Abstract

Rates of opioid overdose and opioid-related emergency department (ED) visits have increased dramatically. Naloxone is an effective antidote to potentially fatal opioid overdose, but little is known about naloxone administration in ED settings. We examined trends and correlates of naloxone administration in ED visits nationally from 2000 to 2011. Using data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, we examined ED visits involving (1) the administration of naloxone or (2) a diagnosis of opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence. We assessed patient characteristics in these visits, including concomitant administration of prescription opioid medications. We used logistic regression to identify correlates of naloxone administration. From 2000 to 2011, naloxone was administered in an estimated 1.7 million adult ED visits nationally; 19 % of these visits recorded a diagnosis of opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence. An estimated 2.9 million adult ED visits were related to opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence; 11 % of these visits involved naloxone administration. In multivariable logistic regression models, patient age, race, and insurance and non-rural facility location were independently associated with naloxone administration. An opioid medication was provided in 14 % of visits involving naloxone administration. Naloxone was administered in a minority of ED visits related to opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence. Among all ED visits involving naloxone administration, prescription opioids were also provided in one in seven visits. Further work should explore the provider decision-making in the management of opioid overdose in ED settings and examine patient outcomes following these visits.

Keywords: Naloxone, Opioid analgesics, Drug overdose, Emergency department

Introduction

Prescribing of opioid medications in the USA quadrupled from 1999 to 2010 though this increase appears to have leveled off since 2010 [1–3]. Recent increases in opioid prescribing have occurred concurrently with rising rates of heroin use, frequent non-medical use of prescription opioids, and opioid overdose [1, 4, 5]. Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids have nearly quadrupled from 1999 to 2008, and deaths involving heroin have doubled from 2002 to 2011 [1, 6]. Increasing opioid use and overdose have resulted in increases in emergency department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, and substance use disorder treatment admissions [7–9].

To address this epidemic of opioid overdose, multiple strategies are being implemented and include maximizing prescription drug monitoring programs, supporting provider education, and expanding access to substance use disorder treatment and to naloxone, an opioid antagonist and antidote to opioid overdose [10–12]. With growing evidence of both public health impact and cost-effectiveness of naloxone, health care providers, researchers, and policymakers are increasingly supporting broader implementation of naloxone distribution [13–15]. For instance, in 2014, both the Veterans Health Administration and the Department of Justice announced plans to expand access to naloxone to prevent opioid overdose death [16, 17].

Naloxone has long been used in ED settings to diagnose and manage respiratory depression related to opioid overdose. Prior studies of ED-based naloxone use have examined clinical management following naloxone administration, provider knowledge, and facility-level availability of naloxone [18–21]. However, few studies have examined the use of naloxone in ED settings in the USA [22, 23], and none have examined nationally representative data during the decade preceding this recent support of expanded naloxone access. To address this gap, we analyzed nationally representative ED visit data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 2000 to 2011. The aims of this study were to examine trends and correlates of ED visits involving naloxone administration.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

The National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of visits to emergency departments and outpatient departments in non-institutional, general, and short-stay hospitals throughout the USA, excluding federal, military, and Veterans Administration hospitals. NHAMCS employs a four-stage sampling design to collect data from a stratified systematic sample of patient visits. Visit weights are provided by NHAMCS to account for selection probability and non-response and to facilitate national estimates of utilization of emergency medical care in the USA. NHAMCS is administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). United States Census Bureau employees act as the field agents for data collection. Field agents perform checks for data completeness, and, when necessary, missing data are imputed by the NCHS. Additional detail on NHAMCS data collection and estimation procedures is available online at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd.htm.

The NHAMCS collected survey data from 414,387 ED visits between 2000 and 2011, the most recent year currently available. The participation rate of contacted emergency departments in the NHAMCS ranged from a low of 75 % in 2008 to a high of 91 % in 2002 [24]. The NCHS institutional review board approved the protocols for the NHAMCS, including a waiver of the requirement for patient informed consent. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board determined that the current analysis of de-identified, publicly available NHAMCS data was not human subject research.

