Abstract

Mammalian hibernation is associated with multiple physiological, biochemical, and molecular changes that allow animals to endure colder temperatures. We hypothesize that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), a group of non-coding transcripts with diverse functions, are differentially expressed during hibernation. In this study, expression levels of lncRNAsH19 and TUG1 were assessed via qRT-PCR in liver, heart, and skeletal muscle tissues of the hibernating thirteen-lined ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus). TUG1 transcript levels were significantly elevated 1.94-fold in skeletal muscle of hibernating animals when compared with euthermic animals. Furthermore, transcript levels of HSF2 also increased 2.44-fold in the skeletal muscle in hibernating animals. HSF2 encodes a transcription factor that can be negatively regulated by TUG1 levels and that influences heat shock protein expression. Thus, these observations support the differential expression of the TUG1–HSF2 axis during hibernation. To our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence for differential expression of lncRNAs in torpid ground squirrels, adding lncRNAs as another group of transcripts modulated in this mammalian species during hibernation.

Keywords: Hibernation, Hypometabolism, Cold adaptation, Non-coding RNAs, lncRNAs

Introduction

Many small mammals undergo hibernation when confronted with unfavorable environmental conditions such as cold temperatures. Hibernation is characterized by a marked reduction in metabolism, prolonged periods where body temperatures (Tb) are significantly reduced (Tb ∼ 4 °C), a substantial reduction in heart rate, as well as resistance to skeletal muscle atrophy [1], [2], [3], [4]. Activity of several metabolic pathways are tightly controlled under these conditions notably via reversible protein phosphorylation of key regulatory enzymes [5]. Regulation of ATP-consuming processes such as gene transcription and protein translation is also a common theme observed in mammalian hibernation [6], [7], [8]. Molecular levers that are utilized to impact these two processes include, for example, histone deacetylases (HDACs) [9] and microRNAs (miRNAs) [10]. Nevertheless, the complete characterization of molecular players underlying mammalian hibernation is ongoing.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) typically longer than 200 nucleotides that affect diverse cellular functions including gene transcription and protein translation. lncRNAs have been notably shown to impact histone modifications [11], modulate transcription factor–promoter interaction [12], and influence mRNA stability [13]. Interestingly, several lncRNAs were shown to contain miRNA binding sites that could promote miRNA sequestration and subsequent inhibition of miRNA-mediated target recognition and expression [14], [15]. Differential expression of lncRNAs have been reported in a variety of conditions and processes relevant to hibernation including fasting and lipid metabolism [16], [17]. However, identification of torpor-associated lncRNAs has not been fully explored.

Since lncRNAs are involved in regulating crucial processes impacted during mammalian hibernation, the current study was conducted to evaluate the expression of two lncRNAs, H19 and taurine up-regulated gene 1 (TUG1), in liver, heart, and skeletal muscle tissues of the hibernating thirteen-lined ground squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus). H19 is one of the earliest lncRNAs identified [18], while TUG1 can influence the expression and activity of transcription factors relevant to hibernation [19], [20]. We report up-regulation of lncRNA TUG1 levels in the skeletal muscle of hibernating thirteen-lined ground squirrels and discuss the potential significance of this modulation in mammalian hibernation.

Results

Amplification of lncRNAs in thirteen-lined ground squirrels

Consensus sequences of H19 and TUG1 in mammalian species were generated for primer design. Target lncRNAs were subsequently amplified in liver, heart, and skeletal muscle tissues of ground squirrels via RT-PCR. The products PCR were confirmed by sequencing and the resulting H19 and TUG1 sequences were submitted to GenBank (GenBank accession Nos. KT305775 and KT305776). Figure S1 shows the nucleotide sequences of H19 and TUG1 aligned with the sequences for the human, mouse and rat lncRNAs. The partial H19 nucleotide sequence of ground squirrels displayed 75% homology with that of humans over the amplified region, respectively (Figure S1A). Similarly, the partial TUG1 nucleotide sequence was 86% homologous with that of humans over the amplified fragment. BLAST alignment of the full length human TUG1 (GenBank accession No. NR_110492.1) and thirteen-lined ground squirrel genome (SpeTri2.0 reference Annotation Release 101) revealed 74% conservation between sequences from humans and thirteen-lined ground squirrels (GenBank accession No. NW_004936523.1, scaffold 00055).

