Abstract

Background

The phytohormone ethylene (ET) is a key signaling molecule for inducing the biosynthesis of shikonin and its derivatives, which are secondary metabolites in Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Although ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 (EIN3)/EIN3-like proteins (EILs) are crucial transcription factors in ET signal transduction pathway, the possible function of EIN3/EIL1 in shikonin biosynthesis remains unknown. In this study, by targeting LeEIL-1 (L. erythrorhizon EIN3-like protein gene 1) at the expression level, we revealed the positive regulatory effect of LeEIL-1 on shikonin formation.

Results

The mRNA level of LeEIL-1 was significantly up-regulated and down-regulated in the LeEIL-1-overexpressing hairy root lines and LeEIL-1-RNAi hairy root lines, respectively. Specifically, LeEIL-1 overexpression resulted in increased transcript levels of the downstream gene of ET signal transduction pathway (LeERF-1) and a subset of genes for shikonin formation, excretion and/or transportation (LePAL, LeC4H-2, Le4CL-1, HMGR, LePGT-1, LeDI-2, and LePS-2), which was consistent with the enhanced shikonin contents in the LeEIL-1-overexpressing hairy root lines. Conversely, LeEIL-1-RNAi dramatically repressed the expression of the above genes and significantly reduced shikonin production.

Conclusions

The results revealed that LeEIL-1 is a positive regulator of the biosynthesis of shikonin and its derivatives in L. erythrorhizon hairy roots. Our findings gave new insights into the molecular regulatory mechanism of ET in shikonin biosynthesis. LeEIL-1 could be a crucial target gene for the genetic engineering of shikonin biosynthesis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12870-016-0812-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ethylene, Hairy roots, LeEIL-1, Overexpression, RNAi, Shikonin

Background

The roots of medicinal plant Lithospermum erythrorhizon can specifically accumulate shikonin and its derivatives which have significant anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antimicrobial activities [1–4]. These red naphthoquinone pigments are also excellent natural dyes widely used in the industries of fabric, food and cosmetics [5, 6].

In the last decade, the cell or hairy root culture systems of L. erythrorhizon have been successfully used to produce these valuable compounds through a two-stage culture system, i.e., (1) L. erythrorhizon cells or hairy roots are cultured in B5 multiplication medium under light for fast amplification, and (2) transferred into M9 production medium to produce shikonin pigments in darkness [7–9]. This excellent system has become a promising tool to better understand the metabolism of shikonin pigments. Genes encoding pivotal enzymes or regulators for shikonin biosynthesis, excretion and/or transportation have also been cloned and characterized, such as the L. erythrorhizon phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene (LePAL) [10], the L. erythrorhizon cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase gene (LeC4H) [11], the 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase gene (HMGR) [12], the L. erythrorhizon p-hydroxybenzoate:geranyltransferase gene (LePGT) [13–15], the L. erythrorhizon pigment callus-specific gene (LePS-2) [16], and the L. erythrorhizon dark-inducible gene (LeDI-2) [17, 18]. Moreover, several factors, such as light [8, 19, 20], mineral elements [21, 22], fungal elicitor [23], culture medium [9], nitric oxide [24], methyl jasmonate [25], and ET [26], have been described to be crucial regulators of shikonin biosynthesis.

ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 (EIN3)/EIN3-like proteins (EILs) are plant-specific transcription factors which regulate various ET responses [27–29]. EIN3/EIL1 is a key integration node between ET and other signals in the complex molecular signaling network [30]. By binding to specific promoter elements, EIN3/EIL1 activates or represses the expression of target genes responsible for ET signaling, and thus modulates multiple ET-related responses of plants, such as those for development, phenotype, and adaptation to environmental stresses [31–33]. However, the knowledge of the relationship between EIN3/EIL and plant secondary metabolism remains limited.

In the medicinal plant L. erythrorhizon, ET is an important regulator of shikonin biosynthesis [26]. Furthermore, an optimal concentration of endogenous ET was presumed to be pivotal for shikonin formation [34]. LeEIL-1, a homolog of Arabidopsis EIN3, has been isolated from L. erythrorhizon cells. It was speculated to be important for ET-regulated shikonin biosynthesis [35]. However, the function of LeEIL-1 in shikonin biosynthesis at the molecular level remains unknown. Functional study on LeEIL-1 could be useful for elucidating the relationship among LeEIL-1, ET, and shikonin production.

In this study, two transgenic strategies, overexpression and RNA interference (RNAi), were applied to induce LeEIL-1-overexpression and LeEIL-1-RNAi transgenic hairy roots. The relationship between the expression pattern of LeEIL-1 and shikonin production was investigated to offer new insights into the understanding of the possible function of LeEIL-1 in shikonin biosynthesis.

Results

Hairy root induction, cultivation, and identification

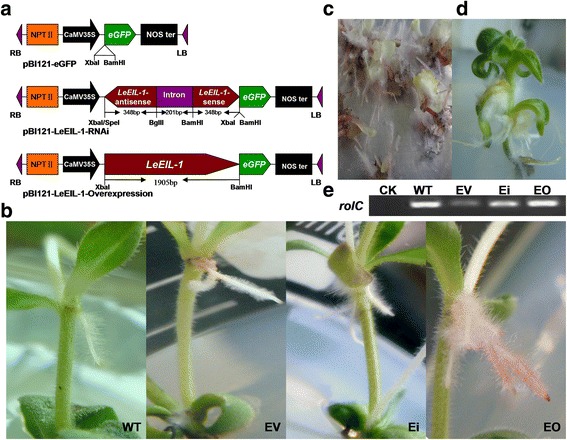

For more detailed understanding of the function of LeEIL-1 in shikonin formation, both RNAi and overexpression transgenic strategies were applied in this study. The plasmids of pBI121-LeEIL-1-Overexpression (EO) and pBI121-LeEIL-1-RNAi (Ei) were constructed and verified based on the pBI121-enhanced green fluorescent protein gene empty vector (pBI121-eGFP) (EV) (Fig. 1a; Additional file 1: Figure S1). The Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain 15834 (WT) and the A. rhizogenes 15834 containing EV, Ei or EO plasmid were employed to infect the nodes of aseptic seedlings [36]. Over 15 transgenic lines of hairy root had been successfully induced for each construct (i.e., EV, Ei, and EO) and WT (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Induction, verification, and growth polymorphism observation of four different types of hairy root lines. (a) Structure and restriction maps of the transformation vectors pBI121-eGFP (EV), pBI121-LeEIL-1-RNAi (Ei), and pBI121-LeEIL-1-Overexpression (EO); (b) Growth polymorphism of the induced L. erythrorhizon hairy roots by using the method of pricking nodes with a needle. Differentiated callus, leaf (c), and regenerated shoots (d) from the Ei hairy root lines on the stock culture medium; (e) PCR analysis of the rolC gene in hairy roots. The untransformed L. erythrorhizon seedling was used as the negative control (CK)

