inhibitory reflex (RAIR) with balloon inflation.

After the patient voided and the bladder was emptied standard ARM was performed with serial balloon distention. To evaluate for RAIR a full dose response curve was obtained. The rectum was inflated and deflated with serial volumes of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 90, 120, and 180 ml. The balloon was inflated using a 60 mL syringe that was connected to the balloon via a stopcock that allowed instillation of increasing balloon volumes. Threshold of sensation (minimum balloon volume that could be felt in 2 of 3 trials) and volume at which sensation of fullness was reported, were identified. The patients were instructed to squeeze and their squeeze pressures recorded. Defecation dynamics were studied by asking the patient to bear down.

During serial balloon inflation the smallest volume that produced the maximum IAS relaxation, but a minimum of 60 mL, was determined for each patient. That volume was used for the prolonged rectal distention during the second bladder filling. If the patient experienced pain during distention with 60 mL, then < 60 mL volume that produced the maximum relaxation was used during the 2nd filling phase of the study. As previously mentioned the second UDS started once the rectal balloon was left inflated.

Data analysis

Specific urodynamics parameters assessed during bladder filling included: volume instilled that produced a first sensation, volume when a pressure rise appeared to be sustained or when there was a constant increase in detrusor pressures (electronically subtracted abdominal from intravesical pressure) during filling, maximum detrusor pressure before voiding, and the total volume instilled into the bladder. Detrusor overactivity was defined as an acute rise in pressure > 15 cm H2O compared to the baseline detrusor pressure just prior to that rise. The detrusor and intra-anal pressure characteristics during actual voiding and the post void residual at the end of the cycle defined by the residual volume in the bladder after voiding were measured.

Specific anorectal parameters assessed during bladder filling and voiding included: percent maximum IAS relaxation during void (%), time to maximum IAS relaxation in seconds (measured from start of voiding and from start of bladder filling), intra-anal pressures, and spontaneous intra-anal relaxations per minute (IAS relaxations/min) during bladder filling.

To adjust for the variability in expected bladder capacity with increasing age and to allow a uniform and comparable measurement of urodynamic and anorectal pressure profiles between patients of different ages, bladder filling was divided into four equal quartiles, based on the maximum cystometric capacity. Urodynamic and anorectal pressure parameters were measured at the end of each quartile. Start of filling is represented as 0%, 1st quartile as 25%, 2nd quartile as 50%, 3rd quartile as 75%, and 4th quartile as 100% of total volume of instilled fluid (Fig. 1B).

Expected bladder capacity (EBC) (mL) was calculated by the formula: (Age + 1) × 30 ± 30 mL. Percent bladder filling of EBC was calculated by total instilled volume divided by EBC multiplied by 100. Less than 70% of EBC was defined as small capacity bladder, >130% as large capacity bladder, and 70–130% as normal capacity bladder (22).

Statistics

Data are reported as mean ± standard error of the mean. Manometric comparisons were made using student’s t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) when indicated. Non-parametric testing (related samples Wilcoxon signed rank test) was used when indicated. Proportions were compared using X2. Statistical significance was establised as P value of < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS v 16.0 (Chicago, Illinois).

RESULTS

Patient Population

Ten children (3 male, 7 female; mean age 113.7 ± 18.7 months; range: 7–12 years of age) with voiding dysfunction were included. Their main characteristics are shown in Table 1. All ten had LUT dysfunction with symptoms of UI (n=7), urgency (n=2), frequency (n=3), and/or dysuria (n=1). Four had history of recurrent UTIs.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients

| n=10 | Mean ± SE |

|---|---|

| Age (months) | 113.7 ± 18.7 |

| Weight (kg) | 38.9 ± 5.4 |

| Height (cm) | 139.8 ± 3.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.9 ± 1.9 |

| Urinary Tract Infections [n(%)] | 4 (40) |

| Voiding Dysfunction (n(%)) | 10 (100) |

| Urinary Incontinence (UI) | 7 (70) |

| Daytime UI | 2 (20) |

| Night time UI | 0 |

| Day & Night time UI | 5 (50) |

| Urgency | 2 (20) |

| Frequency | 3 (30) |

| Dysuria | 1 (10) |

| Constipation [n(%)] | 9 (90) |

| Bowel Movements [stools/day] | 0.79 ± 0.17 |

| Functional Fecal Incontinence [n (%)] | 6 (60) |

| Fecal Incontinence [episodes/day] | 0.25 ± 0.10 |

| Bristol Scale [1 to 7] | 3.6 ± 0.3 |

| Laxatives (n) | 8 |

| Osmotic (PEG3350 0.4 to − 0.8 g/kg/day to max 34 g/day) |

8 |

| Stimulant 1-Dulcolax 5mg/day; 1- Senokot 8.6 mg/day |

2 |

BMI - body mass index.

