Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) represent the highest burden of disease globally. Medicines are a critical intervention used to prevent and treat CVD. This review describes access to medication for CVD from a health system perspective and strategies that have been used to promote access including providing medicines at lower cost, improving medication supply, assuring medicine quality, promoting appropriate use, and managing intellectual property issues. Using key evidence in published and grey literature and systematic reviews, we summarize advances in access to cardiovascular medicines using the five health system dimensions of access: availability, affordability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of medicines. There are multiple barriers to access of cardiovascular disease medicines, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Low availability of CVD medicines has been reported in public and private health care facilities. Where patients lack insurance and pay out-of-pocket to purchase medicines, they can be unaffordable. Accessibility and acceptability are low for medicines used in secondary prevention; increasing use is positively related to country income. Fixed-dose combinations (FDC) have shown a positive effect on adherence and intermediate outcome measures such as blood pressure and cholesterol. We have a new opportunity to improve access to CVD medicines by using strategies such as efficient procurement of low cost, quality-assured generic medicines, developing FDC medicines, and by promoting adherence through insurance schemes that waive copayment for chronic medications. Monitoring progress at all levels – institutional, regional, national, and international – is vital to identify gaps in access and implement adequate policies.

Keywords: low-income countries, middle-income countries, drug therapy, drugs, access, health system, policies

Introduction

Medicines are an essential building block of a functioning health system and represent a substantial part of total health expenditure.1 The objective of this review paper is to give an overview of access to medication for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) from a health system perspective2 and describe strategies that have been used to promote access including providing medicines at lower cost, improving medication supply, assuring medicine quality, promoting appropriate use, and managing intellectual property issues.

A comprehensive systematic review is outside the scope of this paper. Instead, we summarize key evidence in published and grey literature related to advances in access to cardiovascular medicines using the five health system dimensions of access: availability, affordability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality of medicines (Table 1).

Table 1.

Five health system dimensions of access to medicines.

| Dimension | Description | Measures (examples) |

|---|---|---|

| Availability | Relationship between type/quality of medicine required and type/quality of medicine delivered. |

|

| Affordability | Ability of the user to pay for the product. |

|

| Accessibility | Ability of an individual to access care when needed. |

|

| Acceptability (adoption) | The use of medicines including appropriate prescription by providers and adherence by patients. |

|

| Quality of medicines | Medicines produced by manufacturers, authorized by the national medicines regulatory authority, that meet quality specifications set by national standards (e.g. correct dose of active ingredient, dissolution time, etc.). |

|

Burden of CVD and risk factors

CVDs represent the leading causes of death globally3 with an estimated 17.3 million deaths in 2013; representing about a quarter of all global mortality.4 Approximately 80% of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).5 Ischemic heart disease and stroke are the Number 1 and 3 causes of death, respectively, according to the Global Burden of Disease estimates of 2013.4 The rise in global CVD prevalence is rooted in part by demographic shifts (population growth and aging) as well as increased prevalence of risk factors (elevated blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, alcohol, obesity, lack of exercise, and unhealthy diet).6

LMICs bear the principle burden of other CVDs – particularly rheumatic heart disease (RHD) and heart failure. RHD is most prevalent in LMICs than in high-income countries and may affect up to 36 million people worldwide.7,8 Primary and secondary prevention programs rely on long-term penicillin therapy. Multiple registries in rural and urban low-income countries document the predominance of heart failure as the principle manifestation of CVD.9,10,11

Pharmacotherapy as prevention and treatment

In addition to lifestyle interventions to mediate modifiable risk factors, medications are integral to CVD control strategies. Blood pressure-lowering therapy using one or a combination of medications is key in the prevention and treatment of CVD. Globally, about 62% of cerebrovascular and 49% of ischemic heart disease have been attributed to suboptimal control of blood pressure.12 As abnormal blood lipids have been established as a major CVD risk factor, the development of medicines to lower lipids has had an important impact on the prevention and treatment of CVDs. Statins (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors) can reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events by 20%, where benefits of statin therapy increase with duration.14,15 Also, anti-platelet drugs such as low-dose aspirin have an important role in preventing ischemic heart disease and stroke.15 Since the mechanism of action of major pharmacotherapeutic options for CVD (blood pressure-lowering, lipid-lowering, and antiplatelet drugs) are largely independent, fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) of these effective medicines have been promoted.15

Among the “best buy” prevention and control interventions for CVD identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) is multi-drug therapy for patients with ≥30% risk of developing heart attack and stroke within 10 years.16 Such therapy includes (1) blood pressure-lowering medicines, (2) blood glucose control for patients with diabetes, (3) lipid-lowering medicines, and (4) anti-platelet medicines for secondary prevention of myocardial infarction.17,18

In LMICs, medication therapy for secondary prevention of rheumatic fever with intramuscular penicillin is cost-effective.19 Heart failure due to cardiomyopathies, hypertension, and RHD requires chronic therapy with combinations of diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and beta-blockers.20 Ideal medical therapy for the array of CVD in LIMICs will require access to several classes of CVD medicines addressing both endemic and emerging CVDs.

However, despite the clear evidence-base for medicines to prevent and treat CVD, there is a wide gap between patients in need of treatment and those who actually receive it. Several large scale studies have been conducted to estimate the access gap to CVD treatment. A literature review by Ibrahim and Damasceno21 estimates the percentage of patients diagnosed with hypertension but not adequately controlled; the authors found that only 10% out of all patients with identified hypertension had blood pressure within the target range.