H19 and TUG1 expression in tissues of hibernating ground squirrels

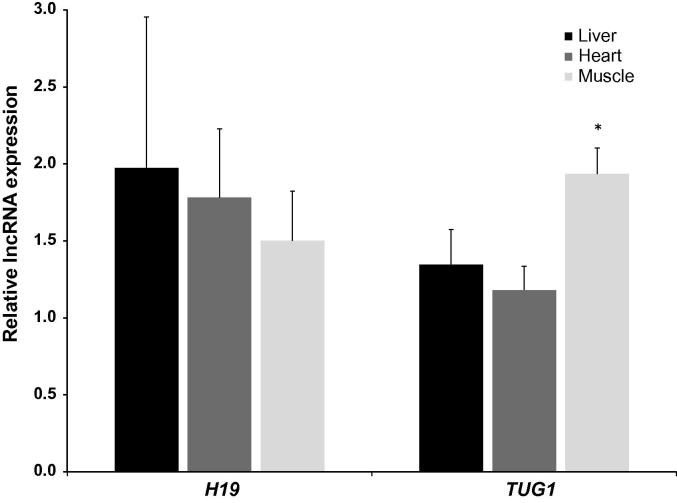

H19 and TUG1 transcript levels were examined in liver, heart, and skeletal muscle tissues of euthermic and hibernating ground squirrels. Relative levels of both transcripts were quantified in each tissue using qRT-PCR by normalization against that of α-tubulin in each sample. Figure 1 shows the ratio of normalized H19 and TUG1 transcript levels in the three tissues examined. Compared to euthermic animals, expression levels of TUG1 in the skeletal muscle of hibernating ground squirrels were 1.94 ± 0.17-fold of that from euthermic animals, which represents a significant increase (P < 0.005). On the other hand, although there is a trend of increased expression of H19 in hibernating animals, the changes are not significant due to the huge variations.

Figure 1.

Relative expression of H19 and TUG1 in hibernating ground squirrels

Histogram shows the ratios of normalized lncRNA expression levels against levels of α-tubulin measured via qRT-PCR in tissues from hibernating animals compared to euthermic animals. Data are standardized transcript levels (mean ± SEM, n = 6 biological replicates) in tissues from hibernating animals relative to those of the same lncRNA in tissues from euthermic animals. Significant difference from euthermic samples is indicated with an asterisk (t-test; P < 0.005).

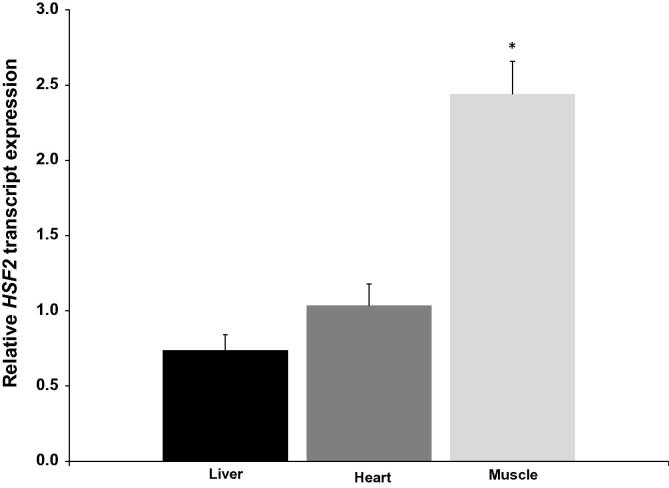

HSF2 expression in tissues of hibernating ground squirrels

The transcription factor heat shock factor 2 is encoded by HSF2, which is potentially modulated by TUG1 via miR-144 [21]. We thus measured HSF2 expression in liver, heart and skeletal muscle tissues of euthermic and hibernating animals using qRT-PCR by normalization against that of α-tubulin as above. Figure 2 shows the ratio of normalized HSF2 transcript levels in all tissues. HSF2 levels increased by 2.44 ± 0.22-fold in hibernating versus euthermic skeletal muscle tissues (P < 0.005). Compared to euthermic animals, expression levels of HSF2 in the skeletal muscle of hibernating animals were 2.44 ± 0.22-fold of that from euthermic animals, which represents a significant increase (P < 0.005), whereas the expression in heart and liver samples were comparable between euthermic and hibernating animals.