Nine children fulfilled the Rome III criteria for FC of whom 8 were on treatment with osmotic and 2 with stimulant laxative medications, whereas 1 was not on any treatment. Six children had FI associated with stool retention (Table 1). The tenth had a history of recurrent UTIs, reported four to five bowel movements per week (Bristol scale 2–3) without associated FI and had never been on any bowel regimens.

All tolerated the study well, had no complications or side effects and no differences in urodynamic and anorectal pressure parameters according to age, sex, or BMI were found.

Urodynamics Parameters

Bladder Volumes and Post Void Residual (PVR)

There was an increase in PVR volume with RD (without RD: 14.7 ± 9.6 mL vs. 32.6 ± 12.0 mL with RD: (P=0.02)) (Fig. 2). Two of four patients with a history of recurrent UTIs had increased PVR volumes with RD on the 2nd bladder fill. There was no significant difference in total volume of bladder filling and percent of bladder volume filled for expected bladder capacity (EBC) with and without RD (Table 2).

FIGURE 2. Post Void Residual (PVR) volume with and without RD.

There was an increase in PVR volumes with RD.

Table 2.

Bladder Fill Characteristics

| Bladder Fill Characteristics | Without Rectal Distention (Mean ± SE) | With Rectal Distention (Mean ± SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Volume of Bladder Filling (mL) | 230.2 ± 30.7 | 207.1 ± 32.6 | 0.14 |

| Percent Bladder Volume Filled of EBC (%) | 71.8 ± 8.1 | 65.7 ± 8.9 | 0.26 |

| Volume of First Sensation (mL) | 127.3 ± 14.5 | 134.6 ± 23.8 | 1.00 |

| Percent of Bladder Volume Filled at First Sensation (%) | 61.1 ± 6.6 | 66.5 ± 9.4 | 0.33 |

Rectal distention did not produce significant changes in Total Volume of Bladder Filling (mL), Percent of Bladder Volume filled of EBC (%), Volume of First Sensation (mL), and Percent of Bladder Volume Filled at First Sensation (%).

EBC - expected bladder capacity

Bladder Capacity

Five of the ten had normal bladder capacity, during the 1st bladder filling. During the 2nd bladder filling RD did not produce a significant decrease in bladder capacity (without RD: 94.8 ± 3.6 % vs. 82.5 ± 11.6 % with RD: (P=0.14)). In two, RD produced a decrease in bladder capacity from normal to small. In three, RD produced a decrease in bladder capacity but stayed within the normal range.

Five of the ten had a small bladder capacity during the 1st filling of the bladder. The bladder capacity in these children did not change after RD (without RD: 48.9 ± 4.2 % vs. 48.8 ± 8.9% with RD: (P=0.9)).

Sensation

There were no significant differences in volume of first sensation and percent of bladder volume filling at first sensation with and without RD (Table 2).

Bladder Pressure and Compliance Characteristics During Bladder Fill & Void

There were no significant differences in bladder pressure characteristics during bladder fill with and without RD (Table 3). Compliance of the bladder between different quartiles of bladder filling did not reach statistical significance with and without RD (Table 3).

Table 3.

Bladder pressure characteristics during bladder filling & Compliance of bladder at different quartiles of bladder fill and start of Rise in Detrusor Pressures

| Bladder Pressure and Compliance Characteristics During Filling | Without Rectal Distention (Mean ± SE) | With Rectal Distention (Mean ± SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Infused Fluid When Rise in Pressure Occurred (%) | 51.6 ± 3.7 | 48.5 ± 5.3 | 0.62 |

| Rise in Filling Pressure (ml/cmH20) | 21.1 ± 2.5 | 17.7 ± 2.9 | 0.27 |

| Maximum Detrusor Pressure (cmH20) | 14.8 ± 2.1 | 14.2 ± 1.9 | 0.71 |

| Bladder Volume at Point of Maximum Detrusor Pressure (mL) | 233.8 ± 30.8 | 199.5 ± 32.4 | 0.2 |

