Abstract

Background and Purpose

Patients with a cardioembolic stroke (CES) have worse outcomes than stroke patients with other causes of stroke. Among patients with CES, atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common comorbidity. Mounting data indicates that AF may relate to stroke pathogenesis beyond acute cerebral thromboembolism. We sought to determine whether AF represents an independent risk factor for stroke severity and outcome among patients with CES.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed patients with acute hemispheric CES included in an academic medical center’s stroke registry. CES was determined using the Causative Classification System of ischemic stroke. Multivariable logistic regression was used to determine whether AF was associated with 90-day outcome functional status.

Results

Our cohort included 140 patients. Of these, 52 had prevalent AF and 28 had incident AF diagnosed during their index hospitalization or within 90-days of hospital discharge. After adjustment for potential confounders or mediators, any AF (OR 2.51; 95%-CI 1.03–6.33; p=0.049), infarct volume (OR 1.03; 95%-CI 1.01–1.06; p=0.005), pre-admission mRS (OR 2.58; 95%-CI 1.66–4.01; p<0.001), and admission National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score (OR 1.17; 95%-CI 1.08–1.28; p<0.001) remained associated with an unfavorable 90-day outcome (modified Rankin Scale 2–6).

Conclusions

AF is associated with an unfavorable 90-day outcome among patients with a CES independent of established risk factors and initial stroke severity. This suggests that AF-specific mechanisms impact CES severity and functional status after CES. If confirmed in future studies, further investigation into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms may provide novel avenues to AF detection and treatment.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, cardioembolism, causative classification of stroke system, cerebral infarction, outcome

Introduction

Despite substantial progress in recognition and acute therapy, ischemic stroke remains a leading cause of disability and death worldwide and accounts for nearly 130,000 deaths in the United States annually.1 Outcomes and recommended therapeutic interventions differ according to the underlying stroke mechanism.2,3 Specifically, cardioembolic stroke (CES), accounting for approximately 1 in 5 ischemic strokes, exerts a profound societal impact, association with greater disability, higher mortality rates, and higher treatment costs as compared to patients with strokes from other causes.4–7 Moreover, the prevalence of CES is increasing among the elderly, a growing population at highest risk for incident stroke.4

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a potent risk factor for CES, conferring a 5-fold higher risk for stroke among affected individuals and its prevalence in the U.S. is expected to rise to 12 million in 2050.4,8 Large registries and trials have shown that AF-related strokes constitute the most severe ischemic stroke subtype.3,5,6,9 Yet, the majority of studies compared patients with AF-related strokes to patients with strokes deemed unrelated to cardioembolic sources; i.e., those with small or large vessel disease related strokes.5,6,9 An important remaining question is whether the risk for a unfavorable post stroke outcome after CES differs based on the underlying pathomechanism. Specifically, do patients with AF-related CES have a greater ischemic stroke severity and worse outcomes than patients with non-AF related CES? Clarifying this issue will aid to better define the pathophysiological link between AF and ischemic stroke and has the potential to enhance stroke treatment.

With the goal of better understanding the potential independent contribution of AF to the outcome after CES, we examined the associations between AF and clinical outcome 90-days post-stroke in a contemporary cohort of patients with CES mechanism admitted to the University of Massachusetts Medical Center (UMMC) between 2011 and 2014. We specifically hypothesized that patients with AF-related CES have worse outcomes than patients with non-AF related CES.

Methods

Study cohort

We retrospectively analyzed patients with acute hemispheric ischemic stroke as shown on brain MRI and included in the UMMC Stroke registry between March 2010 and March 2014. Of note, included patients have been described as part of previously published studies.10,11 We restricted analyses to patients with brain MRI to reliably determine the infarct extent and to exclude stroke mimics. Further, we excluded patients with infratentorial infarct location from the present analyses because both prevalence of atrial fibrillation and outcome predicting variables differ from supratentorial strokes.12,13 Our investigation was approved by our Institutional Review Board (#H00006964) and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waiver of informed consent granted. We adhere to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (www.strobe-statement.org).