Study Population

We identified adult ED visits (age ≥ 18 years) which met either of two criteria: (1) administration of naloxone or (2) any diagnosis of opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence. The NHAMCS identifies up to eight medications administered during an ED visit or prescribed at discharge. For the first study inclusion criteria, we identified naloxone administration based on drug codes provided NHAMCS and the Lexicon Plus®, a proprietary database of Cerner Multum, Inc. The Lexicon Plus is a comprehensive database of all prescription, and some non-prescription drug products available in the US additional information on the Multum Lexicon Drug Database is available at http://www.multum.com/Lexicon.htm. The NHAMCS also records up to three diagnoses and up to three causes of injury, poisoning, or adverse effects using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]. For the second study inclusion criteria, we identified visits with a diagnosis or injury code of opioid overdose (ICD-9-CM 965.00-02, 965.09, E850.0, E850.1, E850.2, E935.1, E935.2, E935.3, E980.0) or a diagnosis of opioid abuse or dependence (ICD-9-CM 304.00-03, 304.70-73, 305.50-53). These visits included both prescription opioid medications (including methadone) and heroin.

Study Variables

Patient information includes sociodemographic data including age, gender, race (White vs. non-White), and source of payment. In addition to ICD-9-CM diagnoses, the NHAMCS provides up to three complaints, symptoms, or other reasons for the visit coded using the NCHS Reason for Visit Classification for Ambulatory Care (RVC). We created binary variables based on ICD-9-CM diagnoses and RVC codes to indicate the presence of each of several prespecified, clinically relevant conditions: any musculoskeletal pain condition, altered mental status (RVC only), any mental health condition, drug withdrawal (ICD-9-CM only), alcohol use disorder, and other non-opioid substance use disorder (i.e., cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana). We identified visits related to injuries using a dichotomous variable provided by the NHAMCS. The NHAMCS definition of injury includes all visits related to drug and alcohol use.

Available NHAMCS variables related to diagnosis, management, and disposition include length of visit (in minutes), completion of blood alcohol screen, toxicology screen (2007–2011), arterial blood gas (2005–2011), computed tomography of the head (2007–2011), administration of intravenous fluid, and hospitalization. We identified opioid medications (codeine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, meperidine, propoxyphene, hydromorphone, fentanyl) using drug codes as described above. We identified whether opioid medications were administered during the ED visit or prescribed at ED discharge among a subsample of visits from 2005 to 2011 as this data was first collected in 2005. In visits involving naloxone administration from 2005 to 2011, we identified whether naloxone was administered in the ED or prescribed at discharge (i.e., “take home” naloxone) [25]. Hospital information included hospital type (non-profit, for profit, government), geographic region, and whether the facility was in a rural area, defined as non-metropolitan statistical area per US Office of Management and Budget definition.

Data Analysis

We evaluated continuous variables with the t test and categorical variables with the chi-squared test. We compared patient and visit characteristics in three non-exclusive groups: (1) visits involving naloxone administration; (2) visits involving an opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence diagnosis; and (3) all other ED visits. We conducted pairwise comparisons of patient and visit characteristics among these three groups using the chi-squared test. In these comparisons, we categorized visits involving both an opioid-related diagnosis and naloxone administration as naloxone visits. Among visits involving naloxone administration, we examined trends in patient age, gender, and race across six 2-year time periods using the chi-squared test. We developed a multivariable logistic regression model, adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics, time period, categorized as six 2-year time periods, and the presence of an opioid-related diagnosis as defined above. This logistic regression model included all adult ED visits from 2000 to 2011 and had administration of naloxone as the dependent variable (N = 505). We present this model in two stages. Model 1 adjusts for patient and hospital characteristics as well as time period. Model 2 adjusts for all model 1 covariates plus the presence of an opioid-related diagnosis.