Two large multi-country studies, WHO Prevention of REcurrences of Myocardial Infarction and StrokE (PREMISE)22 and Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiological (PURE) study,23 assessed the use of secondary prevention therapy for CVD predominantly in urban and rural areas of LMICs. The PREMISE study analyzed whether patients received the indicated therapy.22 The authors found that in 10 LMICs the proportions of patients with CVD who had received medications was low for beta-blockers (48% for Coronary Heart Disease, CHD), ACE inhibitors (40% for CHD and 38% for stroke) and statins (30% for CHD and 14% for stroke). The PURE study analyzed the use of five therapeutic classes in 17 LMICs among patients with known CVD. Only a quarter (25%) of CVD patients reported receiving antiplatelet drugs, 17% received beta-blockers, 20% received ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and 15% received statins.23 A country’s economic level had a greater effect on the probability of taking medicines than individual factors such as age and sex.23

Whereas the previously mentioned studies examined access across different countries, a more recent large multi-national study evaluated within-country variation in access to cardiovascular medicines.24 Analysis of household data from six countries (Cambodia, Colombia, Iran, Malawi, South Korea, and USA) showed that about two-thirds of individuals in high-income countries were receiving treatment for hypertension versus less than 50% of individuals in low- or lower-middle-income countries.24 Within-country differences were large in Colombia, Iran, Malawi, and South Korea.

Improving access to medicines for CVD is an essential component of worldwide programs to reduce the access gap to treatment for CVD.

The Five Dimensions of Access to Medicines

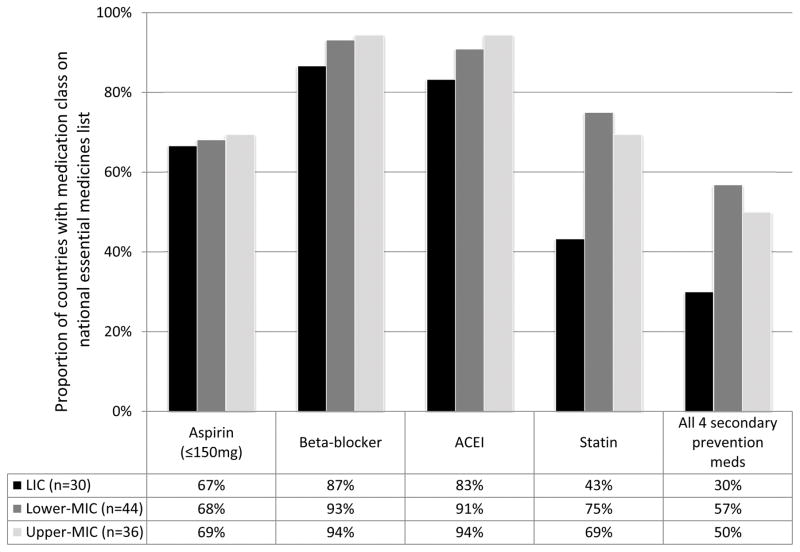

There is not one universally accepted definition of “access to medicines”. A widely used constructs describes five dimensions of access: availability, affordability, accessibility, acceptability and quality of medicines as a cross-cutting dimension (Table 1).25 Availability refers to the relationship between the type and quantity of a medicine required and type and quantity delivered; affordability refers to the ability of the user to pay for the product measured as the ratio of medicines price and household income.26 Factors impacting affordability are patent status of the medicine, market authorization requirements, and pricing and reimbursement policies, among others. Accessibility refers to the ability of the person to access medicines when in need; it considers travel distance and time, as well as opening hours of facilities, ability to be seen, etc. Acceptability, also referred to as “adoption”, describes how medicines are used in real-world settings, including their appropriate prescription by providers per evidence-based guidelines and adherence by patients.27 Finally, quality of medicines refers to the standards defined and approved by the national medicines regulatory authority such as dose of active ingredient, dissolution time for tablets, etc. A substandard medicine is produced by manufacturers, authorized by the national medicines regulatory authority that does not meet quality specifications set by national standards (e.g. inadequate dose of active ingredient, longer dissolution time, etc.).28 What medicines should be given priority when making decisions about financing and provision? The biannually updated WHO’s Model List of Essential Medicines, serves as a guide for countries to draft their own prioritized medication list to address the local health needs.29 Medicines are selected via an evidence-based process, with due regard to public health relevance, evidence on efficacy and safety and comparative cost–effectiveness, however, the latter has shown to be difficult to apply at global level.30 The current 19th Model List includes 23 different CVD medicines (Table 2).31 Over 123 countries have an essential medicines list. However, a study from 13 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa found that 40% of countries had not updated their EML in the last 5 years.32 Large differences exist among medicines included in the national EMLs that cannot be explained by variation in disease burden or clinical guidelines alone (Figure 1). We evaluated the available country essential medicines lists for presence of key medicines necessary for secondary prevention of CVD, including low-dose aspirin (≤150 mg), beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor, and statin. Countries are grouped by the World Bank Income Classification (http://data.worldbank.org/about/country-and-lending-groups). A full list of the countries included is available in Table S3 in the supplementary appendix. High-income countries are excluded as only 13 have available essential medicines lists. Whereas beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors are the therapeutic groups listed by most countries (about 90%), aspirin and statins are listed less frequently. Low-income countries in general include CVD medicines less frequently than countries of higher income groups. The lower percentage of including statins in the national EML in low income countries may be related to the lower prevalence of hyperlipidemia compared to high income settings.33 However, heart-failure specific beta blockers are less frequently listed in low income countries (17%) compared to lower middle (55%) and upper middle income countries (47%) even though heart failure among CVD patients is common in low income settings.9,10,11 Taking all four secondary prevention therapeutic groups together, only about half of the countries include at least one medicine of each group on their EMLs.