For stock culture, all hairy roots (WT, EV, Ei, and EO) were transferred into B5 solid medium (hormone-free and antibiotics-free) at 26–28 °C under subdued light. The remarkable growth polymorphisms of four types of hairy roots were observed at the infection sites (Fig. 1b) or in the stock culture medium (Additional file 2: Figure S2). EO hairy root lines were displayed obviously red either at the infection sites of seedling nodes or in sub-cultured stock medium under subdued light. No obvious red hairy root lines were observed in WT, Ei, and EV. Many black segments were observed in most Ei. The growth rates of EO and Ei were relative slow in comparison with those of WT and EV in the stock culture medium or multiplication culture medium, with Ei exhibiting the slowest growth rate (Additional file 3: Figure S3). This finding indicated that the growth of L. erythrorhizon hairy roots might be affected by excessively low or high expression level of LeEIL-1. We also found that callusing and regeneration phenomena easily occurred in the Ei cultured in B5 medium (Fig. 1c and d) compared with other hairy root lines. Hence, we speculated that the repressed mRNA level of LeEIL-1 changed the development and phenotype of hairy roots to some extent.

To confirm the transformation of hairy roots, the DNA samples from all transgenic hairy roots (WT, EV, Ei, and EO) were used as template for PCR amplification of the tagging rolC gene of A. rhizogenes 15834 [37, 38], and the DNA of untransformed L. erythrorhizon seedling was used as negative control. Results showed that the rolC gene was only amplified from WT, EV, Ei, and EO hairy roots, (Fig. 1e), which confirms the success of hairy root transformation of L. erythrorhizon.

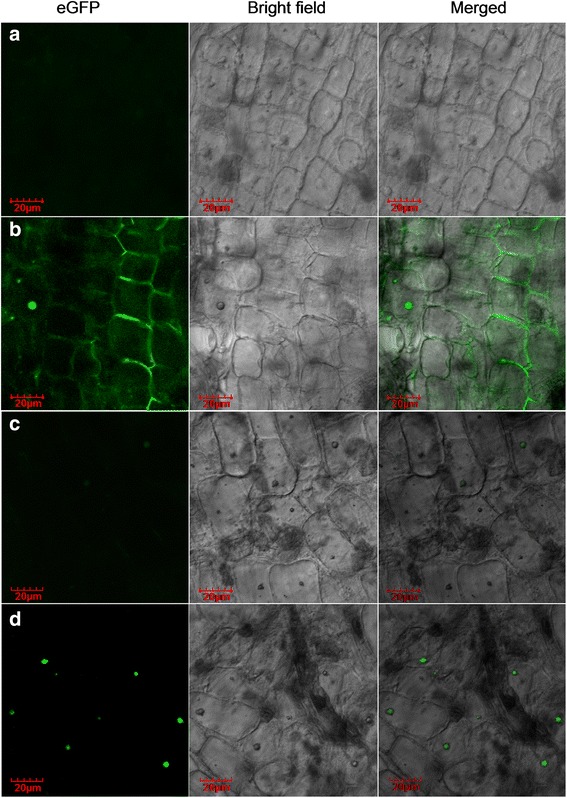

Confocal scanning laser microscopy analysis was performed on eGFP-tagged cells to identify all the hairy roots and clarify the subcellular localization of LeEIL-1. Different patterns of eGFP localization were visualized in hairy roots. No fluorescence could be observed in WT hairy roots (Fig. 2a), whereas uniform and intense signals of fluorescence appeared in the nucleus, cell wall and cytoplasm of EV hairy roots (Fig. 2b). In Ei hairy root lines, only weak fluorescence signal was discerned (Fig. 2c). In EO hairy root lines, strong signals emitted by eGFP were detected predominantly in the nucleus (Fig. 2d), where EIN3/EILs localized [39]. Based on these findings, we speculated that co-expression or co-localization of the fusion protein eGFP:LeEIL-1 may occur in the nucleus of EO but may be effectively suppressed in Ei hairy roots.

Fig. 2.

Confocal analyses of eGFP in WT (a), EV (b), Ei (c), and EO (d) hairy roots. Scale bar =20 μm; excitation wavelength = 488 nm; emission wavelength of eGFP = 510 nm

Expression patterns of LeEIL-1 in the two-stage culture system

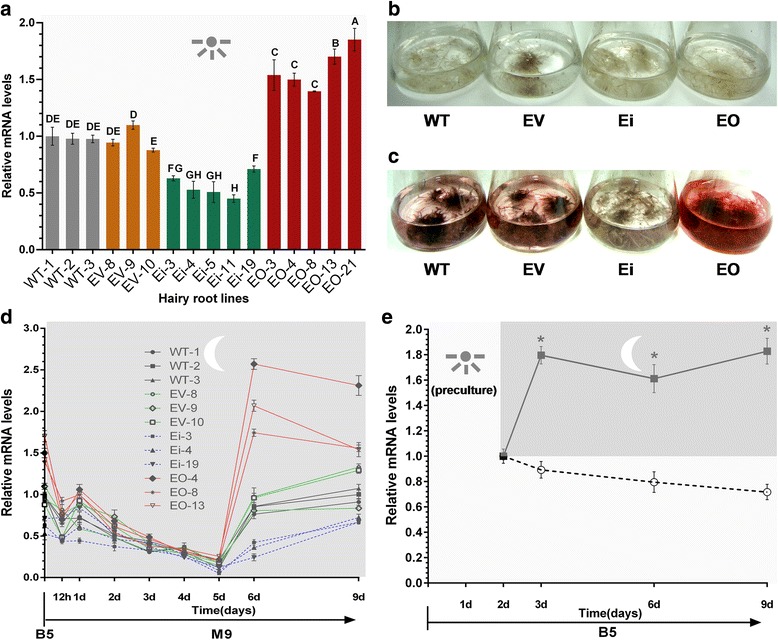

In order to assess the transgenic effects, expression patterns of LeEIL-1 in four types of hairy root were characterized by using real-time PCR method. Each five lines of Ei and EO cultured in B5 medium were randomly selected; each three lines of WT and EV were used as controls. Similar transcript levels were observed in three WT hairy root lines (WT-1, WT-2, and WT-3). Compared with that in WT hairy root lines, LeEIL-1 did not significantly change in EV hairy root lines (P > 0.05). However, in Ei hairy root lines, LeEIL-1 was significantly down-regulated compared with that in WT or EV (P < 0.01). In EO hairy root lines, LeEIL-1 significantly increased (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3a). Therefore, the transcript level of LeEIL-1 actually significantly increased in hairy roots of LeEIL-1-overexpressing and decreased in LeEIL-1-RNAi hairy root lines.

Fig. 3.