We performed all statistical analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC), which accounts for the complex sampling design of the NHAMCS. We utilized visit weights provided by NHAMCS to generate nationally representative estimates. The NCHS established strict release standards for data based on the relative standard error of the point estimate (≤30 %) and the absolute number of visits (≥30 sampled visits) to ensure reliability of national estimates [26]. Due to this restriction and because of the small sample size of non-White racial groups, we categorized the race variable into White and non-White race categories. All values reported meet the established release criteria for national estimates. All P values are two-tailed. We considered P < 0.05 significant.

Results

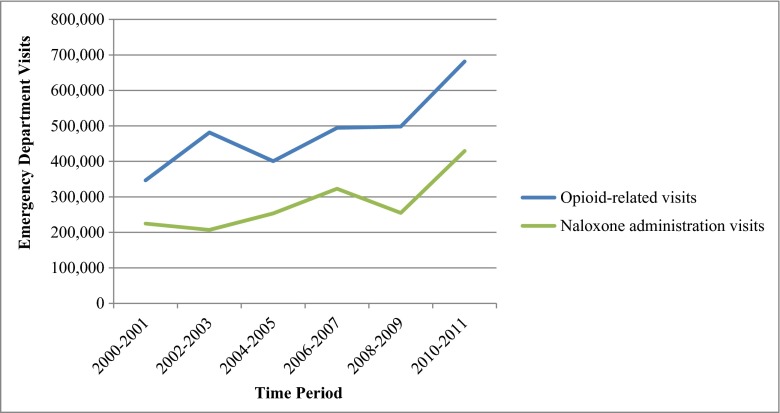

From 2000 to 2011, naloxone was administered in 505 sampled ED visits, which represent an estimated 1.7 million (95 % confidence interval [CI] 1.5 million–1.9 million) adult ED visits nationally; 19 % of these visits, or an estimated 318,000 ED visits, recorded an opioid-related diagnosis (Table 1). There were an estimated 2.9 million (95 % CI 2.6 million–3.1 million) adult ED visits related to opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence. Naloxone was administered in 10 % of these visits. An estimated 1.7 million visits (95 % CI 1.5 million–1.9 million) involved a diagnosis of opioid overdose, or 58 % of all opioid-related visits. Naloxone was administered in 16 % of these visits. Compared to opioid-related visits, patients in visits involving naloxone administration were older (mean age 47 vs. 39) and more likely to have a primary payment source of Medicare (27 vs. 12 %). ED visits involving naloxone administration increased over time from an estimated 225,000 visits in 2000–2001 to an estimated 430,000 visits in 2010–2011, a 91 % increase (Fig. 1). In prespecified analyses of sociodemographic trends among naloxone visits, patient age increased from a mean age of 43 years in 2000–2002 to 51 years in 2009–2011 (P < 0.01). Patient gender and race in these visits did not significantly change during the study period.

Table 1.

Adult ED visits involving naloxone administration and opioid-related diagnoses, USA, 2000–2011

| Naloxone administration (N = 505) | Opioid-related diagnosesa (N = 1078) | All other visitsb (N = 315,553) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimated visits | 1.7 million | 2.9 million | 896 million |

| Naloxone administration | 100 % | 11 % | 0 % |

| Any opioid-related diagnosis | 19 % | 100 % | 0 % |

| Opioid overdose diagnosis | 16 % | 58 % | 0 % |

| Age in years (mean, SD) | 47 (1.2) | 39 (0.6) | 45 (0.1) |

| Male sexc | 48 % | 57 % | 43 % |

| White race | 81 % | 84 % | 75 % |

| Insurance | |||

| Private, other insuranced | 34 % | 32 % | 44 % |

| Medicare | 27 % | 12 % | 21 % |

| Medicaid | 16 % | 27 % | 17 % |

| Self-paye | 22 % | 28 % | 18 % |

| Hospital typef | |||

| Non-profit | 76 % | 71 % | 74 % |

| Government | 15 % | 18 % | 16 % |

| For profit | 9 % | 11 % | 10 % |

| Rural location | 10 % | 8 % | 17 % |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 14 % | 27 % | 29 % |