Stroke etiology and Severity

Patient demographics, laboratory data, co-morbidities, pre-admission medications, and stroke etiology (using the Causative Classification System for ischemic stroke [CCS]14) based on diagnostic evaluation, were collected on all patients. Briefly, the CCS is a free web-based, semiautomated, evidence-based classification system. Its decision making algorithm assigns the most likely causative mechanism in a rule-based manner to 5 major categories (based on the Trial of ORG-10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment classification) patient with additional subdivision according to the weight of evidence (evident, probable, and possible) of an assignment (http://ccs.mgh.harvard.edu).14

Members of the stroke team certified in NIHSS scoring graded the severity of stroke at presentation. The mRS was assessed at discharge and 90-days after admission by a stroke-trained physician or stroke study nurse certified in mRS via in-person interview.10,15 When the mRS was unavailable, the same observers reconstructed the score from the case description, according to the mRS criteria.15 The 90-day outcome was dichotomized into favorable (mRS 0–1) vs. unfavorable (mRS 2–6).16

Study participants

We identified 316 patients with a diagnosis of acute hemispheric ischemic stroke and MRI brain imaging. Figure 1 summarizes the flow of patient exclusion. For the primary analyses, we excluded patients that had no CES mechanism (n=132), patients in whom the infarct etiology could be attributed to either a CES or a competing non-CES mechanism (e.g., concurrent ipsilesional high-grade carotid artery stenosis and AF, n=23), and patients who had an embolic stroke of undetermined source (n=21). Three patients had a recurrent stroke during the first 90-days and were excluded. Data was complete in 140 included patients for all variables except for the low density lipoprotein cholesterol (n=2 missing).

Figure 1.

Patient flow chart. AF=atrial fibrillation; CES=cardioembolic stroke mechanism; ESUS=embolic stroke of undetermined etiology; TIA=transient ischemic attack. *By 90-days.

Risk factor definitions

We determined the presence of hypertension (use of antihypertensive medications, or systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mm Hg on 2 separate occasions), hypercholesterolemia (use of lipid-lowering agents, or fasting blood total cholesterol level of ≥200 mg/dl or LDL cholesterol of ≥130 mg/dl) and diabetes mellitus (defined according to the National Diabetes Data Group and World Health Organization17). Cardiac studies included transthoracic echocardiography or transesophageal echocardiography, electrocardiography, and 30-day event monitoring. For all participants, we calculated the CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥75 years (doubled), diabetes mellitus, prior stroke/TIA (doubled), vascular disease, age 65–74 years, sex category [female]) score (range 0 to 9) based on data available in the medical record.

Diagnosis of atrial fibrillation

AF was defined according to the American Heart Association guidelines.4 Diagnosis of prevalent AF was determined based on history (documented AF on pre-admission electrocardiogram or history of oral anticoagulation for AF). Incident AF was defined as newly diagnosed AF during hospitalization or AF diagnosed between the index hospitalization and 90-day follow-up; confirmed by the absence of distinct P waves (showing replacement of consistent P waves by rapid oscillations of fibrillatory waves that varies in size, shape, and timing) with an irregular ventricular response on a standard 12-lead electrocardiography, 30-day event monitoring, implantable loop recorder, and pacemaker data as well as clinical follow-up notes for documentation of incident AF.18 For statistical purposes we dichotomized AF to absent vs. present (combined prevalent and incident).