| Fill Pressure at Point of Maximum Detrusor Pressure (mL/cmH20) | 16.1 ± 1.9 | 15.0 ± 2.0 | 0.56 |

| Change in Bladder Pressure from Rise in Pressure to Point of Maximum Detrusor Pressure (cmH20) | 9.3 ± 2.1 | 9.2 ± 1.8 | 0.95 |

| Compliance of Bladder (mL/cmH20) (based on % of filling to capacity) | |||

| 0%– 25 % (1st quartile) | 29.6 ± 8.1 | 15.7 ± 2.0 | 0.58 |

| 25% – 50 % (2nd quartile) | 41.1 ± 18.4 | 51.1 ± 30.4 | 0.89 |

| 50% – 75 % (3rd quartile) | 13.3 ± 2.8 | 22.1 ± 4.3 | 0.07 |

| 75% – 100 % (4th quartile) | 11.1 ± 2.7 | 10.3 ± 1.8 | 0.50 |

| 0% – 100 % (overall) | 27.1 ± 11.9 | 15.7 ± 2.0 | 0.88 |

| 0% - Start of Rise in Detrusor Pressure | 20.8 ± 3.5 | 19.0 ± 3.7 | 0.89 |

| Start of Rise in Detrusor Pressure - 100 % | 16.4 ± 3.6 | 14.9 ± 2.9 | 0.65 |

Bladder pressures (Pves) did not significantly change with RD during any quartile of bladder volume. There was a decline in bladder pressures at 3rd quartile when the rectum was distended (P<0.05). Abdominal pressures (PAbd) did not significantly differ at different quartiles of bladder filling with and without RD. There was an increase in bladder and abdominal pressures during voiding when the rectum was distended (P<0.05) (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3. Bladder pressures (PVes) and abdominal pressures (PAbd) with (solid line) and without (staggered line) RD at different quartiles of bladder filling and during voiding.

Decline in bladder pressures at 75 % of bladder filling (3rd quartile) when the rectum was distended (P=0.047). Increase in bladder (P=0.04) and abdominal (P=0.047) pressures during voiding with RD.

□ - abdominal, ** - bladder

Detrusor Overactivity (DO)

Three had an overactive detrusor during bladder filling. One had DO both without and with RD, but the time to 1st DO decreased with RD (without RD: 545.9 seconds vs 522.7 seconds with RD). Another child had DO without RD but did not develop DOs with RD. The third patient did not have DO when the balloon was deflated but subsequently developed it while the balloon was inflated during the 2nd filling of the bladder.

Leak

Four had a urinary leakage during bladder filling. Two had a leak with and without RD, whereas one had a leak without RD but did not have leaking with RD; the fourth developed a leak with RD during the 2nd filling of the bladder. Time to leakage decreased with RD but was not statistically significant (without RD: 1095.1 ± 292.4 seconds vs. 1071.6 ± 297.4 seconds with RD: (P=0.66)).

Percent EBC at first evidence of urine expulsion (either void or leak) (without RD: 63.5 ± 7.4 % vs. 57.5 ± 6.3 % with RD: (P=0.24)) and time to first expulsion of urine (either void or leak) (without RD: 1001.2 ± 114.1 seconds vs. 866.2 ± 114.4 seconds with RD: (P=0.24)) did not change with RD.

Anorectal Parameters

All patients had a normal baseline ARM including normal defecation dynamics and the presence of normal RAIR. The mean balloon volume used for the prolonged rectal distention during the 2nd UDS was 56 ± 2.1 mL. In three the balloon could only be inflated to < 60 mL due to intolerance [40 mL (n=1) and 50 mL (n=2)]. These three had maximum IAS relaxation with the volume of balloon inflation used during the second fill of the bladder. The IAS relaxation fully recovered in everyone during the prolonged rectal distention with the volume used, and the IAS pressures returned to baseline prior to start of second UDS. Patients did not report rectal sensation or urge to defecate during bladder filling.