Figure 2.

Relative expression of HSF2 in hibernating ground squirrels

Histogram shows the ratios of normalized transcript levels of HSF2 against levels of α-tubulin measured via qRT-PCR in tissues from hibernating animals compared to euthermic animals. Data are standardized transcript levels (mean ± SEM, n = 6 biological replicates) in tissues from hibernating animals relative to those in tissues from euthermic animals. Significant difference from euthermic samples is indicated with an asterisk (t-test; P < 0.005).

miR-144 expression in skeletal muscle of hibernating ground squirrels

Previous work indicated that TUG1 can affect HSF2 expression via miR-144 in glioma cells [21]. Transcript levels of miR-144 were quantified in skeletal muscle tissues of ground squirrel using qRT-PCR. Expression of miR-144 in hibernating animals was 1.31 ± 0.30-fold of that in euthermic animals. However, this change was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

miR-144 binding site in human and ground squirrel TUG1 sequences

The miR-144 binding site in human TUG1 has been reported previously [21]. Interestingly, there is 74% homology between full length human TUG1 sequence and the whole genome shotgun sequence of the ground squirrels (contig043218; GenBank accession No. AGTP01043218.1). Sequence alignment also revealed a conserved (82.6%) miR-144 binding site in the ground squirrel sequence (Figure S2), suggesting there might exist TUG1–miR-144 interaction in the ground squirrels as for humans.

Discussion

Differential expression of ncRNAs in animal models of cold adaptation has garnered significant interest in the field over recent years. Modulation in expression of ncRNAs, in particular miRNAs, at low temperatures has been reported in small mammalian hibernators [22], [23], cold-hardy insects [24], and freeze-tolerant wood frogs [25]. Unlike miRNAs, lncRNAs have not been explored extensively in models of cold adaptation. Pioneering work in this area has revealed reduced levels of, a natural antisense lncRNA transcript of the gene encoding hypoxia inducible transcription factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α), aHIF, in skeletal muscle of torpid little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) [26] and has highlighted the potential translational regulation of HIF-1α during torpor by aHIF. Nevertheless, expression data on additional lncRNAs in bats and in other models of cold adaptation is lacking. In this study, we investigated the expression of lncRNAs H19 and TUG1 during hibernation in the thirteen-lined ground squirrel and reported differential expression of H19 in torpid skeletal muscle tissues.

This study reports for the first time H19 amplification and quantification in a mammalian hibernator. The lncRNA H19 is a 2.3-kb cytoplasmic transcript that, despite being capped, spliced and polyadenylated, is not translated into a protein [18]. Partial H19 sequence amplified in this study demonstrated appreciable sequence homology with known H19 sequences amplified from mammalian models. H19 can act as a molecular decoy to sequester and regulate the levels of let-7 [15], a miRNA that regulates several target genes in the insulin–PI3K–mTOR pathway such as INSR encoding insulin receptor and IGF1R encoding the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor [27], [28]. Through let-7 modulation, H19 levels have also been reported to influence glucose homeostasis in human and rodent models [29]. Interestingly, modulation of the insulin–PI3K–mTOR signaling cascade has been previously reported in torpid ground squirrels and little brown bats [30], [31]. However, our study revealed no significant change in H19 levels between euthermic and hibernating ground squirrels in liver, heart, and skeletal muscle samples examined. This observation appears to not support H19 involvement in mammalian hibernation.