Neuroimaging protocol

Brain MRI included T1-, T2-, and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR)-sequences as well as diffusion-weighted images (DWI) obtained on a 1.5 Tesla scanner (GE Signa; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) as previously detailed.10 In brief, DWI was obtained using echo-planar imaging with a repetition time of 8000 ms, an echo time of 102 ms, a field of view of 22×22 cm, image matrix of 128×128, slice thickness 5 mm with a 1-mm gap, and b-values of 0 s/mm2 and 1000 s/mm2. FLAIR was obtained with a repetition time of 9002 ms, an echo time of 143 ms, a field of view of 22×22 cm, image matrix of 256×224, and slice thickness 6 mm with a 1-mm gap. All images were evaluated by a neuroradiologist to confirm the presence of acute ischemic infarction.

Infarct volume assessment

DWI sequences were reviewed independently by experienced readers (N.H., J.H.) who were blinded to clinical data and follow-up scans. Lesions that were hyper-intense on DWI and hypo- or iso-intense on the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps were considered acute ischemic infarcts.10 Ischemic infarcts on DWI were manually outlined using careful windowing to achieve the maximal visual extent of the acute DWI (b1000 trace-weighted) infarct and with reference to the ADC image to avoid regions of T2 shine-through.10

Statistics

Unless otherwise stated, continuous variables are reported as mean ± S.D. or median (25th–75th quartile). Categorical variables are reported as proportions. Normality of data was examined using Shapiro-Wilk test. Between-group comparisons for continuous and ordinal variables were made with Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA by ranks as appropriate. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2-test or Fisher’s Exact test. 90-day survival was compared by Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test.

We first constructed a multivariable binary logistic regression models to determine factors that were independently associated with AF (adjusted for age, sex, vascular disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, history of ischemic stroke/TIA, and admission NIHSS).

To determine whether presence of AF was independently associated with an unfavorable post-stroke outcome at 90-days we constructed a multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for the CHA2DS2-VASc score, infarct volume, pre-admission mRS, and admission NIHSS.

To avoid model overfitting a backward elimination method (likelihood ratio) was used for all models. Collinearity diagnostics were performed (and its presence rejected) for all multivariable regression models. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit statistic was used to assess model fit.

Two-sided significance tests were used throughout and unless stated otherwise a two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics Version 22 (IBM®-Armonk, NY).

Results

Patient population

Baseline characteristics of included patients stratified by the 90-day outcome are summarized in Table 1. Supplemental Table I summarizes the baseline characteristics of included patients (n=140) vs. excluded patients that did not have a CES mechanism (n=176). Of note, among patients with a TIA as the exclusion criterion (n=104) the presumed TIA mechanism was related to large artery disease in 16 (15.4%), small vessel disease in 5 (4.8%), cardioaortic embolism in 20 (19.2%), undetermined in 48 (46.2%), and due to other determined causes in 15 (14.4%) subjects. Overall, 29 TIA patients (27.9%) had a diagnosis of AF. Compared to included CES patients, excluded TIA patients with presumed cardioaortic embolism were similarly often diagnosed with AF (57.1% vs. 75%, p=0.150).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (unadjusted) of the studied patient population as stratified by the 90-day outcome

| Characteristics | All patients (n=140) | Favorable outcome (n=76) | Unfavorable outcome (n=64) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 73 (62–85) | 72 (61–82) | 78 (68–86) | 0.014 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 80 (57%) | 34 (45%) | 46 (72%) | 0.002 |

| Evident CES | 96 (69%) | 44 (58%) | 52 (81%) | 0.003 |

| Female sex | 72 (51%) | 34 (45%) | 38 (59%) | 0.092 |

| Admission NIHSS | 6 (3–14) | 5 (2–8) | 13 (6–18) | <0.001 |

| Infarct volume, mL | 6 (2–28) | 4 (2–14) | 7 (2–66) | <0.001 |

| Left hemisphere infarction | 79 (56%) | 43 (57%) | 36 (56%) | 1.000 |

| Right hemisphere infarction | 43 (31%) | 26 (34%) | 17 (27%) | 0.362 |

| Bilateral infarcts | 18 (13%) | 7 (9%) | 11 (17%) | 0.207 |

| Admission glucose, mg/dL | 120 (101–136) | 119 (100–129) | 121 (103–154) | 0.090 |

