Abstract

Endothelial cells (ECs) have essential roles in organ development and regeneration, and therefore they could be used for regenerative therapies. However, generation of abundant functional endothelium from pluripotent stem cells has been difficult because ECs generated by many existing strategies have limited proliferative potential and display vascular instability. The latter difficulty is of particular importance because cells that lose their identity over time could be unsuitable for therapeutic use. Here, we describe a 3-week platform for directly converting human mid-gestation lineage-committed amniotic fluid–derived cells (ACs) into a stable and expandable population of vascular ECs (rAC-VECs) without using pluripotency factors. By transient expression of the ETS transcription factor ETV2 for 2 weeks and constitutive expression the ETS transcription factors FLI1 and ERG1, concomitant with TGF-β inhibition for 3 weeks, epithelial and mesenchymal ACs are converted, with high efficiency, into functional rAC-VECs. These rAC-VECs maintain their vascular repertoire and morphology over numerous passages in vitro, and they form functional vessels when implanted in vivo. rAC-VECs can be detected in recipient mice months after implantation. Thus, rAC-VECs can be used to establish a cellular platform to uncover the molecular determinants of vascular development and heterogeneity and potentially represent ideal ECs for the treatment of regenerative disorders.

INTRODUCTION

The ability to generate large numbers of human ECs would significantly augment therapies that target a variety of vascular-dependent maladies, including vessel damage, organ failure and hematopoietic dysfunction. A multitude of studies have shown that ECs contribute to tissue regeneration after liver and lung damage1–3, facilitate bone marrow recovery4–8, and can directly engraft into host vasculature9. Recent work has also shown that ECs are essential as instructive niches for the generation of hematopoietic cells and functional hepatocytes by reprogramming10,11. Thus, the development of a protocol that generates large amounts of pure and stable ECs would advance the development of novel treatments for vascular-related disorders, as well as treatments of diseases of different organ systems.

Cultivation of sufficient stable ECs for clinical applications has thus far proven to be exceedingly difficult. Mature or adult-derived ECs, such as human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) or liver sinusoidal ECs (LSECs), can only be passaged for a limited time in vitro. Therefore, many groups have generated ECs by directed differentiation of pluripotent cells or lineage conversion of other somatic cells12–20. The protocol described here, first used by Ginsberg et al.21, uses a direct conversion strategy and has unequaled efficiency; after 3 weeks, converted cells expand nearly 100-fold, and they are >80% VE-cadherin-positive21.

Comparison between directed differentiation and lineage conversion strategies

Directed differentiation, compared with lineage conversion, more closely recapitulates the lineage specification that occurs during development, and it does not require overexpression of reprogramming factors. Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) to ECs is typically 10–50% efficient13, 17, 18, 19, 20. In addition, ESC-ECs that are generated in this manner are not stably or fully committed13, 19 nor can they be broadly human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched. ECs generated from directed differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs) can be autologously transplanted, and two studies reported very high efficiencies, generating millions16 and trillions of ECs14. However, induced pluripotency–based techniques have led to tumorigenicity and immunogenicity, which are important potential disadvantages of such methods22, 23, 24. ECs derived from IPSCs also display varying degrees of stability and commitment. Although one group reported stable and homogeneous cells for over 18 passages14, another protocol generated bipotent progenitors that gave rise to smooth muscle and endothelial lineages16. Thus, lineage conversion of somatic cells to ECs may be safer because the starting population is more stable, and contaminating, unconverted cells are less likely to endanger recipients.

Although conversion of adult fibroblasts to ECs is appealing because cells can be autologously transplanted, the processes used thus far are only ~10% efficient15. Meanwhile, conversion of amniotic cells is far more efficient (80–90%), although it should be noted that products from both cell types do not express all endothelial genes15, 21. Indeed, a recent wide-ranging study showed that somatic cell conversion using fibroblasts is typically incomplete because the original lineage signature is difficult to erase25. Nevertheless, if the goal is to generate cells for therapeutic use in long-term engraftment, stability is paramount.

The varying efficiencies and stabilities associated with ECs generated in these studies, which are seen even when the same starting populations are used, highlight a need for consistency among the groups pursuing these ends and detailed protocols, such as this.

Rationale for this protocol

The protocol described here uses ACs as the starting population. ACs are obtained via amniocentesis during the mid-gestation period of human fetal development. Although this is an invasive procedure, 200,000 amniocentesis procedures are performed every year for diagnostic purposes, and after clinical analyses the cells are usually discarded. This results in a large number of ACs from diverse genetic backgrounds being obtained by cytogenetics facilities. This could enable the development of a HLA-matched library of source cells, which is currently not available from human ESC collections26. Several groups have had limited success in differentiating ACs into EC-like cells using defined growth conditions, and others have shown that these cells display lineage plasticity27, 28, 29, 30 This plasticity may underlie their amenability to endothelial reprogramming, which is similar to the superior efficiency of embryonic fibroblasts, compared with adult cells, in several reprogramming strategies31, 32, 33, 34 It is unknown whether the increased efficiency of amniotic cells is common to all mid-gestation tissue or whether it is unique to amniotic cells. This issue should be addressed by comparing the convertibility of different amniotic tissues, such as a term amniotic mesenchymal stromal cells, which are present in the placenta35.

In a recent study, we demonstrated that ACs constitute a novel source of abundant and readily accessible nonvascular cells that can be reprogrammed into vascular ECs (rAC-VECs) with defined transcription factors (TFs). rAC-VECs possess an angiogenic and vascular functional profile that matches mature bona fide ECs21. The reprogramming platform that we used, and describe here, does not require the addition of pluripotency factors, and this augments the durability and stability of these highly proliferative rAC-VECs. As numerous studies had documented the role of the E-twenty six (ETS) family of TFs (ETS-TFs) as essential regulators of vascular development and angiogenesis36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, we surmised that these TFs could be ideal candidates for reprogramming nonvascular cells into ECs. After a lengthy screening process using numerous ETS-TFs (as well as several non-ETS-family TFs), we identified ETV2, ERG1 and FLI1 to be the most efficient factors for reprogramming ACs into rAC-VECs21. Through overexpression of these ETS-TFs along with short-term inhibition of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling, we successfully generated a population of expandable ECs that were stable over numerous passages in vitro, and engrafted into mouse host microvasculature where they remained viable for 3 months. To recapitulate developmental programs, overexpression of ETV2 for only 2 weeks was sufficient to complete the reprogramming process into rAC-VECs. Global transcriptome analyses demonstrated that rAC-VECs express a vascular signature that is nearly identical to that of other mature EC populations, such as HUVECs and LSECs, while differing significantly from nonvascular cell types. This comprehensive genome-wide analysis also revealed that the ES-derived EC expression profile was markedly different from that of the rAC-VEC, HUVEC and LSEC profiles, accentuating the notion that ACs may represent a preferable cell source to pluripotent stem cells for reprogramming.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

The principle components of this protocol include the transduction of ACs with specific ETS-TFs (via lentiviral infection) and the use of culture conditions that suppress TGFβ signaling. The time frame of this platform is ~3 weeks, beginning with the initial lentiviral infection of ACs with ETV2, ERG1 and FLI1. Examination of gene expression (via qPCR analysis21) and surface marker presentation (via FACS analysis21) revealed that ACs transduced with these ETS-TFs gradually acquire an EC phenotype during the reprogramming process (Fig. 1a), whereas untransduced ACs do not. By the fourth week of the protocol (days 21–28), rAC-VECs are established. They demonstrate a robust proliferative potential and are stable, having acquired a global transcriptome profile that is highly similar to other authentic EC populations, including HUVECs and LSECs21. We have confirmed that the rAC-VECs obtained using the protocol were not derived from pre-existing endothelial precursor or pluripotent subpopulations of amniotic cells, as rAC-VECs could have been generated from such populations by simply incubating them with endothelial growth conditions (Fig. 1b). The rAC-VECs obtained from this protocol represent a reprogrammed cell population that is dependent on three essential TFs that initiate a transcriptional program that establishes EC identity.