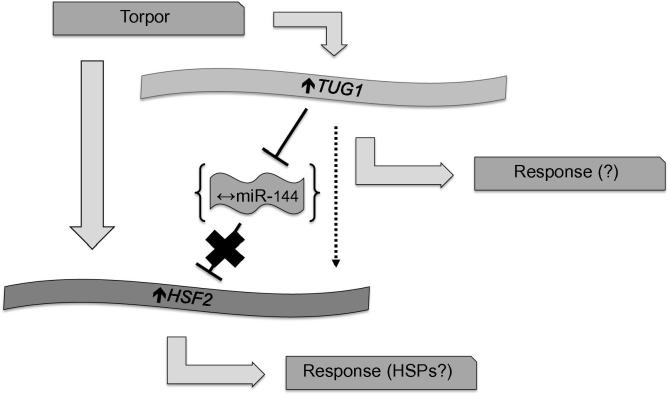

TUG1 amplification and quantification were also undertaken for the first time in a hibernating model. Early work on TUG1 reported substantial expression in adult rodent tissues and demonstrated its likely involvement in retinal development [32]. Recently, there is accumulating evidence supporting TUG1 implication in various types of cancer including hepatocellular [20], esophageal squamous cell [33], and non-small cell lung [19] carcinomas. Interestingly, TUG1 was strongly expressed in glioma vascular endothelial cells and modulated expression of HSF2 by acting as a competitive RNA, or decoy, for miR-144 [21]. Our current work reported TUG1 up-regulation in hibernating ground squirrel skeletal muscle tissues when compared with euthermic samples. Notably, HSF2 transcript levels were also increased, pointing toward a potential modulation of a TUG1–HSF2 axis in the skeletal muscle of torpid ground squirrels. HSF2 can transcriptionally regulate expression of different heat shock proteins (HSPs) [34] and there exists interplay between HSF2 and HSF1, a key driver of HSP expression [35]. Interestingly, elevated HSP levels have been reported in various models exposed to cold temperatures including the freeze-tolerant gall fly (Eurosta solidaginis) and the larvae of the freeze-tolerant midge (Belgica antarctica) [36], [37]. To figure out whether TUG1 differential expression impacts HSF2 levels via miR-144, we measured miR-144 transcript levels in skeletal muscle tissues of hibernating ground squirrels. However, no significant change in miR-144 expression was observed, suggesting that HSF2 up-regulation likely occurs in a miR-144-independent manner (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proposed working model of the TUG1–HSF2 axis

Torpor leads to up-regulation of TUG1 and HSF2 expression in the skeletal muscle of hibernating ground squirrels. miR-144 levels remain unchanged under the same conditions suggesting that TUG1 impact in torpor is likely via a miR-144-independent mechanism. HSP, heat shock protein.

It is important to point out that the miR-144 binding site observed in human TUG1 [21] appears to be conserved in ground squirrel TUG1 (Figure S2). While this observation supports the likely capability of TUG1 to act as a molecular decoy for miR-144, such interaction might not necessarily lead to the differential expression of miR-144 during torpor in ground squirrels. Regulation of miR-144 levels by TUG1 in ground squirrel thus warrants further investigation. In general, it will be interesting to build upon these results by investigating the likely molecular effectors that are affected by TUG1 differential expression and that are modulated downstream of a TUG1–miR-144 axis during torpor including miRNAs with predicted TUG1 binding sites.

Overall, the current work is one of the first studies to report lncRNA differential expression during torpor. Results gathered here thus provide novel insights into the function of ncRNAs, and especially lncRNAs, in mammalian models of hypometabolism. Future work will concentrate on the analysis of additional lncRNAs with potential relevance to cold adaptation as well as on the elucidation of the role of TUG1 in mammalian hibernation.

Materials and methods

Animals

Experimental procedures on thirteen-lined ground squirrels were performed as described before [38]. Squirrels weighing 150–300 g were captured by a trapper (TLS Research, Bloomingdale, IL) and transported to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) facility (Bethesda, MD) of the United States. Animals were kept in shoebox cages maintained at 21 °C and fed ad libitum until they accumulated sufficient lipid stores to enter torpor. Experimental procedures conducted on ground squirrels were reviewed and approved by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Animal Care and Use Committee. A sensor chip was injected subcutaneously in anaesthetized animals. Squirrels were moved to a dark cold room maintained at 4 °C–6 °C to induce hibernation. Tb and respiration rate were regularly monitored to identify the stage of torpor-arousal cycle. The animals constituting the hibernating group were sacrificed following a torpor period of at least five days (Tb 5 °C–8 °C), while the control animals had demonstrated stable Tb readings (34 °C–37 °C) for at least three days. All squirrels were sacrificed by decapitation. Tissues were shipped on dry ice to Université de Moncton in New Brunswick and stored at −80 °C until use.