| Midwest | 25 % | 21 % | 23 % |

| South | 33 % | 29 % | 39 % |

| West | 28 % | 23 % | 19 % |

| Time periodf | |||

| 2000–2001 | 225,000 | 347,000 | 161 million |

| 2002–2003 | 207,000 | 482,000 | 167 million |

| 2004–2005 | 254,000 | 401,000 | 169 million |

| 2006–2007 | 323,000 | 495,000 | 182 million |

| 2008–2009 | 255,000 | 498,000 | 198 million |

| 2010–2011 | 430,000 | 681,000 | 206 million |

aIncludes diagnoses of abuse, dependence, or overdose related to prescription opioids, methadone, or heroin

bVisits involved neither an opioid-related diagnosis or naloxone administration

cTwo-way comparison of visits involving naloxone administration and all other visits not statistically significant at P < 0.05

dOther insurance includes worker’s compensation, Tricare, other insurance

eIncludes self-pay, charity care, and no charge

fTwo-way comparisons to all other visits not statistically significant at P < 0.05 for both opioid-related visits and visits involving naloxone administration

Fig. 1.

Trends in adult ED visits involving naloxone administration and opioid-related diagnoses, USA, 2000–2011

On examination of co-occurring diagnoses, altered mental status was more common among ED visits involving naloxone administration compared to opioid-related visits (26 vs. 6 %; Table 2). Drug withdrawal was diagnosed in 16 % of opioid-related visits but was recorded in only two sample visits involving naloxone administration. ED visits involving naloxone administration were more likely to result in hospitalization compared to opioid-related visits (46 vs. 21 %). The proportion of visits involving naloxone administration that resulted in hospitalization increased from 42 % from 2000 to 2003 to 56 % from 2008 to 2011. ED visits involving naloxone administration were also more likely to involve each of the other management modalities examined with the exception of the provision of an opioid medication. Both an opioid medication and naloxone were provided in the same visit in an estimated 230,000 ED visits or 14 % of all visits involving naloxone administration. From 2005 to 2011, among visits involving both an opioid medication and naloxone administration, an opioid medication was administered in the ED in 92 % of visits rather than at discharge. During this time period, there was one sampled visit that recorded naloxone prescribed at discharge (i.e., take home naloxone). A nationally representative estimate cannot be reliably estimated from a single sampled visit.

Table 2.

Diagnoses, management, and disposition in adult ED visits involving naloxone administration and opioid-related diagnoses, 2000–2011

| Naloxone administration (N = 505) | Opioid-related diagnosesa (N = 1078) | All other visitsb (N = 315,553) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | |||

| Musculoskeletal pain | 8 % | 14 % | 29 % |

| Altered mental status | 26 % | 6 % | 1 % |

| Injury | 74 % | 98 % | 34 % |

| Mental illness | – | 18 % | 3 % |

| Drug withdrawal | – | 16 % | 0.1 % |

| Alcohol use disorder | 6 % | 7 % | 1 % |

| Other SUD | 25 % | 25 % | 1 % |

| Management | |||

| Any opioid medication | 14 % | 15 % | 29 % |

| Blood alcohol screen | 23 % | 17 % | 2 % |

| Toxicology screen | 43 % | 35 % | 4 % |

| Intravenous fluids | 75 % | 40 % | 29 % |

| Arterial blood gas | 21 % | 6 % | 3 % |

| Head CT | 36 % | 9 % | 8 % |

| Pregnancy test | 7 % | 4 % | 6 % |

| Length of visit in minutes (mean, SD) | 345 (20) | 298 (15) | 213 (3) |

| Disposition | |||

| Hospitalization | 46 % | 21 % | 15 % |

All two-way comparisons to “All other visits” statistically significant at P < 0.05

SUD substance use disorder, CT computed tomography, SD standard deviation, – cell size does not meet NHAMCS reliability criteria and estimate has been omitted

aIncludes diagnoses of abuse, dependence, or overdose related to prescription opioids, methadone, or heroin

bVisits involved neither an opioid-related diagnosis or naloxone administration

In a multivariable logistic regression model adjusting for patient and hospital characteristics as well as a visit diagnosis of opioid abuse, dependence, or overdose (Table 3, model 2), factors independently associated with naloxone administration included age 45–64 (vs. age ≥ 65), White race (vs. non-White race), payment source of Medicare or self-pay (vs. private insurance), and non-rural hospital location. Time period was not significantly associated with naloxone administration.