Figure 1. The rAC-VEC platform is a 3–4 week reprogramming process that requires the transduction of specific transcription factors (TFs).

(a) Schematic model outlining the time course of reprogramming amniotic cells (ACs) into vascular endothelial cells (rAC-VECs) via transduction with ETV2, FLI1 and ERG1 (ETS-TFs). In addition, cells were cultured in the presence of TGF-β inhibitor (SB431542, 5 μM). By day 7, mRNA expression of numerous endothelial cell (EC) genes is observed. Within 3–4 weeks, surface protein expression of multiple EC genes, including VE-cadherin, VEGFR2 and CD31 is observed. For detailed results, please refer to the original Ginsberg et al.21 Cell paper. (b) Immunostaining of cells cultured for 21 d in EC growth medium. There is no accumulation of VE-cadherin (red) or CD31 (green) in ACs cultured in ideal EC growth conditions for 21 d (top). Contrarily, HUVECs express both VE-cadherin and CD31 (bottom). Thus, in the absence of ETS-TFs, ACs do not differentiate into ECs. Nuclei are stained with DAPI (white). Antibodies used are stated at Step 11. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Alternative platform described in the protocol

Although ETV2, ERG1 and FLI1 are highly effective in the generation of rAC-VECs from ACs, our initial studies revealed that several key EC genes remained inactive in these reprogrammed cells, including CD31 (officially known as PECAM1). Because it had been previously reported that ETV2 is only expressed briefly during embryonic development and that it is seemingly absent in nearly all adult EC beds39, we designed a conditionally active ETV2 (TRE-ETV2) construct that could be suppressed with doxycycline in vitro, thus partially mimicking the physiological expression pattern of ETV2 in vivo. In this modified platform, ACs are transduced with TRE-ETV2 (in addition to constitutively active ERG1 and FLI1) for 2 weeks, at which time doxycycline is introduced into the growth medium. By week 4 of the protocol (i.e., 7–14 d after ETV2 is turned off), rAC-VECs are established. However, CD31 proteins and numerous other mature vascular specific genes are expressed in these cells, suggesting that abbreviated induction of ETV2 is ideal for the generation of mature rAC-VECs. Incidentally, ACs transduced with only ERG1 and FLI1 (i.e., in the absence of ETV2) fail to generate rAC-VECs, as these cells do not proliferate efficiently beyond 4 weeks post lentiviral transduction, suggesting that initial induction with ETV2 is essential for specification of amniotic cells into rAC-VECs. Last, it should be noted that although rAC-VECs generated with TRE-ETV2 are still highly proliferative, these cells will expand to a lesser degree than rAC-VECs produced with constitutively active ETV2. Thus, we also describe the generation of rAC-VECs with conditional TRE-ETV2 below.

MATERIALS

REAGENTS

-

-

Amniotic fluid–derived cells (ACs). We obtain these primary cells from the Cytogenetic Laboratory Department of Pathology at Weill Cornell Medical College (WCMC). Research-use-only ACs may be available from alternative cytogenetic laboratories, or there are several companies that provide commercially available ACs for research use, such as Angiocrine Bioscience (with which several of the authors herein are affiliated) and BioCell.

CAUTION: Properly inform the deidentified donors that these cells are for research, and obtain a signed consent form. The protocol must conform to relevant governmental and institutional regulations.

-

-

AC growth media (see Reagent Setup)

-

-

Amnio-Max base media, for AC media (GIBCO: #17001-074)

-

-

Amnio-Max Supplement, for AC media (GIBCO: #12556-023)

-

-

Antibiotic-antimycotic solution, for all media (Invitrogen, cat. no. 15240-062)

-

-

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) (Cellgro: #21-030-CV)

-

-

Fibronectin (Sigma: # F0895-5MG)

-

-

DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich: #D2650)

-

-

Trizma Base (Sigma-Aldrich: T6066)

-

-

Sodium Chloride (NaCl) (Sigma: S5886)

-

-

EDTA (pH 8.0) (Promega: V4231)

-

-

Endothelial growth media (see Reagent Setup)

-

-

Medium 199 (Hyclone: #SH30253.01)

-

-

Advanced DMEM/F12 (Life Technologies: #12634-010)

-

-

Fetal Bovine Serum (Omega Scientific: FB-11)

-

-

Knockout Serum Replacement (Life Technologies: #10828028)

-

-

Endothelial cell supplement (Biomedical Technologies: #BT-203)

-

-

Human VEGF-A (Peprotech: #100-20)

-

-

Human FGF-2 (Peprotech: #100-18B)

-

-

Heparin (Sigma: # H3149-100KU)

-

-

Small molecule SB431542 (Tocris: SB431542)

-

-

HEPES buffer 1M (Invitrogen: 15630-080)

-

-

L-Glutamine 200 mM (Invitrogen: 25030-081)

-

-

Doxycycline (Clontech: #631311)

-

-

Accutase (EBiosciences: #00-4555-56)

-

-

Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco: 25200114)

-

-

DMEM/High Glucose (Hyclone: #SH30243.02)

-

-

qPCR primers for cell identification (see SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE 1 in SUPPLEMENTARY MANUAL – all primers were purchased from IDT)

-

-

Antibodies for cell identification (see TABLE 1)

-

-

TGFβ ligand neutralizing monoclonal antibody (R&D: #MAB1835)

-

-

RNeasy extraction kit (Qiagen: #74106)

-

-

QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen: #205313)

-

-

SYBR Green PCR mix (Applied Biosystems: #4309155)

-

-

Micro-amp Fast Optical 96-well plates (Applied Biosystems: #4346906)

-

-

Materials for lentiviral production (see BOX 1 – LENTIVIRAL PRODUCTION)

TABLE 1.

Antibodies for FACS/Immunostaining

| Target | Application(s) | Supplier and cat. no. |

|---|---|---|

| VE-cadherin | FACS | eBioscience, cat. no. 17-1449-42 |

| VE-cadherin | Immunostaining | R&D, cat. no. AF938 |

| VEGFR2 | FACS and immunostaining | R&D, cat. no. FAB357P |

| CD31 | FACS and immunostaining | eBioscience, cat. no. 11-0319-42 |

Box 1. Lentiviral production • TIMING ~1 week.

We generate lentiviruses using the Xfect transaction reagent, the Lenti-X HTX packaging system and the Leti-X concentrator (along with their corresponding protocols), all from Clontech. We titer antiviruses using the Lenti-X p24 rapid titer kit, also from Clontech. A brief outline of the rentiviral preparation and some important points to hear in mind are given below.

Materials

HEK 293T cells (American Type Culture Collection, cat. no. CRL-11268) ! CAUTION All cell lines used in your research should be routinely checked for authenticity and for bacterial/mycoplasma contamination.