Total RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from 100 mg of liver, heart, and skeletal muscle tissues of ground squirrels using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada) as described previously [39]. RNA concentration and purity were evaluated with a NanoVue Plus Spectrophotometer (VWR International, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and RNA samples were kept at −80 °C until use. First strand synthesis was next performed with 1 μg of total RNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and following manufacturer’s instructions. Serial dilutions of the synthetized cDNA were prepared in water and were used for PCR amplification of the different targets.

qRT-PCR amplification

Primers for target transcripts in ground squirrels were conceived using a consensus alignment sequence of known corresponding mammalian transcripts. Primer sequences are displayed in Table S1. H19, TUG1, and HSF2 were amplified via RT-PCR as described before [39] and PCR products were validated by sequencing. Subsequently, qRT-PCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green (Bio-Rad, Mississauga, ON, Canada) as described previously [40]. Amplification consisted of an initial step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s, optimal annealing temperature for 30 s and 72 °C for 60 s. α-tubulin was used as a housekeeping control. miR-144 transcript levels were quantified by qRT-PCR as described before, using miR-107 transcript levels as housekeeping control [10].

Quantification and statistical analysis

Quantification cycle (Cq) values were collected using the Bio-Rad CFX Manager software. Levels of target transcripts were normalized against those of α-tubulin amplified from the same cDNA sample. Transcript quantification was performed using the 2−ΔΔCt method [41]. Ratios of normalized transcript levels in hibernating samples to normalized transcript expression in euthermic samples were obtained. Significant differences (P < 0.005) between the two groups were evaluated with Student’s t-test.

Authors’ contributions

JF performed the experiments and wrote parts of the manuscript. DLO designed the PCR primers. PJM conceived the study, supervised the project, and wrote most of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. JM Hallenbeck and Dr. DC McMullen from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, MD, USA for providing ground squirrel tissues. This work was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Grant No. RGPIN/402222-2012) awarded to PJM.

Handled by Kyle K. Biggar

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences and Genetics Society of China.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2016.03.004.

Supplementary material

Alignment of partial H19 and TUG1 nucleotide sequences across different species. H19 (A) and TUG1 (B) sequences amplified from ground squirrels were aligned with corresponding sequences of the human, mouse and rat. GenBank accession numbers are NR_002196.2 (human), NR_130973.1 (mouse), and NR_027324.1 (rat) for H19, and NR_002323.2 (human), NR_002321.2 (mouse), and NR_130147.1 (rat) for TUG1, respectively. Spacer dots indicate missing nucleotides in one or more sequence.

miR-144 binding site in TUG1 sequences from human and ground squirrel. miR-144 potential binding site is found in human TUG1 (NR_110492.1, nucleotides 4725−4747) and ground squirrel genome shotgun sequence (AGTP01043218.1 nucleotides 7044−7190). miR-144 binding site is underlined in black and exhibits 82.6% conservation (19 out of 23 nucleotides). Spacer dots indicate missing nucleotides in one sequence.

Information of the primers used for qRT-PCR in this study.