Table 3.

Correlates of naloxone administration in adult ED visits, 2000–2011

| Naloxone administration | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95 % CI) | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| Age | |||

| 18–24 | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

| 25–44 | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | 1.3 (0.9–2.1) |

| 45–64 | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 2.3 (1.5–3.4) | 1.9 (1.3–2.8) |

| 65+ | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Male sex | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) | 1.2 (0.95–1.5) |

| White race | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 1.6 (1.2–2.3) | 1.4 (1.1–2.0) |

| Insurance | |||

| Private, other insurancea | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Medicare | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 2.4 (1.7–3.5) | 2.2 (1.5–3.1) |

| Medicaid | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) |

| Self-payb | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) | 1.6 (1.1–2.1) | 1.4 (0.99–1.9) |

| Rural location | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 0.5 (0.4–0.8) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) |

| Time period | |||

| 2000–2001 | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 2002–2003 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.0 (0.7–1.7) |

| 2004–2005 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) |

| 2006–2007 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) |

| 2008–2009 | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) |

| 2010–2011 | 1.5 (0.98–2.3) | 1.7 (1.04–2.8) | 1.6 (0.99–2.7) |

| Opioid-related diagnosis | 96.7 (70.7–132.2) | – | 86.3 (61.7–120.7) |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

aIncludes worker’s compensation, Tricare, and other insurance

bIncludes self-pay, charity care, and no charge

Discussion

In this study, naloxone was administered in an estimated 1.7 million ED visits nationally from 2000 to 2011. During this same period, there were an estimated 2.9 million (95 % CI 2.6 million–3.1 million) adult ED visits related to diagnoses of opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence. Naloxone was administered in a minority (11 %) of all opioid-related ED visits and in 16 % of visits with a diagnosis of opioid overdose. Naloxone is indicated only in cases of life-threatening respiratory depression. These findings may therefore reflect ED providers’ assessments of the acuity of individual opioid-related ED visits. Additionally, we identified patient- and facility-level correlates of naloxone administration, suggesting that variation among providers and facilities may play a role in decisions to administer naloxone. After adjusting for opioid-related diagnosis, several patient and facility characteristics remained associated with naloxone administration. Our findings add to prior work identifying older age, comorbid disease, and multiple medications as predictors of naloxone administration in inpatient and postoperative settings [27–29]. Data to support a better understanding of patient-level variation in both naloxone administration and opioid overdose severity are needed and may assist providers in assessing patient-level risk of opioid-related adverse events.

A diagnosis of opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence was made in a minority (19 %) of visits in which naloxone was administered. For comparison, a recent chart review of inpatient naloxone use identified opioid-induced respiratory depression in 61 % of cases of naloxone administration [30]. Naloxone administration in the absence of an opioid-related diagnosis seen in this study may represent the clinical practice of using naloxone as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool in cases of altered mental status, intoxication or apnea of unclear etiology as well as for reversal of procedural sedation. For example, in this study, a presenting complaint of altered mental status was documented in more than one in four visits involving naloxone administration. Naloxone administration in the prehospital setting has been proposed as a surrogate for opioid overdose and as a public health surveillance tool [31]. These data suggest that a similar application may not be appropriate in ED settings. These cases of naloxone administration in the absence of an opioid-related diagnosis also point to the challenge of accurately diagnosing opioid overdose, even by trained emergency medicine providers. With increasing implementation of opioid overdose education for potential bystanders, it will be important to set attainable goals for knowledge acquisition by trainees [32] and to support systems capable of tracking the impact of overdose education programs on naloxone administration.