Lentiviral growth medium (see Reagent Setup in this box)

Lentiviral storage buffer (see Reagent Setup in this box)

pCCL lentiviral vectors encoding human ETV2, human FLI1, human ERG1 and GFP. Constructs generated by GeneCopoeia—these constructs are constitutively activated by the PGK promoter. Further details of these constructs can be found in Reagent Setup. Note that ETV2 was also cloned into doxycycline-dependent Tet-Off construct. This vector was purchased from Clontech, cat. no. 632158. Further details of this construct can be found in the main MATERIALS section, under the subheading PLasmids.

Lenti-X p24 rapid titer kit (Clontech, cat. no. 632200)

Lenti-X concentrator (Clontech, cat. no. 631232)

Lenti-X HTX packaging system (Clontech. cat. no. 631249)

Xfect transfection reagent (Clontech, cat. no. 631318)

Reagent setup

Lentiviral growth medium. Lentiviral growth medium contains DMEM/high-glucose medium, 10% (vol/vol) FBS and 100 U ml−1 antibiotic-antimycotic. To prepare 500 ml of lentiviral growth medium, add 55 ml of FBS to a 500-ml bottle of DMEM/high-glucose medium and mix in 5.5 ml of antibiotic-antimycotic solution. ▲ CRITICAL Filter-sterilize the medium in a 500-ml filter system 0.22-μm bottle and store the medium in the dark at 4 °C; use it within 4 weeks.

Lentiviral storage buffer. Lentiviral storage buffer contains 50 mM Tris (pH 7.8). 1 mM EDTA and 130 mM NaCl all dissolved in water. To prepare 50 ml of lentiviral storage buffer, mix 2.5 ml of 1 M Tris with 0.1 ml of 500 mM EDTA and 1.3 ml of 5 M NaCL. Bring it up to 50 ml with water and filter-sterilize it through a 0.2-μm syringe filter. Store it at 4 °C (good for at least 1 year).

Procedure

! CAUTION This procedure should be conducted in a tissue culture hood, and waste products should be disposed of properly.

Thaw one vial of HEK 293T cells. Count and plate ~2 × 106 cells onto a 10-cm culture dish in 10 ml of lentiviral growth medium. Place the dish in a 37 °C incubator.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Lentiviral growth medium should always be prewarmed to 37 °C in a water bath before use.

When the cells are confluent (usually in 24–48 h), aspirate the medium. Wash the cells with DPBS, aspirate and add 2–3 ml of trypsin-EDTA. Incubate the cells with trypsin for 2–3 min.

When the cells have detached from the dish, add 7 ml of lentiviral growth medium. Pipette the cells up and down around the surface of the dish to retrieve maximum number of cells, and transfer them to a 15-ml conical tube.

Centrifuge the tube at 400g for 5 min at 4 °C. Aspirate the supernatant, and resuspend the cell pellet in 10 ml of lentiviral growth medium. Count and plate ~3 × 106 cells into the desired number of 10-cm dishes for lentiviral preparation (after counting and plating cells, add lentiviral growth medium for a final volume of 8 ml per dish).

▲ CRITICAL STEP The number of 293-plated dishes to make virus is at the discretion of the researcher. At least one 10-cm dish per construct (i.e., ETV2, ERG1 and FLI1) is required for producing the viruses necessary to generate rAC-VECs. In addition, lentivirus for the pTA (trans-activator plasmid, for the TRE-expression system) construct must be made here as well, if the researcher wishes to use TRE-ETV2 construct in place of the constitutive ETV2 construct in the reprogramming platform. Generally, one 10-cm dish per construct will generate sufficient virus for several experiments. However, it is recommended that large quantities of virus be produced during a single virus preparation whenever possible, such that batch-to-batch variations are kept to a minimum. As such, we usually plate three or four 10-cm dishes of HEK 293T cells per construct (i.e., three or four dishes each for ETV2. ERG1, FLI1,TRE-ETV2 and pTA), which will afford a large stockpile of virus that can be used over many months. To do this, simply expand the HEK 293T cells in lentiviral growth medium (steps 2 and 3 in this box) until the desired number of cells has been attained for lentiviral preparation.

After 18–24 h, the cells should be ~60–70% confluent. Prepare the Polyfect/DNA complexes as directed by the manufacturer’s instructions (Clontech, cat. no. 631318 and cat. no. 631249). Add Polyfect/DNA complexes dropwise onto the cells and place the dish in a 37 °C incubator.

After 12–18 h, aspirate the medium and refeed it with 8 ml of lentiviral growth medium. When you are adding fresh medium to the cells, do so very slowly and gently, as the cells can detach from the dish quite easily at this stage. Place the dish in a 37 °C incubator.

After 36–48 h, collect the supernatant (medium) from each dish and transfer it to 50-ml conical tubes. Supernatant from multiple dishes of the same viral preparation (i.e., multiple dishes that are all producing the ERG1 virus) can be combined and added to the same 50-ml conical tube.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Do not mix supernatants from different viral preparations.

Centrifuge the supernatant at 400g for 5 min at 4 °C (this will pellet any cellular debris). Using care not to disrupt the pellet, filter the supernatant through a 0.45-μm syringe filter into new 50-ml conical tubes (for large volumes of supernatant, 150 ml filter system 0.45-μm bottles can be used).

▲ CRITICAL STEP When you are filtering the supernatant, only use cellulose acetate or polyethersulfone (PES) low-protein-binding filters.

For every three volumes of filtered supernatant, add one volume of Lenti-X concentrator (i.e., for 15 ml of supernatant, add 5 ml of Lenti-X concentrator). Mix it by inversion, and place it at 4 °C for at least 1 h.

■ PAUSE POINT After the addition of Lenti-X concentrator, samples can be stored at 4 °C for up to 1 week before continuing to step 10.

After 1 h, centrifuge samples at 1,500g for 45 min at 4 °C. A white pellet should be visible after centrifugation.

▲ CRITICAL STEP The presence of a white pellet does not guarantee the presence of competent viral particles. Verification of active virus must still be performed by the researcher.

Gently aspirate the supernatant, being careful not to disturb the pellets. Resuspend the pellets in 500 μl of lentiviral storage buffer per 10-cm dish used to make virus (i.e., if four 10-cm dishes of HEK 293T cells were used to produce the ERG1 virus, then this pellet should be resuspended in 2 ml of lentiviral storage buffer). Dispense the resuspended pellets into Eppendorf tubes in 50-μl aliquots, and immediately store them at −80 °C.

▲ CRITICAL STEP The volume of lentiviral storage buffer used to resuspend the viral pellets will vary depending on the efficiency of the lentiviral preparation, and it should be determined empirically by the researcher. We have found that resuspending the viral pellets in 500 μl of storage buffer for each 10-cm dish used to make a particular virus affords a suitable working concentration of virus that can be added in small guantities for infection into ACs.

▲ CRITICAL STEP Once the lentivirus is resuspended in lentiviral storage buffer, it is highly unstable at temperatures below −20 °C. Similarly, repeated freezing and thawing of lentivirus substantially reduces their infection efficiency. As such, we recommend that a single aliguot be thawed and frozen not more than one or two times before infection. In addition, immediately upon thawing, the virus should be added to the ACs for infection. Lentivirus should never be stored at 4 °C, even for short-term storage.