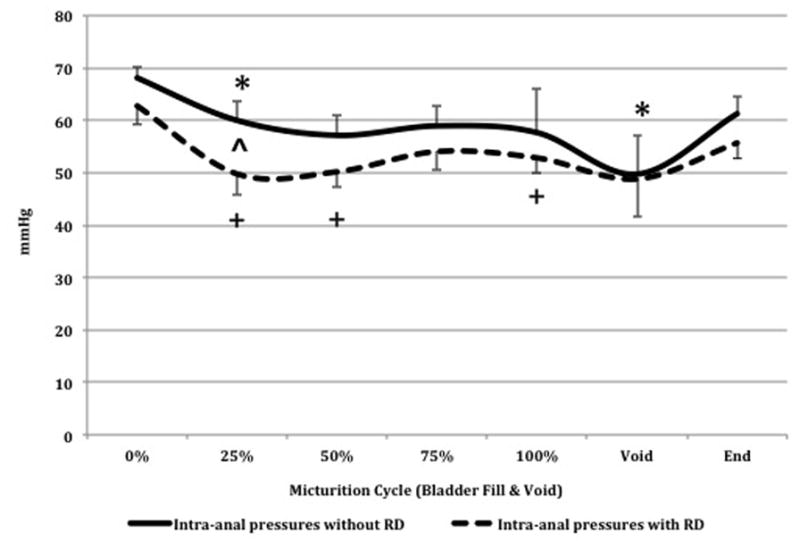

Intra-anal pressures profiles during bladder filling without balloon inflation

When the rectum was not distended, there was an overall decrease in intra-anal pressures during bladder filling. When compared to start of bladder filling the intra-anal pressures were lower at 1st quartile (P=0.03) and almost significantly lower at 2nd quartile (P=0.06) (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4. Intra-anal pressures with (solid line) and without (staggered line) (RD) at different quartiles of bladder filling and during voiding.

During bladder filling there was an overall decrease in intra-anal pressures from start of bladder fill to void, with and without RD.

^- significant difference in IAS pressures during bladder filling and voiding with and without RD.

* - significant difference in IAS pressures from start of bladder fill to different quartiles of bladder fill and during voiding when the rectum is not distended.

+ - significant difference in IAS pressures from start of bladder fill to different quartiles of bladder fill and during voiding when the rectum is distended.

Bladder pressures increased from 0.07 ± 0.9 cmH20 at start of bladder fill to 42.4 ± 4.3 cmH20 at voiding (P<0.05). Additionally, there was a simultaneous increase in abdominal pressures, though not statistically significant, (P=0.24) and a decrease in intra-anal pressures from 68.0 ± 2.1 mmHg at start of fill to 49.7 ± 7.3 mmHg at voiding (P<0.05) (Fig. 4). There were no significant differences in number of spontaneous intra-anal relaxations per minute during bladder filling at different quartiles when compared to start of bladder filling.

Intra-anal pressure profiles during bladder filling and sustained balloon inflation

When the rectum was distended, during the 2nd UDS, there was an overall decrease in intra-anal pressures during bladder filling. When compared to start of bladder filling the intra-anal pressures were significantly lower at 1st, 2nd, and 4th quartiles of bladder filling (Fig. 4).

Bladder pressures increased from 1.35 ± 0.7 cmH20 at start of bladder filling to 62.1 ± 9.2 cmH20 at voiding (P<0.05). In addition, there was an increase in abdominal pressures from start of filling to voiding (P=0.07) and a decrease in intra-anal pressures from 62.8 ± 3.5 mmHg to 48.8 ± 7.3 mmHg (P=0.06), but did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 4). There were no significant differences in number of spontaneous intra-anal relaxations per minute during bladder filling at different quartiles when compared to start of bladder filling.

Comparison of intra-anal pressure profiles during bladder filling with and without RD

During bladder filling the intra-anal pressures were lower at 1st quartile when the rectum was distended with the balloon (without RD: 60.0 ± 3.8 mmHg vs. 49.8 ± 4.0 mmHg with RD (P=0.007)). There were no significant changes in intra-anal pressures between other quartiles and during voiding with and without RD (Fig. 4). There were no significant differences in specific intra-anal pressure profiles with and without RD during voiding (Table 4). There was no significant difference in number of spontaneous intra-anal relaxations per minute during bladder filling with and without RD at different quartiles.

Table 4.