References

- 1.Wang L.C.H., Lee T.F. Torpor and hibernation in mammals: metabolic, physiological, and biochemical adaptations. In: Fregley M.J., Blatteis C.M., editors. Handbook of physiology: environmental physiology. Oxford University Press; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geiser F. Metabolic rate and body temperature reduction during hibernation and daily torpor. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:239–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.115105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Storey K.B., Storey J.M. Metabolic rate depression: the biochemistry of mammalian hibernation. Adv Clin Chem. 2010;52:77–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brigham R.M., Ianuzzo C.D., Hamilton N., Fenton M.B. Histochemical and biochemical plasticity of muscle fibers in the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) J Comp Physiol B. 1990;160:183–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00300951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abnous K., Storey K.B. Skeletal muscle hexokinase: regulation in mammalian hibernation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;319:41–50. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9875-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frerichs K.U., Smith C.B., Brenner M., DeGracia D.J., Krause G.S., Marrone L. Suppression of protein synthesis in brain during hibernation involves inhibition of protein initiation and elongation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14511–14516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Breukelen F., Martin S.L. Reversible depression of transcription during hibernation. J Comp Physiol B. 2002;172:355–361. doi: 10.1007/s00360-002-0256-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osborne P.G., Gao B., Hashimoto M. Determination in vivo of newly synthesized gene expression in hamsters during phases of the hibernation cycle. Jpn J Physiol. 2004;54:295–305. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.54.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biggar Y., Storey K.B. Global DNA modifications suppress transcription in brown adipose tissue during hibernation. Cryobiology. 2014;69:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang-Ouellette D., Morin P., Jr. Differential expression of miRNAs with metabolic implications in hibernating thirteen-lined ground squirrels, Ictidomys tridecemlineatus. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;394:291–298. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang K.C., Yang Y.W., Liu B., Sanyal A., Corces-Zimmerman R., Chen Y. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature. 2011;472:120–124. doi: 10.1038/nature09819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung T., Wang Y., Lin M.F., Koegel A.K., Kotake Y., Grant G.D. Extensive and coordinated transcription of noncoding RNAs within cell-cycle promoters. Nat Genet. 2011;43:621–629. doi: 10.1038/ng.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kretz M., Siprashvili Z., Chu C., Webster D.E., Zehnder A., Qu K. Control of somatic tissue differentiation by the long non-coding RNA TINCR. Nature. 2013;493:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature11661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faghihi M.A., Zhang M., Huang J., Modarresi F., Van der Brug M.P., Nalls M.A. Evidence for natural antisense transcript-mediated inhibition of microRNA function. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R56. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-5-r56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kallen A.N., Zhou X.B., Xu J., Qiao C., Ma J., Yan L. The imprinted H19 lncRNA antagonizes let-7 microRNAs. Mol Cell. 2013;52:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang H., Modise T., Helm R., Jensen R.V., Good D.J. Characterization of the hypothalamic transcriptome in response to food deprivation reveals global changes in long noncoding RNA, and cell cycle response genes. Genes Nutr. 2015;10:48. doi: 10.1007/s12263-015-0496-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li P., Ruan X., Yang L., Kiesewetter K., Zhao Y., Luo H. A liver-enriched long non-coding RNA, lncLSTR, regulates systemic lipid metabolism in mice. Cell Metab. 2015;21:455–467. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brannan C.I., Dees E.C., Ingram R.S., Tilghman S.M. The product of the H19 gene may function as an RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:28–36. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang E.B., Yin D.D., Sun M., Kong R., Liu X.H., You L.H. P53-regulated long non-coding RNA TUG1 affects cell proliferation in human non-small cell lung cancer, partly through epigenetically regulating HOXB7 expression. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1243. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang M.D., Chen W.M., Qi F.Z., Sun M., Xu T.P., Ma P. Long non-coding RNA TUG1 is up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes cell growth and apoptosis by epigenetically silencing of KLF2. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:165. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0431-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai H., Xue Y., Wang P., Wang Z., Li Z., Hu Y. The long noncoding RNA TUG1 regulates blood-tumor barrier permeability by targeting miR-144. Oncotarget. 2015;6:19759–19779. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y., Hu W., Wang H., Lu M., Shao C., Menzel C. Genomic analysis of miRNAs in an extreme mammalian hibernator, the Arctic ground squirrel. Physiol Genomics. 2010;42A:39–51. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00054.