| Admission creatinine, mg/dL | 0.95 (0.79–1.21) | 0.96 (0.82–1.21) | 0.92 (0.72–1.21) | 0.330 |

| LDL (within 24 h), mg/dl | 90 (75–117) | 89 (76–112) | 90 (73–119) | 0.814 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–4) | 4 (3–5) | 0.005 |

| Preexisting risk factors | ||||

| Congestive heart failure | 16 (11%) | 6 (8%) | 10 (16%) | 0.187 |

| Hypertension | 117 (84%) | 61 (80%) | 56 (88%) | 0.264 |

| Diabetes | 30 (21%) | 15 (20%) | 15 (23%) | 0.681 |

| Prior stroke or TIA | 25 (18%) | 9 (12%) | 16 (25%) | 0.049 |

| Vascular disease | 38 (27%) | 18 (24%) | 20 (31%) | 0.345 |

| Dyslipidemia | 70 (50%) | 37 (49%) | 33 (52%) | 0.865 |

| Preadmission medications | ||||

| Statin | 51 (36%) | 29 (38%) | 22 (34%) | 0.725 |

| Antihypertensive | 105 (75%) | 55 (72%) | 50 (78%) | 0.557 |

| Antiglycemic | 21 (15%) | 11 (15%) | 10 (16%) | 1.000 |

| Antiplatelets | 69 (49%) | 36 (47%) | 33 (52%) | 0.735 |

| Oral anticoagulant | 16 (11%) | 6 (8%) | 10 (16%) | 0.187 |

| Oral anticoagulant after stroke | 59 (42%) | 32 (42%) | 27 (42%) | 1.000 |

| Thrombolysis with rtPA | 44 (31%) | 21 (28%) | 23 (36%) | 0.361 |

| Time to rtPA, min | 58 (55–120) | 57 (54–77) | 67 (55–165) | 0.082 |

| Endovascular stroke therapy* | 8 (6%) | 4 (5%) | 4 (6%) | 1.000 |

| Pre-admission mRS | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–0) | 1 (0–2) | <0.001 |

Data are n (%) or median (25th–75th quartile); LDL=low density lipoprotein cholesterol; mRS=modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS=National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; rtPA=recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator, TIA=transient ischemic attack. Four patients were lost to follow up.

With or without intravenous rtPA.

Factors associated with AF among patients with CES

Among included patients, 97 had an evident and 43 had a probable/possible CES mechanism (Figure 1). Supplemental Table II indicates possible cardiac thromboembolic sources (except AF) for included patients.