LeEIL-1 Expression patterns and visual inspection of WT, EV, Ei, and EO hairy root lines. (a) Transcript levels of LeEIL-1 in the randomly selected hairy root lines of WT, EV, Ei, and EO cultured in B5 medium under light at 26–28 °C for 15 days with constant shaking at 80 rpm. A representative example from two biological experiments was shown; data represent means ± SD (n = 3) and the bars with different capital letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.01 (Least Significant Difference); (b) Phenotypes of WT, EV, Ei, and EO hairy roots in conical flasks containing hormone-free B5 liquid medium for multiplication culture; (c) Visual inspection for the color changes of WT, EV, Ei, and EO hairy root lines in M9 for 6 days (20 ml medium/50 ml flask); (d) Dynamic expression pattern analysis of LeEIL-1 when hairy root lines were transferred from B5 into M9 medium. The values of Ei and EO lines are significantly different from those of WT or EV lines at the time points of 6 or 9 days, respectively (Least Significant Difference, P < 0.05); (e) Expression patterns of LeEIL-1 of the WT-1 during the dark/light transition, in which hairy roots were pre-cultured under light for 2 days and then transferred into darkness. The asterisk indicates that the mean value in the dark was significantly different from that under light at 3, 6 or 9 days time point, respectively (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05). The sunshine logo and light gray represent light period for B5 culture condition, and the moon logo and deep gray represent night period for M9 culture condition

We speculated that the transformation of LeEIL-1 genetically influences the biosynthesis of shikonin. Shikonin and its derivatives are red specific pigments, and color changes of the pigments in hairy roots as well as in M9 medium excreted from hairy roots were detected upon visual inspection [23]. Time-course analysis was also performed to assess shikonin pigment accumulation in hairy roots of WT, EV, Ei, and EO through visual inspection. No pigment was observed in B5 multiplication medium under light (Fig. 3b). The red color significantly changed when transferred hairy roots from B5 multiplication medium into M9 production medium for 1–6 days, reached the highest levels at 6–9 days, and exhibited minimal changes thereafter, with the highest yield found in EO and the lowest level in Ei from 1 to 9 days (Fig. 3c). The time course accumulation analyses of shikonin in different types of hairy roots were performed using the randomly selected four typical lines, i.e., WT-1, EV-9, Ei-19 and EO-13. From 1 to 6 days, the concentration of shikonin in hairy roots above increased rapidly, and then reached to a relative high level at the time point of 6 days. Thereafter, the content of shikonin in different hairy roots began to accumulate in different patterns. Significantly enhanced content of shikonin was observed in EO-13, while dramatically reduced in Ei-19 in comparison with that in EV-9 or WT-1 at each time point of 3, 6, 9 and 12 days (P < 0.05) (Additional file 4: Figure S4).

Based on the time-course analysis of shikonin formation, each three lines of WT, EV, Ei, and EO were selected and transferred from B5 multiplication medium into M9 production medium for the expression patterns analysis of LeEIL-1. Dynamic expression patterns of LeEIL-1 in the M9 production medium (12 h and 1–9 days) were detected, similar to the expression pattern of LeEIL-1 in L. erythrorhizon callus cells in our previous report [35]. Remarkable changes occurred when transferred hairy roots of WT, EV, Ei, and EO from B5 multiplication medium into M9 production medium for 9 days. The mRNA level of LeEIL-1 in each three lines of WT, EV, Ei, and EO reduced dramatically at 12 h, increased at 1 day in most hairy root lines, constantly declined, and then reached the lowest level at 5 days.

The transcript levels of LeEIL-1 significantly exhibited varied increase rates in each type of hairy roots cultured in M9 from 5 to 9 days (Fig. 3d). In hairy roots of WT, EV, and Ei, the LeEIL-1 transcripts presented a rapid increase from 5 to 6 days, and then continually increased for 6–9 days. The LeEIL-1 transcript level in EO hairy root lines, however, slightly reduced from 6 to 9 days and maintained a relatively high level compared with those in WT, EV, and Ei hairy root lines at 9 days. Consistent with the visual inspection results on shikonin production in M9 medium, the highest LeEIL-1 transcript level was found in EO lines, the lowest level in Ei lines, and the medium level in EV or WT lines from 5 to 9 days (Fig. 3d). It is obviously, the sixth day in the M9 medium is the important time point at which the expression level of LeEIL-1 in different hairy roots should be compared. This result indicated that LeEIL-1 expression might be concurrent with the accumulation of shikonin and its derivatives.

Interestingly, we noticed that LeEIL-1 was down-regulated at the early stage within 5 days no matter it was located downstream of CaMV-35s promoter or not. In the two-stage culture system, the antibiotic- and hormone-free B5 medium was used as the growth medium for multiplying hairy roots under constant light condition, whereas the hormone-containing M9 medium was employed for hairy roots to produce shikonin and its derivatives under continuous dark culture condition. We speculated that the dramatic differences (medium components and culture condition) between these two stages might affect the expression of LeEIL-1 at the early stage when transferred L. erythrorhizon hairy roots from B5 multiplication medium into M9 production medium.

Since shikonin is biosynthesized in the dark, we also detected the effect of light signal on the expression pattern of LeEIL-1. The WT-1 hairy root line was randomly selected and pre-cultured in B5 for 2 days under constant light condition. Similar to the expression pattern of LeERF-1, which is another ET response factor reported in our previous study [40], LeEIL-1 was induced by dark (Fig. 3e). This result was also consistent with the dark-induced mRNA levels of EIN3 in Arabidopsis [41].

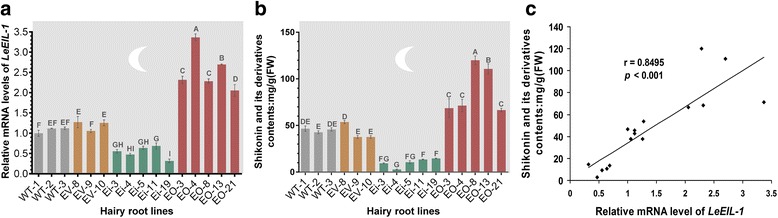

LeEIL-1 is a positive regulator of shikonin production

Based on the above results, we speculated that LeEIL-1 positively mediates ET-regulated shikonin biosynthesis. To validate the speculation, we performed the relationship analysis between the expression level of LeEIL-1 (Fig. 4a) and the shikonin contents (Fig. 4b) in various hairy roots in M9 production medium for 6 days. In addition, as for different hairy root types (WT, EV, Ei and EO), only the expression levels of LeEIL-1 affected by RNAi or overexpresison were different; all other factors, including M9 medium, culture condition (in darkness at 26 °C), were same for them in the research system.

Fig. 4.