■ PAUSE POINT Lentivirus can be stared at −80 °C for at least 1 year.

Thaw one aliguot on ice for each lentivirus that was generated, and titer the virus using a Lenti-X p24 rapid titer kit (follow the protocol provided by the kit). Calculate the titer in units of picograms per μl. and record the results.

▲ CRITICAL STEP This procedure can take ~4–5 h, and thus we generally conduct the titer assay the day after our viruses have been collected and stored at −80 °C. However, if time permits, the researcher can conduct the titer assay on the same day as the virus was collected and stored. If this is done, it is recommended that the researcher still freeze and then thaw an aliquot of virus, so as to account for any freeze/thaw effects that can alter the titer of the virus.

Troubleshooting guidance

If there is a low titer readout, it could be because of low-quality or mutated plasmids (action: verify plasmid integrity by restriction enzyme digestion and/or sequencing); poor lentiviral preparation (action: remake virus); improper use of or faulty p24 kit (action: contact manufacturer for technical assistance); and sub-par HEK293 cells (action: obtain fresh/low-passage HEK293 cells).

Expected results

The results of the titering assay will vary depending on the efficiency of the lentiviral preparation (see above for troubleshooting information). Generally, the titers of our lentiviruses fall in the range of 500–5,000 pg μl−1. If the researcher desires a more concentrated or more diluted stock of the virus, this can be easily achieved by altering the amount of lentiviral storage buffer used to resuspend the viral pellets (step 11 in this box). We prefer this range for our lentiviral stocks, in that we have found that adding ~25,000 pg of each virus per well (six-well format—see the main PROCEDURE section, Step 7) will efficiently infect the ACs for reprogramming into rAC-VECs.

EQUIPMENT

-

-

Forma Class II, A2 Biological Safety Cabinet (Thermo Scientific: model #1286)

-

-

Forma Series II, water-jacket CO2 incubator, set at 37°C and 5% CO2 (Thermo Scientific: model #3130) – referred to as ‘37°C incubator’ in text

-

-

Forma Series II, water-jacket CO2 incubator, set at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 5% O2 (Thermo Scientific: model #3130) – referred to as ‘Low Oxygen 37°C incubator’ in text

-

-

Isotemp 210 Water Bath (Fisher Scientific: #1338)

-

-

Digital inverted microscope (EVOS)

-

-

Confocal/fluorescence microscope (710 META Zeiss)

-

-

Swinging rotor centrifuge and adaptors for 15 ml and 50 ml conical tubes (Thermo Scientific: model # Multifuge X1R)

-

-

7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems)

-

-

Flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, LSRII SORP)

-

-

Tissue culture–treated plates and flasks

-

-

Filter system bottles, 500 ml, 0.22-μm filter (Corning, cat. no. 430769)

-

-

Filter system bottles, 150 ml, 0.45-μm filter (Corning, cat. no. 431155)

-

-

Syringe filter, 0.2 μm (VWR International, cat. no. 28145-501)

-

-

Syringe filter, 0.45 μm (VWR International, cat. no. 28145-505)

-

-

Syringes, 10, 30 and 60 ml (BD Biosciences, cat. no. 309604, cat. no. 309650 and cat. no. 309654, respectively)

-

-

Polypropylene conical tubes, 15 ml (Falcon, cat. no. 352097)

-

-

Polypropylene conical tubes, 50 ml (Falcon, cat. no. 352098)

-

-

Eppendorf tubes, 1.7 ml (Denville, cat. no. C-2170)

-

-

Nalgene cell freezing containers (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. no. C1562)

-

-

Cryovials (for liquid nitrogen storage of cells)

REAGENT SETUP

AC growth media

AC growth medium contains AmnioMax base medium, AmnioMax supplement and 100 U ml−1 antibiotic-antimycotic. To prepare 500 ml of AC medium, add the entire bottle of AmnioMax supplement into AmnioMax base medium, and mix it in 5 ml of antibiotic-antimycotic solution.

CRITICAL: Filter-sterilize the medium in a 500-ml filter system 0.22-μm bottle; store the medium in the dark at 4 °C and use it within 4 weeks.

SB431542 preparation

To prepare aliquots of SB431542 for endothelial growth medium, add 470 μl of DMSO to 10 mg of SB431542. This will generate a 50 mM stock (10,000×) solution of SB431542. Dispense 50-μl aliquots of stock solution into tubes and store them at −80 °C (stable for at least 1 year). When you are preparing 500 ml of endothelial growth medium, thaw out and mix it in one aliquot (50 μl) of SB431542.

Endothelial growth media

Endothelial growth medium contains medium 199, supplemented with 15% (vol/vol) FBS, 15 mM HEPES, 50 μg ml−1 EC supplement, 50 μg ml−1 heparin, 100 U ml−1 antibiotic-antimycotic, 2 mM L-glutamine and 5 μM SB431542. To prepare 500 ml of endothelial growth medium, mix together 75 ml of FBS, 7.5 ml of HEPES, 5 ml of antibiotic-antimycotic solution, 5 ml of L-glutamine, 25 mg of heparin, 25 mg of EC supplement and one aliquot (50 μl) of SB431542, and fill it to 500 ml with medium 199.

CRITICAL: Filter-sterilize the medium in a 500-mlfilter system 0.22-μm bottle and store the medium in the dark at 4 °C; use it within 4 weeks.

CRITICAL: We have shown that using the TGF-β ligand–neutralizing monoclonal antibody in place of SB431542 is equally effective in blocking TGF-β signaling in this platform. If desired, add 10 μg ml−1 TGF-β ligand–neutralizing monoclonal antibody every 2–3 d to cells cultured in endothelial growth medium prepared without SB431542.

Defined serum-free media

Defined serum-free medium is a knockout serum replacement (KSR)-based medium supplemented with VEGF-A and FGF-2 that can be used as an alternative to endothelial growth medium. Defined serum-free medium contains advanced DMEM/F12, supplemented with 20% (vol/vol) KSR, 50 μg ml−1 heparin, 100 U ml−1 antibiotic-antimycotic, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 ng ml−1 FGF, 20 ng ml−1 VEGF-A and 5 μM SB431542. To prepare 500 ml of defined serum-free medium, mix together 100 ml of KSR, 5 ml of antibiotic-antimycotic solution, 5 ml of L-glutamine, 25 mg of heparin, 5 μg of FGF-2, 10 μg of VEGF-A and one aliquot (50 μl) of SB431542, and fill it to 500 ml with advanced DMEM/F12.

CRITICAL: Filter-sterilize the medium in a 500-ml filter system 0.22-μm bottle and store the medium in the dark at 4 °C; use it within 4 weeks.

Doxycycline

To prepare aliquots of doxycycline for use, dissolve 10 mg of doxycycline into 5 ml of sterile water. This will generate a 2 mg ml−1 stock (1,000×) solution. Dispense 0.5-ml aliquots into tubes and store them at −20 °C to avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles (good for at least 6 months). When treating cells with doxycycline, thaw one aliquot and remove a suitable amount that will be needed for the duration of the experiment, and then store it at 4 °C (this can be kept at 4 °C for up to 1 month).

Fibronectin-coated plates

Coat all plates and/or flasks with fibronectin solution (1 mg ml−1 fibronectin in Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS)) before platingof cells. After adding fibronectin solution to plates or flasks, leave them at room temperature (20–25 °C) in a tissue culture hood for a minimum of 30 min. Aspirate fibronectin solution away, and use coated plates or flasks right away for cell plating, or store them at 4 °C (good for at least 3–4 weeks).