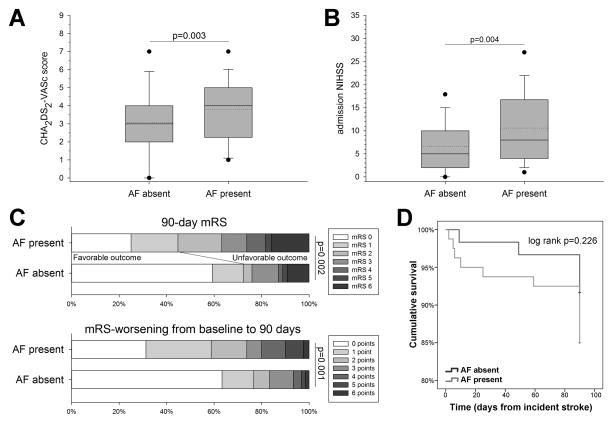

Overall, 80 patients had prevalent (n=52) or incident (n=28) AF. Patients with AF (prevalent and incident combined) were on average older (76±11 vs. 65±18 years, p<0.001), more likely to be female (60% vs. 40%, p=0.026), more likely to be treated with an anticoagulant prior to presentation (19% vs. 2%, p=0.001), and less likely to have a history of vascular disease (20% vs. 37%, p=0.035) as compared with patients that were not diagnosed with AF. In addition, patients with AF had a higher admission NIHSS (11±8 vs. 7±6 points, p=0.004; Figure 2A), a greater baseline CHA2DS2-VASc score (4 [3–5] vs. 3 [2–4] points, p=0.026; Figure 2B) as well as higher mRS at discharge (3 [1–4] vs. 2 [0–3], p=0.002) and 90-days (2 [1–4] vs. 0 [0–3], p=0.002; Figure 2C) as compared with patients without AF. To account for pre-admission functional deficits we also calculated the worsening of the mRS from baseline to 90-days. Overall, AF patients had significantly more frequent worsening in their mRS by 90-days (1 [0–3] vs. 0 [0–1] points, p=0.001, Figure 2C). There was no difference in the 90-day survival between patients with vs. without AF (p=0.226, Figure 2D). Baseline characteristics of included patients further stratified by AF status (trichotomized to no AF, prevalent AF, and newly diagnosed AF) are summarized in Supplemental Table III.

Figure 2.

Compared to patients without atrial fibrillation (AF), patients with AF had a significantly higher (A) CHA2DS2-VASc and (B) admission NIHSS score. In addition, AF patients had (C) a worse 90-day modified Rankin scale (mRS) score as well as worse 90-day mRS when adjusted for the baseline mRS (i.e., they had more frequent worsening of the mRS from baseline to 90-days). (D) There was no significant difference in the 90-day survival between patients with vs. without AF (in 6 patients with and 3 patients without AF the exact time to death could not be established and their time to death defined as 90-days). Boxes are median ± IQR, dotted lines indicate mean, whiskers indicate 10th/90th percentile and outliers are 5th/95th percentile. Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparisons of the CHA2DS2-VASc, NIHSS, 90-day mRS, and mRS-worsening from baseline to 90-days.

After adjustment for potential confounders, older age (p=0.001), higher admission NIHSS (p=0.008), and absent vascular disease (0.016) were independently associated with AF (Supplemental Table IV). Entering the CHA2DS2-VASc score instead of its individual components indicated that only an older age (p<0.001) and higher admission NIHSS (p=0.005) were independently associated with a diagnosis with AF (Supplemental Table V).

Factors associated with the 90-day outcome among patients with CES

In unadjusted analyses, older age, greater infarct volume, presence of AF, prior stroke/TIA as well as higher baseline CHA2DS2-VASc-score, worse admission NIHSS, and greater pre-admission mRS were related to an unfavorable 90-day functional status (Table 1). Figure 2 depicts the distribution of 90-day mRS as stratified by absence vs. presence of AF.

On multivariable logistic regression, AF (prevalent and incident AF combined, p=0.049), infarct volume (p=0.017), pre-admission mRS (p<0.001), and admission NIHSS (p<0.001) were independently associated with an unfavorable 90-day outcome (Table 2). We then repeated the analyses separately entering prevalent AF and incident AF as dichotomized variables. In these analyses only incident AF (OR 1.44, 95%-CI 1.01–2.05, p=0.046), but not prevalent AF (OR 2.46, 95%-CI 0.91–6.65, p=0.076), was independently associated with an unfavorable 90-day outcome.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis with backward elimination of factors independently associated with a unfavorable 90-day outcome

| Independent variable | OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | 2.51 (1.03–6.33) | 0.049 |

| Infarct volume (per mL) | 1.03 (1.01–1.06) | 0.005 |

| Admission NIHSS (per point) | 1.17 (1.08–1.28) | <0.001 |

| Pre-admission mRS (per step) | 2.58 (1.66–4.01) | <0.001 |

Hosmer-Lemeshow statistics (χ2 =7.862, p=0.447). The CHA2DS2-VASc score was not retained in this model. Results were identical when the individual components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score were entered.