We identified the administration of both naloxone and an opioid pain medication in 14 % of all visits involving naloxone or an estimated 230,000 visits over 12 years. Given the limitations of NHAMCS data, we cannot distinguish between two potential explanations of this finding [26]. First, this finding may represent naloxone administration followed by an opioid medication to treat persistent acute or chronic pain. Alternatively, this finding may represent an opioid medication first and naloxone second or iatrogenic opioid overdose. Naloxone administration has previously been examined as a potential quality indicator for inpatient and postoperative pain management and may offer opportunities for monitoring the quality of pain care in ED settings [27, 30]. Importantly, both scenarios provide opportunities to improve the safety of pain care in the ED and warrant further study.

Our analysis supports earlier work examining ED utilization related to adverse effects of prescription opioids. In the most recent data available from the Drug Abuse Warning Network in 2011, there were 488,000 visits related to non-medical use of prescription opioid medications, up from 173,000 in 2004 [33]. Hasegawa et al. examined NHAMCS data to characterize trends in ED visits related to both intentional and unintentional opioid overdose and demonstrated significant increases in ED visit rates from 1993 to 2010 [34]. Our analysis adds to this prior work on visit trends by examining the use of naloxone during opioid-related visits as well as clinical management more broadly, specifically the provision of opioid medications during these visits. An opioid medication was given in 15 % of ED visits involving a diagnosis of opioid overdose, abuse, or dependence. These visits may have involved the provision of opioid medications for pain management in patients with a co-occurring diagnosis of opioid abuse, dependence, or overdose. A number of these visits may also have involved the management of withdrawal, which was diagnosed in one in six opioid-related ED visits. However, we were not able to examine the provision of opioid medications in these visits as the small number of sampled visits did not meet NHAMCS reliability criteria. Greater attention to the risks of prescription opioids in long-term therapy may increase the incidence of dose reduction or discontinuation in the years ahead in spite of little evidence to guide these efforts [35]. Expert guidelines on opioid discontinuation specifically recommend against treating withdrawal with additional opioid medications though a more comprehensive approach may be challenging in ED settings [36]. Further study is needed to characterize the management of opioid withdrawal in the opioid-related ED utilization described in this study.

These estimates of ED-based naloxone administration likely underestimate the overall impact of naloxone as community-based, or prehospital naloxone administration by bystanders or first responders is not captured in NHAMCS data. Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs reported providing naloxone to more than 50,000 individuals nationally from 1996 to 2010, resulting in more than 10,000 overdose “reversals” [37]. An analysis of data from a metropolitan emergency medical service provider demonstrated three prehospital encounters in which naloxone was administered for every two ED visits involving an opioid overdose diagnosis [31]. The network of potential sources of naloxone will likely grow more complex as additional institutions such as law enforcement and outpatient medical settings consider a larger role [16, 38]. Further study should seek to integrate data sources from these multiple potential sites of naloxone distribution or administration and to identify effective strategies for coordinating these efforts.

These findings should be interpreted in the context of the potential limitations of our study. First, the cross-sectional, visit-based nature of the NHAMCS prohibits inferences of causality. The accuracy NHAMCS documentation has previously been debated [39, 40]. This analysis of a nationally representative sample of ED visits should therefore be considered hypothesis-generating. Second, NHAMCS data collection is based on ED provider documentation, does not record prehospital medication administration, and limits the number of diagnoses and injuries that can be recorded. For these reasons, the estimates presented likely represent an underestimate of the true incidence of naloxone administration and opioid-related ED utilization. Third, while we analyzed the most current NHAMCS data currently available to provide nationally representative estimates over a 12-year time period, our findings may not reflect current trends in this rapidly changing field. Next, given reliability criteria established by the NHAMCS, we were unable to provide estimates of important but uncommon outcomes such as overdose death. Finally, while NHAMCS data provide a set of common diagnostic tests and treatment modalities with which to describe national trends, we were not able to assess the appropriateness of providers’ decisions.