Table 2.

List of medicines included in the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines (EML).31

| Therapeutic group according to EML | International Non-proprietary name (INN) |

|---|---|

| Antithrombotic Agents | Streptokinase |

| Cardiac Glycosides | Digoxin |

| Antiarrthymics, Class I and III | Lidocaine |

| Amiodarone | |

| Cardiac Stimulants excluding Cardiac Glycosides | Dopamine |

| Epinephrine | |

| Vasodilators used in cardiac diseases | Glyceryl Trinitrate |

| Isosorbide Dinitrate | |

| Antiadrenergic Agents, Centrally Acting | Methyldopa* |

| Arteriolar Smooth Muscle Agents | Hydralazine |

| Low-Ceiling Diuretics | Hydrochlorothiazide |

| High-Ceiling Diuretics | Furosemide |

| Mannitol | |

| Potassium-Sparing Agents | Spironolactone |

| Amiloride | |

| Beta-Blocking Agents | Bisoprolol |

| Carvedilol | |

| Metropolol | |

| Selective Calcium Channel Blockers with vascular effects | Amlodipine |

| Selective Calcium Channel Blockers with direct cardiac effects | Verapamil |

| ACE Inhibitors, Plain | Enalapril |

| Lipid modifying agents | Simvastatin |

| Other analgesics and antipyretics | Acetylsalicylic acid |

| Medicines affection coagulation | Heparin sodium |

| Warfarin | |

| Beta Lactam Antibacterials † | Benzathine benzylpenicillin |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin | |

| Insulins and other medicines used for diabetes ‡ | |

| Glicazide | |

| Glucagon | |

| Insulin injection | |

| Intermediate-acting insulin | |

| Metformin |

Notes:

“Methyldopa is listed for use in the management of pregnancy-induced hypertension only. Its use in the treatment of essential hypertension is not recommended in view of the availability of more evidence of efficacy and safety of other medicines.” 31

For prevention of rheumatic heart disease.

We listed those medicines because they are included in the “best buy” strategies of the World Health Organization to reduce cardiovascular diseases. This paper focuses on access to medicines for CVD and not to specifically to these medicines.

Figure 1.

Proportion of countries with secondary prevention medication class on national essential medicines list by income status (n=110). ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; LIC, low-income country; Lower-MIC, lower-middle-income country; Upper-MIC, upper-middle-income country. High-income countries excluded.

Availability of cardiovascular medicines

To measure availability of medicines, Health Action International (HAI) together with the WHO has conducted standardized surveys in over 70 countries. The HAI/WHO methodology assesses availability during facility inspections noting whether a medicine that should be in stock is or is not physically present.34 A meta-analysis of surveys from 36 countries assessed access to five cardiovascular medicines of different classes: atenolol, captopril, hydrochlorothiazide, losartan, and nifedipine.35 The authors found cardiovascular medicines were only available in in 26% of public and 57% of private facilities.35 In general, availability of generic medicines for acute conditions was higher than for chronic conditions in both public and private sectors. For the public sector, availability was 54% for a basket of generic medicines for acute conditions and 36% for generic medicines for chronic conditions (p=0.001). For the private sector, availability was 66% for generics for acute conditions and 54% for generics for chronic conditions.36

Affordability of cardiovascular medicines

Affordable medicines should be purchased at prices that do not distress a household’s finances. Medicine prices can be compared to the international reference price: the median of the actual procurement prices for medicines offered to low-income and middle-income countries by nonprofit drug suppliers and international tender prices. It has been used widely to compare local prices to a benchmark price internationally using the HAI/WHO methodology. The HAI/WHO methodology defines “affordability” relative to the salary of the lowest paid government worker. Other methods define “unaffordable” when the total cost of medicines exceeds more than 20% of the household capacity to pay.34

The HAI/WHO standardized survey results in over 70 countries also provided relevant information on affordability of cardiovascular medicines. While the prices of government-procured generic medicines varied from 1.5- to 3-times international reference prices, the same generic products sold to patients cost about 15-times international reference prices in the public sector and about 30-times international reference prices in the private sector.37 Treatment for CVD in general was not affordable in the majority of countries, particularly in low-income countries.35 In the public sector, a 1-month supply of one generic CVD medicine cost on average 2.0 days wages and one originator brand CVD costs on average 8.3 days wages for the lowest paid government worker. Atenolol was the most affordable of all cardiovascular medicines studied (1.1 days wage). Combination therapy for CVD is largely unaffordable. Since the publication of the 2009 Cameron, et al article, nine peer-review publications reporting 20 additional surveys have demonstrated similar findings.34 Importantly, post-manufacture costs are generally borne by patients and include duties, taxes, markups, and additional charges. A recent study evaluated the affordability of combination therapy (aspirin, beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor, and statin) for the secondary prevention of CVD using a threshold of 20% of a household’s capacity-to-pay. In lower-middle- and low-income countries, a 4-drug combination was not affordable for 33% and 60% of households respectively.38