Discussion

AF represents the most common serious heart rhythm problem and accounts for the majority of all CES.4,19 Importantly, AF-related strokes have been consistently found to portend a poor prognosis.3,5,6,9 Increasingly, it is understood that AF may relate to the mechanisms of, and prognosis from, acute ischemic stroke beyond the known links between AF and acute cerebral thromboembolism.20 This is an important consideration because AF-patients remain at substantial risk for cerebral infarction even when appropriately treated with oral anticoagulants, the current standard of care for secondary stroke prophylaxis.4,7

Identifying an independent contribution of AF to an unfavorable outcome after CES would indicate the existence of AF-specific factors that negatively impact post-stroke outcome. These could represent novel therapeutic targets to mitigate AF-related sequelae. Indeed, we found that among patients with CES, those with AF had significantly worse outcomes by 90-days. In line with our observation, a prior investigation reported increased mortality of AF patients compared to patients with non-AF related CES.21 However, since previous analyses were not adjusted for potential confounders it remained to be shown whether AF truly represents an independent risk factor for an unfavorable outcome after CES. In particular, AF is strongly associated with advancing age and other vascular comorbidities,4,8 which represent well-recognized risk factors for a poor post-stroke outcome.22,23 We demonstrate that the association between AF and unfavorable outcome was independent of these as well as other critical determinants of the outcome after acute ischemic stroke; namely, age, sex, infarct volume, baseline functional deficit, initial deficit severity, and AF-related vascular comorbidities.10,22,23 These results strengthen the hypothesis that the known link between AF and poor outcome after stroke involve events not directly related to known AF-related comorbidities or the embolic event per se—an observation that may serve as the impetus to further investigate potential underlying pathomechanisms. Nevertheless, given our retrospective research design and relatively small sample size our results should be considered hypothesis generating only that will require confirmation in future studies.

Precisely how AF relates to an unfavorable outcome after stroke is not well understood. It has been noted that patients with AF have lower than expected cerebral blood flow, which could contribute to impaired cerebral autoregulation and aggravate stroke severity.9 Proposed underlying mechanisms could relate to a reduced cardiac output, cardiac remodeling, or underdeveloped cerebral collateral circulation.9,24,25 Although our results are in line with prior observations that AF carries an excess risk for poor outcome independent of underlying heart disease;26 our study design did not enable us to conduct detailed electro- and echocardiographic investigations to clarify this issue. Further, studies on the robustness of cerebral collateral circulation among patients with large artery infarction did not demonstrate a significant difference between patients with vs. without AF.27 Yet, in our study the independent association of AF with the outcome remained after adjustment for both clinical (NIHSS) and imaging (infarct volume) markers of the stroke severity. Hence, it appears unlikely that reduced cerebral blood flow was a major determinant of outcome. Alternatively, AF has been associated with chronic cerebral white matter injury,28 which has been associated with decreased cerebral perfusion, greater stroke severity as well as worse overall outcome after stroke.10,11,15 The potential association between AF and chronic brain white matter injury is of further interest because AF increases the risk for cognitive impairment independent of incident stroke.29 Finally, AF might additionally impact stroke severity and thus post-stroke outcome via concomitant or resultant endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation.4,20,30

Strength of our study relate to the investigation of a well-characterized, homogenous patient population and the collection of extensive clinical information. The approach is contemporary and important and uses a robust stroke classification system that aids in minimizing rater bias by integrating multiple aspects of ischemic stroke evaluation in a probabilistic and objective manner that is increasingly used in scientific investigations relating to ischemic stroke subtypes.14 Lastly, we adjusted our analyses for key factors that have been associated with a poor post-stroke outcome including planimetrically determined infarct volumes.