Intra-anal pressure profiles during Voiding

| Anorectal Parameters During Voiding | Without Rectal Distention (Mean ± SE) | With Rectal Distention (Mean ± SE) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-anal Pressure at Maximum Bladder Pressure During Void (mmHg) | 55.3 ± 9.6 | 62.8 ± 8.7 | 0.52 |

| Bladder Pressure at Maximum Anal Relaxation During Void (cmH20) | 33.1 ± 9.0 | 39.7 ± 9.6 | 0.21 |

| Percent Maximum Anal Relaxation During Void (%) | 61.7 ± 6.4 | 58.8 ± 6.9 | 0.52 |

| Time to Maximum Anal Relaxation from Start of Bladder Fill (minutes) | 17.9 ± 2.5 | 15.1 ± 1.9 | 0.26 |

| Time to Maximum Anal Relaxation from Start of Void (minutes) | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.68 |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine simultaneously the dynamic interaction between the bladder and the anorectum with and without RD during bladder filling and voiding. Our study establishes a physiological correlate of voiding dysfunction (VD). We have demonstrated that RD, mimicking stool, during the micturition cycle results in significantly increased PVR, a trend towards decreased bladder filling capacity, and increased bladder and abdominal pressures during voiding. We have shown that RD does not alter bladder compliance and sensation. Our findings also demonstrate a decrease in intra-anal pressures during bladder filling. Moreover, there is a significance decrease in intra-anal pressures during voiding, which has never been reported in children or adults.

One important finding is that children with VD were found to have increased PVR when the rectum was distended. Moreover, 2 of 4 children with a history of recurrent UTIs had increased PVR with RD. It has been shown that children with VD have decreased bladder emptying and increased PVR predisposing them to UTIs (34). The presence and degree of fecal loading on abdominal radiographs has been associated with the number of UTIs (35). Effective treatment of constipation has lead to decreased bladder residue on ultrasound (36), PVR (19), and incidence of UTIs (15). Our findings support the hypothesis that in children with VD, the presence of stool in the rectum results in increased PVR that may predispose them to recurrent UTIs. We demonstrate a possible physiologic explanation of the association between constipation and recurrent UTIs.

We demonstrated an overall trend towards a decreased maximum cystometric bladder capacity and a lower percent of bladder filling compared to EBC during RD; however, this did not reach statistical significance, probably due to our small sample size. Burgers et al. did not find any predictable trend in bladder capacity with RD in their cohort of 26 children with LUT symptoms with and without constipation (24). Conversely, adult studies have demonstrated a 26% decrease in cystometric bladder capacity when the rectum was distended with a balloon (23).

We demonstrated an overall trend toward a decreased percent of EBC at first expulsion of urine, a decrease in time to first expulsion, and a decrease in time to leakage with RD. We had 4 children who leaked urine during bladder filling and 1 who developed leakage with RD. Our findings support a mechanical compression of the bladder by the distended rectum. A full rectum may pose a mechanical outflow obstruction and may account for decreased bladder capacity and ineffective bladder emptying. Dohil et al. used ultrasound to demonstrate increased bladder residue and upper urinary tract dilation in their cohort of constipated children that improved after treatment (36). Our findings provide the first physiological evidence that RD has an effect on bladder function.

We demonstrated that when the rectum was distended children had significantly increased bladder and abdominal pressures during voiding. They have to generate higher bladder pressures, possibly straining more, as represented by the higher abdominal pressures, in order to void. Distention of the rectum with a fecal bolus creates a degree of dysfunctional voiding which represents the physiological basis for bowel and bladder dysfunction. It supports the findings that when the colon or rectum is decompressed this produces a significant reduction of LUT symptoms without altering intrinsic bladder function (15, 19–21, 37).

We did not observe any changes in total bladder compliance or compliance at different quartiles of bladder filling with RD. These findings are in concert with adult studies (25) and with those of Burgers et al where RD with barostat during UDS did not reveal a predictable change in bladder compliance (24). These findings suggest a mechanical effect of full rectum on bladder function.

Mechanical compression of the bladder by the fecal load may cause an outflow obstruction. Alternatively, neuronal cross-talk between the bladder and the anorectum may play a role. This interaction has been explored in animal models involving cats (38, 39) and rats (40, 41) where RD inhibits detrusor contraction during bladder filling. Anal stimulation (42) and RD (27) in humans have demonstrated similar inhibitory effects on the bladder. The significant increase in bladder pressures in the presence of a distended rectum during voiding may be due to an underlying reflex response between the anorectum and the bladder. Clinical correlate of such a neurological cross-talk was demonstrated by Burgers et al when deflation of the rectal balloon did not reverse the UDS changes in nearly half the patients (24). These theories need further exploration as they may have implications for patients with tethered spinal cord or myelomeningocele.