LeEIL-1expression levels (a) and shikonin production (b) of the randomly selected hairy root lines. WT, EV, Ei, and EO hairy root lines cultured in M9 production medium for 6 days. The values are means ± SD (n = 3), and the bars with different capital letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.01 (Least Significant Difference). The deep gray and moon logo indicate the hairy roots were cultured in the dark. Scatter diagram showing the significantly positive linear relationship between LeEIL-1 expression level and shikonin production (r = 0.8495; P < 0.001) (c)

The results showed that both the LeEIL-1 expression levels and shikonin production were significantly increased in EO hairy root lines, but dramatically declined in Ei in comparison with those in WT or EV control lines (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4a and b). Thus, a significantly positive linear correlation between shikonin content and LeEIL-1 expression level was deduced based on the results of all lines detected above (r = 0.8495; P < 0.001) (Fig. 4c). Furthermore, a number of high-yield shikonin hairy roots had been obtained from EO (Additional file 5: Figure S5), suggesting the strategy of LeEIL-1-overexpression has great potential to obtain hairy roots with high-yield shikonin production.

LeEIL-1 confers shikonin production by regulating the expression of key genes for shikonin biosynthesis

As EIN3/EILs act as key positive regulators at the most downstream of ET signaling transduction pathway [39, 42], we deduced that the expression of LeEIL-1 is possibly associated with the downstream target genes which regulate shikonin formation. Further research on genes involved in ET signaling transduction pathway and shikonin biosynthesis pathway under the mechanism of overexpression and RNAi of LeEIL-1 will bridge the gap between shikonin production and accumulation of LeEIL-1 transcripts.

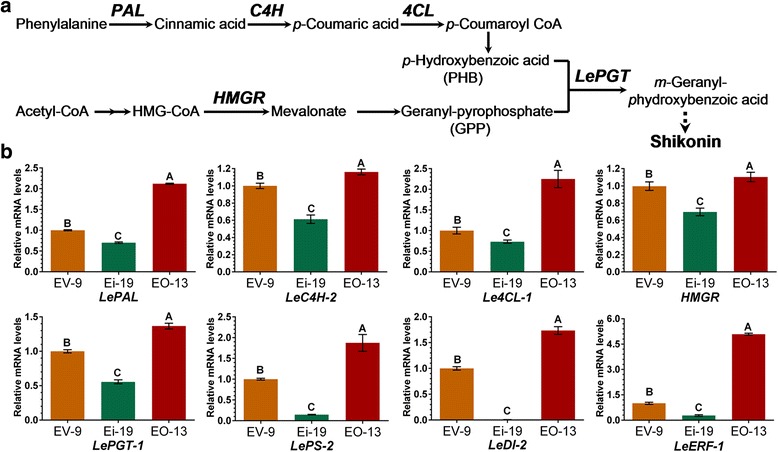

Since there was no difference for shikonin production and expression level of LeEIL-1 between EV and WT, and to avoid the transgenic effects of plasmid, three pBI121 vector containing lines (i.e., EV-9, Ei-19, and EO-13) cultured in M9 for 6 days were selected for further analyses of the expression of several key genes implicated in shikonin biosynthesis. These genes include the speculated downstream gene of LeEIL-1 (LeERF-1), the key genes involved in biosynthetic pathway of shikonin (LePAL, LeC4H-2, Le4CL-1, HMGR, LePGT-1) (Fig. 5a), and the genes possibly responsible for the transportation, stabilization and/or excretion of shikonin pigments (LeDI-2 and LePS-2).

Fig. 5.

Expression patterns of shikonin biosynthesis-related genes regulated by LeEIL-1. (a) The metabolic pathway outline for the biosynthesis of shikonin and its derivatives. The genes encoding crucial enzymes of this pathway are marked in bold and italic fonts; (b) Transcript levels of the key shikonin biosynthesis-related gene in EV, Ei, and EO hairy root lines cultured in M9 medium for 6 days. A representative example from two biological experiments is shown; the values are means ± SD (n = 3) and the bars with different capital letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.01 (Least Significant Difference)

The expression level of LeERF-1 was significantly up-regulated in EO-13 but down-regulated in Ei-19 compared with that in the EV-9 control (P < 0.01). Similarly, LeEIL-1 overexpression significantly up-regulated the mRNA accumulation of LePAL, LePGT-1, LeC4H-2, LePS-2, Le4CL-1, LeDI-2 and HMGR in EO hairy root line (P < 0.01). By contrast, RNAi-mediated knockdown of LeEIL-1 in Ei hairy roots significantly suppressed the expression of all genes, especially LeDI-2 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5b). We speculated that the up- or down-regulated transcripts of LeEIL-1 in turn altered the transcription of most genes in the biosynthetic pathway of shikonin. In the hairy roots cultured in M9, expression patterns of these shikonin biosynthesis-related genes (LePAL, LePGT-1, LeC4H-2, LePS-2, Le4CL-1, LeDI-2 and HMGR) matched to the expression pattern of LeEIL-1, as well as shikonin production at the time point of 6 days (Fig. 4a and b). This observation indicated that these shikonin biosynthesis-related genes were induced by LeEIL-1 and might be involved in the LeEIL-1-regulated shikonin production.

LeDI-2 gene does not participate in the biosynthesis of shikonin, however, it possibly functions in the stabilization and/or transport of shikonin [8, 17]. LePS-2 is possibly a key gene functioning in the trapping and/or intra-cell wall excretion of shikonin pigments [16]. These studies collectively indicated that the regulation of LeEIL-1 in shikonin accumulation possibly also includes the event of excretion, stabilization, and/or transportation of shikonin and its derivatives after biosynthesis. Hence, a certain cooperative relationship is necessary between LeEIL-1 and genes participating in shikonin biosynthesis in L. erythrorhizon.

Taken together, LeEIL-1 confers shikonin production through the regulation of key genes participating in shikonin biosynthesis.

Discussion

LeEIL-1 is a pivotal target gene contributing to efficient shikonin formation

In the signaling network of plant, EIN3/EIL1 acts as a key integration node between ET and other signals [30]. EIN3/EIL1 activates the expression of downstream genes, in which ERFs are the typical ones [39, 43]. ERFs then bind to the GCC box cis-elements of many genes regulated by ET, and function positively by activating ET responses [44].

In the medicinal plant L. erythrorhizon, shikonin and its derivatives are specifically accumulated in the dark but are suppressed under white or blue light condition. Consistent with the mRNA level of dark-inducible genes LeERF-1 [40] and LeDI-2 [17], LeEIL-1 was also up-regulated in the dark. This finding indicated that light signal acts as a pivotal regulator of LeEIL-1 during the process of shikonin biosynthesis.