PLASMIDS

pCCL ETV2, ERG1, FLI1 constructs

To generate constitutively expressing gene products for lentiviral transduction, clone cDNAs encoding ETV2, ERG1 and FLI1 into the lentiviral backbone pCCL-PGK lentivirus vector (our construct work was performed by GeneCopoeia: http://www.genecopoeia.com/). Further modifications to ETV2 and ERG1 can be performed as previously described21. Briefly, insert a triple Flag-tag into the amino terminus of ETV2 and ERG1 for the purpose of identification via western blot analysis. The lack of high-quality antibodies to detect human ETV2 and ERG1 necessitates this modification. No Flag-tag needs to be added to human FLI1, because commercial antibodies are sufficient to detect this protein. The pCCL-PGK-based plasmids are all capable of generating high levels of transcript for each gene of interest. Furthermore, no silencing of these genes is observed during the reprogramming platform (or thereafter). Last, the presence of the Flag-tag has no effect in altering the outcome of the reprogramming strategy. These plasmids are available for noncommercial use from the corresponding author of this paper, S.R., and further information about the availability and design of these plasmids can be obtained by contacting him directly. (See also plasmid maps in Supplementary Manual.)

pLVX-Tight-Puro ETV2 Tet-Off construct

The ETV2 Tet-Off construct can be generated as previously described21. Briefly, the open reading frame of the Flag-tagged ETV2 is subcloned out from the pCCL-PGK ETV2 plasmid (described above) and into the pLVX-Tight-Puro vector to control the expression of ETV2 via doxycycline addition. In the presence of doxycycline, ETV2 is not expressed. At the desired time for the suppression of ETV2, add 1 μl of doxycycline stock per 1 ml of endothelial growth medium (final concentration will then be 2 μg ml−1). Treat the plasmid every 2–3 d with fresh doxycycline for the suppression of ETV2. As with the pCCL-PGK–based plasmids (described above), the pLVX-Tight-Puro ETV2 plasmid also shows good expression of the gene product (albeit less expression than the pCCL-PGK ETV2 construct) in the absence of doxycycline, and without any indication of gene silencing over time. Upon treatment with doxycycline, protein expression drops to undetectable levels within 48 h, and it will remain suppressed in the presence of freshly added doxycycline to the medium every 2–3 d. This plasmid is available for noncommercial use from the corresponding author of this paper, S.R., and further information about availability and design of this plasmid can be obtained by contacting him directly. (Also see plasmid maps in Supplementary Manual.)

Caution: Lentivirus vectors are relatively unstable, and they should be propagated in appropriate bacteria and grown at 30 degrees instead of 37. If virus production is consistently poor, it is possible that features of the vector, such as the long terminal repeats (LTRs), are mutated and damaged. Sequencing of the entire plasmid(s) to determine that it is intact may be necessary if virus production is consistently poor.

CRITICAL: When you are using the pLVX-Tight-Puro construct plasmid, it is essential that the pTA plasmid (also supplied in the kit from Clontech) be used as well. The pTA plasmid produces the factor that activates the gene of interest (i.e., in this case ETV2) in the Tight-Puro construct plasmid. Therefore, lentiviral particles for both of these plasmids must be made, and subsequently both of these viruses must be co-infected for the expression of ETV2 using this system.

PROCEDURE

Lentivirus preparation: Timing ~ 1 week

-

1)

Generate and titer lentivirus. The method for lentiviral production we use is described in BOX 1. Although alternative methods may be used to generate lentivirus, we cannot guarantee similar results of efficacy in the reprogramming platform described herein. CAUTION This and all subsequent steps in which cells or viruses are manipulated should be conducted in a tissue culture hood, and waste products should be properly disposed of.

Culturing of ACs: Timing ~1 d – 2 weeks

-

2)

Culture ACs to confluency. We obtain AC samples from our cytogenetics department via two distinct formats: “Fresh unmanipulated” ACs and “Pre-cultured” ACs. The procedures for handling these types of sample are described in options A and B below. Unless otherwise directed, ACs obtained from an outside company should be cultured via Option B (i. e. “Precultured” procedure).

Option A) Culture of “Fresh unmanipulated” AC samples:

CRITICAL “Fresh unmanipulated” AC samples are usually received in our lab within several hours of their initial collection from the patient. While it is ideal to immediately transfer these samples into culture conditions as described below, we have found that these samples can be stored at 4°C for up to 24 h with little loss of cell viability.

Place ACs in a 15 ml conical tube and centrifuge at 400g for 10 min at 4°C.

Aspirate the supernatant, and resuspend the cell pellet in 1 ml of AC growth media.

Transfer cells/media to 1 well of a 12-well plate and place in a 37°C incubator (Fig. 2a). CRITICAL STEP AC growth media should always be pre-warmed to 37° in a water bath before use

After 3 d, transfer supernatant from the 1st well to a 2nd well of the same 12-well plate, and re-feed the 1st well with 1 ml AC growth media (Fig. 2b). Place the 12-well plate in a 37°C incubator. CRITICAL STEP It is common to observe that the majority of the cells transferred into the 1st well of the plate do NOT adhere to the surface (Fig. 2b). As such, they are re-plated into a 2nd well to obtain a greater yield of cells.

After 3 d, aspirate the supernatant from the 1st and 2nd wells, and re-feed each well with 1 ml AC growth media. Place the 12-well plate in a 37°C incubator. When the wells are confluent (usually in another 7 – 10 d, see Figure 2 for typical morphologies of cells), proceed to Step 3. CRITICAL STEP As was the case in the previous step, it is common that the majority of cells transferred into the 2nd well of the plate do NOT adhere to the surface. In fact, following aspiration of the 1st and 2nd wells of the plate, very few cells will be present. This is normal, and expansion of these few cells will begin within the next few days (Fig. 2c – 2f). The majority of these cells will expand into either epithelial (Type E) ACs (Fig. 2c–2d) or fibroblastic (Type F) ACs (Fig. 2e–2f).

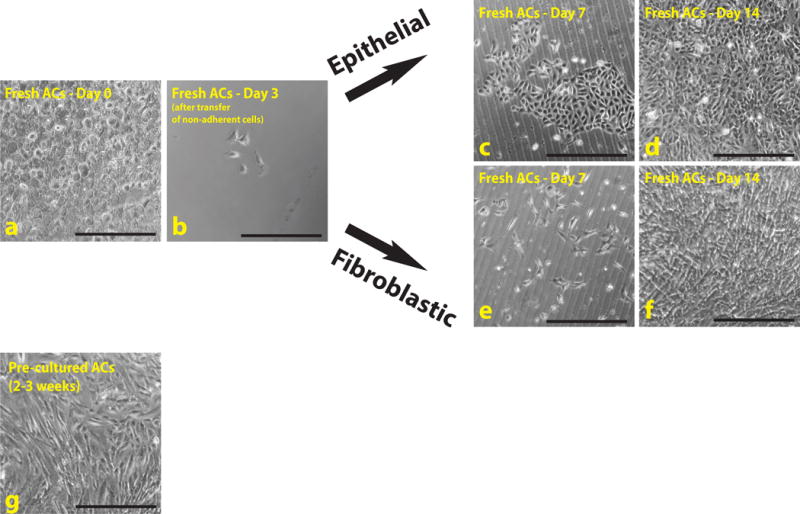

Figure 2. Morphology of freshly isolated and pre-cultured amniotic cells.