We did not find a significant difference in volume that produced the first sensation to void with RD. Our findings are in concert with those of Burgers et al in their pediatric cohort (24). Conversely, adult studies have demonstrated a decrease in bladder volume at which patients reported first sensation, first desire to void, and strong desire to void with RD (23, 25, 26).

We demonstrated, for the first time, characteristic changes in intra-anal pressure profiles during the micturition cycle. During bladder filling without RD, there was a significant decrease in intra-anal pressures during voiding and at 1st quartile of total bladder filling volume. Therefore, an inhibitory influence may exist from the LUT to the anorectum during the micturition cycle. We also observed a significant decline in intra-anal pressures, at 1st, 2nd, and 4th quartile of total filling volume, from baseline during bladder filling with RD. This may indicate decreased ability of the intra-anal pressures to accommodate as the bladder is being filled when the rectum is already distended with a fecal bolus. We speculate the possibility of a continuous negative feedback loop between the LUT and the anorectum that may explain the higher occurrence of “overflow” FI in children with VD.

There is limited data regarding the effect of bladder filling and voiding on anorectal function. Crosbie et al conducted simultaneous ARM and UDS and did not find significant changes in anal canal pressure, anal squeeze pressure, and rectal sensation (29). In contrast, Wachter et al demonstrated that adult patients with a full bladder had decreased anorectal sensation of fullness and desire to defecate, thereby concluding a sensory interaction between the two systems (30). In contrary, Buntzen et al demonstrated an excitatory vesico-anal reflex (28). More sophisticated dynamic studies are needed in children to assess the effect of bladder filling and voiding on anorectal function.

There are several limitations in our study. Our patient population consisted of children with LUT symptoms, FC, and FI associated with stool retention, as it is not ethically possible to perform combined UDS and ARM in healthy subjects. Other limitations include a lack of randomization in the order of bladder filling and RD. Given the nature of the study we wanted to ensure completion of the urodynamic portion first. It has been suggested when repeat cystometrograms are performed there is often individual habituation, with a change in the timing of when sensation responses are noted during the second fill. We believe this lack of randomization may have played a part in why we did not find significant changes in volume of first sensation, bladder compliance, presence of DO, and changes in bladder capacity between first and second fills. Further prospective studies are needed to address these concerns.

In conclusion, this is the first report to depict the dynamic interaction between the bladder and the anorectum in children using simultaneous UDS and ARM. We have shown in children with LUT symptoms, the presence of an inflated balloon in the rectum does not alter the filling capacity of the bladder but significantly decreases bladder emptying. Therefore, ineffective bladder emptying may predispose this group with fecal retention to UI and UTIs. In addition, patients generated higher bladder and abdominal pressures during voiding with RD. This may account for abnormal voiding dynamics in children with VD. We demonstrated decreased intra-anal pressures during bladder filling and voiding which could represent an underlying inhibitory influence from the LUT to the anorectum. This represents a first attempt to create a physiological correlate of VD. More studies are needed to validate our technique and hypothesis.

KEY MESSAGES.

Dynamic interaction between the bladder and the anorectum as noted during simultaneous urodynamics (UDS) and anorectal manometry (ARM). Our findings represent the first attempt at creating a physiological correlate of dysfunctional voiding.

Our aims were to observe the effect of a) rectal distention (RD) on lower urinary tract (LUT) function and b) bladder filling and voiding on anorectal function.

Children with LUT symptoms generate higher bladder and abdominal pressures during voiding and have ineffective bladder emptying when the rectum is distended demonstrating abnormal voiding dynamics that may predispose them to urgency, urinary incontinence, and urinary tract infections.

Intra-anal pressures decrease during bladder filling and voiding displaying for the first time intra-anal relaxation during the micturition cycle.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members and staff of Boston Children’s Hospital Urodynamics Facility Team of Nurses and Nursing Assistants for all their technical help and support during the study.