The patent status of a medicine impacts access due to effects on affordability. Medicines that are protected by patents are on average more expensive and less affordable than off-patent medicines since patented medicines generally lack market competition. According to the information from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA)39 and the European Patent Office40 there appear to be no unexpired patents on five commonly used cardiovascular medicines atenolol, captopril, hydrochlorothiazide, losartan, and nifedipine. Patents should not represent a major access barrier to CVD monotherapy in the United States and Europe. Additionally, several patented combinations of medicines in the same classes on the U.S. market (atenolol/chlorthalidone and losartan/hydrochlorothiazide) have already expired. However, there are 12 existing U.S. patents to adult and pediatric hydrochlorothiazide combinations that will expire in the next decade. The existence of patents on these combinations that include hydrochlorothiazide may also present a barrier to their affordability in other countries where such patent protection may also exist for these particular combinations (See Appendix Tables S1 and S2).

Apart from price and its relation to patents, affordability is closely related to financing. There is substantial evidence that an increase in co-payments for medicines results in a decrease in use of the medicine, however, the only evidence available comes from high-income countries.41 Most high-income countries have instituted some form of social protection where individuals are insured against large healthcare-related expenditures including the cost of medicines.

Health financing in LMICs is particularly relevant for chronic CVD medicines, where expenditures are recurrent. One example of an insurance program that includes medicines for a number of CVD in their outpatient benefit package is Seguro Popular in Mexico. A 2005 household survey showed that beneficiaries had a 50% higher probability of receiving anti-hypertensive treatment and achieving blood pressure control than non-beneficiaries.42 Selection bias may exist as enrollment in Seguro Popular is voluntary. However, as affiliation in Seguro Popular is high among previously uninsured people, it is difficult to argue that the effect of this insurance program on use of CVD medicines is purely due to motivation.

Accessibility of CVD medicines

Accessibility is another important dimension of access to medicines. Medicines may be available at affordable prices in a given region of a country. However, patients must be able to obtain the medicines.43 In some low-income countries, absenteeism of public sector health workers may be as high as 35–68%.44,45 Poor accessibility is related to suboptimal management of hypertension and secondary prevention of CAD. In Ethiopia, living within 30 minutes of a public-sector hospital was associated with improve adherence to antihypertensive therapy.46

A recent household study from five low- and middle-income countries (Uganda, Philippines, Kenya, Ghana, and Jordan) sheds light on how geographical location may influence accessibilty to medicines for non-communicable disease – though the findings are not consistent.47 Ugandan household members living in the capital had increased access to NCD medicines. One underlying reason may be long travel time to the health facility: in Uganda 35% of household had to travel longer than 15 minutes to reach a health facility. In contrast, in Jordan only 5% of households had no health facility within 15 minutes travel time. With just 16% of Ugandan households having access to medicines for NCDs it was the country with the lowest percentage, compared to Jordanian households with the highest percentage (49%).

Acceptability of cardiovascular medicines

Medicines for CVD must be acceptable both to providers and patients, and there are a host of factors affecting behavior for both groups. Patients hospitalized for acute coronary syndromes in India experience wide variation in care. Notably, patients in the lowest socioeconomic classes are less likely to receive evidence-based treatment including aspirin, beta-blockers, statins, and thrombolytics – even when treated in the same hospital as people of higher socioeconomic classes.48

One study of heart failure patients in a rural hospital in Haiti where medicines were both available and free for patients illustrates the barrier to provider acceptability. On discharge, only 21% of patients with heart failure due to cardiomyopathy were treated with the evidence-based combination of diuretic, beta-blocker, and ACE inhibitor.49 Changing provider behavior will require multifaceted approaches. A systematic review of barriers of hypertension management noted that providers frequently disagreed with clinical recommendations.50

Secondary prevention of rheumatic heart disease requires long-term penicillin, and injections are more efficacious than oral administration.51 However, due to perceived high risk of anaphylaxis with penicillin and reuse of needles, there is still resistance to using intramuscular penicillin among some providers. The perceived safety issues have even resulted in government regulations prohibiting penicillin injections in hospitals and clinics in parts of India in the past.52 Locally adapted clinical guidelines inclusive of local government and civil society organizations will be needed to improve physician acceptability in using cardiovascular medicines.

Among patients, forgetting to take one or several medicines is a key barrier to adherence.53 As CVD risk reduction requires modifying several risk factors, polypharmacy is often the norm. To address acceptability of prevention and treatment, various authors54,55,56 have suggested a combination of several cardiovascular medicines in one FDC form (“polypill”) would increase adherence, reduce delivery costs, and ease supply chain burdens. FDCs have been used successfully to treat other conditions, including human immunodeficiency virus, tuberculosis, and hypertension. Polypills with different components have been proposed for either primary or secondary prevention of CVD.53 The 2004 WHO report “Priority Medicines for Europe and the World” identified the polypill as having potential value for secondary prevention in patients with existing cardiovascular disease and recommended a research agenda.54,55 In 2009, The Indian Polycap Study (TIPS) demonstrated that a five-drug polypill was well tolerated.56 The UMPIRE trial showed a positive effect on adherence and intermediate outcome measures such as blood pressure and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels.57