As the first precursor for shikonin biosynthesis, p-hydroxybenzoic acid (PHB) is synthesized in the phenylpropanoid pathway. PHB is regulated by sequential enzymes, namely, PAL, C4H, and 4CL [10, 45]. The other precursor is geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), which is synthesized in the isoprenoid pathway catalyzed by HMGR [12]. The formation of m-geranyl-phydroxybenzoic acid (GBA) is the pivotal step of shikonin formation. In this process, the substrates PHB and GPP were catalyzed by LePGT to form GBA, thereby synthesizing shikonin pigmens in L. erythrorhizon [15, 46] (Fig. 5a). In this study, LeEIL-1 overexpression enhanced the expression of the downstream gene of LeEIL-1 (LeERF-1) and a subset of key genes related to shikonin biosynthesis, excretion and/or transportation and stabilization (i.e., LePAL, LePGT-1, LeC4H-2, LePS-2, Le4CL-1, LeDI-2 and HMGR) (Fig. 5b), and thus increased shikonin accumulation. Conversely, RNAi of LeEIL-1 effectively decreased shikonin accumulation and down-regulated the above genes. Herein, we speculate that both the isoprenoid pathway and the phenylpropanoid pathway for shikonin biosynthesis were regulated by LeEIL-1, but further direct evidences should be provided in future studies. Moreover, the regulatory process also includes the transportation and/or excretion and stabilization of shikonin and its derivatives after formation. In a word, LeEIL-1 is one of the most important contributors possibly in the ET-regulated shikonin biosynthesis in L. erythrorhizon.

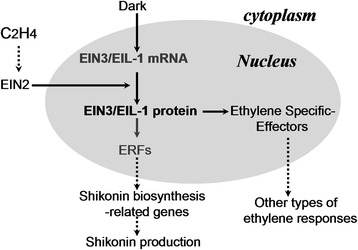

Although the up-regulated transcripts of some EIN3/EIL members contribute to constitutive ET responses, exogenous ET can not affect the EIN3/EIL mRNA levels [47, 48]; nevertheless, the abundance of the EIN3/EIL protein considerably increased upon ET exposure because of the strong stabilization of this protein [42]. The accumulation of EIN3/EIL protein is primarily regulated at post-transcriptional level in vivo, and EIN2 is essential in regulating ET-induced EIN3/EIL1 [49, 50]. Based on the results of previous and present studies, we propose a model for describing the LeEIL-1-regulated shikonin production possibly in the ET signaling cascade (Fig. 6); in this model, which is similar to that described by Li et al. (2013), dark-induced LeEIL-1 acts as a positive regulator in ET-regulated shikonin formation. Therefore, hairy roots with high-yield of shikonin could be obtained by using the LeEIL-1-overexpression strategy (Additional file 5: Figure. S5).

Fig. 6.

A proposed model illustrates the function of EIN3/EIL-1 in regulating shikonin production. The dotted lines represent regulatory steps, in which a direct physical link between upstream and downstream components has yet to be demonstrated

LeEIL-1 is a possible integration node between ET and other signal molecules

In Arabidopsis, EIN3 and its close homolog EIL1 regulate myriad ET responses [39, 47]. In the life cycle of plant, EIN3/EIL1 acts as a regulator of ET signaling as well as myriad processes, such as the development and stress responses [29, 32], plant immunity defenses [28], and crosstalk between ET and jasmonate [30]. Moreover, EIN3/EIL1 is also involved in plant morphological phenotype changes [43], the de-etiolation of seedlings, and leaf senescence [41, 51].

In this study, the polymorphism and growth rate of hairy roots changed under the condition of either LeEIL-1-overexpression or LeEIL-1-RNAi (Fig. 1b; Additional file 2: Figure. S2). Meanwhile, callusing, differentiation and regeneration phenomena easily occurred in Ei hairy root lines cultured in B5 solid or liquid medium (Fig. 1c and d), compared with that in other hairy root lines cultured under the same condition. Thus, we speculate that LeEIL-1 possibly regulates other inputs or ET specific effectors in multiple layers in the ET signaling cascade, thereby inducing the cascade of ET responses for cell development, differentiation, and regeneration. It will thus be interesting to investigate whether LeEIL-1 acts as one of the convergence points between ET and other signal molecules in the complex network of ET transduction pathway in L. erythrorhizon.

Conclusions

Although the biosynthetic pathway of shikonin and its derivatives has been basically well-characterized, the molecular mechanism and key target regulators of shikonin formation are largely unknown. In the present study, by using an excellent two-stage hairy root culture system as the basal condition for shikonin production, we provided evidences for the positive role of LeEIL-1 in regulating shikonin formation. In hairy root lines of EO, LeEIL-1-overexpressing significantly enhanced shikonin content in comparison with that in Ei, as well as the control lines of WT or EV under the same culture conditions. Our findings paved the way for future work aiming at extending our knowledge of the molecular regulatory mechanism of ET in shikonin biosynthesis. Furthermore, we offered a key target gene which has great potential for efficient shikonin biosynthesis in genetic engineering of L. erythrorhizon. Future studies focusing on the direct function of LeEIL-1 or other LeEILs in the ET signaling transduction pathway in L. erythrorhizon will give more evidences for the regulation of ethylene on shikonin biosynthesis.

Methods

Plant materials and treatment

The seeds of L. erythrorhizon Sieb. et Zucc were collected in the field location of Ulanhot city, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China (N46°04′13.55″, E122°07′42.15″) in accordance with local legislation, and no specific permission was required for this study. Seed stratification and sterilization, as well as the seedling culture condition were essentially as we previously reported [52]. The robust seedlings were used for hairy root induction.

Plasmid construction and transformation

The plasmid of LeEIL-1-overexpression or LeEIL-1-RNAi was constructed based on the plant expression vector pBI121-eGFP. XbaI/BamHI were selected for the digestion of pBI121-eGFP vector, the coding region of LeEIL-1 (1905 bp) was cloned and introduced into the cleavage site, with the cDNA expression cassette between the CaMV35s promoter and the eGFP, thereby generated the plasmid of pBI121-LeEIL-1-Overexpression [52].

To construct the pBI121-LeEIL-1-RNAi plasmid, a strategy similar to the previous reports was adopted [52–54]. The intron-containing intermediate vector pUCCRNAi was used [55]. A sequence of LeEIL-1 (348 bases) was selected based on the bioinformatics analyses of LeEIL-1. The sense sequence was cloned and inserted into pUCCRNAi in positive orientation, thereby generated a vector of pUCCRNAi-intron-F. The anti-sense sequence was also amplified and inserted into pUCCRNAi-intron-F in reverse orientation. This process generated plasmid of pUCCRNAi-R-intron-F. To obtain the target inverted repeat sequence, the SpeI/XbaI were selected for the digestion of pUCCRNAi-R-intron-F plasmid. Finally, the sequences obtained were inserted in the pBI121-eGFP vector, thereby generated the plasmid of pBI121-LeEIL-1-RNAi [52, 56].

All plasmids (pBI121-LeEIL-1-RNAi, pBI121-LeEIL-1-Overexpression and pBI121-eGFP) were transformed into the Escherichia coli strain TOP10 for amplification and PCR verification. Finally, these recombined expression plasmids were introduced into A. rhizogenes strain ATCC15834 as previously reported [52, 57, 58]. All primers for the construction of plasmids and verification of ATCC15834 carrying vectors are listed in Additional file 6: Table S1.