(a–f) Fresh ACs were cultured several weeks before transduction with ETS-TFs to increase cell number. Most of these cells remain in suspension and will not adhere to the plate (a). After changing the medium in a few days, distinct colonies of cells are observed (b). If the cells are cultured for a further 7 (c,e) or 14 (d,f) d, these colonies give rise to multiple cell types, the majority of which represent either epithelial (c,d) or fibroblastic (e,f) type lineages. (g) Precultured cells represent an established heterogeneous population of cells that can be transduced immediately, depending on the cell number. Scale bars, 500 μm.

TROUBLESHOOTING

Option B) Culture of “Pre-cultured” AC samples

CRITICAL “Pre-cultured” AC samples are ACs that have already been subjected to culture conditions. An advantage of using these cells is that the quantity of ACs in these samples is significantly higher than that of the “Fresh unmanipulated” AC samples. A disadvantage of using “Pre-cultured” ACs is that they are not freshly harvested; rather, they have been passaged several times and the conditions under which they have been cultured could vary slightly from sample to sample. Furthermore, culturing of ACs with serum and FGF-based growth factors might favor expansion of mesenchymal and fibroblastic over epithelioid subpopulations of ACs. However, it is important to note that our reprogramming strategy is effective to generate rAC-VECs from both mesenchymal and epithelioid subsets of both “Pre-cultured” ACs as well as “Fresh unmanipulated” ACs.

If the cells arrive in a flask (i. e. live cells), aspirate the media from the cells and add fresh media with a suitable amount of AC growth media. If the flask is already confluent (Fig. 2g), proceed to Step 3. If the flask is not confluent, add fresh media to the flask every 2 – 3 days until the cells have reached confluency, and then proceed to Step 3. If the cells arrive frozen, thaw the cells rapidly and transfer to a suitable flask with AC growth media. Add fresh media to the flask every 2 – 3 days until the cells have reached confluency, and then proceed to Step 3.

TROUBLESHOOTING

Expansion of ACs: Timing ~1 to 2 weeks

-

3)

Aspirate media, wash cells 1× with DPBS, and aspirate. Add accutase to detach cells. The volume of accutase is dependent on the plate/flask format; add enough accutase to cover the entire surface of the well/flask. Place in 37° incubator for ~3 min. If the cells have not detached after 3 min, return the flask to the 37° incubator for an additional 2–3 min.

-

4)

Add 2× the amount of AC growth media that was used to detach the cells to the well/flask (for example, if 1 ml of accutase was used to detach cells, add 2 ml of AC growth media to the well/flask). Pipette up and down around the surface of the well/flask to retrieve maximum number of cells, and transfer to a 15 ml conical tube.

-

5)

Centrifuge the tube at 400g for 5 min at 4°C. Aspirate the supernatant, and resuspend the cell pellet in AC growth media and re-plate into desired format (wells/flasks) and incubate. Continue expanding ACs by repeating steps 3–5 as each successive well/flask becomes confluent. When a desired number of ACs have been accumulated, proceed to Step 6.

PAUSE POINT Alternatively, ACs can be frozen at −80°C for future use as described in BOX 2 – FREEZING PROTOCOL.

Box 2. Freezing protocol • TIMING 10 min.

Although a variety of freezing media can be used to freeze both ACs and rAC-VECs, we use the following protocol which has proven to yield a high percentage of viable cells upon thawing for future use. The procedure below follows Step 5 (for ACs—refer to the PAUSE POINT) or Step 13 (for rAC-VECs) in the main PROCEDURE section.

Reagent Setup

Freezing medium. Freezing medium contains 90% FBS and 10% DMSO. To prepare 10 ml of freezing medium, mix 9 ml of FBS with 1 ml of DHSO. Freshly prepare the medium before use.

Procedure

Resuspend the cell pellet in 5 ml of DPBS and count the cells. Centrifuge the tube at 400g for 5 min at 4 °C, and then resuspend the cell pellet in appropriate volume of freezing medium, such that there are 500.000–1,000,000 cells per ml.

Transfer 1 ml of resuspended cells each into labeled cryovials, and then place the vials in a Nalgene cell freezing container.

Store the Nalgene cell freezing container at −80 °C for at least 24 h. The cryovials can be kept at −80 °C for short-term storage, or they can be transferred to liquid nitrogen for long-term storage.

CRITICAL When passaging these cells, we generally do not split them any greater than 1 to 3. For example, when passing a confluent T25 flask of ACs, we would split them into 3 new T25 flasks (or to 1 T75 flask). Similarly, one confluent well of a 6-well plate is usually passed to 3 new wells of a 6 well plate (or to 1 T25 flask). However, these splitting ratios can be further optimized by the individual researcher.

CRITICAL If the user so chooses, specific sub-populations of ACs can be purified at this point from the general AC population. However, as repurification of ACs is not necessary to achieve nor improve the desired outcome of generating numerous rAC-VECs, these steps have been omitted from the current protocol. For details on repurifying subpopulations of ACs, please refer to the original Ginsberg et al Cell paper21.

Lentiviral infection of ACs and subsequent generation of rAC-VECs – ~3 – 4 weeks

CRITICAL Prior to plating ACs for lentiviral infection, it is recommended that the researcher produce, test and titer all viruses necessary for the generation of rAC-VECs. For a description of lentiviral production, please refer to BOX 1.

-

6)

Plate ~100,000 ACs per well into multiple wells of 6-well plates (in 2 ml AC media per well) and place in a 37°C incubator.

-

7)

Day 0: After 18 – 24 h, aspirate the media and add 2 ml Endothelial growth media to each well. Add ~25,000pg of each lentivirus (refer to EXPECTED RESULTS in BOX 1 for details) directly into each well and place the plate(s) back in 37°C incubator. This should be considered day 0 of the lentiviral infection.

CRITICAL STEP The volume of lentivirus added to the cells will vary depending on the concentration of the specific virus. However, this volume should not exceed 100 μl, as this would likely indicate an extremely diluted virus content, which will decrease the efficiency of the infection.

CRITICAL The generation of rAC-VECs can be achieved by using lentiviruses composed of either a constitutively active ETV2 construct or a doxycycline-dependent TRE-ETV2 construct, in addition to using constitutively active ERG1 and FLI1 constructs21. Please refer to the INTRODUCTION and ANTICIPATED RESULTS sections for a discussion highlighting the differences between using lentiviruses composed of these two distinct ETV2 constructs. Additionally, if the TRE-ETV2 lentivirus is used here, be sure to also co-infect with the pTA lentivirus as well.

CRITICAL In place of using Endothelial growth media, rAC-VECs can alternatively be cultured in a ‘Defined Serum-Free’ media that is supplemented with the cytokines VEGF-A and FGF-2. However, these cells proliferate more poorly than rAC-VECs cultured in Endothelial growth media. Please refer to the ANTICIPATED RESULTS section for more information regarding the usage of serum-free media.