Our study has several limitations. First, although our data shows a strong association between AF and outcome, a causal relationship remains to be established. Second, our sample size was modest in size and we did not have information available on pre-stroke cognitive performance, which could have impacted outcome in stroke patients. However, analyses were adjusted for the pre-stroke mRS, assuaging concerns that our results are biased by preexisting functional deficits. Not all patients without AF underwent 30-day event monitoring and few underwent long-term monitoring with implantable devices. Thus, we may have underestimated the incidence of (paroxysmal) atrial fibrillation. However, this would be expected to bias our results towards an absent difference between the groups. Hence, our analysis arguably strengthens the hypothesis that AF independently contributed to an unfavorable outcome. Although exclusion of patients with TIA may have introduced bias, this concern is assuaged by the observation that there was no difference in the presence of AF in included patients vs. excluded TIA patients with presumed cardioaortic embolism. Further, brain MRI was obtained at the discretion of the treating physician resulting in the exclusion of approximately 23% of patients (e.g., MRI was not obtained if it was not expected to alter clinical management, in the presence of contraindications, or due to patient refusal). Although this may have introduced a bias our approach is consistent with clinical practice and thus enables better generalization of our results. Additionally, restricting analyses to patients with MRI allowed for reliable exclusion of stroke mimics and rigorous adjustment for the infarct volume, which has been associated with AF and is one of the most important determinants of post-stroke outcomes.

Conclusion

AF is associated with an unfavorable 90-day functional status among patients with a CES etiology independent of established risk factors and stroke severity. This observation strongly suggests the presence of AF-specific factors that impact CES severity consistent with the currently developed model that posits AF as a marker of an underlying cardiovasculopathy that contributes to stroke risk in parallel to, but independent of, AF-related thromboembolism.31 Identifying the tissue substrate of such a cardiovasculopathy may aid in the development of novel therapeutic targets to improve CES outcomes among patients with AF and may include targeted screening in stroke patients without AF as well as decision making regarding anticoagulant therapy in CES patients in the absence of AF.31

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Dr. McManus is supported by KL2RR031981, 1R15HL121761-01A1, and 1UH2TR000921-02 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Dr. Henninger is supported by K08NS091499 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Nils Henninger Study concept and design, data acquisition, statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting the article

Ameeta Karmarkar Data acquisition, drafting the article

Johanna Helenius Data acquisition, interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Richard P. Goddeau, Jr. interpretation of data, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

David D. McManus Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.CDC, NCHS. Underlying Cause of Death 1999–2014 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released 2015. [Accessed April 1, 2015];Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999–2014, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html.