Adequately powered large-scale clinical trials will be needed to detect differences in clinically important outcomes such as mortality, to assess the safety of combinations, and to evaluate unintended collateral harms – such as neglecting improved diet and exercise due to the perceived security of improved medication adherence.58 Such studies would need to be publicly funded as the components in the different polypills are all individually off patent and the cost of undertaking such large trials is likely beyond the means of generic manufacturers.59,60

Quality of cardiovascular medicines

In addition to the other four access dimensions, the risk of substandard quality and/or falsification of medicines must be managed to achieve desired health outcomes. The concern over the low quality of medicines is shared between all countries regardless of their income category.62 Substandard medicines can be defined as those produced by manufacturers, authorized by the national medicines regulatory authority, that do not meet quality specifications set by national standards (e.g. lower dose of active ingredient, longer dissolution time, etc.). However, markets with less control over imports, distribution chains, and retail outlets are more vulnerable to low quality product entry.63 Falsified medicines can be defined as those that “carry a false representation of identity, or source, or both” and many falsified medicines are also substandard.63 Quantifying the problem of substandard or falsified medicines is difficult as quantification is resource-intensive and fraught with methodological challenges such as a lack of information on market size. A study in Rwanda focusing on cardiovascular medicines that showed 2 out of 10 products purchased from private outlets were substandard.62 There are, however, multiple strategies to address substandard quality of medicines (Table 3). A discussion of each individual strategy is beyond the objectives of the paper. Instead, we provide two examples: one focusing on medicines procurement and another on the consumer. An intervention at the level of procurement is the regular quality testing carried out by large procurement agencies aimed at selecting only manufacturers or distributors that consistently supply products that pass the quality tests. A consumer-side intervention is the printing of a unique code on the product for verification. At the point of purchase, consumers can scratch off a label revealing the code that can be sent via short message service (SMS) to a central database.63 The consumer will receive an instant response verifying or refuting the product’s authenticity. For instance, medicines manufacturers selling their products on the Nigerian pharmaceutical market have used such a verification system.64

Table 3.

Selected strategies to promote the quality of medicines.

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Strengthen the capacity of National Medicines Regulatory Authorities (NMRA) | Through promoting changes in organizational processes as well as human resource training increasing the capability of the NMRA to inspect manufacturers and to promote quality of medicines. |

| Promote the prequalification program | Program supported by the World Health Organization whereby international experts collaborate with NMRAs in evaluation and inspection activities, and by building national capacity for sustainable manufacturing and monitoring of quality medicines. |

| Create business environment that is favorable for private sector to invest in secure supply chains | This can be done, for instance, through providing incentives (e.g. low interest loans or tax breaks) so that businesses are more inclined to invest in manufacturing of quality medicines. |

| Regular quality testing at procurement and sales sites | Judging quality of medicines is very difficult without specific equipment and expertise. By having organizational policies in place to procure only from certified suppliers and conduct regular quality testing reduces the risk of substandard medicines. |

| Consumer SMS and mobile application verification of product authenticity | During purchase consumers can check whether the product is authentic by sending an SMS with a unique product label number. |

Adapted from: Countering the problem of falsified and substandard drugs. Washington: Institute of Medicine, 2013. NMRA, national medicines regulatory authority; SMS, short message service.

Discussion and recommendations

Challenges

Many challenges to improving access to CVD medicines remain (Table 4). First, inequity in access to medicines is a serious barrier to achieving universal health coverage. Adoption of financial protections in the form of tax-based or obligatory insurance is one important step; though it will take many years for countries currently investing in coverage scale-up to effectively provide for all their population.65 Monitoring progress not only in terms of availability and affordability of medicines in health facilities but also in terms of equity of access is relevant. The WHO is building a consensus on indicators to measure equity in access to care, including medicines, in relation to universal health coverage.66 Even though the proportion of household income spent on medicines would be a suitable measure, it is difficult to implement due to a lack of resources to collect periodic data. However, it is expected that with the need to measure progress on universal healthcare coverage, more countries will move towards collecting healthcare-related expenditure- including medicines- from household surveys.

Table 4.

Challenges and Future Directions.

| Challenge | Suggested next step |

|---|---|

| Availability | |

| Low availability of essential medicines for CVD in public and private facilities |

|

| Affordability | |

| Markups along the medication distribution chain |

|

| Unaffordable prices |

|

| Patents/marketing combinations of non-patent medications |

|

| Lack of financing for medications |

|

| Drug manufacturer profitability |

|

| Accessibility | |

| Short hours of clinic operation |

|

| Long Waiting times |

|

| Low perceived quality of care |

|

| Acceptability | |

| Multiple medications needed for CVD prevention |

|

| Quality of medicines | |

|

|

With respect to patent protection, we note the US FDA has recently finalized a new policy which will for the first time allow new FDC drugs consisting of at least one new drug product to be eligible for five years of so-called “New Chemical Entity” market exclusivity, even if the other components of the combination have already been marketed and irrespective of any patent. For companies with existing FDC on the U.S. market, the FDA will not apply the policy retroactively.67 The patenting of FDCs for CVD will pose a challenge to generic manufacturers wishing to enter the market, especially in jurisdictions that continue, at least in the foreseeable future, to have reduced requirements for substantive patent examination (e.g., South Africa, Malaysia, France, Italy, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, and Israel).68 The Indian Patent Act69 offers a useful model, i.e., unless a new form of an already-existing CVD FDC shows increased efficacy, it should not be patentable. If it does demonstrate increased efficacy, then it is treated as an altogether new and potentially patentable substance.