Induction and cultivation of hairy roots

The hairy root system was used for shikonin biosynthesis and expression analysis of LeEIL-1 via the two-stage culture system [8, 9]. The infection strains used for hairy root induction were as follows: A. rhizogenes strain 15834 (WT), and A. rhizogenes 15834 strain carrying the plasmid pBI121-eGFP (EV), pBI121-LeEIL-1-Overexpression (EO) or pBI121-LeEIL-1-RNAi (Ei). All stains were inoculated in YEB liquid medium in a rotary shaker (120 rpm, 26–28 °C) for about 36 h. Kanamycin (50 mg l−1) was added to the YEB medium for antibiotic resistance screening of EV, Ei and EO. When the OD600 of infection strains reached 0.5, acetosyringone (AS) at 100 μM was supplemented.

Hairy roots were then induced with the method as we previously reported [36, 52]. In brief, seedling nodes were pricked with a needle soaked in the infection medium. Then the vaccinated seedlings were transplanted to MS solid medium under subdued light or dark condition till the hairy roots appeared after 2 weeks, and over 15 lines for each type of hairy root were generated. At the infection sites, individual hairy root of about 1 cm was excised. After the elimination of residual Agrobacterium with cefotaxime, hairy roots were cultured in B5 solid medium (antibiotic- and hormone-free). The conditions of stock cultivation were set as follow: under subdued light at 26–28 °C.

The two-stage culture system was adopted for hairy root cultivation as previously described [7–9, 21]. Hairy roots cultured on B5 solid medium were cut, and then transferred into B5 multiplication liquid medium (antibiotic- and hormone-free) for fast amplification under continuous white light at 26–28 °C with a constant shaking rate of 80 rpm. Hairy roots were subcultured every 15 days (Fig. 3b).

For shikonin biosynthesis, hairy roots were transferred from B5 multiplication medium into M9 production medium and cultured in the dark at 26–28 °C with a constant shaking rate of 80 rpm [21, 36, 52, 59] (Fig. 3c).

Subcellular localization analysis of LeEIL-1

The confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscope (LSFM, FV10-ASW, Olympus, Japan) was used for the detection of eGFP fluorescence. Excitation and emission wavelength were 488 and 510 nm, respectively [39, 60].

Real-time PCR analysis

Hairy root lines cultured in B5 multiplication medium or in M9 production medium were selected for mRNA level analysis. TRIzol reagent (TaKaRa Biotech, Shiga, Japan) was used to extract total RNA from hairy roots. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by using 1 μg of the total RNA and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The real-time PCR was performed by using CFX96TM (Bio-Rad, USA) and the SYBR Green real-time PCR Master Mix (Toybo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Primers for real-time PCR analysis were designed based on the sequences in the GenBank database [24] (Additional file 7: Table S2). The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (GAPDH), an internal reference gene, was selected as in our previous reports [24, 36, 52]. The thermal program was performed using the following parameters: denatured at 95 °C for 1 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles (95 °C for 15 s, 55 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 45 s). Melting curves were performed after 40 cycles to confirm the specificity of the reactions. Relative expression level was calculated using the ΔΔCt method [24, 35, 36, 40, 52]. At least two to three biological replicates and three technical replicates were performed for the data analysis.

Measurement of shikonin contents

Measurement of shikonin contents was conducted as we previously reported [19, 20, 24, 36, 52]. In brief, shikonin and its derivatives were extracted with petrol ether and measured by using the WFZ UV-2800H spectrophotometer (Unico, Shanghai, China). Absorption of these pigments was detected at the characteristic wavelength of 520 nm. Shikonin contents were determined using a standard curve as we previously reported (shikonin content = 41.66 × OD520 × dilution fold) [19, 20, 24, 52]. The total shikonin content including the pigments extracted from both the hairy roots and the M9 production medium was expressed as mg/g fresh weight (FW) of hairy root.

Abbreviations

ET, ethylene; eGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; EO, pBI121-LeEIL-1-Overexpression; EIN3/EIL, Ethylene-insensitive 3/EIN3-like protein; Ei, pBI121-LeEIL-1-RNAi; EV, pBI121-eGFP Empty Vector; LeEIL-1, L. erythrorhizon EIN3-like protein gene 1; LePAL, L. erythrorhizon phenylalanine ammonia-lyase gene; LeC4H-2, L. erythrorhizon cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase gene 2; Le4CL-1, L. erythrorhizon 4-coumaric acid:CoA ligase gene 1; HMGR, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase gene; LePGT-1, L. erythrorhizon p–hydroxybenzoate:geranyltransferase gene 1; LePS-2, (L. erythrorhizon pigment callus-specific gene 2); LeDI-2, L. erythrorhizon dark-inducible gene 2; LeERF-1, L. erythrorhizon ethylene response factor gene 1; RNAi, RNA interference; WT, wild type.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (31170275, 31071082, 31171161, and 31470384), the Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT_14R27), the Project of New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-11-0234), and the fund for University Ph.D. Program from the Ministry of Education of China (20120091110037).

Availability of data and materials

All supporting data can be found within the manuscript and its additional files.

Authors’ contributions

JQ, GL, and YY designed research; RF, AZ, HZ, FW, YZ, HZ, and YL performed research; RF, R-JT, YP, RY, XW, JQ, GL, and YY analyzed data; RF, JQ, GL, and YY wrote the paper. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional files

Verification of the constructed recombinant vectors. (A) Identification of the eGFP gene in the pBI121-eGFP vector by using the primer pair eGFP-F/R; (B) Amplification of the inserted target sequence in the pBI121-LeEIL-1-RNAi vector by using the primer pair 35S-F/GFP-R. (C) Amplification of the inserted target sequence of LeEIL-1 in the pBI121-LeEIL-1-Overexpression vector by using the primer pair 35S-F/GFP-R. Primer sets are listed in Additional file 6: Table S1. (TIF 456 kb)

Stock culture of WT (A), EV (B), Ei (C) and EO (D) hairy roots of L. erythrorhizon on B5 solid medium (antibiotics-free and hormone-free). (TIF 3277 kb)

The time course of fresh weight (FW) of WT-1, EV-9, Ei-19 and EO-13 cultured in B5 multiplication medium (continuous light at 26–28 °C with a constant shaking rate of 80 rpm). The inoculum size of 0.2 g hairy roots was subcultured in 20 ml medium/50 ml flask. Three biological replicates were performed; the value of Ei-19 or EO-13 is significantly different from that control line of WT-1 or EV-9 at each time point from 3 to 15 days, respectively (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05). (TIF 83 kb)

Time-course accumulation of shikonin in four typical hairy root lines. Value of Ei-19 or EO-13 is significantly different from that of the control line WT-1 or EV-9 at each time point from 3 to 12 days, respectively (Student’s t-test, P < 0.05). (TIF 125 kb)

Comparison of growth characteristics between the typical low-yield shikonin line (A) of Ei and high-yield shikonin line (B) of EO. Hairy roots were cultured in M9 production medium in the dark for 6 days (20 ml medium/50 ml flask). (TIF 3133 kb)

Primers for LeEIL-1 cDNA cloning and vector construction and verification. (DOC 39 kb)

Real-time PCR primers for gene expression analysis. (DOC 34 kb)

Contributor Information

Jinliang Qi, Phone: +86-25-89686305, Email: qijl@nju.edu.cn.