-

8)

After 18 – 24 h (day 1), aspirate the media and add 2 ml Endothelial growth media to each well. Place the plate(s) in the Low Oxygen 37°C incubator. CRITICAL STEP Endothelial growth media should always be pre-warmed to 37° in a water bath before use. (SEE TROUBLESHOOTING Step 8)

-

9)

After 2 – 3 d (day 3–4) remove the cells from the incubator. If the cells are not confluent, aspirate the media, re-feed with 2ml Endothelial growth media and return the plate to the Low Oxygen 37°C incubator. If the cells are confluent, pass the cells with Accutase (as described in Steps 3–5, except now use Endothelial growth media instead of AC growth media) and return the plate to the Low Oxygen 37°C incubator. CRITICAL STEP The number of cells that should be carried for this and all successive passages is at the discretion of the researcher. However, we have found that it is ideal to keep as many of these in cultures as possible throughout the reprogramming progress, as this allows multiple analyses to be performed on these cells as they become rAC-VECs, as described in step 11.

-

10)

Continue to pass/re-feed the cells every 2 – 3 days until days 7– 8. (SEE TROUBLESHOOTING Step 10)

-

11)

On day 7 – 8 of the lentiviral infection, collect a small fraction of the cells for processing and analysis. Continue to culture remaining cells for a further 7 days. A variety of EC markers can be assayed for by qPCR and FACS/immunostaining. Please refer to Supplementary Table 1 in SUPPLEMENTARY MANUAL for proposed primers for qPCR. Table 1 below lists antibodies for FACS/immunostaining for suggested targets (also, see ANTICIPATED RESULTS and Fig. 3a). These are standard qPCR or FACS/immunostaining assays, thus standard procedures can be followed. These and other assays that can assess the efficiency of reprogramming ACs into rAC-VECs have also been previously described21.

-

12)

On day 14 – 15 of the lentiviral infection, collect a small fraction of the cells for processing and analysis, as described in step 11.

Figure 3. ACs transduced with ETS-TFs express multiple EC markers within 3–4 weeks.

(a) Surface expression for three EC proteins was assayed for by FACS at 7 d (left) and 21 d (right) after lentiviral transduction with ETS-TFs. Within 7 d, differential expression levels of VE-cadherin, VEGFR2 and CD31 are observed. By day 21 of the reprogramming platform, the majority of the cells express high levels of all three EC markers. A minimum of 1 × 105 cells were analyzed for each sample, and all samples were run in triplicate. Error bars depict s.e.m. (b) Immunostaining at days 0 (left images) and 21 (right images) of the reprogramming platform shows substantial accumulation of VE-cadherin protein at the membrane of transduced cells after 21 d (bottom right, green). DAPI was used to stain nuclei (blue). Scale bars, 200 μm.

CRITICAL STEP If the TRE-ETV2 construct was used in Step 7, doxycycline should now be used to turn off ETV2 expression: add 1 μl doxycycline stock per 1 ml of Endothelial growth media to the cells. Continue to culture cells for a further week, adding fresh doxycycline every 2 – 3 d (best to add when changing media) for sustained suppression of ETV2 in TRE-ETV2 transduced cells.

-

13)

By day 21 of the lentiviral infection, the majority of the cells should be stable rAC-VECs. Collect a small fraction of the cells for processing and analysis, as described in step 11 (see also ANTICIPATED RESULTS and Fig. 3a). At the discretion of the researcher, rAC-VECs can be further cultured or be frozen down for long-term storage (see BOX 2 – FREEZING PROTOCOL).

(SEE TROUBLESHOOTING Step 13) TIMING

Step 1 – Lentiviral preparation: 1 week Step 2 – Initial Culturing of ACs: 1d – 2 weeks Steps 3 thru 5 – Expansion of ACs (prior to lentiviral transduction): 1 week – 2 weeks Steps 6 thru 13 – Lentiviral infection and generation of rAC-VECs: 3 weeks – 4 weeks

TROUBLESHOOTING

See Table 2 for troubleshooting guidance.

Table 2.

Troubleshooting

| Step | Problem | Potential reason | Potential solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Little/no AC growth | Poor AC media quality | Make fresh AC media |

| Poor AC sample viability | Use another AC sample | ||

| 8 | Massive cell death | Lentiviral toxicity | Decrease viral input/re-titer virus |

| 10 | Little/no transduced – AC growth | Poor endothelial growth media quality | Make fresh endothelial growth medium |

| 13 | rAC-VECs are poorly or not generated | Lentiviral preparation was poor | Check titer/remake viruses |

| Lentiviral protein expression is low | Check by western/remake viruses | ||

| Poor endothelial growth media quality | Make fresh endothelial growth media | ||

| Fibroblastic outgrowth | Use another AC sample | ||

| Incubation conditions (5% O2) are off | Check incubators |

ANTICIPATED RESULTS

One week after lentiviral infection with ETS-TFs, ACs transitioning to ECs express substantial levels of vascular-specific transcripts (including VE-cadherin, CD31 and VEGFR2), which are expressed for beyond 1 month in vitrO21. However, protein surface expression of these EC genes is differentially expressed over a broader period of time. For example, within 7 d of ETS-TF lentiviral infection of ACs, VE-cadherin is expressed at markedly higher levels at the cell surface than is VEGFR2 or CD31 (Fig. 3a, left). Within 21 d of ETS-TF transduction platform in which the constitutive ETV2 lentivirus was used, nearly the entire population expresses high levels of both VE-cadherin and VEGFR2, but little to no expression of CD31 (data not shown) is observed. These rAC-VECs are highly proliferative and extremely stable, but they are not considered to be fully mature ECs because of a lack of CD31. When ETV2 is suppressed at day 14 of the platform (via utilization of the TRE-ETV2 lentivirus), by day 21 nearly every cell now shows expression of all three EC markers (Fig. 3a, right). These mature rAC-VECs are also highly stable, but they demonstrate a slightly more modest proliferation potential than do rAC-VECs generated with constitutive ETV2. In addition, rAC-VECs exhibit the typical cobblestone morphology of mature ECs, as well as junctional localization of surface markers, such as VE-cadherin (Fig. 3b). Last, rAC-VECs can also be established by using a defined serum-free medium that is supplemented with VEGF-A and FGF2 cytokines (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, it should be noted that rAC-VECs generated under these conditions demonstrate a lower proliferation potential, which is probably attributable to the absence of other essential ligands and cytokines that are present in endothelial growth (serum-based) medium. Notably, however, rAC-VECs can indeed be maintained in serum-free or other non-EC media conditions (unpublished data), underscoring their potential in coculture systems that could support a variety of cell types

Most importantly, rAC-VECs can be clonally expanded, allowing for the identification of clones that have the optimal stoichiometry of ETV2, FLI1 and ERG1 (ref. 21). Indeed, clones with lower or nearly absent ETV2 but higher levels of FLI1 and ERG1 phenocopy the functional and molecular profile of mature ECs.