Currently, donor support to finance prevention and control of NCDs, including CVD, is sparse compared to other areas, such as HIV. Unprecedented, continuous donor support for more than a decade made it possible to achieve increased access to antiretroviral therapy globally. However, only 0.6% of all development aid for health was spent on NCDs in 2010.70 Access to medicines for NCDs is lagging. The estimated costs of providing the “best buy” strategies recommended by the WHO – a multi-drug regime for individuals at high risk of CVD plus measures to prevent cervical cancer – has been estimated US$1 per person per year in low-income countries, less than US$1.5 in lower-middle income and US$2.5 in upper-middle income countries.71 Even though these might be affordable to middle-income countries, low-income countries might still depend on donor support.

Opportunities

From a health system perspective there are many important opportunities to accelerate progress to medicines access for CVD. First, 192 countries expressed their commitment to lower NCD mortality 25% by 2025. One of the key strategies to achieve this goal is to increase availability to essential medicines for the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease, in particular those medicines that are key for secondary prevention of myocardial infraction and stroke (antiplatelet drugs, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, statins). The indicator to measure this voluntary country goal is the availability of essential CVD medicines at health facilities with a target level of 80%, which means that medicines in all four of the key categories are on stock at the time of the inspection in 80 out of 100 facilities.72 Also regular monitoring using a standardized method needs to be addressed.73

Second, with respect to affordability, production costs of the large majority of cardiovascular medicines are low, making them, in theory, affordable to countries of all income levels. Promotion of low cost, quality-assured generic medicines policies is critical, not only in the public sector and within insurance schemes, but also in the private sector. At the same time it is important that production remains profitable to manufacturers. It has been reported that for some cardiovascular medicines – such as thiazide diuretics – production was abandoned in some countries because the price was too low to allow for a sufficiently large profit margin to make production attractive to the manufacturer.74

Third, regarding accessibility and acceptability, new delivery mechanisms such as the polypill for secondary prevention have the potential to increase availability, adherence, and result in higher impact on health outcomes than traditional multi-drug regimens. Some clinical trials have already shown promising results. Additionally, combination therapy might offer logical advantages: simplification in the procurement process and savings in the supply chain.

Improving access to medicines for CVD is a key strategy to substantially decrease morbidity and mortality from NCDs globally. The foundation has been laid by the countries commitment to achieve a reduction of 25% in NCD mortality by 2025. The health systems approach presented in this paper can help to develop more comprehensive strategies to achieve universal access to cardiovascular medicines in the coming years in all countries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: GFK was funded by the Research Career Development Program in Vascular Medicine (NIH/NHLBI K12HL083781).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Lu Y, Hernandez P, Abegunde D, Edejer T. World Health Organization, editor. World Medicines Situation 2011. Geneva: WHO; 2011. Chapter: Medicines Expenditure. WHO/EMP/MIE/2011.2.6. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s18767en/s18767en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bigdeli M, Jacobs B, Tomson G, Laing R, Ghaffar A, Dujardin B, Van Damme W. Access to medicines from the health system perspective. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28:692–704. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Roth GA, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Flaxman A, Murray CJ, Naghavi M. The Global Burden of Ischemic Heart Disease in 1990 and 2010: The Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014;129:1493–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ezzati M, Riboli E. Behavioral and dietary risk factors for noncommunicable diseases. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:954–964. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1203528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seckeler MD, Hoke TR. The worldwide epidemiology of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Clin Epidemiol. 2011;3:67–84. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S12977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damasceno A, Mayosi BM, Sani M, Ogah OS, Mondo C, Ojji D, Dzudie A, Kouam CK, Suliman A, Schrueder N, Yonga G, Ba SA, Maru F, Alemayehu B, Edwards C, Davison BA, Cotter G, Sliwa K. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1386–1394. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwan GF, Jean-Baptiste W, Cleophat P, Leandre F, Louine M, Luma M, Benjamin EJ, Mukherjee JS, Bukhman G, Hirschhorn LR. Descriptive epidemiology and short-term outcomes of heart failure hospitalisation in rural Haiti. Heart. 2016;102:140–146. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwan GF, Bukhman AK, Miller AC, Ngoga G, Mucumbitsi J, Bavuma C, Dusabeyezu S, Rich ML, Mutabazi F, Mutumbira C, Ngiruwera JP, Amoroso C, Ball E, Fraser HS, Hirschhorn LR, Farmer P, Rusingiza E, Bukhman G. A Simplified Echocardiographic Strategy for Heart Failure Diagnosis and Management Within an Integrated Noncommunicable Disease Clinic at District Hospital Level for Sub-Saharan Africa. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaziano T, Reddy KS, Paccaud F, Horton S, Chaturvedi V. Chapter 33: Cardiovascular Disease. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans D, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, editors. Disease Control Priority in Developing Countries. 2. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neal B. Background Paper 6.3 Ischemic heart disease. In: Kaplan W, Wirtz VJ, Mantel-Teeuwisse A, Stolk P, Duthey B, Laing R, editors. Priority Medicines for Europe and the World 2013 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuster V, Kelly BB. Promoting Cardiovascular Health in the Developing World. A critical challenge to improve global health. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Scaling up action against noncommunicable diseases: How much will it cost? Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Best buy intervention for the prevention and treatment of CVD. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortegón M, Lim S, Chisholm D, Mendis S. Cost effectiveness of strategies to combat cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and tobacco use in sub-Saharan Africa and South East Asia: mathematical modelling study. BMJ. 2012;344:e607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irlam J, Mayosi BM, Engel M, Gaziano TA. Primary prevention of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease with penicillin in South African children with pharyngitis: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:343–351. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJV, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WHW, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240–319. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibrahim MM, Damasceno A. Hypertension in developing countries. Lancet. 2012;380:611–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60861-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendis S, Abegunde D, Yusuf S, Ebrahim S, Shaper G, Ghannem H, Shengelia B. WHO study on Prevention of Recurrences of Myocardial Infarction and StrokE (WHO-PREMISE) Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:820–829. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yusuf S, Islam S, Chow CK, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Diaz R, Gupta R, Kelishadi R, Iqbal R, Avezum A, Kruger A, Kutty R, Lanas F, Lisheng L, Wei L, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Oguz A, Rahman O, Swidan H, Yusoff K, Zatonski W, Rosengren A, Teo KK Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) Study Investigators. Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2011;378:1231–1243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Cesare M, Khang YH, Asaria P, Blakely T, Cowan MJ, Farzadfar F, Guerrero R, Ikeda N, Kyobutungi C, Msyamboza KP, Oum S, Lynch JW, Marmot MG, Ezzati M Lancet NCD Action Group. Lancet. Inequalities in non-communicable diseases and effective responses. Lancet. 2013;16(381):585–597. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61851-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Medical Care. 1981;19:127–140. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Management Sciences for Health (MSH) Access to medicines and health technologies. Washington, DC: MSH; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frost L, Reich M. Access: How do good technologies get to poor people in poor countries? Chapter 2. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2008. The Access Framework. [Google Scholar]