FUNDING:

This work was supported by a grant from National Institutes of Health, USA (K24DK082792A to Samuel Nurko MD MPH)

ABBREVIATIONS

- LUT

lower urinary tract

- UI

urinary incontinence

- UTIs

urinary tract infections

- FI

functional fecal incontinence

- FC

functional constipation

- VD

voiding dysfunction

- UDS

urodynamics

- ARM

anorectal manometry

- RD

rectal distention

- PVR

post void residual

- Pves

bladder pressure

- Pabd

abdominal pressure

- DO

detrusor overactivity

- IAS

internal anal sphincter

- RAIR

recto-anal inhibitory reflex

- BBD

bladder and bowel dysfunction

- EBC

expected bladder capacity

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

Conflict of interest: None

Potential competing interests: None

Specific author contributions:

Guarantor of the submission: Samuel Nurko

Conception, design and performance of the study: Lusine Ambartsumyan, Anees Siddiqui, Stuart Bauer, Samuel Nurko

Monitoring of data acquisition, creation of database and data cleaning: Lusine Ambartsumyan and Samuel Nurko

Analysis and interpretation: Lusine Ambartsumyan MD, Stuart Bauer, Samuel Nurko

Critical revision of manuscript: Lusine Ambartsumyan, Stuart Bauer, Samuel Nurko and Anees Siddiqui.