- 2.Lovett JK, Coull AJ, Rothwell PM. Early risk of recurrence by subtype of ischemic stroke in population-based incidence studies. Neurology. 2004;62:569–573. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000110311.09970.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marnane M, Duggan CA, Sheehan OC, Merwick A, Hannon N, Curtin D, et al. Stroke subtype classification to mechanism-specific and undetermined categories by TOAST, AS-C-O, and causative classification system: direct comparison in the North Dublin population stroke study. Stroke. 2010;41:1579–1586. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.575373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Jr, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:e1–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandercock P, Bamford J, Dennis M, Burn J, Slattery J, Jones L, et al. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: prevalence in different types of stroke and influence on early and long term prognosis (Oxfordshire community stroke project) BMJ. 1992;305:1460–1465. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6867.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimura K, Minematsu K, Yamaguchi T. Atrial fibrillation as a predictive factor for severe stroke and early death in 15,831 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:679–683. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.048827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal S, Hachamovitch R, Menon V. Current trial-associated outcomes with warfarin in prevention of stroke in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:623–631. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.121. discussion 631–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tu HT, Campbell BC, Christensen S, Desmond PM, De Silva DA, Parsons MW, et al. Worse stroke outcome in atrial fibrillation is explained by more severe hypoperfusion, infarct growth, and hemorrhagic transformation. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:534–540. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helenius J, Henninger N. Leukoaraiosis Burden Significantly Modulates the Association Between Infarct Volume and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale in Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2015;46:1857–1863. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henninger N, Khan MA, Zhang J, Moonis M, Goddeau RP., Jr Leukoaraiosis predicts cortical infarct volume after distal middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2014;45:689–695. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SH, Lee JY, Kim do H, Ham JH, Song YK, Lim EJ, et al. Factors related to the initial stroke severity of posterior circulation ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36:62–68. doi: 10.1159/000351512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng Q, Tao W, Lei C, Dong W, Liu M. Etiology and Risk Factors of Posterior Circulation Infarction Compared with Anterior Circulation Infarction. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:1614–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ay H, Furie KL, Singhal A, Smith WS, Sorensen AG, Koroshetz WJ. An evidence-based causative classification system for acute ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:688–697. doi: 10.1002/ana.20617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henninger N, Lin E, Baker SP, Wakhloo AK, Takhtani D, Moonis M. Leukoaraiosis predicts poor 90-day outcome after acute large cerebral artery occlusion. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;33:525–531. doi: 10.1159/000337335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lees KR, Bluhmki E, von Kummer R, Brott TG, Toni D, Grotta JC, et al. Time to treatment with intravenous alteplase and outcome in stroke: an updated pooled analysis of ECASS, ATLANTIS, NINDS, and EPITHET trials. Lancet. 2010;375:1695–1703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S81–90. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lip GY, Beevers DG. ABC of atrial fibrillation. History, epidemiology, and importance of atrial fibrillation. BMJ. 1995;311:1361–1363. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7016.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caplan LR. Brain embolism, revisited. Neurology. 1993;43:1281–1287. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.7.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsh BJ, Copeland-Halperin RS, Halperin JL. Fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, and thromboembolism: mechanistic links and clinical inferences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2239–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arboix A, Garcia-Eroles L, Massons JB, Oliveres M, Pujades R, Targa C. Atrial fibrillation and stroke: clinical presentation of cardioembolic versus atherothrombotic infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2000;73:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(99)00214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yaghi S, Sherzai A, Pilot M, Sherzai D, Elkind MS. The CHADS2 Components Are Associated with Stroke-Related In-hospital Mortality in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:2404–2407. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strbian D, Seiffge DJ, Breuer L, Numminen H, Michel P, Meretoja A, et al. Validation of the DRAGON score in 12 stroke centers in anterior and posterior circulation. Stroke. 2013;44:2718–2721. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberger JJ, Arora R, Green D, Greenland P, Lee DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Evaluating the Atrial Myopathy Underlying Atrial Fibrillation: Identifying the Arrhythmogenic and Thrombogenic Substrate. Circulation. 2015;132:278–291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamel H, O’Neal WT, Okin PM, Loehr LR, Alonso A, Soliman EZ. Electrocardiographic left atrial abnormality and stroke subtype in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:670–678. doi: 10.1002/ana.24482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin HJ, Wolf PA, Kelly-Hayes M, Beiser AS, Kase CS, Benjamin EJ, et al. Stroke severity in atrial fibrillation. The Framingham Study. Stroke. 1996;27:1760–1764. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lima FO, Furie KL, Silva GS, Lev MH, Camargo EC, Singhal AB, et al. The pattern of leptomeningeal collaterals on CT angiography is a strong predictor of long-term functional outcome in stroke patients with large vessel intracranial occlusion. Stroke. 2010;41:2316–2322. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Leeuw FE, de Groot JC, Oudkerk M, Kors JA, Hofman A, van Gijn J, et al. Atrial fibrillation and the risk of cerebral white matter lesions. Neurology. 2000;54:1795–1801. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.9.1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalantarian S, Stern TA, Mansour M, Ruskin JN. Cognitive impairment associated with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:338–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lappegard KT, Hovland A, Pop GA, Mollnes TE. Atrial fibrillation: inflammation in disguise? Scand J Immunol. 2013;78:112–119. doi: 10.1111/sji.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamel H, Okin PM, Elkind MS, Iadecola C. Atrial Fibrillation and Mechanisms of Stroke: Time for a New Model. Stroke. 2016;47:895–900. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.