- 28.World Health Organization. Definition of SSFFC. Availability at: http://www.who.int/medicines/regulation/ssffc/definitions/en/

- 29.World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee. Available at: http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/en/

- 30.Moucheraud C, Wirtz VJ, Reich MR. Evaluating the quality and use of economic data in decisions about essential medicines. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93:693–699. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.149914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. Available at: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/

- 32.Twagirumukiza M, Annemans L, Kips JG, Bienvenu E, Van Bortel LM. Prices of antihypertensive medicines in sub-Saharan Africa and alignment to WHO's model list of essential medicines. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:350–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. [Accessed Jan 23 2016];Raised cholesterol. Available: http://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/cholesterol_text/en/

- 34.World Health Organization/Health Action International. Medicine prices, Availability, Affordability and Price Components. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available at http://www.haiweb.org/medicineprices/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Mourik MS, Cameron A, Ewen M, Laing RO. Availability, price and affordability of cardiovascular medicines: a comparison across 36 countries using WHO/HAI data. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2010;10:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-10-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cameron A, Roubos I, Ewen M, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK, Leufkens HGM, Laing RO. Differences in the availability of medicines for chronic and acute conditions in the public and private sectors of developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:412–421. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.084327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, Ball D, Laing R. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:240–249. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khatib R, McKee M, Shannon H, Chow C, Rangarajan S, Teo K, Wei L, Mony P, Mohan V, Gupta R, Kumar R, Vijayakumar K, Lear SA, Diaz R, Avezum A, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Lanas F, Yusoff K, Ismail N, Kazmi K, Rahman O, Rosengren A, Monsef N, Kelishadi R, Kruger A, Puoane T, Szuba A, Chifamba J, Temizhan A, Dagenais G, Gafni A, Yusuf S. Availability and affordability of cardiovascular disease medicines and their effect on use in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: an analysis of the PURE study data. Lancet. 2016;387:61–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed May 20 2014];Orange book: approved drug products with therapeutic equivalence evaluations. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/Cder/ob/default.cfm.

- 40.European Patent Office. Espacenet – patent search. Available at: http://worldwide.espacenet.com/?locale=en_EP.

- 41.Lucia Luiza V, Chaves LA, Silva RM, Emmerick IM, Chaves GC, Fonseca de Araújo S, Moraes EL, Oxman AD. The effect of direct payment policies on people’s use of medicines. Cochrane Collaboration. 2015;5:CD0070172. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007017.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bleich SN, Cutler DM, Adams AS, Lozano R, Murray CJ. Impact of insurance and supply of health professionals on coverage of treatment for hypertension in Mexico: population based study. BMJ. 2007;335:875. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39350.617616.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maimaris W, Paty J, Perel P, Legido-Quigley H, Balabanova D, Nieuwlaat R, McKee M. The Influence of Health Systems on Hypertension Awareness, Treatment, and Control: A Systematic Literature Review. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Callen M, Gulzar S, Hasanain A, Khan Y. The Political Economy of Public Sector Absence: Experimental Evidence from Pakistan. Working Paper. 2014 Available at: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/publication/political-economy-public-employee-absence-experimental-evidence-pakistan.