All listed authors have seen and have approved the submitted manuscript. All authors take full responsibility for the content of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Joinson C, Heron J, Butler U, von Gontard A. Psychological differences between children with and without soiling problems. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):1575–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joinson C, Heron J, von Gontard A. Psychological problems in children with daytime wetting. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):1985–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Weerasooriya L, Hathagoda W, Benninga MA. Quality of life and somatic symptoms in children with constipation: a school-based study. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1069–72. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thibodeau BA, Metcalfe P, Koop P, Moore K. Urinary incontinence and quality of life in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9(1):78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Dijk M, Benninga MA, Grootenhuis MA, Last BF. Prevalence and associated clinical characteristics of behavior problems in constipated children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(2):e309–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Gontard A, Baeyens D, Van Hoecke E, Warzak WJ, Bachmann C. Psychological and psychiatric issues in urinary and fecal incontinence. J Urol. 2011;185(4):1432–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe-Christensen C, Manolis A, Guy WC, Kovacevic N, Zoubi N, El-Baba M, et al. Bladder and bowel dysfunction: evidence for multidisciplinary care. J Urol. 2013;190(5):1864–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolfe-Christensen C, Veenstra AL, Kovacevic L, Elder JS, Lakshmanan Y. Psychosocial difficulties in children referred to pediatric urology: a closer look. Urology. 2012;80(4):907–12. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyndaele M, De Winter BY, Pelckmans P, Wyndaele JJ. Lower bowel function in urinary incontinent women, urinary continent women and in controls. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(1):138–43. doi: 10.1002/nau.20900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGrath KH, Caldwell PH, Jones MP. The frequency of constipation in children with nocturnal enuresis: a comparison with parental reporting. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44(1–2):19–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soderstrom U, Hoelcke M, Alenius L, Soderling AC, Hjern A. Urinary and faecal incontinence: a population-based study. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93(3):386–9. doi: 10.1080/08035250310021109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Combs AJ, Van Batavia JP, Chan J, Glassberg KI. Dysfunctional elimination syndromes--how closely linked are constipation and encopresis with specific lower urinary tract conditions? J Urol. 2013;190(3):1015–20. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgers R, de Jong TP, Visser M, Di Lorenzo C, Dijkgraaf MG, Benninga MA. Functional defecation disorders in children with lower urinary tract symptoms. J Urol. 2013;189(5):1886–91. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Ginkel R, Benninga MA, Blommaart PJ, van der Plas RN, Boeckxstaens GE, Buller HA, et al. Lack of benefit of laxatives as adjunctive therapy for functional nonretentive fecal soiling in children. J Pediatr. 2000;137(6):808–13. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.109153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loening-Baucke V. Urinary incontinence and urinary tract infection and their resolution with treatment of chronic constipation of childhood. Pediatrics. 1997;100(2 Pt 1):228–32. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loening-Baucke V. Prevalence rates for constipation and faecal and urinary incontinence. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92(6):486–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.098335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasirga E, Akil I, Yilmaz O, Polat M, Gozmen S, Egemen A. Evaluation of voiding dysfunctions in children with chronic functional constipation. Turk J Pediatr. 2006;48(4):340–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benninga MA, Buller HA, Heymans HS, Tytgat GN, Taminiau JA. Is encopresis always the result of constipation? Arch Dis Child. 1994;71(3):186–93. doi: 10.1136/adc.71.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erickson BA, Austin JC, Cooper CS, Boyt MA. Polyethylene glycol 3350 for constipation in children with dysfunctional elimination. J Urol. 2003;170(4 Pt 2):1518–20. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000083730.70185.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagstroem S, Rittig N, Kamperis K, Mikkelsen MM, Rittig S, Djurhuus JC. Treatment outcome of daytime urinary incontinence in children. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2008;42(6):528–33. doi: 10.1080/00365590802098367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borch L, Hagstroem S, Bower WF, Siggaard Rittig C, Rittig S. Bladder and bowel dysfunction and the resolution of urinary incontinence with successful management of bowel symptoms in children. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(5):e215–20. doi: 10.1111/apa.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, Chase J, Franco I, Hoebeke P, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: update report from the Standardization Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. J Urol. 2014;191(6):1863–5. e13. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panayi DC, Khullar V, Digesu GA, Spiteri M, Hendricken C, Fernando R. Rectal distension: the effect on bladder function. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30(3):344–7. doi: 10.1002/nau.20944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgers R, Liem O, Canon S, Mousa H, Benninga MA, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Effect of rectal distention on lower urinary tract function in children. J Urol. 2010;184(4 Suppl):1680–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Wachter S, Wyndaele JJ. Impact of rectal distention on the results of evaluations of lower urinary tract sensation. J Urol. 2003;169(4):1392–4. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000053393.45026.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akl MN, Jacob K, Klauschie J, Crowell MD, Kho RM, Cornella JL. The effect of rectal distension on bladder function in patients with overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31(4):541–3. doi: 10.1002/nau.21241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shafik A, Shafik I, El-Sibai O. Effect of rectal distension on vesical motor activity in humans: the identification of the recto-vesicourethral reflex. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(1):36–9. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2007.11753912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buntzen S, Nordgren S, Delbro D, Hulten L. Anal and rectal motility responses to distension of the urinary bladder in man. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10(3):148–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00298537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crosbie JJ, Eguare E, McGovern B, Keane FB. The influence of bladder filling on anorectal function. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5(3):251–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2003.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Wachter S, de Jong A, Van Dyck J, Wyndaele JJ. Interaction of filling related sensation between anorectum and lower urinary tract and its impact on the sequence of their evacuation. A study in healthy volunteers. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26(4):481–5. doi: 10.1002/nau.20384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drzewiecki BA, Bauer SB. Urodynamic testing in children: indications, technique, interpretation and significance. J Urol. 2011;186(4):1190–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morera C, Nurko S. Rectal manometry in patients with isolated sacral agenesis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37(1):47–52. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200307000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siddiqui A, Rosen R, Nurko S. Anorectal manometry may identify children with spinal cord lesions. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;53(5):507–11. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31822504e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Batavia JP, Ahn JJ, Fast AM, Combs AJ, Glassberg KI. Prevalence of urinary tract infection and vesicoureteral reflux in children with lower urinary tract dysfunction. J Urol. 2013;190(4 Suppl):1495–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blethyn AJ, Jenkins HR, Roberts R, Verrier Jones K. Radiological evidence of constipation in urinary tract infection. Arch Dis Child. 1995;73(6):534–5. doi: 10.1136/adc.73.6.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dohil R, Roberts E, Jones KV, Jenkins HR. Constipation and reversible urinary tract abnormalities. Arch Dis Child. 1994;70(1):56–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.70.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chrzan R, Klijn AJ, Vijverberg MA, Sikkel F, de Jong TP. Colonic washout enemas for persistent constipation in children with recurrent urinary tract infections based on dysfunctional voiding. Urology. 2008;71(4):607–10. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buntzen S, Nordgren S, Delbro D, Hulten L. Anal and rectal motility responses to distension of the urinary bladder in the cat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1994;49(3):261–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buntzen S, Nordgren S, Delbro D, Hulten L. Reflex interaction from the urinary bladder and the rectum on anal motility in the cat. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;54(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(94)00186-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wyndaele M, De Wachter S, De Man J, Minagawa T, Wyndaele JJ, Pelckmans PA, et al. Mechanisms of pelvic organ crosstalk: 1. Peripheral modulation of bladder inhibition by colorectal distention in rats. J Urol. 2013;190(2):765–71. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minagawa T, Wyndaele M, Aizawa N, Igawa Y, Wyndaele JJ. Mechanisms of pelvic organ cross-talk: 2. Impact of colorectal distention on afferent nerve activity of the rat bladder. J Urol. 2013;190(3):1123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kock NG, Pompeius R. Inhibition of Vesical Motor Activity Induced by Anal Stimulation. Acta Chir Scand. 1963;126:244–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]