Guihua Lu, Email: guihua.lu@nju.edu.cn.

Yonghua Yang, Phone: +86-25-89686305, Email: yangyh@nju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Chen X, Yang L, Zhang N, Turpin JA, Buckheit RW, Osterling C, et al. Shikonin, a component of Chinese herbal medicine, inhibits chemokine receptor function and suppresses human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2810–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2810-2816.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Qian R-Q, Li P-P. Shikonin, an ingredient of Lithospermum erythrorhizon, down-regulates the expression of steroid sulfatase genes in breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;284:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Xie J, Jiang Z, Wang B, Wang Y, Hu X. Shikonin and its analogs inhibit cancer cell glycolysis by targeting tumor pyruvate kinase-M2. Oncogene. 2011;30:4297–306. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, Liu T, Gan L, Wang T, Yuan X, Zhang B, et al. Shikonin protects mouse brain against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through its antioxidant activity. Europ J Pharmacol. 2010;643:211–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Papageorgiou V. Naturally occurring isohexenylnaphthazarin pigments: a new class of drugs. Planta Med. 1980;38:193–203. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1074864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papageorgiou VP, Assimopoulou AN, Couladouros EA, Hepworth D, Nicolaou K. The chemistry and biology of alkannin, shikonin, and related naphthazarin natural products. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1999;38:270–301. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990201)38:3<270::AID-ANIE270>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimomura K, Sudo H, Saga H, Kamada H. Shikonin production and secretion by hairy root cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Rep. 1991;10:282–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00193142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yazaki K, Matsuoka H, Ujihara T, SATO F. Shikonin biosynthesis in Lithospermum erythrorhizon:Light-induced negative regulation of secondary metabolism. Plant Biotechnol. 1999;16:335–42. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.16.335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Touno K, Harada K, Yoshimatsu K, Yazaki K, Shimomura K. Shikonin derivative formation on the stem of cultured shoots in Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Rep. 2000;19:1121–6. doi: 10.1007/s002990000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yazaki K, Kataoka M, Honda G, Severin K, Heide L. cDNA cloning and gene expression of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase in Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1997;61:1995–2003. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamamura Y, Ogihara Y, Mizukami H. Cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase from Lithospermum erythrorhizon: cDNA cloning and gene expression. Plant Cell Rep. 2001;20:655–62. doi: 10.1007/s002990100373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lange BM, Severin K, Bechthold A, Heide L. Regulatory role of microsomal 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase for shikonin biosynthesis in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell suspension cultures. Planta. 1998;204:234–41. doi: 10.1007/s004250050252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yazaki K, Kunihisa M, Fujisaki T, Sato F. Geranyl Diphosphate: 4-Hydroxybenzoate Geranyltransferase from Lithospermum erythrorhizon CLONING AND CHARACTERIZATION OF A KEY ENZYME IN SHIKONIN BIOSYNTHESIS. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6240–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106387200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohara K, Muroya A, Fukushima N, Yazaki K. Functional characterization of LePGT1, a membrane-bound prenyltransferase involved in the geranylation of p-hydroxybenzoic acid. Biochem J. 2009;421:231–41. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohara K, Mito K, Yazaki K. Homogeneous purification and characterization of LePGT1- a membrane-bound aromatic substrate prenyltransferase involved in secondary metabolism of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. FEBS J. 2013;280:2572–80. doi: 10.1111/febs.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamura Y, Sahin FP, Nagatsu A, Mizukami H. Molecular cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel apoplastic protein preferentially expressed in a shikonin-producing callus strain of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:437–46. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcg057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yazaki K, Matsuoka H, Sato F. cDNA cloning and functional analysis of LEDI-2, a gene preferentially expressed in the dark in Lithospermum cell suspension cultures. Plant Physiol. 1997;114:1348. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Touno K, Harada K, Yoshimatsu K, Yazaki K, Shimomura K. Histological observation of red pigment formed on shoot stem of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Biotech. 2000;17:127–30. doi: 10.5511/plantbiotechnology.17.127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, Qi J-L, Chen L, Zhang M-S, Wang X-Q, Pang Y-J, et al. Effect of light on gene expression and shikonin formation in cultured Onosma paniculatum cells. Plant Cell Tiss Org Cult. 2006;84:38–48. doi: 10.1007/s11240-005-8120-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W-J, Su J, Tan M-Y, Liu G-L, Pang Y-J, Shen H-G, et al. Expression analysis of shikonin-biosynthetic genes in response to M9 medium and light in Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell cultures. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult. 2010;101:135–42. doi: 10.1007/s11240-010-9670-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujita Y, Hara Y, Suga C, Morimoto T. Production of shikonin derivatives by cell suspension cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Rep. 1981;1:61–3. doi: 10.1007/BF00269273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Z, Li Y, Yang T, Su J, Zhang M, Tian R, et al. Shikonin accumulation is related to calcium homeostasis in Onosma paniculata cell cultures. Phyton-Ann Rei Bot. 2011;51:103–13. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brigham LA, Michaels PJ, Flores HE. Cell-specific production and antimicrobial activity of naphthoquinones in roots of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Physiol. 1999;119:417–28. doi: 10.1104/pp.119.2.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu S-J, Qi J-L, Zhang W-J, Liu S-H, Xiao F-H, Zhang M-S, et al. Nitric oxide regulates shikonin formation in suspension-cultured Onosma paniculatum cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009;50:118–28. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yazaki K, Takeda K, Tabata M. Effects of methyl jasmonate on shikonin and dihydroechinofuran production in Lithospermum cell cultures. Plant Cell Physiol. 1997;38:776–82. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Touno K, Tamaoka J, Ohashi Y, Shimomura K. Ethylene induced shikonin biosynthesis in shoot culture of Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2005;43:101–5. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Potuschak T, Lechner E, Parmentier Y, Yanagisawa S, Grava S, Koncz C, et al. EIN3-dependent regulation of plant ethylene hormone signaling by two Arabidopsis F box proteins: EBF1 and EBF2. Cell. 2003;115:679–89. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00968-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Xue L, Chintamanani S, Germain H, Lin H, Cui H, et al. ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3-LIKE1 repress SALICYLIC ACID INDUCTION DEFICIENT2 expression to negatively regulate plant innate immunity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2527–40. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.065193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng J, Li Z, Wen X, Li W, Shi H, Yang L, et al. Salt-induced stabilization of EIN3/EIL1 confers salinity tolerance by deterring ROS accumulation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu Z, An F, Feng Y, Li P, Xue L, Mu A, et al. Derepression of ethylene-stabilized transcription factors (EIN3/EIL1) mediates jasmonate and ethylene signaling synergy in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:12539–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103959108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boutrot F, Segonzac C, Chang KN, Qiao H, Ecker JR, Zipfel C, et al. Direct transcriptional control of the Arabidopsis immune receptor FLS2 by the ethylene-dependent transcription factors EIN3 and EIL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14502–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003347107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi Y, Tian S, Hou L, Huang X, Zhang X, Guo H, et al. Ethylene signaling negatively regulates freezing tolerance by repressing expression of CBF and type-A ARR genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2578–95. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang J, Clay JM, Chang C. Association of cytochrome b5 with ETR1 ethylene receptor signaling through RTE1 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2014;77:558–67. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qi JL, Zhang WJ, Liu SH, Wang H, Sun DY, Xu GH, et al. Expression analysis of light-regulated genes isolated from a full-length-enriched cDNA library of Onosma paniculatum cell cultures. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165:1474–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou A, Zhang W, Pan Q, Zhu S, Yin J, Tian R, et al. Cloning, characterization, and expression of LeEIL-1, an Arabidopsis EIN3 homolog, in Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Cell Tiss Org Cult. 2011;106:71–9. doi: 10.1007/s11240-010-9895-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao H, Chang Q, Zhang D, Fang R, Wu F, Wang X, et al. Overexpression of LeMYB1 enhances shikonin formation by up-regulating key shikonin biosynthesis-related genes in Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Biol Plant. 2015;59:429–35. doi: 10.1007/s10535-015-0512-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batra J, Dutta A, Singh D, Kumar S, Sen J. Growth and terpenoid indole alkaloid production in Catharanthus roseus hairy root clones in relation to left-and right-termini-linked Ri T-DNA gene integration. Plant Cell Rep. 2004;23:148–54. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grąbkowska R, Królicka A, Mielicki W, Wielanek M, Wysokińska H. Genetic transformation of Harpagophytum procumbens by Agrobacterium rhizogenes: iridoid and phenylethanoid glycoside accumulation in hairy root cultures. Acta Physiol Plant. 2010;32:665–73. doi: 10.1007/s11738-009-0445-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An F, Zhao Q, Ji Y, Li W, Jiang Z, Yu X, et al. Ethylene-induced stabilization of ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE3 and EIN3-LIKE1 is mediated by proteasomal degradation of EIN3 binding F-box 1 and 2 that requires EIN2 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2384–401. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.076588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang W, Zou A, Miao J, Yin Y, Tian R, Pang Y, et al. LeERF-1, a novel AP2/ERF family gene within the B3 subcluster, is down-regulated by light signals in Lithospermum erythrorhizon. Plant Biol. 2011;13:343–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2010.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Z, Peng J, Wen X, Guo H. Ethylene-insensitive3 is a senescence-associated gene that accelerates age-dependent leaf senescence by directly repressing miR164 transcription in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3311–28. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.113340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo H, Ecker JR. Plant responses to ethylene gas are mediated by SCFEBF1/EBF2-dependent proteolysis of EIN3 transcription factor. Cell. 2003;115:667–77. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00969-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solano R, Stepanova A, Chao Q, Ecker JR. Nuclear events in ethylene signaling: a transcriptional cascade mediated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and ETHYLENE-RESPONSE-FACTOR1. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3703–14. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujimoto SY, Ohta M, Usui A, Shinshi H, Ohme-Takagi M. Arabidopsis ethylene-responsive element binding factors act as transcriptional activators or repressors of GCC box–mediated gene expression. Plant Cell. 2000;12:393–404. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.3.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yazaki K, Ogawa A, Tabata M. Isolation and characterization of two cDNAs encoding 4-coumarate:CoA ligase in Lithospermum cell cultures. Plant Cell Physiol. 1995;36:1319–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fujisaki T, Ohara K, Yazaki K. Characterization of an aromatic substrate prenyltransferase, LePGT-1, involved in secondary metabolism. Wood Res. 2003;90:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chao Q, Rothenberg M, Solano R, Roman G, Terzaghi W, Ecker JR. Activation of the ethylene gas response pathway in Arabidopsis by the nuclear protein ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE3 and related proteins. Cell. 1997;89:1133–44. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanagisawa S, Yoo S-D, Sheen J. Differential regulation of EIN3 stability by glucose and ethylene signalling in plants. Nature. 2003;425:521–5. doi: 10.1038/nature01984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji Y, Guo H. From endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to nucleus: EIN2 bridges the gap in ethylene signaling. Mol Plant. 2013;6:11–4. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miyata K, Kawaguchi M, Nakagawa T. Two distinct EIN2 genes cooperatively regulate ethylene signaling in Lotus japonicus. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54:1469–77. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhong S, Zhao M, Shi T, Shi H, An F, Zhao Q, et al. EIN3/EIL1 cooperate with PIF1 to prevent photo-oxidation and to promote greening of Arabidopsis seedlings. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:21431–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907670106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fang R, Wu F, Zou A, Zhu Y, Zhao H, Zhao H, et al. Transgenic analysis reveals LeACS-1 as a positive regulator of ethylene-induced shikonin biosynthesis in Lithospermum erythrorhizon hairy roots. Plant Mol Biol. 2016;90:345–58. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0421-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manamohan M, Chandra GS, Asokan R, Deepa H, Prakash M, Kumar NK. One-step DNA fragment assembly for expressing intron-containing hairpin RNA in plants for gene silencing. Anal Biochem. 2013;433:189–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2012.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rastogi S, Kumar R, Chanotiya CS, Shanker K, Gupta MM, Nagegowda DA, et al. 4-Coumarate: CoA ligase partitions metabolites for eugenol biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013;54:1238–52. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gan D, Zhang J, Jiang H, Jiang T, Zhu S, Cheng B. Bacterially expressed dsRNA protects maize against SCMV infection. Plant Cell Rep. 2010;29:1261–8. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0911-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu M, Chen G, Zhou S, Tu Y, Wang Y, Dong T, et al. A new tomato NAC (NAM/ATAF1/2/CUC2) transcription factor, SlNAC4, functions as a positive regulator of fruit ripening and carotenoid accumulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:119–35. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pct162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Höfgen R, Willmitzer L. Storage of competent cells for Agrobacterium transformation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:9877. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.20.9877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowra S, Vincze E. Transformation of rhizobia with broad-host-range plasmids by using a freeze-thaw method. Appl Environ Microb. 2006;72:2290–3. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.2290-2293.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sommer S, Köhle A, Yazaki K, Shimomura K, Bechthold A, Heide L. Genetic engineering of shikonin biosynthesis hairy root cultures of Lithospermum erythrorhizon transformed with the bacterial ubiC gene. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;39:683–93. doi: 10.1023/A:1006185806390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu P, Yuan J, Deng X, Ma M, Zhang H. Subcellular targeting of bacterial CusF enhances Cu accumulation and alters root to shoot Cu translocation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014;55:1568–81. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All supporting data can be found within the manuscript and its additional files.