- 45.Chaudhury N, Hammer J, Kremer M, Muralidharan K, Rogers FH. Missing in action: teacher and health worker absence in developing countries. J Econ Perspect. 2006;20:91–116. doi: 10.1257/089533006776526058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ambaw A, Alemie G, W/Yohannes S, Mengesha Z. Adherence to antihypertensive treatment and associated factors among patients on follow up at University of Gondar Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:282. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vialle-Valentin CE, Serumaga B, Wagner AK, Ross-Degnan D. Evidence on access to medicines for chronic diseases from household surveys in five low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30:1044–11052. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khatib R, Schwalm J-D, Yusuf S, Haynes RB, McKee M, Khan M, Nieuwlaat R. Patient and healthcare provider barriers to hypertension awareness, treatment and follow up: a systematic review and meta-analysis of qualitative and quantitative studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kwan GF, Jean-Baptiste W, Cleophat P, Leandre F, Louine M, Luma M, Benjamin EJ, Mukherjee JS, Bukhman G, Hirschhorn LR. Descriptive epidemiology and short-term outcomes of heart failure hospitalisation in rural Haiti. Heart. 2016;102:140–146. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manyemba J, Mayosi BM. Penicillin for secondary prevention of rheumatic fever. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(3):CD002227. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Padmavati S, Gupta V, Prakash K, Sharma KB. Penicillin for rheumatic fever prophylaxis 3-weekly or 4-weekly schedule? J Assoc Physicians India. 1987;35:753–755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khatib R, Schwalm J-D, Yusuf S, Haynes RB, McKee M, Khan M, Nieuwlaat R. Patient and healthcare provider barriers to hypertension awareness, treatment and follow up: a systematic review and meta-analysis of qualitative and quantitative studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wald N, Law M. A strategy to reduce cardiovascular disease by more than 80% BMJ. 2003;326:1419–1425. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7404.1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaplan W, Laing R. Priority Medicines for Europe and the World 2004. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Neal B. Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Fixed Dose Combinations A Research Agenda for the European Union. Background Paper. In: Kaplan W, Laing R, editors. Priority Medicines for Europe and the World. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. Available at: http://archives.who.int/prioritymeds/report/background/cardiovascular.doc. [Google Scholar]

- 56.India Polycap Study (TIPS) Effects of a polypill (Polycap) on risk factors in middle-aged individuals without cardiovascular disease (TIPS): a phase II, double-blind, randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1341–1351. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The UMPIRE Collaborative Group. Effects of a fixed-dose combination strategy on adherence and risk factors in patients with or at high risk of CVD: the UMPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(9):918–29. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lonn E, Bosch J, Teo KK, Pais P, Xavier D, Yusuf S. The polypill in the prevention of cardiovascular diseases: key concepts, current status, challenges, and future directions. Circulation. 2010;122(20):2078–2088. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.873232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaplan W, Wirtz VJ, Mantel-Teeuwisse, Stolk P, Duthey B, Laing R. Priority Medicines for Europe and the World 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Webster R, Rodgers A. Ischaemic Heart Disease Background Paper 6.3. In: Kaplan W, Wirtz VJ, Mantel-Teeuwisse, Stolk P, Duthey B, Laing R, editors. Priority Medicines for Europe and the World Report 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. available at http://www.who.int/entity/medicines/areas/priority_medicines/BP6_3IHD.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Institute of Medicine. Countering the problem of falsified and substandard drugs. Washington: IOM; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Twagirumukiza M, Cosijns A, Pringels E, Remon JP, Vervaet C, Van Bortel L. Influence of tropical climate conditions on the quality of antihypertensive drugs from Rwandan pharmacies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:776–781. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.National Collegiate Inventors and Innovator Alliance. Global Innovation Initiative. 2010 Fall;:4. Available at: http://nciia.com/sites/default/files/fall%202010.pdf.

- 64.Sproxil. About Sproxil TM. Blog. Available at: http://www.sproxil.com/blog/

- 65.Carrin G, Mathauer I, Xu K, Evans DB. Universal coverage of health services: tailoring its implementation. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:857–863. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.World Health Organization, World Bank. Tracking universal health coverage: first global monitoring report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Regulatory Affairs Professional Society. New Fixed-Dose Combination Drugs Now Eligible for 5 Years of Exclusivity, FDA Says. Available at: http://www.raps.org/Regulatory-Focus/News/2014/10/10/20544/New-Fixed-Dose-Combination-Drugs-Now-Eligible-for-5-Years-of-Exclusivity-FDA-Says/#sthash.wTysWyhG.dpuf.

- 68.Hyden MD, Racit EP. European Filing Strategies on the Eve of the Unitary Patent. EPO Practice. Full disclosure. Available at: http://www.finnegan.com/files/upload/Newsletters/Full_Disclosure/2013/March/FullDisclosure_Mar13_4.html.

- 69.The Patents Act. Chapter II- Inventions not Patentable, Section 3- What are not inventions. 1970 Available at http://ipindia.nic.in/ipr/patent/eVersion_ActRules/sections/ps3.html.

- 70.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Financing Global Health 2012: the end of a golden age. University of Washington: IHME; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 71.World Health Organization. Scaling up against non-communicable diseases: how much will it cost? Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 72.World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Robertson J, Mace’ C, Forte G, de Joncheere K, Beran D. Medicines availability for non-communicable diseases: the case for standardized monitoring. Globalization and Health. 2015;11:18–23. doi: 10.1186/s12992-015-0105-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hogerzeil HV, Liberman J, Wirtz VJ, Kishore SP, Selvaraj S, Kiddell-Monroe R, Mwangi-Powell FN, von Schoen-Angerer T Lancet NCD Action Group. Promotion of access to essential medicines for non-communicable diseases: practical implications of the UN political declaration. Lancet. 2013;381:680–689. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62128-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.