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan L., Geiser F., Lin B., Sun H., Chen J., Zhang S. Down but not out: the role of microRNAs in hibernating bats. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyons P.J., Storey K.B., Morin P., Jr. Expression of miRNAs in response to freezing and anoxia stresses in the freeze tolerant fly Eurosta solidaginis. Cryobiology. 2015;71:97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biggar K.K., Dubuc A., Storey K. MicroRNA regulation below zero: differential expression of miRNA-21 and miRNA-16 during freezing in wood frogs. Cryobiology. 2009;59:317–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maistrovski Y., Biggar K.K., Storey K.B. HIF-1α regulation in mammalian hibernators: role of non-coding RNA in HIF-1α control during torpor in ground squirrels and bats. J Comp Physiol B. 2012;182:849–859. doi: 10.1007/s00360-012-0662-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu H., Shyh-Chang N., Segrè A.V., Shinoda G., Shah S.P., Einhorn W.S. The Lin28/let-7 axis regulates glucose metabolism. Cell. 2011;147:81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keniry A., Oxley D., Monnier P., Kyba M., Dandolo L., Smits G. The H19 lincRNA is a developmental reservoir of miR-675 that suppresses growth and Igf1r. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:659–665. doi: 10.1038/ncb2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao Y., Wu F., Zhou J., Yan L., Jurczak M.J., Lee H.Y. The H19/let-7 double-negative feedback loop contributes to glucose metabolism in muscle cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:13799–13811. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee K., So H., Gwag T., Ju H., Lee J.W., Yamashita M. Molecular mechanism underlying muscle mass retention in hibernating bats: role of periodic arousal. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:313–319. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu C.W., Bell R.A., Storey K.B. Post-translational regulation of PTEN catalytic function and protein stability in the hibernating 13-lined ground squirrel. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1850:2196–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Young T.L., Matsuda T., Cepko C.L. The noncoding RNA taurine upregulated gene 1 is required for differentiation of the murine retina. Curr Biol. 2005;15:501–512. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y., Wang J., Qiu M., Xu L., Li M., Jiang F. Upregulation of the long noncoding RNA TUG1 promotes proliferation and migration of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:1643–1651. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2763-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trinklein N.D., Chen W.C., Kingston R.E., Myers R.M. Transcriptional regulation and binding of heat shock factor 1 and heat shock factor 2 to 32 human heat shock genes during thermal stress and differentiation. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9:21–28. doi: 10.1379/481.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostling P., Björk J.K., Roos-Mattjus P., Mezger V., Sistonen L. Heat shock factor 2 (HSF2) contributes to inducible expression of hsp genes through interplay with HSF1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7077–7086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang G., Storey J.M., Storey K.B. Chaperone proteins and winter survival by a freeze tolerant insect. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57:1115–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rinehart J.P., Hayward S.A., Elnitsky M.A., Sandro L.H., Lee R.E., Jr., Denlinger D.L. Continuous up-regulation of heat shock proteins in larvae, but not adults, of a polar insect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14223–14227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606840103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McMullen D.C., Hallenbeck J.M. Regulation of Akt during torpor in the hibernating ground squirrel, Ictidomys tridecemlineatus. J Comp Physiol B. 2010;180:927–934. doi: 10.1007/s00360-010-0468-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morin P., Jr., Ni Z., McMullen D.C., Storey K.B. Expression of Nrf2 and its downstream gene targets in hibernating 13-lined ground squirrels, Spermophilus tridecemlineatus. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;312:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9727-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyons P.J., Crapoulet N., Storey K.B., Morin P., Jr. Identification and profiling of miRNAs in the freeze-avoiding gall moth Epiblema scudderiana via next-generation sequencing. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;410:155–163. doi: 10.1007/s11010-015-2547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Alignment of partial H19 and TUG1 nucleotide sequences across different species. H19 (A) and TUG1 (B) sequences amplified from ground squirrels were aligned with corresponding sequences of the human, mouse and rat. GenBank accession numbers are NR_002196.2 (human), NR_130973.1 (mouse), and NR_027324.1 (rat) for H19, and NR_002323.2 (human), NR_002321.2 (mouse), and NR_130147.1 (rat) for TUG1, respectively. Spacer dots indicate missing nucleotides in one or more sequence.

miR-144 binding site in TUG1 sequences from human and ground squirrel. miR-144 potential binding site is found in human TUG1 (NR_110492.1, nucleotides 4725−4747) and ground squirrel genome shotgun sequence (AGTP01043218.1 nucleotides 7044−7190). miR-144 binding site is underlined in black and exhibits 82.6% conservation (19 out of 23 nucleotides). Spacer dots indicate missing nucleotides in one sequence.

Information of the primers used for qRT-PCR in this study.