Naloxone is increasingly being seen as an important tool to prevent opioid overdose death, and its use in ED settings can provide valuable insights to guide broader implementation. There were more than two million opioid-related ED visits during the period studied, and these visits offer opportunities to both manage opioid-related complications and to prevent future complications. First, greater access to substance use disorder treatment directly from ED settings is needed, but the optimal model remains unclear [41, 42]. Second, opioid-related complications may be prevented with improved provider access to current, comprehensive patient data to guide decision-making around the risks of opioid pain medications. For example, amid growing support for prescription drug monitoring programs [43], these systems should consider tracking other indicators of opioid-related risk, such as opioid-related ED visits. Finally, each visit presents an opportunity to provide opioid safety education and to prescribe naloxone for take home use [15]. Research is needed to understand how to effectively frame and efficiently deliver this important content in busy clinical settings. Until then, our findings should serve as one more reason to identify and implement effective interventions to turn the tide on an epidemic of opioid-related harms.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

Dr. Frank was supported by the University of Colorado School of Medicine and the VA Eastern Colorado Health Care System. Dr. Levy was supported by the Denver-Seattle Center of Innovation for Veteran-Centered and Value Driven Care. Dr. Calcaterra was supported by the University of Colorado School of Medicine and by Denver Health Medical Center. Dr. Binswanger was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R34DA035952. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Paulozzi LJ, Jones CM, Mack KA, Rudd RA. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers - United States, 1999-2008: centers for disease control and prevention. 2011.

- 2.Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, Parrino MW, Severtson SG, Bucher-Bartelson B, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1406143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP. The changing face of heroin use in the United States: a retrospective analysis of the past 50 years. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(7):821–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones CM. Frequency of prescription pain reliever nonmedical use: 2002-2003 and 2009-2010. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(16):1265–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedegaard H, Chen L-H, Warner M. Rates of drug poisoning deaths involving heroin,* by selected age and racial/ethnic groups - United States, 2002 and 2011: centers for disease control and prevention; 2014.

- 7.Cai R, Crane E, Poneleit K, Paulozzi L. Emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of selected prescription drugs - United States, 2004-2008: centers for disease control and prevention. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Paulozzi L, Baldwin G, Franklin G, Kerlikowske RG, Jones CM, Ghiya N et al. CDC grand rounds: prescription drug overdoses - a U.S. Epidemic: centers for disease control and prevention. 2012.

- 9.Coben JH, Davis SM, Furbee PM, Sikora RD, Tillotson RD, Bossarte RM. Hospitalizations for poisoning by prescription opioids, sedatives, and tranquilizers. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyon S, Aks SE, Schaeffer S. Expanding access to naloxone in the United States. J Med Toxicol. 2014;10(4):431–4. doi: 10.1007/s13181-014-0432-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beletsky L, Rich JD, Walley AY. Prevention of fatal opioid overdose. JAMA. 2012;308(18):1863–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Injury Prevention & Control: Prescription Drug Overdose. Centers for disease control and prevention. 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/. Accessed October 7, 2015.

- 13.Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn E, Doe-Simkins M, Sorensen-Alawad A, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f174. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coffin PO, Sullivan SD. Cost-effectiveness of distributing naloxone to heroin users for lay overdose reversal. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(1):1–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Compton WM, Volkow ND, Throckmorton DC, Lurie P. Expanded access to opioid overdose intervention: research, practice, and policy needs. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(1):65–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-1-201301010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attorney General Holder Announces Plans for Federal Law Enforcement Personnel to Begin Carrying Naloxone. United States department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. 2014. www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2014/July/14-ag-805.html. Accessed October 7, 2015.