Details of the expected phenotype and functionality demonstrated by mature rAC-VECs have been previously published21. In summary, rAC-VECs are endowed with a global genome-wide transcriptome that nearly matches that of other primary cultured EC populations, including HUVECs and LSECs. Notably, the transcriptional profile of rAC-VECs is significantly closer to these well-documented EC subtypes as compared with human ESC-derived ECs, supporting the notion that transitioning through a pluripotent state is less efficient in generating stable and proliferative ECs. Furthermore, the proliferation potential of these cells far surpasses that of ECs obtained from other cell sources, such as placental- or umbilical cord–derived ECs (i.e., HUVECs). Whereas HUVECs can typically be passaged for only 6–8 times in vitro, at which point they tend to lose their EC phenotype, rAC-VECs maintain their EC identify much longer (i.e., >P15) in culture conditions. Last, rAC-VECs are functionally durable and capable of long-term engraftment into mouse host microvasculature in NOD-SCID mice. These results validate the authenticity of rAC-VECs as viable ECs that may serve a clinical benefit for therapies designed to address vascular dysfunction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to D. James and V. R. Pulijaal (Weill Cornell Medicine) for help in providing material and intellectual input. W.S., K.S. and S.R. are supported by Ansary Stem Cell Institute, the Empire State Stem Cell Board and New York State Department of Health grants (C026878, C028117, C029156). S.R. is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL115128, R01HL119872 and R01HL128158), the National Cancer Institute (U54CA163167), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK095039), the Qatar National Priorities Research Program (NPRP 6-131-3-268), and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. W.S. was also supported by a US National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grant (T32HL94284).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.R. envisioned the original idea. M.G., W.S. and S.R. developed the protocol and wrote the manuscript. M.G. performed the majority of the experiments. W.S. contributed to these experiments. W.S. and K.S. conceived the project and interpreted the data. K.S. wrote the IRB protocol and provided assistance in obtaining the AC samples. All authors commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

M.G. is a senior scientist with Angiocrine Bioscience. S.R. is a co-founder of Angiocrine Bioscience.

References

- 1.Ding BS, et al. Inductive angiocrine signals from sinusoidal endothelium are required for liver regeneration. Nature. 2010;468:310–315. doi: 10.1038/nature09493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding BS, et al. Endothelial-derived angiocrine signals induce and sustain regenerative lung alveolarization. Cell. 2011;147:539–553. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu J, et al. Endothelial cell-derived angiopoietin-2 controls liver regeneration as a spatiotemporal rheostat. Science. 2014;343:416–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1244880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler JM, et al. Endothelial cells are essential for the self-renewal and repopulation of Notch-dependent hematopoietic stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2010;6:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi H, et al. Angiocrine factors from Akt-activated endothelial cells balance self-renewal and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1046–1056. doi: 10.1038/ncb2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rafii S, et al. Human bone marrow microvascular endothelial cells support long-term proliferation and differentiation of myeloid and megakaryocytic progenitors. Blood. 1995;86:3353–3363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rafii S, et al. Isolation and characterization of human bone marrow microvascular endothelial cells: hematopoietic progenitor cell adhesion. Blood. 1994;84:10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nolan DJ, et al. Molecular signatures of tissue-specific microvascular endothelial cell heterogeneity in organ maintenance and regeneration. Developmental cell. 2013;26:204–219. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandler VM, et al. Reprogramming human endothelial cells to haematopoietic cells requires vascular induction. Nature. 2014;511:312–318. doi: 10.1038/nature13547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takebe T, et al. Vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nature. 2013;499:481–484. doi: 10.1038/nature12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi KD, et al. Hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem cells. 2009;27:559–567. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James D, et al. Expansion and maintenance of human embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells by TGFbeta inhibition is Id1 dependent. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:161–166. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prasain N, et al. Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to cells similar to cord-blood endothelial colony-forming cells. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32:1151–1157. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morita R, et al. ETS transcription factor ETV2 directly converts human fibroblasts into functional endothelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:160–165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413234112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurian L, et al. Conversion of human fibroblasts to angioblast-like progenitor cells. Nature methods. 2013;10:77–83. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagarkova MA, Volchkov PY, Philonenko ES, Kiselev SL. Efficient differentiation of hESCs into endothelial cells in vitro is secured by epigenetic changes. Cell cycle. 2008;7:2929–2935. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.18.6700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang ZZ, et al. Endothelial cells derived from human embryonic stem cells form durable blood vessels in vivo. Nature biotechnology. 2007;25:317–318. doi: 10.1038/nbt1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kane NM, et al. Derivation of endothelial cells from human embryonic stem cells by directed differentiation: analysis of microRNA and angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2010;30:1389–1397. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.204800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levenberg S, Golub JS, Amit M, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Langer R. Endothelial cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:4391–4396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032074999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ginsberg M, et al. Efficient direct reprogramming of mature amniotic cells into endothelial cells by ETS factors and TGFbeta suppression. Cell. 2012;151:559–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pera MF. Stem cells: The dark side of induced pluripotency. Nature. 2011;471:46–47. doi: 10.1038/471046a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mummery C. Induced pluripotent stem cells–a cautionary note. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364:2160–2162. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1103052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okano H, et al. Steps toward safe cell therapy using induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation research. 2013;112:523–533. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.256149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris SA, et al. Dissecting engineered cell types and enhancing cell fate conversion via CellNet. Cell. 2014;158:889–902. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Rham C, Villard J. Potential and limitation of HLA-based banking of human pluripotent stem cells for cell therapy. Journal of immunology research. 2014;2014:518135. doi: 10.1155/2014/518135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benavides OM, Petsche JJ, Moise KJ, Jr, Johnson A, Jacot JG. Evaluation of Endothelial Cells Differentiated from Amniotic Fluid-Derived Stem Cells. Tissue engineering Part A. 2012 doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2011.0392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Coppi P, et al. Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:100–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konig J, et al. Amnion-derived mesenchymal stromal cells show angiogenic properties but resist differentiation into mature endothelial cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:1309–1320. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang P, Baxter J, Vinod K, Tulenko TN, Di Muzio PJ. Endothelial differentiation of amniotic fluid-derived stem cells: synergism of biochemical and shear force stimuli. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:1299–1308. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:19171920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markoulaki S, et al. Transgenic mice with defined combinations of drug-inducible reprogramming factors. Nature biotechnology. 2009;27:169–171. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Efe JA, et al. Conversion of mouse fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes using a direct reprogramming strategy. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:215–222. doi: 10.1038/ncb2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim J, et al. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts to neural progenitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:7838–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103113108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindenmair A, et al. Mesenchymal stem or stromal cells from amnion and umbilical cord tissue and their potential for clinical applications. Cells. 2012;1:1061–1088. doi: 10.3390/cells1041061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee D, et al. ER71 acts downstream of BMP, Notch, and Wnt signaling in blood and vessel progenitor specification. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:497–507. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu F, Walmsley M, Rodaway A, Patient R. Fli1 acts at the top of the transcriptional network driving blood and endothelial development. Current biology: CB. 2008;18:1234–1240. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McLaughlin F, et al. Combined genomic and antisense analysis reveals that the transcription factor Erg is implicated in endothelial cell differentiation. Blood. 2001;98:3332–3339. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Val S, Black BL. Transcriptional control of endothelial cell development. Developmental cell. 2009;16:180–195. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birdsey GM, et al. Transcription factor Erg regulates angiogenesis and endothelial apoptosis through VE-cadherin. Blood. 2008;111:3498–3506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105346. doi:blood-2007-08-105346 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2007-08-105346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Val S, et al. Combinatorial regulation of endothelial gene expression by ets and forkhead transcription factors. Cell. 2008;135:1053–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dryden NH, et al. The transcription factor Erg controls endothelial cell quiescence by repressing activity of nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB p65. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:12331–12342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346791. doi:M112.346791 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M112.346791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kataoka H, et al. Etv2/ER71 induces vascular mesoderm from Flk1+PDGFRalpha+ primitive mesoderm. Blood. 2011;118:6975–6986. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-352658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.