- 17.Petzel RA. Under secretary for Health's information letter: implementation of opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) to reduce risk of opioid-related death. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etherington J, Christenson J, Innes G, Grafstein E, Pennington S, Spinelli JJ, et al. Is early discharge safe after naloxone reversal of presumed opioid overdose? CJEM. 2000;2(3):156–62. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500004863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lidder S, Ovaska H, Archer JR, Greene SL, Jones AL, Dargan PI, et al. Doctors’ knowledge of the appropriate use and route of administration of antidotes in the management of recreational drug toxicity. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(12):820–3. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.054890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nissen LM, Wong KH, Jones A, Roberts DM. Availability of antidotes for the treatment of acute poisoning in Queensland public hospitals. Aust J Rural Health. 2010;18(2):78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2010.01129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thanacoody RH, Aldridge G, Laing W, Dargan PI, Nash S, Thompson JP, et al. National audit of antidote stocking in acute hospitals in the UK. Emerg Med J. 2013;30(5):393–6. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-201224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan JL, Marx JA, Calabro JJ, Gin-Shaw SL, Spiller JD, Spivey WL, et al. Double-blind, randomized study of nalmefene and naloxone in emergency department patients with suspected narcotic overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34(1):42–50. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(99)70270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barsan WG, Seger D, Danzl DF, Ling LJ, Bartlett R, Buncher R, et al. Duration of antagonistic effects of nalmefene and naloxone in opiate-induced sedation for emergency department procedures. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(2):155–61. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(89)90128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NCHS public-use data files and documentation: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS). National Center for Health Statistics. www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_questionnaires.htm. Accessed October 7, 2015.

- 25.Baca CT, Grant KJ. Take-home naloxone to reduce heroin death. Addiction. 2005;100(12):1823–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCaig LF, Burt CW. Understanding and interpreting the national hospital ambulatory medical care survey: key questions and answers. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(6):716–21. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin RJ, Reid MC, Chused AE, Evans AT. Quality assessment of acute inpatient pain management in an academic health center. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Ramachandran SK, Haider N, Saran KA, Mathis M, Kim J, Morris M, et al. Life-threatening critical respiratory events: a retrospective study of postoperative patients found unresponsive during analgesic therapy. J Clin Anesth. 2011;23(3):207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon DB, Pellino TA. Incidence and characteristics of naloxone use in postoperative pain management: a critical examination of naloxone use as a potential quality measure. Pain Manag Nurs. 2005;6(1):30–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosenfeld DM, Betcher JA, Shah RA, Chang YH, Cheng MR, Cubillo EI et al. Findings of a naloxone database and its utilization to improve safety and education in a tertiary care medical center. Pain Pract. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Lindstrom HA, Clemency BM, Snyder R, Consiglio JD, May PR, Moscati RM. Prehospital naloxone administration as a public health surveillance tool: a retrospective validation study. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2015;30(4):385–9. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X15004793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doe-Simkins M, Quinn E, Xuan Z, Sorensen-Alawad A, Hackman H, Ozonoff A, et al. Overdose rescues by trained and untrained participants and change in opioid use among substance-using participants in overdose education and naloxone distribution programs: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:297. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drug Abuse Warning Network . 2011: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hasegawa K, Espinola JA, Brown DF, Camargo CA., Jr Trends in US emergency department visits for opioid overdose, 1993-2010. Pain Med. 2014;15(10):1765–70. doi: 10.1111/pme.12461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, Adler JA, Ballantyne JC, Davies P, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10(2):113–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Interagency Guidelines on Opioid Dosing for Chronic Non-cancer Pain. Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group. 2010. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/files/opioidgdline.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2015.

- 37.Wheeler E, Davidson PJ, Jones TS, Irwin KS. Community-based opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone—United States, 2010: centers for disease control and prevention. 2012.

- 38.Binswanger IA, Koester S, Mueller SR, Gardner EM, Goddard K, Glanz JM. Overdose education and naloxone for patients prescribed opioids in primary care: a qualitative study of primary care staff. J Gen Intern Med. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Green SM. Congruence of disposition after emergency department intubation in the national hospital ambulatory medical care survey. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(4):423–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlson JN, Wang HE. The challenge of analyzing and interpreting NHAMCS. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(1):99–100. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bogenschutz MP, Donovan DM, Mandler RN, Perl HI, Forcehimes AA, Crandall C, et al. Brief intervention for patients with problematic drug use presenting in emergency departments: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1736–45. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Busch SH, Owens PH, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gugelmann HM, Perrone J. Can prescription drug monitoring programs help limit opioid abuse? JAMA. 2011;306(20):2258–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]